Abstract

The link between past and present generations can only be maintained with effective preservation of cultural (Architectural) heritage. Architectural Heritage Preservation (AHP) is under threat in Ghana with an apparent dwindling awareness, unrelenting teardowns and destruction of historic buildings and places for other infrastructure development and spontaneous housing settlements. This paper seeks to review literature to establish the need to conduct further research on the state of architectural heritage preservation in Ghana. This research is underpinned with interpretivism and theoretically assesses the state of AHP in Ghana through review of literature. Literature reviewed revealed low publicity concerning heritage preservation, inadequate human resource responsible for heritage preservation and need to improve Ghana’s Architectural Heritage management. The study therefore recommends further research in heritage studies to ensure effective protection and preservation of Ghana’s rich architectural heritage.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Architectural heritage is the physical evidence of how early generations lived and built cities. It is historic and important as it identifies people and give meaning to place. United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has member states including Ghana which are supposed to protect and preserve monuments, group of buildings and sites of historic significance. Ghana has two item on the world heritage list namely; Asante traditional buildings from 18th century and Forts and Castles along the coast from 14th century. There is the need to study how this heritage is being managed and preserved. Before this study, the researchers sought to embark on a review of what has been done about heritage preservation. It was realized that not much has been achieved in landscape, public awareness, development of Cultural Centers and Museums, human resource and heritage management and therefore needs further research.

1. Introduction

Architectural Heritage Preservation (AHP) helps current generations to understand and relive past memories and ways of lives and further gives identity to a place for direction into the future (Graham et al., Citation2000; McMorran, Citation2008). Ghana is endowed with rich diverse culture with meanings and values well upheld by various ethnic groups. This diverse culture which is expressed in both tangible heritage—natural or built landscape, building, relics, monuments, personal inheritance and intangible heritage—festival, value, way of life, ceremony (Timothy & Boyd, Citation2003) must be well preserved to maintain the link between past and present generations. The value and meaning of place is a function of its past and the transformations to its future, however, Ghanaian cities and towns are on the verge of losing its value beyond debris without preservation of Architectural heritage. It is however, interesting to note that two items of Ghana’s rich architectural heritage (Forts and Castles along the coast and Asante Traditional Buildings) has been captured on the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO) World Heritage List (WHL) four decades ago (Fredholm, Citation2016; UNESCO, Citation2018). The number captured on the WHL is relatively small considering the rich architectural heritage of Ghana. Preservation/conservation of this rich heritage is imminent as it seems to be under threat with declining awareness resulting in incessant tear down of historic buildings (Oppong & Brown, Citation2014). Debris from relentless destruction of historic sites and other cultural assets have been as a result of extensive public and private development of cities and towns in Ghana (Ghana News Agency—GNA, Citation2012). Demolishing of historic sites for infrastructure development, spontaneous housing settlements and gentrification has rendered the redevelopment of most Ghanaian cities with little or no attention to preservation of historic buildings and sites (Adarkwa & Oppong, Citation2005, Citation2007; Jenkins et al., Citation2007; Njoh, Citation2006; Olanrewaju, Citation2001; Tipple et al., Citation1998; Twumasi-Ampofo & Oppong, Citation2016). Redevelopment of cities could incorporate retrofitting and adaptation of buildings (Adom & Bekoe, Citation2012) but not much has been achieved in this area, disturbing the memory of place in Ghana with its new town planning scheme implementation deficiency; ignoring basic land use aspects which must be strictly preserved for sustainable development. This paper seeks to review literature to establish the need to conduct further research on the state of architectural heritage preservation in Ghana.

2. Methodology

This paper theoretically assesses the state of Architectural Heritage Preservation (AHP) in Ghana through review of literature. To be able to establish the state of AHP in Ghana, this study adopts qualitative research approach to discuss architectural heritage preservation in Ghana, theorizing heritage preservation and overview of world heritage preservation including UNESCO’s criteria for listing heritage sites. As a research technique, literature review has been used in architectural heritage studies (Fredholm, Citation2015; De la Torre, Citation2013; Lawless & Silva, Citation2017; Rahman et al., Citation2018). This study is aimed at producing descriptive analysis with emphasis on interpretive understanding (Henning, Citation2004) of the state of AHP in Ghana. On that note, the study is a social phenomenon (Christiansen et al., Citation2010; Walliman, Citation2011) which lends itself to a historic traditional narrative (Bavir & Rhodes, Citation2012) and therefore underpinned by interpretivism as a philosophy. The term “preservation” is used interchangeably with the term “conservation” within this studies (Gholitabar et al., Citation2018; Lah, Citation2001).

This study utilizes journals, thesis and books on heritage studies as major sources of data from credible electronic database such as Academia, Google Scholar, KNUST D-Space, Research gate and Science direct. Descriptors were used to obtain wider coverage results (Anzagira et al., Citation2019) in heritage studies as Darko and Chan (Citation2016) argue as to how impracticable it is to consider all descriptors within a single study. The descriptors considered in this study include “cultural heritage”, architectural heritage’, “heritage preservation”, “heritage conservation”, “architectural heritage preservation in Ghana”, “UNESCO”, “world heritage criteria”, “world heritage list”. Most of the documents reviewed are published in “Journal of Science and Technology”, “Conservation and Management of Archeological sites”, “Tourism Geographies”, Journal of Travel Research”, “African Journal of Applied Research”, “Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development”, Journal of Cultural Heritage” and other publications from “Elsevier”, “Emerald”, “Routledge”, “Sage”, “Taylor and Francis” among others. Thesis on Heritage studies in Ghana was obtained from KNUST D-Space as indicated in Table .

Table 1. Research materials and methods

From Table , related articles searched using the above descriptors for the study is from 1990 to 2019 and this was conducted from January 2019 to August 2019 to ascertain the current state of AHP in Ghana. An initial quick read through abstracts of 285 documents resulted in the review of 37 found to be relevant to AHP while the rest has to do with tourism, artifacts, performing arts and linguistics. Similar to Darko and Chan (Citation2016) argument, it is almost impossible to review all articles under heritage preservation for this study.

3. Architectural heritage preservation in Ghana

Ghana is the first Sub-Saharan Africa country to form a National Committee of International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) in 1968, and ratified the 1972 United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO) Convention with respect to Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage in 1975. Ghana’s Heritage on the world stage is significantly highlighted by historic battles of conquest along its coastal areas with the resulting list of Forts and Castles and other monuments which represent the early transactions with the Europeans. The Ghana Museums and Monuments Board (GMMB) which is responsible for the preservation and projection of the nation’s cultural heritage (GMMB, Citation2015), has listed properties of Outstanding Universal Value (OUV) on the UNESCO World Heritage List (WHL). These include the “Forts and Castles” and the “Asante Traditional Buildings” listed on the WHL in 1979 and 1980 respectively (Fredholm, Citation2016). The Forts and Castles built between 1482 and 1786 span a distance of about 500 km along the coast from Keta in the Volta Region to Beyin in the Western Region of Ghana (Anquandah, Citation1999; Bruku, Citation2015; Van Dantzig, Citation1980). These were built and occupied at different periods by Europeans (Portugal, Spain, Denmark, Sweden, Holland, Germany and Britain) as trade link for gold and slaves to the Americas until its abolishment in the 19th century. Found around Kumasi are groups of buildings representing the Asante Civilization which reached its peak in the 18th century. The Asante Traditional Buildings on the WHL include 10 shrines in Abirim, Asawasi, Asenemaso,Adako Jachie, Bodwease, Ejisu Besease, Kentinkrono and Saaman (GMMB, Citation2015). These items on the UNESCO WHL in Ghana are not well managed and there is the need for immediate attention to save these treasures from destruction (Nyarko, Citation2018). Sustainable heritage conservation can be achieved through proper planning and Ghana’s heritage planning has been spearheaded by Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and the Ghana Heritage Conservation Trust (GHCT) particularly in the area of tourism development with currently, minimum public sector support for community-based initiatives (MoT, Citation2013). Ghana face challenges in Heritage planning national policy due to informal management structures and cultural politics and apparently detached from general development and urban planning policy (Fredholm, Citation2016).

4. Theorizing heritage preservation in Ghana

Article 5 of the UNESCO world heritage convention enjoins all member states including Ghana to ensure effective and active protection and preservation of cultural and natural heritage within their territory. Prior to this was a study of archaeology in Anglophone West Africa (Kense, Citation1990) which established the starting point of Ghana’s cultural heritage preservation in 1937, with the appointment of Thursan Shaw as a curator to manage heritage (conservation of antiquities and the restoration of architectural monuments) at the then Achimota College. In addition to antique and monuments preservation, is the use of Landscape Planning to preserve the environment, especially around palaces.

5. Heritage landscape planning

Heritage landscape planning is a work of local people to add value to the site and make it more significant to the community as enshrined in the operational guidelines for implementation of the World Heritage Convention (ICOMOS, Citation2011). An effective landscape planning and maintenance program was proposed by Detoh (Citation1992) for the environmental heritage preservation of traditional and cultural areas in Kumasi to enhance tourism development. Similarly, Amuah (Citation2002), expressed the need to improve landscape of Manhyia Palace, seat of the King of Asante. These studies (Amuah, Citation2002; Detoh, Citation1992) though a decade apart, focus on enhancing the surrounds of cultural heritage sites for tourism development and does not cover preservation of architectural fabric for the palaces.

6. Development of cultural centers and museums

Preservation of traditions and culture in Ghana has seen some thesis proposals for the design and development of Cultural center in Tema (Anim-Coleman, Citation1996), redevelopment of Centre for National Culture, Accra (Amegatcher, Citation1996), Museum for Ashanti Culture (Ayetey, Citation1998) and Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Tamale (Derban, Citation1998). These proposals fall in line with the core mandate of the Ghana Museums and Monuments Board (GMMB) to establish regional museums across the country but have yet to see light of day. However, two regional museums in addition to the national museum in Acccra, have been completed in Bolgatanga (1972) in the Upper East Region and Ho (1973) in Volta Region (GM, Citation2019). These design proposals establish the concept of heritage preservation whereby traditional architecture of the various sites are respected and protected as is evidently utilized in all the designs (Amegatcher, Citation1996; Ayetey, Citation1998; Derban, Citation1998) even though Tema as a community seem not to have a distinct culture due to the mixed ethnic nature with variety of influences (Anim-Coleman, Citation1996). Further heritage studies in Ghana has seen description of the development of the Kaleo Naa’s Palace at Kaleo near Wa in the Upper West Region (Anzagira, Citation2007) as a case study to a new palace design proposal. Effort was made to design the new Kaleo Naa’s Palace based on the indigenous local materials and construction method to promote the Dagaaba ethnic architectural heritage resource in Northern Ghana. Even though there seem to be a dwindling awareness to architectural heritage preservation in Ghana, it is important to note that the new design proposals place emphasis on originality and authenticity of the existing traditional architecture and attempts to improve on it by adding subsequent floors to meet demand for space while maintaining the old historic building.

7. Art in heritage preservation

In other heritage studies, Larbi (Citation2008), highlights the significance of motifs on Asante Temple walls in Ghana. The study revealed that the Asante Temples located at Abirem, Adako Gyaakye, Asenemaso, Besease, Ɛdwenease and Kentinkrono have existed over two hundred years to house deities. These Temples dates back to the eighteenth century and recognized as one of the two heritage sites on the UNESCO world heritage list, have motifs on its walls which carry significant proverbial and mythical messages to the people. Further research has been conducted to examine how motifs, raw materials and traditional technique have been utilized in Architecture, mural decoration and pottery in Sirigu (Wemegah, Citation2009). Located in the Kasina-Nankana Disrtict, Upper East Region of Ghana, Sirigu has a brilliant native science of building (Oliver, Citation2006) with motifs as murals on most of its walls and pottery as a major source of livelihood. Murals on buildings at Sirigu are not only artistic pieces but also act as a protective film layer rendered on the buildings against harsh weather conditions and an expression of belief which seeks to identify the people. Wemegah (Citation2009), focused on the artistic motifs cleverly applied on buildings and pottery and recommends further research or documentation into the material and construction methods and the need to add other facilities such as museum and guest facilities to boost tourism. The use of art in the preservation of cultural heritage is revealed among the people of Winneba and Mankesim in the Central Region of Ghana (Doughan, Citation2012). Inhabitants of Winneba and Mankesim seem not only to be aware of the association between art and heritage but also do not understand their importance and how the two are intertwined.

8. Awareness and documentation of architectural heritage

Seemingly, declining awareness and efforts to preserve cultural heritage has resulted in low standards in the operation of museums and inadequate documentation of heritage in Ghana. This is evident in a comparative study of the KNUST Museum and the National Cultural History Museum in Pretoria, South Africa (Glime, Citation2008). Though the bases for comparison seem somewhat flawed in terms of scope, including the date of establishment and ownership, the KNUST Museum rather exhibited shortfalls in almost all its activities required to properly function as a world class facility. The study undertaken by Doughan (Citation2012) focused on visual, performing and verbal arts and strongly recommends heritage preservation by creating awareness through documentation and consciously teaching the people about the importance of heritage. Amoako-Ohene (Citation2009), agrees to the need for documentation of cultural and natural resources in order to protect and preserve one’s heritage by researching into the establishment of museums to meet modern trends with capacity for the Asante culture. Apart from it not meeting modern trends, Museums in Ghana are unpopular as most people appear not to be aware of their operations and activities resulting in a less significant impact on the Ghana’s socio-economic development (Kuntaa, Citation2012).

9. Human resource and heritage management

Achamfuo-Yeboah (Citation2010), also proposes the creation of a center for preservation and further suggest the need for more museums and addition of a compulsory course on history of cultures at senior high school level with excursion sessions to boost interest and strengthen human resource for effective management of heritage resources in Ghana and Africa as a whole. Doughan (Citation2012), agrees to strict infusion of history and heritage to secondary and tertiary education to a large extent by suggesting that a stern action needs to be taken by the Ghana Education Service, West Africa Examination Council (WAEC), universities, scholars, chiefs and opinion leaders within communities. Interestingly, most of the fore fathers in Ghana and Africa did not go through formal education but managed to preserve cultural heritage (Traditional African Arts) to have an influence on African Architecture (Tetteh, Citation2010) with emphasis on painting, sculpture and general life styles of indigenous Africans and how these affect aesthetics in buildings.

Adaptive use of historic buildings is a major means for effective AHP and management. A research conducted to investigate the adoptive reuse of the “Old West African Court of Appeal Building” in Cape Coast, Central Region (Addo, Citation2013) indicated inter-relationship among politics, polemics and poetics in the management of monument conservation to maintain memory of space. Ghee (Citation2015) examines memory of the trans-Atlantic slave trade and preservation of the forts and castles in Ghana and posits that, preservation of the forts and castle can be properly achieved with the collective memory of what they have been used for by previous occupants from trade points through seats of government to prisons. Having a collective memory of the different uses of a building may not be too necessary as John Ruskin argue that preservation of a building is more concerned with maintaining originality and authenticity of the materials (Cannon, Citation2014).

There are some barriers hindering local planning authorities from organizing global-based programs on heritage and heritage management in Ghana. These barriers, both practical and conceptual, as examined by Fredholm (Citation2015) focuses on sustainable development of the built environment in Cape Coast, Central Region and reveals that there is an interconnection of heritage management with tourism and urban redevelopment. Some of the barriers include: lack of funding; political reasons; declining enthusiasm to invest and unwillingness to maintain authenticity due to easy access to imported foreign materials. Moreover, it is important to involve members of the community (stake holders’ participation) in the protection and preservation of heritage sites (Bruku, Citation2015). The discourse on the interconnection of heritage management with tourism seems to be well adopted by local planning authorities in Ghana while the interconnection with urban redevelopment projects are apparently neglected (Fredholm, Citation2016).

10. UNESCO world heritage criteria for listing

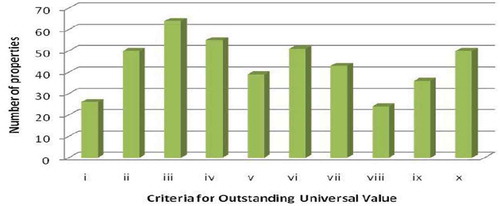

UNESCO World Heritage Committee (WHC) outlines ten (10) listing criteria for sites and structures in its Operational Guidelines 2012. These selection criteria have been classified into “cultural” (criteria 1 to 6) and “natural” (criteria 7 to 10) (UNESCO WHC, Citation2012). Sites from various countries are inscribed on the WHL only after nomination on a tentative list and must meet at least one or more of the ten selection criteria in order to be nominated or may be mixed (both cultural and natural). Figure indicates the criteria used by African State Parties to justify sites for outstanding universal value.

Figure 1. Analysis of criteria used by African State Parties. Source:.Abungu (Citation2009)

Figure shows that criteria (iii) is the highest frequently used followed by Criteria (iv) that requires an outstanding example of a type of building or architectural or technological ensemble or landscape which illustrates (a) significant stage(s) in human history; following Criteria (iv) are Criteria (vi) and (ii). While Criteria (vi) can be used on its own, the Committee recommends that where possible, it be used with another one.

An overview of the history of the nomination of cultural world by Deacon (Citation2014), revealed that the first sites in Africa to be inscribed on the WHL include Ethiopia’s Simien National Park, the Churches of Rock-hewn at Lalibela as well as Senegal’s Goree Island in 1978. Even though the World Heritage Committee (WHC, Citation1994) aims at ensuring a balance and representativeness in the WHL through OUV, majority (40.50%) of tentative listed sites from Africa are linked to European colonization of modern cities after the 15th century and slavery (Table ).

Table 2. Number and percentage of African sites in broad cultural categories on the WHL and approximate number on the Tentative List. Source: Deacon (Citation2014)

Table . Number and percentage of African sites in broad cultural categories on the WHL and approximate number on the Tentative List. Source: Deacon (Citation2014).

Deacon (Citation2014) study brings out African government’s low prioritization of heritage issues resulting in less skilled and resourced office staff; non-participation of community members in cultural heritage decision-making (Fredholm, Citation2016); lack of proper management arrangements needed to prepare sites based on the OUV and the right criteria before submission to UNESCO. President of ICOMOS, Michel Parent, was commissioned by the World Heritage Committee to study the criteria for early nominations and his study revealed that site are associated with persons as nominations are based on scholars, artists, writers or statesman. Parents however, feared sites which serves as an unfortunate memory of exploitation of mankind through slavery and symbol of cruelty to humanity such as the Island of Goree in Senegal and Auschwitz Birkenau in Poland respectively. This study led to the change of listing based on “persons” and “historical importance” to ‘Universal Significance” to the extent that a property should be “directly or tangibly associated with events or ideas or beliefs” in 1980. The world heritage criteria especially criterion six has gone through series of amendments from 1979 to date as it currently states that; “a property should be directly or tangibly associated with events or living traditions, with ideas, or with beliefs, with artistic and literally works of outstanding universal significance.” The GMMB has made effort over the years to add on to the two items on the WHL by having six more items currently on the UNESCO tentative list. The six tentative sites nominated by the GMMB in 2015 to be enlisted by the UNESCO World Heritage Centre include the Kakum National Park, Mole National Park, Navrongo Catholic Cathedral, Nzulezu Stilt Settlement, Tenzug-Tallensi Settlements and the Trade Pilgrimage Routes of North-Western Ghana due to their historic and cultural values (criteria 1 to 7) (GMMB, Citation2015).

11. Conclusion and recommendation

All the research works reviewed has an inherent voice yearning for the preservation of cultural (Architectural) heritage not only for tourism but also for sustainable urban redevelopment in Ghana which the present researcher’s thesis seeks to achieve. Ghana undoubtedly has enormous economically viable heritage sites but lacks the needed support to achieve its full potential (Kuntaa, Citation2012). From the literature reviewed, it took Ghana thirty-five years after the last site was listed to nominate some more sites, which after almost forty years, has yet to be considered on the WHL. Even though the GMMB has submitted some historically important sites for consideration by UNESCO, Ghana does not have a documented national heritage list and management systems for preservation of the existing listed sites. Unfortunately, the aim of GMMB to establish museums in every region has seen only three in greater Accra, Upper East and Volta regions with majority (Thirteen) regions yet to be developed. It was realized that there is a weak human resource in heritage studies and management in Ghana attributing it to lack of a course in heritage studies at the secondary school level (Achamfuo-Yeboah, Citation2010). This leaves room for further studies to be conducted to be able to add more and properly manage the two items listed for Ghana on the WHL.

Some of the recommendations by Kuntaa (Citation2012) point toward increasing publicity of museum activities in Ghana and this calls for further research into the awareness of heritage sites by Ghanaians amidst demolishing of historic sites in the urban areas (Adarkwa & Oppong, Citation2005).

African Architecture (Tetteh, Citation2010) and for that matter, Ghana’s Architectural heritage is not clearly defined in the reviewed studies making it imperative for a research to delve into this area. Amidst the huge piles of debris owing to teardown of historic (traditional) buildings (Twumasi-Ampofo & Oppong, Citation2016), adoptive re-use (Addo, Citation2013) is an important consideration in the preservation of architectural heritage in Ghana and therefore calls for further research. If properly embraced, adaptive reuse will help preserve architectural heritage and reduce rate of demolition in urban areas. Ten years after Abungu (Citation2009) study, there could be some changes in the analysis and needs further research to ascertain current trends in the frequently used criteria to justify sites for outstanding universal value.

This paper therefore recommends further research to address the following issues: improving heritage landscape for tourism, development of cultural centers and museums, encouraging the use of art for heritage preservation, raising awareness of the preservation of architectural heritage (historic buildings and sites), documentation of heritage, human resource responsible for AHP, true architectural heritage and establish traditional management systems for heritage preservation in Ghana.

correction

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

K. Twumasi-Ampofo

Twumasi-Ampofo, Kwadwo Kwadwo Twumasi-Ampofo is an Architect, member of the Ghana Institute of Architects (GIA). He is a Senior Research Scientist and Head of Built Environment Division of the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research – Building and Road Research Institute (CSIR-BRRI), Kumasi. Arc. Twumasi-Ampofo has several years of experience in architectural practice and has been involved in wide range of architectural projects. He is currently a PhD. candidate at the department of Architecture, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in Kumasi, Ghana. He is researching in History of Architecture and Heritage Preservation and Management. The research seeks to address a national issue with the current urban redevelopment which seems to ignore preservation of monuments, historic buildings, and sites and poor management of existing listed world heritage sites in Ghana.

References

- Abungu, O. (2009). World heritage tentative list for Africa: Situational analysis. A study carried out for the Africa World Heritage Fund (AWHF). Okello Abungu Heritage Consultants.

- Achamfuo-Yeboah, C. (2010). Preservation of our Cultural Heritage: The Case of Museums as Educational and Economic Centres [A Thesis Submitted to the Department of Architecture Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Award of Master of Architecture Degree]. College of Architecture and Planning, KNUST, Kumasi.

- Adarkwa, K. K., & Oppong, R. A. (2005). Gentrification, Use Conversion and Traditional Architecture in Kumasi’s Central Business District - Case Study of Odum Precinct. Journal of Science and Technology, 25(2), 80–11. www.ir.knust.edu.gh

- Adarkwa, K. K., & Oppong, R. A. (2007). Poverty reduction through the creation of a liveable housing environment: A case study of Habitat for Humanity International housing units in rural Ghana. Property Management, 25(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.1108/02637470710723236

- Addo, N. O. (2013). Politics, Polemics and Poetics of Monument Conservation in Ghana: Investigating the Adaptive Reuse of the 19th Century “West African Court of Appeal” Building, Cape Coast. A Dissertation Presented to the Department of Archaeology and Heritage Studies, University of Ghana, Legon.

- Adom, P. K., & Bekoe, W. (2012). Conditional dynamic forecast of electrical energy consumption requirements in Ghana by 2020: A comparison of ARDL and PAM. Energy, 44(1), 367–380. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2012.06.020

- Amegatcher, H. O. (1996). Redevelopment of Centre for National Culture – Accra [A thesis submitted to the Board of Postgraduate Studies, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the award of Postgraduate Diploma in Architecture]. College of Architecture and Planning, KNUST, Kumasi.

- Amoako-Ohene, K. (2009). Museums in Asante [A thesis report submitted to the School of Graduate Studies, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in African Studies]. Department of General Art Studies, College of Art and Social Sciences, KNUST, Kumasi.

- Amuah, J. (2002). Improving on the landscape of Manhyia Palace to enhance tourists’ attraction [A thesis submitted to the School of Postgraduate Studies, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi Ghana in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the award of Master of Science in Landscape Studies]. College of Architecture and Planning, KNUST, Kumasi.

- Anim-Coleman, A. K. (1996). Tema Cultural Centre [A thesis submitted to the Board of Postgraduate Studies, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the award of Postgraduate Diploma in Architecture]. College of Architecture and Planning, KNUST, Kumasi.

- Anquandah, J. (1999). Castle and Forts of Ghana. Ghana Museums and Monuments Board.

- Anzagira, L. F. (2007). The New Kaleo-Naa’s Palace at Kaleo, Upper West Region, Ghana; an Emblem of Dagaaba Traditional Architecture [A thesis submitted to the Department of Architecture, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the award of Master of Architecture]. College of Architecture and Planning, KNUST, Kumasi.

- Anzagira, L. F., Badu, E., & Duah, D. (2019). Towards an Uptake Framework for the Green Building Concept in Ghana: A Theoretical Review. International Journal On: Proceedings of Science and Technology, Resourceedings, 2(1), 57–76.

- Ayetey, O. (1998). Museum for Ashanti Culture [A thesis submitted to the Board of Postgraduate Studies, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the award of Postgraduate Diploma in Architecture]. College of Architecture and Planning, KNUST, Kumasi.

- Bavir, M., & Rhodes, R. A. W. (2012). Interpretivism and the analysis of traditions and practices. Critical Policy Studies, 6(2), 201–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2012.689739

- Bruku, S. (2015). Community engagement in Historical Site protections: Lessons from Elmina Castle Project in Ghana. Conservation and Management of Archeological Sites, 17(1), 67–76. https://doi.org/10.1179/1350503315Z.00000000094

- Cannon, B. Z. (2014). Disappearing Walls: Architecture and Literature in Victorian Britain [A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English]. Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley.

- Christiansen, I., Bertram, C., Land, S., Dampster, E., & James, A. (2010). Understanding research (Third ed.). University of Kwazulu-Natal Press.

- Darko, A., & Chan, A. P. C. (2016). Critical analysis of green building research trend in construction journals. Habitat International, 57, 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2016.07.001

- De la Torre, M. (2013). Values and heritage conservation. Heritage & Society, 60(2), 155–166. https://doi.org/10.1179/2159032X13Z.00000000011

- Deacon, J. (2014). An overview of the history of the nomination of cultural world heritage sites in Africa. The Management of Cultural World Heritage Sites and Development in Africa, Springer.

- Derban, D. K. (1998). Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Tamale [A thesis submitted to the Board of Postgraduate Studies, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the award of Postgraduate Diploma in Architecture]. College of Architecture and Planning, KNUST, Kumasi.

- Detoh, M. K. (1992). Landscape planning of four traditional and cultural areas in Kumasi and the relationship to the development of tourism [A thesis submitted to the Board of Postgraduate Studies, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, in partial fulfilment of the requirement for the award of the Degree of Master of Science in Landscape Design]. College of Architecture and Planning, KNUST, Kumasi.

- Doughan, J. E. (2012). The Use of Art in the Preservation of History: A Case Study of Winneba and Mankessim [A thesis submitted to the Department of General Art Studies, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy (African Art and Culture)]. Faculty of Art, College of Art and Social Sciences, KNUST, Kumasi.

- Fredholm, S. (2015). Negotiating a dominant heritage discourse. Sustainable urban planning in Cape Coast. Ghana. Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development, 5(3), 274–289. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCHMSD-04-2014-0016

- Fredholm, S. (2016). Assets in the Age of Tourism: The Development of Heritage Planning in Ghanaian Policy. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 34(4), 498–518. https://doi.org/10.1080/02589001.2017.1285011

- Ghana News Agency – GNA. (2012). Ghana Needs Cultural Heritage Policy – Archeology Lecturer. Ghana Business News. Retrieved January, 2019, from. http://www.ghananewsagency.org/education/ghananeeds-cultural-heritage-policy archeology-lecturer-45637

- Ghee, B. D. (2015). Foundations of Memory: Effects of Organizations on the Preservation and Interpretation of the Slave Forts and Castles of Ghana [A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Public History]. College of Arts and Sciences, University of South Carolina. Retrieved January, 2019, from. http://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3716

- Gholitabar, S., Alipour, H., & Martins da Costa, C. M. (2018). An Empirical Investigation of Architectural Heritage Management Implications for Tourism: The Case of Portugal. Sustainability, 10(93), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10010093

- Glime, G. Y. A. (2008). A Comparative Study of the National Cultural History Museum, Pretoria (S. Africa) and KNUST Museum, Kumasi [A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in African Art]. Department of General Art Studies, College of Art and Social Sciences, KNUST, Kumasi.

- GM. (2019). Ghana National Museum. Accra: Ghana Museums and Monuments Board. Retrieved March, 2019, from. http://www.ghanamuseums.org/national-museum.php

- GMMB. (2015). Terms of Reference for the Development of a Strategic Framework and Implementation Plan for the Ghana Museums and Monuments Board (GMMB). Accra: Ghana Museums and Monuments Board. Retrieved January, 2019, from. www.ghanamuseums.org

- Graham, B., Ashworth, G. J., & Turnbridge, J. E. (2000). A Geography of heritage. Arnold.

- Henning, E. (2004). Finding your way in qualitative research (First ed.). Van Schaik Publishers.

- ICOMOS. (2011) . World Heritage Cultural Landscapes.

- Jenkins, P., Smith, H., & Wang, Y. P. (2007). Planning and housing in the rapidly urbanizing world. Rutledge. In Nick, G., & M. Tewdwr-Jones (Eds.) (pp. 223-227). New York: Routledge.

- Kense, F. J. (1990). Archaeology in Anglophone West Africa. In P. Roberstshaw (Ed.), A History of African Archaeology (pp. 135–154). James Currey.

- Kuntaa, D. D. (2012). The Museum in Ghana: Their Role and Importance in Ghana’s Social and Economic Development [A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, in partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in African Art and Culture]. Faculty of Art, College of Art and Social Sciences. KNUST, Kumasi.

- Lah, L. (2001). From Architectural Conservation, Renewal and Rehabilitation to Integral Heritage Protection (Theoretical and Conceptual Starting Points). Urbani Izziv, 12(1), 129–137. https://doi.org/10.5379/urbani-izziv-en-2001-12-01-004

- Larbi, S. (2008). The Cultural and Aesthetic Significance of Motifs on Selected Asante Temples [A Thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in African Art, Department of General Art Studies]. College of Art and Social Sciences, KNUST, Kumasi.

- Lawless, J. W., & Silva, K. D. (2017). Towards an Integrative Understanding of ‘authenticity’ of cultural heritage: An analysis of World Heritage Site designations in the Asian Context. Journal of Heritage Management, 1(2), 148–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/2455929616684450

- McMorran, C. (2008). Understanding the ‘Heritage’ in Heritage Tourism: Ideological Tool or Economic Tool for a Japanese Hot Springs Resort? Tourism Geographies, 10(3), 334 354. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680802236329

- MoT. (2013). Ministry of Tourism. National Tourism Development Plan 2013-2027. Government of Ghana.

- Njoh, A. J. (2006). African cities and regional trade in historical perspective: Implications for contemporary globalization trends. Cities, 23(1), 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2005.07.009

- Nyarko, K. R. (2018). Destruction of Ghana’s Heritage Sites Worrying. General News, Modern Ghana. Retrieved June, 2020, from. www.modernghana.com

- Olanrewaju, D. O. (2001). Urban infrastructure: A critique of urban renewal process in Ijora Badia, Lagos. Habitat International, 25(3), 373–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0197-3975(00)00042-4

- Oliver. (2006). Built to meet needs: Cultural issues in vernacular architecture. Elsevier.

- Oppong, R. A., & Brown, A. (2014). Teardowns, Upgrading and an Emerging Paradigm of Building Property Finance in Kumasi, Ghana. Journal of African Real Estate Research, 2(1), 24–57. www.afrer.org

- Rahman, N. A., Halim, N., & Zakariya, K. (2018). Architectural Value for Urban Tourism Placemaking to Rejuvenate the Cityscape in Johor Bahru. Proceedings of 2nd International Conference on Architecture and Civil Engineering (ICACE 2018), Penang, Malaysia. IOP, 1 10.

- Tetteh, F. S. (2010). The Influence of Traditional African Art on African Architecture [A Thesis submitted to the Department of Architecture, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture]. Faculty of Architecture and Building Technology, College of Architecture and Planning. KNUST, Kumasi.

- Timothy, D. J., & Boyd, S. W. (2003). Heritage tourism. Prentice Hall.

- Tipple, A. G., Korboe, D., Willis, K., & Garrod, G. (1998). Who is building what in urban Ghana? Housing supply in three towns. Cities, 15(6), 399–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-2751(98)00036-5

- Twumasi-Ampofo, K., & Oppong, R. A. (2016). Traditional Architecture and Gentrification in Kumasi Revisited. African Journal of Applied Research, 2(2), 97–109. https://www.ajaronline.com

- UNESCO. (2018). World Heritage List. UNESCO World Heritage centre. Retrieved December, 2018, from. http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/stat/

- UNESCO WHC. (2012). Intergovernmental Committee for the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. Operational guidelines for the implementation of the World Heritage Convention. World Heritage Centre 12/01 July 2012. UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

- Van Dantzig, A. (1980). Forts and Castles of Ghana. Sedco Publishing.

- Walliman, N. (2011). Research Methods, the Basics. Routledge.

- Wemegah, R. (2009). Architecture, mural decoration and pottery in sirigu culture [A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in African Art and Culture]. Department of General Art Studies, KNUST, Kumasi.

- WHC. (1994). World heritage committee. Convention concerning the protection of the world cultural and natural heritage (18th Session).