Abstract

Business organizations are forced to prioritize ensuring corporate shared prosperity (CSP) through enhancing corporate sustainability performance and stakeholder’s betterment. There is a lack of comprehensive and quantifiable measurement of CSP and existing studies are conceptual and case study based. Thus, this study explores the essential dimensions involved in developing and verifying the corporate shared prosperity measurement which will help researchers to conduct empirical study. This scale development paper may prove valuable to both readers and scholars engaged in the field of sustainability and stakeholder development. Stakeholder theory is used as an underpinning theory. Sixteen (16) items under five (5) dimensions were developed to measure corporate shared prosperity after reviewing the existing literature, verifying by focus group discussion, and analyzing 229 Malaysian manufacturing firms responses using exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory composite analysis (CCA). This reliable and valid scale would benefit scholars in measuring CSP and examining the impact of sustainable performance on CSP. Further empirical evaluation based on this developed scale would ensure inclusive, sustainable development for stakeholders and make organizations more resilient. This research is a unique and initial attempt to develop a validated questionnaire survey based tool to measure corporate shared prosperity quantitatively.

1. Introduction

The escalating intricacy of economic, environmental, and social systems has precipitated crises, uncertainty, and risk as pervasive global concerns. Various economic sectors have experienced disruptions, imperilling the viability of enterprises (Hossain et al., Citation2022). An illustrative instance is the advent of COVID-19, which has engendered a tumultuous and precarious landscape, posing existential threats to organizational sustainability (Al-Omoush et al., Citation2022). Consequently, it is imperative for companies aspiring to achieve corporate shared prosperity to be equipped to confront the exigencies of a dynamic environment (Oliveira-Dias et al., Citation2022).

Hahn and Figge (Citation2011), Hahn and Kuhnen (Citation2013), and Oliveira-Dias et al. (Citation2022), advocate that organizations must ensure sustainable development to secure long-term prosperity. Sustainable development facilitates the seizing of opportunities and the management of risks across three dimensions: economic, environmental, and social (Hahn & Figge, Citation2011). Dedication to sustainable development serves to cultivate and fortify a rapport with external stakeholders, thereby enhancing the appeal of the organization to quality and talented individuals (Azapagic, Citation2003). This stems from the recognition within society of the pivotal role played by businesses in addressing societal challenges and the acknowledgment that the sustainable development agenda, encompassing the sustainable development goals, hinges on the active involvement of businesses (Sasaki et al., Citation2023). Moreover, sustainable development practices yield cost efficiencies, such as the implementation of novel streamlined processes and environmentally-friendly products (e.g. recycling) (MMSD, 2016). Additionally, ensuring sustainability entails fostering a conducive environment and promoting the well-being of stakeholders, consequently bolstering productivity (MMSD, 2016). Furthermore, an organization’s commitment to sustainability fosters trust and engenders a sense of belonging, fostering robust relationships and collaboration, which are instrumental in adeptly navigating unforeseen, intricate challenges (Collins & Saliba, Citation2020), thereby ensuring corporate shared prosperity. However, owing to the lack of a comprehensive measurement for gauging corporate shared prosperity within the sustainability framework, this relationship remains relatively underexplored and vague.

The term ‘shared prosperity’ has gained widespread usage in discussions pertaining to development policy. Shared prosperity entails ensuring that all members of society, present and future, participate in a dynamic process of ongoing welfare enhancement. It captures the notion that bringing each individual above the living threshold and maximising average income growth is insufficient for prosperity (Sabatino et al., Citation2022). In contrast, the context of this study is on business organisation, specifically a manufacturing organisation, and the definition of shared corporate prosperity has been redefined as the distribution of prosperity among the entire organisation and its stakeholders in terms of inclusive development, capability enhancement, knowledge sharing, promotion of meritocracy, reduction of income disparity, work-life balance, productivity, and a healthy working environment.

As a context, Malaysia is very relevant for this study since it prioritize shared prosperity for developing a sustainable nation and integrates Malaysia’s 2030 shared prosperity vision with the national plan. The focus of Twelfth Malaysian Plan-2019 will be increased on green growth to attain sustainability and resilience. The nation is pursuing corporate sustainable performance and has enacted several strategic economic growth and development programs among them focusing on the shared prosperity concept is one of them (Hossain et al., Citation2022). On the other flip, Malaysia’s 2030 shared prosperity vision aims to help to achieve the national plan by elevating the inequality. As per the Twelfth Malaysian Plan-2019, the shared prosperity vision endeavours to achieve three primary objectives. Firstly, it aims to enhance the development of all citizens at different levels through economic restructuring, which involves full community participation towards a more progressive, knowledge-based, and highly valued community. Secondly, it seeks to address income and wealth disparities by eliminating inequalities and ensuring that no individual is left behind. Lastly, it aims to establish a united, prosperous, and dignified nation through nation-building, with the ultimate goal of becoming Asia’s economic centre (Ministry of Economy, Citation2019).

Malaysia is one of the rapidly growing and expanding economies in the Asian area, and it is prospering on its path to becoming a fully developed country. With an estimated GDP of 372.70 billion US dollars in 2021, annual GDP growth of 8.9 per cent, and industrial growth of 12.1per cent until June 2022 (Trading Economics, Citation2022), the country is recognised as the third best-performing economy after Singapore and Thailand. Malaysia, despite this, placed 132 on the Global Sustainability Index (Earth.org, Citation2022). Malaysia ranks 65th out of 193 countries with a score of 70.88 out of 100, according to Sustainable Development Report- 2022 published by Sustainable Development Solutions Network (Citation2022).

Consequently, Malaysia faces significant levels of air and water pollution, which can be partly linked to the ineffective waste management of manufacturing firms. This is supported by the recent environmental performance index (Citation2022), demonstrating that the nation was performing poorly, ranked 130 among 180 countries in 2022. Specifically, the heavy metals group ranked 57 is a serious concern. In addition to ecological concerns, literature highlights economic and social unsustainability manifested through income inequality, discrimination, increased manufacturing accidents, neglect of stakeholders’ well-being, and inadequate infrastructure (DOSH., Citation2022; Hossain et al., Citation2023).

In the contemporary landscape, it is imperative for companies striving for long-term prosperity to be equipped to confront the aforementioned challenges inherent in a dynamic global environment. Meaningful profits necessitate companies to assume responsibility for their impacts on and interdependence with various stakeholders. However, this imperative has been eroded by the escalating dominance of shareholders, leading to the centralization of authority at the apex, as corporate boards increasingly prioritize the interests of their financial backers, the shareholders, over those affected by their actions (Mayer, Citation2023).

Embedding sustainability into the organizational ethos and engaging in sustainable practices enable stakeholder alignment with the concept of corporate shared prosperity, thereby fostering positive behaviors or corporate sustainable citizenship behavior that bolster the organization’s sustainability. The integration of sustainability into organizational operations equips stakeholders with the rationale behind sustainability initiatives, facilitates stakeholder identification with the corporate identity, and engenders supportive behaviors conducive to the organization’s sustainability, ultimately contributing to corporate shared prosperity. However, an exhaustive literature review (refer to ) underscores the predominance of case study and secondary country-level research methodologies, indicating a need for further theoretical and empirical exploration elucidating how organizational sustainability manifests in corporate shared prosperity indicators within organizations.

Table 1. Notable studies on shared prosperity.

Corporate shared prosperity is an outcome of sustainable practices in the organization especially economic and social sustainable practices. However, very minimal research linked green practices with green performance (Danso et al., Citation2019; Latan et al., Citation2018), financial performance (Petera et al., Citation2021), and social performance (Karia & Davadas Michael, Citation2022), but they still have not expanded on aftermath consequences which is corporate shared prosperity, due to the lack of comprehensive measurement scale. Thus, this study opens the path for further empirical study. Dang and Lanjouw (Citation2016) has demonstrated the presence of measurement challenges in the assessment of shared prosperity. These challenges are commonly associated with the complexities of breaking down national and state-level data into regional or institutional units, as well as the breakdown of industry data. Thus, this study is an attempt to fill theses gaps through conceptualizing corporate shared prosperity in manufacturing industry context and aims to collect and validate using quantitative survey based primary data to contribute in academic scholarship and industry practice.

