?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Entrepreneurship helps to mainstream the disadvantaged. In order to design policy for the promotion of entrepreneurship among disadvantaged people a proper understanding of entrepreneurship is imperative and cognition has been considered as the best interpreter of entrepreneurship. This study aimed to explore the driving forces and hindrances that influence disadvantaged individuals in their decision to initiate entrepreneurial endeavors. We are using a sample of 1173 people taken from the low-income population of India. The data is analyzed through the use of the Logistic regression technique. The result reflects that attitude, subjective norms, self-efficacy, perceived opportunities and role models encourage Indian disadvantaged to start business. This research contributes to two existing theories: challenge-based entrepreneurship and the theory of planned behavior. It also sheds light on a previously understudied group - disadvantaged entrepreneurs in developing economies. This knowledge can be used by policymakers to create programs that encourage entrepreneurship at the grassroots level.

Reviewing Editor:

1. Introduction

The existing literature primarily focuses on examining how positive circumstances, such as prior entrepreneurial experience, self-efficacy (Schmutzler et al., Citation2019), social capital and education, the ability to recognize opportunities and the presence of a supportive institutional environment, influence entrepreneurship. However, challenge-based entrepreneurship theory suggests that individuals adapt to challenging circumstances, which can foster creativity and work discipline, ultimately driving entrepreneurial endeavors. It recognizes that individuals facing challenging situations encounter both barriers to overcome and strengths to leverage.

In recent times, a fledgling area of research has emerged, focusing on delving into the connection between various personal challenges and the world of entrepreneurship (Morris & Tucker, Citation2023). This research also explores the strategies employed by entrepreneurs to overcome these challenges, as highlighted by researchers. However, our understanding in this field remains limited when it comes to comprehending why individuals facing low socio-economic situations, particularly those with limited incomes, choose to engage in entrepreneurial pursuits in emerging economic contexts. This challenge is especially pertinent within the substantial portion of the population that has been marginalized.

Within the Indian context, economic inequality stands as a pervasive issue, a point underscored. This inequality is often intertwined with social characteristics, as discussed by authors, and is influenced by institutional norms, as revealed by researchers. Consequently, there is a pressing need to unravel the intricate dynamics behind the unconventional entrepreneurial activities undertaken by this outlier segment of the population.

The primary objective of our study is to advance our comprehension of challenge-based entrepreneurship theory, as articulated by some authors. Challenge-based entrepreneurship theory differs from the traditional view of entrepreneurs being driven by opportunity. It proposes that individuals facing various challenges such as economic hardship, social exclusion, or limited resources might be more likely to pursue entrepreneurship. Our research focuses on investigating the factors that exert influence on entrepreneurship among marginalized entrepreneurs operating within emerging economies.

This research contributes to existing knowledge in several significant ways. Firstly, it enhances challenge-based entrepreneurship theory by providing empirical support. In doing so, we conduct a quantitative study involving 1173 marginalized entrepreneurs from low-income backgrounds in India also suggested by Brito et al. (Citation2022), and Pidduck and Clark (Citation2021). Secondly, it extends the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991) by incorporating constructs related to opportunity, role models, and the fear of failure, and tests these constructs in a disadvantaged context of developing economy. As scholars have urged to extend the theory of planned behavior by adding different contextual variables and test this model into different context so as to enhance its applicability and prove its soundness (Arafat et al., Citation2020; Saleem et al., Citation2022). Thirdly, the study contributes to the growing body of research on entrepreneurship by amplifying the voices of disadvantaged entrepreneurs from emerging economies, a group often overlooked and worthy of study (Maalaoui et al., Citation2020). As emphasized by researchers, it is crucial to explore these neglected actors and locations. Lastly, the study carries important implications for policymakers aiming to promote entrepreneurship at the grassroots level. As this research explains what can motivate or discourage people to become entrepreneur.

In this study, we define entrepreneurship as creation of new venture and disadvantaged entrepreneurship as creation of new venture by poor people who face low socio-economic situation.

2. Theoretical underpinnings and hypotheses

To navigate the landscape of entrepreneurial intention among the underprivileged, this study adopts a modified version of a Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991) as its framework. This choice is underpinned by several compelling reasons. First, the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) stands as a widely accepted cognitive model in the field and some recent studies have urged to use it (Santos, Citation2023). Second, it boasts a solid theoretical foundation and has garnered empirical validation through numerous studies (Yasir et al., Citation2023; Pranić, Citation2023; Wang et al., Citation2023; Kim et al., Citation2022; Aliedan et al., Citation2022; Krueger et al., Citation2000; Roy et al., Citation2017). Moreover, Saleem et al. (Citation2022) have extended the theory of planned behavior in the context of disadvantaged and found support for the theory. Remarkably, TPB has accrued over 20,000 citations as per the Web of Science since its publication in 1991, attesting to its applicability in explaining a wide array of planned behaviors, including entrepreneurship. Given its extensive usage by entrepreneurship scholars in the context of entrepreneurial intention, our research aligns with this tradition, focusing on the entrepreneurial intentions of disadvantaged entrepreneurs.

2.1. The theory of planned behavior (TPB)

At the core of the TPB lies the premise that intention precedes every behavior. Intention is the product of an individual’s ability and motivation, signifying their likelihood and determination to engage in the target behavior. This theory posits that the stronger the intention, the higher the likelihood of behavior execution. This linkage between intention and action has been corroborated by numerous studies (Cai et al., Citation2023; Li et al., Citation2023; Starfelt Sutton & White, Citation2016; Albarracín et al., Citation2001; Han & Stoel, Citation2017; Schlaegel & Koenig, Citation2014; Webb et al., Citation2010).

Ajzen (Citation1991) outlines three antecedents of intention: personal attitude, social norms, and PBC (perceived behavioral control). ‘Attitude’ is defined as the extent to which a person assesses or action in question favorably or unfavorably. Intention is contingent upon individuals’ evaluations of the behavior, founded on the expectancy-value theory (Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation1975). This model posits that the subjective assessment of outcomes directly influences attitude in proportion to the strength of belief.

‘Subjective norms’, as defined by Ajzen (Citation1991), refer to the perceived social pressure, whether approval or disapproval, exerted on an individual regarding the pursuit of a particular behavior. Significant referents include family members, significant others, and friends. Subjective norms can either positively or negatively influence intention formation and subsequent action.

