Abstract

The article discusses the poster as a form of visual message used for agitation propaganda mainly during world wars. Hence, the introductory part covers both the visual layer, verbal communication, and non-verbal communication as well as aspects of political communication used in agitation propaganda. The authors took into account propaganda posters using the pointing finger motif, the prototype of which was the poster by Alfred Leete from 1914. The image of Lord Kitchener and a hand with a pointing finger stretched out towards the recipient of the message, as well as the exclamation “Your country needs you” became an inspiration for subsequent posters that influence exceed time and geographical space. The analysis of posters with the pointing finger motif was carried out taking into account four periods. The authors also drew attention to the media space that was the original one for the 1914 poster. A space without media known today, where, on the one hand, the poster made it possible to reach a wide audience, and on the other, its impact was a product of the strength of the messages it contained and the means used. The analysis was carried out based on the methodology of interpretation of visual materials by Gillian Rose.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The article deals with the subject of the poster as a form of visual message used in the service of agitation propaganda, mainly during world wars. In their analyzes, the authors took into account propaganda posters using the pointing finger motif, the prototype of which was the Alfred Leete poster from 1914. A hand with a pointing finger stretched out towards the recipient of the message and the text “Your country needs you” became an inspiration for many other posters, exceeding time and geographical space with their influence. The aim of the article is an attempt to answer the question about the role of this specific gesture in war and political propaganda that uses visual communication. The pointing finger motif in the poster became attractive to other artists who used it in changing conditions, also outside of military propaganda. The analysis was carried out based on the methodology of interpretation of visual materials by Gillian Rose.

1. Introduction

Urszula Jarecka (Jarecka, Citation2008) in her work on visual propaganda poses an interesting question about its effectiveness. How do you measure its impact? Should we take into account the results of the propaganda campaign to which it was devoted? Or, for example, the popularity of a motif used in visual propaganda; its repetition in propaganda messages, or its presence in popular culture? If one were to concentrate on the latter approach and examine the repetition of the motif, Alfred Leete’s poster from 1914 would be probably a record holder. For propaganda purposes, apart from the British, it was used by Americans, Italians, Germans, Russians, Poles, Canadians, and it is probably not a complete list. It became part of the visual culture (Bachmann-Medick, Citation2016; Mitchell, Citation1994) of the 20th and 21st centuries. As U. Jarecka writes “Since the promotion of Lord Kitchener’s poster and his call ‘Your country needs you, many projects from the First World War used a hand extended towards the viewer with the index finger pointed at the viewer’s chest (…) The attractiveness of addressing to the public directly has inspired propaganda activists in many countries” (Jarecka, Citation2008).

What is so special about the index finger motif? Why have so many countries decided to use this motif for agitation propaganda? Jacek Wasilewski drew attention to the specificity of gestures, visible on the described posters. Characterizing the elements related to the rhetoric of domination, the author describes, among other things, the role of visual gestures and behaviors, and emphasizes that: “These gestures [gestures of domination] can be treated as a presentation of intentions undertaken by the dominant, e.g. ostentatiously pointing the finger at someone may not only be ostensive but performed by the dominant will be directive (Do it!) or exclusionary (Go away!) (Wasilewski, Citation2006). Similarly, when it comes to eyesight: “Sight plays an extremely important role in controlling the situation and is, therefore, a tool for maintaining domination. (…) Dominant’s watchful gaze allows him to convey the information that he has his eye on someone or is keeping an eye on someone. Fixing one’s gaze is often treated as a taunt (…) or as a threat” (Wasilewski, Citation2006). The construct presented here reflects the hypnotic power of the impact of the posters analyzed in the article.

The aim of the text is an attempt to answer the question of why the authors of propaganda posters, especially during world wars, so often decided to use the “pointing finger” gesture? What was the power of its message? To what extent did the analyzed posters prove to be an effective tool of persuasion?

2. Research sample and methodology

The analysis was carried out based on Gillian Rose’s visual interpretation methodology. However, there are other methods of analyzing visual materials available, for instance, discourse analysis (Biskupska, Citation2011; Widdowson, Henry, Citation2003) or visual grounded theory (Glaser, Citation2008; Glaser & Holton, Citation2010; Glaser & Strauss, Citation2006). The latest is the analysis of biometric data: eye movements and face mimics (Szurmiński & Kisilowska, Citation2019). We chose G. Rose’s method considering its functionality and applicability.

Rose states that “interpretations of visual images broadly concur that there are three sites at which the meanings of an image are made: the site(s) of the production of an image, the site of the image itself, and the site(s) where it is seen by various audiences” (Rose, Citation2002, p. 16). Analyzing them, several questions can be posed for each site. For instance, considering the production site—when and who developed an object, with what technologies or techniques. Considering the image itself—what does it present, what are its constitutive elements, what is its material form, which element attracts the viewer’s gaze the most and why, what colors were applied, what is the meaning of individual elements of an image. Considering the reception site—there are questions of the original audience of this material and original context, specifically important for visual materials developed 50 or 100 years ago. There are also questions of its contemporary reception and audience—is there more than one interpretation, how the image can be perceived by diversified audiences (Rose, Citation2002). This methodology assumes also that not all these questions can be answered on a satisfactory level (e.g. about the author). Nevertheless, the application of the same analysis scheme to all images enables standardization of the procedure and an identical approach to each of the objects being analyzed.

The research sample was selected deliberatively. The following factors were considered: the figure with an index finger pointing at a potential addressee, historical posters (to avoid modern, pop-cultural adaptations), from different states and political systems, and being used in political communication.

3. Agitation propaganda

In the classification of propaganda activities, according to their functions, the most common division is the distinction of integration and agitation propaganda. Both are generally part of activities in the field of social (sociological) propaganda and at the same time are addressed to the citizens of a particular country (internal). In the area of political communication, apart from those mentioned above, propaganda is also analyzed due to its functions: informational and interpretative, disinformative, and hard-hitting (Dobek-Ostrowska, Citation2007).

