Abstract

This article studies the relationship between actors and audiences participation in theater, using the oft-compared Brechtian theater style, and the religious and ritualistic Passion play Ta’ziyeh. To investigate the similarities and differences between these two forms, the distancing or “V”- effect of Brechtian theater is compared to the dramatic value of distancing in conveying the strong moral principles associated with the traditional performance of Ta’ziyeh. To disprove the argued association between the two forms, to inform how modern theater-goers appreciate the influence of each form the objective of this paper is to provide a deeper and more culturally specific understanding of Ta’ziyeh’s engagement with reality and the symbolic, particularly with regard to the position of actors and audiences towards each other. To this end, the critical elements in both Ta’ziyeh and the Brechtian V-effect are comprehensively discussed.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The present study is a comparison between two historically forms of literature. It is compatible with that of some theoreticians who believe that Ta’ziyeh is a traditional, symbolic, and unrealistic form of theater, and fundamentally different from other theatrical styles. In other words, this study disproves the need to consider the Western style of V-Effect in reaction to the impersonation used in the ritualistic component of Ta’ziyeh when recognizing the dramatic value and integrity of the latter. Therefore, it is necessary to focus on the evaluation of traditional ceremonies in order to draw a comparison between such traditions and Brechtian theater, and conduct research accordingly.

1. Introduction

The present research examines the concept of distancing in Brechtian theatre and Ta’ziyeh, in order to reflect on the proclaimed similarities between the two and to shed light on their fundamental differences, particularly with regard to the role both actors and audience play in each respective form. To this end, the analysis takes up a culturally-specific understanding of each form from the viewpoint of actors and audience in order to understand how Brechtian theater and Ta’ziyeh engage reality and the symbolic in different ways.

This study is compatible with that of some theoreticians who believe that Ta’ziyeh is a traditional, symbolic, and unrealistic form of theater, and fundamentally different from other theatrical styles, including Brechtian theater. For example, in his book Philosophy and Religion in Central Asia, Count de Gobineau, as cited in Parvz Mamnoun, one of the first Western researchers of Ta’ziyeh in the mid-19th century, predicted a national-religious drama in the near future, whereby everyday Iranian human drama would draw on the influences of the Iranian religious theater. Mamnoun believes that what prompted Gobineau to make such a prediction about 120 years prior were the narrative prologues that open Ta’ziyeh performances (Mamnoun, Citation1968, p. 20). Mamnoun believes that reproducing Ta’ziyeh on the stage caused it has primarily been likened to Brechtian theater in terms of distancing technique. As he said “Ta’ziyeh did not seek to be realistic or achieve realism: the tragedy of Kerbela was so important to the Ta’ziyeh performer, so exceptional and extraordinary that it would have been impossible to show it realistically within the means and possibilities of performance, which are at best only a vehicle by which it is possible to show this tragedy but not to reproduce it” (Mamnoun, Citation1979, p. 157). He adds that “We must not forget that on the day when the Ta’ziyeh costumes are brand new and historically accurate; that day on which, God forbid, imaginative sets are used; that day on which realistic artists under the Ta’ziyeh and natural acting replaces the present ‘artificial’ gestures; that day on which the performance is removed from the platforms of the tekiyeh,Footnote1 from the bare fields of the villages, from the asphalt pavement of small towns, and is transferred to the boxlike stages from the beginning of the performance to the accompaniment of the usual mysterious dramatic music; that day, the day when Ta’ziyeh becomes realistic, will witness its death” (p. 159).

The present research intends to prove that the dramatic value and integrity of Ta’ziyeh are independent of the Western V-effect due to the ritualistic components of Ta’ziyeh. Ta’ziyeh has primarily been likened to Brechtian theater in terms of distancing technique, and so, the focus of this research will be to examine the traditional ceremonial aspects of Ta’ziyeh in juxtaposition to Brechtian theater.

Ta’ziyeh is a traditional Passion play portraying the death of Hussein, grandson to the Prophet Muhammad. The word “Ta’ziyeh” means “consolation,” and it signifies the blessing that performers are believed to receive in dramatizing the sacred events that befell the Prophet’s and imams’ family. It is a ritual performance, taking place during the month of Muharram. Thus, it is also called the Mourning of Muharram or the Remembrance of Muharram. Although Ta’ziyeh’s popularity began to fade in the twentieth century, it never diminished entirely. Though Ta’ziyeh is a traditional Persian play, it has been performed in many other countries, including Iran, India, Indonesia, Pakistan, and Iraq, often under different titles.Footnote2

Since Ta’ziyeh differs from other theatrical performances in some significant ways, using terminology such as “play” and “actor” may be misleading. In Ta’ziyeh tradition, performers are referred to as shabih (performer), Ta’ziyeh-khan (performer), or naghsh khan (performer), which refer to the impersonation of the traditional characters in Ta’ziyeh. Performers do not “play roles” per se, but try to impersonate the olyasFootnote3 (protagonists) and ashghyasFootnote4 (antagonists). Andrzej Wirth believes that a performer is a role carrier who is played as a character by the act of the spectator (Wirth, Citation1979, p. 34). Both performers and audience are well aware of the space between them.Footnote5 Similarly, Parviz Mamnoun notes that, contrary to the distancing concept in Brecht’s theater, the role played by a performer in Ta’ziyeh it is not that of an ordinary human being. The characters are prophets and imams, superhuman personalities possessing superhuman virtues. There is a vast distance between the characters and the Ta’ziyeh performers portraying them, and both spectator and performer are aware of this distance (Mamnoun, Citation1979, pp. 157–158). Wirth adds, “They [the players are aware] reveal that the real aim of the Ta’ziyeh is the reinforcement of the feeling of communitas between believers on the stage and the House [tekyehFootnote6 and in the audience] … the true narrator of the story is the spectator-believer, who knows the story beforehand” (Wirth, Citation1979, p. 34). An example of the role of the spectator-believer can be found in the film Uncle Hashem by Seyed Azim Mousavi,Footnote7 which includes this anecdote about the late Hashem FayazFootnote8:

In the past, when we performed Ta’ziyeh, after the performance, people would accommodate the actors in their homes until the next day. This practice is followed in all the villages, as is seen in the present time. The reason for such accommodation was that the performer would sing about the Prophet’s family at night. Hashem Fayaz was portraying the ashghya (antagonist), but the host was not aware of that. That night, an elderly woman invited Fayaz back to her home and after dinner they asked him to sing.

He replied: “I am not a singer.”

The woman said, “Do not you perform Ta’ziyeh? Let’s start to sing.”

Fayaz answered, “I am not a performer. I recite the ashghya role. I recite ShemrFootnote9‘s song.”

Hearing his words, the woman’s husband cried, “From all those performers you invited Shemr to our home?” And they started to quarrel.

Fayaz told them not to quarrel and said, “I will leave your home” (Citation2004).

