Abstract

This study examines how price sensitivity parameters affect customer lifetime value in the luxury business. Quality, position, information, time, and customer lifetime were examined as price sensitivity factors followed by a conceptual model and research hypotheses were produced based on previous studies. Secondary analysis and in-depth interviews with industry specialists and customers. A representative sample of 232 A class consumers was included in a survey that was given to A-class customers in Egypt. A new level of price sensitivity known as ‘quality positioning value’ was found through the use of factor analysis. Multiple discriminant analysis was performed to validate the hypotheses and Cronbach’s alpha was utilised to assess the reliability of the data. This analysis sheds light on the effect of price sensitivity on customer lifetime value in the luxury industry.

1. Introduction

This study investigates how customers’ sensitivity to pricing impacts customer lifetime value (CLV) in the luxury goods industry. Through an extensive literature review, four key dimensions of price sensitivity were identified that will be examined: Quality Value, Time Value, Position Value, and Information Value.

Previous research shows that price plays a major role in how customers evaluate product options and make purchasing choices (Hsu et al., Citation2017). Specifically, price heavily influences customers’ judgments about a brand’s pricing relative to competitors and decisions between brands and product types (Niedrich et al., Citation2009).

Price is an integral part of a company’s marketing strategy, representing the ascribed value of a product and amount charged. Academics define price as the exchange value of goods and services. Appropriate pricing is crucial for companies to establish market share and profitability. While pricing decisions can be made quickly, poor pricing can severely hinder a company’s success. Firms should recognise the opportunity to create value by aligning their revenue generation approaches (Sjödin et al., Citation2020).

Moreover, customers typically compare the objective price with their internal reference price, which is the overall price range they associate with the product category. After purchasing a product or service, customers may not remember the actual price but will encode it in a way that is meaningful to them, such as ‘cheap’ or ‘expensive’. The objective price only becomes significant to customers when they interpret it subjectively (Chua et al., Citation2015).

Therefore, this research centres on the luxury sector, a notion characterised by subjectivity that has evolved throughout history. In ancient Greece, it carried unfavourable implications, whereas in Rome, it encompassed both positive and negative connotations. Its roots trace back to the Latin term ‘luxus’, denoting ‘lavishness’ or ‘wealth’, and subsequently acquired associations with ‘illumination’ (Rezzano & Fallini, Citation2021).

While, understanding price sensitivity is critical in marketing, but it is not the only element influencing consumer behaviour. There are dimensions that influence how buyers perceive value, and these factors can influence their price sensitivity, as developed from previous studies, such as quality value, time value, position value, and information value. Higher costs may improve perceived quality as the perception of quality can therefore influence how much a buyer is willing to pay for a product (Danes & Lindsey-Mullikin, Citation2012).

In markets where timely access to products is critical, the speed at which items become available often heavily influences consumer purchases. Customers in these time-sensitive situations may agree to pay premium pricing to underscore their perceived value of obtaining products rapidly (Boyaci & Ray, Citation2003). Furthermore, when brands strategically highlight their uniqueness and differentiation, they can partly mitigate price sensitivity that consumers may attach to that offering (Kaul & Wittink, Citation1995). In determining optimal pricing for enhanced products, customer value perceptions represent vital data points (Ingenbleek et al., Citation2010).

In this study, customer lifetime value (CLV) was examined from a non-financial standpoint. consumer lifetime value (CLV) is related to consumer purchasing patterns, which may include repeat purchases or increased purchases through methods like as up-selling and cross-selling (Kumar et al., Citation2010). Customer lifetime value (CLV) is becoming more widely recognised as a key indicator in customer relationship management (CRM) for acquiring, cultivating, and maintaining the most valuable customers (Venkatesan & Kumar, Citation2004).

2. Aim of research

The aim of this study is to examine the impact of price sensitivity dimensions on customer lifetime value in the Egyptian luxury sector. The goal is to delve into the numerous facets and insights that define this interaction, providing a thorough grasp of the dynamics at work, thus filling potential knowledge gaps in this area of study.

3. Literature review

3.1. Price sensitivity

Sensitivity to price, or elasticity, is a crucial concept in consumer behaviour. It describes how consumers respond to price changes or product or service modifications (Yue et al., Citation2020). Customers are willing to pay more when perceived value exceeds cost (Fang et al., Citation2016). This pricing response is extremely valuable for marketing strategies (Rundh, Citation2013). Nonetheless, it is essential to recognise that consumer price sensitivity varies.

It changes based on a number of variables, such as personal traits, the product itself, needs, brand familiarity, budget, and time (Natarajan et al., Citation2017). Price decisions made by a business are heavily influenced by this price-sensitivity fluidity, which also directly affects overall profitability (Gao et al., Citation2017). Moreover, Monroe (Citation1990) and Zeithaml (Citation1988) contend that consumers’ assessments of a product or service’s worth are impacted by what they expected and what they actually received.