Agitation propaganda attempts to maintain the positions and interests represented by the “officials” who sponsor and sanction the propaganda messages. From the perspective of the subject matter discussed in the article, agitation propaganda is more interesting while it seeks to arouse people to participate in or support a cause. It attempts to arouse people from apathy by giving them feasible actions to carry out (Jowett & O’Donnell, Citation2015). The French propaganda researcher Jacques Ellul describes this phenomenon in a little more detail. According to him, agitation propaganda: “(…) tries to stretch energies to the utmost, obtain substantial sacrifices, and induce an individual to bear heavy ordeals. It takes him out of his everyday life, his normal framework, and plunges him into enthusiasm and adventure; it open to him hitherto unsuspected possibilities, and suggests extraordinary goals that nevertheless seem to him completely within reach“ (Ellul, Citation1973).

4. A poster as a form of propaganda

When analyzing the propaganda posters, it is worth starting with the approach to propaganda itself, in the definition of which the objectives of the sender of propaganda messages and their impact on the recipients come to the fore (Lakomy, Citation2019). Based on the works of the classics of political science, communication sciences, philosophers, and sociologists, M. Bartoszewicz (Citation2019) proposed defining propaganda as a set of activities showing the following features: systematic, one-sided, institutionalized, realized with the use of persuasive and manipulative methods, having an emotional-intellectual impact on the consciousness of individuals or social groups, aimed at maintaining or modifying their attitudes or behavior, following the interests of the holder of propaganda. T. Tokarz notes that the information content is subordinated to the interpretative and persuasive layer, and “the main intention of the propaganda sender is not to provide the recipients with objective (adequate) knowledge, but to convince them to their own vision of the world, instill the desired beliefs, and provide ready-made patterns for thinking. In a more concrete dimension, it is usually about recruiting citizens for an idea, action, gaining supporters and allies” (Tokarz, Citation2007).

Narrowing propaganda to its visual context, it is worth referring to Laswell (Citation1995), who defined visuality in propaganda as a technique of influencing human activities through image manipulation. W. Schulz (Schulz, Citation2006) referring to the deliberate use of a specific medium to influence the recipient in the process of political communication, quotes McLuhan’s thesis “Medium is a message”. He also emphasized that the medium is not a neutral mediator of the message, and the use of the form itself leaves a mark on the meaning of the message.

Agitation propaganda can take various forms, and one of the oldest indirect propaganda involving one sense—sight—is visual propaganda (Dobek-Ostrowska, Citation2007; Kolczyński, Citation2008). The propaganda poster is perceived both as an element of press propaganda and external propaganda (Dobek-Ostrowska, Citation2007). A propaganda poster, which is a visual means, according to the division of propaganda means proposed by H. Kula, can be included in the category of direct influence measures (Kula, Citation2005). The advantages of this form of propaganda communication include durability of the message and—due to the elements used—the possibility of careful preparation (Dobek-Ostrowska, Citation2007).

Although the oldest known poster dates back to the Middle Ages (Lisowska-Magdziarz, Citation2009), and the development of the poster as a form of communication dates back to the 17th century, it is only at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries that we can talk about the production of posters on an unprecedented scale. Undoubtedly, it was related to the improvement of color printing techniques, which resulted in lower costs and better production speed (Ferenc et al., Citation2011). As indicated by Ferenc et al. (Citation2011): “during the First World War, all participants of the conflict reached for this proven, popular and effective medium. From that moment on, the poster became an indispensable element of wartime propaganda. The means of persuasion applied in visual advertising began to be used to control public mood. The citizens were encouraged to make a post-war effort, to work for the arms industry, reminded of the need to save and preserve strategic information, and finally, the enemy was identified”. A similar function of persuasion in visual communication is noted by Pratkanis and Aronson (Citation2003): persuasive images (…) replace carefully constructed arguments with slogans and images. The role of print as a medium that influenced the development of propaganda techniques and acted even as a propaganda distributor was noted by Dobek-Ostrowska et al. (Citation1999).

It is not without significance that the poster, due to its availability, can affect a wide audience, seemingly not attracting their attention. As M. Golka (Citation1994) emphasizes: bills and posters are perceived even by passers-by in a hurry. By multiplying advertisements, they are influenced by them to a much greater extent than they might seem. J. Fras (Citation2005), indicating the advantages of using iconic messages in political communication, points to the ease of reception (images are perceived by humans faster), large informative capacity, and persuasive values directly related to influencing the most important human sense, namely the sense of sight.

The goals most often formulated in relation to images used in political propaganda may differ. The most frequently mentioned functions are advertising, devaluation, integration, separation, stabilization, and agitation (Tokarz, Citation2007).

Ferenc et al. (Citation2011) draw attention to the fact of the social impact of propaganda posters, which constitute a specific “directed” relationship between the citizen and the state, is consciously planned in terms of the assumed goals and effects of impact. They capture the possibility of the egalitarianism of citizens who, regardless of their financial situation or social status (and often the level of education associated with it), were recipients of propaganda content.

Although many authors emphasize the fact of the strong influence of the propaganda poster and the higher perception of graphic forms, to do so, the preparation of a poster with high impact requires several procedures and the combination of forces of professionals from the artistic and communication areas (Ferenc et al., Citation2011). Tokarz (Citation2007) draws attention to the connection between the effectiveness of a propaganda poster and the recipient’s knowledge of the message. He links the decoding process itself as associated with the appropriate “preparation” of the recipient, which may mean accompanying (or preceding the message in a visual form) other forms of influence.

Visual propaganda shapes the desired attitudes through pictorial elements (Olzacka, Citation2017), hence the measures aimed at influencing the poster’s impact are indicated as: the play of colors, the use of a perspective suggesting the reception of the poster’s message, thoughtful reflection of the poster’s hero (physiognomy, silhouette, outfit, gestures props). The design of the poster had to influence emotions in order to evoke specific reactions. Hence, the posters were supposed to frighten, terrify, arouse disgust, evoke pity, shame, hope, faith in the possibility of change, joy, and euphoria. The power of emotions expressed in artistic and communicative expression is such a significant element that sometimes it is necessary to base the construction of a propaganda poster on the controversiality and ultimacy of the content (Ferenc et al., Citation2014). It is also worth emphasizing that despite the use of phrases referring to visuality, the propaganda poster should be analyzed due to the special role of the relationship between the word and images accompanying verbal messages (Poprawa, Citation2020; Szurmiński & Kisilowska, Citation2019).

