Abstract

This paper examines 48 lemmas that typically exhibit variable pronunciations in English in order to establish the variants preferred by Nigerian English (NigE) speakers. The data for the study were extracted from the spoken part of International Corpus of English (ICE)—Nigeria and analysed using descriptive statistics (frequency counts and percentage distribution presented on tables). The findings establish phonemic variability as a widespread phenomenon in NigE, which is conditioned by a combination of exonormative and endonormative factors. The study concludes that, although NigE is largely influenced by the exoglossic Standard varieties, it is undergoing critical norm development which deserves to be codified in order to achieve endonormative stability. The present findings are, therefore, recommended as valuable resources for a future edition of a NigE dictionary as an important step towards standardisation.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

No doubt, many English lexical items are variably pronounced due to the history of the English language and the influence of emerging accents across the globe. A few studies in native Englishes have examined such variable words to improve on dictionary entries. Therefore, this paper investigates this tendency in Nigerian English using data from International Corpus of English-Nigeria (ICE-Nig.). The study reveals that many English words exhibit variable realisations in Nigeria due to the influence of the British and American English varieties and the emergence of some local linguistic usage. The pronunciations, which are categorised as primary, secondary and idiosyncratic variants, are proposed as essential resources for a future edition of a Nigerian English pronunciation dictionary which is germane for the codification of Nigerian English. This offers a fresh perspective into the phonological features of new Englishes in which the readership of Cogent Arts & Humanities would be interested.

1. Introduction

Many English lexical items are replete with variable pronunciations (Wells, Citation2008), which speakers often use without altering an intended meaning. For example, data may be realised as /deɪtə/, /dætə/ or /dɑːtə/ and dispute may be stressed as /ˈdɪspju:t/ or /dɪˈspju:t/. This phenomenon, referred to as free variation in the phonological circle, has been examined by a few scholars (e.g., Gimson, Citation1969; Shitara, Citation1993; Wells, Citation1999, Citation2003) with the purpose of improving on British and American English pronouncing dictionaries. However, empirical studies of pronunciation variants, with the goal of revising existing Nigerian English (NigE, henceforth) dictionaries, are very scarce in spite of the rigorous efforts geared towards codifying and standardising the variety. So far, only Akinola and Oladipupo (Citation2021) have pursued this goal at the word stress level. Other studies (e.g. Ademola-Adeoye, Citation2019; Awonusi, Citation1994; Kperogi, Citation2015; Obasi, Citation2019; Teilanyo, Citation2001; Umar, Citation2015) that have examined British and American expressions variably used in NigE have rather done so at different linguistic levels and with the purpose of identifying the more prevalent variety among NigE speakers.

This study, therefore, conducts a corpus-based survey of variable pronunciations of the phonemic constituents of 48 English lexical items, in order to establish the preferred pronunciation variants that could provide resource materials for a future edition of a NigE dictionary as an important step towards the codification of NigE. Specifically, the study will pursue the following objectives:

identify the variable pronunciations of some English lexical items in NigE;

establish the variants preferred by a majority of NigE speakers which could form part of a future edition of a NigE Dictionary;

determine the influences on the speakers’ pronunciation preferences.

This section has established the background to this study. Section 2 discusses Nigerian English and its sub-varieties while Section 3 explains the concept of free variation in English. In Section 4, the corpus and method used for the study are described while the results of the analysis are presented in Section 5. Discussion of findings and conclusion occupy Sections 5 and 6 respectively.

2. Nigerian English: Varieties and Norm Orientation

English was implanted in Nigeria through commerce, missionary activities and British colonisation and is today regarded as the country's official language of government administration, education, politics, mass media, law, science and technology, business and commerce. Besides, it is a lingua franca for the educated elite in a multilingual populace of an estimated 200 million people (Population Stat, Citation2019) and over 500 languages (Eberhard, Simmons & Fennig, 2019). As a result of its extended use and interaction with the indigenous languages, English has become nativised, varying markedly from native varieties of English, especially at the level of phonology. It is this domesticated variety that is now referred to as NigE.

NigE is not a monolithic variety but a conglomeration of different sub-varieties (Gut, Citation2004; Jibril, Citation1986) categorised according to geo-ethnic, social, educational and linguistic parameters (Brosnaham, Citation1958; Banjo, Citation1971, Citation1996; Jibril, 1982; Jowitt, Citation1991; Udofot, Citation2003; Adegbite et al., Citation2014). Geo-tribal studies have shown that NigE is divided along ethnic line, reflecting the influences or interference features of the indigenous languages (Adetugbo, Citation2009). A few acoustic studies on phonological variation in NigE have also established this. For example, while Dyrenko and Fuchs (Citation2018) confirm the tendency for the monophthongisation of some diphthongs amongst educated Yoruba speakers of English, Jamakovic and Fuchs (Citation2019) establish the previous impressionistic findings on the monophthong system of educated L1 Igbo English speakers.

