Abstract

Urban public open space is a myriad between the physical and the social. Their relationship has been conceived in various terms; the focus shifting between one and the other; nevertheless, in most cases, the language of criticism has so far been lacking, and descriptions have tended towards a more generic, non-nuanced language of criticism. Taking advantage of developments in the field of criticism of language, based, as they were, on methods of Structuralist and Post-structural linguistic analysis, in this case, namely, the work of Rosalind Krauss, and, Manfredo Tafuri, an attempt is made to link up the language of criticism developed individually, by Krauss, for Sculpture, and by Tafuri, for Architecture, for the purpose of advancing a similarly informed language of criticism, to urban design practice; taking, for the purposes of this effort, four relatively recent urban design projects for the creation of urban public open space in Amman, completed, 2005–2011.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Today, issues concerning urban public space acquire heightened importance due to rising concerns and competing claims over authorship and use of such an important part of our cities. The techno-political processes that shape urban public space are becoming more complicated, and the stakeholders are no longer restricted to the architect and his client. A broader-based discussion over the shaping and the resultant shape of urban public space is needed; yet, a nuanced language of criticism seems to be as yet missing or inadequate. Therefore, based on the pioneering linguistic analytical work of Rosalind Krauss in the field of sculpture, and, Manfredo Tafuri, for architecture, this article aims to contribute towards the development of a more nuanced language of criticism concerning the design or urban public space, one that can be used to structure our discussions on the shaping and shape of our cities.

1. Introduction

Public Urban Space is a myriad between space and people; the physical, and the social; however, in conceptualizing public open space, one side has always taken priority over the other. When the “physical” was given priority, public urban space tended to be conceived as an outdoor “room”, while, when the social was given priority, it tended towards being considered as a social “meeting place”. The former tendency brought the design of public open space closer towards architecture, albeit on a bigger scale; while, in the latter case, it became focused on the social interaction of people.

This relationship between the physical and the social has been visualized variously as “Theatre”, where the public urban space becomes the backdrop for social interaction (Kostof & Castillo, Citation1995), or as “Ludic Space” for play and an occasion for the unexpected (Stevens, Citation2007), a kind of “Leisure Space” for tourism, for example, or, as an “amenity”, whereby urban space would serve as a “venue” for social interaction, sociability, conviviality, and the enactment of community (Johnson & Glover, Citation2013), all bracketed by varying needs, opportunities, and/or assets (Arefi, Citation2016), in the best case, supporting the creation of a kind of urbanity that Richard Sennett defined as constituting places where strangers can meet (Sennett, Citation1977).

The fluctuating nature of this relationship between the physical and the social is accentuated in a recent book that surveys various conceptualizations of urban space in, Helsinki, Manchester and Berlin, where the author concluded that while the interplay between the social and the physical may be considered simply as foreground and background, yet, conceptualizing public urban space is still an intriguing and complex task wavering between, the elevated conceptions of architects, urban designers, planners, on one hand, and, the realities of the “Lived Space”, on the other (Lehtovuori, Citation2016).

Henri Lefebvre had given a salient understanding of the relationship of space and action, in the form of a triad of, “lived”, “perceived”, and “conceived” space. As he explained, Space is, at the first (i.e. affective bodily) level “lived”, just as in direct verbal communication; then, at a second level, its politico-social meanings are perceived; and, finally, the whole is condensed into a general “conceptualization”. Then, it is these conceptualizations that in the case of the monument, transform the actors, those experiencing that monument, into subjects (Lefebvre & Nicholson-Smith, Citation1991).

Artists, architects, urban designers, or for that matter, anyone involved in the shaping of public urban space, needs to form a better understanding of such conceptualizations of “public urban space”. Such conceptualizations, in turn, cannot be understood without the interface of Language; by that I mean, not only ordinary language, but a nuanced language of criticism, something that has been so far lacking in the discussions concerning urban public open space. Rigorous techniques of linguistic analysis, developed within the field of Structural Anthropology, can be useful in forming a better understanding of such conceptualizations, I would argue.

In short, discussions of Public Urban Space have yet to take, “The Linguistic Turn” (Rorty, Citation1967). While architectural practice gradually since the 1970’s had become deeply influenced by “The Linguistic Turn”, that is, by the ascendency of methods of treating philosophical questions, not as questions of logic, but as linguistic problems, urban design, on the other hand, had remained, in general, more immune to these developments, and more faithful to the foundational mainstream, psychological (perceptual-cognitive) (Lynch, Citation1960), anthropological (Rapoport, Citation1982), and Social-Behavioural research methods (Lang, Citation1987).

Therefore, the need for, on the one hand, a new “Criticism of Language”, and, on the other hand, a new and expanded “Language of Criticism”, motivated some recent research into reconstructing a new language of criticism that can more adequately describe and account for a range of practices that seemed to defy consideration within pre-existing paradigms. This has been done in the fields of sculpture (Krauss, Citation1979), and, architecture (Tafuri, Citation1990); two disciplines that normally coalesce and unite within urban design practice for the integrated production of open public urban space.