Graphic elements, artistic procedures, and planned communication posed quite a challenge because the structure of the message contained in the propaganda poster had to be clear and coherent enough for the message contained in it to be decoded in accordance with the intentions of the sender. Therefore, the messages contained in the poster structure had to be expressive and provide minimum space for individual interpretation; they had to clearly define the values important to convey to the recipients and allow the message to be read.

5. Gestures

Gestures, including pointing gestures, are the subject of research conducted by representatives of many fields of science. Communication and media science seem to combine research in the field of linguistics and semiotics, and additionally take into account the results of observations and analyses related to psychology, anthropology, or even zoology (primatology). Among other things, the article focuses on the study of the specific role of the pointing gesture in the area between art (poster) and political science (propaganda).

According to many authors, the study of gestures, or more broadly—non-verbal communication, is subject to similar mechanisms and conditions as traditional linguistic research, while the theories concerning the linguistics of spoken language are adaptable in the field of research on the gestures and signs language (Armstrong et al., Citation1995). From the point of view of the research presented in the article, pointing gestures, specifically pointing fingers, are of particular importance. This gesture shows the sender’s knowledge of space and refers to the indication of the place the message concerns, a specific thing or person in this place, and sometimes it also refers to the indication of movement in space (Haviland, Citation2000). Various factors (including personal or cultural) are significant in terms of the form of pointing gesture, relating to whether the gesture is expressed with the entire hand or with the index finger. A research study by Flack et al. (Citation2018) indicates differences in this respect even between the visibility and invisibility (abstractness) of the indicated objects. Despite its importance in the development of social cognition and communication skills during childhood, little is known about the ontogenetic phenomenon of the origins of the pointing gesture. Innate cognitive skills are of primary importance (Nick et al., Citation2007), which are strengthened in the process of socialization through imitation (Matthews et al., Citation2012). The innate skills and basic experience of a person determine their perception of hand movements and distinguish these movements in terms of intention and purpose (Załazińska, Citation2016). Each cognition triggers conceptual processes, which, according to Haman (Citation2011), concerns mainly children, but seems to be even more justified in relation to adults.

Kita (Citation2003) emphasizes the importance of the pointing gesture in interpersonal communication, social interactions, as well as in the area of language analysis, indicating four key premises. The pointing gesture is ubiquitous in our daily interactions with others. In communication about spatial activities and localization, pointing is almost inevitable. Even when we talk about things that are distant in time and space, we often point to the seemingly empty space in front of us. Assigning the meaning of location by pointing is a characteristic part not only of supporting spoken language, but also an important part of the grammar of sign languages (Cieśla, Citation2012). Secondly, pointing is uniquely human behavior. In other words, pointing separates humans from primates, as does the use of language. Thirdly, pointing is primary in ontogenesis. Pointing is one of the first comprehensive communication devices that an infant acquires (Butterworth, Citation2003). Fourthly, pointing can be used to create more types of signs. For example, a pointing gesture can create an iconic representation by tracing the shape or trajectory of motion (Goodwin, Citation2003).

Another issue is the use of the pointing finger gesture in art. In a biography of Leonardo da Vinci published a few years ago, Isaacson (Citation2017), among many other obsessions of the Renaissance master, also mentions this one—the human pointing gesture. In numerous paintings and sketches of his authorship, the depicted figures usually direct the index finger upwards or outwards. In many cultures, this movement took the form of an outstretched arm and an index finger pointing in a certain direction, sometimes also at the viewer. Talmy (Citation2017) interprets this as “projecting” an imaginary line towards the target of the message. The effect of this gesture can sometimes, according to Langton and Bruce (Citation2000), be irritating, as it commands, orders, and redirects the viewer’s attention in the direction desired by the author, or it is a direct response towards the viewer, demanding his attention and recording of the next message.

6. The use of the theme in the years 1914-1918

The literature on the subject assumes that the period of the First World War was the time of institutionalized propaganda (Jowett & O’Donnell, Citation2015). Of course, there had been many earlier efforts to systematize propaganda activities, but the scale and momentum of activities taking place in 1914–1918 and the use of mass media in the dissemination of propaganda messages, gave rise to the following conclusion: “No longer did single battle decide wars; now, whole nations were pitted against other nations, requiring the cooperation of entire populations, both military and psychologically” (Jowett & O’Donnell, Citation2015).

As there was no radio or television at that time, the agitation poster, along with the press, became the main tool for influencing mass audiences. The latter, on the other hand, had to overcome various technical limitations, such as color printing. The propaganda poster was cheap to produce. It also used color, which attracted the viewer’s eye, but at the same time, the color palette was quite sparing. As Pearl James writes (2009) “they were both signs and instruments of two modern innovations in warfare—the military deployment of modern technology and the development of the home front. In some ways, the medium of the war poster epitomizes the modernity of the conflict. In addition to being sent to the front, they reached mass numbers of people in every combatant nation, serving to unite diverse populations as simultaneous viewers of the same images and to bring them closer, in an imaginary yet powerful way, to the war. Posters nationalized, mobilized, and modernized civilian populations”.

An excellent example of such an institutionalized action, which was to contribute, among other things, to the mobilization of society was the establishment of The Parliamentary Recruiting Committee (PRC) by the British in 1914. This institution ordered over a hundred different poster designs, of which at least two used the gesture under analysis. The first was a 1914 poster by Alfred Leete depicting the newly appointed Minister of War Lord Kitchener, who, pointing his index finger at the audience, urged “Britons. [Kitchener] Wants You. Join Your Country’s Army” (). The second poster () by an unknown author appeared a little later, in September 1915 (James & Thomson, Citation2007). However, the prototype for these was the cover of the illustrated magazine “London Opinion” published on 5 September 1914() (Bownes & Fleming, Citation2014).

Figure 1. Alfred Leete, “London opinion. You Country Needs You”, 1914; Alfred Leete “Britons. [Kitchener] Wants You. Join Your Country’s Army”, 1914; author unknown, “Who;s Absent? Is It You?” 195.Source 1: Bownes, Fleming, 2014: 36Source 2: Slocombe, Slocombe 2014: 5.Source 3: Bownes, Fleming, 2014: 124.