3.1.1. Quality value

In consumer behaviour, the term ‘quality’ refers to a customer’s assessment of a product’s superiority or perfection. This is distinct from the product’s actual quality and is a holistic assessment rather than a specific trait (Zeithaml, Citation1988). Quality comprises all a product’s or service’s features and components that contribute to its ability to meet consumer needs. When the quality of a product is exceptional, it is more likely to influence purchasing decisions by increasing the perceived value (Waluya et al., Citation2019). As a result, consumers seek long-lasting products, emphasising the importance of great quality for long-term growth (Aliyev et al., Citation2019).

Furthermore, product quality mediates the link between price sensitivity and purchasing desire. When the quality of a product is high, customers are less influenced by price changes and more likely to buy, demonstrating a willingness to pay more for greater quality (Gomes et al., Citation2023). It is noteworthy in the luxury business that brands prioritise craftsmanship and quality assurance, even allowing no faults. As a result, while acquiring luxury items, shoppers should be wary of unjustifiable price increases (Simon & Fassnacht, Citation2019).

3.1.2. Time value

Time-based value is the perceived value of a product by a customer depending on factors such as availability, promotions, and decision time. Customers prioritise time when they are time-pressed, a condition known as ‘time famine’, which leads to greater price sensitivity and eventual brand switching if their time is not appreciated (Granter et al., Citation2015).

Businesses can prioritise the customer experience by respecting time, responding quickly to complaints, and maintaining clear communication to increase loyalty (Granter et al., Citation2015). Customers who value their time, on the other hand, are more willing to invest in time-saving products and services. Luxury consumers place a high value on customisation and personalisation and are willing to pay more for products and services that may be tailored to their preferences while also saving them time (Choo et al., Citation2012).

Excessive wait times can have a detrimental influence on consumer satisfaction, causing annoyance and dissatisfaction. Customer happiness can be increased by accurately estimating wait times, providing interesting activities during waits, and giving online or mobile alternatives to physical waiting. Therefore, businesses should be cautious about saving time for customers (Palawatta, Citation2015).

3.1.3. Position value

Price sensitivity may be reduced by brand positioning, particularly when a brand is positioned to emphasise its distinctiveness (Kaul & Wittink, Citation1995). Positioning, a 1960s concept, is essential in strategic marketing, along with segmentation and targeting. Its purpose is to distinguish a brand from competitors, respond to customer expectations, and generate brand loyalty and equity, hence improving long-term competitive advantage (Alpert & Gatty, Citation1969). Effective brand positioning can result in considerable competitive advantages, while high brand presence can result in major market benefits (Cambra-Fierro et al., Citation2021).

To properly position a brand, marketers must define and differentiate their brand from competitors. This includes determining the target market and relevant competition, determining the best points of parity and difference in brand associations, and developing a brand slogan that encompasses the brand’s positioning and essence (Kotler & Keller, Citation2016). Another important part of brand positioning is a brand’s competitive stance, which is generally represented in its aggressive market posture. This includes the distinct brand image that buyers perceive, which is developed by both regular and emotional consumer research (Mindrut et al., Citation2015).

3.1.4. Information value

The information value dimension is concerned with the importance of knowledge received through co-creative behaviours, underscoring the importance of group interactions in the generation of perceptive knowledge (Zhu et al., Citation2022). The primary determinant of information’s value is its availability. This is due to the importance of educating consumers and giving them the information, they need to make the best decisions (Kim & Phua, Citation2020).

Building on this, consumers make quality decisions based on a variety of cues, such as information contained inside the goods or services as well as data acquired from other sources. Customers rely less on these indicators when they learn more about a company’s product offerings. Interestingly, purchasers who are better knowledgeable about a product or service rely less on external signs to assess its quality (Alshibly, Citation2015). Customers often rely on reputable sources of information when making purchasing decisions (An & Han, Citation2020).

In addition, businesses use customer information to enhance their services, goods, and overall customer experience through the strategic process of customer knowledge management (Smith & McKeen, Citation2005). In-depth product details can influence consumers’ perceptions of luxury goods, increasing their sense of reward and encouraging them to spend more money (Lim et al., Citation2014).

In general, when customers actively engage with a service, it enhances their understanding of the service’s worth and its unique features. This, in turn, tends to decrease their responsiveness to price fluctuations and has an impact on their choices when making purchases (Hsieh & Chang, Citation2004).

3.2. Customer lifetime value

Customer lifetime value (CLV) is related to consumer purchasing patterns, which may include repeat purchases or increased purchases through methods like up-selling and cross-selling (Kumar et al., Citation2010). Customer lifetime value (CLV) estimations include non-financial characteristics such as happiness and loyalty in measuring a customer’s overall value over time, supporting firms in identifying and maintaining important customers. To maintain these, exceptional customer service and experiences are essential, which can be offered through swift issue responses across several channels. Customer satisfaction is boosted by devoted, skilled customer service personnel who instil a sense of worth and loyalty in their customers. Transparency regarding product features, pricing, and potential issues builds trust and reduces negative comments (Ali et al., Citation2018).

