?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Women have been identified as critical actors for sustainable entrepreneurship. This study aims to assess women’s ecopreneur intentions by employing the theory of planned behavior. Survey data was collected from 158 females in Indonesia’s small and medium enterprises (SMEs) sector. The results of partial least square-structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) revealed that self-efficacy and environmental awareness positively impact sustainable entrepreneurial inclinations. Aside from this, these findings indicate that green entrepreneurial motivation plays a vital role in mediating the relationship between self-efficacy, ecological awareness, and the tendency to develop environmentally friendly enterprises. Surrounded by the COVID-19 outbreak, this study implied that the pandemic significantly influences green entrepreneurship self-efficacy and natural consciousness among businesswomen. The results of studies advance the academic debate on the contribution of women in inclusive and sustainable development. Further, it could assist planners and policymakers in strengthening women entrepreneurs’ sustainable business models that allow them to capture opportunities and shape their post-pandemic futures.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

1. Introduction

In latest decades, ecological problems have become a global concern. Environmental issues, such as climate change, water contamination, waste disposal, and resource scarcity, all of which have significantly impacted business and industrial activities (Geng et al., Citation2017). Risen awareness of ecological concerns has forced businesses to focus more on sustainable production and distribution processes (Muangmee et al., Citation2021). It has also stimulated the rise of sustainable entrepreneurship, a concept that blends sustainable development with entrepreneurship (Farny & Binder, Citation2021). Sustainable entrepreneurship seeks to generate feasible market resolutions and position entrepreneurs as agents of change who recognize and utilize opportunities for sustainable growth. To reach the long-term goals, sustainable entrepreneurship provides market-driven solutions to mitigate ecological deterioration and resolve social unfairness and discrimination (Belz & Binder, Citation2017; Farny, Citation2016). Green entrepreneurship contributes critically to global society’s ability to realize the Sustainable Development Goals, or SDGs (Ashari et al., Citation2021).

In matters of eco-friendly entrepreneurship, women typically exhibit more robust attitudes and commitments compared to men (Braun, Citation2010). They are also likely to be more involved in green development and are rising figures in the field of ecopreneurship (Hechavarría et al., Citation2017; Henry, Citation2020; Manju, Citation2016). Environmental concern is a predominant motivator for women’s participation in green enterprises, often surpassing that observed in their male counterparts (Ahmad, Citation2019). The involvement of female in sustainable projects is beneficial for nature as it enables women to disseminate their ability, knowledge, experience, vision, and spirit within the labor force and increases the possibility of developing policies to promote sustainable programs. This is crucial for attaining the objectives outlined in the SDGs and promoting stable and sustainable economic growth. Nonetheless, empirical data regarding the intentions of female sustainable entrepreneurs in the post-pandemic landscape, particularly within Indonesia, remains scant.

Earlier academic works by Alshebami et al. (Citation2023), Ghodbane and Alwehabie (Citation2023), Robayo-Acuña et al. (Citation2023), and Yasir et al. (Citation2023) have explored related themes, examining sustainable entrepreneurial intention through lenses, such as institutional support, educational frameworks, ecological values, and personal cognitive processes. Predominantly, such inquiries have concentrated on younger demographics. While the literature on green entrepreneurial intentions is extensive, the specific focus on female entrepreneurs remains markedly under-researched. This segment has frequently been overlooked in the discourse surrounding ecological sustainability and development, particularly in the post-outbreak setting. The present study endeavors to bridge this scholarly void, offering a focused exploration into the unique experiences and contributions of female entrepreneurs within the realm of environmental sustainability. Additionally, this study not only expands the geographic scope of research in this field but also contributes original findings on how a global crisis can shape and potentially catalyze women’s ecological awareness and green entrepreneurial self-efficacy, providing a critical understanding of resilience and adaptability in the face of unprecedented challenges.

Adopting the theory of planned behavior (TPB), this research seeks to investigate the main drivers of green entrepreneurial intentions among female entrepreneurs. Specifically, the research endeavors to address the following queries: (1) Does the COVID-19 outbreak exert a positive influence on green entrepreneurial self-efficacy and ecological awareness? (2) Does green entrepreneurial self-efficacy have a positive impact on the propensity toward green entrepreneurial ventures? (3) Does the green entrepreneurs’ motivation mediate the influence of green entrepreneur self-efficacy and their intention to engage in green entrepreneurship? (4) Is there a discernible positive relationship between ecological awareness and the interest in green entrepreneurship? (5) Does an increase in ecological awareness lead to a higher level of interest in green entrepreneurship, driven by green entrepreneurial motivation?

To answer the questions, this study gathers data from women-owned enterprises in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. This study’s results validate Alvarez-Risco et al. (Citation2021) and Shi et al. (Citation2019) findings that self-efficacy and environmental awareness directly and indirectly affect green entrepreneurial intentions through variable motivation. Moreover, the COVID-19 outbreak has greatly transformed female entrepreneurs’ behavior, catalyzing a shift toward more ecologically sustainable business practices. Consequently, this study concurs with the perspective that, within a conducive environment, women-led businesses may emerge as pivotal drivers of growth and progress in developing countries. Also, this study, in particular, provides a unique contribution by interlinking the concept of a sustainable economy, pandemic impact, and gender-related concern.

The subsequent sections of this manuscript are methodically organized to facilitate clarity and coherence. Following this introduction, the ensuing section delineates the research framework and postulates the foundational hypotheses underlying the study. Section 3 comprehensively articulates the methodological approach employed in the research. This is succeeded by Section 4, which presents a synthesis of the empirical findings. The final section is dedicated to examining the implications of these findings, culminating in the study’s conclusions.

2. Literature review

2.1. The theory of planned behavior and social cognitive

This investigation employs the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) and Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) to assess the determinants of green entrepreneurship intentions among female entrepreneurs. TPB posits that an individual’s intent to perform a behavior is informed by their attitudes concerning the behavior, the subjective norms surrounding it, and perceived behavioral control, which drive actual behavior (Ajzen, Citation2002). These constructs collectively form a predictive framework for gauging entrepreneurial inclinations and their motivational underpinnings. Conversely, SCT, as formulated by Bandura (Citation1977), accentuates the dynamic interaction among personal factors, behavioral patterns, and environmental contexts, proposing a model of reciprocal determinism that implicates cognitive elements, such as self-efficacy and observational learning in the development of behavior. The application of these theories enriches the analytical narrative surrounding the psychosocial mechanisms that influence behavior, particularly in the domain of environmentally conscious entrepreneurial pursuits by women.

2.2. COVID-19, environmental awareness, and green entrepreneurial self-efficacy

The COVID-19 endemic is directly related to and ultimately inseparable from environmental issues (Whitmee et al., Citation2015). Researchers have thus highlighted how the threat posed by the outbreak can be used to raise environmental awareness (Forster et al., Citation2020; Helm, Citation2020). Environmental conciseness, which shows individuals’ attention to and understanding of the environmental implications of their behaviors, is widely acknowledged as a critical move in educating society to tackle ecological issues (Ramsey et al., Citation1992). Individuals who possess a strong awareness and understanding of ecological issues are more inclined to conduct in an eco-friendly way (Sekhokoane et al., Citation2017). On the one hand, as wildlife and humans live closer together and interact more intensely, there is a clear link between environmental degradation and zoonotic diseases (i.e. pathogens transmitted from animals to humans) such as COVID-19 (Johnson et al., Citation2020). The constant fear of transmission can lead to stronger collaboration between diverse parties with the express goal of protecting the environment from destruction (Vess & Arndt, Citation2008). The quick proliferation of COVID-19, as well as the pandemic anticipation and mitigation policies implemented in response, have helped entrepreneurs better recognize the principle of natural resource preservation (Wang et al., Citation2021). Indeed, as shown by Rousseau and Deschacht (Citation2020), people’s responsiveness to natural surroundings has also grown amid the epidemic.

