Abstract

Despite the inclusive beneficiation inherent in Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), emergent literature suggests that it has become a serendipitous differentiation strategy. However, scarce in pre-emerging economies are integrated and robustly tested models linking the CSR dimensions to consumer brand preference. Based on the sustain-centric model, this research examines the impact of perceived economic, social and environmental CSR on corporate brand credibility, consumer brand attitude and consumer brand preference. A causal research design enrolling a Covariance-Based Structural Equation Modelling (CB-SEM) methodology is employed to examine the proposed structural relationships in IBM SPSS AMOS (used under license). Using convenience sampling, customers in the telecommunications sector in Harare were sampled and 266 valid responses estimated model parameters. Positive and significant effects were observed between the dimensions of CSR (perceived economic, environmental and social CSR), corporate brand credibility and consumer brand attitude, save for environmental CSR and consumer brand attitude. Corporate brand credibility positively and significantly influenced both consumer brand attitude and consumer brand preference whilst the positive impact of consumer brand attitude on consumer brand preference was also evident. Our research also contributes that consumers in developing economies relatively score lower in the environmentalism orientation index as the causal link between environmental CSR and consumer brand attitudes did not confirm a positive and significant impact. This paper enlightens corporate managers on the influence of CSR on brand acceptance in consumer markets. Further, it also demonstrates the relative impacts of the CSR dimensions, providing a proxy for resource allocation on competing CSR projects.

1. Introduction

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has emerged a topical subject in the contemporary marketing debates. CSR includes all activities directed towards attainment of diverse stakeholder interests that befall corporate organisations (Adewole, Citation2023; Vera-Martínez et al., Citation2022). Traditionally, the objective of the firm was to maximize profits for its shareholders (Single Bottom Line) (Lysons & Farrington, Citation2020; Schwartz, Citation2020). Today, the firm is encircled by more inclusive perspectives incorporating a plethora of stakeholder concerns (Cheung et al., Citation2019; Mukucha et al., Citation2023). This culminated into the Triple Bottom Line (TBL) concept, a philosophy centered on achieving sustainable beneficiation to the profit, people and planet (Asmussen & Fosfuri, Citation2019; Mukucha et al., Citation2023). Whilst diverse perceptions of CSR have been raised (Aydin, Citation2019), its most ethical justification has been society beneficiation (Hsu et al., Citation2022), despite the market perceptions and financial performance accruing to the firm.

In Zimbabwe, there are no legally recognised CSR regulatory frameworks and prevailing works emerge out of self-regulation business models and social accountability (Fundira & Mupfungidza, Citation2022; Mapokotera et al., Citation2023). The telecommunications sector in Zimbabwe has been by far the most dominant sector in Zimbabwe. Cholera and COVID-19 campaign initiatives, employee welfare schemes, annual blood donation projects, building of schools in both urban and rural areas, provision of textbooks in schools, development of ICT centres, funding the education of gifted students, buying drugs and medical equipment for hospitals have been corporate funded (Fundira & Mupfungidza, Citation2022; Manuere et al., Citation2022). Despite the integrated CSR initiatives by the telecommunications sector, cut throat competition is confirmed by market share fluctuations in quarterly reports (Fundira & Mupfungidza, Citation2022; POTRAZ, Citation2023). Heavy price competition, restricted access to intermediaries, exclusively owned service infrastructure, service agents’ monopolization and refusal to synchronise their mobile money services has defined the intensity of their competitive landscape (Manuere et al., Citation2022; POTRAZ, Citation2023). Whilst concerted regulatory efforts imploring them to share key processes and gain operational synergies and economies of integration have been evident, competitive fears rendered them fruitless.

Despite their shareholding disparities, the intensity of CSR in the telecommunications sector has attracted diverse opinions amongst researchers, economists, opinion leaders and consumers themselves (Manuere et al., Citation2022; Shoko et al., Citation2021). Suggestions that CSR in contested markets is a differentiation strategy have been raised (Saeidi et al., Citation2015), whilst CSR enthusiasts argue that it is a culmination of their embedded societal values and inclusive corporate culture ingrained in their corporate citizenship. Whilst the corporate motivations behind CSR in the telecommunications sector in Zimbabwe are unclear, emergent perspectives in literature suggest that CSR has become a relationship marketing strategy. Consumer concerns for more socially responsible firms and brands have been reported in previous research (Agrawal & Gupta, Citation2018; Mapokotera et al., Citation2023; Vera-Martínez et al., Citation2022). Despite suggestions that not all consumers are enticed by CSR efforts when evaluating brands (Currás-Pérez et al., Citation2018; Peloza & Shang, Citation2011), firms actively supporting the sustainability thrust have been earmarked to achieve long-run market dominance.

Although the telecommunications sector is highly competitive, its core service differentiation is insignificant such that subjective differences in consumer preferences play a pivotal role in market performance (Fundira & Mupfungidza, Citation2022; Makudza et al., Citation2020). Having significant CSR presence in Zimbabwean telecommunications, this merits the nexus between perceived CSR and consumer brand preference an empirical enquiry. Despite its recent widespread application in Zimbabwe, the impact of CSR on a firm’s market-based assets remain an under-researched subject as most firms were previously immersed in the Single Bottom Line (SBL) philosophy (Lysons & Farrington, Citation2020; Mukucha et al., Citation2023). Further, the few available studies tested intuitive models using linear regression methods, providing relatively lesser statistical inferences. Given that limitation, the current study uses a CB-SEM methodology to evaluate the proposed model.

Further, although CSR research has been expended in recent decades, most research models have been largely situated on subjective theory models. Stand-alone frameworks and decomposed models from the sustain-centric model (Niskala & Tarna, Citation2003), stakeholder theory (Simmons, Citation2004), institutional isomorphism theory (Powell & Di Maggio, Citation1991), societal marketing theory (Armstrong & Kotler, Citation2008) and the triple bottom line framework (Elkington, Citation2018) have attempted to predict the antecedents and outcomes of CSR. More so, the generalization and oversimplification of the CSR measurement in most studies e.g. Arachchi and Samarasinghe (Citation2023), Lai et al. (Citation2010) and Tan et al. (Citation2022) has caused scarcity of comprehensive conceptual clarification originating from marketing. Arguably, this is explained by the width of CSR activities associated with good corporate citizenship. Diverse sub-constructs e.g. legal, cultural, financial, political, economic, social and environmental CSR (Puriwat & Tripopsakul, Citation2021) have made its operationalization highly subjective to corporate objectives and environmental context. Based on the contemporary sustainability thrust, the sustain-centric model informs the adoption of economic, social and environmental CSR for this study.

More so, consumers’ CSR dispositions towards firms have not been clearly delineated into market and corporate brand outcomes. Most studies e.g. Mohammed and Rashid (Citation2018), Fundira and Mupfungidza (Citation2022) and Tan et al. (Citation2022) have focused on overall brand image and loyalty; hence the current research model proposes the simultaneous effects of CSR on the credibility of the corporate brand as well as consumer attitudes towards its products. Furthermore, whilst substantial behavioral literature confirms that attitude formation precedes actual behaviors (Ajzen, Citation2020; Dangaiso, Citation2023; Dilotsotlhe & Akbari, Citation2021; Muposhi et al., Citation2015; Rosenberg & Hanland, Citation1960), this research argues studies that reported the direct impact of CSR on consumer brand behavior lack sound theoretical merit in the domain of consumer behavior. Thus, we propose consumer brand attitude as the link between CSR and consumer brand preference.

In addition, the study proposes CSR to have an antecedent role on consumer brand preference than brand loyalty as over-generalized in most studies developing economies e.g. Fundira and Mupfungidza (Citation2022) and Manuere et al. (Citation2022). This study views brand loyalty as a long-term, incremental outcome of initial brand preference made by consumers as determined by key underlying variables. Thus, this research integrates the sustain-centric CSR dimensions and, previously researched, albeit discretely, market and corporate brand outcomes that relate to consumer brand preferences in the context of a developing economy. Thus, causal linkages between perceived CSR, corporate brand credibility, consumer brand attitude and consumer brand preference were proposed and examined.

