Abstract

Seventeenth-century Dutch genre painter Jan Miense Molenaer (1610/1611–1668) often depicted the sitting male, elegant, full-size lute player for about a decade. He changed the figure little except for costumes, props, and environment from one painting to the next. This author suggests that Molenaer employed a print model, turning it into repeatable patterns in order to copy it with little adjustments from painting to painting. The practice was first used by artists in the South Netherlands. A prolific painter, Molenaer was able to use his creative process for profitable marketing purposes.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This essay focuses on the figure of the lute player in the art of Jan Miense Molenaer (1610/11-1668), the Dutch seventeenth-century genre painter. Genre painting, or “scenes of everyday life,” as commonly known, was a favorite subject in the Dutch Republic. Molenaer’s depiction of this figure with little change in painting after painting posed the question how did he achieve this endeavor? The author suggests that the artist worked out a process of using a print model, aided by patterns that gave him the tool to create this often repeated figure with great similarity. The artist was a clever business man who used this practice to streamline his production of paintings for marketing purposes.

1. Introduction

A small painting, entitled Self-Portrait as a Lute Player, by Haarlem genre painter Jan Miense Molenaer (1610/11–1668) depicts a fashionable full-length young male sitting erect on a high chair while he holds a lute (Figure ). The painting is a precious art object, a jewel, in Molenaer’s oeuvre. Between 1629/1630 and about 1640 the artist repeatedly used the full-length sitting male lute player in company of others. However, he most likely rendered him only once alone as in this painting.Footnote1

Figure 1. Jan Miense Molenaer, Self-Portrait as a Lute Player, c. 1636/1637, oil on panel, 38.7 × 32.4 cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. Lee and Juliet Folger Fund, inv. no. 2015.20.1.

Molenaer’s preoccupation with the lute player for an extended period of time is intriguing. He concentrated on the elegant full-length sitting male figures, either holding the lute or playing it. Although this protagonist in Dutch art had its origin in the early 1600s within the fashionable garden parties of David Vinckboons (1576-before 12 January 1633), in Molenaer’s art the lute players took center stage with only slight changes from painting to painting. The artist revised their gestures and their limbs, but retained a similar basic stance for each, repeating them. He elaborated more on the different costumes, props, and scenery for the musician in successive paintings.Footnote2

In the following it will be argued that the artist apparently used a print model for his painted lute players, transforming the original source and combining it with real life observations. This model was an engraving by Pieter de Jode I (1572/1573–1634) and it most likely came from Haarlem. De Jode’s print may have been inspired in turn by another engraving of Marcantonio Raimondi (c. 1470/1482–1527/1534). Raimondi’s work could have been the first one in a chain of images which provided a prototype for a number of artists, among them de Jode and consequently Molenaer. Molenaer’s frequent use of lute players with little change from one painting to the next indicates his aim to accelerate his production of paintings by repeating a successful motif for marketing purposes.

The methodology in this essay will be through stylistic analysis without the discussion of the iconography of the lute player. The latter aspects have been explored amply by previous scholarship. Matters relating to iconography will be treated here sparingly, only as required by the development of the essay. By stylistic analysis it is meant to find commonalities among several of Molenaer’s lute players, focusing on posture, gesture, and pose as well pointing out deviations from them. This approach enables the author to explore and to suggest how the remarkable similarity among the figures may have been achieved, what tools were used to further their becoming, and where did they lead the artist in context of his overall oeuvre, creating a large cache of paintings that he left behind. At the end, the research establishes that Molenaer was an ingenious artist who excelled in marketing his own work, using available resources to further his ambitions. By working out a system of production with a definite purpose he was able to carve a place for himself in the bourgeoning art market in both Haarlem and later in Amsterdam. The research also details the working procedure the artist used with the lute players. He followed precedents from earlier workshop practices in the South Netherlands (today’s Belgium) which Molenaer cleverly exploited to his own endeavors all through his life.Footnote3

2. Lute players in Dutch paintings in the early 1600s

Scholars have traditionally credited the Utrecht Caravaggisti with the introduction of the half-length lute players in Holland, either as single figures or with other music-making companions in an indoor setting. Artists of the Frans Hals (1581/1585–1666) circle, to which Molenaer belonged along with his wife, Judith Leyster (1609–1660), often depicted lute players. Hals himself used such figures sparingly and invariably at half-length.

