Abstract

Ethnicity is a problematic concept. For many non-Western cultures, history became a linear passage of names, dates and events without any pragmatic dimension. A vague territory under the name of tradition, with the connotations of home and authenticity, separates these cultures from the alienated modern world. In order to surpass this traditional/modern binary here in the domain of architecture, the first step is to come to the conclusion that these histories do not inhabit a continuous space. Foucault’s genealogical division of history as a method for creating a concept like “architectonic discourse” can be an apparatus to reach this goal. The advantages are to pluralise these linear histories and to surpass the rupture between ethnic and universal, and traditional versus modern division wrongly divided these territories into one as practical and the other as phantasmagorical. In this paper, their Foucauldian epitomes of resemblance and web of sympathy, difference and representation and finally a modern organic structure are searched in Persian architectural history.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The main problematics of Persian architectural history are first its political and dynastic periodisation and second its unsurpassable division into historical (traditional) and modern. In the first one, outside frameworks divide architectural history without any basis for conceptualising change as a genuine and internal aspect of this history, and in the second, traditional remains only a Romanic category outside contemporary concerns. This history can only be the reference for scattered practical concerns but not a site for cultural discourse. There is an urgent need for reframing this history. A solution can be to find a transitional stage between traditional and modern world. Eighteenth and nineteenth century Persian architecture shows traces of internal change into what is wrongly regarded a homogenous tradition. As an experimental approach, this paper searches there Foucauldian epitomes of resemblance and web of sympathy, difference and representation and finally a modern organic structure in Persian architectural history in search for alternative basis of historical classification.

1. Introduction

“Ethnicity” is a problematic concept when it comes to communicate with universalities. Under the name of root and tradition, it turns history into an enclosed space only for constructing cultural essentialism or socio-psychological shelters. Incommensurable differences represent it as the space of authenticity and home, where universal abstractions are seen as a threat to its identity. Centralisation of historical narrations, which is built around the themes of originality and purity, governs these monotone identities. On one hand, by creating an enclosed semantic space, centralisation takes the chance off this history as the conceptual site for debating the present, and on the other hand, it turns history into the lost stories of the past divided from alienated modern world. In order to break this unjust division, release cultures out of ethnic otherness and make this histories conceptual basis for understanding world of a culture, this enclosed space of ethnicity must be deconstructed. The centralisation and the homogeneity it represents can be challenged by abstraction which lifts this history out of concrete ethnic enclosure, as well as pluralism, albeit without destroying the possibility of a cultural position or resistance. Abstraction gives the chance to other histories in order to bridge the gap between universal and ethnic (particular). Pluralism, either in a structural or ontological sense, represents spatial differences which cannot be erased by the forces of dialectic, teleology and centralisation. In order to reach that point, the first step is to come to the conclusion that these histories in themselves do not inhabit a homogeneous and continuous space.Footnote1

The other challenge is the lack of spatial history. To introduce the spatial, both in the sense of “historicizing space or [to] spatialize history” (Elden, Citation2001, p. 3), would be to remove common narrations of others history from their closed linear space. Linear narrations reach only to the threshold of modern age ready to be interrupted by the alien force of modernity or modernisation. Ethnic histories are formless spaces narrated chronologically and only defined by the relative categories like traditional and modern, locals and others. The asymmetrical spaces between these divisions disqualify postmodern culturalism as the myth of equality as an answer. Spatialisation must go further than the division of cultures into modern versus traditional as has been the principal semantic division in most of the non-Western cultures. The problem is that both idealised tradition and alien modern stand beyond critical investigation. Only in this way, the otherness of these architectural histories can enter the spaces of difference and representation.

History must have forms. By historical form, it means “ordering principles” that override chronological order.Footnote2 These forms are not particular geographies or periods. These forms give the historical categories and agencies ontological dimension which first can find parallels in present and other spaces, and also they define the concept of change as the principle of history. To get rid of deadlock of ethnic and linear history, a radical gesture of rejecting is needed, but not as negative act in itself, but as a policy to open the room for a positive construction. In this paper, Foucault’s genealogical division of history as a method beyond its bonds to western culture is examined as an apparatus to bring other architectural histories into the space of difference and representation.

