Abstract

This study investigates the impact of homophily, influencer social presence, and influencer physical attractiveness on affinity in the beauty and fashion industry through influencer marketing. Trust and loyalty mediating roles are also explored in connection with customer purchase intention. The data was collected from 408 respondents via a digital survey questionnaire and analysed the proposed model using Smart PLS 4.0. Results show a positive influence of homophily, influencer social presence, and influencer physical attractiveness on consumer purchase intention, partially mediated by affinity, trust, and loyalty. The significance of affinity suggests that a strong emotional connection with influencers plays a crucial role in shaping purchasing decisions. The current study contributes to the existing body of knowledge by examining the roles of affinity, trust, and loyalty in homophily, influencer social presence, influencer physical attractiveness, and consumer purchase intention within the beauty and fashion industry—a relatively unexplored area. These insights are valuable for industry practitioners aiming to build trust, establish a strong social presence, and enhance customer loyalty. Thus, this study highlights the pivotal role of affinity and offers practical guidance for influencer marketing strategies that can boost customer purchase intention and foster client loyalty within the fashion and beauty industry.

Introduction

Influencer marketing has emerged as a major force in today’s volatile marketing sense (Zahara et al., Citation2023). Social media platforms have created a vast digital realm where individuals can create content and engage with large audiences, transforming passive consumers into active content creators and distributors (Wang, Citation2021). This transformation has given rise to influencer marketing, a potent channel that leverages the engagement of digital audiences (Tafesse & Wood, Citation2021). Social media influencers (SMIs) have become opinion leaders, welding significant influence over their followers (Leung et al., Citation2022). Recent surveys have reaffirmed the efficacy of influencer marketing, with 90% of marketing practitioners considering influencers as highly effective in engaging consumers (Geyser, Citation2021). Consequently, businesses have integrated influencer marketing into their communication strategies (Campbell & Farrell, Citation2020). In this rapidly evolving marketing landscape, understanding how influencers leverage their status to influence their dedicated followers has become essential (Cam Thuy et al., Citation2023).

Influencer marketing is based on influencers, individuals who gather devoted followers across social media platforms (Ye et al., Citation2021). Social media influencers (SMIs) tend to build their expertise in specific areas. One example is Kritika Khurana, an influential figure in the fashion and entertainment industry, better known as That Boho Girl. Her Instagram followers have reached a whopping 1.8 million. Khurana has established a unique brand identity that emphasizes her boho style, which is reflected in her blog and Outfit of the Day (#OOTD) videos, where she offers makeup and styling tips (Shandy et al., Citation2023). In addition, Kritika has a growing company called Dee Clothing and has received sponsorships from prestigious brands like L’Oreal, Myntra, Knorr, and Pure Sense. Similarly, Parul Gulati, an Indian actress and model, has a considerable following of over 1.6 million on Instagram. Gulati’s possession of Nish Hair, a hair extension brand valued at 50 crores, adds to her diverse professional pursuits. It is crucial to comprehend consumer motives for following a certain social media influencer (SMI), even if they have a substantial number of followers and brand endorsements.

Do individuals follow Kritika solely due to her role as a fashion and lifestyle content creator? Perhaps they seek styling guidance from her, or there might be other factors motivating their followings unrelated to improving their fashion sense. Over the past few decades, leveraging celebrities, including movie stars and Bollywood personalities, for marketing purposes has been a long-standing strategy in the industry (Mitra, Citation2021). However, with the pervasive presence of social media, influencer endorsements have gained significant traction (Appel et al., Citation2020). Recent research indicates that approximately 50% of internet users subscribe to influencer accounts on social media platforms, with a significant 40% of individuals on YouTube expressing trust in the influencer’s recommendations (Digital Marketing Institute, Citation2024; Wang & Huang, Citation2022). Consequently, brands increasingly prioritize collaborations with Social Media Influencers (SMIs), recognizing their ability to effectively engage consumers in the digital realm (Sriram et al., Citation2021). This trend is evident in the substantial incorporation of influencer marketing into marketers’ overall outreach strategies, with its prevalence expected to continue growing in the foreseeable future (Celestino, Citation2023).

Their sense of influencer marketing lies in engaging these followers, fostering a sense of homophily (H), and guiding their purchase intention (PI) through the influencer’s social presence (ISP) (Carmona, Citation2021). Central to this dynamic is the formation of connections between followers and influencers, a topic of paramount significance in contemporary marketing. Influencer marketing has shifted towards enduring strategies emphasizing dependable partnerships and deeper engagements (Ketter & Avraham, Citation2021). The intensity of an influencer’s relationship with their audience has become a crucial factor in planning influencer marketing campaigns (Geyser, Citation2021). Therefore, understanding the persuasive mechanisms underlying the relationship between influencers and their followers is essential, as traditional perspectives fall short of explaining the significance of these bonds in current industry practices.

In practice, influencers can attract large numbers of followers and impact their followers’ knowledge and behaviors (Breves et al., Citation2021). This attribute, known as ‘influencer attachment or affinity (A),’ encapsulates the admiration and positive regard followers have for these digital personalities (Jun & Yi, Citation2020). However, despite the acknowledged significance of influencer physical attractiveness (IPA), there is limited research examining its antecedents and consequences across various factors of influencers (Phuong et al., Citation2023). Investigating the mechanisms behind influencer attractiveness holds immense promise for practitioners and academia. To address this gap, we draw upon attachment theory (Bowlby, Citation1979) and social identity theory (Turner, Citation1981).

The majority of influencer studies focus on existing champions who have high reputations and significant societal impact and can effectively function as recognizable influencers and brand identities (Lee & Lee, Citation2021). However, prominent campaigners frequently begin as ordinary people who provide social media content. Influencers must start from the ground up, putting in time and effort to build their human trademarks (Ouvrein et al., Citation2021). This research explores the drivers of followers’ behavioural intents, specifically customer purchase intention (PI), in the framework of influencer marketing. The study model defines the procedure by which followers’ behavioural intents are formed, capturing the components of influencer homophily (H), influencer social presence (ISP), and influencer physical attractiveness (IPA). It is based on Turner’s (Citation1981) social identity theory and Bowlby’s (Citation1979) attachment theory. The model incorporates the effects of affinity (A) on mediated purchase intention, trust (T), and loyalty (L) on follower-influencer linkages. With the increasing significance of influencer marketing, this study has the ability to deliver a thorough understanding of the intricate associations that exist between influencers and their followers (Jason et al., Citation2023). As we go deeper into the field of influencer marketing, we intend to provide critical insights that will inform more effective methods, improve brand-consumer interactions, and fuel the continued evolution of this revolutionary force in modern marketing. The findings add to the established literature on influencer marketing and propose direction to practitioners looking to implement effective influencer marketing methods.

Literature review

Social Media Influencers (SMI) are the predominant and rapidly expanding industry in marketing, garnering the highest level of attention. The primary goal is to enhance the visibility of products as well as enhance awareness of the brand by leveraging the influence of these individuals who are perceived to be influential (Hugh et al., Citation2022; Ye et al., Citation2021). The influencer marketing literature has garnered substantial scholarly attention, giving rise to multiple research streams dedicated to unraveling the intricate dynamics between influencers and their followers (Song & Kim, Citation2022). However, previous studies have observed the lack of a comprehensive theoretical foundation and a consensus on the conceptualization of SMIs (Malik et al., Citation2023).

