Abstract

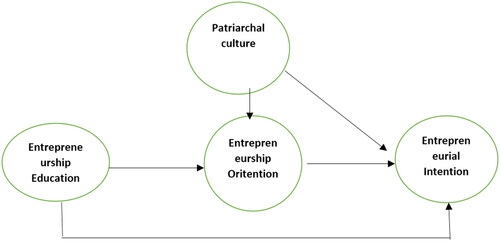

This study explores the impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial orientation and intention among Indonesian students, while considering the influence of patriarchal culture. A quantitative research design using online surveys was employed, with 248 respondents who completed the entrepreneurship course in the even semester of 2022 at the Faculty of Economics, Universitas Negeri Medan. The surveys were administered online by the researchers. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) was utilized for analyzing the variables, and Mann–Whitney tests assessed gender and educational background differences. Results reveal a positive and significant effect of entrepreneurship education on both entrepreneurial orientation and intention. Entrepreneurial orientation significantly influences entrepreneurial intention. Surprisingly, patriarchal culture does not negatively impact entrepreneurial orientation or intention; its effect differs from expectations. No significant differences were found between genders or educational backgrounds regarding the impact of entrepreneurship education, orientation and intention. Specifically, no significant differences were found in the impact of entrepreneurship education, orientation and intention between genders or educational backgrounds. Also, entrepreneurial orientation partially mediates the relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intention.

1. Introduction

Gender disparities persist, as evidenced by Indonesia’s ranking of 87th out of 146 countries in the 2023 Global Gender Gap Report, scoring 0.697 (Global Gender Gap Report 2023, Citation2023). This ranking illuminates pervasive gender inequalities across sectors like the economy, education, health and politics within Indonesia. Additionally, Indonesia’s placement at 75th among 137 countries in the 2019 Global Entrepreneurship Index, with a score of 0.26, underscores ongoing challenges (Global Entrepreneurship and Development Index, Citation2019). Despite these indices, the specific causes of gender gaps in Indonesia’s economic landscape remain elusive. Could these disparities be linked to Indonesia’s prevailing patriarchal culture? Patriarchal norms, which valorize men over women (Mies, Citation2014), foster asymmetric gender relationships, often positioning men in dominant roles while relegating women to subordinate positions (Omara, Citation2004). These cultural norms traditionally designate men as breadwinners and women as homemakers, potentially influencing entrepreneurial dynamics. Prior research by Davis and Shaver (Citation2012) has suggested that women exhibit less inclination toward entrepreneurship compared to men.

According to Linan et al. (Citation2005), the level of entrepreneurial intention plays a crucial role in business creation. However, empirical evidence suggests a disparity in entrepreneurial intention between men and women (Pillis & Dewitt, Citation2008; Plant & Ren, Citation2010). Studies indicate that men tend to exhibit higher levels of entrepreneurial intention compared to women (Egel, Citation2021; Haus et al., Citation2013; Hutasuhut, Citation2018). One significant barrier for women in increasing their entrepreneurial intention is the perceived risk of failure when starting a business (Camelo-Ordaz et al., Citation2016).

Furthermore, scholars indicate that entrepreneurial intention, a key precursor to business creation (Linan et al., Citation2005), also exhibits gender disparities (Pillis & Dewitt, Citation2008; Plant & Ren, Citation2010). Men tend to demonstrate higher levels of entrepreneurial intention than women (Egel, Citation2021; Haus et al., Citation2013; Hutasuhut, Citation2018), with fear of failure often cited as a significant barrier for women (Camelo-Ordaz et al., Citation2016).

Entrepreneurship education emerges as a potential remedy, equipping individuals with the mindset, skills and experience necessary for venture initiation (Neck & Corbett, Citation2018; Roxas, Citation2014). This situation, backed up by studies across various countries, suggests a positive impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intentions (Küttim et al., Citation2014; Taye, Citation2019). The study conducted in Vietnam by Duong (Citation2022) revealed that entrepreneurship education impacts entrepreneurial intention through the mediation of attitude toward entrepreneurship and perceived behavioral control. The need for mediating variables in efforts to enhance entrepreneurial intention through entrepreneurship education is also confirmed by Hoang et al. (Citation2020). Also conducted in Vietnam, entrepreneurship education positively affects entrepreneurial intentions, and this relationship is mediated by both learning orientation and self-efficacy. Hassan et al. (Citation2021) investigated the direct and indirect influences of personal entrepreneurial orientation and entrepreneurship education on students’ entrepreneurial intentions, mediated by entrepreneurial motivation, in the Indian context. Their study revealed that entrepreneurship education fosters both personal entrepreneurial orientation and entrepreneurial motivation and is positively linked with entrepreneurial intention. Furthermore, entrepreneurial motivation serves as a significant mediator in the relationships between individual entrepreneurial orientation and entrepreneurial intention, as well as between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intention. However, their study did not further investigate whether the impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intentions could differ between males and females. There remains a gap in understanding how entrepreneurship education specifically influences the entrepreneurial intentions of both men and women in the context especially in Indonesia.

Another factor influencing individual entrepreneurial intentions is their entrepreneurial orientation. Covin and Wales (Citation2012) define entrepreneurial orientation as a set of characteristics that precede and predict the creation of new products. Kumar et al. (Citation2020) further state that an individual’s entrepreneurial orientation is positively associated with their intention to pursue entrepreneurship. However, differing opinions exist, as Hassan et al. (Citation2021) argue that an individual’s entrepreneurial orientation does not have a direct and significant impact on their intention to become an entrepreneur.

Thus, this study aims to explore the potential influence of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial orientation and intention, with a focus on both male and female students from higher education, this is because this sample group has received entrepreneurship education in higher education and is in an age group that is capable of starting their own businesses. Additionally, it aims to examine the potential negative impact of patriarchal culture on women’s entrepreneurship. By investigating whether entrepreneurial orientation mediates the relationship between entrepreneurship education and intention, this research seeks to illuminate the intricate dynamics shaping entrepreneurial pursuits. Through this inquiry, we endeavor to contribute to a deeper understanding of the intersection between cultural norms (patriarchal culture), entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurship orientation and intention notably within an Indonesian sample where gender disparities persist.

2. Literature review

2.1. Entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurship orientation and entrepreneurship intentions

Entrepreneurship is characterized by intentional and planned behavior (Krueger et al., Citation2000). In the past few decades, entrepreneurship has emerged as a significant economic force globally (Raposo & Do Paço, Citation2011). While there have been extensive studies on the factors influencing entrepreneurial intention, most of them have focused on established entrepreneurs and businesses, neglecting potential entrepreneurs such as students (Grine et al., Citation2015). However, students represent a crucial resource for future entrepreneurs and often consider entrepreneurship as their primary career choice after graduation (Gallant et al., Citation2010).

