?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This paper aims to examine the influence of the spirit of a place on the space durability. Specifically, we consider the hypothesis that respecting the concepts of psychological and behavioral elements of a place would make the urban textures more durable. We investigate this hypothesis by performing a thorough qualitative and quantitative study. We start by studying the concept of durability and its critical role in relation to urban texture. We next examine the relationship between the spirit of a place and its durability from a phenomenological point of view. We also perform a comprehensive descriptive analysis of the existing literature to support the claimed hypothesis. We corroborate this claim by a statistical survey of the population of the Julfa neighborhood of Isfahan, Iran, followed by a quantitative analysis of the collected data.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

In an effort to enhance the urban contexts to be more durable, this research has focused on demonstrating the impact of place attachment on the durability and stability of the place. Most people experience feelings of place attachment which go beyond the usefulness of a particular place and relate to their rootedness and memories. Thus, the willingness to replacement is strongly influenced by the attachment a person may have to a specific site or resources such as a neighborhood. This study, through a qualitative and quantitative study, shows that respecting the concepts of psychological and behavioral elements of the place would make the urban textures more durable.

1. Introduction

Old urban textures undoubtedly enjoy a unique authenticity and character. Their true essence and spiritual power can be felt once put in the place but are hard to convey in words. Unfortunately, the literature lacks a thorough and comprehensive analysis of such textures. Discovering the essential quality of such spaces has a fundamental importance, because they can be used as patterns to enhance the quality of life and increase the durability of our built environment. Our mission as architects is to preserve old textures by respecting such perceptual elements and spiritual beliefs which are deeply rooted in all cultures as moral codes.

In this paper, we aim at studying the influence of the spirit of a place on the space durability. To carry out the research, we first do a thorough literature review on the concepts of durability and sense of place and discuss several perspectives proposed by psychologists, artists and philosophers. We then formulate a hypothesis on the effect of sense of place on texture durability.

The questions of interest, hypotheses and the objectives of our study are listed below.

Questions: (1) Are the concept of spirit of a place and the associated factors capable of preserving old urban textures? (2) Is the durability of old urban textures rooted in human psychology/behavior?

Hypothesis: Respecting human psychological-behavioral dimensions has the potential of making residential urban textures more durable.

Objective: Enlivening places and making built environment durable by recreating concepts related to the characteristics of the space.

We conduct a field research (survey research) and perform a statistical analysis of the collected data to test our hypothesis.

2. Materials and methods

The methodologies carried out in this study are both qualitative and quantitative. We study the related literature from a descriptive-theoretical lens, and we also conduct a statistical survey along with an analysis of the collected data to quantitatively support our claim. Specifically, we choose a population of size 95 from the Julfa Neighbourhood, an old community in Esfahan, Iran and ask them several multiple-choice questions each indirectly concerning the durability or the sense of the place. We then consider pairs of questions, one on durability and one on the spirit of the space and form contingency tables for the responses. We then run the Pearson’s chi-squared test and the Fisher’s exact test on the contingency tables using SPSS software and compute the corresponding p-values for testing the correlation between the two categorical variables, durability and the spirit of the space. Based on the reported p-values we reject the null hypothesis that there is no relation between durability and the spirit of the space.

We next discuss the thoughts behind the items in the questionnaire and the choice of the subpopulation for our study. Attachment to a place (or resource) has at least two general origins: (i) Resource dependence or functional attachment, which refers to the importance of the resource for pursuing a particular activity; (ii) Resource identity which refers to the degree of emotional or symbolic meaning assigned to a place (Williams & Roggenbuck, Citation1989). In other words, the extent to which a visitor’s identity is tied to the place.

In designing our questionnaire, we tried to be holistic by including items which capture both of these deriving factors for place attachment. We consulted the literature of environmental psychology regarding place attachment (Proshansky et al., Citation1983) place as well as work on leisure behavior regarding activity involvement (Buchanan, Citation1985; Wellman et al., Citation1982), along with a set of interviews provided by (Hay, Citation1998) regarding the notion of sense of place. In addition, the items were reviewed and edited by three independent researchers (other than the authors).