This research advances empirical CSR research, thus, it extends literature in the domains of CSR, consumer behavior and brand management. The significance of the study further stems from its capability to enlighten corporates on effectively harnessing CSR strategies to maximize brand acceptance and preference in consumer markets. Further, the findings of the research inform practitioners in the telecommunications sector, other industries alike, about the investments and potential gains from CSR in the context of a pre-emerging economy, as developing countries are more susceptible to economic, societal and environmental challenges, which make corporate CSR interventions more imperative. More so, the study highlights the relative significance of the CSR dimensions to consumer brand preference, which can serve as a key proxy for determining resource allocation given the multiple CSR initiatives at the disposal of the firm. Further, in terms of contribution to theory, this research validates the sustain-centric framework in the context of CSR (inclusive development) among other pillars of sustainability. The subsequent sections of the paper focus on literature review and development of hypotheses, research methodology, results, implications and conclusions.

2. Literature review

2.1. Theoretical perspectives

Corporate social responsibility is grounded in a number of frameworks that include the societal marketing theory (Armstrong & Kotler, Citation2008), Triple Bottom Line framework (Elkington, Citation2018), stakeholder theory (Simmons, Citation2004) and the sustain-centric paradigm (Niskala & Tarna, Citation2003). The societal marketing theory recognizes the need for corporates to go beyond mutual value exchange relationships fixated in the classic dyad involving the business and its customer. Beyond the traditional transactional orientation is a mandate for the business to consider satisfying the needs of the society (Cheung et al., Citation2019; Hsu et al., Citation2022). From this perspective, CSR emerged as a powerful way of supporting long-term relationships between the corporates and their stakeholders (Adewole, Citation2023; Armstrong & Kotler, Citation2008). Societal marketing has also fueled long-term concerns such as consumer longevity, environmental preservation, employee welfare and paradigms in favor of sustainability (Vera-Martínez et al., Citation2022) e.g. green marketing have been popularized (Ha, Citation2021).

The Triple Bottom Line (TBL) framework defines a corporate model that identifies the ‘people, planet and profits’ as the fundamental objectives that a firm pursues (Elkington, Citation2018). The TBL presents a significant departure from the Single Bottom Line (SBL) model where firms where focused on achieving profits for shareholders only (Mukucha et al., Citation2023). The TBL established that corporate entities by more socially and environmentally responsible through sustained CSR investments and adoption of inclusive operational models that guide corporate activities (Elkington, Citation2018; Mukucha et al., Citation2023). The TBL framework has been one of the most accredited models in CSR literature as it defined the departure of firms from sole profiteering to its broader goals e.g. improving shareholder value, customer satisfaction, employee welfare, community welfare and environmental conservation.

The stakeholder theory views a firm as an institution that exists to serve the interests of a plethora of entities that surround it (Simmons, Citation2004). The stakeholder theory presents a major departure from the traditional view of the firm where the firm was an entity immersed in maximizing profits for the shareholders too (Alvarado-Herrera et al., Citation2017; Lai et al., Citation2010). The stakeholder approach entails that firms are obliged to satisfy the interests of customers, suppliers, communities, employees, shareholders, pressure groups and statutory organisations (Asmussen & Fosfuri, Citation2019). CSR implies resource establishments directed towards serving communities hence CSR is rooted in the stakeholder theory (Adewole, Citation2023; Asmussen & Fosfuri, Citation2019).

The sustain-centric paradigm has been a useful framework in explaining firms’ CSR attitude and behavioral response towards sustainability calls (Bravo et al., Citation2012; Niskala & Tarna, Citation2003; Panwar et al., Citation2006; Vera-Martínez et al., Citation2022). Under the framework, three pillars anchoring sustainability have been attributed to economic, social and environmental commitments. Past research has evaluated CSR as a multidimensional construct based on economic CSR, social CSR and environmental CSR e.g. Bravo et al. (Citation2012) and Vera-Martínez et al. (Citation2022).

Perceived economic CSR pertains financial aspects in the way a company manages business relationships with its stakeholders. Using the model, economic factors that affect the relationship between firms and their stakeholders are considered. Its indicators include offering high quality and safe products, fair pricing methods, fair trade practices, tax compliance, sharing benefits from economies of scale with customers, fair reporting standards, integration of supply chains and employee compensation (Bravo et al., Citation2012; Hsu et al., Citation2022; Mody et al., Citation2017; Vera-Martínez et al., Citation2022).

Secondly, social CSR focuses on consumer perceptions of the firm on adherence to ethical standards of corporate behavior and investing in community welfare programs (Bianchi et al., Citation2019). Social CSR includes funding directed towards the social causes. This incorporates funding towards the less privileged segments, natural disasters and public well-being. social CSR through social welfare benefits, e.g. food aid and infrastructural development, community sanitation and rehabilitation, provision of education, health and other key amenities has been observed (Currás-Pérez et al., Citation2018; Vera-Martínez et al., Citation2022).

Lastly, environmental CSR measures customer perceptions of the firm’s commitment towards environmental considerations, ecological balance and preservation of the ecosystem (Mukucha et al., Citation2023; Vera-Martínez et al., Citation2022). Environmental CSR fosters preservation of the environment and corporates have participated by advocating for environmental safety, cleanliness, adherence to high manufacturing standards, prevention of environmental hazards, reduce-recycle-reuse waste management, reclamation of dilapidated or abandoned worksites, green manufacturing, safe disposal of manufacturing waste and lean production (Bravo et al., Citation2012; Mukucha et al., Citation2023; Vera-Martínez et al., Citation2022).

Cognisant of these CSR dimensions that emerge from the sustain-centric paradigm, researchers have conceptualized and operationalized CSR as a multi-dimensional construct comprised of economic CSR, social CSR and environmental CSR (Bravo et al., Citation2012; Hsu et al., Citation2022; Vera-Martínez et al., Citation2022). This research adopts the sustain-centric framework to evaluate the impact of perceived CSR on consumer brand attitude, corporate brand credibility and consumer brand preference.

2.2. Development of hypotheses

2.2.1. Perceived CSR and corporate brand credibility

This paper conceptualizes perceived CSR as a multi-dimensional construct comprised of economic CSR, social CSR and environmental CSR (Bravo et al., Citation2012; Vera-Martínez et al., Citation2022). Economic CSR has been found to be a key CSR dimension in extant literature. Corporate brand credibility is defined as the consumers’ perception of a firm’s reputation that, in this context, is derived from its CSR involvements (Adewole, Citation2023; Aksak et al., Citation2016). In other words, it represents the corporate image of the business entity, i.e. how the public perceives the firm to be (Agrawal & Gupta, Citation2018; Vera-Martínez et al., Citation2022). Corporate brand credibility denotes consumers’ perception of the firm arising from the firm’s attitudes and behaviors. It culminates from both a firm’s image and reputation for its corporate behaviors.

The study of Vera-Martínez et al. (Citation2022) reported that fair pricing, corporate tax obligations, good internal marketing through sound remuneration influence firm credibility. Further, corporate image was found to be influenced by consumer’s perceptions of a firm’s economic behavior (the way it conducts business with other stakeholders) (Mapokotera et al., Citation2023; Mohammed & Rashid, Citation2018). In Zimbabwe, the telecommunications sector has a volatile pricing model and price competition has been evident (Fundira & Mupfungidza, Citation2022; Shoko et al., Citation2021). However, other dimensions of economic CSR such as high quality products, employee welfare schemes, tax compliance have been varied across players. For example, Telecel failed to honor its obligations to the government and had its license previously withheld. However, in the light of empirical bases, we expect that economic CSR leads to good corporate brand credibility. Thus, we proposed that;

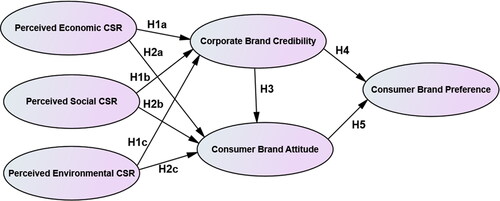

H1a: Perceived economic CSR positively and significantly influences corporate brand credibility in the telecommunications sector in Zimbabwe.