Entrepreneurship education is grounded in various theoretical frameworks, including the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991) and Social Cognitive Theory (Bandura, Citation1986), which emphasize the role of attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control and observational learning in shaping entrepreneurial intentions and behaviors. These theories provide a foundation for understanding how entrepreneurship education influences individuals’ perception, attitudes and behaviors toward entrepreneurship. Extensive empirical research has explored the effects of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intentions and orientations. Studies by Ashmore (Citation2006) asserts that entrepreneurship education provides knowledge pertaining to the ability to recognize opportunities, generate new ideas, acquire necessary resources and effectively manage and operate a new business. Similarly, Raposo and Do Paço (Citation2011) concluded that entrepreneurship education aims to impart knowledge about entrepreneurship, foster the ability to identify and address business situations, develop and enhance skills, cultivate empathy and support for entrepreneurship-related issues, adapt to changes and encourage the establishment of startups and new ventures. Nuseir et al. (Citation2020) further add that the primary objectives of entrepreneurship education are: (1) cultivating an entrepreneurial culture among students, (2) instilling an entrepreneurial behavior and mindset and (3) educating students on initiating and managing independent businesses. Likewise, Arasti et al. (Citation2012) argue that entrepreneurship education aims to raise awareness about entrepreneurship as a viable career choice and enhance understanding of the process involved in establishing and managing new businesses. Entrepreneurship education aims to increase students’ awareness of entrepreneurship, develop their skills, provide opportunities to apply theoretical knowledge and foster consideration of entrepreneurship as a career choice (Bae et al., Citation2014; Fayolle & Gailly, Citation2015). It is crucial because it equips entrepreneurs with the knowledge, abilities and skills they need (Ruizalba Robledo et al., Citation2015).

Educational institutions have recognized entrepreneurship education as an effective means of nurturing students’ entrepreneurial intentions (Liñán, Citation2004). Also, entrepreneurship education plays a pivotal role in shaping entrepreneurial attitudes (Potter, Citation2008) and significantly enhancing entrepreneurship knowledge, which is essential for developing students’ confidence and willingness to engage in entrepreneurship (Roxas, Citation2014). Various countries have introduced entrepreneurship education models, which encompass entrepreneurship courses, internships, or the integration of entrepreneurship as a field of study in universities offering relevant courses. Entrepreneurship education can be delivered through both formal and informal channels. Formal education encompasses secondary schools to higher education institutions, with some even introducing entrepreneurship education at the primary level. Informal education occurs through community-based training programs and within families.

Moreover, entrepreneurship education has been found to have a positive influence on students’ entrepreneurial orientation in terms of innovation and proactivity, although its impact on risk-taking is not significant (Marques et al., Citation2018). On the other hand, Nshimiyimana (Citation2020) suggests that entrepreneurship education significantly affects the dimensions of innovativeness and competitive aggressiveness, two out of the five dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation (Autonomy, Innovativeness, Risk-taking, Proactiveness and Competitive aggressiveness). Efrata et al. (Citation2021) also conducted research indicating that entrepreneurship education has an impact on individual entrepreneurial orientation. Additionally, Lindberg et al. (Citation2017) and Robinson and Stubberud (Citation2014) demonstrated that entrepreneurship education acts as a mediating variable that strengthens the relationship between individual entrepreneurial orientation and the intention to start a business.

From the theoretical foundations and empirical evidence, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1: Entrepreneurship education positively influences entrepreneurial intention.

H2: Entrepreneurship education positively influences entrepreneurial orientation.

2.2. Entrepreneurial orientation and entrepreneurial intention

Entrepreneurial orientation, a key construct in entrepreneurship research, encompasses a set of strategic orientations guiding individuals or organizations toward entrepreneurial behaviors (Miller, Citation1983). This concept is rooted in the seminal work of Miller (Citation1983) and has since been refined and expanded upon by scholars to include dimensions such as innovation, proactiveness, risk-taking and competitive aggressiveness. Additionally, cultural factors particularly patriarchal norms prevalent in societies like Indonesia, exert significant influence on women’s entrepreneurship (Kelley et al., Citation2017; Yusuf, Citation2013).

Cultural factors, particularly prevalent in patriarchal societies like Indonesia, significantly influence women’s entrepreneurship (Kelley et al., Citation2017; Yusuf, Citation2013). In Indonesia, the enduring presence of a patriarchal culture poses a major challenge for women entrepreneurs. It is crucial to investigate how the patriarchal culture in Indonesia negatively impacts entrepreneurial orientation and impedes women’s entry into entrepreneurship. Existing research indicates a positive relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial orientation as well as entrepreneurial intentions. Additionally, individual entrepreneurial orientation has been found to positively influence entrepreneurial intentions (Ibrahim & Mas’ud, Citation2016; Kumar et al., Citation2020). However, Cho and Lee (Citation2018) argue that entrepreneurship education is not associated with the entrepreneurial orientation of young entrepreneurs, necessitating further investigation within the context of students. Furthermore, the potential mediating role of entrepreneurial orientation between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions requires empirical validation.

Bui et al. (Citation2018) explored female entrepreneurship in patriarchal societies, focusing on motivations and challenges. They found that patriarchal norms impose unique obstacles for women entrepreneurs, affecting their entrepreneurial orientation and intentions. Furthermore, Shastri et al. (Citation2022) conducted research on women entrepreneurs’ motivation and challenges from an institutional perspective in a patriarchal state in India. Their findings highlighted the significant impact of institutional factors, including patriarchal norms, on women’s entrepreneurial behavior. Building on this understanding, Ahmetaj et al. (Citation2023) investigated women entrepreneurship challenges and perspectives in an emerging economy, shedding light on multifaceted barriers faced by women entrepreneurs and underscores the pervasive influence of cultural factors on women’s entrepreneurial endeavors.

Further enriching our understanding, Raimi et al. (Citation2023) conducted a thematic review of motivational factors, types of uncertainty and entrepreneurship strategies among women entrepreneurs, ethnic minorities and immigrants background. Their comprehensive analysis revealed the intricate interplay between cultural factors and entrepreneurial behavior, particularly for marginalized groups. Given the significance of cultural factors, especially in patriarchal societies, it is crucial to examine their impact on entrepreneurial orientation and intentions. The studies by Bamfo et al. (Citation2023), Apostu and Gigauri (Citation2023) and Ozasir Kacar et al. (Citation2023) offer insights into the interplay between cultural factors, entrepreneurship and sustainable development in emerging country like Indonesia.

Thus, four hypotheses are proposes as follows:

H3: Entrepreneurship orientation positively influences entrepreneurial intention.

H4: Patriarchal culture negatively influences entrepreneurial orientation.

H5: Patriarchal culture negatively influences entrepreneurial intentions.

H6: Entrepreneurial orientation mediates the relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions.

3. Method

3.1. Research design and sample

This study utilized a survey research design as its research procedure. Survey research designs are commonly used in quantitative research to gather information about the attitudes, opinions, behaviors, or characteristics of a population by administering a survey to a sample or the entire population (Creswell, Citation2012). Specifically, the type of survey research design employed in this study was a cross-sectional survey design, where data was collected at a single point in time (Creswell, Citation2012).

