Abstract

The complex nature of the entrepreneurial environment warrants that studies go beyond main effect to examining boundary conditions in such relationships. Studies on the link between career adaptability and entrepreneurial intentions exist, yet important questions, including the extent to which motivational variables (future time perspective and promotion focus behaviour) might moderate the relationship remains untested. This study draws on the self-regulatory and socio-emotional selectivity theories, arguing that the relation between career adaptability and entrepreneurial intentions would be contingent on future time perspective and promotion focus behaviour. The SP SS and AMOS statistical softwares facilitated the data analysis. The path analysis results among students in a Ghanaian Public University (N = 397) showed that career adaptability, future time perspective, and promotion focus behavior relates positively to entrepreneurial intentions. Further, it was revealed that career adaptability was beneficial for entrepreneurial intentions for students who scored low on future time perspective and high on promotion focus. The implications of this study are in threefold: for undergraduate students, for counsellors interested in developing student entrepreneurs and for pedagogical development and improvement, particularly those teaching of entrepreneurship in Ghanaian universities.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

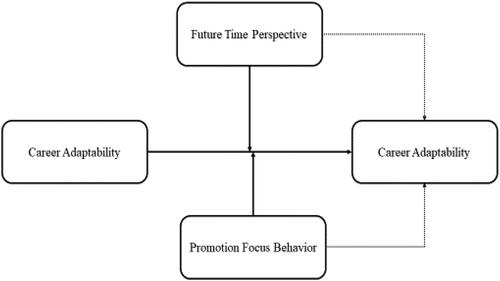

Intentions play an important role in the performance of behavior. In the context of entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial intentions represent the purposeful inclination to create, own, and manage one’s business in future, and such intentions have been shown to predict actual entrepreneurial behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991; Neneh, Citation2019). Specifically, the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991) has been utilised in several entrepreneurship studies to explain when intentions to perform a particular behavior was associated with greater engagement in that behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991; Neneh, Citation2019). Scholarly attention in entrepreneurial intentions research is burgeoning (Miao et al., Citation2018, Park et al., Citation2020; Badulescu et al., Citation2015; Badulescu, Citation2015) because such intentions constitute an important first-step in starting the entrepreneurial venture and having a successful venture (Neneh, Citation2019). Moreover, intentions show the level of motivation for a particular career/behavior and determines the intensity and persistence to pursue that career/behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991; Krueger, Reilly, & Carsrud., 2000). Owing to this, interest in identifying antecedents of entrepreneurial intentions, and when those antecedents might stimulate such intentions is still a worthwhile research venture in the field of entrepreneurship. Previous studies show that career adaptability is beneficial for entrepreneurial intentions for self-efficacious individuals (Tolentino et al., Citation2014). The dynamic nature of the entrepreneurial environment requires that individuals who venture into entrepreneurial career possess some psychosocial resources that enable them to function effectively. A strategic psychosocial resource that might facilitate entrepreneurial intentions is career adaptability (Savickas, Citation1997; Zhang et al., Citation2024). According to career construction theory (Savickas, Citation2013), career adaptability is an important psychosocial resource that enables individuals to plan, actively explore, prepare for the future, and confidently make career choices, leading them to adapt effectively in dynamic and ambiguous work environments. Although career adaptability is beneficial for entrepreneurial intentions (Tolentino et al., Citation2014; Zhang et al., Citation2024), it might not be the case under all circumstances. The extant literature shows that career adaptability (Zhang et al., Citation2024), career self-efficacy (Zhang et al., Citation2024), proactive personality (Neneh, Citation2019), future time perspective (Kiani et al., Citation2020), age (Meoli, Citation2018), and gender (Gielnik et al., Citation2018; Ward et al., Citation2019) are important precursors of entrepreneurial intentions. Previous studies have shown that the link between career adaptability and entrepreneurial intentions is much more complex than has been reported. For example, gender (Zhang et al., Citation2024) and cultural intelligence (Presbitero & Quita, Citation2017) have been found to moderate the relationship between career adaptability and entrepreneurial intentions. Despite the insights offered by previous scholarship on the link between career adaptability and entrepreneurial intentions, there is a paucity of knowledge regarding how promotion focus behaviour (change and growth-oriented behaviours that allow the individual to achieve gains or success in life, Brockner et al., Citation2004) and future time perspective (how individuals respond to the passage of time, Boyd & Zimbardo, Citation2005; Stolarski et al., Citation2011; Zimbardo & Boyd, Citation2014) may influence the connection between career adaptability and entrepreneurial intentions. Furthermore, scholars posit that promotion focus behaviour is associated with change and risk-taking behaviours that result in success (Brockner et al., Citation2004). Those with a strong future time perspective tend to embrace learning and performance-oriented goals, leading them to prioritise their future (Carstensen et al., Citation1999; Kiani et al., Citation2020). Consequently, the present study draws on the self-regulatory focus (Brockner et al., Citation2004; Higgins, Citation2000) and socio-emotive selective (Carstensen, Citation1993; Carstensen et al., Citation1999) theories to explain how promotion focus behaviour and future time perspective might facilitate the demonstration of enterprising behaviour, such as entrepreneurial intentions, as well as moderate the connection between career adaptability and entrepreneurial intentions. This has received less attention in the literature. The study makes three significant contributions to the entrepreneurship literature (see ). First, the study contributes to the entrepreneurship literature by testing the main effects of two important motivational variables: future time perspective and promotion focus behaviour. Individuals with a promotion focus can optimise their gains in dynamic contexts (Higgins, Citation2006). Those with a strong future time perspective focus on priority or important goals, and in the case of undergraduate students, employment is an important immediate goal (Carstensen et al., Citation1999). Secondly, the study hypothesises that students with a strong future time perspective would not procrastinate on career decision-making and planning behaviours. With regard to promotion focus behaviour (behaviour associated with creativity, resilience, focus on gains, and flexibility of thought), the study hypothesises that career adaptability will relate more positively to entrepreneurial intentions for individuals high in promotion focus behaviour. Finally, the study sought to test the relationship between career adaptability and entrepreneurial intentions in the Ghanaian context. This was done with the aim of broadening knowledge and contributing to the cross-cultural relevance of such outcomes (George, Citation2015; Walsh, Citation2015; Kolk & Rivera-Santos, Citation2018). depicts the conceptual framework of the study.

2. Theory and hypothesis development

2.1. Career adaptability and entrepreneurial intentions

Career adaptability is important for optimal performance in an uncertain work environment. According to Savickas (Citation1997), career adaptability represents the ability and readiness of an individual to cope with, perform effectively, and succeed in an unpredictable work context. According to the career construction theory, career adaptability is an important psychosocial resource involving concern (i.e. preparation for the future), control (i.e. assuming responsibility for one’s career), curiosity (i.e. keen on finding and achieving the best possible career fit), and confidence (i.e. the efficacy to make career choices; Savickas & Porfeli, Citation2012), that is vital for career success. Together, these components constitute adaptive resources, which enables an individual to cope well with current or anticipated environmental trajectories (Savickas & Porfeli, Citation2012; Tolentino et al., Citation2014). Career adaptability relates positively to general and professional well-being, and career success (Maggiori et al., Citation2013; Zacher, Citation2014). Consequently, career adaptability might foster entrepreneurial intentions.