Despite the abundance of studies, academia has developed a nuanced understanding of influencer marketing. Research has predominantly focused on identifying traits that enable Social Media Influencers (SMIs) to influence followers. These traits encompass characteristics such as ambition, intelligence, and trustworthiness, as summarized by Audrezet et al. (Citation2020) and Kim and Kim (Citation2021). In a recent study based on the literature review of 154 peer-reviewed research articles, Hudders et al. (Citation2021) summarize multiple attributes that are crucial for SMIs to increase their reach among followers. Primarily relying on qualitative methods, this article discusses SMIs from followers’ perspectives and highlights attributes sought by individuals to connect with SMIs, including trust, honesty, entertainment, and usefulness (Balaban et al., Citation2021). Additionally, they address issues like envy and the erosion of trust and credibility when SMIs promote sponsored products. While existing literature largely emphasizes influencer characteristics and source effects, recent attention has shifted toward understanding the motivations behind influencer-follower relationships (Lee et al., Citation2021). This phenomenon stimulates more investigation into the factors that drive followers to actively participate in social media interactions. Given that the main objective of social media platforms is to promote human interaction, it is crucial to analyze these emotions (Wu & Srite, Citation2021). While researchers have accomplished significant progress in comprehending the intricacies of influential marketing, further investigation is required to investigate followers’ intentions and cultivate ties between social media influencers and their followers.

Scholarly studies have meticulously identified key attributes of influencers that exert significant impacts on follower outcomes. These attributes include influencer physical attractiveness (IPA) (Barta et al., Citation2023), influencer social presence (ISP) (Alboqami, Citation2023), and homophily (H) (Niza Braga & Jacinto, Citation2022). These factors have emerged as essential elements shaping the dynamics of influencer-follower interactions. Another vital research avenue explores the psychological responses evoked in followers through their interactions with influencers. These interactions, characterised by the exchange of content, dialogues, and endorsements, can trigger a wide spectrum of psychological responses among followers. A salient psychological response identified in this context is the emotional attachment or affinity (A) that followers develop towards influencers (Cheung et al., Citation2022). This emotional connection can profoundly influence follower behaviour and decision-making processes.

A distinct research stream centers on examining followers’ attitudes toward content created and disseminated by influencers (Ignatius Enda Panggati et al., Citation2023). These attitudes encompass dimensions such as trust (T) in the influencer (Sun & Wang, Citation2019) and loyalty (L) towards the influencer (Balaban & Szambolics, Citation2022), exerting influences on followers’ behavioural outcomes. Trust, in particular, has been highlighted as a critical factor shaping the effectiveness of influencer marketing campaigns. It often serves as the bridge between influencer-generated content and follower actions, such as purchase intentions. Loyalty, on the other hand, can be delineated as the frequency with which followers consume the influencer’s content, significantly impacting their behavioral intentions.

Previous studies indicate that establishing strong emotional bonds between followers and influencers promotes long-term relationships (Sánchez-Fernández & Jiménez-Castillo, Citation2021) and intensifies attachment, which strengthens loyalty (Breves et al., Citation2021). Additionally, attachment influences followers’ perceptions of marketing messages; attached followers view promotional posts positively and as genuine endorsements (Chen et al., Citation2021). They perceive these posts as personal recommendations, enhancing credibility and reliability. The attachment also reduces followers’ resistance to marketing messages, as they are more forgiving of influencers’ promotional intentions (Audrezet et al., Citation2020; Belanche et al., Citation2021). However, the predominant research strand within influencer marketing revolves around the investigation of influencer characteristics and their profound influence on follower behavior, with a specific focus on purchase intention (PI) (Fakhreddin & Foroudi, Citation2021).

Among the numerous attributes of influencers, follower affinity (A) has garnered significant attention. It is widely acknowledged that affinity towards influencers serves as a crucial mediating determinant of followers’ behavioral outcomes (Luo, Citation2002). However, despite the substantial focus on this aspect, there remains a conspicuous gap in understanding the formation of influencer affinity and the intricate consequences it exerts on followers’ psychological responses. SMIs forge emotional bonds with followers by sharing similarities in lifestyle and personality (Balaban & Szambolics, Citation2022), fulfilling the need for relatedness (Lee et al., Citation2021). Personal content fosters closeness and active conversations, enhancing emotional bonding (Chen et al., Citation2021). Social presence, characterized by enthusiastic communication and interaction, increases followership and trustworthiness (Breves, Liebers, et al., 2021; Bouchillon, Citation2021). SMIs’ responsiveness and warmth in communication further deepen affinity as they actively engage with followers and reflect their opinions (Foster et al., Citation2021). Thus, SMIs’ personal and interactive approach fosters strong follower affinity towards influencers.

Furthermore, research has highlighted that it is essential to acknowledge that influencer marketing extends beyond the conventional one-way communication between a customer and a salesperson. Instead, influencer marketing operates within the intricate framework of online social communities, often referred to as virtual communities (Rundin & Colliander, Citation2021). Previous studies on social media influencers primarily focused on traditional influencers, such as those in the film industry (Wang & Lee, Citation2021). Unlike traditional influencers, who typically possess ample supporting resources, social media influencers are typically self-starters with fewer resources at their disposal (Gajanova et al., Citation2019). Hence, we pose the following inquiry: Does affinity towards social media influencers act as a mediator in the relationship between influencers and customer responses? This question remains unaddressed in empirical research, to the best of our knowledge.

Virtual communities serve as platforms where influencers engage with both individual followers and the broader follower community (Kim & Kim, Citation2021). Followers’ psychological responses, like their identification with the influencer, extend beyond the individual influencer to encompass the entire virtual community (Appel et al., Citation2020). Exploring the ripple effect of followers’ psychological responses within these communities is an area requiring further investigation. Therefore, this study aims to address gaps identified in the literature. Firstly, although the importance of influencer physical attractiveness (IPA) is recognized, there is limited research on its antecedents and consequences across various influencer factors. Secondly, despite its significant role in shaping follower perceptions and behaviors, influencer attachment or affinity (A) lacks thorough exploration. Additionally, existing studies may lack comprehensive models integrating various influencer dynamics, such as homophily (H), influencer social presence (ISP), and IPA, to understand their collective influence on follower behavioral intentions. Lastly, deeper insights into the intricate relationships between influencers and their followers are needed, especially regarding the mechanisms of trust (T) and loyalty (L) in follower-influencer connections.

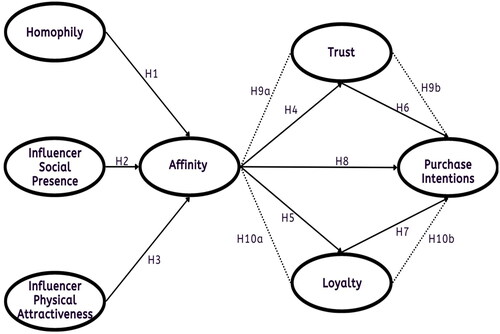

It is worth acknowledging that the roots of influencer attraction and its impact on followers’ mental reactions to influencers and the online community are unknown. Furthermore, research has missed the reality that diverse consumer views with varying susceptibility to influencers can influence followers’ behavioral goals (see ). This study seeks to fill these research gaps by examining the intricate relationships that exist between influencers and their followers, additionally contributing to effective strategies and interactions between brands and consumers in this rapidly evolving landscape.

Table 1. Table of definitions.

Theoretical framework

Attachment theory

In the realm of influencer marketing, the interactions that transpire between influencers and their followers lead to the formation of emotional bonds commonly referred to as ‘Attachment’ or ‘Affinity’ (A). Bowlby (Citation1979) defines (A) as an individual’s emotional connection with another and a mechanism for regulating behaviour to ensure security. It serves as a guiding force, directing individuals’ actions to sustain closeness with a particular target, thereby nurturing heightened levels of intimacy, commitment, satisfaction, and stability within the relationship (Collins & Read, Citation1990). Moreover, this attachment or affinity exerts an influential impact on individuals’ thoughts, emotions, and self-perceptions (A). In influencer-follower relationships, attachment theory explains how interactions shape the marketing process (Zahara et al., Citation2023). Affinity leads followers to internalise these interactions, impacting their thoughts and emotions and strengthening their commitment to the relationship. In this context, three influencer attributes play a role in establishing attachment (Rani Eka Diansari et al., Citation2023).

Social identity theory (SIT)

The affirmative judgement of specific entity characteristics is known as a recognised similarity. It can predict consumer behaviours and aids in understanding how connections are first made and developed (Turner, Citation1981). Favouritism for influencers is essential in influencer marketing. Investigating this from the standpoint of social identity theory (Turner & Oakes, Citation1986), which investigates the connection between allure and identification, can offer insight into the reasons and repercussions of this attraction. Social identity theory describes how people define themselves in relation to others and divides these interactions into three categories: communal, item, and personal. According to Turner (Citation1981), influencer liking leads to identification at the collective tier, comparable to alliances with (Turner, Citation1991), and at the item tier, similar to affiliations with businesses and websites. This affinity-identification relationship, which is based on social identity theory (Turner & Oakes, Citation1986), applies to influencer marketing, which includes both personal and virtual collective layers. Turner (Citation1981) proposed that distinctiveness, similarity, and competence, which indicate three needs (homophily, influencer social presence, and influencer physical allure, respectively), are predecessors of collective-level attraction.

Development of hypothesis

The inquiry layout in presents three predecessors of influencer fondness: similarity, online exposure of influencers, and attractiveness of influencers. This fondness for the influencer subsequently influences follower-influencer ties, intensifying followers’ behavioural intentions (e.g. reliance, devotion, and purchase intention).

Influencer qualities and influencer attractiveness

Homophily with an influencer, driven by shared values and experiences, positively correlates with influencer affinity. This association is underpinned by both social identity theory and attachment theory. According to social identity theory, individuals seek relationships with those who have similar features or interests, so satisfying their desire for relatedness. When consumers perceive commonality and social appeal in an influencer, it triggers an attachment parallel to attachment theory. Similarly, how shared experiences and familiarity foster emotional bonds.

H1: Homophily with the influencer is positively related to influencer affinity.

Social media influencer (SMI) followers form connections when they see their lifestyles and personalities mirrored in content (Lim & Rasul, Citation2022). Homophily nurtures this emotional bonding, satisfying the need for relatedness and encouraging active engagement. Ultimately, it fortifies the attachment between followers and influencers. Homophily thus catalyses influencer affinity, drawing on fundamental human needs for relatedness and attachment.

H2: Influencer social presence is positively related to influencer affinity.

Influencer marketing hypotheses suggest a positive association between influencer social presence and influencer affinity, which aligns with Social Identity Theory and Attachment Theory. However, the concept of emotional resonance adds a unique dimension. Influencers’ social presence can evoke emotions in followers, intensifying the bond formed (Mishra & Samu, Citation2021). When influencers convey authenticity, empathy, or shared passion, they resonate emotionally with their audience, intensifying the connection and affinity. This emotional resonance provides a fresh perspective on the connection between influencer social presence and influencer affinity, emphasizing the pivotal role of emotions in fostering stronger bonds.

H3: Influencer physical attractiveness is completely associated with influencer affinity.

The hypothesis suggests a positive relationship between influencer physical attractiveness and influencer affinity, based on Attachment Theory and Social Identity Theory. Social Identity Theory suggests that people naturally gravitate towards those with similar characteristics, which can be seen in physical attractiveness (Nguyen et al., Citation2020). This creates a visual identity resonance, reinforcing feelings of belonging and connection. Attachment Theory suggests that physically attractive influencers are perceived as more trustworthy and relatable, leading to a deeper sense of attachment and affinity. Visual resonance emphasizes the visual dimension in the influencer-follower relationship.

H4: Influencer affinity is completely associated with trust in the influencer.

Influencer social presence, encompassing sociability and relatedness, positively correlates with influencer affinity in online interactions. This aligns with social identity and attachment theories, fostering trust and influencer behavior (Kozinets et al., Citation2021). Social media influencers’ interactive communication style enhances followership, trustworthiness, and brand attitude. This personalized approach fosters emotional attachments, shaping influencer affinity. Thus, an influencer’s social presence cultivates stronger bonds and emotional connections.

H5: Influencer affinity is positively related to loyalty towards the influencer.

Influencer marketing is a dynamic field that involves a multifaceted approach to loyalty. It goes beyond traditional repeat purchase behavior, encompassing persistent engagement, advocacy, and commitment. Followers who form a deep sense of belonging and emotional attachment within virtual communities are more likely to exhibit enduring loyalty (Sánchez-Fernández & Jiménez-Castillo, Citation2021). This loyalty extends beyond transactional interactions and can transform into a profound emotional connection, similar to attachment bonds in Attachment Theory. This connection is often demonstrated through active participation, support, and advocacy within the influencer’s community.

H6: Trust in influencers is significantly connected to purchase intention.

Trust in influencers significantly influences consumers’ purchase intentions, supported by attachment theory and social identity theory. Social identity theory suggests individuals form positive associations with individuals or groups they perceive as similar or desirable (Kim & Kim, Citation2021). Trust in influencers leads to a perception of their recommendations as credible and reliable, stemming from a sense of affinity and shared values. According to attachment theory, individuals gain a sense of security and support from influencers, which fosters trust in their knowledge and judgement. Thus, confidence in influencers raises purchasing intentions dramatically.

H7: Consumer Loyalty for the influencers is inextricably linked to purchase intention.

According to social identity theory and attachment theory, individuals build profound relationships with influencers who embody their favoured qualities or ideas. Dedication to influencers leads to higher trust in their recommendations and purchase intent (Lou & Yuan, Citation2019). According to attachment theory, emotional attachment to influencers gives comfort, support, and guidance, fostering dedication. This commitment is founded on the influencer’s expertise and judgement, resulting in favourable purchasing intentions. As a result, more consumers follow influencers because they believe their suggestions will lead to rewarding and helpful purchases.

H8: Consumer Affinity for the influencers is positively related to purchase intention.

According to the study, customer emotional attachment to influencers has a beneficial effect on purchase intention. Strong attachment fosters trust in their suggestions, fostering loyalty and openness to product endorsements (Turner & Oakes, Citation1986). In turn, this trust motivates buying intentions. The research backs the notion that emotional connections and trust are pivotal in shaping consumer behavior, highlighting the significance of fondness in driving purchase intentions.

H9: Trust acts as a mediator in the relationship between affinity and purchase intention.

According to community identity theory and connection theory (Hein, Citation2022), belief is a critical component in the relationship between liking and purchase intention. According to communal identification theory, individuals develop a tremendous affinity for influencers who resemble them, encouraging belief and reliability. The importance of individuals creating ties to influencers who provide safety, aid, and guidance is emphasised by connection theory. This notion is supported by research, emphasising the importance of cultivating trust in influencers to influence purchasing decisions.

H10: Loyalty mediates the effect of affinity on purchase intention.

Understanding customer behaviour and buying intentions requires an understanding of allegiance. According to collective identity theory, individuals have strong attachments with organizations or trademarks that match their self-concept and collective identity (Walters, Citation2020). Fondness for a trademark fosters allegiance, which moderates its impact on purchasing intentions. Bond theory emphasises emotional links and confidence, which deepen these bonds and influence buying decisions.

Methodology of the study

Sample collection and sampling method

To ensure the truthfulness and consistency of our study, we employed a cross-sectional survey methodology, which was meticulously created and pre-tested. The survey was self-administrated to capture social-demographic diversity. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Technical Committee of SIBM, Pune, and this request was duly approved. To mitigate bias in the selection process, every respondent was approached for consent and participation at each survey point. All participants provided informed written consent prior to participating in the study. Additionally, the introductory page of the questionnaire included a section where participants were re-informed about their consent. This ensured that they fully understood their rights and the study’s objectives. The section explicitly conveyed the authors’ gratitude for the participants’ valuable input and provided detailed information on study objectives, procedures, potential risks, and participants’ rights. Participants were assured of confidentiality and informed that their responses would be used solely for academic research purposes. Additionally, they were made aware of the voluntary nature of participation, with the right to withdraw at any time without consequence. Data collection utilized a digital survey questionnaire, with respondents recruited from diverse online social media platforms such as Google Invite, WhatsApp, Instagram, and Facebook invitations (Kay et al., Citation2020). Respondents for this study were selected using purposive sampling to ensure the sample met specific inclusion criteria essential for the research. This method was chosen to facilitate timely and relevant data collection. Eligibility was limited to individuals with prior experience following influencers in the beauty and fashion industry and a purchase history within the past six months influenced by influencer marketing. This targeted approach allowed the collection of pertinent data from a knowledgeable and relevant respondent pool, thereby enhancing the validity and reliability of the study’s findings. Preliminary testing involving 50 respondents was carried out to refine the measurement scale used in the study.

