Abstract

We use theories from the philosophy of sport literature to contextualize and make conclusions in relation to two famous matches in Fiji’s soccer history: the 1982 Inter-District Championship Final between Ba and Nadi and the 1988 World Cup Qualifier between Australia and Fiji. In relation to the first game, Nadi and Ba officials made a gentlemen’s agreement not to accept Fiji Football Association’s decision to host the final replay in the neutral venue of Lautoka instead of the original venue of Nadi and then Ba reneged on that agreement. We conclude that, based on the philosophical treatment of fair play as equal to respect for the game, Fiji FA was within its rights to host the replay in Lautoka and Nadi should have turned up to play on the day. In the second game, we argue that Fiji was the better team on the day, in its 1–0 win over Australia, and so the victory was neither hollow nor undeserved. However, during that era, Australia was the better team overall as it won the majority of games played between the two nations.

Public interest statement

This article focuses on Fiji soccer history, 1980–1989, which is a topic which has drawn very little scholarly attention up until now. People are familiar with a country which has been remarkably successful in 7s rugby and, to a lesser extent, 15s rugby, over the last 30 years. However, what is less known is that Fiji had a strong soccer team during the 1980s. The national team beat New Zealand and Australia and conclusively swamped elite visitors Newcastle United 3–0 in a 1985 friendly. The passion for the game, especially among the 330,000-strong Fiji-Indian community, is very high although conspicuous consumption on merchandise is absent. The article reviews two famous games: the 1982 (domestic) IDC Final between Ba and Nadi and the 1–0 win over Australia in 1988. Interviews with ex-players are a highlight of the work. We hope that the reader is able to experience the unique atmosphere of the remote Fiji islands and the struggle to build a sport.

1. Introduction

We use theories and concepts from the philosophy of sport literature to contextualize and make conclusions in relation to two famous matches in Fiji’s soccer history: the 1982 Inter-District Championship Final between Ba and Nadi and the 1988 World Cup Qualifier between Australia and Fiji. In relation to the first game, Nadi and Ba officials made a gentlemen’s [sic] agreement not to accept Fiji Football Association’s decision to host the final replay in the neutral venue of Lautoka instead of the original venue of Nadi and then Ba reneged on that agreement. We conclude that, based on the philosophical treatment of fair play as respect for the game, Fiji FA was within its rights to host the replay in Lautoka and Nadi should have turned up to play on the day. In the second game, we argue that Fiji was the better team on the day, in its 1–0 win over Australia, and so the victory over Australia was neither ‘hollow’ (Dixon, Citation2007, p. 167) nor “undeserved” (Dixon, Citation2007, p. 167). However, during that era, Australia was the better team overall as it won the vast majority of games played between the two nations. Australian sources’ efforts (for example, Gorman’s (Citation2017) recent book The Death & Life of Australian Soccer) to remove the 1–0 match from the official memory perhaps reflect their worry that, if this was not done, the first argument (better team on the day) might begin to overshadow the second (better team overall).

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: Section 2 provides background information; Section 3 is a Literature review; Section 4 describes research method; Sections 5 and 6 apply theories from the philosophy of sport literature (about “fair play” and a “deserved victory”) to two matches from Fiji Soccer History (1980–1989) and arrive at theoretically informed but still somewhat tentative conclusions. Section 6 speculates about reasons for Fiji Soccer’s relative decline since 1990; while Section 7 concludes the article.

2. Background

2.1. The organization and structure of Fiji soccer and the national-league

It is important to point out here that, as a legacy of British colonial and Australian imperialistic influences, Fiji Soccer is administered on an association basis with the associations representing provinces in most instances and being responsible for the running of the game, at senior and junior levels, within their territorial boundaries. It is a similar model to Australian and New Zealand 15s rugby, English county cricket, and Australian Sheffield Shield (state-versus-state, four-day) cricket. There are over twenty soccer associations in Fiji and, of course, not all these associations have a team in the national-league (first-division); some smaller and remote associations compete in the national-league second-division. Crucially, the national-league teams represent their associations, and so they may be correctly termed association or district teams. They should not be called clubs or club teams. And a Nadi player, for example, may be correctly called a “district representative” or “district rep”. Clubs exist in Fiji at the level immediately below the association or district teams, and there is a National Club Championship, at which clubs from all around Fiji compete (in the final series), but this competition is of minimal interest to supporters.

2.2. The structure of Fiji soccer’s tournaments and the “soccer tourism” phenomenon

One important development which should be mentioned here is the concept of “soccer tourism” whereby Fiji-Indians now living overseas (twice-migrants) time their holidays back to the islandsFootnote1 to coincide with one of the three national-league cup tournaments which are the Fiji FACT tournament, held earliest in the calendar year; the Battle of the Giants (BOG), held around July; and the most important and long-standing Inter-District Championship (IDC), held in October, which dates back to 1938 (Prasad, Citation2013, pp. 17–9). These three tournaments are held over a period of several weeks with group-stage games being played around the country and then semi-finals and the final being played in the host-city over one weekend. These tournaments involve only the eight national-league (first-division) teams and the group stages involve two groups of four. These three tournaments are totally self-contained and the best comparison is the World Cup format. The national-league season stretches for most of the calendar year and so there are four major trophies up for grabs annually. The national-league presently has two divisions and features promotion and relegation after a play-off game(s) between the last-place team of the first-division and the top-place team of the second-division. The IDC is the most prestigious trophy; but the national-league is seen as the sterner test of a team’s ability over an extended number of games.

2.3. Fiji soccer history, 1980–1989

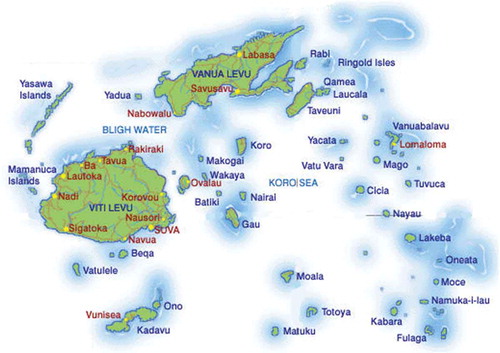

This article studies two matches from a relatively stable and successful time period in Fiji’s soccer history, 1980–1989. Although effectively an amateurFootnote2 game, public enthusiasm for the sport, especially among the Fiji-Indian community (37.5% of the population), was very high and the standard of the game was also very good by historic local and regional standards.Footnote3 The national-league, established in 1977, and the various national knock-out cup competitions, saw arch-rivals from the west of Fiji, Ba and Nadi, compete for and share honours in the first part of the decade. Later, it was the turn of the perennial also-rans Nadroga to achieve success, while Western Fiji powerhouse Lautoka had several good years in the middle of the decade. One reason for the popularity of soccer in this era was that the most successful teams on the field (Ba, Lautoka, and Nadi) were also, by and large, the best supported teams. These three teams gain their support primarily from the Fiji-Indian community of Western Fiji. This region is one of the country’s primary sugar-cane producing regions (in addition to the north coast of the second island, Vanua Levu); and a place where the Fiji-Indian population, the chief soccer-supporting community, once held a numerical majority. In 1970, prior to mass Fiji-Indian emigration, following the two military coupsFootnote4 of 1987, Lautoka City had a Fiji-Indian majority, as Ba Town continues to have in the present day. Nadi (population 42,284) is the most western of these three coastal towns, 35.6 kilometres south-west from Lautoka City (population 52,500) and 60.7 kilometres south-west from Ba Town (population 14,596).Footnote5 Figure depicts the location of these three towns, which can be seen in the upper-left quarter of the main (largest) island Viti Levu.