As Hay (Citation1998) argues (i) residential status in the place (superficial, partial, personal, ancestral, and cultural senses of place); (ii) age stage (as the sense of place is developed across the life cycle), and (iii) adult pair bond relationship (often through marriage) are among the most relevant factors to the development of sense of place. He further supports his claims by conducting several quantitative studies. Using this result, in our field study we interview a wide spectrum of people. The chosen subpopulation of the Julfa neighborhood encompasses different age groups, from both single and married populations as well as mobile to more rooted residents.

In Sections 3.2 and 3.3 we discuss different viewpoints on the concept of durability and durability of urban textures. In our work, we consider place durability as the quality of a place for their tenants to live there for a long time despite varying ecosystems. Its residents would have a tendency to stay in that place and are bonded to the events, architecture and other residents. As such we often observe ancestral connections to durable places in which several generations of a family have lived in the same area. By this definition of durability, in our questionnaire we included Q6, Q7, Q8 that concern the durability of the Julfa neighborhood.

We conclude the methodology section by providing some information about the Julfa neighborhood. Julfa is the Armenian quarter of Esfahan, Iran, and is located along the south bank of the Zayandeh River. It is named after the older city of Julfa (Jugha), Nakhichavan in the early seventeenth century, by the edict of Shah Abbas from the Safavid dynasty, and over 150,000 Armenians were moved there from the older Julfa (also known as Jugha or Jula) in Nakhichavan. It is still one of the oldest and largest Armenian quarters in the world. Julfa is still an Armenian-populated area with an Armenian school and 16 churches, including the Holy Savior Cathedral. Armenians in the Julfa neighborhood observe Iranian law with regard to clothing, but retain a distinct Armenian language, identity, cuisine, and culture which is protected by the Iranian government (Tahbaz, Citation2003, Citation2004). A map of Julfa neighborhood is provided in .

3. Literature review

3.1. Sense of place and place attachment

By history, the concepts of place attachment and sense of place were interesting subjects for scholars from (Eliade, Citation1959) to recent generations of researchers with a specific attention to environmental behavior issues (Algouneh Jouneghani, Citation2019; Belk, Citation1988; Jackson, Citation1981; Kohák, Citation1984; Pocock et al., Citation1994; Seamon, Citation1982). The older literature was mainly focused on specific emotional experiences between people and places, and symbolic meaning assigned to a place. As such this literature fell short in gaining the attention of environmental researchers and architects since they were mostly focused on individual subjective experiences within ethical, aesthetic and historical contexts. In recent years, researchers from various fields such as social psychology, geography, anthropology and architecture started to pay attention to broader cross-cultural issues, effect of migration, as well as subjective quality of individual’s sense of place, feeling of dwelling, and aesthetic characteristics of a place. Therefore, the phenomenological view found a more central role between researchers and scholars (Low & Altman, Citation1992; Peterson et al., Citation1985).

As Hay (Citation1998) believes, three contexts are used to examine the development of sense of place in individuals:

Residential status (superficial, partial, personal, ancestral and cultural sense of place)

Age stage

Development of adult pair bond specifically marriage

Based on his research the development of sense of place is specifically affected by residential status. Those with superficial attachments to place such as tourists do not experience a sense of place as strongly as insiders who lived there for most of their lifetime so they experience rootedness and spiritual ties to the place. Also based on his findings, if someone has been spent most of his or her life time in one place; then, we can say that this person developed the sense of place by age stage. He found that his respondents moved through a series of life cycle stages in their lives. The sense of stability and belonging to the place were increased among those who had lived there for a long time or even has been raised there. The adult pair bond (in particular via marriage) cycle proved helpful in understanding the development of sense of place. Similar to the feelings of security, belonging and stability, that arise from a fully developed pair bond, a sense of place can also provide similar feelings. He argues that social interactions are helpful to the maintenance of both the sense of place and the pair bond. In summary, the development of sense of place resembles the development of personal maturity (life cycle) and of mature pair bonds (marriage cycle).

3.2. Concept of durability

We start by discussing how the term “durability” is perceived in different parlances. The Webster Dictionary (Merriam-Webster, Citation2000) defines “durability” as “the ability to exist for a long time without significant deterioration”.Footnote1 Therefore, durability,Footnote2 the word per se dominates meanings such as changelessness, permanence and sustainability.Footnote3

The Plato believes that genuineness and authenticity of a place is one of the key measures of space exquisiteness and durability. In Plato’s viewpoint, traditionalists are people who reveal their loyalty towards authenticityFootnote4 (Markiewicz, Citation2015). In other words, conformity with tradition is necessary for authenticity and ensuring a durable elegance.