Foucault’s rupture of the history of knowledge into different epistemological discourses on a spatio-temporal basis has clear advantages over common approaches in history writing. First and foremost, it questions familiar groupings and divisions (Foucault, Citation2002a, p. 24) which give the illusion of a permanency named as tradition.Footnote3 The other factor is studying history on a spatio-temporal basis, which rather than a linear time-based history enables the interpreter to give a structural scheme of elements constructing the historical discourse (Dreyfus & Rabinow, Citation1988). This approach, rather than the natural connection of proximity and chronology, searches for the formatting principles that build phases of history. Finally, discursive division stands between empirical study and transcendental generalisation. While this method of studying of history avoids abstract generalisations, the level of abstraction opens the door to surpass the regional space and to build categories of meaning beyond ethnicity. The question of this paper is that, can Foucault’s genealogical reading of history be employed as a theoretical basis for the investigation of others’ architectural histories like Persian architecture? Does Foucault epistemic different create conceptual apparatus for narrating others’ architectural history? The hypothesis of this writing is that Foucault has not divided the history of the knowledge of a particular culture (the West) but has introduced a structural scheme of history which is applicable in other contexts. Correspondingly, this paper tries to show that on the basis of Foucault’s archaeological approach, we can read others’ architectural histories and potentially reach different architectonic discursive formations.

Persian architecture despite existing patterns of difference inside the course of its history is wrongly represented continuous and homogenous under the title of tradition. Under this unifying umbrella, these lines of difference are attributed to minor geographical and political differences unimportant to its stable spirit. This presumed stability is destined to be broken with an alien modernism, leaves it only as a channel for nostalgia, revivalism and superficial banners of identity. A channel to avoid this fatal death is to show that this architecture has representable patterns of change and discontinuity which enables conceptualisation and theorisation, potentially able to be used in contemporary debates. The idea of discourse as a structural scheme can be an apparatus in this regard.

2. Foucault and episteme

The history of knowledge comprises epitomes, each based on discursive formations. Discourse in Foucault’s terms “is made up of a limited number of statements for which a group of conductions of existence can be defined” (Foucault, Citation2002a, p. 131). Statements, “the elementary unit of discourse” (Foucault, Citation2002a, p. 90), unlike the “unit of a linguistic type” which constructs the discourse of linguistic construction, “is that which enables such groups of signs to exist and enables these rules or forms to become manifest” (Foucault, Citation2002a, p. 99). Foucault argues that

[discursive practice] is a body of anonymous, historical rules, always determined in the time and space that have defined a given period, and for a given social, economic, geographical, or linguistic area, the conditions of operation of the enunciative function (Foucault, Citation2002a, p. 131).

The discontinuity between different discursive structures suspends the presupposed unities which form the continuity of history (Foucault, Citation2002a, p. 31).

How then can we transfer this archaeological method of studying history to an architectural context? Can the phrase “architectonic discourse” become a concept to analyse architectural history? What does it mean? This term can be interpreted into two different but not distinct category of meaning. First, “architectonic” may refer to the structural formation of the discourse, that is the formal system of discourse in which elements (or statements) form the discourse. While Foucault indicates that “discursive formations” “are very different from epistemological or ‘architectonic’ descriptions” (Foucault, Citation2002a, p. 174), and his attempt to define statements as the “unit of a linguistic type” to achieve a kind of rule of discursive formation fails, the discursive differentiation, like those in The Order of ThingsFootnote4 and Discipline and Punish (Foucault, Citation1991), is based on a structural vision of discourse. Though not properly defined, he attempts to establish rules of formation in discourse. In rejecting æuvre and speaking subject as the principles of unity in constructing discourse, Foucault mentions that “we no longer relate discourse to the primary ground of experience, nor to the a priori authority of knowledge; but that we seek the rules of its formation in discourse itself” (Foucault, Citation2002a, p. 89). This structural curiosity rather than revealing discourse as the objective context of knowledge looks for the formative laws of a discourse. In this sense, architectonic discourse can be described as the structural formation of discourse, irrespective of its exterior reference.Footnote5

