Abstract

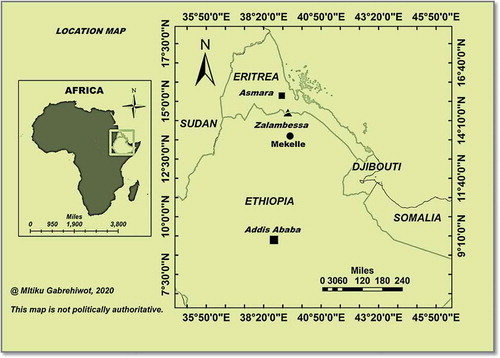

This article is based on an eyewitness and firsthand information on the opening of Eritrea and Ethiopian border on 11 September 2018. From photographs, interviews, and observation in the towns of Senafe (Eritrea) and Zalambessa (Ethiopia), the authors intend to capture grassroots political statement and reflect retrospectively on the Ethio-Eritrean peace deal. The main objective is to capture grassroots political impression and implication of the peace agreement and contribute to the anthropology of borders. Withstanding the challenge of studying borderlands within the lens of anthropology that calls for a methodological shift towards, “authority, identity, and power” dimensions in borderland studies, this article aims to contribute to the study of border and borderlands vis-à-vis local, state, and international actors. In a world where state and international negotiators are active in border dispute resolution, understanding local views and actions is crucial. The authors found that the Ethio-Eritrean peace agreement did not sufficiently consider local voices and initiatives which is crucial for a sustainable peace in the region. Considering these findings, the authors encourage further research on inter-state peacemaking and the role of local voices.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This article discusses the peace deal reached between Ethiopia and Eritrea in July 2018 and the following inter-state diplomacy followed by the opening of the border on 11 September 2018. The research addresses events leading to the peace agreement with a summary of local and international actors’ roles and demands during the process and alternative views from the local people who had lived side by side for centuries.

1. The Ethio-Eritrean border in context

Borderlands and border studies are crucial themes in Anthropology. Globally, the focus of border studies has been on a few recurring geopolitically sensitive borders such as the US–Mexico border (Donnan, Citation2015, p. 761). In recent years, interests in understanding other less familiar borders are on the rise (Donnan, Citation2015: 763), with local views and narratives being addressed (Schlee, Citation2003; Wilson, Citation2012, p. 200). A shift from the macro-level studies to a micro setting inspires current border and borderland research (Kurki, Citation2014, p. 1067; Newman, Citation2003). Emphasizing on the above statement, Donnan writes, “Understanding … borders thus requires local Ethnographic knowledge, and not just the knowledge of state-level institutions and international relations, a fine-tune sensitivity that is alert to cultural meaning and practice …“ (Donnan, Citation2015, p. 761).

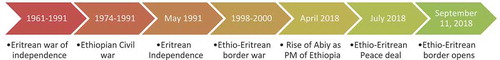

Unlike other regions, borderland studies in the Horn of Africa follow conflicts and wars. Research in the Horn of Africa within the spirit of inter-state actors and borderlands is scanty (Feyissa & Hoehne, Citation2008). In Ethiopia, few studies concentrate on the ethnic and cultural variables and how language, history, and migration shape inter-state politics and borderline conflicts (Abbay, Citation1997; Abbink, Citation2001; Puddu, Citation2017). This pattern of addressing borderland communities is short of micro-level arguments (Schlee, Citation2003). The Ethio-Eritrean border is usually discussed only from macro-level perspectives. With this spirit, this article focuses on the Ethio-Eritrean border agreement and attempts to capture local voices. The arguments are meant to be understood in the context of the recent Ethio-Eritrean peace agreement and events before (see Figure ).

In May 1991, Eritrea won its independence from Ethiopia.Footnote1 Eritreans fought a bitter war from 1961 to 1991 for their independence. Not only Eritreas but also other Ethnic groups in Ethiopia, particularly the Tigrayans, fought for better political representation and Ethnic federalism in the country. This led to what is called the Ethiopian civil war fought from 1974 to 1991. This brought the demise of the socialist regime called Derge that ruled Ethiopia from 1974 to 1991. Following the end of the civil war, Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF), now People’s Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ), and Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF)Footnote2 spearheaded by Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) were in charge of Eritrea and Ethiopia, respectively. To the surprise of many but a few (Abbink, Citation1998, p. 552; Iyob, Citation2000; Reid, Citation2003, pp. 374–381), Eritrea and Ethiopia went to war over a border dispute in May 1998.

From May 1998 to June 2000, Eritrea and Ethiopia fought one of the deadliest wars in recent African history. Both countries ignored the warnings from the international community and the State Department (Clinton, Citation1999), and the war had a devastating impact on the lives, economy, and psychology of the people on both sides. The Ethio-Eritrean border war resulted in 50 000 causalities on each side and it became the top inter-state conflict in the world by 2000 (Seybolt, Citation2002, p. 29). United Nations imposed sanctions on Eritrea in December 2009 for its alleged support for Islamist militants in Somalia (BBC, Citation2018b). Besides, Eritrea was also criticized for a grave human rights abuse and the never-ending suffering the compulsory national serviceFootnote3 brought to the youth (Belloni, Citation2019b). For Eritrea, the UN sanction and its isolation from the international arena were caused by the USA’s international policy on the countryFootnote4 and Ethiopia’s comparative diplomatic strength.

The border was closed for nearly 20 years with roads, airways, telecommunication, and movement of people from one country to the other totally blocked. The total economic cost of the war was huge with an estimate reaching 1 billion USD (Mulugeta, Citation2011, p. 45). The social, cultural, and political impact of the war has been devastating both countries. The people living on the border of the two countries were affected the most. Many of the farmers on both sides were not able to sustain a peaceful life for nearly 20 years due to the continued tension (M. Woldemariam, Citation2018). Most importantly, the Ethnic Tigrayans, Kunama, Afar, and Irob on both sides of the border had been cut off from each other for nearly 20 years (Abbink, Citation2001). However, these people were able to covertly maintain minimum social and cultural ties.Footnote5

The Tigrayans, who settled in the central area, the Kunama on the northwestern side and the Irob and Afar peoples on the eastern and northeastern side, respectively, were directly affected (Jon Abbink, Citation2001, p. 451). The Tigrayans of Ethiopia are directly related to the Tigrinya-speaking people in central highland Eritrea with strong cultural connection and family ties (Abbink, Citation2001). The Kunama of Eritrea were also able to maintain ties with their fellow Kunama people in Western Tigray while the Irob and Afar crossed the border to Eritrea for social, cultural, and economic reasons. The war was not expected and the people were taken by surprise. Given their relative vulnerable geopolitical and cultural positions following the war (Abbink, Citation2001: 450), the psycho-social impact of the war on the peoples of Irob, Kunama, and Afar was high. Yet, despite the existence of a full-fledged war between Eritrea and Ethiopia, these people maintained close social and cultural ties with their respective ethnic groups across the border.

