Abstract

Twitter is one of the many communications means connecting groups of users with similar interests. This study analyses tweets related to halal cosmetics in order to gain insights about halal cosmetics chatter on Twitter. The researchers extracted Twitter data related to halal cosmetics (2008 to 2018) using English and Bahasa Malaysia keywords and examined a sample of 19,449 tweets. They found that halal cosmetics began to gain popularity in 2014 and, in terms of geo-location, the highest number of tweets pertaining to halal cosmetics came from Indonesia, followed by Malaysia and the United Kingdom. Nevertheless, they found that only 17 percent of the users revealed their geo-location. This study examines the content of tweets related to halal cosmetics with the aim to help increase knowledge about issues individuals are discussing when social networking with others about halal cosmetics. Specifically, the study analyses the text of the tweets, categorises them as information, promotions or advice, and examines the halal cosmetics brands/products that are most tweeted. The researchers found that most of the tweets were either providing information or promoting a particular product or event. The study also identified the top twenty-five brands tweeted. The findings could help the halal cosmetics players to strategize their future marketing plans.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This study analyses tweeter data (from 2008 to 2018) related to halal cosmetics. The analysis allows us to gain insights about halal cosmetics chatter on Twitter. This in turn will increase our knowledge on issues that individuals are discussing when social networking with others about halal cosmetics.

1. Introduction

The Halal cosmetic industry experienced exponential growth over the last few years. The demand for it continues to increase as the world’s Muslim population increases and awareness of halal cosmetics and personal care products grows (Ali, Halim, & Ahmad, Citation2016). Technavio’s analysts forecast growth within the Global Halal Cosmetics and Personal Care Market at a CAGR of 13.55% during the period of 2018–2022 (Technavio, Citation2018). There are numerous studies pertaining to Halal cosmetics, some focussing on consumers’ perceptions. For example, Mohamed and Li (Citation2017) examined the determinants of consumer experience and satisfaction, while Mohezar, Zailani, and Zainuddin (Citation2016) analysed the antecedents of halal cosmetics adoption among young Malaysian Muslim consumers. Briliana and Mursito (Citation2017) investigated the antecedents and consequences of halal cosmetics among young Indonesia Muslim consumers. Other studies focussed on halal cosmetics certification. For example, Annabi and Ibidapo-Obe (Citation2017) concentrated on the United Kingdom, while Jusoh, Kamarulzaman, and Zakaria (Citation2016) focussed on Malaysia. Ali, Halim, & Ahmad (Citation2016), Husain, Ghani, Mohammad, and Mehad (Citation2012), and Swidi, Wie, Hassan, Al-Hosam, and Mohd Kassim (Citation2010) examined the halal cosmetics industry in general. Although these studies provide further understanding of halal cosmetics, there remains a lack of understanding regarding sentiment towards halal cosmetics on social media, particularly Twitter. It is important to address this gap, as social media is recognised as the main means of communication among the world’s population; thus, the growth of halal cosmetics is largely dependent upon it. Consumers can express their brand experiences and opinions, positive or negative, regarding any halal cosmetics product through Twitter. Their tweets may have adverse effects if they are negative. This study examines the content of tweets related to halal cosmetics with the aim to help increase knowledge about what issues individuals are discussing when social networking with others about halal cosmetics. Specifically, the study 1) analyses the tweet texts and categorises them as information, promotions, or advice and 2) examines the halal cosmetics brands/products that are most tweeted. Nevertheless, before addressing these two issues, the study also analyses the trends, origin, and word cloud of halal cosmetics tweets for a period of ten years (2008 to 2018). These analyses provide a general background of halal cosmetics.

The following sections of the paper proceed with a discussion of the study materials (two main areas: Twitter and halal cosmetics) and an explanation of the method used to collect the dataset. Section 3 includes the results and related discussion. Finally, the conclusion section discusses limitations and future studies.

2. Material and method

2.1. Twitter

Twitter is a micro-blogging website, established in 2006, that allows individuals to “tweet” 140-character messages (increased to 280 in 2017). Tweets are immediately visible on the timelines of users’ “followers” and to anyone searching the Twitter website. Interestingly, everyone, even though they are not an identified “follower,” can see the posted tweets. The tweets between users are easy to follow, which can be sent to any other user using their unique @username (known as “mentions”), and users can forward any tweet via the retweet function.