It is worth noting that what perpetuates the elegance of a phenomenon is its conformity with concepts and meanings. For example, if symbolic meanings are attached to formal beauty, that beauty will last more. The key point, however, is that these symbolic concepts must be recognizable for the public and of course deeply rooted in traditional beliefs. No one can create symbols for people.Footnote5 History supports this thesis as the most influential and eminent architects are those who have created architectural beauty based on generally accepted symbols (Tahbaz, Citation2003, Citation2004).

Psychologists pose the concept of general understandability of simple forms, under the name of “universal symbols”, and believe that certain geometric forms such as square and circle have common meanings among all people. These meanings are everlasting and have been repeated over and over again in the course of history of art and architecture (Lang, Citation1987). Closely related, Jung determines the space durability by relying on the concepts of collective unconsciousness and archetypes. In Jung’s opinion, collective unconscious encompasses common myths shared among human beings including mental images with a universal meaning, and durable spaces are rooted in such mental images.

Behaviorists like Bryan Lawson and Jennifer Cross emphasize on individuals’ experiences and behaviors, and opine that the existing relationship between form and function in the urban textures has been created continuously over time to revive a symbolic language in relation to a form-function interplay. Referring to cultural and ecological issues, Gibson believes that social conventions and beliefs play a major role in appreciating symbols and, accordingly, in making environments durable. Sociologist, Norbert Wiener, claims that the symbolic interpretation which people extract from their surrounding area relies on their own psychological, social and physiological characteristics, and hence leveraging them brings durable aesthetic sense to the place (Lang, Citation1987).

3.3. Durability of urban textures

We continue our discussion on durability by a quote from Pallasmaa (Pallasmaa, Citation1987): “architecture makes things durable and admirable. Therefore, where there is nothing to be made durable, architecture cannot be created as well.” As Trancik states old urban textures are human-environmental entities with a durable character representing the history, geography and the spirit of the society (Trancik, Citation1986). According to Trancik’s perspective, durability requires the place to keep its identity and coherenceFootnote6 inclusion of the historical, geographical and spiritual components.

Traditionalism, however, dictates that the mission of art is nothing less than the evolution of human consciousness. Art should have a persistent impression on people, rather than seeking temporary work which ceases to benefit humans as soon as their contact with art is interrupted (Naghizadeh & Aminzadeh, Citation2003). By the same token, the reason for durability as well as popularity of our old urban textures is that such textures enjoy certain qualities, specific patterns and orderly complexities in their structure and behavior.

Alireza Ghahari believes that when the local people abandon worn out urban textures, the socio-cultural structures of such textures begin to deteriorate, and therefore the urban planners should pay a close attention to the built environment from a humanistic stance. Ghahrai argues that in order to preserve and enliven the texture, native dwellers are the best conservators of their neighborhoods; the presence of local dwellers keeps the spirit of the place alive and durable. To put it differently, there is an intimate interaction between the durability of texture and the emotive attitudes of dwellers towards their neighborhood. As John Ruskin phrases in The Lamp of Memory book: “Indeed the greatest glory of a building is not in precious stones used in it but of its durability and the events witnessed by that space (Capon, Citation1999).”

It is clear that urban texture is not an unchangeable entity. The city transforms in the course of time, but at the same time, texture keeps its main characteristics. Of course, respecting the pivotal attributes does not mean an intact repetition of them; rather, it implies a continual interpretation of them. As Schultz (Schulz, Citation1980) says, from a phenomenological point of view, durability and identity of an urban texture have been interwoven with each other; the more identity values a texture has, the more durable it is. In simple terms, durability of an urban texture has structural and behavioral values and is therefore considered as a pivotal index in urban planning. A durable place is the result of an accurate and creative space planning.