Previous studies also implied that the COVID-19 outbreak is linked to self-efficacy (Thartori et al., Citation2021). Within the framework of Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory, self-efficacy emerges as a pivotal construct, reflecting the inherent belief in an individual’s capacity to effectively orchestrate and enact requisite actions for handling future scenarios (Bandura, Citation1977). Such self-belief significantly informs decision-making, effort investment, adversity resilience, and cognitive and emotional processing (Bandura & Wessels, Citation1994). Enhanced self-efficacy correlates with pursuing ambitious objectives, steadfast dedication to these goals, and a proactive stance when encountering challenges. Bandura contends that self-efficacy is cultivated through direct successes, observational learning, persuasive communication, and interpretation of physiological responses, all contributing to the fortification of this personal efficacy belief.

Male and female entrepreneurs both showed a decline in life satisfaction and perceived stress worsened during the crisis. Nevertheless, female entrepreneurs suffered more, most likely because their enterprises were more negatively impacted (Stephan et al., Citation2020). Hong et al. (Citation2021) observed that self-efficacy contributes a vital part in reducing depression during the pandemic. In addition, individuals with a strong sense of self-efficacy are more likely to survive during the covid (Pragholapati, Citation2020). Self-efficacy is a person’s belief in their capacity to tackle complicated challenges in various conditions (Abosede et al., Citation2018). It thus reflects individuals’ assurance in their capacity to manage the motives, behaviors, and social environments. Within the perspective of entrepreneurship, self-efficacy is a psychological construct associated with entrepreneurs’ ability to perform tasks, control their thoughts, and make decisions that impact firms’ performance. As it integrates self-motivation and perception, self-efficacy invariably energizes action (Gielnik et al., Citation2020).

Eco-friendly business is a relatively new area. Dissimilar to conventional entrepreneurship, which is primarily concerned with increasing economic profits, sustainable entrepreneurship is founded on the fundamental notion that entrepreneurs possess the ability to generate economic, social, and ecological value through their business activities (Belz & Binder, Citation2017; Muñoz & Cohen, Citation2018). Green entrepreneurship also refers to the act of creating a new ecological business, which is significantly informed by entrepreneurs’ perceptions of their own self-efficacy and personal capacity (Ajzen, Citation2002). By integrating the framework of sustainable entrepreneurship into self-efficacy, green entrepreneurial self-efficacy may be understood as referring to individuals’ belief in their ability to contribute to solving environmental problems and as reflecting individuals’ belief in their attempts to enhance and protect nature (Chu et al., Citation2021). Relating to that matter and situated by the outbreak background, Wang et al. (Citation2021) suggested that COVID-19 exerted a substantial impact on the self-efficacy of eco-entrepreneurs in China.

Following the previous empirical evidence, this study argues that the advent of COVID-19 has markedly heightened ecological awareness and bolstered sustainable entrepreneurship self-efficacy in female entrepreneurs. This nexus of pandemic-induced consciousness and self-belief in sustainability practices reflects an adaptive pivot in business strategies that align with environmental conservation imperatives (Manolova et al., Citation2020; Wang et al., Citation2021). Female entrepreneurs, historically attuned to societal shifts, have demonstrated significant resilience by recalibrating their enterprises toward eco-friendly models, underpinning a transformative approach in the face of global challenges. This phenomenon has not only amplified their capacity for sustainable business innovation but has also propelled the integration of ecological stewardship into the entrepreneurial ethos. Hence, this research posits the subsequent hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1:

COVID-19 has significantly impacted ecological awareness among female entrepreneurs.

Hypothesis 2:

COVID-19 has significantly impacted sustainable entrepreneurship self-efficacy among female entrepreneurs.

2.3. Green entrepreneurial intentions, self-efficacy, and motivation

Sustainable entrepreneurship inclination is seen as the most powerful predictor of green behavior (Miller et al., Citation2017). Similarly, Bae et al. (Citation2014) argue that intentions and actions are the most valid predictors of planned behavior. Intentions refer to individual states that create decisions, concerns, and interests in taking certain actions (Bird, Citation1988). To understand the entrepreneurship paradox and provide evidence of why people become involved in entrepreneurship, researchers have developed several intention-based models (Kautonen et al., Citation2015; Liñán & Fayolle, Citation2015). The theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) is most commonly applied when predicting intentions, which it understands as ‘an individual’s willingness to acknowledge entrepreneurship as an inclination to start a new enterprise’ (Bae et al., Citation2014). The more significant the intention, the more likely that the responsibility will be accomplished.

Previous scholars have found that entrepreneurial intention is highly impacted by self-efficacy. The better a person’s level of enterprising self-efficacy, the more remarkable that individual’s entrepreneurial inclination (Alvarez-Risco et al., Citation2021; Asimakopoulos et al., Citation2019; Chu et al., Citation2021; Kumar & Shukla, Citation2019; Mei et al., Citation2017). People with significant self-efficacy and entrepreneurial motivation are inclined to start new businesses (Shane et al., Citation2003). The same applies to sustainable entrepreneurship. According to Wang et al. (Citation2021), green entrepreneurial motivation is the key to promoting ecopreneurship. Kirkwood and Walton (Citation2010) identify some aspects that encourage business owners to involve themselves in eco-friendly business, i.e. green values, market opportunities, earning a living, working for oneself, and passion for business.

Further, Lăzăroiu et al. (Citation2020) suggest that the adoption of ecologically responsible practices exhibits a positive correlation with corporate sustainability performance metrics. Through the incorporation of innovative practices rooted in sustainability, corporations have the possibility to reduce the detrimental social and environmental repercussions associated with their operational activities. Meanwhile, Lăzăroiu et al. (Citation2020) emphasize that the implementation of sustainability policies within a business context is associated with a dual economic advantage; it serves to curtail operational costs and concurrently augment the financial yields of organizations. This economic incentive may likely be a significant determinant factor in shaping sustainable entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurs who run green businesses also require a strong commitment, as only then can they utilize their energy as efficiently as possible to conduct business while simultaneously protecting and preserving the environment. Building on this previous research, this study asserts that self-efficacy can predict green business intention and that green entrepreneurial motivation can mediate the link between these variables.

Embarking from earlier scholars’ work, this present study believes that green entrepreneurial self-efficacy is a critical determinant of female ecopreneurs’ intentions, underscoring the belief in their capacity to execute environmentally responsible business practices. This self-efficacy fosters the formation of green intentions and the translation of these intentions into actionable strategies. Moreover, it is posited that green entrepreneurial self-efficacy exerts a significant influence on female ecopreneurs’ intentions by intensifying their green entrepreneurial motivation (Austin & Nauta, Citation2016; Perez-Luyo et al., Citation2023; Sair et al., Citation2023). This motivational impetus encapsulates the drive and persistence required to navigate the complexities of sustainable entrepreneurship. The synergy between self-efficacy and motivation forms a dynamic interplay, propelling women to venture into and thrive in green business. This affirms that self-efficacy is an essential precursor for both the intention and the sustained motivational state necessary for green entrepreneurship. It thus, this study hypothesizes:

Hypothesis 3:

Green entrepreneurial self-efficacy significantly influences female ecopreneurs’ intentions.

Hypothesis 5a:

Green entrepreneurial self-efficacy significantly impacts female ecopreneurs’ intentions through green entrepreneurial motivation.

2.4. Environmental awareness, motivation, and green entrepreneurial intention

Awareness is an ability that enables humans to respect fundamental rights (Partanen-Hertell et al., Citation1999). Ecological consciousness, meanwhile, is a person’s capability to recognize the link between individual actions and the environment and, thus, be willing to participate in environmental activities (Liu et al., Citation2014). Environmental awareness thus correlates positively with individuals’ conscious choice to employ environmentally friendly practices (Partanen-Hertell et al., Citation1999). Individuals’ intention to become ecopreneurs is associated with their attentiveness to purchasing and providing environmentally friendly products by using eco-technology and stuff to prevent the ecosystem from deprivation while simultaneously minimizing or even reducing the lessening of natural resources (Liu et al., Citation2014).

Earlier observations have indicated that environmental responsiveness positively and significantly influences green entrepreneurial intentions. Persons with better environmental awareness are inclined to create green entrepreneurial and become eco-friendly entrepreneurs (Awallia & Famiola, Citation2021; Chu et al., Citation2021; Middermann et al., Citation2020; Sardianou et al., Citation2016; Soomro et al., Citation2020). Entrepreneurs’ personal value orientation also strongly influences their motivation to start an environmentally friendly business; indeed, in many cases, eco-entrepreneurship’ initial goal is to spread ecological values, increase consumer alertness of green expenditure, and reach the goals of sustainable business (Kirkwood & Walton, Citation2010). The realization of environmental values and awareness, therefore, affects the motivation for green expenditure, and this, in turn, affects their behaviors, choices, and even intentions (Wang et al., Citation2021).

Drawing on prior empirical data, this study contends that ecological consciousness is a significant predictor of intentions among female ecopreneurs, reflecting a heightened awareness that motivates action toward environmental sustainability in business practices (Yasir et al., Citation2023). This heightened awareness contributes to the formation of intent, as entrepreneurs with strong ecological consciousness are more likely to pursue green ventures. Additionally, green entrepreneurial motivation emerges as another substantial influencer, turning ecological intention into action. The drive and commitment encompassed by this motivation reinforce the intention to engage in eco-friendly business activities (Wang et al., Citation2021). Moreover, sustainable business motivation serves as a conduit through which ecological consciousness translates into green entrepreneurial intention. Therefore, the proposed hypotheses are as follows:

Hypothesis 4:

Ecological consciousness significantly affects female ecopreneurs’ intentions.

Hypothesis 5:

Green entrepreneurial motivation significantly affects female ecopreneurs’ intentions.

Hypothesis 5b:

Through sustainable business motivation, ecological consciousness significantly affects female entrepreneurs’ green entrepreneurial intention.

2.5. Conceptual model

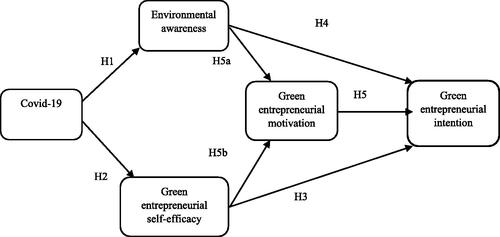

For assessing the green entrepreneurial intention among women-owned businesses, this study applies four elements—COVID-19, two determinants from The Theory of Plan Behaviour, Green entrepreneurial motivation (GEM), Green entrepreneurial self-efficacy (GES), and one determinant from extended TPB, Environmental awareness (EA). To elucidate the interplay between COVID-19, green entrepreneurial self-efficacy, environmental awareness, and sustainable entrepreneurial intentions among women entrepreneurs, with motivation acting as a mediating variable, a conceptual model has been developed, as depicted in .

3. Methodology

3.1. Context of study

This research was conducted in the context of the pandemic in Indonesia, which has been chosen for its timely and critical relevance. The COVID-19 pandemic has drastically altered the business landscape, compelling entrepreneurs to innovate and adapt to new challenges (Okuwhere & Tafamel, Citation2022; Ratten, Citation2021). In Indonesia, a country with a burgeoning entrepreneurial sector, female entrepreneurs have been at the forefront of this adaptive wave (Rahayu et al., Citation2023). Exploring their inclination toward green business practices is particularly important in understanding how environmental sustainability intersects with economic resilience in times of crisis. Furthermore, as the pandemic has heightened awareness of environmental and health issues globally, it has also influenced consumer behavior toward more sustainable products and services (Douglas et al., Citation2020). This shift presents an opportune moment to study the factors that motivate female entrepreneurs in Indonesia to pursue green business models. The observation was conducted in Yogyakarta. The region is known for its innovative approaches to business, particularly among women who often balance traditional roles with entrepreneurial activities. Studying this resilience can yield insights into the adaptive strategies of SMEs during critical times (Purnomo et al., Citation2021; Utomo & Susanta, Citation2021). Moreover, Indonesia’s unique position as a biodiversity-rich nation (Von Rintelen et al., Citation2017), with significant environmental challenges makes it an impactful case study examining how sustainability can be integrated into business strategies during and beyond the pandemic. The findings will enrich international literature on green entrepreneurship by providing insight from emerging nations and, thus, making it a relevant benchmark.

3.2. Design

The research design of this study is anchored in a quantitative approach that utilizes PLS-SEM to analyze the relationships between the identified variables. PLS-SEM is particularly advantageous for its ability to test complex models that include multiple dependent relationships and its capacity to handle latent constructs that are not directly measurable (Hair et al., Citation2021).

3.3. Measures

This current research has a 17-item questionnaire to measure one exogenous variable, three endogenous variables, and one mediating variable. All scales are modified from previously established metrics. The exogenous variable is COVID-19. It refers to respondents’ thoughts about awareness and confidence in adopting environmentally friendly firms during the pandemic which assess the following (Wang et al., Citation2021). Originally, the measurement of this variable was operationalized using a set of five items. However, following a series of validation and reliability tests, the Cronbach’s alpha for four constructs (C2, C3, C4, and C5) had outer loadings below 0.7. As a result, these items were excluded from further analysis (Hair et al., Citation2019). It was determined that only a single item from this set met the criteria for validity and reliability: ‘COVID-19 improves my self-confidence in developing green entrepreneurship’.

‘The endogenous variables are green entrepreneurial self-efficacy, environmental awareness, and green entrepreneurial intention’. Green entrepreneurial self-Efficacy (GES) is assessed by three indicators derived from (Hockerts, Citation2017), i.e. ‘I am confident that by wholeheartedly engaging in this endeavor, I can make a meaningful contribution to the environment’, ‘I possess the ability to discover methods to effectively address environmental issues’, ‘Addressing environmental issues is a contribution that individuals of all backgrounds can make’.

Environmental awareness is referred to the framework developed by Ellen (Citation1994) and Lillemo (Citation2014). This section covered the concepts of environmental protection, humanity’s responsibility to protect the environment, and participation in environmental protection activities. The samples item include: ‘I have a sense of duty to safeguard the environment’ and ‘To safeguard the environment, I feel compelled to decrease energy consumption’. The green entrepreneurial intention consisted of six questions, developed with reference to Liñán and Chen (Citation2009). The questions covered respondents’ perceptions about their readiness, initiative, determination, seriousness, and the best way to open and operate an environmentally friendly enterprise. The sample questions involve: ‘I am fully committed to implementing ecologically sustainable business practices and am willing to take whatever necessary actions to achieve this goal. My goal is to incorporate sustainable business practices into my company’s operations’. The mediating variable (Green entrepreneurial motivation) consists of four items derived from the work of Kai-Jun and Jia-Su (Citation2012). The indicators in this section included, for example, ‘I want to use green entrepreneurship to solve environmental problems’ and ‘I want to use green entrepreneurship to encourage national economic growth’. Respondents provided their answers on a five-point Likert-type scale, which included options from 1, indicating ‘strongly disagree’, to 5, signifying ‘strongly agree’. All the items can be found in detail in the Appendix. Moreover, the study initiated a preliminary investigation by administering an online survey to thirty female entrepreneurs via the ‘Warung Rakyat’ platform, a digital initiative by Universitas Islam Indonesia designed to support SMEs during the pandemic. Following a thorough evaluation of the instrument’s content validity, reliability, and construct validity, the survey was refined. This iterative process resulted in a streamlined final instrument, reducing the number of items from an original 26 items to 17.

3.4. Data collection

This research takes female entrepreneurs who have been operating their businesses in Yogyakarta for at least two years. Utilizing a snowball sampling technique, the digital questionnaire was disseminated to subjects via WhatsApp and email channels. To ensure informed consent from research participants, this study included a detailed explanation within the questionnaire. Participants were provided with comprehensive information about the research objectives, procedures, potential risks, and benefits. Before proceeding, they were advised to read this section thoroughly to make an informed decision about their participation, thereby upholding ethical standards and respecting their autonomy.

Furthermore, before data collection began, this study underwent a thorough ethical review to ensure adherence to the standards of research integrity. Ethical approval was obtained from the Faculty Research Committee at Universitas Islam Indonesia, which fulfills a role analogous to an Institutional Review Board (IRB). The committee thoroughly reviewed the research proposal, methodology, and ethical considerations, providing oversight in alignment with the ethical standards that safeguard the well-being and rights of all participants. The ethical approval for this study was formalized with the reference number 926/DEK/10/Div.URT/IV/2024.

Owing to the absence of exact figures about the population of female business proprietors in the region, the sample size was ascertained following the methodological framework outlined by Lwanga and Lemeshow (Citation1991), as delineated below:

Where: n: sample size; Z: standard normal distribution (95%); p: predicted prevalence = 0.5; d: absolute error.

By the computation mentioned above, the requisite sample size is a minimum of 100 respondents. The researcher collected data from a total of 158 participants, thereby satisfying and exceeding the stipulated sample size criterion. Furthermore, Boomsma (Citation1985) posited that a foundational requirement for conducting PLS-SEM analysis is a sample size not falling below 100. Similarly, Bentler and Chou (Citation1987) articulated that the sample size should be at least quintuple the count of parameters necessitated for estimation. Given that the current study involves 16 parameters and has accrued a sample size of 158, it fulfills the stipulated minimum criteria. Expanding on this premise, Hair et al. (Citation2010) delineated that for more intricate models and constrained sample sizes, an optimal sample size is 10-fold the number of the most extensive set of structural paths aiming at any single construct within the model. In light of this, the collected sample size of 158 in this inquiry approaches this recommended threshold, suggesting sufficiency for robust PLS-SEM analysis. The demographic and professional attributes of the respondents are outlined in .

Table 1. Demographic profile of the informants.

Most responders (79.7%) were under 48, indicating they were still in their prime working years. Education levels were relatively high among informants; around 61.4% had obtained some university education, while the remaining 38.6% had acquired some secondary education. In terms of business, the majority of informants (46.8%) worked in the culinary sector, while a sizeable minority worked in the beauty and fashion (17.7%) and retail (16.5%) sectors; only a few worked in the craft (7%) and other (12%) sectors. At the time of the study, 37.3% of respondents had been in the company for three to five years.

4. Results

The present study employed a separated measurement approach utilizing SmartPLS 4 for data analysis. Initially, a measurement model was established to assess the reliability and validity of the indicators and constructs. Subsequently, a structural model was utilized to evaluate the model’s fit and to conduct hypothesis testing.

4.1. Measurement model analysis

Before modeling using a structural equation, it was first important to assess the reliability and validity of the data. This study used Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM) for data analysis. It measured the internal steadiness of the data through Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR) values ().

Table 2. Constructs’ reliability and convergent validity.

For all sections except green entrepreneurial self-efficacy, Cronbach’s alpha values exceed 0,70, indicating internal steadiness in the data. All constructs’ composite reliability values surpassed 0.70, suggesting the data were internally consistent. Two tests were conducted to measure convergent validity. The first is convergent validity, which describes the degree of correlation between constructs. The second is discriminant validity, which determines if constructs are unconnected to one another. Convergent validity is established when the average variance extracted (AVE) value exceeds 0.50 (Hair et al., Citation2014). In this study, the AVE values of all constructs ranged from 0.686 to 1, thus validating convergent validity (see ). Besides assessing reliability and validity, evaluating the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) is imperative to ascertain multicollinearity among predictors. Burns (Citation2008) posited that a VIF value exceeding 10.0 may signal substantial multicollinearity. The computed VIF values for each construct in this study, all of which fall below the critical value of 10.0, suggest that the constructs are not plagued by collinearity concerns ().

Table 3. Outer VIF values.

The Criterion and the Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratios were utilized to assess the discriminant validity of the dataset (). Validation was substantiated by the square roots of the Average Variance Extracted (AVEs) exceeding the inter-construct correlations, in accordance with the guidelines posited by Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981). Further, HTMT ratios below the threshold of 0.90 corroborated discriminant validity, indicating distinctiveness between the constructs (Henseler et al., Citation2015).

Table 4. Discriminant validity.

Subsequent to the assessment of construct reliability and validity, the model was subjected to a goodness-of-fit test. The Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) serves as an index of fit, quantifying the discrepancy between the correlations predicted by the model and those observed in the data. Hu and Bentler (Citation1998) posit that a Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) value below 0.08 indicates an adequate fit for a model. The empirical findings presented in reveal that the SRMR for the research model stands at 0.06, which is beneath the stipulated threshold. Given that the research model fulfills this criterion, it is deemed appropriate for data analysis.

Table 5. Model fit.

This inquiry also evaluates the predictive power of a PLS_SEM framework, which estimates the model’s capacity to predict the outcomes for dependent constructs from independent ones (Becker et al., Citation2013). The efficacy of the model is gauged by its ability to replicate the process by which data is generated accurately. Empirically, the model’s predictive strength is corroborated by the Q2 values, which are indicative of the model’s competence in reconstructing the observed data with fidelity (Faleskog et al., Citation1998), as demonstrated in . Notwithstanding the Q2 value of zero for one variable (COVID-19), the model’s forecast utility remains intact. This assertion is underpinned by the elevated Q2 values for the remaining variables (EA, GEI, GEM, and GES), which denote a pronounced predictive relevance and, thereby, substantiate the model’s overall sturdiness. The variable characterized by a Q2 value of zero is not devoid of theoretical merit, for it encapsulates critical dimensions that the Q2 metric may not fully encapsulate. This standpoint is empirically validated within the broader literature on SEM predictive power (Hair et al., Citation2017; Henseler & Fassott, Citation2010).

Table 6. Construct cross validated redundancy.

4.2. Structural model analysis

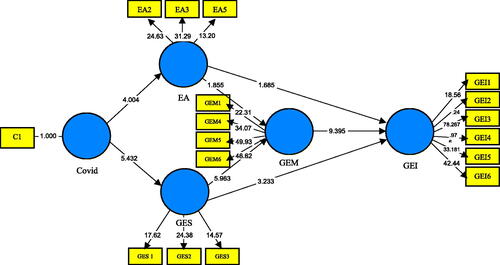

The structural measurement framework was applied to evaluate the model fit and test the hypotheses; the link between all endogenic and exogenic variables is described in and . A structural equation was utilized to evaluate the relationship between respondents’ perceptions of COVID-19, green entrepreneurial self-efficacy, ecological values, and their impact on eco-friendly entrepreneurial intentions, with green entrepreneurial motive as a mediating variable. The values of predictive relevance were used for the model fit. These were ascertained through cross-validated redundancy (Q2), which should be higher than 0 for model precision (Hair et al., Citation2014; Henseler et al., Citation2015). All of the endogenous construct values were >0, indicating model accuracy.

Table 7. Hypotheses testing results.

Table 8. Result of mediating effect.

The hypotheses were subsequently examined using PLS-SEM, with the path coefficient, p-value, and t-statistics values being used to accept or reject hypotheses (). The significance of the link between variables can be observed through the path coefficient values, with path coefficient values near +1 indicating a strong correlation and vice versa (Hair et al., Citation2014). p-Values and t-statistics refer to the acceptance and rejection of the proposed hypotheses. The research model, with its five direct hypotheses and two mediating hypotheses, was then tested using PLS-SEM.

Hypotheses evaluation was conducted using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), with path coefficients, p-values, and t-statistics serving as criteria for hypothesis validation. Path coefficient values close to +1 indicate a robust positive correlation, conversely indicating a strong negative correlation when approaching −1 (Hair et al., Citation2014). The p-values and t-statistics are instrumental in determining the acceptance or rejection of the posited hypotheses. The research framework, comprising five direct and two hypotheses, underwent analytical scrutiny with PLS-SEM.

4.2.1. Direct effect

illustrates that to test the direct effects, reference was made to the normalization coefficient of the structural path and its related significance values made by Smart PLS 4. H1 and H2 show that respondents’ perceptions of COVID-19 have a significant and positive impact on both ecological awareness (β = 0.309, p = 0.000, t = 4.099) and green entrepreneurial self-efficacy (β = 0.391, p = 0.000, t = 5.460). Furthermore, the results of H1 and H2 explain that the impact of COVID-19 on respondents’ green entrepreneurial self-efficacy is greater than its effect on their ecological awareness. H3 and H4 indicate that green entrepreneurial self-efficacy (β = 0.213, p = 0.002, t = 3.169) and environmental awareness (β = 0.106, p = 0.089, t = 1.703) have a positive effect on green entrepreneurial intentions. Thus, the hypothesis is accepted. Finally, H5 shows that green entrepreneurial motivation significantly impacts green entrepreneurial motivation (β = 0.59, p = 0.000, t = 9.350). These statistical data show that motivation is the most significant factor influencing women’s green entrepreneur intention compared to two other variables (environmental awareness and self-efficacy).

4.2.2. Mediating effect

Bootstrapping was used to test the mediating effect (). H5a and H5b indicate that sustainable entrepreneurship motivation significantly mediates the impact of green entrepreneur self-efficacy (β = 0.286, p = 0.000, t = 4.511) and environmental awareness (β = 0.103, p = 0.028, t = 1.912) on entrepreneurial intentions. As such, H5a and H5b are accepted.

5. Discussion

Using the case of women entrepreneurs in Indonesia, the current study provides novel insight into the link between COVID-19, self-efficacy, environmental awareness, and sustainable entrepreneurship inclinations, with motivation as a mediated variable. The results demonstrate that the COVID-19 have had a positive influence on their ecological awareness. In other words, the outbreak has risen ecological attentiveness amongst the female businesses. This is probably due to the influence of measures and contexts intended to mitigate and control the pandemic, such as the increased sense of social accountability of medical personnel and volunteers, as well as the ecological concerns underpinning the COVID-19 pandemic (Severo et al., Citation2021; Wang et al., Citation2021).

The outbreak has exerted a positive influence on women’s self-efficacy in environmental entrepreneurship, indicating enhanced confidence among these business leaders in their initiatives to effectuate environmental enhancement. Since the beginning of the pandemic, women-owned enterprises have gained a robust sense of ecological direction, and social responsibility. These developments are consistent with prior academic findings on the subject; for example, Lieven (Citation2021) and Severo et al. (Citation2021) have shown that the COVID-19 pandemic significantly impacted people’s behavioral transformations, and the pandemic has strengthened individuals’ environmental awareness. A study in Tunisia suggested that the COVID-19 pandemic has positively influenced clients’ conciseness, attitudes toward, and behavior regarding food waste (Jribi et al., Citation2020). Further, Cohen (Citation2020) and Yang et al. (Citation2023) reported that the endemic signs the beginning of a shift toward sustainable consumption and green purchasing behavior. Indeed, COVID-19 has provided a new paradigm for engaging the public in better environmental behavior and enhancing public awareness, both of which will help achieve the long-term goal of environmental sustainability (Lieven, Citation2021; Severo et al., Citation2021). Correspondingly, Chu et al. (Citation2021) found that COVID-19 has strongly and positively affected ecopreneurship self-efficacy. The pandemic has also strengthened the confidence of SMEs to engage in and contribute to green entrepreneurship (Kurniaty et al., Citation2023).

Furthermore, this article has shown that green entrepreneurial self-efficacy indirectly impacts sustainable entrepreneurial intentions through green entrepreneurial motivation (H5a). As Guo (Citation2022) emphasized, green entrepreneurial self-efficacy pertains to the confidence in one’s skills and knowledge to launch and manage environmentally sustainable ventures. When entrepreneurs possess a strong sense of self-efficacy related to green business practices, they are more likely to be motivated to engage in sustainable entrepreneurship. This is because self-efficacy influences the setting of higher goals, persistence in the face of obstacles, and resilience to setbacks (Rayyan et al., Citation2023)—all crucial traits for motivation in the challenging realm of sustainable business. Moreover, motivation in the context of green business is often driven by a desire to achieve environmental goals alongside economic ones (Kirkwood & Walton, Citation2010; Lăzăroiu et al., Citation2020). Entrepreneurs who believe in their ability to make a positive environmental impact through their business practices will likely develop a strong intrinsic motivation to pursue such paths. This green business motivation among female entrepreneurs, fostered by self-efficacy, becomes a mediating factor propelling sustainable business intentions into action. This study empirically validates the argument that motivation is the key to sustainable entrepreneurship (Bohlayer, Citation2023; Sarma et al., Citation2024). Hence, the effect of green business self-efficacy on green entrepreneurial tendency is unconditional.

Previous academic inquiries within varying demographic cohorts have established a positive relationship between self-efficacy and intention to engage in ecologically oriented entrepreneurial activities (Alvarez-Risco et al., Citation2021; Asimakopoulos et al., Citation2019; Chu et al., Citation2021; Kumar & Shukla, Citation2019; Mei et al., Citation2017; Mozahem & Adlouni, Citation2021). The present study has empirically substantiated that an entrepreneur’s level of self-efficacy positively correlates with their entrepreneurial intentions. Consequently, it is pertinent to affirm the significance of green entrepreneurial self-efficacy within female entrepreneurship. This corroborates the research conducted by Hechavarría et al. (Citation2017), which found that female entrepreneurs exhibit a propensity toward environmental ventures, particularly within supportive entrepreneurial ecosystems. Interestingly, their involvement in entrepreneurship is more motivated to fulfill the family’s well-being rather than to obtain wealth (Morales-Alonso et al., Citation2023).

The outcome of this study suggests incentivizing female entrepreneurs to participate in environmentally sustainable businesses is paramount in promoting sustainable development. Corrêa et al. (Citation2024) and Stefan et al. (Citation2021) argued that female entrepreneurs are increasingly recognized as new agents of economic growth and development in developing nations. They bring diverse perspectives and innovations to the business world, which are essential for creative problem-solving and generating a wide array of products and services. Women entrepreneurs often invest a significant portion of their income back into their families and communities, driving education and health improvements, which are foundational for sustainable development (Banu et al., Citation2023; Majumder, Citation2023; Rahman et al., Citation2023). Accordingly, women can be pivotal catalysts for transformation as the global community endeavors to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (Awallia & Famiola, Citation2021; Kiradoo, Citation2023). Given that women have shown greater concern for the future well-being of the planet, their involvement and encouragement in sustainable initiatives are deemed essential (Barrachina Fernández et al., Citation2021).

Scholarly literature has previously established that the environmental consciousness of business proprietors influences their propensity toward engaging in green entrepreneurial activities (Al-Azab & Zaki, Citation2023; Jiang et al., Citation2018; Middermann et al., Citation2020; Soomro et al., Citation2020). Entrepreneurs’ ecological values are fundamental in developing eco-friendly businesses as they serve as the ethical backbone of a company’s environmental strategy and distinguish them from conventional models. When a business is anchored in strong ecological values, it not only aligns its operations with environmental sustainability but also signals to consumers and partners a commitment to responsible stewardship of natural resources. Such values encourage the adoption of practices that minimize ecological footprints, such as waste reduction, recycling, and sustainable sourcing (Trautwein et al., Citation2023; Zacher et al., Citation2023). They foster innovation, leading to the development of products and services that meet customer needs without compromising the planet’s health (Li et al., Citation2023). Consistent with extant scholarly discourse, the current research posits that environmental cognizance exerts a considerable influence on the propensity toward engaging in eco-centric business ventures. This effect manifests either directly or indirectly via the mediation of ecopreneurial motivation (H4 and H5). Therefore, it is posited that individuals exhibiting heightened ecological awareness are predisposed to embark on green entrepreneurial endeavors.

6. Conclusion

The present study constitutes a valuable contribution to the discourse on sustainable entrepreneurship by empirically substantiating the heightened impact of the pandemic on the ecological consciousness and green entrepreneurial self-efficacy of female entrepreneurs. Additionally, it elucidates how self-efficacy bolsters women’s engagement with environmentally responsible entrepreneurial pursuits. Furthermore, the research delineates the significant mediating role of green entrepreneurial motivation in the nexus between environmental entrepreneurial intention, self-efficacy, and ecological awareness.