Distinguishing TPB from its predecessor, the Theory of Reasoned Action, is the addition of the construct ‘perceived behavioral control’ (PBC). PBC embodies individuals’ perceptions of the easiness or difficulty associated with executing the target behavior. Unlike the locus of control (Rotter, Citation1966), PBC aligns closely with self-efficacy (Bandura, Citation1982). According to Bandura, confidence in one’s ability (Perceived Behavioral Control) exerts a profound influence on behavior performance. It not only impacts activity selection and preparation but also influences effort expended during performance and thought patterns.

The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) has long been employed to investigate entrepreneurial intention, dating back to the seminal works owing to its robust applicability, the TPB has served as a foundational model for numerous studies, often subject to alterations that enhance its efficacy. In this manuscript, we embark on an exploration of the TPB’s cognitive constructs—attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control—augmented by additional factors such as fear of failure, opportunity perception, and role models. This augmentation arises from a wealth of literature (Soam et al., Citation2023; Saleem et al., Citation2022; Tsai et al., Citation2016) revealing significant relationships between these variables and the intention to initiate entrepreneurial endeavors.

Our study represents a fusion of individual cognitive elements, including personal attitude, perceived self-efficacy, fear of failure, and perception of opportunities, with socio-cultural perceptions encompassing perceived social norm. This research delves into the intricate interplay of individual and socio-cultural influences on the intentions of disadvantaged individuals to embark on entrepreneurial journeys. Furthermore, we empirically examine the relationship between demographic characteristics and entrepreneurial intention.

2.2. Hypotheses

As previously discussed, it has been noted in the earlier section that the components of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) – namely, attitude, social norms, and self-efficacy – collectively play a significant role in shaping intention, consequently leading to entrepreneurial actions. It is worth mentioning that the TPB was originally developed and validated in western developed world, and in Indian setting, people possibly will not necessarily share the same mindset and cognition framework as their western counterparts. Moreover, a majority of studies conducted in India have predominantly focused on student samples (Soam et al., Citation2023; Malhotra & Kiran, Citation2023). Given these factors, it is both reasonable and pertinent to revisit extant scholarship and reaffirm the applicability of the TPB when researching disadvantaged groups. To address this, we hypothesize as follow:

H1a: Favourable attitude toward entrepreneurship positively impacts the entrepreneurial intentions of disadvantaged individuals.

H1b: Favourable subjective norms toward entrepreneurship positively impact the entrepreneurial intentions of disadvantaged individuals.

H1c: Belief in one’s own capabilities, as perceived self-efficacy, positively impacts the entrepreneurial intentions of disadvantaged individuals.

2.2.1. Perceived opportunities

Perceived opportunities has been widely recognized and validated as a catalyst for entrepreneurial activities since the groundbreaking research on opportunity and entrepreneurship by Shane and Venkataraman (Citation2000). Numerous studies support the idea that Perceived opportunities serves as a motivating factor for individuals to embark on new business ventures (Ivasciuc & Ispas, Citation2023; McMullen & Shepherd, Citation2006; Shane et al., Citation2003). However, it is important to acknowledge the possibility of an illusionary effect (Baron, Citation1998). According to Ajzen (Citation1991), the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), an individual’s beliefs and attitudes significantly influence their behavior. When presented with a range of opportunities, entrepreneurs assess the feasibility of capitalizing on them. During this evaluation, a positive attitude may grow toward the contemplated intention and behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991). Those individuals who harbor a favorable attitude are more expected to take the initiative to launch a new enterprise (Arafat et al., Citation2019). Numerous other scholars have also conducted tests demonstrating a positive relation between these two constructs (Saleem et al., Citation2022; Honjo, 2015). Based on this foundation, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H2: Perceiving opportunities positively influences the entrepreneurial intentions of disadvantaged individuals.

2.2.2. Fear of failure

From both economic and psychological perspectives, fear of failure exhibits distinctive characteristics (Laussel & Le Breton, Citation1995). The economic viewpoint on anxiety related to failure centers around the inverse relationship between risk-taking behavior and entrepreneurial decision-making (Arenius & Minniti, Citation2005). Researchers have aimed to address this challenging relationship by attempting to reduce the risk perception (Koellinger et al., Citation2013; Wagner, Citation2007; Arenius & Minniti, Citation2005).

From a psychological perspective (Cacciotti & Hayton, Citation2015; Gómez-Araujo & Chandra, Citation2017; Vaillant & Lafuente, Citation2007), failure is seen as a characteristic that arises from the socio-cultural context. It is influenced by ingrained societal norms, such as the belief that failure is a shameful experience, which negatively affects an individual’s attitude (Hessels et al., Citation2011). Scholars have also argued that an individual’s perception of their own capabilities plays a role in their fear of failure (Saleem et al., Citation2022; Tsai et al., Citation2016). Consequently, the fear of encountering unforeseen challenges can reduce the likelihood of starting a new venture. The following theory emerges from the aforementioned debate:

H3: The fear of failure negatively impacts the entrepreneurial intentions of disadvantaged individuals.

2.2.3. Role model

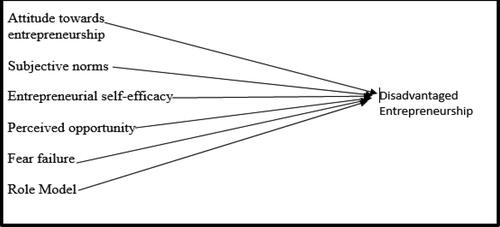

This concept elucidates how humans acquire knowledge and skills by actively participating in activities and observing the actions of others, subsequently emulating them. An individual’s decision to engage in a specific activity is often influenced by the opinions and behaviors of others, either through direct examples or by serving as positive role models (Akerlof & Kranton, Citation2000; Ajzen, Citation1991). It is believed that people acquire knowledge by observing others who they can relate to in a specific context and setting, ideally someone who excels in the field they are interested in and aspire to succeed in – essentially, learning by example or modeling (Arenius & Minniti, Citation2005). This significantly impacts a potential entrepreneur’s career choice and, more specifically, their decision to embark on their entrepreneurial journey (Arenius & Minniti, Citation2005). As highlighted by Van Auken et al. (Citation2006), role models play a pivotal role in boosting individuals’ motivation to become entrepreneurs, as well as enhancing their self-efficacy and confidence. Consequently, entrepreneurial propensity and the chances of engaging in entrepreneurial activities are positively affected (Byrne et al., Citation2019; Krueger et al., Citation2000; Krueger, Citation1993). The conceptual model based on hypothesized relationships was shown in .

H4: Role models exert favourable impact on entrepreneurial intentions of disadvantaged individuals.

3. Methodology

We have employed data acquired and gathered by the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM). GEM, which was founded in 1998 by Babson College and London Business School, is a global organization dedicated to investigating the factors influencing entrepreneurial activity in diverse economies, as outlined by Bosma and Schutjens (Citation2009). This data is sourced from publicly available platforms and already published; no further permission is required for its utilization in research endeavors. Further details regarding the public release can be found from the website (https://www.gemconsortium.org/about/wiki). The Adult Population Survey (APS) of GEM employs an extensive questionnaire to gather data encompassing various cognitive aspects related to entrepreneurship. These data are valuable for analyzing individuals’ inclination and aspiration to initiate their own businesses. To access the APS dataset, we utilized the GEM website (www.gemconsortium.org), which encompasses interviews of 244,470 individuals from various countries taking part in GEM study. In the initial phase, we selected data specifically for India, resulting in 3,360 observations. After filtering out individuals falling into the low-income category, we identified data from 1,173 individuals. For a comprehensive understanding of the data gathering process for the GEM APS, readers can refer to the detailed explanation provided by Reynolds et al. (Citation2005).

Using the GEM data provides certain advantages over gathering fresh data for this study. Numerous studies using GEM data have been conducted and published in reputable journals, attesting to the validity and reliability of this dataset (Schmutzler et al., Citation2019). Apart from documenting the extent of entrepreneurial activity, our research also gathers data on a range of explanatory factors that enrich our comprehension of entrepreneurship from diverse angles, including the domain of entrepreneurship among people with low income (Reynolds et al., Citation2005). Consequently, we hold the view that the GEM dataset is a fitting and highly appropriate resource for our research inquiry. The description of variables is given as under in .

Table 1. Variables description.

3.1. Binary logistic regression model

Logistic regression, a statistical technique employed to evaluate the impact of various predictor variables on a binary (non-metric) dependent variable, has been employed in this research paper. This choice of technique aligns with the research’s aim of predicting and explaining a two-group dichotomous dependent variable. There are similarities between logistic regression and multiple regressions in terms of their variables.

The logistic regression model can be represented as follows:

Logistic regression plays a crucial role in elucidating the connection between independent and dependent variables by determining the optimal model fit. Moreover, it offers the advantage of not requiring assumptions about data distribution (Greene, 2002). There are two compelling reasons for employing logistic regression in this research.

The dependent variable, ‘disadvantaged entrepreneurs,’ exhibits a binary nature.

Most of the independent variables also fall into binary or categorical categories.

4. Results – descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics, as presented in , reveal several key insights. Specifically, 14 percent of the respondents express an intention to initiate their own business, while a significant majority, comprising 61%, view entrepreneurship as a desirable career path. Additionally, 64% of individuals perceive entrepreneurship as a prestigious career choice. Furthermore, 46% of the respondents believe that there are favorable entrepreneurial opportunities available to them, while 38% express confidence in their entrepreneurial abilities to initiate a business venture. However, it is noteworthy that 42% of the respondents harbor concerns that the fear of failure may hinder them from embarking on an entrepreneurial journey. In terms of role models, 21% of the respondents report having entrepreneurial role models who may influence their career choices. On average, the respondents have an age of 35 years.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics.

4.1. Correlation

The correlation analysis, as presented in , offers initial support for the hypotheses formulated in this study. The correlation matrix highlights that all variables, with the exception of risk perception, exhibit positive and statistically significant correlations with the intention to become an entrepreneur. Furthermore, demographic factors also display positive and significant correlations with entrepreneurial intention.

Table 3. Correlations.

4.2. Results: regression

The primary objective of this manuscript was to examine the impact of cognition on the start-up propensity of disadvantaged individuals in India. To achieve this objective and test the hypotheses, logistic regression analysis was con. To ensure the goodness of fit of the model, both the Hosmer and Lemeshow test and the Omnibus goodness-of-fit test were performed. The Omnibus goodness-of-fit test evaluates the null hypothesis, which suggests that all model coefficients are equivalent to zero, is valid, and it contrasts this with the alternative hypothesis, which suggests that at least one parameter is nonzero (Ramos-Rodríguez et al., Citation2012). In our study, the null hypothesis was rejected at the 0.01 significance level, signifying that the model is a suitable fit and aligns with the required criteria (please refer to for details). Additionally, the researchers performed the Hosmer and Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test, where the null hypothesis of model fit is retained if p > .05. As depicted in , the results affirm that the model is well-fitted and suitable for this study.

Table 4. Logit regression.

To investigate the impact of theory of planned behavior determinants on entrepreneurial intention disadvantaged, the first group of hypotheses was put forth. Hypothesis H1a posited that the attitude of the disadvantaged group towards entrepreneurship would positively influence their entrepreneurial intention. Given that the marginal value for this variable is both positive and not more than 0.05, we cannot reject the hypothesis. Furthermore, the odds ratio for this predictor is 1.8, indicating that individuals with an entrepreneurial mindset or an interest in starting their own business are approximately twice as likely to do so compared to the general population.

According to H1b, the ambition of disadvantaged persons to become entrepreneurs is positively and significantly impacted by favorable social norms. We were unable to reject this hypothesis since the marginal effect for this variable is significant and positive. According to the odds value of 1.86 for this predictor, those who view entrepreneurship as a high-status vocation are roughly twice as likely to make a business choice.

Self-efficacy was presented as having a favorable relationship with disadvantaged people’s ambition to start their own business in Hypothesis H1c. The marginal effect for this variable is significant and positive (p .01, Wald Statistics = 7.533), thus we were unable to reject the hypothesis that the perception of knowledge and abilities has a positive influence on entrepreneurial intention. Individuals who possess entrepreneurial self-efficacy are almost twice more likely to embark on new ventures, as indicated by the odds ratio for this variable.

According to hypothesis number two, the perception of opportunities influences the inclination to start a business favorably. The finding supports the assumption that perceived opportunities have a positive impact on start-up (p <.001; so, the hypothesis is accepted). People who see entrepreneurial chances in their region have a 2.1 times higher likelihood of establishing a business than the rest of the community, according to the odds value for the perceived opportunities factor.

Interestingly, the aspirations of individuals from low-income backgrounds to become entrepreneurs are not significantly affected by their fear of failure. As a result, hypothesis H3, which proposed that fear of failure has a negative effect, was rejected due to the lack of a significant marginal effect for this variable.