“Architectonic discourse” can also be understood as the condition of meaning which is made possible by a specific type of articulating discursive structure. This is another simultaneous perspective in exploring discourse; this time the focus is on the exterior references which discourse makes possible. This exteriority is understandable when studying history of knowledge, but what does this exterior attention have to do with non-representational and nondescriptive phenomena like architecture. Nevertheless, two kinds of references come into play, which transform the abstractness of architecture into an indicator of man and his surrounding condition. On one hand are the temporal socio-economical conditions which make a connection between social structure and formal, spatial and functional aspects of architecture; in other words, architecture as “discursive practices or as ‘events’ with sociopolitical implications”.Footnote6 On the other are so-called metaphoric references which connect architecture to a wider context of psychological and ontological meaning and create a kind of sympathy between man and the built environment. In this sense, architecture is not a completely inorganic structure, or as Hegel put it, architecture can be described through the paradoxical expression of “an inorganic sculpture”.Footnote7 Architectonic discursive division is a possible basis to connect the built environment to a more sensible social and ontological context. It might be a step towards the formation of the history and creation of forms in history for the cultures lacking it.

Time remains yet undiscussed. Foucault indicates that “[n]othing would be more false than to see in the analysis of discursive formation an attempt at totalitarian periodisation” (Foucault, Citation2002b, p. 165). Nevertheless, periodisation is the inevitable outcome of the conjunction of discontinuity and history. Foucault names discourses as “historical a priori”. He, however, declares that “this a priori does not elude historicity” (Foucault, Citation2002b, 144).

Foucault mused, and we also take as a final question: “what purpose is ultimately served by this suspension of all the accepted unities [?]” (Foucault, Citation2002b, p. 31). As he notes, “[such] systematic eraser of all given unities enables us … to show that discontinuity is one of those great accidents that creates cracks not only in geology of history, but also in the simple fact of statement” (Foucault, Citation2002b, 31), in other words, to leave the illusionary concept of continuity. Second, we must be “sure that this occurrence is not linked with synthesizing operations of a purely psychological [emphasis added] kind (…) and to be able to grasp other forms of regularity, other types of relations”.Footnote8 And lastly,

The third purpose of such a description of the facts of discourse is that by freeing them of all the groupings that purport to be natural, immediate, universal unities, one is able to describe other unities, but this time by means of a group of controlled decisions (Foucault, Citation2002b, pp. 31–32).

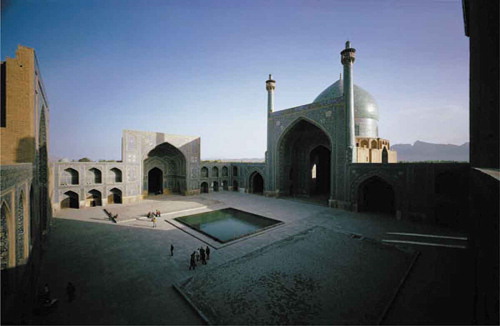

Tradition for non-Western cultures in one of those natural and universal unities which need to be deconstructed in order to narrate history through “controlled decisions”. In this respect and from architectonic viewpoint, Foucault’s archaeological method should be de-contextualised and detached from its cultural connections in order to be used as a method to investigate into Persian architectural history. This could be a channel to find forms and traces of discontinuity in a history which through vague concepts like tradition was regarded stable and homogenous. From a semantic point of view, this is an invitation to go beyond “for and against” traditionalism/modernism argument and search for a third space inside the tradition. This means a call for new traditions (Figure ).