To align with the study’s focus on influencer marketing, the researchers provided two specific definitions: ‘influencer’ and ‘influencer marketing’ (refer to ). The survey was designed with three stages. During Stage 1, participants were informed of their consent rights and provided with detailed instructions. These instructions included definitions of key terms, specifically ‘influencer’ and ‘influencer marketing’ (Parts I and II in ). They were subsequently asked to recollect their interactions with influencers. Definitions of Influencer and Influencer Marketing.

In the second stage of data collection, participants were asked to furnish demographic details, including their full name, age, and gender. Stage 3 focused on questionnaire items derived from the study’s conceptual model, and participants responded based on their recollections (Tsai et al., Citation2021). After excluding 35 invalid responses, the study retained 408 valid responses, comprising 49.5% female and 50.5% male respondents. Notably, 72.6% of the participants were under the age of 35. The respondents’ demographic details are given in .

Table 2. Respondents demographics.

Scale development

This research used a Likert scale of 5 points to evaluate constructs such as homophily, influencer social presence, influencer physical attractiveness, affinity, trust, loyalty, and consumer purchase intention. Five items were adopted for each construct, adapted from various sources (Hajli, Citation2019). For homophily, social presence, physical attractiveness, affinity, trust, loyalty, and purchase intention, items were modified and adapted from (Gilly et al., Citation1998; Jun & Yi, Citation2020; Kim & Kim, Citation2022; Park et al., Citation2010; Sands et al., Citation2022; Wang et al., Citation2019; Yan et al., Citation2024). The complete list of scale items can be found in ().

Table 3. Source and description of the study constructs.

Analysis of data and results

Assessment of common method bias

Harman’s single-factor test was employed to measure the potential impact of common method bias. This test, as per Harman’s single-factor test, scrutinizes whether a single factor can explain a substantial proportion of the covariance among variables, which would signify the presence of common method bias. In our examination, the initial component accounted for a mere 38% of the variance, representing that communal method bias did not exert a significant influence. Consequently, the author ascertained that the proposed framework endured unaffected by common method bias.

Measurement of reliability and validity

This study utilized the Partial Least Squares (PLS) method for predictive modeling using the SMART PLS 4.0 software (Purohit et al., Citation2022). The evaluation included validity and reliability aspects, including scales, Cronbach’s alpha, Average Variance Extracted (AVE), factor loadings, and Composite Reliability (CR). The results showed robust factor loading values, high internal consistency, and composite reliability values (Hajli, Citation2019). Convergent validity was established by examining AVE values across different constructs, with all values exceeding the threshold of 0.50. The PLS methodology was chosen due to its ability to accommodate formative and reflective indicators, allowing for complex interactions among variables and avoiding inadmissible solutions and factor indeterminacy. However, constraints such as data distribution, measurement scales, and sample size need to be considered. Overall, the research data demonstrated commendable levels of reliability and validity. The limitations imposed by the method are data distribution, measurement scales, and sample size. Overall, the dependability and validity of the research data were excellent. The method’s constraints on data distribution, measurement scales, and sample size.

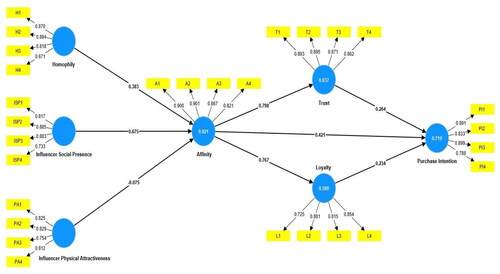

The measuring model was thoroughly evaluated to determine the accuracy of the scales, Cronbach’s alpha, Average Variance Extracted (AVE), factor loadings, and Composite Reliability (CR). The analytical outcomes revealed that all items exhibited factor loading values ranging from 0.671 to 0.901, consistently exceeding the established threshold of 0.6, thereby affirming their statistical significance and acceptability (Appel et al., Citation2020). Moreover, the constructs exhibited notably high levels of reliability, as evidenced by Cronbach’s alpha spanning from 0.820 to 0.903 and composite reliability for the items ranging from 0.873 to 0.924. These values surpassed the recommended threshold of 0.70, signifying a robust level of reliability within the model, as depicted in . Convergent validity was effectively established through the AVE values, which ranged from 0.669 to 0.775 across the constructs (refer to ). Notably, all the values of AVE surpassed the established threshold of 0.50, thereby affirming the presence of convergent validity. Grounded on these insights, it is obvious that the research data consistently demonstrated a high degree of reliability and validity.

Table 4. Composite reliability, factor loadings, Cronbach’s Alpha and AVE.

Discriminant validity analysis

To evaluate the discriminant validity of the variables, the standard proposed by Fornell and Bookstein (Citation1982) was employed. This criterion entails a comparison between the square roots of the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for each construct and the correlations between the constructs themselves. In , the square root values of each construct were found to be notably higher than the correlations of those constructs with others, thus substantiating the discriminant validity of the constructs. The Fornell-Larcker measure further affirmed the discriminant validity of the variables. Additionally, it is noteworthy that the factor loadings of the remaining items associated with each variable surpassed the established threshold value of 0.600, underscoring the substantial contribution of each item to its respective construct. Comprehensive details regarding the constructs’ reliability, validity, and discriminant validity are found in .

Table 5. Assessment of discriminant validity.

Model fit

In accordance with Fornell and Bookstein (Citation1982), the assessment of model fit encompasses the consideration of several indices. The Standardized Root Mean Residual (SRMR) values serve as indicators of the dissimilarity between the observed and model-implied correlation matrices (as displayed in ). The computed SRMR values amounted to 0.079 for the saturated model and 0.102 for the assessed model, thereby indicating a favourable fit. Furthermore, the d_ULS values, which gauge the discordance between observed and anticipated covariances, were 2.560 for the saturated model and 4.264 for the evaluated model, while the d_G values signify the distinction in degrees of freedom, respectively (Liu et al., Citation2022). Overall, the various models for indices suggest that the estimated model provides a satisfactory data fit.

Table 6. Assessment of the model fit.

Structural model

The primary objective of this study’s structural model () was to investigate the interconnections among various constructs and their influence on the outcome variable. Throughout the analysis, the examination included an assessment of path coefficients, which signify both the magnitude and direction of these relationships, along with the evaluation of statistically significant indicators.

presents the outcomes derived from the examination of the structural model, elucidating the approximate impact of each predictor variable on the ultimate value. As an illustration, the path coefficient of Trust and Purchase Intention was computed at 0.668, signifying a statistically significant and positive relationship (An et al., Citation2019). This underscores that heightened levels of trust correspond to increased levels of Purchase Intention.

Table 7. Path coefficient.

The study found a substantial and positive association between loyalty and customer purchase intention, with higher levels corresponding to higher intention. Affinity signifies a positive association with trust and loyalty, with 0.798 and 0.766, respectively (Hair et al., Citation2011). Homophily, Influencer Social presence, and Influencer Physical Attractiveness were found to have significant links with affinity, with 0.385, 0.076, and 0.674, respectively. Trust and loyalty were also found to have substantial and positive connections, with 0.478 and 0.403, indicating higher levels of trust are associated with higher loyalty and purchase intent (Hair et al., Citation2020). Overall, the study highlights the significance of social presence and trust in influencing consumer behaviour.

Overall, the outcomes of the proposed model analysis support the hypothesised relationships among the constructs. They indicate that Affinity, Loyalty, and Trust are all important factors influencing consumer behavior, specifically in relation to Purchase Intention. shows the standard path coefficient (p) and t-value, path significance, and R-square value for endogenous constructs ().