Social CSR involves the investment towards the social cause or funding initiatives towards vulnerable segments of the community. In Zimbabwe the telecommunications sector has invested towards COVID-19 funding, provision of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), quarantine centres, food and medical supplies during COVID-19 (Fundira & Mupfungidza, Citation2022; Shoko et al., Citation2021). Further, the Chimanimani, Tugwi-Mukosi floods survivors received food, shelter, rehabilitation, building new schools, roads and clinics, received more funding. Vulnerable children have received scholarships through the Joshua Nkomo Scholarship, Higher Life Foundation and the Capernaum trust (Manuere et al., Citation2022). Further, empirical research evidence shows that social CSR had positive impact of firm credibility (Vera-Martínez et al., Citation2022) and corporate social competitiveness (Mapokotera et al., Citation2023). Given that, this study proposed that;

H1b: Perceived social CSR positively and significantly influences corporate brand credibility in the telecommunications sector in Zimbabwe.

Environmental CSR has become a key topical area in the quest for sustainability (Khojastehpour & Johns, Citation2010). Firms have an obligation to reduce, recycle and re-use in their sustainable waste disposal frameworks (Mukucha et al., Citation2023). Green manufacturing, climate responsibility, natural resource utilization and lean manufacturing practices have been found to be positively correlated with environmental sustainability (Khojastehpour & Johns, Citation2010). However, the study of Vera-Martínez et al. (Citation2022) found an insignificant effect of environmental CSR on firm credibility. In contrast, research studies e.g. Manuere et al. (Citation2022) and Mapokotera et al. (Citation2023) note that firm environmentalism leads to reciprocal consumer behavior and corporate social competitiveness, respectively. In the context of the telecommunications sector in Zimbabwe, major players have been supporting environmental sustainability through road rehabilitation, resource utilization, construction of dams for irrigation and reclamation of degraded land sites. Consequentially, we formulated the following hypothesis;

H1c: Perceived environmental CSR positively and significantly influences corporate brand credibility in the telecommunications sector in Zimbabwe.

2.2.2. Perceived CSR and consumer brand attitude

Consumer attitudes towards a brand refer to a pre-dominant disposition of a consumer or individual towards a brand, object, person or business entity (Ajzen, Citation2020; Armstrong & Kotler, Citation2008; Schiffman & Kanuk, Citation2004). Whilst hypotheses H1a, H1b and H1c relate to consumer perceptions of the credibility of the corporate entity, H2a, H2b and H2c focus on the proposed relations between perceived CSR dimensions and consumers’ attitudes towards the product brands as opposed to the image and reputation perception of the firm.

This study views competitive pricing and superior product quality as closely related to the product on the market than other related aspects because they define the firm’s interactions with their customers. Therefore, firms observed to be compliant to economic CSR have a higher propensity to translate that consumer perception into positive brand attitude in competitive markets. Dimensions such as fair labor practices and good internal marketing also closely affect market brands perceptions in most conventional markets (Mapokotera et al., Citation2023; Vera-Martínez et al., Citation2022). The employees are the internal customers who carry the brand ambassadorial role in the markets (Benjarongrat & Neal, Citation2017). However, price competition is predominant in Zimbabwean markets and employee welfare perceptions are highly variable. Meanwhile, Zimbabwe has the highest data prices in the world and its effects has not been examined (POTRAZ, Citation2023). Research evidence suggests that perceived economic CSR affects market success of product brands (Manuere et al., Citation2022; Shoko et al., Citation2021). Given that, we hypothesised that;

H2a: Perceived economic CSR positively and significantly influences consumer brand attitude in the telecommunications sector in Zimbabwe.

Social CSR has been defined and its variants have been identified in the development of H1b. It incorporates all corporate investments directed towards alleviation of societal challenges such as poverty, health access, education and community wellbeing. For example., Econet Wireless and POTRAZ fund youth rehabilitation and correctional services centres (Fundira & Mupfungidza, Citation2022; Manuere et al., Citation2022). Although no empirical research has been drawn on the relationship between perceived social CSR and consumer brand attitude, we expect that consumers, as the ‘resident societal members’, are keen to reciprocate the corporate deeds directed towards its less priviledged segments. Manuere et al. (Citation2022) found the positive effect of social CSR on generic consumer behavior in the telecommunications industry in Zimbabwe. Further, a related study by Vera-Martínez et al. (Citation2022) reported that social CSR has a positive effect on brand identification. Given the empirical bases, we formulated the following hypothesis.

H2b: Perceived social CSR positively and significantly influences consumer brand attitude in the telecommunications sector in Zimbabwe.

Concerns for environmental safety have proliferated in the recent decade as efforts towards environmental sustainability (Khojastehpour & Johns, Citation2010). Further, concerns for environmentally sensitive firms have risen and initiatives such as greener manufacturing and operations, lean production, and sustainable waste disposal methods (Agrawal & Gupta, Citation2018). Research evidence shows that environmental sensitivity has emerged one of key dimensions being considered by consumers when choosing brands and even employers (Vera-Martínez et al., Citation2022). However, environmental sustainability action has been slow in developing economies such as Zimbabwe as economic constraints continue to marginalize their sustainability agenda (Dangaiso, Citation2023; Muposhi et al., Citation2015). However, Vera-Martínez et al. (Citation2022) reported an insignificant effect of environmental CSR on brand identification. This has been often conceptualised as the green dilemma or and green rhetoric (Davari & Strutton, Citation2014; Muposhi et al., Citation2015). Despite that, related evidence suggest that perceived environmental CSR has a positive correlation with consumer brand intentions (Arachchi & Samarasinghe, Citation2023). Given the importance of environmentalism in curbing adverse sustainability problems faced by consumers, we expect perceived environmental CSR to positively influence consumer brand attitude. The following hypothesis was proposed;

H2c: Perceived environmental CSR positively and significantly influences consumer brand attitude in the telecommunications sector in Zimbabwe.

2.2.3. Corporate brand credibility and consumer brand attitude

Consumers tend to create associations with corporate brands that have a positive image (Adewole, Citation2023; Agrawal & Gupta, Citation2018). The corporate’s credibility reflects the firm’s image accrued from the way it discharges its business. Corporate brand credibility resembles both reputation and image perceptions of consumers towards the firm (Mahmood & Bashir, Citation2020, p. 1). Other researchers e.g. Vera-Martínez et al. (Citation2022) conceptualised corporate brand credibility as firm credibility. An attitude causes one to behave positively or negatively towards that particular object or product (Schiffman & Kanuk, Citation2004). Corporate brand image has been reported to influence consumer brand affiliations (Aydin, Citation2019; Puriwat & Tripopsakul, Citation2021; Ramesh et al., Citation2018). In Zimbabwe telecommunications sector, we expect CSR-based corporate brand credibility to positively relate to consumer attitudes towards the firm’s products. Consequentially, we hypothesized that;

H3: Corporate brand credibility positively and significantly influences consumer brand attitude in the telecommunications sector in Zimbabwe.

2.2.4. Corporate brand credibility and consumer brand preference

CSR has been observed to trigger cognitive beliefs in minds of stakeholders about the firm’s responsible corporate behavior (Adewole, Citation2023; Bianchi et al., Citation2019). Consumer brand preference is defined as a predominant propensity to select a particular brand for purchase despite competitive pressures from other brands (Liu et al., Citation2014; Puriwat & Tripopsakul, Citation2021). Extant literature supports that corporate brand image positive relates to purchase intentions and brand loyalty (Alvarado-Herrera et al., Citation2017; Asmussen & Fosfuri, Citation2019; Cheung et al., Citation2019; Vera-Martínez et al., Citation2022). Thus, in the Zimbabwean telecommunications context, we expect corporate brand credibility to have a positive effect on consumers’ brand selection when purchasing products and services. Thus, the study proposed that;

H4: Corporate brand credibility positively and significantly influences consumer brand preference in the telecommunications sector in Zimbabwe.

2.2.5. Consumer brand attitude and consumer brand preference

Extant literature views consumer attitude as a key precursor to consumer brand behaviors in most consumer markets (Adewole, Citation2023; Dangaiso, Citation2023; Jeon et al., Citation2020). The tri-component model of attitude formation (Rosenberg & Hanland, Citation1960) opines that attitudes develop mentally (cognitive), emotionally (affective) and behaviorally (conative). This implies that positive metal associations (initiation stage), translate into a brand feelings (middle stage) and ultimately trigger a purchase behavior (final stage) (Armstrong & Kotler, Citation2008; Schiffman & Kanuk, Citation2004). A positive attitude towards brand offered by a firm is thus expected to stimulate purchase decisions skewed towards that brand (Jeon et al., Citation2020; Puriwat & Tripopsakul, Citation2021).