The work presented here, takes the cases of four recent urban design projects undertaken in the city of Amman in the period, 2002–2008 for the design of open public space, and tries to develop a language of criticism that can contribute towards the future production of a metalanguage for describing and analysing urban design projects that are directed at the creation of public outdoor urban space. The guiding thread in this endeavour moves from sculpture, to architecture, finally bringing the whole to bear on the design of these four urban public spaces. The objective is to initiate a process of conceptualizing open public urban space, particularly by weaving a thread between the physical and the social, through this proposed language of criticism.

2. Sculpture: the expanded field

The field of sculpture had taken the lead in this direction. Citing for examples the works of the likes of, Mary Miss, Robert Smithson, Richard Serra, and many others, Rosalind Krauss noted that sculptural practices since the late 1960’s had expanded far beyond sculpture’s traditional static and fixed role of being an object of adornment, commemoration, or embellishment of buildings or public urban spaces (Krauss, Citation1983).

Furthermore, she realized the inadequacy of the existing “language of criticism” to address the emerging practices. Therefore, in her seminal article, “Sculpture in the Expanded Field,” she argued for exploring what she termed the “expanded field” of sculpture, one that can encompass or be more inclusively representative of the evolving sculptural practices, particularly those that seemed to go beyond the classic notion of sculpture tied, as it was, to the logic of the monument. From her perspective, public sculpture, cannot be viewed as in the classic sense of a normally figurative and vertical material object with an essentially commemorative function linked to a particular site, such as a statue, or, for that matter, if I may add, any figural object of adornment or commemoration placed within public urban space, such as a memorial column, or obelisk, and the like. Rather, sculptural works, needed, in her view, to be considered in an expanded field; a field defined by relationships between words, things, and their opposites, and contraries, albeit not delimited by them (Krauss, Citation1983).

As she explained, within modernism, by the end of the 1960’s, sculpture had already become dissociated from site, i.e. siteless, placeless, nomadic, and even formless; acquiring a certain negativity by becoming focused rather on exclusions, that is, defined by what it is not: not-architecture, not-landscape. In her own words: “it [i.e. sculpture] was what was on or in front of a building that was not a building, or what was in the landscape that was not the landscape [italics mine]” (Krauss, Citation1983, p. 36).

To structure the “language of criticism”, Krauss constructed a “semiotic square”; using a set of binaries, their opposites and their contraries: landscape, not-landscape, architecture, not-architecture; in order to outline what she considered to be an “Expanded Field” of sculpture (). She then explained: “By means of this logical expansion a set of binaries is transformed into a quaternary field which both mirrors the original opposition and at the same time opens it up. It becomes a logically expanded field [italics mine]…” (Krauss, Citation1983, p. 37). The result was the mapping of an expanded field where “Sculpture” was no longer the privileged term at the centre of the field, rather, having its logic suspended together with three other terms: “Site-Construction”, “Marked Sites”, and “Axiomatic Structures”; together forming a quaternary expanded field of practice.

Architecture, not-architecture; landscape, not-landscape; the use of binaries and their contraries is a device used by mathematicians, and semiologists, but it has a genealogy leading back to Aristotle, adapted by Ferdinand de Saussure (1857–1913), and Claude Levi-Strauss (1908–2009), for the “Structuralist” study of Language and Myth, respectively. Following the pioneering work of De Saussure in Structuralist linguistic analysis, Levi-Strauss laid the foundation for the Structuralist study of Myth, which in turn paved the way for the Structuralist study of contemporary society, such as in the work of Roland Barthes (1915–1980).

After constructing her own set of opposites and contraries, Krauss represented it with a diagram being a square whose nodes correspond to the four terms that form the nodes for the system of opposites and contraries; often termed, “semiotic square” (again refer to ). Then, with her “semiotic square”, she was able to describe the “Expanded Field” of Post-Modern Sculpture, situating different practices that were difficult to conceptualize within the modernist paradigm (Krauss, Citation1979).

Krauss’s work, paralleled the writing of Manfredo Tafuri, who also employed similar Structuralist analytical methods in trying to come to terms with an array of architectural practices that he identified as Postmodern; hoping to develop a language of Criticism that can describe the emerging architectural practices which he saw as primarily being “linguistic”.

3. Architecture: the linguistic turn

In the seminal lecture, “L’Architecture dans le Boudoir”, presented at Princeton University in 1974, Tafuri worked to map out the emerging field of postmodern architectural practice using tools derived from the then emergent field of linguistic analysis (Tafuri, Citation1990). As he explicitly stated, he was aiming at creating a productive tension through the production of a critical language by means of which the language of criticism can be questioned. What Tafuri had in mind was the then recent works of architects like, James Stirling, Robert Venturi, Aldo Rossi, John Hejduk, Peter Eisenman, among others.

Tafuri divided the architects under consideration into two groups; those who wished to speak, and those who wanted to be silent; a division that fits neatly with the notion of architecture as language. For him, the former group, like Stirling and Venturi, had embarked on their search for an architectural language that tries to communicate by recourse to the assembly of fragments from what to him (i.e. Tafuri) is a lost language, one whose meaning can no longer be reconstituted. The latter group, however, like Eisenman and Rossi, seem to celebrate the “Autonomy” of the discipline which for Tafuri is but a means to safeguard their work against the process of reification, by opting for communicative “silence”. Tafuri saw the former response as an “Affirmation”, while he considered the latter a kind of “Negation”.