Providing high-quality goods or services that continuously exceed client expectations boosts loyalty even more. Listening to clients and addressing their concerns increases happiness and loyalty (Kumar, Citation2008). Long-term connections may not necessarily result in increased profitability due to significant income and cost variances across consumers. As a result, recent research has emphasised the importance of fine-tuning customer acquisition, retention, and development strategies to boost customer lifetime value (CLV), hence increasing shareholder value (Lemon & Verhoef, Citation2016).

It is increasingly becoming identified as an important indication in customer relationship management (CRM) for obtaining, growing, and retaining the most valued customers. However, many firms fail to use CLV metrics effectively. It may start with less profitable customers, or they may lack the skills required to customise the client experience to optimise value generation (Venkatesan & Kumar, Citation2004).

Given the lack of non-financial measures of customer lifetime value (CLV), this study used a multidimensional approach based on prior academic research. The previous study provided four separate dimensions, providing a more thorough and nuanced knowledge of CLV from non-financial perspectives. For psychological value, customers strive to develop an effective and constant sense of self-worth; satisfying this psychological requirement leads to a connection between customers and brands (Segarra-Moliner & Moliner-Tena, Citation2022).

For social value, Customer behaviour in the luxury business is frequently impacted by social norms and social institutional standards, such as those established by reference groups. Understanding the impact of social value judgements on luxury purchasing is crucial for luxury brands to properly target and manage their brand image (Shukla, Citation2012). Financial value is the monetary value attributed to a customer’s relationship with a corporation over the life of that relationship (Irvine et al., Citation2016).

For functional value, understanding the concept of functional value is critical in determining how well products, services, or solutions fit the needs and expectations of customers or users (Kato, Citation2021).

4. Exploratory evidence

The purpose of this exploratory study is to delve deeper into the factors that influence price sensitivity and customer lifetime value in the context of Egyptian luxury consumers. Given the scarcity of existing studies in this field, an exploratory research methodology was selected as appropriate. This form of research fills knowledge gaps and provides basic insights that can be used to lead further confirmatory studies.

4.1. Secondary data analysis

This research investigates how luxury brands in the hospitality, real estate, and automobile industries lower price sensitivity while increasing customer value. Hotels with international recognition, such as the Burj Al Arab Jumeirah, The Ritz-Carlton, and Four Seasons Hotel George V, provide great services, high-quality amenities, and personalised experiences. Emaar Misr and SODIC, for example, offer distinctive designs, community interaction, and a varied range of amenities. Similarly, luxury automakers such as Ferrari, Porsche, and Rolls-Royce emphasise their distinctive brand features such as heritage, craftsmanship, performance, and commitment to quality.

These tactics justify premium pricing while also increasing client loyalty. According to the survey, creating outstanding, personalised experiences is critical to minimising price sensitivity and enhancing customer lifetime value in the luxury industry. To gather diverse perspectives, in-depth interviews were conducted with both A-class customers and industry professionals.

4.2. Qualitative analysis

In-depth interviews with industry experts and A-class consumers uncover additional values and techniques that boost client lifetime value and alleviate price sensitivity. Hotel managers place a premium on client happiness, service excellence, and feedback, whereas real estate professionals place a premium on the unique value of their products, customer-centric strategies, and community involvement. Automobile industry professionals use brand prestige to offset price sensitivity, focusing on creating outstanding client experiences. Similarly, A-class clients consider service quality, timeliness and efficiency, brand recognition, and location value to be important factors in their purchasing decisions. These aspects impact the overall customer experience, which leads to enhanced loyalty and customer lifetime value.

5. Conceptual model and hypothesis

5.1. Hypotheses development

These hypotheses development presents the associations proposed by the theoretical framework produced from the previous studies ().

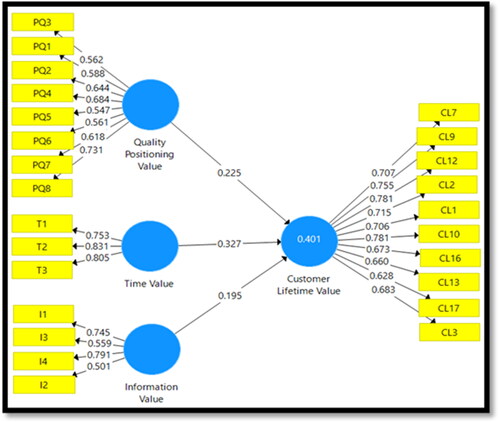

Figure 2. Structural equation model for phenomenon.

Note: The preceding . Displays the phenomenon’s structural equation model. It illustrates all the variables’ relationships. It also displays the final assertions that were used in the analysis.