While Hals’s oeuvre does not suggest his interest in the full-length sitting male lute player, some of the artists in his circle active in the 1620s did explore the type. Hals’s younger brother, Dirck (1591–1656), incorporated such figures into his paintings, as in his Musical Company, 1623, (Hermitage, St. Petersburg). Similarly the little known Haarlem artist and Hals follower, Isack Elyas (active c. 1610-1630), also painted a full-length sitting lute player in his Merry Company, c. 1627 (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam).

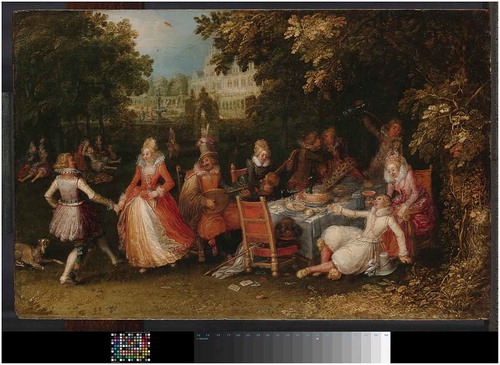

Full-length sitting male lute players appeared earlier in paintings of the sumptuous outdoor parties of David Vinckboons in the 1610s. One notable example is his Garden Party where an elegant merry company is entertained by a couple of music making companions (Figure ). One of them is a lute player. A similar painting at the Akademie der bildenden Künste, Vienna by this artist depicts a musical trio that includes again a lute player. They perform to a celebratory retinue in a garden setting. Vinckboons’ lute players, however, are small and do not occupy the focus of the composition. Esaias van de Velde (1587–1630), his presumed pupil, also rendered a full-length, sitting male lute player as participant of a musical group in the open air. An etching by Gillis van Scheyndel (fl. 1622–1654), after a design by Esaias, depicts such a company, entitled Music Makers in a Landscape, 1622 (Figure ). Here the lute player takes on prominence at the center of the composition in a pose comparable to Molenaer’s Self-Portrait as a Lute Player, however, both of his feet touch the ground. Esaias’ protagonist also holds the instrument in reverse from Molenaer’s. It is notable that the lute player in this print is portrayed as left handed, suggesting its dependence on another image, whether it be drawing, painting, or print.

3. Molenaer’s Lute players

Molenaer’s lute player in the period c. 1629–1640 gains increasing prominence in his paintings. He is depicted most often in the company of others, indoors, instead of just being part of garden parties and musical companies that appeared earlier in the century. The artist first included the lute player in an indoor multi-figure composition, The Ruychaver-van der Laen Family c. 1629–1630 (Museum van Loon, Amsterdam). However, the figure takes center stage in his The Duet (Figure ). Here the lute player strikes a pose similar to Self-Portrait as a Lute Player.Footnote4

Figure 4. Jan Miense Molenaer, The Duet, c. 1630-31, oil on canvas, 64.1 × 50.5 cm, Seattle Art Museum, Seattle, WA, Samuel H. Kress Collection, photo: Paul Macapia, inv. no. 61.162.

Contemporary with The Duet is A Young Man Playing the Theorbo and a Young Woman Playing the Cittern (Figure ). The setting is more spacious and elaborate than in the previous painting. The gesture of the male, holding the instrument, is similar to the lute player’s in The Duet. He strums his double-headed lute and may also sing that we can infer from his slightly open mouth. His right leg is extended and his left is hidden behind the skirt of the female.

Figure 5. Jan Miense Molenaer, A Young Man Playing a Theorbo and a Young Woman Playing the Cittern, c. 1630-1632, oil on canvas, 64 × 84 cm, National Gallery, London, acquisition credit: bought (Clarke Fund), 1889, inv. no. NG 1293.