The dense content of Tafuri’s analysis prompted Ana Maria Leòn to reconstruct Tafuri’s language of criticism in a more lucid form (León, Citation2008). In her recent article, “The Boudoir in the Expanded Field”, Leòn used Tafuri’s language of analysis, alongside Krauss’s notion of the “Expanded Field”, to create a more graphically-structured imagining of what can be considered an expanded field of architectural practice by creating a semiotic square similar to the one Krauss had created for the field of Sculpture. Using Tafuri’s analysis, and following the footsteps of Krauss, she constructed her own “semiotic square” with the binary: Form, Concept; and their opposites and contraries: Form, not-form, Concept, not-concept. With those sets of oppositional binaries she created a quaternary field, one suspended between four other terms: sign, allegory, autonomy, type. The result is shown in .

She then related those terms (concepts) to the architectural practices of those architects mentioned in Tafuri’s text. So, “Sign” and “allegory” were considered as attempts at the formulation of an affirmative language with the intention of “Speaking”, even if in different ways; while, “Autonomy” and “Type” were considered by Tafuri to result in “Silence”, even if not the intention of the designer, as is the case of Rossi, for example.

Roland Barthes, whom Tafuri cited, identifies “Myth” as a second order semiological system. For Barthes, a first level of signification constitutes language of signs, then by a second order of signification, myth is created. In other words, the first-level coupling of “Signifier” and “Signified” produces “Sign” ; then, this “Sign” enters into the second level of signification, acting as “Form” to be recreated by filling it with “fresh content”. The result of this union is called a “Concept”, whereby mythical content is produced (Barthes & Lavers, Citation1957). This is shown in . In the diagram of our semiotic square shown in , “Sign” is located halfway between “form” and “concept” to indicate that it is the joining of both in a second-level signification. The narrative can be summarized as shown in .

Table 1. Diagram explaining Barthes understanding of Myth as a second order semiological system

Table 2. Partial summary of Leòn’s analysis, by author

I therefore propose to use Leòn’s diagrammatic analysis, with its initial binaries of, “form”, “concept”, and their contraries, “not-concept”, “not form”, to be the cornerstones of the initial square, yielding the resultant categories: Sign & Allegory (speech), Autonomy & Type (silence); but, with the addition of four more equivalent terms, ones that would match with the overall character of the four projects selected as the study cases for the recent design of open public urban space in Amman: Convivial, Poetic, Spectacular, Mnemonic; in the manner shown in .

Table 3. The quaternary semiotic field (urban design related to architecture), by author

These four corresponding terms/concepts are not posited a priori, rather, derived from the study cases themselves with the benefit of hindsight. So, by looking today at these four projects and how they evolved, in terms of the lived space, and their dominant uses, it is possible to posit these four dominant uses/conceptualizations. More about this in the following discussions of these projects, discussed not in order of start or completion, but in the same order as listed in .

3.1. Rainbow Street: site of conviviality (form, concept)

Amongst the four projects, Rainbow Street Project is a popular success, popular both with local residents, and, to an even bigger extent, with foreign tourists (European and American), nightly bustling with activity. Commercial establishments continue to multiply ever attracting bigger crowds of strollers and coffee shop and restaurant goers, to the extent that traffic is becoming ever more difficult as the days and months go by. The Street itself, Rainbow Street, is a local street but it is a spine of vehicular and pedestrian circulation that cuts through the older part of Jabal Amman, a neighbourhood with great symbolic capital embodied in the rich and significant social and architectural heritage, particularly that part of the history of the city of Amman dating to the time of the Emirate of Transjordan (1921–1946), and early independence, 1940’s and 1950’s. The name “Rainbow” is a popular name given to this street after one of the old movie theatres that used to be located along this street, although the theatre itself has closed down.

