Abstract

This research investigated, analysis, and survey on the satisfactory levels of local organizations and community leaders in Sawankhalok district with a proposed master plan to develop strategic models for creative tourism. Situated in Sukhothai province, the area sheltered Sawankhalok—Si Satchanalai Historical Park, one of UNESCO World Heritage sites in Thailand. Linked to the objectives of sustainability and co-creation of the United Nations, to improve the quality of life and sustainable economy while seeking to recover the historical link among culture, co-creation development, and sustainability while the area is currently represented in a state of fragment and disconnect between three important areas. Based on this context, this paper analyzes the main problems and studies through “Cs” Coordination, Cooperation, and Collaboration strategy method and interviewing on focus group and future procedure. After the implementation and operational framework on the Sawankhalok Master plan for Tourism journey in World Heritage areas of Historical districts Sukhothai—Si Satchanalai and Kamphaeng Phet, the result shows that the plans and projects were able to develop the management on the cultural and historical tourism while creating a common ground for multi-parties in the area. Similarly, the strategic drafting found that the vision of the Sukhothai and associate towns World Heritage was to sustainably and co-creation the values of the Sukhothai and associate towns World Heritage.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The research paper about a proposed master plan to develop strategic models for creative tourism in Sawankhalok located in Sukhothai province, surrounding by Historical Park, one of UNESCO World Heritage sites in Thailand. Following the objective of sustainability and co-creation of the United Nations. The reflection on the Sawankhalok Master plan for Tourism journey in World Heritage areas of Historical districts Sukhothai—Si Satchanalai and Kamphaeng Phet to create a holistic paradigm that focuses on the capacity of culture to improve the quality of life and seeks to recover the historical link among culture, co-creation development, and sustainability.

1. Introduction

Subsequently, the outcomes from the said inquiries were further explored in terms of strategic means to foster tourism through the criteria of 1) co-creation; 2) sustainability; and 3) community-heritage engagement values. Operating on the premises of interpretive and systematic approaches, the research relied on questionnaires and focused group interviews to collect data from five organizations and thirty community leaders. Employing the methods of frequency, percentage, arithmetic means, and standard deviation, the statistical analyses revealed the following findings. First, to devise valid strategic models to accommodate tourism, the mission statements should contain well-defined objectives and modes of conceptualization. Second, their formulation should involve all important stakeholders via the principles of co-ordination, co-operation, and collaboration. Third, the implementations of these models should incorporate assessments on their success as well as satisfactory levels from both the local populace and other scholars in relevant academic fields. Such evaluations, in turn, provided a ground to conclude that the proposed master plan to promote creative tourism in Sawankhalok was highly effective. since it enabled community leaders and other stakeholders to apply their practical knowledge to work together, as demonstrated by a pilot project that resulted in the creations of tourist information maps in the district.

1.1. Contextual background

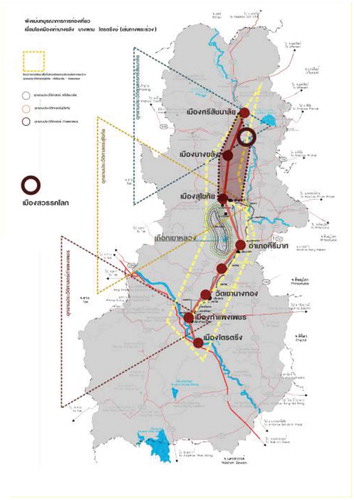

As illustrated by Shibayama, Yanagisawa, and Moore, a pathway–called the Khmer Road–linking many archaeological sites in the present nation-states of Laos, Thailand, and Myanmar had existed since the Angkor Empire (802–1431), long before international borders in Southeast Asia were drawn (Figure ). In the area known as Siam that had evolved into Thailand today, an extended passageway named–Phra Ruang Route or Sukhothai Road–provided a vital connection among three urban settlements in the lower northern region of the country, which were Sukhothai, Sawankhalok, Si Satchanalai, and Kamphaeng Phet (Figure ). (Shibayama et al., Citation2013).

Figure 2. A map reconstructing the Phra Ruang Route or Sukhothai Road linked Sukhothai, Sawankhalok, Si Satchanalai and Kamphaeng Phet

Between the 13th and 15th century, the triad cities were integral parts of Sukhothai Kingdom (1238–1438), sharing a common political system, social structure, and cultural root under the same metaphysical belief and spiritual practice. With respect to Sawankhalok- Si Satchanalai in particular, its historic quarter contained the ruins of an ancient urban settlement once called Mueang Chaliang, which served as a second administrative centre of Sukhothai Kingdom.(Fine Arts Department (FAD), Citation2013) From the 13th to 17th centuries, the town became a major trading and manufacturing hub for pottery and glazed ceramics called Sangkhalok wares (celadon) for Sukhothai and the subsequent regime, the Kingdom of Ayutthaya (1351–1767).(Lau, Citation2004)

Due to such historical ties, Sawankhalok-Si Satchanalai Historical Park–together with Sukhothai and Kamphaeng Phet counterparts–constituted the Historic Town of Sukhothai and Associated Historic Towns that were collectively registered as a tripartite UNESCO World Heritage site in Citation1991. In order to provide a comprehensive guideline for sustainable developments of the aforementioned locales and their vicinities, a great amount of attention had been paid on the measures and mechanisms to preserve the local histories, culture, ways of lives, along with traditional practices by the indigenous people who resided in communities around those UNESCO sites, especially in the socio-economic dimension. In this regard, obvious examples could be seen from contemporary studies on the conservations of waterfront markets to accommodate creative tourism in the lower northern part of the country that not only: 1)incorporated public participations in all stages in the process of sustainable development,(Office of the National Economic and Social Development Board (NESDB) and Thailand Creative and Design Center (TCDC), Citation2009) ranging from community to municipal and regional stages; but also 2) acted in accordance with collaborative strategies, both at the national and international levels as stipulated by the socio-economic policies of the current Prayut Chan-o-cha government (2014–present).(Prayut Chan-o-cha, Citation2014) Research strategies developed from the conceptual framework, principles and theories. Which is accepted internationally to create a suitable mechanism for driving and developing in the world heritage area.

The character of local community in World heritage areas, are involved within tangible and intangible cultural heritage. This culture inherits through community members for a long time. An understanding of identity and authentic character of community which is an invaluable resource of their society has a high potential to establish a strong bond of community for a purpose of sustainable tourism in world heritage areas. While a Community’s Leader and Government officers who responsible for engagement and conservation strategy. They are also ready to cooperate and engage with heritage project and community.

1.2. The impact of UNESCO international regulations

Globalization and World Heritage Conservation have five main points on ethics and globalization. The process of evolution of globalization Important issues of globalization in economy, communication, and electronics, related to UNESCO—as part of the UN—seeks to promote global ethics Adoption of legal tools established in accordance with six international standards, UNESCO strives to create a balanced global economy, in particular, to protect the diversity of cultural expression. In other words, countries should have the right to subsidize their cultural industries and take measures to preserve and promote their cultural identity.

And the World Heritage Convention has highlighted our responsibility to preserve heritage, which is an important ethical tool at the UNESCO Convention. Moreover, the World Heritage property testifies to the history of globalization. Some world heritage sites are directly linked to the fundamental values of global ethics that have disappeared in our time[Footnote1].

1.3. UNESCO sustainable development strategies

1.3.1. Community involvement strategy

The World Heritage Area was established through the cooperation of many groups. The area involved with many stalk holders that seek different interests, while people or groups with different Interests meet, conflicts are inevitable to happen in the area. In the context of world heritage, conflicts tend to occur at different levels between different stakeholders and local politicians. Similarly, many community advisor relevant parties and related governments prefer to increase international reputation and tourism business by nominating their area as a world heritage site. “Community participation” is not only necessary in the nomination process. But it also necessary to manage conflicts of different stakeholders. The concepts of stakeholders in this context are holistic, consisting of individuals, institutions, and organizations at different levels and with different backgrounds in the World Heritage area. [Footnote2]

1.3.2. Credibility strategy

‘Strengthen the credibility of the World Heritage-listed areas as a representative and balanced geographic evidence of the cultural and natural properties of an outstanding international value‘, the main objective of this strategy to promote culture and world heritage sites to be more internationally accepted. That means the geographic inequality that exists, the type and content in the heritage site. Inequality has existed since the nomination for world heritage began in 1978 due to the dominance of nominations as a World Heritage Area in Europe. The majority of European heritage consists of cultural heritage, which causing an imbalance between cultural and natural heritage sites. The uneven distribution of cultural and natural tourist sites around the world reflects the inequality of tourist destinations by category. Group to determine outstanding universal values.

1.3.3. Conservation strategies

An additional strategy adopted in Budapest in 2002 is conservation. The Budapest Declaration aims to: “Ensure effective conservation of a world heritage”, and what is understood as effective and how it should be implemented is unclear from the definition of this strategy. However, in the context of past experience, sustainability must be given special consideration.

Conservation, which aims at sustainability, should use proven technology, including appropriate use for local conditions, as many examples show that preserving heritage, preserving culture and natural heritage. It’s a political and participatory process that requires a variety of experts. Therefore, preserving the heritage is possible through interdisciplinary cooperation. In this regard, it has the same requirements that are concealed in the five strategies of the “strategy”.

1.3.4. Capacity-building strategies

Strategies for capacity building are capacity building According to the Budapest Declaration, the goal of capacity building ‘To promote the development of effective capacity-building measures, including assistance in preparing the nomination for the World Heritage List for understanding and implementation of the World Heritage Convention and related instruments. Realize that empowerment is a long-term and ongoing process in which all stakeholders are involved. To be able to interpret this strategy, we need to realize that capacity building includes education at different levels and for different target groups. Education must also take into account the educational context, history, philosophy and politics. Therefore, capacity building is quite a complex goal that must be achieved in the short term. At the first level, management and capacity-building with future-oriented approaches In general studies of world heritage and heritage management and conservation strategies still lack world-class experts in these fields. Therefore, there is an urgent need for training in higher education institutions. Instructors from universities around the world dealing with heritage management training and conservation training and practitioners in the field should collaborate on the development of heritage management training concepts. These concepts should include Developing management skills or teaching standard Methods, either the concept of interdisciplinary conservation of heritage sites or operations in the development of tourism needs.

In the second level, education and capacity building with different target groups are more practical. This level refers to the management of heritage areas and related problems. Which became an important factor for economic and social development with the growing conflict between the prevention and use of stakeholder resources, learn how to explore the possibilities and limitations of participation of various target groups. Therefore, it is necessary to define and develop the participation model needed for the lasting balance of “Giving and Receiving”. The mission of educational institutions and universities is to transfer science, technology, knowledge, and creativity to those concepts.

At the third level, education and capacity building are focused on the future of education in the academic institution that related to the field of heritage. Teaching staff and educational planners from national and international educational institutions must be well prepared to develop and incorporate world heritage content into educational programs, and have sustainable learning about world heritage. This concept must be implemented with all sectors and experts in education and curriculum development. For raising awareness and consciousness of future generations.

1.3.5. Communication strategy

Communication strategy in the Budapest Communications Declaration means: “Increase public awareness, participation and support for world heritage through communication” (WHC, Citation2005a) in the World Heritage Treaty. (Cooperation initiative) in communication and education, focusing only on computers basic communication strategy in addition, the implementation of the strategic goals of communication is supplemented by traditional communication in the museum, including photo production and archiving in the database. Not least, these efforts were successful in creating they have succeeded in expanding these activities to the community and municipality and improving the overall legacy presentation strategy in various media.

Relevant network partners must be able to implement all five strategies under the World Heritage Sustainable Development Strategy. In the other hand, they must be encouraged in their factors and enhance their personal experience and be able to understand, interpret, and manage world heritage sites including protection and sustainable use of world heritage sites feeling and acting responsibly to the world heritage every type is a challenge for future development and is possible only when the goals are accepted by both individuals and communities. Therefore, personal and collective is the responsibility for sustainable community development.

2. Research and development theory

2.1. Community development and propulsion mechanism with the three “Cs” Coordination, Cooperation, and Collaboration strategy

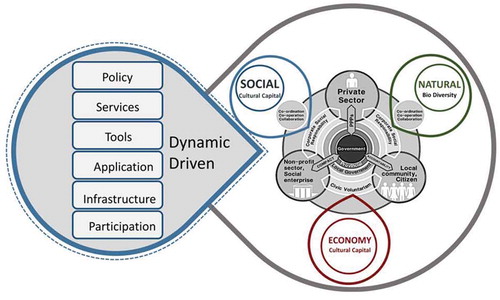

In order to facilitate teamwork with the local populace, all important stakeholders, key individual informants, in combination with other experts, specialists, and scholars in relevant academic fields, forming a network of knowledgeable persons, the proposed Creative Tourism Strategy Model depended on the notions of Coordination, Cooperation, and Collaboration, (3Cs)–drawn from inquiries into the processes of group participation from a wide range of studies in social sciences–as its modus di operandi.[Footnote3] The 3Cs framework was applied to the creation of the model in accordance with Rockwood’s ideas of cooperative, collaborative, and coordinative learning,(Rockwood, Citation1995a, Citation1995b) as explicated below.

First, co-ordination denoted a methodology of choice for acquiring foundational knowledge via a well-structured lesson, such as a group assignment to explore a variety of topographic maps and aerial photography portraying geological features of the communities around Si Satchanalai. Second, coordination signified a well-defined normative methodology, exercised to regulate a systematic knowledge that was socially constructed. Operating in concert with collaboration and cooperation, an example of coordination encompassed peer-assisted activities, such as organising wokshops, discussion groups, and public hearings for data collections from all concerned parties. Third, collaboration referred to a methodological approach for developing knowledge that dwelled less on factual content but more on analytical, interpretative, and critical aspects. Obvious applications of collaboration were exemplified by the creations of spatial maps in analysing and synthesising the contents of the Creative Tourism Strategy Model.

Figure 4. A diagram exhibiting the mechanism of the Participatory Theory serving as a modus operandi for the Creative Tourism Strategy Model

As depicted in Figure , it became apparent that the 3Cs framework was fundamental for engineering the technical capabilities on user interactive of the Creative Tourism Strategy Model. Moreover, since the 3Cs approach also referred to a learning model, by which diverse factions of stakeholders teamed up to carry out a meaningful research project.(Howard Gardner, Citation1993) Such an observation was evident from the fact that the group of KMITL researches worked together with the local inhabitants, business entrepreneurs, social organizations, district administration–as well as various state agencies involved with tourism safety–in generating the Creative Tourism Strategy Model. Hence, a practical connection to the position of participation theory was palpable, as shown by the below discussions.

2.2. Participatory theory

From above idea, both the development of the Creative Tourism Strategy Model and its implementation necessitated collaborative endeavours from various groups of people. For that reason, Participatory Theory lent a ground to cultivate united contributions from the public and private sectors, as well as civil society, of which involvements could be organized into three hierarchical tiers at: 1) Local community level; 2) Provincial or City level; and 3) Country or national level.(World Health Organization (WHO), Citation2002). At each level, five methods to efficaciously process participations could be exercised through the mechanisms of: 1) Network coordination; 2) Agenda and strategic formations; 3) Observant and evaluative systems; 4) Knowledge management and dissemination; and 5) Social communication and public relations. In brief, all the five participatory mechanisms also required constructive engagements by means of party networking with strategic partners in the government, academia, private sector, civil society (including NGOs), and mass media (Figure ).With respect to the Creative Tourism Strategy Model, a participatory planning for its creation along with the accompanying enterprise could be defined as cooperative undertakings between the denizens of Sawankhalokand KMITL research team, whose common objectives consisted of: 1) shaping their development plans; and 2) selecting the best courses of actions for their implementations (Figure ). The model for the development of a mechanism to drive the community by using appropriate technology as shown in the picture

2.3. Studying of Urban and rural zoning design strategy

The character of three heritage area situates in a peri-urban area, meaning of peri-urban according to the research “The peri-urban is a zone of social and economic change and restructuring, a zone of intensive and sometimes even chaotic development. it is a new hot-spot multi-functional landscape for urban renewal and development.”(Nilsson et al., Citation2014). In the future, Urban sprawl phenomenon will create large impact on rural areas, Peri-urban could become a solution to create balance between both areas. This might provide possible engagement in many activities for agriculture and community to create eco-development and environment conservation. The collaboration between human, animal, and nature could answer the need for people, economy, and environment. Peri-urban design is expected to give methodology to shape rural and urban landscape. For example, climate change, food production, water resources for a rapid growth of world population (Thorbeck & Troughton, Citation2016). Urban and rural design has many similarities, including embracing those unique characteristics of design ideas that accept social and cultural values in order to enhance the quality of life. Urban and rural design are design methods to solve suburbs or peri-urban problems and solve suburbs or peri-urban needs. In this research, apply use the idea of space management to create landscapes and how community participation (Figure –). Rural design helps local people deal with social change and improve the organization in the suburbs and rural people livelihood to improve the quality of life—urral (urban + rural) and ruban (rural + urban)

Rural design, when applied to this research, connects to the suburbs, providing:

- Design thinking information to local policymakers about the spatial, ecological, and ethical impacts of various options and options that local people make;

- Community-based design process to empower people to shape the future such as Community-based tourism;

- Take advantage of new technologies to create synergy and entrepreneur-ship Through links and systematic connections;

- Understanding of livelihood assets and development quality of life and balance.

- Using Human-centric design and community engagement as design strategy for peri-urban area.

2.4. Cultural of rivers connections between the Yom Basin and the Ping Basin

The issue problems of water sharing, flood management and drought cause conflicts and tend to become major regional political challenges. In this context, the cultural allocation of rivers and the delicate knowledge of these environments is essential. To anticipate future changes and to find a balance between population needs and resource conservation, knowledge on water and resource management for civil society and stakeholders are essential. This research provides a comprehensive survey of this information, especially a relationship of local people and river of Yom and Ping River (Figure ).

In the frame of mind “Rivers and World Heritage” share the concerns of the river’s cultural pioneering process and realize global realities. The aim is to provide a network for the existing experience to improve the culture of the river, thus promoting innovation in the area of local development and governance. This research will consider both (a) the function of river ecosystems under the influence of development techniques and (b) topography as a result of continuous interaction between societies. Culture and Environment knowledge gained will be the basis of the transfer to the developer/manager of skills in sustainable management of natural resources, biodiversity conservation and landscape improvement for linking strategies

3. A development strategy for future Creative tourism in World heritage sites

3.1. Interviewing on focus group and future procedure for master plan development

During conduct of this research paper, Interviewing was used to understand specific context of these world heritage sites through different groups of local in the area such as private sector, Government Sector, and head of community. This allowed researcher to receive a wider perception for a benefit of the project. While the participation and real engagement is the only option to increase a possibility for the project would be able to establish, while the workshop allows to locate a common ground for different parties in these sensitive areas. After understanding the basics with the people groups and network partners in all relevant communities, they be able to take the main steps. To drive activities from the master plan are as follows:

3.2. Sustainable Co-creation

3.2.1. The participation processes, interview method on a focus group

3.2.1.1 Coordination of community representatives, local leaders and network partners for policy making, planning, and creating a drive mechanism

3.2.1.2 Cooperation of community representatives, local leaders and network partners for support of work and operations

3.2.1.3 Collaboration among the public sector, Government and network partners for carrying out various activities to achieve goals efficiently and appropriately.

3.2.2. sustainability processes

3.2.2.1 Sustainable co-creation must reduce dependence on other people’s resources as a factor for success.

3.2.2.2 Sustainable co-creation must reduce the dependency of any particular group of people as a factor of success.

3.2.2.3 Sustainable co-creation must avoid providing incomplete information. And untrue, causing misunderstanding to the point of belief and value

3.2.2.4 Sustainable co-creation must avoid attempts to stop creative ideas, including open-minded needs. Reveal

The selection process of the 4 appropriate sustainable value creation models

Format 1: Within a group of experts who started the project Carefully select Stakeholders to participate in Co-production/Co-creation.

Format 2: Open for all (Open for all) The originator of the project gives the opportunity for Co-production/Co-creation. Unlimited

Format 3: Value star, the initiator to persuade allies to join co-create with only certain groups of stakeholders.

Format 4: Value network (Value constellation) The originator of the alliance gives the opportunity for Co-production/Co-creation. Without blocking and not limited to groups For example, the Smart tourism project can be considered “Value network/value constellation” to enable tourists to participate in co-production

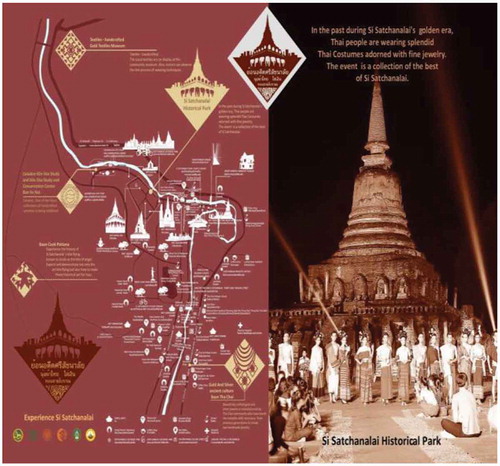

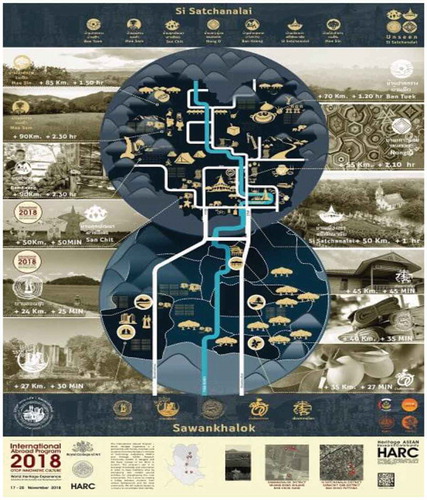

Figure 9. Local area mapping of information on creative tourism at Sawankhalok-Si Satchanalai Historical Park

In a corollary view, it could be conceptualized that the aforementioned activities indeed incorporated a two-way learning process via dialogues, negotiations, and decision-makings between the insiders (dwellers of Sawankhalokdistrict) and outsiders (KMITL researchers along with other experts, specialists, and scholars), namely in terms of the tasks to be performed by the former and supports provided by the latter. Through such academic and party networking, the so-called “negotiating dialogue”(Vasconcelos et al., Citation2009) between the two parties might result in mutual agreements on applying the Creative Tourism Strategy Model to 1) accommodate the needs of local populace; 2) overcome their collaborative conflicts and participatory constraints; and 3) explore new opportunities that benefited both sides alike.

On that account, a remark could be made that the proposed Creative Tourism Strategy Model could enable state officials, local community leader, and tourism planners to mobilize communities in Sawankhalok district into action to partake in broadening the scope of services offered to the industry.(Mektrairat, Citation2014) Its ultimate goals were to institute socio-economic empowerment for the local inhabitants, while providing a value-added experience for outside visitors. Accordingly, new niches for creative tourist destinations in Sawankhalokwould emerge, notably for natural, cultural, and historical-oriented travellers.

In addition, another reflection could be put forward that the Creative Tourism Strategy Model incorporated two dimensions of the temporal objectives. First, it was devised to formulate a long-term development framework for quality tourism (with a timeframe spanning from ten to twenty years), containing a wide range of emphases the acts of policy and strategy making, planning, extending, corporation, constitution and coordination, product development and diversity, marketing and promotion, infrastructure and superstructure, in conjunction with assessments on economic effects of investments and tourism, human resource development, as well as socio-cultural and environmental impacts of tourism on the local communities.(Kaewsayar & Chamnongsri, Citation2012) Second, the model featured a short-term action plan as well (with a three-year circle) for priority actions to be undertaken in order to kick-start sustainable tourism development and preparation of several demonstration projects for the selected pilot areas in SawanKhalok-Si Satchanalai, as exemplified by the creations of tourist information maps in the district (Figure –).

Figure 10. A location map of UNESCO World Heritage Site and historic town of Sawankhalok-Si Satchanalai

Taken together, both Figures and illustrate that the selected locals for research (the pilot areas) dwelled on communities around Sawankhalok-Si Satchanalai Historical Park (Figure ). Apart from its historical significance, the historic town of Sawankhalok-Si satchanalai sheltered several kilns, but merely some of those sites had been excavated. Within the city wall, highlights of the archelogical included many ancient temples and shrines, such as Wat Chang Lom, Wat Chedi Chet Thaew, and Wat Nang Phaya (Figure ).

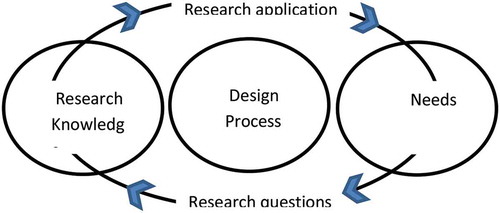

3.3. The propulsion mechanism process for creative tourism with digital enable: A three-pronged approach

Starting from digitization, which produced such a big amount of cultural data, there are different areas of impact: to use such digitized materials, the e-infrastructures and preservation standards are needed, mostly for allowing to manage and search digital cultural objects and metadata, in terms of creative re-use and Research and development.

There’s need to experiment the new digital technologies, with the necessary passion and competences, in order to demonstrate they are useful and more and more indispensable to tell and make enjoyable the history of our Cultural Heritage, besides creating new job and economic opportunities concludes.

Step 1: The first phase focused on generating well-defined mission statements for the project, which contained analyses on the current tourism scenario and preparations of necessary document for next tasks.

Step 2: The second phase revolved around fashioning a suitable Creative Tourism Strategy Model, which concentrated on the sectors of: tourist activities; transportation; accommodation; product development form culture capital; tourism area; appropriate marketing and promotion; corporate framework; statistics and research; constitution and coordination; and quality standards of tourism services. In each sector, a priority was given to formulations of integrated action plan to achieve quality tourism, as well as to define the roles and responsibilities of key stakeholders, set up timelines, allocate budgets, put guidelines into practice, and initiate successful implementations of the plans.

Step 3: The last phase included both implementations and evaluations of the Creative Tourism Strategy Model, resulting in model instruction guidelines for personnel from involving state agencies and local community leaders alike.

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1. Interpretations and conclusion

The above investigations collectively testified that not only: 1) a clearly defined, well-conceived, and effectively implemented Creative Tourism Strategy Model could assist the citizens and state authority in Sawankhalok district in dealing with creative tourism; 2) but its creational so involved all important stakeholders–encompassing local residents, community leaders, personnel from state agencies, travellers, hospitality business operators, advertisers, and staff members working at tourist attractions–via the principles of co-ordination, co-operation and collaboration (Figure –). Moreover, the proposed master plan to promote creative tourism was highly effective, because it facilitated community leaders and other stakeholders to apply their practical knowledge to work together, as illustrated by the productions of tourist information maps of Sawankhalok-Si Satchanalai (Figure –). Nevertheless, a quintessential acknowledgment must be brought to light that this research merely addressed a preliminary stage in creating a strategic model for communities around the World Heritage Site in Sawankhalok-Si Satchanalai to develop creative tourism, and had yet to thoroughly penetrate into its intrinsic substance. Although additional inquiries and clarifications on the model–via the criteria of motivations, authority, community-heritage engagement values–had still been much needed, a couple of concluding remarks could be formulated.

On the one hand, further studies must carefully investigate key factual information on the patterns of integrations in community-based tourism. Nonetheless, recommendations on the ways to improve management and execution of a master plan to cope with a development of creative tourism should be made accessible for stakeholders at the other two historical parks in Sukhothai and Kamphaeng Phet as well, because the three places had been listed by the UNESCO as a unified World Heritage entity (Figure –). So, all the interested parties at each locale could appropriate, adapt, and apply the lessons learned from Sawankhalok-Si Satchanalai to fashion their own plans, which would engender unique tourism experiences that were varied from the other sites.

On the other hand, whereas a need for undertaking a research that could effectively integrate an overall Creative Tourism Strategy Model for stakeholders in ASEAN countries–especially those located in the Greater Mekong Sub-region, i.e., Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, and Vietnam–had yet to be fulfilled (Figure ), it was imperative to recognize that differences in the social, economic, and political structures in each country were decisive conditions for carrying out such a comprehensive and ambitious project. As an ending note, since the realization of the East–West Economic Corridor (EWEC) passing through five Southeast Asian countries–which included Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam–in 2006, it appeared that the issue of Phra Ruang Route or Sukhothai Road had been making a noticeable progress in terms of a pathway to connect tourism network communities among the member states of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) (Figure ).

In any case, the said connectivity seemed to exercise substantial influences on the policies of the incumbent Chan-o-cha administration that sought to materialize socio-economic linkages among agriculture, food processing industry, handicrafts and other services–including tourism–with the neighbouring countries. (Punyasavatsut, Citation2011) Such nexuses could be a contributing factor in shaping sustainable market opportunities for local suppliers and entrepreneurs in Si Satchanalai, while at the same time stimulating productions of local goods and services, thus producing memorable and authentic–if not exquisite or even exotic–cultural experiences to the visitors. As a matter of fact, a similar kind of connectivity could also be witnessed from streamlined co-ordinative, co-operative, and collaborative efforts between the public and private sectors under the guiding policies from the state, as evident from many countries in the Asia-Pacific region such as South Korea,(Incheon Metropolitan City, Citation2012) China,(Shen, Citation2009) and Cambodia.(Cambodian Ministry of Planning, Citation2011; Cambodian Ministry of Tourism, Citation2016; Siem Reap Provincial Department of Planning, Citation2012)

Correspondingly, under a framework of a multi-lateral agreement among fourteen universities in Thailand, Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn Anthropology Centre, as well as Sukhothai and Kamphaeng Phet provincial administrations–in conjunction with international cooperation from several institutions of higher education in the neighbouring countries–a memorandum of understanding (MOU) to establish an academic network on UNESCO World Heritage sites along the EWEC was signed at King Mongkut’s Institute of Technology, Ladkrabang (KMITL), on 1 June 2018. Since then, the proposed investigations to create a master plan to develop a strategic model for creative tourism at Sawankhalok Historical Park had acquired a status of a pilot project that could: 1) lead to a foundation of the World Heritage Center ASEAN (a working body on the World Heritage sites in Southeast Asia) indicating an organization tasked with an accumulation and distribution of knowledge on cultural heritages in this part of the world; and 2) promote awareness and efforts on the conservation and restoration of resources in integrating cultural heritage, history, and tourism together in the future.(CitationUnited Nations World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO)) In sum, it could be argued that only would these activities further engage Sawankhalok in terms of a temporal discourse, but also rearticulate and reiterate its importance through interactive dialogues among the past, present, and future, which could lead to a plethora of opportunities for additional researches in times to come.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Surasak Kangkhao

Surasak Kangkhao, is an associate professor of architectural education at KMITL. He earned his B.S. in Architecture from the University of San Augustin, Philippines, and M.Arch. from the University of the Philippines, Diliman. His scholarly interests range from architecture and culture, urban and rural planning, creative economy, design pedagogy, to vernacular arts and crafts. At present, Surasak is directing a series of multi-disciplinary researches and strategic models for UNESCO World Heritage Site in Sukhothai, Si Satchanalai, and Kamphang Phet. Apart from his academic career, he is a licensed architect with extensive experience in professional practice and working on a massive number of projects in which his work received many international awards.

Notes

1. World Heritage Papers 31. World Community development through World Heritage. Published by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 7, place de Fontenoy,75,352 Paris 07 SP, France in collaboration with the European Commission, Universitat Politècnica de Valencia,Brandenburgische Technische Universität Cottbus and Deakin University (Melbourne). ISBN: 978–92-3-001024-9. 32–37

2. Marie-Theres Albert.(2012). Perspectives of World Heritage: towards future-oriented strategies with the five “Cs”. World Community development through World Heritage. Published by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 7, place de Fontenoy,75,352 Paris 07 SP, France in collaboration with the European Commission, Universitat Politècnica de Valencia,Brandenburgische Technische Universität Cottbus and Deakin University (Melbourne). ISBN: 978–92-3-001024-9. 32–37

3. See: Spencer Kagan, Cooperative Learning (San Clemente, CA: Resources for Teachers, 1994), page no 76.; Spencer Kagan, and Miguel Kagan, Multiple Intelligences: The Complete MI Book. (San Clemente, CA: Resources for Teachers, 1998), 65; Kagan, Kagan Cooperative Learning, 72.

References

- Cambodian Ministry of Planning. (2011). Status of CMDG achievement, goal 1: Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger. In Achieving the Cambodian Millennium Development Goals (CMDG): Update 2010 (pp. 7–18). United Nations Development Program. Retrieved May 3, 2018, From. http://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/MDG/english/MDG%20Country%20Reports/Cambodia/2010%20En.pdf

- Cambodian Ministry of Tourism. (2016). Cambodian tourism statistics report in 2016.

- Fine Arts Department (FAD). (2013, February 21). Si Satchanalai Historical Park. Collections of Knowledge on Historical Parks (in Thai). Retrieved January 12, 2018, From. http://www.finearts.go.th/archae/parameters/km/item/อทยานประวัติศาสตร์ศรีสัชนาลัย.html

- Howard Gardner. (1993). Multiple intelligences. Basic Books.

- Incheon Metropolitan City. (2012). Incheon metropolitan city urban basic development plan-revised.

- Kaewsayar, P., & Chamnongsri, N. (2012). Tourism initiative: A new way of touring Thailand. Suranaree Journal of Social Science, 6(1), 91–109.

- Lau, A. (2004). Thai ceramic art. Sun Tree Publishing.

- Mektrairat, N. (2014, May 16). Study Models and Examples of Collaborative Governance between Local Governments Private Sector, Civil Society, and Community. Retrieved December 21, 2018, from. http://v-reform.org/u-knowledges

- Nilsson, K., Nielsen, T. S., Aalbers, C., Bell, S., Boitier, B., Chery, J. P., … Zasada, I. (2014). Strategies for sustainable urban development and urban-rural linkages. The European Journal of Spatial Development.

- Office of the National Economic and Social Development Board (NESDB) and Thailand Creative and Design Center (TCDC). (2009). Preliminary report on creative economy. Boon Chin Press Limited.

- Prayut Chan-o-cha. (2014, September 12). Prime mister of Thailand, “policy statement of the council of ministers,” (Speech delivered to the National Legislative Assembly). House of Parliament.

- Punyasavatsut, A. (2011, February 1–5). Cultural capital in an endogenous growth model [Paper presented]. At the 49th Annual Conference of Kasetsart University (pp. 65).

- Rockwood, H. S. I. I. I. (1995a). Cooperative and collaborative learning. The National Teaching and Learning Forum, 4(6), 8–9.

- Rockwood, H. S. I. I. I. (1995b). Cooperative and collaborative learning. The National Teaching and Learning Forum, 5(1), 8–10.

- Shen, F. (2009). Tourism and the sustainable livelihoods approach: Application within the Chinese context [Ph.D. diss., Lincoln University), 66. Retrieved May 1, 2018, From. http://researcharchive.lincoln.ac.nz/handle/10182/1403

- Shibayama, M., Yanagisawa, M., & Howard Moore, E. (2013, September 18). The ancient East-West cultural corridor emerged from Myanmar to Thailand and Cambodia–Around 2,000 Kilometers in Mainland Southeast Asia. Retrieved May 5, 2018, From. http://www.kyoto-u.ac.jp/static/en/news_data/h/h1/news6/2013/130918_1.htm

- Siem Reap Provincial Department of Planning. (2012). Province profile year 2012 for local development management. Ministry of Planning.

- Thorbeck, D., & Troughton, J. (2016). Connecting urban and rural futures through rural design. In D. Thorbeck & J. Troughton (Eds.), Water science and technology library (pp. 45–55). Springer.

- United Nations Educational. (1991). Scientific, and cultural organization (UNESCO), “Historic Town of Sukhothai and associated Historic towns”. World Heritage List. Retrieved November 6, 2017, From. http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/574/

- United Nations World Tourism Organisation (UNWTO). Tourism development master plans and strategic development plans. Retrieved December 3, 2018, From. http://cooperation.unwto.org/technical-product/tourism-development-master-plans-and-strategic-development-plans

- Vasconcelos, E., Briot, J.-P., Irving, M., Barbosa, S., & Furtado, V. (2009). A User Interface to Support Dialogue and Negotiation in Participatory Simulations. In N. David & J. Simão Sichman (Eds..), Multi-Agent-Based Simulation IX, MABS 2008, Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Vol. 5269, pp. 127-140). Springer. Retrieved April 8, 2018, From. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-01991-3_10, 2009,54

- WHC. (2005a). Basic texts of the 1972 World Heritage convention. UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2002). Community participation. In Local health and sustainable development: Approaches and techniques (pp. 62). WHORegional Office for Europe. Retrieved December 3, 2019, From. http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/107341