The Fiji national team was relatively successful in the 1980s too. The legendary German journeyman manager (or “coach” in Australian and American parlance), Rudi Gutendorf, arrived on the national scene in 1983 after a failed stint in Australia; he introduced tactical astuteness and technical refinements to the team as well as boosting the self-confidence of the players due to both his personal style and his track record. The team narrowly lost 1–0 to a strong Tahiti team, under controversial circumstances, in the 1983 South Pacific Games final in Apia, under Gutendorf. Fiji also defeated New Zealand 2–0 in Suva on 16 August 1983 with both goals being scored by Suva striker Tony Kabakoro.Footnote6 Later, with Gutendorf’s influence still present to some degree, Fiji defeated Newcastle United (England) 3–0 in Nadi on 26 May 1985; New Zealand 2–0 in Lautoka on 17 November 1988; New Zealand 1–0 in Ba on 19 November 1988; and Australia 1–0 in Nadi on 26 November 1988.Footnote7

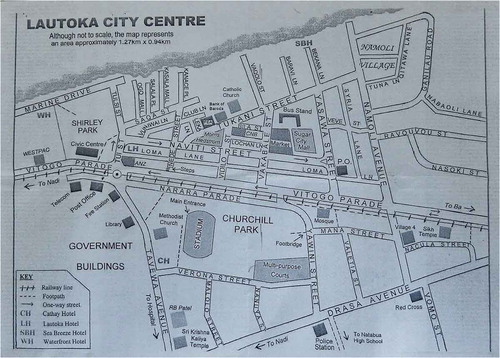

The aggressive central-midfielder, Henry Dyer, famed for his charisma, mixed-race good looks (he is of mixed British and Fijian heritage), and bad-boy rebellious streak, was a key player in this era and he is still highly revered in Fiji soccer circles today. He famously left Nadi to join neighbouring city team and arch-rival, Lautoka Blues, for two seasons in the mid-1980s, and he was an important player in a strong Lautoka team in those years alongside other star performers Sam Lal, Niko Lilo, Wally Mausio, and Sam Work.Footnote8 In the twilight of his career, Dyer returned to Nadi but his second stint in the airport town failed to match the success of his first stint; and Nadi had a much weaker squad by that stage too. Major incidents involving Dyer include: his dropping from the Fiji team to play Australia in 1988 due to his alleged involvement with a motor vehicle which was allegedly involved in a crime in the capital-city of Suva; police arriving at Lautoka’s Churchill Park (which can be seen clearly in the Lautoka City map which is this article’s Figure ) to apprehend him in the minutes prior to a match; and his alleged involvement in later years with a Chinese nightclub owner based in Nadi and a robbery at a Lautoka jewellery store (ironically located just across the road from Churchill Park). The first-mentioned event will be discussed later in this article.

3. Literature review

Butcher and Schneider (Citation2007, p. 120) put forward five different philosophical treatments of fair play, and then go on to add a sixth one which they feel is superior to the other five. The original five perspectives are: (a) fair play as a “bag of virtues”; (b) fair play as play; (c) sport as contest and fair play as fair contest; (d) fair play as respect for rules; and (e) fair play as contract or agreement. Their preferred philosophical treatment is: fair play as respect for the game. Butcher and Schneider (Citation2007) use the fictional Josie-racquet example to illustrate their argument about the superiority of the sixth philosophical treatment, fair play as respect for the game. Josie arrives at the sports venue without her squash racquet and needs a new one; you are her chief competitor and only you have a suitable spare one you can offer her for the tournament. These authors argue, and we agree with this argument, that only under their sixth perspective is it unambiguous that you should lend Josie your spare racquet so that she can compete.

The philosopher of sport Dixon (Citation2007, p. 171) argues that there is an “uncontroversial view that the primary purpose of competitive sport is to determine which team or player has superior athletic skill (understood as including both physical ability and astute strategy as permitted by the game’s rules)”. Dixon (Citation2007, pp. 176–7) prefers championship trophies to be awarded not to play-off winners but to teams finishing at the top of their leagues, as at the end of each season, as in European and South American soccer. According to Dixon (Citation2007, p. 177), “the most accurate measure of athletic excellence is performance against all rival teams over an entire season.” Dixon lists the following reasons why the objectively best team might not win on the day: refereeing errors, cheating, gamesmanship, bad luck, and inferior performances by superior athletes. Dixon (Citation2007) explains the situation further through an effective fictional example. Imagine that, in Steffi Graf’s heyday (late-1980s to mid-1990s), an unseeded tennis player defeats all comers, through narrow and gutsy wins, and then defeats Graf in the same way. Dixon (Citation2007, p. 174) concludes as follows: “She deserves her victory because, on that day, she is the better player. However, in another sense, she is not the better player. Steffi Graf, who would almost certainly beat the player nine times out of ten, is the better player.”

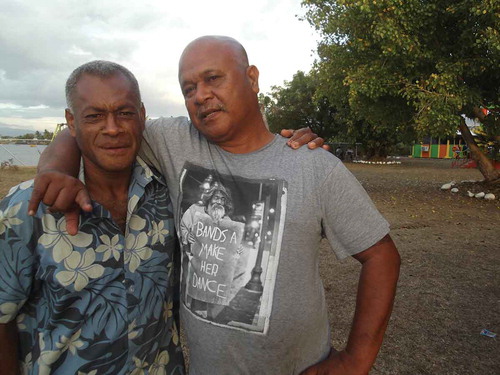

Lautoka Blues dominated the Fiji national competitions during its (Lautoka’s) glory years, 1938–1959.Footnote9 Since then it has only recaptured its brilliance in short spurts such as the 1984–1985 team whose further progress was halted by the uncertain political environment of the coup year 1987 and by Ba’s resurgence. Figure depicts Dyer (left) with the ex-Lautoka Blues champion, Wally Mausio, at the Lautoka Club sometime during 2014.

In one of the very few academic articles on Fiji soccer, James (Citation2015, p. 21) puts forward the argument that Lautoka Blues’ on-field decline since 1970 has “mirrored” the increasing anxieties in the Sugar City caused by the synchronous decline in the sugar industry and the beginnings of mass Fiji-Indian emigration (without any one of these three factors necessarily causing either or both of the other two in mechanistic fashion.) The analysis here draws heavily on the work of music scholar Lucy O’Brien (Citation2012) who argued that the feminist sounds of Leeds’ student bands Gang of Four and Delta 5 in the early-1980s mirrored the depression and anxiety which were the result of the Yorkshire Ripper’s reign of terror in the area. The Ripper’s thirteenth victim, Jacqueline Hill, had been a student in the English Department (O’Brien, Citation2012, p. 34).