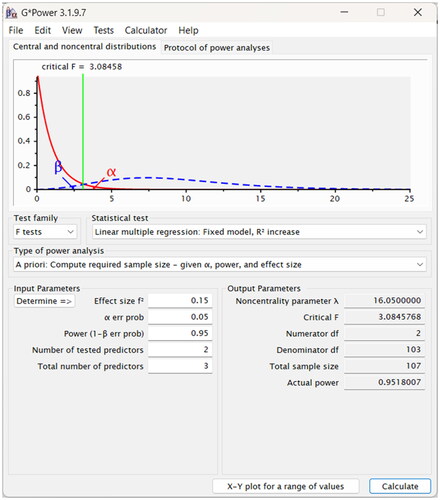

The sample for this study was selected using a convenience sampling procedure. This sampling technique is classified as one type of nonprobability sampling. Nonprobability sampling was chosen because it is not always possible to use probability sampling in educational research (Creswell, Citation2012). In addition, convenience sampling was chosen as a sampling technique because these participating samples were available and because the researchers had permission and could obtain consent from the students to participate in this study. In determining the sample size, the authors followed the recommendations provided by Hair et al. (Citation2016). They utilized G*Power software (Faul et al., Citation2007) to calculate the required sample size and statistical power. The authors set the error measurements for type one and type two errors at α = 0.05 and power (1—β) = 0.95, respectively. We also chose an effect size of 0.15 to achieve a medium effect size, which is considered the minimum threshold (Cohen, Citation2013; Hair et al., Citation2016). With three predictors in the model, two of which were tested predictors, the calculation indicated that a minimum sample size of 107 was required for this study. The complete settings used by the authors to analyze the sample size and the corresponding results can be seen in .

3.2. Instrumentation and data collection

The instruments used in this study for data collection have been validated by previous researchers. The Entrepreneurship Education Questionnaire utilized in this study was developed by Kusmintarti et al. (Citation2016). The indicators for entrepreneurial intention were derived from the work of Liñán and Chen (Citation2009). The questionnaire for entrepreneurial orientation was adopted from Fatima and Bilal (Citation2019). Additionally, the questionnaire for assessing patriarchal culture was developed specifically for this study, because there is no previously developed instrument that measures this variable.

All four variables in the study were measured using a seven-point scale, ranging from 1 (not very appropriate) to 7 (very appropriate). The questionnaire included demographic information such as gender, field of science and ethnicity. Detailed information regarding the variables and their corresponding indicators can be found in .

Table 1. Variables and indicators.

3.3. Sample demographic background

presents the background information of the sample participants in this study, which consisted of a total of 248 individuals. The sample is categorized based on gender, educational background and tribe. Over half of the participants were female (65.32%), with the remaining participants being male (34.68%). Regarding educational background, those from an education major outnumbered those from a non-education major, comprising 65.32% and 34.68%, respectively. This disparity in gender representation is notable due to the prevalence of female students in the education major department in Indonesia. Regarding the tribe, the majority of participants belonged to the Toba tribe (48.79%), followed by the Jawa tribe (20.97%) and the Mandailing tribe (9.68%). The distribution of the remaining participants can be found in .

Table 2. Sample demographic background.

3.4. Data analysis procedure

In this study, the data was analyzed using Partial Least Square Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). While covariance-based structural equation modeling (CB-SEM) has traditionally been the dominant method for analyzing the complex relationships between observed and latent variables, there has been a recent increase in the use of PLS-SEM compared to CB-SEM (Hair et al., Citation2016). Researchers find the PLS-SEM analysis method appealing because it allows for the estimation of complex models with numerous constructs, indicators and structural paths without imposing strict distributional assumptions on the data (Hair et al., Citation2019). The analysis of the output results involved two main steps: the evaluation of the measurement models and the evaluation of the structural model (Hair et al., Citation2016; Ringle et al., Citation2015).

Furthermore, to test the differences between gender and fields of science, the authors employed the Mann–Whitney U test to analyze the data. The Mann–Whitney U test is a non-parametric statistical test used to compare two independent groups when the dependent variable is measured on an ordinal or continuous scale (Field, Citation2009; Siegel, Citation1956). It is particularly suitable when the assumptions of parametric tests, such as the t-test, are not met. By using the Mann–Whitney U test, the authors were able to examine if there were significant differences between gender and fields of science in the variables of interest. This test allows for the comparison of ranks or the distribution of scores between groups, providing valuable insights into any potential differences observed.

4. Result and discussion

4.1. Normality and homogeneity test

The collected data were examined for normality using statistical tests. presents the results of the normality tests for each variable. Based on the test results, it is observed that only the variable ‘Entrepreneurship Education’ exhibited normal distribution, as indicated by a p value greater than .05. On the other hand, the variables ‘Entrepreneurial Orientation’, ‘Patriarchal Culture’ and ‘Entrepreneurial Intentions’ were not normally distributed, with p values less than .05. Given these findings, non-parametric tests, which do not rely on normal distribution assumptions will be used to analyze the data in this study.

Table 3. Normality and homogeneity test.

4.2. Evaluation of measurement models

The measurement model was evaluated based on three aspects: convergent validity, internal consistency and discriminant validity. Convergent validity examines the extent to which a measure correlates with other measures of the same construct (Hair et al., Citation2016). In this study, 1000 subsamples bootstrapping was conducted to assess convergent validity. The loadings factor and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for each construct exceeded the minimum threshold of 0.5, indicating satisfactory convergent validity (). Internal consistency reliability measures the consistency of results across items within the same construct, indicating the similarity of items measuring a construct (Hair et al., Citation2016). Composite reliability and Cronbach’s Alpha were used to evaluate internal consistency. demonstrates that all constructs met the minimum requirement of 0.6 for both composite reliability and Cronbach’s Alpha, indicating adequate internal consistency reliability. Discriminant validity assesses the distinctiveness of one construct from others based on empirical standards (Hair et al., Citation2016). Instead of using the Fornell-Larcker criterion and cross-loadings, which have faced criticism, Henseler et al. (Citation2015) propose the use of Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio (HTMT). The HTMT value should not include 1, and lower values are preferred (Henseler et al., Citation2016). However, for conservative purposes, a value below 0.08 is considered acceptable. indicates that none of the constructs have an HTMT value of 1, and all values are below 0.08, indicating good fit and satisfactory discriminant validity. Overall, the evaluation of the measurement model demonstrates satisfactory results for convergent validity, internal consistency reliability and discriminant validity.

Table 4. Results for convergent validity and internal consistency reliability.

4.3. Evaluation of structural model and hypothesis testing

After ensuring the reliability and validity of the constructs, the next step is to evaluate the structural model. Three criteria are used to assess the structural model in PLS-SEM: R2 values, f2 effect size and SRMR (Hair et al., Citation2016). The coefficient of determination (R2 values) represents the amount of variance in the endogenous constructs explained by all exogenous constructs linked to it and ranges from 0 to 1 (Hair et al., Citation2016). An R2 value of 0.2 is considered adequate. shows that the R2 coefficient is 0.638, indicating that the exogenous constructs explain 63.8% of the variance in the endogenous construct, which is considered adequate. The f2 coefficient is used to evaluate the effect size. Cohen (Citation2013) provides guidelines where f2 values of 0.02, 0.15 and 0.35 represent small, medium and large effects, respectively. From , we can conclude that patriarchal culture and entrepreneurial orientation have a small effect size, while entrepreneurship education has a medium effect size on both entrepreneurial intention and entrepreneurial orientation. The last criterion for evaluating the structural model is the SRMR. SRMR assesses the root mean square discrepancy between the observed and model-implied correlations, with a value of zero indicating a perfect fit (Hair et al., Citation2016). Following a conservative approach, values below 0.09 indicate a good fit. shows that the SRMR coefficient indicates a good fit, with a value of 0.077. Overall, the evaluation of the structural model based on R2 values, f2 effect size, and SRMR suggests that the model provides a satisfactory fit to the data.