3. The order of architecture

McNay notes that in The Order of Things “Foucault argues that, contrary to the common notion of the continuous development of the ratio from the Renaissance to the presents Western thought is in fact divided into three distinct and discontinuous epistemic blocks” (McNay, Citation1994, p. 54). Application of the frame used for the analysis of knowledge as something essentially descriptive to an architectural context cannot be without problem; however, the aim is to show that the ordering structure upon which Foucault proposed his triple discursive division can find parallel spatial/architectonic existence.Footnote9

“Up to the end of the sixteenth century, resemblance played a constructive role in the knowledge of Western culture” (Foucault, Citation2002b, p. 26). Different forms of similitude; “the adjacencies of ‘convenience’”, “the echoes of emulation”, “the linkage of analogy” and sympathy made the web that held the whole volume of the world together (Foucault, Citation2002b, p. 19). “By positioning resemblance as the links between signs and what they indicate (…), sixteen-century knowledge condemned itself to never knowing anything but the same thing” (Foucault, Citation2002b, p. 34). As is true for knowledge, the rich semantic web of resemblance (Foucault, Citation2002b, p. 20) represented in this form of discourse represents repetition of the “same thing” in its visual sense. Two issues are subject for concern: first, the basis and the image upon which this same thing represented, and second, the fact that the nature of the resemblance is based not on—let us call them—predesigned formal categories but on formless subjective and emotionally based notions of sympathy. In the former, a kind of archetypal form is expected to represent the same nature of things, while in the latter, a kind of atomism is the outcome of closed entities combined through formally indefinable lines of connection. This rationale is applicable to certain periods of architecture.

Concerning the first, Foucault himself put forward an unanswered question. He asked: “if things that resembled one another was indeed infinite in number, can one, at least, establish the forms according to which they might resemble one another?” (Foucault, Citation2002b, p. 19). However, Foucault rather than the forms of resemblance discusses the net that connects them together. He adds that “it is here that we find that only too well-known category, the microcosm, coming into play” (Foucault, Citation2002b, p. 34). The statements of discourse or, in a sense, the elements of discursive structure, are endless repetitions of microcosmic elements in a web of similitude. In architecture, this suggests repetitive use of archetypal forms and spatial units through a microcosm/macrocosm connection. The term “archetype” indicates the transcendental image of these units, which are based on cosmological similitude rather than referring to immediate spatio-temporal conditions or functions. Where there is no division, there is no immediate identity and difference since every element of a statement is the same as another.

An example might help to clear the discussion. Persian architecture is an endless and undifferentiated reproduction of the primary elements of Iwan (portal), Chārtāq (literally mean quadruple vaulted roof which means an enclosed or open dome chamber based on four corner pillars) and Shabistān (Hypostyle) in different forms and compositions (Figures and ). In this sense, to connect the very being of these elements to immediate function and condition, either socio-political or religious, is reductionist and misinterpretation.Footnote10 Looking through the lens of this spatial discourse, a semantics of this architecture is bound to investigate why these particular images and codes are represented as archetypal images in their pragmatic context. Yet, the archetypal dimension is only one semantic layer of buildings which finds its concrete meaning in association with a particular context (Khaghani, Citation2012).

The interaction between elements or the web of resemblance through repetition of the same things is the other side of this discourse. Rather than a predefined structure, sympathy, as a basis for the interweaving of worldly elements, prepares the ground for the so-called concrete conceptualisation of the world as a method of thinking (Kuang-Ming, Citation1997). It stands in contrast to the abstract method of philosophy and pure reasoning. In addition, the structurally indefinable forms of connections, due to emotional and situational basis of the relationship, represent a kind of atomism. This form of atomism is not a haphazard gathering of autonomous elements, but a situational connection between elements with a sensible attachment, not reducible to any form of generality.Footnote11 There is no pattern according to which elements find their position yet general logics lead the collective form. Formally chaotic, elements are individually positioned ones with no clear collective structure. Like a group of people gathering in a square, there is no collective arrangement, yet there is a possible subjective connection inside scattered groups. Therefore, it is more than random positioning of the individuals despite the absence of big structures. It is a form of anarchism—here anarchism does not mean absence of order and structure in its concrete sense of the word—which rejects central supervision and institutionalised organisation and place it with a subjective basis for the formation and conceptualisation of society. Medieval and Persian cities represent this concept of social organisation (Figure ).

