Abstract

Double object construction (DOC) seems to be attested across languages and thus has received much attention among linguists since eighties. It has been attested in literature that passivization patterns in double object/applicative constructions are of different types (i.e., symmetric and asymmetric). Different syntactic accounts have been proposed to account for such symmetric and asymmetric typology. In this paper, I propose an analysis that accounts for passivization of DOC in Modern Standard Arabic (MSA). The analysis is based on the recent minimalist framework of which assumes an Agree relation to be established at distance. In addition, the paper argues that the proposed account can be generalized to accommodate the cross-linguistic passivization patterns. The paper also proposes an alternative analysis that can capture the cross-linguistic symmetric vs. asymmetric distinction.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This article focuses on the structure of natural languages in order to gain a better understanding of the basic principles underlying these languages. The present article discusses a syntactic phenomenon that has been and still of great interest for all syntacticians. What is interesting is that languages differ as which of their internal arguments (objects), in double object structures, can move to the subject position in passive. For some languages, only one object can move whereas for other languages either of the two objects can move to the subject position in passive. Hence, the so-called symmetric vs. asymmetric languages typology is established. The present study accounts for such diversity by proposing a syntactic analysis that can be applied cross-linguistically, which aligns with the claims of Universal Grammar.

1. Introduction

It is a well-known fact that languages vary with respect to their internal arguments’ passivizability. Some languages exhibit what is called symmetric pattern while others display an asymmetric pattern. In a symmetric pattern of passivization, either of the two internal arguments can passivize, whereas in an asymmetric pattern, only one object can passivize. In the latter pattern of passivization, two types have been attested in the literature; one where only the higher internal argument can passivize which I call it “asymmetric of Type A”, and the second type is manifested by the passivizability only of the lower internal argument “asymmetric of Type B”. Consequently, languages have been characterized as symmetric and asymmetric languages according to their internal arguments’ passivizability.

Table 1. Parametric variation in symmetric and asymmetric passivization

2. Asymmetric pattern of languages

2.1. Type A

This type of asymmetric languages allows the passivization of only the higher object (i.e., IO). Such languages include, among others, American English, Modern Standard Arabic, Swahili and Chichewa. These facts are illustrated in (1–3) below.

(1) Swahili

a. Fatuma alipewa zawadi na Halima

Fatuma she-past-give-pass. gift by Halima

“Fatuma was given a gift by Halima.”

b. *Zawadi ilipewa Fatuma na Halima

gift it-past-give-pass. Fatuma by Halima

“A gift was given Fatuma by Halima.” (Woolford, Citation1993, p. 6)

(2) American English

a. Mary was given a book.

b. *A book was given Mary.

(3) Chichewa

a. Mbidzi zi- na- gul-ir-idw-a nsapato (ndi kalulu)

zebras SP-past-buy-APPL-pass.-fv shoes (by hare)

“The zebras were bought shoes (by the hare).”

b. * Nsapato zi- na—gul -ir-idw-a mbidzi (ndi kalulu)

shoes SP-past-buy-APPL-pass.-fv zebras (by hare)

“Shoes were bought for the zebras (by the hare).”

(Baker, Citation1988, p. 248)

2.2. Type B

This type of languages behaves opposite to what we have seen above in type A of asymmetric languages. That is, only the lower argument (i.e., DO) can be the subject in passive DOC. This type of languages includes German, Spanish, Hindi/Urdu and Polish, among others.

(4) Hindi/Urdu

a. Raam-ne Siitaa-ko kitaab dikhaa-yii

Ram-erg Sita-dat book showed

“Ram showed Sita a book.”

b.*Siitaa kitaab dikhaa-yii gayii

Sita book showed went

“Sita was shown a book.”

c. kitaab Siitaa-ko dikhaa-yii gayii

book Sita-dat showed went

“A book was shown to Sita.” (Malhotra, Citation2011, p. 148)

(5) Polish

a. Maria dała Janowi kwiaty

Maria.nom gave Jan-dat flowers-acc

“Maria gave Jan flowers.”

b. Kwiatyi zostały dane Janowi ti

flowers.nom became given Jan-dat

“Flowers were given to Jan.”

c. * Jani został dany ti kwiaty

Jan-nom became given flowers-acc

“Jan was given flowers.” (Citko, Citation2011, p. 146)

3. Symmetric pattern of languages

Unlike the asymmetric pattern, the symmetric passivization pattern allows either of the two objects in DOC to raise to the subject position. Examples of this pattern are exhibited in languages like English (British dialects), Kinyarwanda, Norwegian and Swedish.

(6) British English

a. Mary was given a book.

b. A book was given Mary.

(7) Norwegian

a. Jon gav Marit ei klokke

“John gave Mary a watch.”

b. Jon vart gitt ei klokke

“John was given a watch.”

c. Ei klokke vart gitt Jon.

“A watch was given John. ”(Afarli, Citation2006, p. 44)

(8) Swedish

a. Han erbjöds ett nytt jobb

he offered-pass. a new job

“He was offered a new job.”

b. Ett nytt jobb erbjöds honom

a new job offered-pass. him

“A new job was offered him.” (Falk, Citation1990, p. 55)

Another type of passivization is to be found in languages like Greek and Dutch where the lower internal argument (DO) can be passivized only when the higher argument (IO) is a clitic or undergoes some sort of movement (i.e., clitic- doubled as in Greek, scrambling of IO as in Dutch).

(9) Greek

a. ?*To vivlio charistike tis Marias apo ton Petro

he book-nom awarded.pass the Maria-gen from the Petros

“?*The book was awarded Mary by Peter.”

b. To vivlio tis charistike (tis Marias)

the book-nom CL-gen awarded.pass the Maria-gen

“The book was awarded to Mary.” (Anagnostopoulou, Citation2003, p. 72)

(10) Dutch

a. ?* dat het boek waarschijnlijk Marie gegeven wordt

that the book-nom probably Mary-dat given is

“That the book is probably given to Mary.”

b. dat het boek Marie waarschijnlijk gegeven wordt

that the book-nom mary-dat probably given is

“That the book is probably given to Mary.” (Anagnostopoulou, Citation2003, pp. 215 − 216)

4. Previous accounts of symmetric vs. asymmetric passivization

Several studies in the literature have attempted to account for the symmetric vs. asymmetric passivization distinction in DOC (see, for instance, Larson, Citation1988; Woolford, Citation1993; Pesetsky, Citation1995; Ura, Citation1996; Anagnostopoulou, Citation2003; McGinnis, Citation2001; among others). Therefore, this section gives a review of some of the previous accounts undertaken to explain the different patterns of passivization.

4.1. Case-based accounts

According to this approach, the restriction of a DP movement in double object/applicative constructions is attributed to the Case nature of either of the two internal arguments (i.e., goal (IO) or theme (DO)). On the standard assumption, the accusative Case feature of the verb is absorbed in passivization. Chomsky (Citation1981) and Larson (Citation1988), among other linguists, account for this assumption by arguing that the direct object in English DOC is assigned an inherent Case by the verb, therefore its Case is not affected by passive. So, for languages that do not allow the passivization of direct object, like American English, it is assumed that only the indirect object has a structural Case while the direct object’s Case is inherent.

However, this is not true across languages as some languages like German (Haegman, Citation1991) and Mandarin Chinese (Li, Citation1990) may have two structural Cases where only the second object (DO) can move to the subject position in passivization. On the other hand, in Scandinavian languages, the two objects in DOC receive structural Case and either of them can move to the subject position in passivization (Jaeggli, Citation1986).

Another argument against Larson’s assumptions comes from Greek DOC where the theme, according to Anagnostopoulou (Citation2003), is not licensed by assuming the inherent Case hypothesis. That is, Greek has an IO with an inherent morphological genitive/dative Case while the DO is assigned structural Case. Though the two arguments (IO and DO) satisfy their Case requirements, theme cannot be passivized.

On the other hand, Pesetsky (Citation1995) attributes the apparent asymmetry in passivization of (American English) DOC to some properties of the DO instead of the IO. In other words, Pesetsky proposes a structure where the direct object is introduced and probably licensed by the null prepositional element G, which heads the PP complement.

(11) Bill gave Sue [G a book]

Pesetsky attributes the unpassivizability of the DO to the same factor governing the adjacency condition in (12):

(12) a. *Sue gave yesterday Bill a book.

b.? Sue gave Bill yesterday a book.

(13) a. Billi was sent ti a book.

b.* A bookj was sent Bill tj.

The example in (12) shows that the IO has to be adjacent to V and must move in passivization. On the other hand, the DO does not passivize as it is not adjacent to the verb. So, Pesetsky concludes that only the IO can be passivized as it has a structural Case and hence behaves like a regular DP while the DO does not behave as a true underlying object as it is introduced by a null preposition that functions similarly to the overt preposition to.

Baker (Citation1988) argues that it is the Case-theoretic status of the DO that is behind the asymmetric differences among its two types of passivization on the one hand, and between the asymmetric and symmetric passivization patterns on the other. Baker derives the double object as well as the applicative constructions via a process of preposition incorporation (i.e., the applicative affix), being overt in applicative constructions but covert in double object constructions. Further, he assumes that a DP can be assigned Case by an overt head under adjacency. Thus, the IO argument moves to the position next to the complex verb (i.e., the incorporated complex), as in (14), to satisfy the adjacency requirement of a structural Case assignment.

For Baker, the Case-theoretic status of the DO (theme) is subject to parametric variation while the IO (goal) is Case-licensed in all languages. That is, all the partial double object (asymmetric) languages like English can only assign a single structural Case, which is taken by the IO. In this case, the theme ends up without a structural Case; and thus, it has to undergo a noun incorporation (or covert noun reanalysis) which makes the theme visible for theta role assignment without the mediation of Case. It is the lack of structural Case that prevents the DO from taking part in passivization.

In true (symmetric) double object languages, the (complex) verb has the ability to assign more than a single structural Case. Therefore, the DO in this type of languages can be assigned structural Case and thus passivized (for argument against Baker’s position, see Anagnostopoulou (Citation2003) and Lee (Citation2004)).

4.2. Locality-based accounts

After the introduction of the Minimalist Program, the proposals undertaken to account for the symmetric and asymmetric passivization became more “locality oriented”. Since Barss and Lasnik (Citation1986), Larson (Citation1988), among others, the IO is argued to asymmetrically c-command the DO in DOC. This, in fact, accounts for the ungrammaticality of DO passivization. That is to say, to passivize the DO, it has to raise to T across the intervening IO, which results in violation of the general constraint on movement:

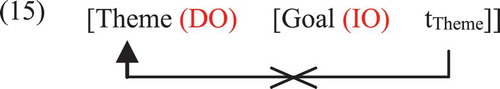

As is seen in (15), the IO, being in a higher position, blocks the movement of the lower DO over it. On the other hand, when the IO moves to T, it respects the locality constraint on A-movement as it is in a higher position and thus no intervention effects arise as a result of its movement.

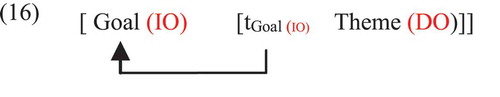

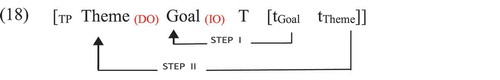

To obviate the locality violation in DO passivization in true double object (symmetric) languages and also in the partial double object (asymmetric) type of languages, there are different strategies to evade the above intervention effects. For instance, Ura (Citation1996), McGinnis (Citation1998), and Anagnostopoulou (Citation2003) assume the multiple specifier position of the head hosting the indirect object, as illustrated in (17):

The assumption is that in a symmetric double object language, the theme passivization is possible via a successive cyclic movement to T (escape hatch strategy). First, it moves to the second specifier position of the same head that hosts the indirect object, and from there it moves to T.

Another locality circumvention strategy I mentioned above is used to account for languages like Greek and Dutch where DO passivization is possible only when the IO undergoes movement of some sort and hence becomes invisible for blocking the movement of the DO over it. Such a strategy is schematized in (18).

In fact, locality accounts have another advantage as they are applicable to other A-movement contexts such as object shift in ditransitives, locative and dative inversion, and raising across an experiencer in Greek, English, Japanese and similar languages (See Anagnostopoulou, Citation2003; McGinnis, Citation1998).

After having reviewed the two different approaches proposed to account for the different passivization patterns of double object/applicative constructions, I will present some previous analyses that adopt locality approach.

4.2.1. Anagnostopoulou’s (Citation2003) parametric analysis

The analysis proposed by Anagnostopoulou is framed within Chomsky’s (Citation1995a) model. That is, Anagnostopoulou follows the Chomskyan assumption that displacement in natural languages is a computational operation that is assumed to be Feature Attraction and Move. Feature Attraction affects the phrase that has the appropriate features and is closest to the target, as stated in (22).

(22) Shortest Move/Closest Attract (Chomsky, Citation1995a, p. 297)

K attracts F if F is the closest feature that can enter into a checking relation with a sublabel of K.

The closeness depends on the notion of a minimal domain, as specified in the version of the Minimal Link Condition (MLC) in (23).

(23) If β c-commands α, and τ is the target of movement, then β is closer to τ than α unless β is in the same minimal domain as (i) α or (ii) τ.

The Minimal Link Condition is relativized to minimal domains and not just defined in terms of c-command in Chomsky’s (Citation1995a) system. Based on these assumptions, Anagnostopoulou (Citation2003) adopts Marantz’s (Citation1993) proposal as a universal representation for double object/Applicative constructions cross-linguistically. The structure is schematized in (24).

In (24), the two internal arguments (i.e., IO and DO are not in the same minimal domain. The IO is closer to T than the DO, hence the DO cannot move over the IO as it violates the Shortest Move which results in ungrammaticality.

Passivization of the IO argument is in conformity with locality condition whereas the passivization of the DO argument is obviously a non-local operation. To account for DO passivization in symmetric passive languages, Anagnostopoulou proposes what she calls “The Specifier to vAPPL parameter” given in (25).

(25) The specifier to vAppl parameter (Anagnostopoulou, Citation2003, p. 157)

Symmetric movement languages license movement of DO to a specifier of vAppl. In languages with asymmetric movement, movement of DO may not proceed via vAppl.

The symmetric passive languages capitalize on the extra specifier position of vAPPL, through which the DO moves to the specifier of T as shown in (26) below:

Intermediate movement of DO to [Spec, vAPPL] on its way to [Spec, T] makes both DO and IO equidistant from the target T (cf. Chomsky, Citation1995a). Thus, either the DO or the IO can be passivized in conformity with locality. On the other hand, the asymmetric languages don’t have the option of moving the DO to spec-vAppl by the parameter setting. Therefore, moving the DO over the IO directly to T incurs a minimal link condition violation.

4.2.2. McGinnis’s (Citation2001, Citation2004) phase-based analysis

McGinnis (Citation2001, Citation2004) argues that symmetric and asymmetric double object languages correspond to high and low applicative structures, respectively.Footnote1 In her account, McGinnis attempts to derive the escape hatch effect by adopting the theory of applicatives (Marantz, 1993 and Pylkkänen, Citation2002/Citation2008) and the theory of phases (Chomsky, Citation2000 & Citation2001).

According to the phase theory, syntactic derivations proceed in chunks or phases; and once a phase is complete, its complement domain is sent to phonological and semantic spell-out simultaneously.

McGinnis attributes the distinction between high and low applicatives and hence, symmetric vs. asymmetric passivization, to a phasal distinction. That is, the cross-linguistic variation in the availability of symmetric passivization is linked to whether a language has a high applicative. She proposes that a high applicative is a phase, which means it has an EPP feature that allows the DO to move over the IO (to the outer specifier position above IO). From this position, the DO becomes closer to T for the purpose of passivization.Footnote2

Alternatively, the IO can move to the specifier of T, as it is already merged into the phase edge (i.e., high applicative). Hence, having a high applicative structure, a language allows symmetric passivization. On the other hand, low applicative head is not a phase head, and hence does not have an EPP feature to attract the DO to its outer specifier position in order to serve as an escape hatch through which the DO can move to T in passivization. Therefore, only the IO can undergo passivization in asymmetric type of languages.

In (28) above, the two objects are embedded within the domain of the vP phase. So, being a non-phase, the low applicative head cannot provide an escape hatch for the movement of the DO to its outer specifier; and also it could not move over the IO directly to the phase edge, as such a movement violates the locality condition.

Though McGinnis’s analysis is superior to Ura’s (Citation1996) and Anagnostopoulou’s (Citation2003) in reducing the escape hatch effect to independent properties of derivations, it has some problems. As indicated in Jeong (Citation2007), there appear to be instances of low applicative languages like Haya which unexpectedly give rise to symmetric passivization. Similarly, there are also instances of high applicative structures where only the higher object (i.e., IO) can be passivized. This is to be attested in Kinyarwanda high locative applicative.Footnote3

So far, we have noticed that the locality-based accounts seem to provide a better account for passivization in symmetric patterns and also for the passivization in one type of asymmetric patterns (the A-type of asymmetric passivization). The passivization of the lower argument (i.e., DO) in double object languages is possible only if either of the two locality strategies is utilized; namely, the escape hatch strategy Ura (Citation1996), Anagnostopoulou (Citation2003) or the pre-condition that the higher argument also moves (Anagnostopoulou, Citation2003; McGinnis, Citation2001). A question that arises at this moment is what about the passivization of the lower argument in asymmetric languages (the B-type)? Such languages include Hindi/Urdu (Malhotra, Citation2011), Polish (Swan, Citation2002), Turkish (Öztürk, Citation2006), Georgian (McGinnis, Citation1998), and similar languages where, unlike Greek and Dutch, the passivization of the lower argument does not involve any preconditioned movement of the higher argument. Which approach is suitable for driving such passivization? The answer to this question will be clear in later sections of this paper.

5. Passivization in modern standard Arabic

5.1. Background

The passive construction in Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) is formed by posing some morphological changes to the verb without affecting its root.Footnote4 The morphological change in expressing passive forms of the verb has to do entirely with vowels. Therefore, we can say that passives in MSA are synthetic where their form surfaces with a passive morphology (glossed, henceforth, pass.). Compare the following examples:

(29) a. kataba ʕali-un ʔad-dars-a

wrote.3.s.m Ali-nom the-lesson-acc (Active)

“Ali wrote the lesson.”

b. kutiba d-dars-u

wrote.pass.3.s.m the-lesson-nom (Passive)

“The lesson was written.”

(30) a. qatala l-jayʃ-u l-mutamaridd-iin

killed.3.s.m the-army-nom the-rebels-acc (Active)

“The army killed the rebels.”

b. qutila l-mutamaridd-oon

killed.pass.3.s.m the-rebels-nom (Passive)

“The rebels were killed.”

As the passivized verb bears a specific morphology, it affects the morphological Case of its object. That is, the morphologically marked accusative object becomes the nominative subject as seen in (29–30).Footnote5

Unlike English, MSA does not allow the demotion of the subject to a “by-phrase” adjunction. Rather, the subject is deleted. Hence, the term majhool, which literally means “unknown”, is used for the passive construction.

(31) kutiba d-dars-u

wrote.pass.3.s.m the-lesson-nom

“The lesson was written.”

(32) * kutiba d-dars-u biwasiTati ʕali-in

wrote.pass.3.s.m the-lesson-nom by Ali-gen

“The lesson was written by Ali.”

According to Arab grammarians, the subject cannot be mentioned in passive constructions for different reasons; for instance, the subject might be unknown, unimportant, or sometimes it is not mentioned as the speaker fears him.

Generally, the subject of a passive structure in Arabic is referred to as naaʔib ʔal-faaʕil, literally “the deputy actor or doer” (substitute for the subject); and the structure which undergoes such process as mabni le-l-majhool, i.e., passive voice construction.

Maalej (Citation1999) also states:

There is unanimous agreement among early and modern grammarians that the mabni le-l-majhool occasions the syntactic erasure of the subject-actor and its substitution by the object- affected noun, which not only occupies its position but also assumes all the diacritic features a subject usually takes.,Footnote6,Footnote7

However, there is a slight inclination in MSA among Arab grammarians towards accepting the demotion of the agent using some prepositional phrases. This might be possible in some contexts, but not always especially in journalese. (Maalej (Citation1999)).

It is worth mentioning that, in some cases, it is also possible for the passivized object to appear preverbally.Footnote8 However, this might be a result of a discourse-related (information structure) movement.

(33) ʔad-dars-u kutiba

the-lesson-nom wrote-pass.3sm

“The lesson was written.”

(34) ʔal-ʔawlaad-u ʔursiloo ʔilaa l-madrasat-i

the-boys-nom sent.pass.3.p.m to the-school-gen

“The boys were sent to the school.”

Another fact that draws our attention is the passivization structure with prepositional phrases as well as quantificational phrases like (35):

(35) a. qubidha ʕalaa l-liSooS-i

arrested.pass.3.s.m on the-thieves-gen

“The thieves were arrested.” (Soltan, Citation2007, p. 106)

b. rukiba ʕalaa T-Taaʔirat-i

rode.pass.3.s.m on the-plane-gen

“The plane was ridden on.”

c. qutila ʔaʕghlab-u l-mutamarrid-iin

killed.pass.3.s.m most-nom the-rebels-gen

“Most of the rebels were killed.”

Notice that in this case the verb takes default agreement inflection (i.e., 3.s.m). I attribute this to the DP being embedded in a PP which prevents the verb of getting the partial agreement we used to get in a VS order (i.e., person and gender). Surprisingly, even if the DP embedded in a PP moves to a preverbal position, for whatever reason (most probably to a Topic (A’) position), still the verb does not show any change in agreement.

(36) a. ʔal-lliSooS-u qubidha ʕalay-him

the-thieves-nom arrested.pass.3.s.m on-them

“The thieves were arrested.”

b. ʔaT-Taaʔirat-u rukiba ʕalaa-yhaa

the-plane-nom rode.pass.3.s.m on-her

“The plane was ridden on.”

c. ʔal-mutamarrid-oon qutila aghlab-a-hum

the-rebels-nom killed.pass.3.s.m most-acc-them

“Most of the rebels were killed.”

On the contrary, passivization of a DP shows similar inflectional agreement on the verb exactly as in the active sentence with respect to the VS and SV word orders.

(37) a. Duriba l-ʔawlaad-u ʕiqaab-an la-hum

beaten.pass.3.s.m the-boys-nom punishment-acc to-them

“The boys were beaten as a punishment for them.”

b. ʔal-ʔawlaad-u Duriboo ʕiqaab-an la-hum

the-boys-nom beaten.pass.3.p.m punishment-acc to-them

“The boys were beaten as a punishment for them.”

(38) a. ʔursilat ʔal-banaat-u ʔilaa l-madrasat-i

sent.pass.3.s.f the-girls-nom to the-school-gen

“The girls were sent to the school.”

b. ʔal-banaat-u ʔursil-na ʔilaa l-madrasat-i

the-girls-nom sent.pass.3.p.f to the-school-gen

“The girls were sent to the school.”

Therefore, I assume that in passivization where there is only a prepositional or quantifier phrase like those in (35 & 36), there is an arbitrary pro with default agreement φ features (i.e., 3.s.m) and this is due to the non-availability of a DP that is accessible for the T probe; and because the PP blocks the agreement between T and the DP being embedded in the PP. On the other hand, when the DP object is accessible for the higher probe as in (33 & 34), Agree relation is established between the higher probe and the DP and we get a situation similar to that found in active voice construction of both word orders (i.e., VS & SV).

Before discussing the passivization construction of the double object construction in MSA, it is worth pointing out some basic facts of MSA concerning passivization in general:

Unlike English, displacement of the object (to the subject position) is not required in MSA as the VSO is the unmarked word order. Hence, I will attribute the object movement to the subject position in passivization of MSA to the same factor that derives the SVO order in the language.

The derivation of passives in MSA is mostly an in-situ phenomenon.

Though the passive constructions in MSA are agentless, in the sense that the agent cannot be demoted and appear at the end of the sentence with a “by-phrase”.

5.2. Passivization of MSA double object construction

Passivization of a DOC in MSA is similar to that of (American) English. That is, only the higher object (i.e., IO) can be the subject in such constructions. Hence, MSA is an asymmetric passive language of type A.Footnote9 Consider the following:

(39) a. ʔaʕTaa ʕali-un ʔal-fataat-a l-kitaab-a

gave.3.s.m Ali-nom the-girl-acc the-book-acc Active

“Ali gave the girl the book.”

b. ʔuʕTiyati il-fataat-u l-kitaab-a

gave.pass.3.s.f the-girl-nom the-book-acc (IO Passivization)

“The girl was given the book.”

c.*ʔuʕTiya l-kitaab-u l-fataat-a

gave.pass.3.s.m the book-nom the-girl-acc (DO Passivization)

“*The book was given the girl.”

(40) a. Ɂahdaa Moћammad-un ʔal-bint-a wardat-an

gifted.3.s.m Mohammed-nom the-girl-acc rose-acc Active

“Mohammed gifted a rose to the girl.”

b. ʔuhdiyat ʔal-bint-u wardat-an

gifted.pass.3.s.f the-girl-nom rose-acc (IO Passivization)

“The girl was gifted a rose”

c. *ʔuhdiyat wardat-un ʔal-bint-a

gifted.pass.3.s.f rose-nom the-girl-acc (DO Passivization)

“The girl was gifted a rose”

As is clear from (39) and (40), only the IO can be the subject of double object passive constructions. Passivizing the DO results in ungrammaticality.

An important point to be noticed here while discussing passivization of the DOC in MSA is that, when the indirect object (goal) is a pronoun, we get the scenario illustrated below:

(41) a. ʔaʕTa-hu ʕali-un ʔal-kitaab-aFootnote10

gave.3.s.m-him Ali-nom the book-acc Active

“Ali gave him the book.”

b. ʔuʕTiya l-kitaab-a

gave.pass.3.s.m the book-acc (IO Passivization)

c.*ʔuʕTiya l-kitaab-u

gave.pass.3.s.m the book-nom (DO Passivization)

Surprisingly, the passivized IO is missing while the DO is still carrying an accusative Case. This leads us to question the reason behind the unavailability of the indirect object pronoun that is supposed to be the subject in (41b); and why the DO cannot be the subject of the passive sentence in such a case (41 c) with a nominative Case.

As for the first puzzle, the unavailability or non-appearance of the IO pronoun in passivization is attributed to the fact that MSA is a pro-drop language, where the subject can be covert and therefore understood without its realization, especially if it is pronominal. Consider the following examples:

(42) a. ʔaʕTaa-haa ʕali-un ʔal-kitaab-a

gave.3.s.m-her Ali-nom the book-acc Active

“Ali gave her the book.”

b. ʔuʕTiya-t ʔal-kitaab-a

gave.pass-3.s.f the book-acc (IO Passivization)

“She was given the book.”

c. *ʔuʕTiya-t ʔal-kitaab-u

gave.pass.3.s.f the book-nom (DO Passivization)

“She was given the book.”

d. *ʔuʕTiya l-kitaab-u

gave.pass.3.s.m the book-nom (IO Passivization)

“*The book was given her.”

The IO in (42) is the pronominal haa “her”, in this case the IO does not have the same φ features with the DO unlike that in (42) where the indirect pronominal object and the DO have similar φ features (i.e, 3rd, Singular, Masculine). The subject-verb agreement is manifested in MSA as an inflection on the verb regardless of the realization of the subject (i.e., being overt or covert). (For more discussion on verbal agreement, see Saeed (Citation2011), Soltan (Citation2007), and Fassi Fehri (Citation1993), among others.) Notice that in (42) the inflection on the passive verb indicates the agreement with a feminine gender which is the covert subject “she”. Hence, the answer to the second question becomes clear. That is, the DO in (42 c and 42 c) cannot get the nominative Case for two reasons; first, the subject of these examples is expressed covertly as the agreement on the verb indicates. Second, it is impossible to get both objects passivized at the same time though it might be possible for either of the two objects to undergo passivization in symmetric languages but not simultaneously. Semantically, examples like (41 c & 42 c) are impossible as the ditransitive verb cannot dispense with either of its internal arguments along with its external argument in passivization. Instead, the passivization of a ditransitive verb cross-linguistically undergoes an agent demotion/deletion; and one or either of its objects is promoted to a subject position. Therefore, (41 c & 42 c) are ungrammatical as the IO is the object to be passivized and because of being a pronoun, it is obligatorily dropped, as there is no clitic nominative pronoun.Footnote11 Instead, the DO is incorrectly assumed to be the subject with a nominative Case. On the other hand, (42 c) is ungrammatical because the passive verb is already inflected with a feminine marker as an agreement with covert subject “she” (the indirect pronominal object that is obligatorily dropped); and therefore the DO must carry the accusative Case as an object rather than the nominative Case.

An obvious prediction from the following structure for DOC, where the IO is generated above DO, is that the IO is the optimal candidate for passivization, as this does not induce locality violation.

As mentioned above, passivization in MSA is to be added to the inventory of the asymmetric pattern of languages where only the higher argument can be passivized. According to the locality condition, the ungrammaticality of DO passivization is explained as an apparent locality violation in the language. In other words, the passivization of DO in (41) and (42) above can be attributed to the fact that the IO, being higher in the structure above and thus closer to the target, blocks the movement of the DO over it.

A conclusion that one may get throughout the previous discussion of passivization structures in MSA is that only a Case-driven Agree holds for passive construction. EPP, on the other hand, does not have any role in this regard; and therefore, it cannot motivate movement in passive structures of MSA. Instead, I assume that passivization in MSA is an in-situ phenomenon.Footnote12,Footnote13

In fact, an in-situ feature valuation is an attested phenomenon which might be a language-specific property. Therefore, though it might be possible for MSA, generalizing the Case-driven Agree to be the only mechanism that accounts for the passive variation cross-linguistically won’t be a valid option for many reasons as I will show through the discussion in the next section.

6. Towards the proposal

6.1. A hybrid approach for symmetric and asymmetric passivization

In passive, there is no external argument introduced. The head v is defective, in the sense that its φ-features are suppressed and consequently loses the ability to check/value the Case feature of its internal argument (i.e., IO). For the DO, it gets its φ-features/Case valued in the usual way it does in active context. That is, the DO is probed by the vAPPL and gets its Case valued as Accusative. Since IO has not got its φ-features/Case valued, it is an active goal for a higher probe (cf. Chomsky, Citation2000 &, Citation2001), it is probed by T and gets its φ-features checked and its Case valued as Nominative. The EPP of T, I assume at least in MSA, is not required; hence, IO does not need to raise to [Spec, TP] and its φ-features/Case is valued in situ via a long-distance Agree with T. Assuming so, this in-situ long-distance agreement does not involve any locality violation as the IO is still the higher argument to be passivized.

Schematically, in passives, the Case features of the internal arguments in MSA double object construction are valued in a way represented in (44) below:

As seen above, passivization of DOC in MSA is asymmetric in which only the higher object (i.e., IO) can be passivized. Similar asymmetric passive languages like Swahili, American English and Danish behave in the same way. The only difference is that the EPP feature of T in these languages is required. Though I assume a Case-driven mechanism of passivization, the situation in these languages where only the higher object moves are in harmony with the standard locality considerations as such operation does not induce any violation.

(45) a. Johni was given ti a book.

b.*A booki was given John ti.

(46) a. Hani blev tilbudt ti en stilling Danish

he was offered a job

b. * En stillingi blev tilbudt han ti

a job was offered him. (McGinnis, Citation1998, p. 73)

(47) a. Fatumai alipewa ti zawadi na Halima

Fatuma she-past-give-pass. gift by Halima Swahili

“Fatuma was given a gift by Halima.”

b. *Zawadii ilipewa Fatuma ti na Halima.

gift it-past-give-pass. Fatuma by Halima

“A gift was given Fatuma by Halima.”

(as cited in Woolford, Citation1993, p. 686)

As is clear from the above examples, the EPP triggers the movement of the higher DP to the [Spec, TP] position; and hence, unlike the situation in MSA, EPP is obligatory in these languages.

In fact, the standard assumptions in literature claim that little v is the only source available for Case checking/valuation of the two internal arguments in DOC (i.e., multiple checking). Hence, it is the only head that is affected by Case-absorption.

On the contrary, I assume two different heads to be responsible for Case valuation in double object/applicative constructions; and relying on the hypothesis that passive morphology suppresses the φ-features and absorbs the Case of the functional head (checking that of the internal argument), it is tempting to assume that either of the two heads (i.e., v or vAPPL) is subject to Case-absorption. That is, v or the vAPPL can undergo Case-absorption and the Case feature of the argument to be valued will be rather probed and thus valued by a higher head (i.e., T).Footnote14,Footnote15 If the Case feature of v is absorbed, then we get the same derivation sketched in (44) above. If, on the other hand, vAPPL gets its Case feature absorbed, and by implementing the Case-driven Agree between T and DO, then we expect the derivation to proceed as illustrated in (48):

But the usual situation in passivization is that when v is deficient, it fails to assign Case and the subject does not get a theta-role. In this case, it is a question of deficiency of a head. So what would be the corresponding situation when vAPPL is deficient? It can’t assign a theta role to the GOAL and can’t assign Case to the THEME!Footnote16 It seems that I am assuming a situation where a head fails to assign Case but still can assign a theta role. In fact, similar situation is followed by Haddican and Holmberg (Citation2012) where in their Grammar 2, Appl cannot assign Case; rather, it assigns only the (benefactive) role but a Linker, which is a higher head, assigns Case. Assuming so, Holmberg (p.c.) admits that their analysis is sort of open for this possibility by separating the Case-assigning property from the theta role assigning property.

Again, a similar situation where a head loses its ability to assign Case but still can assign a theta role is attested in Haya, a Bantu language spoken in Tanzania; where in passive, the theta role of the external argument is expressed as an optional DP. To be more precise, I quote Doggett’s (Citation2004):

The agent in a passive clause in Haya differs from the agent in the other languages … in two respects. First, when it occurs in a passive sentence in Haya, the agent precedes all other verbal arguments. Secondly, it is not introduced by a preposition, but is simply expressed as a DP. (p. 108)

Interestingly, both objects (i.e., DO and IO) in Haya can be passivized. However, DO passives are more restricted than IO passives. That is, the IO can be passivized while the agent is overtly expressed whereas the DO cannot be passivized when the agent is overtly expressed and the IO is full DP. However, DO can be passivized if either the agent is not overtly expressed or if the IO is clitic.

(49) a. omwaan’ a-ka-oolek-w-a kat’ epica

child he-past-show-pass Kato picture

“The child was shown the picture by Kato.”

b. *epica e-k-oolel-w-a kat’ omwaan’

picture it-past-shown-pass Kato child

“The picture was shown (to) the child by Kato.”

c. epica e-k-oolel-w-a omwaan’

picture it-past-shown-pass child

“The picture was shown (to) the child.”

d. ba-ka-mw-oolek-w-a kato

they-past-him-show-pass Kato

“They were shown to him by Kato.”(Doggett, Citation2004, pp. 106–107)

LugandaFootnote17 also, according to Pak (Citation2008), has a passivization structure which patterns exactly the same as in Haya. That is, the agent is not marked by a preposition (cf. Ssekiryango (Citation2006)), and it precedes other postverbal arguments. However, the Case is absorbed by passive morphology and thus the object to be passivized leapfrogs above the external argument in order to be accessible to T.

Suffice it to our argument the possibility to dissociate the theta role from Case assignment/checking.Footnote18 In fact, such assumptions need more scrutiny; however, if they are on the right track, then I end up with an independent, elegant and interesting account for the distinction between symmetric and asymmetric passivization across languages.

Let us go back to the derivation of the structure where I assume the vAPPL gets its Case feature absorbed as illustrated in (48) above.

As I make it clear, the vAPPL is indicated by [- Case]Footnote19 and thus could not value the Case feature of the DO whereas the Case feature of the IO is valued via Agree with v. At this stage of derivation, T probe searches its domain for a goal with matching features to get its features valued. Getting its Case feature valued, IO, according to Citko (Citation2011) and Georgala (Citation2012) is inactive and invisible for the higher probe (contra Chomsky, Citation2000 & Citation2001). Thus, DO is an active goal with matching features. Assuming so, T gets its features checked and values the Case of DO as Nominative. However, such a conclusion is not accurate though it might be true for specific and limited number of languages.

As is clear in the derivation above, the “defective intervention” of Chomsky’s (Citation2000, Citation2001, Citation2005)) appears to be violated.

(50) Defective Intervention (Chomsky, Citation2000, p. 123)

(i) both γ and β match probe P in [… P[… γ … β …]]];

(ii) γ c-commands β;

(iii) γ is inactive; and

(iv) γ blocks the Agree relation between P and β.

That is, IO, though being inactive, blocks the Agree relation to be established between the higher probe T and the lower goal DO. If DO cannot crossover IO in this case, how can we explain the fact found in symmetric passive languages as well as in the asymmetric passive languages of type B, where the lower argument is passivized and moved to the subject position! Thus, a Case-driven mechanism alone cannot account for this fact. Rather, a hybrid mechanism of both standard approaches (Case and Locality) is the optimal solution as we will see shortly.

Contra Chomsky, Haddican and Holmberg (Citation2012) and Broekhuis (Citation2008) assume that the defective intervention effect that Chomsky discusses is primarily based on data from Icelandic constructions where a dative argument acts as a barrier for an Agree relation between T and a Nominative argument (see also Sigurðsson & Holmberg, Citation2008).

Broekhuis (Citation2008) assumes that in Dutch, with a construction similar to Icelandic, an Agree relation can be established between a T probe and a Nominative goal across Dative argument—a fact that proves such agreement is revealed by the possibility of moving the nominative argument to the subject position of the clause across the dative. He attributes such contrast between the two languages to the assumption that Icelandic dative is a “quirky subject” while that of Dutch is not. That is, a quirky subject, Broekhuis assumes, is still active at the time T probes for a goal. Thus, defective intervention effect arises in Icelandic (see (51)) and therefore the nominative goal cannot establish Agree with T but no intervention effect arises in Dutch, as T enters into an Agree relation with the nominative goal (52).

(51) það virðist/*virðast einhverjum manni hestarnir vera seinir

here seems/seem some man.dat the horses.nom be slow (Icelandic)

“The horses seem to some man to be slow.”

(52) Daarom lijken de grafieken Jan/hem tde grafieken niet te kloppen

therefore seem the charts.nom Jan/him.dat not to be-correct (Dutch)

“Therefore, the charts seem to be wrong to Jan/him.” (Broekhuis, Citation2008, p. 137)

Similarly, Hartman (Citation2012) argues that intervention effects do not arise in English when T probes past an intervening experiencer in raising constructions as shown in (53):

(53) John seems to Mary to be happy.(Hartman, Citation2012, pp. 121–122)

Similar argument against defective intervention effects is revealed in Haya and Luganda where T probes IO or DO and either of them can be moved up over an existing subject.

However, I won’t try to involve myself in this issue; rather, I will adopt a strategy that helps circumventing the intervention effects violation. The strategy I adopt is based on Bošković’s (Citation2007) successive-cyclic movementFootnote20 (Cf. Chomsky, Citation2000; Legate, Citation2003; Richards, Citation2012). He implements such movement by pursuing Chomsky’s (Citation2000, Citation2001)) idea of the Activation Condition (AC). Adopting these assumptions, I assume that an element X with an uninterpretable feature is an active goal that has to undergo successive-cyclic movement till it reaches a position where it gets its uninterpretable feature valued. Hence, we expect no look-ahead problem. In fact, the movement of an argument in this case is greedy, because if it does not move, its uninterpretable feature will remain unvalued and thus the derivation will crash.

By adopting the successive-cyclic movement strategy, the analysis in (48) is saved from Chomsky’s intervention effect. That is, by assuming that DO (Theme) argument being an active goal, in the sense that it has uninterpretable Case feature that must be valued, its cyclic-movements out of VP to the outer Spec positions of the higher projections result in being a closer potential goal for the higher probe. Thus, no intervention effect violation is expected as such an operation respects the locality conditions. The movement of the DO begins before T merges, so by the time DO reaches Spec vP, T is merged and an Agree relation is established between T and the DO in Spec vP. Thus, the uninterpretable Case feature of the latter is valued as nominative and moved to Spec TP for EPP purpose.Footnote21 This derivation is represented as in (54).

If the assumptions above are on the right track, then the proposed analysis can account for the symmetric vs. asymmetric distinction cross-linguistically. Therefore, asymmetric passive languages of type B which allow only theme rather than goal passivization are explained as implementing a vAPPL Case feature absorption rather than that of v and vice-versa.

In a nutshell, the symmetric vs. asymmetric passivization distinction boils down to a parametric variation where a language may or may not be [+ symmetric]. That is, if a language is [+symmetric], then it is free to suppress the Case feature of either the little v or the vAPPL. Consequently, either of the two objects can be passivized. Whereas a [-symmetric] language opts only for suppressing the Case feature of only one of the Case checking heads. To be more precise, symmetric vs. asymmetric passivization is subject to the parametric value of [v]; if the languages choose the option [± v], then the language is symmetric and hence can instantiate either ([-v] and [+vAPPL]) or ([+v] and [-vAPPL]). On the other hand, asymmetric passive languages fall into two categories: those which opt only for [-v]/[+vAPPL] and those which opt for [+v]/[-vAPPL], instantiating the type A and type B, respectively.

Notice that I am trying to derive passivization in DOC, assuming the situation where the two DP objects have structural Case feature. However, most of the world’s languages are assumed to have DOCs with one object bearing a structural Case and the other one with an inherent Case. Therefore, the passivization process is subject, in this case, to what kind of Case the object is bearing. That is, only the structural Case object, be it the indirect or the direct object, is allowed to undergo passivization. The inherent Case object is inert or inactive and hence invisible for establishing Agree between a higher probe and an active argument lower than this inherent Case object. Thus, no intervention effect arises in this case.

6.2. Alternative account

An alternative account for symmetric vs. asymmetric distinction can be conceived following the standard assumptions in literature that in passives only v can absorb the Case feature. In active voice of double object/applicative constructions, v as well as vAPPL can check/value the Case features of the two internal arguments.

Recall that I assumed, following Georgala (Citation2012), that EPP feature is uncoupled from Agree. That is, movement that is triggered or attracted by EPP may not be always associated with Agree. Rather, these two operations are freely ordered.

Assuming so, the Case feature of the DP arguments in an active DOC proceeds in the usual way I mentioned above. However, passivization of such constructions will have a different derivation of that we saw earlier. Let us see how it goes and how the symmetric vs. asymmetric passives can be captured.

6.2.1. Asymmetric passivization

In asymmetric languages of type A, passivization will proceed as explained above in the previous section. That is, if the language has a thematic applicative, then IO is already base-generated in its spec position. But, if the language has raising applicative construction, where IO is generated in [Spec, VP], then the language is using the option of EPP of vAPPL applying before Agree. So, IO raises to [Spec, vAPPL]. In either case, our derivation should end up with IO being in [Spec, vAPPL]. Being defective, v cannot value the Case feature of IO; hence, IO is probed by T and gets its Case valued as Nominative. DO, on the other hand, is probed down by vAPPL and gets its accusative Case valued. This is the case of asymmetric passive languages that allow only the higher argument to be the subject in passive structures. For instance, MSA, American English , etc.

In the B type of asymmetric languages, the DO cannot get its Case feature valued. This is due to the precedence of Agree operation over EPP. That is, in raising applicatives, the vAPPL head probes IO and values its uninterpretable Case feature, then EPP applies and triggers the movement of IO to [Spec, vAPPL]. Up to this stage of derivation, DO does not get its Case feature checked/valued.

As the derivation proceeds, vPAPPL merges with the defective v, which loses the ability to value DO Case feature. Then, the projection vP merges with T; a probe that searches its domain for a matching goal. As a result of successive-cyclic movement, and by the time T is merged, DO ends up at [Spec,v]. Then, T probes down its domain and finds DO as an accessible goal with matching features, and hence, the DO gets its Case feature valued “Nominative” as a result of Agree with T.

On the other hand, in a thematic applicative construction, the IO is already generated in [Spec, vAPPL], thus it is the optimal candidate to be the subject in passivization. But, how can we derive a structure where the DO is passivized instead of IO? The answer to this question is to be presented in the next section where I try to tackle the issue of passivization in symmetric languages.

6.2.2. Symmetric passivization

As passivization in symmetric languages is characterized by the possibility of either of the two objects to be the subject, I will not get into details on the possibility of the higher object (i.e., IO) being the subject in passivization as that is discussed thoroughly in the last sections. Rather, I will attempt to offer a solution for the issue of passivizing the lower object (i.e., DO) in symmetric languages.

Bearing in mind that passivizing DO means the inability to get its Case valued in the usual way (cf. Citko, Citation2011). Hence, the T probe finds it a potential goal with an unvalued Case feature. This leads us to assume that vAPPL head may lose its ability to value the Case feature of DO. But I follow, in this section, the standard assumption that only v absorbs Case in passivization which suggests that IO is the optimal candidate as a subject in such construction. Therefore, for T to probe down the DO, the IO must be frozen in a place lower than vP. That is, the IO needs to get its Case feature valued as accusative first. To do so, I assume, following Haddican and Holmberg (Citation2012) as well as Citko (Citation2011), that the accusative-assigning ϕ-probe might be merged as a separate Linker head which occupies the position above vAPPL.Footnote22 These assumptions are schematized in (56) below:

In this structure, I assume that the IO has already had its Case feature valued by Lnk probe. The DO can be passivized as it does not get its Case feature valued. Therefore, it ends up as an accessible goal for the T probe, through the successive-cyclic movement I adopted in the last section above. By this scenario, we have seen how the lower argument (i.e., DO) can be passivized. On the other hand, if vAPPL retains its Case-assigning capacity, then Lnk becomes illicit for Case-valuation and vice-versa. In this case, DO gets its Case valued by establishing an Agree relation with vAPPL while IO becomes the potential goal for the T probe. In sum, the difference between symmetric and asymmetric passivization can be attributed, again, to whether the Case-assigning capacity is on the vAPPL or on the Lnk head, a parameter that characterizes which object should be passivized. To put it differently, the alternative analysis parametrizes the Case feature of [vAPPL] to account for the distinction between symmetric and asymmetric passivization. That is, if vAPPL is [- Case], Lnk must be [+ Case] and vice-versa. Similar to [± v], [vAPPL ± Case] implies the optionality of the Case value which is a characteristic of symmetric passive languages.

In fact, I found this analysis more appealing than the previous one because by positing the LnkP above vAPPLP, one can maintain the general stream in literature that only v is responsible for passive morphology. Further, this introduces an appropriate explanation for the DO passivization in symmetric languages as well as in type B of asymmetric languages.

To conclude, the two analyses above attribute the distinction between symmetric and asymmetric passivization to a parametric variation as summarized in .

7. Summary

In this paper I have proposed an analysis that accounts for the passivization of DOC in Modern Standard Arabic. The analysis is based on the recent minimalist framework of Chomsky (Citation2000, Citation2001)) which assumes an Agree relation to be established at distance. I have argued that MSA is an asymmetric passive language of type A which allows only the higher object (i.e. IO) to passivize. Though I assume that passivization in MSA is an in situ phenomenon, I tried to come up with a proposal that can accommodate the cross-linguistic passivization patterns (symmetric vs. asymmetric passivization) so that the variation across languages in passivization boils down to a parametric variation (i.e., the value of the Case feature of v) where a passivization process in a double-object language is [+ v] or [- v] which implies [- vAPPL] or [+ vAPPL], respectively.

Though the proposal mentioned seems to be appealing, it needs further scrutiny. Therefore, an alternative account is adopted to account for the symmetric vs. asymmetric passivization facts. I adopted another analysis that combines both Locality as well as Case approaches (cf. Haddican & Holmberg, Citation2012; Citko, Citation2011). By assuming a separate Linker head that occupies the position above vAPPLP, which may have a case-assigning capacity, we parametrize the Case feature on vAPPL to be either [- vAPPL] or [+ vAPPL] which consequently results in [+ Lnk] or [- Lnk], respectively. With these assumptions, the symmetric vs. asymmetric distinction can be captured cross-linguistically.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Fawwaz An-Nashef

Fawwaz An-Nashef is an assistant professor of English Linguistics and Phonetics at the English department, Faculty of Arts and humanities at Sana’a University- Sana'a, Yemen. He has been teaching various courses of linguistics for undergraduate and graduate students in different universities. His main area of interest is (Syntax) and linguistics in general. He holds a PhD in Syntax from the English and Foreign Languages University (India), an MA in Linguistics from the Central Institute of English and Foreign Languages (India), and a Bachelor degree in English education from Sana’a University.

Notes

1. For more on High and Low applicative structures see Pylkkänen (Citation2001, Pylkkänen, Citation2002/Citation2008).

2. “Closeness” in McGinnis (Citation2001) is solely defined in terms of strict c-command. So, she is doing away with the notion of equidistance and minimal domains.

3. See Jeong (Citation2007) for more discussion.

4. In Arabic the verb root is believed to be composed of bare (tri-) consonantal root, for example, the verb kataba “to write” has the root ktb.

5. Passive construction in MSA is classified into two types (inflectional and derivational). For more details on this classification, see Ryding (Citation2005).

6. Some modifications have been implemented for the sake of consistency in using symbols and diacritics that never affect the original quoted text.

7. For similar claims see, among others (Sibawayh, Citation1985; Al-Istarabadi, Citation1975; Al-Ansaari, Citation1996).

8. It should be noticed that the SV order in Arabic triggers full agreement (person, number and gender):1. VS order dhuriba T-Tullab-u beat.pass.3.s.m the-students “The students were beaten”2. SV order ʔaT-Tullab-u dhuribuu The-students beat.pass.3.p.m

9. For similar view see, for instance, Ura (Citation2000), Abu-Joudeh (Citation2005), Wright (Citation1898), and Omer et al. (Citation1984), among others.

10. The pronominal IO is cliticized on the verb; and hence, it precedes the subject. This results from the fact that in MSA, pronominal objects in DOC must cliticize on the verb.

11. In fact, this conclusion falsifies the Arab grammarians’ assumption of the existence of nominative clitic pronouns (i.e., with 1st person, 3rd person dual & plural), which I rather believe to be mere agreement inflections.

12. Even in active sentence of MSA, EPP on T is optional (cf. Saeed, Citation2011; Soltan, Citation2007; among others),

13. For more evidence and argument for the in-situ agreement in Standard Arabic, see Saeed (Citation2016) where he proposes φ- Incomplete T that values its uninterpretable features against the interpretable features of vP-internal subject at distance in VS order.

14. Citko (Citation2011) also makes a similar assumption.

15. The idea of vAPPL being able to absorb Case is still a stipulation that needs to be supported by independent evidence.

16. I am indebted to Holmberg and also McGinnis (personal communication, March, 2013) for raising this issue.

17. Luganda is a Bantu language that is considered to be an official language of Uganda.

18. This is an argument against Burzio’s Generalization (BG). In fact, BG has been challenged cross-linguistically and there are several studies that question the empirical as well as the theoretical basis of this generalization (e.g., Baker, Citation1988; Mahajan, Citation2000; Pylkkänen, Citation2002; Woolford, Citation1993, Citation1997, Citation2003; and Öztürk, Citation2006; among others)

19. [- Case] is used here to indicate that in passives the head lacks the ability to check/value the Case of the object. It is somehow similar to Anagnostopoulou’s (Citation2003) v–INTR.

20. Chomsky (Citation2000) distinguishes between two types of feature-driven movement, directly feature-driven movement (e.g raising to subject) and indirectly feature-driven movement (e.g., the non-final stages of successive-cyclic movement).

21. Note that the successive-cyclic movement starts before the final target of this movement enters the structure (Cf. Bošković, Citation2007).

22. See also Citko (Citation2011) for somewhat similar assumptions where she suggests an additional light ApplP.

References

- Abu-Joudeh, M. (2005). Multiple accusative-constructions in modern standard Arabic: A minimalist approach [Ph.D. Thesis]. University of Kansas.

- Afarli, T. (2006). Passive and argument structure. In W. Abraham & L. Leisio (Eds.), Passivization and typology: Form and function (pp. 373–25). John Benjamins.

- Al-Ansaari, J. (1996). Sharћu qatri ʔal –nada. Beirut: Daar Al- Kutub ʔal - ʕilmiya.

- Al-Istrabadi, R. (1975). Sharћ al-raDi ʕalaa al-kaafiyah. Tehran: Al-Sadiq foundation.

- Anagnostopoulou, E. (2003). The syntax of ditransitives: Evidence from clitics. Mouton de Gruyter.

- Baker, M. (1988). Incorporation: A theory of grammatical function changing. University of Chicago Press.

- Baker, M., Johnson, K., and Roberts, I. (1989) Passive arguments raised, Linguistic Inquiry 20: 219–251

- Barss, A., and Lasnik, H. (1986). A note on anaphora and double objects. Linguistic Inquiry 17, 347–354

- Bošković, Ž. (2007). On the locality and motivation of move and agree: An even more minimal theory. Linguistic Inquiry, 38(4), 589–644. https://doi.org/10.1162/ling.2007.38.4.589

- Bresnan, J., and Moshi, L. (1990). Object asymmetries in comparative Bantu syntax. Linguistic Inquiry 21, 147–185

- Broekhuis, H. (2008). Derivations and evaluations: Object shift in the Germanic languages. University of Chicago Press.

- Chomsky, N. (1981). Lectures on government and binding. Foris.

- Chomsky, N. (1995a). The minimalist program. The MIT Press.

- Chomsky, N. (1995b). Bare phrase structure. In H. Campos & P. Kempchinsky (Eds.), Evolution and revolution in linguistic theory (pp. 51–109). Georgetown University Press.

- Chomsky, N. (2000). Minimalist inquiries: The framework. In R. Martin, D. Micheals, & J. Uriagereka (Eds.), Step by step: Essays on minimalist syntax in honor of Howard Lasnik (pp. 89–156). MIT Press.

- Chomsky, N. (2001). Derivation by phase. In M. Kenstowics (Ed.), Ken Hale: A life in language (pp. 1–52). MIT Press.

- Chomsky, N. (2005). On phases. In Ms. Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Citko, B. (2011). Symmetry in syntax: Merge, move and labels. Cambridge University Press.

- Doggett, T. (2004). All things being unequal: Locality in movement [Ph.D Thesis]. MIT.

- Falk, C. (1990). On double object constructions, Working Papers in Scandinavian Syntax 46:53–100.

- Fassi Fehri, A. (1993). Issues in the structure of standard Arabic clauses and words. Kluwer Academic Press.

- Georgala, E. (2012). Applicatives in their structural and thematic function: A minimalist account of multitransitivity [ Ph.D. Thesis]. Cornell University.

- Haddican, W., & Holmberg, A. (2012). Object movement symmetries in British English dialects: Experimental evidence for a mixed case/locality approach. The Journal of Comparative Germanic Linguistics, 15(3), 189–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10828-012-9051-x

- Haegman, L. (1991). Introduction to government and binding theory. Blackwell.

- Hartman, J. (2012). (Non-) intervention in A-movement: Some cross-constructional and crosslinguistic considerations. Linguistic Variation, 11, 121–148. https://doi.org/10.1075/lv.11.2.01har

- Jaeggli, O. (1986). Passive. Linguistic Inquiry, 17, 587–622

- Jeong, Y. (2007). Applicatives: Structure and interpretation from A minimalist perspective. Benjamins.

- Kayne, R. (1983). Connectedness. Linguistic Inquiry, 14, 223–249. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4178324

- Larson, R. (1988). On the double object construction. Linguistic Inquiry, 19(3), 335–391. doi: 10.2307/25164901

- Lee, J. –. E. (2004). Ditransitive structures and (anti-)locality [PhD Thesis]. Harvard University.

- Legate, J. (2003). Some interface properties of the phase. Linguistic Inquiry, 34, 505–516 3. doi:10.1162/ling.2003.34.3.506

- Li, A. (1990). Order and constituent in Mandarin Chinese. Kluwer.

- Maalej, Z. (1999). Passives in modern standard and Tunisian Arabic. Matériaux Arabes et Sudarabiques-Gellas, 9, 51–76.

- Mahajan, A. (2000). Oblique subjects and Burzio’s generalization. In E. Reuland (Ed.), Arguments and case: Explaining Burzio’s generalization (pp. 79–102). John Benjamins.

- Malhotra, S. (2011). Movement and intervention effects: Evidence from Hindi/Urdu [Ph.D Thesis]. University of Maryland.

- Marantz, A. (1993). Implications of asymmetries in double object constructions. In Sam A. M. (Ed.), Theoretical aspects of Bantu grammar 1, 113–151. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publication.

- McGinnis, M. (1998). Locality in A-movement [PhD Thesis]. MIT.

- McGinnis, M. (2001). Variation in the phase structure of applicatives. Linguistic Variation Yearbook, 1, 105–146. https://doi.org/10.1075/livy.1.06mcg

- McGinnis, M. (2004). Lethal ambiguity. Linguistic Inquiry, 35(1), 47–95. https://doi.org/10.1162/002438904322793347

- Öztürk, B. (2006). Case, EPP and passivization in Turkish. In W. Abraham & L. Leisio (Eds.), Passivization and typology: Form and function (pp. 383–402). John Benjamins.

- Omer, A., Al-nahhas, M., Mohammed, Z., & Abdullatif, H. (1984). An-naħu al-asasi. That As-Salasil.

- Pak, M. (2008). A-movement and intervention effects in Luganda. In Proceedings of the 27th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics, 361–369.

- Pesetsky, D. (1995). Zero syntax: Experiencers and cascades. The MIT Press.

- Pylkkänen, L. (2001). What applicative heads apply to. In M. Fox, A. Williams & E. Kaiser (Eds.), Proceedings of the 24th Annual Penn Linguistics Colloquium. Penn Working Papers in Linguistics, 7.1. University of Pennsylvania.

- Pylkkänen, L. (2002). Introducing arguments [PhD Thesis]. MIT.

- Pylkkänen, L. (2008). Introducing arguments. MIT Press.

- Richards, M. (2012). On feature inheritance, defective phases, and the movement-morphology connection. In A. Gallego (Ed.), Phases: Developing the framework (pp. 195–232). Mouton de Gruyter.

- Ryding, K. (2005). A reference grammar of modern standard. In Arabic. Cambridge University Press.

- Saeed, F. (2011). The syntax of verbal agreement in minimalism: Formal feature valuation in English and standard Arabic [Ph.D Thesis]. EFL University.

- Saeed, F. (2016). On move and agree: evidence for in-situ agreement. http://www.phil.muni.cz/linguistica/art/saeed/sae-001.pdf

- Sibawayh, A. (1985). (8th century). Al-kitaab.1938. Cairo: Bulaaq.

- Sigurðsson, H., & Holmberg, A. (2008). Icelandic dative intervention: Person and number are separate probes. In R. D’Alessandro (Ed.), Agreement restrictions (pp. 251–279). Mouton de Gruyter.

- Soltan, U. (2007). On formal feature licensing in minimalism: Aspects of standard Arabic morphosyntax [PhD thesis]. University of Maryland.

- Ssekiryango, J. (2006). Observations on double object construction in Luganda. In A. Arasanyin & Pemberton, M. (Eds.), Selected Proceedings of the 36th Annual Conference on African Linguistics (pp. 66–74). Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

- Swan, O. (2002). A grammar of contemporary Polish. Slavica Publisher.

- Ura, H. (1996). Multiple feature-checking: A theory of grammatical function splitting [PhD Thesis]. MIT.

- Ura, H. (2000). Checking theory and grammatical functions in universal grammar. Oxford University Press.

- Woolford, E. (1993). Symmetric and asymmetric passives. In Natural language and linguistic theory, 11 (pp. 679–728).

- Woolford, E. (1997). Four-way case systems: ergative, nominative, objective and accusative. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 15, 181–227 1. doi:10.1023/A:1005796113097

- Woolford, E. (2003). Burzio’s generalization and markedness. In E. Brandner & H. Zinsmeister (Eds.), New perspectives on case theory (pp. 301–330). Standford, CA: CSLI.

- Wright. (1898). A grammar of the Arabic language. Cambridge University Press.