Abstract

This paper explores the spatiotemporal construction of modern Europe through its cyclical (non-linear and non-symmetrical) self-conscience within a perpetual state of crisis. Following Marramao and Merleau-Ponty’s conjecture, this construction is always opposed to the Other (or its Others), as the Abendland, and it only exists because of the projection of its gaze towards the East. Following a series of images, from the decadent Venetian paintings of the Tiepolos to the artificial suns of Laurent Grasso and other contemporary artists, we seek to unveil the intertwined forces of décadence and élan–which could be translated as “impulse”, “momentum” or “vigorous spirit”—that determine the continuous becoming of Europe. These images, reflecting a permanent moment of crisis, are especially relevant for the spatialization of a Europe, since their juxtaposition reverses the rhythm of a linear conception of progress. Instead, they show a recurrent cycle that keeps the unfinished European project in permanent realization.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

“In a convulsive moment for Europe, in which different forces and political movements question its current status, it seems interesting to reflect on the very idea of Europe. On this occasion, we will do it from an artistic and spatial perspective, investigating different images and texts that aim at exploring the essence of Europe, agreeing that its driving force and reason for being is a permanent process of crisis and opposition-integration of the Other. These images, inserted within the historical period that goes from the Enlightenment to our days, are especially relevant for a further understanding of a Europe, since their juxtaposition reverses the rhythm of a linear conception of progress. Instead, they show a recurrent cycle that keeps the unfinished European project in permanent realization.”

1. Introduction

‘Europe is a process, always in fieri, something that is indefinitely becoming truth, while facing a double risk: either to consolidate, still, as a center of irradiation or, conversely, to alienate itself, being attracted to a more powerful orbit. It is itself only when it is expelled out of itself. Hence the constant need for reflection. Logically, its fate may be expressed by an infinite judgment (‘Europe is not-Asia’), so it suits the ambiguity of the term Occidens (‘that which dies’—‘that which gives death’).’ (Duque, Citation2003, p. 439)

With these words, the Spanish philosopher Félix Duque states the first of his seven theses on the fate of Europe.Footnote1 As a developing reality—always under construction, never completed–, its evolving nature corresponds to a contraposition of extremes. This permanent movement between consolidation and estrangement may serve as a starting point for our text that departs from the negative, as it reflects the enduring inadequacy between the concept-Europe and the thing-Europe, that is, its geographical space. This duality is particularly relevant when the Old Continent is facing one of the most terrible challenges of its history: the redefinition of the European identity through the permeability of its borders (who has the right to Europe?) and its relation to the alien “others”. The situation seems to reinforce the assertion of the German sociologist, Ulrich Beck (Citation2003), who claimed that Europe itself would be rejected by the EU if it applied for membership; such are the deficiencies that this institution maintains and further demands. Recognizing in this idea a certain Toynbeean influence, the conditional proposed by Beck expresses a contradictory loop of optimism and pessimism, negativity and positivity.

This idea of a contradictory Europe has been explored by many authors and thinkers from several perspectives throughout history. However, to set a modern starting point around which the text can be articulated, Hegel’s alleged path of human/historical spirit following the curve of shadow that draws the course of the sun from East to West may be an illustrative beginning. Decadence appears as wandering, as a detachment, as a cultural process that runs in the form of its own eviction: Europe is the Abendland2Footnote2 where everything ends only to start again. The image is suggestive enough to start unveiling new considerations around a space immersed in a perpetual cycle of rising and falling, and which is unable to exist outside this succession. Emerging from this turmoil, this paper aims at exploring the spatiotemporal construction of Europe through its cyclical, (non-linear and non-symmetrical) self-conscience within a perpetual state of crisis yet always in contraposition with the Other (or its Others). It now seems a long time since the words on the tomb of Sir Christopher Wren in St. Paul were carved: (…) Lector si monumentum requiris, circumspice! (“Lector, if you seek the monument—look around you!”) In fact, Arnold Toynbee (Citation1948) reinvented this epitaph, substituting the original word “reader” with Europae, to argue that Europeans cared little about the process of degeneration in which they were immersed, insomuch as the whole world was “becoming Europe”, from the United Kingdom to the former East.

Thus, it will be argued that, in some important moments of the European space-time, there are fundamental keys that emerge as other-spaces—using Foucauldian terminology—that should be re-explored from modern, coexistent, and differentiable perspectives. Only when inserted in a heterotopic world, our initial assumptions become susceptible to multiple, complex, contemporary statements. This allows us to think of Europe as the place of encounters and alternatives, as a com-munitas,Footnote3 which involves a laborious dedication to the Other, the others, and our disposition to the nature of (donating) things. Cruz (Citation2011, p. 9) defined those who share a common identity-dissimilarity as “diachronic human communities”, whose subjects are united through history.