Finally, referential meaning in this semantic system finds a particular form. First, elements represent an archetypal and general picture rather than partial meaning or function, possibly with a cosmological root. In Persian architecture, architectural space is named according to the season and time it is used (summer, winter and spring house and moon-light and night house [shabistan]) and the general formal features or position in the complex (three- or five-door rooms, ear-like room [gushvar] and pool house [hoz-khaneh]). In other words, the spaces do not reflect an immediate contextual meaning or functional reference. In a poetical sense, architecture, like the patterns of imagination in Persian literature (Shafī’ī Kadkanī, Citation1386 [2008]), comes into a web of poetical similitude which connects it to the wider cultural language, for example in Persian architecture, resembling a tower to a bunch of flowers (Guldastah), the eyebrow as the colonnade of the garden of the eye, the sky as the roof of garden kiosk and many others are common sensual and visual picturing of architecture in everyday language. This web of connections transcends architecture from an abstract structure to a phenomenon with cultural sympathies. In the context of interconnection between elements, it devalues the common assumption of the interpretation of form follows function, since the common image carries no indication of immediate content. A common and general form is lacking which might devalue structural regulation or semiotics as prefigured forms of signification. This is a key misconception on how to apply semiotics, hermeneutics or phenomenology to many cultural expressions since there are no pre-established codes for application. It is an organic process constantly changing through social groups belonging to different time periods. However, a structural approach as it explained here helps to avoid a dead-end culturalism and particularism as the explanation for the differences. There is not any intention here to name this form of organisation as communal, nomadic—as Deleuze may call it—arbitrary or anarchical or any other terms to avoid the prejudgements associating them.

Three different features can describe this architectonic discourse. The spatial elements are based on archetypal similitude which surpasses immediate practical divisions. These elements or statements are organised through formless connections and a web of sympathy based on situational conditions. And, the microcosm/macrocosm web of similitude between spatial divisions and other cultural features constructs a rich poetical complex. The web of resemblance and concrete cultural meanings accompanying certain archetypal forms set the logic upon which a discourse of Persian architecture can be defined. This discourse can be a basis to shape local—either geographical or time based—categories of architecture. To certain points in architectural history, this ratio had shaped the discourse of architecture. By searching this discursive logic, common classifications of fine and vernacular, politico-geographical divisions and functional categories dissolve into another logic of formation. This does not mean that identity groups are erased. Nonetheless, it is the nature of order in these discourses which evaluate these divisions and periodisations.

As Foucault notes, in the Classical age, “no longer resemblance but identities and differences” (Foucault, Citation2002b, p. 55) become important in the field of knowledge.

On the threshold of Classical age, the sign ceases to be a form of the world; and it ceases to be bound to what it marks by the solid and secret bonds of resemblance or affinity (Foucault, Citation2002b, p. 64).

From now on, every resemblance must be subjected to proof by comparison, that is, it will not be accepted until its identity and the series of its differences have been discovered by means of measurement with a common unit, or, more radically, by its position in an order (Foucault, Citation2002b, p. 61).