The actor of Ta’ziyeh is like a rawza-khwan,Footnote10 (a professional narrator or preacher) standing at the pulpit of a mosque—he narrates the holy history, religious events, and passion of the Prophet’s family by using words and movements from the tekyeh (platform). Anayatullah Shahidi notes that the Ta’ziyeh role carrier’s duty is to narrate the religious history of poetry and musical expression using naqqaliFootnote11 (narration) style and to display religious events in a divine manner through organized movements with the purpose of narrating the Karbala history to the audience. People see in Ta’ziyeh what they have heard from the rawza-khwan about the Karbala events (Citation2001, p. 182) (see Figures –).

At times, performers play more than one role, potentially representing all of the protagonists or all of the antagonists. Performers who have dialogue, carry a script in his hand and impersonates their role by uttering are called noskheh-khanand those without dialogue are called nash. In the style of ancient theater, all actors in public performances of Ta’ziyeh are men, some wearing special costumes to portray the women’s roles. Another kind of Ta’ziyeh, known as “feminine Ta’ziyeh” wherein all the actors were women, was performed at women’s gatherings in the past. Today this form is obsolete.

Figure 1. The positive group of Ta’ziyeh performers called olya, movafegh-khan, or “approving actors” (protagonists). They appear in green and white cloaks which signify blessing, perception, sacredness, and goodness (Mousavi, Citation2009).

Figure 2. Mirza Gholam Hussain as Abbass, an olya or approving actor, (Benjamin, Citation1987, p. 391).

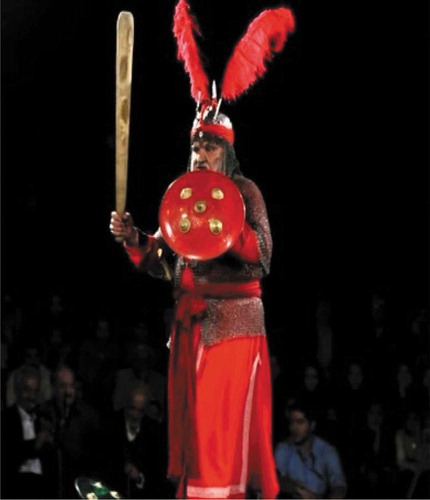

Figure 3. The second type of Ta’ziyeh are the negative group. They are called ashghiya, mokhalef-khan, or “disapproving actors” (antagonists). They appear in red cloaks signifying ferocity (Mousavi, Citation2009).

Bertolt Brecht was a famous theater practitioner and playwright in Germany in the first half of the twentieth century whose influence on modern theater has had lasting impact. The style of theater he introduced is referred to as Brechtian theater, Brechtian epic theater, or sometimes simply epic theater. As cited in Margaret Eddershaw (Citation2002), Peter Brook writes, “Brecht is the key figure of our time, and all theater work today at some point starts from or returns to his statements and achievement” (p. 80). Brecht’s concept of the Verfremden-effect (or V-effect) refers to a kind of distancing effect seemingly similar to the distancing techniques used in Ta’ziyeh. John Harrop and Sabin R. Epstein (Harrop & Epstein, Citation2000) believe that the basis of epic theater is the avoidance of the actor identifying with the characters: “Epic or Brechtian theater does not necessarily have the connotation of a heroic scale, but simply the idea of a loosely linked series of events” (pp. 294–295). In Ta’ziyeh, there is a distance between the portrayer of the shabih (role carrier or naghsh-khan) and the role itself. Andrzej Wirth believes that “The Ta’ziyeh art of acting makes the performer-believer a role carrier (rollenträger), not a character. The character exists only in the perceptual code. Thus, paradoxically, the spectator-believer ‘plays the character’ while the performer plays the role. Or better: the role carrier is played as a character by the spectator. This again underscores the active role of the perceptual code in a confessional performance” (Wirth, Citation1979, p. 34). The term “distancing effect,” if interpreted as the Brechtian V-effect, is misleading with respect to Ta’ziyeh. This study endeavors to explain why the distancing effect is different in each form, despite the frequent comparison of the two.

2. Methodology

This research uses a descriptive-analytical approach in an effort to dispel the alleged basis for comparison between Brechtian theater and Ta’ziyeh. In gathering preliminary information, accounts of traditional and modern theater based on the ideas of theoreticians such as Parviz Mamnoun and Richard Schechner were studied. As Mamnoun notes, Brecht sought a style that testified to the truth that artist was only an actor and the performance only acting. It is not an easy for actor to forget his own identity. He recommends that emphasis upon the separation of the actor from his role, both for the sake of actor himself and for that of the audience (Mamnoun, Citation1979, p. 156). He believes that, contrary to Brecht’s theater, the role played by a performer in Ta’ziyeh is not that of an ordinary human being like the performer himself (pp. 157–158). In addition, the function of the audience is different in each theatrical method. Schechner’s definition of accidental audiences (subject to selective inattention) and integral audiences (who engage in a ritual experience) are also employed in breaking down the differences between the Ta’ziyeh as a traditional Iranian play and Brechtian theater. The results contrast the dominant analysis wherein Brechtian theater and Ta’ziyeh are considered cross-cultural expressions of essentially the same form of theater.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Ritual versus propaganda

Ta’ziyeh is a prototype of Eastern performance, typically ritualistic, and Brechtian is a theater, typically non-religious. Two questions must be addressed in the comparison of these forms. First, what does the ritual mean, and, second, what does Ta’ziyeh describe? Rituals are reflections or representations of events that bear specific meanings. Marriage ceremonies, the birth of children, burial rites, and processional mourning ceremonies are all regarded as rituals. Many rites are observed in a community for their deeper meaning. Rituals have more or less conventional and prototypical structures that are seen in the theatrical structure of many especially oriental works, for instance, the Macbeth performance by Eugenio Barba in a way that it was influenced by traditional styles in Chinese theatre or Mahabharata, a Sanskrit drama directed by Peter Brook based on Western theater. Such works have a set of oriental rituals in their structure.

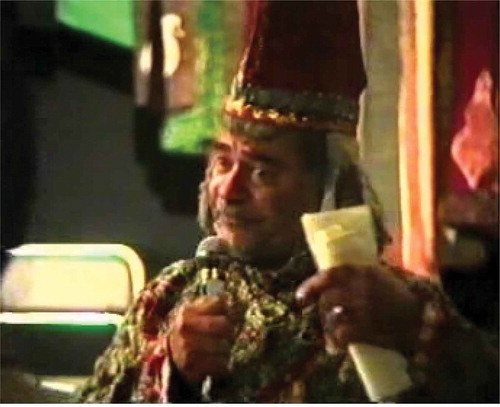

Ta’ziyeh, however, is a ritualistic-religious performance. The word Ta’ziyeh implies forbearance and fortitude in mourning. Ta’ziyeh, Ta’ziyeh-khani, Taziyat (Baktash, Citation1979, p. 96), shabih-sazi (Malekpour, Citation2004, p. 33), and Passion play (Alizadeh, Citation2012, p. 411), all of which signify the patience of and consolation for the survivors. The origin of Ta’ziyeh dates back to the pre-Islamic era in Iran. Its evolution involved elements of Zoroastrianism,Footnote12 Mithraism,Footnote13 Persian mythology, folklore, and traditional forms of Iranian entertainment. One of the most significant myths in Iranian culture, The Lamentation of Siavush (Sug-e-Siavush), is an example informing Persian mythology. “The theme of redemption through sacrifice found parallels in such pre-Islamic legends as the passion of Siavush and in the ancient Mesopotamian ritual of Adonis-Tamuz” (Chelkowski, Citation1979, p. 4). The story of Siavush and his murder has been narrated in Iran for thousands of years, and in the pre-Islamic period the murder came to be commemorated in the form of a ritual called The Lamentation of Siavush (Sug-e-Siavush). “The People of Bokhara have mournful songs on Siavush’s murder, which are well known in all provinces, are made by musicians, and are known by the storytellers as ‘Magus Cry,’ which dates back more than three thousand years” (Narshakhi, Citation1974, p. 24). The characteristics of Siavush were transferred to the religious character of Hussein in the Islamic era. As cited in Farideh Alizadeh, et al., and Rahmah Bujang, Ta’ziyeh—or the Passion play—is described as follows: the word Ta’ziyeh means lamentation for the martyred imams, particularly for Imam Hussein. Ta’ziyeh in Karbala in popular language is called Ta’ziya. It is a model that means particularly the mystery play. Lastly, Ta’ziyeh refers to the actual performance of the passion play. The stage is erected in public places such as caravanserais, mosques, and imambaras (enclosures specially erected for the event). The stage usually requires a large tabut (a replica of the tomb kept in the house, often very richly ornamented), receptacles in front to hold lights as well as Hussein’s bow, lance, spear, and banner. Besides the players, participants include the rawaz-khawan, the narrator reciting lamentation chants, khutbas, and many Hadiths (Rahmah, Citation1989, p. 99; Alizadeh & Hashim, Citation2015). Throughout the performance, the ta’ziyeh-khan (shabih, performer) emphasizes repeatedly that the characters are being imitated and are not the true characters. The ta’ziyeh-khan holds a copy of the Ta’ziyeh script in his hand, not because he has not memorized the text, but to indicate that he is representing the character but is not the character himself (see Figure ). The ta’ziyeh-khan moreover enacts his role with stereotypical and symbolic gestures, raising and lowering his arms in a manner unique to Ta’ziyeh. He recites his role by singing or using aggressive expressions to show that he is similar to that character, but not tantamount. The performers thus create a space between the shabih and the true character.

Figure 4. Hashem Fayaz (1916–2004) doing an impersonation of Sheytan (the devil). He was both moin al-Boka (Ta’ziyeh-gardan or director) and shabih-khan (player) in Ta’ziyeh Yahya & Zakarya, a Ta’ziyeh portrayed in the film Uncle Hashem (Alizadeh & Hashim, Citation2015; Mousavi, Citation2004).

This is an agreement between the shabihs (performers) and audience in which all performers and viewers are aware of the distance between the performer and what he represents. This is another reason the characters in Ta’ziyeh do not resemble those in Western theater: they are role carriers and performer-believers, not actors. Andrzej Wirth discusses a popular Ta’ziyeh scene in which a gendarme impersonates a lion. He suddenly notices his captain and, still on all fours, salutes him with his lion’s paw. This delightful story is amazing only for the Western observer who assumes uncritically that all acting is representational. Since identification and empathetic trance do not have any place in conventions of Ta’ziyeh, the gendarme’s acting does not demolish the agreement (distance between the actors and the characters) of Ta’ziyeh (1979, p. 38).

In fact, the shabih (a role carrier, performer) impersonates a role which is already known by the audience, and follows pre-scripted symbols for the role than using other dramatic interpretations. Ta’ziyeh is based on content, and does not attempt to emulate realism. All of the elements of the scene are represented in a symbolic form.

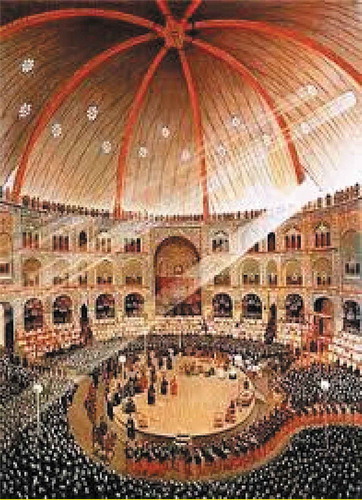

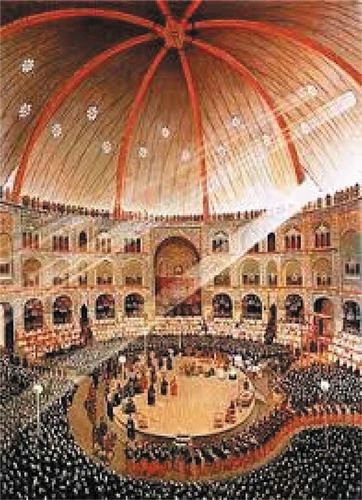

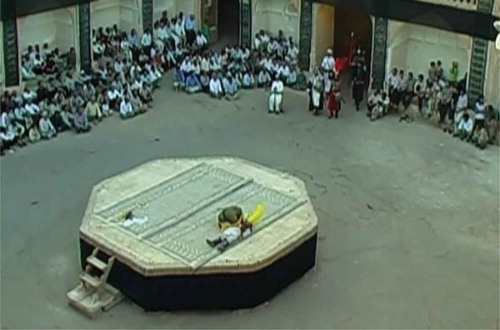

In its traditional form, Ta’ziyeh is performed in the months of Muharram and Safar, especially in the first ten days of Muharram. However, in the Qajar period (1779–1925), when the dramatic arts were developing, a comical and recreational Ta’ziyeh was also created. Tekyeh Dowlat was the most splendid theater for Ta’ziyeh during the Qajar period. Nasser din Shah Qajar built Tekyeh Dowlat with the capacity for 200 people. The stage for Ta’ziyeh was transformed into caravansaries in the contemporary era (see Figures –).

Figure 5. Tekyeh Dowlat, a place for Ta’ziyeh during Nasser din Shah Qajar (Mousavi, Citation2009; Alizadeh & Hashim, Citation2016a, p. 4).

Figure 6. Tekyeh in the caravansary in Kerman (Mousavi, Citation2009). This kind of stage is common in Iran nowadays.

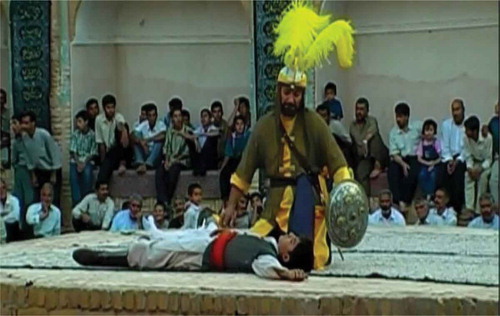

Figure 7. Hurr (the approving actor) appears in a yellow cloak and head-cover (Mousavi, Citation2009). The Arab messenger in the martyrdom of Hurr wears a shawl and when the performer is a young man, he wears a yellow head-cover only (an agreement for this distinction in Ta’ziyeh) (Shahidi, Citation2001, pp. 389–380).

At the turn of the twentieth century, a style known as theatricalism emerged in reaction to the realistic and naturalistic theater that had previously dominated Western theater. This approach theoretically undermines the realistic acting previously favored in the West, in which actors pretend that the audience is absent and attempt to create an illusion that what is portrayed is real. Conversely, Parviz Mamnoun believed that the artist is only an actor and the performance only acting. It must always be clear that the man parading on the stage is not really Othello the Venetian commander but an actor playing his role. The audience is in a theater watching actors on stage using various technologies to simulate reality (Mamnoun, Citation1979, p. 156).

Theatricalism first appeared in Russia about the time realistic theater had reached its peak with the works of Chekhov and Stanislavski, and was later inherited by Berthold Brecht, who adapted it into his own style, which came to be referred to as Brechtian or epic theater (Cody & Sprinchorn, Citation2007, p. 927; Farber, Citation2008, p. 35). Mother Courage and her Children (1914), The Good Person of Szechwan (1943), and The Caucasian Chalk Circle (1943–1945/1948) are some well-known dramas in the Brechtian style.

One of Brecht’s contributions to theatricalism was that the play should not seek the blending of the actor with the role he was playing, but rather the actor should maintain distance from his role. John Freeman states that Verfremdungseffekt is a German word meaning “to be strange to, to keep at a distance, to keep away” (Freeman, Citation2013, p. 230). In Brechtian style, two words stand out more than others: “steeped” and “distancing effect.” Victoria Jones mentions that Zeigen, which means to point out or to show, and Verfremden, which means alienation, dissociation or estrangement. In fact, Brecht used the term Verfremden, or distance, in two senses: first, as a theatrical method which is a theoretical device to Stanislavski’s methods, which attempts to control the audience’s empathetic reaction, and, second, as the end itself, that is, the “distance” which the spectator develops (Jones, Citation2004, p. 175). Thus, Brechtian titled his method the Verfremden-effect (V-effect).

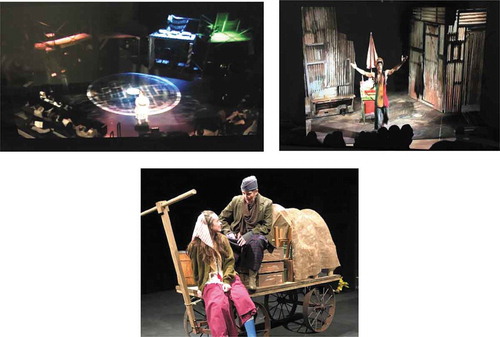

The V-effect is employed by Brechtian actors in allowing audiences to deconstruct social processes as they watch. For example, in the Life of Galileo, the character accepts his role; the audience should put the role aside and judge. This is contrary to the method of performance in Ta’ziyeh where the shabih (role carrier) emphasizes repeatedly that the characters are imitated and the actors are not the true characters. Examples from a different period include The Good Person of Szechwan and Mother Courage. In the first scene of The Good Person of Szechwan, a character narrates some notes about the story, breaking the fourth wall and talking directly to the audience about what they will see (see Figure ).

The V-effect is employed by Brechtian actors in allowing audiences to deconstruct social processes as they watch. For example, in the Life of Galileo, the main character accepts his role; after playing his role heputs the role aside and judge. This is contrary to the method of performance in Ta’ziyeh where the shabih (role carrier) emphasizes repeatedly that the characters are imitated and the actors are not the true characters. Examples from a different period include The Good Person of Szechwan and Mother Courage. In the first scene of The Good Person of Szechwan, a character narrates some notes about the story, breaking the fourth wall and talking directly to the audience about what they will see (see Figure ).

Figure 8. The top two, Figure 8a and 8b pictures demonstrate some techniques of the V-effect, generated by having the actors deliver their lines in the third person or the past tense, or reciting the stage directions aloud as they are being executed (Good Person of Szechwan in 2011) (Harris, Citation2011). The lower picture shows a scene from Mother Courage theater (Edward, Citation2014).

Brecht positioned amateur actors in his works to pursue this desired distancing. He directed them to perform both physical and discourse acts with the awareness that, since they are not steeped in realistic acting, a distancing effect would be created between the audiences’ expectations and their experience. Those who had anticipated a special experience at the theater experienced a perplexing detachment instead. In the creation of the space between gesture and essence, the audience would realize that there is a space between the actors and the acting—the drama and the production—also between the activities on the stage and social behavior. This Brechtian constitution of actor ingenuousness has been regarded as a contradiction in terms by Theodor Adorno, who suggested that even Brecht’s most successful work was “infected by the deceptions of his commitment” (Adorno, Citation1987, p. 187). According to Copeau and Brecht, as cited in James Hamilton (Citation2007), the evolution of theater was driven by perceived transformations in the social realm. No figure illustrates this shift better than Bertolt Brecht. Even in his earliest work, when Brecht writes of theater for a new audience he’s referring to what he calls a “scientific audience,” an audience that seeks to understand what is going on rather than merely empathizing with the characters without conscious and critical understanding of their situations. This new audience attitude, he maintained, demanded a new kind of performance. Brecht’s middle work employed an arsenal of devices to achieve the kind of emotional distance that Brecht thought suitable for this new audience. Some of the techniques seem quite simple in retrospect, but were extraordinary at the time: for example, having actors deliver their lines in the third person or transposing them into the past tense, or reciting the stage directions aloud as they were being executed (p. 6). Ta’ziyeh would seem to be the very theatrical method and style that Brecht was after. However, the objective of performing Ta’ziyeh has never been anything but the invigoration of people’s faith. What is important in performing Ta’ziyeh is that the epic poems reflect people of the story of Imam Hussein’s martyrdom and the life of the Prophet and his family. For this reason, the Ta’ziyeh writers refrained from signing their names at the end of the script. They wished to receive their reward from God as they wrote and sang for the divine blessing. By the same token, the spectators in Ta’ziyeh ceremonies help in any way they can so that they will be blessed too. These esoteric signs indicate unity and an association between the Ta’ziyeh performers and spectators. From a religious standpoint, by participating in Ta’ziyeh, the spectators reach a level of catharsis and purification. They believe that by watching Ta’ziyeh and lamenting, their sorrows will diminish a little.

Brecht’s methodology expresses a modified view of reality. This attitude is completely foreign to Ta’ziyeh, which is interested in the emotional state of the present, that is, in strengthening the religious feelings of the spectators and presenters. In the Ta’ziyeh of Imam Hussein’s martyrdom, people do not consider Hussein’s martyrdom as that of an ordinary man. By engaging the story, the audience passes beyond borders of time and space and considers the performance as a kind of resurrection or catharsis for believers and as another death of the martyrs. Thus, the comparison between distancing in Ta’ziyeh and the V-effect in Brechtian theater is superficial one.

To gain a better perception of the V-effect (distancing effect) between the actors and audiences as well as between the actors and their respective roles, the principles of Brechtian theater should be illuminated. According to research by Farhad Nazerzadeh-Kermani an Iranian researcher, theater instructor and playwright, Western theater is divided into two forms of dramatic theater, namely, Brechtian theater and non-conventional theater (Nazerzadeh-Kermani, Citation2005, pp. 195–196). These are known by other names, but all forms of theater, according to Nazerzadeh-Kermani, are a projection of the methods and styles connected with one of these, though each may represent only a part of the aforementioned two theatrical forms. John Harrop and Sabin R. Epstein believe that in Brechtian theater, linear plots and climax are meaningless, while emotional focus is constrained and the Aristotelian structure is inefficient (Harrop & Epstein, Citation2000, pp. 294–297). Jamshid Malekpour stated that, in order to understand Ta’ziyeh as a form of performing art, we need to understand its elements: plot, characters, diction, thought, and spectacle (Malekpour, Citation2004, p. 20). Neither theatrical form, therefore, follows mythological principles, and each possesses its own set of performance conventions.

Iranian theoretician Shirin Taavoni believes that Brecht used the method of estrangementFootnote14 to remove the axioms and everyday problems, all of which have lost their strange aspects and are void of their original meaning. The empathy associated with Aristotelian theater creates an ordinary incident from a special event. Alienation, on the other hand, changes an ordinary incident to a special one. Even the most trivial and repeated daily events may be freed from banality by rendering them special. Taavoni stated that alienation allows the given subject to be recognized and simultaneously made extraordinary (Taavoni, Citation1976, pp. 49–50). In the Brechtian theater, the actors’ styles, assisted by the distancing effect and the breaking of theatrical illusion, provide the spectator with an opportunity to think rather than connect emotionally. The spectator is well aware of and even focused on the stage, evaluating the play with an active mind as it unfolds before him. As John Harrop and Sabin R. Epstein state, the audience must be reminded that they are in a theater, and that the play is not a seamless whole, but is constructed from many parts, and those parts must be kept independently visible; therefore, the audience may reflect upon the way the events are represented. He adds, the intention is to exhibit not only the action, but also the manner in which they are subjected to the processes of theater (Harrop & Epstein, Citation2000, pp. 294–297).

Ta’ziyeh is based on content and neither looks for realism nor shows it. It seeks to depict the attributes of the prophets and imams. Ta’ziyeh does not tell the story of ordinary humans, but of extraordinary events and characters, which is the opposite of Brechtian theater. Ta’ziyeh performers are imitating the prophets’ and imams’ characters. For example, on the day of the Ashura (the tragedy of Karbala),Footnote15 angels appear to help Imam Hussein; in another example, Imam Hussein flies away to save some other individuals. Clearly, the characters are not ordinary humans and the stories do not portray everyday events (see Figures and 1).

Figure 9. Ashura (The Tragedy of Karbala) (Seyf, Citation1990, p. 109).

More than that, Ta’ziyeh does not reflect the events of Karbala in a realistic manner. All of the elements of the scene are represented in symbolic form. It is from this angle that Ta’ziyeh seems to be closely related to Brechtian theater. For instance, when the olya (protagonist) plays the role of a mythical character or a pious soul, or when an ashghya (antagonist) dramatizes their role on stage, they do not believe they can, using ordinary language and gestures, sufficiently capture divine and mythical attributes. Such portrayals require extraordinary actions and voices. Such a performance, carried out in a narrative form, does not deny the fact that it is a narrative, for in Ta’ziyeh, no actor, not even the most skillful, can lift the distance which is an inevitable part of the audience’s perception and performers’ representation of the sublimity of the heroes. Ta’ziyeh provides an opportunity for spectators to renew their accession to their religious order through ritual participation. In actuality, the spectator is an integral part of this confessional performance of Ta’ziyeh. As cited by Enrico Fulchignoni, a Ta’ziyeh scholar, the objective of Ta’ziyeh is not only to strengthen the moral and religious resolve of the audience, but also to provoke an internal purifying reaction (a cathartic experience for the spectators), which may find its outward expression in laughing or crying, indignation or excitement (Fulchignoni, Citation1979, p. 135). The tragedy of Karbala is so important to the Ta’ziyeh performer, it is not within the means of a performance to show it realistically. It is possible to reflect this tragedy, but not to reproduce it.

Martyrdom is associated with victory in Iranian culture. Thus, in Ta’ziyeh, the hero’s murder is the very thing that makes him victorious, bestowing upon him an honorable attribute. A dialogue in tragedy is known as sokhanvari (oration) in Ta’ziyeh and the difference in how dialogue is delivered rests mostly in tone. The performers of olyas (protagonists, e.g., prophets) sing their poems in a genuine Iranian singing style and music assists them with the pitch and melody. The performers who play the ashghyas (antagonists) utter their speeches in a declamatory and aggressive tone. Their questions and answers are similar to a dialogue, and each performer’s speech in Ta’ziyeh is different from pure monologue. Jalal Satari believes that the actor is not actually acting in Ta’ziyeh, but performing an act of worship (Satari, Citation2009, p. 209). This is because the death of Hussein is regarded as a sacred redemptive occurrence, and the ceremonies performed during the first ten days of Muharram are believed to cleanse a person of their sins. Based on this belief, anyone who participates in the performance, including both performers and audience, will be entitled to divine intercession by Hussein on the Day of Judgment.

3.2. Integral and accidental audience

To better understand the types of audiences in theater, we should refer to Richard Schechner, according to whom there are two main types of audience: accidental (selective inattention) and integral (ritual experience). The “accidental audience” comes to see the show while the “integral audience” is necessary to accomplish the work of the show. The accidental audience attends voluntarily; the integral audience out of a need for ritual. In fact, the presence of an integral audience is the surest sign that the performance is a ritual (Citation2005a, p. 186). In essence, the difference between integral and accidental audiences constitutes the primary distinction between Ta’ziyeh and Brechtian theater. In ritualistic performance, what position the audiences have? Under which circumstance, does the audience participate in Ta’ziyeh performance involuntarily? By answering these questions, the position of the audience and the participants in Ta’ziyeh would be made clear.

After World War II, with the advent of social drama, Western theater performances were divided into two groups depending on how they viewed the audience: those interested in audience participation and those interested in their passivity. As cited by Schechner, aesthetic drama transforms the audience, which is separated both actually and conceptually from the performers. This separateness of the audience is the hallmark of aesthetic drama. In social drama, everyone present is a participant, though some are more decisively involved than others. In aesthetic drama, everyone in the theater is a participant in the performance while only those playing roles in the drama are participants in the drama nested within the performance (Citation2005b, p. 146). The group interested in audience passivity originally rejected any audience involvement. They believed that connection in theater is uni-directional. There is good reason, according to Elam Keir, to believe that “if theatrical discourse were genuinely articulated into cohesive and well-defined units like language itself, then such units would be intuitively recognizable to both performers and audience as the conventional vehicles of communication. The difficulties involved in defining appropriate categories suggest that is not the case” (Keir, Citation2002, p. 48). On the other hand, there are also groups that are inspired by Eastern theater and interested in ancient rituals. They believe that it is necessary for the audience to participate in the performance during the course of a play, and they encourage the audience to do so. This relationship begins long before the performance starts and continues long after it ends. Ta’ziyeh shapes the communicative space before the performance begins. This space is formed by signs. The local people bring some symbolic materials to form the scene and prepare for the performance of Ta’ziyeh.

The performance of Muharram ceremonies is all about the people’s collective efforts that create strong competition among social groups. Ta’ziyeh narrators are greatly indebted to the collaborations of neighborhood groups such as the “dash” or “dashhaye of Tehran,” which refers to a group of people who form community associations. Most of these groups of take on the responsibility of preparing the Takyehs (temporary religious centers) for the performance of Ta’ziyeh (Calmard, Citation1979, p. 127). The audience, after erecting the space for Ta’ziyeh, also participates in the performance. Their participation mostly takes the form of joining in the elegizing with the shabih-khanan (players, reciters), singing lamentations that represent the mourning and crying of the survivors of Hussein after the martyrdom of one of his comrades. This is when the audience plays the role of the troops. The crying and lamentation stem from the tradition of Tashaboh (re-enactment, shabih-khani or Ta’ziyeh) and the audience, by sympathizing with the olyas’ (protagonists’), attempt to dispose the olyas in their favor.

The passion of Ta’ziyeh creates an emotional atmosphere in which people unite in a sacred and mysterious space, which is the place of the Holy Spirit and ancestors. Some of Soroosh Isfahani’s lines clearly manifest this sensation:

Almost all scholars who have written on Ta’ziyeh have paid special attention to the relationship between the audience and the performers. This relationship is particularly resistant to Western theatrical traditions because the audience is so deeply invested. They are present in the Karbala desert and symbolically represent the troops besieging Hussein and his comrades, yet in their own real world they lament this tragedy and play this part in completing the performance. William O. Beeman believed that people’s real life experiences fuel their explicit utterances of grief and only the showing of the events on the Tekyeh (platform) effectively brings out their grief. In fact, the audience is incited to weep over their own problems and sins and remember how much greater the sufferings of Imam Hussein and his comrades were (Beeman, Citation1979, p. 26). Parviz Mamnoun further states that if a day comes when Ta’ziyeh performance employs realistic acting performed on a theater stage instead of the traditional venues, and uses modern costumes and music composed specifically for the show, that day would surely mark the demise of Ta’ziyeh (Mamnoun, Citation1979, p. 159). Although the “distancing effect” in Ta’ziyeh and Brecht’s works seems to yield similar results, they are not in the same category. Brecht uses distance in an attempt to prevent the audience from being absorbed or captured by the stage, to keep the audience’s judgment awake. He rejects the notion that the audience can only be reached through an appeal to emotion. On the contrary, he does not want the audience to relate to the characters and become so emotionally involved with them that they fail to think about their own lives. This appeal to the audience’s reasoning mind is where Brecht believes social change will come.

In Ta’ziyeh, the actor and the role cannot fundamentally become one because what the actor performs is a form of worship. The actor regards himself as insignificant compared to the olya and antithetical to the imams’ enemies. How can he then unite with them? He does not even imagine becoming one with an imam or with any of his enemies. In the first place, he is committing blasphemy and in the second, he is welcoming hell into his own person. What constitutes a more convention in Brecht’s theater is the main natural principle in Ta’ziyeh.

4. Conclusion

The study and analysis of various theatrical forms and performances in Iran, including Ta’ziyeh, reveals the interaction between traditional-religious and contemporary performances, especially Brechtian theater. The influence of this effect is evident in written works, critiques, and oral works. This has resulted in these performance styles being referred to as traditional-religious theater. Ta’ziyeh is a ritual-religious performance, wherein the performers and singers are not steeped in the roles they play. They narrate the characters in service of the religious ritual and belief, in contrast to Brechtian theater where the purpose of the distancing effect is to disseminate social ideologies. Ta’ziyeh, conversely, is all about the ideology of faith. The performer of olya (protagonist) is not interested in taking the role of the ashghya (antagonist), as the audience deeply despises such characters. Instead, they admire the sacred characters from a distance. In other words, the actor in Brecht style would play his role according to the theatrical rules and principles, but in Ta’ziyeh what is important is belief. One impersonating the ashghya (antagonist, disapproving actor) is not interested in wearing disapproving actor’s clothing and the one dramatizing Imam Hussein’s role does not consider himself worthy of the place of imam, but he only narrates the olya or ashghya’s words. It is important to remember that if Brecht is to be connected to the Iranian traditional form of theater, his theatrical style must inevitably be challenged. However, that challenge could lead to confusion regarding the most basic principles about Brechtian theater. Brecht does not pursue a realistic style of theater, but it does, in principle, imitate social life. In this respect, Brechtian theatre is similar to Ta’ziyeh methodology, but different in content. Brechtian theater contains social content on a more superficial level. Characters range from abstract political types to complex individuals whose conflicting social roles produce profound inner conflict.

Brecht believed that theater should not manipulate the audience’s feelings, but should appeal to their reason and mind, encouraging them to have a more critical attitude toward what is happening on stage. He wanted to reach ultimate objectivity from the audience’s side, rather than compelling them to identify with the characters empathetically. This way the audience will learn the truth about their society and world.

The Brechtian/Western theater audience usually has no information about the story and the performance in advance. They watch the story unfold and see its attractions and then understand the inner meaning via decoding. These esoteric meanings, however, are the point of interaction between the audience and performance in Ta’ziyeh. The audience has already dealt with the content before the performance ever begins. The story has been told again and again. In reminding the audience of the story, Ta’ziyeh refers to concepts beyond the story, and in the process of performance, puts them before the audience’s eyes. In Western theater, this is not recommended and is in fact disfavored. In Brechtian theater, for the purpose of separation of the writer and the audience, the writer can impose his ideas on the audience. Writers and audiences are distinguished as individuals. For this reason, they form dissimilar individual ideologies. Dialogue is created in light of such individual ideas, but in Ta’ziyeh, religious ritual is the principal characteristic of the performance and everything is simulated, including events that are accompanied by divine intervention.

The audiences are, therefore, in both cases informed of the style of performance, but the main difference between the audience of Brechtian theater and the audience/participants in Ta’ziyeh rests in the political-social focus of Brechtian theater versus the centrality of faith in Ta’ziyeh. In Brecht’s theater, the performing group tries to replace common beliefs with new ideologies, but in Ta’ziyeh, performers illustrate and reinforce existing ideologies. The inspiration of the concepts is the main axis of the performance in both forms; however, they are different.

Iranian traditional presentational acting is narration-based. It is customary for the traditional performer to play another character’s role or give news unrelated to the character. Through such tactics, the performers easily differentiate between the character and the role and understand it through allegory and dramatic exaggeration. One of Brecht’s contributions to theatricalism was that the play should not seek the blending of the actor with the role he was playing, but rather the actor should maintain distance from his role. Despite the presence of both facets in Western theater, however, ritual and the distancing effect are not the objectives of traditional performance, rather these are the intrinsic and natural logic of a performance that inherently must not be based on realism. It is natural that the performers supervise the role, and emphasize the obscenity of the action or virtue of the behavior, to incite pro-and-con judgments by the audience. It is also natural that the performers ask for water to drink during the performance break, refresh their makeup, or recite their role from a copy of Ta’ziyeh. Since Ta’ziyeh is performed every year, it has left an impression on contemporary Iranian theater. Playwrights have paid more attention to the events of Hussein’s life and the lives of the Prophets. Majles-nameh (Rahmanian, Citation2000) and Story of Love (Ashaghe) (Rahmanian, Citation2004) are examples of this influence. In theaters of this style, a play is performed simplistically so as to be understood by all and, just as in Ta’ziyeh, good and bad characters are played out.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Farideh Alizadeh

Farideh Alizadeh and Mohd Nasir Hashim have collaborated on different projects since 2014. Their publications in the performing arts and multidisciplinary research, either individually or collaboratively, include “Ta’ziyeh-influenced Theatre” (2015), “Eclecticism in Drama” (2016), “When the attraction of Ta’ziyeh is diminished, the community should inevitably find a suitable replacement for it!” (2016), “Role of Cultural Coffee-house in the Sustainable Development of Traditional Performance in Iran” (2017), “Xenophobia in Shakespeare’s the Merchant of Venice” (2018), and “Kaboudan and Esfandiar Under Eclecticism: An Analytical Study” (2019).

Notes

1. Tekyeh, Tekiyeh, Takiyeh, or Takyeh is the platform or stage used for the performance of Ta’ziyeh.

2. For more information, refer to Fernea (Citation2010, p. 284).

3. Olya means movafegh-khan, translated “approving actor” or “protagonist.” More precisely, “approving actor” is the term for an actor who impersonates a martyr, such as Moslem or Kasim. For more information, refer to F. Alizadeh and Hashim (Citation2015).

4. Ashghya refers to mokhalef-khan, that is “disapproving actor” or “antagonist,” which in Ta’ziyeh is an actor who plays the role of an enemy of the Prophet’s family. For more information, refer to Alizadeh and Hashim (Citation2015).

5. For this reason, the researcher prefers using the terms “player”/“performer” (shabih or naghsh khan) instead of “actor”; “perform” instead of “play”; “olya” for “protagonist” and “ashghya” for “antagonist.” For more information, refer to F. Alizadeh and Hashim (Citation2015).

6. Tekyeh, Takiyeh, or Takyeh is the platform or stage used for the performance of Ta’ziyeh.

7. Seyed Azim Mousavi is an Iranian director and traditional theatre expert in Iran. The ritual dramatic art of Taazyeh, by Seyed Azim Mousavi, produced by Cultural Heritage for UNESCO, Handicrafts & Tourism Organization, supported by Dramatic Arts, August 2009. Retrieved 12 February 2012, from, http://www.unesco.org/archives/multimedia/index.php?pg = 34&kw = Seyed%20Azim%20Mousavi.

8. This is a part of my interview with Hashem Fayaz who was named as Ali Baba of Iran by Peter Brook, and who performed the Ta’ziyeh of Hurr Ibn Yazid and Imam Reza in Avignon, France, in 1992. In the Ta’ziyeh, he brought horses onto the stage during a live performance (Fayaz, Citation1998).

9. “Shemr” considers as antagonist and antagonists do not sing in Ta’ziyeh. Generally, not only it is considered the worst performer in Ta’ziyeh, but also is very hated character in Persian culture.

10. Razaw-khani means narrative recitation, a professional narrator from the tragedy of Karbala, or a preacher. Rawza is also called Rauza, Rouza, or Roza (Urdu: روضة). It is a Perso-Arabic term used in the Middle East and India and means “shrine” or “tomb.” It is also known as mazār, maqbara, or dargah. The word rauza is derived in Urdu through Persian from the Arabic rauda, meaning “garden,” but extended to tombs surrounded by gardens as at Agra and Aurangabad. Abdul Hamid Lahauri, the author of the Badshahnama, the official history of Shah Jahan’s reign, calls the Taj Mahal rauza-i munawwara, meaning the “illumined” or “illustrious tomb in a garden” (retrieved 17 August 2014, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rauza; Alizadeh, Citation2012, p. 2680).

11. Naqqali means to narrate a story in the form of a poem, including suitable movements, gestures, and expressions. The purpose of the narration is to inspire feeling and affection in the audience using an attractive story, suitable expressions, and compelling movements and gestures so that the viewer may feel the player at any time to be the story’s hero. The narrator should be able to perform all of the story’s characters (Alizadeh et al., Citation2019, p. 12).

12. Zoroastrianism is an ancient religion founded by Zarathustra in Persia (modern-day Iran). It may have been the world’s first monotheistic faith. It was once the religion of the Persian Empire, but has since been reduced in numbers to fewer than 200,000. With the exception of religious conservatives, most religious historians believe the Jewish, Christian, and Muslim beliefs concerning God and Satan, the soul, heaven and hell, the virgin birth of a savoir, the slaughter of the innocents, resurrection, the final judgment, etc. were derived from Zoroastrianism (retrieved 15 September 2014, from http://www.religioustolerance.org/zoroastr.htm).

13. The worship of Mithra, the Iranian god of the sun, justice, contract, and war in pre-Zoroastrian Iran. Known as Mithras in the Roman Empire during the second and third centuries AD, this deity was honored as the patron of loyalty to the emperor. After the acceptance of Christianity by the emperor Constantine in the early fourth century, Mithraism rapidly declined (retrieved 15 September 2014, from http://global.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/386080/Mithraism).

14. Estrangement is a term that is used in Iran alongside with v effect and distancing effect.

15. Ashura is the day of commemoration of the martyrdom of Hussein, Muhammad’s grandson. It is a “holy day in Islam, the tenth day of the month of Muharram. It commemorates the day Noah left the ark and the day Moses was saved by God from the Egyptians, and it is a voluntary day of fasting for all Muslims. For Shiites it is a solemn day of mourning, commemorating the martyrdom of Hussein, grandson of Muhammad, who was killed in the battle of Karbala (680 AD). Shiites observe Ashura with memorial services at mosques, public processions of mourning (including self-flagellation in some instances), and plays that reenact Hussein’s martyrdom (retrieved 27 October 2014, from http://encyclopedia2.thefreedictionary.com/Ashura).

References

- Adorno, T. (1987). Commitment. In Aesthetics and Politics. London: New Left Books.

- Alizadeh, F. (2012). Boria in Malaysia. World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology International Journal of Data Engineering, 6(10), 411–19. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.3510295.v1

- Alizadeh, F., & Hashim, M. N. (2015). Ta’ziyeh-Influenced Theater. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

- Alizadeh, F., & Hashim, M. N. (2016a). When the attraction of Ta’ziyeh is diminished, the community should inevitably find a suitable replacement for it. Cogent Arts & Humanities, 3(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311983.2016.1190482

- Alizadeh, F., & Hashim, M. N. (2016b). Eclecticism in Drama. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

- Alizadeh, F., Hashim, M. N., & Makhubu, N. (2019). “Kaboudan and Esfandiar” under eclecticism: An analytical study. Cogent Arts & Humanities, 6(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311983.2019.1644698

- Baktash, M. (1979). Ta’ziyeh and its philosophy. In P. J. Chelkowski (Ed.), Ta’ziyeh Ritual and Drama in Iran. New York University Press.

- Beeman, W. O. (1979). Cultural dimensions of performance conventions in Iranian Ta’ziyeh. In P. J. Chelkowski (Ed.), Ta’ziyeh ritual and drama in Iran. New York University Press.

- Benjamin, S. G. W. (1987). Persia and the Persians. John Murray. Digitalized by the Internet Archive in 2008 with funding Microsoft Corporation. P. 373.

- Calmard, J. (1979). Le Patronage des Ta’ziyeh: Elements pour une Etude global. In P. J. Chelkowski (Ed.), Ta’ziyeh ritual and drama in Iran. New York University Press.

- Chelkowski, P. J. (1979). Ta'ziyeh: Indigenous Avant-Garde Theatre of Iran. In P. J. Chelkowski (Ed.), Taziyeh Ritual and Drama in Iran. New York: New York University Press

- Cody, G. H., & Sprinchorn, E. (Editors.). (2007). The Columbia encyclopedia of modern drama (pp. 927). Columbia University Press.

- Eddershaw, M. (2002). Performing Brecht: Forty years of British performance. Routledge.

- Edward, S. B. (2014). Mother courage and her children. Produced by Randolph College WildCat Theater, Virginia, in November 2014. www.randolphcollege.edu

- Farber, V. (2008). Founders of Russian actor training. In Stanislavski in practice actor training in Post-Soviet Russia. Peter Lang.

- Fayaz, H. (1998). Moei al-Boka, Ta’ziyeh gardan. Interviewer: F. Alizadeh.

- Fernea, E. (2010). Remembering Ta’ziyeh in Iraq. In P. J. Chelkowski (Ed.), Eternal performance: Ta’ziyeh and other shiite rituals. Leelabati Printers.

- Freeman, J. (2013). No boundaries here: Brecht, Lauwers, and European theatre after postmodernism. New Theater Quarterly, 29(03), 230. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/new-theatre-quarterly/article/no-boundaries-here-brecht-lauwers-and-european-theatre-after-postmodernism/AE7F9C894DF3498602ABA82165581D75http://cel.webofknowledge.com/InboundService.do?customersID=atyponcel&smartRedirect=yes&mode=FullRecord&IsProductCode=Yes&product=CEL&Init=Yes&Func=Frame&action=retrieve&SrcApp=literatum&SrcAuth=atyponcel&SID=E5BwF5AEtOJgY1mCzhw&UT=WOS%3A000323012700002https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/new-theatre-quarterly/article/no-boundaries-here-brecht-lauwers-and-european-theatre-after-postmodernism/AE7F9C894DF3498602ABA82165581D75

- Fulchignoni, E. (1979). Quelques considerations comparative entre les rituels du ta’ziyeh iranien et les “Spectacles de la Passion” du Moyen Age Chretien en Occident. In P. J. Chelkowski (Ed.), Ta’ziyeh ritual and drama in Iran. New York University Press.

- Hamilton, R. J. (2007). The art of theater. Blackwell Publishing.

- Harris, D. (2011). The good person of Szechwan. Performed by The Falcon’s Eye Theater at the Lake College in Folsom, California, in November 2011. https://dearkitty1.wordpress.com/2013/12/19/bertolt-brechts-good-person-of-szechwan-on-stage/

- Harrop, J., & Epstein, S. R. (2000). Beckett. In Acting with style. Allyn and Bacon.

- Isfahani, S. (2008). Book of Poetry. Persian Poetry.

- Jones, V. (2004). Brecht’s reception of stanislavski 1922 to 1953. King’s College, University of London.

- Keir, E. (2002). The semiology of theater and drama. Routledge.

- Malekpour, J. (1983). Drama in Iran, Volume 1 (3). Tehran: Toos.

- Malekpour, J. (2004). The Origin and Development of the Ta’ziyeh in The Islamic Drama. Frank Cass.

- Mamnoun, P. (1968). Introduction and review the taxation drama by Jenab Moeinol Baka. Theater Quarterly, 4(2), 14. 20.

- Mamnoun, P. (1979). Ta’ziyeh from the viewpoint of the Western theatre. In P. J. Chelkowski (Ed.), Ta’ziyeh ritual and drama in Iran. New York University Press.

- Mousavi, S. A. (2004). Cousin Hashem (film). Produced by Dramatic Art Center.

- Mousavi, S. A. (2009). The ritual dramatic art of Ta’ziyeh. Cultural Heritage for UNESCO Arts (Producer). Retrieved December 23, 2013, from http://www.unesco.org/archives/multimedia/index.php?pg=34&kw=Seyed%20Azim%20Mousavi

- Narshakhi, A. M. B. J. (1974). The history of Bokhara. Iranian Culture Foundation.

- Nazerzadeh-Kermani, F. (2005). An introduction to drama. Samt.

- Rahmah, B. (1989). The Boria of Pinang: From ritual to popular performance. Journal Pengajia Malayu, 1(1), 99.

- Rahmanian, M. (2000). Majlesnameh. Cheshmeh.

- Rahmanian, M. (2004). Ashaghe. Cheshmeh.

- Satari, J. (2009). The background of Ta’ziyeh and theater in Iran. Amir Kabir.

- Schechner, R. (2005a). Selective inattention. In Performance theory. Taylor & Francis e-Library.

- Schechner, R. (2005b). From ritual to theatre and back: The efficacy-entertainment braid. In Performance theory. Taylor & Francis e-Library.

- Seyf, H. (1990). Coffee-House Painting. Tehran: Ministry of Culture and Higher Education, Iranian Cultural Heritage Organization.

- Shahidi, E. (2001). In A. Bolokbashi (Ed.), Ta’ziyeh and Ta’ziyeh-Khani in Tehran: A Research on the Shia Indigenous Drama of Ta’ziyeh from the Beginning to the End of Qajar Era. Tehran: Cultural Research Bureau in Cooperation with Iranians National Commission for UNESCO

- Taavoni, S. (1976). Brecht Technique. Amir Kabir Press.

- Wirth, A. (1979). Semiological aspects of the Ta’ziyeh. In P. J. Chelkowski (Ed.), Ta’ziyeh ritual and drama in Iran. New York University Press.