Before we continue, it must be pointed out that the conjecture about decline is not addressed here with the intention of repeating something that both detractors and defenders vehemently deal with, but to evidence that the problem is the drawling ditty that evacuates energy in forms and not in content. In fact, we pretend to extract some fruitful ideas—rather than certainties—that could serve as a starting point for a cartography of the limits of Europe. For this reason, the perspective of the negative pervades our interpretive methodological approach, as the logic of action is not juxtaposition, but deceptively regarding the edges of a particular reality, which configure its reverse at the same time. Following a series of artistic interventions and images related in some way to these limits—and always supporting our work with texts–, we seek to unveil the intertwined forces of décadence and élan—which could be translated as “impulse”, “momentum” or ‘vigorous spirit’Footnote4—that configure the becoming of Europe.Footnote5

The idea of decadence in Europe, as shown by Malcolm Bull (Citation2015), is a recurring topic that appears periodically after different episodes of Western history. To set the starting point in the Enlightenment implies to depart from a modern, self-conscious Europe, which is starting to consolidate the foundations of what it is and, above all, what it is not. Therefore, the immense quantity of possible images and references to illustrate this paper have been selected and situated between the eighteenth century and our days, with authors and artists who try to sketch a spatialization of Europe from the perspective of the alternate forces of decadence and élan, reverting the rhythm of a linear conception of progress which has traditionally ruled Western temporality.

The image of the Sun as an illuminating element, but distant and radically other, is used by these artists, who allow us to trace a visual path through these opposing forces situated at the very core of Europe. Every field of knowledge, every temporality or geographic condition would display its own set of images, but we dissolve these three environments in a clear analogy between the disintegration of the text and the atomization of society (Bull, Citation2015, p. 89) as captured by Nietzsche from the novelist Paul Bouget.

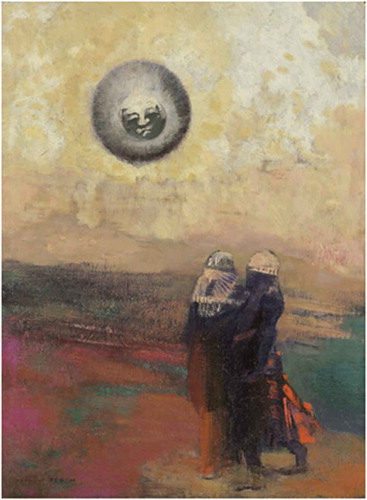

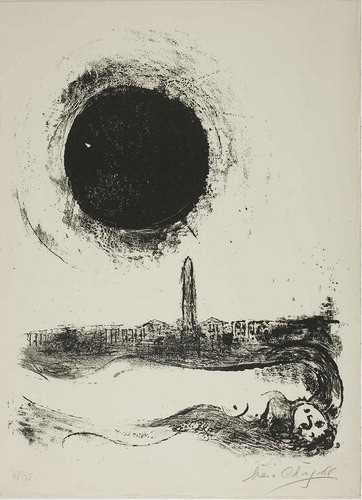

Hence, extending Spengler’s meagre analysis in The decline of the West of C. Lorrain (Figure ) and C. D. Friedrich (Figure ) we study the rise of the Enlightenment and its spiritual insufficiency denounced by the Romantics. With Jacques Barzun in his “From dawn to Decadence” we remark the hitherto scarce exploration of “otherness” in the work of the Tiepolos. In our sequence, the notions of past and reality, put in crisis, run parallel to two particular suns by M. Chagall (Figure ) and O. Redon (Figure ). We study both as cosmological catastrophes, in comparison between individual existence and collective imaginary (an idea of Europe… or rather Europes). Finally, although without a chronological order, we insert the crisis of the Modern experience by O. Eliasson in the Tate Modern.

Bull (Citation2015) studies the uses of the terms “decadence” and “decadent” between the nineteenth and twenty-first centuries in literature and arts, demonstrating a permanent concern, presence, and decline, with a rebound in 1975, attached irrevocably to Neoliberalism eclipsing any possible “otherness”. Our recovery of the Bergsonian “élan” follows a thrust of resistance, perhaps vacuous, in the conjunction of these images, in all their negativity.

2. North-west: the path of the sun

Bringing the image of the setting sun to the fore once again means to recall the “traumatic discovery” of the Other—and therefore, of the plural, or the “many”—that took place in Ancient Greece with regard to Asia (Carrera, Citation2015, p. 131). From that moment on, not only did Western philosophy emerge, as Carrera points out, but the new born Europe continued to expand its horizons, positioning itself towards other territories from an unequal, asymmetric perspective.Footnote6 Therefore, Europe constructed an image of itself that would be forever tied to Otherness. The Italian philosopher Giacomo Marramao, following Merleau-Ponty (Citation1964), says:

“What is, then, the European difference? Not just on the boundary between ourselves and others, which is tracked in any collective logic of identity: from the tribe to state, from the clan to the nation. (..) It is located rather in the fact that, while all other civilizations are characterized self-centrically, identifying as ‘the centre of the universe’ (..) Europe, however, is constituted by ‘a polarity internal between West and East’. The antithesis between East and West is therefore a mythical-symbolic exclusive property of the West, a typical Western dualism unverifiable in other cultures.” (Marramao, Citation2006, p. 63)

It is precisely because of this indelible difference that the sensation of progress starts to emerge. In many ways, the West has been regarded as the last land on Earth (finis terrae), beyond which lies the darkness of the unknown, as well as the hope for a better and more perfect existence. Revolving around the point where Atlas embraces the world,Footnote7 the cycle—anakuklosis, which in Greek means “revolution” (Herman, Citation1997, p. 15)—continues day after day. In this regard, the path of the sun simultaneously allows a spatial and temporal differentiation. If the East is the extreme which represents light, life, vitality, strength and illumination, the West is that of death and decline, as well as that of plenitude and completeness, in uncovering the promise of a new rise and a new cycle. Therefore, the symbolic meaning of both extremes led to a spatialization of the concept that societies had of themselves. In fact, many cultures have had their particular “Wests” not only understood as the place where the sun hides and where the day finishes, but as the mythical threshold to another unknown world. Babylonians, Greeks, Egyptians and Romans, among others, recognized the West as a symbolic construction related to these concepts of (in)finitude and fullness. (Jackson, Citation2006, p. 78) However, Christian tradition—and more specifically, the Augustinians–, driven by the eschatological narrative of salvation, regarded the space from East to West as coinciding with the direction of history, from Babylon to Rome (Jackson, Citation2006, p. 80). In consequence, the spatiotemporal cycle was interrupted and deployed as a sequential, finite line—from Alpha to Omega (Herman, Citation1997: 18).

Nevertheless, the modern understanding of the West as a community—in the sense of sharing a common (poisoned) gift–, and not as a mythical horizon, dates back to the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. This occurred when the conscience of a European civilization arose mostly among French and German thinkers—like Novalis or Schlegel, but also Rousseau or TurgotFootnote8 before them—who were particularly influenced by the ideals of the French Revolution and Romanticism (Ginzo, Citation2005, p. 31).

Nonetheless, Hegel was the one who filtered the classic and Judeo-Christian tradition through a Germanic perspective and aimed to give a response to the debate of a singular or multiple civilizations (Jackson, Citation2006, p. 88). He recovered the term Abendland (in opposition to Morgenland)Footnote9 to entitle Europe as the territory where world history reaches its end or its final plenitude. The notion of progress as a motor of civilization, as well as its dark reverse, decline, were thus linked to history and geography—time and space—within a Western-centric tradition, Both, equally terrible when taken to the extremes, are nonetheless unavoidable in order to understand the origins of the idea of Europe. This is why the image of the sun has been so habitual in Western thought, since it operates as an absolute point of reference to define its space in time, always in relation to Other(s). The sun never shines at the same time in the same way in Europe than in the rest of the world, and vice versa; a fact that is clearly pointed out during the dialogue between Peter Finkielkraut and Sloterdijk (Citation2008, p. 149): “geopolitics of the sun have become simple and plain geopolitics.”

The contemplation of the sun requires a specific gesture; semi-closed eyes, an unavoidable frown, pain, and effort all at the same time. The blinding light of noon makes it impossible to look directly at it, whereas visibility progressively increases as the sun goes down or during the first hours of the morning. That is the moment when things, as well as the star, can be seen calmly, without being annoyed by excessive brightness. At dusk, shadows unveil forms, their limits and contours, while the eyes of the viewer are not altered by phosphenes or other optical illusions. Sunset is the moment of reflection and pause, but also of understanding a present that has just escaped—like the owl of Minerva, flying “only with the onset of dusk” (Hegel, Citation1991, p. 23). This Hegelian thought finds its reply in his contemporary Caspar David Friedrich and his series of paintings of couples contemplating the sunset or the moonrise (the famous Moonwatchers.)Footnote10 Friedrich started painting these parallel scenes between 1816 and 1820, and he returned to the same motif during the decade of 1830, when his health was progressively deteriorating.Footnote11

Couples of men, women, or both stand quietly against bright, though melancholic landscapes, looking directly at the light source. However, behind the stillness of the scene and the apparent calm of these moments of contemplation, a profound rupture is represented: that between nature and human conscience, or even that between the joy of the sensual realm and the intellectual introjection of a human being expelled from the world. Indeed, Friedrich’s paintings do not portray any attempt at conciliation, since all fissures remain open. The serenity and the peaceful moment of contemplation experienced by the depicted couples is characterized by a sensation of Unruhe—again, a Hegelian feeling, meaning ‘restlessness’Footnote12—that invades the scene, as the observer is struck by an invisible agitation behind the pair and against the fading sky. This Unruhe manifests as a moving, internal force which precedes an action that will never take place in the picture. How many possible worlds are hidden behind this feeling of unease, restlessness, even anxiety? And what if this force remained latent and did not succeed in becoming an action? From this perspective, Friedrich’s work emanates from a negative, destructive aesthetic experience, sharing a common root with the Burkian sublime (Burke, Citation1757). Both, somehow, predicted the feeling of disenchantmentFootnote13 as well as the contemporary idea of Europe, which still clearly contains an important dose of restlessness and unease–especially against the Other or the unknown, like the sun that can be hardly looked at and is impossible to grasp.

Friedrich, like Turner, was interested in that gloomy, steamy light that announced the fall of the sun and could be regarded in an almost prophetic manner. With the advent of electricity, and thus of artificial light, the image of the sun lost its symbolic strength; it was desecrated in a way, as it was no longer the absolute source of light that ruled the rhythms of the world. Highly rationalized modes of production led to the disappearance of the division between day and night—one of the most urgent symptoms of globalization. Involute interiors, such as the factory, the bourgeois home, or the commercial passage configure the European space of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In these spaces, isolation from the outside provides a specific atmosphere of protection and enclosure—from communitas to immunitas.Footnote14 Despite being substituted by the myriad of electric lamps that illuminate the metropolis, the sun is already there, although it turns blackFootnote15 in the paintings of Odilon Redon and Marc Chagall—both before and after the World Wars. It no longer illuminates, but rather it confirms the association of the forces of decay (fin-de-siècle, in the case of Redon) with the image of a “cosmological catastrophe” (Larson, Citation2004, p. 132).