Table 5. Result for discriminant validity – HTMT.

Table 6. Result for structural model evaluation.

In the evaluation of the path relationships between variables for hypothesis testing, presents the results. Out of the six hypotheses, four are significant. The first main path is from entrepreneurship education to entrepreneurial intention. The path coefficient is significant, with β = 0.414, p = .002, indicating a positive and significant effect of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention. Therefore, hypothesis 1 is confirmed. Entrepreneurship education also shows a positive and significant effect on entrepreneurial orientation, with β = 0.850, p = .000. Hypothesis 2 is confirmed. Furthermore, entrepreneurship education has a positive and significant effect on entrepreneurial intention, with β = 0.416, p = .000. This confirms hypothesis 3. On the other hand, the effect of patriarchal culture is positive but not significant, with β = 0.057, p = .261. Hypothesis 4 is not confirmed. This result is consistent for the female sample as well, with β = 0.090, p = .155. Additionally, patriarchal culture has a negative effect on entrepreneurial intention, although insignificant, with β = −0.010, p = .834. This means hypothesis 5 is not confirmed. The finding is also consistent for the female sample. The last main path is the mediation of entrepreneurship orientation. The results indicate that entrepreneurship orientation mediates the relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intention, with β = 0.383, p = .003. Hence, hypothesis 6 is confirmed.

Table 7. Hypothesis testing and main path coefficient.

To further analyze the differences in entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial orientation, entrepreneurial intention and patriarchal culture based on educational background and gender, the Mann–Whitney U test was conducted. shows that there are no significant differences between education majors and non-education majors for all variables. The p values for entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurship orientation, entrepreneurial intention and patriarchal culture are .287, .617, .511 and .346, respectively. presents the differences between male and female samples. Only patriarchal culture shows a significant difference between males (Mdn = 3.462) and females (Mdn = 2.538), with U = 2778.5, z = −3.198, p = .001. However, there is no significant difference between the two groups for the other three variables. Overall, the findings support several hypotheses regarding the relationships between variables. However, there were no significant differences based on educational background, and only patriarchal culture differed significantly between male and female samples.

Table 8. Differences in entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial orientation, entrepreneurial intentions and patriarchal culture based on educational background.

Table 9. Differences in entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial orientation, entrepreneurial intentions and patriarchal culture based on gender.

4.4. The role of entrepreneurship education in entrepreneurship orientation

illustrates that entrepreneurship education has a positive impact on entrepreneurial orientation. However, previous research has also shown a weak correlation between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial orientation (Bilić et al., Citation2011). They argue that higher levels of education, such as postgraduate studies, exhibit higher entrepreneurial orientation due to the continuity from undergraduate education. Additionally, entrepreneurship education has been found to positively influence student innovation and proactiveness, which are two dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation (Marques et al., Citation2018). On the other hand, other studies, such as Cho and Lee (Citation2018), suggest that entrepreneurship education does not significantly relate to entrepreneurial orientation or business performance. They further emphasize that entrepreneurship education is less effective for individuals with prior work experience compared to students without work experience. These findings highlight the importance of organizing entrepreneurship education within educational institutions. Understanding the entrepreneurial orientation of students and their inclination toward innovation and proactiveness is crucial. Such insights can guide curriculum designers in creating learning experiences that foster innovation and proactiveness among students. Moreover, in the business realm, entrepreneurial orientation has a direct correlation with firm performance in the United States (Jeong et al., Citation2019).

4.5. The role of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intentions

The research findings indicate that entrepreneurship education has a significant direct influence on entrepreneurial intentions. Studies conducted by Sriyakul and Jermsittiparsert (Citation2019), Hutasuhut et al. (Citation2020), Handayati et al. (Citation2020), Martínez-Gregorio et al. (Citation2021) and Hassan et al. (Citation2021) all support the positive impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intentions. Implementing entrepreneurship education can inspire students to cultivate an entrepreneurial mindset (Cui et al., Citation2021; Ndou et al., Citation2019). Ndou et al. (Citation2019) further explain that entrepreneurship education plays a role in enhancing the entrepreneurial mindset by developing capacities, competencies and attitudes necessary for transforming new ideas, technology and discovering business value in products and services Al-Suraihi et al. (Citation2020). Entrepreneurship education not only equips individuals with technical competencies such as business plan development and accessing venture capital investments but also fosters creativity and the courage to take appropriate risks (Martins & Perez, Citation2020).

Furthermore, Fayolle and Hindle (Citation2013) emphasize that entrepreneurship education effectively internalizes experiences, knowledge, values and norms in students. Many aspiring entrepreneurs lack detailed knowledge of the business environment and are unsure of the steps required to start a company (Liñán & Santos, Citation2007). Entrepreneurship education is of paramount importance as it helps students develop the skills and competencies necessary to seize business opportunities (Saptono et al., Citation2021).

In this context, education proves to be beneficial in significantly increasing the number of individuals interested in starting a business. Entrepreneurship education can enhance students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Martínez-Gregorio et al. (Citation2021) explain that students’ initial low entrepreneurial intentions can be heightened throughout the course as they discover aspects of entrepreneurship that resonate with their interests. Although the level of entrepreneurship among women is lower, they receive higher levels of entrepreneurship education compared to men (Nowiński et al., Citation2019). The findings of this study affirm that entrepreneurship education can effectively cultivate new entrepreneurs. Individuals who undergo entrepreneurship education can enhance their knowledge, skills and positive attitudes toward entrepreneurship.

4.6. The role of entrepreneurial orientation on entrepreneurial intentions

demonstrates that entrepreneurial orientation has a significant influence on entrepreneurial intentions. These findings support previous research conducted by Hassan et al. (Citation2021) and also Ibrahim and Lucky (Citation2014), which highlight the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and strong entrepreneurial intentions, emphasizing its importance in realizing students’ entrepreneurial aspirations. Individual entrepreneurial orientation is positively associated with entrepreneurial intentions (Ibrahim & Mas’ud, Citation2016; Kumar et al., Citation2020). Earlier work by Wiklund (Citation1999) also suggested that entrepreneurial orientation is linked to firm performance. The concept of entrepreneurial orientation was initially introduced by Miller (Citation1983) within the context of firms. Miller proposed that entrepreneurial firms should have a focus on innovation and proactivity to outperform competitors. According to Miller, innovation involves taking risks, while proactivity is a vital characteristic of entrepreneurial firms. Wardoyo et al. (Citation2015) noted that an individual’s entrepreneurial orientation can be measured by their creativity, innovation, risk-taking propensity and diligence. Hence, high entrepreneurial orientation signifies possessing creativity, innovation capabilities, risk-taking propensity and a strong work ethic to achieve goals. These findings underscore the importance of enhancing individual entrepreneurial orientation to foster greater interest in entrepreneurship.