In this new episteme, “what has become important is no longer resemblance but identities and differences” (Foucault, Citation2002b, p. 55). From an architectonic point of view, structure appears as a set of identities and differences, that is to say, a structure with separated identities as elements and formally representable connective lines. In the Classical age, this linear structure is a descriptive representation of reality as it is conceived:

“[T]he fundamental element of the Classical episteme is … a link with the mathesis” (Foucault, Citation2002b, p. 63) analysis acquires a universal position (Foucault 2002, p. 63) and syntax becomes the essential part of making a table of knowledge. In this episteme, the microcosm disappears: “Representations are not rooted in a world that gives them meaning; they open of themselves on to a space that is their own, whose internal network gives rise to meaning” (Foucault, Citation2002b, pp. 86–87). There is no infinitive repetition of spatial units with cosmological images when one looks through this episteme to architecture but spatial complexes instead. Whether a country or a ruled territory, city, civil complexes or even a single building, these are bordered places made of articulated spatial units structured for a definite function. The microcosmic image of the previous architectonic episteme is replaced by a bordered and limited functional complex.

What is the difference, then, between the forms of referencing in this architectonic episteme? We can use a comparison with language to clarify the position of form and the types of reference in this system:

From an extreme point of view, one might say that language in the Classical era does not exist. But that it functions: its whole existence is located in its representative role, is limited precisely to that role and finally exhausts it. Language has no other locus, no other role, than in representation; in the hollow it has been able to form. (Foucault, Citation2002b, p. 87)

In the same manner, from an extreme point of view, architectural forms as lingual elements have no meaning in this episteme, in comparison to the imaginative net which fabricated the semantic net of the previous one. Unlike the atomism of former system with formally expressive elements, a complex is a defined system in which elements are defined through the function they play and their position within it. Elements are representatives and functionally substitutive without any intrinsic value. Here Iwan becomes only a gate or channel for entering the main space and domes a cover for congregational space. The concept of classification and formal patterns of communication are what differentiate this system, where structure is defined and elements are positioned relatively. In this system, an expressional representation between form and its function is expected. The reference point of meaning is already articulated as a function in current system. The use of formal expressions however suggests that this extreme point is impossible. A web of resemblance works beneath this functional articulation by the virtue of imagination. This reality rejects the sharp periodisation of these two epistemes, as it is seen in the case of architecture.

I would argue that in architectural domain, this discourse can be named as historicism in general sense of the term. By this, it means from a certain point in architectural history, which should not be matched with nineteen-century so-called classicisms, architecture turns into a spatio-formal language to be used in different context. Formal expression and functional pragma transportable out of their concrete context define this air of classism. For instance, late-Safavid architecture and afterward in Persian architecture shows the trace of this mode of classism; three domes are built in Shah Mosque and wooden Iwans are attached to garden kiosks for the sake of their formal and expressional features.

This episteme shows that potential traditions like Persian architecture before modern influences and westernification as it is called in Farsi have genuine modes of historicism as the traces of conscious reconsidering of its history. This means that before confronting the modern era, this architecture has pondered about form–space–function relationship in its architecture which deconstructs the myth of an unconscious tradition confronting an alien modernism.Footnote12 It enables this architectural history to become representable and potential to dialogue with modern paradigms.

Foucault’s third epistemological division, rooted in the modern era, is based on the notion of organic structure.

Organic structure, that is, of internal relations between elements while totality performs a function; it will show that these organic structures are discontinuous, that they do not, therefore, form a table of unbroken simultaneities, but that certain of them are on the same level whereas other form series or linear sequence. (Foucault, Citation2002b, p. 236)

In classical episteme, history was to deploy in a linear sequence to connect distinct yet continuous domains to one another. It was a general law which imposes itself on different subjects of “the analysis of production, the analysis of organically structured beings, and, lastly, on the analysis of linguistic groups” (Foucault, Citation2002b, p. 237), regardless of their intrinsic characters. However, in the third episteme, history is the analysis of modes of being “upon the basis of which they are affirmed, posited, arranged, and distributed” (Foucault, Citation2002b, p. 237), in other words, upon their organic structure. It looks into the inner law of a structure.