![Figure 1. Alfred Leete, “London opinion. You Country Needs You”, 1914; Alfred Leete “Britons. [Kitchener] Wants You. Join Your Country’s Army”, 1914; author unknown, “Who;s Absent? Is It You?” 195.Source 1: Bownes, Fleming, 2014: 36Source 2: Slocombe, Slocombe 2014: 5.Source 3: Bownes, Fleming, 2014: 124.](/cms/asset/cb82e766-acd5-4f79-b8a2-f25cb37592c0/oaah_a_2037228_f0001_oc.jpg)

The comparison of the two posters allows us to conclude that they use the same gesture in the formal sphere, while their construction is slightly different. In the case of the second poster, foreground and background figures are visible. The main character is John Bull, a metaphorical personification of the English value system. In the background, we also notice the second plan heroes, as the viewer can guess—newly enlisted recruits. The slogan, although worded differently, (“Who’s Absent? Is It You?”), carries the same message, but as some authors note: “Once recruitment began to dwindle, the campaign adopted a more threatening tone by depicting those who were already fighting and thus, by implication, suggesting that there were those who were not doing their fair share. (…) The pressure was thereby exerted not just directly on potential recruits who had not yet joined up, but also indirectly on their families, who were also expected to make the sacrifice” (Taylor, Citation2003).

There is no exact data on how many posters were exactly printed during the first wave of the war; Hardie and Sabin report that the PRC has distributed a total of over 2.5 million copies in the British Isles (Hardie & Sabin, Citation2016). The recruitment campaign turned out to be successful. The British professional army at that time numbered 250,000 soldiers. It was supported by reservists, about 100,000 of whom could be called up in a short time. Lord Kitchener, after taking office, set himself the goal of recruiting 100,000 volunteers. In a short time, by the end of August 1914, 300,000 soldiers were recruited (Bownes & Fleming, Citation2014).

However, the measure of success is that the “pointing finger” motif was immediately adopted by other countries. In 1917, Italians, Americans, Canadians, Germans, and again the British introduced their versions of the poster. As U. Jarecka (Citation2008) emphasizes, it was possible because: “In the propaganda of the WWI in various countries, it was typical to use similar propaganda measures and visual solutions—it was not about copyright, but about victory”. The direct cause of propaganda development was the increasing number of casualties on all fronts of the war. The war affected all the nations of Europe and the USA, as modern weapons were used at that time, which allowed for the mass killing of the enemy; machine guns, war gases, grenades, the first tanks, and submarines contributed to the exponential losses. So another fresh enlistment of recruits was needed.

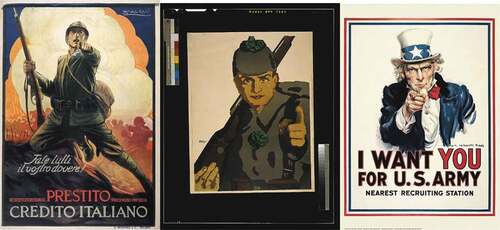

Italian artist Achille Lucciano Mausan urged people to join the army. The poster was released in 1917 and included the slogan “Fate tutti il vostro dovere!” [“Everyone should do their duty] (). Another poster in the same style is the work of the German artist, Magdalene Koll. The poster depicted a German soldier, with a rifle slung around his shoulder, pointing his finger at the viewers, asking: ‘Ich gehe hinaus an die Front. Hast du die 6. Kriegsanleihe schon gezeichnet?’ [I’m going to the Front. Have you subscribed to the 6th War Loan yet?”] (). Thus, the significance of the propaganda message expanded, calling not only for contribution at the front but also for financial support through the purchase of war pay vouchers. Finally, we have the most famous theme in pop culture history, created by James Montgomery Flagg ().

Figure 2. Achille Lucciano Mauzan, “Fate tutti il vostro dovere!”, 1917; Magalene Koll, “Ich gehe hinaus an die Front. Hast du die 6. Kriegsanleihe schon gezeichnet?”, 1917; James Montgomery Flagg, “I Want You for U.S. Army”, 1917.Source 4: Europeana Collections 1914–1918, https://classic.europeana.eu/portal/pl/record/9200199/BibliographicResource_3000052896274_source.html?utm_source=new-website&utm_medium=button.Source 5: Library of Congress, https://lccn.loc.gov/2004665993.Source 6: Military History Now, https://militaryhistorynow.com/2016/12/12/i-want-you-the-story-behind-one-of-the-most-famous-wartime-posters-in-history/.

The American version of the poster, like the others presented above, was not very innovative, but it was adapted to American conditions. Instead of Lord Kitchener or anonymous soldiers, the poster featured Uncle Sam. The poster itself was printed in over 4 million copies. The recruitment campaign also proved successful, with approximately 2 million volunteers joining the US Army, also inspired by this poster (Manning and Romerstein Citation2004).

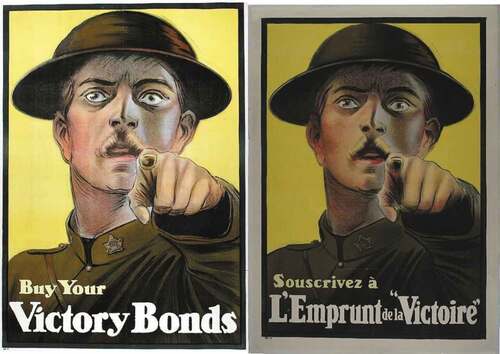

As noted earlier, the creation of propaganda posters used well-known motifs, especially those that became a breakthrough in propaganda communication and significantly increased the chances of success of the propaganda campaign. Each of these posters is slightly different; the color scheme is especially noteworthy. Sometimes, however, the propaganda used identical motives, but the language in which the slogan was written changed. A good example here are two posters from 1917 and 1919 calling for the purchase of war pay vouchers. Both come from Canada ().

Figure 3. Author unkown, “Buy Your Victory Bonds”, 1917; author unkown, “Souscrivez a l’Emprunt de la Victoire”, 1919.Source 7: Canadian War Museum, https://www.warmuseum.ca/collections/artifact/1334232/?q=Buy+VICTORY+BONDS&page_num=1&item_num=72&media_irn=3084521.Source 8: Canadian War Museum, https://www.warmuseum.ca/firstworldwar/objects-and-photos/propaganda/materials-for-the-war-effort/?target=2158.