Durability comes after the beauty because durability at its core refers to recreation of the values, which is indeed how the beauty is defined in Traditionalism. According to Peter Smith (Smith, Citation1987), the durability of a space depends on the scope of its beauty and exquisiteness that pervades human’s spirit. The depth of this mental impression may be defined at three distinct levels: superficial (fashion), intermediate (style) and deep (eternal). Similarly, what makes a space durable from an Islamic point of view is the fast transition from emotive beauty to reasonable beauty. Reasonable beauty is, by nature, a sacred symbolic beauty with ability to penetrate into the innermost layers of human spirit (Jafari, Citation1999). This religious view directs to the non-emotive nature of aesthetic concepts and their relation with the durability of textures.

Regarding the longevity of the beauty of a place, Félicien Challaye, the French empiricist philosopher believes that the more human senses and minds are satisfied (and have a stronger interaction), the more the beauty is lasting (Tahbaz, Citation2003, Citation2004). Urban texture has a long-term use for generations, and hence its aesthetic values have deep human psychological roots. It is only through their psychological roots that urban textures can express originality and immortality. Basically, durability implies a historical continuum and, in consequence, a cultural continuum. A durable phenomenon is a progressed phenomenon and given that despite all the surrounding changes it has managed to survive, it therefore serves as a touchstone in analyses and studies. When we talk about the spirit of a place, it means that the place has a powerful attraction and is immensely impactful.

In summary, an urban texture, like any other live organism, has a spirit and the durability of that texture (organism) is dependent upon its spirit. In what follows, we address the concept of spirit of the place from a semantic point of view to have a better understanding of the discussion. We then discuss the relation between the space durability and the spirit of the space from both a qualitative study of the literature and a quantitative analysis of survey data collected from the Julfa neighborhood in Isfahan, Iran.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Spirit of a place: a semantic study

Generally, there are two basic approaches to defining “sense of a place”: Phenomenological and Psychological. In a phenomenological approach, the sense of a place deals with the non-materialist characteristics of the place, and is conceptually close to the spirit of the place. Christian Norberg Schulz, Yi Fu Tuan, Edward Relph, Kenneth Frampton, Christopher Alexander and David Seamon are among the theorists who have a phenomenological view towards the place. Schulz defines the place as a conceived space interwoven with memories, experiences and psychological states. For him, the place is a space to dwell (Schulz, Citation1980). In his book, Place and Placelessness, Edward Relph states that the main meaning of the place identity does not arise from physical and superficial experiences of its inhabitants or the circumstances in which they are engaged; instead, it comes from the vital characteristics or in other words, the authenticity of the place (Salvesen, Citation2002). People often experience features beyond the physical characteristics of a place and can continuously feel themselves in contact with the spirit of the place. To clarify, places are inherently semantic bases formed by several events in the course of time. In Relph’s view, places are combinations of spaces with memories and events and the sense of place is defined in continuity with the past (Habibi, Citation1999).

As mentioned earlier, the structure of a place is not immutable. This, however, does not mean that people’s affection for the spirit of the place is changing or vanishing in a given urban texture. Durable places which have sustained for a long time, had the necessary conditions for living in and preserved their originality (Schulz, Citation1980). In this point of view, humans need an emotional and spiritual experience towards their living environment. In fact, the spirit of a place serves as a catalyst which transforms an environment into a place (Falahat, Citation2006). As Falamaki states in (Falamaki, Citation2004), Iranians from ancient times had a psychological attitude towards the formation process of spatial structures in urban zones. Falamaki undertakes a psychological point of view and sees the sense of place as unification of structural relationships of neighborhoods based on recognition of the spatial behaviors of the inhabitants (Falamaki, Citation2004).

Environmental psychologists believe that strengthening emotional connections with the place plays an essential role in overcoming the identity crisis of the present world and its authentication. It gives a sense of permanence and immortality to individuals in this ever-changing world (Hay, Citation1998). Environmental psychologists have studied the emotional interaction between human and place under the name “sense of place” in order to enhance the sense of belonging, attachment to space, security, identity and authenticity in humans, which overall yields a sense of satisfaction from the residence. The collection of stories and individual narratives, which are associated with the place, contributes to the creation of the sense of social attachment to place (Habibi, Citation1999). This sense somewhat links individuals to the place as they consider themselves part of the place and based on their experience of signs, meanings and functions, they imagine a role for the space in their mind. This role is unique and distinct for them and as a result, the place gets a character and becomes respectful. A place forms the feeling of its belongings and attachments because of the possibility of a social relationship and shared experience among individuals (Pakzad, Citation2009). As social psychologists believe, social events are more effective in creating sense of attachment to a place than the physical qualities of that area.