3. South-west: (G)lücke and possible worlds

Concerning the negative, the German-Korean philosopher Byung-Chul Han has indicated a certain philosophical legacy as co-responsible for the futility of seeking a place for utopias: joy (understood as good fortune or luck) and lagoon (coming from the Latin word lacuna, which means “pool”, “gap” or “cavity”) share the same origin in German. If Glück comes from Lücke, this will be the pair of concepts that will be explored throughout the following paragraphs, as a second dichotomy that lies beneath the very essence of Europe. If we have focused on the rocky and coastal horizons of Germany to contemplate Otherness from a geopolitical position, its southern counterpart, Italy, and specifically the lagoons of Venice, may serve as an accurate landscape to continue our journey.

As Spengler asserted—if we could ultimately confirm his words, as said in note 6–, every empire has its end. With the expansion and contraction of its influx, Venice has had to be reorganized, or better said, rethought. Such is the “idea of Venice” that its philosopher-mayor Massimo Cacciari outlined a few years ago. However, Lord Byron had already sung its decline in his Ode on Venice in 1815, and so did William Wordsworth in 1802 in his poem On the extinction of the Venetian Republic and Ruskin in the first chapter of The Stones of Venice (1851). Transforming the Marxian statement, perhaps the fatigue haunting Europe became chronic from that moment on.

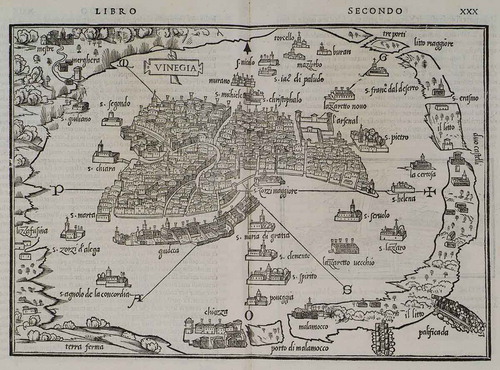

By observing the map of Venice by Giacopo di Barbari circa 1480, it can be deduced how the artist drew Venice looking towards the mountains, to Germany, stretching the space that runs from the mouth of the Grand Canal to the Arsenal. Barbari and his team spent more than four years measuring the entire city in order to create a representation that would be more accurate than more recent maps. The Italian architectural historian Manfredo Tafuri—who devoted a course to this drawing in Buenos Aires in 1981—found a very revealing element in one of those subsequent plans: when Benedetto Bordone (Figure ) mapped the city in 1528, he placed Venice in the center of an ellipse which formed the edge of the lagoon, with its axes crossing at St. Mark’s Basin in order to depict the city as a center, the center of the world. Tafuri immediately associated the date of the map with the publication of Thomas More’s Utopia (1526), who, in turn, used the image of a city located in the middle a lagoon, Mexico-Tenochtitlan. From the imagination of those who came from the New World, the encounter with the real Utopia takes place in Venice. Glückliche, or fortunate coincidences, occur in the Lücke, bringing a capital and a form of governance to Europe and the world. The Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas would go back to this image in his story of the pool, in which a group of Soviet architecture students, immersed in a very singular artificial lagoon (a floating, bottomless pool), move this capital to New York, by swimming opposite to the direction that such element, which had become a boat, should take.

Figure 5. Solario di Benedetto Bordone nel qual si ragiona di tutte l’isole del mondo, con li lor nomi antichi & moderni, historie, favole, & modi del loro vivere, Venice 1547.

Heterodoxy would unveil a relocation of the things that await to become. Such an image could appear with the figures of Giambattista Tiepolo, and one of his sons, Giandomenico. Calasso (Citation2009) said that the father painted décadence before it even had a name. The son inherited his father’s ability to trace what could not be seen, and both Tiepolos painted images on which to place the negative that alleviates the excess of surrounding positivity. Piranesi, the mad architect, used to wander through Giambattista’s atelier in Venice; hence the resemblance between hidden and oppressive vital needs expressed in the latter’s Capprici and the former’s Grotteschi.

Giandomenico, for his part, returned to Venice from Madrid and resided in the scarcely used summer villa at Zianigo, which was previously purchased by his father as a sign of social status. However, the son would do the same as Goya did with his Quinta, or Vasari with his house in Arezzo: he shaped his own reality. Misinterpreting the lives of these heterodox characters, in particular Goya, the English critic Philip Gilbert Hamerton published an article in 1879 that starts as follows: “(..) When an artist decorates his home (…) expresses its deepest and more sincere Self (..) [frescoes] are not hurried compositions intended to pass fleetingly and out of sight of the painter until he forgets about them.” This excerpt, drawn from the work of Rafael Argullol (Citation1994, p. 37), calls the contemporary reader’s attention to specifically indicate that the visible is the sick mind that finds delight in such atrocities, in the lack of beauty, or in a precarious sense of time: a Baroque that perishes against an emerging classicism returning to Greco-Roman antiquity to heal those immutable principles upon which to set an idealization and model of beauty.