2. Review of literature

2.1. Theoretical underpinning: stakeholder theory

Since the concept for corporate shared prosperity revolves around the idea that businesses should not only prioritize profit maximization but also actively contribute to the well-being of all stakeholders involved, including employees, customers, suppliers, communities, and the environment, the stakeholder theory is more relevant. Corporate shared prosperity, within the context of stakeholder theory, emphasizes the idea that businesses can thrive when they actively contribute to the well-being and prosperity of all stakeholders involved. Stakeholder theory emphasizes the importance of engaging with and understanding the needs, interests, and concerns of all stakeholders (Freeman et al., Citation2010). By actively involving stakeholders in decision-making processes, corporations can ensure that their actions are aligned with the broader goals of shared prosperity. This may involve soliciting feedback, conducting impact assessments, and fostering open dialogue to address conflicting interests and find mutually beneficial solutions. Corporate shared prosperity entails creating value not only for shareholders but also for other stakeholders (Phillips, Citation2005). Stakeholder theory recognizes that businesses achieve sustainable long-term success by generating value for employees, customers, suppliers, and communities (Mahajan et al., Citation2023). This may involve investing in employee development and well-being, delivering high-quality products and services that meet customer needs, fostering fair and ethical relationships with suppliers, and supporting community development initiatives. Stakeholder theory underscores the idea that businesses have a responsibility to act in the best interests of society and the environment, not just their own narrow interests (Zhou & Wei, Citation2023). Corporate shared prosperity requires corporations to recognize and fulfill their obligations to stakeholders, holding themselves accountable for the social, environmental, and economic impacts of their operations. This involve adopting responsible business practices, supporting social and environmental initiatives, and transparently reporting on performance measurement related to the shared prosperity goals.

2.2. Shared prosperity and its emergence

George Kozmetsky, who was awarded the National Medal of Technology, perceived technology and ideology as the two primary forces propelling economic transformation. During his later years, Kozmetsky, who was recognised globally as a scholar and entrepreneur, articulated a doctrine of ‘mutual prosperity domestically and internationally’ (Kozmetsky, Citation1997; Kozmetsky et al., Citation2001; Kozmetsky & Williams, Citation2003). The speeches delivered by Kozmetsky about this subject matter have served as a source of inspiration for numerous developing regions to establish internal networks encompassing economic, social, and governmental sectors, as well as to connect with similar regions located elsewhere. The observed outcomes were significant and favourable. The term ‘shared prosperity’ has been widely embraced by national governments, international organisations, and non-governmental organisations, as noted by Phillips (Citation2005).

The term ‘shared prosperity’ witnessed a significant surge in usage within the development policy literature from 2013, following its adoption by the World Bank Group to delineate the second of its ‘Twin Goals’ (Sabatino et al., Citation2022). During the month of April of the same year, the Board of Directors of the Bank officially approved the selection of two primary goals for the institution. These goals include the eradication of extreme poverty and the advancement of shared prosperity within the countries that the Bank serves. Academia, industry and policy makers start emphasizing and integrating shared prosperity into their researches, policies and practices.

2.3. Conceptualization of shared prosperity

International development organisations and policy makers have raised concerns about wealth creation and distribution like shared prosperity, sustainable development goals, environmental-social governance, and participatory governance. The conceptualization of shared prosperity revolves around the idea of inclusive economic growth and well-being that benefits all members of society, rather than just a privileged few. At its core, shared prosperity acknowledges that economic success should not be measured solely by aggregate indicators such as GDP growth or corporate profits, but also by the extent to which the benefits of growth are distributed equitably among different segments of the population.

A significant component of shared prosperity, as well as other related goals, spans outside the field of economics and is linked to the social compact that serves as its foundation (Wolfe & Patel, Citation2018). Each community’s social contract is based on a unique idea of social well-being, and this corresponds to the decisions made in that society about public policy, which defines the extent to which individuals of that community can cohabit in peace and prosperity. There should be a precise definition of the nature and structure of social welfare so that problems of shared prosperity and long-term sustainability can be expressed on a solid foundation that surpasses practical efforts.

To assist this effort, the Global Competitiveness Report (Citation2020) presents policymakers’ set priorities based on three timeframes: pre-crisis priorities, short-term revival priorities, and priorities for a sustainable future. Policymakers set a novel and unique vision, state-of-the-art benchmarks, and quantifiable actions in several key areas: Economic advancement, resurgence, change, equality in remuneration and employment, skills improvement, and diverse society.

Shared prosperity entails ensuring that wealth and opportunities generated by economic growth are distributed fairly across society, without leaving any group marginalized or excluded. This involves addressing income inequality, promoting social mobility, and creating pathways for disadvantaged individuals and communities to participate in and benefit from economic activities (Narayan et al., Citation2013).

Shared prosperity emphasizes the importance of inclusive economic growth, where the benefits of development are broadly shared across various demographic groups, regions, and sectors of the economy (Mhlanga & Ndhlovu, Citation2023). Inclusive growth goes beyond simply increasing overall wealth to ensuring that marginalized groups, such as women, minorities, and the rural poor, have access to economic opportunities and resources (Mhlanga & Ndhlovu, Citation2023). Due to the pandemic, there has been a significant halt in commercial openness and international migration decline. In both the revitalisation and transformation stages, governments should establish the groundwork for a better balance between the worldwide flow of goods, ensuring prosperity, and strategic perseverance at the domestic level (Ofori et al., Citation2022).

Shared prosperity fosters social cohesion and solidarity by promoting a sense of common purpose and collective responsibility for the well-being of all members of society. This involves investing in social safety nets, public services, and infrastructure (Mintchev et al., Citation2019) that enhance the quality of life for everyone, regardless of their socioeconomic status.

Shared prosperity recognizes the interdependence between economic, social, and environmental factors, and emphasizes the importance of sustainable development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. This involves promoting environmentally sustainable practices, reducing resource consumption, and mitigating the adverse impacts of economic activities on the planet and its inhabitants (Spencer et al., Citation2012). Before the pandemic, business leaders in several countries thought their governments were becoming more forward-thinking and ready for the future. However, the pandemic gave a different scenario. Governments have made advancements in setting up frameworks to speed up technology adoption and ensure sustainability. However, in general, organizations need to improve their preparedness and long-term vision to be ready for new challenges and to make proactive efforts to change in ways that lead to more productivity, shared prosperity, and sustainability.

Achieving shared prosperity requires collaboration and partnership among government, business, civil society, and other stakeholders. This involves creating inclusive decision-making processes, fostering dialogue and cooperation, and mobilizing resources and expertise to address shared challenges and pursue common goals (Yassin & Godinho, Citation2023).

Shared prosperity prioritizes human development and well-being as central goals of economic progress (Gatti et al., Citation2013). Human capital comprises people’s skills and abilities and is a critical factor in economic growth and productivity (The Global Competitiveness Report, Citation2020). Beyond material wealth, it encompasses factors such as health, education, social inclusion, and cultural enrichment, which contribute to individuals’ overall quality of life and happiness (Tambo et al., Citation2019; Wang & Ruan, Citation2024). Reskilling, upskilling, and updating education curricula are important ways to prepare workers and bring about prosperity for everyone (The Global Competitiveness Report, Citation2020).

Shared prosperity is an indicator of well-being and provides a guideline to governments and development organisations on where they should focus their efforts. However, measuring shared prosperity is complex and multifaceted (Dang & Lanjouw, Citation2016).

Phillips (Citation2005) provided several common elements of shared prosperity concepts such as interlocking networks, security issues, active cooperation, income equality, transparent finance, creating jobs, respect for stakeholders, preservation of law, human capital development, transparency and inclusiveness. On a similar note, Narayan et al. (Citation2013) also proposed poverty reduction, job creation, equal opportunity, growth as components of shared prosperity.