Architects as creators of places and environments have a crucial role in forming the sense of place. Their designs should be cognizant of the culture and spirit of the neighborhood and should actively seek to contribute to it by considering special spaces, signatures, monuments and figures that bolster the sense of place. As we discuss in this paper, this will in turn have a positive effect on space durability.

4.2. Theoretical foundations of research

Based on what was said, we believe that one of the factors which has an effective role in enhancing the space quality is leveraging analogies, comparisons and metaphors, which are deep-rooted in every nation’s beliefs. In fact, such concepts are enriching living environments and making them durable. By creating symbolic concepts in urban spaces, the structure of urban textures will be further consolidated. In other words, the more psychological and spiritual needs of people are considered and the more the spaces are humanized to achieve reasonable (and not emotive) beauty, the more durable aesthetic values are represented.

Environmental psychologists believe that strengthening the emotive associations with places plays a major role in overcoming the identity crisis of the present century and also in endowing places with authenticity. This also creates a sense of stability for people in the present ever-changing world (Hay, Citation1998). According to Daneshpour et. al. (Daneshpour A., Citation2009) there are basically three interactive factors between humans and their environment: cognitive, emotive and behavioral. The present study believes that physical and conceptual characteristics of a place are capable of influencing these interactive factors and in defining and forming the psychological sense of urban textures.

Traditional urban planning suggests that the synergy among urban texture, people’s attitudes, and their feelings, as well as psychological characteristics, makes a place more beautiful and durable. Therefore, the more a place is imbued with psychological and behavioral concepts such as sense of place and the feeling of attachment, the more beautiful and consequently, the more durable that place will be. That said, historical monuments are among the unique features of every texture. As previous experiences have shown the oral history of the place, memories, events, historical moments, along with monuments, sculptures, architectural styles, transcripts or even appellations can be effective in durability of the place.

The relation of urban texture, which is a combination of architectural spaces, with the place in which it crystallizes is the same as a relation that a human being has with his conventions, memories, affiliations and in fact with his own culture. Urban textures that overlook the collective memories, traditions and conventions and do not value them properly are ephemeral. A wandering mind can only create aimless textures without any deep character, in the form of impermanent styles.

4.3. Evaluation and analytical analysis

We next carry out a quantitative investigation of the hypothesis that posits a connection between durability and the sense of a place. To this end, we have prepared a survey consisting of 14 multiple-choice questions, 3 of which directly concern the durability of the neighborhood (Q6, Q7, Q8) and the other 11 questions examine the sense of place. For this survey we chose a population of size 95 from the Julfa neighborhood. The population contains different age groups, residential status and marital status.

After collecting the responses, we formed the contingency table for pairs of these questions, and performed the Pearson’s chi-squared test on each of these contingency tables to test if the two categorical variables (durability and sense of a place) are correlated and to report the statistical significance (p-value) for such relation. Our analysis shows that 29 of these contingency tables indicate a statistically significant relation between durability and sense of the place, that is to say the calculated p-values from the Pearson’s chi-squared test are below the significant level 0.1.

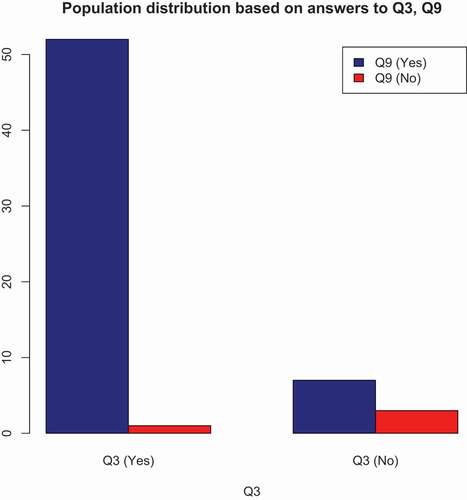

In the following, we explain the details and the analysis for one of these pairs of questions, namely questions 2 and 9. The complete set of questions along with the frequency tables of the responses are provided in Appendix. Before proceeding, let us formally define our null and alternative hypotheses. Our null hypothesis states that there is no relation between durability and sense of place, and the alternative hypothesis claims the opposite. To showcase our analysis, we consider questions 3 and 9 of the survey as examples. Q3: “Is there any entertainment/gathering center where you go frequently?” and Q9: “Is there any cultural/historical event which takes place here periodically?”. Question 3 is implicitly asking about the sense of place (through resource dependence), while question 9 is about durability. is the corresponding contingency table for Q3 and Q9.