R-square interpretation

The model’s predictive precision was evaluated through R-square values, which reflect the squared correlation between the actual and predicted values for individual constructs. The outcomes revealed that customer purchase intention exhibited an R-square value of 0.668, loyalty attained an R-square value of 0.587, trust in effective marketing achieved an R-square value of 0.636, and affinity demonstrated an R-square value of 0.921. These findings collectively indicate that the model provides a notably high degree of accuracy in predicting outcomes for each construct.

The analytical accuracy of the proposed model was evaluated further by the Batu-Geisser Q-square value, which is a cross-validated odds ratio. The mean square values for customer purchase intention, loyalty, trust, ineffective marketing, and affinity were 0.666, 0.586, 0.635, and 0.920, respectively. All these values exceeded the null hypothesis, confirming the model’s predictive value for the constructs.

The extent of the effects was also assessed following the guidelines suggested (Hair et al., Citation2019). In line with established criteria, where an effect size of f2 ≥ 0.02 denotes a small effect, f2 ≥ 0.15 indicates a medium effect, and f2 ≥ 0.35 signifies a substantial effect, the outcomes are outlined in . Notably, a mediating effect size was discerned for the interaction of affinity, while a considerably substantial effect size was evident for trust and loyalty within the context of effective marketing. These findings underscore the substantial impact of trust and loyalty in shaping consumer purchase intention, thus substantiating the significance of these constructs within the model.

Table 8. Predictive relevance analysis.

Overall, the outcomes indicate the proposed model has a robust analytical ability, with moderate to large effect sizes for the studied constructs. This analysis suggests that the model is able to accurately capture the complex relationships between the variables studied. The findings provide valuable insights into consumer behavior and expand the influencer marketing literature.

Hypothesis testing

presents the statistical significance of a path analysis among all the study constructs. The study investigated and tested 10 hypotheses concerning the impact of homophily (H), influencer social presence (ISP), and influencer physical attractiveness (IPA) on affinity (A) and the mediating effects of trust (T) and loyalty (L) customer purchase intention (PI). Thе path analysis results rеvеalеd that thе path coefficients bеtwееn thе variables were statistically significant. This implies that the relationship between the variables has a direct effect on each other (Becker et al., Citation2022). The direct effect of H on A (H1), ISP on A (H2), IPA on A (H3), A on T (H4), Aon L (H5), T on PI (H6), L on PI (H7) and A on PI (H8) along with the effect of affinity on consumer purchase intent, mediating by loyalty and trust (H9 and H10), were supported respectively. summarizes thе findings and provides support for thе proposed hypotheses.

Table 9. Hypothesis Testing.

and present findings concerning the path estimates and significance of hypotheses (H1 to H11) related to affinity towards social media influencers. H1 and H2, which posited a positive relationship between homophily and influencer social presence, were supported (H1: β = 0.385, p = .033; H2: β = 0.674, p = .037). However, H3, suggesting a positive link between influencers’ perceived physical attractiveness and affinity, was not supported, revealing a statistically significant negative relationship (H3: β = −0.076, p = .036).

Furthermore, our results demonstrate that affinity significantly impacts trust and loyalty towards influencers, thus supporting H4 (β = .798, p = .000) and H5 (β = 0.766, p = .000), respectively. This positive influence continues downstream, as trust, loyalty, and affinity towards social media influencers collectively enhance purchase intentions, endorsing H6 (β = −0.076, p = .036), H7 (β = 0.478, p = .000), and H8 (β = 0.691, p = .000).

Additionally, our findings reveal a substantial and positive mediation of trust and loyalty on the relationship between affinity and purchase intentions, thus providing support for H11 (Hair et al., Citation2019). These results collectively shed light on the intricate dynamics of consumer behaviour towards social media influencers, highlighting the nuanced role of affinity in shaping trust, loyalty, and purchase intentions. H11a (β = 0.691, p = .000) and H11b (β = 0.691, p = .000).

Mediation variables analysis

Mediation analysis was conducted to examine two aspects: (a) the mediating function of trust and (b) the mediating function of loyalty in the association between affinity and purchase intention. The outcomes of the mediation analysis, considering trust as the mediator, unveiled a statistically significant indirect effect of affinity on buyers’ purchase intention (H9: β = 0.211, t = 4.628, p < .01) mediated by trust (Naseem & Yaprak, Citation2022). Notably, the total effect of affinity on customer purchase intention was statistically significant (β = 0.811, t = 37.459, p = .01). Even when trust was included as a mediator, the results remained statistically significant (β = 0.420, t = 7.487, p = .01). These findings confirm H9 by indicating the presence of a complementary partial mediating function of trust in the link between affinity and purchase intentions.

Similarly, the mediation study, with loyalty as the mediator, revealed a significant indirect influence of affinity on purchasers’ purchase intention (H10: = 0.180, t = 4.397, p = .01) via loyalty mediation. The total impact of affinity on purchasers’ purchase intention remained statistically significant (β = 0.811, t = 37.459, p = .01), while the inclusion of loyalty as a mediator had no influence on the results (β = 0.420, t = 7.487, p = .01). These findings reinforce H10 by indicating a complementary partial mediation function of loyalty in the link between affinity and purchase intentions (refer to ).

Table 10. Exploring mediation effects.

The study’s findings provide comprehensive knowledge of the underlying mechanisms that influence buying intent. They emphasize the relevance of including mediating factors in consumer decision-making models because they expose the sophisticated dynamics at work. Ultimately, our research contributes to a more comprehensive comprehension of consumer behaviour, which can inform marketing strategies and practices.

Discussion

Summary of findings

This study explores the dynamics of influencers’ attachment to their audience through personal attributes, emphasizing micro-influencers characterized by smaller networks and the adoption of long-term partnership strategies. The current study is undertaken to fill the knowledge gap in prior research in this field. The existing studies have primarily focused on the perspectives of influencer-focused or brand-focused benefits (Aw et al., Citation2022; Hugh et al., Citation2022). The extant empirical research has not considered social media users’ basic motivations for consuming digital content, such as their affection towards the influencer and their psychological association with the content of the influencer (Gomes et al., Citation2022; Kim & Kim, Citation2022; Zhang & Choi, Citation2022). The research reveals how these influencers employ interpersonal influence through engaging communication on social platforms, influencing consumer responses to marketing messages, and highlighting the growing popularity of these influencers in the marketing industry (Yazdanian et al., Citation2019).

Additionally, the study revealed that influencers foster connections with their audience by authentically sharing personal experiences, providing valuable content, and actively engaging with their followers. It emphasized the significance of homophily in influencer-follower relationships, elucidating how influencers strategically leverage shared characteristics and interests with their audience to deepen connections and enhance purchase intentions. This finding aligns with the previous literature indicating a positive correlation between consumer product purchases and influencers with whom they share similarities (homophily) (Balaban et al., Citation2022; Lee et al., Citation2021). However, the finding contradicts with studies that have discovered a negative relationship between homophily and purchase intention (Shen et al., Citation2022). The reason for contradiction can be excessive homophily, which may lead to skepticism or disengagement among followers. This skepticism could arise from a desire for diversity and newness in the content they consume (Wu et al., Citation2022), emphasizing the complexity of consumer behavior within influencer marketing contexts.

Influencers’ social media presence, as well as their physical appeal, are important in the creation of connection. This association boosts loyalty and trustworthiness, mimicking consumer-brand relations. As followers get closer to influencers, they are more inclined to maintain their relationship and regard their content as more trustworthy. This aligns with findings from (Casaló et al., Citation2020) as well as research by Zhao et al. (Citation2020), which observed that valuable and high-quality information to users assists influencers in obtaining user trust and support as developing stronger emotional attachment with users. Similar outcomes are documented in studies focusing on consumers’ emotional attachment to the influencer content (Zhang & Choi, Citation2022).