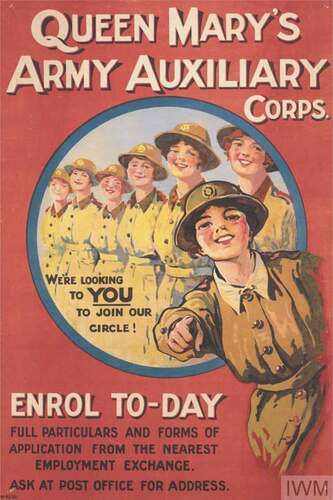

The end of the First World War by no means stopped the process of creating propaganda posters using the motif of “pointing finger”. A very intriguing design was that of a recruitment poster for the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) created in 1917. The establishment of this auxiliary service was associated with the fact that it was more and more difficult to recruit male soldiers to the army, as some of them had to work, for example, in factories powering the defense industry. For the first time in history, female volunteers could join the British Army in auxiliary roles other than nursing.

The presented poster () dates from 1918. It was prepared in connection with the British Queen’s patronage of the service: “Impressed with the WAAC’s work, Queen Mary became its patron in 1918. The corps was renamed Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps (QMAAC) to reflect its fine conduct during the German Spring Offensive of that year”.

Figure 4. Artist unknown, “Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps. We’re looking to you to join our circle! Enrol to-day full particulars and forms of application from the nearest employment exchange. Ask at post office for address”, 1918.Source 9: Imperial War Museum, https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/28938.

7. The use of the theme in the years 1918-1939

The subsequent versions of the poster using the pointing finger gesture appeared in the Weimar Republic and Soviet Russia. All were related to recruitment. The first of them (poster 10) encouraged to join the newly-created Reichswehrs. Tomasz Ferenc (Citation2011) claims that after losing the war, the Germans wished to take revenge for their fallen comrades, sons, fathers, and heroes. Hitler was to make this dream come true. A German soldier wearing a helmet points his finger toward the observer saying: “Auch du sollst beitreten zur Reichswehr” (“You too should join the Reichswehr”).

The story with Soviet posters is more interesting, mainly due to the circumstances. The same means of expression was used by two different artists standing on both sides of the barricade. The motif of an outstretched index finger was used by the Soviet painter Dmitry Stachievich (Moor) (), on whose poster the Red Army soldier asked: Have You Registered As a Volunteer?. The answer to this was a poster by an unknown artist, encouraging people to join Anton Denikin’s Volunteer Army, which fought against the Bolsheviks in 1920 ().

Figure 5. Julius Ussy Engelhard, “Auch du sollst beitreten zur Reichswehr”, 1919; Dmitrij Stachijewicz Orłow (Dmitrij Moor), “Ty, zapisalsia dobrovol’tsem?”, 1920; artist unknown, “Poczemu Wy nie w armji?”, 1920.Source 10: Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004665873/.Source 11: Товарищество плакатистов, http://plakat-msh.ru/Moor-(Orlov)-Dmitrij.Source 12: Military Wikia, https://military.wikia.org/wiki/Volunteer_Army.

In the interwar period, the described motif was used again. Hungarian artist Sandor Ek (Alex Keil) also reached out for it. Between 1925 and 1933 he lived in Germany, preparing illustrations and graphics for German press titles: “Rote Fahne”, Arbeiter Illustrierte Zeitung”, as well as for other left-wing media (Budapest Poster Gallery)

Also from this period comes a poster prepared for the German communist youth organization—Young Communist League of Germany (Kommunistischer Jugendverband Deutschlands, abbreviated KJVD). The poster () is interesting in terms of composition because, unlike in the previously discussed examples, there is a centrally located and dominant figure (in this case—Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov (Lenin), but in the foreground, he is preceded by a group of young people with a red banner. As it is not a recruitment poster, the message is also different—nor does it encourage the purchase of war pay vouchers but advertises the KJVD week in April 1928 in Chemnitz.

Figure 6. Sandor Ek (Alex Keil), “Reichsjugendtag des KJVD, Chemnitz, Ostern, 6–9. April 1928”, 1928.Source 13: AKG-IMAGES, https://images.app.goo.gl/73H42z5JhUmPSVLH9.

8. The use of the theme in 1939-1945

Contrary to 1914–1918, during the Second World War, the poster with the pointing finger became less visible. It can be assumed that it was simply related to a much greater number of posters on various topics; the visibility of the analyzed poster was slightly blurred. The second factor was that perhaps it had lost its novelty effect, it was no longer so mesmerizing. Finally, propagandists from various sides of the front began to use leaflets, radio, and film propaganda on a much larger scale (Manning and Romerstein Citation2004).

However, this does not mean that this motif has been completely abandoned. The Americans again reached for proven patterns, i.e. the already discussed theme with “Uncle Sam”, supplemented later with a poster on which the hand itself appears alone. In the UK Ministry of Information which was responsible for the fight on the home front, first produced a series of posters that “(…) were focused on upholding the nation’s morale, a policy arising from predictions of a German air onslaught at the outset of war” (Slocombe & Steel, Citation2014).

The thread concerning the “Deserve Victory” poster is reminiscent of the story described with Alfred Leete’s poster. First, “The Times. Saturday” in June 1940 published a proclamation in the form of a full-page advertisement (advert 1) containing a message to the citizens of Great Britain by Prime Minister Winston Churchill, followed by the poster. Both were linked by the slogan “Deserve Victory”, which appeared on both materials ().

Advertisement 1. Deserve Victory, The Times. Saturday ”29 June 1940.Source: Museum of World War II, http://w.museumofworldwarii.org/churchill.html.