H1: There’s a significant impact of quality value on customer lifetime value.

H2: There’s a significant impact of time value on customer lifetime value.

H3: There’s a significant impact of position value on customer lifetime value.

H4: There’s a significant impact of information value on customer lifetime value.

6. Research methodology

6.1. Research design

Qualitative Approach: As previously stated, an exploratory study in the form of in-depth interviews with industry professionals and customers will gain insights into the values of price sensitivity and customer lifetime value after reviewing previous studies.

Quantitative approach: This study was conducted to gain a ‘single cross-sectional data collection design’ to collect respondents’ comments at a single point in time. The cross-sectional design has been a basic strategy in many disciplines of research employed a ‘snapshot’ of the population at a certain time, allowing for the simultaneous examination of multiple attributes without the need for extensive study. This characteristic not only saves time and resources but also allows for the rapid development of meaningful information (Levin, Citation2006).

Primary data for this study will be gathered through two main methods: structured surveys to acquire quantitative data, and in-depth interviews to gather qualitative data. Structured surveys consisting of close-ended questions will be used to collect quantitative data. In-depth semi-structured interviews with open-ended questions will be conducted to gather qualitative data. Qualitative interviews are particularly useful during the exploratory phases of research to gain a thorough understanding of the phenomena under investigation (Creswell, Citation2012). Using both quantitative surveys and qualitative interviews will allow for collecting robust primary data to address the research questions. While quantitative data might provide numerical precision, it may lack the depth and context that qualitative data provide. As a result, it is frequently necessary to describe the relationships between variables to demonstrate how they interact with one another (Creswell, Citation2012).

6.2. Sampling design and plan

The study relies on a sample of Class A clients from Egypt’s luxury sector. Given the population’s size and diversity, a careful selection guide is employed to identify and authenticate these clients. Because the population is indeterminate, probability sampling approaches, in which each instance has a known and non-zero probability of being chosen (Saunders et al., Citation2009), are substituted by non-probability and judgement sampling methods. These methods entail selecting specific units from the population that are assumed to reflect the larger universe (Kothari, Citation2017). Participants were selected using a convenience selection strategy based on their accessibility, availability, and proximity to the study. This method entails getting information from people who are eager, friendly, or easily accessible to the researcher (Scholtz, Citation2021). In contrast, judgmental sampling is based on the researcher’s opinion of who will provide the best information to meet the study’s objectives. The researcher must seek out people who have the necessary expertise and are prepared to provide it (Etikan & Bala, Citation2017).

6.3. Measurement development ()

7. Analysis of results

A total of 232 surveys were completed and acquired from respondents who participated in this study. The descriptive results, as shown in , show that males made up most of the sample (58.1%). The age group was dispersed in such a way that most of the sample (76.4%) was beyond the age of 40. Because the study targeted people with salaries greater than $50,000, it is understandable that just 5 (2.6%) of those in the sample were under the age of 30. More than half of the sample (70.7%) had postgraduate studies as an educational background. According to the sample’s occupations, administrative work for either the public or private sector (51.3%) was the most often reported job, followed by specialised profession (22.5%), freelance (13.6%), and academic (12.6%). 112 people reported incomes ranging from $50,000 to $100,000 (58.6%). Only 18 people (9.4%) were reported to have an income greater than $150,000.

Table 1. Variables scale items and measures.

Table 2. Frequency tables for demographic variables.

7.1. Dimensional reliability and validity

Principal component analysis was utilised to extract the items from the exploratory factor analysis. Time value, information value, and brand quality positioning value were the three criteria. The quality positioning value combines the quality and position of the brand. Following the exploratory factor analysis, the new dimensions’ reliability and validity should be assessed. As a result, a confirmatory factor analysis is carried out ().

Table 3. Model measurements of the phenomenon.

To discover common technique bias, a complete collinearity methodology is applied. VIFs are determined to have a value of fewer than five. This is in line with Kock (Citation2017). The common approach bias does not need additional investigation. A confirmatory factor analysis was then used to test the reliability and validity.

To test reliability, the Cronbach alpha was calculated. It was revealed that it exceeded 0.6. As a result, there is enough evidence to conclude that the claims are reliable and internally consistent. The factors are subsequently validated using the calculated composite reliability and average variance. Each dimension has an extracted average variance better than 0.5 and a composite reliability greater than 0.7. This means that the measurements are accurate. The loadings were all more than 0.5, showing that the model’s claims were all significant and crucial to building structural equation modelling ().

Table 4. Fornell-Larcker criterion for measuring discriminant validity of the theoretical model.

The square root of the extracted average variance, according to Fornell-Larcker, should be bigger than any other dimension-to-dimension connection. Because the square root of the average variance recovered in the study was smaller than the rest of the calculations, the discriminant validity table shows that there was validity.5.2.4 Correlation Analysis ().