However, divergent literature notes that an attitude-behavior gap has been observed in consumer studies on sustainability subjects where positive consumer attitudes did not translate into intended purchase behaviors. This has been conceptualized as the green dilemma (Muposhi et al., Citation2015), green rhetoric (Johnstone & Tan, Citation2015), beliefs-consumption behaviors gap (Davari & Strutton, Citation2014), attitude-behavior gap (Peattie, Citation2010) and purchase intentions-behaviors gap (Mendleson & Polonsky, Citation1995). However, there is also considerable literature supporting the causal link between consumer brand attitude and purchase intention (Arachchi & Samarasinghe, Citation2023; Aydin, Citation2019; Jeon et al., Citation2020). In the Zimbabwean context, we also expect that consumer brand attitude will positively relate to consumer brand preference. Consequentially, the following hypothesis was formulated;

H5: Corporate brand attitude positively and significantly influences consumer brand preference in the telecommunications sector in Zimbabwe.

illustrates the hypothesised research model.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Design, population and sampling

The purpose of the research was to examine causal relationships between perceived CSR, corporate brand credibility, consumer brand attitude and consumer brand preference. The study adopted a causal research design to evaluate the proposed relationships between theoretical constructs in the proposed model. This design is suited to studies that seek to explain cause and effect relationships between variables drawn in a conceptual framework (Hair et al., Citation2020). The target population were customers of telecommunications companies with confirmed operationalized CSR projects across Zimbabwean provinces. The study area was the Harare Metropolitan Province; therefore, customers in its Central Business District (CBD) were used as the unit of analysis. The Harare CBD was selected based on the heterogeneity of consumers who visit the capital from different parts of the country (Zimbabwe).

Since some the conditions needed for random sampling were not satisfied, e.g. unavailability of a sampling frame, convenience sampling was used (Hair et al., Citation2020). Although probabilistic methods better resemble the distribution of population parameters, we used convenience sampling to collect data from population elements that were available (Saunders et al., Citation2018). Further, 385 structured questionnaires were distributed. The item-to-response ratio should range from 1: 4 to 1: 10 for each set of variables (Chepchirchir & Leting, Citation2015). As 25 measurement (observed) items were adopted, 100–250 samples were considered sufficient in this study. Further, sample size determination was also based on sample sizes used in related studies, resource constraints and completion rates.

3.2. Measures

The instrument that was employed in this study was adopted from literature. These were conceptualised as perceived economic CSR, perceived social CSR, perceived environmental CSR, corporate brand credibility (Vera-Martínez et al., Citation2022), consumer brand attitude (Puriwat & Tripopsakul, Citation2021) and consumer brand preference (Jeon et al., Citation2020). Constructs were measured on a 7-point Likert-scale from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7). A pretest was conducted based on 15 finalist students from a local university (Saunders et al., Citation2018).

3.3. Data collection procedures and ethical compliance

This study obtained ethical clearance from the Research and Ethics Committee of Chinhoyi University of Technology. Prior to data collection, the purpose of the research was shared and participation was also voluntary. In line with the ethical principles in consumer research, all the participants provided their prior verbal informed consent. The type of consent adopted in a study depends on nature of the study, type of participants and research context (Saunders et al., Citation2018). Verbal consent is permissible in opinion or perception surveys that use self-reported data. More so, the data collection instrument also provided information pertaining to the participant’s agreement to participate in the study. All participants confirmed their consent on the questionnaire.

Furthermore, the study was conducted compliant to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. At different times of the day, we used the mall intercept method to approach customers, seek permission and deliver questionnaires that were submitted upon completion. We used filter questions to eliminate non-elements of the targeted population from the sample. To prevent common methods bias, the measurement items were mixed and respondents were educated that no answers were correct nor wrong. Participants’ confidentiality and privacy were also strictly observed prior and post the data collection phase (Saunders et al., Citation2018).

3.4. Data analysis methods

A two-step Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) in IBM SPSS (used under IBM license) procedure was employed to generate the findings (Anderson & Gerbin, Citation1988). On the measurement model, unidimensionality was ensured by retaining items with factor loadings that were equal or greater than 0.7 (Byrne, Citation2013; Kline, Citation2016). Convergent validity was examined using Average Variance Extracted (AVE) (AVE=/> 0.5) (Kline, Citation2016). Discriminant validity was checked using the Fornell & Larcker (Citation1981) criterion (square root of AVE > inter-construct correlations). Reliability was assessed using composite reliability (CR > or = 0.7 (Byrne, Citation2013; Kline, Citation2016). The group of fit indices used in this study belong to absolute fit indices (Normed Chi square (x2/df), Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), Root Mean Residual (RMR), and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA); and incremental fit indices (Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) and Normed Fit Index (NFI) (Collier, Citation2020; Kline, Citation2016). The Maximum likelihood method was used to estimate model parameters and at 95% confidence interval, t-statistics greater than 1.96 were adjudged significantly different from zero (p < 0.05).

4. Results

4.1. Demographic profile

The study had a response rate of 77.4% (298) and 266 were valid. The major highlights were that there were 123 (53.8%) females, 140 (52.6%) formally employed, 162 (60.9%) of the 18–35 age group and 170 (63.9%) bachelor’s degree holders. shows the full demographic profile of the participants.

Table 1. Demographic profile.

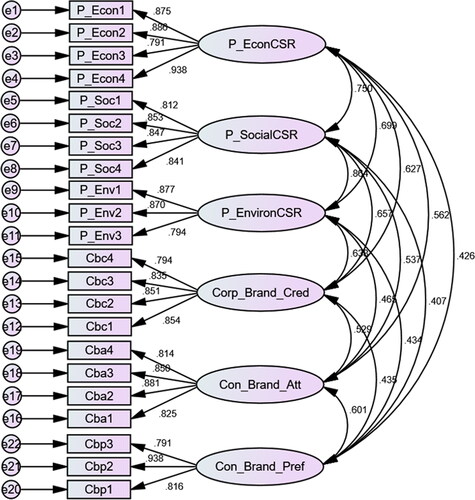

4.2. Assessment of the measurement model

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was done in line with the two-step data analysis procedure for SEM (Anderson & Gerbin, Citation1988). Unidimensionality was assessed by inspecting the standardized factor loadings. A factor loading represents the correlation between a latent construct and an observed variable, establishing how well an observed variable explains variance in the latent construct (Kline, Citation2023). According to Kline (Citation2016), factor loadings should be at least 0.7. The loadings ranged from 0.791 to 0.938, except P_Econ5 (0.660), P_Env4 (0.682) and P_Env5 (0.620) which were subsequently deleted. We did not retain these items since we had observed items greater than the minimum required (3 per factor) hence those which did not sufficiently reflect significant variance on their parent constructs were excluded from further analysis (Byrne, Citation2013; Kline, Citation2016). Thus, the requirement of unidimensionality was met.

Secondly, the model fit was examined in order to establish how well the sample variance-covariance matrix fits the hypothesized model’s variance-covariance matrix (Collier, Citation2020; Kline, Citation2016). Inspection of the modification indices and the standardized residual covariance matrix suggested that no further re-specification was needed to improve the model. The 6-factor CFA model produced a very good fit. The absolute fit were within acceptable values (Anderson & Gerbin, Citation1988; Byrne, Citation2013; Kline, Citation2016) (CMIN = 445.59, degrees of freedom (df) = 194, x2/df = 2.29, RMR = 0.038, GFI = 0.901, RMSEA = 0.070), and so were the relative fit indices (CFI = 0.947, TLI = 0.937, NFI =0.911, IFI = 0.948).

Further, a statistical test for Common Methods Variance (CMV) was run using Harman’s single factor test (Collier, Citation2020; Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). An Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) procedure confirmed that no factor accounted for 50% or more of the total variance (31.27%). More so, a comparison of the model fit between a one-factor model and the six-factor model was done (Kline, Citation2016). The one-factor model had the worst fit (CMIN = 1993.16, df = 209, x2/df = 9.53, RMR = 0.099, GFI = 0.529, RMSEA = 0.179, CFI = 0.626, TLI = 0.586, NFI = 0.601, IFI = 0.628) relative the six-factor CFA model (CMIN = 445.59, df = 194, x2/df = 2.29, RMR = 0.038, GFI = 0.901, RMSEA = 0.070, CFI = 0.947, TLI = 0.937, NFI = 0.911, IFI = 0.948). Given these results, CMV was not a problem in this study.

Convergent validity of the constructs was assessed using statistically significant factor loadings, Average Variance Extracted (AVE) and Squared Multiple Correlations (SMC). According to Kline (Citation2016) convergent validity is satisfied when AVE is at least 0.5, CR > AVE and SMC ≥ 0.5 (). Further, the factor loadings were greater than 0.5 and they were all statistically significant (p < 0.01). The required conditions were all satisfied, therefore convergent validity was present. To establish discriminant validity, the Fornell & Larcker (Citation1981) criterion was used. According to Fornell and Larcker, the square root of the AVE should greater than the correlations between the construct and any other variable in the model (). This condition was met except for Perceived Environmental CSR and Perceived Social CSR. However, this was deemed inconsequential as literature suggests that the two constructs are conceptually related (Bravo et al., Citation2012; Vera-Martínez et al., Citation2022). We assessed internal consistency using Cronbach alpha (CA) and Composite Reliability (CR). The composite reliability and Cronbach alpha values were all above 0.7, demonstrating adequate construct reliability (Nunnally & Bernstein, Citation1994). The scale items regarding customer perceptions of their mobile telecommunications provider and their psychometric properties are in and illustrates the measurement model.

Table 2. Psychometric properties of the measurement model.

Table 3. Assessment of discriminant validity.

4.3. Assessment of the structural model

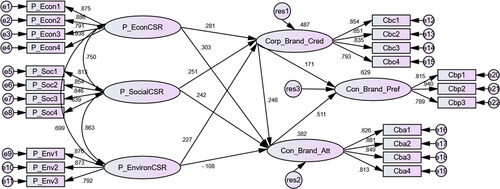

The assessment of the structural model was done based on the model fit, significance of path estimates and its predictive power (Byrne, Citation2013; Kline, Citation2016, Citation2023). Firstly, the model was evaluated based on the attainment of acceptable fit indices. In absolute fit indices, CMIN = 450.56. df = 197, x2/df = 2.28, RMR = 0.040, GFI = 0.908 and RMSEA = 0.070 whilst incremental fit indices were; CFI = 0.947, TLI = 0.938, IFI = 0.947 and NFI = 0.910. Based on Kline (Citation2016), the structural model obtained a good fit. illustrates the structural model.

Secondly, the path estimates, t-statistics and p-value were used to determine relationships that were statistically significant (Byrne, Citation2013; Kline, Citation2023). At 95% confidence interval, t-values greater than 1.96 were adjudged statistically significant from zero (Kline, Citation2023). Hypothesis H1a, H1b and H1c proposed that perceived economic CSR, perceived social CSR and perceived Environmental CSR positively affect corporate brand credibility, respectively. In H1a, β = .281, t = 4.014 and p = 0.000, whilst in H1b, β = .251, t = 4.183, p = 0.002 and in H1c, β = .227, t = 3.783, p = 0.001. The results confirm that economic CSR (fair pricing, equitable employee compensation, and high quality products), social CSR (social welfare, infrastructural support and philanthropy) and environmental CSR (environmental conservation, infrastructural development, green operations, sustainable waste disposal) have a significant effect on consumers’ perceptions of corporate brand credibility in the telecommunications sector in Zimbabwe. Given these results, hypotheses H1a, H1b and H1c gained empirical support.

Further, hypotheses H2a, H2b and H2c predicted that that perceived economic CSR, perceived social CSR and perceived Environmental CSR positively influence consumer brand attitude. Results from SEM indicated that two of these causal paths were statistically significant. These were H2a (β = .303, t = 3.228, p = 0.001) and H2b (β = .242, t = 3.723, p < 0.001). In H2c, the relationship was not statistically significant (β = -.108, t = -.767, p = 0.116). Consequently, H2a and H2b were supported whilst H2c was rejected. The findings suggest that consumers’ perceptions of environmental CSR activities (environmental conservation, greener processes, green waste disposal, lean production) does not translate into positive brand attitudes for their products. In contrast, perceived economic CSR (fair pricing, equitable employee compensation, and high quality products) and perceived social CSR (social welfare, infrastructural support and philanthropy) were positively influential on consumer brand attitudes.

Further, the study hypothesized that corporate brand credibility has a positive effect on consumer brand attitude in H3. The results indicate that this relationship was confirmed (β = .248, t = 2.987, p = 0.003). This supports that when consumers associate a corporate brand with of goodwill, integrity, respect and trust through CSR projects, the firm earns corporate brand credibility and this stimulates development of positive consumer brand attitudes towards its products and services. Corporate brand credibility strongly influenced consumer brand attitudes in the telecommunications product and service markets. As a result, H3 was supported.

In H4, the positive influence of corporate brand credibility on consumer brand preference was modelled. The results confirmed a positive causal effect. This was evidenced by a standardized estimate (β) of .171, a t-statistic of 2.525 and a p = 0.012. Given these results, H4 was accepted. The findings confirm that positive consumer perceptions of a corporate brand have a positive effect on consumer brand preference when they make actual purchasing choices, thus corporate credibility arising from CSR support acts as a strong pre-cursor to consumer brand preferences in the telecommunications sector in Zimbabwe.

H5 predicted that consumer brand attitude has a positive impact on consumer brand preference. The relationship was strong, positive and statistically significant, thus, this hypothesis was also confirmed (β = .511, t = 7.170, p < 0.001). The results provide evidence to support that as consumers build a positive attitude towards a firms’ brands, the higher is their propensity to purchase it amongst competing products. These finding strongly support that CSR-based consumer brand attitude positively and significantly influences consumers’ brand preferences in a Zimbabwean context. shows the outcomes of hypothesis testing.

Table 4. Results of hypothesis testing.

4.4. Discussion of findings

The influence of perceived CSR dimensions on corporate brand credibility was confirmed. In the first instance, the relationship between perceived economic CSR and corporate brand credibility was positive and significant (β =.281, t = 4.014). This resulted in support for Hypothesis H1a. The findings substantiate that fair business practices, reasonable prices, equitable employee rewards, high quality products (economic CSR) have a positive impact on the corporate image and reputation of the firm. This could be explained by the close link between Zimbabwean consumers and the manner in which they interact with the firm on other exchange relationships outside the telecommunications commercial context. In related studies, Vera-Martínez et al. (Citation2022) reported the positive effect of economic CSR on firm credibility whilst Mapokotera et al. (Citation2023) noted its positive effect on corporate social competitiveness. Economic CSR had the strongest causal effect on corporate brand credibility relative to social and environmental CSR. Thus, current findings add to literature the positive impact of economic CSR on corporate brand credibility.

The relationship between social CSR and corporate brand credibility was also positive and statistically significant (β = .251, t = 4.183) and H1b was accepted. In the telecommunications sector in Zimbabwe, the study finds that community support, education funding, health donations, social welfare programs and infrastructural investment (social CSR) earns the firm corporate brand credibility endowed in its reputation and image. Vera-Martínez et al. (Citation2022) confirmed that social CSR positively influenced firm credibility. In a related study, Mapokotera et al. (Citation2023) also confirmed that social CSR leads to corporate social competitiveness. Further, the study of Mohammed and Rashid (Citation2018) confirmed that philanthropic acts towards humanitarian causes, health, education, and participation in community building programs brings a sense of identification and loyalty among customers. In the current study, we find that in developing economies like Zimbabwe, consumers have lower disposable incomes hence they strongly relate to corporate philanthropic behavior as firms remedy topical societal challenges. Perceived social CSR had the second strongest effect on consumer brand credibility based on the estimated parameters and t-values.