Role models are seen to encourage risk-taking, according to hypothesis number four. The findings support the hypothesis (p <.001). The odds ratio for this variable shows that the likelihood that someone would start their own business is two times higher among those who have role models. Age and gender, on the other hand, have little to no influence on the startup intentions of underprivileged individuals. Our findings are favorable in that they show a connection between disadvantaged individuals’ inclination to start their own business and their employment position. The odds ratio for this variable reveals that unemployed people are five times more likely than employed people to start their own firm.

Based on the results of the logistic regression analysis, the gender variable was not found to be significant (p-value: 0.43), meaning that gender does not have a statistically significant effect on entrepreneurial intentions when controlling for the other variables in the model. This suggests that, in this particular analysis, being male or female does not significantly influence the likelihood of having entrepreneurial intentions

5. Discussion

Some intriguing findings and a number of surprising outcomes necessitate further debate. The findings demonstrate a positive relationship between attitude toward entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial ambition. This finding aligns with the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) developed by Icek Ajzen (Citation1991). TPB suggests our intentions to perform a behavior are the strongest predictor of whether we actually do it. Among these three key factors influence intentions, attitude explains how much we favor or enjoy the specific behavior (e.g. starting a business). Our finding relates to Attitude. People with a favorable attitude towards entrepreneurship see it as a positive and desirable career path. This positive view translates into a stronger intention to start a business. TPB implies that these individuals are more likely to take concrete steps towards starting their own venture. This finding is supported by Arafat et al. (Citation2019) and Roy et al. (Citation2017). These earlier studies likely found similar results – a positive attitude towards entrepreneurship correlated with a higher likelihood of individuals pursuing this path. In essence, disadvantaged people who view entrepreneurship favorably are more likely to have the intention to become entrepreneurs themselves, which increases the chances of them actually starting a business.

The finding that perceived social status in entrepreneurship positively affects the tendency to start a venture delves into the realm of social influence and motivation. The research suggests that people are more likely to pursue entrepreneurship if they believe it leads to high social status. Social status refers to an individual’s position within a social hierarchy, often associated with prestige, respect, and influence. Studies like those by Khan et al. (Citation2020), Ferreira and Fernandes (Citation2017) and Shiri et al. (Citation2017) also highlight this connection. These studies found that individuals who perceive entrepreneurs as having high social standing are more likely to consider starting their own businesses. The concept of vicarious learning, introduced by Albert Bandura in 1982, sheds light on this phenomenon. Vicarious learning proposes that we learn by observing the experiences of others. In this context, individuals observe successful entrepreneurs receiving societal recognition and respect (high social status). This observation motivates them to pursue entrepreneurship, believing it will lead to similar social rewards. They learn vicariously that entrepreneurship is a path to achieving desired social standing. Future research could explore how other factors like personality traits or role models interact with perceived social status to influence entrepreneurial intentions. Overall, disadvantaged people are more likely to be drawn to entrepreneurship if they believe it will elevate their social standing. By observing successful entrepreneurs, they learn vicariously that entrepreneurship can be a path to social recognition and prestige, thus increasing their motivation to pursue this career path.

The finding that self-efficacy positively influences disadvantaged people’s intention to start businesses highlights the importance of self-belief in overcoming challenges and pursuing entrepreneurial opportunities. Self-efficacy refers to an individual’s belief in their capability to perform a specific task or achieve a desired outcome. In this context, it’s about believing in one’s ability to successfully launch and run a business. Research suggests that high self-efficacy is a crucial factor for anyone considering entrepreneurship. It empowers individuals to navigate challenges, stay motivated, and persevere through difficulties. The finding emphasizes that self-efficacy is particularly impactful for disadvantaged people. Disadvantages can encompass various factors like socioeconomic background, lack of access to resources, or social barriers. The studies by Schmutzler et al. (Citation2019) found similar results – a positive correlation between self-efficacy and entrepreneurial intentions among disadvantaged populations. This strengthens that disadvantaged individuals might face additional hurdles on the path to entrepreneurship. They might have limited access to capital, mentorship, or networks compared to others. High self-efficacy acts as a buffer against these challenges. It fosters resilience, allowing individuals to believe they can overcome obstacles and achieve success despite disadvantages. This self-belief fuels the motivation and confidence needed to take the initiative and pursue their entrepreneurial ventures. It is important to acknowledge that self-efficacy alone might not be enough. Support systems, access to resources, and policies that address specific disadvantages can play a crucial role in enabling entrepreneurial success. Future research could explore how interventions aimed at boosting self-efficacy can be combined with other forms of support to create a more comprehensive path to entrepreneurship for disadvantaged populations. In essence, self-belief, as measured by self-efficacy, is a critical factor for anyone considering entrepreneurship. However, it holds even greater significance for disadvantaged individuals who might face additional challenges. High self-efficacy empowers them to overcome these hurdles and pursue their entrepreneurial dreams.

The finding that opportunity perception, alongside TPB characteristics (attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control), positively influences disadvantaged people’s entrepreneurial intentions in India is a fascinating one. Opportunity perception refers to the ability to identify and assess unmet needs or gaps in the market that can be addressed through a new venture. It’s about recognizing problems and envisioning solutions that can be profitable. For disadvantaged individuals, spotting opportunities can be particularly empowering. It allows them to see a path towards financial independence, improved social mobility, and potentially, overcoming their disadvantages. The Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) suggests that a combination of factors influences entrepreneurial intentions. While TPB characteristics like a positive attitude and self-efficacy are important, opportunity perception adds another crucial layer. Even with a favorable attitude, if someone doesn’t see a viable opportunity, they might be less likely to pursue entrepreneurship. Conversely, a strong perception of opportunity can spark the entrepreneurial spirit, even if other TPB factors are neutral.

The research highlights the specific case of disadvantaged people in India. Studies like Saleem et al. (Citation2022) likely explored similar connections between opportunity perception and entrepreneurship. In India, social capital (networks and relationships) according to Ramos-Rodríguez et al. (Citation2012), intellectual capital (skills and knowledge), and the ‘illusion of control’ (feeling more in charge of one’s destiny) proposed by Keh et al. (Citation2002) might all play a role in how opportunity perception translates to entrepreneurial action.