Entrepreneurial intention is defined as the motivation to pursue an opportunity, which has significant implications for establishing a business in future (Ajzen, Citation1991; Krueger et al., Citation2000). The theory of planned behavior has been used to show the link between intentions and the performance of actual behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991), and following this theoretical framework, Van Gelderen et al. (Citation2018) contends that intention rather than spontaneity was the starting point of business creation, and that people with strong intentions were more likely to invest their energies and efforts toward the realization of their goal (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation2010; Gielnik et al., Citation2018). Meta-analytic evidence shows that 28% of behavior is accounted for by intentions (Sheeran, Citation2002). Further, some cross sectional (Shirokova et al., Citation2016; Van Gelderen et al., Citation2015) and longitudinal studies (Neneh, Citation2019; Kautonen et al., Citation2015; Shinnar et al., Citation2018) conducted in several countries showed that strong entrepreneurial intentions relate to actual entrepreneurial behavior.

Entrepreneurial career is characterized by ambiguous career trajectory, uncertainties, and risk (Parker, Citation2018), which requires appropriate responses in the form of effective adaptation from the individual (Shane et al., Citation2003; Tolentino et al., Citation2014). Career adaptability provides the individual with the strategic resources to effectively adapt to changes and unpredictable career trajectories associated with entrepreneurial career (cf. Zhang et al., Citation2024). Therefore, individuals who possess higher levels of career adaptability resources are more likely than their counterparts who possess less of these resources to succeed in an entrepreneurial career. Consistent with this thinking, Tolentino et al. (Citation2014) demonstrated in a Serbian context that career adaptability relates more positively to entrepreneurial intentions. Similarly, Zhang et al. (Citation2024) recently investigated entrepreneurial self-efficacy as an underlying mechanism in the relationship between career adaptability and entrepreneurial intentions among 1063 students recruited from three Chinese universities. The authors found that career adaptability was beneficial for entrepreneurial intentions among students (Zhang et al., Citation2024), suggesting that career adaptability provides individuals with the psychosocial resources required to navigate the dynamic and unpredictable entrepreneurial environment successfully. Consequently, we hypothesized that:

H1: Career adaptability relates positively to entrepreneurial intentions.

2.2. Future time perspective and entrepreneurial intentions

A future-oriented perspective encourages individuals to transition from the identification of opportunities to the pursuit of entrepreneurial careers (Kiani et al., Citation2020). Individuals with a high future time perspective tend to view their current intentions as valuable, as they believe these intentions may lead to the realisation of higher future goals (De Bilde et al., Citation2011; Simons et al., Citation2004; as cited in Kiani et al., 2020). Individuals with a high future time perspective are more likely to engage in present actions such as the search for entrepreneurial ideas and opportunities (Gielnik et al., Citation2018; Boyd & Zimbardo, Citation2005; Stolarski et al., Citation2011). Furthermore, future time perspective enables the individual to adopt a more meticulous approach to the entrepreneurial process, leading such individuals to identify and implement realistic opportunities (Boyd & Zimbardo, Citation2005; Stolarski et al., Citation2011; Simons et al., Citation2004). Moreover, higher levels of future time perspective are associated with better coping with negative consequences (Boyd & Zimbardo, Citation2005), as such individuals have mastery and control over the entrepreneurial process (Stolarski et al., Citation2011). Consequently, higher levels of future time perspective engender confidence in individuals, allowing them to transform their ideas and opportunities into realistic entrepreneurial intentions (Gielnik et al., Citation2018; Kvaskova & Almenara, Citation2021; Park et al., Citation2020). Moreover, previous studies found that future time perspective is positively associated with entrepreneurial intentions (Kiani et al., Citation2020), career commitment (Park & Jung, Citation2015) and late career planning (Fasbender et al., Citation2019). Therefore, we hypothesize that:

H2: Future time perspective relates positively and significantly to entrepreneurial intentions.

2.3. Future time perspective as a moderating factor

This study contends that the positive relationship between career adaptability and entrepreneurial intentions would depend on other motivational variables. Specifically, an individuals’ score on future time perspective and promotion focus behavior would lead to differential relationship between career adaptability and entrepreneurial intentions for high vs. low individuals on future time perspective and promotion focus, respectively. Perception of time influences behavior (Kooij & Van De Voorde, Citation2011). Therefore, how an individual perceives time, whether there is more or less time available to them can lead to the procrastination of certain behaviors into the future or the performance of those behaviors now. Indeed, individuals who score high on future time perspective measure may place premium on developing new experiences, skills, and knowledge to achieve goals in an unknown future. In this regard, such individuals tend to delay the performance of certain behaviors until that unknown future arises. Conversely, those who score low on future time perspective tend to prioritise present goals, particularly those that are important for attainment of their future aspirations, such as employment and job creation (Korff et al., Citation2017). Therefore, the study argues that a students’ performance on the future time perspective scale would evoke different behaviors, in terms of how they respond to adaptability resources, and consequently, entrepreneurial intention.

Individuals who score high on the future time perspective scale would focus on increasing the breadth of their knowledge, developing their capacities, and accumulating more resources for the pursuit of their goals in the unforeseen future, whereas individuals who score low would concentrate on activities or resources that would lead to the fulfilment of short-term goal (Carstensen, Citation2006), particularly venture creation. Further, individuals with high scores on future time perspective are more likely to not focus on existing circumstances (i.e. high levels of unemployment in Ghana) while those who score low would focus on existing circumstances (Bal et al., Citation2013). Consequently, students who score low on future time perspective would respond positively to career adaptability, as they would leverage on adaptability resources such as concern, confidence, exploration, and control to develop and implement their business creation ideas. Because such active search and exploration of the Ghanaian job market would provide them with information on the high level of unemployment, which might challenge them to think of creating a business before graduation. On the other hand, those who score high on future time perspective may be inclined to think that they have more time ahead of them, which might lead them to procrastinate their business creation intentions as well as limit their exploratory behaviors. Therefore, such individuals may not benefit from career adaptability resources. Consequently, at low level of future time perspective, career adaptability might relate strongly and positively to entrepreneurial intentions than at high level. This line of reasoning is consistent with research findings. For example, Korff et al. (Citation2017) found that social exchange relates more strongly to affective commitment for workers who score low on future time perspective. Drawing on Korff et al. (Citation2017) study and the socioemotional selectivity theory, this study hypothesise’s that:

H3: Career adaptability relates positively and significantly to entrepreneurial intentions at lower rather than higher level of future time perspective.

2.4. Promotion focus behavior and entrepreneurial intentions

Since entrepreneurial behavior is a self-regulated activity (Tolentino et al., Citation2014), promotion focus behavior may have a stronger influence on intentions to engage in such a behavior. The regulatory focus theory (Higgins, Citation1997, Citation1998) argues that people are inclined to engage in either promotion focus (i.e. behaviors that focus on maximising gains) or prevention focus (i.e. behaviors that focus on minimising losses) at work or nonwork environment. As promotion and prevention focus individuals have different motivations, they tend to engage in different behaviors. Rather than testing the main effects of promotion and prevention focus behavior on entrepreneurial intentions, this study chose to test only promotion focus. Two reasons accounted for this. First, the study is about entrepreneurial intentions and promotion focus behavior challenges individuals to be more creative and to have a growth mindset, which is crucial for an entrepreneurial career. Secondly, promotion focus behavior is important for the performance of adaptive and creative behaviors (Petrou et al., Citation2020). Promotion focus behavior has been associated with creativity (Lanaj et al., Citation2012; Neubert et al., Citation2008; Petrou et al., Citation2020) and adaptivity (Petrou et al., Citation2020); efficacy, openness to new experiences, and extraversion (Lanaj et al., Citation2012; Vaughn et al., Citation2008); and preference for change (Liberman et al., Citation1999). Promotion focus individuals can adapt to dynamic environments (such as the entrepreneurial environment) and generate creative ideas to achieve success in those environments (Brenninkmeijer & Hekkert-Koning, Citation2015). Based on these studies, we hypothesize that:

H4: Promotion focus behavior relates positively and significantly to entrepreneurial intentions.

2.5. Promotion focus behavior as moderator

Career adaptability is an important psychosocial resource, yet its effect on career decision-making and career outcomes depends on contextual factors (Savickas & Porfeli, Citation2012). Individuals with strong career adaptability are more confident in identifying business opportunities, exploiting those opportunities, setting achievable goals, and adapting to the ever-evolving entrepreneurial environment (Tolentino et al., Citation2014). However, even if all the participants in the study were to possess similar levels of career adaptability, not all of them would be able to enact an entrepreneurial role (Markman & Baron, Citation2003). Future entrepreneurs need to be confident that their intentions would yield concrete results, and that they can overcome the inherent challenges associated with entrepreneurial career (Krueger & Brazeal, Citation1994). Researchers suggest that career adaptability is influenced by boundary conditions (Savickas & Porfeli, Citation2012). Therefore, this study intimates that promotion focus, a motivational construct under the regulatory focus framework (Higgin, Citation2000) would strengthen entrepreneurial intentions, because high promotion focus is associated with adaptivity and creativity, which are vital for business ownership and career readiness. Further, promotion-oriented individuals tend to adopt an approach that will encourage them to manage challenges in their environment (Crowe & Higgins, Citation1997; Hung et al., Citation2018). In this regard, this study intimates that for high promotion focused individuals, a high level of career adaptability can stimulate their entrepreneurial intentions because they are more likely to respond positively to the perceived challenges and opportunities to stretch their adaptability resources compared to their counterparts who are low on promotion focus. Consequently, this study hypothesis’s that:

H5: Career adaptability relates positively to entrepreneurial intentions under conditions of high rather than low promotion focus.

3. Method

3.1. Sample and procedure

The study involved 397 students, enrolled into various undergraduate business-related programmes such as finance, marketing, accounting, business administration, and information technology in a Ghanaian public university. The university is in the capital city of Ghana, Greater Accra Region, with more universities than the other regions of Ghana. This region has an approximate population of 4.1 million and the most densely populated region in the country (Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) 2012; Arko-Mensah et al., Citation2019). The Accra Metropolitan Area (where the university is located) has a cosmopolitan population and seen as the economic hub of the Greater Accra Region with a number of administrative, educational, industrial, commercial, tourism, health and other important establishments (GSS 2016). These institutions provide employment opportunities to the residents, and their presence continues to attract people from all parts of the country and beyond to transact various businesses. The indigenous people, until recently, were mostly engaged in fishing and farming. Despite the number of commercial and administrative establishments, the city has a blend of individuals ranging from the rich to the poor. About 70.1 per cent of the population aged 15 years and older are economically active, while 29.9 per cent are inactive. Of those who are economically inactive, a larger percentage are students (52.0%) (GSS 2016). According to the GSS (2023), 14.7% of the active population are unemployed. This notwithstanding, the unemployment rate in the entire Greater Accra region was 25.7%). In the same report, youth unemployment (that is those economically active and between 15-35 years) stood at 21.7%.

The convenience sampling strategy was employed to select the participants for the study. The researchers administered the questionnaire to the students on campus and in their classrooms. The survey was completed by students pursuing undergraduate programme at different levels. Specifically, the sample comprised level 100 to level 400 students. Prior to administering the questionnaire, we sought for their consent and provided clear instructions to guide the completion of the survey in the first page of the questionnaire. Participants were provided with a detailed explanation of the research objectives, the procedures they would undergo and their right to withdraw from the study at any time without a consequence. Following this, only individuals who were willing and interested in the study were given the questionnaire to complete. Thus, a verbal consent was sought and taken from the participants. This was to ensure participation was voluntary and participants were not under coercion. Second, this process built trust between the researchers and participants. Indicating the researchers were committed to transparency and respect for participants’ rights and well-being. Participants were instructed to complete the survey independently by responding to the questions on career adaptability, future time perspective, promotion focus behavior, entrepreneurial intentions, and demographic characteristics. Participation was voluntary and participants could withdraw from the study at any point without a reason or a consequence. No compensation was offered for participation in the study. We took steps to ensure confidentiality of responses. First, the surveys were put in an envelope, and participants were instructed to put the completed survey into the same envelope, seal and sign across. We did this to ensure that only members of the research team see the individual responses. Finally, participants were instructed to not write their names or initials on any part of the survey packet, as that might reveal their identity, and thus, breach the code of confidentiality. The survey was answered once by each participant. Before administering the questionnaires, ethical clearance was sought and approval given by the Research and Consultancy Centre of the University which doubles as the Ethics Committee of the University of Professional Studies, Accra. Analysis of demographic factors revealed that the sample consisted of 52.1% females and 47.9% males. In addition, 65.7% of the sample indicated that they were not working. Finally, the average age of participants was 23.13 years old (SD = 4.52).

3.2. Measures

All the items were constructed in English. With the exception of career adaptability, which was measured on a 7-point Likert scale, the remaining scales had response options ranging from 5 = strongly agree to 1 = strongly disagree. Internal consistency results for all the main variables are shown in .

Table 1. Validity assessment.

3.2.1. Career adaptability

We assessed career adaptability with the 24-item Career Adapt-Ability Scale (CAAS; Savickas & Porfeli, Citation2012), which measures four dimensions of adaptability resources, namely, concern, control, curiosity, and confidence. Sample items include ‘thinking about what my future will be like’, ‘keeping upbeat’, ‘exploring my surroundings’, and ‘performing tasks efficiently’. As a result of the high bivariate correlation between the dimensions of career adaptability (r ≥ .80, p < .001), the study aggregated the four dimensions into a composite career adaptability construct for purposes of hypothesis testing; and the reason for using a composite score rather than subdimensions was consistent with previous studies (Fasbender et al., Citation2019; Ramos & Lopez, Citation2018; Zacher, Citation2014). For instance, for a similar reason, (Fasbender et al., Citation2019) realising a high bivariate correlation ranging from r = 0.53 between concern and control to r = 0.79 between control and confidence, aggregated the score rather than testing each dimension of career adaptability.

3.2.2. Promotion focus behavior

The study measured promotion focus behavior with 3-items from the Regulatory Focus Strategies scale (Ouschan et al., Citation2007). The scale was developed and validated among undergraduate students in Australia and Japan. All the three-items loaded significantly (factor loadings, > .40, p < .001). Sample item includes ‘To achieve something, one must try all possible ways of achieving it’.