From a structural viewpoint, this third division introduces time as another dimension of organisation. Time breaks the linear division of complexes on the basis of defined identities and differences. In this episteme, “naïve formalisation of the empirical seems like ‘pre-critical’ dogmatism and a return to the platitudes of Ideology” (Foucault, Citation2002b, p. 238). It is comparable to what Picasso’s cubism and modern architecture brought into the domain of realist painting and divided and framed the spaces of classical architecture Collins (Citation1998). According to this episteme and due to the organic structure of the complex, it is not possible to place divided elements in a linear functional connection to others. Formalism and representational logic of previous episteme is replaced by functionalism and singularity of time–space in the last one. This architectonic discourse can be called modern in broad sense of the term. The notion of time reflects the architectonic bases of these three epistemes. The cyclical time is the framework for pre-classic episteme, the linear time and the notion of progress are what represent the notion of time and history in classical stage, and finally the interior time of a complex is the situational notion of time in modern era. It is worth mentioning that the timing, as Foucault might have put it himself, in architecture and knowledge is different.

4. Conclusion

Writing others’ architectural histories is a challenge. These are the histories which are narrated either chronologically through political dynasties or geographical and territorial divisions, or through narrating the building of certain functions. What is absent in all these are categorisation and periodisation based upon the inherent changes inside an architecture. By these changes, it does not mean only formal or minor spatial changes but also shifts in paradigms. The notion of tradition resists this notion of change which is another formless brand to categorise differences under one umbrella. This is not a claim against tradition, but against common modes of traditionalism which mark it as a concrete ethnicity bonded only to particular time and geography. This is a vague category ready to be interrupted by an alien world called modern. For architectural history to become a conceptual site for debating the world of culture, it is necessary to surpass these vague bonds and categories and build forms based upon genuine notions of change. This is an invitation to tradition beyond traditionalism. Foucault’s genealogical division of history can be an apparatus to think of parallel division inside architectural history.

Pragmatically history is a reference to criticise and get awareness of the current patterns of the present. This function cannot be carried out unless order, classification or conceptualisation forms patterns of change in relation to general patterns of the culture. This is a matter of construction rather than discovery. For the non-Western cultures, trained patterns of life—including products like architecture—suddenly faced an alien world of modern and transformed into an isolated pile of names, dates and stories without pragmatic answers for these pseudohistories. It is regarded either as an exotic site for psychological pacifism or used as the identity banner.

In my viewpoint, the first step to open the room for this space is to play with the borders which have built established disciplines and cultural divisions. I used the term “play” rather than “breaking” in order to show that more than deconstructive acts—wrongly with its destructive connotations—new language games are needed if alternative spaces must be constructed. For a while, postmodernism with the rejection of modern master narrations opened the space for the minorities to express themselves. Nonetheless, the fundamental problem is bringing these minorities into the space of representation.

Foucault archaeology of knowledge, more than epistemic division of knowledge in Western history, shows a structural pattern for building categories of meaning. These forms named as discourse can structurally be employed to investigate potentially into any history. Resemblance and web of sympathy, difference and representation and finally an organic structure with a net of time–space–function are notion which is applicable in architectural history as well. Nevertheless, the main argument against could be how these epistemic changes can divide a history which is named as tradition, presumably a world with minor changes inside a stable cultural pattern? The first answer is that tradition is itself a modern constructed notion. And more importantly, it is the question of possibility of true history without any sort of these forms which construct the notion of change and agency. This paper was an experience and needs to be employed in writing an architectural history. Other apparatuses can be used to create alternative forms and take others history out of “prison–house” of tradition in the name of wrong traditionalism.

Correction

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Saeid Khaghani

Saeid Khaghani finished his Ph.D. at the University of Manchester in 2009 in Art History, specialising at historiography of Persian Art and Architecture. His research interests are Persian architectural history and sociology of architecture. At present, his research focus is on Qajar architecture. He is currently lecturing architectural theory and history at University of Tehran. He has published a book on Historiography of Iranian architecture in I.B. Tauris, London and has a book in press entitled “Subject and Space”, on Iranian everyday life and two other books in Persian.