This relationship diminishes skepticism and rebuttal of promotional information, lowering resistance to marketing messaging. This finding is consistent with earlier research on attachment in consumer-brand interactions, which shows that attachment leads to personal detriments and forgiving of wrong information (Ki et al., Citation2020). One intriguing result of our study is the negative effect of the physical attractiveness of influencers on affinity, which is inconsistent with past studies (Aw & Chuah, Citation2021; Lou & Yuan, Citation2019). Despite its influence on followers’ responses, the study finds that attachment does not affect their impression of influencer recommendations as advertising. One possible reason is that the previous studies did not take into account the components affecting influencer–followers interaction and the heterogeneity of consumer preferences, which overwhelms the power of influencer physical attractiveness. In the same realm, Kim and Kim (Citation2021) discovered that the physical attractiveness of influencers is an effective cue for positive initial judgment but not in facilitating relatively long-term interactions between influencers and consumers.

This is due to increased public knowledge of sponsored posts, influencer remuneration, and the FTC’s need for clear sponsorship disclosure. Regardless, connection contributes to higher credibility and decreased resistance to endorsements. The study also emphasizes the significance of affinity in drawing customers and building trust and loyalty to influencers, thereby supporting the study by Aw and Chuah (Citation2021). It underlines the importance of influencer social media presence in increasing customer interaction and brand recognition, as well as closing the gap between buyers and sellers (Ao et al., Citation2023). The study also emphasizes the importance of follower-influencer connections and community interactions in increasing followers’ affinity, which leads to increased purchase intentions (Moraes et al., Citation2019; Reinikainen et al., Citation2020). The study concludes that affinity, trust, and loyalty act as a mediator in the connection between various factors and customer purchase intention, implying that strategic incorporation of these factors into social commerce platform marketing strategies has the potential to improve customer retention and drive sales growth.

Contributions to theory and managerial relevance

Contribution to literature

This study significantly advances the influencer marketing literature by delving into the interpersonal resources inherent to influencers, including homophily, social presence, and physical attractiveness. These resources are found to be instrumental in fostering stronger connections with followers, as elucidated by previous research (Liu et al., Citation2022; Sokolova & Perez, Citation2021). By examining these aspects, the study extends the theoretical framework of Attachment Theory, offering insights into how these interpersonal resources play a crucial role in strengthening connections with followers. This allows influencers to establish a personal connection akin to attachment, thereby deepening their influence on follower purchase decisions, as highlighted by prior research by Sánchez-Fernández and Jiménez-Castillo (Citation2021).

Moreover, the research validates the mediating roles of affinity, trust, and loyalty within Social Influence Theory (SIT) and Attachment Theory (AT), consistent with the propositions of Turner and Oakes (Citation1986) and Bowlby (Citation1979). This underscores the interplay of these psychological constructs and their impact on consumer behavior within influencer marketing contexts. Additionally, the study expands upon SIT by investigating the effect of influencer social presence on customer purchase intentions. Traditionally, SIT emphasizes homophily as a key driver of social influencer processes, focusing on how individuals are more likely to be influenced by others who are similar to themselves (Kim & Kim, Citation2021; Lim, Citation2022). This study adds to the social influence theory that beyond mere similarity, the active engagement and perceived accessibility of influencers play a vital role in molding consumer attitudes and behaviors (Gupta et al., Citation2022).

Furthermore, through the exploration of the relationship between influencer social presence, physical attractiveness, and the mediating factors of affinity, trust, and loyalty, the research provides empirical evidence supporting its theoretical framework. For instance, a study by Kim and Kim (Citation2021) found that influencers with high social presence and physical attractiveness tend to engender greater affinity and trust among followers, leading to increased purchase intentions (Breves, Amrehn, et al., Citation2021). This empirical validation strengthens the theoretical underpinnings of the study and contributes to a profound understanding of the mechanisms driving consumer behaviour in influencer marketing contexts (Aw & Chuah, Citation2021).

Consequently, this research contributes a versatile model applicable to diverse consumer products endorsed by influencers, thereby refining and advancing the Observational Learning Theory (Daradkeh, Citation2022) and the Theory of Planned Behavior (Lavuri, Citation2021). By elucidating the intricate mechanisms underlying influencer-follower relationships and their impact on consumer decision-making, this study significantly enriches the theoretical foundations of influencer marketing. It offers practical implications for marketers seeking to leverage influencers effectively in their campaigns.

Managerial relevance

The findings of this research underscore the critical importance of transparency in social media influencer marketing, particularly among millennials and Gen Z consumers, aligning with previous studies (Liu et al., Citation2022; Sokolova & Perez, Citation2021). Marketers should prioritize transparent messaging, openly disclosing sponsorships, and actively involving followers in marketing campaigns to enhance authenticity and credibility (Balaban et al., Citation2021; Lina et al., Citation2022). Suppose a skincare brand collaborates with a skincare influencer who maintains transparency in sponsored content, as demonstrated by Giuffredi-Kähr et al. (Citation2022). In that case, it fosters trust and credibility among followers, ultimately driving brand engagement and purchase intentions.

Moreover, the study highlights the imperative of delivering captivating, informative, and trustworthy marketing messages to effectively influence purchase intentions, a sentiment echoed in previous research (Ao et al., Citation2023; Dash et al., Citation2021). For instance, a fitness apparel brand partnering with a fitness influencer known for delivering informative content that educates her followers about the brand’s products and their benefits (Durau et al., Citation2022) enhances brand awareness and positively impacts purchase intentions among its target audience. Furthermore, the research emphasizes the pivotal role of user affinity, trust, and loyalty in driving sales through influencer-driven advertisements, consistent with the findings of Kim and Kim (Citation2021) and Wong and Haque (Citation2021).

Additionally, the study highlights a negative relationship between the perceived physical attractiveness of influencers and the level of affinity among consumers. This unexpected finding suggests that while physical attractiveness may initially attract attention, it may not necessarily foster long-term affinity or trust among followers (Aw & Chuah, Citation2021; Lou & Yuan, Citation2019). For marketers and practitioners, this finding underscores the importance of prioritizing authenticity and relatability over superficial qualities when selecting influencers for brand collaborations (Balaban & Szambolics, Citation2022). Influencers themselves may benefit from diversifying their content to focus on quality content and genuineness rather than solely relying on their appearance (Kim & Kim, Citation2021). Finally, consumers should critically evaluate influencer content beyond surface-level attractiveness, considering factors such as transparency, insights, credibility, and alignment with personal values when engaging with influencers and making purchasing decisions (Kapitan et al., Citation2021).

The study further highlights the substantial impact of homophily on user affinity towards influencers, indicating that when influencers align with their audience in terms of lifestyle, values, or interests, it fosters a stronger sense of connection and trust among followers (Sokolova & Perez, Citation2021). This underscores the importance for marketers and practitioners to thoroughly understand the demographics and preferences of their target audience when selecting influencers for collaborations (Ouvrein et al., Citation2021). By strategically aligning with influencers who resonate with their audience, marketers can enhance the effectiveness of influencer marketing campaigns and drive higher levels of affinity and engagement (Harrigan et al., Citation2021).

Lastly, the study highlights the necessity of incorporating product involvement into influencer marketing strategies, particularly within the fashion industry, supporting the findings of (Belanche et al., Citation2021; Cabeza-Ramírez et al., Citation2023). An illustrative example would be a fashion brand collaborating with a fashion influencer who actively involves her followers in the brand’s product development process (Hugh et al., Citation2022), fostering a sense of ownership and excitement among her audience, thereby driving purchase intentions.

Conclusion

This research delves into the influence applied by social media influencers on customer purchase intentions, elucidating that influencer social presence holds significant sway over consumer behavior and purchasing choices. Notably, trust, loyalty, affinity, and homophily emerge as pivotal factors in elucidating this intricate association. Additionally, the credibility and relatability of influencers serve to augment their influence on purchase intentions. Within this context, the study posits that marketers can effectively employ influencer physical attractiveness and affinity as strategic marketing tools, as corroborated by Dwivedi et al. (Citation2021). Furthermore, the judicious selection of authentic influencers, coupled with vigilant monitoring of social media discourse, holds the potential to heighten the efficacy of social media advertising campaigns.

Crucially, affinity plays a pivotal role in mediating the interplay between influencers’ social presence, homophily, and customer purchase intentions. Ensuring the provision of engaging content and cultivating follower loyalty emerges as imperatives for galvanizing followers into meaningful action. This study offers both practical implications and theoretical significance value for marketers leveraging influencer social presence. Such insights empower marketers to craft robust campaigns and optimize returns on investments in this dynamic landscape.

Limitations and future lines of research

The study on social media, marketing, and consumer behavior in India has significant contributions but also presents limitations. Cultural variations and socio-economic traits may influence consumer decisions, so future research should consider these factors. Influencer characteristics, such as expertise, knowledge, consistency, and authenticity, are crucial for trust and follower identification. The cross-sectional quantitative approach, focusing on beauty and fashion, requires controlled experimental settings to minimize product variations and enhance reliability. The study’s unique focus on influencer-following audiences raises questions about result generalizability. Additionally, the study does not consider individual follower characteristics and the impact of emotional attachment on different cultural contexts and age groups. The study highlights the need for future research to consider cultural contexts, influencer characteristics, and controlled experimental approaches, as well as broaden the scope to address its limitations and open avenues for further research.

Authors contributions

The authors contributed to this study in the following ways:

Aditi Rajput: Conception design and data collection, Analysis and Interpretation of Data, Drafting of the Paper

Aradhana Gandhi: Revising It Critically for Intellectual Content, Final Approval of the Version to Be Published

Figure_Captions.docx

Download MS Word (12.7 KB)Figure_2.docx

Download MS Word (99.5 KB)Table_10.docx

Download MS Word (15.3 KB)Table_1.docx

Download MS Word (14.2 KB)Table_3.docx

Download MS Word (28.3 KB)Table_4.docx

Download MS Word (17 KB)Table_6.docx

Download MS Word (13.9 KB)Table_7.docx

Download MS Word (14.7 KB)Table_2.docx

Download MS Word (15.2 KB)Annexure_I_Table_11.docx

Download MS Word (16.1 KB)Table_8.docx

Download MS Word (13.6 KB)Table_9.docx

Download MS Word (16 KB)Table_5.docx

Download MS Word (15 KB)Acknowledgment

The authors are grateful to the anonymous referees of the journal for their helpful comments on improving the article.

Disclosure statement

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research and publication of the article.

Data availability statement

The data supporting the findings in this manuscript are available upon request. To access the data, please contact the corresponding author at [email protected]

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Aditi Rajput

Aditi Rajput is a Junior Research Fellow at the Symbiosis Center for Research and Innovation (SCRI) under Symbiosis International Deemed University (SIU), Pune. She is currently engaged in research at the Symbiosis Center of Behavioral Studies, housed within the Symbiosis Institute of Business Management (SIBM). She holds a master’s degree in E-commerce (Marketing) Management from Devi Ahilya University, Indore. Her primary research interests lie in Influencer Marketing, Digital Marketing, Consumer Behaviors, Social Media Marketing, and Consumer Eye-Tracking. She focuses on exploring Customer Engagement and Behavioral Intentions within the marketing domain. She has several scholarly contributions, with research articles published in Scopus-indexed journals.

Aradhana Gandhi

Aradhana Gandhi is a Professor at Symbiosis Institute of Business Management (SIBM). She is also the faculty in-charge of Symbiosis Centre for Behavioral Studies (SCBS). She is a management graduate and a doctorate in management (Retail) under Dr. Ravi Shankar, IIT – Delhi, with 4 years of industry experience and 23 years of teaching and training experience. Her core area of research is in Retail and Consumer Behavioral Studies. She has several publications in the area of area of Consumer Behavior and Retail in reputed International journals like International Journal of Retail and Distribution Management (ABDC, A), Benchmarking: An International Journal (ABDC, B) and Asia Pacific journal of Management (ABDC, A), International Journal of Electronic Marketing and Retailing (ABDC, C), to name a few. She is currently guiding 6 PhD scholars and 1 scholar has received his degree. Apart from conducting courses in the area of Retail, she teaches courses in the area of Research Methodology, Marketing Research, CRM, Retail Marketing, Academic Writing, Experimental Studies, Qualitative Studies, to name a few.

References

- Alboqami, H. (2023). Trust me, I’m an influencer! – Causal recipes for customer trust in artificial intelligence influencers in the retail industry. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 72, 103242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.103242

- An, S., Kerr, G., & Jin, H. S. (2019). Recognizing native Ads as advertising: attitudinal and behavioral consequences. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 53(4), 1421–1442. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12235

- Ao, L., Bansal, R., Pruthi, N., & Khaskheli, M. B. (2023). Impact of social media influencers on customer engagement and purchase intention: A meta-analysis. Sustainability, 15(3), 2744. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15032744

- Appel, G., Grewal, L., Hadi, R., & Stephen, A. T. (2020). The future of social media in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48(1), 79–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-019-00695-1

- Audrezet, A., de Kerviler, G., & Guidry Moulard, J. (2020). Authenticity under threat: When social media influencers need to go beyond self-presentation. Journal of Business Research, 117(1), 557–569. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.07.008

- Aw, E. C.-X., & Chuah, S. H.-W. (2021). “Stop the unattainable ideal for an ordinary me!” fostering parasocial relationships with social media influencers: The role of self-discrepancy. Journal of Business Research, 132(7), 146–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.025

- Aw, E. C.-X., Tan, G. W.-H., Chuah, S. H.-W., Ooi, K.-B., & Hajli, N. (2022). Be my friend! Cultivating parasocial relationships with social media influencers: Findings from PLS-SEM and fsQCA. Information Technology & People, 36(1), 66–94. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-07-2021-0548

- Balaban, D. C., & Szambolics, J. (2022). A proposed model of self-perceived authenticity of social media influencers. Media and Communication, 10(1), 4765. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v10i1.4765[Mismatch][

- Balaban, D. C., Mucundorfeanu, M., & Naderer, B. (2021). The role of trustworthiness in social media influencer advertising: Investigating users’ appreciation of advertising transparency and its effects. Communications, 47(3), 395–421. https://doi.org/10.1515/commun-2020-0053

- Balaban, D. C., Szambolics, J., & Chirică, M. (2022). Parasocial relations and social media influencers’ persuasive power. Exploring the moderating role of product involvement. Acta Psychologica, 230, 103731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2022.103731

- Barta, S., Belanche, D., Fernández, A., & Flavián, M. (2023). Influencer marketing on TikTok: The effectiveness of humor and followers’ hedonic experience. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 70(70), 103149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.103149

- Becker, J.-M., Cheah, J.-H., Gholamzade, R., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2022). PLS-SEM’s most wanted guidance. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 35(1), 321–346. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-04-2022-0474

- Belanche, D., Casaló, L. V., Flavián, M., & Ibáñez-Sánchez, S. (2021). Building influencers’ credibility on Instagram: Effects on followers’ attitudes and behavioral responses toward the influencer. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 61(1), 102585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102585

- Belanche, D., Casaló, L. V., Flavián, M., & Sánchez, S. I. (2021). Understanding influencer marketing: The role of congruence between influencers, products and consumers. Journal of Business Research, 132, 186–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.03.067

- Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. (2003). Consumer–company identification: A framework for understanding consumers’ relationships with companies. Journal of Marketing, 67(2), 76–88. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.67.2.76.18609

- Bouchillon, B. C. (2021). Social networking for social capital: the declining value of presence for trusting with age. Behaviour & Information Technology, 41(7), 1425–1438. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2021.1876765

- Bowlby, J. (1979). The Bowlby-Ainsworth attachment theory. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 2(4), 637–638. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X00064955

- Breves, P., Amrehn, J., Heidenreich, A., Liebers, N., & Schramm, H. (2021). Blind trust? The importance and interplay of parasocial relationships and advertising disclosures in explaining influencers’ persuasive effects on their followers. International Journal of Advertising, 40(7), 1209–1229. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2021.1881237