6.1. Theoretical and practical contribution

This study integrates constructs from the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) and extends it by incorporating elements specific to the context of green entrepreneurship and environmental awareness, providing a nuanced understanding of the factors that drive green entrepreneurial intentions among women. Specifically, this research framework enriches the theoretical discourse by emphasizing how both traditional and novel determinants of entrepreneurial behavior interplay within the unique pressures of the COVID-19 pandemic. As the business landscape evolves in the aftermath of the pandemic, these insights are pivotal in elucidating the imperative for female-led enterprises to innovate their business models toward greater environmental sustainability. Such strategic realignment could not only ensure their resilience within the ecological and economic environment but also provide them with a unique competitive edge. Moreover, by emphasizing female entrepreneurs in the context of a global health crisis, this study carves out a unique niche within the scholarly literature, particularly given the traditionally limited association between women and environmental activism. Thus, the study not only enriches the existing scholarly debate about the antecedents of green entrepreneurship but also underscores the transformational potential of global crises in reshaping entrepreneurial mindsets toward sustainability.

This research can provide valuable insights for policymakers, investors, and entrepreneurs to foster an ecosystem that supports sustainable business growth, particularly in empowering women-led enterprises that prioritize ecological impact alongside economic gains. Further, by understanding the most significant variables of women’s ecopreneurs’ intentions, the study’s results are relevant to assist policymakers in developing a framework to strengthen the ecological enterprise models among women to catch opportunities, mitigate risks, and sculpt their entrepreneurial trajectory.

6.2. Limitations and future study directions

The study presents certain limitations that warrant acknowledgment. Initially, the scope of data collection was confined to a singular province within Indonesia, potentially constraining the broader applicability and generalization of the findings. Future research endeavors would benefit from incorporating a more expansive and diverse geographical cohort, encompassing female entrepreneurs from multiple provinces, or engaging in comparative analyses across distinct regions to cultivate a more comprehensive understanding. Furthermore, the abbreviated time frame of the study inherently restricted the examination to a subset of potential factors influencing women’s intentions to engage in sustainable business practices. Moreover, the data procurement occurred during the pandemic-induced mobility restrictions, which inadvertently led to a constricted respondent pool. Subsequent inquiries should aim to collate and scrutinize data in a post-pandemic context, where accessibility to a wider array of participants may serve to substantiate and fortify the research outcomes.

Additionally, incorporating a multi-faceted analytical framework that includes qualitative assessments could provide richer insights into the motivations and barriers faced by women entrepreneurs. Further research could also explore the impact of varying socio-economic backgrounds and educational levels on green entrepreneurial intentions. Moreover, subsequent research should aim to include a more comprehensive set of variables that influence green entrepreneurial intentions, such as personal values, societal norms, and access to green technologies, to develop a more detailed understanding of the drivers behind sustainable business practices among women.

Informed consent statement

All individual subjects engaged in the study provided informed consent.

Author contributions

The author acknowledges complete accountability for the study’s inception and design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation of findings, as well as the drafting, review, and modification of the paper. The author has also examined and agreed with the manuscript’s final form for publication.

Tables_and_Figures_.docx

Download MS Word (75.6 KB)Acknowledgments

The author expresses gratitude to the Department of Economics, Faculty of Business and Economics, Universitas Islam Indonesia for their cooperation in conducting the research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that provide evidence for the conclusions of this study can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ninik Sri Rahayu

Ninik Sri Rahayu Dr.Phil. Research interest: Green Economics, Islamic Economic and Gender.

References

- Abosede, J., Fayose, J., & Uchenna Eze, B. (2018). Corporate entrepreneurship and international performance of Nigerian banks. Journal of Economics and Management, 32, 5–17. https://doi.org/10.22367/jem.2018.32.01

- Ahmad, A. (2019). Eco-friendly women entrepreneurship in rural areas: A paradigm shift for societal uplift. Jaipuria International Journal of Management Research, 5(2), 41. https://doi.org/10.22552/jijmr/2019/v5/i2/189060

- Ajzen, I. (2002). Perceived behavioral control, self-efficacy, locus of control, and the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32(4), 665–683. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00236.x

- Al-Azab, M. R., & Zaki, H. S. (2023). Towards sustainable development: Antecedents of green entrepreneurship intention among tourism and hospitality students in Egypt. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTI-03-2023-0146

- Alshebami, A., S., Seraj, A. H. A., Elshaer, I. A., Al Shammre, A. S., Al Marri, S. H., Lutfi, A., Salem, M. A., & Zaher, A. M. N. (2023). Improving social performance through innovative small green businesses: Knowledge sharing and green entrepreneurial intention as antecedents. Sustainability, 15(10), 8232. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15108232

- Alvarez-Risco, A., Mlodzianowska, S., García-Ibarra, V., Rosen, M. A., & Del-Aguila-Arcentales, S. (2021). Factors affecting green entrepreneurship intentions in business university students in COVID-19 pandemic times: Case of Ecuador. Sustainability, 13(11), 6447. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116447

- Ashari, H., Abbas, I., Abdul-Talib, A.-N., & Mohd Zamani, S. N. (2021). Entrepreneurship and sustainable development goals: A multigroup analysis of the moderating effects of entrepreneurship education on entrepreneurial intention. Sustainability, 14(1), 431. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010431

- Asimakopoulos, G., Hernández, V., & Peña Miguel, J. (2019). Entrepreneurial intention of engineering students: The role of social norms and entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Sustainability, 11(16), 4314. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11164314

- Austin, M. J., & Nauta, M. M. (2016). Entrepreneurial role-model exposure, self-efficacy, and women’s entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Career Development, 43(3), 260–272. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845315597475

- Awallia, A. F., & Famiola, M. (2021). The model of green behavioural intention among women entrepreneur: A quantitative study. Indonesian Journal of Business and Entrepreneurship. 7(3), 217–266. https://doi.org/10.17358/ijbe.7.3.217

- Bae, T. J., Qian, S., Miao, C., & Fiet, J. O. (2014). The relationship between entrepreneurship education and entrepreneurial intentions: A meta–analytic review. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(2), 217–254. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12095

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.84.2.191

- Bandura, A., & Wessels, S. (1994). Self-efficacy.

- Banu, J., Baral, R., & Kuschel, K. (2023). Negotiating business and family demands: The response strategies of highly educated Indian female entrepreneurs. Community, Work & Family, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2023.2215394

- Barrachina Fernández, M., García-Centeno, M. C., & Calderón Patier, C. (2021). Women sustainable entrepreneurship: Review and research agenda. Sustainability, 13(21), 12047. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132112047

- Becker, J.-M., Rai, A., & Rigdon, E. (2013). Predictive validity and formative measurement in structural equation modeling: Embracing practical relevance.

- Belz, F. M., & Binder, J. K. (2017). Sustainable entrepreneurship: A convergent process model. Business Strategy and the Environment, 26(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.1887

- Bentler, P. M., & Chou, C. P. (1987). 16(1, 78–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124187016001004.

- Bird, B. (1988). Implementing entrepreneurial ideas: The case for intention. The Academy of Management Review, 13(3), 442–453. https://doi.org/10.2307/258091

- Bohlayer, C. (2023). Insights into an action-oriented training program to promote sustainable entrepreneurship. Transforming Entrepreneurship Education, 87–101.

- Boomsma, A. (1985). Nonconvergence, improper solutions, and starting values in lisrel maximum likelihood estimation. Psychometrika, 50(2), 229–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02294248

- Braun, P. (2010). Going green: Women entrepreneurs and the environment. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 2(3), 245–259. https://doi.org/10.1108/17566261011079233

- Burns, R. P. (2008). Business research methods and statistics using SPSS.

- Chu, F., Zhang, W., & Jiang, Y. (2021). How does policy perception affect green entrepreneurship behavior? An empirical analysis from China. Discrete Dynamics in Nature and Society, 2021, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/7973046

- Cohen, M. J. (2020). Does the COVID-19 outbreak mark the onset of a sustainable consumption transition? Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 16(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1080/15487733.2020.1740472

- Corrêa, V. S., Lima, R. M. de, Brito, F. R. S., Machado, M. C., & Nassif, V. M. J. (2024). Female entrepreneurship in emerging and developing countries: A systematic review of practical and policy implications and suggestions for new studies. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 16(2), 366–395. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-04-2022-0115

- Douglas, I., Champion, M., Clancy, J., Haley, D., Lopes de Souza, M., Morrison, K., Scott, A., Scott, R., Stark, M., Tippett, J., Tryjanowski, P., & Webb, T. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic: Local to global implications as perceived by urban ecologists. Socio-Ecological Practice Research, 2(3), 217–228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42532-020-00067-y

- Ellen, P. S. (1994). Do we know what we need to know? Objective and subjective knowledge effects on pro-ecological behaviors. Journal of Business Research, 30(1), 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/0148-2963(94)90067-1

- Faleskog, J., Gao, X., & Shih, C. F. (1998). Cell model for nonlinear fracture analysis–I. Micromechanics calibration. International Journal of Fracture, 89(4), 355–373. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007421420901

- Farny, S. (2016). Revisiting the nexus of entrepreneurship and sustainability-towards an affective and interactive framework for the sustainability entrepreneurship journey.

- Farny, S., & Binder, J. (2021). Sustainable entrepreneurship. In World encyclopedia of entrepreneurship. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics.

- Forster, P. M., Forster, H. I., Evans, M. J., Gidden, M. J., Jones, C. D., Keller, C. A., Lamboll, R. D., Quéré, C. L., Rogelj, J., Rosen, D., Schleussner, C.-F., Richardson, T. B., Smith, C. J., & Turnock, S. T. (2020). Current and future global climate impacts resulting from COVID-19. Nature Climate Change, 10(10), 913–919. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0883-0

- Geng, R., Mansouri, S. A., & Aktas, E. (2017). The relationship between green supply chain management and performance: A meta-analysis of empirical evidences in Asian emerging economies. International Journal of Production Economics, 183, 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2016.10.008

- Ghodbane, A., & Alwehabie, A. (2023). Academic entrepreneurial support, social capital, and green entrepreneurial intention: Does psychological capital matter for young Saudi graduates? Sustainability, 15(15), 11827. https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511827

- Gielnik, M. M., Bledow, R., & Stark, M. S. (2020). A dynamic account of self-efficacy in entrepreneurship. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(5), 487–505. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000451

- Guo, J. (2022). The significance of green entrepreneurial self-efficacy: Mediating and moderating role of green innovation and green knowledge sharing culture. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1001867. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1001867

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis. (7th ed.) Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Hair, J. F.Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., Sarstedt, M., Danks, N. P., Ray, S., Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2021). An introduction to structural equation modeling. In Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R: A workbook (pp. 1–29). Springer.

- Hair, J. F.Jr., Matthews, L. M., Matthews, R. L., & Sarstedt, M. (2017). PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. International Journal of Multivariate Data Analysis, 1(2), 107–123. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMDA.2017.087624

- Hair, J. F.Jr., Sarstedt, M., Hopkins, L., & Kuppelwieser, V. G. (2014). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. European Business Review. 26(2), 106–121.

- Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., Anderson, R., & Tatham, R. (2019). Multivariate data analysis. Cengage Learning.

- Hechavarría, D. M., Terjesen, S. A., Ingram, A. E., Renko, M., Justo, R., & Elam, A. (2017). Taking care of business: The impact of culture and gender on entrepreneurs’ blended value creation goals. Small Business Economics, 48(1), 225–257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9747-4

- Helm, D. (2020). The environmental impacts of the coronavirus. Environmental & Resource Economics, 76(1), 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-020-00426-z

- Henry, C. (2020). Women enterprise policy and COVID-19: Towards a gender-sensitive response. https://eurogender.eige.europa.eu/system/files/web-discussions-files/oecd_webinar_women_entrepreneurship_policy_and_covid-19_summary_report.pdf

- Henseler, J., & Fassott, G. (2010). Testing moderating effects in PLS path models: An illustration of available procedures. In Handbook of partial least squares: Concepts, methods and applications (pp. 713–735). Springer.

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Hockerts, K. (2017). Determinants of social entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(1), 105–130. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12171

- Hong, J., Mreydem, H. W., Abou Ali, B. T., Saleh, N. O., Hammoudi, S. F., Lee, J., Ahn, J., Park, J., Hong, Y., Suh, S., & Chung, S. (2021). Mediation effect of self-efficacy and resilience on the psychological well-being of Lebanese people during the crises of the COVID-19 pandemic and the Beirut explosion. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 733578. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.733578

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3(4), 424–453. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.424

- Jiang, W., Chai, H., Shao, J., & Feng, T. (2018). Green entrepreneurial orientation for enhancing firm performance: A dynamic capability perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production, 198, 1311–1323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.07.104

- Johnson, C. K., Hitchens, P. L., Pandit, P. S., Rushmore, J., Evans, T. S., Young, C. C., & Doyle, M. M. (2020). Global shifts in mammalian population trends reveal key predictors of virus spillover risk. Proceedings of the Royal Society. Biological Sciences, 287(1924), 20192736. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2019.2736

- Jribi, S., Ben Ismail, H., Doggui, D., & Debbabi, H. (2020). COVID-19 virus outbreak lockdown: What impacts on household food wastage? Environment, Development and Sustainability, 22(5), 3939–3955. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-020-00740-y

- Kai-Jun, Z., & Jia-Su, L. (2012). The research on the entrepreneurial motivation of university students based on the achievement goal theory. Studies in Science of Science, 30(8), 1221.

- Kautonen, T., Van Gelderen, M., & Fink, M. (2015). Robustness of the theory of planned behavior in predicting entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(3), 655–674. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12056

- Kiradoo, G. (2023). The role of women entrepreneurs in advancing gender equality and social change. Research Aspects in Arts and Social Studies, 8, 122–131.

- Kirkwood, J., & Walton, S. (2010). What motivates ecopreneurs to start businesses? International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 16(3), 204–228. https://doi.org/10.1108/13552551011042799

- Kumar, R., & Shukla, S. (2019). Creativity, proactive personality and entrepreneurial intentions: Examining the mediating role of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Global Business Review, 23(1), 101–118. 0972150919844395.

- Kurniaty, D., Subagio, A., Yuliana, L., Ridwan, S., & Fairuz, H. (2023). Factors influencing the young entrepreneurs to implement green entrepreneurship (pp. 526–534).

- Lăzăroiu, G., Ionescu, L., Andronie, M., & Dijmărescu, I. (2020). Sustainability management and performance in the urban corporate economy: A systematic literature review. Sustainability, 12(18), 7705. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187705

- Lăzăroiu, G., Ionescu, L., Uță, C., Hurloiu, I., Andronie, M., & Dijmărescu, I. (2020). Environmentally responsible behavior and sustainability policy adoption in green public procurement. Sustainability, 12(5), 2110. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12052110

- Li, H., Li, Y., Sarfarz, M., & Ozturk, I. (2023). Enhancing firms’ green innovation and sustainable performance through the mediating role of green product innovation and moderating role of employees’ green behavior. Economic Research, 36(2), 2142263. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2022.2142263

- Lieven, T. (2021). Has COVID-19 strengthened environmental awareness?

- Lillemo, S. C. (2014). Measuring the effect of procrastination and environmental awareness on households’ energy-saving behaviours: An empirical approach. Energy Policy, 66, 249–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2013.10.077

- Liñán, F., & Chen, Y. (2009). Development and cross–cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 593–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00318.x

- Liñán, F., & Fayolle, A. (2015). A systematic literature review on entrepreneurial intentions: Citation, thematic analyses, and research agenda. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11(4), 907–933. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-015-0356-5

- Liu, X., Vedlitz, A., & Shi, L. (2014). Examining the determinants of public environmental concern: Evidence from national public surveys. Environmental Science & Policy, 39, 77–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2014.02.006

- Lwanga, S. K., & Lemeshow, S. (1991). Sample size determination in health studies: A practical manual. World Health Organization.

- Majumder, S. (2023). Women entrepreneurship in Industrial Revolution 4.0: Opportunities and challenges. In Constraint decision-making systems in engineering (pp. 177–203). CRS Press.

- Manju, T. (2016). Problems and prospects of women ecopreneurs in South Goa. Social Sciences International Research Journal, 3(1), 2395–2544.

