Abstract

The paper seeks to establish the role of religion and culture in the realization of women’s rights to property in Nigeria. It begins by affirming that protecting women’s rights to property in Nigeria is a fundamental step towards achieving the 5th Sustainable Development Goal of gender equality. The promotion and protection of these rights in any society are determined by several factors such as the customs, prevailing traditions, as well as the religious laws that control behavioral patterns in that society. In discussing this within the Nigerian context, the paper explores the tenets of Christianity and Islam that govern women’s rights to property. The study used secondary data derived from articles that were sourced from Google Scholar. A total of nine articles was reviewed. The paper reveals that, culturally, women are viewed as inferior to men, and a male-child is generally celebrated and allotted higher portions of properties. However, the tenets of both Islam and Christianity do not disregard the woman in terms of property rights. The authors suggest that the prevailing discrimination against women has no religion backing, but a misguided exploitation of the low educational status of women in Nigeria.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Rights to property is a major element in the empowerment of women globally and the pursuit of gender equality. In other words, these have been one of the focal points of global efforts at enhancing the lives of women. However, despite several treaties that have been adopted, signed and ratified by individual nation-States for the protection of women’s rights, women are still subjected to varying degrees of discrimination on the grounds of religion and culture. It is therefore pertinent to assess the influence of these two variables on the property rights of women in Nigeria.

1. Introduction

Despite the growing global concerns for, and efforts at protecting women’s rights to land and other tangible assets that possess economic value, various studies reveal that, women still encounter challenges with respect to these rights (Adekile, Citation2010; Folarin & Udoh, Citation2014; Aluko, Citation2015; Anyogu & Okpalobi, Citation2016; Akinola, Citation2018; Chaves, Citation2018). Globally, land and other forms of real property are essential for the economic empowerment of women across different cultural contexts (Gottlieb et al., Citation2018). Land in particular serves as a crucial element for cultural identity (George et al., Citation2015), participation in decision-making, political power and protection against domestic violence. It is against this backdrop that, various institutions, human rights’ activists and feminists across the world moved for the codification and implementation of laws that protect women’s rights generally and more specifically, ensure women’s rights to acquire, inherit, use, control, or dispose economic assets. These international legal provisions eventually became international treaties under the auspices of the United Nations. Notable among the treaties is the 1979 Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) which viewed discrimination against women as an act against human dignity and outlined the responsibility of state-parties in ensuring the protection of women. As at May 2015, a total of one hundred and eighty-nine states had signed and ratified the treaty—a commendable response which indicates the willingness and commitment of state-parties to promote gender equality and eradicate all forms of discrimination against women. In addition to this, the Sustainable Development Goal 5 aims to achieve gender equality and empower women and girls. It aims at undertaking reforms that will ensure that women have, equal rights to economic resources, access to ownership and control over land and other forms of property and inheritance in accordance with national legislations (Food and Agriculture Organisation, Citation2018).

However, regardless of this global commitment to eradicate gender disparity or discrimination and promote women’s rights generally, women are still either marginalized or denied access to real property (Stichter & Parpart, Citation2019). For instance, Agarwal (Citation1994) posits that the most important economic challenge that affects women is the gender gap in the control of land while a report from the World Bank (Citation2019) reveals that women in half the world are denied land and property rights. Lack of protecting their rights to property, among other things, hinders their access to credits and loans from financial institutions as these assets could serve as collateral. Furthermore, the far-reaching effects of violating women’s rights to property, especially land, include the feminization of poverty (rising level of poverty among women) (Agarwal, Citation1994; Le Beau et al., Citation2004) and increase in incidences of gender-based violence. In addition, it has been revealed that until gender equality includes land rights and ownership, the agenda for Sustainable Development in 2030 would become impossible because landlessness is “among the best predictors of poverty” (United Nations, Citation2018). A number of factors has been attributed to the violation of women’s rights to property. Some scholars (Akinola, Citation2018; Le Beau et al., Citation2004; George, Citation2010; Kalabamu, Citation2000) assert that patriarchal systems and institutions are the underlying causes of the denial and discrimination that women experience with respect to their rights to property and inheritance in general, while others opine more specifically that, religion (Obioha, Citation2013), customs and traditions (Benschop, Citation2004; George et al., Citation2015; Obioha, Citation2013) are causal factors in the violation of women’s rights which cannot be over-emphasised.

Religious doctrines and cultural norms are two forces that bear overwhelming influence on human rights, generally (Abdulla, Citation2018). As a matter of fact, all the major religions in the world share a “universal interest and tradition of respecting the integrity, worth and dignity of all persons and consequently, the duty towards other people who suffer, without distinction” (Lauren, Citation1998, p. 5). It is vital to mention that the religious ideas of protecting human dignity eventually provided the philosophical base upon which international human rights’ law was established. To support this claim, Rieffer (Citation2006) asserts that, early religious writings presented a moral code that contained the duties and responsibilities of all peoples and, also promoted the initial discussions about rights (Lauren, Citation1998, p. 9 as cited in Rieffer, Citation2006). These early religious writings and moral code of conduct formed the foundation of the idea and concept of human rights, which was eventually ratified and incorporated into international law in the twentieth century.

Culture, generally on the other hand, recognises human rights by identifying notions of human feelings, empathy, intuitions and concerns toward specific groups of others (Hunt, Citation2007). However, different customs and traditions, which reflect various cultures across the world, have to a large extent affected the promotion and protection of the notion of women’s rights. To be more precise, it has been argued that culture is often used as a tool for justifying the violations of women’s rights especially in the areas of marriage and property, reflecting deep-seated patriarchal structures and harmful gender stereotypes. Nevertheless, culture is not an unchanging concept that cannot accommodate current realities (United Nations Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights, Citation2016). Therefore, despite comprehensive international and national legislations and policies that prohibit discrimination and inequality on the grounds of sex/gender, women still experience systematic denial and marginalisation with respect to property rights and which are as a result of patriarchal standards that have filtered into different cultures. No wonder Okin (Citation1999) notes, many cultures in the world promote the control of women by men.

2. Methods and materials

2.1. Search strategy and selection criteria

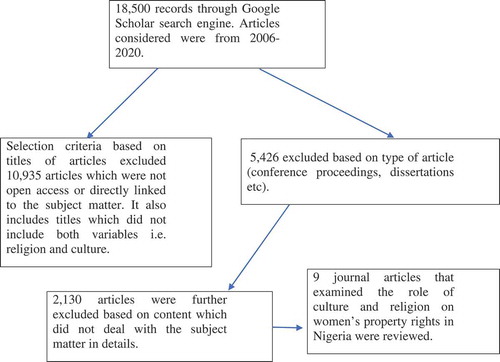

This paper employed a systematic review of extant cross-sectional studies that examined women’s rights to property inheritance in Nigeria. Related articles were sourced from the Google Scholar search engine. The search terms used were women’s rights to property, property rights of women in Nigeria, inheritance rights, religion and women’s rights to property, culture and rights to property in Nigeria, Christianity and women’s rights to property and inheritance in Nigeria and Islam and women’s rights to inheritance in Nigeria. The period of study was set to a custom range of year 2006 to 2020. A total of 18,500 studies was identified and followed by the screening and selection phases. Subsequently, the criteria for exclusion and inclusion was designed for the final selection of papers. First, only articles that examined the role of religion and culture on women’s rights to property in Nigeria were considered. Also, conference papers, books, dissertations and articles that were not open access were excluded. In addition, articles that examined the role of culture and religion on other aspects of women’s rights were not included. Hence, with the selection criteria mentioned above, only nine (9) studies published from 2006 till date were considered.

3. Results

Following a systematic selection of articles for review, a total of nine journal articles, published from 2006–2020, were reviewed for the study. The journal articles focused mainly on the role of religion and culture in the promotion and protection of women’s rights to property and inheritance in Nigeria. The study covered only the two major religions in Nigeria, namely, Christianity and Islam.

In Nigeria, culture and religion determine societal beliefs, norms and attitudes towards women despite the provisions of civil laws and international treaties. According to Abara (Citation2012), culture indeed has a pervasive influence on women’s rights in Nigeria. To corroborate this claim, he asserts that in North-East Nigeria, only 4% of land is owned by women while in the South-East and South-South geopolitical zones of the country, they own just over 10% of land. The reasons for this are anchored on customary laws. It is important to mention that inheritance rights differ across the country, given the fact that it is a heterogeneous country with many cultures. Nevertheless, a major feature in inheritance laws across the different cultures is that there is discrimination against women in property sharing (Abara, Citation2012, Ekhator, Citation2018). The role of religion and culture in protecting women’s rights to property in Nigeria will be discussed independently, subsequently.

Nigeria is made up of 36 states—19 states in Northern Nigeria and 17 states in Southern Nigeria. The country is made up of three major religions, namely, Christianity, Islam and African Traditional Religion (ATR). Nonetheless, it is almost generally accepted that Islam is the dominant religion in the Northern part of the country while Southerners are predominantly Christians; only a small percentage practice the third religion. For this study, the focus will be on two out of the three major religions—Islam and Christianity—because they, like most institutions, have larger followership and stronger influence on Nigeria’s socio-political and socio-cultural systems.

4. Religion and women’s property rights in Nigeria

Islam, usually referred to as one of the Abrahamic faiths, has a large followership of about 50% of the Nigerian population (Central Intelligence Agency World Factbook, Citation2001). Needless to state that Islam is a powerful religious force that shapes the socio-political and socio-ethnic milieu of the Nigerian society. Introduced into the Northern Nigeria in the 11th century, Islam is an Arabic word that means surrender to God or submission to the will of God (Honarvar, Citation1988). Islamic laws (otherwise, referred to as Shari’a) which are described as one of the world’s greatest legal systems (Constitutional Rights Foundation, Citation2018) border on the principles for the establishment of peace and order, improving the status of women and addressing the question of inheritance and succession on equitable grounds. Also, it propagates the principle of equality of all humans while shunning all inequalities due to sex, race or nationality (Sait & Lim, Citation2006) since all humans (whether male or female) are created from the same soul. According to Baer (Citation1983 as cited in Sait and Lim Citation2006), historically, Muslim women were holders of property. In fact, under Islamic laws, a Muslim woman possesses individual legal and economic identity; she also has independence with regards to her access to land under Qur’anic injunctions. Sait and Lim (Citation2006) further emphasize that Islamic substantive law, contained in the Holy Qur’an recognizes women’s rights to acquire or utilize property through purchase or inheritance from husband. In other words, under Islamic laws, women have some degree of control over assets they purchase from their personal treasury or received from their parents before marriage or as gifts (mahr) from their husbands upon marriage. This ensures some level of financial independence and security for her.

Nevertheless, her rights to inheritance under the Islamic legal system are limited. While the Qur’an makes provision for women’s rights to property and inheritance, the general rule is that her share is half her male counterpart’s share in inheritance. To put it more aptly, a daughter is only entitled to half of her brother’s share of inheritance. Nevertheless, she has absolute powers over whatever she gets by her labour or inheritance. This inequality is drawn from the assumption that the man has more financial obligations towards the woman and those obligations exceed the woman’s. For instance, upon marriage, he is expected to present his wife with a marriage gift, mahr, (this could be an asset) which is her own property that cannot be taken away from her. In addition, the Muslim husband has the responsibility of maintaining his wife and children. The Muslim wife, on the other hand, has no responsibility of such; whatever asset or financial wealth she has belongs to her. Under Islamic law she is not obliged to co-provide for her family except she volunteers to do so. This is the same reason why a daughter from a Muslim family does not inherit property on equal terms with her male counterpart. The question to be asked here however is, what happens to an unmarried woman who chooses not to marry? When a situation like this arises, the woman is discriminated against based on religious assumptions and contrary to provisions made in international human rights’ regimes. It should be noted that traditional (or customary) practices amplify this discrimination.

After the death of a husband, the wife (with children), on the other hand, inherits one-eighth of the deceased’s property; and if she is without children, her portion is one-fourth. Also, a mother has the right to inherit from her dead son. In Northern Nigeria where the population therein are predominantly Muslims, these religious laws are followed precept by precept except in cases where customs superimpose the provisions of the Qur’an. Therefore, a cursory examination of the Islamic law (or Shari’a law) reveals that Muslim women can acquire or purchase any form of property, and discriminated, on the other hand, with respect to their rights to inheritance.

Christianity, which is the second Abrahamic faith, with a population percentage of 40% in Nigeria (Adewole, Citation2017; Central Intelligence Agency World Factbook, Citation2001), is the predominant religion in the Southern region of the country. As a religion, Christianity was introduced in Nigeria in the 15th century by the activities of European missionaries and has ever since spread throughout the country with an overwhelming influence in the behavioural patterns and constitutional laws of the country (Kolapo, Citation2019). Put differently, it is a vital text upon which many now base their entire lives.

Like any other religion, Christians (followers of Jesus Christ) are guided by their religious laws which are well documented in the Holy Bible. The Holy Bible contains direct injunctions and instructions from God, as received by His prophets, on how His followers are expected to behave; and also, teachings from Jesus Christ and His apostles. This body of laws is generally divided into and commonly referred to as the Old and New Testaments. For the purpose of this study, the focus will be on the Torah (Hebrew word for “the Law of God”) which is a subset of laws found in the Old Testament. The Torah is a collection of the first five books of the Bible which were given to Moses (Saperstein, Citation2019), as a body of rules or commandments, for the people of ancient Israel (often called the Israelites). Therefore, historically, the Torah was to shape and govern the lives of the Biblical Israelites. Either from the old or new testament or Torah, no scholars laid claim to any discrimination against women in terms of properties inheritance (Naznin, Citation2014). It is very important to lay this foundation that equality among the creation has often been emphasised. Notwithstanding, women’s inheritance or laws regarding such have been subjected to different interpretations by theologians, scholars and by local traditions (Radford, Citation2000). It is also very crucial to note that, the prevailing societal legal systems of those periods were instrumental in the interpretation of these laws (Radford, Citation2000).

Critical review of the religious books also supported women’s rights to property and inheritance. For instance, in ancient Israel, the Jewish land was allotted to male heads of households, in different tribes, who also transferred such allotments in patrilineal patterns (Case, Citation2020; Murray, Citation1998; Shemesh, Citation2007; Verburg, Citation2019). However, where there was no male head, like Zelophehad case, lands were allotted to daughters (Case, Citation2020; Murray, Citation1998; Shemesh, Citation2007; Verburg, Citation2019). While women’s denial to own property has not been exhaustively established or supported scripturally, there are also no scriptural reference that presents women (wives, daughters or sisters) as property to be owned or transferred as property (Hiers, Citation1993) contrary to the practices across different cultures, over centuries (Engineer, Citation2008). Nevertheless, the Torah has only few instances of daughters inheriting from their fathers but replete with various accounts of sons—eldest sons, in most cases—inheriting their fathers’ tribal property. In addition, widows’ rights to property appear to be protected biblically. This was clearly depicted in Ruth’s account where it was alluded that she intended selling the land that belonged to her late husband (Lakama, Citation2019). As an old widow without sons to inherit her, the intent to sell the land presupposes that she had exclusive rights over the inherited land upon the death of her husband (Hiers, Citation1993; Lakama, Citation2019). Other scriptural references corroborate the recognition, promotion and protection of widows’ rights to property and inheritance (Hiers, Citation1993; Lakama, Citation2019). Hence, the Torah, as spoken by God, does not discriminate against women or deny them of their rights to own property or inherit. Interpretations based on Jewish culture and fostered by patriarchal norms rather affected the implementation of the written laws (Radford, Citation2000). It is noteworthy to mention that, although these laws were expected to regulate the affairs of the Jews, it is the foundation of Christian laws.

Within the Nigerian context, various Christian leaders have been able to condemn discriminatory laws that impede women’s access and ownership rights (Williams et al., Citation2020). Nevertheless, customs and traditions still prevail over laws of intestate succession as Christian laws are viewed by some traditional societies as foreign to the Nigerian culture. Also, the secularity of the country poses a challenge to the overarching influence of religious laws.

5. Culture and women’s property rights in Nigeria

Women’s experiences in acquiring or inheriting land and other property in Nigeria are filled with narratives of denial and marginalization (Ajayi & Olotuah, Citation2005). Being a culturally diverse country with well over two hundred and fifty (250) ethnic groups—that are divided into three major ethnic groups (the Igbo, the Hausa and the Yoruba ethnic groups)—patriarchal customs and traditions appear to be a recurring factor that unifies the experiences of their female population (Ekhator, Citation2018).

In furtherance to the above, Ajayi and Olotuah (Citation2005) aver that women’s rights to property and inheritance are restricted within the natal and matrimonial families. In most Nigerian families, the natal family lays the foundation for sex-preference. The birth of a son is usually celebrated more than that of a daughter because, above all, a male child guarantees the continuation of the lineage. The female children suffer real discrimination in terms of inheritance after the demise of their father. For instance, among the Igbo and some subcultures within the Yoruba ethnic group, girls are not entitled to have a share in inheritance at all. The first son receives a greater share than the first daughter among the Akure indigenes (Ajayi & Olotuah, Citation2005). For the Bini and Ishan people of Edo state, the oldest son inherits all the father’s property leaving the female child with nothing; the Hausa folks, on the other hand, operate according to Shari’a laws which give twice the daughter’s portion to her brother. Within the matrimonial family, the ability to enjoy certain rights to property depends on several factors. One of such factors is the woman’s capacity to have children in her husband’s house. Traditionally, women are perceived to be sole reasons for their childlessness even though science has proven that in many cases, men could also be responsible. In fact, a woman may be labelled a witch if she cannot bring forth children. In the event of childlessness, such women are denied their rights to inheritance after the death of their husbands.

For instance, in Edo state, Ajayi and Olotuah (Citation2005) reveal that, even when a childless woman is wealthy and supports her husband in acquiring certain properties, like land or buildings, her in-laws could mount pressure on her husband to divorce her due to her childlessness. The situation would become more precarious when the property which was jointly owned is registered in the husband’s name with no legal or acceptable evidence of the woman’s contributions. That leaves her with nothing since the property is not legally hers. It is not different when she has children and is divorced. Divorce leaves most uneducated women with nothing other than their personal belongings like clothing, jewelry and maybe kitchen utensils. That is why some Nigerian women prefer to acquire property in their fathers’ names. In other cases, the woman and all she owns are considered the man’s property to be administered whichever way he deems (Ajayi & Olotuah, Citation2005). Also, widowhood practices against women in Nigeria put the widow in a disadvantaged position during property sharing. In most cases, a widow may be denied access to her late husband’s property and in other circumstances, she is considered part of the property to be shared among old or young male relatives. Among the Igbo, some family members demand an instant inventory of all the husband’s assets while demanding that the widow swears an oath of honesty. For the Etulo and Idoma tribes in Benue, property sharing is done along matrilineal and patrilineal lines of the deceased man, respectively. For the Etulo, the implication is that, when a man dies, his property is transferred to the maternal relations of the man who decides whether to give the widow and what should be given to her. Needless to say, that among this tribe, a barren widow has no right of inheritance (George, Citation2010). Among the Northerners in Kano state, a widow inherits one-eighth (⅛th) of the deceased husband’s property in accordance with Shari’a law.

Hence, drawing from the above, culture and religion are two important factors that are often invoked as a justification for the violation of women’s rights generally. In most patriarchal societies, it is often difficult to separate both factors as both are used to support each other even though, they are separable. Put differently, Christianity and Islam are not the main reasons behind discrimination in the country. As a matter of fact, both religions made provisions for inheritance before the Western notion of women’s rights to property was introduced (Lakama, Citation2019; Sait & Lim, Citation2006). Although the two religions do not make well-articulated provisions or codified laws for the protection of women’s rights to property, it can be inferred from the different religious texts that embody the laws of these religions (the Holy Bible and the Qu’ran) that discrimination on the grounds of gender is outlawed. Culture still has an overwhelming influence on how women benefit from property sharing and ownership.

6. Discussion

Islam and Christianity promote the protection of women considering the responsibilities they bear and their tenderness. Islamic laws do not prohibit women from buying any form of property or inheriting from their husbands and parents. However, it was discovered that property sharing in a Muslim family appears to be one-sidedly skewed in favour of the male-child on account that as a man, he bears more responsibility which includes his wife’s. Therefore, a twist to the argument on (discriminatory) Islamic laws on inheritance is that the man gets more share because of his familial responsibilities. Besides this, a Muslim woman can purchase any property from her personal wealth. Judeo-Christianity, on the other hand, does not have specific provisions on women’s rights to property except for few instances where women were permitted, either to inherit their father’s portion of allotted land or sell deceased husband’s property. Therefore, religion on the matters of women’s rights to property is not a factor that engenders discrimination against women. The patriarchal traditions in Nigeria are responsible for the overall discrimination that women experience within the country with respect to their rights to property. A major finding of this study is that cultural interpretations are usually given to religious dogma in order to suit societal expectations of women.

Culture, on the other hand, discriminates against women in the country (Aluko, Citation2015; Ekhator, Citation2018). It is evident in literature on women’s property rights that in some communities, women cannot own land (Ekhator, Citation2018; Oyelade, Citation2006) or other immovable properties except through the intervention of male relatives. As a matter of fact, when she eventually buys a property, as a responsible woman, she is expected to get her husband’s consent before making any decision on the property (Udoh, Citation2020). In other communities in Nigeria, women cannot inherit their deceased husband’s or father’s estate largely because of son/male preference. In situations where the deceased has no male child, his closest male relative takes over his property rather than his daughters and when she is considered in property sharing, she will not get an equal share with her brother because it is believed that she will be cared for in marital family (Udoh, Citation2020).

7. Conclusion and recommendations

The study concludes that religion and culture influence societal behaviour, attitudes and perceptions towards women. On one hand, religion makes provision for women’s rights to acquire, use or inherit property, while, on the other hand, culture discriminates against them in Nigeria and Africa, as a continent (Adekile, Citation2010). Nevertheless, women’s rights generally can be strengthened and further protected when religious leaders re-orientate the minds of their followers through doctrines and tenets contained in the religious texts. Through the doctrinal teachings of religious leaders that emphasize the equality of all beings, regardless of gender, the human mind will be conditioned to overcome and abolish patriarchal, cultural systems.

Acknowledgements

This is to affirm that this article is a part of an ongoing doctoral thesis of Oluwakemi Udoh titled, the International Conventions on the Elimination of Gender-Based Cultural Discrimination and Women’s Property Rights in Ogun State, Nigeria (2020). Sincere appreciation goes to the co-authors (Professor Sheriff Folarin and Professor Victor Isumonah) of the paper who are also the supervisors of the doctoral candidate, for their immense contributions to the entire work. Finally, the author appreciates Covenant University Centre for Research, Innovation and Development (CUCRID) for sponsoring the publication of the paper in Cogent Arts and Humanities Journal.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Oluwakemi D. Udoh

Oluwakemi Udoh is a lecturer and currently pursuing a doctorate degree in International Relations at Covenant University. Her research interests are in human rights, gender studies, religious politics, the effectiveness of international law in ensuring a just world order and most recently, Artificial Intelligence.

Sheriff F. Folarin

Sheriff Folarin is the Head, Department of Political Science and International Relations in Covenant University, Nigeria and a Fulbright Scholar with several publications in peer-reviewed high impact journals. His major research interests are in foreign policy.

Victor A. Isumonah

Victor Isumonah is the Head, Department of Political Science in the University of Ibadan, Nigeria. He is a seasoned scholar with many publications in reputable journals.

References

- Abara, C. (2012). Inequality and discrimination in Nigeria tradition and religion as negative factors affecting gender. Federation of International Human Rights Museums. Pp. 1-18. Retrieved from https://www.fihrm.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Chinwe-Abara.pdf

- Abdulla, M. (2018). Culture, religion, and freedom of religion or belief. The Review of Faith and International Affairs, 16(4), 102–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/15570274.2018.1535033

- Adekile, O. (2010, May 26). Property rights of women in Nigeria as impediment to full realisation of economic and social rights. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.10.2139/ssrn.1616270.

- Adewole, A. M. O. (2017). The role of church influence and social context on selected pentecostal christians in the political leadership of Nigeria. Fuller Theological Seminary, School of Intercultural Studies.

- Agarwal, B. (1994). Gender and command over property: A critical gap in economic analysis and policy in South Asia. World Development, 22(10), 1455–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(94)90031-0

- Ajayi, M., & Olotuah, A. (2005). Violation of women’s property rights within the family. In Agenda: Empowering women for gender equity. Gender-Based Violence Trilogy Volume 1. No 66. Taylor and Francis, 58–63.

- Akinola, A. (2018). Women, culture and Africa’s land reform Agenda. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 22–34. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02234

- Aluko, Y. Patriarchy and property rights among Yoruba women in Nigeria. (2015). Feminist Economics, 21(3), 56–81. Taylor and Francis Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2015.1015591

- Anyogu, F., & Okpalobi, B. (2016). Human right issues and women’s experiences on demanding their rights in their communities: The way forward for Nigeria. European Center for Research Training and Development.

- Baer, G. (1983). ‘Women and waqf: An analysis of the Istanbul Tahrir of 1546. Asian and African Studies, 17(1), 9–28.

- Benschop, M. (2004). Women’s rights to land and property. In Women in human settlements development: Challenges and opportunities. Commission on Sustainable Development, UN- Habitat, 1–7.

- Case, M. (2020). Inheritance injunctions of Numbers 36: Zelophehad’s daughters and the intersection of ancestral land and sex regulation. Sexuality and Law in the Torah. Bloomsbury Publishing, 194.

- Central Intelligence Agency World Factbook. (2001). Religions. Retrieved October 23, 2018, from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/fields/2122.html#ni

- Chaves, P. (2018). What do land rights mean for women? Five insights from Brazil. The World Bank Group. http://blogs.worldbank.org/latinamerica/what-do-land-rights-meanwomen-five-insightsbrazil

- Constitutional Rights Foundation (2018, October 23). The origins of Islamic law. http://www.crf-usa.org/america-responds-to-terrorism/the-origins-of-islamic-law.html

- Ekhator, E. (2018). Protection and promotion of women’s rights in Nigeria: Constraints and prospects. In Women and minority rights law: African approaches and perspectives to inclusive development (forthcoming). Eleven International Publishing, 17–35.

- Engineer, A. (2008). The rights of women in Islam. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

- Folarin, S., & Udoh, O. (2014). Beijing declaration and women’s property rights in Nigeria. European Scientific Journal, 10(34), 239–249.

- Food and Agriculture Organisation. (2018). Realizing women’s rights to land in the law.

- George, T. (2010). Widowhood and property inheritance among the Awori of Ogun State, Nigeria [ Unpublished doctoral thesis]. Covenant University.

- George, T., Olokoyo, F., Osabuohien, E., Efobi, U., & Beecroft, I. (2015). Women’s access to land and economic empowerment in selected nigerian communities. N. Andrews. Springer, Cham.

- Gottlieb, J., Grossman, G., & Robinson, A. (2018). Do men and women have different policy preferences in Africa? Determinants and implications of gender gaps in policy prioritization. British Journal of Political Science, 48(3), 611–636. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123416000053

- Hiers, R. (1993). Transfer of property by inheritance and bequest in biblical law and tradition. Journal of Law and Religion, 10(1), 121. https://doi.org/10.2307/1051171

- Honarvar, N. Behind the veil: Women’s rights in Islamic societies. (1988). Journal of Law and Religion, 6(2), 355. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/1051156

- Hunt, L. (2007). Inventing human rights: A history. W.W.Norton & Co.

- Kalabamu, F. (2000). Land tenure and management reforms in East and Southern Africa – The case of Botswana. Land Use Policy, 17(4), 305–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-8377(00)00037-5

- Kolapo, F. (2019). Christian missionary engagement in central Nigeria, 1857-1891: The church missionary society’s all-African mission on the upper Niger. Springer Nature.

- Lakama, Y. (2019). A comparative study of widowhood in ancient Israel (the Book of Ruth) and in Billiri society of Gombe State, Nigeria [ Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation].

- Lauren, P. (1998). The evolution of international human rights: Visions seen. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Le Beau, D., Iipinge, E., & Conteh, M. (2004). Women’s property and inheritance rights in Namibia. University of Namibia, Gender Training and Research Programme.

- Murray, V. (1998). A comparative survey of the historic civil, common, and American Indian tribal law responses to domestic violence. Okla, City UL Rev, 23, 433. Retrieved fromhttps://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/okcu23&div=23&id=&page=

- Naznin, S. (2014). Women’s inheritance and property rights in Pakistan. Journal of Law and Society, 45(65), 35–56. Retrieved from http://journals.uop.edu.pk/papers/65-2014-3.pdf

- Obioha, E. (2013). Inheritance rights, access to property and deepening poverty situation among women in Igboland, Southeast Nigeria [Paper presentation]. A sub-regional conference on gender and poverty organized by center for gender and social policy, IleIfe, Nigeria: Obafemi Awolowo University.

- Okin, S. (1999). Is multiculturalism bad for women?. Princeton University Press.

- Oyelade, O. (2006). Women’s right in Africa: Myth or reality. University of Benin Law Journal, 9(1). Retrieved from http://www.nigerianlawguru.com/articles/human%20rights%20law/WOMEN%92S%20RIGHTS%20IN%20AFRICA,%20MYTH%20OR%20REALITY.pdf

- Radford, M. (2000). The inheritance rights of women under Jewish and Islamic Law. Boston College International and Comparative Law Review, 23(2), 135. Article 2. http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/iclr/vol23/iss2/2

- Rieffer, B. (2006). Religion, politics and human rights: understanding the role of Christianity in the promotion of human rights. Human Rights and Human Welfare, 6, 31–42. Retrieved from http://catedra-laicidad.unam.mx/sites/default/files/Religionpoliticsandhumanrights.pdf

- Sait, S., & Lim, H. (2006). Land, law and Islam: Property and human rights in the Muslim world. Zed books.

- Saperstein, M. (2019). Benjamin Williams, commentary on Midrash Rabba in the sixteenth century: The Or ha-Sekhel of Abraham ben Asher. Oxford University Press.

- Shemesh, Y. (2007). A gender perspective on the daughters of Zelophehad: Bible, Talmudic Midrash, and modern feminist Midrash. Biblical Interpretation, 15(1), 80–109. https://doi.org/10.1163/156851507X168502

- Stichter, S., & Parpart, J. (2019). Patriarchy and class: African women in the home and the workforce. Routledge.

- Udoh, O. (2020). International treaties on the elimination of gender-based discrimination and women’s property rights in Ogun State, Nigeria [ An unpublished doctoral thesis]. Covenant University.

- United Nations. (2018). Gender equality in land rights, ownership vital to realising 2030 agenda, women’s commission hears amid calls for data collection on tenure security. un.org/press/en/2018/wom2143.doc.htm

- United Nations Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights. (2016). Women’s rights in Africa. Retrieved February 01, 2019, from https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Women/WRGS/WomensRightsinAfrica_singlepages.pdf.

- Verburg, J. (2019). Women’s property rights in Egypt and the law of the Levirate marriage in the LXX. Zeitschrift fur die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft, 131(4), 592–606. https://doi.org/10.1515/zaw-2019-4005

- Williams, C., Forbes, J., Placide, K., & Nicol, N. (2020). Religion, hate, love and advocacy for LGBT human rights in Saint Lucia. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 1–12. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13178-020-00429-x

- The World Bank. (2019). Women in half the world still denied land, property rights despite laws. worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2019/03/25/women-in-half-the-world-still-denied-land-property-rights-despite-laws