Figure 7. Artist unknown, “Deserve Victory” [alternative version Winston Churchill Says We Deserve Victory!”], 1940; Dmitrij Stachijewicz Orłow (Dmitrij Moor), “Ты чем помог фронту”, 1941, artist unknown. “Are You Doing All You Can?”, 1942.Source 14: James, Thomson, 2007: 46.Source 15: Омская государственная областная научная библиотека, http://omsklib.ru/Vyistavki/gd33gnjus8/gd3z8cu7b3.Source 16: Library of Congress, URL: https://www.loc.gov/wiseguide/jul08/patriotism.html

![Figure 7. Artist unknown, “Deserve Victory” [alternative version Winston Churchill Says We Deserve Victory!”], 1940; Dmitrij Stachijewicz Orłow (Dmitrij Moor), “Ты чем помог фронту”, 1941, artist unknown. “Are You Doing All You Can?”, 1942.Source 14: James, Thomson, 2007: 46.Source 15: Омская государственная областная научная библиотека, http://omsklib.ru/Vyistavki/gd33gnjus8/gd3z8cu7b3.Source 16: Library of Congress, URL: https://www.loc.gov/wiseguide/jul08/patriotism.html](/cms/asset/36ce5d77-4002-46b0-8f44-14db7ab76c65/oaah_a_2037228_f0007_oc.jpg)

The poster prepared by Dmitry Stachievich (Moor) is an update of a previously prepared work from 1920 (poster 15). It displays the identical location of the characters and the same gesture of the outstretched finger (of course). Only the uniform of a Red Army soldier is modernized both with modification of the slogan.

The most interesting graphic material from the Second World War period is the American recruitment poster from 1942 (poster 16). An unknown artist decided to make an interesting modification (Wright, Citation2003). We are still dealing with an outstretched index finger, which is to attract the attention of recipients. Here, however, the message is strengthened by the fact that this finger and the entire hand are piercing us through the surface of the American flag. There are also no other figures on the poster; just the index finger and the slogan followed by a question mark. So here, as was the case with the Soviet posters, we have a sentence in the form of a question, which is to force the recipient to reflect on their behavior.

9. Use of the theme after 1945

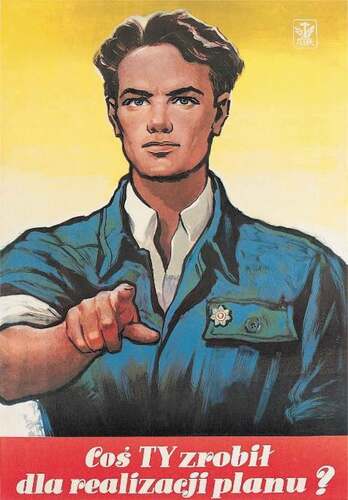

At the end of this analysis, reference was made to the original posters based on the described gesture, created for the propaganda of the People’s Republic of Poland. After 1945 in Poland, as in other satellite countries of the Soviet Union, painting and other areas of art were dominated by the style known as socialist realism. This term was coined by Ivan Gronski, one of Stalin’s advisers (Wieczorkiewicz, Citation2001). The interpretation of how it should be understood was provided by the propagator of this trend and the term, Maksym Gorky. In May 1932, in the journal “Literaturnaja Gazieta”, M. Gorki used the “socialist realism” for the first time, explaining that socialist reality and everyday life should be combined and presented in art (Studzińska, Citation2014). Obviously, this does not exhaust all the topics covered in socialist realism, because, as we will see in the posters presented below, the topic of propaganda messages did not concern only everyday life.

Two of the presented posters () were prepared in the Propaganda Posters Studio of the Propaganda Department of the Main Political and Educational Board of the Polish Army, which operated in the period 1944–1945 at the Central Soldier’s House in Lublin (Pol, Citation1980). Their author is Włodzimierz Zakrzewski, and as can be seen, the meaning of these posters only changes due to the adjustments to the slogan. They are graphically identical, but the format is different; the size of the first in the original was 79.5 × 80 cm, while the second appeared in two slightly different sizes: 63 × 80 cm and 64 × 84.5 cm.

Figure 8. Włodzimierz Zakrzewski, “Dlaczego Ty nie jesteś w wojsku?”, 1944; Włodzimierz Zakrzewski, “Coś Ty zrobił dla odbudowy stolicy?”.Source 17–18: Pol, Citation1980: 56, 106.

In the first case () we are dealing with a classic agitation poster, which encourages people to join the Polish People’s Army, while the second (poster 18), created after the end of warfare in 1945, calls for a common reconstruction of the country. As for the third poster (), it is an emanation of the classic art of socialist realism. We have a single plan, in its center, there is a young man, a worker in working clothes, and a badge of the Union of Polish Youth. He stretches out his index fingers towards the viewer, asking what the observer did to implement the plan of economic development adopted on 21 July 1950 and building the foundations of socialism (Niedojadło, Citation2016). So here we have a reference to socialist reality and everyday life in one, as Maxim Gorky postulated. It is worth paying attention to the fact that the slogan itself gives the impression of being tack on and is not an integral part of the poster. The space of Jagodziński’s poster is composed in such a way that the inscription seems to constitute a separate segment, artificially tacked on to the painted figure. Following this observation, one could be tempted to try to add to the poster another text with a propaganda overtone. Even a cursory knowledge of the slogans used in party agitation allows us to say that many of them would be able to easily serve as a verbal commentary. Instead of a call for a more reliable implementation of the outlined plan, it could as well be an incentive of the Union of Polish Youth member’s addressed to young people, a reminder of obligatory state supplies addressed to the farmer, or military agitation (Niedojadło, Citation2016).

Figure 9. Lucjan Jagodziński, “Coś Ty zrobił dla realizacji planu?”, 1953.Source: Gazeta Wyborcza: https://warszawa.wyborcza.pl/warszawa/51,34861,17690900.html?i=1

It is, therefore, the same situation as in the posters by Tadeusz Jagodziński analyzed above, where an identical graphic motif could and has been used for various propaganda purposes.

10. Conclusions

Most of these recruitment posters were developed on a quite simple composition scheme. Most of them (15 out of 19) present one figure. Posters no 3, 13, and 19 are excluded, with other persons located in the background, and poster no 16, where the anonymous author placed only a hand pointing at a viewer.

Most of the figures wear military uniforms—the women as well, presented at one poster. Excluded are politicians (metaphorical figures of John Bull, Winston Churchill, Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov (Lenin)). Even a Polish workman at the poster 19 wears something like a uniform, i.e. a work apron. The only artifact on the posters is a military rifle held in hand by four figures or slung over a shoulder by one soldier.