3.2.3. Future time perspective

Carstensen and Lang (Citation1996) 10-item scale was used to measure general future time perspective. However, the study excluded the last three items (which were reverse scored) from further analysis due to poor loadings: ‘There are only limited possibilities in my future,’ ‘I have the sense that time is running out,’ and ‘As I get older, I begin to experience time as limited’. Therefore, the three-items were excluded from further analysis, consistent with previous studies (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999). Consequently, 7-items were used to measure general future time perspective, which is consistent with previous studies (Carstensen & Lang, Citation1996; Fasbender et al., Citation2019). High score shows high future time perspective, and low score suggests low future time perspective. Sample item includes ‘many opportunities await me in the future’.

3.2.4. Entrepreneurial intentions

The study measured entrepreneurial intentions with 6-items (Liñán & Chen, Citation2009). Sample item includes ‘My professional goal is to become an entrepreneur’. All the items loaded significantly (factor loadings > .60, p < .001). Thus, the scale is good for the analysis.

3.2.5. Control variables

The study controlled some variables including gender (0 = male, 1 = female) and working status (0 = working, 1 = not working) of participants because they related to career adaptability and entrepreneurial intentions, respectively.

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary analysis

4.1.1. Bivariate correlation, reliability, and common method bias analysis

The SPSS software version 29 for IBM was used to facilitate most of the preliminary analyses including bivariate correlation, reliability analysis, and Harman’s Single Factor Analysis (an exploratory factor analysis procedure). Also, SPSS AMOS was used to facilitate the hypothesis testing and perform tests such as path analysis and confirmatory factor analysis. As all the measures were taken from a single source, the Harman’s Single factor analysis test was performed using Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was performed to determine whether common method bias was an issue. First, we conducted principal component exploratory factor analysis with 22-items comprising: career adaptability (12-items), future time perspective (2-items), promotion focus (2-items), and entrepreneurial intentions (6-items). EFA was performed with all the 22 items simultaneously and a single factor was extracted. The single factor accounted for 36.68% of the variance, which is less than 50%. Thus, common method bias is not an issue in this study. Similarly, confirmatory factor analysis confirmed that common method bias is not an issue, as a single factor more yielded a poor fitting model: χ2 = 1188.84, df = 209, p < .001, CFI = .69, TLI = .67, RMSEA = .12 compared to a four factor model that produced a better model: χ2 = 527.86, df = 203, p < .001, CFI = .90, TLI = .89, RMSEA = .07. Together, the exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses results showed that common method bias is unlikely to confound the results of the present study.

4.2. Validity assessment

Discriminant and convergent validity for the constructs were assessed using AVE and MSV values. To assess validity of the constructs, CFA was performed with items loading unto their respective constructs. The factors loadings for all the items as well as the correlation outputs were copied and pasted in the Gaskins Stats tool to generate the validity statistics. Aside from entrepreneurial intentions that all the 6-items were retained in the validity analysis, 12 items were deleted from career adaptability, 5-items from future time perspective, and 6-items from promotion focus behavior. This analysis yielded acceptable validity values for three out of the four constructs we tested empirically in the study. Specifically, career adaptability (12-items), future time perspective (2-items), and entrepreneurial intentions (6-items) met all the convergent and discriminant validity requirement. shows the results of the validity assessment. Further, confirmatory factor analysis revealed significant factor loadings for items measuring each variable: career adaptability (factor loadings ≥.60, p < .001), entrepreneurial intentions (factor loadings ≥0.61, p <. 001, with higher loading value = 0.89), promotion focus behavior (≥0.57, p <. 001, with higher loading value of 0.78); and future time perspective (≥0.58, p <. 001, with highest factor loading of 0.89). Thus, the study concluded that the scales were valid. The bivariate correlation results show that gender relates positively and marginally to career adaptability r = .11, p = .054; and working status relates negatively to future time perspective, r = −. 14, p = .011 and marginally correlated with entrepreneurial intentions, r = −.10, p = .077. Thus, these demographic factors were controlled in this model. Finally, as expected, career adaptability, r =. 43, p <. 001 and future time perspective, r = .35, p <. 001 correlated significantly and positively to entrepreneurial intentions. However, promotion focus behavior did not correlate significantly to entrepreneurial intentions, r = −.08, p =. 142.

4.3. Hypothesis testing

The path analysis test – a form of structural equation modelling that utilizes only latent constructs was employed to test the hypothesized relationships in the study (Kelloway, Citation2015). To ensure that the model was robust, the study controlled for gender and working status, which were found to correlate with career adaptability and entrepreneurial intentions. The structural model was appropriate: χ2 = 14.45, df = 11, p = .209; CFI = .99, TLI = .98, RMSEA = .03. Specifically, after controlling for gender and working status, we observed that career adaptability, β = .30, SE = .05, p < .001 significantly and positively predicted entrepreneurial intentions. Thus, hypothesis 1 is supported. Furthermore, future time perspective significantly and positively predicted entrepreneurial intentions, β = .12, SE = .05, p = .037, supporting hypothesis 2. However, promotion focus behavior related insignificantly to entrepreneurial intentions, β = −.03, SE = .05, p = .468. Therefore, hypothesis 4 is not supported.

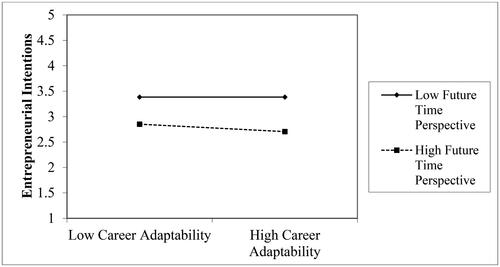

Results of the moderation analysis revealed a significant moderation effect involving future time perspective and career adaptability. Prior to testing the interactive model, the research centred the independent variable (career adaptability) and moderator variables (future time perspective and promotion focus behavior) in line with the procedure suggested by Aiken and West (Citation1991); and created the interactive terms for the analysis. Specifically, the results showed that future time perspective significantly moderated the relationship between career adaptability and entrepreneurial intentions, β = −0.19, SE = .04, p < .001), supporting hypothesis H3. Finally, promotion focus behavior did not significantly moderate the relationship between career adaptability and entrepreneurial intentions, β = −.02, SE = .07, p = .723). Thus, the result supports hypothesis H5.

To provide meaningful interpretation of the moderation hypotheses, the study conducted simple slope analysis using the ± 1 standard deviation above and below the mean procedure, recommended by Aiken and West (Citation1991). This approach allowed the study to test as well as determine the level of the moderator(s) at which the predictor relates significantly to the criterion variable. As depicted in , at a lower level of future time perspective, career adaptability related more significantly and positively to entrepreneurial intentions, β = .48, SE = .05, p < .001, but no significant relationship was found at a higher level of future time perspective, β = .13, SE = .07, p = .140.

5. Discussion

Although previous studies show that career adaptability fosters entrepreneurial intentions, studies of this association in the African context is scarce, and importantly, the extent to which motivational variables such as future time perspective and promotion focus behavior might influence relation between career adaptability and entrepreneurial intentions has received little attention in the field of entrepreneurship. Specifically, in this study, the research aimed to contribute to the scarcity of studies on the relationship between career adaptability and entrepreneurial intention (Zhang et al., Citation2024), test the main effects of two motivational phenomena: future time perspective and promotion focus behavior on entrepreneurial intentions; and finally, examine the extent to which the relation between career adaptability and entrepreneurial intentions might be moderated by future time perspective and promotion focus behavior among undergraduate students in the Ghanaian context. Results showed that career adaptability and future time perspective were beneficial in fostering entrepreneurial intentions among students, and that career adaptability related more positively to entrepreneurial intentions at lower levels of future time perspective. Conversely, promotion focus behavior did not relate significantly to entrepreneurial intentions and did not significantly moderate the link between career adaptability and entrepreneurial intentions among undergraduate students in Ghana. Together, the findings were consistent with some of the expectations in the study.