Notes

1. This means that tradition in itself have differences, are plural and inhibit ideas that can connect them to others which seem alien and unsurpassable. Homogeneity and continuity have become the main apparatuses to build essential narration for ethnic histories.

2. See Levine (Citation2015). Levine herself confesses that her use of the term as “ordering principle” is not intuitive to other literary critics. She argues against historicism and use of forms to surpass the binary of past and present.

3. As Foucault mentions: “tradition enables us to isolate the new against a background of permanence, and to transfer its merit to originality, to genius, to the decisions proper to individuals” Foucault (Citation2002a, p. 23).

4. The division in The Order of Things can be seen as three different structural formations at the same time as three different knowledge discourses. It cannot be said which one leads to the other one; a kind of simultaneous existence exists between form of discourse and we can call it content.

5. We are not going to set rules of formation—the effort which Foucault left himself—but to indicate a simultaneous existence of a structure rule in conducting discursive formation.

6. McNay, Citation1994, p. 54. He uses text as event, which we replaced it with architecture, considering the broad meaning of text.

7. See Hollier (Citation1989, p. 15). It is worth remembering that Hegel’s time sculpture almost equals body representation.

8. Foucault (Citation2002b, pp. 31–32). In the case of modern Iranian history in general, and art and architecture specifically, there is enough evidence to suspect them of being a product of the psychological condition of society.

9. As it is mentioned before, it is not a channel for total periodisation, but to show that there is trance of inner discontinuity in the context of a history and tradition which is regarded homogeneous.

10. This does not mean that function is absent in the definition of this architecture. It does not mean the form follows function, neither the other way around of postmodernism. Here function has also a structure and rhythm, which is matched with the elements of architecture and its collective net.

11. For a better understanding of the nature of this order, see: Alexander (Citation2002).

12. This is an argument which needs further discussion. It is in parallel to the argument of Tavakoli-Targhi in “Refashioning Iran” which invites to go beyond common notions of Orientalism in representing others’ cultures like Iran. His general argument is that in spite of representing a rigid and unconscious tradition ready to be interrupted by modern world, although with a look on what is happening in the West, Persian eighteenth and nineteenth centuries are reconsidering its history and culture. See Tavakoli-Targhi (Citation2001).

References

- Alexander, C. (2002). The nature of order: An essay on the art of building and the nature of the universe (Vol. 4). Berkeley: Center for Environmental Structure.

- Collins, P. (1998). Changing ideals in modern architecture (pp. 1750–12). Montréal: McGill-Queen‘s University Press.

- Dreyfus, H. L., & Rabinow, P. (1988). Michel Foucault: Beyond structuralism and hermeneutics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Elden, S. (2001). Mapping the present; Heidegger, Foucault and the project of a spatial history. London: Continuum.

- Foucault, M. (1991). Discipline and punish: The birth of prison. London: Penguin.

- Foucault, M. (2002a). The archaeology of knowledge. London: Routledge.

- Foucault, M. (2002b). The order of things; An archaeology of the human sciences. London: Routledge.

- Hollier, D. (1989). Against architecture, the writings of georges bataille. (B. Wing, Trans). Boston: MIT Press.

- Khaghani, S. (2012). Islamic architecture in Iran; Poststructural theory and the history of Iranian Mosques. London: I.B.Tauris.

- Kuang-Ming, W. (1997). On Chinese body thinking: A cultural hermeneutic. Leiden: Brill.

- Levine, C. (2015). Forms: Whole, Rhythm, Hierarchy, Network. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press

- McNay, L. (1994). Foucault; A critical introduction. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Shafī’ī Kadkanī, M. R. (1386 [2008]). Sovar-i Khīyāl dar She’r-e Fārsī. Tehran: Āgāh.

- Tavakoli-Targhi, M. (2001). Refashioning Iran: Orientalism, occidentalism, and historiography. Basingstoke: Palgrave.