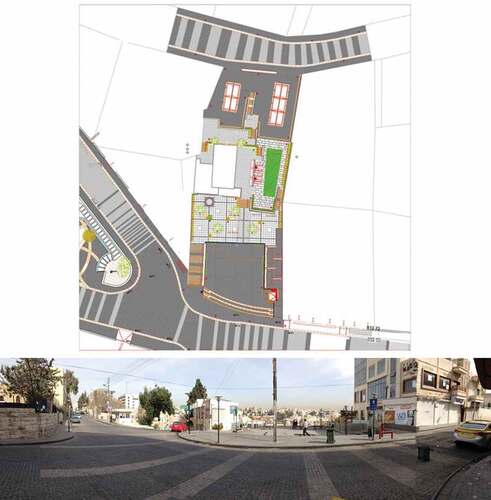

The idea of capitalizing on the area’s rich architectural heritage has been around for some time, and several individual private projects have already proven a success with local community and tourists, however, for the new mayor, sworn into office in 2005, it offered an opportunity to present a new agenda and a new vision of city improvement within a new paradigm, titled, as it was: “A City with a Soul”; less car-dominated and more pedestrian friendly, in tune with international trends abroad, such as was being attempted in London, usually a key source of emulation for Jordanian Intelligentsia, considering Jordan’s long-standing political and cultural links. A noteworthy example is Jan Gehl’s (2004) report, “Towards a Fine City for People”, being the result of his study for the improvement of London streets to make them more pedestrian friendly, later adopted by the mayor elect Ken Livingston as part of his re-election campaign in 2008 (Hill, Citation2014). In a similar vein, Rainbow Street Project (2005–8) entailed the upgrading and refurbishing of the main local commercial street that cuts through the old historic neighbourhood in Jabal Amman, being one of the older and richer neighbourhoods of Amman. Here, the urban space of the street was cleverly redesigned and refurbished through a series of design interventions: proper realignment and resizing of the street and the sidewalks, traffic calming through stone paving of the Street, improving and upgrading the sidewalks with more attention to paving, planting of trees, street furnishing, signage, and the creation of small public gardens and viewing platforms (). Since, it is the main commercial street in the area, and aided by the significant physical upgrading, commercial retail in the form of restaurants and coffee shops flourished. Observers correctly noted, “…, judging by the amount of traffic it generates, and the booming commercial activity in the area, the project, is deemed a success” (Al-Asad, Citation2011).

Figure 3. Rainbow Street: (above) architectural plan, and (below) view of street corner (notes: courtesy of Turath Consultants).

Like Venturi’s dependence on the pop-architecture language of the commercial strip, the physical language of the space in Rainbow Street is similarly dependent on the signs and billboards of the numerous commercial establishments that crowd along the street, while the few refitted heritage buildings float amidst the urban space without much significance or impact on the street scene. Nevertheless, the urban space here has a quality of urbanity that fits the description of urban as “a place where strangers can accidentally meet” (Sennett, Citation1977); in this case, qualifying the place, that is, Rainbow Street, as a Convivial space.

The physical form of the space is not as pure or as abstract as in some of the other projects presented here, but it is strongly idiosyncratic; each bit and fragment competing for attention since this is part of the commercial deployment valid here as in Venturi’s Las Vegas Strip or the Route 66 (Venturi, Scott Brown, & Izenour, Citation1977). This deployment of signs succeeded in creating an urban public space out of merging the first-order language of the signs (signifier + signified) into a second order mythic language by embedding the weak formal, and strong commercial language, making it fit for an array of social practices, performed daily, and weekly, over and over again claiming and reclaiming the rights of the users to this stretch of urban public space.

3.2. Culture Street: site of allegory (not-form, not-concept)

While this project is presented here as second in sequence, it was, however, the first project in terms of design and construction, making it in fact uniquely different from the other three discussed here, carried out, as it was, under different prior Municipal Administration than the other three. In 2002, the Amsterdam-based architect Tom Postma was commissioned by Greater Amman Municipality (GAM) to design “Culture Street” which is a 360 m long and 15 m wide street at the heart of the banking sector area of Amman, to mark Amman’s selection as the Arab Capital of Culture 2002. This was the first among the projects under examination to be completed. Postma transformed the street into a pedestrian boulevard creating seven areas, each accentuating a specific element: the obelisk, a shaded meeting place with large sunscreen, a leafy area with seating, a sunken amphitheater, a kiosk area, and a round seating wall. As Mohammad Al-Asad noted, the project had a mixed public reaction, some of whom were largely alienated by the forms of the architectural elements (Al-Asad, Citation2011).

Like Hejduk’s extremely poetic masks (He & Peponis, Citation2003), the forms of this project are also poetically charged: obelisk, palm-tree-like steel shading sunscreens, amphitheatre, ceremonial stairs, and black basalt stone dominates. The forms themselves are, not-landscape, not-architecture; somewhere between “architecture” and “not-architecture”; “axiomatic structures,” as Krauss might consider it in her semiotic square. The Obelisk, the steel shading devices and the subterranean passage with central stair and side ramps, give an overall air of the burial complexes in ancient upper Egypt; something further accentuated by the black basalt stone cladding for the smaller walls and stone paving. So, one is left to wonder if there was a hidden metaphor relating to ancient Egypt, particularly if we begin to see the whole ensemble as a floating ship/island (of the dead?); not a far cry from Hejduk’s masks that are often accused of being transportable structures that have no relation to site. This reading would be further accentuated if we read the art pieces hanging at the walls of the subterranean sunken area as ancient “buried treasures” ().

Besides his poems, Hejduk’s masks have a tendency for the poetic, hence the Sublime. Whether it is his Piranesi-like aggrandizement of scale, such as in his “Devil’s Seat” piece exhibited at the Biennale, or his “House of the Suicide”, and “House of the Mother of the Suicide”, in commemoration of Czech resistance during the “Prague Spring” in 1968, the theme of death, burial, and afterlife, always can be easily conjured up.

Similarly, here at Culture Street, by noting the fragments: subterranean chamber, wide stair, ritual passageway, and obelisk; we meet the aesthetics of the “Sublime” in the classic sense of Longinus’s “Peri Hypsous”, [On the sublime] reintroduced in the Eighteenth Century by Edmund Burke, marking the transition from the neo-Classical to the Romantic era (Burke & Womersley, Citation1998). The forms are therefore extremely abstractly poetic; speaking an obscure language; the designer’s choice of a kind of “Sublime” aesthetics, being well-suited, possibly, since, as Burke explained, the sublime is an elevated style with a strong moral or ethical purpose; something that is highly significant in relation to the intentions and motives behind the project, being the celebration of Amman as “Capital of Arab Culture” for the year 2002. Inserting this language into the street space, however, is not without difficulty.