5.1. Theoretical contribution

As expected, career adaptability was beneficial for entrepreneurial intentions. This outcome is consistent with previous studies (Tolentino et al., Citation2014; Zhang et al., Citation2024) showing that individuals high in career adaptability possess important career-related psychosocial resources such as confidence, persistence, and resilience, enabling them overcome threats and obstacles (Bullough et al., Citation2014; Zhao et al., Citation2005) which are inevitable in the entrepreneurial career space. Further, the finding replicates particularly, Tolentino and colleagues’ (2014) and Zhang et al. (Citation2024) studies and highlight that career adaptability is vital for managing career concerns (Creed et al., Citation2009), career success (Tolentino et al., Citation2013; Zacher, Citation2014), high employability (de Guzman & Choi, Citation2013), and job search fit (Guan et al., Citation2013). This empirical result aligns with the career construction theory (Savickas, Citation2013), suggesting that career adaptability resources allow potential entrepreneurs to respond effectively to the ambiguous and dynamic entrepreneurial environment. Also, the development of career resources is important in shaping the intentions of potential entrepreneurs because these psychosocial resources (i.e. concern, control, curiosity, and confidence) would condition and prepare the minds of potential entrepreneurs for the highly competitive and volatile business environment. Therefore, individuals with adaptability resources tend to demonstrate confidence and control over their tasks and activities, which is important for the pursuit of a career in entrepreneurship. Furthermore, the findings also highlight the importance of planning as suggested by the theory of planned because entrepreneurial career is process. The possession of psychosocial resources such as career adaptability would facilitate the planning process for potential entrepreneurs, as it would give them the confidence that they can navigate the entrepreneurial career environment successfully.

The findings also revealed that future time perspective was beneficial for entrepreneurial intentions, suggesting that future time perspective was an important motivating factor in deciding the future career one intends to pursue. This outcome corroborates the theoretical assumption that future time perspective was an important motivational factor facilitating engagement in career-related behaviors including intent to become an entrepreneur (c.f. Carstensen, Citation2006). This finding is in line with the socio-emotional theory, which suggests that future time perspective enables individuals to utilise their time in ways that lead to goal accomplishment (Carstensen, Citation2006). The result is plausible, as it sheds light on previous evidence suggesting that future time perspective engenders proactive career behaviors including entrepreneurial career behavior (Strauss et al., Citation2012), and career planning (Fasbender et al., Citation2019); and facilitates career commitment (Park & Jung, Citation2015). Furthermore, the findings shed light on the importance of time in career planning, particularly entrepreneurial career, with individuals prioritizing that immediate career or employment needs (Carstensen, Citation2006; Lang & Carstensen, Citation2002).

Further, the findings showed that promotion focus behavior had a null effect on entrepreneurial intentions among undergraduate students, contradicting previous studies (Lanaj et al., Citation2012; Neubert et al., Citation2008; Petrou et al., Citation2020). This implies that the self-regulatory behavior of creativity and risk-taking behaviors by students did not have a material impact on potential entrepreneur’s future career intentions. Thus, the result did not align with the self-regulatory theory (Higgins, Citation1997, 1998) argument that promotion focus individuals are capable of transitioning from school to the world of work, managing their own careers including entrepreneurial career. Nevertheless, we argue that the characteristics of a promotion focus individual such as higher levels of self-efficacy, motivation to learn new things in their environment (Lanaj et al., Citation2012), cognitive flexibility, resilience capabilities (Petrou et al., Citation2020); higher levels of creativity (Lanaj et al., Citation2012; Petrou et al., Citation2020) make such individuals potential entrepreneurs. We suggest further investigation into the efficacy of promotion focus behavior in facilitating entrepreneurial intentions in other context, particularly as there are dearth studies on the link. The outcome is plausible, as we observed some validity concerns, which might have affected the results.

Finally, the study showed that not every individual benefit from the positive effect of career adaptability on entrepreneurial intention, suggesting that other motivational factors such as future time perspective and promotion focus were important boundary factors. Indeed, the results support the theoretical assumption (i.e. career construction theory, Savickas, Citation2013) that psychosocial resources including career adaptability do not affect outcomes in the same way (c.f. Savickas & Porfeli, Citation2012). In line with this theoretical assumption, and consistent with the researchers’ expectations, the study found that for those individuals with low future time perspective (i.e. interested in fulfilling immediate future goals such as employment), the simple slope analysis showed that career adaptability relates positively to intent to become an entrepreneur; and for those high in promotion focus (i.e. those interested in maximising career-related gains), career adaptability relates positively to intent to become an entrepreneur. The findings revealed that opened-future time perspective and promotion focus behaviour are important boundary variables in the career adaptability-entrepreneurial intentions relationship. Importantly, the empirical evidence in the current study indicates that career adaptability was associated with increased entrepreneurial intentions for individuals who strive to fulfil their immediate needs (i.e. low future time perspective) compared to those with high future time perspective. Students find employment or career as their immediate goal toward the end of their university education. Thus, the findings align with the socio-emotional theory (Carstensen et al., Citation1999; Carstensen, Citation2006), which suggests that individuals with low future time perspective (i.e. interested in satisfying their immediate future career goal of working for themselves) would respond positively to psychosocial resource, such as career adaptability - showing concern about their future career, ability that they can succeed, control, and explore by showing greater intention to pursue an entrepreneurial career in the immediate future.

Finally, promotion focus behavior did not significantly moderate the relationship between career adaptability and entrepreneurial intentions, suggesting that promotion focus was not a boundary variable in the relationship. This outcome contradicts previous studies (cf. Crowe & Higgins, Citation1997; Hung et al., Citation2018). A possible explanation for this result is that individuals with enormous psychosocial resources (i.e. career adaptability) are conditioned and prepared for the entrepreneurial journey.

5.2. Practical implications

The findings have several practical benefits for students in tertiary institutions, career counsellors and academics interested in entrepreneurship. First, the findings indicate that for students’ low on future time perspective (i.e. those interested in achieving their immediate career goals), career adaptability related more positively to entrepreneurial intentions. As the immediate career goal of students is to find jobs (or create their own businesses), career counsellors need to focus on discouraging procrastinatory behaviors in people as these behaviors might lead to low motivation. In this regard, undergraduate students should understand that transition from school to the world of work requires preparation, and that a better understanding of the unemployment situation in the country might lead them to not procrastinate in terms of their search for, identification, and exploitation of business ideas before they become graduates. This strategic way of thinking would make undergraduate students realise that they do not have much time at their disposal and therefore, need to actively think about employment opportunities before graduation. In addition, counsellors in the field of entrepreneurship should focus on training students to develop adaptability resources, as such resources would enable them cope effectively to the demands of an entrepreneurial environment. Further, this study showed that future time perspective was beneficial for individuals with the intent to become entrepreneurs. Therefore, counsellors interested in developing entrepreneurs should focus on training people on the importance and relevance of time in business, as such perceptions might hinder or facilitate business creation intentions. Again, career counsellors should focus on training tertiary education students to cultivate the habit of demonstrating behaviors that are goal attainment and success oriented, as those behaviors have the potential to lead to the realisation of entrepreneurial goals (Higgins, Citation2006). Finally, the results have implications on pedagogical development and improvement, particularly those relating to the teaching of entrepreneurship in Ghanaian universities. For example, the outcome of the study encourages the need to incorporate psychological and motivational variables, such as self-regulatory focus behaviour (i.e. promotion focus behaviour) and future time perspective as well as career adaptability as drivers of entrepreneurial intentions into entrepreneurial curriculum in Ghanaian universities.

5.3. Limitations and suggestion for future research

Despite the unique contributions made to existing entrepreneurship literature, this study is not without limitations. First, a non-probability sampling strategy, that is, convenience sampling method was employed to select the study participants. Although this sampling method allowed the researchers to administer the survey to participants who satisfied the inclusion criteria (i.e. should be pursuing a four-year degree programme and at least 18 years old etc.), the selected sample was unrepresentative of the population. Therefore, the outcome of the study cannot be generalized to the population. The researchers recommend that future studies should consider (to the extent that it is feasible) a probability sampling method. Second, the significant main and interactive effects do not suggest cause-effect relationship, as our data were collected from a single source. However, we adopted an analytic strategy which potentially reduced the likely effect of individual characteristics on the observed relationships and effects. Also, our final model (model 3 – interactive-effect model) shows slightly lower but significant beta values compared to model 2 (main effect model), an indication that our results could be relied upon for decision-making. Second, because the data were collected once, the opportunity for testing longitudinal and reciprocal relationships was practically not possible. Following these limitations, we suggest that a more robust design that would utilise a multisource approach or collect data on the variables on several occasions should be utilised for purposes of eliminating common method bias and testing stability of relationships overtime, respectively.

6. Conclusion

Our study contributes to the literature on entrepreneurial intentions, showing that two motivational phenomena: future time perspective and promotion focus behavior which have received less attention in the field of entrepreneurship, particularly in the African context, fosters entrepreneurial intentions among undergraduate students; and that an important psychosocial resource such as career adaptability was not beneficial for entrepreneurial intentions under all circumstances. Importantly, the present study seems to suggest that career adaptability fosters entrepreneurial intentions under conditions of low future time perspective and high promotion focus, respectively.

Authors contribution

Anthony Sumnaya Kumasey identified the research gap, formulated the topic and drafted the introduction and background to the study and the implications and critically reviewed the manuscript. Eric Delle developed the hypothesis, contextualized the variables, analyzed the data and also reviewed the manuscript. Atia Alpha Alfa reviewed the literature, and helped with the contextualization of the research variables. Fidelis Quansah beefed-up the data analysis, the hypotheses and discussion sections. Inusah Abdul-Nasiru reviewed literature and proofread the manuscript. Michael Ayine Alpha wrote the methodology, discussed the findings and proofread the manuscript. Linus kekeli Kudo administered the questionnaire, beefed-up the background to the study, wrote the future studies and technically proofread the manuscript. Matthew Brains Kudo administered the questionnaire, data entry and proofread the paper. *All Authors gave their approval for the manuscript to be submitted and have also agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the manuscript.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Anthony Sumnaya Kumasey

Anthony Sumnaya Kumasey is a Senior Lecturer at the University of Professional Studies, Accra-Ghana and a Senior Honorary Fellow at the Global Development Institute of the University of Manchester in the United Kingdom, where he obtained his PhD in Development Policy and Management. His general interests are in Ethics and Leadership, Public Administration and Management, Human Resources Management, Organizational Behaviour, Entrepreneurship and Public Policy. His publications have appeared in top-tier journals, including the International Review of Administrative Sciences (IRAS), International Journal of Public Sector Management (IJPM) and Development Policy Review (DPR). Anthony has also served as an ad-hoc reviewer for some top-rated journals. Further, Anthony has had extensive administrative and academic experience in Ghanaian and UK universities.

Eric Delle

Eric Delle holds PhD in Work and Organisational Psychology from the Macquarie University, Australia. He is currently a Lecturer at the Department of Psychology, University of Ghana. Eric’s research interest include proactivity at work, corporate social responsibility, work design, career crafting and adaptability, work characteristics and well-being at work. His publications have appeared in top tier journals, including the International Review of Administrative Sciences (IRAS), Journal of Career Development, and Journal of Organisational Effectiveness: People and Places. Eric serves as an ad-hoc reviewer for top-tier journals such as Journal of Vocational Behavior and Academy of Management Journal.

Atia Alpha Alfa

Atia Alpha Alfa is a lecturer at the University of Professional Studies, Accra (UPSA), Ghana. He holds a Master of Business Administration (Marketing) from the University of Ghana (UG) and a Master of Arts in Peace and Development Studies from the University of Cape Coast (UCC), Ghana. He is currently a final year PhD candidate in the Ghana Institute of Management and Public Administration (GIMPA). His research interests include corporate social responsibility, marketing strategy, corporate reputation, customer citizenship behaviour and organisational management.

Inusah Abdul-Nasiru

Inusah Abdul-Nasiru holds a PhD in Psychology from the University of Ghana where he currently teaches as a Senior Lecturer at the Department of Psychology. His specialty areas are in Industrial and Organisational psychology. Inusah’s research interests include areas bothering on applying psychology to organisational effectiveness, leadership and change management.

Fidelis Quansah

Fidelis Quansah holds a PhD in Marketing and currently an Associate Professor of marketing and the Dean of the Faculty of Management Studies, University of Professional Studies, Accra-Ghana. Fidelis has been teaching marketing related courses close to two decades now. Professor Quansah has over 15 publications to her credit in the area of international business and marketing.

Michael Ayine Alpha

Michael Ayine Alpha holds an MBA and MSc degrees in Finance and Energy Economics. He is currently an Assistant Lecturer in the Department of Finance, University of Professional Studies, Accra, Ghana. Michael has contributed to research in a number of areas including energy forecast and energy security in Ghana. Michael’s dream is to become a top researcher and advocate for Climate Actions

Linus kekeli Kudo

Linus Kekeli Kudo is a lecturer at the Department of Business Administration, University of Professional Studies, Accra, Ghana. Linus holds a PhD in Employee Relation and Human Resource from Griffith University in Australia. Linus’ area of interest includes Human Resource Management, Employee Relations, Public Administration, Public Management, Organisational Behaviour and Supply Chain Management.

Matthew Brains Kudo

Matthew Brains Kudo is a lecturer in the Department of Accounting and Finance at the Ho Technical University, Ho, Ghana. He holds MSc in Accountancy and Finance from Birmingham City University, UK. Currently, he is a PhD candidate in the Department of Financial Governance, University of South Africa (UNISA), South Africa. Matthew’s areas of interest include microfinance, public sector financial governance, audit committee effectiveness, financial Co-operation and entrepreneurship.

References

- Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage.

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Arko-Mensah, J., Darko, J., Nortey, E. N. N., May, J., Meyer, C. G., & Fobil, J. N. (2019). Socioeconomic status and temporal urban environmental change in Accra: A comparative analysis of area-based socioeconomic and urban environmental quality conditions between two time points. Environmental Management, 63(5), 574–582. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-019-01150-1

- Badulescu, D. (2015). Entrepreneurial career perception of master students: Realistic or rather enthusiastic? Annals of the University of Oradea Economic Sciences, XXIV(2), 284–292.

- Badulescu, D., Bungau, C., & Badulescu, A. (2015). Sustainable development through sustainable businesses. An empirical research among master students. Journal of Environmental Protection and Ecology, 16(3), 1101–1108.

- Bal, P. M., de Lange, A. H., Zacher, H., & Van der Heijden, B. I. (2013). A lifespan perspective on psychological contracts and their relations with organizational commitment. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 22(3), 279–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2012.741595

- Boyd, J., & Zimbardo, P. (2005). Time perspective, health, and risk taking. In A. Strathman & J. Joireman (Eds.), Understanding behavior in the context of time: Theory, research, and application (pp. 85–107). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Brenninkmeijer, V., & Hekkert-Koning, M. (2015). To craft or not to craft. Career Development International, 20(2), 147–162. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-12-2014-0162

- Brockner, J., Higgins, E. T., & Low, M. B. (2004). Regulatory focus theory and the entrepreneurial process. Journal of Business Venturing, 19(2), 203–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00007-7

- Bullough, A., Renko, M., & Myatt, T. (2014). Danger zone entrepreneurs: The importance of resilience and self-efficacy for entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(3), 473–499. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12006

- Carstensen, L. L. (1993). January)Motivation for social contact across the life span: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. In Nebraska symposium on motivation 40 (pp. 209–254).

- Carstensen, L. L., & Lang, F. R. (1996). Future time perspective scale [Unpublished manuscript]. Stanford University.

- Carstensen, L. L., Isaacowitz, D. M., & Charles, S. T. (1999). Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. The American Psychologist, 54(3), 165–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.54.3.165

- Carstensen, L. L. (2006). The influence of a sense of time on human development. Science (New York, N.Y.), 312(5782), 1913–1915. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1127488

- Carstensen, L. L., & Lang, F. R. (1996). Future orientation scale [ Unpublished manuscript ]. Stanford University.

- Carstensen, L. L., Isaacowitz, D. M., & Charles, S. T. (1999). Taking time seriously: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. The American Psychologist, 54(3), 165–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.54.3.165

- Creed, P. A., Fallon, T., & Hood, M. (2009). The relationship between career adaptability, person and situation variables, and career concerns in young adults. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 74(2), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2008.12.004

- Crowe, E., & Higgins, E. T. (1997). Regulatory focus and strategic inclinations: promotion and prevention in decision-making. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 69(2), 117–132. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1996.2675

- De Bilde, J., Vansteenkiste, M., & Lens, W. (2011). Understanding the association between future time perspective and self-regulated learning through the lens of self-determination theory. Learning and Instruction, 21(3), 332–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2010.03.002

- de Guzman, A. B., & Choi, K. O. (2013). The relations of employability skills to career adaptability among technical school students. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 82(3), 199–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2013.01.009

- Fasbender, U., Wöhrmann, A. M., Wang, M., & Klehe, U.-C. (2019). Is the future still open? The mediating role of occupational future time perspective in the effects of career adaptability and ageing experience on late career planning. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 111, 24–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.10.006

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (2010). Predicting and changing behavior: A reasoned action approach. Psychology Press.

- Friedman, R. S., & Forster, J. (2001). The effects of promotion and prevention cues on creativity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(6), 1001–1013. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.6.1001

- George, G. (2015). Expanding context to redefine theories: Africa in management research. Management and Organization Review, 11(1), 5–10. https://doi.org/10.1017/mor.2015.7

- Gielnik, M. M., Zacher, H., & Wang, M. (2018). Age in the entrepreneurial process: The role of future time perspective and prior entrepreneurial experience. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(10), 1067–1085. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000322

- Guan, Y., Deng, H., Sun, J., Wang, Y., Cai, Z., Ye, L., Fu, R., Wang, Y., Zhang, S., & Li, Y. (2013). Career adaptability, job search self-efficacy and outcomes: A three-wave investigation among Chinese university graduates. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 83(3), 561–570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2013.09.003

- Hayward, M. L., Forster, W. R., Sarasvathy, S. D., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2010). Beyond hubris: How highly confident entrepreneurs rebound to venture again. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(6), 569–578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.03.002

- Higgins, E. T. (1998). Promotion and prevention: Regulatory focus as a motivational principle. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 30, pp. 1–46). Academic Press.

- Higgins, E. T. (2000). Making a good decision: value from fit. American Psychologist, 55(11), 1217–1230. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.11.1217

- Higgins, E. T. (1997). Beyond pleasure and pain. The American Psychologist, 52(12), 1280–1300. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.52.12.1280

- Higgins, E. T. (2000). Making a good decision: Value from fit. The American Psychologist, 55(11), 1217–1230.

- Higgins, E. T. (2006). Value from hedonic experience and engagement. Psychological Review, 113(3), 439–460. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.113.3.439

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cut-off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Hung, C. C., Huan, T. C., Lee, C. H., Lin, H. M., & Zhuang, W. L. (2018). To adjust or not to adjust in the host country? Perspective of interactionism. Employee Relations, 40(2), 329–345. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-12-2016-0237

- Kautonen, T., van Gelderen, M., & Fink, M. (2015). Robustness of the theory of planned behavior in predicting entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(3), 655–674. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12056

- Kelloway, E. K. (2015). Using Mplus for structural equation modelling. a researcher’s guide (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Kiani, A., Liu, J., Ghani, U., & Popelnukha, A. (2020). Impact of future time perspective on entrepreneurial career intention for individual sustainable career development: The roles of learning orientation and entrepreneurial passion. Sustainability, 12(9), 3864. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12093864

- Kolk, A., & Rivera-Santos, M. (2018). The state of research on Africa in business and management: Insights from a systematic review of key international journals. Business and Society, 57(3), 415–436. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650316629129

- Kooij, D., & Van De Voorde, K. (2011). How changes in subjective general health predict future time perspective, and development and generativity motives over the lifespan. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 84(2), 228–247. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.2010.02012.x

- Korff, J., Biemann, T., & Voelpel, S. C. (2017). Human resource management systems and work attitudes: The mediating role of future time perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(1), 45–67. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2110

- Korff, J., Biemann, T., & Voelpel, S. C. (2017). Human resource management systems and work attitudes: The mediating role of future time perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(1), 45–67. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2110

- Krueger, N. F., & Brazeal, D. V. (1994). Entrepreneurial potential and potential entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 18, 91–104.