4.7. The role of patriarchal culture on entrepreneurial orientation and intentions

Based on the results of the hypothesis testing presented in , it appears that patriarchal culture does not have a significant negative influence on entrepreneurial orientation and entrepreneurial intention, both overall and specifically for females. This suggests that the patriarchal culture adopted by students generally does not hinder their entrepreneurial orientation and intentions. This finding differs from the research conducted by Wahdiniwaty and Rustam (Citation2019) on women entrepreneurs in Indonesia, where patriarchal culture was found to be a hindering factor. This difference could be attributed to the fact that women entrepreneurs typically have a married status, whereas students, who were the focus of this study, are generally younger (between 18 and 24 years old) and unmarried. Married women entrepreneurs often face the challenge of balancing their roles as entrepreneurs and housewives.

In the current landscape, women entrepreneurs are determined to challenge the injustices imposed by the patriarchal system. In the Indonesian context, patriarchal culture strongly influences the cultural norms adopted by the community. Men hold primary control in society, while women have limited influence or access to various aspects such as economy, social sphere, politics and psychology, including marriage. Patriarchal culture restricts and discriminates against women, creating inequalities in roles and opportunities, thus hindering their access to equal opportunities (Sakina & Siti A, Citation2017).

Afrianty (Citation2020) conducted a study on socio-cultural factors, including religious teachings, that significantly influence women’s decisions to become entrepreneurs. In the Indonesian context, patriarchal culture and the teachings of Islam (the majority religion) significantly shape women’s mindsets. Traditional roles define women as daughters and wives primarily responsible for taking care of the family. Patriarchal culture and Islamic teachings prioritize the family’s needs (children and husband) as the main focus (Loh & Dahesihsari, Citation2013). Yusuf (Citation2013) also argues that in a patriarchal society, gender, ethnicity and religion play crucial roles in women’s entrepreneurship. Patriarchal cultural values are deeply embedded in the Muslim identity (Alexander & Welzel, Citation2011). Islamic teachings uphold the dignity of women, emphasizing their roles as mothers in charge of household duties, while men are expected to be breadwinners and work outside the home. Women are designated to fulfill traditional domestic tasks, and Islam discourages their active participation beyond their domestic roles (Anwar, Citation2017). Omara (Citation2004) states that human nature, determined by God, cannot be altered by the most advanced technology. Patriarchal culture consists of two dimensions: domestic patriarchy (private) and public patriarchy (Walby, Citation2011). Domestic patriarchy reinforces stereotypes that associate women with domestic work, while men are associated with work in public spaces.

Upon further examination from a gender perspective, it is found that there is no difference in entrepreneurial orientation and entrepreneurial intentions among students, indicating no disparity between men and women (refer to ). However, when considering the influence of Patriarchal Culture, significant differences between genders become evident. These differences reflect the impact of the patriarchal culture adopted by the students’ families, which prioritizes boys over girls. This is supported by the higher median score for males compared to females. Despite this interesting finding, the strength of the patriarchal culture does not hinder female students from entering the world of entrepreneurship, as evidenced by the absence of differences in entrepreneurial intentions between genders. A similar research conducted by Dao et al. (Citation2021) in Vietnam also revealed no gender difference in the entrepreneurial intentions of business students, except for higher entrepreneurial intentions among male engineering students compared to their female counterparts.

This study also investigates whether there are disparities between non-educational major and educational major fields of science in terms of entrepreneurial orientation and entrepreneurial intentions. The results indicate no differences between genders in both aspects (see ). This finding aligns with previous research that suggests educational background has no impact on entrepreneurial intentions, as stated by Hutasuhut (Citation2018). Therefore, it can be concluded that, within the context of interest in entrepreneurship, there is no direct relationship between patriarchal culture and the level of entrepreneurial intention between genders. This could be attributed to the higher education level of the respondents, as research by Alexander and Welzel (Citation2011) suggests that education and emancipation trends tend to reduce patriarchal values more quickly among Muslim women compared to Muslim men.

In a patriarchal cultural system, boys are often given more authority in family decisions and greater freedom to take action for themselves compared to girls. This distinction is even more pronounced in Batak families, where sons are considered successors of the lineage (marga). Sons carry on their father’s surname, which is traditionally the same as or derived from their grandfather’s surname. As a result, boys are expected to achieve greater success than girls within Batak families.

The influence of patriarchal culture remains strong within the students’ families, particularly considering that 71.37% of the research respondents belong to the Batak ethnic group. The Batak ethnicity, which includes subgroups such as Toba, Mandailing, Karo, Simalungun and Pakpak/Dairi (refer to ), is known for its adherence to patriarchal traditions. In the Batak Toba community, women are marginalized and their customs prioritize the male side, viewing women as complementary rather than equal. Women are primarily valued for their ability to give birth to sons, who continue the lineage of male ancestors and are highly respected (Hutabarat & Warsito, Citation2009). Additionally, boys receive preferential educational opportunities, as they are expected to become the future heads of households responsible for providing for their wives and children.

4.8. Mediation effect of entrepreneurial orientation

Entrepreneurial orientation emerges as a significant partial mediating variable, as indicated in . The inclusion of entrepreneurial orientation variables enhances the impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intentions. These research findings emphasize the significance of cultivating entrepreneurial orientation among students to foster their entrepreneurial spirit. The results suggest that entrepreneurship education has a positive influence on entrepreneurial intentions when students possess an innovative mindset, a competitive drive and a willingness to take risks. This study provides valuable insights into the role of entrepreneurial orientation in shaping entrepreneurial intentions among students. It is noteworthy that existing research predominantly focuses on the corporate context, such as the work by Genc et al. (Citation2019), which explores how entrepreneurial orientation improves the innovation performance of companies in developing countries, or the studies by McGee and Peterson (Citation2019) and Kantur (Citation2016), which examine the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and company performance, both financial and non-financial.

5. Conclusion

This study delves into the influence of entrepreneurship education and patriarchal culture on entrepreneurial orientation and entrepreneurial intentions. Additionally, it examines the mediating role of entrepreneurial orientation in the relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions. The findings reveal a significant positive effect of entrepreneurship education on both entrepreneurial orientation and entrepreneurial intentions. This finding corroborates the findings by Martins et al. (Citation2022) that conducted in Columbia and Ecuador, found that entrepreneurial education has implication to impacts individual entrepreneurial orientation, increases innovativeness, proactiveness and risk taking. These results reinforce the theoretical foundation supporting the importance of providing entrepreneurship education to students as it enhances their entrepreneurial orientation and intentions. Effective entrepreneurship education serves as a catalyst for cultivating new entrepreneurs among students.

Interestingly, patriarchal culture does not appear to impede students’ entrepreneurial orientation and intentions. These results match those observed in earlier studies. Study by Anlesinya et al. (Citation2019) that conducted in Ghana setting, found that collectivism and masculine cultural orientation do not have any effect on the intention of female students to engage in formal entrepreneurial activity. This suggests that, in general, the patriarchal culture adopted by students does not hinder their potential as entrepreneurial candidates, including women. However, there are gender-based differences in patriarchal culture scores, with boys receiving greater priority within student families. Nevertheless, this disparity does not negatively impact the level of entrepreneurial orientation and intentions, as no significant differences are observed between genders. This novel information holds significance in the field of entrepreneurship and should be considered by entrepreneurship educators when designing gender-inclusive entrepreneurship programs.

Furthermore, entrepreneurial orientation is identified as a partial mediating variable in the relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions. This present findings seem to be consistent with other research which found individual entrepreneurial orientation and entrepreneurial motivation independently and serially mediated the relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions (Otache et al., Citation2022). This implies that entrepreneurship education has a positive impact on entrepreneurial intentions, particularly when students possess an innovative, competitive spirit and are willing to undertake substantial risks.