According to Marshall (Citation1998), the fundamental factors to be taken into account in a novel approach towards achieving communal prosperity are capital investment, educational prospects, decentralised management systems, incentives for value addition, and organisational learning, cutting-edge technologies, healthcare, policies aimed at granting autonomous power to all stakeholders, and social capital.

2.4. Shared prosperity in the organizational context

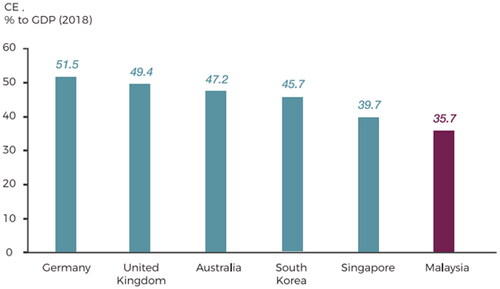

Laszlo and Zhexembayeva (Citation2011) and Barakat et al. (Citation2021) show that incorporating positive environmental and social results can lead to long-term competitive advantage and economic prosperity. Laszlo and Brown (Citation2014) conducted a study to investigate the attributes of thriving organisations, which foster an environment where employees can express their authentic selves and establish a connection between nature and humanity. Similarly, Leah (Citation2017) examined the progression of the organisational landscape as a component of the advancement of businesses towards achieving collective prosperity and promoting constructive social and environmental outcomes. Considering this perspective, this study adapts the shared prosperity concept to organizational setting, especially manufacturing firms since Pandey (Citation2021) and Spencer et al. (Citation2012) noted that corporate sustainability has an important influence on shared prosperity. However, economic unsustainability in Malaysia is evidenced as the remuneration of personnel as a percentage of GDP is much lower than in wealthy nations, at 35.7% ().

Figure 1. Compensation of employees.

Source: OECD. (Citation2022) and DOSM. (Citation2022).

Dutz (Citation2016) implies that poverty eradication is more critical while development is directed toward labour-intensive industries. However, for this to happen, development must be diverse and create jobs in various areas. While the private sector leads such economic change, the other businesses have to be critical in improving competitiveness, promoting an investment environment, and encouraging creativity (Pandey, Citation2021). This includes developing a stable legal and economic framework that allows the manufacturing sector in the right direction investing in physical infrastructure (Mintchev et al. (Citation2019) and people to create a modern workforce (Gatti et al., Citation2013).

A measurement for corporate shared prosperity must include resources and mechanisms that promote opportunities for all stakeholders. The existing body of literature on the measurement of shared prosperity in organisational contexts is currently limited. This study aims to fill the research gap by developing a scale of corporate shared prosperity, taking into account the variations in sustainability practises across different industries and contexts. The present study puts forth the subsequent two research inquiries:

RQ1: How can we measure corporate shared prosperity?

RQ2: What is the construct validity and reliability of the scale?

3. Methodology

3.1. Literature review methodology

As previously noted in the literature review and after conducting a systematic literature searching, to the best of the research’s knowledge, it is conclusive that there is lack of scale for assessing corporate shared prosperity. The current study followed the PRISMA framework for reviewing existing literature. This framework consisted of four steps named (1) identification, (2) screening, (3) eligibility and (4) included. The identification process of the articles has been conducted through the key search items, ‘Corporate shared prosperity’, (‘Corporate shared prosperity’ AND ‘Measurement’) and ‘Shared prosperity’ have been used in Web of Science, Scopus, Google scholar, Emerald, Science Direct. These search strategies identified zero records for corporate shared prosperity and 32900 results for shared prosperity. After completing the screening process with deleting the duplicates and irrelevant papers, total of 37 papers were considered eligible for the study and read many times to gather important information. Most of the papers are World Bank white paper, governmental reports, policy paper, case study and secondary data based study. Due to this dearth of scale measurement, the present study aims to construct a scale for evaluating corporate shared prosperity utilising the scale development guideline established by Churchill (Citation1979). The validation of the scale will be accomplished using an investigation into the reliability and validity of its construct.

3.2. Research design

The study employed data triangulation by utilising multiple secondary literature sources. No presuppositions regarding potential dimensions were made, and preliminary recommendations were derived from a focus group session. This study employs the exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory composite analysis (CCA) technique on the methodological front. CCA offers numerous advantages, as it serves both exploratory and confirmatory purposes. Additionally, CCA typically yields a greater number of items that are retained to measure constructs. Moreover, the approach evaluates all variables collectively and validates the measurement (Hair et al., Citation2020).

3.3. Methodological steps

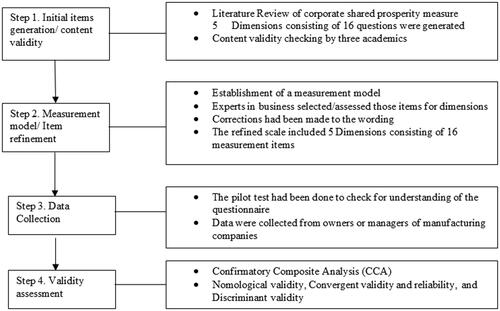

provides a summary of the procedural stages involved in the investigation. The process of developing a scale typically involves five distinct stages, namely: the generation of initial items, a check for content validity, the establishment of a measurement model, the refinement of items, and an assessment of validity. The study utilised the PLS-SEM methodology to evaluate the hypothesised model.

3.3.1. Item generation

In September 2022, a focus group meeting was conducted with owners and managers from the manufacturing industry. Owners and managers especially from sustainability compliance/corporate social responsibility department were invited to participate in focus group discussion since they are the most knowledgeable about the sustainability strategy implementation and their consequence rather than employees (Memon et al., Citation2020; Hossain, Citation2020). Rasoolimanesh et al. (Citation2023) evidenced that 77% article used literature review, 27% used focus group discussion and 12% used both for item generation. The focus group discussion included brainstorming activities. The measurement items presented in were obtained from relevant literature and sources were appropriately cited. The participants of the focus group were presented with the items and were requested to provide their opinions regarding the rationality of the categorization of the items. The identification of 16 measurement items about corporate shared prosperity was based on a thorough literature review and verification by focus group participants. In September 2022, a pilot test consisting 30 responses were collected to perform Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), which resulted in the identification of a five-factor structure of corporate shared prosperity and ensured variance of 78.10%. There were no instances of item deletion resulting from low or cross-loading.

Table 2. The initial generation of corporate shared prosperity dimensions and items.

3.3.1.1. Hypotheses development

3.3.1.1.1. Relationship between equality and non-discrimination and corporate shared prosperity

Promoting equality and preventing discrimination within an organization can have a significant impact on corporate shared prosperity. When employees feel valued, respected, and have equal opportunities, it creates a positive work environment that can lead to improved productivity, innovation, and overall organizational success (Hossain et al., Citation2022).

Organizations that prioritize equality and non-discrimination are more likely to attract a diverse and talented workforce. A diverse workforce brings different perspectives, skills, and experiences, fostering creativity and innovation (Hossain et al., Citation2022). A study by McKinsey & Company found that companies in the top quartile for gender diversity are 15% more likely to have financial returns above their respective national industry medians (McKinsey & Company, Citation2015). Moreover, inclusive workplaces where all employees feel valued and treated fairly contribute to higher levels of employee engagement. Engaged employees are more committed, motivated, and productive, which positively impacts overall corporate performance. A report by Gallup (Citation2016) states that highly engaged teams show a 21% increase in profitability which enhance the possibility of corporate shared prosperity.

Establishing policies and practices that promote equality and prevent discrimination helps organizations comply with legal requirements. This reduces the risk of legal actions, fines, and damage to the corporate image. The Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) emphasizes the importance of diversity and inclusion in mitigating legal risks (SHRM, Citation2019).

H1: Equality and non-discrimination influence significantly and positively on corporate shared prosperity

3.3.1.1.2. Relationship between infrastructure development (ID) and corporate shared prosperity

Organizational infrastructure encompasses various elements such as technology, facilities, processes, and human resources. Well-developed organizational infrastructure, including efficient processes and technology, contributes to improved operational efficiency and productivity within a company. According to a report by the Deloitte University Press (Citation2017), investments in technology infrastructure can lead to significant improvements in productivity and overall business performance. A robust organizational infrastructure fosters innovation by providing the necessary tools and resources for research, development, and creativity. Al-Taweel (Citation2021) highlights the impact of organizational infrastructure on employee retention and engagement. Infrastructure that supports a healthy work environment, including facilities and policies promoting work-life balance, contributes to employee well-being. The World Health Organization (WHO, Citation2021) emphasizes the importance of a healthy work environment in promoting employee well-being. Robust IT infrastructure is essential for data security and risk management. A secure organizational infrastructure helps protect sensitive information and mitigates potential risks. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST, Citation2018) provides guidelines on cybersecurity and risk management for organizations. Organizations with a focus on sustainability integrate it into their infrastructure development, contributing to corporate social responsibility and shared prosperity. The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) provides guidelines for organizations to report on their sustainability efforts, including infrastructure-related initiatives (GRI, Citation2016).

H2: Infrastructure development influence significantly and positively on corporate shared prosperity

3.3.1.1.3. Relationship between organizational stability and corporate shared prosperity

The relationship between organizational stability and corporate shared prosperity is crucial for sustained success and well-being within a company. Organizational stability involves factors such as financial health, unity among employees, productivity, effective leadership, and a positive workplace culture.

Financial stability is a cornerstone of organizational stability. A financially stable organization is better positioned to invest in its employees, innovation, and sustainable practices, leading to long-term prosperity. Carosi (Citation2016) highlights the positive impact of financial stability on corporate performance and prosperity. Stable organizations often have effective leadership that provides clear direction and support (Hossain et al., Citation2023). This leadership contributes to employee well-being, job satisfaction, and a positive work environment. Wang et al. (Citation2022) explores the relationship between leadership stability and employee outcomes.

Unity within an organization fosters a sense of belonging and engagement among employees. Engaged employees are more likely to be committed to the organization’s goals and contribute positively to its success. Eisenhardt and Graebner (Citation2007) explores the link between team identity, unity, and performance. Unified teams often collaborate more effectively, leading to increased productivity. Collaboration facilitates the sharing of ideas, expertise, and resources, contributing to better decision-making and problem-solving. The McKinsey Global Institute (Citation2012) emphasizes the positive impact of collaboration on productivity and innovation in its research. Employees who feel a sense of unity are more likely to share ideas, take risks, and contribute to creative problem-solving. Unity contributes to the development of a positive workplace culture, which, in turn, enhances corporate shared prosperity. A strong and positive culture fosters collaboration, employee satisfaction, and overall success (SHRM, Citation2016).

H3: Organizational stability influence significantly and positively on corporate shared prosperity

3.3.1.1.4. Relationship between stakeholder development (SD) and corporate shared prosperity

The relationship between stakeholder development and corporate shared prosperity is crucial for building sustainable, mutually beneficial relationships with various stakeholders, including employees, customers, investors, and the broader community. Investing in the development and well-being of employees is a key aspect of stakeholder development. Providing opportunities for skill enhancement, career growth, and a positive work environment contributes to corporate shared prosperity. Building strong relationships with customers through effective communication, quality products/services, and responsiveness to their needs is a fundamental aspect of stakeholder development. Satisfied customers contribute to long-term business success (Hossain et al., Citation2022). Stakeholder development extends to investors and involves transparent communication, adherence to ethical business practices, and good corporate governance. Positive relationships with investors contribute to financial stability and long-term prosperity (Fong et al., Citation2022). Engaging with the community and fulfilling social responsibilities are integral to stakeholder development. Socially responsible practices contribute to corporate shared prosperity by addressing community needs and building a positive brand image (D’amato et al., Citation2009). Stakeholder development extends to suppliers, involving fair and ethical business practices. Developing strong relationships with suppliers contributes to the creation of sustainable supply chains, ensuring stability and prosperity for all stakeholders involved. Stakeholder development includes maintaining positive relationships with regulatory authorities and ensuring legal compliance. Proactive engagement with regulators contributes to a stable business environment, supporting shared prosperity (Stiglitz, Citation2020).

H4: Stakeholder Development influence significantly and positively on corporate shared prosperity

3.3.1.1.5. Relationship between social wellbeing (SW) and corporate shared prosperity

Social well-being encompasses factors such as work-life balance, employee health, and a supportive workplace culture. Social well-being is closely tied to employee satisfaction, which, in turn, has a positive impact on productivity (Wright & Cropanzano, Citation2000). Employees who experience a sense of well-being in the workplace are likely to be more engaged and motivated. Social well-being includes considerations for work-life balance. Organizations that support a healthy balance between work and personal life contribute to employee retention and loyalty (Hossain et al., Citation2018). Social well-being is influenced by the organizational culture that fosters social connectivity and positive relationships among employees. A supportive culture contributes to a sense of belonging and shared prosperity.

H5: Social wellbeing influence significantly and positively on corporate shared prosperity

3.3.2. Content validity

Two experts were asked to classify the items presented independently into their respective dimensions and confirm that the items were a good representation of the underlying variable. The items underwent minor modifications in their phrasing and were subsequently categorised into the five dimensions after being rectified.

3.3.3. Measurement model

The entirety of the construct of CSP cannot be accounted for by any singular dimension. The present investigation conceptualised CSP as a reflective-reflective construct of second-order. The five dimensions of CSP were measured through the utilisation of sixteen indicators.

The participants were instructed to evaluate each question individually using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 3 (neutral) and 5 (strongly agree). According to the reflective measurement model, it is expected that the standardised loadings will exceed a value of 0.708. According to Hair et al. (Citation2019), the variance that is shared between an indicator and the construct can be determined by calculating the squares of the loadings.

3.3.4. Item refinement

A preliminary assessment involving approximately ten responses was performed to evaluate the comprehension of the survey questionnaire’s inquiries. The outcome of this pilot study was utilised to refine the questionnaire items. In addition, several professionals in the field of business management were extended an invitation to conduct an impartial evaluation of the 16 items. Researchers can improve the questionnaire and make sure the questions are well-formulated in light of the study’s objectives and are understandable to the respondents by employing pre-test and expert validation techniques. Feedback from pilot test participants and expert opinions on ambiguous terminology and missing items drove the development of items. Questions were reworded to improve readability, comprehension, and precision afterward. Originally, each question on the survey was written in English. The questionnaire was accompanied by a cover letter that outlined the research objectives, and a brief statement was included to explicate the meaning of corporate shared prosperity. This was done to ensure that the participants had a clear understanding of the fundamental concepts of shared prosperity.

3.3.5. Sample and data collection

The study employed a convenience sampling method to gather data from owners and managers of diverse manufacturing firms in Malaysia. The manufacturing firms list was drawn from the Federation of Malaysia Manufacturers (FMM) directory 2021. This approach was chosen due to its efficiency in terms of time and resource utilisation (Chauhan et al., Citation2018).

Before conducting the final survey, written ethics approval (Approval number: EA0832022) taken from The Research Ethics Committee (REC), Technology Transfer Office (TTO), Multimedia University, Malaysia. Informed written consent was taken from each respondent as every questionnaire has a section for respondent’s agreeableness to participate in the survey and this participation was voluntary and may refuse to withdraw at any time.

Between July and September 2022, a total of 455 questionnaires were distributed via electronic mail, with a Google form link attached. Subsequently, 229 respondents completed the questionnaires, resulting in a response rate of 50.32%. Among 229 responses 190 were manager and 39 were CEO. Majority of the companies were from electric industry (110) and food and beverage (60) and aged 11-15 years old (115).

4. Data analysis

4.1. Confirmatory composite analysis (CCA)

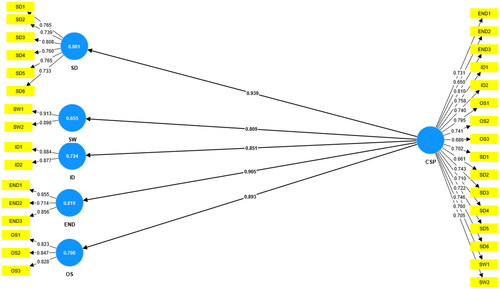

To model and assess composite concepts, confirmatory composite analysis is proposed as the preferred analytical tool (CCA; Schuberth et al., Citation2018; Henseler & Schuberth, Citation2020). The employment of CCA as a systematic and methodological approach is prevalent in the evaluation of model assessment within the context of PLS-SEM. To perform CCA, recent literature suggests a four-step procedure including 1) model specification, 2) model identification, 3) model estimation and 4) model assessment (Henseler & Schuberth, Citation2020; Schuberth et al., Citation2018). The first step deals with specification of the composite scale based on the emerged dimensions from the previous stage (two or more dimensions) of scale development and allow the dimensions to correlate freely. showed the emerged dimensions. During the identification step, two conditions should be established; i) fixing the variance or weight of each dimension and ii) including at least one other variable in the model and connecting it to the composite scale. showed the variance (VIF) of each dimensions and confirmed they are less than 3.30. The third step involves applying a composite-based estimator to estimate the parameters, such as partial least squares path modelling and generalized canonical correlation analysis. In accordance with our reflective measurement model, the indicators or items are subject to the influence of a latent variable known as CSP, as illustrated in . Following the procedure of CCA, the model is created by connecting the categorised items of corporate shared prosperity such as Equality and non-discrimination (END), Infrastructure Development (ID), Organizational stability (OS), Stakeholder Development (SD), Social wellbeing (SW) with the corporate shared prosperity construct. The for Pearson correlation coefficients for all corporate shared prosperity dimensions were significant at the p < 0.01, demonstrating nomological validity. The last step is to assess the composite construct.

The evaluation of the construct’s reliability may be conducted through the utilisation of Cronbach’s alpha (CA) and composite reliability. According to Hair et al. (Citation2019), composite reliability is generally regarded as a superior and more precise alternative to Cronbach’s alpha due to its weighting, which contrasts with the unweighted nature of Cronbach’s alpha. The data were analysed using SmartPLS (Version 4) software. The assessment of the measurement model was conducted through two distinct methods, namely the evaluation of convergent and discriminant validity. Additionally, nomological validity also was suggested to conduct (Spiro & Weitz, Citation1990) and shown to . The utilisation of Average Variance Extracted (AVE) is a common approach for evaluating the degree of convergent validity. provides a summary of the indicator loadings, composite reliability, and AVE.

Table 3. Nomological validity of the constructs.

Table 4. Convergent validity and reliability of the constructs.

As demonstrates, all items have met the minimum threshold of 0.708 for loadings. The assessment of internal consistency reliability was conducted through the utilisation of CA and composite reliability, adhering to the prescribed threshold of 0.70 as proposed by Hair et al. (Citation2021). The constructs’ composite reliability and CA values were found to surpass the 0.70 threshold. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that both CA and composite reliability measures cannot exceed a value of 0.95, as this would suggest that the indicators being assessed are measuring the same underlying construct. displays that the values of both CA and composite reliability are below 0.95.

This implies that the necessary level of diversity within each construct has been achieved. Finally, AVE was assessed following a minimum threshold of 0.50 to examine the convergent validity, as per the methodology outlined by Hair et al. (Citation2021). The AVE values of all five constructs exceed 0.50, thereby confirming their convergent validity.

Discriminant validity was examined for the measurement model. Discriminant validity was evaluated, as indicated in . The square root of the average of each construct exhibited a higher value compared to the inter-construct correlations that were associated with the construct correlation matrix.

Table 5. Discriminant validity of the constructs (Fornell-Larcker criterion).

The diagonal elements exhibited higher magnitudes compared to the remaining elements within their respective columns. indicates that the highest value in the infrastructure development column is 0.880.

The relative importance of the various first-order structures to the specified second-order construct is shown in . With p-values lower than 0.001, all of the path coefficients are statistically significant.

Table 6. Hypotheses and constructs evaluation result.

According to the findings, CSP is a second-order component composed of the following five dimensions (): stakeholder development; social well-being; infrastructure development; equality and non-discrimination; and organisational stability. All five dimensions, as proven by our empirical research, establish a second-order reflective construct, which means that all five dimensions must be present for CSP.

5. Discussion

Equality and non-discrimination had shown significant impact on corporate shared prosperity. Diverse teams are more effective at problem-solving and innovation. When people from different backgrounds collaborate, they bring a variety of perspectives and ideas, leading to more creative solutions (Ali et al., Citation2020). Harvard Business Review (Citation2013) indicates that diverse teams are more likely to out-innovate and outperform their non-diverse counterparts. Organizations that prioritize equality and non-discrimination build a positive corporate reputation. Customers and clients are increasingly conscious of social responsibility, and a positive reputation can enhance brand loyalty and market share. The Reputation Institute (Citation2017) found that companies with strong reputations outperform the market by 2.5% to 7%. This positive financial and non-financial performance leads to corporate shared prosperity.

Infrastructure development had shown significant impact on corporate shared prosperity. Del Giudice et al. (Citation2021) emphasize the importance of organizational infrastructure in supporting innovation and adaptability to changing market conditions. Organizations with modern and supportive infrastructure are more attractive to top talent. The availability of advanced technology and a positive working environment contributes to employee satisfaction and retention (Lima, Citation2020).

Organizational stability had shown significant impact on corporate shared prosperity. Organizational stability is closely tied to a positive workplace culture (Hossain et al., Citation2022). A stable and supportive culture fosters employee engagement, collaboration, and a sense of shared prosperity. The Harvard Business Review (Citation2018) emphasizes the link between a positive workplace culture and organizational success. Stable organizations are often better equipped to invest in innovation and adapt to changing market conditions. This adaptability contributes to sustained corporate prosperity. The MIT Sloan Management Review (Citation2015) explores the connection between organizational stability and innovation. Stable organizations are often better positioned to engage in sustainable practices and corporate social responsibility initiatives. These efforts contribute to shared prosperity by addressing environmental and social concerns.

Stakeholder development had shown significant impact on corporate shared prosperity. By actively engaging with stakeholders such as employees, customers, suppliers, and local communities, companies can build stronger relationships and trust, leading to various positive outcomes (Hossain et al., Citation2022). For instance, involving employees in decision-making processes can boost morale, productivity, and innovation, ultimately driving the company’s success. Collaborating with suppliers and local communities can create opportunities for mutual growth and development, fostering a more sustainable and prosperous business ecosystem. However, some argue that it is challenging to balance the diverse interests of stakeholders, leading to conflicts and inefficiencies (Bridoux & Stoelhorst, Citation2022). Constantly seeking consensus among stakeholders can slow down decision-making processes, hindering the company’s ability to respond quickly to market changes and competitive pressures (Obrenovic et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, some stakeholders may have conflicting interests, making it difficult for companies to satisfy everyone simultaneously (Hossain et al., Citation2022). In such cases, prioritizing certain stakeholders over others may lead to resentment and distrust, undermining the company’s reputation and long-term viability.

Social wellbeing had shown significant impact on corporate shared prosperity. Organizations that invest in health and well-being programs contribute to social well-being among employees. These programs can lead to reduced absenteeism, improved morale, and a healthier workforce. Social well-being is enhanced through diversity and inclusion initiatives. Organizations that promote diversity create an inclusive culture that values and respects differences among employees, contributing to a positive work environment (Hossain et al., Citation2022). Social well-being is connected to employee engagement, which can be fostered through CSR initiatives. Organizations that engage in socially responsible practices contribute to a sense of purpose and shared prosperity among employees.

6. Conclusion

This research represents a pioneering effort in the field of sustainability studies, as it endeavours to formulate and implement a crucial construct, namely, corporate shared prosperity. Our study involved a critical analysis and expansion of previous research through the introduction of a model consisting of five distinct dimensions (stakeholder development; social well-being; infrastructure development; equality and non-discrimination; and organisational stability). The dimensions derived from systematic literature review, focus group expert’s verification and statistical analysis ensured validity, reliability and significance with corporate shared prosperity.

6.1. Theoretical contributions

Upon conducting a thorough examination of existing literature, it was discovered that there is currently no established survey based measurement for evaluating corporate shared prosperity, despite its conceptualization. The present research endeavoured to construct and authenticate a metric assessing corporate shared prosperity within the framework of an organisation, as perceived by managers and owners. Previous research on shared prosperity in corporations has predominantly centred on the national economic context (Ofori et al., Citation2022; Ciaschi et al., Citation2020), with limited attention given to the organisational context. This study represents a novel approach to investigating corporate shared prosperity, as it adopts an organisational theoretical framework and gathers perspectives from both managers and owners within corporations. This research endeavour represents the inaugural effort to examine the concept of corporate shared prosperity within the context of business enterprises and to scrutinise the perceptions of managers and owners regarding this phenomenon within their respective organisations.

The findings of this study have validated that the achievement of shared prosperity within a corporate setting is reliant upon five distinct dimensions, which have been operationalized through 16 reflective indicators, as presented in . The aforementioned conceptual advancement has facilitated an enhanced comprehension and quantification of corporate shared prosperity, while also confirming that such prosperity cannot be accurately gauged through uni-dimensional or solitary measures. This manuscript presents a unique contribution to the existing body of literature on sustainability and the development of measurement scales.

The present study has extended the empirical conceptualization by developing a scale for measuring this construct and applicability of stakeholder theory in diverse context. The validation of corporate shared prosperity within an organisation is considered a manifestation of various aspects, including stakeholder development, social wellbeing, infrastructure development, equality, and non-discrimination, as well as organisational stability. These scale development foster further investigation on corporate shared prosperity dimensions which will be beneficial for diverse stakeholders.

6.2. Practical implications

While prior research on corporate shared prosperity has concentrated on topics like shared prosperity in Sub-Saharan Africa (Ofori et al., Citation2022) and shared prosperity and inequality in Brazil (Ciaschi et al., Citation2020), recent work has shifted its focus to more methodological inquiries into Shared Prosperity (Atamanov et al., Citation2016) and policy papers on its concepts and implementation (Ferreira et al., Citation2018). In this study, we created a corporate shared prosperity scale to help businesses gauge their stakeholders’ support for and resistance to their efforts to become more sustainable in the following areas: stakeholder development, social wellbeing, infrastructure development, equality and non-discrimination, and organisational stability enablers.

In brief, this research has made noteworthy advancements in the implementation of corporate shared prosperity within organisational settings. The present study describes a research endeavour aimed at developing a scale, utilising confirmatory composite analyses, that is specifically tailored to measure organisational success in promoting shared prosperity among corporate entities. This approach represents a unique contribution to the field of scale development.

6.3. Limitations and future research areas

The present investigation is subject to two constraints. Initially, the data was primarily sourced from CEOs and managers of ISO14001-certified manufacturing organisations in Malaysia. Conducting further research in diverse geographical regions could potentially enhance comprehension regarding the potential variances in the perception of corporate shared prosperity within organisations across various cultures or subcultures.

The inclusion of a diverse range of sectors, such as electric components, food and beverage, steel textile, paper products, rubber and plastic products, and chemical products, enhances the representativeness of the study. The present survey study was predicated on the self-reported data of CEOs and managers. The survey instrument refrained from soliciting any personally identifiable information from the participants to safeguard their anonymity and mitigate the potential for social desirability bias.

The approach we have employed is in alignment with the perspective of scholars who suggest that the theoretical significance of constructs such as focus groups, expert panel, and literature mapping can be utilised to create a novel measurement scale when an existing one is not available.

Additional research is required to authenticate the scale through the utilisation of data from diverse cultures, industries, and nations on a broader scale. It is recommended that researchers explore how employees perceive each of the dimensions of CSP concerning factors such as stakeholder development, social wellbeing, infrastructure development, equality and non-discrimination, and organisational stability, both independently and in conjunction with one another. This will enable the theoretical advancement of CSP and its resultant effects.

Authors’ contributions

Conceptualization: Mohammad Imtiaz Hossain, Boon Heng Teh, and Lee-Lee Chong; Methodology: Tze San Ong, Yasmin Jamadar, Software: Tze San Ong, Yasmin Jamadar; Formal analysis: Mohammad Imtiaz Hossain and Mosab I. Tabash.; Validation: Mosab I. Tabash.; Data curation: Tze San Ong.; Writing-original draft preparation: Mohammad Imtiaz Hossain, Boon Heng Teh, and Lee-Lee Chong; Review and editing: Mohammad Imtiaz Hossain, Mosab I. Tabash, Tze San Ong, and Yasmin Jamadar All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data is available based on a responsible request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mohammad Imtiaz Hossain

Mohammad Imtiaz Hossain is a PhD candidate at Multimedia University, Malaysia. He pursued MSc in Business Economics from the School of Business and Economics, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Malaysia (AACSB & EQUIS accredited). His research interests include sustainability, technology adoption, entrepreneurship, ambidexterity, and innovation. He has published numerous scholarly articles in ABS, Web of Science, ABDC, Scopus, ERA indexed journals and chapters in book. Additionally, he is also serving as a reviewer for some prominent journals. He has presented papers in several international conferences and clinched the ‘Best Paper Award’ and ‘Best Presenter Award’. He can be reached at [email protected]

Boon Heng Teh

Boon Heng Teh is a Senior Lecturer at the Faculty of Management, Multimedia University, Malaysia. His research interests include finance, green accounting, and audit. His research work has been published in social science and management journals, for example, Asian Social Science and Journal Pengurusan. He is also the recipient of several research awards including the fundamental research grant scheme (FRGS) awarded by the Government of Malaysia. He can be reached at [email protected]

Lee-Lee Chong

Lee-Lee Chong is an Associate Professor from the Asia Pacific University of Technology & Innovation and has a PhD in Financial Economics. She has published in international refereed journals such as the Journal of Behavioural Finance, The Journal of Risk Finance, Managerial Finance, Studies in Economics and Finance, Technology in Society and many more. She also has vast teaching experience in both undergraduate and postgraduate levels. Her research interests include behavioural finance and investment, fintech and sustainability. She can be reached at [email protected]

Tze San Ong

Tze San Ong is a Full Professor of the School of Business and Economics at Universiti Putra Malaysia. She earned her PhD from the University of Leeds, UK in 2005. Her research has been published in various prestigious journals, such as the Journal of Cleaner Production, Business Strategy & the Environment, the International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, the Journal of Intellectual Capital, Resources, Conservation & Recycling, Ecosystem Health and Sustainability and many more. To date, she has published more than 100 academic articles and chapters in book both locally and internationally. Her research interests include corporate sustainability, corporate performance measurement system, corporate governance, management accounting and carbon accounting. She can be reached at [email protected]

Mosab I. Tabash

Mosab I. Tabash is currently working as MBA Director at the College of Business, Al Ain University, UAE. He obtained his PhD in Finance from the Faculty of Management Studies, Delhi, India. His research interests include Islamic banking, monetary policies, financial performance, risk management and interdisciplinary studies. He is an active researcher and has many editorial positions at many journals of repute. He can be reached at [email protected]

Yasmin Jamadar

Yasmin Jamadar is currently serving as an Assistant Professor at the BRAC Business School (BBS), BRAC University (BRACU). She obtained her Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in Finance from the School of Business and Economics, Universiti Putra Malaysia (UP M) [AACSB & EQUIS accredited]. Her research areas include corporate finance, corporate governance, accounting, sustainability, Insider trading, and earnings management. Her publications have appeared in various international refereed journals indexed in the ABS, WoS, ABDC and Scopus. Additionally, she is also serving as a reviewer for some prominent journals. She can be reached at [email protected]

References

- Ali, A., Wang, H., & Johnson, R. E. (2020). Empirical analysis of shared leadership promotion and team creativity: An adaptive leadership perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 41(5), 405–423. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2437

- Al-Omoush, K. S., Ribeiro-Navarrete, S., Lassala, C., & Skare, M. (2022). Networking and knowledge creation: Social capital and collaborative innovation in responding to the COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Innovation & Knowledge, 7(2), 100181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2022.100181

- Al-Taweel, I. R. (2021). Impact of high-performance work practices in human resource management of health dispensaries in Qassim Region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, towards organizational resilience and productivity. Business Process Management Journal, 27(7), 2088–2109. https://doi.org/10.1108/BPMJ-11-2020-0498

- Atamanov, A., Wieser, C., Uematsu, H., Yoshida, N., Nguyen, M., Azevedo, J. P., & Dewina, R. (2016). Robustness of shared prosperity estimates: How different methodological choices matter. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, 7611, 1–26.

- Azapagic, A. (2003). Systems approach to corporate sustainability: A general management framework. Process Safety and Environmental Protection, 81(5), 303–316. https://doi.org/10.1205/095758203770224342

- Barakat, L., Taylor, P., Griffiths, N., & Miles, S. (2021). A reputation-based framework for honest provenance reporting. ACM Transactions on Internet Technology, 22(4), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1145/3507908

- Basu, K. (2013). Shared prosperity and the mitigation of poverty: In practice and in precept . World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, 6700, 1–37.

- Bridoux, F., & Stoelhorst, J. W. (2022). Stakeholder governance: Solving the collective action problems in joint value creation. Academy of Management Review, 47(2), 214–236. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2019.0441

- Carosi, A. (2016). Do local causations matter? The effect of firm location on the relations of ROE, R&D, and firm size with Market-To-Book. Journal of Corporate Finance, 41, 388–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2016.10.008

- Chauhan, S., Gupta, P., & Jaiswal, M. (2018). Factors inhibiting the internet adoption by base of the pyramid in India. Digital Policy, Regulation and Governance, 20(4), 323–336. https://doi.org/10.1108/DPRG-01-2018-0001

- Churchill, G. A.Jr, (1979). A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 16(1), 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224377901600110

- Ciaschi, M., Damasceno Costa, R., Rubião, R. M., Paffhausen, A. L., & Sousa, L. D. (2020). A reversal in shared prosperity in Brazil. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/8165ae6d-a191-5132-9747-9ef007a2208b

- Collins, H., & Saliba, C. (2020). Connecting people to purpose builds a sustainable business model at Bark House. Global Business and Organizational Excellence, 39(3), 29–37. https://doi.org/10.1002/joe.21992

- Coulibaly, A., & Yogo, U. T. (2020). The path to shared prosperity: Leveraging financial services outreach to create decent jobs in developing countries. Economic Modelling, 87, 131–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2019.07.013

- D’amato, A., Henderson, S., & Florence, S. (2009). Corporate social responsibility and sustainable business: A Guide to Leadership Tasks and Functions (pp. 1–102). Greensboro, North Carolina, USA: Center for Creative Leadership Press.

- Dang, H. A. H., & Lanjouw, P. F. (2016). Toward a new definition of shared prosperity: A dynamic perspective from three countries (pp. 151–171). Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Danso, A., Adomako, S., Amankwah‐Amoah, J., Owusu‐Agyei, S., & Konadu, R. (2019). Environmental sustainability orientation, competitive strategy and financial performance. Business Strategy and the Environment, 28(5), 885–895. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2291

- Del Giudice, M., Scuotto, V., Papa, A., Tarba, S. Y., Bresciani, S., & Warkentin, M. (2021). A self‐tuning model for smart manufacturing SMEs: Effects on digital innovation. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 38(1), 68–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12560

- Deloitte University Press. (2017). Tech trends 2017: The kinetic enterprise. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/focus/tech-trends.html

- DOSH. (2022). Department of Occupational Safety and Health. https://www.dosh.gov.my/index.php/international-policy-and-research-development

- DOSM. (2022). Department of Occupational Safety and Health. https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php?r=column/ctwoByCat&parent_id=89&menu_id=SjgwNXdiM0JlT3Q2TDBlWXdKdUVldz09

- Dutz, M. A. (2016). Catch-up innovation and shared prosperity. In: Haar, J. & Ernst, R. (eds.), Innovation in Emerging Markets. International Political Economy Series (pp. 253–270). London: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137480293_14

- Earth. (2022). Global sustainability index 2022. https://earth.org/global-sustainability/

- Eisenhardt, K. M., & Graebner, M. E. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25–32. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.24160888

- Environmental Performance Index (. (2022). Yale Center for Environmental Law & Policy. https://epi.yale.edu/epi-results/2022/component/epi

- Ferreira, F. H., Galasso, E., & Negre, M. (2018). Shared prosperity: Concepts, data, and some policy examples . World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 8451.

- Fong, T. P. W., Sze, A. K. W., & Ho, E. H. C. (2022). Do long-term institutional investors contribute to financial stability?–Evidence from equity investment in Hong Kong and international markets. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 77, 101521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2022.101521

- Freeman, R. E., Harrison, J. S., Wicks, A. C., Parmar, B. L., & De Colle, S. (2010). Stakeholder theory: The state of the art. Cambridge University Press.

- Gaertner, K., & Ishikawa, E. (2014). Shared prosperity through inclusive business: How successful companies reach the base of the pyramid. International Finance Corporation. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/20594

- Gallup. (2016). State of the American Workplace. https://www.gallup.com/workplace/238085/state-american-workplace-report-2017.aspx

- Gatti, R., Morgandi, M., Grun, R., Brodmann, S., Angel-Urdinola, D., Moreno, J. M., … Lorenzo, E. M. (2013). Jobs for shared prosperity: Time for action in the Middle East and North Africa. World Bank Publications.

- Global Reporting Initiative. (2016). GRI Standards. https://www.globalreporting.org/standards

- Hahn, R., & Kühnen, M. (2013). Determinants of sustainability reporting: A review of results, trends, theory, and opportunities in an expanding field of research. Journal of Cleaner Production, 59, 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.07.005

- Hahn, T., & Figge, F. (2011). Beyond the bounded instrumentality in current corporate sustainability research: Toward an inclusive notion of profitability. Journal of Business Ethics, 104(3), 325–345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0911-0

- Hair, J. F., Jr, Howard, M. C., & Nitzl, C. (2020). Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. Journal of Business Research, 109, 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.11.069

- Hair, J. F., Jr, Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2021). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage Publications.

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Harvard Business Review. (2013). How Diversity Can Drive Innovation. https://hbr.org/2013/12/how-diversity-can-drive-innovation

- Harvard Business Review. (2018). The Comprehensive Business Case for Sustainability. https://hbr.org/2018/02/the-comprehensive-business-case-for-sustainability

- Henseler, J., & Schuberth, F. (2020). Using confirmatory composite analysis to assess emergent variables in business research. Journal of Business Research, 120, 147–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.07.026

- Hossain, M. I. (2020). Moderating effect of green technology adoption on the stakeholder influence and environmental sustainability practices in Bangladesh textile small and medium enterprises [MSc thesis]. Universiti Putra Malaysia.

- Hossain, M. I., Kumar, J., Islam, M. T., & Valeri, M. (2023). The interplay among paradoxical leadership, industry 4.0 technologies, organisational ambidexterity, strategic flexibility and corporate sustainable performance in manufacturing SMEs of Malaysia. European Business Review, Ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-04-2023-0109

- Hossain, M. I., Limon, N., Amin, M. T., & Asheq, A. S. (2018). Work life balance trends: A study on Malaysian GenerationY bankers. IOSR Journal of Business and Management, 20(9), 01–09.

- Hossain, M. I., Ong, T. S., Tabash, M. I., & Teh, B. H. (2022). The panorama of corporate environmental sustainability and green values: Evidence of Bangladesh. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 26(1), 1033–1059. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-022-02748-y

- Hossain, M. I., Teh, B. H., Chong, L. L., Ong, T. S., & Islam, M. T. (2022). Green human resource management, top management commitment, green culture, and green performance of Malaysian palm oil companies. International Journal of Technology, 13(5), 1106–1114. https://doi.org/10.14716/ijtech.v13i5.5818

- Hossain, M. I., Teh, B. H., Tabash, M. I., Alam, M. N., & San Ong, T. (2024). Paradoxes on sustainable performance in Dhaka’s enterprising community: A moderated-mediation evidence from textile manufacturing SMEs. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 18(2), 145–173. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-08-2022-0119

- Hossain, M. I., Teh, B. H., Tabash, M. I., Chong, L. L., & Ong, T. S. (2024). Unpacking the role of green smart technologies adoption, green ambidextrous leadership, and green innovation behaviour on green innovation performance in Malaysian manufacturing companies. FIIB Business Review, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/23197145231225335

- Jolliffe, D. (2014). A measured approach to ending poverty and boosting shared prosperity: concepts, data, and the twin goals. World Bank Publications.

- Karia, N., & Davadas Michael, R. C. (2022). Environmental practices that have positive impacts on social performance: An empirical study of Malaysian firms. Sustainability, 14(7), 4032. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14074032

- Kelly, N. J. & Morgan, J. (2022). Hurdles to shared prosperity: Congress, parties, and the national policy process in an era of inequality. In: Hacker, J., Hertel-Fernandez, A., Pierson, P., & Thelen Hudson, K. (Eds). The American Political Economy. Politics, Markets, and Power (pp. 51–75). New York, USA: Cambridge University Press.

- Klinova, K., & Korinek, A. (2021, July). AI and shared prosperity [Paper presentation]. Proceedings of the 2021 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society (pp. 645–651). https://doi.org/10.1145/3461702.3462619

- Kozmetsky, G. (1997). Synergy for the 21st Century: Between unstructured problems and management planning controls. https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/18557

- Kozmetsky, G., & Williams, F. (2003). New Wealth: Commercialization of science and technology for business and economic development. Praeger Publishers.

- Kozmetsky, G., Jackson, M. L., & Boyd, A. M. (2001). The EnterTech Project: Changing learning and lives. http://www.ic2.org/main.php?a=3&s=432002-05-15

- Laszlo, C., & Brown, J. S. (2014). Flourishing enterprise: The new spirit of business. Stanford University Press.

- Laszlo, C., & Zhexembayeva, N. (2011). Embedded sustainability: A strategy for market leaders. The European Financial Review, 15, 37–49.

- Latan, H., Jabbour, C. J. C., de Sousa Jabbour, A. B. L., Wamba, S. F., & Shahbaz, M. (2018). Effects of environmental strategy, environmental uncertainty and top management’s commitment on corporate environmental performance: The role of environmental management accounting. Journal of Cleaner Production, 180, 297–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.01.106

- Leah, J. S. (2017). Positive impact: Factors driving business leaders toward shared prosperity, greater purpose and human wellbeing. Case Western Reserve University.

- Leah, J. S. (2024). Translating purpose and mindset into positive impact through shared vision, compassion, and energy—A comparative study of seven organizations. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1251256. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1251256

- Lima, M. (2020). Smarter organizations: Insights from a smart city hybrid framework. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 16(4), 1281–1300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-020-00690-x

- Mahajan, R., Lim, W. M., Sareen, M., Kumar, S., & Panwar, R. (2023). Stakeholder theory. Journal of Business Research, 166, 114104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.114104

- Marshall, R. (1998). Back to shared prosperity. Discovery magazine. University of Texas.

- Mayer, C. (2023). Reflections on corporate purpose and performance. European Management Review, 20(4), 719–724. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12626

- McKinsey & Company. (2015). Why Diversity Matters. https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/why-diversity-matters

- McKinsey Global Institute. (2012). The social economy: Unlocking value and productivity through social technologies. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/technology-media-and-telecommunications/our-insights/the-social-economy

- Memon, M. A., Ting, H., Cheah, J. H., Thurasamy, R., Chuah, F., & Cham, T. H. (2020). Sample size for survey research: Review and recommendations. Journal of Applied Structural Equation Modeling, 4(2), i–xx. https://doi.org/10.47263/JASEM.4(2)01

- Mhlanga, D., & Ndhlovu, E. (2023). Social inclusion interventions for Africa towards sustainable development and shared prosperity. In Economic inclusion in post-independence Africa: An inclusive approach to economic development (pp. 59–80). Springer Nature Switzerland.

- Ministry of Economic affairs. (2019). Shared prosperity vision 2030. https://www.pmo.gov.my/2019/10/shared-prosperity-vision-2030-2/

- Ministry of Economy. (2019). Twelfth Malaysian plan 2019. https://rmke12.epu.gov.my/en

- Mintchev, N. I. K. O. L. A. Y., Baumann, H. A. N. N. A., Moore, H., Rigon, A. N. D. R. E. A., & Dabaj, J. O. A. N. A. (2019). Towards a shared prosperity: Co-designing solutions in Lebanon’s spaces of displacement. Journal of the British Academy, 7(S2), 109–135.

- MIT Sloan Management Review. (2015). Why stable teams may be the secret to innovation. https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/why-stable-teams-may-be-the-secret-to-innovation/

- Narayan, A., Saavedra-Chanduvi, J., & Tiwari, S. (2013). Shared prosperity: Links to growth, inequality and inequality of opportunity . World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 6649.

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. (2018). Framework for improving critical infrastructure cybersecurity. https://www.nist.gov/cyberframework

- Obrenovic, B., Du, J., Godinic, D., Tsoy, D., Khan, M. A. S., & Jakhongirov, I. (2020). Sustaining enterprise operations and productivity during the COVID-19 pandemic: Enterprise Effectiveness and Sustainability Model. Sustainability, 12(15), 5981. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12155981

- OECD. (2022). Employee compensation by activity. https://data.oecd.org/earnwage/employee-compensation-by-activity.htm

- Ofori, I. K., Cantah, W. G., Afful, B., Jr,., & Hossain, S. (2022). Towards shared prosperity in sub‐Saharan Africa: How does the effect of economic integration compare to social equity policies? African Development Review, 34(1), 97–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8268.12614

- Oliveira-Dias, D., Kneipp, J. M., Bichueti, R. S., & Gomes, C. M. (2022). Fostering business model innovation for sustainability: A dynamic capabilities perspective. Management Decision, 60(13), 105–129. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-05-2021-0590

- Pandey, P. C. (2021). Rebooting business innovations and sustainability practices in the digital age: Agenda of action for shared prosperity. Review of Professional Management-A Journal of New Delhi Institute of Management, 19(2), 16–29.

- Petera, P., Wagner, J., & Pakšiová, R. (2021). The influence of environmental strategy, environmental reporting and environmental management control system on environmental and economic performance. Energies, 14(15), 4637. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14154637

- Phillips, F. (2005). Toward an intellectual and theoretical foundation for ‘Shared Prosperity’. Systemic Practice and Action Research, 18(6), 547–568. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11213-005-9466-2

- Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Ali, F., Mikulić, J., & Dogan, S. (2023). Reflective and composite scales in tourism and hospitality research: Revising the scale development procedure. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 35(2), 589–601. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-02-2022-0255

- Reputation Institute. (2017). The business impact of reputation. https://www.reputationinstitute.com/research/The-Business-Impact-of-Reputation