Next Molenaer includes the lute player in his marvelously elaborate outdoor scene, Allegory of Marital Fidelity (Figure ).Footnote5 A three-some musical group is depicted in the company of an elegant retinue on a terrace. The lute player occupies the left foreground. His pose is identical to the figure in Self-Portrait as a Lute Player, although he is in three-quarters view. The artist returns again to an indoor multi-figure composition in his Self-Portrait with Family Members (Figure ). Here the lute player is differentiated from his previous counterparts. He is in full frontal pose and discernibly sings while strumming his lute. The most substantial difference is that he drapes his right leg over his left thigh.Footnote6 This motif mimics the lute player’s pose in the artist’s painting, The Duet, c. 1635–1636, (Collection of Mr. Eric Noah).

Figure 6. Jan Miense Molenaer, Allegory of Marital Fidelity, 1633, oil on canvas, 99 × 140.9 cm, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, VA, Adolf D. and Wilkins C. Williams Collection, © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, photo Katherine Wetzel, inv. no. 49.11.19.

Figure 7. Jan Miense Molenaer, Self-Portrait with Family Members, c. 1634-1636, oil on panel, 62.3 × 81.3 cm, Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem, on long term loan from the Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands, Amsterdam, inv. no. 75-332.

The above paintings are Molenaer’s most important works where he included the lute player. It is apparent that the figures have similarities of posture, poses, and gestures. The visual evidence supports the hypothesis that he employed a model for his lute players and adjusted details from painting to painting.

4. The influence of prints on Molenaer’s Lute players

What model could have served for Molenaer’s lute players? An engraving by Antwerp artist, Pieter de Jode I called Musical Company, after the drawing by Adam van Noort (1562–1641), one of Rubens’ teachers, could have served as a prototype for Molenaer (Figure ). This print includes a figure in nearly identical pose as Molenaer’s Self-Portrait as a Lute Player. Differences are the placing of the right foot and the three-quarters view of the figure. He also seems to strum his lute rather than tune it and he is in the company of others. De Jode’s print may have influenced other printmakers as the following examples will show.

Figure 8. Pieter de Jode I after a drawing by Adam van Noort, Musical Company, engraving, c. 1594-95, 16 × 19.6 cm, British Museum, London, ©The Trustees of the British Museum, inv. no. 1856, 0308.160 (artwork in the public domain).

Hendrick Goltzius (1558–1617) designed a series of seasons engraved by Jan Saendredam (c. 1565–1607) after the master’s drawing around 1594–1595. In one of the prints, Spring, a courting couple is making music in an arbor (Figure ).Footnote7 The elegant male plays the lute in a comparable pose as de Jode’s lute player; however, his left foot is hidden. Jan (Johannes) Theodore de Bry (1561–1623) copied de Jode’s engraving in reverse in 1596. Yet in another print, Musical Company with Time, Haarlem artist (Claes) Gillis van Breen (active in Haarlem c. 1595–1622) also copied de Jode’s engraving, adding the allegorical figure of Time to the musical group (Figure ). De Breen’s copy after de Jode’s Musical Company shows the popularity of the print in Haarlem. It encourages the question concerning the possible origin of a common prototype that served these artists as well as Molenear in rendering their lute players.

Figure 9. Jan Saendredam after Hendrick Goltzius, Spring, c. 1594-95, engraving, 20.5 × 14.5 cm, from a series of four plates, British Museum, London, ©The Trustees of the British Museum, inv. no. D,3.240 (artwork in the public domain).

Figure 10. Attributed to Gillis van Breen, after Pieter de Jode I, Musical Company with Time, c. 1600, etching and engraving, 15.6 × 19.5 cm, National Gallery of Denmark, Kongelige Kobberstiksamling, Copenhagen, SMK photo, inv. no. KKSgb3118.