It is important to note that this research has limitations, as it was conducted solely within one university belonging to the economics domain. Future studies should aim to expand the sample size by including diverse universities, both public and private and encompassing a wider range of academic disciplines. Additionally, there is a need for further exploration in constructing a patriarchal cultural framework specific to entrepreneurial intentions.

6. Theoretical and practical contributions

This study contributes to both theoretical understanding and practical implications within the domain of entrepreneurship education and its interaction with patriarchal culture. Theoretically, this research extends existing knowledge by elucidating the influence of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial orientation and intentions, particularly within the context of patriarchal cultures. By confirming the positive impact of entrepreneurship education on both entrepreneurial orientation and intentions, this study reinforces the theoretical underpinnings that advocate for the integration of entrepreneurship education into academic curricula. Moreover, the identification of entrepreneurial orientation as a partial mediator in the relationship between entrepreneurship education and intentions enriches our understanding of the underlying mechanisms driving entrepreneurial behavior among students.

Practically, the findings of this study offer valuable insights for educators and policymakers. Firstly, they underscore the importance of incorporating entrepreneurship education programs that foster innovative thinking, proactiveness and risk-taking attitudes among students. By doing so, educational institutions can effectively nurture the entrepreneurial mindset essential for future entrepreneurial endeavors. Secondly, the observation that patriarchal culture does not hinder entrepreneurial orientation and intentions highlights the potential for promoting entrepreneurship among all students, irrespective of gender. However, the gender-based differences in patriarchal culture scores necessitate a nuanced approach in designing gender-inclusive entrepreneurship programs. Educators should strive to create an environment that empowers aspiring entrepreneurs, regardless of gender and actively addresses any disparities in familial expectations.

7. Limitations and future directions

Despite the valuable insights gained from this study, it is important to recognize its limitations. The research was conducted within a single university and focused solely on the economics domain, limiting the ability to generalize the findings. Future studies should aim to address this by involving diverse universities and academic disciplines, providing a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between entrepreneurship education, patriarchal culture and entrepreneurial intentions. Moreover, the finding that patriarchal culture does not negatively impact entrepreneurial intention or orientation needs to be examined in samples with different groups. The focus of this research was on undergraduate students, where the sample demographics include none who are married. Further research needs to be conducted on groups with older age demographics and marital status to understand if patriarchal culture adversely affects entrepreneurial intention and orientation when women are married, given that the Gender Gap Report in Indonesia is not yet favorable. Additionally, there’s a necessity for further exploration in developing a robust framework to comprehend patriarchal cultural influences on entrepreneurial intentions, which could lay the groundwork for designing targeted interventions and policies.

Author contributions

Saidun Hutasuhut: conceptualized the study, analyzed the data and revised the draft.

Reza Aditia: analyzed the data and wrote the initial draft.

Thamrin: provided critical feedback, collecting data and edited the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data and materials are available on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Saidun Hutasuhut

Saidun Hutasuhut is a Professor at Management Department, Universitas Negeri Medan. He has research interest in entrepreneurship education.

Reza Aditia

Reza Aditia is an Assistant Professor at Accounting Education Department, Universitas Muhamamdiyah Sumatera Utara. Currently, he is pursuing his Ph.D. studies at Eotvos Lorand University. His primary research interest lies in exploring the use of technology to improve teaching and learning outcomes, and inequity in education.

Thamrin

Thamrin is a Professor at Business Education Department, Universitas Negeri Medan. He has research interest in online learning.

References

- Afrianty, T. W. (2020). Peran feasibility dan entrepreneurial self-efficacy dalam memediasi pengaruh pendidikan kewirausahaan terhadap niat berwirausaha. AdBispreneur, 4(3), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.24198/adbispreneur.v4i3.25181

- Ahmetaj, B., Kruja, A. D., & Hysa, E. (2023). Women entrepreneurship: Challenges and perspectives of an emerging economy. Administrative Sciences, 13(4), 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci13040111

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Alexander, A. C., & Welzel, C. (2011). Islam and patriarchy: How robust is Muslim support for patriarchal values? International Review of Sociology, 21(2), 249–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/03906701.2011.581801

- Al-Suraihi, A.-H. A., Ab Wahab, N., & Al-Suraihi, W. A. (2020). The effect of entrepreneurship orientation on entrepreneurial intention among undergraduate students in Malaysia. Asian Journal of Entrepreneurship, 1(3), 14–25.

- Anlesinya, A., Adepoju, O. A., & Richter, U. H. (2019). Cultural orientation, perceived support and participation of female students in formal entrepreneurship in the sub-Saharan economy of Ghana. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 11(3), 299–322. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJGE-01-2019-0018

- Anwar, A. (2017). Implikasi budaya patriarki dalam kesetaraan gender di lembaga pendidikan madrasah (studi kasus pada madrasah di kota Parepare). Al-MAIYYAH: Media Transformasi Gender Dalam Paradigma Sosial Keagamaan, 10(1), 45–67. https://doi.org/10.35905/almaiyyah.v10i1.455

- Apostu, S.-A., & Gigauri, I. (2023). Sustainable development and entrepreneurship in emerging countries: Are sustainable development and entrepreneurship reciprocally reinforcing? Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation, 19(1), 41–77. https://doi.org/10.7341/20231912

- Arasti, Z., Kiani Falavarjani, M., & Imanipour, N. (2012). A study of teaching methods in entrepreneurship education for graduate students. Higher Education Studies, 2(1), 2–10. https://doi.org/10.5539/hes.v2n1p2

- Ashmore, M. C. (2006). Entrepreneurship everywhere: The case for entrepreneurship education. Consortium for Entrepreneurship Education (Hrsg.).

- Bae, T. J., Qian, S., Miao, C., & Fiet, J. O. (2014). The relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions: A meta–analytic review. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(2), 217–254. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12095

- Bamfo, B. A., Asiedu-Appiah, F., & Ameza-Xemalordzo, E. (2023). Developing a framework for entrepreneurship ecosystem for developing countries: The application of institutional theory. Cogent Business & Management, 10(2), 2195967. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2195967

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action. 1986(23–28).

- Bilić, I., Prka, A., & Vidović, G. (2011). How does education influence entrepreneurship orientation? Case study of Croatia. Management: Journal of Contemporary Management Issues, 16(1), 115–128. https://hrcak.srce.hr/69394

- Bui, H. T. M., Kuan, A., & Chu, T. T. (2018). Female entrepreneurship in patriarchal society: Motivation and challenges. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 30(4), 325–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/08276331.2018.1435841

- Camelo-Ordaz, C., Diánez-González, J. P., & Ruiz-Navarro, J. (2016). The influence of gender on entrepreneurial intention: The mediating role of perceptual factors. BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 19(4), 261–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brq.2016.03.001

- Cho, Y. H., & Lee, J.-H. (2018). Entrepreneurial orientation, entrepreneurial education and performance. Asia Pacific Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 12(2), 124–134. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJIE-05-2018-0028

- Cohen, J. (2013). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Academic Press.

- Covin, J. G., & Wales, W. J. (2012). The measurement of entrepreneurial orientation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(4), 677–702. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00432.x

- Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research: Planning, conducting and evaluating (4th ed.). Person.

- Cui, J., Sun, J., & Bell, R. (2021). The impact of entrepreneurship education on the entrepreneurial mindset of college students in China: The mediating role of inspiration and the role of educational attributes. The International Journal of Management Education, 19(1), 100296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2019.04.001

- Dao, T. K., Bui, A. T., Doan, T. T. T., Dao, N. T., Le, H. H., & Le, T. T. H. (2021). Impact of academic majors on entrepreneurial intentions of Vietnamese students: An extension of the theory of planned behavior. Heliyon, 7(3), e06381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e06381

- Davis, A. E., & Shaver, K. G. (2012). Understanding gendered variations in business growth intentions across the life course. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(3), 495–512. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00508.x

- Duong, C. D. (2022). Exploring the link between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions: The moderating role of educational fields. Education + Training, 64(7), 869–891. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-05-2021-0173

- Efrata, T., Radianto, W. E. D., & Effendy, J. A. (2021). The dynamics of individual entrepreneurial orientation in the relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intention. Jurnal Aplikasi Manajemen, 19(3), 688–693. https://doi.org/10.21776/ub.jam.2021.019.03.20

- Egel, E. (2021). What hinders me from moving ahead? Gender identity’s impact on women’s entrepreneurial intention. In J. Marques (Ed.), Exploring gender at work (pp. 231–252). Springer International. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-64319-5_13

- Fatima, T., & Bilal, A. R. (2019). Achieving SME performance through individual entrepreneurial orientation. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 12(3), 399–411. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-03-2019-0037

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

- Fayolle, A., & Gailly, B. (2015). The impact of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial attitudes and intention: Hysteresis and persistence. Journal of Small Business Management, 53(1), 75–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12065

- Fayolle, A., & Hindle, K. (2013). Teaching entrepreneurship at university: From the wrong building to the right philosophy. In Handbook of research in entrepreneurship education (Vol. 1, pp. 104–126). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781847205377.00013

- Field, A. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS. Sage.

- Gallant, M., Majumdar, S., & Varadarajan, D. (2010). Outlook of female students towards entrepreneurship. Education, Business and Society: Contemporary Middle Eastern Issues, 3(3), 218–230. https://doi.org/10.1108/17537981011070127

- Genc, E., Dayan, M., & Genc, O. F. (2019). The impact of SME internationalization on innovation: The mediating role of market and entrepreneurial orientation. Industrial Marketing Management, 82, 253–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2019.01.008

- Global Entrepreneurship and Development Index. (2019). Global Entrepreneurship Index 2019.

- Global Gender Gap Report 2023. (2023). World economic forum. https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2023.pdf

- Grine, F., Fares, D., & Meguellati, A. (2015). Islamic spirituality and entrepreneurship: A case study of women entrepreneurs in Malaysia. The Journal of Happiness\& Well-Being, 3(1), 41–56.

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage.

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Handayati, P., Wulandari, D., Soetjipto, B. E., Wibowo, A., & Narmaditya, B. S. (2020). Does entrepreneurship education promote vocational students’ entrepreneurial mindset? Heliyon, 6(11), e05426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05426

- Hassan, A., Anwar, I., Saleem, I., Islam, K. M. B., & Hussain, S. A. (2021). Individual entrepreneurial orientation, entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intention: The mediating role of entrepreneurial motivations. Industry and Higher Education, 35(4), 403–418. https://doi.org/10.1177/09504222211007051

- Haus, I., Steinmetz, H., & Isidor, R. (2013). Gender effects on entrepreneurial intention: A meta-analytical structural equation model. International Journal of Logistics Management, 5(2), 130–156. https://doi.org/10.1108/09574090910954864

- Henseler, J., Hubona, G., & Ray, P. A. (2016). Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 116(1), 2–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-09-2015-0382

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Hoang, G., Le, T. T. T., Tran, A. K. T., & Du, T. (2020). Entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions of university students in Vietnam: The mediating roles of self-efficacy and learning orientation. Education + Training, 63(1), 115–133. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-05-2020-0142

- Hutabarat, D. A., & Warsito. (2009). Strategi Politik Perempuan dalam Dominasi Sistem Patriarki Batak Toba. Journal of Politic and Government Studies, 8(02), 191–200.

- Hutasuhut, S. (2018). The roles of entrepreneurship knowledge, self-efficacy, family, education, and gender on entrepreneurial intention. Dinamika Pendidikan, 13(1), 90–105. https://doi.org/10.15294/dp.v13i1.13785

- Hutasuhut, S., Irwansyah, I., Rahmadsyah, A., & Aditia, R. (2020). Impact of business models canvas learning on improving learning achievement and entrepreneurial intention. Jurnal Cakrawala Pendidikan, 39(1), 168–182. https://doi.org/10.21831/cp.v39i1.28308

- Ibrahim, N. A., & Lucky, E. O.-I. (2014). Relationship between entrepreneurial orientation, entrepreneurial skills, environmental factor and entrepreneurial intention among Nigerian students in UUM. Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management Journal, 2(4), 203–213.

- Ibrahim, N. A., & Mas’ud, A. (2016). Moderating role of entrepreneurial orientation on the relationship between entrepreneurial skills, environmental factors and entrepreneurial intention: A PLS approach. Management Science Letters, 6(3), 225–236. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2016.1.005

- Jeong, Y., Ali, M., Zacca, R., & Park, K. (2019). The effect of entrepreneurship orientation on firm performance: A multiple mediation model. Journal of East-West Business, 25(2), 166–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/10669868.2018.1536013

- Kantur, D. (2016). Strategic entrepreneurship: Mediating the entrepreneurial orientation-performance link. Management Decision, 54(1), 24–43. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-11-2014-0660

- Kelley, D. J., Baumer, B. S., Brush, C., Greene, P. G., Mahdavi, M., Majbouri, M., Cole, M., Dean, M., & Heavlow, R. (2017). Women’s entrepreneurship 2016/2017 report. Global Entrepreneurship Research Association. http://Gemconsortium.org/Checked On.

- Krueger, N. F., Reilly, M. D., & Carsrud, A. L. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5-6), 411–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(98)00033-0

- Kumar, S., Paray, Z. A., & Dwivedi, A. K. (2020). Student’s entrepreneurial orientation and intentions. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 11(1), 78–91. https://doi.org/10.1108/HESWBL-01-2019-0009

- Kusmintarti, A., Thoyib, A., Maskie, G., & Ashar, K. (2016). Entrepreneurial characteristics as a mediation of entrepreneurial education influence on entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 19(1), 24–37.

- Küttim, M., Kallaste, M., Venesaar, U., & Kiis, A. (2014). Entrepreneurship education at university level and students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 110, 658–668. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.12.910

- Liñán, F. (2004). Intention-based models of entrepreneurship education. Piccolla Impresa/Small Business, 3(1), 11–35.

- Liñán, F., & Chen, Y. W. (2009). Development and cross–cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 593–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00318.x

- Linan, F., Cohard, J. C. R., & Rueda-Cantuche, J. M. (2005). Factors affecting entrepreneurial intention levels. ERSA Conference Papers (No. ersa05p432).