Except for one case, of a single hand with an index finger presented at the poster, a figure gazes directly with hypnotizing eyes at a viewer, which is a measure strengthening the poster’s message and catching the attention. The figures are presented in the American (9 times), medium (5 times), and narrow (8 times) plans. The general presentation mode depends on how the figure is presented. If the scene was planned as a dynamic one, the American plan is applied. If it is static—a medium or narrow plan. Thus, the effect of gaze hypnotizing viewers is strengthened, which is evident in posters no 7, 8, and 14.

The analyzed posters were presented mostly in the public sphere: public transport and stops, underground stations, and dedicated showcases. Their visibility in such locations, besides composition, depended also on the colors. Red color dominates in these materials, fulfilling two functions. When it is used on a relatively small area of a poster (like in no 1–3 and 19), it accents details. However, if it covers most of a poster (for instance no 11, 13, 15), its role is to attract the attention of a potential viewer. The other colors used include—shades of blue (poster no 4) and soft yellow (posters no 7, 8, 11, 17, 19) as a background.

Considering colors, two unconventional posters are worth noticing, namely the German posters from 1917 (no 5) and 1919 (10). The first one encouraged the purchase of war bonds, and the other—to join the German army. The black color dominates in both, as a background for the figure of a soldier in a dark green uniform. This is a quite surprising composition because a poster in such colors became unreadable in dimly lit places.

Agitation propaganda is an element of building the expected attitudes but also serves to achieve the set goals. One of its important elements is the poster. It was used in many countries and many political systems. Especially interesting is the motif of the index finger, which has been described and analyzed in this article. The presented motif is discussed in the context of its characteristic features, taking into account the expected effect, which was assumed by the dominant person. The article contains an analysis of selected propaganda posters. Another element important from the point of view of scientific research were gestures, which are closely related to the pointing gesture.

The article also presents the use of the poster in the context of influencing the masses, due to limited access to other media (especially in the period 1914–1918). It was a form of effective interaction, however, limited mainly technically. Nevertheless, the posters achieved their intended goals, e.g. in the context of military recruitment processes. These posters were based on recognizable symbols but also included well-known motifs. As a result, their effectiveness increased.

The index finger was therefore an enhancement of the message, a focus on quick reflection and decision-making by everyone watching it. It motivated and had the character of a command. In some cases, it could even induce a sense of guilt if the person who saw the message did not plan to follow the voice speaking from the poster. The motifs of posters with an outstretched finger, taking into account other important elements. For example, the flag, state colors, or eye contact maintained by the dominant, were used mainly due to their effectiveness, propaganda, and persuasion potential, as presented in this article.

Author Statement

The observations and conclusions presented in the article are the result of interdisciplinary research undertaken by scientists from the University of Warsaw and UITM in Rzeszów, Poland. The research team adopts a media science, political science and psychological perspective to assess the methods of visual communication used in political persuasion and propaganda. The research uses the method of desk research, searching for visual sources, content analysis, critical discourse analysis, descriptive psychological methods and methods of interpreting visual materials. The presented manuscript is part of a broader research project carried out by a team of several authors. It focuses on the relationship between the area of art and architecture with social communication, including visual communication, marketing communication and political communication.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Armstrong, D., Stokoe, W., & Wilcox, S. (1995). Gesture and the nature of language. Cambridge University Press.

- Bachmann-Medick, D. (2016). Cultural turns. New orientations in the study of culture. Walter de Gruyer GmbH.

- Bartoszewicz, M. (2019). Teorie propagandy w obliczu algorytmizacji internetowego komunikowania społecznego. Kultura Wspólczesna, 1(2019). 84–17. doi:10.26112/kw.2019.104.07.

- Biskupska, K. (2011). Analiza dyskursywna amerykańskich plakatów rekrutacyjnych okresu II wojny światowej. In T. Ferenc, W. Dymarczyk, and P. Chomczyński (Eds.), Socjologia wizualna w praktyce. Plakat jako narzędzie propagandy wojennej. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego. 124–159.

- Bownes, D., & Fleming, R. (2014). Posters of the First World War. Shire Publications Ltd.

- Butterworth, G. (2003). Pointing Is the Royal Road to Language for Babies. In S. Kita (Ed.), Pointing: Where language, culture, and cognition meet. Erlbaum. 9–33 .

- Cieśla, B. (2012). Językowe własności systemu komunikacji głuchych. Folia Linguistica, 46(1), 53–59 . http://hdl.handle.net/11089/5961

- Dobek-Ostrowska, B. (2007). Komunikowanie polityczne i publiczne. Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN.

- Dobek-Ostrowska, B., Fras, J., & Ociepka, B. (1999). Teoria i praktyka propagandy. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego.

- Ellul, J. (1973). Propaganda. The formation of men’s attitudies. Vitage Books.

- Ferenc, T. (2011). Socjologia wizualna w praktyce: Plakat jako narzędzie propagandy wojennej. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego.

- Ferenc, T., Dymarczyk, W., & Chomczyński, P. (2011). Wstęp: Plakat jako narzędzie propagandy wojennej. In T. Ferenc, W. Dymarczyk, and P. Chomczyński (Eds.), Socjologia wizualna w praktyce. Plakat jako narzędzie propagandy wojennej. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego. 11–17.

- Ferenc, T., Dymarczyk, W., & Chomczyński, P. (2014). Wstęp: Wojna, obraz, propaganda. In T. Ferenc, W. Dymarczyk, and P. Chomczyński (Eds.), Wojna, obraz, propaganda. Socjologiczna analiza plakatów wojennych. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego. 7–12.

- Flack, Z., Naylor, M., & Leavens, D. (2018). Pointing to visible and invisible targets. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 42(2), 221–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10919-017-0270-3

- Fras, J. (2005). Komunikacja polityczna. Wybrane zagadnienia gatunków i języka wypowiedzi. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego.

- Glaser, B. G. (2008). Doing Quantitative Grounded Theory. Sociology Press.

- Glaser, B. G., & Holton, J. (2010). Remodelowanie teorii ugruntowanej. Przeglad Socjologii Jakosciowej, IV(2), 81–102. http://www.qualitativesociologyreview.org/PL/Volume13/PSJ_6_2_Glaser_Holton.pdf

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (2006). Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine Transaction.

- Golka, M. (1994). Świat reklamy. Agencja Badawczo-Promocyjna ARTIA.