Further, the study also confirmed the positive effect of perceived environmental CSR on corporate brand credibility (β = .227, t = 3.783) and we confirmed hypothesis H1c. In a Zimbabwean context, the study demonstrates that firms that invest in cleaner production processes, sustainable waste disposal practices, revitalize dilapidated worksites (environmental CSR) earns the firm consumer trust and perception of good corporate citizenship, hence corporate brand credibility. Although the environmental sensitivity is relatively lower in developing economies (Muposhi et al., Citation2015), current findings show that the collective community benefits through firm’s environmental CSR investment have a high propensity to earn the firm goodwill, image and reputation. These findings contrast with Vera-Martínez et al. (Citation2022), who found the relationship to be insignificant. However, Manuere et al. (Citation2022) found environmental CSR to significantly affect consumer behavior. Further, the findings of Mapokotera et al. (Citation2023) also demonstrate that environmental CSR stimulates corporate social competitiveness. Khojastehpour and Johns (Citation2010) found that environmental CSR influences corporate brand image. However, in this study, perceived CSR had the least strength on corporate brand credibility. Overall, the three CSR dimensions explained 48.7% variance on corporate brand credibility.

The study also proposed causal effects on the three CSR dimensions on consumer brand attitude in H2a, H2b and H2c. The relationship between perceived economic CSR and consumer brand attitude was positive and significant (β = .303, t = 3.228). In the telecommunications sector in Zimbabwe, we observe that consumers are more sensitive to the manner in which the firm conducts in business with all stakeholders in parameters such as fair pricing models, employee welfare, service or product quality and tax attitudes. Manuere et al. (Citation2022) and Shoko et al. (Citation2021) found that economic CSR positively affects consumer response to product brands. Mohammed and Rashid (Citation2018) and Vera-Martínez et al. (Citation2022) also examined its impact on brand identification and product brand image, respectively. We also observe that positive economic properties of the relationship between the firm and the consumer were important on the subjective stimulation of brand responses elicited by consumers. However, these results are interesting given that Zimbabwe has the highest data services in the world, which probably suggest that future research should further refine economic CSR to avoid overlapping effects.

Hypothesis H2b, which proposed positive causality between perceived social CSR and consumer brand attitude was accepted (β = .242, t = 3.723). This study also shows that in developing ecconomies like Zimbabwe, social CSR (community support, social welfare programs and infrastructural investment) stimulates positive consumer attitudes towards the firms’ brands. This research realises that the society comprises of the ‘collective consumer’ hence corporate good deeds directed to the ‘people’ are reciprocated by the ‘consumer’ in form of brand affiliation, purchase intent and actual purchase. Given the scale of social CSR in the telecommunications sector especially amid COVID-19, consumers are expected to positively relate to the firms’ offerings. The study notes that Vera-Martínez et al. (Citation2022) reported a positive effect of social CSR on brand identification in a related study. Further, our findings are aligned to Mohammed and Rashid (Citation2018) who claimed that social CSR conveys a sense of identification, inclusion and loyalty among consumers. In terms of relative impact, social CSR was second on the effect on consumer brand attitude.

H2c was rejected as the impact of perceived environmental CSR on consumer brand attitude was not positively significant (β = -.108, t = -.767). Against our expectations, we find that investing in environmental conservation, cleaner production processes, green waste disposal, reclamation of dilapidated worksites (environmental CSR) did not positively influence consumers’ brand attitudes towards product brands in Zimbabwean telecommunications sector. This could connote that consumers from low-income and developing economies like Zimbabwe could be more sensitive to ‘human CSR’ that directly impact their livelihoods (economic and social CSR) than the wider ‘ecological’ good. Further, green consumerism and environmentalism have relatively received slower attention in developing countries. Although no theoretical arguments have been raised yet to support this behavioral paradox, Currás-Pérez et al. (Citation2018) and Vera-Martínez et al. (Citation2022) also noted that that not all consumers value environmental sustainability in their studies.

H3 was also supported, thus corporate brand credibility positively influenced consumer brand attitudes (β = .248, t = 2.987). The findings support that CSR initiatives earn corporate brand reputation/image among consumers and this in turn leads to positive consumer brand attitudes. Extant literature supports that consumers form brand associations with corporates who exhibit socially responsible corporate behavior (Agrawal & Gupta, Citation2018; Hsu et al., Citation2022; Puriwat & Tripopsakul, Citation2021). Therefore, the findings are not a new phenomenon in CSR studies. Consumers’ brand affiliations towards firms that actively support the sustainability thrust has been observed in previous studies e.g. Aydin (Citation2019), Ramesh et al. (Citation2018) and Schnittka et al. (Citation2022). However, key to note is the empirical validation of the link between CSR-based corporate brand credibility that transcends into positive consumer brands attitudes in consumer markets. This study clearly delineates an over-generalised nexus in previous research studies. Overall, corporate brand credibility plus the three CSR dimensions had 38.2% variance in consumer brand attitudes (R Squared = .382).

Further, H4 was also accepted and the effect of corporate brand credibility on consumer brand preference was confirmed (β = .171, t = 2.525). The findings imply that CSR drives good corporate image, public perception and sympathy, goodwill and corporate reputation. Thus, this results in feelings of closeness, trust and commitment towards a company’s brands (Adewole, Citation2023; Hsu et al., Citation2022). These results connote that the relationship is strengthened by the consumers’ desire to repay the faith to corporate brands through positive brand association that translates into purchase behaviors. The findings closely relate to those reported in studies of Asmussen and Fosfuri (Citation2019), Cheung et al. (Citation2019), Vera-Martínez et al. (Citation2022).

H5 had proposed the positive effect of consumer brand attitude on consumer brand preference. This proposed effect presented a behavioral argument against prior studies that omitted the role of attitude formation in the link between CSR and consumer brand preference or purchase disposition. Extant behavioral literature strongly support that individual attitude play a key precedent role on brand behaviors (Ajzen, Citation2020; Dangaiso, Citation2023; Dilotsotlhe & Akbari, Citation2021). Interestingly, this relationship was confirmed (β = .511, t = 7.170) and the evidence suggests that a positive attitude towards a CSR dominant brand translates into brand favor, likeness and preference when making purchases. The tri-component model of attitude formation (Rosenberg & Hanland, Citation1960) suggests that consumers develop brand beliefs (cognitive) and brand feelings (affective) that culminate into brand behaviors (conative). In the Zimbabwean context, we confirmed that consumer concerns for socially responsible brands stimulate the development of cognitive beliefs, brand feelings and behaviors towards brands that support communities through CSR. The findings concur with Jeon et al. (Citation2020) and Puriwat and Tripopsakul (Citation2021).

Overall, the validated model explained 62.9% of the variability in consumer brand preference in the telecommunications sector in Zimbabwe. The current research builds and evaluates a more comprehensive composite model that integrates fragmented constructs that have been examined in literature as discrete variables in simplistic linear relationships. The study attempts to specify a model that resembles key CSR dimensions and their relationships with corporate brands (corporate brand credibility through image and reputation) and market-based outcomes (consumer brand attitude and consumer brand preference). We also emphasize the role of brand attitude as the key linkage between CSR and consumer brand preference. Lastly, the study notes the underwhelming customer environmental sustainability awareness in pre-merging markets, an important impetus for advanced sustainability marketing in most developing markets.

5. Conclusions and implications

5.1. Conclusions

The main objective of this research was to propose and validate a CSR-based consumer brand preference model that connects CSR dimensions to corporate brand credibility, consumer brand attitude and consumer brand preference in the telecommunications sector. The paper concludes that perceived economic CSR and perceived social CSR are strong predictors of CSR-based corporate brand credibility and consumer brand attitude, which in turn strongly determines consumer brand preference. Although perceived environmental CSR positively and significantly influenced corporate brand credibility, this study concludes that perceived environmental CSR does not influence brand attitudes in consumer markets. The study concludes that the link between CSR and consumer brand dispositions largely vary by context hence more research is still imperative. Current findings suggest that this depends on the underlying consumer orientation towards the specific CSR dimensions in their economic context.

Current study shows that consumers in pre-emerging markets have a lower orientation and understanding of green brands and environmental sustainability relative to prior research in more advanced economies. Arguably, due to lower income and lower quality of life, consumers in developing markets’ brand dispositions were found to be more aligned to ‘human CSR’ (economic and social CSR benefits) than environmental concerns. The study therefore observes the underwhelming consumer environmental orientation in developing markets as consumers’ perceived environmental CSR did not relate with consumer brand attitude. In developed countries, more demanding and complex consumer profiles have mainstreamed green adoption, environmental sensitivity and corporate awareness in diverse market settings. Lastly, the research underlines a key consideration for behavioral researchers in the CSR context that consumer brand attitude occupies a key role in the linkage between CSR and consumer brand behaviors.