It is important to consider if there are cultural factors specific to India that make opportunity perception even more critical for disadvantaged entrepreneurs. Future research could explore how government policies or support programs can specifically help disadvantaged populations identify and capitalize on entrepreneurial opportunities.

Opportunity perception, combined with TPB characteristics, is a powerful driver for disadvantaged people in India to pursue entrepreneurship. The unique social and economic context plays a role in shaping how opportunity perception translates into action. By fostering social capital, skills development, and programs that highlight successful entrepreneurs from disadvantaged backgrounds, initiatives can empower more individuals to turn their entrepreneurial dreams into reality.

The analysis of the effect of failure anxiety on entrepreneurial intention reveals an unexpected result, namely that venture creation propensity of underprivileged individuals in India is not affected by failure fear. Although there are few exceptions (Ahmad et al., Citation2014), this finding contradicts the earlier findings (Abu Bakar et al., Citation2017; Noguera et al., Citation2013; Ramos-Rodríguez et al., Citation2012). The failure of this study to discover a meaningful relationship between risk perceptions and intention to become an entrepreneur can be attributed to two factors. First, overconfidence is the cause of the risk perception’s negligible impact. Overconfident individuals are more prone to perceive smaller risks and are more probable to launch a new firm, according to Robinson and Marino (Citation2015). Second, individuals who wish to launch a firm with a little sum of funding may be more risk tolerant since they may believe that if their venture fails, they will be only losing a small amount of money and can handle the loss.

The result confirms the link between entrepreneurial intention and role models. Role models have a favorable impact on the propensity to start a new business, according to the logistic regression analysis. This result conflicts with earlier findings (Ahmad et al., Citation2014). This could be the case because having role models around lowers people’s risk-aversion, which encourages entrepreneurial behavior (Ferreto et al., Citation2018; Byrne et al., Citation2019).

6. Implications

The findings indicate that entrepreneurs who express an interest in initiating their own businesses and perceive entrepreneurship as a prestigious occupation are more inclined to make entrepreneurial decisions. Consequently, it is advisable for the government to implement policies and programs aimed at enhancing the appeal and personal status associated with entrepreneurship, especially among disadvantaged individuals. This could involve measures to grant entrepreneurs social prestige and recognition.

Additionally, we discovered that the possibility of becoming an entrepreneur increases with the perception of entrepreneurial possibilities; therefore, it is advised that the government create programs that can help individuals see opportunities and subsequently start businesses.

Additionally, results suggest that disadvantaged individuals’ inclination to become entrepreneurs is favorably influenced by their level of entrepreneurial self-efficacy; this suggests that being an entrepreneur is not a choice, and that establishing a firm is thus not simple. This can be as a result of the lack of an entrepreneur-friendly atmosphere. Therefore, we recommend that policymakers create laws to foster a hospitable business climate and make it possible for individuals to acquire the skill set required for establishing and maintaining a firm.

The findings also reveal that role models exert a significant influence on likelihood of marginalized individuals embarking on entrepreneurial journeys. Sometimes, those who face disadvantages may possess the skills and abilities but lack the confidence to utilize them effectively. Role models can play a crucial role in boosting their confidence and motivation. Furthermore, we strongly advocate for the promotion of entrepreneurs who began from humble beginnings and achieved success. This recognition will enhance the image and appeal of entrepreneurship among the underprivileged, thereby fostering a climate conducive to new startups. Additionally, our findings indicate that unemployed individuals exhibit greater motivation to initiate their own businesses compared to those who are already employed. Therefore, it is advisable to prioritize entrepreneurship development programs for the unemployed, as they appear to be particularly receptive to such opportunities.

Since gender was not found to be significant in this analysis, it may not be a priority factor to focus on when trying to understand or promote entrepreneurial intentions in this particular context. Instead, efforts could be directed towards enhancing other factors such as attitude towards entrepreneurship, subjective norms, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, perceived opportunity, and role modeling, which were found to be significant predictors in the analysis.

Based on research on factors influencing entrepreneurship, we recommend several policies and programs to make entrepreneurship more attractive. These include programs that provide guidance and resources for identifying unmet needs and assessing market viability. Connecting aspiring disadvantaged entrepreneurs with successful mentors who can offer insights and guidance tailored to their challenges. Workshops and courses teaching essential business skills such as marketing, finance, and management can boost confidence and perceived control. Improving financial literacy empowers individuals to make informed decisions about starting and running a business. Showcasing successful entrepreneurs from disadvantaged backgrounds can inspire others and demonstrate potential success. Providing access to small, low-interest loans can help address resource limitations. Establishing physical or virtual spaces with shared resources, office space, and mentorship can support new ventures. Simplifying business registration processes, reducing regulations, and offering tax breaks can make starting a business less intimidating. Programs and policies should be designed to meet the specific needs of disadvantaged communities. Initiatives that help entrepreneurs build networks and connections can provide access to resources and potential customers. Implementing these policies and programs can create a more supportive environment that encourages disadvantaged individuals to pursue entrepreneurship.

7. Limitations and future research

The study relied on data from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) Adult Population Survey (APS). While GEM data are valuable, they may not capture all facets of entrepreneurial activity, social capital, or human capital. Additionally, the use of dichotomous items in the questionnaire limits the application of advanced statistical techniques like Factor Analysis and Structural Equation Modeling. The study primarily focused on cognitive characteristics, such as attitudes, self-efficacy, and opportunity perception, to understand entrepreneurial intentions. Other critical components like social capital, intellectual capital, and cultural factors were not examined. Future research could explore these aspects to gain a more comprehensive understanding of disadvantaged entrepreneurship. While logistic regression is a valuable tool for analyzing binary dependent variables, it has its limitations. Future research could explore alternative statistical methods to provide a more nuanced analysis of the relationships between variables.

The study suggests that future research should examine various categories of disadvantaged individuals, such as physically challenged people, transient residents, slum dwellers, and peasants. Each group may face unique challenges and opportunities in entrepreneurship, and a more granular analysis can provide valuable insights. Researchers can adopt a multidimensional approach to investigate disadvantaged entrepreneurship. This involves examining a broader set of variables, including social and cultural factors, to gain a comprehensive understanding of the entrepreneurial experiences of marginalized communities. Comparative studies across different regions and countries can shed light on the contextual factors influencing disadvantaged entrepreneurship. Understanding how these factors vary across diverse settings can help tailor policies and programs effectively. Longitudinal studies tracking the entrepreneurial journeys of disadvantaged individuals over time can provide insights into the factors that contribute to their success or challenges. This approach can also help identify critical turning points in their entrepreneurial paths. Research can focus on evaluating the impact of specific policies and programs aimed at promoting disadvantaged entrepreneurship. Assessing the effectiveness of interventions can inform evidence-based policymaking. Complementing quantitative studies with qualitative research can offer a deeper understanding of the motivations, challenges, and strategies employed by disadvantaged entrepreneurs. Qualitative data can provide rich narratives and context to quantitative findings.

While this study contributes valuable insights into the cognitive factors influencing entrepreneurial intentions among disadvantaged individuals in India, there is ample room for further research. By addressing the limitations and exploring the suggested research directions, scholars can contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of disadvantaged entrepreneurship, ultimately guiding policymakers in fostering inclusive economic development.

8. Conclusion

This study aimed to explore the driving forces and hindrances that influence disadvantaged individuals in their decision to initiate entrepreneurial endeavors. We conducted our research on a sample of 1173 participants drawn from the lower-income demographic, sourced through the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM). Our data analysis employed the binary logistic regression technique, well-suited for examining dichotomous dependent variables. The findings illuminated a clear pattern: individuals who exhibited a personal and social inclination toward entrepreneurship, possessed self-assurance in their abilities, demonstrated a keen perception of available opportunities, and had access to role models were notably more inclined to establish their own businesses. This research explains disadvantaged entrepreneurship in a developing economy. It supports the idea that starting a business to address challenges is a key motivator (challenge-based entrepreneurship). It also expands existing theories by including factors like opportunity perception, role models, and fear of failure alongside established models like TPB. By focusing on a neglected group and a specific context, the research adds valuable insights and informs policymakers on how to encourage entrepreneurship at the grassroots level. We recommend that government initiatives focus on nurturing these identified factors to foster entrepreneurial growth within disadvantaged communities. It’s important to note that our study was based on a one-item questionnaire with dichotomous responses, limiting the scope for advanced statistical analyses. Given that disadvantaged entrepreneurship represents a relatively novel area of study, there exists a valuable opportunity for scholars to further theorize and investigate this phenomenon.

Institutional review board statement

Not applicable.

Informed consent statement

Informed consent was not required as the data was obtained from secondary source.

Author contribution statement

Amar Johri, conception and design. Dr. Mohammad Wamique Hisam: Analysis and interpretation of the data; Dr. Asif Khan, the drafting of the paper; Md. Shahfaraz Khan was responsible for revising for intellectual content. Md. Faisal-E-Alam was responsible for data cleaning and tabulation; Dr. Yasir Arafat; Editing; Dr. Zuhaib Ahmad was responsible for research gap identification; Dr. Asma Zaheer developed literature review.

Acknowledgement

We express our gratitude to Mr. Ahmad Hussain for his invaluable copy-editing assistance. The data used in this research is publicly available.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data is available on request from Dr. Yasir Arafat (Author 6).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Amar Johri

Dr. Amar Johri has been an Assistant Professor in the College of Administrative and Financial Sciences at Saudi Electronic University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, since September 2019. He has more than 17 years of academic experience. He obtained his doctorate (PhD) from Graphic Era University, Dehradun, Uttarakhand, India. His research interests include financial services, financial markets, banking, investment, accounting, and general management. He has published around 40 research papers in national and international journals (including Scopus Q1, Q2 indexed journals, Web of Science: SSCI, SCIE, Q1, Q2, Q3 & ESCI journals, ABDC and ABS category journals, and Proceedings of International Conferences of repute) and has presented around 20 research papers in national and international conferences. He has worked on various research projects and is working on a few more. He has been chair of the technical sessions and honored as a chief guest (valedictory session) at the international conference. He delivers and conducts sessions on financial planning, financial literacy, investment decisions, corporate finance, accounting information systems, corporate accounting, and Microsoft Excel and its use in account, finance, and statistics calculations

Mohammed Wamique Hisam

Dr. Mohammed Wamique Hisam is an Assistant Professor in Depertment of Management in College of Commerce and Business Administration in Dhofar University Salalah, Oman. He has been teaching from last twenty one years to MBA, PGDM, Undergraduate student. He Obtained his MBA (International Business) Degree from the FMS Banaras Hindu University Varanasi and Ph. D. In Management from Allahabad, He has co-authored four Book in the field of management. He has also published four back chapters and more than 29 refereed journal research papers in which more than 14 are Scopus indexed paper) in the Management, Marketing and Entrepreneurial area. He has presented more than two dozen papers at national, international and regional management conferences and seminar. He was an editorial member of Scopus management journal Purushartha in India.

Mohammad Asif

Dr. Mohammad Asif is Associate Professor in the department of finance at Saudi Electronics University, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Earlier he has worked as an assistant professor in Aligarh Muslim University and Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi. He completed his Ph.D. in Agricultural Economics & Business Management from Aligarh Muslim University. His area of interest in teaching and research includes Microeconomics, Agricultural Economics, Banking, Managerial Economics, International Economics and Academic writing & research skills.

He has published many research papers in refereed national and international journals and attended various National and international seminar, Conferences and workshops. He has also been involved as a key researcher and an expert in various research projects funded by prominent institution. He has 15 years of teaching experience at graduate and post graduate levels.

Mohammad Shahfaraz Khan

Dr. Mohammad Shahfaraz Khan is the Assistant Professor (Accounting & Finance) in the College of Economics and Business Administration, University of Technology and Applied Sciences, (formerly College of Applied Sciences, Salalah), Sultanate of Oman. He has done Ph.D. from Aligarh Muslim University (AMU), India (2015) and also did his Bachelors in Commerce & Masters in Finance & Control (MFC) from the same university. He is a gold medalist in post-graduation (MFC) and qualified national eligibility test for lecturer ship. He had published several papers in the field of Finance and Accounting and his areas of interest in research is FDI, Stock market, Banking and Finance, Islamic Banking and Behavioral Finance. He can be reached at [email protected] and [email protected] .

Mohd Yasir Arafat

Dr. Mohd Yasir Arafat completed PhD in Entrepreneurship Area from Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh. Currently, he working on several entrepreneurship research projects. He also published a book on Agricultural Entrepreneurship.

Zuhaib Ahmad

Dr. Zuhaib Ahmad has completed Phd and PDF in Business management from Aligarh Muslim University. He is a faculty at Centre of Professional courses, AMU. He is a author in many well-known research papers in the area of international business.

Asma Zaheer

Dr. Asma Zaheer is an Associate Professor at the Department of Marketing, Faculty of Economics and Administration, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah-Saudi Arabia. She received her PhD degree in Marketing. Her research interest includes Service Quality, Digital Marketing, Retailing and Customer Engagement.Published 4 Patents and 32 research papers till 2023 in different international journals including Web of Science (ISI) and SCOPUS.Attended many Faculty Development Programs (FDP) and attained many Professional Certifications to become an effective researcher and faculty.

References

- Abu Bakar, A. R., Ahmad, S. Z., Wright, N. S., & Skoko, H. (2017). The propensity to business startup: Evidence from Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) data in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 9(3), 263–285. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-11-2016-0049

- Ahmad, N. H., Kelantan, M., Nasurdin, A. M., Halim, H. A., & Khadijeh Taghizadeh, D. S. (2014). Selection and peer-review under responsibility of Universiti the pursuit of entrepreneurial initiatives at the “Silver” Age: From the lens of Malaysian silver entrepreneurs selection and peer-review under responsibility of Universiti Malaysia Kelantan. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 129, 305–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.03.681

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Akerlof, G. A., & Kranton, R. E. (2000). Economics and identity. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(3), 715–753. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355300554881

- Albarracín, D., Fishbein, M., Johnson, B. T., & Muellerleile, P. A. (2001). Theories of reasoned action and planned behavior as models of condom use: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 127(1), 142–161. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.127.1.142

- Aliedan, M. M., Elshaer, I. A., Alyahya, M. A., & Sobaih, A. E. E. (2022). Influences of university education support on entrepreneurship orientation and entrepreneurship intention: Application of theory of planned behavior. Sustainability, 14(20), 13097. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142013097

- Arafat, M. Y., Khan, A. M., Saleem, I., Khan, N. A., & Khan, M. M. (2020). Intellectual and cognitive aspects of women entrepreneurs in India. International Journal of Knowledge Management Studies, 11(3), 278. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJKMS.2020.109092

- Arafat, M. Y., Saleem, I., & Dwivedi, A. K. (2019). Understanding entrepreneurial intention among Indian youth aspiring for self-employment. International Journal of Knowledge and Learning, Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331639601_Understanding_entrepreneurial_intention_among_Indian_youth_aspiring_for_self-employment/citations

- Arenius, P., & Minniti, M. (2005). Perceptual variables and nascent entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 233–247. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-005-1984-x

- Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37(2), 122–147. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122

- Baron, R. A. (1998). Cognitive mechanisms in entrepreneurship: Why and when enterpreneurs think differently than other people. Journal of Business Venturing, 13(4), 275–294. Retrieved from https://econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:eee:jbvent:v:13:y:1998:i:4:p:275-294 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(97)00031-1

- Bosma, N., & Schutjens, V. (2009). Mapping entrepreneurial activity and entrepreneurial attitudes in European regions. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 7(2), 191–213. Retrieved from https://ideas.repec.org/a/ids/ijesbu/v7y2009i2p191-213.html https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESB.2009.022806

- Brito, R. P. D., Lenz, A. K., & Pacheco, M. G. M. (2022). Resilience building among small businesses in low-income neighborhoods. Journal of Small Business Management, 60(5), 1166–1201. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2022.2041197

- Byrne, J., Fattoum, S., & Diaz Garcia, M. C. (2019). Role models and women entrepreneurs: entrepreneurial superwoman has her say. Journal of Small Business Management, 57(1), 154–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12426

- Cacciotti, G., & Hayton, J. C. (2015). Fear and entrepreneurship: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 17(2), 165–190. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12052

- Cai, B., Chen, Y., & Ayub, A. (2023). “Quiet the Mind, and the Soul Will Speak”! Exploring the boundary effects of green mindfulness and spiritual intelligence on University students’ green entrepreneurial intention–Behavior link. Sustainability, 15(5), 3895. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15053895

- Ferreira, J. J., & Fernandes, C. I. (2017). The impact of entrepreneurship education programs on student entrepreneurial orientations: Three International Experiences. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-47949-1_20

- Ferreto, E., Lafuente, E., & Leiva, J. C. (2018). Can entrepreneurial role models alleviate the fear of entrepreneurial failure? International Journal of Business Environment, 10(2), 160–173. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBE.2018.095809

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behaviour: An introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233897090_Belief_attitude_intention_and_behaviour_An_introduction_to_theory_and_research

- Gómez-Araujo, E., & Chandra, B. M. (2017). Socio-cultural factors and youth entrepreneurship in rural regions socio-cultural factors and youth entrepreneurship in rural regions. Review of Business Management, 19(64), 200–218. https://doi.org/10.7819/rbgn.v0i0.2695

- Han, T. I., & Stoel, L. (2017). Explaining socially responsible consumer behavior: A meta-analytic review of theory of planned behavior. Journal of International Consumer Marketing, 29(2), 91–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/08961530.2016.1251870

- Hessels, J., Grilo, I., Thurik, R., & van der Zwan, P. (2011). Entrepreneurial exit and entrepreneurial engagement. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 21(3), 447–471. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-010-0190-4

- Ivasciuc, I. S., & Ispas, A. (2023). Exploring the motivations, abilities and opportunities of young entrepreneurs to engage in sustainable tourism business in the mountain area. Sustainability, 15(3), 1956. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031956

- Keh, H. T., Der Foo, M., & Lim, B. C. (2002). Opportunity evaluation under risky conditions: The cognitive processes of entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 27(2), 125–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-8520.00003

- Khan, A. M., Arafat, M. Y., Raushan, M. A., & Saleem, I. (2020). Examining the relevance of intellectual capital in improving the entrepreneurial propensity among Indians. International Journal of Knowledge Management, 16(1), 123–140. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJKM.2020010106

- Khan, A. M., Arafat, M. Y., Raushan, M. A., Saleem, I., Khan, N. A., & Khan, M. M. (2019). Does intellectual capital affect the venture creation decision in India? Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 8(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-019-0106-y

- Khan, M. A., Arafat, M. Y., & Raushan, A. (2019). Measuring the influence of intellectual capital on entrepreneurial intentions: Evidences from India. International Journal of Intelligent Enterprise, 22.