Table 5. Spearman correlation coefficients in phenomenon.

At 99% confidence, the association between customer lifetime value and information value was shown to be a significant moderate relationship. At 99% confidence levels, the quality positioning value demonstrated a weakly significant association with the customer lifetime value. Furthermore, at the 0.01 significance level, the time value demonstrated a statistically weak connection with customer lifetime.

This provides a decent sense of the model that can be developed and its outcomes. However, correlation analysis does not account for the effect of other variables; therefore, a model would be a better way to support the hypotheses in the study.

7.2. Structural equation modelling

To According to the Path coefficients , at the 99% confidence level, both information value and time value had a significant positive impact on customer lifetime value. It has been discovered that time value (=0.331) has a greater and stronger impact on customer lifetime value than information value (=0.209). At 99% confidence, the quality positioning value (=0.239) was determined to have a substantial positive impact on the customer lifetime value (). As a result, the higher the availability of information, the company’s quality position, and the ease of access to the brand, the more the client would value and prefer the luxury brand ().

Table 6. Path coefficients of the model.

Table 7. Model evaluation metrics.

The model’s R2 value was 0.401. It is possible to explain this by claiming that the model, which includes quality positioning, information, and time values, accounts for 40% of the variation in customer lifetime value. It is the predictive accuracy metric, with a Q2 value of 0.174. If it is greater than zero, it indicates that the PLS model was good. Because the SRMR is close to zero or equal to 0.1, the model was an excellent fit for the data.

8. Theoretical implications

This research greatly expands our understanding of price sensitivity in luxury markets by introducing and validating new components—quality value, time value, and information value. Integrating these factors provides a more nuanced perspective on how customers perceive and react to pricing. This theoretically broadens and solidifies the foundations for further consumer behaviour investigation in premium segments.

Given minimal existing research on price sensitivity facets (like information, quality, time, position value) and their interplay with customer lifetime value (CLV), this work carries major theoretical implications. By empirically examining the relationship between price sensitivity dimensions and CLV, it advances current knowledge and charts direction for future exploration into this area. In turn, this can refine theoretical frameworks describing price sensitivity traits, dynamics, and links to CLV.

Additionally, the discovery of a novel connection between price sensitivity and customer lifetime value demonstrates that orchestrating price sensitivity factors can boost CLV specifically in high-end settings. Moreover, the research enhances reliability and validity of the scales used to measure price sensitivity and CLV factors. This further cements methodological rigour in this research domain.

9. Managerial implications

Given the considerable impact of quality positioning value on customer lifetime value (CLV), businesses can justify premium pricing by emphasising the higher quality of their luxury products or services. This could involve investing more in quality assurance, product development, and branding campaigns that highlight their superior service quality. Given the positive impact of quality positioning value on CLV, luxury businesses should purposefully position their products or services in the market’s high-quality, premium category.

This could involve increasing premium appeal through exceptional design, exclusive benefits, and a compelling brand story that appeals to the luxury target market. Because of the positive association between time value and CLV, luxury businesses should optimise the time value of their items. This could imply instituting time-limited exclusivity for new things or experiences to increase urgency and perceived worth.

Luxury businesses should strive for pricing transparency, given the known role of information value in price sensitivity. Clear communication about the product or service’s worth, craftsmanship, exclusivity, and premium qualities helps justify higher costs and build confidence with high-end clients. Client segmentation can benefit from CLV dimensions such as psychological value, social value, financial value, and functional value. Luxury companies can use these insights to create individualised marketing approaches and customised experiences for their most significant customers.

10. Research limitations

According to the dearth of accurate statistics on price-sensitive customers in Egypt’s luxury business, the study’s sample size may be limited. This may have an impact on the findings’ generalisability because the sampled customers may not fully represent the greater customer base in terms of demographics, tastes, or behaviours. The research, as a cross-sectional study, gives a glimpse of the impact of price sensitivity on customer lifetime value at a certain point in time. This method may overlook any temporal changes in these variables. As a result, the data may not fully reflect how price sensitivity and customer lifetime value change in reaction to changing market conditions or consumer trends.

The study focuses primarily on the Egyptian market, which may limit the findings’ applicability to other cultural or geographical contexts. Due to differences in cultural norms, economic situations, and attitudes towards luxury spending, consumer behaviour, particularly price sensitivity and valuation of luxury items, can vary dramatically across markets.

Obtaining the requisite data may be difficult due to the luxury nature of the firms surveyed in the exploratory study (real estate, vehicles, and luxury hotels). Corporate sensitivity and confidentiality issues may limit the scope and depth of available data for investigation.

11. Future research recommendations

Future research could examine broadening the geographical scope of the study beyond the Egyptian market to include additional markets. This would aid in understanding cultural disparities in price sensitivity and customer valuation of luxury goods, boosting the findings’ generalisability.