4. Research method and research question

The first-mentioned author, an Anglo-Australian of Irish-Scots descent, moved to Fiji in 2013 to begin an academic appointment. During his first year in Fiji he became a supporter of Lautoka Blues and a regular attender at home games at Lautoka’s Churchill Park. One afternoon, during the first half of calendar year 2014, by chance, he began a conversation with the ex-Nadi, Lautoka, and Fiji soccer player, Henry Dyer, a part-EuropeanFootnote10 of mixed indigenous Fijian and white British heritage, in the now closed Deep Sea Pub in Queen’s Road, Nadi Town. (The nightclub of the same name directly across the street is still open and will give any interested reader who visits Fiji a good sense of the look and vibe of the original pub.) After discussion, it was agreed that this author would co-operate with Dyer to write the latter’s memoir. The pair spent most Thursday afternoons during 2014 and 2015 working on the book before this author left Fiji in December 2015. This article is one by-product of this author’s two-year collaboration with Dyer and draws heavily upon the many interviews and conversations between the pair during 2014 and 2015; as well as interviews involving nine other individuals; and three days’ archival research at the Fiji Times head office in Suva looking up old match reports. Participant-observation included the first-mentioned author attending a Fiji Football Association Veterans’ Dinner held in Nadi on 4 October 2014. Table lists this study’s interviewees and the key matches in which they played.

Table 1. List of interviewees and the matches in which they played

It was decided that interviews with more Fiji soccer personalities were needed both for the sake of the memoir and for the sake of any academic articles which might emerge from the larger research project. First both Dyer and the author interviewed Mr Bobby Tikaram, president of the now defunct Airport Soccer Club in the Nadi club competition and vice-president of Nadi Soccer Association in the early-1980s. Tikaram spotted Dyer playing touch rugby at the Airport grounds in 1981 and recruited him to play for both Airport SC and Nadi. The author also interviewed the ex-Nadi team doctor, Dr Raymond Fong, at his surgery in Nadi Town, during 2014, after the meeting had been arranged by Dyer.

After these initial interviews and informal conversations, four key matches from the 1980–1989 era were identified: (a) the 1982 IDC Final between Ba and Nadi; (b) the 1983 South Pacific Games Final in Apia, Samoa between Fiji and Tahiti; (c) Fiji’s 1985 3–0 victory over England’s Newcastle United held in Nadi; and (d) Fiji’s 1–0 win over Australia in a 1988 World Cup Qualifier also held in Nadi. The 1980–1989 era was chosen because Dyer and his contacts played during that time period and also because it was a time of relative success for the sport in Fiji and also for the Fiji national team. It was decided to focus on the first and last of these four games as the issues involved lent themselves best to an analysis involving application of theories from the philosophy of sport literature.

It was decided to interview as many as possible ex-Ba and Nadi players who played in that 1982 IDC Final. Some had passed away (including Ba’s Joe Tubuna and Jone Nakosia) whilst others had emigrated (including Ba’s then goalkeeper Bale Raniga) so the total available players was somewhat lower than originally thought. In the end we interviewed four ex-Ba players (Meli Vuilabasa, Inia Bola, Semi Tabaiwalu, and Julie Sami) and two ex-Nadi players (Dyer and Nadi’s then goalkeeper, Savenaca Waqa). It was also decided to interview at least one player of Fiji-Indian ethnic heritage due to the racial factors which surround, direct, challenge, and blight the game up until the present era. We (Dyer and the author) managed to jointly interview the ex-Ba and Fiji player, Julie Sami, who is Fiji-Indian.Footnote11

Overall, the research process involved interviews with five ex-Ba players (including one Fiji-Indian to attempt to get a variety of ethnic perspectives); two ex-Nadi players (including Dyer); one ex-Nadi vice-president; one ex-Ba president; one ex-Nadi team doctor; and the Fiji General Workers’ Union (FGWU) president who is also a long-time Ba Soccer supporter. Dates of the interviews are also reported in Table .

This article is our attempt to satisfactorily answer the following research question:

RESEARCH QUESTION: What conclusions and insights can be drawn from application of theories from the philosophy of sport literature to two classic games in Fiji Soccer History, the 1982 IDC final and the 1988 Australia versus Fiji game?

5. Results

5.1. Match one: 1982 IDC final, Nadi versus Ba at Prince Charles Park, Nadi

One particularly remarkable game, the first of the matches covered in this article, saw the two best teams of the first half of the decade, Ba and Nadi, play out a drawn 1982 IDC (knock-out cup) Final at Prince Charles Park, Nadi. Figure depicts Prince Charles Park in 2014, which is pretty much exactly how it would have looked in 1982 although the floodlights had not yet then been constructed.

This game led to a penalty shootout to break the 0–0 (a.e.t) stalemateFootnote12 but the shootout had to be abandoned after 10 kicks each since the scores were still tied at 6–6 (see Table ); and conditions were deemed too dark for play to continue. The penalty scores were tied 3–3 after the first five kicks each; and, for the next five kicks from both sides, both sides’ kickers either scored together or missed together (see Table ).

Table 2. Penalty shootout results, 1982 IDC final. (Source: Fiji Times; various interviews)

In what was later seen as evidence of Ba’s innate trickiness and ruthlessness, Ba protested against the light, after 10 kicks each, and the protest was upheld. Ba officials and players, Dyer said later, did not realize that Nadi’s goalkeeper, Savenaca Waqa, the only remaining Nadi player not to have taken a penalty-kick, had suffered an ankle injury. As Dyer says: “When it came to Save’s turn little did we know that Ba was about to protest about the floodlights. They did not know that Save could not kick. He could [also] not stand in goal to take any more pain to defend” (source: author and Dyer’s interview with Nadi’s 1982 vice-president, Bobby Tikaram, 14 August 2014). One interesting curiosity from Table is that the strikers from both sides missed their goals (Bacardi and Rusiate Waqa for Nadi and Vuilabasa and Bola for Ba) but the midfielders, for the most part, succeeded. Less surprisingly, the defenders from both sides missed their goals as the pressure mounted (Tora and Qoro for Nadi and goalkeeper Raniga and Soro for Ba).

A replay match was scheduled by Fiji Football Association (FFA) at Lautoka’s Churchill Park, on the basis that it was a neutral ground located approximately halfway between Nadi Town and Ba Town (and hence easily accessible for both sets of supporters).Footnote13 Nadi refused to play the game at a neutral venue because Nadi was where the original tournament was held.Footnote14 In response to this ruling by FFA, Ba Soccer officials agreed with Nadi Soccer officials not to turn up at Lautoka. It was a verbal or gentlemen’s agreement between the then presidents, the late Sri. V. Chetty of Nadi and Vinod Patel of Ba (as confirmed by Bobby Tikaram, then Nadi vice-president, in conversation with Dyer and the author, 12 June 2014). This agreement was confirmed, back in 1982, by Sashi Mahendra Singh, the then father of Ba and Fiji soccer (as recalled by Bobby Tikaram, in conversation with Dyer and the author, 14 August 2014). Dyer describes what happened next:

At the eleventh hour, Ba turned up at the [replay] match and walked on to the field. We [Nadi players] were there expecting the game not to happen. We were surprised to see Ba walk on to the field. We were there in our normal street-clothes walking around the park. We were shocked at what happened. Ba broke their verbal agreement. That was a matter for the officials. We players are still close until today (personal interview with author).

Because only Ba players walked on to the field at Churchill Park for the replay, the trophy was awarded to the Ba side. Ba had broken its original gentlemen’s agreement with Nadi not to play the replay match outside of Nadi. The manner in which Ba “won” this game created lasting bitterness towards Ba from Nadi players, supporters, and officials which festered for many years and arguably still exists today. It is one of the very few senior football matches played which has never had a proper ending. The game added fuel to the fire to make the Ba-Nadi rivalry the most important and passionate match-up in Fiji soccer eclipsing other intense rivalries such as Nadi-Lautoka, Ba-Lautoka, Rewa-Suva, and Ba-Rewa.

Do you remember how Henry Dyer performed in the final in Nadi?

Henry Dyer played the game of his life and was at his peak. While in defence he clashed with Joe Tubuna and injured his head. However, he refused to give up and played on as if nothing had happened. Tubuna had to be taken to Nadi Hospital for stitches. You have to give full credit to both teams. They wanted the best and gave their best. After the treatment at Nadi Hospital he [Joe Tubuna] returned to the ground desperate to play but was advised by Ba officials that he had already been replaced by another player.

Returning to discussion of the 1982 IDC Final, the game contributed to sustaining and increasing spectator interest in Fiji soccer for a number of years. The game remains legendary today and the rivalry between Ba and Nadi remains as strong as ever. The ruthlessness of Ba’s administration in turning up for the replay, which they knew would transgress the terms of the gentlemen’s agreement, fed into Ba’s image as a formidable and even cruel professional unit, similar in essence to sport’s other more famous Men in Black, the New Zealand All Blacks. In interviews with players from the game, conducted in 2015, Ba players denied knowledge of the gentlemen’s agreement between the two presidents not to play the replay outside of Nadi but made it very clear that they were commanded to turn up for the replay by the Ba administrators; some expressed quiet regret about the way that events unfolded. The players on each side, united in most cases by close bonds in the indigenous Fijian community of Western Fiji and by shared membership in the Fiji national team, hold no bitterness towards each other and express an understanding that events were taken out of their hands. Interestingly, both Dyer and S. Waqa of Nadi said that, with the benefit of hindsight, Nadi should have swallowed its hurt pride and turned up for the replay so as to give the fans of both sides a proper conclusion to the match.

Players who played in that game commented as follows from the relative safety and vantage-point of June-August 2015:

Now I’m able to say I think we should have played the final to sort it out and to provide a proper conclusion for the fans (Henry Dyer, interview of Savenaca Waqa by Dyer and the author, 27 August 2015; Savenaca Waqa expressed agreement with Dyer’s comment).

I missed that penalty-kick in the shootout! Playing on their home ground Nadi were a hard team to beat. They could not win that game and they did not want to lose either. They did their best to hold us to a 0-0 draw. Then the penalty shootout was anyone’s game. Everyone missed except one or two people, man! We were ordered to replay on a neutral ground but Nadi did not turn up so it was awarded to us. We marched into the ground but then we heard that Nadi was not coming (Meli Vuilabasa, ex-Ba player, interview, 2 June 2015, the emphasis is the authors’).

What do you remember about the 1982 IDC Final against Nadi which featured the penalty shootout?

Myself I thought I can’t miss the penalty-kick. I just don’t know how I missed it. After kicking the missed shot the ball hit the side of the post. When I got home I wanted to chop my soccer boots off [laughs].

Was Ba correct to turn up for the replay in your opinion?

It was the officials who required us to get to the ground and walk on to the field. There was the threat of a fine hanging over our heads.

Did you know that the Nadi players were upset about what happened?

We knew very well that the Nadi players and officials were very upset! (Inia Bola, ex-Ba player, interview, 17 June 2015).

As mentioned earlier, Butcher and Schneider (Citation2007, p. 120) argued that the best and most complete philosophical perspective governing fair play in sport is fair play as respect for the game as opposed to any one or more of the following: (a) fair play as a “bag of virtues”; (b) fair play as play; (c) sport as contest and fair play as fair contest; (d) fair play as respect for rules; and (e) fair play as contract or agreement. How can we evaluate Fiji FA, Ba officials, and Nadi officials according to these various perspectives? The FFA acted within its rights, as controller of the game, to schedule the replay in Lautoka and it was a reasonable decision given the accessibility of Lautoka to both sets of fans. The perspective (e), fair play as contract or agreement, would intuitively appear to be the most relevant perspective to analyse the Ba officials’ actions as they broke their gentleman’s agreement with Nadi officials not to play the replay match if it was to be held outside of Nadi. However, both associations also had an agreement to adhere to FFA’s rules and directives, which Ba did while Nadi did not. Which of these obligations should be regarded as the most morally significant? If we introduce the preferred principle, respect for the game, it provides added insight. If we regard “the game must go on to reach a proper conclusion and outcome” as the most important principle, a subset of respect for the game, then the ex-Nadi players Dyer and S. Waqa are right to say that Nadi should have turned up for the replay and played the game regardless of the venue. Lautoka is only 36 kilometres from Nadi and a Sunday afternoon 3.00 p.m. kick-off would have provided Nadi fans ample opportunity to attend. In fact, Nadi was fortunate that FFA decided not to hold the replay at Ba’s feared Govind Park ground. Perhaps a lower than normal admission price for those who had attended the original game would have shown the fans that FFA had their best interests at heart.

A match in the Scottish Premier League in 2018/19 between Kilmarnock and Motherwell was abandoned due to fog within two minutes of the second-half starting (officially in the 47th minute). The score was 0–0 and hence to replay the entire match on the next Saturday (three days later) was relatively uncontroversial. Players waited for 12 minutes to see whether the fog would clear and, when it did not, the game was abandoned. There was some uncertainty and confusion about ticket pricing for the replay match, which was almost comic, as both Kilmarnock and Motherwell managements struggled to respond appropriately to the new and unusual circumstances. First the Kilmarnock management advised that a voucher would be given to home fans so that admission to the second game would be free. This was then reversed (it was stated that the vouchers did not guarantee free entry); £5 was charged; and Motherwell agreed to pay the £5 charge imposed upon its travelling fans. A huge crowd (by Kilmarnock and Motherwell standards) of 6,205 people suggests that low crowds in Scottish professional soccer (outside of Celtic versus Rangers games) may, in large part, be due to exorbitant ticket prices.

Players from Ba and Nadi made up the bulk of the Fiji national squad in the early-1980s; and debate continues today among older supporters as to whether Ba’s or Nadi’s team was the better one. Nadi’s three national-league titles (1980–1982) must be put up against Ba’s legendary six IDC wins in a row from 1975–1980 (and 1982); the difference in numbers of titles and formats of the game making this comparison extremely subjective. On the Ba side, we get of course more Ba supporters extolling the greatness of the team which brought considerable honour to the small Fiji-Indian dominated manufacturing town; whereas many Nadi fans might prefer to regard Nadi’s achievement as being the finest because form in the national-league must be sustained over a greater number of matches (Dixon, Citation2007, pp. 176–7). As mentioned earlier, Dixon (Citation2007, pp. 176–7) prefers championship trophies to be awarded not to play-off winners but to teams finishing at the top of their leagues as at the end of each season, as in European and South American soccer. Nadi fans might also point to their team’s success at “international level” when Nadi defeated New Caledonia 2–0 at Prince Charles Park in 1983 (source: Dyer, interview with author, 14 May 2014).

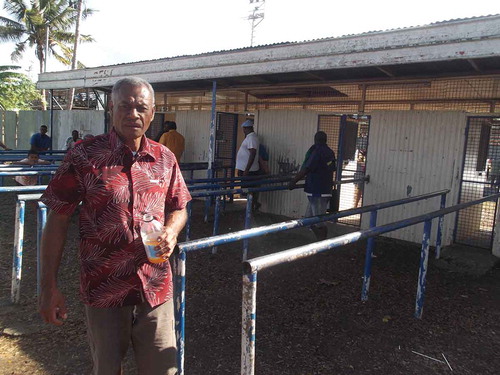

One can still meet Ba’s president of the 1982 era, Vinod Patel, at his back-office on the ground floor of the Ba branch of his Vinod Patel hardware chain. When the author visited with Dyer on a quiet weekday morning, his university academic credentials got him past Mr Patel’s personal assistant/gatekeeper, but it was Dyer who was of much more interest to the man himself as they reminisced about past matches at both national-league and national-team level, including the unsuccessful 1985 national-team tour of New Zealand. Afterwards, Dyer said that Patel had smiled in gleeful fashion when the 1982 IDC Final was recounted; the now 80-year-old businessman (born 28 February 1939) still fondly remembers how Nadi was outsmarted by his tricky manoeuvrings from outside the field of play all those years ago. Figure depicts Dyer on Ba’s main street, only a few hundred metres from Mr Patel’s office, on a quiet weekday morning; while Figure shows Dyer outside Ba’s Govind Park ground.

5.2. Match two: Fiji 1, Australia 0, 26 November 1988

Another legendary match for Fiji fans is the shock 1–0 1988 win over Australia at Prince Charles Park, Nadi, which was the first leg of a two-leg qualifying round for the 1990 World Cup. The game ended among jubilant scenes with Fiji manager Billy Singh being chaired off the field and Australian manager, the Yugoslav Frank Arok, and players left seething in disappointment, anger, and disbelief (Singh, Citation1988, p. 32). A November 2014 article in The Guardian Sport Online entitled “The Forgotten Story of … the Socceroos” defeat to Fiji’ mocks and patronizes Fiji, as a country; Nadi, as an aspirational but confused tourist town; Nadi’s Prince Charles Park, as a stadium; and of course the 1988 Fiji national team (Guardian Sport Online, Citation2014). But the anonymous author of this article fails to give due recognition to the fact that this was a relatively strong Fiji team and indeed arguably the strongest national team in the nation’s history up until the present-day. However, there had been some poor results in the intervening two years, since the 1985 victory over Newcastle United, which can, in part, be attributed to Gutendorf’s departure.

By 1988, new young players were beginning to replace the old guard of the early-1980s. Goalkeeper S. Waqa had retired in 1987 (or had “work commitments and was unable to be released” as Meli Vuilabasa says); Joe Tubuna from Ba died in a motor-vehicle accident on 4 August 1984; and other Ba players Bola, Julie Sami, and Semi Tabaiwalu had either retired or fallen out of favour. (Bola and Tabaiwalu were involved in the same motor vehicle accident which killed Tubuna.) Dyer was to be captain but was dropped for disciplinary reasons. A host of rising young stars, including Pita Dau, Lote Delai, and Ravuama Madigi, had been brought into the team since 1985; they had had a few years of national-league and national youth-team experience by this stage, and anticipation was high. Madigi (pronounced “Man-diggy”), in particular, was very well-connected, in both indigenous Fijian and Ba Soccer terms, being Bola’s younger brother and a member of Ba Under-21s’ 1980 IDC championship winning team. A partial changing of the guard was evident.

Although a local Fiji-Indian, and not a foreigner, Billy Singh was also highly regarded, being the son of legendary Ba manager Sashi Mahendra (S.M.) SinghFootnote15 (“the Father of Ba Soccer”) (1920–1990), and someone who had been nurtured and groomed within the professional and self-confident atmosphere at Ba Soccer. Billy’s father had been a guest at the 1974 World Cup finals in West Germany and had brought extra self-confidence and tactical knowledge back to Fiji upon his return, setting Ba up for its six in a row IDC wins from 1975–1980. The ex-Ba and Fiji player, Julie Sami, remarked in 2015 (source: interview with the author and Dyer, 1 October 2015) how he had visited S.M. Singh’s home back in the day and been amazed to find that his (Singh’s) VHS video-tape collection was made up nearly exclusively of soccer videos rather than Bollywood movies. Billy Singh was not much of a drop in class compared to even Gutendorf. In Dyer’s words: “At the time of Fiji’s 1–0 win over Australia in 1988 there was still some Rudi [Gutendorf] influence as Billy Singh had been under him” (source: interview with author, 25 March 2015).

Central midfielder Dyer (by this stage of his career he was being used as a defender at right-back) was left out of the Fiji team (he had been chosen as captain) at the last minute due to his alleged connection to a rented motor vehicle which had allegedly been involved in a robbery in Suva. The South Melbourne and Perth Glory (Australian soccer) midfielder Con Boutsianis was involved in a similar situation in 1998. Kreider (Citation2012, p. 281) writes as follows: “Boutsianis was placed on two year’s [sic] probation after allegations of being a getaway driver in a Melbourne restaurant robbery in 1998.” Although disappointed at the time, Dyer says that he took the decision to drop him with good grace and lent his support to the new young replacement captain, Pita Dau, from Lautoka Blues. Dyer revelled in and enjoyed the surprise victory from the other side of the perimeter fence.

Dyer explains the complex situation further as follows (the last two sentences of the second quote are perhaps the most revealing):

On the eve of the Australian game, the [FFA] President, Dr Sahu Khan, came up to me and said: ‘Are you ready to lead the team?’ You could tell from his countenance that he was coming to convey good news. I was happy to be told I would captain the team so I took the news quietly and with dignity and pride as this was to be the biggest game of my life. It was great that I could hear the message directly from the president and not from one of the other members of the management team. I kept this quiet in my heart until, not long after this, President Sahu Khan comes back to me shaking his head in disbelief that I was to be dropped from the team and that he was to tell me the news. He did not ask me any questions as he had known or been told from the management as to why I had been dropped.

This [dropping from the team] was because our Lautoka team manager, Shah Anwaz Khan, (as I was playing for Lautoka then), was working for a solicitor. The solicitor asked him (the manager) to locate a vehicle which he had hired out for rental to a [indigenous] Fijian guy who was now living in Suva. The rental car was in Suva too while we were preparing for the Australia match. I had a lot of friends on the streets in all walks of life. They helped me to locate the vehicle in a very short time. The manager asked me to fetch the car back for him as he knew that I would be able to complete the task. He was a very good friend of mine and I played for his club (Leeds United in Lautoka). The name of the lawyer was Haroon Shah. What I did wrong was I was driving the vehicle around in Suva and did not let the lawyer or the manager know that I had located it. I kept it for about one week (Henry Dyer, interviews with author, 8 May 2015 May, 26 September 2014).

Fiji scored, on the back of a vocal home support, and in stifling heat and humidity, through a Lote Delai pass in the 67th minute (Guardian Sport Online, Citation2014; Gabriel; Singh, Citation1988) to Ba teammate Ravuama Madigi. The 23-year-old Fiji Sugar Corporation mill-labourer Madigi had come on as a 29th minute substitute for Jone Watisoni (Gabriel Singh, Citation1988). Left-back Delai was running down the left-flank outer-wing before he sent in a knee-high cross towards the box at the hospital end of the ground (Guardian Sport Online, Citation2014; Prasad, Citation2008, p. 48 and Appendix VII, p. 94; Gabriel; Singh, Citation1988; Thompson, Citation2006, p. 201). Ba’s Vimal SamiFootnote16 (brother of Julie Sami) dummied and Madigi scored with a single touch left-volley which eluded the Socceroos’ goalkeeper Jeff Olver (see Table ) (Guardian Sport Online, Citation2014; Gabriel; Singh, Citation1988; Thompson, Citation2006, p. 201). All three of the Fiji players involved here were also teammates for Ba in domestic soccer which explains the title of Gabriel Singh’s Fiji Times match report: “Ba magic lifts Fiji to victory.” Billy Singh’s strategy (the actual manoeuvre which led to the goal had been practised many times at training) was to observe the Socceroos’ defensive structure and lull them into a false sense of security by having them first commit themselves to monitoring the physically bigger Jone Watisoni. At the 29th minute, the smaller and more skilful Madigi was brought on, whilst Watisoni was taken off, thus leaving the Socceroos’ defensive structure in a confused state. Journalist Singh named goalkeeper Nasoni Buli and defender Maretino Nemani as his best Fiji players of the day (Gabriel Singh, Citation1988). Australia was not able to equalize (see Table ). Lote Delai also scored an excellent late consolation goal in the 5–1 return match loss (which was played in Newcastle, Australia on Saturday, 3 December 1988) (Thompson, Citation2006, p. 201).

Table 3. Fiji versus Australia, Prince Charles Park, Nadi, 26 November 1988 (WCQ)

This first-match goal in itself greatly enhanced Madigi’s legendary status in Fiji. As Singh (Citation1988, p. 32) wrote in the Fiji Times match report of 28 November 1988: “[A]ll it took was 30 seconds of Ba magic to turn soccer’s ‘bad boy’ Ravuama Madigi into a national hero.” In 2000, the Ba legend was appointed player-manager of Rewa, a well-supported team based in the Suva satellite town of Nausori (Motherwell to Suva’s Glasgow or Campbelltown to Suva’s Sydney) (Prasad, Citation2013, p. 166). Madigi won Rewa’s first IDC tournament in a generation in 2001Footnote17 (beating his old team Ba 1–0 in the final) (Prasad, Citation2013, pp. 173–4) and his legendary status was then confirmed in the south-east part of the main island as well.

Dyer and Vuilabasa comment about the Fiji versus Australia (1988) match as follows:

Madigi’s goal was a left-footer from the side of his foot that sailed through the defence and left the goalkeeper standing in the middle of the goal; he could not believe that the speed of the shot had been so fast. It was like Sam Work’s kick from the left-flank of Churchill Park [Lautoka], on the wooden-stand side heading towards the hospital end, for Fiji against a Russian team Minsk Dinamo. These were the two kicks I will never forget. They travelled with such speed that they left the goalkeepers stunned (Henry Dyer, interview with author, 8 May 2015 May, 26 September 2014).

We beat Australia. We were very happy but we were very surprised. They were a good team, no doubt about it. I myself was surprised that we beat them. They were a better team than Fiji. When we went to Australia they thrashed us 5–0 [actually 5–1] (Meli Vuilabasa, ex-Ba and Fiji player, interview with Dyer and the author, 2 June 2015).

Fiji’s win over Australia went against the conventional wisdom in both countries that there was a big gap in talent and skill between the two national teams. Australia was objectively the better side, and would win the vast majority of contests between the two nations (as stated by the ex-Nadi vice-president, Bobby Tikaram, to the author). Dixon (Citation2007) lists the following reasons why the objectively best team might not win on the day: refereeing errors, cheating, gamesmanship, bad luck, and inferior performances by superior athletes. Only the last one of these factors and perhaps the second last one applies to this game. Imagine that, in Steffi Graf’s heyday, says Dixon, an unseeded tennis player defeats all comers, through narrow and gutsy wins, and then defeats Graf in the same way. Dixon (Citation2007, p. 174) concludes as follows: “She deserves her victory because, on that day, she is the better player. However, in another sense, she is not the better player. Steffi Graf, who would almost certainly beat the player nine times out of ten, is the better player.” Similarly, the Fiji team of 1983–1988 (the years of Dyer’s international career) might beat the Australian team one match out of ten and New Zealand perhaps twice or three times out of ten. During Dyer’s career (1983–1988), New Zealand won 7 games, Fiji won 3 games, and there were 2 draws; but at home Fiji won 3 to New Zealand’s 4 with 2 drawn. The 1988 team was probably the best Fiji team of the 1980s if its results against both New Zealand and Australia are regarded as the most crucial tests of ability. The Fiji team was the better team on the day of its 1–0 win over Australia in 1988 (there is no mention in the press of the time of any refereeing controversies or cheating) and so we did not have a (as the common sporting phrase goes) “hollow victory” (Dixon, Citation2007, p. 167) or “undeserved victory” (Dixon, Citation2007, p. 167). As Dixon (Citation2007, p. 179, emphasis original) makes clear, “the team that plays better on the day against superior opponents deserves to win [that particular encounter].” This observation by Dixon (Citation2007) does not contradict or negate his previously cited opinion that championship winners should be decided by the first-past-the-post method used in European and South American soccer.

There was a very interesting case in the Perth-based Western Australian Football League (WAFL) (Australian Rules football) competition in 1961. Swan Districts was due to play the best team of the era, East Perth, in the 1961 grand-final; East Perth had a brilliant ruckman, Graham Farmer aka “Polly” Farmer, of aboriginal ethnic background, who was generally regarded as being virtually unstoppable or unplayable. The Swan Districts coach (manager in British terminology), Haydn Bunton Junior, executed innovative “spoiler” tactics to nullify the influence of Farmer in the grand-final; because of these tactics Swan Districts won the game although East Perth was the best team of the year and of the era. Interestingly, Bunton said after the fact that he knew that his team only had the capacity to beat East Perth once because, after that, the tactic would become known and would be countered. The tactic was very wisely saved up until the one game when the stakes were highest.

To conclude, Fiji’s 1–0 win over Australia in 1988 remains an integral part of Fiji soccer history and collective memory, rivalled only by the 3–0 friendly match win over Newcastle United three years earlier. These victories are true achievements because, in both cases, the opponent was worthy (to cite the esteemed philosopher of sport Delattre (Citation2007, p. 200)). Both games are probably comparable, as far as the extent to which the results were a shock to informed commentators, to the Western Australian state team’s 2–1 win over Glasgow Rangers in 1975 and the same state team’s 3–2 win over Werder Bremen (the reigning European Cup Winners’ Cup-holders) in 1992.Footnote18 The 1988 win showed the ability of the Fiji team to absorb the loss of some key players and rejuvenate itself successfully with the injection of fresh young local talent of mostly indigenous Fijian ethnic heritage.

6. Reasons for Fiji’s soccer decline after 1990

Reasons for Fiji’s (relative) soccer success in the 1980–1989 period include:

a strong national-league, headed by the Western Fiji teams Ba, Nadi, and Lautoka, which hail from three towns all located along a 60 kilometre stretch of coastline;

the technical football legacy of German manager Rudi Gutendorf which had a knock-on effect and was still reaping dividends as late as 1988 (according to ex-players);

the fact that Ba, Lautoka, and Nadi’s indigenous Fijian stars were mostly from the same area of Western Fiji and their village, communal, cultural, and ancestral ties added to the cohesion and commitment of the national team (which featured a clear majority of indigenous Fijian players from Western Fiji-based district teams); and

the national team’s rejuvenation in 1988 which saw promising youngsters Pita Dau, Lote Delai, and Ravuama Madigi being injected into the team for the first Australian game to complement what remained of the old guard from the early-1980s. Champions who had disappeared from the national team scene by 1988, for a diverse set of reasons, include Inia Bola (injured/retired); Julie Sami (overlooked but his younger brother Vimal was in the team); Semi Tabaiwalu (overlooked); Joe Tubuna (deceased); and Savenaca Waqa (retired).

The sport had not yet been beset by increased Fiji-Indian emigration, which picked up pace after 1987 and saw the game lose many current and future players, supporters, referees, managers, and administrators; and Fiji’s success in the World 7s rugby circuit was also still in the future. The famous Fiji three-in-a-row title wins at the Hong Kong 7s (precursor to the World 7s circuit) occurred in 1990–1992; right after the last year of the golden era for soccer examined in this article. This team included some beloved indigenous Fijian talents, such as Ratu Kitione Vesikula (coach); Noa Nadruku Tabulutu; Waisale Serevi; and Mesake Rasari, the soldier. As a result, it was able to win the hearts and capture the imaginations of the sporting public, including Fiji-Indians. Rugby-league too, under the strategic direction and patronage of Australia’s National Rugby League (NRL) since 1992, was very smart in not tying itself to the old association model. Instead, it put club teams straight into indigenous villages (e.g. Namoli West Tigers, a reference to Namoli Village, Lautoka City, which can be seen in the top right-hand corner of Figure ) and urban spillover areas (e.g. Saru Dragons).

Talented young indigenous Fijian sportspersons increasingly looked to rugby and rugby-league rather than soccer by the mid-1990s as financial rewards seemed more lucrative; opportunities were greater; and career pathways were clearer in those sports. Another problem is that the identity of an indigenous Fijian is typically bound up with her/his village; after the demise of Sweats Soccer Club, there are now (as at 6 December 2015 when field-work for this study concluded) no village-based club teams playing in the Nadi club competition first-division. Fiji-Indians are content to set up and play for clubs based around a township or some other category (such as high-school or religious classification) as they have a different way of constructing and maintaining identity. However, this reveals another area where Fiji Soccer’s management choices tend to alienate indigenous Fijians.

7. Conclusion

We use theories and concepts from the philosophy of sport literature to contextualize and make conclusions in relation to two famous matches in Fiji’s soccer history: the 1982 Inter-District Championship Final between Ba and Nadi and the 1988 World Cup Qualifier between Australia and Fiji. In relation to the first game, Nadi and Ba officials made a gentlemen’s agreement not to accept Fiji Football Association’s decision to host the final replay in the neutral venue of Lautoka instead of the original venue of Nadi and then Ba reneged on that agreement. We conclude that, based on the philosophical treatment of fair play as respect for the game, Fiji FA was well within its rights to host the replay in Lautoka and Nadi should have turned up to play on the day. Nadi players of the era, Dyer and S. Waqa, concur with this observation. In fact, Fiji FA could have chosen to hold the replay at Ba’s feared Govind Park ground; and we can only imagine how hostile Nadi management’s reaction would have been had this been the decision of the regulatory body. Nadi’s (rigid) mentality was to look at the final as the last game of the 1982 IDC tournament; as such, they argued that the replay should also be held in Nadi as a matter of course. By contrast, Fiji FA tended to view the final as a self-contained match in itself and, as such, choosing an alternative venue for the replay was not unfair nor was it unreasonable especially given that Lautoka is within easy driving distance of both Nadi and Ba if the kick-off is set down for 3.00 p.m. on a Sunday. It seems that Nadi management’s mental rigidity might have reflected its desperate desire to win the series since it had only won three IDC trophies to that point in its history and its last success had been as far back as 1974. Of course, Ba’s management can also be perceived as desperate since it regarded winning the series as more valuable than maintaining a cordial relationship with Nadi’s powerbrokers.

In the second game, we argue that Fiji was the better team on the day, in its 1–0 win over Australia, and so the victory over Australia was neither hollow nor undeserved. However, during that era, Australia was the better team overall as it won the majority of games played between the two nations. The 1988 Fiji team was almost certainly the best Fiji national team of the 1983–1988 era, the era of Dyer’s international playing career. Australian sources’ efforts to remove the 1–0 1988 match from the official memory perhaps reflect their worry that, if this was not done, the first argument (better team on the day) might begin to overshadow the second (better team overall) in the minds of the fans.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kieran James

Dr Kieran James is a Senior Lecturer in Accounting at University of the West of Scotland, Paisley, Renfrewshire, Scotland. During the period 2013–2015 he was Accounting Professor at University of Fiji, located on the Queen’s Highway between Nadi Town and Lautoka City. This research project began when he met the ex-Nadi and Fiji soccer legend, Henry Dyer, in the now closed Deep Sea Pub in Nadi Town in the first half of calendar year 2014. The broader research project into Fiji soccer history, launched in co-operation with Dyer, involved the writing of Dyer’s memoir and the writing of a handful of academic articles of which this is one. The project also saw Dyer and the author launch the Nadi Legends Club website. Mr Yogesh Nadan is a Lecturer at Fiji National University and a PhD student at University of Fiji. He is an avid fan of Ba’s soccer team in Fiji’s national-league and he lives in Ba Town.

Notes

1. Fiji-Indian emigres living in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States’ continued interest in and affection for Fiji soccer (as also evidenced by teams and associations forming in those countries using the names of Fiji teams) might surprise people. However, it achieves a similar purpose which popular music can achieve (according to George Lipsitz), i.e. it “plays an important role in building solidarity within and across immigrant communities” (Lipsitz, Citation1994, p. 126) in the face of “racial exclusion and intolerance” (Bennett, Citation2005, p. 336).

2. Although essentially an amateur game in the 1980s, Fiji soccer historian Mohit Prasad claims that the game could be called “semi-professional” by 1999 (Prasad, Citation2013, pp. 100, 165). By that year, the managers (coaches in Australian and American parlance) of all eight national-league teams had paid positions even though some of them were part-time.

3. Across the country as a whole, in 2016, the ethnic make-up of Fiji was as follows: Indigenous Fijians 56.8%, Fiji-Indians 37.5%, Rotumans 1.2%, and Others 4.5% including Europeans, part-Europeans, other Pacific Islanders, and Chinese (source: CIA World Fact Book, 2016). Most Fiji-Indians are descendants of the indentured labourers brought from India to Fiji by the British between 1879 and 1916 to work on the sugar-cane plantations. For a history of the Sikhs in Fiji see Gajraj Singh (Citationn.d.). For a history of the Chinese in Fiji see Ali (Citation2002).

4. For coup-leader Colonel Sitiveni Rabuka’s worldview and justification for the 1987 coups see Eddie Dean and Stan Ritova’s Rabuka: No other way (Dean & Ritova, Citation1988).

5. Population figures are 2018 estimated figures sourced from the following website: http://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/fiji-population/.

6. Source: http://www.rsssf.com/tablesn/nz-intres-det80.html .

7. Sources for 17 November (versus New Zealand) and 19 November 1988 (versus New Zealand) match results: Prasad (Citation2013), p. 116; http://www.rsssf.com/tablesn/nz-intres-det80.html .

8. Lautoka Blues dominated the competition during its (Lautoka’s) glory years, 1938–1959. Since then it has only recaptured its brilliance in short spurts such as the 1984–1985 team (Prasad, Citation2013, p. 103). Henry Dyer attributes Lautoka’s failure to win further trophies after 1985 (other than the 1988 national-league title) to the uncertainties associated with the 1987 military coups plus Ba’s on-field rebirth as a soccer power at around the same time.

9. Prasad (Citation2013), p. 103.

10. Part-European is the official name given to those of mixed European and other heritage (usually white British and indigenous Fijian) in Fiji censuses and is a left-over category from the days of British colonial rule. It also represents a distinct community today, which still exists somewhat separately from the other communities. At the funeral of an auntie of Henry Dyer, held at the Our Lady of Perpetual Help Roman Catholic Church in Lautoka around 2014, his part-European relatives filled one half of the church building whilst his indigenous Fijian relatives (or those who self-identified that way) congregated in the other half.

11. There were five Sami brothers: Narend (eldest), Sunil, Kamal, Julie, and Vimal (youngest). Of these five, all but Sunil played for Ba while Julie and Vimal also played for Fiji and Kamal for Fiji Youth (sources: author’s interview with Julie Sami, 1 October 2015; Ba Football Association, Citation2012). These Sami brothers should not be confused with the other set of Sami brothers which included Labasa player Anand Sami. From 1974 until 1979 Jagannath (or Jagnnath) represented the Labasa Association national-league team along with his brothers Anand, Gopal, and Abhilasha. Jagannath represented the Fiji national team with brother Anand in 1976. In 2015 Jagannath was back in the news when he emerged as a National Federation Party (NFP) candidate in the 2015 Fiji national elections (source: NFP leaflet, dated 23 July 2014).

12. In that era, IDC games had a regular playing time of only 60 minutes so as to fit more games into a single weekend of fixtures.

13. FFA officials rejected the eccentric compromise idea first put forward by Nadi and Ba that the trophy should be shared by the two teams for six months each, a classic example of pragmatic Fijian culture.

14. The logic here was similar to what would happen if a World Cup Final was tied and there were no penalty shootouts allowed. The replay match would be held in the same city (or at least country) as the original final.

15. S.M. Singh, as he was commonly known, managed the Fiji national team from 1960–1976.

16. Julie Sami says he gave his left-wing position in the Ba and Fiji team to his brother Vimal as he moved down to the sweeper position in the Ba team and, at around the same time, disappeared from the Fiji team line-up.

17. Rewa’s last IDC win, prior to the 2001 victory, was in 1972.

18. Scores and goal-scorers are provided by the Western Australian soccer historian Richard Kreider (Kreider, Citation1996, pp. 172, 181, 188, 190).

References

- Ali, B. N. K. (2002). Chinese in Fiji. Suva: Institute of Pacific Studies.

- Ba Football Association. (2012, October 12). Samis’ love for soccer. Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/notes/ba-football-association/samis-love-for-soccer/451904628182381/

- Bennett, A. (2005). Editorial: Popular music and leisure. Leisure Studies, 24(4), 333–19. doi:10.1080/02614360500200656

- Butcher, R., & Schneider, A. J. (2007). Fair play as respect for the game. In W. J. Morgan (Ed.), Ethics in sport (2nd ed., pp. 119-140). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Dean, E., & Ritova, S. (1988). Rabuka: No other way. Suva: The Marketing Team International Ltd.

- Delattre, E. J. (2007). Some reflections on success and failure in competitive athletics. In W. J. Morgan (Ed.), Ethics in sport (2nd ed., pp. 195-200). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Dixon, N. (2007). On winning and athletic superiority. In W. J. Morgan (Ed.), Ethics in sport (2nd ed., pp. 165-180). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Gorman, J. (2017). The death & life of Australian soccer. St. Lucia, Brisbane: University of Queensland Press.

- Guardian Sport Online. (2014, November 11). The forgotten story of … the socceroos’ defeat to Fiji. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/sport/blog/2014/nov/11/the-forgotten-story-of-the-socceroos-defeat-to-fiji

- James, K. (2015). Sugar city blues: A year following Lautoka Blues in Fiji’s National Soccer League. International Journal of Soccer, 1(1), 1–25. Retrieved from http://www.journalnetwork.org/journals/international-journal-of-soccer/papers/sugar-city-blues-a-year-following-lautoka-blues-in-fijis-national-soccer-league

- Kreider, R. (1996). A soccer century: A chronicle of Western Australian soccer from 1896 to 1996. Leederville, Perth: SportsWest Media.

- Kreider, R. (2012). Paddock to pitches: The definitive history of Western Australian football. Leederville, Perth: SportsWest Media.

- Lipsitz, G. (1994). Dangerous crossroads: Popular music, postmodernism and the poetics of place. London: Verso.

- O’Brien, L. (2012). Can I have a taste of your ice cream. Punk & Post-Punk, 1(1), 27–40. doi:10.1386/punk.1.1.27_1

- Prasad, M. (2008). Celebrating 70 years of football, 1938–2008. Suva: Fiji Football Association.

- Prasad, M. (2013). The history of Fiji Football Association 1938–2013. Suva: Fiji Football Association.

- Singh, G. (1988, November 28). Ba magic lifts Fiji to victory. Fiji Times, pp. 32.

- Singh, G. (n.d.). The Sikhs of Fiji. Suva: South Pacific Social Sciences Association.

- Thompson, T. (2006). One fantastic goal: A complete history of football in Australia. Sydney: ABC Books.