Therefore, the design of this open public urban space presents an architectural language, formulated in a poetic manner; axiomatic structures; not-buildings, not-landscape; not-sculpture (unless in an expanded field). With those axiomatic structures, the designer produced a spatial “field”, adequately charged, giving strong identity to the space; one capable of attracting the younger crowds, particularly children and skateboarders; a success sometimes noted with a vein of sarcasm. In my opinion, such an outcome is in considerable extent an inevitability arising out of the contradictions within the projects programme, that is, the demand for a literal representation of such a vaguely general notion as “Arab Culture”; one that, in reality, would probably be extremely difficult, if not altogether impossible, to achieve without downgrading the design into the usual pop-art kitsch, such as flags, plaques, murals, banners, statues of leaders, etc. Therefore, the designer was justified, I would argue, in opting for an abstract poetic language, a sublime language of form, one that could only be but allegorically representational.

3.3. Wakalat Street: site of spectacle (form, not- concept)

By 2006, the newly appointed Mayor of Amman, and the team of architects and planners populating the newly founded Amman Institute (AI), were eager to showcase their new vision for the city, as they had done for their Amman Plan initiative, with its slogan, “Amman: A City with A Soul”, and to reflect that vision in a number of projects at the level of public open urban spaces, such as the “Wakalat” (2007), “Rainbow” (2008), and “King Faisal I” (2011) Street projects (Beauregard & Marpillero-Colomina, Citation2011). Excited by the prospects of a commercial upturn, the merchants of Wakalat Street were equally supportive. So, soon enough, the street was transformed into a pedestrian-only street with a particular vision in mind, one devised along general urban design guidelines devised by the well-known Danish urban designer Jan Gehl.

Gehl’s successes in Copenhagen had led to him being commissioned to do a study on London’s urban spaces, a study that resulted in the (2004) report, “Towards a Fine City for People”, with guidelines that mayor elect Ken Livingston had adopted as part of his re-election campaign back in 2008 (Hill, Citation2014). Later on, the Municipality of GAM commissioned Gehl to draw up general urban design guidelines for Sweifieh Commercial area, one of the prime commercial areas in Amman characterized by strip commercial development covering an area around 50 ha, an area that was planned in the late 1980s as strip commercial development, which, by mid-1990s and afterwards, had become extremely congested with vehicular traffic.

Wakalat (Brands) Street was a wide vehicular street approximately 350 m long in the Sweifieh area, a street largely defined by the line of office buildings bordering the street along its length at street level; mainly occupied, at ground level, by fashionable “international brand” clothing stores; hence, the name “Wakalat” literally meaning “Brands”. Gehl’s general approach is well known through his numerous writings since, “Life Between Buildings” (1971, trans. 1987), and later by his book “Public Spaces, Public Life” (1996) in which he describes how incremental improvements helped transform Copenhagen from a car-dominated city to a pedestrian-oriented city over 40 years (Gehl, Citation1980).

Copenhagen’s Strøget car-free zone, one of the longest pedestrian shopping areas in Europe, was primarily the result of Gehl’s work. Strøget was converted to a pedestrian zone in 1962 when cars were beginning to dominate Copenhagen’s old central streets. Strøget became a pedestrian shopping street, which is in fact not a single street but a series of interconnected avenues which create a very large pedestrian zone, although it is crossed in places by streets with vehicular traffic. Most of these zones allow delivery trucks to service the businesses located there during the early morning, and street-cleaning vehicles will usually go through these streets after most shops have closed for the night.

Gehl formulated general guidelines for the commercial district wherein the Wakalat Street is situated. Later on, TURATH Consultants, a local consultancy firm headed by architect Rami Daher, was commissioned to undertake the detailed urban design work for Wakalat Street. In the process the street was completely made car-free, fully pedestrianized, repaved with interlock block tiling, with suitably designed street landscaping and furnishings: trees, planters, signage, lights, seating, and the works ().

However, after completion, retail business owners began to complain of a business downturn which they saw as a result of the pedestrianization of the street with associated problems of parking and accessibility. Therefore, in 2013, the street was partially reopened to vehicular traffic, and, then again later opening one lane to all traffic all day; a compromise lamented by some users, but welcomed by shop owners who had suffered a drop in the numbers of their clientele when the street was fully pedestrianized (Al-Asad, Citation2011).

The physical design of the street was simple, abstract, elegant, and well-executed, but the major drawback of “Wakalat” Street lies in the proportion of people to the size of the space. After its re-design, the street was not able to attract sufficient number of users to energize it. In his seminal work, “The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces”, William Whyte noted how oftentimes the problem with public urban spaces is not overcrowding, but, under-crowding (Whyte, Citation1979). Therefore, the concept of a liveable street remained an idea rather than a reality.

In our proposed “language of criticism, it is “form, not-concept”; since the concept of a liveable and lively public urban space never materialized. As it stands today, the project, and as can be immediately gleaned even from a distant look of a photograph, is more of a “spectacle”; a place where the form of a pedestrian-only shopping zone creates a kind of autonomous existence, a matrix, a syntactical grid, similar to the early work of Eisenman, particularly in the early villas where the syntax has become both signifier and signified; an autonomous form referring to itself; and within the interstices of this autonomous structure, humans can be no more than a mere coincidence.

As Tafuri argued, this communicative “Silence” is dependent on the use of forms that are abstract, elementary, and self-referential. Compared to Rainbow Street where commercial signage floats all over the place and the indoor spaces of the coffee-shops and little restaurants, flow out into the space of the street, here, the space of the street reminds of De Chirico’s or Rossi’s surreal-like drawings. Moreover, the regular spacing and rhythm of the different Outlets of the different international brands, e.g. Benetton, Zara, Dutti, etc., stand in highly orderly regimentation along the street, reminding of Eisenman’s gridded structures in his early villas. The result is a spectacle of autonomous form. The pristine language of form developed an expressive “Autonomy”, and the silence pervades the space, albeit a spectacular one, marked, not by the presence of the “Flanêur”, but by his conspicuous absence.

“What attracts people most, it would appear, is other people,” Whyte had perceptively remarked (Whyte, Citation1979). What would have been the ideal setting for the flâneur; a figure that emerged from the imagination of Charles Baudelaire in his essay “The Painter of Modern Life” (1863); being in the crowd, observing, yet uninvolved, or becoming “blasé”, disengaged, as Georg Simmel had argued in his “The Metropolis and Mental Life” (1903), is here absent, possibly for two reasons; firstly, due to under-crowding, and, secondly, by lack of signification; although it is not quite sure which, in this particular case, would be the cause of the other.

3.4. King Faisal I Street: site of memory (concept, not-form)

The King Faisal I Street is a historical commercial street at the centre of Amman, historically at the heart of what was once the Emirate of Transjordan, 1921–1946, under the British Mandate. Its existence spans the period between the end of Ottoman Rule, and the birth of an Independent Kingdom of Jordan in 1946. It acquired added importance as a commercial and transportation hub into the 1960s and 1970s; albeit later dwindling in importance as newer shopping and commercial streets and districts began emerging in more accessible less congested peripheral areas.

The space had two golden periods; an early one stretching through the Mandate Period, 1921–1946, were it often served as a ceremonial plaza, hosting parades of Arab Legion “Mounties” in official army uniform, accompanied by a panoply of marching music bands, and a few armoured vehicles, often commemorating the launching of the Arab Revolt back in 1916 by the Sherif Hussein in Mecca (). The second golden period for this street space is after the unification between the East and West Banks of Jordan into a single United Kingdom, in 1948, which transformed it into a commercial and transportation hub linking Amman to Jerusalem and other cities of the West Bank.

Figure 6. Amman: 24th anniversary of Arab revolt, celebration 11 September 1940. The parade in municipality square (notes: Library of Congress, Digital ID: matpc 20,881 http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/matpc.20881). No restrictions.

However, the memory of the early Emirate period is the more dominant one and gives this urban space its identity today in heightened form, particularly for the extant heritage buildings still standing today at both sides of the street, and the memory of the famed coffee-shops where crowds used to gather in the old days to listen to news of the war (WWII) broadcast over the few radios available at the time. A major loss, however, was the later demolition of the old Municipality building that was strategically located at one end of the urban space, with its balcony overlooking the street, where the Emir often stood to witness the celebrations.

The dire physical condition that had overtaken the place by 1990s was cause for fresh royal attention with the accession of King Abdallah II to the throne in 1999, who soon after alerted the newly appointed mayor to the need to preserve and upgrade whatever was left of the historic centre, beginning with the King Faisal I Street Plaza. The project was completed in (2011). The project entailed the upgrading of an area of 17,000 m2, executed in four stages. Merchants located in and in adjacency to the site repeatedly met with the mayor who continuously assured them that their businesses would not be adversely affected, and that the project would be undertaken in four stages in order not to interrupt the commercial activity in the area, and that the continuity of vehicular traffic access will not be compromised, during or after. The lesson of Wakalat Street was very much on their minds, I would suppose. Thereafter, streets and sidewalks were redesigned, upgraded, repaved, resulting in improved vehicular traffic flow, and improved pedestrian movement along its length ().

Figure 7. King Faisal I Plaza: (Above) Architect’s renderings (notes: courtesy of Turath Consultants), and, (below) a view showing street and commemorative explanatory plaque, June 2016 (notes: author’s collection).

The improved setting had a positive effect on reviving the social life of some of the old coffee houses, and encouraging the renovation and re-use of a number of extant historic buildings. Back in 2010, the Mayor of Amman gave his support to the project, saying: “This project aims at enhancing urban areas, preserving archaeological sites, reviving the downtown area, refreshing the commercial movement, and empowering the location in terms of tourism and heritage” (GAM, Citationn.d.). To capture and preserve the collective memory of the early days of formation of the Emirate, and/or its glory days, perhaps, even if not specifically verbalized as such, was on everyone’s mind.

Analogy with the notion of architectural “Type” that Aldo Rossi believed could establish continuity in the historic city is plausible. Indeed, the space of the street here anchors the morphological structure of the city centre and shapes it into a well-defined form; but the form is as notional as Rossi’s or Krier’s Typology. Moreover, while Rossi relies on a kind of analogic imaginary city capable of bringing forth a kind of “uncanny feeling” of déjà vu, derived by analogy with Jungian Types, represented by his dream-like sketches in the manner of De Chirico, there is nothing surreal about the drawings for this project, or the eventual design; rather, in spite of all good intentions, the urban space remains grounded in its present commercial realities. Today, the few old restored heritage buildings stand, near inconspicuous, vying for attention with the plethora of commercial advertising and signage.