An engraving by Marcantonio Raimondi just may have started the chain of similar lute players in prints that circulated in Haarlem as well as seen in Molenaer’s paintings. Raimondi’s Portrait of Giovanni Filoteo Achillini (1466–1538), also known as The Guitar Player, depicts the Bolognese humanist, poet, and musician (Figure ).Footnote8 He is shown outdoors against a spacious landscape that contains features of Northern landscape prints.Footnote9 His face is in three-quarters view. He holds a guitar instead of a lute. He is bent forward and his slightly open mouth suggests he may even sing while strumming his instrument. This print may have found its way from Italy to the active print market of sixteenth-century Antwerp. From there it easily reached Haarlem. In the heterogeneous artistic community there, it could have circulated among workshops for an extended time.

Figure 11. Marcantonio Raimondi, Portrait of Giovanni Filoteo Achillini, c. 1504-1505, engraving on parchment, 18.2 × 12.9 cm, Albertina, Vienna, inv. no. DG1971/432.

Whether Marcantonio Raimondi’s print was the actual prototype for all those lute players by de Jode and others and consequently Molenaer, cannot be currently substantiated with documentary evidence. However, visual observation affords a meaningful similarity among the lute players discussed above. In all probability the prototype for Molenaer’s lute players remains the engraving, Musical Company by Pieter de Jode I. De Jode and van Breen can be linked to Goltzius’ workshop in Haarlem with documentary evidence.Footnote10 Goltzius had direct ties to the Antwerp printmaking and print publishing circuit. It is reasonable to think that it was from his workshop that the full-length, sitting male lute player in print found its way to painters studios in Haarlem, among them Molenaer’s. Raimondi’s print could have been the prototype which became a staple in the Dutch Republic through adaptation and reinterpretation by intermediary sources in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.

5. Molenaer’s workshop practice and creative process in context

It is possible that Molenaer and other artists have seen the poses and gestures of the lute players that were discussed above in everyday life. However, in the context of Molenaer’s creativity it is reasonable to connect his lute players to a print prototype. Their similarity and frequent repetition by the artist within an extended time period suggest a deliberate practice for a definite purpose once the formula was established.

He routinely employed repeatable models for his painted figures from the beginning of his career. The lute player was one of his favorite motifs prior to 1640 where he undertook this method regularly.Footnote11 Using prints as models was crucial to his workshop practice. The hypothesis may be drawn that a reason for doing so was to accelerate the production of his paintings. The practice was important to him in order to break into the open market both in Haarlem and later in Amsterdam where he moved in 1636.

To replicate his figures with subtle adjustments he likely created cartoons or partial cartoons as patterns to streamline his production. Cartoon is the modern word for pattern from Flemish origin of patron. Molenaer possibly used prints as cartoons for his figures on the same scale as the images to be painted. He then transferred the images to the canvas or wood support from painting to painting with various transfer techniques. He apparently manipulated poses and gestures in the underdrawing stage and finished details, such as costumes and props, at the final phase of the painting.Footnote12

With the lute player Molenaer established an enduring workshop practice in order to serialize his paintings. Serial production evidently was a promising proposition for him with an eye on the open market. It appears he prepared himself to this venture. He must have started to accumulate amounts of artist’s materials already at this stage of his career. His posthumous inventory contains numerous panels and picture frames.Footnote13 Subjects with the lute player occurred in his repertoire for about a decade. After 1640, once his paintings with the lute player ran their course and did not go any further, he switched over to low life genre. He, however, continued to follow the same workshop practice and creative process he employed previously, turning out paintings en masse although lower in quality then in previous years.

The suggestion that he increased his output for marketing purposes can be substantiated with documentary evidence. Molenaer was a prolific artist whose overall oeuvre is estimated about 225–250 paintings.Footnote14 His name appeared frequently in estate auctions and inventories.Footnote15 He was connected to one of the most reputable art dealers in Amsterdam, Johannes de Renialme, whose inventories contained numerous paintings by Molenaer.Footnote16 In all appearances his workshop practice and the creative process he employed in the paintings with the lute players were deliberate choices in order to increase his production for the open market.