- Krueger, N. F., Jr., Reilly, M. D., & Carsrud, A. L. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5-6), 411–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(98)00033-0

- Kvasková, L., & Almenara, C. A. (2021). Time perspective and career decision-making self-efficacy: A longitudinal examination among young adult students. Journal of Career Development, 48(3), 229–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845319847292

- Lanaj, K., Chang, C. H., & Johnson, R. E. (2012). Regulatory focus and work-related outcomes: A review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 138(5), 998–1034. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027723

- Lang, F. R., & Carstensen, L. L. (2002). Time counts: future time perspective, goals, and social relationships. Psychology and Aging, 17(1), 125–139. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.17.1.125

- Liberman, N., Idson, L. C., Camacho, C. J., & Higgins, E. T. (1999). Promotion and prevention choices between stability and change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1135–1145. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1135

- Liñán, F., & Chen, Y. W. (2009). Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 593–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00318.x

- Maggiori, C., Johnston, C. S., Krings, F., Massoudi, K., & Rossier, J. (2013). The role of career adaptability and work conditions on general and professional well-being. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 83(3), 437–449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2013.07.001

- Markman, G. D., & Baron, R. A. (2003). Person–entrepreneurship fit: Why some people are more successful as entrepreneurs than others. Human Resource Management Review, 13(2), 281–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-4822(03)00018-4

- Meoli, A. (2018). A career theory approach on entrepreneurial choice: The case of Italian university graduates [PhD thesis ]. submitted to the University of Italy.

- Miao, C., Humphrey, R. H., Qian, S., & Pollack, J. M. (2018). Emotional intelligence and entrepreneurial intentions: An exploratory meta-analysis. Career Development International, 23(5), 497–512. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-01-2018-0019

- Neneh, B. N. (2019). From entrepreneurial intentions to behavior: The role of anticipated regret and proactive personality. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 112, 311–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.04.005

- Neubert, M. J., Kacmar, K. M., Carlson, D. S., Chonko, L. B., & Roberts, J. A. (2008). Regulatory focus as a mediator of the influence of initiating structure and servant leadership on behavior. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(6), 1220–1233. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012695

- Ouschan, L., Boldero, J. M., Kashima, Y., Wakimoto, R., & Kashima, E. S. (2007). Regulatory focus strategies scale: A measure of individual differences in the endorsement of regulatory strategies. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 10(4), 243–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-839X.2007.00233.x

- Park, I. J., & Jung, H. (2015). Relationships among future time perspective, career and organisational commitment, occupational self-efficacy, and turnover intention. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 43(9), 1547–1561. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2015.43.9.1547

- Park, J., Yang, Y., & Kim, M. (2020). The effect of active senior’s career orientation and educational entrepreneurship satisfaction on entrepreneurship intention and entrepreneurship preparation behavior. Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Venturing and Entrepreneurship, 15(1), 285–301.

- Parker, S. C. (2018). The economics of entrepreneurship. Cambridge University Press.

- Petrou, P., Baas, M., & Roskes, M. (2020). From prevention focus to adaptivity and creativity: The role of unfulfilled goals and work engagement. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 29(1), 36–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2019.1693366

- Petrou, P., Baas, M., & Roskes, M. (2020). From prevention focus to adaptivity and creativity: The role of unfulfilled goals and work engagement. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 29(1), 36–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2016.11.001

- Presbitero, A., & Quita, C. (2017). Expatriate career intentions: Links to career adaptability and cultural intelligence. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 98, 118–126.

- Ramos, K., & Lopez, F. G. (2018). Attachment security and career adaptability as predictors of subjective well-being among career transitioners. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 104, 72–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.10.004

- Savickas, M. L. (1997). Career adaptability: An integrative construct for life-span, life-space theory. Career Development Quarterly, 45, 247–259. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-0045.1997.tb00469.x

- Savickas, M. L. (2013). Career construction theory and practice. In R.W. Lent, & S.D. Brown (Eds.), Career development and counselling: Putting theory and research to work (pp. 147–183, 2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

- Savickas, M. L., & Porfeli, E. J. (2012). Career Adapt-Abilities Scale: Construction, reliability, and measurement equivalence across 13 countries. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(3), 661–673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2012.01.011

- Shane, S., Locke, E. A., & Collins, C. J. (2003). Entrepreneurial motivation. Human Resource Management Review, 13(2), 257–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-4822(03)00017-2

- Sheeran, P. (2002). Intention-behaviour relations: A conceptual and empirical review. European Review of Social Psychology, 12(1), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/14792772143000003

- Shinnar, R. S., Hsu, D. K., Powell, B. C., & Zhou, H. (2018). Entrepreneurial intentions and start-ups: Are women or men more likely to enact their intentions? International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 36(1), 60–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242617704277

- Shirokova, G., Osiyevskyy, O., & Bogatyreva, K. (2016). Exploring the intention–behavior link in student entrepreneurship: Moderating effects of individual and environmental characteristics. European Management Journal, 34(4), 386–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2015.12.007

- Simons, J., Vansteenkiste, M., Lens, W., & Lacante, M. (2004). Placing motivation and future time perspective theory in a temporal perspective. Educational Psychology Review, 16(2), 121–139. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:EDPR.0000026609.94841.2f

- Strauss, K., Griffin, M. A., & Parker, S. K. (2012). Future work selves: How salient hoped-for identities motivate proactive career behaviors. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(3), 580–598. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026423

- Stolarski, M., Bitner, J., & Zimbardo, P. G. (2011). Time perspective, emotional intelligence and discounting of delayed awards. Time & Society, 20(3), 346–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463X11414296

- Tolentino, L. R., Garcia, P. R. J. M., Restubog, S. L. D., Bordia, P., & Tang, R. L. (2013). Validation of the Career Adapt-Abilities Scale and an examination of a model of career adaptation in the Philippine context. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 83(3), 410–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2013.06.013

- Tolentino, L. R., Sedoglavich, V., Lu, V. N., Garcia, P. R. J. M., & Restubog, S. L. D. (2014). The role of career adaptability in predicting entrepreneurial intentions: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 85(3), 403–412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2014.09.002

- Van Gelderen, M., Kautonen, T., & Fink, M. (2015). From entrepreneurial intentions to actions: self-control and action-related doubt, fear, and aversion. Journal of Business Venturing, 30(5), 655–673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2015.01.003

- Van Gelderen, M., Kautonen, T., Vincent, J., & Biniari, M. (2018). Implementation intentions in the entrepreneurial process: Concept, empirical findings, and research agenda. Journal of Small Business Economies, 51(4), 923-941.

- Vaughn, L. A., Baumann, J., & Klemann, C. (2008). Openness to experience and regulatory focus: Evidence of motivation from fit. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(4), 886–894. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2007.11.008

- Ward, A., Hernández-Sánchez, B., & Sánchez-García, J. C. (2019). Entrepreneurial intentions in students from a trans-national perspective. Administrative Sciences, 9(2), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci9020037

- Walsh, J. P. (2015). Organization and management scholarship in and for Africa and the world. Academy of Management Perspectives, 29(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2015.0019

- Zacher, H. (2014). Individual difference predictors of change in career adaptability over time. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 84(2), 188–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2014.01.001

- Zhang, J., Huang, J., & Ye, S. (2024). The impact of career adaptability on college students’ entrepreneurial intentions: a moderated mediation effect of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and gender. Current Psychology, 43(5), 4638–4653. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04632-y

- Zimbardo, P. & Boyd, J. (2008). The time paradox: The new psychology of time that will change your life. Simon and Schuster.

- Zimbardo, P. G., & Boyd, J. N. (2014). Putting time in perspective: A valid, reliable individual-differences metric. In Time perspective theory; review, research and application: Essays in honor of Philip G. Zimbardo (pp. 17–55).

- Zhao, H., Seibert, S. E., & Hills, G. E. (2005). The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1265–1272. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1265