- Manolova, T. S., Brush, C. G., Edelman, L. F., & Elam, A. (2020). Pivoting to stay the course: How women entrepreneurs take advantage of opportunities created by the COVID-19 pandemic. International Small Business Journal, 38(6), 481–491. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242620949136

- Mei, H., Ma, Z., Jiao, S., Chen, X., Lv, X., & Zhan, Z. (2017). The sustainable personality in entrepreneurship: The relationship between big six personality, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial intention in the Chinese context. Sustainability, 9(9), 1649. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9091649

- Middermann, L. H., Kratzer, J., & Perner, S. (2020). The impact of environmental risk exposure on the determinants of sustainable entrepreneurship. Sustainability, 12(4), 1534. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12041534

- Miller, D. T., Dannals, J. E., & Zlatev, J. J. (2017). Behavioral processes in long-lag intervention studies. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(3), 454–467. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616681645

- Morales-Alonso, G., Pablo-Lerchundi, I., Ramírez-Portilla, A., & Ordieres-Meré, J. (2023). Entrepreneurial intention through the lens of the Pareto rule: A cross-country study. Cogent Business & Management, 10(3), 2279344. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2279344

- Mozahem, N. A., & Adlouni, R. O. (2021). Using entrepreneurial self-efficacy as an indirect measure of entrepreneurial education. The International Journal of Management Education, 19(1), 100385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2020.100385

- Muangmee, C., Dacko-Pikiewicz, Z., Meekaewkunchorn, N., Kassakorn, N., & Khalid, B. (2021). Green entrepreneurial orientation and green innovation in small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Social Sciences, 10(4), 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10040136

- Muñoz, P., & Cohen, B. (2018). Sustainable entrepreneurship research: Taking stock and looking ahead. Business Strategy and the Environment, 27(3), 300–322. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2000

- Okuwhere, M. P., & Tafamel, A. E. (2022). Coronavirus (COVID-19) and entrepreneurship in Africa: Challenges and opportunities for small and medium enterprises innovation. In Entrepreneurship and post-pandemic future (pp. 7–21). Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Partanen-Hertell, M., Harju-Autti, P., Kreft-Burman, K., & Pemberton, D. (1999). Raising environmental awareness in the Baltic Sea area.

- Perez-Luyo, R., Quiñones Urquijo, A., Del-Aguila-Arcentales, S., & Alvarez-Risco, A. (2023). Green entrepreneurship intention among high school students: A teachers’ view. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1225819. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2023.1225819

- Pragholapati, A. (2020). Self-efficacy of nurses during the pandemic COVID-19. Diunduh Dari Academia.Edu.

- Purnomo, B. R., Adiguna, R., Widodo, W., Suyatna, H., & Nusantoro, B. P. (2021). Entrepreneurial resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic: Navigating survival, continuity and growth. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 13(4), 497–524. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-07-2020-0270

- Rahayu, N. S., Masduki, & Ellyanawati, E. N. (2023). Women entrepreneurs’ struggles during the COVID-19 pandemic and their use of social media. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 12(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-023-00322-y

- Rahman, M. M., Dana, L.-P., Moral, I. H., Anjum, N., & Rahaman, M. S. (2023). Challenges of rural women entrepreneurs in Bangladesh to survive their family entrepreneurship: A narrative inquiry through storytelling. Journal of Family Business Management, 13(3), 645–664. https://doi.org/10.1108/JFBM-04-2022-0054

- Ramsey, J. M., Hungerford, H. R., & Volk, T. L. (1992). Environmental education in the K-12 curriculum: Finding a niche. The Journal of Environmental Education, 23(2), 35–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/00958964.1992.9942794

- Ratten, V. (2021). COVID-19 and entrepreneurship: Challenges and opportunities for small business.

- Rayyan, M., Zidouni, S., Abusalim, N., & Alghazo, S. (2023). Resilience and self-efficacy in a study abroad context: A case study. Cogent Education, 10(1), 2199631. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2023.2199631

- Robayo-Acuña, P. V., Martinez-Toro, G.-M., Alvarez-Risco, A., Mlodzianowska, S., Del-Aguila-Arcentales, S., & Rojas-Osorio, M. (2023). Intention of green entrepreneurship among university students in Colombia. In Footprint and entrepreneurship: Global green initiatives (pp. 259–272). Springer.

- Rousseau, S., & Deschacht, N. (2020). Public awareness of nature and the environment during the COVID-19 crisis. Environmental & Resource Economics, 76(4), 1149–1159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-020-00445-w

- Sair, S. A., Sohail, A., & Sabir, S. A. (2023). Assessing the influence of attitude toward ecopreneurship and subjective norms on ecopreneurship intention: Moderated mediation of self-efficacy and entrepreneurial resilience. International Journal of Management Research and Emerging Sciences, 13(4), 152–168. https://doi.org/10.56536/p9esbr11

- Sardianou, E., Kostakis, I., Mitoula, R., Gkaragkani, V., Lalioti, E., & Theodoropoulou, E. (2016). Understanding the entrepreneurs’ behavioural intentions towards sustainable tourism: A case study from Greece. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 18(3), 857–879. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-015-9681-7

- Sarkis, J., Cohen, M. J., Dewick, P., & Schröder, P. (2020). A brave new world: Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic for transitioning to sustainable supply and production. Resources, Conservation, and Recycling, 159, 104894. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.104894

- Sarma, S., Attaran, S., & Attaran, M. (2024). Sustainable entrepreneurship: Factors influencing opportunity recognition and exploitation. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 25(1), 56–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/14657503221093007

- Sekhokoane, L., Qie, N., & Rau, P.-L. P. (2017). Do consumption values and environmental awareness impact on green consumption in China? (pp. 713–723).

- Severo, E. A., De Guimarães, J. C. F., & Dellarmelin, M. L. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on environmental awareness, sustainable consumption and social responsibility: Evidence from generations in Brazil and Portugal. Journal of Cleaner Production, 286, 124947. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124947

- Shane, S., Locke, E. A., & Collins, C. J. (2003). Entrepreneurial motivation. Human Resource Management Review, 13(2), 257–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-4822(03)00017-2

- Shi, L., Yao, X., & Wu, W. (2019). Perceived university support, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, heterogeneous entrepreneurial intentions in entrepreneurship education: The moderating role of the Chinese sense of face. Journal of Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies, 12(2), 205–230. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEEE-04-2019-0040

- Soomro, B. A., Ghumro, I. A., & Shah, N. (2020). Green entrepreneurship inclination among the younger generation: An avenue towards a green economy. Sustainable Development, 28(4), 585–594. https://doi.org/10.1002/sd.2010

- Stefan, D., Vasile, V., Oltean, A., Comes, C.-A., Stefan, A.-B., Ciucan-Rusu, L., Bunduchi, E., Popa, M.-A., & Timus, M. (2021). Women entrepreneurship and sustainable business development: Key findings from a SWOT–AHP analysis. Sustainability, 13(9), 5298. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095298

- Stephan, U., Zbierowski, P., & Hanard, P.-J. (2020). Entrepreneurship and COVID-19: Challenges and opportunities. KBS COVID-19 Research Impact Papers, 2, 1–30.

- Thartori, E., Pastorelli, C., Cirimele, F., Remondi, C., Gerbino, M., Basili, E., Favini, A., Lunetti, C., Fiasconaro, I., & Caprara, G. V. (2021). Exploring the protective function of positivity and regulatory emotional self-efficacy in time of pandemic COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(24), 13171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182413171

- Trautwein, U., Babazade, J., Trautwein, S., & Lindenmeier, J. (2023). Exploring pro-environmental behavior in Azerbaijan: An extended value-belief-norm approach. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 14(2), 523–543. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIMA-03-2021-0082

- Utomo, H. S., & Susanta, S. (2021). Environmental uncertainty as a moderator of entrepreneurship orientation and innovation capability during the pandemic: A case of written Batik SMEs in Yogyakarta. F1000Research, 10, 844. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.53433.1

- Vess, M., & Arndt, J. (2008). The nature of death and the death of nature: The impact of mortality salience on environmental concern. Journal of Research in Personality, 42(5), 1376–1380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2008.04.007

- Von Rintelen, K., Arida, E., & Häuser, C. (2017). A review of biodiversity-related issues and challenges in megadiverse Indonesia and other Southeast Asian countries. Research Ideas and Outcomes, 3, e20860. https://doi.org/10.3897/rio.3.e20860