Given that luxury brands are consumed by people from all socioeconomic backgrounds in Egypt, future studies should involve a diversified sample from all socioeconomic backgrounds. This would provide a more comprehensive view of price sensitivity and client lifetime value across different consumer categories in the luxury industry.

In forthcoming studies, a longitudinal approach can be employed to analyse fluctuations in price sensitivity and customer lifetime value across time. This approach will illustrate the alterations in these factors as they react to evolving market dynamics and shifting consumer preferences.

Subsequent research endeavours may delve into other factors that exert an impact on customer lifetime value within the luxury sector. This could yield a more all-encompassing understanding of the drivers behind long-term client value in this particular industry.

At the end, the utilisation of more sophisticated analytical tools, such as logistic regression modelling, has the potential to enhance forthcoming research efforts. This could yield more intricate insights into the relationships and trends present in the data.

Author approval

The full manuscript has been read and approved by all authors. Each listed author fulfils the requirements for authorship, and each author attests that the manuscript represents honest work.

Author contribution

S.A.A is the author of this research work and contributed to the planning of the research model, the literature review, the methodology and all the remaining sections of the manuscript and drafting it; W.K is the author of this work and contributed to the formulation and refinement of the research model’s hypotheses, and reviewing the manuscript; N.A is the author of this research and contributed to measurement development review, editing and introduction.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Sarah Ahmed Awaad, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sarah Ahmed Awaad

Sarah Ahmed Awaad, Assistant lecturer in Marketing major, Arab Academy for Science, Technology & Maritime Transport, Cairo.

Wael Kortam

Wael Kortam, Professor of Marketing, British University in Egypt.

Nihal Ayad

Nihal Ayad, Lecturer of Marketing, Arab Academy for Science, Technology & Maritime Transport, Cairo.

References

- Ali, M., Iraqi, K. M., Rawat, A. S., & Mohammad, S. (2018). Role of customer service skills on customer satisfaction and its effects on customer loyalty in Pakistan banking industry. South Asian Journal of Management Sciences, 12(2), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.21621/sajms.2018122.06

- Aliyev, F., Wagner, R., & Seuring, S. (2019). Common and contradictory motivations in buying intentions for green and luxury automobiles. Sustainability, 11(12), 3268. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123268

- Alpert, L., & Gatty, R. (1969). Product positioning by behavioral life-styles. Journal of Marketing, 33(2), 65–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224296903300215

- Alshibly, H. H. (2015). Customer perceived value in social commerce: An exploration of its antecedents and consequences. Journal of Management Research, 7(1), 17–37. https://doi.org/10.5296/jmr.v7i1.6800

- An, M. A., & Han, S. L. (2020). Effects of experiential motivation and customer engagement on customer value creation: Analysis of psychological process in the experience-based retail environment. Journal of Business Research, 120, 389–397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.02.04

- Berry, L. L.,Seiders, K., &Grewal, D. (2002). Understanding service convenience. Journal of Marketing, 66(3), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.66.3.1.18505

- Boyaci, T., & Ray, S. (2003). Product differentiation and capacity cost interaction in time and price sensitive markets. Manufacturing & Service Operations Management, 5(1), 18–36. https://doi.org/10.1287/msom.5.1.18.12757

- Cambra-Fierro, J., Gao, L. X., & Melero-Polo, I. (2021). The power of social influence and customer–firm interactions in predicting non-transactional behaviors, immediate customer profitability, and long-term customer value. Journal of Business Research, 125, 103–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.12.013

- Choo, H. J., Moon, H., Kim, H., & Yoon, N. (2012). Luxury customer value. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, 16(1), 81–101. https://doi.org/10.1108/13612021211203041

- Chua, B. L., Lee, S., Goh, B., & Han, H. (2015). Impacts of cruise service quality and price on vacationers’ cruise experience: Moderating role of price sensitivity. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 44, 131–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.10.012

- Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research. Pearson.

- Danes, J. E., & Lindsey-Mullikin, J. (2012). Expected product price as a function of factors of price sensitivity. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 21(4), 293–300. https://doi.org/10.1108/10610421211246702

- DiMingo, E. (1988). The fine art of positioning. The Journal of Business Strategy, 9(2), 34–38. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb039211 10303386

- Etikan, I., & Bala, K. (2017). Sampling and sampling methods. Biometrics & Biostatistics International Journal, 5(6), 00149. https://doi.org/10.15406/bbij.2017.05.00149

- Fang, B., Ye, Q., Kucukusta, D., & Law, R. (2016). Analysis of the perceived value of online tourism reviews: Influence of readability and reviewer characteristics. Tourism Management, 52, 498–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.07.018

- Gao, H., Zhang, Y., & Mittal, V. (2017). How does local–global identity affect price sensitivity? Journal of Marketing, 81(3), 62–79. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.15.0206