5.2. Theoretical implications

This research aimed to advance literature in the area of CSR, consumer behavior and brand management; hence, a CSR-based consumer brand preference model was proposed and tested. The study advances literature that confirm the power of corporate self-regulation endowed in CSR initiatives through expediting consumer brand acceptance and preference. Further, this research is one of the scarce studies to operationalize CSR and consumer brand preference using the sustain-centric paradigm, thus it validates the framework in the context of a pre-emerging economy. More so, the study is the first to operationalize and validate a model connecting economic CSR, social CSR and environmental CSR, corporate brand credibility, consumer brand attitude and consumer brand preference. This model may be re-examined in other contexts to evaluate its applicability to diverse CSR phenomenona. Secondly, the study disconfirms the positive effect of environmental CSR on consumer brand attitude in the context of the telecommunications sector from a developing country, supporting to earlier research by Bravo et al. (Citation2012), Currás-Pérez et al. (Citation2018), Peloza and Shang (Citation2011) and Vera-Martínez et al.(Citation2022).

Further, the model explained 62.9% of the variability in CSR-based consumer brand preference, thus, it validates the model in a relatively under-researched subject in a low-income economy. Further, CSR research is scarce in developing economies due the fewer number of corporates that have been keen and capable of investing in CSR in the past. Although the research framework was integrated from a previously examined model (sustain-centric model) and branding constructs, it provides a baseline on which future CSR and consumer brand preference research in developing economies can be conceptualized and operationalized. Although CSR research has recently advanced, this study integrates loosely tested constructs in a more comprehensive framework that was validated using an advanced statistical methodology. Although the CSR concept has had diverse and emergent dimensions, the sustain-centric approach validates CSR on key pillars that serve as fundamental thrust for inclusive and sustainable social responsibility.

5.3. Practical implications

Traditionally, firms are obliged to comply with legal frameworks imposed by governments and industry regulators. Meanwhile, Zimbabwe does not have a legal framework on operationalization of CSR and firms invest in CSR out of organizational self-consciousness. This research enlightens corporate managers on the attractiveness of corporate self-regulation through CSR that engenders community development, poverty alleviation, infrastructural development, fair business practices, sustainable production methods, quality control, sustainable consumption behavior, better waste management practices and community empowerment through internally managed initiatives. Current findings educate corporate managers in developing economies on the nexus between CSR and market-based assets that accrue to the firm. The study demonstrates to corporate managers the positive gains of CSR, in terms of consumer brand preference, an under-researched subject area especially in developing markets where CSR was initially received with corporate skepticism.

Secondly, the research also debunks the misconception that CSR is a way one beneficiation strategy meant to reduce profit margins on corporates. This model illustrates the investments and returns from CSR, thus it provides a key impetus for firms to employ CSR as a differentiation strategy for generating consumer brand preference. Further, given that the corporates consider many CSR initiatives and that CSR is a multi-dimensional construct, this paper enlightens the relative importance of economic, social and environmental CSR, thus the research provides an empirical springboard for resource allocation based on these validated CSR measurements. Ranking in ascending order, this study shows the relative impact of economic CSR, social CSR and environmental CSR, respectively. However, more implications are situated on the empirical outcome of a low-ranking environmental CSR perception, a key area that environmentalists may need to work on in pre-emerging economies so that environmentally sensitive firms gain positive consumer market attitudes. Given the widely experienced global adverse climate effects, corporate managers and environmental activists need to conscientise all stakeholders, particularly end-users on the role of environmental sustainability on global bio-physical longevity.

5.4. Limitations and future research directions

Although the main objective of the study was accomplished, this research was also subject to some inherent limitations. The first limitation arises from the multi-dimensionality of CSR, this research focused on constructs from the sustain-centric model. However, emergent literature suggests that operationalization of CSR has been too subjective and dimensions such as ethics CSR, political CSR, cultural CSR and legal CSR have emerged (Puriwat & Tripopsakul, Citation2021). Future studies may extend the framework with constructs excluded from this study to enhance its explanatory power.

Secondly, a methodological limitation on the convenience sampling method that was employed in this study. Probability sampling methods better resemble the distribution of population parameters hence recommended. However, the technique was employed based on the non-availability of sampling frames and consideration of other contextual factors. However, to enhance generalizability and comparability with studies related, probabilistic sampling methods may be employed by future researchers.

Lastly, although the sample size employed sufficed to reach statistical tests and conclusions, a bigger and more representative sample from all provinces in Zimbabwe would have been more generalizable. However, due to resource limitations, accessibility and subject context, the Harare Metropolitan province was selected. Future researchers may use bigger samples to produce more precise findings.

Authors’ contributions

Conception and design: PD; Collection, analysis and interpretation of the data: PD and PM; Drafting of the paper: PD and PM; Critical revision for intellectual content: PM, FM and DCJ; Final approval of the version to be published: PD, PM, DCJ and FM. All authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All listed authors meet the criteria for authorship as per the ICMJE guidelines (PD: Phillip Dangaiso; PM: Paul Mukucha; DCJ: Divaries Cosmas Jaravaza; FM: Forbes Makudza).

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank all the participants who took part in this research. We also thank the editors and anonymous reviewers for their invaluable contributions towards improving our work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Phillip Dangaiso

Phillip Dangaiso is a lecturer and enthusiastic academic researcher at Chinhoyi University of Technology, Zimbabwe.

Paul Mukucha

Paul Mukucha (PhD) is a senior lecturer, Head of Marketing and distinguished researcher at Bindura University of Science Education, Zimbabwe.

Divaries Cosmas Jaravaza

Divaries C Jaravaza (PhD) is also a senior lecturer and seasoned researcher at Bindura University of Science Education.

Forbes Makudza

Forbes Makudza is a senior lecturer and experienced researcher at the University of Zimbabwe, Zimbabwe. Group research interests include business management, corporate governance, services marketing, consumer behaviour, green marketing, social marketing and brand management.

References

- Adewole, O. (2023). CSR – brand relationship, brand positioning, and investment risks driven towards climate change mitigation and next perspectives emerging from: Litigation, projections, pathway and models. SN Business & Economics, 3(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43546-022-00374-4

- Agrawal, R., & Gupta, S. (2018). Consuming responsibly: Exploring environmentally responsible consumption behaviors. Journal of Global Marketing, 31(4), 231–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/08911762.2017.1415402

- Ajzen, I. (2020). The theory of planned behavior: Frequently asked questions. Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies, 2(4), 314–324. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.195

- Aksak, E. O., Ferguson, M. A., & Atakan Duman, S. (2016). Corporate social responsibility and CSR fit as predictors of corporate reputation: A global perspective. Public Relations Review, 42(1), 79–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2015.11.004

- Alvarado-Herrera, A., Bigne, E., Aldas-Manzano, J., & Curras-Perez, R. (2017). A scale for measuring consumer perceptions of corporate social responsibility following the sustainable development paradigm. Journal of Business Ethics, 140(2), 243–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2654-9

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbin, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modelling in practise: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- Arachchi, D. M., & Samarasinghe, D. (2023). Influence of corporate social responsibility and brand attitude on purchase intention. Spanish Journal of Marketing – ESIC, 27. (3), 389–406. https://doi.org/10.1108/SJME-12-2021-0224

- Armstrong, G., & Kotler, P. (2008). Principles of marketing (12th ed.). Pearson Educational Inc.

- Asmussen, C. G., & Fosfuri, A. (2019). Orchestrating corporate social responsibility in the multinational enterprise. Strategic Management Journal, 40(6), 894–916. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.3007

- Aydin, H. (2019). Consumer perceptions and responsiveness toward CSR activities: A sectoral outlook. Ethics, Social Responsibility and Sustainability in Marketing, 12(1), 45–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-7924-6_3

- Benjarongrat, P., & Neal, M. (2017). Exploring the service profit chain in a Thai bank. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 29(2), 432–452. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-03-2016-0061

- Bianchi, E., Bruno, J. M., & Sarabia-Sanchez, F. J. (2019). The impact of perceived CSR on corporate reputation and purchase intention. European Journal of Management and Business Economics, 28(3), 206–221. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJMBE-12-2017-0068

- Bravo, R., Matute, J., & Pina, J. M. (2012). Corporate social responsibility as a vehicle to reveal the corporate identity: A study focused on the websites of Spanish financial entities. Journal of Business Ethics, 107(2), 129–146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-1027-2

- Byrne, B. M. (2013). Structural equation modelling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications and programming. Routledge Taylor and Francis.