This proved the enduring demand of the people on the border for normalization. However, sandwiched between the political elites in the two countries (Steves, Citation2003), their demands have not been fully expressed. In the following sections, the authors shall narrate events as they unfold and pose a critical question on the sustainability of the peace. When the peace agreement was announced, many ardently wrote about the prospects and breakthrough. Interestingly, little is said about the local initiatives and grassroots political narratives and debates on the nature and consequences of the agreement. In the eyes of the locals, the Ethio-Eritrean peace agreement is therefore not a mere breakthrough in peace as is claimed by the international community, but an imposed implementation of the UN agreement of 2002. Interestingly, there are competing voices and narratives whose range and sources are regional, national, and international.

2. Crushing the “border”: crashing a “party”

Following the peace deal between Eritrea and Ethiopia in July 2018, the conflict between the two countries officially ended. On 11 September 2018, (Ethiopian New year), a “party” was thrown for the armed forces from the two countries at Zalambessa,Footnote6,Footnote7 The two leaders along with high-ranking military officers walked from the Eritrean side and “crosswalked” the border. This heralded the opening of the border. About 2 hours after the gathering of the officials and high-ranking military personnel, the bystanders watching from the two sides of the border took the first move.

Within minutes, the people from the side of Eritrea, who were carefully observing the “party” from a distance of about 500 m, crossed the border in hundreds. Instantly, the people from the side of Ethiopia left the “party” to welcome the Eritreans. The people were no longer in a position to be dictated and had to cross the border and be part of a “party” they had been waiting for so long. The leaders celebrated the event in the border, Ethiopians (mostly ethnic Tigrayans) travelled as far as Asmara via land while Eritreans drove as far as Mekelle (160 km away from the border) on the same day the border was opened.

The primary author who witnessed this historically significant event watched the people from both sides join halfway between the Eritrean and Ethiopian border. While the soldiers of the two countries were not armed, they were in their uniforms guarding the border. It was fascinating to watch how the Eritrean soldiers reacted to the crowd gathering on the Eritrean side. It was beyond their control and imagination and had to let them go. As the armies from the two countries entertained themselves with music and food, the civilians crushed the border.

Within few minutes of the collapse of the border, President Isaias Afwerki and Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed had to leave the party. What makes the event so unprecedented was that it brought the “political border” open to the general public, which was an unintended consequence. Unlike the Berlin wall, the Zalambessa wall was meant to be a show of politicians and the army, as they dine during the Ethiopian New Year. In line with the above statement, Lyammouri (Citation2019, p. 3) writes, “with the openings centered around important local holidays, they appeared designed with public relations in mind more than anything, underpinning a lack of technical preparations.” Events leading to and after the opening of the border and regulations of the border seem to confirm the above statement.

The news of the opening of the border received huge coverage by local and international media outlets (Africa News, Citation2019a; BBC, Citation2018a, Citation2018b; France 24, Citation2018; Washington Post, Citation2018). However, the mass-driven, people-to-people interaction on the day and following the opening of the border received little attention. As anthropologists interested in political anthropology and borderland research, it was a golden opportunity to capture this historically significant event. The implication of the event is far-reaching, touching historical, cultural, social, and political and international relations. With this note, the authors shall present the implication of the peace agreement and its contribution to the future state-to-state and peoples-to-peoples diplomacy.

3. Implications

3.1. Thinking beyond a border

The Ethio-Eritrean border is not a “border”, a mere geopolitical border. Many of the borderland people are culturally, socially and economically interdependent (Jon Abbink, Citation2001, pp. 450–451). The Ethio-Eritrean border was a subject of political manipulation and elite’s political game since 1882 (Abbay, Citation1997; Mesghenna, Citation1989; Reid, Citation2003, Citation2007) and was followed by the historical narratives (Smidt, Citation2012). Long before the conflict, the peoples along the border, despite minor differences in administration particularly due to Eritrean colonial legacy (Schlee, Citation2003, p. 346), shared much of the cultural and social fabric.

However, since the early 1960s with the rise of popular resistance against Haile Selassie, many Ethnic-based political parties emerged (Abbink, Citation2001, p. 455). The Eritrean People’s Liberation Front and Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front are good examples. Over time, these and other regional forcesFootnote8 had created political elites and maximized their political, social, and economic superiority (Reid, Citation2005, p. 485). Concerning this Abbink writes, “… in both regimes … their leading elites are still undemocratic and perhaps and also sectarian: acting on behalf not of the nation but for their own, limited, constituency” (Citation2001, p. 448).

The thesis of this article is therefore that the Ethio-Eritrean border should not be understood as a mere political border, but also as a socio-cultural entity (Newman, Citation2003), created over centuries of social capital. The root cause of the war was neither territorial (Abbink, Citation2001, p. 448), nor cultural nor social but political (Lyons, Citation2009) and economical (House, Citation1999). For many, the war was a result of a rivalry between two political elites of the Ethnic Tigrayans in both countries (Lata, Citation2003, pp. 372–375). The only differences between Ethnic Tigrayans in Ethiopia and Eritrea would be psychological (Schlee, Citation2003; Smidt, Citation2012; Trivelli, Citation1998, p. 265), created over the past century and cemented during Italian colonial presence in Eritrea (1890–1947) and reinforced during the following decades. On top of the historical ingredients, Eritreans and Ethiopians, Tigrayans, in particular, were in a state of competing mode (Steves, Citation2003).

This was further strengthened by the internal differences and faction between EPLF and TPLF. Since the 1980s when TPLF demonstrated its capability as a full-fledged liberation front in Tigray, the difference between the two parties increased. This was not liked by EPLF which had a political, ideological, and territorial claim from Tigray (Young, Citation1996). Understandably, this sub-servant, sub-friendship status of the two liberation fronts was maintained until the defeat of Derge, a military junta. It was a common enemy of EPLF and TPLF (Reid, Citation2003, p. 381). However, it was clear that these “friends” in the battle against a common enemy would not get along once the enemy was gone (Abbink, Citation2003).

In 1991, Eritrea got its independence and was motivated to dictate terms of engagement with Ethiopia, now under TPLF’s watch. The free movement of goods and services between Ethiopia and Eritrea was seen as a comparative advantage for Eritrea. The introduction of Eritrean currency Nakfa in 1997 made things worse as Ethiopia, for obvious reason, didn’t like the idea (House, Citation1999). Eritrea encouraged the free circulation of both Birr and Nakfa in both countries. This was unacceptable for Ethiopia, which responded by introducing a new bill. This bold move of Ethiopia is said to have cost Eritrea nearly all of its cash deposit. In addition, according to Lata, the growing economic and political influence of Tigrayan elites in Ethiopia was seen as a serious concern for Eritrean elites (Lata, Citation2003, p. 378).

What is then the primary motive for the opening of the border by the two governments, while TPLF was skeptical of the move? With the rise of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed in April 2018 into Ethiopia’s top job, the political landscape of the country changed dramatically (BBC, Citation2019a). During his early carrier, groomed and cherished by TPLF, Revolutionary Democracy, Abiy Ahmed’s political ideology U-Turn (Gebregziabher, Citation2019) seems to come from his personal “aspiration”. The notion of to unify Ethiopia came neither with parliamentary procedure nor from EPRDF’s tradition. In many parameters, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s sudden call for peace was unexpected (Hirt & Abdulkader, Citation2018, p. 30). His call for unity of all Ethiopians under “one” Ethiopia seems to have met resistance from the ethnic minorities in the country which valued Ethnic federalism (Fisher & Gebrewahd, Citation2018). His call for unity under vague political and ideological vacuums seems to fall short of his initial promises and people’s expectations.

What is interesting is the political leadership in Eritrea remained at a standstill. The leadership change in Ethiopia was a victory for Isaias Afwerki who was heard saying “game over” for TPLF.Footnote9 On the Ethiopian side, the influence of TPLF was now contained in Tigray with most of its powerful actors in Ethiopia’s political, economic, and military apparatus being demoted or retired. The symbolic significance of the event to both leaders (Hirt & Abdulkader, Citation2018, p. 31), especially to Isaias Afwerki, was crucial (Lyammouri, Citation2019, p. 5). One can claim that this was yet again a quest for the monopoly of the political landscape (new and old). The “party” at the border was meant to appease soldiers while Isaias Afwerki and Abiy Ahmed gain local, national, and international admirationFootnote10 for ending the conflict.

The unapologetic political move by the two leaders had angered TPLFFootnote11 which stated that if the two countries were going to accept the peace deal, grass-root voices must be included in the dialogue.Footnote12 The agreement between Abiy and Isaias in the United Arab Emirates and later in Asmara was not made public. This had created legitimate questions not only on the process of the peace but also on the result and its sustainability (Africa News, Citation2019b; Ezega News, Citation2019; VOA, Citation2019). For Bereketeab (Citation2017), the ball was on the side of Ethiopia which refused to implement the UN agreement of 2002. On a purely international law standpoint, there are merits to this argument. The above author blames not Ethiopia but the international community for not enforcing the agreement. This is also evident from the post-2002 business between the two countries. Eritrea was so frustrated with the international community that it had limited the role of the United Nations Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea (UNMEE) in the border (Lyons, Citation2009, p. 169).

At the local level, the opening of the border was welcomed, but with anger and resentments towards the politicians of the past and present. The previous leaders were responsible for blindly driving the two brotherly people into one of the deadliest war in modern African history while the present leadership is blamed for ignoring alternative voices. On 11 September 2018, an old Eritrean man who had crossed the border to visit his family said, “Today is our day; today is not ‘their’ day.” The assumption by the political elites of the past (Schlee, Citation2003, p. 357) and present in both countries seems to ignore the inherent socio-cultural and economic integration of the people. For the people of the two countries, the war shouldn’t have had happened. On 11 September 2018, the people were able to speak boldly that the war, the border, and differences were created by the politicians to maximize their interest. A woman says, “It is natural for the one who closed the door to open it,”Footnote13 assuming that it was a political drama that brought the closure of the border and the border must be opened in the same way, holding those in power responsible.

From a diplomatic and geopolitical stance, the exclusion of TPLF is legitimate as TPLF rules Tigray but not Ethiopia. For this reason, Abiy’s move gained much support in parts of Ethiopia and outside of Ethiopia (Hirt & Abdulkader, Citation2018, p. 31). The exception to this was the people who live across the border between Eritrea and Ethiopia, the Tigrayans on both sides of the borders (Hirt & Abdulkader, Citation2018). In the eyes of Ethnic Tigrayans in particular, the presence of other regional presidentsFootnote14 in the negotiation process made the whole drama doubtful. In the eyes of nationalist Tigrayans, this move was a red light given the potential territorial dispute with the regional state of Amahara (International Crisis Group, Citation2019) on the western side and the psychological war between the leadership in Asmara versus TPLF. This resulted in the rallying of the majority of Ethnic Tigrayans on the side of TPLF. Abiy, by miscalculating that he would gain political advantage both from Eritrean (Bruton, Citation2018) and Ethiopian side, made TPLF stronger at its base.

This warrants a close look at the internal (within EPRDF) and external (TPLF versus EPLF), power struggles. The Tigray People’s Liberation Front is in charge of the regional federal government of Tigray, a region that shares over 500 km of border with Eritrea. Current assessmentFootnote15 in the region shows that TPLF is gaining more strength in Tigray. The peace deal with Eritrea without TPLF’s involvement is very hard if not impossible (VOA, Citation2019). The border which was again abruptly closed on December 2018 remained closed to the very day this article was submitted. Wilson (Citation2012, p. 201) writes, “regions and states often compete with their states, thereby calling into question the roles which borders serve.” If one brings the cultural and historical similarity of the people on both sides of the border, and peace deal becomes quite complex and multivariable. It is with this spirit that the authors reposition the argument on Ethio-Eritrean border conflict from within. That is because, “… social scientists cannot fully grasp the operation of power without recognizing how territory and territoriality frame social and political identity, identification, integration, and differentiation, particularly as they relate to conflict” (Wilson, Citation2012: 202).

Figure 4. Eritrean women representing different religions enter Zalambessa, by Mitiku Gabrehiwot, 11 September 2018

A counter-argument is that Abiy refrained from inviting TPLF since the later was at the core of the conflict and is still a powerful actor in the region (Africa News, Citation2019b). For the Eritrean elites and Isaias, the damage caused by the TPLF-led campaign during the conflict was not expected and was quite humiliating. Comparing the Amhara-Showan-led campaigns against Eritrea with Tigrayan-led ones, Reid writes, “… perhaps, destruction of this kind (1998–2000) is ‘acceptable’ inflicted by a distant, Amhara-dominated regime in Addis [but] becomes wholly ‘unacceptable’ when it comes from neighboring Tigray. It is the identification of Tigray [with the] 1998–2000 war, therefore, which is paramount” (Reid, Citation2003, p. 379). A retired TPLF official claims that “Abiy, as an insider to EPRDF, he is well aware of the internal factions within TPLF and between TPLF and EPLF”.Footnote16 This also put Abiy Ahmed in a competitive position and helped him balance the power of TPLF by appeasing Isaias. The hasty peace deal therefore satisfies both Isaias’s and Abiy’s motives while it angers TPLF.

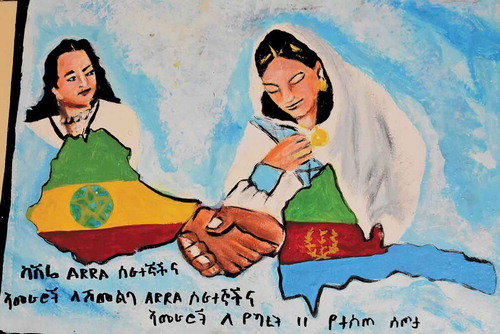

To the peoples of Eritrea and Tigray, the agreement seems to have brought divided views. On the Eritrean government side, the agreement had far-reaching significance. In principle, it won the territorial demand as per the 2000 Algiers border agreement as well as the 2002 ruling by the UN boundary commission, which Ethiopia refrained from implementation. Secondly and by far the most important one is psychological satisfaction on the side of Isaias Afwerki as this would bring him closer to his people and by implication, would bring a diplomatic triumph against Ethiopia in general and against TPLF in particular. A motto on one of the buses (Figure ) from Eritrea photographed on 11 September 2018 at the border is read, “The stick of truth may go thinner, but never breaks.” The metaphorical meaning of the motto is a reflection of the Eritrea’s inflated image of self (Schlee, Citation2003, p. 346), loaded with an ideological, psychological and political message. According to the Eritrean informant who was responsible for organizing the trip to Zalambessa (see Figure and ), the women were gathered from different offices and are from different religious groups. This group was carefully organized by the local militia and cadres in neighboring Eritrean villages.

On the Tigrayan side, the Eritrean national question is unfinished business (Johnson & Johnson, Citation1981; Reid, Citation2001, Citation2003, Citation2005). On the other hand, the peace deal was considered a gain for Isaias Afwerki and therefore ideological victory against the TPLF and other international actors.Footnote17 The motto mentioned in the above paragraph reveals the conflicting values and dreams of the peoples of Eritrea and Ethiopia in general and that of the Tigrinya-speaking peoples of the two countries in particular. The existence of similar cultural traits is not a guarantee for less conflict (Schlee, Citation2003, p. 365), Somalia being a classic example. It is therefore understandable that, despite a range of similarities in their inherent social evolution, Eritrea and Tigray differ in their social psychology. For the curious observer, the conflict was not merely political but also psychological (Jon Abbink, Citation2001, p. 449), brewed for the past six decades.

Figure 5. A bus returning to Eritrea, by Mitiku Gabrehiwot, 11 September 2018, in Eritrea on the Ethio-Eritrean border

Internationally, the event had legitimized the leaders of both countries as “peace” loving and “friends”. For example, Lyammouri (Citation2019: 6) writes, “the Ethiopia-Eritrea border is taking on a new meaning once again—both as a clear symbol of peace in the emerging friendship between the historically allied nations … .” What the above author seems to misunderstand is the true symbolic meaning of the opening of the border and who was a friend of whom. Here is where local realities and historical and cultural variables come to play (Feyissa & Hoehne, Citation2008). The Ethnic Tigrayans in Eritrea occupying the central plateau are an extension of the Tigrinya-speaking people of northern Ethiopia (Johnson & Johnson, Citation1981, p. 182). The historical, cultural, and social interdependence is negated from the current analysis of the situation. Once again, to the surprise of many,Footnote18 the states ignored local initiatives and imposed terms of the agreement on the people. In reality, it is the border people who are culturally and socially alike, and historically, it is TPLF and EPLF which became friends or foes. It is in the spirit of these realities and the political changes following the rise of Abiy Ahmed in Ethiopia that the border needs to be understood.

A few months before the opening of the inland route to Eritrea, many Ethiopian artists and politicians flew to Asmera. In local media, politicians, activists, and artists were seen excessively “romanticizing” Eritrea. This was so irresponsible of the governments on both sides that it had become so political. A teacher in Mekelle questions the motives and intentions of such propaganda, “what has happened then, that, all of a sudden Eritrea, the country Ethiopia and Ethiopians ridiculed for nearly 50 years, is now being romanticized to the level of stupidity unless it serves to dehumanize Tigray in general and TPLF in particular?”Footnote19 Since the 1960s (Reid, Citation2001, p. 262, Citation2005, p. 483) to the early 1990s, Eritreans were rejected from exercising their cultural and political rights (Gilkes, Citation1991; Lefebvre, Citation2012, p. 118). This was the very reason that brought the Ethiopian civil war of 1974–1991.

3.2. State actors versus local demands: diverging views

In contemporary border study, little is known about African borders and reasons of the current African frontier politics (Donnan, Citation2015, p. 760). Colonial narratives (Bayeh, Citation2015) seem to dictate borderland and frontier studies in Africa. According to Abbink (Citation2001, p. 448), despite the introduction of geographically defined sates in the Horn of Africa, crucial issues such as multi-ethnicities and multi-cultures and their impact on border studies are not well articulated. This resulted in the low level of attention given to local actors (social, cultural, and economic interdependence) in border studies (Wilson, Citation2012, p. 201). Of the territorial, social, and cultural borders, after Kurki (Citation2014) and (Donnan, Citation2015, p. 760), territorial analysis is given the upper hand. The “territorial” element of the Ethio-Eritrean border was a political creation following the independence of Eritrea. The “territorial” border was solidified following the Ethio-Eritrean war which further complicated the matter. For the past 27 years, these issues had become so international (Jon Abbink, Citation2001, p. 449) that international and state actors (Donnan, Citation2015, p. 762) were given more voices at the expense of local arguments. An opportunity to uncover the cultural and social border has been missing from the equation.

Events leading to the peace-deal show a rare political showdown and inter-government agreements and discussions. As soon as Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed was sworn-in as Ethiopia’s prime minister on 2 April 2018, there were talks of normalization with Eritrea. This was followed by a meeting between Eritrea’s Isaias Afwerki and acting US Assistant Secretary of State for Africa Affairs, Ambassador Donald Yamamoto on 24 April (The Economist, Citation2018). On 21 June, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres and African Union (AU) chief Moussa Faki Mahamat appreciated the process while the US welcomed the initiative of the two countries.

It was clear that America’s involvement in Ethiopia’s future political structure had become rampant. Much of the US’s interests are synchronized with the tension in the Horn of Africa and global actors (US, China, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, and European Union) with geopolitical, economic and military interest at stake (Taddele Maru, Citation2019). Tsegay (Citation2017, p. 4), who is critical of US’s policy on Ethiopia, writes, “USA’s main … strategy … is always keeping Ethiopia at cross-road position. United States is ideologically at loggerheads with Ethiopia’s democratic-developmental state ideology.” Besides, despite Ethiopia’s miraculous economic progress founded on the “developmental” state political economy, it had not been welcomed by the West spearheaded by the United States (Clapham, Citation2018). Naturally, the United States’ interest in the Horn of Africa is better served in a stable Ethiopia. However, the US’s unstable tactical and strategic interests in the region and beyond since Trump’s presidency may overshadow its partnership with Ethiopia.

Power holders and brokers in Ethiopia and the general public seem to be mindful of the above scenario. This had sent a clear message to the local people living on both sides of the border that once again national and international political motives (Reid, Citation2005, p. 485) and interests will dictate the peace process. The biggest worry was that there will be no due regard given to the reality on the ground. Commenting on the damage of the Ethio-Eritrean civil war and the local people options, Abbink writes, “… for the local people it will probably be a missed opportunity: they will not be involved in the process and some will not be given a chance to choose where to belong” (Reid, Citation2001, p. 456).

The leadership in Eritrea must have been overwhelmed with the territorial, diplomatic, and psychological victory against its rival; Isaias, however, couldn’t see the long-term consequence of the opening of the border. The opening of the border was appreciated internationally but left more questions than answers. Immediately after the acceptance of the 2002 UN boundary commission by Ethiopia in 2018, Ethiopians living in the disputed areas (Badema and its environs) held a peaceful demonstration against the movement of the Ethiopian government and called for peoples-to-peoples diplomacy first. Six days later on 17 June, Ethiopians in the northern Tigray region protested against the decision of the government.

Given the political and “symbolic” nature of the opening of the border, with little or no lasting impact on the average citizens (Lyammouri, Citation2019), the possible political and human rights questions in Ethiopia and Eritrea remained the same (Reuters, Citation2019) if not worsened (Gardner, Citation2018). This is particularly true with Eritrea where most youths left their country for fear of compulsory national services and lack of future in their country (Hirt & Abdulkader, Citation2018, p. 31). When the UN lifted the sanction on Eritrea in 2018, (BBC, Citation2018b; Morello, Citation2018) little or no proof was produced towards easing the suffering of young people in the country. Paradoxically as it seems but logically given the situation of the conditions in Eritrea and Eritreans’ state of mind (Belloni, Citation2019a), within 3 months of the opening of the border, about 24,000 people left the country for Ethiopia (Lyammouri, Citation2019, p. 4). Surprisingly, the peace deal seems to have brought unintended consequence, an influx of Eritrean Refugees into Ethiopia (Gardner, Citation2018; Jeffrey, Citation2018; Jeffrey & Belloni, Citation2019; The Economist, Citation2019).

For the older generation Eritreans and Ethiopians, the opening of the border was welcomed. This was particularly true with the Ethnic Tigrayans on both sides of the border who blame historical incidents (Abbink, Citation2001, p. 456; Johnson & Johnson, Citation1981) for the separation of the brotherly peoples. A man who crossed the border on a horse on the day the border was opened explains his feelings. The primary author met him outside his brothers’ house in Zalambessa.

First, let me make it clear for you. Who are Tigrigna? It is Eritrea and Tigray combined. We speak the same language and we look alike. We take brides from here (Tigray); you take bridegroom from there (Eritrea). We know each other and understand each other’s tongue (language) very much. Not those who are above (Northern Eritrea) and below (the rest of Ethiopia except Tigray); but we are the Tigrigna. Today, we are drunk in happiness and fainted in love. Whatever was lost, is lost for forever; like a strong foundation of a house, we are ready to leave a solid foundation for our own children. Let us build our future, a solid foundation. It is mandatory and necessary to leave peace for children. From all the people (in Eritrea and Ethiopia) we are the closest; we are the Tigrigna. We have spent 20 years apart … (Pause), I couldn’t see my brother’s sons; my brother couldn’t meet my children either. We shall leave the pain of the past behind and March into the future. I see a light; I see a hope …. Footnote20

On the side of the younger generation of Ethnic Tigrayans on both sides but Eritrea in particular, the cultural, historical, and ethnic connection between the Tigrayans of Ethiopia and Eritrea is less attractive. The continuous propaganda and political developments in both countries (Schlee, Citation2003, p. 357) had distanced the ethnic Tigrayans apart. In recognition of the above statement, Abbay writes, “The bonds of sentiment which naturally bind the Tigres [Tigrayans] of Ethiopia and Eritrea affected the younger generation in Eritrea in a way which must be expected in these days when the principles of self-determination are popular throughout the democratic world” (Abbay, Citation1997, p. 327).

Peace is good, but not enough. As Hirt & Abdulkader (Citation2018, p. 33) puts, “… it will be up to the people inside Eritrea to face the challenges of peace, … and the international community has welcomed the end of hostilities but has not come forward with any suggestions to help Eritrea to demilitarize and to democratize.” This has been what TPLF, the people living in the borders (Irob, Tigrayans, Kunama, and Afars) have been arguing for. Whether the peace deal was far-fetched, the “party” was only thrown to appease the international community and damage TPLF, or it was indeed a genuine gesture of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed for peace as it is often portrayed by the international community, remains to be seen.

For the Eritreans living in exile, the peace deal means a sudden change of status.Footnote21 One can imagine the implication of half-backed diplomacy and unsustainable peace deal to the legitimate Eritrean refugees (Jeffrey, Citation2018; Roussi, Citation2018; UN High Commissioner for Refugees, Citation2019). A few days toward the end of the preparation of this manuscript, Abiy Ahmed won the Nobel Peace Prize (BBC, Citation2019b), which was welcomed by many but also was met with credible doubts (Bruton, Citation2019). For now, what remains to be seen is whether the current political and ideological showdown subside and prove the international community that the peace deal is worth its “picture and prize” or complicates matters even more. As to the EPRDF, Kietil Tronvoll captured it well in a tweet citing a local media on Debretsion’s final words on EPRDF’s future and the Prosperity Party, “this is what we call betrayal, they (PM Abiy and his team) didn’t only betray us, they have betrayed their people, the poor people, they betrayed the country and we consider them traitors.”Footnote22

4. Conclusion

By any measure, the peace deal between Ethiopia and Eritrea is welcomed, and Prime Minister Abiy should be recognized for it. However, provoked by an obsessive quest for a short-cut to peace, just as the war was not expected (Reid, Citation2003, pp. 374–375), are we making the same assumption (ignoring the possible historical, cultural, and political causes) and consequences of the war? Perhaps, the right question could be to ask what possible motives were behind the rushed peace. Evidence from literature, interviews, and observation in nearby towns suggest that there are local, regional, and international actors involved with conflicting views. The fracture of EPRDF into reformist (Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed and his team) and conservatives (TPLF and people living in the border) represents the two blocks deserving attentions. Unlike (Gebregziabher, Citation2019), who attributed the current political stand-off in Ethiopia to ideological differences, it is driven by less of political ideology but more of a personality cult and internal faction within EPRDF. For Eritrea, the peace deal seems to have brought victory: one in retaliating its wartime companion-turned-mortal enemy (TPLF) and elevated Isaias’s international image and the implementation of the border commission decision of 2002. Globally, the United States supported by the UN and the Gulf States (Saudi Arabia and UAE) seems to have contributed to the initiative. However, how the international actors will contribute to the badly needed normalization process between the two countries still remains unclear. On a different note, the voices of the local peoples (Eritrea and Ethiopia) who advocated for people-to-people diplomacy (Woldemariam, Citation2019) seem not to have been sufficiently considered. The argument that the people were not part of the problem and yet are not part of the solution is worth exploring. In dealing with issues such as the case of Ethio-Eritrea border, it is crucial to listen to local narratives about the past, present and future connections and interdependence of the peoples who are most affected.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mitiku Gabrehiwot Tesfaye

Mitiku Gabrehiwot Tesfaye is an Associate Professor of social anthropology at Mekelle University with research interest on displacement, migration, the minorities, legal anthropology and cultural identity. His current project focuses on political anthropology with a focus on Ethiopian local and regional parliaments, and local voices and representations.

Mahlet Alemu Gebrehiwot

Mahlet Alemu Gebrehiwotis a development anthropologist interested in migration, returnees, gender and inclusive policies and development intervention schemes. Currently, she is working on youth and their role in health promotion and livelihood diversification in Tigray.

Notes

1. Result of the Eritrean Independence referendum was declared on the 27 April 1993.

2. On 14 November 2019 with the foundation of a Pan-Ethiopian Party (Ethiopian Prosperity Party), EPRDF, ceased to exist; the legality of the process is still disputed. More discussion on EPRDF and its future is presented in the last section of the article.

3. Originally, the national service lasted for 18 months. In 2002, following the renewed conflict with Ethiopia, the national service was turned into a lifetime.

4. The United States of America had a strong strategic interest in the Horn of Africa. This strategic interest was dependent on Ethiopia’s role in the war on terror, a priority for America’s policy on the Horn of Africa. Such partnership reached its climax during the Clinton and Obama administrations when US Special Forces had access to Ethiopian military bases in the East and South of the country.

5. Interview, a 65-year-old man, Zalambessa, 11 September 2019.

6. A border town in Ethiopia. Zalambessa was heavily bombed by Eritrea during the war.

7. See Figure , location map of the study area.

8. The Amhara Democratic Party (ADP), formerly known as Amhara National Democratic Movement (ANDM) and The Oromo Democratic Party, formerly known as the Oromo Peoples’ Democratic Organization (OPDO) are key part of the coalition of Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF). In a dramatic move designed by Prime Minister Abiy, the era of EPRDF ended on 14 November 2019 with the foundation of a Pan-Ethiopian Party (Ethiopian Prosperity Party). The Prosperity Party includes all founding Parties of EPRDF but TPLF which agreed in principle but refused on the ground of practicality, legality, and political ideology. For many, the movement of a standing government to create a new party is a mockery of democratic rules and processes while for others it was just fine. Diverse arguments are put forward on this issue: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-50515636

9. Ministry of Information, Eritrea, “President Isaias’ speech on Martyrs’ Day”, 20 June 2018, <http://www.shabait.com/news/local-news/26520-president-isaias-speech-on-martyrsday>

10. PM Abiy won the 2019 Nobel Peace Prize mainly for ending the conflict between Ethiopia and Eritrea https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-50013273 while there are critics to the existing challenges in the region. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-50014318 https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/10/12/abiys-nobel-achievements-are-real-but-brittle/https://www.dw.com/en/opinion-nobel-peace-prize-for-abiy-ahmed-a-misguided-decision/a-50799722

11. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I6okcHWFyp8

12. A position long held by TPLF and EPRDF before Abiy. The Ethiopian government had accepted the UN decision of 2002 on the border in “principle” but requested for a “negotiation” on the implementation process.

13. Interview, 11 September 2018, Zalambessa.

14. For example, in Debay Sima—Bure crossing and Humera direction, the regional Vice president of Tigray was not invited, while reports say that he was able to show up in the Humera area. Paradoxically, it was the president of Amhara and Oromiya regions without direct territorial link with Eritrea who were invited. In an open statement, TPLF opposed the move and requested for clarity on the entire peace process.

15. In the past one year, the Vice President of the National Regional State of Tigray Debretsion is portrayed as a hero and is occasionally invited to public and religious holidays to speak in defense of Tigray. The ongoing tension with the neighboring Amhara National Regional State had fueled more tension and many Tigrayans are evicted from parts of Gonder. The TPLF’s narratives that Tigray is encircled by Isaias from the North, Abiy’s administration from the center and the Amhara State intrusion from the South seem to have gained popularity in Tigray.

16. Interview with a retired TPLF official; Mekelle, 25 May 2019.

17. For example, America’s foreign policy on Eritrea was fully driven by criminalizing the state of Eritrea, fully relaxed since April 2018.

18. A group of Eritreans and Ethiopians (Tigrayans) Men at Zalambessa mentioned that while the peace agreement was welcomed, the fact that it didn’t create an opportunity for the people from both countries to discuss the matter and leave things behind was not clear. Focus group discussion, October 2018, Zalambessa.

19. A 61-year-old teacher in Mekelle, 12 October 2018. He himself has been to Asmara on the same month the border was open.

20. Video Interview, a 65-years-old Eritrean man. Zalambessa, 11 September 2018. See Figure .

21. Interview, a 21-years-old Eritrean man, Mekelle, November 2018 .

22. https://twitter.com/KjetilTronvoll/status/1,211,943,215,814,848,513 accessed on 1 January, 2020.

References

- Abbay, A. (1997). The trans-mareb past in the present. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 35(2), 321–16. doi:10.1017/S0022278X97002462

- Abbink, J. (1998). Briefing: The Eritrean-Ethiopian border dispute. African Affairs, 97, 15. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a007970

- Abbink, J. (2001). Creating borders: Exploring the impact of the Ethio-Eritrean war on the local population. Africa :Rivista trimestrale di studi e documentazione, 56(4), 447–458.

- Abbink, J. (2003). Ethiopia—Eritrea: Proxy wars and prospects of peace in the horn of Africa. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 21(3), 407–426. doi:10.1080/0258900032000142446

- Abramson, D. (1999). International orders and international borders: Anthropological perspectives. International Studies Review, 1(3), 126–130. doi:10.1111/1521-9488.00169

- Africa News. (2019a, July 9). A year on – Ethiopia, Eritrea working to fully implement July 9 peace deal. Retrieved from https://www.africanews.com/2019/07/09/a-year-on-ethiopia-eritrea-working-to-fully-implement-july-9-peace-deal/

- Africa News. (2019b, July 24). Ethiopia-Eritrea relations hampered by closed borders, stalled trade deals. Retrieved from https://www.africanews.com/2019/07/24/ethiopia-eritrea-relations-hampered-by-closed-borders-stalled-trade-deals/

- Bayeh, E. (2015). The legacy of colonialism in contemporary Africa: A cause for intrastate and interstate conflicts. International Journal of Innovative and Applied Research, 3, 23–29.

- BBC. (2018a, September 11). Ethiopia-Eritrea border celebrations. the BBC News website. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-africa-45488306/ethiopia-eritrea-border-celebrations

- BBC. (2018b, November 14). Eritrea breakthrough as sanctions lifted. BBC News. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-46193273

- BBC. (2019a, October 11). Abiy Ahmed: The man changing Ethiopia. BBC News. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-43567007

- BBC. (2019b, October 11). Nobel peace prize: Ethiopia PM Abiy Ahmed wins—BBC News. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-50013273

- Belloni, M. (2019a). Refugees and citizens: Understanding Eritrean refugees’ ambivalence towards homeland politics. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 60(1–2), 55–73. doi:10.1177/0020715218760382

- Belloni, M. (2019b, October 10). Why young Eritreans are going to keep risking deadly migration crossings to Europe [News and analysis on African business, tech, and innovation]. Retrieved from https://qz.com/africa/1676254/young-eritreans-are-still-migrating-at-alarming-rates/

- Bereketeab, R. (2017). The role of the international community in the Eritrean refugee crisis. Geopolitics, History, and International Relations, 9(1), 68–82. Retrieved from https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=539285

- Bruton, B. (2018, July 12). Ethiopia and Eritrea Have a Common Enemy. Foreign Policy. https://Foreignpolicy.Com/2019/10/16/Will-Abiy-Ahmeds-Nobel-Prize-Tilt-Ethiopias-Election/. Retrieved from https://foreignpolicy.com/2018/07/12/ethiopia-and-eritrea-have-a-common-enemy-abiy-ahmed-isaias-afwerki-badme-peace-tplf-eprdf/

- Bruton, B. (2019, October 16). Will Abiy Ahmed’s nobel prize tilt Ethiopia’s election? Foreign Policy. https://Foreignpolicy.Com/2019/10/16/Will-Abiy-Ahmeds-Nobel-Prize-Tilt-Ethiopias-Election/. Retrieved from https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/10/16/will-abiy-ahmeds-nobel-prize-tilt-ethiopias-election/

- Clapham, C. (2018). The Ethiopian developmental state. Third World Quarterly, 39(6), 1151–1165. doi:10.1080/01436597.2017.1328982

- Clinton, W. J. (1999). Statement on the Eritrea-Ethiopia border conflict. Weekly Compilation of Presidential Documents, 35(6), 218. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=1712009&site=ehost-live

- Donnan, H. (2015). Borders, Anthropology of. In James D.Wright (Ed.), International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences, 2(2), 760–764. Elsevier. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.12028-8

- The Economist. (2018, July 17). How Ethiopia and Eritrea made peace. The Economist. Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/the-economist-explains/2018/07/17/how-ethiopia-and-eritrea-made-peace

- The Economist. (2019, July 11). Where’s the peace dividend? Eritrea’s gulag state is crumbling. The Economist. Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2019/07/11/eritreas-gulag-state-is-crumbling

- Ezega News. (2019, April 19). Eritrea closes omhajer-humera border crossings. Retrieved from https://www.ezega.com/News/NewsDetails/7070/Eritrea-Closes-Omhajer-Humera-Border-Crossings

- Feyissa, D., & Hoehne, M. V. (2008). Resourcing state borders and borderlands in the horn of Africa. Retrieved from https://www.eth.mpg.de/

- Fisher, J., & Gebrewahd, M. T. (2018). ‘Game over’? Abiy Ahmed, the Tigrayan people’s liberation front, and Ethiopia’s political crisis. African Affairs, 118(470), 194–206. doi:10.1093/afraf/ady056

- France 24. (2018, July 16). As ties thaw, Eritrea reopens embassy in Ethiopia. Retrieved from https://www.france24.com/en/20180716-isaias-ahmed-eritrea-ethiopia-reopens-embassy

- Gardner, T. (2018, October 12). “I was euphoric”: Eritrea’s joy becomes Ethiopia’s burden amid huge exodus. The Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2018/oct/12/eritrea-joy-becomes-ethiopia-burden-huge-exodus-refugees

- Gebregziabher, T. N. (2019). Ideology and power in TPLF’s Ethiopia: A historic reversal in the making? African Affairs, 118(472), 463–484. doi:10.1093/afraf/adz005

- Gilkes, P. (1991). Eritrea: Historiography and mythology. The Royal African Society, African Affairs, 90(361), 623–628. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a098473

- Hirt, N., & Abdulkader, S. M. (2018). Peace between Eritrea and Ethiopia: Voices from the Eritrean Diaspora. Life & Peace Institute, 30(3), 29–35. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328783457_Peace_between_Eritrea_and_Ethiopia_Voices_from_the_Eritrean_Diaspora

- House, C. (1999). Conflict in the horn: Why Eritrea and Ethiopia are at war - Eritrea [BRIEFING PAPER New Series No.1]. Retrieved from https://reliefweb.int/report/eritrea/conflict-horn-why-eritrea-and-ethiopia-are-war

- International Crisis Group. (2019, July 19). Preventing further conflict and fragmentation in Ethiopia | Crisis Group. Retrieved from https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/horn-africa/ethiopia/preventing-further-conflict-and-fragmentation-ethiopia

- Iyob, R. (2000). The Ethiopian–Eritrean conflict: Diasporic vs. hegemonic states in the Horn of Africa, 1991–2000. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 38(4), 659–682. doi:10.1017/S0022278X00003499

- Jeffrey, J. (2018, November 15). Eritrea-Ethiopia peace leads to a refugee surge. The New Humanitarian. Retrieved from https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news-feature/2018/11/15/eritrea-ethiopia-peace-leads-refugee-surge

- Jeffrey, J., & Belloni, M. (2019, April 30). Amid border wrangles, Eritreans wrestle with staying or going. The New Humanitarian. Retrieved from https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/feature/2019/04/30/amid-border-wrangles-eritreans-wrestle-staying-or-going

- Johnson, M., & Johnson, T. (1981). Eritrea: The national question and the logic of protracted struggle. African Affairs, 80(319), 181–195. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a097304

- Kurki, T. (2014). Borders from the cultural point of view: An introduction to writing at borders. Culture Unbound: Journal of Current Cultural Research, 6(6), 1055–1070. doi:10.3384/cu.2000.1525

- Lata, L. (2003). The Ethiopia-Eritrea War. Review of African Political Economy, 30(97), 369–388.doi:10.1080/03056244.2003.9659772

- Lefebvre, J. A. (2012). Iran in the Horn of Africa: Outflanking U.S. Allies. Middle East Policy, 19(2), 117–133. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4967.2012.00539.x

- Lyammouri, R. (2019). The outbreak of peace and symbolism of the Ethiopian-Eritrean border (Policy brief PB-19/11). Retrieved from https://www.policycenter.ma/publications/outbreak-peace-and-symbolism-ethiopian-eritrean-border

- Lyons, T. (2009). The Ethiopia–Eritrea conflict and the search for peace in the Horn of Africa. Review of African Political Economy, 36(120), 167–180. doi:10.1080/03056240903068053

- Mesghenna, Y. (1989). Italian colonialism in Eritrea 1882–1941. Scandinavian Economic History Review, 37(3), 65–72. doi:10.1080/03585522.1989.10408156

- Morello, C. (2018, November 14). U.N. lifts sanctions on Eritrea, ending the nation’s decade of international isolation [News]. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/un-lifts-sanctions-on-eritrea-ending-nations-decade-of-international-isolation/2018/11/14/dd4c7e14-e825-11e8-bbdb-72fdbf9d4fed_story.html

- Mulugeta, K. (2011). The Ethiopian-Eritrean War of 1998–2000 An analysis of its causes, course, impacts and prospects. In B. Mesfin & R. Sharamo (Eds.), Regional security in the post-cold war horn of Africa (pp. 31–64). Nairobi: Institute for Security Studies.

- Newman, D. (2003). On borders and power: A theoretical framework. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 18(1), 13–25. doi:10.1080/08865655.2003.9695598

- Puddu, L. (2017). Border diplomacy and state-building in north-western Ethiopia,. 1965–1977. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 11(2), 1–19. doi:10.1080/17531055.2017.1314997

- Reid, R. (2001). The challenge of the past: The quest for historical legitimacy in independent Eritrea. History in Africa, 28, 239–272. doi:10.2307/3172217

- Reid, R. (2003). Old problems in new conflicts: Some observations on Eritrea and its relations with Tigray, from liberation struggle to inter-state war. Africa, 73(3), 369–401. doi:10.3366/afr.2003.73.3.369

- Reid, R. (2005). Caught in the headlights of history: Eritrea, the EPLF and the post-war nation-state. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 43(3), 467–488. doi:10.1017/S0022278X05001059

- Reid, R. (2007). The trans-mereb experience: Perceptions of the historical relationship between Eritrea and Ethiopia. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 1(2), 238–255. doi:10.1080/17531050701452523

- Residents of Badme voice concern over handover to Eritrea. (2019, April 2). Retrieved from https://www.dw.com/en/residents-of-badwe-voice-concern-over-handover-to-eritrea/av-47349510

- Reuters. (2019, August 9). Eritrea’s military service still “repressive” despite peace deal: HRW. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-eritrea-rights-idUSKCN1UZ090

- Roussi, A. (2018). Despite the peace deal with Ethiopia, Eritrean refugees are still afraid to return home. Public Radio International. Retrieved from https://www.pri.org/stories/2018-09-13/despite-peace-deal-ethiopia-eritrean-refugees-are-still-afraid-return-home

- Schlee, G. (2003). Redrawing the map of the horn: The politics of difference. Africa: Journal of the International African Institute, 73(3), 343–368. doi:10.2307/3556908

- Seybolt, T. B. (2002). Major Armed Conflicts 2001. SIPRI Yearbook.

- Smidt, W. G. C. (2012). History, historical arguments and the Ethio‐Eritrean conflict: Between xenophobic approaches and an ideology of unity. Stichproben. Wiener Zeitschrift für kritische Afrikastudien, 12(22), 103–120.

- Steves, F. (2003). Regime change and war: Domestic politics and the escalation of the Ethiopia–Eritrea conflict. Cambridge Review of International Affairs, 16(1), 119–133. doi:10.1080/0955757032000075744

- Taddele Maru, M. (2019). The great game in the Horn of Africa. Retrieved from https://hornaffairs.com/2019/01/22/the-great-game-in-the-horn-of-africa/

- Trivelli, R. M. (1998). Divided histories, opportunistic alliances: Background notes on the Ethiopian-Eritrean war. Africa Spectrum, 33(3), 257–289.

- Tsegay, B. (2017). Jawar Mohamed and USA’s Interest in Ethiopia. Retrieved from https://hornaffairs.com/2017/12/20/jawar-mohamed-usa-interest-in-ethiopia/

- UN High Commissioner for Refugees. (2019). UNHCR Ethiopia: Fact sheet (September 2019) – Ethiopia. [Dashboards & Factsheets]. Retrieved from https://reliefweb.int/report/ethiopia/unhcr-ethiopia-fact-sheet-september-2019

- VOA. (2019, July 23). Hopes dashed as Ethiopia-Eritrea peace process stagnates. Retrieved from https://www.voanews.com/africa/hopes-dashed-ethiopia-eritrea-peace-process-stagnates

- Washington Post. (2018). Opinion: After 20 years, Eritrea and Ethiopia are making peace. We should all celebrate. Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/global-opinions/a-cause-for-hope-in-the-horn-of-africa/2018/07/13/780394c8-83b9-11e8-8553-a3ce89036c78_story.html

- Wilson, T. M. (2012). Territoriality matters in the anthropology of borders, cities and regions. Revista Cadernos Do Ceom, 25(37), 199–216. Retrieved from https://bell.unochapeco.edu.br/revistas/index.php/rcc/article/view/1438

- Woldemariam, M. (2018). “No war, no peace” in a region in flux: Crisis, escalation, and possibility in the Eritrea-Ethiopia rivalry. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 12(3), 407–427. doi:10.1080/17531055.2018.1483865

- Woldemariam, Y. (2019, February 5). The so-called peace process between Eritrea and Ethiopia. Retrieved from https://eri-platform.org/updates/so-called-peace-process-between-eritrea-and-ethiopia/

- Young, J. (1996). The Tigray and Eritrean peoples liberation Fronts: A history of tensions and pragmatism. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 34(1), 105–120. doi:10.1017/S0022278X00055221