- Gomes, S., Lopes, J. M., & Nogueira, S. (2023). Willingness to pay more for green products: A critical challenge for Gen Z. Journal of Cleaner Production, 390, 136092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136092

- Granter, E., McCann, L., & Boyle, M. (2015). Extreme work/normal work: Intensification, storytelling and hypermediation in the (re) construction of ‘the New Normal’. Organization, 22(4), 443–456. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508415573881

- Hennigs, N., Wiedmann, K. P., Behrens, S., & Klarmann, C. (2013). Unleashing the power of luxury: Antecedents of luxury brand perception and effects on luxury brand strength. Journal of Brand Management, 20(8), 705–715. https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2013.11

- Hennigs, N., Wiedmann, K., Klarmann, C., Strehlau, S., Godey, B., Pederzoli, D., Neulinger, A., Dave, K., Aiello, G., Donvito, R., Taro, K., Táborecká-Petrovičová, J., Santos, C. R., Jung, J., & Oh, H. (2012). What is the value of luxury? A cross-cultural consumer perspective. Psychology & Marketing, 29(12), 1018–1034. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20583

- Home. Emaar Properties PJSC. (2023, September 4). https://www.emaar.com/

- Home. SODIC. (n.d.). https://www.sodic.com/

- Hou, L., &Tang, X. (2008). Gap model for dual customer values. Tsinghua Science and Technology, 13(3), 395–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1007-0214(08)70063-4

- Hsieh, A. T., & Chang, E. T. (2004). The effect of consumer participation on price sensitivity. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 38(2), 282–296. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.2004.tb00869.x

- Hsu, C. L., Chang, C. Y., & Yansritakul, C. (2017). Exploring purchase intention of green skincare products using the theory of planned behavior: Testing the moderating effects of country of origin and price sensitivity. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 34, 145–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2016.10.006

- Ingenbleek, P. T., Frambach, R. T., & Verhallen, T. M. (2010). The role of value-informed pricing in market-oriented product innovation management. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 27(7), 1032–1046. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5885.2010.00769.x

- Inspiring greatness. Rolls. (n.d.). https://www.rolls-roycemotorcars.com/en_US/inspiring-greatness.html

- Irvine, P. J., Park, S. S., & Yıldızhan, Ç. (2016). Customer-base concentration, profitability, and the relationship life cycle. The Accounting Review, 91(3), 883–906. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-51246

- Kaleka, A., & Morgan, N. A. (2019). How marketing capabilities and current performance drive strategic intentions in international markets. Industrial Marketing Management, 78, 108–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2017.02.001

- Kapferer, J. N., & Valette-Florence, P. (2021). Which consumers believe luxury must be expensive and why? A cross-cultural comparison of motivations. Journal of Business Research, 132, 301–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.003

- Kataria, S., &Saini, V. (2020). The mediating impact of customer satisfaction in relation of brand equity and brand loyalty. an Empirical Synthesis and Re-Examination. South Asian Journal of Business Studies, 9(1), 62–87. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAJBS-03-2019-0046

- Kato, T. (2021). Functional value vs emotional value: A comparative study of the values that contribute to a preference for a corporate brand. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights, 1(2), 100024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjimei.2021.100024

- Kaul, A., & Wittink, D. R. (1995). Empirical generalizations about the impact of advertising on price sensitivity and price. Marketing Science, 14(3_supplement), G151–G160. https://doi.org/10.1287/mksc.14.3.G151

- Kim, T., & Phua, J. (2020). Effects of brand name versus empowerment advertising campaign hashtags in branded Instagram posts of luxury versus mass-market brands. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 20(2), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2020.1734120

- Kock, N. (2017). “Common method bias: a full collinearity assessment method for PLS-SEM”. In Latan, H., & Noonan, R. (Eds.), Partial least squares path modeling (pp. 245–257). Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-64069-3.

- Kothari, C. (2017). Research methodology methods and techniques. New Age International (P) Ltd., Publishers, p. 91.

- Kotler, P., & Keller, K. L. (2016). Marketing management (15th global ed., pp. 803–829). Pearson.

- Kujala, S., & Väänänen-Vainio-Mattila, K. (2009). Value of information systems and products: Understanding the users’ perspective and values. Journal of Information Technology Theory and Application (JITTA), 9(4), 4.