- Chepchirchir, J., & Leting, M. (2015). Effects of brand quality, brand prestige on brand purchase intention of mobile phone brands: Empirical assessment from Kenya. The International Journal of Management Science and Business Administration, 1(11), 7–14. https://doi.org/10.18775/ijmsba.1849-5664-5419.2014.111.1001

- Cheung, M. L., Pires, G., & Rosenberger, P. (2019). Developing a conceptual model for examining social media marketing effects on brand awareness and brand image. International Journal of Economics and Business Research, 17(3), 243. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJEBR.2019.098874

- Collier, J. E. (2020). Applied structural equation modeling using AMOS: Basic to advanced techniques (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003018414

- Currás-Pérez, R., Dolz-Dolz, C., Miquel-Romero, M. J., & Sánchez-García, I. (2018). How social, environmental, and economic CSR affects consumer-perceived value: Does perceived consumer effectiveness make a difference? Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 25(5), 733–747. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1490

- Dangaiso, P. (2023). Extending the theory of planned behavior to predict organic food adoption behavior and perceived consumer longevity in subsistence markets: A post-peak COVID-19 perspective. Cogent Psychology, 10(1), 2258677. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2023.2258677

- Davari, A., & Strutton, D. (2014). Marketing mix strategies for closing the gap between green consumers ‘ pro-environmental beliefs and behaviors. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 22(7), 563–586. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2014.914059

- Dilotsotlhe, N., & Akbari, M. (2021). Factors influencing the green purchase behaviour of millennials : An emerging country perspective. Cogent Business & Management, 8(1), 1908745. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2021.1908745

- Elkington, J. (2018). 25 years ago i coined the phrase “tripple bottom line.” Here’s why its time to rethink it. Havard Business Review, 11(1), 35–54.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3150980

- Fundira, T., & Mupfungidza, M. (2022). The influence of corporate social responsibility on brand loyalty in the telecommunications sector during the COVID-19 pandemic: A case of Econet Wireless Zimbabwe. Sachetas, 1(2), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.55955/120001

- Ha, M. (2021). Optimizing green brand equity : The integrated branding and behavioral perspectives. SAGE Open, 11(3), 215824402110360. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440211036087

- Hair, J. F., Page, M., & Brunsveld, N. (2020). Essentials of business research methods (4th ed.). Routledge.

- Hsu, Y., Hong, T., & Bui, G. (2022). Consumers’ perspectives and behaviors towards corporate social responsibility—A cross-cultural study. Sustainability, 14(2), 615. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14020615

- Jeon, M. M., Lee, S., & Jeong, M. (2020). Perceived corporate social responsibility and customers’ behaviors in the ridesharing service industry. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 84, 102341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.102341

- Johnstone, M.-L., & Tan, L. P. (2015). Exploring the gap between consumers’ green rhetoric and purchasing behaviour exploring the gap between consumer and purchasing behaviour. Journal of Business Ethics, 132(2), 311–328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2316-3

- Khojastehpour, M., & Johns, R. (2010). The effect of environmental CSR issues on corporate/brand reputation and corporate profitability. European Business Review, 26(4), 330–339. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-03-2014-0029

- Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modelling (3rd ed.). Guilford Publication.

- Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modelling (5th ed.). The Guilford Press.

- Lai, C., Chiu, C., Yang, C., & Pai, D. (2010). The effects of corporate social responsibility on brand performance : The mediating effect of industrial brand equity and corporate reputation. Journal of Business Ethics, 95(3), 457–469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0433-1

- Liu, M. T., Wong, I. A., Shi, G., Chu, R., & Brock, J. (2014). The impact of corporate social responsibility (CSR) performance and perceived brand quality on customer-based brand preference. Journal of Services Marketing, 28(3), 181–194. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-09-2012-0171

- Lysons, K., & Farrington, B. (2020). Procurement and supply chain management (10th ed.). Pearson Education Ltd.

- Mahmood, A., & Bashir, J. (2020). How does corporate social responsibility transform brand reputation into brand equity ? Economic and noneconomic perspectives of CSR. International Journal of Engineering Business Management, 12, 184797902092754. https://doi.org/10.1177/1847979020927547

- Makudza, F., Mugarisanwa, C., & Siziba, S. (2020). The effect of social media on consumer purchase behaviour in the mobile telephony industry in Zimbabwe. Dutch Journal of Finance and Management, 4(2), em0065. https://doi.org/10.29333/djfm/9299

- Manuere, F., Viriri, M., & Chufama, M. (2022). The effect of corporate social responsibility programmes on consumer buying behavior in the telecommunication industry in Zimbabwe. International Journal of Research in Commerce and Management Studies, 3(2), 24-37. https://ijrcms.com

- Mapokotera, C., Mataruka, L. T., Muzurura, J., & Mkumbuzi, W. P. (2023). The Nexus between corporate social responsibility and corporate social performance in the service-based enterprises Sector: Insights from Zimbabwe. Qeios, 15(2), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.32388/UT5RBU.2

- Mendleson, N., & Polonsky, M. J. (1995). Using strategic alliances to develop credible green marketing. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 12(2), 4–18. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363769510084867

- Mody, M., Day, J., Sydnor, S., Lehto, X., & Jaffé, W. (2017). Integrating country and brand images: Using the product-country image framework to understand travelers’ loyalty towards responsible tourism operators. Tourism Manage Perspect, 24, 139–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2017.08.001

- Mohammed, A., & Rashid, B. (2018). Kasetsart journal of social sciences a conceptual model of corporate social responsibility dimensions, brand image, and customer satisfaction in Malaysian hotel industry. Kasetsart Journal of Social Sciences, 39(2), 358–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kjss.2018.04.001

- Mukucha, P., Jaravaza, D. C., & Nyengerai, S. (2023). Circular economy of shopping bags in emerging markets: A demographic comparative analysis of propensity to reuse plastic bags versus cotton bags and paper bags. Cogent Engineering (OAEN), 10(1), 2176582. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311916.2023.2176582

- Muposhi, A., Dhurup, M., & Surujlal, J. (2015). The green dilemma: Reflections of a Generation Y consumer cohort on green purchase behaviour. The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa, 11(4), 31–40. https://doi.org/10.4102/td.v11i3.64

- Niskala, M., & Tarna, K. (2003). Yhteiskuntavastuuraportointi (social responsibility reporting). KHT Media Gummerus Oy.

- Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory. McGraw-Hill.

- Panwar, R., Rinne, T., Hansen, E. Y., & Juslin, H. (2006). Corporate responsibility: Balancing economic, environ- mental, and social issues in the forest products industry. Forest Products Journal, 56(2), 4–12.

- Peattie, K. (2010). Green consumption: Behaviour and norms. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 35(1), 195–228. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-032609-094328

- Peloza, J., & Shang, J. (2011). How can corporate social responsibility activities create value for stakeholders? A systematic review. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(1), 117–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-010-0213-6

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioural research: A critical review of literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- POTRAZ. (2023). Postal and Telecommunications Regulatory Authority of Abridged Postal and Telecommunications.

- Powell, W. W., & Di Maggio, P. J. (1991). The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. University of Chicago Press.

- Puriwat, W., & Tripopsakul, S. (2021). The impact of digital social responsibility on preference and purchase intentions : The implication for open innovation. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 7(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7010024

- Ramesh, K., Saha, R., Goswami, S., Sekar & Dahiya, R. (2018). Consumers response to CSR activities: Mediating role of brand image and brand attitude. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 26(2), 377–387. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1689

- Rosenberg, M. J., & Hanland, J. C. (1960). Low-commitment consumer behavior. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 2(11), 367–372.

- Saeidi, S. P., Sofian, S., Saeidi, P., Saeidi, S. P., & Saaeidi, S. A. (2015). How does corporate social responsibility contribute to firm financial performance? The mediating role of competitive advantage, reputation, and customer satisfaction. Journal of Business Research, 68(2), 341–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbus-res.2014.06.024

- Saunders, M. N. K., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2018). Research methods for business students (8th ed.). Pearson.

- Schiffman, L. G., & Kanuk, L. L. (2004). Consumer behavior (8th ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall.