Abstract

This study examines the influence of entrepreneurial role models on an individual’s decision to become self-employed and how age moderates this relationship. We use a dataset of 8000 individuals from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM 2013–2017) and apply logit regressions to assess this relationship. The findings confirm a significantly positive effect of entrepreneurial role models on the decision to be entrepreneurs among Vietnamese adults. Furthermore, the positive influence of entrepreneurial role models on self-employment is weaker for older individuals than for younger generations. Results provide implications for policies and practices to nurture entrepreneurship.

Reviewing Editor:

1. Introduction

Entrepreneurship is a vital driver of nations’ wealth (Schumpeter, Citation1934). Yet, why are people willing to engage in entrepreneurial activities? Among the various factors is the influence of role models (Fritsch & Rusakova, Citation2012; Wyrwich et al., Citation2016). An entrepreneurial role model is an individual who sets examples to be followed by others and motivates others towards an entrepreneurship career (Bosma et al., Citation2012). Entrepreneurial role models may provide visual assistance (e.g. financing, labour, network, guidance and information) and invisible assistance (e.g. self-efficacy, encouragement, cheering or motivation) (Wyrwich et al., Citation2016). As a crucial social capital, evidence has shown that entrepreneurial role models enhance individual entrepreneurial attitudes and intentions, which in turn result in entrepreneurial practices (Fritsch & Rusakova, Citation2012; Wyrwich et al., Citation2016; Nowinski & Haddoud, Citation2019).

However, in transition economies, the lingering effects of the previous centrally planned regime, which discouraged entrepreneurship, may lead to a persistent fear of failure among individuals even with a positive entrepreneurial role model effect (Blanchflower & Freeman, Citation1997; Corneo, Citation2001; Sztompka, Citation1996). This negative effect might be stronger with the older generation, who directly suffer from the regime. Wyrwich et al. (Citation2016) note that older people from East Germany have a higher level of failure avoidance than those in West Germany. Nonetheless, there is no difference among young people in East Germany if they have known about at least one entrepreneur. This finding can be explained by the low perception of entrepreneurship in the formerly socialist environment of East Germany, accompanied by the low effects of role models (Wyrwich et al., Citation2016). Also, the positive impact of entrepreneurial role models on entrepreneurship activities in transition economies is weaker for older individuals than younger ones (Lafuente & Vaillant, Citation2013; Róbert & Bukodi, Citation2000). In sum, there is a growing assumption that age has a potential moderation effect on the relationship between entrepreneurial role models and entrepreneurship in a transitional economy.

With the ‘Doi Moi’ policy, Vietnam has transformed into a market economy since 1986, based on the ‘socialist-oriented market economy’ (Tran, Citation2019). Thus, Vietnam provides an interesting context for investigating this issue. Are young Vietnamese people born and living in the market economy willing to engage in entrepreneurship? Does an entrepreneurial role model impact their entrepreneurial behaviours? Does age moderate the impact of role models on entrepreneurship in the Vietnam context? Answering these questions may provide useful hints about fostering entrepreneurship in these transition economies.

This study examines the influence of entrepreneurial role models on self-employment and the role of age in this relationship in the context of a transitional economy. We use logit regressions on a dataset of 8000 observations extracted from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) from 2013 to 2017. The study finds a significant and positive effect of entrepreneurial role models on becoming entrepreneurs among Vietnamese adults. In other words, individuals who personally know an entrepreneur are more willing to start a firm than those without this social contact. Another interesting result is that older age groups are more likely to engage in entrepreneurship activities than younger age groups. However, the positive impact of entrepreneurial role models on self-employment is weaker for older individuals than for younger generations.

This study broadens the understanding of the factors influencing entrepreneurship by offering empirical evidence to argue for the impacts of entrepreneurial role models on an individual’s decision to become an entrepreneur in transition markets. In this specific context, building upon relevant literature from Wyrwich et al. (Citation2016) and Lafuente and Vaillant (Citation2013), our study argues that elderly individuals may exhibit a lower likelihood to engage in entrepreneurial activities compared to younger generations partly because the seniors’ forbidden to acquire expertise from others entrepreneurs as role models in the former socialist era – a time where entrepreneurship and private firms were banned.

The subsequent section provides an overview of the literature and details relevant hypotheses to the research question. This is followed by the methodology section, describing the dataset and measurement. Part 4 presents major findings before the conclusion in Part 5.

2. Literature review and hypotheses development

2.1. Entrepreneurial role models and entrepreneurial activities

Role model individuals refer to those whose presence has an impact on his/her cognition, attitude, and behaviour (Abbasianchavari & Moritz, Citation2021; Bosma et al., Citation2012). The references group to an individual includes related models like parents, peers, educators, mentors, successful people models and other unrelated models. Such people provide not only physical assistance, such as financial, information or employees but also support mental software like encouragement, cheering, or motivation for potential entrepreneurs (Nicholls-Nixon et al., Citation2024; Smallbone & Welter, Citation2001; Wyrwich et al., Citation2016). There have been well-documented empirical studies that indicate how social networks influence entrepreneurship (Krueger et al., Citation2000; Osabohien et al., Citation2024; Sobhan & Hassan, Citation2024; Wyrwich, Citation2015). Prior findings show that individuals with parental self-employed are positively associated with their willingness to become entrepreneurs (Davidsson & Honig, Citation2003; Van Auken et al., Citation2006). People tend to learn and imitate the lifestyle of people they admire. Such influencers may provide positive or negative references compared to social standards.

Yitshaki (Citation2024) mentions that role models, particularly mentors, help identify new opportunities, assess the viability and feasibility of their project and learn how to exploit opportunities. Hence, role models are associated with entrepreneurial-role-identity change (Ozgen & Baron, Citation2007). Role models are also crucial sources of advice. Besides, experience-based advice includes self-sufficient advice, reflexive feedback and cognitive framing, and emotional and psychological advice.

Family bonds, especially parents, are special influencers in entrepreneurship intention. This is the most established relationship to an individual. Long-term contact provides the most references on cognition about entrepreneurial tasks, decision-making style, business interaction, income and outcome of entrepreneurial being. People whose parents are entrepreneurs tend to have a positive attitude towards entrepreneurship and receive greater support to pursue business as a career. Joensuu-Salo et al. (Citation2021), using data in Finland with logistic regression, has identified that entrepreneurship competence is the mediation to business takeover intention. The study also finds that parental role models and age impact takeover intention.

On the other hand, other studies indicate that the relationship between role models and propensity to be entrepreneurs is negative (Fritsch & Rusakova, Citation2012; Wyrwich et al., Citation2016) or even insignificant (Wyrwich, Citation2013). Tkachev and Kolvereid (Citation1999) find that gender and family background do not have any links to entrepreneurial intention among Russian students. In addition, the result of a study, Fritsch and Rusakova (Citation2012) conclude that among East Germans whose entrepreneurial decisions do not relate to their parental self-employed. These reasons are explained by anti-capitalist indoctrination; thereby, entrepreneurs’ values are difficult to transfer to their children.

2.2. Hypotheses development

2.2.1. Role models and entrepreneurial decisions in transition economies

Role models have been increasingly stressed as key enablers of individual entrepreneurial intentions and their consequent behaviours. The role models here can be understood as having parental self-employment, prior entrepreneurs, similar models and peers, educators, mentors or state officials (Fritsch & Rusakova, Citation2012; Laspita et al., Citation2012). Research on the entrepreneurial role model effect dates back to the last 40 years and mainly draws on the social learning theory (Bandura & Walters, Citation1977). That said, individuals can learn by observing, modelling and imitating others’ behaviours. In addition, the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) (Ajzen, Citation1991) has been widely applied to entrepreneurship research, and it predicts intentions based on three key predictors: attitude towards entrepreneurship, subjective norms, and perceived behavioural control. The theory and the empirical results indicate that subjective norms, which represent external environmental factors (e.g. family and friends’ expectations), are believed to influence individuals’ entrepreneurial intentions (Adam-Müller et al., Citation2024; Busenitz et al., Citation2000; Krueger & Carsrud, Citation1993).

Empirical research has revealed a positive relationship between subjective norms and entrepreneurship intentions (Kolvereid, Citation1996; Tkachev & Kolvereid, Citation1999). Other prior studies investigate the influence of role models (e.g. parental self-employment, knowing entrepreneurs or university professors) on students’ views on entrepreneurship and find a significant association between these mechanism effects (Volkmann & Tokarski, Citation2009).

Recent evidence confirms the positive effect of entrepreneurial role models in developed countries (Liñán & Fayolle, Citation2015). The entrepreneurial role model triggers entrepreneurial activities either as a source of inspiration or as a reference for experience to discover and act upon any entrepreneurial opportunities (Criaco et al., Citation2017). Bosma et al. (Citation2012), for instance, found that half of Dutch nascent entrepreneurs had a role model when starting a company, and they would not have founded their venture without the model’s inspiration. Similarly, in the context of Spanish students, Pablo-Lerchundi et al. (Citation2015) claimed that the business experience of parental role models is successfully passed on to their children, who are more likely to become entrepreneurs.

Sobhan and Hassan (Citation2024) reveal that in emerging countries like Bangladesh, female entrepreneurship is positively associated with family roles and education but negatively or even insignificantly associated with financial support and social capital. Other previous studies indicate that individuals who have contact with entrepreneurs have a higher willingness to start a new firm than those without entrepreneurs (Krueger et al., Citation2000). Those potential entrepreneurs may explore entrepreneurial opportunities and experience having entrepreneurial role models (Ingole & Sohani, Citation2024; Snihur & Clarysse, Citation2022; Vaillant & Lafuente, Citation2007; Wagner & Sternberg, Citation2004). That helps them to increase their self-confidence and reduce their fear of failure in starting a new venture (Aidis et al., Citation2008).

Aidis et al. (Citation2008) state that the institution in transitioning economies acts as a disincentive to entrepreneurship and that business information is scarce. Consequently, the ability to recognise and exploit business opportunities is limited. However, the existence of other entrepreneurs can serve as a significant channel for this recognition and exploitation.

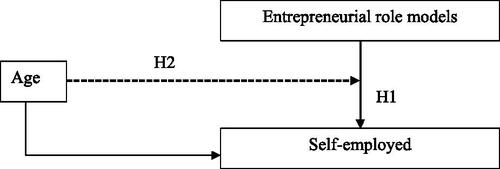

Considering the aim of testing the effect of role models in transition countries, we formulate the first hypothesis as follows:

H1. Individuals who know an entrepreneur are more likely to be self-employed.

2.2.2. Role models, entrepreneurial decisions and the moderation of age in transition economies

Entrepreneurship is a phenomenon that is influenced by a number of contextual factors (Welter, Citation2011). The disparities in regional entrepreneurial activity are further elucidated by area-specific conditions, including industrial structure, technological policies and entrepreneurial culture (Andrade-Rojas et al., Citation2024; Wyrwich, Citation2012). The shift of the economic system in emerging nations has been postulated to significantly influence human attitudes and behaviours towards entrepreneurship (Cerviño et al., Citation2024; Smallbone & Welter, Citation2001). Individuals’ entrepreneurial inspiration and motivation can be developed in regions with high social acceptance of entrepreneurship through the establishment of entrepreneurial social networks, the implementation of entrepreneurship support programmes and the enactment of policies (e.g. financing, training and educational entrepreneurship programmes) (Fritsch & Wyrwich, Citation2014). A high-approval entrepreneurship environment is one in which social attitudes about entrepreneurship are positive and in which role models exert a positive effect on individuals’ entrepreneurial intentions (Andersson & Koster, Citation2011; Wyrwich et al., Citation2016).

Conversely, in an environment with low approval of entrepreneurship, the impact of entrepreneurial role models on individuals’ entrepreneurial activity is minimal (Wyrwich, Citation2013; Wyrwich et al., Citation2019). In their analysis of the effect of role models (i.e. knowing other entrepreneurs) on individuals’ perception of entrepreneurship among German people, Wyrwich et al. (Citation2016) employ an extended sender-receiver model. Their findings reveal that older East Germans who were born before 1960 exhibited an increasing fear of failure in business despite knowing other entrepreneurs. Wyrwich et al. (Citation2016) state that in this context, societal perceptions of entrepreneurship are low, accompanied by a low effect of role models.

Furthermore, research conducted by Bauernschuster et al. (Citation2012), Runst (Citation2013) and Wyrwich (Citation2013) has demonstrated that individuals residing in socialist environments tend to exhibit a lower degree of entrepreneurial behaviour, thereby suggesting a correlation between increased longevity and reduced engagement in entrepreneurship. This is due to the fact that those who were subjected to communism exhibited a diminished level of locus of control, autonomy, and mastery ideals. These individuals possess knowledge and expertise that is no longer relevant to self-employment (Schwartz & Bardi, Citation1997; Alesina & Fuchs-Schündeln, Citation2007; Sztompka, Citation1996). Wyrwich (Citation2013) finds a weak positive correlation between work experience and entrepreneurship among older people originating in East Germany. Moreover, the older generation demonstrates an increased concern about failure, even when they receive knowledge and experience from other entrepreneurs (Wyrwich et al., Citation2016).

In this state-controlled model, state-owned companies (SOEs) held a prominent position. The government is granted authority to oversee, regulate, and possess ownership of all sectors of the economy (Andreff, Citation1993; Fisch et al., Citation2021). Since 1986, Vietnam has undergone a significant economic transformation by transitioning from a state-controlled economy to a market economy with the implementation of the ‘Doi Moi’. Subsequently, individuals have been granted the freedom to engage in entrepreneurial endeavours. Nevertheless, Vietnam has compelled State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) to adopt market-oriented practices as a way to enhance their efficacy and secure their longevity (Tran, Citation2019). The growth of entrepreneurial endeavours and private enterprises in Vietnam has truly undergone an impressive progression since the year 2000, coinciding with the implementation of the ‘Enterprise Law’ (Tran, Citation2019). Presently, Vietnam claims itself as a ‘socialist-oriented market economy.’

Given the prior evidence and unique historical context in Vietnam, we propose a hypothesis on the impact of entrepreneurial role models on the desire for self-employment among individuals of different age groups as below:

H2. The relationship between entrepreneurial role models and being self-employed is positively stronger for younger individuals.

3. Research methodology

3.1. Data collection

Our study utilises a dataset from the GEM project that involved the participation of more than 42 countries worldwide. The data is available at https://www.gemconsortium.org/data. The data can be freely used, shared and adapted, provided appropriate credit is given to the original authors and the source is properly cited. No additional permissions were required to use this data (Reynolds et al., Citation2005). Since the GEM data is already anonymised and openly accessible to the public, the research did not involve any human subjects directly, and no identifiable personal information was used. Thus, ethical approval was not required for this study.

The GEM aims to understand the relative factors affecting national entrepreneurship activity and economic development and analyse the conceptual domains regarding social, cultural and political context (e.g. government, financial markets, management (skills), entrepreneurial opportunities, entrepreneurial potential, business and firms).

The GEM consists of two kinds of surveys: the adult population survey (APS) and the national expert survey (NES). Related to the NES, each national GEM team uses their own networks and contacts to select about 36 experts with a reputation and entrepreneurship activity experience. The face-to-face interview, approximately 45 min, focuses on the national experts’ opinion on entrepreneurship activity and their suggestions for promoting entrepreneurship in their country. Regarding the APS, the individual national GEM team makes a random survey and almost a phone call through landline phone numbers. Besides the demographic information (e.g. gender, age, household income and educational attainment), the participants will be asked questions about entrepreneurship activity, such as nascent entrepreneurs (alone or with others start a new firm), potential and discontinuing, employment status (e.g. full-time, part-time work, self-employed, seeking employment and a student), and support (e.g. role models). Each participating country conducts a random survey between May and August with around 2000 samples of individuals each year. Hence, the GEM offers a valid and reliable source for entrepreneurship research.

Vietnam has participated in the GEM project since 2013, and the Vietnam Chamber of Commerce and Industry (VCCI) is responsible for conducting a survey. Unfortunately, Vietnam does not have information for 2016 because it did not take part in the GEM project this year. Therefore, in total (years 2013, 2014, 2015 and 2017), the GEM comprises about 8000 observations, which are used in our study.

3.2. Dependent variable

The dependent variable was the self-employed. Similar to previous research scholars, such as Block and Sandner (Citation2009), Wyrwich (Citation2013), Vaillant and Lafuente (Citation2007) and Wennberg et al. (Citation2013), in this study, we treat the self-employed as an entrepreneurial activity. Vaillant and Lafuente (Citation2007), who also use the GEM data, suggest that we should not discriminate entrepreneurial activities based on the size or purpose of the venture. Therefore, self-employment or part-time entrepreneurial activities can count as having entrepreneurship.

In the data set of the GEM, we use question 5E, where respondent answers about their employment status. We select only the observation answer option ‘self-employed’. In the GEM dataset, 1 denotes ‘yes’, 2 denotes ‘no’, −1 denotes ‘don’t know’ and –2 means ‘refused’. During the data cleaning process, we choose only observations that receive values 1 and 2 only and make a coding this variable into binary variables: 1 = 1 = yes, 0 = 2 = no, whereas we exclude participants with the answers ‘don’t know’ and ‘refused’. Previous studies like Walter and Block (Citation2016), Zellweger et al. (Citation2011) and Fisch et al. (Citation2021) suggest that individuals with the answers ‘don’t know’ and ‘refused’ reflect they do not have clear employment status. Furthermore, this dependent variable has been used successfully and widely in prior literature (Lafuente et al., Citation2007; Nguyen & Do, Citation2022; Wyrwich et al., Citation2016).

3.3. Independent variables

The first independent variable was the entrepreneurial role model used to test the first hypothesis (H1). This independent variable is based on the GEM question of whether respondents personally know someone who had started a business in the last two years (dummy variable: 1 = yes, 0 = no). Previous studies have also successfully used this independent variable (Lafuente et al., Citation2007; Wennberg et al., Citation2013).

We also aim to examine the differences in entrepreneurship activities between young and older people. Therefore, we treat age as the second independent variable to test the second hypothesis (H2).

3.4. Controls

We controlled for a set of control variables at the individual level, including educational attainment, gender and household annual income. Educational attainment is an indicator of human capital (Obschonka & Stuetzer, Citation2017) and is measured by seven categories (1 = pre-primary education; 2 = primary education or first stage of basic education; 3 = lower secondary stage of basic education; 4 = (upper) secondary education; 5 = post-secondary non-tertiary education; 6 = first stage of tertiary education; 7 = second stage of tertiary education). Moreover, we control for gender (1 = male, 0 = female) and household annual income (1,000,000 VND) by six categories (1 = < 25; 2 = 25–49.9; 3 = 50–99.9; 4 = 100–149.9; 5 = 150–199.9; 6 = > 200).

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive findings

The sample comprised 3970 males (48.92%) and 4145 females (51.08%). The participants were primarily under 44 (72.42%), and approximately the same proportion (70%) was in the lower secondary stage of basic education and above. Surveyed respondents come from the lower middle class; 24.07% come from households with 50–99 million VND net income annually, while 20.7% come from households with a net income of around 100–149 million VND annually. A total of 4663 respondents (57.73%) reported that they knew someone who had started a business within the last two years, while the remaining 3414 had no prior entrepreneurial role models. Meanwhile, 3926 (48.4%) were self-employed, concerning the employment statistics. The samples are listed in .

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of our sample.

We are interested in entrepreneurship and its determinants among age groups, and mean comparison tests are applied. The findings show a significant difference in the self-employed rate between age groups 25–34 and 35–54 and 25–24 and 55–64 years old. The means comparison test also indicates that individuals in groups 25–34 age have a lower willingness to be entrepreneurs than those who are between 35 and 64 years old (). There is also a significant difference in knowing prior self-employed among age groups. Interestingly, individuals younger than 35 years old have been more influenced by entrepreneurial role models than those who are older than 35. As expected, the impact of entrepreneurial role models on entrepreneurial decisions is lower among younger participants than those older. This is due to the socialist heritage in Vietnam as well as collectivisation in former socialist countries (Fisch et al., Citation2021; Wyrwich, Citation2013). Furthermore, individuals younger than 35 years old have a higher score with regard to educational attainment than those who are older than 35 (). It could be argued that individuals exposed to most of their lives in transition to a market economy have lower opportunities to acquire formal education certificates than those living in a market economy (Wyrwich, Citation2013). The average household annual income of age groups 25–34 is also higher than those who are between 35 and 64 years old. There is no difference in the mean comparison test for participation in gender among age groups ().

Table 2. Entrepreneurship and its determinants among age groups.

4.2. Main findings

Statistical logit regression models were used to investigate the effect of prior familiarity with entrepreneurs as role models on the likelihood of becoming self-employed and the differences in the probability of becoming self-employed between old and young people who have known an entrepreneur within the last two years. As such, the dependent factor in these analyses was self-employment status, while the independent variable was the existence/lack of entrepreneurial role models. Gender, age, household income and education level were the control variables.

Model (I) of focuses on H1 and uses ‘self-employed’ as the dependent variable, while ‘entrepreneurial role models’ are the main independent variable. The findings (see ) indicate a substantial positive association between entrepreneurial role models and the likelihood of Vietnamese individuals choosing self-employment as their career path (Model I, β = 0.673, p < 0.001). These results suggest that individuals who know an entrepreneur personally are more willing to start a new business than those who do not. These findings are consistent with those reported by Lafuente and Vaillant (Citation2013) and Wyrwich et al. (Citation2016). Thus, H1 is supported.

Table 3. Determinants of self-employed (logit regression).

also reveals an inverted U-shaped correlation between participants’ age and tendency to become self-employed, as proven by (1) the positive coefficients. Particularly, individuals from age groups 35–44 (Model I, β = 1.162, p < 0.001) and 45–54 (Model I, β = 1.007, p < 0.001) were more likely to be self-employed than those from age groups 25–34 (Model I, β = 0.886, p < 0.001), and 55–64 (Model I, β = 0.889, p < 0.001).

Model (II) in focuses on the difference in entrepreneurship activity between old and young people when they both personally know an entrepreneur within the last two years (H2). We interacted with age groups with entrepreneurial role models as dummy variables to test the second hypothesis (H2). Interestingly, the regressions confirm the findings that young individuals who know an entrepreneur are more likely to start a new firm than older people with this social contact. The significant and negative age interaction coefficients of the younger groups were lower than those of the older groups. In particular, age groups 25–34 with β = −0.277, p < 0.01 compared to age groups 45–54 with β = −0.485, p < 0.001 (, Model II). Thus, hypothesis H2 was accepted.

In addition, the findings in show that annual household income is positively associated with the likelihood of individuals engaging in self-employment. The statistical models used (Models I and II, β = 0.180, p < 0.001) reveal that for every unit increase in household income, there is a corresponding 0.180 unit increase in the likelihood of pursuing entrepreneurial activities. This relationship was statistically significant (p < 0.001). There is a negative correlation between educational attainment and self-employment, perhaps because self-employment is a manual job (Thompson et al., Citation2012) or because there are still a limited number of entrepreneurship education programmes in Vietnam, such as entrepreneurial courses, workshops and seminars (Khuong & An, Citation2016). also shows the correlations of variables entered into the models.

Table 4. Correlation matrix.

5. Discussion and conclusion

The relationship between role models and entrepreneurial activity has garnered significant academic attention recently. However, little attention has been paid to examining the relationship in the emerging economies. This article addresses this research vacuum by investigating the influence of entrepreneurial role models on individuals’ inclination to pursue self-employment and by analysing the moderating effect of age on this relationship in Vietnam. Based on the GEM dataset (2013–2017), we found that individuals with prior linkages with an entrepreneur demonstrated an increased desire to participate in entrepreneurial endeavours. Moreover, age groups (35–54) are more likely to be self-employed than age groups (25–34 and 55–64). However, regarding having contact with prior entrepreneurs as role models, the empirical findings show that senior individuals are less likely to engage in entrepreneurial activities than their younger counterparts. These results are in line with previous studies conducted by Lafuente et al. (Citation2007), Lafuente and Vaillant (Citation2013) and Wyrwich et al. (Citation2016).

In particular, this study supports prior research indicating that the influence of entrepreneurial role models on entrepreneurship in transition economies is less evident in older individuals than in younger individuals (Lafuente & Vaillant, Citation2013; Róbert & Bukodi, Citation2000). A potential explanation is that older people in Vietnam might have less desire to acquire information and expertise from previous entrepreneurs. This tendency could be attributed to the historical influence of the socialist era, which discouraged entrepreneurship and business. The result shows a significant difference between the older generations who lived a long time in this system and the younger generation who were born and lived in the market economy. These results support previous literature in this field (Blanchflower & Freeman, Citation1997; Corneo, Citation2001; Sztompka, Citation1996; Wyrwich et al., Citation2016). In addition, the study implies that role models may offer an affordable alternative to costly channels of entrepreneurial support provided by (local) governments. In practice, these findings imply that the entrepreneurial role model is important in nurturing entrepreneurship. It is particularly even more inspiring to the young generation. This is crucial in entrepreneurial education designing and entrepreneurial ecosystem building. The mentorship programmes, talk shows and documentaries about successful entrepreneurs will foster the intention and decision to be entrepreneurs. It is also important to enhance positive role models of entrepreneurs in society.

Nonetheless, this study has several limitations. First, our primary focus on a single case study of Vietnam harnesses its external validity. Therefore, more attention should be paid to other countries to provide a comparative analysis. Additionally, the GEM dataset lacks other comprehensive variables for the channel of connection in detail. In addition, future research can incorporate more, such as GDP, CPI, governmental support and policies, financing for entrepreneurs, taxes or culture and regional entrepreneurship or extend to a larger time span.

Ethics declaration

This study has been performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Since the GEM data is already anonymised and openly accessible to the public, the research did not involve any human subjects directly, and no identifiable personal information was used. Thus, ethical approval was not required for this study.

Author contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the manuscript. Nguyen Thi Lanh: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Data Collection and Analysis, Writing, Critical Review; Truong Thi Ngoc Thuyen: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Data Collection and Analysis, Writing, Critical Review; Nguyen Quoc Anh: Conceptualisation, Methodology, Data Collection and Analysis, Writing, Critical Review; Nguyen Van Tuu: Conceptualisation, Methodology. The corresponding author (Nguyen Thi Lanh) is responsible for ensuring that the descriptions are accurate and agreed upon by all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

The data used in this study were obtained from the GEM Data, which is available at https://www.gemconsortium.org/data. The data can be freely used, shared and adapted, provided appropriate credit is given to the original authors and the source is properly cited. No additional permissions were required to use this data.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Nguyen Thi Lanh

Dr. Nguyen Thi Lanh currently works at the Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, Dalat University. Nguyen does research in Business Management, and Entrepreneurship.

Truong Thi Ngoc Thuyen

Dr. Truong Thi Ngoc Thuyen is Dean of the Economics and Business Administration department, at Dalat University. Her research interests are Innovation Management, International Business, and Entrepreneurship.

Nguyen Quoc Anh

Nguyen Quoc Anh is the Impact Evaluation Lead at Innovation Academy, University College Dublin, where he also conducts his PhD in Entrepreneurial Mindset Education. He is a Lecturer at the University of Social Sciences and Humanities, Vietnam National University in Vietnam. Before academia, Anh had an interesting career in enterprises, start-ups, and international development organisations. He was once an Innovation Manager at a universitybased Incubator in Vietnam, where he led a diverse team focusing on fostering an entrepreneurial mindset and technology commercialisation in higher education. His research interests lie at the intersection of entrepreneurship education, university-industry collaboration, and sustainability.

Nguyen Van Tuu

Nguyen Van Tuu is a Master student at the Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, Dalat University. His research focus on Business Management, and Entrepreneurship.

References

- Abbasianchavari, A., & Moritz, A. (2021). The impact of role models on entrepreneurial intentions and behavior: A review of the literature. Management Review Quarterly, 71(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-019-00179-0

- Adam-Müller, A. F., Andres, R., Block, J. H., & Fisch, C. (2024). Socialist heritage and the opinion on entrepreneurs: Micro-level evidence from Europe (June 9). Die Betriebswirtschaft, Forthcoming, Available at SSRN: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2447652

- Aidis, R., Estrin, S., & Mickiewicz, T. (2008). Institutions and entrepreneurship development in Russia: A comparative perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 23(6), 656–672. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.01.005

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Alesina, A., & Fuchs-Schündeln, N. (2007). Goodbye Lenin (or not?): The effect of communism on people’s preferences. American Economic Review, 97(4), 1507–1528. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.97.4.1507

- Andersson, M., & Koster, S. (2011). Sources of persistence in regional start-up rates—evidence from Sweden. Journal of Economic Geography, 11(1), 179–201. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbp069

- Andrade-Rojas, M. G., Li, S. Y., & Zhu, J. J. (2024). The social and economic outputs of SME-GSI research collaboration in an emerging economy: An ecosystem perspective. Journal of Small Business Management, 62(2), 656–699. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2022.2073362

- Andreff, W. (1993). The double transition from underdevelopment and from socialism in Vietnam. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 23(4), 515–531. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472339380000301

- Bandura, A., & Walters, R. H. (1977). Social learning theory (Vol. 1). Englewood cliffs Prentice Hall.

- Bauernschuster, S., Falck, O., Gold, R., & Heblich, S. (2012). The shadows of the socialist past: Lack of self-reliance hinders entrepreneurship. European Journal of Political Economy, 28(4), 485–497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2012.05.008

- Blanchflower, D. G., & Freeman, R. B. (1997). The attitudinal legacy of communist labor relations. ILR Review, 50(3), 438–459. https://doi.org/10.1177/001979399705000304

- Block, J., & Sandner, P. (2009). Necessity and opportunity entrepreneurs and their duration in self-employment: Evidence from German micro data. Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade, 9(2), 117–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10842-007-0029-3

- Bosma, N., Hessels, J., Schutjens, V., Van Praag, M., & Verheul, I. (2012). Entrepreneurship and role models. Journal of Economic Psychology, 33(2), 410–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2011.03.004

- Busenitz, L. W., Gomez, C., & Spencer, J. W. (2000). Country institutional profiles: Unlocking entrepreneurial phenomena. Academy of Management Journal, 43(5), 994–1003. https://doi.org/10.2307/1556423

- Cerviño, J., Chetty, S., & Martín Martín, O. (2024). Impossible is nothing: Entrepreneurship in Cuba and small firms’ business performance. Journal of Small Business Management, 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2024.2322991

- Corneo, G. (2001). Inequality and the state: Comparing US and German preferences. Annales D’Economie Et De Statistique, 63–64, 283–296. https://doi.org/10.2307/20076306

- Criaco, G., Sieger, P., Wennberg, K., Chirico, F., & Minola, T. (2017). Parents’ performance in entrepreneurship as a “double-edged sword” for the intergenerational transmission of entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 49(4), 841–864. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9854-x

- Davidsson, P., & Honig, B. (2003). The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(3), 301–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(02)00097-6

- Fisch, C., Wyrwich, M., Nguyen, T. L., & Block, J. (2021). Historical institutional differences and entrepreneurship: Socialist legacy in Vietnam. International Review of Entrepreneurship, 19(4), 499–522. https://www.senatehall.com/entrepreneurship?article=706

- Fritsch, M., & Rusakova, A. (2012). Self-employment after socialism: Intergenerational links, entrepreneurial values, and human capital. International Journal of Developmental Science, 6(3–4), 167–175. https://doi.org/10.3233/DEV-2012-12106

- Fritsch, M., & Wyrwich, M. (2014). The long persistence of regional levels of entrepreneurship: Germany, 1925–2005. Regional Studies, 48(6), 955–973. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2013.816414

- Ingole, N., & Sohani, S. S. (2024). Concurrent interplay of entrepreneurs–intermediaries–stakeholders in emerging economies at different phases of entrepreneurial process. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2024.2303458

- Joensuu-Salo, S., Viljamaa, A., & Varamäki, E. (2021). Understanding business takeover intentions—the role of theory of planned behavior and entrepreneurship competence. Administrative Sciences, 11(3), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11030061

- Khuong, M. N., & An, N. H. (2016). The dactors affecting entrepreneurial intention of the students of Vietnam national university—A mediation analysis of perception toward entrepreneurship. Journal of Economics, Business and Management, 4(2), 104–111. https://doi.org/10.7763/JOEBM.2016.V4.375

- Kolvereid, L. (1996). Prediction of employment status choice intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 21(1), 47–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879602100104

- Krueger, N. F., & Carsrud, A. L. (1993). Entrepreneurial intentions: Applying the theory of planned behaviour. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 5(4), 315–330. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879301800101

- Krueger, N. F., Reilly, M. D., & Carsrud, A. L. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5–6), 411–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(98)00033-0

- Lafuente, E., Vaillant, Y., & Rialp, J. (2007). Regional differences in the influence of role models: Comparing the entrepreneurial process of rural Catalonia. Regional Studies, 41(6), 779–796. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400601120247

- Lafuente, E. M., & Vaillant, Y. (2013). Age driven influence of role-models on entrepreneurship in a transition economy. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 20(1), 181–203. https://doi.org/10.1108/14626001311298475

- Laspita, S., Breugst, N., Heblich, S., & Patzelt, H. (2012). Intergenerational transmission of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 27(4), 414–435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2011.11.006

- Liñán, F., & Fayolle, A. (2015). A systematic literature review on entrepreneurial intentions: Citation, thematic analyses, and research agenda. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11(4), 907–933. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-015-0356-5

- Nguyen, T. L., & Do, Q. H. (2022). Entrepreurial self-efficacy and the likelihood of being self-employed–A comparison of urban and rural areas in Vietnam. Dalat University Journal of Science, 3–25.) https://doi.org/10.37569/DalatUniversity.12.4S.832(2022)

- Nicholls-Nixon, C. L., Singh, R. M., Hassannezhad Chavoushi, Z., & Valliere, D. (2024). How university business incubation supports entrepreneurs in technology-based and creative industries: A comparative study. Journal of Small Business Management, 62(2), 591–627. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2022.2073360

- Nowiński, W., & Haddoud, M. Y. (2019). The role of inspiring role models in enhancing entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Business Research, 96, 183–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.11.005

- Obschonka, M., & Stuetzer, M. (2017). Integrating psychological approaches to entrepreneurship: The Entrepreneurial Personality System (EPS). Small Business Economics, 49(1), 203–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9821-y

- Osabohien, R., Worgwu, H., & Al-Faryan, M. A. S. (2024). Mentorship and innovation as drivers of entrepreneurship performance in Africa’s largest economy. Social Enterprise Journal, 20(1), 76–90. https://doi.org/10.1108/SEJ-02-2023-0019

- Ozgen, E., & Baron, R. A. (2007). Social sources of information in opportunity recognition: Effects of mentors, industry networks, and professional forums. Journal of Business Venturing, 22(2), 174–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2005.12.001

- Pablo-Lerchundi, I., Morales-Alonso, G., & González-Tirados, R. M. (2015). Influences of parental occupation on occupational choices and professional values. Journal of Business Research, 68(7), 1645–1649. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.02.011

- Reynolds, P., Bosma, N., Autio, E., Hunt, S., De Bono, N., Servais, I., Lopez-Garcia, P., & Chin, N. (2005). Global entrepreneurship monitor: Data collection design and implementation 1998–2003. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 205–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-005-1980-1

- Róbert, P., & Bukodi, E. (2000). Who are the entrepreneurs and where do they come from? Transition to self-employment before, under and after communism in Hungary. International Review of Sociology, 10(1), 147–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/713673992

- Runst, P. (2013). Post-socialist culture and entrepreneurship. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 72(3), 593–626. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajes.12022

- Schumpeter, J. A. (1934). The theory of economic development: An inquiry into profits, capital, credit, interest, and the business cycle (Vol. 55). Transaction Publishers.

- Schwartz, S. H., & Bardi, A. (1997). Influences of adaptation to communist rule on value priorities in Eastern Europe. Political Psychology, 18(2), 385–410. https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00062

- Smallbone, D., & Welter, F. (2001). The distinctiveness of entrepreneurship in transition economies. Small Business Economics, 16(4), 249–262. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011159216578

- Snihur, Y., & Clarysse, B. (2022). Sowing the seeds of failure: Organizational identity dynamics in new venture pivoting. Journal of Business Venturing, 37(1), 106164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2021.106164

- Sobhan, N., & Hassan, A. (2024). The effect of institutional environment on entrepreneurship in emerging economies: Female entrepreneurs in Bangladesh. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 16(1), 12–32. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-01-2023-0028

- Sztompka, P. (1996). Looking back: The year 1989 as a cultural and civilizational break. Communist and Post-Communist Studies, 29(2), 115–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0967-067X(96)80001-8

- Thompson, P., Jones-Evans, D., & Kwong, C. (2012). Entrepreneurship in deprived urban communities: The case of Wales. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 2(1), 1-31. https://doi.org/10.2202/2157-5665.1033

- Tkachev, A., & Kolvereid, L. (1999). Self-employment intentions among Russian students. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 11(3), 269–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/089856299283209

- Tran, H. T. (2019). Institutional quality and market selection in the transition to market economy. Journal of Business Venturing, 34(5), 105890. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2018.07.001

- Vaillant, Y., & Lafuente, E. (2007). Do different institutional frameworks condition the influence of local fear of failure and entrepreneurial examples over entrepreneurial activity? Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 19(4), 313–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985620701440007

- Van Auken, H., Fry, F. L., & Stephens, P. (2006). The influence of role models on entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 11(02), 157–167. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1084946706000349

- Volkmann, C. K., & Tokarski, K. O. (2009). Student attitudes to entrepreneurship. Management & Marketing, 4(1), 17–38.

- Wagner, J., & Sternberg, R. (2004). Start-up activities, individual characteristics, and the regional milieu: Lessons for entrepreneurship support policies from German micro data. The Annals of Regional Science, 38(2), 219–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00168-004-0193-x

- Walter, S. G., & Block, J. H. (2016). Outcomes of entrepreneurship education: An institutional perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 31(2), 216–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2015.10.003

- Welter, F. (2011). Contextualizing entrepreneurship—Conceptual challenges and ways forward. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(1), 165–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00427.x

- Wennberg, K., Pathak, S., & Autio, E. (2013). How culture moulds the effects of self-efficacy and fear of failure on entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 25(9–10), 756–780. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2013.862975

- Wyrwich, M. (2012). Regional entrepreneurial heritage in a socialist and a postsocialist economy. Economic Geography, 88(4), 423–445. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2012.01166.x

- Wyrwich, M. (2013). Can socioeconomic heritage produce a lost generation with regard to entrepreneurship? Journal of Business Venturing, 28(5), 667–682. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2012.09.001

- Wyrwich, M. (2015). Entrepreneurship and the intergenerational transmission of values. Small Business Economics, 45(1), 191–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-015-9649-x

- Wyrwich, M., Sternberg, R., & Stuetzer, M. (2019). Failing role models and the formation of fear of entrepreneurial failure: A study of regional peer effects in German regions. Journal of Economic Geography, 19(3), 567–588. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lby023

- Wyrwich, M., Stuetzer, M., & Sternberg, R. (2016). Entrepreneurial role models, fear of failure, and institutional approval of entrepreneurship: A tale of two regions. Small Business Economics, 46(3), 467–492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-015-9695-4

- Yitshaki, R. (2024). Advice seeking and mentors’ influence on entrepreneurs’ role identity and business-model change. Journal of Small Business Management, 1–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2024.2307494

- Zellweger, T., Sieger, P., & Halter, F. (2011). Should I stay or should I go? Career choice intentions of students with family business background. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(5), 521–536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2010.04.001