Table 1. Contingency table for the two survey questions (Q3, Q9). Q3: “Is there any entertainment/gathering center where you go frequently?”, Q9: “Is there any cultural/historical event which takes place here periodically?”. Q3 is implicitly asking about the sense of place (via resource dependence), while Q9 is about the durability of the place. Note that although the population size is 95, only 63 of them provided valid responses to both questions Q3 and Q9

reports frequencies of different responses to each item of the questionnaire. summarizes the statistical analysis performed by the SPSS software. As reported in , the corresponding p-value for the Pearson Chi-Square is and the exact significance from the Fisher’s test is

, which are both below the predetermined significance level

, and hence the null hypothesis is rejected. In other words, the alternative hypothesis claiming a connection between durability and spirit of place) is accepted.

Table 2. Statistical analysis of the hypothesis (relation of the two variables “durability” and “sense of place” in SPSS) (a) Chi-Square Tests (b) Symmetric Measures

Table 3. Frequency tables for the valid responses to the questionnaire. Column “percentage” reports the percentage of the corresponding response in the total population of size 95

The diagram in shows the counts in the corresponding contingency table. As reported, 59 participants (93.7% of the valid population) were aware of regular cultural/historical events in the neighborhood. This subpopulation not only (unconsciously) believed in the durability of texture, but also stated that their neighborhood had a historical focal point, a gathering center where the spirit of the place is flowing. In short, a large percentage of the Julfa neighborhood residents who are emotionally attached to their neighborhood considers it memorable. They have a feeling of attachment to it and believe in the spirit of place and the durability of the urban texture.

5. Conclusion

In this paper we investigate the hypothesis that sense of place has a considerable effect on place durability. Our qualitative study gathers different viewpoints on the notions of spirit of a place, place attachment and place durability from prominent architects, philosophers, psychologists and behaviorists. By discussing these perspectives we conclude that these two notions are side by side and can indeed enhance the development of each other. We also conduct a quantitative study where we survey a subpopulation of the Julfa neighborhood in Isfahan to learn about their connections to the neighborhood, their social interactions and also the extent of their feeling of dwelling. Our survey analysis indicates a statistically significant relation between durability and sense of place. We further provide the corresponding -values for this hypothesis from the Pearson’s chi-squared test and the Fisher’s exact test. We believe that our research is of broad interest to architects and is illuminating in providing more effective revitalization of urban textures. Researching sense of place by interviewing a variety of residents in their places allows for a direct evaluation of their views and ties to the place. Studying a diverse population (young/aged, resident/out-migrant, and insider/outsider) would provide us with a holistic understanding of the needs, both functional and spiritual, and lead to a more effective strategy for revitalization of historical urban textures.

In summing up this research, we conclude that today's identity crisis in urban contexts, and consequently the loss of sense of places, stem from overlooking the architectural values. As if, instead of finding our divine identity, we are trying to fabricate identity for ourselves. The ethics of architectural practice promote seeking for unity rather than plurality and taking the empathy of people in forming spaces. People are in general more moderate and patient than urban planners and authorities. They think more pragmatically and resist against impetuous plans as much as they do against strict regulations. Clearly, the durability of urban textures heavily relies on respecting inhabitants' needs, feelings and traditional events.

Revitalization of the spirit of the place in urban textures does not mean a return to the old traditions, but rather requires expression of courage, stimulating the audience and persuading representatives to face the challenges regarding sustainable developments, preservation and protection of human society, within the context and capabilities of cultural, physical and environmental resources.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Shaghayegh Amirshaghaghi

Shaghayegh Amirshaghaghi is a Los Angeles-based architect and interior designer. She received her Master’s degree in architecture from California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, jointly offered by the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), the USA in 2018. She also holds a Master’s degree in urban heritage and a Bachelor’s degree in historical architecture, both from the Art University of Isfahan. Her research is broadly on historical architecture, with a focus on Iran's heritage.

Email: [email protected]

Shahriar Nasekhian, Ph.D. is an assistant professor of architecture in the department of conservation and restoration at the Art University of Isfahan. He received his PhD from the Art University of Isfahan. He has expertise in historical architecture in Iran with a focus on rehabilitation of historical sites and monuments. He has also served as the chair of the department.

Email: [email protected]

Notes

1. International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) defines durability as “increasing the life span of old textures and helping with conveying the historical, cultural and social messages without the authenticity and identity of the textures being endangered.” In fact, durability is a process encompassing all necessary operations to preserve the cultural heritage. Put differently, durability is a kind of transforming with the aim of preserving the placed and its soul. Also, in Burra Charter, durability has been defined as “all the needed protective processes for a given place to maintain its cultural, historical and emotive status” (Jokilehto, Citation2007).

2. According to Lynch: Durability is the extent to which a city’s constituents are able to resist against erosive factors and can survive during a long time (Pakzad, Citation2009).

3. Sustainability denotes, from one hand, the durability of a place and, from the other hand, implies an ecological concept. To the residents of a place, sustainability means the potential to promote the long-term welfare environmentally, economically as well as socially (from Wikipedia encyclopaedia).

4. The Plato perceives the term loyal representation of an entity as transferring the impressive content of that entity. Beauty is manifested, he believes, when the space or place remains loyal to the user (Motlagh, Citation2009).

5. (Razjooyan, Citation1999) believes that symbol should not be created objectively, since symbol is intrinsically as natural as breathing; it represents itself unconsciously.

6. Schultz, from a phenomenological point of view, states that identity creation or familiarization with a given environment is the foundation of human beings’ emotive attachment to a place. In fact, identity creation is the characteristics developed during childhood (Schulz, Citation1980). Seen from the angle of mind philosophy, this identity creation is recognized as physicalism and identity in this theory is essentially existentialistic not conceptual (Guttenplan, Citation1994).

References

- Algouneh Jouneghani, M. (2019). A critical analysis of eliade’s distinction between the sacred and the profane. Literary Theory and Criticism, 4(1), 5–14. https://www.sid.ir/en/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?id=819623

- Belk, R. W. (1988). Possessions and the extended self. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(2), 139–168. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/209154

- Buchanan, T. (1985). Commitment and leisure behavior: A theoretical perspective. Leisure Sciences, 7(4), 401–420. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01490408509512133

- Capon, D. S. (1999). Architectural theory (pp. 9). John Wiley.

- Daneshpour, A., & Sepehri Moghadam, M., Charkhchian, M. (2009). Explanation “place attachment” and investigation of its effective factors. Honar-Ha-Ye-Ziba, vol 1, no 38, 37–48.

- Eliade, M. (1959). The sacred and the profane: The nature of religion (Vol. 81, pp. 5). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Falahat, M. S. (2006). Concept of sense of place and its constituents. Journal of Fine Arts, 26, 57–66

- Falamaki, M. M. (2004). An overview of the experiences of urban repairing, from venice to shiraz . Faza publication.

- Guttenplan, S. (1994). A companion to the philosophy of mind. Blackwell.

- Habibi, M. (1999). Urban space, life events and collective memories. Soffe Journal, No. 28, pp. 16–21.

- Hay, R. (1998). Sense of place in developmental context. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 18(1), 5–29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1006/jevp.1997.0060

- Jackson, P. (1981). Phenomenology and Social Geography. Area 13(4), 299–305.

- Jafari, M. T. (1999). Beauty and art from Islam perspective. Daftar-e Nashr-e Farhang-e Islami.

- Jokilehto, J. (2007). History of architectural conservation. Routledge.

- Kohák, S. D. (1984). Personality and field-specific abilities of actors [ Ph.D. Thesis]. Boston University.

- Lang, J. (1987). Creating architectural theory. The Role of the Behavioral Sciences in Environmental. Design. ISBN: 0442259816.

- Low, S. M., & Altman, I. (1992). Place attachment. In Place attachment (pp. 1–12). Springer. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-1-4684-8753-4#editorsandaffiliations https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4684-8753-

- Markiewicz, C. A. (2015). The crisis of rule in late medieval Islam: A study of Idr¯ısBidl¯ıs¯ı (861-926/1457-1520) and kingship at the turn of the sixteenth century [ PhD thesis]. The University of Chicago.

- Merriam-Webster, I. (2000). Merriam-webster’s collegiate encyclopedia . Library of Congress Cataloging.

- Motlagh, S. B. (2009). The beauty and philosophy of art in conversation: Plato (Vol. 6,). Academy of Art (Farhangestan Honar).

- Naghizadeh, M., & Aminzadeh, B. (2003). Concept and degrees of qualitative space. KHIAL: Journal of Academy of Arts, 8, 98–119.

- Pakzad, J. (2009). An intellectual history of urbanism-From space to place. The New Town Development Publication, Volume V.

- Pallasmaa, J. (1987). The social commission and the autonomous architect-the art of architecture in the consumer society. HARVARD ARCHITECTURE REVIEW, 6, 115–121. http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/888309554

- Peterson, G. L., Stynes, D. J., Rosenthal, D. H., & Dwyer, J. F. (1985). Substitution in recreation choice behavior. In G. H. Stankey & S. F. McCool, compilers. Proceedings–symposium on recreation choice behavior; 1984 March 22-23; Missoula, MT. General Technical Report INT-184. Ogden, UT: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station. p. 19–30, 184.

- Pocock, D., Relph, E., & Tuan, Y.-F. (1994). Classics in human geography revisited: Tuan, y.-f. 1974: Topophilia. Prentice-hall. Progress in human geography, 18( 3):355–359.

- Proshansky, H. M., Fabian, A. K., & Kaminoff, R. (1983). Place-identity: Physical world socialization of the self. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 3(1), 57–83. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(83)80021-8

- Razjooyan, M. (1999). Symbol from Young’s perspective. SOFFEH Journal, Vol. 28, pp. 29–32.

- Salvesen, D. (2002). The making of place. Urban Land, 61(7), 36–41.

- Schulz, C. N. (1980). Genius loci: Towards a phenomenology of architecture. Academy Editions. ISBN: 0847802876.

- Seamon, D. (1982). The phenomenological contribution to environmental psychology. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 2(2), 119–140. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(82)80044-3

- Smith, P. F. (1987). Architecture and the principle of harmony. Intl Specialized Book Services.

- Tahbaz, M. (2003). Beauty in architecture. SOFFEH Journal, 13(37), 75–97. https://soffeh.sbu.ac.ir/article_99981.html

- Tahbaz, M. (2004). The sacred form. SOFFEH Journal, 14(38), 95–124. https://soffeh.sbu.ac.ir/article_99967.html

- Trancik, R. (1986). Finding lost space: Theories of urban design . John Wiley & Sons.

- Wellman, J. D., Roggenbuck, J. W., & Smith, A. C. (1982). Recreation specialization and norms of depreciative behavior among canoeists. Journal of Leisure Research, 14(4), 323–340. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.1982.11969529

- Williams, D. R., & Roggenbuck, J. W. (1989). Measuring place attachment: Some preliminary results. In NRPA Symposium on Leisure Research, San Antonio, TX, 9.

Appendix A

Statistical survey and the collected data

In this appendix, we provide our questionnaire that was used for our statistical study. This survey was conducted on a population of size 95 from the historic Julfa neighborhood, located in the city of Esfahan, Iran. We also provide the corresponding frequency tables for each of the questions in this survey.

Questionnaire

Resource dependence:

Q1: Is your working place close to here?

Q2: If you are provided with a quite similar home (same conditions) in other neighborhoods, do you accept to move?

Q3: Is there any entertainment/gathering center where you go frequently?

Q4: Do you spend most of your free time in the neighborhood?

Q5: Do you or your family own a property here?

Q6: Are you motivated to stay in Julfa neighborhood?

Q7: Do you like the historical texture here or prefer a modernized version of the neighborhood?

Resource identity:

Q8:. Do you have ancestors in this neighborhood?

Q9: Is there any cultural/historical event which takes place here periodically?

Q10: Do you know your neighbors and the community?

Q11: Do you feel safe and secure here?

Q12: How long have you been living in this neighborhood?

Q13: Are you living here because of your parents or marriage?

Q14: Are you part of the Armenian community of the Julfa?