Statista reported that, in Q2 of 2018, approximately 326 million people were active on Twitter, 67 million of whom were in the US, with the remaining users hailing from countries worldwide. Leading these countries were Japan and the UK (Statista, Citation2018). Each day, users send 175 million tweets, which created an enormous amount of data. There are several studies that have used Twitter data to analyse people’s sentiment and opinion on a product, person, event, organization, or topic (Shayaa et al., Citation2018). These studies cover a wide spectrum of topics, such as health and well-being, as well as politics.

Cavazos-Rehg et al. (Citation2016) studied tweets in relation to marijuana, Krauss et al. (Citation2015) conducted a content analysis on hookah-related Twitter chatter, and Cavazos-Rehg et al. (Citation2016) conducted a content analysis on depression-related tweets. Researchers also used Twitter data to provide insight into dietary choices (Abbar, Mejova, & Weber, Citation2015) and predict flu trends (Archrekar, Gandhe, Lazarus, Yu, & Lie, Citation2011). The literature also illustrated research that utilized Twitter data to analyse political-related issues, such as examining the political preferences of the general public (Ceron, Curini, Iacus, & Porro, Citation2013) and predicting elections (Tumasjan, Sprenger, Sandner, & Welpe, Citation2010).

Beyond health, well-being, and political-related issues, researchers also used Twitter data in numerous other areas. For example, Philander and Zhong (Citation2016) analysed tweets to examine customer perceptions about the services provided by resorts, while Yu and Wang (Citation2015) analysed US sports fans’ 2014 World Cup tweets. Mostafa (Citation2018, Citation2019)) examined Tweets on halal food, while Oliveira, Cortez, and Areal (Citation2017) used Twitter data to forecast useful stock market variables, including returns, volatility, and trading volume of a diverse dataset of indices and portfolios. Nguyen et al. (Citation2018) focussed on Twitter sentiments towards and in association with low birth weight and pre-term birth in the USA. Thus far, there is no study utilizing Twitter data to analyse halal cosmetics-related issues; therefore, this study aims to address this gap.

A review of the literature illustrated that different researchers classified Twitter data differently. For example, Gupta (Citation2010) classified them as Opinion Tweets, Problem Tweets, Question Tweets, and Information Tweets, while Zubiaga, Spina, Martınez, and Fresno (Citation2015) classified the Twitter text into News, Ongoing Events, Memes, and Commemoratives. Sriram, Fuhry, Demir, Ferhatosmanoglu, and Demirbas (Citation2010) made, perhaps, one of the first attempts to classify tweets. They classified the tweets into News, Events, Opinions, Deals, and Private Messages. Based on this literature, this study classified the tweets into three main categories: Information, Advice (or Opinion), and Promotions (or Deal). Texts categorized as Information generally contains a narrative about a particular event, product, useful general fact(s) or unmeaningful fact(s) (also known as Chatter). Text categorised as Advice occurs when a Twitter user gives their views about a particular topic (positive or negative). Finally, texts categorised as Promotion generally contain offers on various products or services.

2.2. Halal cosmetics

Halal cosmetics products must receive certification as halal by the relevant certification bodies. In Malaysia, the Department of Islamic Development Malaysia (JAKIM) is responsible for providing halal certification. In addition, JAKIM also published (on February 13th, 2019) a booklet, “The Recognised Foreign Halal Certification Bodies & Authorities.” Halal certification is important, as it gives confidence to the members of the public that the cosmetics products are halal certified.

A cosmetics product is halal if the following conditions are met:

(a) does not comprise or contain any human parts or ingredients derived thereof; (b) does not comprise of or contain any parts or substances derived from animals forbidden to Muslims by Shariah law to use or to consume or from halal animal which are not slaughtered according to Shariah law; (c) does not contain any materials or genetically modified organisms (GMO) which are decreed as najis according to Shariah law; (d) is not prepared, processed, manufactured, or stored using any equipment that is contaminated with things that are najis according to Shariah law; (e) during its preparation, processing, or manufacturing, the product is not in contact and physically segregated from any materials that do not meet the requirements stated in items (a), (b), (c), or (d); and (f) does not harm the consumer or the user (Jusoh et al., Citation2016, p. 38).