- Kumar, V. (2008). Customer lifetime value – the path to profitability. Foundations and Trends in Marketing, 2(1), 1–96. https://doi.org/10.1561/1700000004

- Kumar, V., Aksoy, L., Donkers, B., Venkatesan, R., Wiesel, T., & Tillmanns, S. (2010). Undervalued or overvalued customers: Capturing total customer engagement value. Journal of Service Research, 13(3), 297–310. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670510375602

- Lemon, K. N., & Verhoef, P. C. (2016). Understanding customer experience throughout the customer journey. Journal of Marketing, 80(6), 69–96. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.15.0420

- Levin, K. (2006). Study design III: Cross-sectional studies. Evidence-Based Dentistry, 7(1), 24–25. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400375

- Lim, W. M., Ng, W. K., Chin, J. H., & Boo, A. W. X. (2014). Understanding young consumer perceptions on credit card usage: Implications for responsible consumption. Contemporary Management Research, 10(4), 209-220. https://doi.org/10.7903/cmr.11657

- Luxury Hotel Paris: 5-Star: Four Seasons Hotel George V, Paris. Luxury Hotel Paris | 5-Star | Four Seasons Hotel George V. (n.d.). https://www.fourseasons.com/paris/

- Mindrut, S., Manolica, A., & Roman, C. T. (2015). Building brands identity. Procedia Economics and Finance, 20, 393–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00088-X

- Monroe, K. B. (1990). Price: Marketing profitable decisions (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Natarajan, T., Balasubramanian, S. A., & Kasilingam, D. L. (2017). Understanding the intention to use mobile shopping applications and its influence on price sensitivity. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 37, 8–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2017.02.010

- Niedrich, R. W., Weathers, D., Hill, R. C., & Bell, D. R. (2009). Specifying price judgments with range–frequency theory in models of brand choice. Journal of Marketing Research, 46(5), 693–702. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.46.5.693

- Official Ferrari website. (n.d.). https://www.ferrari.com/en-EG

- Overview of all Porsche Models - Porsche AG. Porsche AG - Dr. Ing. h.c. F. Porsche AG. (n.d.). https://www.porsche.com/international/models/

- Özkan, P. E., & Evrim, D. (2020). The mediating role of price sensitivity in the effect of trust and loyalty to luxury brands on the brand preference. Управленец, 11(6), 70–84. https://doi.org/10.29141/2218-5003-2020-11-6-6

- Palawatta, T. M. B. (2015). Waiting times and defining customer satisfaction. https://doi.org/10.31357/vjm.v1i1.365

- Rezzano, S., & Fallini, F. (2021). Defining luxury cars: A comprehensive study of critical success factors and managerial strategies. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.18463.89764

- Rundh, B. (2013). Linking packaging to marketing: How packaging is influencing the marketing strategy. British Food Journal, 115(11), 1547–1563. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-12-2011-0297

- Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2009). Research methods for business students. Pearson Education.

- Scholtz, S. E. (2021). Sacrifice is a step beyond convenience: A review of convenience sampling in psychological research in Africa. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 47(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v47i0.1837

- Segarra-Moliner, J. R., & Moliner-Tena, M. Á. (2022). Engaging in customer citizenship behaviours to predict customer lifetime value. Journal of Marketing Analytics, https://doi.org/10.1057/s41270-022-00195-2

- Sheth, J. N.,Newman, B. I., &Gross, B. L. (1991). Why we buy what we buy: A theory of consumption values. Journal of Business Research, 22(2), 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-2963(91)90050-8

- Shukla, P. (2012). The influence of value perceptions on luxury purchase intentions in developed and emerging markets. International Marketing Review, 29(6), 574–596. https://doi.org/10.1108/02651331211277955

- Simon, H., & Fassnacht, M. (2019). Price strategy. In Price management: Strategy, analysis, decision, implementation (pp. 29–84). Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-99456-7_2

- Sjödin, D., Parida, V., Jovanovic, M., & Visnjic, I. (2020). Value creation and value capture alignment in business model innovation: A process view on outcome-based business models. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 37(2), 158–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12516

- Smith, H. A., & McKeen, J. D. (2005). Developments in practice XVIII-customer knowledge management: Adding value for our customers. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 16(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.01636

- Tak, P. (2020). Antecedents of luxury brand consumption: An emerging market context. Asian Journal of Business Research, 10(2), 23–44. https://doi.org/10.14707/ajbr.200082

- The Ritz-Carlton - Luxury Hotels & Resorts. Carlton. (n.d). https://www.ritzcarlton.com/

- Venkatesan, R., & Kumar, V. (2004). A customer lifetime value framework for customer selection and resource allocation strategy. Journal of Marketing, 68(4), 106–125. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.68.4.106.42728

- Waluya, A. I., Iqbal, M. A., & Indradewa, R. (2019). How product quality, brand image, and customer satisfaction affect the purchase decisions of Indonesian automotive customers. International Journal of Services, Economics and Management, 10(2), 177–193. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSEM.2019.100944

- Yue, B., Sheng, G., She, S., & Xu, J. (2020). Impact of consumer environmental responsibility on green consumption behavior in China: The role of environmental concern and price sensitivity. Sustainability, 12(5), 2074. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12052074

- Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, 52(3), 2–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298805200302

- Zhu, W., Huangfu, Z., Xu, D., Wang, X., & Yang, Z. (2022). Evaluating the impact of experience value promotes user voice toward social media: Value co-creation perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 969511. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.969511