- Kim, M. S., Huruta, A. D., & Lee, C. W. (2022). Predictors of entrepreneurial intention among High School Students in South Korea. Sustainability, 14(21), 14168. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114168

- Koellinger, P., Minniti, M., & Schade, C. (2013). Gender differences in entrepreneurial propensity. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 75(2), 213–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0084.2011.00689.x

- Krueger, N. (1993). The impact of prior entrepreneurial exposure on perceptions of new venture feasibility and desirability. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 18(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879301800101

- Krueger, N. F., Reilly, M. D., & Carsrud, A. L. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5-6), 411–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(98)00033-0

- Laussel, D., & Le Breton, M. (1995). A general equilibrium theory of firm formation based on individual unobservable skills. European Economic Review, 39(7), 1303–1319. Retrieved from https://ideas.repec.org/a/eee/eecrev/v39y1995i7p1303-1319.html https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-2921(94)00092-E

- Li, C., Murad, M., & Ashraf, S. F. (2023). The influence of women’s green entrepreneurial intention on green entrepreneurial behavior through University and social support. Sustainability, 15(13), 10123. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310123

- Maalaoui, A., Ratten, V., Heilbrunn, S., Brannback, M., & Kraus, S. (2020). Disadvantage entrepreneurship: Decoding a new area of research. European Management Review, 17(3), 663–668. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12424

- Malhotra, S., & Kiran, R. (2023). Examining the relationship between entrepreneurial perceived behaviour, intentions, and competencies as catalysts for sustainable growth: An Indian perspective. Sustainability, 15(8), 6617. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086617

- McMullen, J. S., & Shepherd, D. A. (2006). Entrepreneurial action and the role of uncertainty in the theory of the entrepreneur. Academy of Management Review, 31(1), 132–152. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2006.19379628

- Morris, M. H., & Tucker, R. (2023). The entrepreneurial mindset and poverty. Journal of Small Business Management, 61(1), 102–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2021.1890096

- Noguera, M., Alvarez, C., & Urbano, D. (2013). Socio-cultural factors and female entrepreneurship. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 9(2), 183–197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-013-0251-x

- Pidduck, R. J., & Clark, D. R. (2021). Transitional entrepreneurship: Elevating research into marginalized entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business Management, 59(6), 1081–1096. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2021.1928149

- Pranić, L. (2023). What happens to the entrepreneurial intentions of Gen Z in a Crony Capitalist Economy amidst the COVID-19 pandemic? Sustainability, 15(7), 5750. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15075750

- Ramos-Rodríguez, A. R., Medina-Garrido, J. A., & Ruiz-Navarro, J. (2012). Determinants of hotels and restaurants entrepreneurship: A study using GEM data. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 31(2), 579–587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.08.003

- Reynolds, P., Bosma, N., Autio, E., Hunt, S., De Bono, N., Servais, I., Lopez-Garcia, P., & Chin, N. (2005). Global entrepreneurship monitor: Data collection design and implementation 1998-2003. Small Business Economics, 24(3), 205–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-005-1980-1

- Robinson, A. T., & Marino, L. D. (2015). Overconfidence and risk perceptions: Do they really matter for venture creation decisions? International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11(1), 149–168. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-013-0277-0

- Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 80(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0092976

- Roy, R., Akhtar, F., & Das, N. (2017). Entrepreneurial intention among science and technology students in India: extending the theory of planned behavior. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 13(4), 1013–1041. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-017-0434-y

- Saleem, I., Arafat, M. Y., Balhareth, H. H., Hussain, A., & Dwivedi, A. K. (2022). Cognitive aspects of disadvantaged entrepreneurs: Evidence from India. Community Development, 53(4), 429–444. https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330.2021.1972016

- Santos, S. C. (2023). Editor’S note: Poverty, entrepreneurship and opportunity Horizons. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 28(03), 2301002. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1084946723010021

- Schlaegel, C., & Koenig, M. (2014). Determinants of entrepreneurial intent: A meta-analytic test and integration of competing models. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(2), 291–332. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12087

- Schmutzler, J., Andonova, V., & Diaz-Serrano, L. (2019). How context shapes entrepreneurial self-efficacy as a driver of entrepreneurial intentions: A multilevel approach. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 43(5), 880–920. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258717753142

- Shane, S., & Venkataraman, S. (2000). The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. In Entrepreneurship: Concepts, theory and perspective (Vol. 34; pp. 171–184). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-48543-8_8

- Shane, S., Locke, E., & Collins, C. (2003). Entrepreneurial motivation. [Articles and chapters]. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/articles/830

- Shiri, N., Shinnar, R. S., Mirakzadeh, A. A., & Zarafshani, K. (2017). Cultural values and entrepreneurial intentions among agriculture students in Iran. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 13(4), 1157–1179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-017-0444-9

- Soam, S. K., Rathore, S., Yashavanth, B. S., Dhumantarao, T. R., S, R., & Balasani, R. (2023). Students’ perspectives on entrepreneurship and its intention in India. Sustainability, 15(13), 10488. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151310488

- Starfelt Sutton, L. C., & White, K. M. (2016). Predicting sun-protective intentions and behaviours using the theory of planned behaviour: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychology & Health, 31(11), 1272–1292. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2016.1204449

- Tsai, K. H., Chang, H. C., & Peng, C. Y. (2016). Extending the link between entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intention: A moderated mediation model. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 12(2), 445–463. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-014-0351-2

- Vaillant, Y., & Lafuente, E. (2007). Do different institutional frameworks condition the influence of local fear of failure and entrepreneurial examples over entrepreneurial activity? Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 19(4), 313–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985620701440007

- Van Auken, H., Stephens, P., Fry, F. L., & Silva, J. (2006). Role model influences on entrepreneurial intentions: A comparison between USA and Mexico. The International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 2(3), 325–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-006-0004-1

- Wagner, J. (2007). Exports and productivity: A survey of the evidence from firm-level data. The World Economy, 30(1), 60–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9701.2007.00872.x

- Wang, X. H., You, X., Wang, H. P., Wang, B., Lai, W. Y., & Su, N. (2023). The effect of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention: Mediation of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and moderating model of psychological capital. Sustainability, 15(3), 2562. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032562

- Webb, T. L., Sniehotta, F. F., & Michie, S. (2010). Using theories of behaviour change to inform interventions for addictive behaviours. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 105(11), 1879–1892. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03028.x

- Yasir, N., Babar, M., Mehmood, H. S., Xie, R., & Guo, G. (2023). The environmental values play a role in the development of green entrepreneurship to achieve sustainable entrepreneurial intention. Sustainability, 15(8), 6451. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15086451