- Breves, P., Liebers, N., Motschenbacher, B., & Reus, L. (2021). Reducing resistance: The impact of nonfollowers’ and followers’ parasocial relationships with social media influencers on persuasive resistance and advertising effectiveness. Human Communication Research, 47(4), 418–443. https://doi.org/10.1093/hcr/hqab006

- Cabeza-Ramírez, L. J., Sánchez-Cañizares, S. M., Santos-Roldán, L. M., & Fuentes-García, F. J. (2023). Exploring the effectiveness of fashion recommendations made by social media influencers in the centennial generation. Textile Research Journal, 93(13-14), 3240–3261. https://doi.org/10.1177/00405175231155860

- Cam Thuy, N., Van Dat, L., Dong, D. P., Linh, V. T., & Thang, D. N. (2023). Is digital transformation a barrier to export reduction during COVID-19? The case of a developing country. Cogent Business & Management, 10(2), 2211218. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2211218

- Campbell, C., & Farrell, J. R. (2020). More than meets the eye: The functional components underlying influencer marketing. Business Horizons, 63(4), 469–479. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2020.03.003

- Carmona, M. (2021). The existential crisis of traditional shopping streets: The sun model and the place attraction paradigm. Journal of Urban Design, 27(1), 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2021.1951605

- Casaló, L. V., Flavián, C., & Ibáñez-Sánchez, S. (2020). Be creative, my friend! Engaging users on Instagram by promoting positive emotions. Journal of Business Research, 130, 416–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.02.014

- Celestino, P. (2023, March 10). Influencer marketing in 2023: Benefits and best practices. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesagencycouncil/2023/03/10/influencer-marketing-in-2023-benefits-and-best-practices/?sh=42eb55b59b63

- Chen, T. Y., Yeh, T. L., & Lee, F. Y. (2021). The impact of Internet celebrity characteristics on followers’ impulse purchase behavior: The mediation of attachment and parasocial interaction. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 15(3), 483–501. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIM-09-2020-0183

- Cheung, M. L., Leung, W. K. S., Aw, E. C.-X., & Koay, K. Y. (2022). ‘I follow what you post!’: The role of social media influencers’ content characteristics in consumers’ online brand-related activities (COBRAs). Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 66, 102940. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.102940

- Collins, N. L., & Read, S. J. (1990). Adult attachment, working models, and relationship quality in dating couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(4), 644–663. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.58.4.644

- Currás-Pérez, R., Bigné-Alcañiz, E., & Alvarado-Herrera, A. (2009). The role of self-definitional principles in consumer identification with a socially responsible company. Journal of Business Ethics, 89(4), 547–564. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-0016-6

- Daradkeh, M. (2022). Lurkers versus contributors: An empirical investigation of knowledge contribution behavior in open innovation communities. Journal of Open Innovation, 8(4), 198. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc8040198

- Dash, G., Kiefer, K., & Paul, J. (2021). Marketing-to-millennials: Marketing 4.0, customer satisfaction and purchase intention. Journal of Business Research, 122(122), 608–620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.10.016

- Diansari, R. E., Musah, A. A., & Othman, J. (2023). Factors affecting village fund management accountability in Indonesia: The moderating role of prosocial behaviour. Cogent Business & Management, 10(2), 2219424. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2023.2219424

- Digital Marketing Institute. (2024, April 14). 20 influencer marketing statistics that will surprise you. Digital Marketing Institute. https://digitalmarketinginstitute.com/blog/20-influencer-marketing-statistics-that-will-surprise-you

- Durau, J., Diehl, S., & Terlutter, R. (2022). Motivate me to exercise with you: The effects of social media fitness influencers on users’ intentions to engage in physical activity and the role of user gender. Digital Health, 8(8), 20552076221102769. https://doi.org/10.1177/20552076221102769

- Dwivedi, Y. K., Ismagilova, E., Hughes, D. L., Carlson, J., Filieri, R., Jacobson, J., Jain, V., Karjaluoto, H., Kefi, H., Krishen, A. S., Kumar, V., Rahman, M. M., Raman, R., Rauschnabel, P. A., Rowley, J., Salo, J., Tran, G. A., & Wang, Y. (2021). Setting the future of digital and social media marketing research: Perspectives and research propositions. International Journal of Information Management, 59(1), 102168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102168

- Fakhreddin, F., & Foroudi, P. (2021). Instagram influencers: The role of opinion leadership in consumers’ purchase behavior. Journal of Promotion Management, 28(6), 795–825. https://doi.org/10.1080/10496491.2021.2015515

- Fornell, C., & Bookstein, F. L. (1982). Two structural equation models: LISREL and PLS applied to consumer exit-voice theory. Journal of Marketing Research, 19(4), 440–452. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151718

- Foster, J. K., McLelland, M. A., & Wallace, L. K. (2021). Brand avatars: Impact of social interaction on consumer–brand relationships. Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 16(2), 237–258. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRIM-01-2020-0007

- Gajanova, L., Nadanyiova, M., & Moravcikova, D. (2019). The use of demographic and psychographic segmentation to creating marketing strategy of brand loyalty. Scientific Annals of Economics and Business, 66(1), 65–84. https://doi.org/10.2478/saeb-2019-0005

- Geyser, W. (2021, February 9). The state of influencer marketing 2021: Benchmark Report. Influencer Marketing Hub. https://influencermarketinghub.com/influencer-marketing-benchmark-report-2021/

- Gilly, M. C., Graham, J. L., Wolfinbarger, M. F., & Yale, L. J. (1998). A dyadic study of interpersonal information search. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 26(2), 83–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070398262001

- Giuffredi-Kähr, A., Petrova, A., & Malär, L. (2022). Sponsorship disclosure of influencers – A curse or a blessing? Journal of Interactive Marketing, 57(1), 18–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/10949968221075686

- Gomes, M. A., Marques, S., & Dias, Á. (2022). The impact of digital influencers’ characteristics on purchase intention of fashion products. Journal of Global Fashion Marketing, 13(3), 187–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/20932685.2022.2039263

- Gupta, P., Burton, J. L., & Costa Barros, L. (2022). Gender of the online influencer and follower: the differential persuasive impact of homophily, attractiveness and product-match. Internet Research, 33(2), 720–740. https://doi.org/10.1108/INTR-04-2021-0229

- Hair, J. F., Astrachan, C. B., Moisescu, O. I., Radomir, L., Sarstedt, M., Vaithilingam, S., & Ringle, C. M. (2020). Executing and interpreting applications of PLS-SEM: Updates for family business researchers. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 12(3), 100392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2020.100392

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23033534 https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hajli, N. (2019). The impact of positive valence and negative valence on social commerce purchase intention. Information Technology & People, 33(2), 774–791. https://doi.org/10.1108/ITP-02-2018-0099

- Harrigan, P., Daly, T. M., Coussement, K., Lee, J. A., Soutar, G. N., & Evers, U. (2021). Identifying influencers on social media. International Journal of Information Management, 56, 102246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102246

- Hein, N. (2022). Factors influencing the purchase intention for recycled products: Integrating perceived risk into value-belief-norm theory. Sustainability, 14(7), 3877. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14073877

- Hudders, L., De Jans, S., & De Veirman, M. (2021). The commercialization of social media stars: A literature review and conceptual framework on the strategic use of social media influencers. International Journal of Advertising, 40(3), 327–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2020.1836925

- Hugh, D. C., Dolan, R., Harrigan, P., & Gray, H. (2022). Influencer marketing effectiveness: The mechanisms that matter. European Journal of Marketing, 56(12), 3485–3515. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-09-2020-0703

- Jason, M., Hung, D. Q., & Ida, G. (2023). The influence of digitalisation on the role of quality professionals and their practices. Cogent Business & Management, 10(1), 2164162. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2022.2164162

- Jun, S., & Yi, J. (2020). What makes followers loyal? The role of influencer interactivity in building influencer brand equity. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 29(6), 803–814. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBM-02-2019-2280