According to Ali, Halim, and Ahmad (Citation2016), halal-certified products are more ethical, eco-friendly, organic, and green, with a non-exploitive and humanitarian approach. Bhatia and Jain (Citation2013) further substantiated this viewpoint by expressing that halal products are more natural and eco-friendlier. Aoun and Tournois (Citation2015) stated that halal certification and ingredient certification increase ethical standards and brands which, through halal certification, are fighting against cruelty and environmental pollution and are establishing green marketing.

2.3. Materials

2.3.1. Twitter data extraction

The researchers used thirteen Bahasa Malaysia and English keywords related to halal tourism to extract Twitter data posted from October 2008 through October 2018. Researchers identified the keywords through a brainstorming session. The Bahasa Malaysia keywords used were “kosmetik halal,” “produk kecantikan halal,” and “kecantikan halal,” while the English keywords were based on three main terms: “halal,” “Muslim friendly,” and “Sharia compliance.” The keywords for halal were “cosmetics,” “eyeliner,” “mascara,” “makeup,” “lipstick,” and “skincare;” in addition, the keywords for Muslim friendly and Sharia compliance were “cosmetics,” “skincare,” “lipstick,” and “makeup,”

The extraction of the Twitter data was possible through Twitter’s programming interface (API). Nevertheless, it must be noted that there are some limitations to the use of the API; for example, it only allows collection of returning tweets for up to seven days, and there is a limit to the number of requests to the Twitter server, thus facilitating the collection of only a limited number of tweets for analysis. As it is important for this study to collect a large amount of data, the researchers extracted tweets via the Twitter search feature using a Python script. Subsequently, in order to ensure that the tweets are not duplicated, they calculated the MD5 value of each tweet (MD5 is a hash function that returns a unique value for a given text). Consequently, the researchers extracted 19,449 tweets for use in further analysis.

2.3.2. Twitter text analysis

The Principal researcher exported the text of the tweets into an Excel sheet and then distributed to four assistants (coders). The research team and group of coders held two discussion sessions wherein a codebook was developed following Creswell (Citation2013)’s approach. The codebook contained the definition for each of the categories and a list of terms associated with each category. The aim of the codebook is ensure the text are coded consistently among the coders. Examples of the terms are as follows:

In order to check for consistency, the Principal researcher gave the coders text1 to text50 and text19, 399 to text19, 449 of the dataset. Subsequently, the coders were asked to code the dataset based on the codebook given to them. After they have completed, the Principal researcher then tabled their coding into a spreadsheet to check for consistency. The number of agreements and disagreements among them were recorded to check for inter-coder reliability. This study adopted the formula used by McAlister et al. (Citation2017) to calculate the inter-coder reliability. Out of the 100 texts coded, 98 of the texts were coded consistently (agreement), giving an inter-coder reliability of 0.98. The high inter-coder reliability maybe due to the length of the text which is less than 280 characters, thus reducing ambiguity.

3. Results

Since 2014, there is increased attention on Halal cosmetics. Previously, the number of tweets about these products was relatively low, indicating a growing interest in halal cosmetics among users. The highest number of tweets measured was at the end of 2016. After further analysis, it was found that, within each year, the number of tweets was relatively higher at the end of the year (Figure ).

The next analysis conducted on the 19,449 tweets sought to determine the origin of the tweets (Figure ). Nevertheless, researchers found that a majority (83%) of the Tweeter users did not reveal their place of origin. From those users that revealed their location, the highest number of tweets were from Indonesia, followed by Malaysia and the United Kingdom. It must be noted that Figure only illustrates the top 10 countries with the highest number of tweets. Four of the countries, Indonesia, Malaysia, UAE, and Qatar, are Muslim countries, while the remaining six are non-Muslim countries.

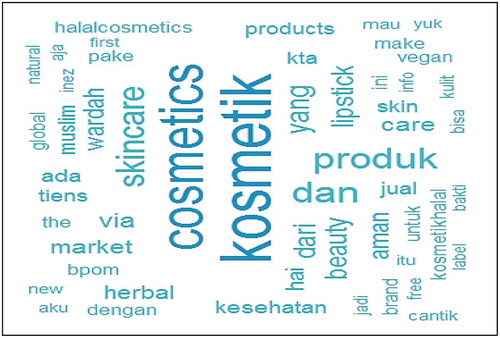

Based on the 19,449 tweets collected, the researchers created a word cloud to analyse the words used most frequently among users to help illustrate which words are more popular than others. This tool is a quick way of summarizing users’ tweet content. The larger the word size, the more frequently it is used (Figure ).

As can be seen in Figure , cosmetics and its equivalent word in Bahasa Malaysia language (kosmetik) are the most used words in tweets, followed by produk (“product” in English). Among the halal cosmetics brand observed in the word cloud are Wardah and Inez. The word cloud also revealed users’ interest in beauty, cantik (“beautiful” in English), and kesehatan (“health” in English). The word cloud also featured the word “product” with “skincare” and “lipstick.”

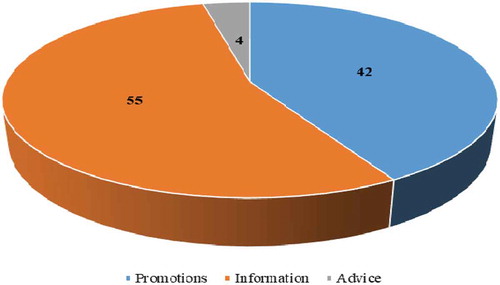

In addition to the word cloud, the researchers further analysed the text within the dataset in terms of their content (objective 1). As illustrated in Figure , 55% of the text provided information, 42% promoted a particular product/brand, and the remaining tweets provided advice.

The researcher conducted further analysis on text categorised as Information (10,618 tweets), finding that 50% of the tweets were merely chatters and not containing beneficial information, whereas the remaining 50% contained information in general, future or past events/services and products. Table contains some samples.

Table 1. Samples of Type of Information Text

The second most popular type of tweets were promotions of brands, products and retail outlets. Table illustrates a few samples. It was found that only 4% of the 19,449 tweets offered advice. Most of the advice was very general and unspecific in nature (Table ).

Table 2. Samples of text related to Promotions

Table 3. Samples of text related to giving advice

The study also examined the halal cosmetics brands/products that are most tweeted (second objective). The researchers found that the users tweeted approximately 700 different brands of cosmetic products in general. Table summarises the top 25 brands in the dataset. The researchers did not conduct further analysis to verify whether they were all halal cosmetic products.

Table 4. Top 25 cosmetics brand tweeted

4. Discussion

As stated before, the researchers observed the highest number of tweets at the end of 2016. They attributed this increase to several events related to halal cosmetics that were organised in 2016. One such event was the 3rd Cosmetics & Beauty Expo in Osong, Korea, held October 4–6, 2016, during which RACS (the UAE accredited Halal Certification Body) introduced Halal for Cosmetics to local Korean Cosmetic Businesses and consultants. The second event was the Beauty Expo 2016, held October 14–17 in Kuala Lumpur. During the event, the organisers, for the first time, dedicated a pavilion to halal and bumiputra-manufactured cosmetics and beauty products. The third event was In-Cosmetics Asia, held in Bangkok November 8–10, 2016, during which the focal point was on halal cosmetics. The findings also illustrate that, during each year, the number of tweets was relatively higher at the end of the year, which may be attributed to the fact that there are numerous end-of-the-year sales happening worldwide and that users tend to tweet as they hunt for bargains.

In terms of the geo-location of Twitter users (Figure ), the researchers noted that there is a large gap between Indonesia and the rest of the countries. This gap is due to the fact that Indonesia’s population is predominantly Muslim and more populated than other countries within this study, except the US. This finding can be used by international halal cosmetics companies as part of their future marketing strategy, in that, they should consider marketing their halal products in countries where the demand would be higher, such as Indonesia.

The researchers discovered that, within the word cloud and in Table , three brands were highly tweeted, i.e., Wardah, Inez, and Tiens, which respectively refer to Wardah Beauty Cosmetics, Inez Cosmetics, and Tiens. Indonesian based companies produce Wardah and Inez, both having obtained the halal certification from Indonesian Religious Council (Majlis Ulama Indonesia). It is not surprising that these two brands have the most tweets as a review of their website illustrated that they market their halal cosmetics diligently and establish their brands within the local market. Tiens, on the other hand, produced by Tiens Malaysia, is the first China multi-level marketing (MLM) company, which started business in Malaysia in 2002. The Tiens Group, founded in 1995 in Tianjin, China, received halal certification by JAKIM under TIENS Health Development (M) Sdn. Bhd.

The study also examined the halal cosmetics brands/products that are most tweeted (Table ). The researchers must note here that the top three brands were Wardah, Inez and Tiens, perhaps because the number of tweets with geo-location were from Indonesia and Malaysia. This finding also illustrated that local brands with halal certification had more tweets than international brands. International cosmetics companies should be willing to invest in halal certification if they want to sell halal cosmetics products to Muslim dominated countries such as Indonesia and Malaysia.

The word cloud also reveals users’ interest in beauty, having mentioned cantik (beautiful in English) and kesehatan (health in English). This illustrates Twitter users’ interest in halal cosmetic products because they want to use them to enhance their beauty, to look nice, and to further improve their health. As mentioned earlier, halal products are eco-friendly and do not contain harmful substances that are not good for users’ health.

The word cloud also featured the word “product,” together with “skincare” and “lipstick,” showing that most of the users focussed on these products, as these are daily essentials. “BPOM” was another word that had a higher number of tweets. BPOM stands for Badan Pengawas Obat dan Makanan (Indonesian national agency of drug and food control), which is a regulatory body governing the halal pharmaceutical and food market in Indonesia.

With reference to the first objective, i.e., to analyse the text and categorise them as information, promotions, or advice, the results illustrated that 55% of the tweets were providing information (Figure ). Nevertheless, approximately half were just chatters and did not contain any useful information. The researchers found this information, upon further analysis, to be private messages, as categorised by Sriram et al. (Citation2010). In addition, the researchers could categorize useful Information more specifically as general information or news and events, as stated by Zubiaga et al. (Citation2015) and Sriram et al. (Citation2010). The researchers classified other tweets as Promotions or Deals, as mentioned by Sriram et al. (Citation2010), and the least popular type of tweets as Advice or Opinion, as observed by Gupta (Citation2010) and Sriram et al. (Citation2010).

5. Conclusion

This study collected Tweets to obtain an understanding of what users post in relation to halal cosmetics. We extracted a total of 19,449 tweets. The study first focussed on the type of text in a tweet. We categorised the tweets’ text into three categories, informational, promotions, or advice. We found that a higher percentage of the tweets’ text were information based, which is consistent with Gupta (Citation2010). Further analysis indicated that a high percentage of this information is unuseful, which was similar to the findings by Sriram et al. (Citation2010). In sum, the types of tweets were similar to those found by Zubiaga et al. (Citation2015), Sriram et al. (Citation2010), and Gupta (Citation2010). Future research should incorporate a more systematic analysis using algorithms to analyse the tweeted texts to provide a more precise categorization of tweets.

Second, this study analysed the tweets in terms of cosmetics brands and products. It showed the brands most mentioned by users. This study illustrated that the top three brands were Wardah, Inez, and Tiens. A study by Yacob, Zainol, and Hussin (Citation2018) also found Wardah to be one of the most popular halal cosmetics brands among respondents in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand. Inez and Tiens, however, were unpopular. Lutfie, Puspa, Sharif, and Turipanam (Citation2015), in their paper focussed on Wardah, found it to be the most popular in the Indonesian market since 2012.

Future studies should focus on other elements of the tweets. In addition, besides identifying the brands tweeted, future analysis should include analysis on the brands country of origin, as this would illustrate whether halal cosmetics are produced by Muslim countries only. Future studies should seek to analyse the sentiment of the Tweets posted, which, for example, would allow a more in-depth investigation towards a particular halal cosmetics brand.

As with any other research, this research also has its limitation. The main limitation is the inability to capture Twitter tweets in languages other than English and Bahasa Malaysia, as there are many countries where these two languages are not used extensively. It would be interesting to see the tweets pertaining to Halal cosmetics from non-English and Bahasa Malaysia speaking countries, such as France, Germany, Turkey, etc. Future studies could develop algorithms that capture other languages.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Ministry of Education, Malaysia for funding this research under the Malaysian Higher Education Consortium of Halal Institutes as well as the University of Malaya for providing the facilities and infrastructure to conduct the research. Grant No: MO001-2018.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sulaiman Ainin

Ainin and Feizollah are attached to Universiti Malaya Halal Research Center (UMHRC) while Nor Badrul and Aniza are from the Faculty of Computer Science and Information Technology (FSKTM) and Firdaus is a PhD student in FSKTM. We have been conducting research on Halal Big Data: Text and Sentiment analysis, which is funded by the Ministry of Education Malaysia under the Malaysian Higher Education Halal Institute Consortium (KIHIM). The research grant focusses on three halal areas: cosmetics, tourism and food.

References

- Abbar, S., Mejova, Y., & Weber, I. (2015). You Tweet what you eat: Studying food consumption through Twitter. Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp.3197–12). Seoul, Republic of Korea.

- Ali, S., Halim, F., & Ahmad, N. (2016). Beauty premium and halal cosmetics industry. Journal of Marketing Management and Consumer Behaviour, 1(4), 52–63.

- Annabi, C. A., & Ibidapo-Obe, O. O. (2017). Halal certification organizations in the United Kingdom: An exploration of halal cosmetic certification. Journal of Islamic. Marketing, 8(1), 107–126. doi:10.1108/JIMA-06-2015-0045

- Aoun, I., & Tournois, L. (2015). Building holistic brands: An exploratory study of Halal cosmetics. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 6(1), 109–132. doi:10.1108/JIMA-05-2014-0035

- Archrekar, H., Gandhe, A., Lazarus, R., Yu, S. H., & Lie, B. (2011). Predicting flu trends using Twitter data. Computer communications workshops. Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE Conference (pp.702–707). Shanghai, China. doi:10.1109/INFCOMW.2011.5928903

- Bhatia, M., & Jain, A. (2013). Green marketing: A study of consumer perception and preferences in India. Electronic Green Journal, 1(36), 1–20.

- Briliana, V., & Mursito, N. (2017). Exploring antecedents and consequences of Indonesian Muslim youths’ attitude towards halal cosmetic products: A case study in Jakarta. Asia Pacific Management Review, 22(4), 176–184. doi:10.1016/j.apmrv.2017.07.012

- Cavazos-Rehg, P. A., Krauss, M. J., Sowles, S., Connolly, S., Rosas, C., Bharadwaj, M., & Bierut, L. J. (2016). A content analysis of depression-related Tweets. Computer Human Behaviour, 54, 351–357. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.08.023

- Cavazos-Rehg, P. A., Sowles, S. J., Krauss, M. J., Agbonavbare, V., Grucza, R., & Bierut, L. (2016). A content analysis of tweets about high-potency marijuana. Drug Alcohol Dependence, 166, 100–108. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.06.034

- Ceron, A., Curini, L., Iacus, S. M., & Porro, G. (2013). Every tweet counts? How sentiment analysis of social media can improve our knowledge of citizens’ political preferences with an application to Italy and France. New Media & Society, 16(2), 340–358. doi:10.1177/1461444813480466

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (Third Edit). Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

- Gupta, N. K. (2010). Extracting phrases describing problems with products and services from Twitter Message. Retrieved from http://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/cys/v17n2/v17n2a10.pdf

- Husain, R., Ghani, I. A., Mohammad, A., & Mehad, S. (2012). Current Practices among Halal Cosmetics Manufacturers in Malaysia. Journal of Statistical Modelling and Analytic, 3(1), 46–51.

- Jusoh, A., Kamarulzaman, L., & Zakaria, Z. (2016). The Implementation of halal cosmetic standard in Malaysia: A brief overview. In S. K. Manan, F. A. Rahman, & Sahri ( 1st Eds.), Contemporary issues and development in the global halal industry (pp.37-46). Singapore: Springer.

- Krauss, M. J., Sowles, S. J., Moreno, M., Zewdie, K., Grucza, R. A., Bierut, L. J., & Cavazos-Rehg, P. A. (2015). Hookah related Twitter chatter: A content analysis. Preventing Chronic Diseases, 12, E121. doi:10.5888/pcd12.150140

- Lutfie, H., Puspa, E. P. S., Sharif, O. O., & Turipanam, D. A., (2015, November). Which is more important? Halal label or product quality. 3rd International Seminar and Conference on Learning Organization. Yogyakarta, Indonesia: ISCLO.

- McAlister, A. M., Lee, D. M., Ehlert, K. M., Kajfez, R. L., Faber, C. J., & Kennedy, M. S. (2017). Qualitative Coding: An Approach to Assess Inter-Rater Reliability. doi:10.18260/1-2—28777

- Mohamed, R. N., & Li, Y. B. (2017). Interdependence between social value, emotional value, customer experience and customer satisfaction indicators: The case of halal cosmetics industry in Malaysia. Pertanika Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 25, 131–142. Retrieved from www.scopus.com

- Mohezar, S., Zailani, S., & Zainuddin, Z. (2016). Halal cosmetics adoption among young Muslim consumers in Malaysia: Religiosity concern. Global Journal Al-Thaqafah, 6(1), 47–59. doi:10.7187/GJAT10220160601

- Mostafa, M. M. (2018). Mining and mapping halal food consumers: A geo-located Twitter opinion polarity analysis. Journal of Food Products Marketing, 24(7), 858–879. doi:10.1080/10454446.2017.1418695

- Mostafa, M. M. (2019). Clustering halal food consumers: A Twitter sentiment analysis. International Journal of Market Research, 61(3), 320–337. doi:10.1177/1470785318771451

- Nguyen, T. T., Meng, H.-W., Sandeep, S., McCullough, M., Yu, W., Lau, Y., & Nguyen, Q. C. (2018). Twitter-derived measures of sentiment towards minorities (2015–2016) and associations with low birth weight and preterm birth in the United States. Computers in Human Behavior, 89, 308–315. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2018.08.010

- Oliveira, N., Cortez, P., & Areal, N. (2017). The impact of microblogging data for stock market prediction: Using Twitter to predict returns, volatility, trading volume and survey sentiment indices. Expert System Application, 73, 125–144. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2016.12.036

- Philander, K., & Zhong, Y. Y. (2016). Twitter sentiment analysis: Capturing sentiment from integrated resort tweets. International Journal Hospitality Management, 55, 16–24. doi:10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.02.001

- Shayaa, S., Jaafar, N. I., Bahri, S., Sulaiman, A., Wai, P. S., Chung, Y. W., … Al-Garadi, M. A. (2018). Sentiment analysis of big data: Methods, applications, and open challenges. IEEE Access, 6, 37807–37827. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2851311

- Sriram, B., Fuhry, D., Demir, E., Ferhatosmanoglu, H., & Demirbas, M. (2010). Short text classification in Twitter to improve information filtering. In Proceedings of the 33rd international ACM SIGIR conference on Research and development in information retrieval (pp. 841–842). Geneva Switzerland: ACM.

- Statista. (2018). Twitter Revenue and Usage Statistics. Retrieved from http://www.businessofapps.com/data/Twitter-statistics/

- Swidi, A., Wie, C., Hassan, M. G., Al-Hosam, A., & Mohd Kassim, A. W. (2010). The mainstream cosmetics industry in Malaysia and the emergence, growth and prospects of Halal cosmetics. Presentation at the Third International Conference on International Studies (ICIS 2010). Sintok, Kedah Darul Aman, Malaysia: Universiti Utara Malaysia.

- Technavio. (2018). Global Halal Cosmetics and Personal Care Market 2018–2022. Retrieved from https://www.reportbuyer.com/product/5589845/global-halal-cosmetics-and-personal-care-market-2018-2022.html/

- Tumasjan, A., Sprenger, T. O., Sandner, P. G., & Welpe, I. M. (2010). Predicting elections with Twitter: What 140 characters reveal about political sentiment. Proceedings of the Fourth International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media (pp. 178–185). Munich, Germany: Technische Universität München. doi:10.1016/j.jmbbm.2009.08.003

- Yacob, S., Zainol, R., & Hussin, H. (2018). Local branding strategies in Southeast Asian Islamic cultures. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 23(1), 102–131. doi:10.22452/jati

- Yu, Y., & Wang, X. (2015). World cup 2014 in the Twitter world: A big data analysis of sentiments in US sports fans’ tweets. Computer Human Behaviour, 48, 392–400. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.01.07

- Zubiaga, A., Spina, D., Martınez, R., & Fresno, V. (2015). Real-time classification of Twitter Trends. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 66(3), 462–473. doi:10.1002/asi.2015.66.issue-3