Abstract

Keraton (the Javanese palace) cannot be separated from the existence of sacred spaces and profane spaces manifested in the spatial hierarchy values. Magersari, a settlement located within the palace’s land, still recognizes the existence of profane and sacred spaces, and the condition has implications for the management of spaces. This article focuses on the discovery of the sacred spaces in Magersari and on finding the people’s ways to interpret a sacred place. The method employed in this research was the qualitative-descriptive method with the case study approach where the phases were observing the sacred spaces in Magersari, finding patterns of the layout of the sacred space, and conducting in-depth interviews with key informants in Magersari to find the way the people interpret the sacred spaces. The results have shown that: (1) sacred spaces are not always in the midpoint of space nor the centre of space; (2) sacred spaces are spaces that were firstly built by kings called the original space; (3) the people of Magersari interpret sacred spaces through the oral storytelling told from generation to generation, and this storytelling is in the form of orders (dhawuh) that must be followed by the people as the sign of obedience their kings; (4) The interpretation of sacred spaces is related to the reproduction of power. The people’s obedience to the rules of space management inside the palace area has caused the maintenance of a sacred and profane hierarchy in the palace’s spatial order; hence, not harming the palace’s layout, architecture, and landscape.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Magersari is the settlement of Surakarta Sunanate Palace inhabited by the palace’s courtiers together with their descendants. This research aims to discover the way of Magersari people interpret sacred spaces. This research presents unique and authentic cases of sacred spaces because the discussion of sacred spaces focuses generally on spaces for spiritual activities, the space centeredness, cosmology, or nature. The sacred spaces in Magersari do not refer to those general cases and are not related to geographical positions; but the sacredness of these spaces are connected to how the people interpret the meaning of places from the storytelling passed down from generation to generation in the form of dhawuh (orders). The orders are the way to keep the places remains sacred, and this sacredness is related to the reproduction of kings’ power. This power, moreover, gives legitimation to the kings to keep all of the spaces intact.

1. Introduction

Today genius loci are the important knowledge to control the management of place so that the spirit of a place continues to exist. The meaning of place adheres to and is passed down from generation to generation. The people’s interpretation of the meaning of a place is based on the local culture that has become the custom observed daily as an authentic and unique experience. The theoretical construction of this research is theories that strengthen the originality of places and the connection between the spirit of places and the genius loci. Such connection creates places with various meanings by giving them character and power, so their existence can be felt (Norberg-Schulz, Citation2000). Thus, there is a relation among meanings, places (objects), and users (subjects), and there is also a relation between the places and the subjects that opines whomever masters or controls a place also controls the meaning of the place (Norberg-Schulz, Citation2000). According to Norberg–Schulz, losing the place means the loss of its meaning, so the stability of loci is needed to control the order of humans’ life.

The genius loci theory of Norberg–Schulz was applied to analyse sacred spaces in the Magersari settlement in Surakarta Sunanate Palace. Magersari settlement is located between two palace walls, namely the central walls and the outer walls of the Baluwarti Palace which surrounds the main palace. The researcher discovers the unique ways of the palace to maintain the genius loci and the spirit of places of its spaces, namely by controlling “meanings” of its spaces; hence, preventing the palace from “losing its spaces”. The buildings and the symbolic meanings in a settlement are the key elements of the genius loci theory. These key elements are the cultural expressions and interpretation of people towards their places, and these cultural expressions and interpretations are in the form of returning the meaning of a place and preserving the local culture (Norberg-Schulz, Citation2000)

The theoretical construction related to the holiness of a place is based on the humans’ authentic experiences in the places they stay and do all their activities, so the sacred meaning of a place is interpreted as human understanding built from the awareness structure in which the comprehension of sacredness is not universal (Eliade, Citation1987). Eliade also describes that profane daily experiences when viewed and interpreted in certain ways will become authentic and sacred experiences. Eliade, furthermore, explains that the uniqueness appears because of the humans’ experiences, not because of the geographical location; and it is the unique experiences of humans in interpreting sacred spaces that are discovered in this research.

This research used two main theoretical constructions, namely the Norberg–Schulz’s genius loci theory (Norberg-Schulz, Citation2000) and the Eliade’s sacred place theory (Eliade, Citation1987). The Magersari people have a unique way to interpret sacred spaces based on their unique experiences, and it is the way which was discovered in this research.

In the spatial layout pattern hierarchy of Javanese palaces, there is a sacred and profane spatial structure (Behrend, Citation1982; Geldern, Citation1982; Tjahjono, Citation1989). This structure is supported by the concept that the main characteristic of Javanese space is its unity, sanctified by the existence of surrounding walls forming the border between the sacred area and the profane area. This disposition model is known as the microcosm-hierarchical principle (Santoso, Citation2008). These surrounding walls are believed to be the centre that perfectly invites both tangible and intangible cosmic forces (Wiryomartono, Citation1995). Between the palace’s outer walls and the palace’s inner walls is Magersari, a settlement inhabited by the royal families and courtiers, together with their descendants, who still have a close relationship with the palace (Adrisijanti, Citation2000; Soeratman, Citation2000). The Magersari settlement still survives and preserves its traditional ways of residing, and its special space management, as the practices of reproducing power to gain legitimacy from its residents (Marlina, Citation2018).

In countries throughout the world, the concepts of sacred and profane spaces differ in types of spaces. There are various theories about the concept of “sacred space” that will lead to the novel findings presented in this article. According to Norberg-Schulz (Citation2000) dan Eliade (Citation1987), different places certainly have different concepts of sacred spaces and place meaning, and there are many theories of sacred spaces that will go the novelty of this research. One of those theories has been proposed by Santoso (Citation2008) which includes temples built in East Java (the Buddha-Siva periods), together with mosques built in the Islamic-Javanese periods, as being sacred buildings. The sacred parts as the core and centre of the microcosm are seen in the meeting of two or more elements having sacred meaning. For example, the north-south main axis as the main orientation is the sacred place, coupled with the existence of the belief in surrounding fences, which function as the media to sanctify a place. The author does not fully support Santoso (Citation2008) because the Magersari settlement has no temples considered as sacred places, and the mosque in this area is not the object of the study of sacred space in a traditional courtier settlement. However, the author agrees that a settlement in the surrounding walls is a sacred place, as seen in the Magersari settlement. Santoso (Citation2008) offers a different concept from the statements by Eliade (Citation1969, Citation1987), which explain that not only are temples recognized as sacred spaces and the central focal points of the sacred world but also are all places which became witnesses that sacred spaces were created naturally based on cosmogony. Examples of these additional places are ancient cities, temples, and palaces. Such understanding is considered as the continuation of the replicas of ancient images that recognize symbols such as i) the cosmic mountain, ii) the mountain of the world, iii) the tree of the world, and iv) the central pillar which support the cosmos. This understanding is then spread throughout the world as a natural truth considered having sacred values. The author agrees with the findings of Eliade (Citation1969) which reveal that not only are temples recognized as sacred and central places, but there are also sacred spaces in palaces and ancient cities. This finding can be used as a starting point in this research so that it can lead to the discovery of sacred spaces in Magersari at the Sunanate palace, which is situated in the ancient city of Surakarta. The researchers agree with the Eliade’s opinion (Eliade, Citation1969) stating that the sacred spaces can be located anywhere depending on the humans’ experiences related to sacredness as the truth, and Eliade’s perspective can be the first step of this research which eventually leads to the discovery of sacred spaces in Magersari and the way its people view the sacred spaces which are located inside the palace in the old city Surakarta.

A different research finding is expressed by Bar (Citation2018) stating that mountains, particularly in their higher places, are recognized as sacred places. Bar furthermore suggests that the kings’ tombs located on a mountain, and Islamic sacred places located around settlements, are included in the category of sacred spaces. The finding, describing that a king’s tomb located on a mountain is a sacred place, conflicts with this research approach because the location of the Magersari is not to be found in a settlement around a graveyard on a local mountain, but it is located in the centre of an ancient city. The other finding similar to Bar’s is also presented by Bardaji et al. (Citation2017) describing that sacred spaces are located in cemeteries, the researchers concluded that ancient cemeteries and their landscapes are sacred spaces, but this finding is more specific because it directly refers to the term: “ancient cemetery”. This is a different conclusion from previous findings which have not specifically mentioned the types of the grave. The author disagrees with Bar (Citation2018) and Bardaji et al. (Citation2017) because sacred space is not always in an ancient tomb located on a mountain. Such a space can be in a settlement like the one in Magersari settlement.

Slightly broader opinions then emerged, including other locations assumed to be sacred sites such as Hindu, Christian, and Muslim cemeteries and temples. This assumption came from the opinions stating sacred spaces had dense trees which provided an important buffer against the pressure of the urban environment. Such a buffer also functioned as a wildlife shelter and a sanctuary of urban biodiversity as well as for native species diversity (Jaganmohan et al., Citation2018). The supporting evidence reaffirming that a tomb on a mountain is a sacred place has also been expressed by several researchers. Indrawati et al. (Citation2016) conducted research based on the premise that graveyards on the top of mountains represented a pattern of historic settlements, and the pattern is a combined pattern between the Catur Gatra Tunggal concept the concentric pattern. This pattern, furthermore, indicates a space is a sacred place for pilgrimage; this finding is similar to the previous research finding conducted by Puspitasari et al. (Citation2012) defining that those graveyards as “maqom suci” (holy graves) and as sacred spaces where pilgrimages coming to historic villages. While Jaganmohan et al. define that sacred spaces are the holy sites such as cemeteries and temples and Indrawati et al. opine that sacred spaces are the cemeteries located in the mountains, Puspitasari et al speaks about the sacred spaces are the tombs located within historic villages. The view of Puspitasari et al has similarities to the author’s view related to the location of the sacred spaces because Magersari is a settlement located in a historic area. Hence, a clear need for another relevant approach.

Some findings are in line with the study conducted by Jaganmohan et al. (Citation2018), in which Rutte (Citation2011) found that natural sites are the most sacred spaces, but the difference with previous research is that sacred natural sites are generated from complex interactions between values and human behaviour, involving socio-cultural, institutional and ecological settings. It is worth noting that none of these findings mention that the holy sites are graveyards or that the graveyards could be holy sites. Likewise, a similar study conducted by Brandt et al. (Citation2015) explains that the natural forest is a holy and sacred area. However, this study was disadvantaged in that no research was conducted that related to socio-cultural values and there was no reference or suggestion that a tomb could be a holy place. Therefore, the study by Brandt et al. is limited to the physical nature of forests. On the other hand, different findings have been revealed by Owley (Citation2015) who stated that sacred sites are holy sites which have a cultural heritage background and must be protected by conservation. Unfortunately, this arboreal study did not explain whether the cultural heritage dimension is included in sacred sites, or not, so it is still general. The author of this paper then rejects the approach stating that natural sites and natural forests are sacred places because the Magersari settlement is not located in natural forests, but she agrees that sacred sites can be located at cultural heritage locations that are protected by conservation laws.

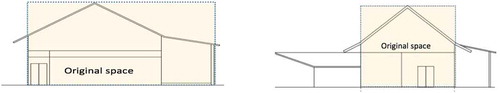

The finding contrary to the previous research was revealed by Terzidou et al. (Citation2018) who stated that sacred places are all sites that have, throughout history, been used for religious activities. The same opinion was expressed by Sardjono and Harani (Citation2017) who explained that sacred spaces, called “the holy room”, are places for worship and prayers. However, they suggested that sacred spaces are not solely for official or formal religions and their associated activities, but they also function as places to carry out the traditional belief ceremonies. Such situations thus form a sacred space that is centralized, relatively closed, and vertically-transcendentally oriented. These phenomena are shown in architecture where people have built a sacred space in which its roof height, its roof angle, or its floor height is greater and loftier than the surrounding profane spaces. The theory defining that the places of worship are sacred spaces is deeply understood in two main meanings: a) a space not connected to worldly things is called sacred, and it is interpreted as the main space for prayer that requires purity or cleanliness and b) a tomb as a sacred place and destination point for pilgrimage. It should be pointed out that even in sacred spaces there is a connected profane or worldly space that can be used for women’s activities (as in an Islamic mosque). On the other hand, the factors that influence the sacredness of a space are physical barriers and the sanctity of the worship room. This statement means sacredness is a legitimate requirement for worship, hence the “sacred primary need” (Ramadhana & Dharoko, Citation2018). The authors have different opinions about the sacred space stating that such a space is not only formed by activities associated with worship but it can be also be formed by a tradition of ancient, long-held belief in society. This perspective offers a more promising approach for research in Magersari.

However, throughout history places visited for contemporary pilgrimage have been recognized as traditional-sacred spaces. Furthermore, these places were at first only special places for religious practices and the purpose of the pilgrimage was the one recognized for these sacred spaces (Kim et al., Citation2016). The theory expounding that spaces for religious activities were recognized as sacred spaces was interpreted more broadly by the finding stating that religious places for daily prayer and devotional visits were also sacred spaces (Berriane, Citation2015). Thus, it can be concluded that sacred space is a space that symbolically has a greater meaning than other spaces (Leith & Wilson, Citation2014). This finding is consistent with the previous research explaining the “spirit of the place”, a quality of a place that presents spiritual power and encourages sanctification, which makes such a location a sacred place. These places, the churches, shrines, crematoria, possess a meaning that was built by processes associated with the human spiritual journey (Day, Citation2002). The author of this research agrees with Leith and Wilson (Citation2014) who state that the sacred spaces offer and involve more meaning than other spaces. Such a statement is in line with the case of the sacred spaces in Magersari, which certainly have more meaning than the other surrounding spaces. The approach from Leith and Wilson can be the starting point for answering the purpose of this research, but the author disagrees with the theory that only places for prayer and worship, churches, and crematoriums are considered as sacred spaces. The sacred space in Magersari is located in a settlement, not in a special place for prayer and worship; hence, an alternative approach to the issue of sacredness is needed.

Furthermore, other studies having different perspectives state that the sacredness of space is determined by ways in behaving and ways of honouring such spaces. This kind of acts includes restrictions on permission to enter a space, so transcendental quality action does exist in an act (Sicherman, Citation2011). This current Magersari based study is supported by a theory stating that the selection of a space occupied by a group of people imbued with intrinsic orientation and fundamentalism from the same religion will create a connection with the sacred space because these people all have the same view (Meagher, Citation2018). In-depth research on cultural beliefs and practices that connect people to a place focuses on the concept of the “spirit of the place”. This concept is what gives a special “sense” or spirit of mystery to a person or group. The spirit of a place is strengthened from the habits of a recurring activity that forms and strengthens that sense and community attachment (Cross, Citation2001). Studies conducted by Sicherman (Citation2011), Meagher (Citation2018), and Cross (Citation2001) are interconnected with the same point of view on sacred space. Therefore, behaviour towards space also has similarities, and repetitive actions will become habits so that attachments to community and place arise. The author agrees with the perspective presented by Sicherman (Citation2011), Meagher (Citation2018), and Cross (Citation2001) in viewing cases in Magersari, where the same tradition drives recurring habits that are finally recognized by society as a truth. The previous researchers, however, have not explained that there are unique layouts of sacred spaces and unique ways of people in interpreting sacred spaces, so it needs approaches and theories to analyse them. Meanwhile, the researcher believes that there is dominant power that shapes the perception of spaces sacredness where its truth is accepted by the people.

Contradictory research reveals that sacred places are often “strange” religious sites associated with important myths, and “strange” spatial spirituality (Ashgate & Surrey, Citation2013). In connection with myths, Tuan (Citation2001) reveals that mythical spaces are seen as a component within the world’s view or cosmology. In this view, the centre is public in which there is an interaction among humans while the periphery is sacred. Nature (forest), moreover, is considered a religious space called the sacred space located at the edge, and apart from the public space. In Magersari on the axis of the middle road to the palace, there are also sacred spaces. The difference with previous studies is that in general researchers state the sacred space is in the middle or in the centre of a place. However, Tuan (Citation2001) states that the sacred space is on “the edge” not in the middle/centre. From this perspective, the common ground of nature/forest is considered a sacred space. The author agrees that myths are important in the formation of sacred spaces but disagrees about religious spaces having myths that are considered as a sacred space. This current research is not related to religious places, hence the need for a different approach. Related to the findings of Tuan (Citation2001), the author partly agrees with his theory stating that the periphery is sacred, but she does not fully agree because in this study sacred space can occur either on the periphery or in the middle of a location; in this case Magersari. Thus, several different approaches are needed in this study.

Purwani (Citation2017) rejects Tuan’s research results; she views the “middle part” to be the most sanctified and sacred, which means the less “centred” the area the more profane it is. This description is manifested in the hierarchical relationship between the centre and the periphery, based on the daily life Javanese Keraton where the more centred the space, the more sacred the space; hence, the more important the event held within. These sacred spaces, located in the middle, are like the midpoint surrounded by 4-point or 8-point compass rose. This area is the king’s area (Ossenbruggen, Citation1975). The author does not fully agree with Purwani (Citation2017) and Ossenbruggen (Citation1975), who stated that the centre is the most sacred, because in Magersari the sacred space is located at the back, front and beside a location, instead of at its centre. Santoso (Citation2008) offers a different view related to the concept of sacred space in which he sees that sacred space is closely related to its function. In this case, the Surakarta Sunanate palace has two functions: a) the sacred function as a place of residence for the sultan and b) the profane having position as “parentah jero” or location of the inner circle administration that connects the sultan to “parentah jaba” or the outside administration. The researcher also rather disagrees with the Santoso’s finding (Santoso, Citation2008) presuming that sacredness of spaces is related to its function as the place for kings while in reality, Magersari is not the kings’ dwellings though it is connected to the sacred spaces and the king’s spaces hence, the need of different approaches.

Long before the researchers from different countries found theories of sacred spaces, the Maya believed that the centre of the universe was on tiered pyramids, the Navajo believed that the centre of their universe was on their sacred mountain, and the Incas believed the centre of the universe was the sun temple, and the Teotihuacan believed that the centre of the universe is their large pyramid that has a temple on its top stairs which faces towards their sacred mountain in the west in perfect harmony (Carlson, Citation1990). According to Carlson (Citation1990), all of those tribes had geocentric belief, the symbolism of nature and deity, and 4 or 5 compass roses where the midpoint is the centre. The author agrees that the formation of space is related to the centre, but she rejects the opinion stating that the sacred space is always located in the middle and therefore always becomes the centre point of focus.

The author will refer to the statements of Eliade (Citation1969, Citation1987)) that suggested the “centre” is not always synonymous with “central space”. Tuan (Citation2001) stated that sacred space can be at the periphery of a location or area, and Sicherman (Citation2011) explained that the sacredness of a space is determined by prohibitions. Besides, the approaches from Sicherman (Citation2011), Meagher (Citation2018), and Cross (Citation2001) were employed to investigate the case of sacred spaces in Magersari because it is necessary needs to involve traditions that have created recurring habits and are recognized by the community.

The theoretical construction is built by the Norberg-Schulz (Citation2000) and Eliade (Citation1987). Both theories have not mentioned that sacred spaces and their interpretation can be created from oral storytelling which is passed down from generation to generation and demand obedience from the people living in Magersari, and such oral storytelling functions as “dhawuh” (orders) which are unwritten and has become a tradition. From these unique phenomena, moreover, a theory of sacred spaces should be built with the case study to enrich the existing related theories.

From the previous research reviews, most of them discuss the meanings of sacred space related to places for spiritual activities, natural places like mountains or woods, the north-south main axis, the central points and Axis Mundi which are interpreted as the centre of sacredness; those places are usually connected to geographical positions. However, the case of Magersari settlement has novelty on the meanings of sacred spaces that do not refer to geographical positions, spiritual places, or people’s free perception; the meanings actually lie in the oral storytelling functioning as orders that every people must obey them as the tradition. This condition eventually stimulates the same interpretation and perception in the creation of sacred space meanings. The orders or dhawuh from the king of Surakarta Sunanate Palace are told repeatedly so that they shape the same interpretation to sacred spaces. Therefore, it needs more theories to support the main theories, namely the power theory (Weber, Citation1978), the myth theory (Larson, Citation1990), the traditional authority theory (Coleman, Citation1997), and the domination of social system theory Giddens (Citation2010) to analyse this case.

2. Methods

This research employed the descriptive-qualitative method with multiple cases (Yin, Citation1989). The case study was used to enrich and modify existing theories in analysing unique cases occurring recently (Yin, Citation1989). The first step comprised of: (1) making proposition based on the literary reviews; (2) preparing field survey consisting of case selection, guidance in searching and collecting data; (3) analyses for each case and cross-case analyses. The second step, moreover, was building the theme.

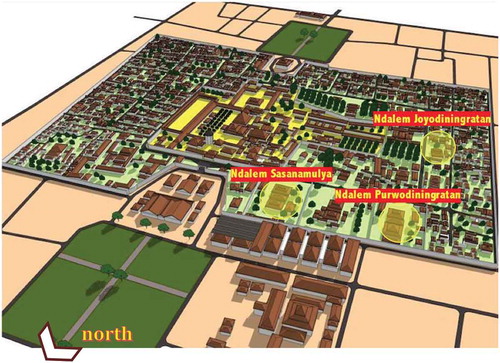

In the case with unique and authentic characteristics such as the case in Magersari, three clusters of dwellings were selected according to the number of places or the number of original buildings that are still considered as sacred places by people in Surakarta Sunanate Palace. This selection was carried out using the purposive sampling method (Creswell, Citation1998). The selected clusters in this research were: (1) Ndalem Sasanamulya, the first case, a complex consisting of 35 houses; (2) Ndalem Joyodiningratan, the second case, a complex consisting of 21 houses; (3) Ndalem Purwodiningratan, the third case, a complex consisting of 18 houses. Therefore, the total number of selected houses was 74 houses. This research, conducted from 2018 to 2019, has found the sacred spaces at Magersari settlement in Surakarta Sunanate Palace and has described how the people give interpret places as the sacred ones in Magersari settlement.

The process of collecting data, both qualitative data (collected inductively) and the data collected from the proposition (deductively), in this research referred to Creswell (Citation1998), and this process was done concurrently, hence a more effective process. The propositions were formed at the beginning of the research and functioned as the guidance in the field; and these propositions were: (1) the positions of sacred spaces which are connected to the people tradition; (2) the interpretation of sacred spaces related to the culture of the local people; (3) the interpretation of sacred spaces related to the power.

Collecting empirical data were done by visiting all selected buildings, 74 buildings, and photographing the authentic elements, original buildings, and original spaces that are interpreted by the people of Magersari as the sacred spaces. Field survey and photographing were assisted by the key informants and the elders to make observation and interview were easily conducted. The people of Magersari were selected as criteria in selecting interviewees and key informants were based on the fact that these people were the persons who directly involved in all activities and interpretations of places or spaces considered to be sacred. The key informants, particularly, were chosen among the elders from both the nobles and the courtiers. All of these interviewees and key informants were selected with the purposive sampling method.

The field surveys, photographing, and in-depth interviews were conducted at the same time. The interviews comprised of 35 heads of the family from Ndalem Sasanamulya, 21 heads of the family from Ndalem Joyodiningratan, 18 heads of the family from Ndalem Purwodiningratan while the key informants comprised of 3 elders who directly involves in all activities of keeping sacred places’ originality and interpreting the sacredness of a place. Thus, the in-depth interviews were carried out with 77 people.

The next step was collecting all supporting data from Magersari people, documents from the village office, heritage documents, and the previous research reports. The data were in the form of the map of Magersari and Griya Pasiten Keraton documents to know the location of the original buildings and the monograph on the number of Magersari people. The primary data (collected from observation and interviews) and the secondary data (maps and documents) were processed with the triangulation technique in the final step for validation (Benz, Citation1998). Triangulation was done by: (1) comparing the data from observation with the data from interviews; (2) comparing answers from interviewees or informants; (3) comparing answers from documents. The data collection was based on research questions and propositions, namely: (1) how were sacred spaces created? (2) how were the patterns of the sacred spaces created? (3) how do people interpret sacred spaces? (4) what causes sacred spaces to occur?

Each case was analysed carefully using the guidance of propositions. The results of the first case were then used to improve the guidance for the second case, and the same activity was done for the third case. The next analyses, the cross-case analyses, were carried out by comparing the results of the first case and the second case until patterns were found. These patterns were then compared with the third case, so the similarity and the difference of the patterns were known; this is known as the technique of matching patterns. The results of the cross-case analysis of sacred spaces patterns were compiled to the findings related to the characteristics of sacred spaces in Magersari settlement. The findings of each case and the findings from the cross-case analysis involved the search for the causes of the sacred spaces occurrence. The last step was the interpretation of findings to discover the meanings of sacredness phenomena based on the results of in-depth analyses and findings from the theme building.

3. Discussion

3.1. The layout and position of the sacred spaces are determined by the royal word (dhawuh)

Located at the Surakarta Sunanate Palace, Magersari surrounds the core area of the palace called Kedhaton. The locus of this research is at the cepuri Ndalem Puwodiningratan in the north of Kedhaton, cepuri Ndalem Sasanamulya in north of the Kedhaton, and cepuri Ndalem Joyodiningratan in the west of the Kedhaton (Figure ). The Magersari settlement surrounds the noblemen’s main house (Ndalem) on the left, right and back. This kind of layout, surrounding the main house (Ndalem) as the centre, has been explained by previous researchers such as Geldern (Citation1982), Behrend (Citation1982), Tjahjono (Citation1989), Carlson (Citation1990), Adrisijanti (Citation2000), Soeratman (Citation2000), and Priatmodjo (Citation2004), and (Widayati, Citation2015). The pattern of a Magersari residence inside the palace is always centre-oriented and has hierarchy according to the level of the social strata shown in the level of the space’s sacredness. Hence, the more centred the more sacred. However, related to the layout of the sacred space, the case of Magersari is different from other similar cases in which the sacred spaces always follow a centralized hierarchy. This difference is what the author will describe to offer another alternative perspective in thinking about the sacredness of a place.

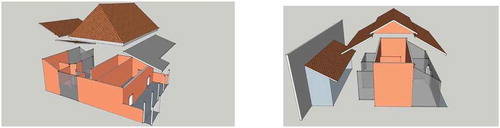

The Magersari residence has a different layout structure in comparison to the previous findings cited above that suggest sacred spaces are always “in the centre”. In this case, the sacred space is not always located in the centre, such as the Magersari residence in cepuri Ndalem Purwodiningratan. There are sacred spaces located in the front of and the middle of the building (Figure ), and it can also be in the centre of the building (Figures ) and ()). From Figure ), it can be seen that the position of the sacred space can also be located throughout the whole building. The aforementioned locations of the sacred spaces are certainly different from previous findings as expressed by Ossenbruggen (Citation1975), Geldern (Citation1982), Behrend (Citation1982), Tjahjono (Citation1989), Carlson (Citation1990), Adrisijanti (Citation2000), Soeratman (Citation2000), Priatmodjo (Citation2004), Widayati (Citation2015), and Purwani (Citation2017). The word “centre” here (as a place) means the Surakarta Sunanate palace, which has become the locus of the research. Apart from the central concept mentioned earlier, the author will show the location of the sacred space of Magersari in Ndalem Sasanamulya. The residence is an elongated row of houses attached to the cepuri wall. This place is believed by its residents to be a sacred space, and no one dares to change or dismantle the original buildings (Figure ,)). The next case is Ndalem Joyodiningratan in Figure ). The original buildings in this area are located behind the new building. This condition is different from the condition in Figure ), where the original buildings are in the centre of the new buildings and Figure ) where the original buildings are in the middle and on the side. From these facts, it can be concluded that sacred space can be situated in any or all parts of the buildings.

Figure 1. Magersari Surakarta Sunanate Palace, locus Cepuri Ndalem Purwodiningratan, Cepuri Ndalem Sasanamulya, and cepuri Ndalem Joyodiningratan

That the locations of the sacred spaces are not always in the centre but in several places is a strong foundation for conducting in-depth interviews with each key informant in each area of the Magersari residences. The research results suggest the existence of sacred spaces in Magersari is believed to be due to an order from the kings to maintain the originality of the spaces and to protect them from damage. The kings also always bring myths when it is related to these spaces. The king’s statement affirming that anyone who dismantles or damages the original buildings will meet bad luck is one of the examples. The king’s word, prohibitions, and myths related to spaces or buildings are believed to be transcendent commands and are believed to confirm the existence of the sacred spaces. The results of the interviews showed that the kings’ orders to maintain places were wrapped in storytelling that is continuously passed down from generation to generation and is believed by the people. The sacredness of places was strengthened by the myths telling that whoever dismantles or destroys the buildings will experience bad things. Not only people living inside the palace who are directed to obey such orders but all people outside who are in those places must also obey the orders. On the other hand, the author believes that the kings’ commands are the practice of power reproduction since the palace no longer has authority like its golden era in the past. The palace as the cultural symbol, needing legitimacy from the people, has issued “dhawuh” (orders) about managing sacred places in Magersari settlement.

Apart from the Magersari layout concept above, there is a spatial structure in Magersari which shows that the sacred space is fused within each Magersari residential space which functions as a residence. This novel situation challenges previous findings which believe that the sacred spaces are only in the form of temples and mosques Santoso (Citation2008), north-south axis and area inside the circumference wall Santoso (Citation2008), tombs (Bar, Citation2018; Bardaji et al., Citation2017), mountain peaks, pilgrimage sites Indrawati et al. (Citation2016), cities ancient-temple-palaces Eliade (Citation1969), natural sites Rutte (Citation2011), holy sites Owley (Citation2015), religious place or places for worship or prayer places (Berriane, Citation2015; Terzidou et al., Citation2018), a place to carry out a faith-related tradition (Sardjono & Harani, Citation2017), and crematoria Day (Citation2002). The findings regarding the sacred spaces in Magersari also rejects the opinion Sicherman (Citation2011) that the sacred is more about limiting entry permits because the sacred space found in Magersari turns out to be used for shelter and daily household activities and there are no restrictions on entering it. However, on the other hand, the author agrees that the sacredness of a location, site, or space is related to limiting an action (Sicherman, Citation2011). The restrictions the author means are restrictions on not changing the original space or the original building elements, and not changing the structure of the original building construction so that the original building is believed to be a sacred space.

Figure 2. (a) The orange colour in the building shows the location of sacred spaces in the front of, middle of and back of Ndalem Purwodiningratan. (b) Orange colour indicates the location of sacred spaces in the middle of the building at Ndalem Purwodiningratan.

Figure 3. (a) The sacred spaces cover the entire building. (b) The sacred spaces are in the middle/centre of the building.

Figure 4. (a) Buildings with long and orange lines are the original buildings believed to be sacred spaces. (b) The original building (orange) located behind and attached to the fence wall as the sacred space.

Figure 5. (a) The original (yellow) building located behind the building is considered as the sacred space. (b) The original blue building is believed to be a sacred space located in the middle of the building. (c) The original green building located in the middle and side of the building is considered as the sacred space.

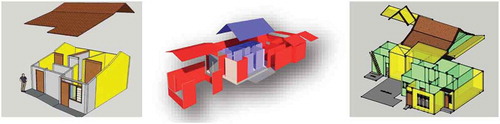

Sacred cases can be seen in the Ndalem Purwodiningratan Magersari dwelling. There is a warehouse space that has walls, windows, doors, and original construction which is believed to be a sacred space currently being used for residential purposes (Figure )). The next case is the pavilion building used for noble guests in ancient times. This pavilion still has the original building form and is considered a sacred space by the Magersari people (Figure )). Another sacred space can be found in the building that functioned as a nobles’ dining room. It still has the structure, construction, and original building elements so it is believed to have sacred value because it was originally used for aristocratic daily activities. The building is currently used as a dwelling for nobles’ sons (Figure )). Other sacred buildings are dressing rooms, family rooms, and houses of nobles’ wives; all locations that are believed to have strong historical value through association with the lives of nobles, so that authenticity is preserved and the locations are considered sacred spaces (Figure –)).

Figure 6. (a) The original door, window and wall elements in the warehouse are believed to be part of the sacred space. (b) The pavilion as the living room for the nobles, believed to be the sacred space, is located in the backyard. (c) Lojen as the king’s dining room is believed to be the sacred place.

Figure 7. (a) The dressing room has elements of the original building, structure and construction of the original building are believed to be the sacred place. (b) The family room with the original structure and construction is believed to be the sacred place. (c) The row houses of the king’s wife’s house with the original shape, structure and construction are believed to be the sacred place.

In Figure –c) sacred space can also be found in the Ndalem Sasanamulya. Within the sacred space, there are classic consoles, doors and windows made from teak wood inside the ancient buildings built by the kings; all still well preserved and being used by the descendants of the palace’s courtiers. Another building believed to be a sacred space is the kitchen with its original roof and walls (Figure ,b)). There is also an old pantry (prantunan) in which there is an oven made from thick iron. This place is believed by the community to be a sacred space; it remains in shape and currently functions as a house (Figure )). Likewise, stables are considered sacred because even though these buildings now function as houses they used to be the kings’ stables, hence the preservation of their form and construction (Figure )).

The next example is the houses of the courtiers. These elongated wooden row houses with wooden furniture like consoles, windows, doors, and walls are considered sacred spaces (Figure )). The belief of the Magersari people in these sacred spaces can be seen from their routine offerings. The practice of offerings is the kingdom’s principal philosophy, expressed as a royal message in the form of rites (Soemardjan, Citation2009).

Figure 8. (a) The room with original walls and console, doors and windows made from original teak wood are believed to be the sacred place. (b) The facade with original walls and consul, doors and windows made from teak wood are believed to be the sacred place. (c) Teak wood consoles within the space are believed to be part of the sacred space.

Figure 9. (a) The kitchen with its original structure and construction believed to be the sacred space. (b) The kitchen wall believed to be a sacred space. (c) The pantry or prantunan has the old oven with its original structure and construction believed to be a sacred space.

To further explore the issue of sacred spaces, the author will show the existence of the sacred spaces in the Ndalem Joyodiningratan. In this place, she found the space around pillars used to support the stable’s roof has become a residence. However, the residents believe that this space is sacred, so the original appearance of the space is maintained (Figure )). Next, there are stables, covered protection for carriages, and a garage for noblemen’s cars that have all been converted into dwellings based on orders from the kings or their nobles. These orders are considered as sacred orders so that the management of these buildings is also limited by the prohibition of changing or dismantling (Figure )). Horses, trains, and cars, as the kings’ means of transportation, are considered to have transcendent powers that impart to the spaces surrounding them, hence becoming sacred spaces themselves. The next physical entity considered as a sacred space is the elongated building that used to be the transit place for nobles, and which is one of the king’s assets (Figure )). Moreover, the kitchen building that used to make royal dishes is currently believed to have mystical powers and is therefore considered to be a sacred place (Figure ,)). From the description above, it can be concluded that the old buildings, built by the kings, are believed by Magersari people as the sacred spaces so that the originality of these buildings are still well maintained. The belief of Magersari people in these sacred spaces is strengthened by the king’s orders to occupy these spaces as the dwellings and by prohibitions on destroying or changing the elements of spaces in the form of restricted space management. These orders, besides, are called “dhawuh” and they must be obeyed by all people connected to Magersari both the ones who live and the ones who only stay temporarily or pass the area.

Figure 10. (a) The stable believed to be a sacred space with its original structure and construction. (b) The row of houses with original their original shapes and construction considered as the sacred space.

3.2. The characteristic patterns of sacred spaces

Characteristic similarity findings from the three cases:

(1) Sacred spaces are all spaces that were used by kings, nobles, and kings’ supporters. These spaces are: theking’s/nobles’ pavilions, the king’s families rooms, the kings’ transit room, the king’s make up room,the king’s/nobles garages, the king’s warehouse, the pillars of the king’s/nobles stables, the elementsof original doors, original windows, original consoles and walls, and original construction.

(2) All sacred buildings function as the dwellings of the palace courtiers

(3) Spaces, buildings, or places built by kings are categorized as sacred spaces.

(4) Spaces and buildings used for kings’ activity are categorized as sacred spaces

(5) Sacred spaces were created because of kings’ orders

(6) The obedience to the kings’ or nobles’ orders or (“dhawuh”) applies to all people in Magersari.

(7) The way the people interpret orders (“dhawuh”)

Characteristic difference findings in the three cases:

(1). The layout pattern of sacred spaces is that sacred spaces are located in all parts of the building

(2) Sacred places are not always in the central position,

Characteristic findings on orders (“dhawuh”):

Orders (“dhawuh”) must be obeyed by the Magersari people and all people who are in the Magersari area (including non-occupants like persons who just walks across the area), and such obedience is absolute.

Characteristic findings on storytelling:

Orders (“dhawuh”) are repeatedly told and have been passed down from generation to generation in the form of oral language, the truth is believed by the Magersari people. Oral storytelling among Javanese people are called “bahasa tutur”

The characteristic of “restriction”:

Orders (“dhawuh”) also restrict the activities of Magersari people in managing places, so it prevents them to change or even tear down the original buildings.

The characteristics of myths-rituals

The findings showed that all Magersari people obeyed the orders because they believed that all places and buildings belong to the palace have transcendental force based on the kings’ orders. The powers of the kings’ orders that are believed by the people have become the myths stating everyone disobeying the orders will meet bad luck or even death. Rituals are the activities that strengthen the myths, and the rituals can be seen from the offerings made by Magersari people in sacred places.

3.3. The royal words, orders (dhawuh), and the prohibition as the practices of asserting power

In the perspective of Magersari people, orders and prohibition issued by kings or nobles have become common things for them since such practices have been done repeatedly for generations, hence creating a communal bond Cross (Citation2001) in which the people have the same point of view Meagher (Citation2018) and also believe in the transcendental quality of an act done by kings or nobles (Sicherman, Citation2011). The recognition of the king’s authority was seen in the moral teachings stating that the kings are the owner of everything including properties and also humans, so their people had to obey what they asked. The kings, furthermore, had the right to take everything easily, including the life of their people, if they wanted it. Therefore, the people’s obedience to the kings was similar to their obedience to God, so to the kings what they could answer was only “ndherek karsa dalem” (we follow the king’s will) (Moedjanto, Citation1987). The king’s authority here means the control of the king’s properties and infrastructure Sell (Citation2017), and the power of a king is shown by all of his heirlooms and treasure (Moedjanto, Citation1987).

Social status, positions, organization, weapons, population are considered of the sources of power (Budiardjo et al., Citation1991). Thus, the buildings that kings, as the source of power, asked the people not to change its originality are considered sacred. The kings’ central position in both social and cultural life causes all the management of spaces is based on the kings’ orders as the central and autocratic authority, and such condition made the kings as the only source of power (Soemardjan, Citation2009).

Orders (dhawuh) are believed as the traditional authority exerted by the palace repeatedly for generations to maintain the existing system through tradition Marlina (Citation2018), and this definition is following what has been described by Budiardjo et al. (Citation1991) that Javanese people traditionally consider their history like a circle where the events always repeat. This traditional authority depends on the myths Coleman (Citation1997), and the myths in Javanese palace (keraton) describe that the king is the representation of God who protects the people, hence creating a master-servant relationship (Larson, Citation1990). The obedience is thought as the aspect that keeps the existence of the authority Weber (Citation1978), and the obedience to the king, thus, is absolute (Moertono, Citation1985). In addition, according to Weber (Citation1978), Larson (Citation1990), and Giddens (Citation2010), the authority can be in the form of “unwritten orders” as the exertion of power done by the people from the higher social class.

Ordering and forbidding are the social practices to enforce what has been set by the rulers, and obedience to the rulers and the adaptation of the physical environment are highly valued in the cultural perspective (Soemardjan, Citation2009). Magersari people live in a strong Javanese tradition, so what they do is based on their belief in transcendental cosmic force, and the use of power as the aspect of social relationship occurs in a community with the aforementioned belief (Weber, Citation1978). A social system, furthermore, can be extended to produce structures of domination in the form organisation space and time for spatial and regional development (Giddens, Citation2010). The spatial management of sacred spaces in Magersari, thus, is a social practice to reproduce power. The belief in a system has been merged with social stratification where the difference of social status and strong tradition exists among the people Weber (Citation1978), and such condition happens in Javanese community in Magersari settlement that becomes that part of Surakarta Sunanate Palace.

3.4. Genius loci and spirit of place

Genius loci of Magersari settlement were created from the habit of the people in obeying the kings’ orders related to how to preserve the originality places or buildings, so the spirit of places was well maintained. The knowledge in how to keep the original places or buildings intact is passed down in the form of orders (“dhawuh”) passed down from generation to generation through oral storytelling. To experience such storytelling is the genius loci which are based on the local culture since the Magersari people interpretation of sacred spaces is according to their kings’ repeated orders; it is the Magersari people, as the subject, who perceive the kings’ orders to manage a place that makes the place possesses strong meaning and character, hence the clear connection among meanings, places (objects), and users (subjects) (Norberg-Schulz, Citation2000).

Following what Eliade stated, the findings related to the sacred spaces in Magersari settlement have shown that the concept of sacredness is not universal. Daily experiencing the kings’ orders in the form of storytelling made to preserve the original spaces are interpreted, the people of Magersari interpret these orders as a command to make the spaces sacred. Eliade (Citation1987), furthermore, explained when a profane object is perceived by humans with specific or different ways differently, it will make this object authentic.

4. Conclusion

Sacredness can be created in a place provided with myths that are believed by the local people. The rulers play significant roles in creating sacredness of places as the spirit of places. The people’s belief in sacred spaces created by the ruler can become the genius loci that can survive until now or even in the future. The creation of the spirit of places was done to reproduce authority for an area. Traditional people believe that sacred spaces have spirits of places that must be preserved. The uniqueness of sacred spaces is built through oral storytelling passed down from generation to generation, so it becomes myths. Sacred spaces, in addition, are rooms, buildings, or places that its originality is well preserved as a result of the interpretation of local people to these spaces.

Genius loci depend heavily on the local tradition in preserving the relationship among objects, users, and meanings. Genius loci can be tradition-based knowledge of local people in the form of oral storytelling passed down from generation to generation and believed to have sacred power interpreted by the people as the spirit of places. The power of spoken words functions effectively provided there is an agreement among the local people as the media to reproduce the spirit of places. The theoretical construction of creating meaningful places possessing the spirit of places can be created through: (1) the local culture having strong characters; (2) the rulers who control the management of spaces and who creates the spirit of places; (3) the existence of original buildings; (4) the community who believe in the truth of the spirit of places; (5) the obedience to the rulers; (6) the media to pass down genius loci from generation to generation.

Therefore, the role of the ruler and his people is vital in creating the spirit of places including sacred spaces. Understanding genius loci and the spirit of places, the ruler and his people can maintain and develop time-adaptive meanings of places; the author then hopes that this research can be the important topic for developing the spirits of places.

The limitation of this research is that it can only be conducted in a place considered as settlement inside a traditional kingdom in which its people show significantly complete obedience to the ruler. This research, hence, may continue to the research on the roles of Surakarta Sunanate Palace and Yogyakarta Sultanate Palace in creating the spirits of places since both of these palaces have the same Javanese root where the Surakarta palace was established firstly. By comparing both palaces, the theoretical construction of Javanese palaces (keraton) can be obtained.

Acknowledgements

The author expresses her gratitude to Universitas Sebelas Maret (UNS) and LPPM-UNS (the university’s research institution) where she works and which facilitates her research, as well as the Surakarta Sunanate palace, Baluwarti village and the Magersari community that have become the locus of this research.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Avi Marlina

My name is Avi Marlina; I was born in Surakarta on 17 May 1972. I teach architecture in UNS, Surakarta. As a member of IPLBI (Association of Indonesian Built Environment Researchers) and IAI (Association of Indonesian Architects), my researches focus on Javanese palace architecture. Studying Javanese palaces especially its settlement, philosophy, and interpretation has become my passion. I have been conducting researches on Javanese palaces from 2001, particularly on the symbolic meaning of Javanese palaces, the Magersari settlement, and the Javanese palace development as the cultural heritage tourism. Some of my articles about Surakarta Sunanate Palace and the Magersari settlement have been published in international seminars. Furthermore, two of my books discussing the same topics will be published at the end of 2020. Now, I am still doing further research on the development of Surakarta Sunanate Palace as the heritage tourism industry.

References

- Adrisijanti, I. (2000). Arkeologi Perkotaan Mataram Islam. Penerbit Jendela.

- Ashgate & Surrey. (2013). Queer spiritual spaces: Sexuality and sacred places, Kath Browne, Sally R Munt, Andrew K (Emotion, Space and Society). pp. 64–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/rsr.12005

- Bar, D. (2018). Between Muslim and Jewish sanctity:. Judaizing Muslim Holy Places in the State of Israel,1948-1967. Journal of Historical Geography, 59, 75–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhg.2017.11.003

- Bardaji, T., Martinez-Grana, A., Sanchez-Moral, S., Pethen, H., Garcia-Gonzalez, D., Cuezva, S., Canaveras, J., & Jimenez-Higueras, A. (2017). Geomorphology of Dra Abu el-Naga(Egypt): The basis of the funerary sacred landscape. Journal of African Earth Sciences, 131, 249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2017.02.036

- Behrend, T. E. (1982). Kraton and cosmos in traditional java. University of Wisconsin-Madison.

- Benz, I. N. A. C. R. (1998). Qualitative research methodology quantitative exploring the interactive continuum. Southern Illinois University Press, America.

- Berriane, J. (2015). Pilgrimage, spiritual tourism and the shaping of transnational’Imagined communities’: the case of the Tidjani Ziyara to Fez. International Journal of Religious Tourism and Pilgrimage, 3(2), 9. https://doi.org/10.21427/D7GX30

- Brandt, J. S., Butsic, V., Schwab, B., Kuemmerle, T., & Radeloff, V. (2015). The relative effectiveness of protected areas, a logging ban, and sacred areas for old-growth forest protection in southwest China (pp. 6–7). Biological Conservation.

- Budiardjo, M., Soemardi, S., Anderson, B. R., Koentjaraningrat, M. S., & Zainuddin, A. R. (1991). Aneka Pemikiran Tentang Kuasa dan Wibawa. Pustaka Sinar Harapan.

- Carlson, J. B. (1990). Mapping the cosmos. National Geographic.

- Coleman, J. (1997). Control in modern society. In Authority, power, leadership: SociologicalUnderstandings. New Theology Review, 10(3), 31-44. Octagon Books.

- Creswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design choosing among five traditions. SAGE Publications Inc.

- Cross, J. E. (2001). What is sense of place. In 12th headwaters conference Western State College. Colorado.

- Day, C. (2002). Spirit and place healing our environment healing environment. Architectural Press is An imprint of Elsevier.

- Eliade, M. (1969). Images and symbols studies in religious symbolism. Harvill Press.

- Eliade, M. (1987). The sacred and the profane the nature of religion the significance of religious myth, symbolism, and ritual within life and culture. A Harvest Book Harcourt Brace & World Inc New York.

- Geldern, R. H. (1982). Konsepsi tentang negara & kedudukan raja di Asia Tenggara. Rajawali.

- Giddens, A. (2010). Teori strukturasi Dasar-dasar Pembentukan Struktur Sosial Masyarakat. Pustaka Pelajar.

- Indrawati, N., & Muthali’in, A. (2016). Identification the cultural landscape component for pilgrimage tourism development in the Majasto village (the sites of Waliselawe-an Islamic leader in XV-XVI centuries). Advanced Innovation on Engineering and Applied Science (pp. 51-61 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/318850198).

- Indrawati, S., Setioko, S., Murtini, B., & Nurhasan., T. W. (2016). Edu-religious tourism based on Islamic architecture approach, a preliminary research in Majasto cemetery-Sukoharjo Regency Central Java. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 227, 658–662. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.06.129

- Jaganmohan, M., Vailshery, L. S., Mundoli, S., & Nagendra, H. (2018). Biodiversity in sacred urban spaces of Bengkulu, India. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 32, 66–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2018.03.021

- Kim, B., Kim, S. S., & King, B. (2016). The Sacred and the profane: Identifying pilgrim traveler value orientations using means-end theory. Tourism Management, 56, 150–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.04.003

- Larson, G. D. (1990). Masa Menjelang Revolusi Kraton dan Kehidupan Politik di Surakarta, 1912-1942. Gadjah Mada University Press.

- Leith, S. A., & Wilson, A. E. (2014). When size justifies: Intergroup attitudes and subjective size judgments of “sacred space”. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 54, 122, 130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2014.05.003

- Marlina, A. (2018). Residential space transformation as the legitimacy space A case study: Magersari Ndalem Sasanamulya Baluwarti Sunanate Palace of Surakarta. In 2nd ICSADU International Conference on Sustainability in Architectural Design and Urbanism; IOP Conf.Series: Earthand environmental Science. Semarang: IOP Publishing.

- Meagher, B. R. (2018). Deciphering the religious orientation of a sacred space: Disparate impressions of worship settings by congregants and external observers. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 55, 70,74,78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2017.12.007

- Moedjanto, G. (1987). Konsep Kekuasaan Jawa: Penerapannya oleh Raja-raja Mataram. Penerbit Kanisius.

- Moertono, S. (1985). Negara dan Usaha Bina-Negara Di Jawa Masa Lampau; Studi Tentang Masa Mataram II Abad XVI Sampai XIX. Yayasan Obor Indonesia.

- Norberg-Schulz, C. (2000). Genius loci towards A phenomenology of architecture (pp. 108–180). Rizzoli.

- Ossenbruggen, F. D. E. V. (1975). Asal-Usul Konsep Jawa Tentang Mancapat Dalam Hubungannya Dengan Sistim-Sistim Klasifikasi Primitif. Bhratara.

- Owley, J. (2015). Cultural heritage conservation easements: Heritageprotection with property law tools (pp. 180–181). Land Use Policy.

- Priatmodjo, D. (2004). Keraton Kasunanan Surakarta Masa Kini: Suatu Kajian Antropologi Tentang Reposisi Kerajaan Tradisional. Disertasi, Program Studi Antropologi, Universitas Indonesia, Universitas Indonesia.

- Purwani, O. (2017). Javanese cosmological layout as political space. Cities, 61, 74–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2016.05.004

- Puspitasari, P., Djunaedi, S. A., & Putra, H. S. A. (2012). Ritual and space structure: Pilgrimage and space use in historical urban kampung context of Luar Batang (Jakarta, Indonesia). Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 36, 358–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.03.039

- Ramadhana, D., & Dharoko, A. (2018). Ruang Sakral dan Profan Dalam Arsitektur Masjid Agung Demak, Jawa Tengah. Inersia, 14(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.21831/inersia.v14i1.19491

- Rutte, C. (2011). The sacred commons: Conflicts and solution of resource management in sacred natural sites. Biological Conservation, 144(10), 2392–2393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2011.06.017

- Santoso, J. (2008). Arsitektur-kota Jawa Kosmos, Kultur & Kuasa. Centropolis-Magister Teknik Perencanaan Universitas Tarumanegara.

- Sardjono, A. B., & Harani, A. R. (2017). Sacred Space in Community settlement of Kudus Kulon, Central Java, Indonesia. ICSADU, IOP Publishing.

- Sell, C. E. (2017). The two concepts of patrimonialism in max weber: FromThe domestic model to the organizational model. Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC) Florianopolis.

- Sicherman, H. (2011). The sacred and the profane: Judaismand international relations. In The sixth annual Templeton Lecture on Religion and World Affairs, (Vol. 55(3), pp. 383–384). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orbis.2011.04.006

- Soemardjan, S. (2009). Social changes in Jogyakarta. Komunitas Bambu.

- Soeratman, D. (2000). Kehidupan Dunia Keraton Surakarta 1830-1939. Yayasan Untuk Indonesia.

- Terzidou, M., Scarles, C., & Saunders, M. N. (2018). The complexities of religious tourism motivations: Sacred places, vows and vision. Annals of Tourism Research, 70, 62–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.02.011

- Tjahjono, G. (1989). Cosmos, center, and duality in Javanese architectural tradition: The symbolic dimensions of house shapes in Kota Gede and Surroundings. University of California.

- Tuan, Y.-F. (2001). Space and place the perspective of experience. University of Minnesota Press Minneapolis London.

- Weber, M. (1978). Economy and society an outline of interpretive sociology. University of California Press.

- Widayati, N. (2015). Baluwerti Menuju “Kampung Merdeka” Kajian Permukiman Abdi Dalem dan Sentana Dalem di Kasunanan Surakarta [Disertasi]. Program Doktoral Departemen Teknik Arsitektur, Universitas Indonesia.

- Wiryomartono, A. B. P. (1995). Seni Bangunan dan Seni Binakota di Indonesia Kajian Mengenai Konsep, Struktur, dan Elemen Fisik Kota Sejak Peradaban Hindu-Buddha, Islam Hingga Sekarang. PT Gramedia Pustaka Utama.

- Yin, R. K. (1989). Case study research design and methods. SAGE Publications Inc.