Molenaer’s workshop practice and creative process was not new. The use of print and drawing prototypes as models and the exchange of figures with little or no change in several paintings to serialize production for the open market evolved from some fifteenth- and sixteenth-century workshops in the South Netherlands. Lorne Campbell convincingly demonstrated this practice in the Hans Memling workshop. Here the exchange of models among successive paintings was frequent and included standardization in portraiture, with appropriate individualization in the later stages of the painting (Campbell, Citation1995. See also, Campbell, Citation2005). The Master of Frankfurt (1460-c. 1533) also ran a large workshop where models were repeatedly used to serialize production. A large cache of prints and drawings provided models.Footnote17 He was a connecting link for such practices between the late fifteenth- and the sixteenth-century workshops such as the ones of Gerard David (c. 1455–1523) and Jan Gossaert (c. 1478–1532). In David’s busy workshop, detailed drawings provided models which were repeated several times with no or little change. Not only complete cartoons but partial cartoons were used to replicate images (Ainsworth, Citation1998). In Jan Gossart’s atelier his most successful inventions served as models for serial production that were copied after his death and exist in countless replicas (Van den Brink, Citation2002).

6. Conclusion

Molenaer’s elegant lute players constitute a special group of figures. It appears he found an ideal figure type in this full-length, sitting male musician. He repeated the figure with subtle adjustments for about a decade. He most likely used a print prototype as model that was in currency among workshops in Haarlem. It is uncertain that Marcantonio Raimondi’s engraving Portrait of Giovanni Filoteo Achillini directly reached the Dutch Republic, especially Haarlem. However, it seems possible from visual evidence that this engraving was the first link in a chain of print sources that influenced Molenaer’s lute players. His workshop practice and creative process was deeply rooted in late fifteenth- and sixteenth-century precedents of the South Netherlands. He serialized his paintings with the lute player motif, accelerating his production, in turn furthering his marketing ambitions.Footnote18 Molenaer’s single figure where he depicted himself alone in Self-Portrait as a Lute Player is perhaps the most meaningful one in the line of lute players. In this painting he may have exhausted the motif and was ready to embark on a new venture, low life genre. He continued to explore this subject until the end of his career. He used, however, the well-worn workshop practice and creative process that he so single mindedly undertook with the lute player.

Acknowledgements

I thank Arthur J. DiFuria for reading the original manuscript and providing valuable comments and suggestions to the text. I am grateful to Christine M. Boeckl, Jacquelyn Coutré, and Alison M. Kettering for their assistance and advice that contributed to the success of the essay.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Eva J. Allen

Eva J. Allen is a specialist in Dutch seventeenth-century art and Renaissance prints. She holds a Ph.D. from these areas of endeavor. Her research interests include Haarlem landscape painting with concentration on Pieter Molyn (1595-1661). She also studies genre paintings of the period, focusing on Jan Miense Molenaer (1610/1611-1668). She has related this artist’s paintings to print models, especially engravings and etchings after the inventions of Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1525/30-1569). Her publications on Molyn and Molenaer appeared in art journals and books both in Europe and North America. Dr. Allen taught art history for eighteen years at the University of Maryland University College (UMUC) and presently is an independent scholar.

Notes

1. I thank A.K. Wheelock, Jr., for providing a digital file of the painting and giving special permission for publishing it, 11 January 2012. The date c. 1640 was previously assigned to the painting. This is how it appeared in an essay by A. Libby in 2015. See Libby (Citation2015), reproduced. D. P. Weller dated the painting c. 1635 in 2002. See Weller. (Citation2002, cat. no. 22, p. 130). Most recently Wheelock kindly informed me that this date has been revised to c. 1636/1637 based upon stylistic grounds and technical examination and provided written record for the reasons of the revisions. Communications, 21 February 2018. The author of this essay believes the date of c. 1640 is appropriate. This observation is based on not just stylistic comparison but also on the special place this lute player occupies among all the previous ones. The artist here removed the figure from the complicated genre mode of earlier paintings and presented himself in the guise of his favorite protagonist. The lone lute player became his doppelganger. For a comparable half-length self-portrait of the artist with less elaborate hair style but similar facial features also see: Weller. (Citation2002, cat. no. 30, p. 156) created c. 1639/1640 and housed in the Bayerische Staatsgemӓldesammlungen.

2. For Molenaer’s use of costume and props see: Von Bogendorf Rupprath (Citation2002).

3. For the various avenues of interpretation of the iconography of the lute player in Dutch art see Welu. (Citation1993); De Jongh and Luijten (Citation1997); De Jongh (Citation2000). For the role of the lute player, especially of Molenaer’s Self-Portrait as a Lute Player, see Weller. (Citation2002, cat. no. 22, p. 130).

4. For the dating of The Duet see Weller. Citation2002, cat. no. 7, p. 84. The instrument the lute player strums in this painting and the next is not a therbo. It is an extended, or double-headed lute often referred by music specialists as a “Molenaer lute.” Schlegel (Citation2016).

5. For the iconography of this painting see Van Thiel (Citation1967–1968).

6. It is possible that Molenaer was familiar with the engraving by Cornelis Cort, “The Thorn Puller” after the antic bronze sculpture “Spinario” and placed the legs of his protagonist accordingly. For Cort’s print see Leeflang (Citation2000).

7. Goltzius’ Spring is part of his third cycle of the seasons. For full discussion and illustration of the whole series see Lauterbach (Citation2004–2005). For the description of the series see Boon (Citation1980). For the drawing of the Spring see Reznicek (Citation1961).

8. For the full discussion and dating of the print see Faietti and Oberhuber et al. (Citation1988). The date as late as c. 1508-1511 was considered previously for the engraving. Initially it was also suggested that the engraving depicts the philosopher Alessandro Achillini, brother of Giovanni Filoteo Achillini, based on a drawing in the Uffizi with false inscription.

9. It is widely known that Marcantonio borrowed landscape elements from both Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528) and Lucas van Leyden (c. 1494-1533). For the influence of Dürer’s landscape elements on Marcantonio see Shoemaker and Broun (Citation1981). Pon also refers to Marcantonio’s borrowings from “Northern landscape” elements. Pon (Citation2004). For the influence of Lucas van Leyden on Marcantonio see Bart and Filedt Kok (Citation1998).

10. Pieter de Jode I was one of Goltzius’ most talented pupils according to Karel van Mander I (1548-1606), as noted by Luijten, 1997, p. 77. De Jode spent time in Italy before 1595. He was back in Antwerp in 1599-1600 and inscribed in the Antwerp Guild of St. Luke, Van Mulders (Citation1996). His sojourn in Goltzius’ workshop possibly occurred somewhere between the date of 1595-1599. The presence of Gillis van Breen, however, is more elusive. Little information is available about his connection to Goltzius. We know that the master prepared four portrait drawings of this engraver. He presumably was Goltzius’ friend and not his pupil or associate. Schapelhouman (Citation2000). See also Spicer (Citation1991).

11. See: Allen (Citation2011). Allen discussed several Molenaer paintings where the artist most likely used print prototypes for his painted figures, some starting even before the artist’s first signed and dated paintings in 1629.

12. Molenaer’s creative process can be described also with concepts J.M. Montias introduced to art history: product and process innovation. The first concept, he explained, would involve introduction of a new “commodity” [for example a motif], or an old one with changes. The second concept would involve a “cost-cutting process” that would change the appearance of the product. In art, he said, both go hand in hand. Montias (Citation1990). In case of Molenaer’s lute players the artist introduced a new motif early in his career. He employed it with subtle changes from painting to painting for a decade most likely through the use of cartoons or partial cartoons as “cost-cutting” devices.

13. In the loft of Molenaer’s home the following are listed:26 panels of the same format; 32 panels some larger for a picture; 16 large prepared panels for a picture; 5 panels for a picture; 14 ebony frames; 11 large prepared panels.’ For the full inventory see (Weller, Citation2002, pp. 181–187).

14. Weller (Citation2002, p. 7) (endnote 4).

15. Montias placed Molenaer in the fourth place among 31 artists with the greatest number of paintings by lots. The artist’s name appeared with 62 mentions in 33 inventories and 24 mentions in dealers’ inventories. Montias (Citation2004–2005).

16. Goosens (Citation2001). The beginning of the connection of Molenaer and Johannes de Renialme is placed in 1637. Perhaps the relationship came about from the fact that Molenear was not yet a member of the Amsterdam Guild of St. Luke and thus he could not sell his work out of his shop. Thus Molenaer sought the help of a professional art dealer to start marketing his paintings. Renialme’s inventory was drawn up twice in 1640 at the first time and again after his death in 1657. The 1640 inventory contained twenty one paintings from Molenaer and the 1657 inventory contained seven. See Bredius (Citation1915).

17. Goddard (Citation1984, pp. 95, 104–105) respectively. For the discussion of the workshop’s repeated use of brocade patterns see Goddard (Citation1985).

18. It has been suggested that Leiden genre painter Gerrit Dou repeated the niche motif in several of his paintings as a marketing strategy. Ho (Citation2007). However, there is no evidence that the artist did this to accelerate his production of paintings. In fact, he took long, laborious time to finish each painting. It appears Dou responded to the demands of a discerning elite clientele’s preference by replicating a popular motif.

References

- Ainsworth, M. W. (1998). Gerard David: Purity of vision in an age of transition (pp. 17–19, 49). New York, NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Allen, E. J. (2011). An early jan miense molenaer in the museum of fine arts, budapest. Bulletin Du Musée Hongrois Des Beaux-arts, 114–115, 79.

- Bart, C., & Filedt Kok, J. P. (1998). The taste for Lucas van Leyden’s prints. Simiolus, 26, 18–14. doi:10.2307/3780871

- Boon, K. G., (ed.). (1980). Hollstein’s, Dutch and Flemish etchings, engravings, and woodcuts, ca. 1450-1700 (Vol. 23, nos. 93-96, pp. 71–72). Amsterdam: Van Gendt & Co.

- Bredius, A. Künstler Inventare. Den Haag 1915, 8 vols., pp. 228–239, vol. 1.

- Campbell, L. (1995). Memlinc’s creative process as seen in his paintings in the National Gallery, London. In: H. Verougstraete & R. van Shoute (eds.), Le dessin sous-jacent dans le processus de creation, Colloque X 5–7, September 1993 (pp. 149–152). Louvain: Université Catholique de Louvain.

- Campbell, L. (2005). Memling and the Netherlandish Portrait tradition. In T. H. Borchert (Ed.), Memling and the Art of Portraiture (pp. 56–67). London: Thames & Hudson.

- De Jongh, E. (2000). Questions of Meaning: Theme and motif in Dutch seventeenth-century painting, trans. and ed. by Hoyle, M. (pp. 93–95). Leiden: Primavera Pers.

- De Jongh, E., & Luijten, G. (1997). Mirror of everyday life: Genre prints in the Netherlands 1550–1700. 95–97. Snoeck-Ducaju & Zoon, Ghent and in cooperation with the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. trans. by M. Hoyle.

- Faietti, M., Oberhuber, K., Anselmi, G. M, De Maria, S., Ebert-Schifferer, S., Giombi, S., ... Scaglietti, D. (1988). exh.cat. Bologna e l’umanesimo 1490–1510 ( cat.no. 27 pp. 142) . Bologna: Pinacoteca Nazionale.

- Goddard, S. H. (1984). The master of Frankfurt and his shop (pp. 95, 104–105). Brussels: Paleis der Academien.

- Goddard, S. H. (1985). Brocade patterns in the shop of the Master of Frankfurt: An accessory to stylistic analysis. The Art Bulletin, 67, 401–417. doi:10.1080/00043079.1985.10788280

- Goosens, M. E. W. (2001). Schilders en de markt: Haarlem 1605–1635. Ph.D. diss. Leiden: University of Leiden. p. 262.

- Ho, A. (2007). Gerrit Dou’s niche pictures: Pictorial repetition as a marketing strategy. Athanor, 25, 59–67.

- Lauterbach, C. (2004–2005). Masked Allegory: The cycle of the four seasons by Hendrick Goltzius, c. 1594-95. Simiolus, 31, 310–321. doi:10.2307/4150596

- Leeflang, H. (ed.). (2000). The new Hollstein Dutch and Flemish etchings, engravings and woodcuts 1450-1700 (Vols. 3 no. 215, pp. 142). Rotterdam: Sound & Vision Publishers.

- Libby, A. (2015, Fall). Jan Miense Molenaer, Self-Portrait as a Lute player. National Gallery of Art Bulletin, 53, 38–39. reproduced.

- Montias, J. M. (1990). The influence of economic factors on style. De Zeventiende Eeuw, 6, 51–52.

- Montias, J. M. (2004–2005). Artists Named in Amsterdam Inventories, 1607-80. Simiolus, 31, 326. doi:10.2307/4150597

- Pon, P. (2004). Raphael, Dürer, and Marcantonio Raimondi (pp. 121). New Haven and London: Copying and the Italian Renaissance Print.

- Reznicek, E. K. J. (1961). Die Zeichnungen von Hendrick Goltzius: (Vol. 2, no. K 155 p. 304). Utrecht: Haentjens Dekker & Gumbert.

- Schapelhouman, M. (2000). Een nieuw-ontdekt portrait van Gillis van Breen, getekend door Hendrick Goltzius. Bulletin Van Het Rijksmuseum, 48, 154.

- Schlegel, A. (2016). The Lute in the Dutch golden age: What we know and what we play today In J. Burgers (ed.), The Lute in the Netherlands in the Seventeenth Century ( cat.no. 1 pp. 85–89). New Castle, Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Shoemaker, I. H., & Broun, E., exh.cat. (1981). The engravings of Marcantonio Raimondi (pp. 52). Lawrence: The Spencer Museum of Art.

- Spicer, J. (1991). Nicolaus Breau and Gillis van Breen two printmakers or one? Print Quarterly, 8, 275–280.

- Van den Brink, P., Allart, D., Currie, C., Duckwitz, R., Folie, J., Fraiture, P. & Harleman, S. (2002). The art of copying: Copying and serial production of paintings in the Low Countries in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries In P. van den Brink (Ed.), Brueghel Enterprises (pp. 27–28). Maastricht: Ludion; Bonnefantenmuseum.

- Van Mulders, C. (1996). Pieter de Jode. In J. Turner (ed.), The Grove Dictionary of Art (Vol. 17, pp. 598-599). New York: Oxford University Press, Inc.

- Van Thiel, P. J. J. (1967–1968). Marriage Symbolism in a Musical Party by Jan Miense Molenaer. Simiolus, 2, 90–99. doi:10.2307/3780456

- Von Bogendorf Rupprath, C. (2002). Molenaer in his studio: Props, models, and Motifs. In D. P. Weller, et al. (Ed.), exh.cat. Jan Miense Molenaer: Painter of the Dutch Golden Age (pp. 27–41). Raleigh: North Carolina Museum of Art.

- Weller, D. P., Bogendorf, R. C, & Westermann, M. (2002). exh. cat. Jan Miense Molenaer: Painter of the Dutch Golden Age ( cat. no. 22, pp. 130) . Raleigh: North Carolina Museum of Art.

- Welu, J., Biesboer, P., Broersen, E., Groen, K., Hendriks, E., Hofrichter, F. F., Kloek, E., Von Bogendorf Rupprath., ... Wijsenbeek-Olthuis, T. (1993). exh.cat. Judith Leyster: A Dutch Master and Her World. Worcester: Worcester Art Museum.