Not only Heidegger, but most German authors equate the opposite of light—dusk, or darkness—to the depth of Being. Sloterdijk reminds that it was Hegel who traced the curve of the spirit/sun from East to West, like the sky represented in the ceilings of Würzburg (painted by Tiepolo for the archbishop Von Greifflenklau). The spirit (in this case, how Nietzsche understood it: prudence, astuteness, patience, simulation, the mastery of oneself and all that is mimicry) appears to enter the western sunset—as Duque saw also in Heidegger (Duque, Citation2003, p. 61). This is represented as a longing for the wandering of one whose life in European land is coming to an end. In psycho-pathological terms, decay is wandering, a detachment, and a cultural process that runs in the form of its own eviction. It is a gap (Lücke), a void, nihil: hence, the importance of taking into account Nietzsche while removing his heroism. Nonetheless, as George Steiner wrote in The Idea of Europe, as soon as one reaches the finis terrae, what defines the European identity is its reclusive character that “sees only shadows and abysses in the future” of this civilization (Vargas Llosa, Citation2004). Vargas Llosa (Citation2004) disagrees with him on this point because Europe is “in the world of today, the only great internationalist and democratic project that is under way and that, with all the deficiencies that may be pointed out, goes forward.”

Giambattista Tiepolo was despised for the last time with the ignominious, secret burial organized by the king and his court when he died in Madrid. Obliterated and forgotten, it seems that Tiepolo already knew his destiny and decided to arrange an entire sequence of resurrecting spells scattered through some of his greatest works. When remembering the spells to revive the painter two centuries later, through a whole series of anathemas embedded under the content that he had to paint under contract, it seems worth recalling the incisive analysis of Régis Debray (Citation2013) in his controversial article “Decline of the West?” Painter and civilization have immunized themselves through the regular assumption of a negative critique. That may be “the West’s greatest talent, its dynamism and its armour-plating” (Debray, Citation2013, p. 36), an expression that would be one of the few concessions made by the author along with a final conclusion: although he remains skeptical about what Europe represents, he recognizes it still goes forward.

As a woman, Europe’s beauty seduced Zeus, who adopted the form of a magnificent white bull that attracted the young lady and flew to Crete with her on his back. In Würzburg, Tiepolo (Figure ) recreated the Four Continents within a fascinating and theatrical space, reaching on the side dedicated to Europe the most revealing figuration of a West that looks at itself: some figures in a clumsy, vague, and melancholic attitude; an old, prostrate bull; a bunch of variegated elements drawn from the density of History; rests of dilapidated architecture (of the four continents, the European one is the only represented); and a woman—Europe—receiving gifts from Neptune.Footnote16 Following the magnificent work of Roberto Calasso (Citation2009), the Florentine writer needs, in order to understand this pictorial arrangement, the imposition to forget and erase something: a décalage, offset, or disagreement. This is necessary since it has taken many centuries to gestate the Being of the West, in distrust of itself. It can be seen in the trompe-l’oeil of a European-like character falling off the support where he is sitting. He carries a folder, probably with drawings or plans, and his misstep drops him in the worst place, only momentarily supported by the folder itself and a woodpile prepared to provide fire and death to those who venture in the Americas, represented by a strong woman riding a huge crocodile. The New World defends itself from foreigners. Calasso pays less attention to the other two continents but, regarding the whole, he does not miss the chance to operatically recite the opportunity of understanding between men, women, animals, backgrounds, representations, and beliefs: a true “cosmopolitanism”, he adds; however, without any “conciliatory attitude”(Calasso, Citation2009, p. 231).

Figure 6. Giovanni Battista Tiepolo. Apollo and the continents: Europe, 1750–1753. Detail of ceiling fresco in the Würzburg residence.

From an Asian perspective, the sun sets in Europe, and its definition appears in its name, Abendland. The New World is to Giandomenico, in the years following his return in 1791, pure scenery; a magic lantern, a fair booth to see from two outer perspectives: one trying to see through a small window, and the other denying the presence of our observation. None of the figures is aware of being observed. Father and son, as they often were, are portrayed in profile, but it is the figure of a pulcinella with disturbing eyes that monopolizes attention. A lost world that we, absent, petrified, and fascinated by a new one that is not reachable, have let go. Comedy dominates, though not for much longer. Pulcinelli were all over the walls of Giandomenico’s chamber, but the pressure of the enlightened Francophiles effaced the love that children and people in general had for them. They were able to adapt themselves, as a wildcard, to any character in the commedia dell’arte. Sloterdijk (Citation1994) recovered the expression “Translatio Imperii” to recapitulate the essence of Europe which matches what the imperialist commedia dell’arte irradiated for millennia.

4. Perspectives from other worlds

If Europe had been subsumed in one of the deepest crisis of its history after two World Wars, broken and contemplating the black sun of despair for decades, brighter suns would appear in other parts of the world; for instance, in the East, where the sun rises, particularly in the People’s Republic of China. The establishment of the Communist regime opened up a completely new rhetoric of progress and development.

Consequently, the image of the sun as a symbol of strength and progress is very present in contemporary Chinese cultureFootnote17; indeed one of the projects considered for Mao’s mausoleum had the shape of a huge red setting sun–as if the cycle had been closed. Paradoxically, today the contemplation of the sun in Beijing is almost impossible, due to the thick cloud of pollution that covers the Chinese capital.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the world—of course, if we adopt the Eurocentric projection—the United States of America emerged as the powerful extension of the old Abendland, operating as a more advanced version of the Europe that could have been and never was. In this regard, the Romanian-American illustrator, Saul Steinberg, offered a sharp, critical view on the issue from an urban perspective—his drawings were frequently published in the weekly magazine The New Yorker. From the 1960s on, Steinberg started a series of drawings reflecting the world view of Manhattanites, towards the East or the West and always using the sun as a referent. Steinberg’s earths are extremely compressed, as if the eye could see the Eastern and Western coasts of the USA at the same time. Everything in between is deformed, hidden or shown in an arbitrary way: Northern Europe and Africa are almost invisible, while Russia (or Siberia), China, Japan, or India appear as a thin strip in the horizon announcing the arrival at the American Pacific coast—in the drawing of the early 70s. In the end, emulating the old empires where the sun never set, Steinberg bitterly advances David Harvey’s definition of globalization as a “time-space compression” (Harvey, Citation1992).

These drawings have been copied and reproduced countless times. Curiously, The Economist’s front cover of 21 March 2009 showed an interpretation of Steinberg’s visions from an equally caustic Chinese perspective, depicting Europe as an insignificant island where expensive, luxury items (represented by Hermès and Prada) can be bought.

And yet, Europe continues thinking about its position in the world and its relation to the Other and the others. The cycle is in permanent movement, and these contradictions cannot be avoided. Meanwhile, European artists still continue to gaze at the sun; either with terror, like Laurent Grasso and his Soleil Double rising above the ruins of the warlike Europe and reflecting, once again, the terrible signs in the sky, or with pessimism, like Damien Hirst and his Black Sun made of death flies stuck on the canvas with resin.Footnote18 Other works, such as My Sunshine by the Macedonian artist Nikola Uzunovski or the impressive installations of Olafur Eliasson (Figure ) at the Tate Modern and Utrecht (The Weather Project and Double Sunset) seem to reflect the invalidity of this narrative of the path of the sun that we have been following. In fact, the sun can already be produced or “faked” through human work and reproduced elsewhere. By breaking the Hegelian path forever, there are now no absolute referents with which to rethink ourselves with respect to the Other.

5. Conclusion: tragic fate of primal acceptance as a new vital impulse of responsibility. moonlight versus the sun

According to Sloterdijk in Not Saved (Citation2017), Hegel was right, in the eyes of Heidegger, “to provide truth with a story”; but at the same time, the author of Time and Being (1962) thought that he was wrong when articulating it through a displacement from Ionia to Jena, and representing it as a “solar process” with dawn and sunset. If we take into account Heidegger’s comments about the history of truth and the fatal destiny of Being (Gestell), emanating from the state of affairs of our time, it is not like the path of the sun. Instead, it resembles “the burning away of a conceptual fuse that winds from Athens to Hiroshima” in 1946 and continues to our days. While searching for an end to these reflections, several images appear in the media scattered across the subcontinent, and reaffirming the diagnosis of Europe’s decline in the present. Maybe Abendland, the documentary of the Austrian filmmaker Nikolaus Geyrhalter is the best way to represent the European status quo, its deep immersion into the forces of décadence et élan, and—why not—its indifference towards its own situation. Five European cities are filmed at night revealing the advance of a democracy whose center of the world was here. Surveillance cameras, fences, brothels, and borders divulge our success or, better said, the decay of success. We may find a thousand stories to depict our “land of sunset” and still, these may not leave a clearing to find the arrow, but a gap (Lücke) where the fall, guilt, or feelings of decadence are evident. Meanwhile, the fear of the Other keeps affecting a society where xenophobic groups and parties proliferate, like the extremist Pegida (in English: Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamization of the West, Abendland) in Germany, which appropriates the notions of Europe and the West—understood as exclusive entities—for its own racist purposes. In this regard, the Schmittian logic of the enemy is being applied to its most terrible extreme, forgetting what Cacciari clarified some years ago: the hostis is always a hospes, that is, the stranger (the enemy, the other) is always a guest at the same time. “It is precisely by asserting my difference from the other that I am with him. The other is my inseparable cum” (Cacciari, Citation2009, p. 204).

Maybe Friedrich (Figure ) was pointing out something in his series of paintings. Europe probably stopped looking at the sun a long time ago. It is easier as well as less damaging to look at the moon, in a moment when the limit between the visible and the unknown has already been surpassed. Arthur Schopenhauer had already noticed that: “(…) the moon remains purely an object for contemplation, not of the will (…) the moon gradually becomes our friend, unlike the sun, who, like an overzealous benefactress, we never want to look in the face” (quoted by Rewald, Citation2001, p. 12). To close the parallelism of Europe regarding its own destiny and its own position in the world, maybe gazing calmly at the moon is a better depiction of the passive European society.

A community which prefers to find refuge under the harmless shafts of moonlight rather than face the sun—the same sun that will continue rising and setting—and accept its own contradictions and moving forces, and therefore recognize its links with the rest of the world.

‘It is not a coincidence that Europeans, when reformulating their historical project in the fifteenth century, begun to dream of desert islands.

As a good Western, one demands an island simply to restart. Desert islands are the archetype of utopia. (…) One cannot be a good representative of Western civilization without sharing the requirement of a second start’ (Finkielkraut & Sloterdijk, Citation2008, p. 153–154)

We could conclude, using the words of Sloterdijk, that this is the European élan. Europe should not miss its second chance to live up to the responsibility of being the focus of attention and source of courageous actions in order to avoid a last sunrise. Even if the European project cannot find its solution in the archipelago (Cacciari, Citation1997; Carrera, Citation2015, p. 130)—understood as a multiplicity of islands, united and separated by the sea at the same time–, it does offer another perspective on certain issues, such as those concerning the centrality or disintegration of the Union. The islands, in a way, must stop being islands in order to connect with the rest of the archipelago (or archipelagos, in plural), and so point to a new beginning, a Nietzschean “backlash”—which in German contains the vivid prefix referring to a counteraction, gegen-schlag—and to the very essence of Europe.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Marta López-Marcos

Dr. Marta López-Marcos, Ph.D., educator and researcher. As a member of the group OUT_Arquias, she has researched and published on space and negativity. She has participated in various international events, with collective works exhibited in the International Architecture Biennale Rotterdam 2012 and Venice 2018. She has conducted international research stays in centers such as TU Berlin, EPFL, TU Delft and BJUT. She has also collaborated in public projects and the development of urban policies in Andalusia, Spain.

Carlos Tapia Martín

Prof. Dr. Carlos Tapia Martín, PhD. architect and Associate Professor at Department of History, Theory and Composition in Architecture in the Higher Technical School of Architecture in Seville, Spain. Invited professor at Instituto de Arquitetura e Urbanismo Universidade de São Paulo, researcher at the Institute of Architecture and Building Science and the group OUT_Arquias, investigation in the “limits of the architecture”. He investigates the “symptoms of contemporaneity”, and he develops two investigations: “Critique and Epistemology of Future City’s Dream” and “Space and Negativity”.

Notes

1. The mythical origin of this negation is narrated by Roberto Calasso through the dream of the young Europa—later kidnapped by Zeus in the form of a bull–, in which two women were violently fighting for her. Finally, Europa was separated from Asia by the other woman, a stranger without name. (Calasso, Citation1990, p. 12–13) A similar vision is described in Aeschylus’ Persians: Queen Atossa, mother of Xerxes, dreams of her son in a chariot carried by two women. One is Asian, and stays calm, while the other is Doric and revolves violently until it breaks the harness (Cacciari, Citation2009, p. 200). The decadence of Europe and its tragic spirit, reflected in both dreams in contraposition with Asia, is studied by Nietzsche in The Birth of Tragedy.

2. The different terms used in the text to refer to Europe (Abendland, the West, or Occident) are undoubtedly diverse and have distinct connotations. However, and being aware of this, we have used them to define the same geopolitical unit.

3. About the concept of communitas, see Esposito, R (Citation2003) Communitas: Origen y destino de la comunidad. Madrid: Amorrortu.

4. The most recognizable use of the term—although much discussed and even reinterpreted by some authors, such as Gilles Deleuze—is that of Bergson and his élan vital, related to the complex generation and self-organization of life. In this context, we consider élan as an intrinsic force of impulse.

5. We are aware of the difficulty of not falling into the same trap that Massimo Cacciari avoided, in contrast to Carl Schmitt; the “tendency to mythological reconstructions of the European political space” (Carrera, Citation2015, p. 32). The references and images in our text are useful within an already established theoretical framework—that of the negative—that articulates an ongoing research on counterspaces.

6. ‘Progress, Turgot insisted, was “inevitable,” even if mixed in with periods of decline. Yet “progress has been very different among different peoples.” Here Turgot seemed to be taking the fateful step that led toward European and eventually a more generalWestern superiority, in which the developmental schema is, as it were, spatialized. Some nations in the present remain stuck in their historical backwardness while others show the effects of their historical advancement’ (Hunt, Citation2008, p. 63). This idea is also shared by Hegel (Citation2001).

7. “And here, here is the man, the promised one you know of -/Caesar Augustus, son of a god, destined to rule/where Saturn ruled of old in Latium, and there/bring back the age of gold; his empire shall expand/past Garamants and Indians to a land beyond the zodiac/and the sun’s yearly path, where Atlas the sky-bearer pivots/the wheeling heavens, embossed with fiery stars, on his shoulder” (Virgil and Day Lewis (transl.), Citation1986, p. 184).

8. Turgot also discussed the progress towards the West even before Hegel. He was the first to suggest that “the civilizing process had reached its height in modern Europe”, overcoming “the barbaric and savage part of its collective personality” (Herman, Citation1997, p. 25).

9. The German term Abendland (literally meaning “the land of evening”) was first introduced as a synonym of Occident by the German theologian Caspar Hedio in 1529 (as the archaic plural Abendlender). Since then, it has been used—and discussed—by many writers and thinkers, especially those related to the German world (Martin Luther, Hegel, Oswald Spengler… and more recently Massimo Cacciari or the Austrian filmmaker Nikolaus Geyrhalter). The ideological connotations of the term are quite ambiguous, having been recently appropriated by the xenophobic German group Pegida.

10. An exhibition about the series was organized under the same title, between September and November, 2001 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York (Rewald, Citation2001).

11. As an anecdote, it is worth remembering that the work of Friedrich was highly appreciated by the highest spheres of Russian nobility and literature, his most renowned patrons being the Grand Duke Nikolai Pavlovich (who would become Tsar Nicholas I some years later) and the writer Vasily Zhukovsky (Rewald (ed), Citation1990, p. 4).

12. “Hegel employs this term Unruhe frequently throughout his corpus to characterize negation, even as early as the Phenomenology, where, in the concluding pages, he speaks of the self-alienating Self as ‘its own restless process [Unruhe] of superseding [aufheben] itself, or negativity [Negativität]’. The restless nature of negation thus inheres in the notion of Aufhebung. It agitates, it does not stay still. It persists like a current, but remains as invisible” (Hass, Citation2014, p. 122).

13. Disenchantment (Entzauberung) as a symptom of modernity has been studied by many authors and thinkers. Although taken from Schiller—another German romantic–, Max Weber (Citation1999) is the one who develops the concept in 1919, by referring to the progressive cultural rationalization and desecration of the mythical factor in Western modern society.

14. Sloterdijk (Citation2010) develops the search for immunity in a world where the human is expelled in his book Spheres.

15. It is worth mentioning the ideal of blackness in art formulated in 1970 by Theodor Adorno in his Aesthetic Theory (Citation2013). It is an art pervaded by dark colors, and thought of as the only art capable of salvation against the horrors of humanity (negative aesthetics). The paintings of Redon seem to anticipate this ideal.

16. “What was Europe, if not an extension of Venice?” (Calasso, Citation2009, p. 228).

17. 16 Many popular songs and texts make use of it, like/such as this traditional children’s chant: “I love Beijing’s Tiananmen/The place where the Sun rises/Our Great Leader Mao Zedong/Guides us as we march forward!” (Translation by Wu, Hung. 2005. Remaking Beijing. Tiananmen Square and the Creation of a Political Space. London: Reaktion Books).

18. Between October 2015 and January 2016, the Beyeler Foundation in Basel organized an exhibition called Black Sun, devoted to the influence of Kazimir Malevich upon contemporary artists. This line of research, though interesting, should be continued elsewhere.

References

- Adorno, T. W. (2013). Aesthetic theory. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Argullol, R. (1994). Sabiduría de la ilusión. Madrid: Taurus.

- Beck, U. (2003, March 10). ¡Apártate Estados Unidos.. Europa vuelve! El País. Retrieved from https://elpais.com/diario/2003/03/10/internacional/1047250814_850215.html

- Bull, M. (2015). The Decline of Decadence. New Left Review, 94, 85–15.

- Burke, E. (1757). A philosophical enquiry into the origin of our ideas of the sublime and beautiful. London: R. and J. Dodsley.

- Cacciari, M. (1997). L’Arcipelago. Milan: Adelphi.

- Cacciari, M. (2009). The unpolitical: On the radical critique of political reason. New York, NY: Fordham University Press.

- Calasso, R. (1990). Las Bodas de Cadmo y Harmonia. Barcelona: Círculo de Lectores.

- Calasso, R. (2009). El Rosa Tiepolo. Barcelona: Anagrama.

- Carrera, A. (2015). The transcendental limits of politics. On massimo cacciari’s political philosophy. In A. Calcagno (Ed.), Contemporary Italian political philosophy (pp. 119–138). Albany: State Universiry of New York Press.

- Cruz, M. (2011). Acerca del presente ausente. In C. F. Oncina & M. A. Cantarino Suñer (Eds.), Estética de la memoria (pp. 21–30). Valencia: Universitat de València.

- Debray, R. (2013). Decline of the West? New Left Review, 80, 29–44.

- Duque, F. (2003). Los buenos europeos. Hacia una filosofía de la Europa contemporánea. Oviedo: Ediciones Nobel.

- Esposito, R. (2003). Communitas: origen y destino de la comunidad. Madrid: Amorrortu Editores.

- Finkielkraut, A. (2008). Los latidos del mundo: diálogo de Alain Finkielkraut y Peter Sloterdijk. Buenos Aires: Amorrortu.

- Ginzo, A. (2005). En torno a la concepción hegeliana de Europa. Logos. Anales del Seminario de Metafísica, 38, 29–61.

- Harvey, D. (1992). The condition of postmodernity. Cambridge, Mass: Blackwell.

- Hass, A. W. (2014). Hegel and the art of negation. Negativity, creativity and contemporary thought. London, New York: I.B. Tauris.

- Hegel, G. W. F. (1991). Elements of the philosophy of right. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hegel, G. W. F. (2001). The philosophy of history. Kitchener, Ontario: Batoche Books.

- Herman, A. (1997). The idea of decline in western history. New York, NY: Free Press.

- Hunt, L. (2008). Measuring time, making history. Budapest: Central European University Press.

- Jackson, P. T. (2006). Civilizing the enemy: German reconstruction and the invention of the West. University of Michigan Press. doi: 10.3998/mpub.155507.

- Larson, B. (2004). The Franco-Prussian war and cosmological symbolism in Odilon Redon’s. ‘Noirs.’ Artibus et Historiae, 25(50), 127–138. doi:10.2307/1483791

- Marramao, G. (2006). Pasaje a Occidente. Buenos Aires: Katz.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. (1964). Signos. Barcelona: Seix Barral.

- Rewald, S. (ed). (1990). The romantic vision of Caspar David Friedrich: Paintings and drawings from the USSR. New York, NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art; The Art Institute of Chicago.

- Rewald, S. (2001). Caspar David Friedrich: Moonwatchers. New York, NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Sloterdijk, P. (1994). Falls Europa erwacht. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp Verlag.

- Sloterdijk, P. (2010). Sphären 3: Plurale Sphärologie. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

- Sloterdijk, P. (2017). Not Saved: essays after Heidegger. Cambridge; Malden, Mass: Polity Press.

- Toynbee, A. J. (1948). Civilization on trial. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Vargas Llosa, M. (2004, June 13). Una idea de Europa. El País.

- Virgil, and Day Lewis, C. transl. (1986). The Aeneid. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Weber, M. (1999). Gesammelte Aufsätze zur Wissenschaftlehre. Potsdam: Institut für Padagogik der Universitat Potsdam.