- Goodwin, C. (2003). Pointing as situated practice. In S. Kita (Ed.), Pointing: Where language, culture, and cognition meet. Erlbaum. 226–250.

- Haman, M. (2011). Dlaczego pojęcia muszą być badane w ujęciu rozwojowym. In J. Bremer, and A. Chuderski (Eds.), Pojęcia. Jak reprezentujemy i kategoryzujemy świat. Universitas. 271–218.

- Hardie, M., & Sabin, A. (2016). War posters. The historical role of wartime posters art 1914-1919. Dover Publications, Inc.

- Haviland, J. (2000). Pointing, gesture spaces, and mental maps. In D. NcNeill (Ed.), Language and gesture: Window into thought and action. 13–46. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511620850.003

- Isaacson, W. (2017). Leonardo da Vinci. Simon & Schuster.

- James, D., & Thomson, R. (2007). Posters and propaganda in wartime. Franklin Watts & Imperial War Museum. Weapons of Mass Persuasion.

- Jarecka, U. (2008). Propaganda słusznej wojny. Media wizualne XX wieku wobec konfliktów zbrojnych. Wydawnictwo IFiS PAN.

- Jowett, G., & O’Donnell, V. (2015). Propaganda and Persuasion. Sage.

- Kita, S. (2003). Pointing: A foundational building block of human communication. In S. Kita (Ed.), Pointing: Where language, culture, and cognition meet. Erlbaum. 10–17.

- Kolczyński, M. (2008). Strategie komunikowania politycznego. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego.

- Kula, H. (2005). Propaganda współczesna. Istota – Właściwości. Wydawnictwo Adam Marszałek.

- Lakomy, M. (2019). Doktryna Bernaysa. Demokracja – Między propagandą a public relations. Wydawnictwo Naukowe Akademii Ignatianum w Krakowie.

- Langton, S., & Bruce, V. (2000). You must see the point: Automatic processing of cues to the direction of social attention. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Human Perception and Performance, 26(2), 747–757. https://doi.org/10.1037//0096-1523.26.2.747

- Laswell, H. (1995). Propaganda. In R. Jackall (Ed.), Propaganda. New York University Press. 13–25.

- Lisowska-Magdziarz, M. (2009). Reklama na świecie. Janiszewska, K. In Wiedza o reklamie. Od pomysłu do efektu. Bielsko-Biała: ParkEdukacja. 11–70.

- Manning, Martin J., & Romerstein, Herbert (2004). Historical dictionary of American propaganda. Santa Barbara: Greenwood Publishing Group

- Matthews, D., Behne, T., Lieven, E., & Tomasello, M. (2012). Origins of the human pointing gesture: A training study. Developmental Science, 15(6), 817–829. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7687.2012.01181.x

- Mitchell, T. (1994). Picture Theory: Essays on verbal and visual representation. The Univeristy of Chicago Press.

- Nick, E., Sotaro, K., & de Ruiter, J. P. (2007). Primary and secondary pragmatic functions of pointing gestures. Journal of Pragmatics, 39(10), 1722–1741 .https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2007.03.001

- Niedojadło, M. (2016). Jak kradło się w socrealizmie. Zapożyczenia motywów, tematów i rozwiązań formalnych w polskim plakacie propagandowym okresu realizmu socjalistycznego. Quart, 1(39), 67–85. doi:10.11588/quart.2016.1.65551.

- Olzacka, E. (2017). Wojna na Facebooku. Rola przedstawień wizualnych w “militaryzacji” mediów społecznościowych na przykładzie konfliktu na wschodniej Ukrainie. In A. Kampka, A. Kiryjow, and K. Sobczak (Eds.), Czy obrazy rządzą ludźmi? Wydawnictwo SGGW. 62–75.

- Pol, K. (1980). Pracownia plakatu frontowego. Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza.

- Poprawa, M. (2020). Przestrzenie słowno-obrazowe w propagandowych drukach ulotnych lat 1918-1939. Próba analizy w świetle lingwistyki tekstowej i teorii wizualności. Sztuka Edycji. Studia Tekstologiczne i Edytorskie, 17(1), 203–230 .https://doi.org/10.12775/SE.2020.00016

- Pratkanis, A., & Aronson, E. (2003). Wiek propagandy. PWN.

- Rose, G. (2002). Visual methodologies: An introduction to researching with visual materials. Sage.

- Schulz, W. (2006). Komunikacja polityczna. Koncepcje teoretyczne i wyniki badań empirycznych na temat mediów masowych w polityce. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego.

- Slocombe, R., & Steel, N. (2014). Posters of the Second World War/introduction by Nigel Steel; image selection by Richard Slocombe. Imperial War Museum.

- Studzińska, J. (2014). Socrelizm w malarstwie polskim. PWN.

- Szurmiński, Ł., & Kisilowska, M. (2019). Analysis of biometric data for eye movements and mimic reactions to archival propaganda posters. Studia Medioznawcze, 20(2), 130–146. https://doi.org/10.33077/uw.24511617.ms.2019.2.81

- Talmy, L. (2017). The targeting system of language. MIT Press.

- Taylor, P. M. (2003). A history of propaganda from the ancient world to the present day. Manchester University Press.

- Tokarz, T. (2007). Obraz jako narzędzie propagandy politycznej. Przestrzenie wizualne i akustyczne człowieka. Antropologia wizualna jako przedmiot i metoda badań. Edited by W. Krzemińska et al. Wrocław: Wyd. DSWE TWP. 335–343.

- Wasilewski, J. (2006). Retoryka dominacji. Trio.

- Widdowson, Henry, G. (2003). Text, context, pretext. critical issues in discourse analysis. Blackwell Publishing.

- Wieczorkiewicz, P. 2001. O sowieckim socrealizmie i jego genezie – Uwagi historyka. In: Realizm socjalistyczny w Polsce z perspektywy 50 lat. Materials from a scientific conference organized by the Institute of Cultural Studies of the Silesian University on October 19-20, 1999 in Katowice. Edited by S. Zaborowski & M. Krakowiak. Katowice: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego.

- Wright, I. (2003). You back the attack! We’ll bomb who we want. Remixed war propaganda. Seven Stories Press.

- Załazińska, A. (2016). Obraz, słowo, gest. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego.