Abstract

This paper demonstrates that the highly accurate depiction of the Indian Ocean on the Carta marina of Martin Waldseemueller from 1516 is mainly caused by the extremely powerful political and economic interests of the Portuguese Crown and the Upper German-trading companies in the conflict with the Kingdom of Castile over supremacy in the spice trade in India. It is shown that the Portuguese—after reaching the archipelago of the Moluccas before their Iberian rival in 1512—were subsequently most interested in the geographical documentation of the Spice Islands in the Southeast of Asia in order to claim the ownership for this economically extremely important part of the world. Furthermore, the paper aims to raise awareness of the fact that the resulting depiction of America on this map had become completely insignificant from a political point of view because of the changed political conditions in the second decade of the sixteenth century mentioned above. Finally, the cartographical representation will be related to the network of relationships between the Portuguese crown, the Upper German-trading companies and Maximilian I of Habsburg to illustrate the incredibly high correlation between the depiction of the 1516 Carta marina and the political and economic interests of all competitors involved in this commercial model.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

In general, world maps of past times are mostly considered from the point of view, how far historical cartography was developed in relation to the supposedly omniscient people of the present age. Therefore, these cartographic works are not genuinely appreciated, as it is much more important to classify them in the context of the respective time and to take the contemporary perspective seriously in one’s own research approach. Against this background, the paper on hand wants to prove that the accurate depiction of the Indian Ocean and of the Spice Islands on Martin Waldseemüller’s 1516 Carta marina is mainly driven by the documentation needs and the thereby associated ownership of the Portuguese crown in order to protect their political and economic interests as well as those of the Upper German-trading companies as opposed to the Kingdom of Castile.

1. Introduction

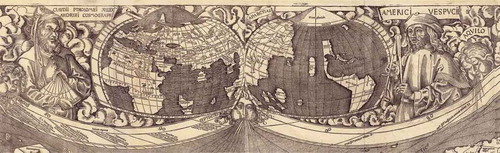

My 2016 paper about the depiction of America on Martin Waldseemüller’s 1507 world map—being the first map to utilize an insular concept for the newly discovered landmass in the west and the first to be associated with the cartographic birth of the Pacific Ocean—demonstrated the fact, which had remained unrecognized in modern research until this point of time, that this depiction was not primarily intended to be an accurate representation of the new world across the Atlantic Ocean based on the available geographic knowledge at the time (see also Lehmann, Citation2013, pp. 15–24).Footnote1 In contrast to the almost exclusively geographical explanatory approaches towards the 1507 world map, the paper instead managed to clarify that this depiction—quite revolutionary from a contemporary geographical perspective—should be regarded, to a much greater extent, as the result of extremely powerful political and economic interests of the Portuguese Crown and the Upper German-trading companies in the impending conflict with the Kingdom of Castile for supremacy in the spice trade with India at the beginning of the sixteenth century.Footnote2

In the course of this analysis, it was also made clear that the role of the Habsburg Regent Maximilian I in this network of mutual relationships, through his manifold relations with the Portuguese royal family in Lisbon, with the Upper German-trading companies of the Fugger and the Welser, and finally with the humanist circles on the Upper Rhine, went beyond that of a mediator and a patron of the commercial interests associated with the spice trade with India.Footnote3 As the Portuguese reached the Malabar Coast around Calicut and set up their first bases and factories there in the first years of the sixteenth century, they came to the sobering realization that the actual Spice Islands were located much further away in the southeast of the Indian Ocean. This geographical situation raised the prospect of a scenario that was dreaded by all actors involved in this commercial model, namely that the Iberian competitor would forestall them in the development and exploitation of the Spice Islands of Southeast India via the western sea route, so-to-speak through the back door (see also Schmitt, Citation1984, pp. 227–230).Footnote4

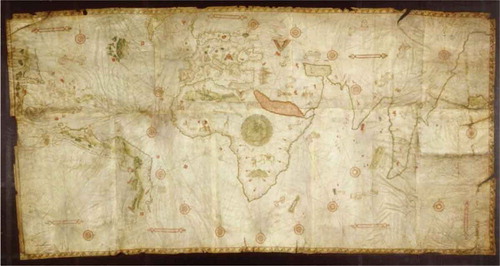

Against this background, it was shown that the American landmass depicted on Waldseemüller’s 1507 world map as an intermediate world on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean that extends far from North to South did not correspond to the geographical beliefs of Waldseemüller, but was depicted in this way only with the aim of convincing the Iberian competitor that it was impossible to reach India through the western sea route with little risk and with reasonably justifiable financial outlay (see also Schmitt, Citation1997, pp. 11–12).Footnote5 In addition, it was made clear that the cartographic depiction of the Indian Ocean and the Spice Islands—the key drivers of the India trade—, which is closely related to the depiction of America, was quite deliberately prepared on the basis of over one thousand year old Ptolemaic specifications, despite the availability of newer maps—in particular, the manuscript map of Nicolo Caveri dating from 1503 was cited as evidence—in order to additionally confuse the Iberian competitor, after confronting them with the sobering representation of America, by obfuscating the actual geographical situation in the Indian Ocean and in this way effectively preventing them from accessing the extremely lucrative spice trade, at least for a certain period of time (see also Van Duzer, Citation2012, p. 8).Footnote6 Here, the manner in which the politically motivated obfuscation of the true geographical situation in the Indian Ocean is presented as a scientifically motivated endeavor is a true masterpiece of cartographic manipulation, as the entire system of the world map, with the eye-catching depiction of the two planiglobe views at the top of the map, is deliberately designed to contrast the Old World presented by the ancient geographer Claudius Ptolemy conspicuously against the New World presented by Amerigo Vespucci. With this shrewd strategy, the Portuguese were able to elegantly counter any suspicions arising in Castile that the Ptolemy-based, in essence completely outdated depiction of the situation in the Indian Ocean, had even remotely anything to do with a politically motivated obfuscation aimed to further their interests and support their power politics in connection with the Indian spice trade.

Figure 1. Detail of the 1507 Waldseemüller map with the witnesses of the Old World and the New World (Library of Congress Washington, Geography and Map Division)

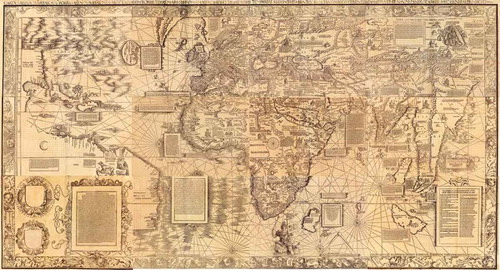

In addition to these comments on the 1507 world map, the paper on hand aims to illustrate to what extent the changed political conditions in the second decade of the sixteenth century—meanwhile the Portuguese had reached the actual Spice Islands in the archipelago of the Moluccas located further to the southeast before their Iberian competitor, and had established the first factories there—had a decisive impact on the 1516 Carta marina. As a matter of fact, the highly accurate depiction of these southeast Indian Spice Islands on the 1516 Carta marina, which was completely changed in comparison to the 1507 version, especially with regard to the area of the Indian Ocean, demonstrates that the documentation needs and the thereby associated ownership claims of the Portuguese were now at the heart of their political and economic interest (see also Fischer & Wieser, Citation1903; Van Duzer, Citation2012).Footnote7 Furthermore, based on the map face of Southeast Asia from the Carta marina, the paper aims to raise awareness of the fact that the resulting depiction of America on this map, which by now had become completely insignificant from a political point of view because of these factors, now offered a lot of space for Waldseemüller to show his actual geographical beliefs that revolved around a continental concept, at least as far as the northern section of the newly discovered landmass was concerned. Beyond that, the observations made in relation to the political character of the Carta marina map should be related to the network of relationships between the Portuguese crown, the Upper German-trading companies and Maximilian I of Habsburg, which I have already touched upon in my earlier paper. This is to show that even the 1516 Carta marina—which is just as strongly influenced by Portuguese interests as the 1507 world map—was not primarily intended to fulfill a geographic function, but rather represented an explicitly expressed political message to the Iberian competitor in the contest for the spices of Southeast India.

2. The political function of Waldseemüller’s Carta marina

Waldseemüller references the nature of the Carta marinaFootnote8 published in 1516 in the very title of the map by pointing out that, unlike the map’s famous predecessor from 1507, this map is designed as a nautical chart and proceeds to cite Portuguese seafaring expeditions as the most important sources:

Carta marina navigatoria Portugallen navigationes, atque tocius cogniti orbis terre marisque formam naturam situs et terminos nostris temporibus recognitos et ab antiquorum traditione differentes, eciam quor[um] vetusti non meminerunt autores, hec generaliter indicat.

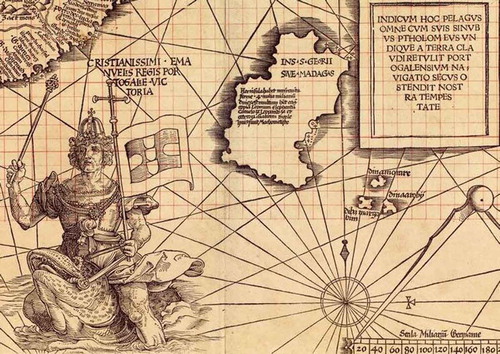

Unlike the 1507 world map, the Carta marina reproduces the actual geographical situation in the Indian Ocean—at least as far as it was known at the time—which was represented on the 1507 world map according to Ptolemaic specifications, despite the availability of newer maps, for the purpose of obfuscation (see also Fischer & Wieser, Citation1903, p. 3).Footnote9

Figure 2. Waldseemüller’s 1516 Carta marina (Library of Congress Washington, Geography and Map Division)

In fact, the cartographic depiction of both Indian peninsulas looks like a copy of the manuscript map of Nicolo Caveri, which was already mentioned in connection with the 1507 world map.

The map face, which has undoubtedly been taken over from Caveri, is extended by the Spice Islands of Southeast India, which had since been reached and occupied by the Portuguese, with the islands being annotated beyond their cartographic representation—as exemplified by the island of Banda—with explanatory texts according to their economic significance:

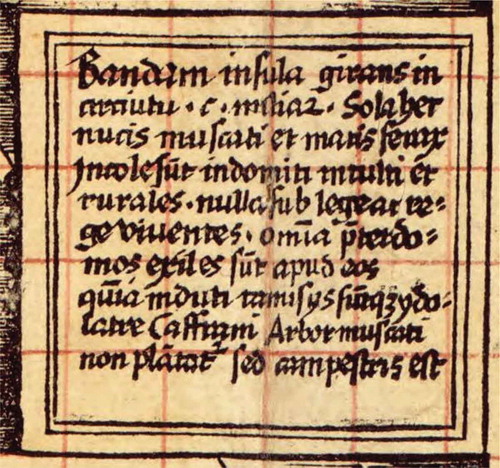

Figure 4. Detail of Waldseemüller’s 1516 Carta marina with the description of the Banda spice island (Library of Congress Washington, Geography and Map Division)

The nutmeg tree and sea almond spices endemic to the island of Banda are described as follows:

Bandam insula[…]. Sola haec nucis muscati et maris ferax. Incolae sunt indomiti, inculti et rurales nulla sub lege ac rege viventes. […] Arbor muscati non plantatur, sed campestris est.

The Banda island […]. This is the only island where nutmegs and sea almonds grow. The inhabitants are uncultured savages, living as peasants without laws and kings. […]. The nutmeg tree is not planted specifically but occurs naturally here.

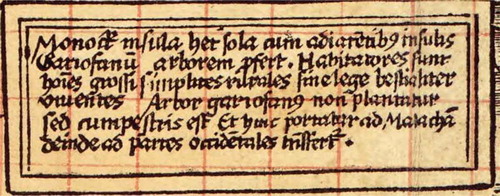

In connection with the island of Monoch—another island of the Moluccas—Waldseemüller not only discusses the endemic cloves but also describes the important trade route to the market of Malacca, which functions as a hub for the southeast Asian spice trade:

Figure 5. Detail of Waldseemüller’s 1516 Carta marina with the description of the Monoch spice island (Library of Congress Washington, Geography and Map Division)

The associated text reads as follows:

Monoch insula. Haec sola cum adiacentibus insulis gariofanum arborem perfert. […] Arbor gariofanus non plantatur, sed campestris est. Et hinc portatur ad Malacham, deinde ad partes occidentales transfertur.

The island of Monoch. The clove tree is endemic to this and the surrounding islands. […]. The clove tree is not planted specifically, but occurs naturally here. And from here, the cloves are brought to Malacca, from there they are then shipped further west.

Furthermore, Waldseemüller uses a large block of text inserted in the upper right corner of the map, entitled Loca insigniora, de quibus portantur aromata ad Calicutium, emporium omnium celebratissimum, hec sunt, to list, in detail, all important locations from which the various spices—mentioned by name—are transported to Calicut, the transshipment hub for the spices of India, and also specifies the exact distances from these locations to Calicut.Footnote10

The very fact, that the Spice Islands of Southeast India are presented cartographically in such a meticulous manner and described in detail with distinctive blocks of text, makes it clear that the Portuguese and the Upper German-trading companies profiting from the spice trade attached great importance to this commercial model.

However, Waldseemüller succeeds in putting the Southeast Asian archipelago at the center of the observer’s attention by using another ingenious cartographic technique that goes beyond the illustration of the Spice Islands as described above. Although the Carta marina, measuring 128 × 133 cm, is exactly the same size as the 1507 world map, no fewer than one hundred and twenty eight degrees of longitude—extending over more than one-third of the world’s total area from east to west—were left out of it, which achieves the effect desired by the Portuguese in that it is precisely the areas of Southeast Asia that are enlarged—as if viewed through a magnifying glass—and therefore presented in more detail (see also Van Duzer, Citation2012, pp. 14–17).Footnote11 This circumstance, hitherto neglected in research concerning the political context, is also remarkably useful in establishing a connection between the conspicuous need for documentation of the Portuguese with their political and economic interests in the Indian Ocean.

Aside from that, the choice of the specific map type, which is fundamentally different from that used in the previous map, does not constitute a random decision on the part of the cartographer, but is similarly attributable to the pronounced need for documentation of the Portuguese. While it was in the best interest of the Portuguese, for political reasons, to show as little as possible and to obfuscate the actual geographical situation in 1507, nine years later, again for political reasons, the attention was focused, paradoxically, on making the cartographic representation of these areas as accurate as possible. Of course, this goal could be achieved much more easily by using a nautical chart specifically designed for navigation, such as the Carta marina, since such maps featured a naval orientation system with lines—the so-called rhumb lines—that allowed navigators to establish the course fairly accurately with a compass, and to follow this course more or less accurately even without seeing any land. Thus, the mere choice of a different map type—a nautical chart based on portolan charts—made it possible to rule out, preemptively, any potential errors regarding the exact geographical location of the Spice Islands in Southeast Asia.Footnote12

However, even portolan charts, which were originally designed for smaller areas such as the Mediterranean Sea, may not have been accurate enough for a larger body of water such as the Indian Ocean. This is probably the reason why—in addition to using the plotted compass lines—, Waldseemüller also made use of a well-defined mathematical projection, which is actually unusual for portolan charts, in both the 1507 world map and the Carta marina. The projection favored by Waldseemüller in 1516, also known as an equirectangular projection, is an equidistant cylindrical projection in which the lengths of meridians are essentially preserved and normally the equator is the only line of latitude whose length is preserved (see also Stückelberger & Grasshoff, Citation2006, pp. 108–11).Footnote13 This projection generates a rectangular coordinate system and is extremely well suited for the uncomplicated and rapid entry of certain points based on geographic coordinates (see also Wagner, Citation1962, p. 72).Footnote14 There is one specific property of the projection type used by Waldseemüller that is of paramount importance in the context of this paper. Namely, notwithstanding the fact that, strictly speaking, equirectangular projection does not preserve most angles and areas correctly, it can still be used—assuming that the equator line is the only line of latitude whose length is preserved—to represent the angles and areas of equatorial regions reasonably well, because the distortions only start to appear noticeably at mid-latitudes and then only increase sharply near the two poles (see also Müller & Krauss, Citation1983, p. 34).Footnote15 For example, under the above-mentioned conditions, the distortion value measuring angle preservation on the twentieth degree of latitude is only 3.56 degrees (see also Wagner, Citation1962, p. 71).Footnote16 Hence, the projection type chosen by Waldseemüller—in addition to the use of compass lines as described above—made it possible to define the Spice Islands, which are located primarily between the equator and the Tropic of Capricorn, more precisely in geographical terms on the Carta marina.Footnote17

If we were to summarize the evidence presented so far, the cartographic depiction of the Indian Ocean and the Spice Islands of Southeast India can only be understood as motivated by the urgent need of the Portuguese to document the Spice Islands in the archipelago of the Moluccas, which they only managed to reach before their Iberian competitor with immense effort and at great cost, clearly and in accordance with their interests, in order to be able to—as was common at the time—simultaneously derive ownership claims based on such documentation. The inclusion of a pair of dividers along with precise scales in intervals of twenty German miles at the bottom of the map in the middle of the Indian Ocean also points towards the same conclusion.

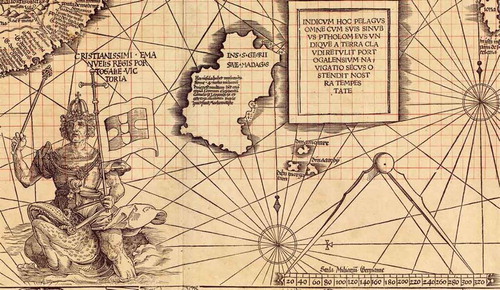

Figure 6. Detail of Waldseemüller’s 1516 Carta marina depicting a pair of dividers, the Portuguese King Manuel and a text about the achievements of the Portuguese (Library of Congress Washington, Geography and Map Division)

In order to add the crowning touch, so-to-speak, to the cartographic documentation of the Portuguese claim to power in India, Waldseemüller depicts the Portuguese king, wearing the standard imperial insignia and carrying the Portuguese flag attached to a cross, riding on a fish or a sea monster, at the western entrance to the Indian Ocean, and makes the very telling comment Christianissimi Emanuelis regis Portogaliae victoria.Footnote18

At the same time, this clearly expressed ownership claim of the Portuguese is legitimized with a text block inserted in the middle of the Indian Ocean that states that the Portuguese expansion has made a ground-breaking contribution towards the geographical re-evaluation of the situation there, which is accompanied by the realization that the Indian Ocean is not, as claimed by Ptolemy, an inland sea that is closed off on all sides but must rather be regarded as part of a world-spanning ocean:

Indicum hoc pelagus omne cum suis sinubus Ptholemeus undique a terra claudi retulit, Portogalensium navigatio secus ostendit nostra tempestate.

Ptolemy reported that this whole sea, along with its bays, is surrounded on all sides by land, Portuguese navigation has revealed the actual conditions in our time.

Hence, even if we were to leave aside the cartographic depiction in a narrower sense, the intentional introduction of these illustrations into the Carta marina makes it clear that the primary aim is to emphatically cement the dominant position that had just been established by the Portuguese towards the Castilian crown in the years to come.

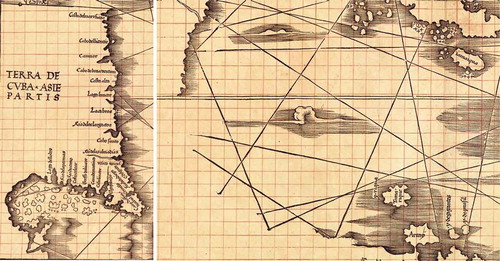

3. The Carta marina and the depiction of America

Just as the insular concept of America in the 1507 world map has to be closely associated with the obfuscation of the actual geographical situation in the Indian Ocean, it is not quite surprising that the Carta marina also exhibits a very specific relationship between the meticulous documentation of the geographical situation in the Indian Ocean and a depiction of America that is based, remarkably, on a continental concept—at least as far as the northern part of the newly discovered part of the world is concerned. Namely, after the Portuguese domination of the spice trade with India was secured against the Castilian competition, including in the archipelago of the Moluccas, the depiction of America in the Carta marina abruptly lost its political utility, because the scenario that had been dreaded in Portugal for almost a decade—that the Castilians could reach the Southeast Asian Spice Islands before them via the western sea route—was no longer hanging as a Sword of Damocles over their head. Consequently, Waldseemüller was now able to realize his own ideas based on the knowledge available at the time and he proceeded to depict the newly discovered landmass on the other side of the Atlantic as a continent that was spatially connected to Asia. The question as to whether he wanted to connect the northern part, which was labeled as Terra de Cuba Asiae partis, with the southern part cannot be answered with certainty on the basis of the map face. Although the unusual fact that the rhumb lines end before the edge of the map might create the impression that there is an implied connection between the two landmasses, in my opinion, this can only be evaluated as weak evidence for Waldseemüller’s intention to indicate the existence of a connected American landmass.

Figure 7. Detail of Waldseemüller’s 1516 Carta marina depicting North America as a part of Asia (left) and the southern part (right) (Library of Congress Washington, Geography and Map Division)

Nor can the fact that Waldseemüller depicted this part of the world—which was generally still considered insular at the time—as a single landmass in the Ptolemy Atlas of 1513 be used as an argument for the claim that he therefore pursued this idea in the Carta marina. The section below explores the mutual relationships and dependencies of the various competitors in the spice trade with India and their resulting common interests in more detail, and then makes a connection to the depiction in the Carta marina in order to better classify the political semantics established on the basis of the map face of the Carta marina through integration in the political horizon at the time.

4. Mutual relationships and dependencies in early modern Europe

4.1. Maximilian I of Habsburg and Portugal

Maximilian’s mostly positive relationship with the Portuguese crown family—his mother Eleonore was descended from the marriage of the Portuguese King Eduard I and Eleonore of Aragon—was not only attributable to his family connections but also demonstrably linked to tangible political and economic interests. As the ruler of the Burgundian Netherlands, Maximilian maintained close relations with the House of Avis, despite the fact that there were definitely certain differences regarding the future succession in Portugal, and often exchanged envoys with them.Footnote19 There were quite a few Portuguese commercial enterprises in the up-and-coming Dutch ports, and at the same time, German and Burgundian trade colonies operated successful subsidiaries in Portugal (see also Wiesflecker, Citation1986, p. 448).Footnote20 Many Germans and Dutch worked as armory custodians, captains and printers in the service of the King of Portugal (see also Krendl, Citation1982, p. 172).Footnote21 In addition, cooperation with Ferdinand of Aragon proved to be difficult for a number of reasons, which made it more favorable for Maximilian to ally with the Portuguese King John II during the early years of European expansion (see also Wiesflecker, Citation1986, pp. 448–449).Footnote22

One of the impressive historical artefacts evidencing Maximilian’s keen interest and great involvement in the Portuguese expansion is the 14 July 1493 letter composed by Hieronymus Münzer, a physician and humanist from Nuremberg, on behalf of Maximilian, in which he suggests to the Portuguese king that he should seek to find the rich Cathay via the western sea route, because “the beginning of the habitable East is located very close to the end of the habitable West”.Footnote23 In this regard, Wiesflecker makes the astute conjecture that Maximilian, being aware of Columbus’ first voyage, wanted to urge the Portuguese king to launch this expedition in order to forestall the possible arrival of the Castilian crown in the Indian Ocean via the western sea route (see also Wiesflecker, Citation1986, p. 449).Footnote24 Since Münzer’s letter seems to have been received with utter indifference by the Portuguese court, it can be presumed that the Portuguese king already knew, after Bartolomeu Dias’ expedition in 1488, that the final opening of the eastern sea route to India was now very close and therefore he was not worried by the scenario feared by Münzer and Maximilian (see also Krendl, Citation1980, p. 11).Footnote25 Eventually, it still took ten more years until Vasco da Gama was able to realize the final stage in the opening of the eastern sea route to India.

A letter preserved from this period from the new Portuguese king Manuel I—who succeeded John II after the latter died in 1495—to Maximilian informs the Habsburg regent in vivid detail about Vasco da Gama’s successful return from India and promises him to keep the discoveries open for the emperor and his empire (see also Wiesflecker, Citation1986, pp. 449–450).Footnote26 The Portuguese king kept his word. As early as 1503, the Welser family received a privilege for trade with India. In addition, in 1505, Maximilian issued a letter of recommendation to several merchants of the Welser and Fugger families and sent it to the Portuguese king, thus enabling them to participate in the India voyage of Francisco d’Almeida (see also Krendl, Citation1982, p. 180).Footnote27

4.2. The Portuguese crown and the Fugger family

As the trade relations of the Fugger family with spice-trading countries through the transshipment port in Venice, which used to flourish for a long time, almost ground to a halt at the end of the fifteenth century due to the advance of the Ottomans in the Near East and especially due to the Mamluk uprising in Egypt in 1496, the Augsburg-based merchant family relocated its most important foreign trade office to Antwerp, an up-and-coming market in the Netherlands (see also Kellenbenz, Citation1990, p. 49).Footnote28 The long-standing contacts of Upper German merchants with the Portuguese crown—as described, Hieronymus Münzer had entered into diplomatic contact with king John II on behalf of Maximilian I of Habsburg as early as 1493—were intensified and, after the opening of the eastern sea route to India by Vasco da Gama in 1498, this led to a situation where the Fugger family, as well as other Upper German merchant families—the Welser family is particularly noteworthy in this regard—became the most important distributors of Indian trade goods (see also Wiesflecker, Citation1986, p. 449).Footnote29 Grosshaupt describes this process as follows:

“In Portugal they had early realized that the exclusion of the previous spice trade via Venetian and Arab merchants could not be accomplished without the participation of the powerful Upper German companies. Immediately after the contract with the Welser family had been signed, further Upper Germans tried successfully to obtain similar privileges from the Portuguese crown. On 6 October 1503, Ulrich Fugger and his brothers received the same privileges. The agent of the Fugger family in Lisbon, Marx Zimmermann, could therefore break the monopoly of the Welser family.”Footnote30 (See also Grosshaupt, Citation1990, p. 370)

The granting of numerous privileges, which were accompanied by trade facilitation measures, and even included citizenship of the city of Lisbon, prove that the Portuguese crown held the Upper German commercial companies in extremely high regard (see also Cassel, Citation1771, p. 11).Footnote31 Of course, there were sound reasons for their high reputation in Portugal, and these reasons largely revolved around the considerable economic power of the Upper German-trading companies. This is because, even though king Manuel I of Portugal had just gained access to a lucrative source of income from the newly opened Indian spice trade, he still urgently needed outside capital for the equipment of the ever-increasing spice fleets, the construction of naval bases and the intended containment of the intermediary trade by Arabs in the Indian Ocean (see also Kellenbenz, Citation1990, p. 50).Footnote32 This facilitated connections with the Upper German-trading companies as these were among the largest creditors in Europe at the time. In addition to valuing their importance as creditors, the Portuguese Crown was also dependent on the Upper German-trading companies as buyers of overseas products since they were able to offer the best sales conditions through their large factories in Antwerp and their extensive distribution network in Europe (see also Kellenbenz, Citation1990, p. 10).Footnote33

In this context, it is quite significant that, at the beginning of the sixteenth century, the Fugger trading company had established itself as a reliable supplier of large quantities of copper, which could be used as a valuable and profitable means of payment in the trade with India, since the latter did not have any copper deposits (see also Kellenbenz, p. 10).Footnote34 The enormous importance of these copper deliveries becomes clear against the background that, after purchasing the copper mines in Tyrol and Upper Hungary—today’s Slovakia—it only took the Fugger family a few years to obtain a monopoly position in copper shipping, processing and trade, which propelled it to become an indispensable and privileged trading partner for the Portuguese crown (see also Häberlein, Citation2006, pp. 40–47).Footnote35 The Upper Hungarian copper was shipped across the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to Antwerp, where it was then purchased by Portuguese merchants for the Indian trade. An archeological testament to this lucrative and quite perilous long-distance trade was unveiled to the public in 2017 with the announcement of a Portuguese shipwreck off the coast of Kenya—the sunk ship was discovered as early as 2008—which contained a large number of copper ingots marked with the “trident” sign—the trading sign of the Fugger family. This discovery—as well as the discovery made that same year off the coast of Namibia and the Portuguese shipwreck discovered only in 2019 in the territorial waters of the Netherlands—clearly illustrate that this was not a relationship in which the Fugger family was unilaterally dependent on the Portuguese as their partner and political protector in the trade with Indian spices, but rather that, considering the scarcity of copper and the high demand for it in India, as well as the financial capabilities of the Fugger family, the Portuguese crown was involved in a far-reaching relationship of mutual dependency with the Augsburg-based trading company.

4.3. Maximilian I of Habsburg and the Fugger family

Although Maximilian had received financial support from various Upper German commercial companies at the beginning of his reign—with some of the most important donors including the Augsburg-based Höchst, Baumgartner, Gossenbrot, Gassner, Herwart and Adler families—in the long term, it was still predominantly the Fugger family—also based in the city on the Lech river—who were most consistent in supporting the rise of Maximilian to become emperor with their loans.Footnote36 Jakob Fugger—who was also known as Jakob the Rich, for good reason, and who became the sole manager of the company after the death of his brothers Ulrich (1506) and Georg (1510)—recognized quite early on that the rising power of the Habsburgs and the establishment of a universal global empire could be exceptionally useful for the promotion of his own commercial interests that were oriented towards the development of new markets (see also Wiesflecker, Citation1986, p. 588).Footnote37

However, the loans provided by the Fugger family, which may well have reached some one million Gulden within the first ten years of Maximilian’s rule, were not intended solely as an investment in a future global empire under Maximilian’s leadership but were also most certainly granted in consideration of the resulting opportunities for greater profits (see also Wiesflecker, Citation1986, p. 586).Footnote38 More specifically, while the Fugger family did provide funding for the expensive royal court and for Maximilian’s numerous wars—some examples include the Italian campaign of 1496, the Swiss war of 1499 and the Bavarian-Palatine Succession War of 1505—while also financially supporting his costly artistic projects, they received in return numerous silver and copper mines, whose ownership made them the most important mining company in the empire in the course of just a few years. After the Fugger family had secured their monopoly position in copper shipping, processing and trade by means of numerous loans provided over the years, and after the emperor could offer no further mines in return, the Habsburg regent went on to cede numerous settlements, including entire fiefdoms and counties, to Jakob Fugger. This also led to the social rise of the Fugger family, who even obtained membership in the Imperial Estate—along with the county of Kirchberg—as Jakob Fugger had previously supported Maximilian in his 1508 Italian campaign with the sum of 50,000 Gulden.Footnote39 In 1511, Maximilian finally raised his potent financier to nobility; just three years later, he was even made a count (see also Wiesflecker, Citation1986, p. 586).Footnote40

This should make it sufficiently clear that the rise of Maximilian as Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation is inextricably linked to the history of the Fugger family. The interdependencies also created a solid foundation for the lasting existence of this business model within this network of relationships. This is because neither the Fuggers were able to realize their economic goals within and outside of the empire without the protecting hand and far-reaching political influence of Maximilian nor was Maximilian able to even conceive of seriously pursuing his far-reaching political goals without the aid of his principal financiers. Accordingly, it is not surprising that this alliance between the political ruler Maximilian and the leading Upper German merchant family of the Fuggers proved extremely fruitful and was defended fiercely against any form of outside interference, and this also applies and is especially relevant for the development of the eastern sea route to India.

4.4. Maximilian I of Habsburg and Martin Waldseemüller

Of course, when we look at this widely branching network of complex relationships and mutual political and economic dependencies in the power elite of Europe, we cannot help but ask why exactly Martin Waldseemüller was entrusted with this task that was politically delicate and extremely important from a financial point of view, as well as why this controversial work was performed in the small Lorraine town of St. Dié. A meaningful early clue for the answer to this question is surely provided by the relationship of trust that had already existed for a long time between the family of the Wolfenweil cartographer and Maximilian I of Habsburg. More information about this relationship can be found, e.g., in a letter of the Habsburg regent to the Freiburg council and the mayor of the city from 6 July 1492, in which he responds to the personal request of Jakob Waltzenmüller—the uncle of Martin Waldseemüller—by emphatically demanding the investigation of the murder of Martin’s father, Conrad Waltzenmüller, and advising them, in no unclear terms, to punish such an abominable crime—as expressed by Maximilian—appropriately and to take measures to prevent such crimes from happening in the future.Footnote41 Conrad Waltzenmüller had been found slain on the morning of 19 June 1492, in front of the Butchers’ Guild Hall in Freiburg, a crime whose deeper cause may well be attributable to his efforts to change the allocation of the Council with the aid of Kaspar Rotenkopff, who later went on to become the guild master of the shoemaker guild (see also Scott, Citation1987, pp. 69–93).Footnote42 The personal relationship between Gregor Reisch, the learned and highly esteemed—far beyond Breisgau’s borders—Carthusian prior, teacher of Waldseemüller and Ringmann at the University of Freiburg, and author of Margarita Philosophica and Maximilian, with whom he served for many years as an adviser and later as a confessor, probably also played a not insignificant role in the described relationship of trust between Maximilian and Waldseemüller’s family (see also Heinzer, Citation2014, pp. 113–125).Footnote43 Of course, another factor, which Maximilian and all powers involved in this project considered a lucky circumstance, was that, in 1506, as the Portuguese found out—much to their consternation—that the Spanish could potentially forestall them on the way to the Spice Islands of the East Indies via the western sea route, Waldseemüller and Ringmann were already working on a new edition of Ptolemy’s Geography in St. Dié.Footnote44 A printing facility had also already been established at the Vosagense Gymnasium so that the organizational framework conditions enabled swift work on the “media package” of St. Dié.

5. Summary

Overall, this paper should have made it clear that the political and economic interests of the European great powers at the beginning of the sixteenth century exercised a decisive influence on the preparation of Waldseemüller’s two world maps.

Here, it is extremely important to understand that, on the one hand, especially during the first two decades of the sixteenth century, the primary and almost exclusive interest of the Iberian powers consisted in securing the profitable spice trade with India while the pursuit of the discoveries in the western Atlantic Ocean initially played a subordinate role to this project, and, on the other hand—and this represents a logical consequence from the circumstance just described here—the depiction of America on both maps cannot be viewed as an isolated occurrence as it is inseparably linked to the reproduction of conditions in the Indian Ocean, and the two should ultimately be regarded as two sides of the same coin.

Furthermore, it should have become apparent that, after the Portuguese arrived at the archipelago of the Moluccas, under changed political framework conditions compared to 1507, the remarkably accurate depiction of the Indian Ocean in the Carta marina, with all cartographic bells and whistles, was attributable to the pronounced need for documentation of the Portuguese crown with the aim of strengthening their ownership claims in this region. This desire to achieve a highly accurate depiction is expressed lucidly through the choice of the characteristics of a nautical chart, which is intended for maritime navigation, and through the clearly noticeable magnifying effect driven by the absence of over 120 degrees of longitude. The projection type of the Carta marina, which is actually unusual for nautical charts, can also be interpreted in this sense. The large, conspicuously designed texts for the Southeast Indian Spice Islands and the inclusion of a pair of dividers with the exact specification of distances in miles, as well as the depiction of the Portuguese king sitting on a throne at the western end of the Indian Ocean all point towards the same conclusion. Likewise, it should have become clear that at least partially continental depiction of America on the 1516 Carta marina, as a result of the changed political framework conditions, is much more in line with Waldseemüller’s actual beliefs about the geographic concept of the newly discovered landmass in the western Atlantic Ocean compared to the separate depiction of America on the 1507 world map. Finally, this paper makes a connection between the observations made on the basis of the Carta marina map face about the political character of the depiction of the Indian Ocean and the mutual relationships and dependencies of the European political elite and further substantiates these observations by incorporating them into the political context at the time.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Martin Lehmann

Martin Lehmann works as a teacher of Latin, geography and history at a German academic grammar school and teaches students in the department of Greek and Latin philology at the University of Freiburg. The scientific focus of his work aims at the contemporary perspective of the discovery of America and its ancient and medieval foundations. The first result of this research is represented by the dissertation about the Cosmographiae Introductio of Matthias Ringmann and the 1507 world map of Martin Waldseemüller submitted to the University of Freiburg in 2010. After further scientific publications in academic journals (Imago Mundi/Wolfenbütteler Renaissance-Mitteilungen/Neulateinisches Jahrbuch), he published a German translation and a comment of Waldseemüller’s 1509 Globus Mundi in 2016. In 2018 he qualified as a university lecturer (PD) at the University of Freiburg in medieval and early modern Latin. Also in 2018 he edited a volume entitled Alexander Ethicus? Zur moralischen Dimension des Alexanderbildes in der Alexandreis des Walter von Châtillon.

Notes

1. See also Lehmann (Citation2016). Interestingly, the separate depiction of America does not correspond to the geographical concept of Vespucci at all, despite the fact that Waldseemüller presented the Florentine as the key witness for that very depiction on his 1507 world map. As evidenced by his letters, Vespucci believed that the New World he discovered was a landmass that reached far to the south and was spatially connected to Asia. See also Lehmann (Citation2013, pp. 15–24).

2. One of the papers that is typical for the research approach in which Waldseemüller’s world maps are analyzed solely on the basis of the sources utilized by them and in which the analysis is performed exclusively from a cartographic point of view is the paper—whose naiveté is hard to surpass—by Van Duzer (Citation2012, pp. 8–20). The downright grotesque idea expressed implicitly in it that Waldseemüller was able to produce and publish a world map such as the one from 1507—of which no less than a thousand copies were printed—of his own accord and practically at his own expense, without being integrated in a well-functioning system of political rulers, leads to van Duzer’s three surprised questions regarding the 1491 Yale map of Henricus Martellus used in St. Dié: “How was it that Waldseemüller was able to obtain this large and no doubt expensive map in Saint Dié, the town he worked in near Strasbourg? How did he find out about the map’s existence, and how was he able to afford it? I do not yet have an answer to these questions, […]. See also Van Duzer (Citation2012, p. 12).

3. Maximilian I—as will be shown more detailed at the end of this paper—of course was also able to satisfy his own economic and political interests within this commercial model.

4. The Portuguese learned from a 1506 report by the Italian traveler Ludovico di Varthema that the spices traded in Calicut and at the Malabar Coast did not originate from the Indian mainland itself, but from the islands around Malacca and the Moluccas, further to the east. It is no coincidence that work on the Ptolemy edition, which had already begun at the Gymnasium Vosagense, was paused at this exact moment, so that all efforts over the next few months could be directed towards the large 1507 world map. In the end, the Ptolemy atlas was not made available until 1513, when it was published in Strasbourg. The Portuguese were only able to capture Malacca in 1511. The Moluccas were discovered shortly thereafter in 1511/1512. See also Schmitt (Citation1984, pp. 227–230).

5. Similarly to the unwavering presentation of the landmass in the western Atlantic as an almost impassable barrier, the cartographic birth of the Pacific Ocean, which was completely unknown in Europe at the time, was also aimed at dampening the hopes of the Castilian crown for a western passage to India. Quite tellingly, even in later times, when Waldseemüller’s geographic concept paradoxically turned out to be correct, the western sea route to India never became a serious rival to the eastern sea route for precisely these reasons. See also Schmitt (Citation1997, pp. 11–12).

6. There is no doubt among researchers, and justifiably so, that Waldseemüller had been in possession of the Caveri map while preparing for his work on the 1507 world map. For example, van Duzer states the following in support of this fact: “In fact, Waldseemüller even repeats errors on Caverio’s map, so he was using this specific map as a source—that is, he had this specific map in his workshop.” See also Van Duzer (Citation2012, p. 8). However, van Duzer stays on a purely descriptive level and surprisingly does not ask the question why Waldseemüller used Caverio’s map only for the representation of the east coast of South America, and not for depicting the actual situation in the Indian Ocean.

7. For the two world maps of Waldseemüller, see also Fischer and Wieser (Citation1903). A new facsimile edition has been published by Hessler and van Duzer (Citation2012). Unfortunately, this new publication, albeit very appealingly designed, also has an exclusively descriptive character, without going into the obvious political implications of Waldseemüller’s two world maps. A comparison of Waldseemüller’s Carta marina to the maps of Laurent Fries is provided by Petrzilka (Citation1968).

8. The Carta marina is also part of the Wolfegg anthology, which was discovered in 1901 by Joseph Fischer in the princely library of Waldburg Wolfegg in Upper Swabia. Waldseemüller is mentioned as the author of the map in a text inscription in the lower left corner. The printing location is specified as St. Dié. Aside from Waldseemüller’s two maps, the Wolfegg Codex also contained a star chart, drawn by Albrecht Dürer, by Johannes Stabius and Conrad Heinvogel, as well as the strips of a celestial globe by Johannes Schöner. The ex libris refers to this very Johannes Schöner, a student of Waldseemüller and an important cartographer and astronomer in the sixteenth century, as the original owner of this anthology. The Carta marina, like its famous predecessor, consists of twelve woodcut sheets. The second sheet of the central zone is included twice in the Wolfegg Codex. The paper exhibits a three-pronged crown as a common watermark on both maps. By contrast, the inserted, duplicate sheet features an anchor surrounded by a circular line as a watermark. See also Fischer and Wieser (Citation1903, pp. 3–5).

9. This absolutely remarkable fact was also noticed at the time by Joseph Fischer and Franz von Wieser, who expressed their astonishment in the following way: Most radical of all is the diversity in the representation of southern Asia. In particular the two Indian peninsulas here present themselves in outlines, which approach the actual state of things in a very satisfactory manner. The question now arises, how is the radical difference in the representation of the two large Waldseemüller maps of the world to be explained? See also Fischer and Wieser (Citation1903, p. 23).

10. The translation of the title reads The well-known places from which the spices are brought to Calicut, the most famous transshipment hub.

11. The only meaning attributed by van Duzer to the magnifying glass effect produced by the omission of several degrees of longitude is that this provided Waldseemüller with more space for inserting his expanded cartographic knowledge through texts, place names and mountains—which, again, constitutes a purely descriptive approach that does not make an intellectual connection to the semantics behind the cartographic representation of the Carta marina. At a certain level, this assertion may very well be true, yet it ignores the fact that Waldseemüller did not have to depict the Indian Ocean based on Ptolemaic specifications in his earlier map from 1507, since at that point in time he was already aware of the course of the Indian coastline, and of the two peninsulas protruding into the Indian Ocean from the Caveri map. Aside from that, the high degree of similarity between the Caveri map and the Carta marina does not necessarily mean that the two cartographers had the same intentions. See also Van Duzer (Citation2012, pp. 14–17).

12. One particularly impressive example of these types of portolan charts is the Catalan World Atlas—dating from around 1375—prepared by Abraham Cresques and his son, Jehuda Cresques, on Mallorca, and presented as a gift to the French King Charles V, which shows the known world at the time from the Atlantic Ocean to China.

13. If Ptolemy’s claims in his Geographia are to be believed, experiments with this map design go back at least as far back as Marinus of Tyre. See also Stückelberger and Grasshoff (Citation2006, pp. 108–111).

14. See also Wagner (Citation1962, p. 72).

15. See also Müller and Krauss (Citation1983, p. 34).

16. See also Wagner (Citation1962, p. 71).

17. Going beyond the findings established here, it cannot be ruled out that Waldseemüller placed his only length-preserving parallel in the geographic latitude where the Spice Islands are located in order to minimize the distortion generated for these politically relevant areas. Unfortunately, however, since there is no reference text for the cartographic representation, this cannot be determined solely based on the map face of the Carta marina. It is also not possible to perform a comparison with Ptolemaic coordinates, at least for these areas located far to the south, because they were not shown by Ptolemy.

18. The translation of the text reads The victory of the most Christian King Manuel of Portugal. An interesting counterpart to this representation of the Portuguese claim to power on the Carta marina can be found in a letter addressed to Maximilian I of Habsburg by the Portuguese King Manuel I, where the latter chooses to use the proud and pompous title of “King of Portugal and the Algarves and of both sides of Africa, Lord of Guinea and of Conquest, Navigation, and Commerce of Ethiopia, Arabia, Persia, and India. See also Krendl (Citation1980, p. 2).

19. When the citizens of Bruges rebelled against Maximilian’s regency on behalf of his son Philip the Handsome and took Maximilian captive in 1488, the Portuguese king John II reacted immediately by canceling all festivities in Portugal, wearing mourning clothes and sending an embassy to France in order to negotiate Maximilian’s release. See also Krendl (Citation1982, p. 169.)

20. See also Wiesflecker (Citation1986, p. 448).

21. See also Krendl (Citation1982, p. 172).

22. See also Wiesflecker (Citation1986, pp. 448–449).

23. See also Hieronymus Münzer to King John II of Portugal, in: Stauber (Citation1908, p. 251): Considerans hec invictissimus Romanorum Rex Maximilianus matre Portugalensis, voluit epistola mea quamvis rudi maiestatem tuam invitari ad querendum [sic!] orientalem Cathaii ditissimam plagam. […] confitentur inquam principium orientis habitabilis satis propinquum esse fini occidentis habitabilis.

24. See also Wiesflecker (Citation1986, p. 449). If we were to draw on papers dealing with the so-called Politica del segredo—see also Cortesão (Citation1973)—it is more than likely that the Portuguese secretly sent ships around the Cape of Good Hope to India as early as 1493 and also sent scouts to India by land in complete secrecy to investigate where the spices originated from. See also Krendl (Citation1980, pp. 11–12). In fact, the concerns expressed by Maximilian in 1493, as mentioned by Wiesflecker, only became relevant for the Portuguese king in 1506. See also Note 3.

25. See also Krendl (Citation1980, p. 11).

26. See also Wiesflecker (Citation1986, pp. 449–450).

27. See also Krendl (Citation1982, p. 180).

28. See also Kellenbenz (Citation1990, p. 49). Antwerp had taken over the function of Europe’s largest center for the storage and distribution of goods since around 1480. See also Schmitt (Citation1997, p. 9).

29. See also Wiesflecker (Citation1986, p. 449).

30. See also Grosshaupt (Citation1990, p. 370).

31. See also Cassel (Citation1771, p. 11): 30 August 1509: King Emanuel of Portugal grants even more freedoms and privileges for 15 years to German merchants living in Lisbon, as well as pp. 15–16: 22 January 1510: Emanuel, King of Portugal, grants citizenship of the city to the German merchants living in Lisbon. The entire volume describing the privileges is available at the permalink: http://mdz-nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb10955760-0.

32. See also Kellenbenz (Citation1990, p. 50).

33. See also Kellenbenz (Citation1990, p. 10).

34. The Fugger family had acted with foresight and entered the Upper Hungarian copper mining industry as early as 1494 while securing the services of Johann Thurzu, a mining specialist from Krakow. New mining techniques, which made it easier to separate silver ore from copper ore, and improved pumping equipment, which permitted mining operations at greater depths, required large investments that could only be provided by a large trading company such as that of the Fuggers. See also Kellenbenz (Citation1990, p. 10).

35. See also Häberlein (Citation2006, pp. 40–47).

36. Ulrich Fugger provided financial support to emperor Friedrich III for the courtship of his son Maximilian as early as 1473, for which the Fugger family was granted the right to bear a coat of arms—according to the statements in the “Secret Book of Honor” of the Fugger family—and subsequently, this branch of the family later became known as “Fuggers of the Lily”.

37. See also Wiesflecker (Citation1986, p. 588).

38. See also Wiesflecker (Citation1986, p. 586).

39. In 1506, Jakob Fugger received the castle and manor of Schmiechen in Swabia as pledge for a loan to Maximilian; just one year later, the settlements of Buch, Weißenhorn and Marstetten were also pledged to Jakob Fugger.

40. See also Wiesflecker (Citation1986, p. 586). See also (Pölnitz, Citation1949, p. 304) and (Pölnitz & Fugger, Citation1951, p. 316).

41. Freiburg City Archive, A1 XI. Judicial system e. Criminalia 6 July 1492.

42. See also Tom Scott, “The Walzenmüller Uprising” 1492, Burgher Opposition and City Finances in Late Medieval Freiburg in Breisgau, in: “Schau-ins-Land”, Journal of the Breisgau History Association, Issue 106 (Scott, Citation1987), p. 69–93.

43. See also: Felix Heinzer, Gregor Reisch and his Margarita Philosophica, in Heinz Krieg, Frank Löbbecke and Katharina Ungerer-Heuck (ed.), The Charterhouse St. Johannisberg in Freiburg in Breisgau, Freiburg i. Br. 2014, p. 113–125. Evidence for Wimpfeling’s high opinion of Reisch is found in Wimpfeling’s letter to the imperial secretary Jakob Spiegel after the death of Maximilian I in 1519: Quis in omnia philosophia et in divinis literis acutior Gregorio Rieschio Carthusiano?, from: Jacobi Wimpfelingi opera selecta, ed. Otto Herding/Dieter Mertens, Dieter Mertens, vol. III, sub-volume 2, correspondence, Munich 1990, letter 339, p. 835.

44. At the time, the Duchy of Lorraine under René II was part of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation.

References

- Cassel, J. P. (1771). Privilegia. Bremen: Verlag Jani und Meier.

- Cortesão, A. (1973). O mistério de Vaco da Gama. Lisboa: Junta de investigacoes do Ultramar.

- Fischer, J., & Wieser, F. (1903). The Oldest Map with the Name America from 1507 and the Carta Marina from 1516 of M. Waldseemüller (Ilacomilis). Amsterdam: Heatrum Orbis Terrarum LTD.

- Grosshaupt, W. (1990). Commercial relations between Portugal and the merchants of Augsburg and Nuremberg. In J. Aubin (Ed.), La decouverte, le Portugal et l’Europe, Actes du Colloque Paris, les 26, 27 et 28 mai 1988 (pp. 359–17). Paris: Fondation Calouste Gulbenkian, Centre culturel portugais.

- Häberlein, M. (2006). The Fuggers, History of an Augsburg Familiy (1367-1650). Stuttgart: Wilhelm Kohlhammer.

- Heinzer, F. (2014). Gregor Reisch and his Margarita Philosophica. In H. Krieg, F. Löbbecke, & K. Ungerer-Heuck (Eds.), The Charterhouse St. Johannisberg in Freiburg in Breisgau, Stadtarchiv Freiburg im Breisgau (pp. 113–125).

- Herding, O., & Mertens, D. (ed.). (1990). Jacobi Wimpfelingi opera selecta, vol. III, subvolume 2, correspondence. Wilhelm Fink, München.

- Hessler, J., & van Duzer, C. (2012). Seeing the World Anew: The Radical Vision of Martin Waldseemüller’s 1507& 1516 Worl Maps. Washington, DC: Levenger press.

- Kellenbenz, H. (1990). The Fuggers in Spain and Portugal until 1560, A Large Enterprise of the 16th century, part 1. Ernst Vögel, München.

- Krendl, P. (1980). A New Letter about the First Trip to India of Vasco da Gama. Announcements of the Austrian State Archives, 33, 1–21. Ferdinand Berger & Söhne, Wien.

- Krendl, P. (1982). Emperor Maximilian I and Portugal. In H. Flasche (Ed.), Essays on the Portuguese Cultural History, vol. 17, 1981/1982 (pp. 165–189). Aschendorff, Münster/Westfalen.

- Lehmann, M. (2013). Amerigo Vespucci and his alleged awareness of America as a separate landmass. Imago Mundi, 65(1), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085694.2013.731201

- Lehmann, M. (2016). The depiction of America on Martin Waldseemüller’s world map from 1507 – Humanistic geography in the service of political propaganda. Cogent Arts & Humanities, 3(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311983.2016.1152785

- Müller, J., & Krauss, J. (1983). Navigation Handbook, 3 volumes, vol. 1, part A. Berlin: Julius Springer.

- Petrzilka, M. (1968). The Maps of Laurent Fries from 1530 and 1531 and their model, the Carta marina from 1516 by Martin Waldseemüller. Buchdruckerei der Neuen Züricher Zeitung, Zürich.

- Pölnitz, G. (1949). Jakob fugger. Emperor, Church and Capital in the Upper German Renaissance, 2. Tübingen: J. C. B. Mohr.

- Pölnitz, G. (1951). Jakob fugger Sources and comments, 2. Tübingen: J. C. B. Mohr.

- Schmitt, E. (ed.). (1984). Documents on the History of European Expansion, vol. 2, The Great Discoveries. C. H. Beck, München.

- Schmitt, E. (1997). Atlantic Expansion and Maritime Travel to India in the 16th Century. Abera, Hamburg.

- Scott, T. (1987). The Walzenmüller Uprising” 1492, Burgher Opposition and City Finances in Late Medieval Freiburg in Breisgau, in: “Schau-ins-Land. Breisgau History Association, 106, 69–93. Breisgau-Geschichtsverein Schauinsland, Freiburg im Breisgau.

- Stauber, R. (1908). Schedel’s Library, Freiburg i. Br. Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau.

- Stückelberger, A., & Grasshoff, G. (ed.). (2006). Claudius Ptolemy, Handbook of Geography, 1st sub-volume. Schwabe, Basel.

- Van Duzer, C. (2012). Waldseemüller’s World Maps of 1507 and 1516: Sources and development of his cartographical thought. The Portolan, 85, 8–20.

- Wagner, K. (1962). Cartographic network designs. Bibliographisches Institut, Mannheim.

- Wiesflecker, H. (1986). Emperor Maximilian I, The Empire, Austria and Europe at the Beginning of the Modern Era, vol. 5, The Emperor and his Environment - Court, State, Economy. Society and Culture.