The hopes of creating a second-order language, a mythical one, remains here suspended between, on one hand, the possibilities of a “form”, never sufficiently materialized, one that can open itself up to the foundational narrative of the young Emirate of the 1920s, and, on the other hand, possibilities for a straightforward embrace of the commercial life of the surrounding commercial establishments, as had happened in Rainbow Street project. The result is ambivalent; wavering between, on the one hand, the (faint) memory of the Emirate Period of the early 1920s with the fragments of the limited physical remains of heritage buildings, and, on the other hand, the vibrant commercial life of today; thus, lacking the mythical language of collective memory; in other words: concept, not-form.

4. Public urban space: towards a language of criticism

Two affirmatives and two negatives form the four corners for the semiotic square I am proposing (). Urban space is “convivial” when it is a combination of two affirmatives, form and concept; which signifies an abundance and supervalence of essentially convivial (often consumptive) practices, with an effective ability to attract crowds. Such was the case of Rainbow Street which succeeded in attracting crowds and sustaining their interest. The form of the space may belong to the everyday, nothing spectacular in the sense of design, no “starchitects” may be involved, yet the place is capable of sparking interest and attracting pedestrians to move about and linger. The layers of history that the place and locality embody, serve to imbue it with strong “first-order signification”, while the new uses rejuvenates the urban space with renewed (second-order) signification (refer to Table); in this case, a strong convivial one.

Urban public space is “Poetic” when allegory takes its position in the semiotic square as a combination of the binary, not-form and not- concept. Such was Culture Street; a rather ambiguous formal statement to represent an ambiguous concept. Unlike Rainbow Street which, despite its formal remake and redesign, continued to be a synthetic and integral part of the urban fabric of the surrounding neighbourhood, Culture Street, on the other hand, perhaps due, at least in part, to its own shape or morphology, appears more isolated from its surroundings. It seems to float over its locality rather than to be immersed in it offering an alternative reality, a hyper-reality, dissociated from site, much like Hejduk’s masks that are often criticized of being transportable, or siteless. It is a moment of extreme self-conscious design, with a clear representational intent, one that aims to transform, in a drastic way, a present setting with all its inertia and chaotic existence, into a world of order. It is, in brief, an architect’s own dream vision; an attitude both commonplace and all too familiar within the long history of the architectural design profession.

Then, in the interstices between the affirmatives and the negatives, lie the “Spectacular” and the “Mnemonic”. The first, the “Spectacular”, is form, not-concept; an affirmation of form over content. Such is the case of Wakalat Street Project; formal “Autonomy” not unlike Eisenman’s early villas, a pure syntactical assemblage of elements, such as column, wall, slab, and stair, intended to be strictly non-representational, in their most basic and neutral form, painted white (intended as colourless). The autonomy of form of the urban space is amplified by the lack of historical depth in the formation for this relatively new commercial area, and, the lack of historical and geographical specificity of the international brands that are represented in the commercial outlets lining up the urban space.

Thus while carrying the best intentions to mimic Gehl’s achievements in Copenhagen and London, yet, the project stops short of attracting the necessary crowds needed for a lively daily existence. The problem of “undercrowding” downgrades the project to the merely formal, the aesthetic, the spectacular. In the words of Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, it would be as much as an abstract machine, “an abstract machine [which] in itself is not physical or corporeal, any more than it is semiotic; it is diagrammatic … The abstract machine is pure Matter-Function—a diagram independent of the forms and substances, expressions and contents it will distribute” (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1987).

Lastly, but not the least, urban space is “Mnemonic” when “concept” takes precedence over “form”; as in the case of King Faisal I Street. The concept in this case is omnipresent in the site and its history. In such a case, architectural or urban design effort did not create a lucid new formal statement or gesture, but simply emphasized the site’s existing qualities. “Concept”, here, represented by the historical memory present in the site, took precedence over formal design interventions. Little needed to be done in terms of formal design since signification was engendered by reference to a parallel/analogical “imaginary” space-time continuum running along those remaining historical markers of the political history of the Emirate, and later the Kingdom..

It is mnemonic function, and it resembles Rossi’s understanding and use of architectural “Type”, a notion that parallels Carl Jung’s archetypes, albeit for Rossi a strictly diagrammatic abstraction. For Rossi, “Architectural Types” denote formal spatial organizations each of which carries the representation of a social collective practice, one that is historically present in the architecture of the area, and one that can, if properly re-presented, evoke, somewhat like Jung’s archetypes, analogical meaning in the collective memory.

However, as Leòn noted, in Rossi’s work the idea of Type “…denies the denotative qualities of the object and strives to be defined by meaning only (concept)” (León, Citation2008, p.76). Such was the case of King Faisal I Street Project where the urban space is straightforwardly (diagrammatically) used to conjure up memory of an “analogical” urban public space, one reminiscent of the glory days of the 1920s–1940s, depending, not so much on the strength of form, but on the memory of the secular ritual that once took place there, for the purpose of re-establishing its relevance to the current socio-political milieu.

In the end, I would argue that with the benefit of the proposed semiotic square, and the various oppositions and inversions it carries, it would be possible to better discuss urban design projects by reference to the spatial and the social, here referred to as form and concept. In the future it is perhaps possible to further extrapolate, and build upon this structure, in order to estimate the adequacy and appropriateness of designerly intervention in similar projects, particularly in relation to the history and morphology of the site and in relation to the programmatic requirements or aspirations of the stakeholders. Such a structured language of criticism can enhance future acts of criticism and/or evaluations of public projects that involve similar design or redesign of public urban space. Advancing the debate regarding the future of urban public open space, and the future of our cities, requires a more nuanced language of criticism. The effort presented here is, hopefully, a small step in that direction.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to acknowledge the contribution made by Dr Keith Johnston from University of East Anglia who, as reviewing editor, and through his patient and critical reading and commentary, helped me bring better focus and order to the initially submitted text. I also would like to thank Rami Daher for sharing project drawings, and the anonymous reviewers of this article for their constructive criticism.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Nabil Abu-Dayyeh

Nabil Abu-Dayyeh is Chairman of the Department of Architecture & Interior Architecture at the School of Architecture & Built Environment (SABE) at the German Jordanian University (GJU) in Amman, Jordan. He received his Bachelor’s degree in Architecture in Jordan, followed by MSc and PhD degrees in architecture both from the University of Pennsylvania, in Philadelphia, USA. During that time he developed a passion for the interactions between, philosophy, literature, art, and architecture. Later on, living, teaching, writing, and practicing architecture in Jordan, and briefly in Bahrain, spurred his interest in urbanism, and city plans; something that led to writings on Amman’s architecture and city planning. The work presented here aims to synthesize both interests; bringing the preceding interest in culture, philosophy, and language, into the realm of urban design, particularly, as it relates to the design of urban public space.

References

- Al-Asad, M. (2011). Three public spaces in Amman. Retrieved September 4, 2017, from http://www.csbe.org/three-public-spaces-in-amman/?rq=three public spaces

- Arefi, M. (2016). Deconstructing placemaking : Needs, opportunities, and assets. n.p.: Routledge.

- Barthes, R., & Lavers, A. (1957). Mythologies. london: Seuil.

- Beauregard, R. A., & Marpillero-Colomina, A. (2011). More than a master plan: Amman 2025. Cities, 28(1), 62–69. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2010.09.002

- Burke, E., & Womersley, D. (1998). A philosophical enquiry into the origin of our ideas of the sublime and beautiful : And other pre-revolutionary writings. London: Penguin Books.

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand plateaus capitalism and schizophrenia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota.

- GAM. (n.d.). King faisal street project. Retrieved May 20, 2008, from http://www.ammancity.gov.jo/en/resource/snews.asp?id=DF86BFA6-DA04-4CC1-BA24-%0A3D7458329D62

- Gehl, J. (1980). Life between buildings: Using public space. New York, NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

- He, W., & Peponis, J. (2003). Modalities of poetic syntax in the work of Hejduk. In Proceedings. 4th International Space Syntax Symposium London 2003 (p. 30–30.16). London. Retrieved July 01, 2017, from http://www.spacesyntax.net/symposia-archive/SSS4/fullpapers/30He-Peponispaper.pdf

- Hill, D. (2014, January 25). Jan Gehl on London, streets, cycling and creating cities for people. The Guardian. London.

- Johnson, A. J., & Glover, T. D. (2013). Understanding urban public space in a leisure context. Leisure Sciences, 35(2), 190–197. doi:10.1080/01490400.2013.761922

- Kostof, S., & Castillo, G. (1995). A history of architecture : Settings and rituals (2nd ed.). New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Krauss, R. (1979, October). Sculpture in the Expanded Field, 8:30. doi: 10.2307/778224

- Krauss, R. (1983). Sculpture in the expanded field. In H. Foster (Ed.), The anti-aesthetic: Essays on postmodern culture (pp. 31–42). Seattle: Bay Press.

- Lang, J. T. (1987). Creating architectural theory : The role of the behavioral sciences in environmental design. New York, NY: Van Nostrand Reinhold Co.

- Lefebvre, H., & Nicholson-Smith, D. (1991). The production of space. Cambridge, Mass: Blacwell Publishers Inc.

- Lehtovuori, P. (2016). Experience and conflict: The production of urban space - Panu Lehtovuori - Google books. New York, NY: Routledge.

- León, A. M. (2008). The Boudoir in the expanded field. Log, Winter (11), 63–82.

- Lynch, K. (1960). The image of the city. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Rapoport, A. (1982). The meaning of the built environment : A nonverbal communication approach. Beverly Hills: Sage.

- Rorty, R. (1967). The Linguistic turn : Essays in philosophical method. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Sennett, R. (1977). The fall of public man. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Stevens, Q. (2007). The Ludic City: Exploring the potential of public spaces. London & New York: Routledge.

- Tafuri, M. (1990). The sphere and the labyrinth : Avant-gardes and architecture from Piranesi to the 1970s. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Venturi, R., Scott Brown, D., & Izenour, S. (1977). Learning from Las Vegas : The forgotten symbolism of architectural form. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Whyte, W. H. (1979). The social life of small urban spaces. Santa Monica, Calif: Direct Cinema.