- Liñán, F., & Santos, F. J. (2007). Does social capital affect entrepreneurial intentions? International Advances in Economic Research, 13(4), 443–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11294-007-9109-8

- Lindberg, E., Bohman, H., Hulten, P., & Wilson, T. (2017). Enhancing students’ entrepreneurial mindset: A Swedish experience. Education + Training, 59(7/8), 768–779. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-09-2016-0140

- Loh, J. M. I., & Dahesihsari, R. (2013). Resilience and economic empowerment: A qualitative investigation of entrepreneurial Indonesian women. Journal of Enterprising Culture, 21(01), 107–121. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218495813500052

- Marques, C. S. E., Santos, G., Galvão, A., Mascarenhas, C., & Justino, E. (2018). Entrepreneurship education, gender and family background as antecedents on the entrepreneurial orientation of university students. International Journal of Innovation Science, 10(1), 58–70. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJIS-07-2017-0067

- Martínez-Gregorio, S., Badenes-Ribera, L., & Oliver, A. (2021). Effect of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurship intention and related outcomes in educational contexts: A meta-analysis. The International Journal of Management Education, 19(3), 100545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2021.100545

- Martins, I., & Perez, J. P. (2020). Testing mediating effects of individual entrepreneurial orientation on the relation between close environmental factors and entrepreneurial intention. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 26(4), 771–791. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-08-2019-0505

- Martins, I., Perez, J. P., & Novoa, S. (2022). Developing orientation to achieve entrepreneurial intention: A pretest-post-test analysis of entrepreneurship education programs. The International Journal of Management Education, 20(2), 100593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2021.100593

- McGee, J. E., & Peterson, M. (2019). The long‐term impact of entrepreneurial self‐efficacy and entrepreneurial orientation on venture performance. Journal of Small Business Management, 57(3), 720–737. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12324

- Mies, M. (2014). Patriarchy and accumulation on a world scale: Women in the international division of labour. Bloomsbury.

- Miller, D. (1983). The correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms. Management Science, 29(7), 770–791. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.29.7.770

- Ndou, V., Mele, G., & Del Vecchio, P. (2019). Entrepreneurship education in tourism: An investigation among European Universities. Journal of Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism Education, 25, 100175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhlste.2018.10.003

- Neck, H. M., & Corbett, A. C. (2018). The scholarship of teaching and learning entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Education and Pedagogy, 1(1), 8–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515127417737286

- Nowiński, W., Haddoud, M. Y., Lančarič, D., Egerová, D., & Czeglédi, C. (2019). The impact of entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurial self-efficacy and gender on entrepreneurial intentions of university students in the Visegrad countries. Studies in Higher Education, 44(2), 361–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1365359

- Nshimiyimana, G. (2020). Effectiveness of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial orientation of undergraduate science students in Rwanda. Universität Leipzig.

- Omara, A. (2004). Perempuan, Budaya Patriarki dan Representasi. Mimbar Hukum, 2(2004).

- Otache, I., Edopkolor, J. E., & Kadiri, U. (2022). A serial mediation model of the relationship between entrepreneurial education, orientation, motivation and intentions. The International Journal of Management Education, 20(2), 100645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2022.100645

- Ozasir Kacar, S., Essers, C., & Benschop, Y. (2023). A contextual analysis of entrepreneurial identity and experience: Women entrepreneurs in Turkey. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 35(5-6), 460–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2023.2189314

- Pillis, E. D., & Dewitt, T. (2008). Not worth it, not for me ? Predictors of entrepreneurial intention in men and women. Journal of Asia Entrepreneurship and Sustainability, IV(3), 1–14.

- Plant, R., & Ren, J. (2010). A comparative study of motivation and entrepreneurial intentionality: Chinese and American perspectives. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 15(02), 187–204. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1084946710001506

- Potter, J. (2008). Entrepreneurship and higher education (J. Potter, Ed.). OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264044104-en

- Raimi, L., Panait, M., Gigauri, I., & Apostu, S. (2023). Thematic review of motivational factors, types of uncertainty, and entrepreneurship strategies of transitional entrepreneurship among ethnic minorities, immigrants, and women entrepreneurs. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 16(2), 83. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm16020083

- Raposo, M., & Do Paço, A. (2011). Entrepreneurship education: Relationship between education and entrepreneurial activity. Psicothema, 23(3), 453–457.

- Ringle, C. M., Wende, S., & Becker, J.-M. (2015). SmartPLS 3. SmartPLS GmbH.

- Robinson, S., & Stubberud, H. A. (2014). Elements of entrepreneurial orientation and their relationship to entrepreneurial intent. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, 17(2), 1–11.

- Roxas, B. (2014). Effects of entrepreneurial knowledge on entrepreneurial intentions: A longitudinal study of selected South-east Asian business students. Journal of Education and Work, 27(4), 432–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2012.760191

- Ruizalba Robledo, J. L., Vallespín Arán, M., Martin Sanchez, V., & Rodríguez Molina, M. Á. (2015). The moderating role of gender on entrepreneurial intentions: A TPB perspective. Intangible Capital, 11(1), 92–117. https://doi.org/10.3926/ic.557

- Sakina, A. I., & Siti A, D. H. (2017). Menyoroti Budaya Patriarki di Indonesia. Share: Social Work Journal, 7(1), 71. https://doi.org/10.24198/share.v7i1.13820

- Saptono, A., Wibowo, A., Widyastuti, U., Narmaditya, B. S., & Yanto, H. (2021). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy among elementary students: The role of entrepreneurship education. Heliyon, 7(9), e07995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07995

- Shastri, S., Shastri, S., Pareek, A., & Sharma, R. S. (2022). Exploring women entrepreneurs’ motivations and challenges from an institutional perspective: Evidences from a patriarchal state in India. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 16(4), 653–674. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-09-2020-0163

- Siegel, S. (1956). Nonparametric statistics for the behavioral sciences. McGraw-Hill.

- Sriyakul, T., & Jermsittiparsert, K. (2019). The mediating role of entrepreneurial passion in the relationship between entrepreneur education and entrepreneurial intention among university students in Thailand. International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change, 6(10), 193–212.

- Nuseir, M. T., Basheer, M. F., & Aljumah, A. (2020). Antecedents of entrepreneurial intentions in smart city of Neom Saudi Arabia: Does the entrepreneurial education on artificial intelligence matter? Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1825041. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1825041

- Taye, E. (2019). Perception of engineering students on entrepreneurship education. St. Mary’s University.

- Wahdiniwaty, R., & Rustam, D. A. (2019). Patriarchy as a barrier to women entrepreneurs in Indonesia. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, 662(3), 032042. https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/662/3/032042

- Walby, S. (2011). The impact of feminism on sociology. Sociological Research Online, 16(3), 158–168. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.2373

- Wardoyo, P., Rusdianti, E., & Purwantini, S. (2015). Pengaruh orientasi kewirausahaan terhadap strategi usaha dan kinerja bisnis UMKM di Desa Ujung-Ujung, Kec. Pabelan, Kab Semarang. Sustainable Competitive Advantage (SCA), 5(1), 1–19.

- Wiklund, J. (1999). The sustainability of the entrepreneurial orientation—Performance relationship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 24(1), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879902400103

- Yusuf, L. (2013). Influence of gender and cultural beliefs on women entrepreneurs in developing economy. Scholarly Journal of Business Administration, 3(5), 117–119.