Another important parameter for variation is the speakers’ level of education, which forms the basis of Brosnaham's (Citation1958), Banjo's (Citation1971) and Udofot's (2004) variation studies. For example, Udofot (Citation2003) proposes three varieties: Variety I (Non-Standard Variety), Variety II (Standard Variety) and Variety III (Sophisticated Variety). Speakers of Variety I are primary and secondary school certificate holders, some second year university undergraduates, holders of Nigeria Certificate in Education (NCE) and primary school teachers. Variety II is identified with third and final year undergraduates, university graduates, university and college lecturers, other professionals, secondary school teachers of English and holders of Higher National Diploma (HND). Variety III is spoken by university lecturers in English and linguistics who have a specialised training in English phonology, and speakers who have lived in English native-speaking countries. This study focuses on the exponents of Varieties II and III who are the categories of NigE speakers captured in the International Corpus of English (ICE)—Nigeria, which provides the data for this study (Adegbite, Citation2012).

The varieties of English spoken in Nigeria have been shaped by a combination of historical, geographical and sociolinguistic influences (Gut, Citation2004; Awonusi, 2015). Although NigE is primarily British-norm dependent, owing to its colonial history, it is also subject to the overwhelming influence of American English (AmE) due to the United States’ technological prowess and interaction with Nigeria at different levels (Gut, Citation2004; Jowitt, Citation1991, Citation2019). For example, Awonusi (Citation1994) identifies certain features of AmE pronunciation in NigE, which include yod dropping (student /stu:dənt/,), t-tapping (beautiful /bju:t̬əfəl/) and American-like stress patterns (ˈcigarette), and acknowledges a growing influence of the American accent, although he agrees that the BrE norm still holds sway. Similarly, Jowitt (Citation2019) points to the production of o as [ɑ] in, for example, God, and the realisation of post-vocalic r as [r] in Lord by some NigE speakers as influences of AmE, while agreeing with Awonusi (Citation1994) that the British Standard remains the dominant model. Obasi (Citation2019) equally shows that NigE speakers use the American pronunciation in such items as data (dætə) and food (fud) and contends that AmE is becoming the preferred form for many Nigerians.

Furthermore, Nigerians were exposed to other English accents (e.g. Irish and Scottish English) through the native and non-native teachers employed in different regions of the country during the colonial administration and through foreign traders, businessmen and professionals with different English accents who lived in Nigeria at the time (Gut, Citation2004). Added to the foregoing are the influences of indigenous Nigerian languages and culture and creative use of English by Nigerians (Jowitt, Citation2019).

It is in this respect that an investigation of variable pronunciations in NigE is considered worthwhile. Essentially, the paper will attempt to establish the pronunciation variants that could form part of a future edition of a NigE Dictionary and identify the influences on NigE speakers’ choice of variants. It is believed that this study will complement the scholarly efforts geared towards the codification and standardisation of NigE (Gut, Citation2012).

3. Phonological Free Variation

Phonological free variation is a phenomenon whereby a word can be pronounced in a number of different possible ways without a change in meaning. The choice of one form over another may depend on individuals or dialects. Variation may also occur at different levels of phonological analysis. At the phonemic level, for instance, economics may be pronounced as /ˌekəˈnɒmɪks/ or /ˌi:kəˈnɒmɪks/. It is also found more frequently between the allophones of the same phoneme; for instance, the final voiceless stop /p/ may be aspirated [mæph], unaspirated [mæpo] or glottalized [mæp?] without causing a meaning difference. Another instance of such allophonic free variation, according to Roach (2009), is the various realisations of the phoneme /r/ in different accents and styles as the post-alveolar approximant [ɹ], the tap [ɾ], the labio-dental approximant [υ], the trilled [r] and the uvular fricative [ʁ]. All these variants are heard and understood as the /r/ phoneme in English. Free variation can also occur in the stress patterns of a given word, for example, exquisite /ɪkˈskwɪzət/ or /ˈekskwɪzət/ and contribute /ˈkəntrɪbju:t/, /kənˈtrɪbju:t/ or /kɔntriˈbju:t/ (Akinola & Oladipupo, Citation2021; Henderson, Citation2010). Finally, variation may appear in the forms of assimilation, coalescence, elision or liaison, for example, good news as /gʊd nju:z/ or /gʊn nju:z/; would you? as /wʊd ju:/ or wʊdʒu:/; run along as /rʌn əlɒŋ/ or /rʌn lɒŋ/; near it as /nɪə ɪt/ or/nɪər ɪt/. However, the concern of this study is phonemic variability which is the alternation of two or more different phonemes in the same context in a given word (for example, direct pronounced as /dəˈrekt/, /dɪrekt/ or /daɪəˈrekt/) and the production or omission of a phoneme in a particular lexical context (e.g., often as /ɒftən/ or /ɒfən/).

The occurrence of phonological free variation in English can be traced to different sources, which include sound changes, accent variation, phonetic processes and sociolinguistic factors, amongst others (Cruttenden, Citation2014; Mompean, Citation2010). Sound changes relate to the diachronic and synchronic phonological transmutations of English, in the forms of sound shift, sound spilt and sound merger, which have yielded variants that now freely co-exist. For example, the pronunciation, in Received Pronunciation (RP), of the words resume as /rɪˈzju:m/ or /rɪˈzu:m/ and education as /edjʊˈkeɪʃən/ or /edʒʊˈkeɪʃən/ can be traced to diachronic evolution of yod processes in English (Augustine Simo Bobda, Citation1994; Cruttenden, Citation2014). Similarly, contemporary phonological changes in RP vowels are now yielding free variants, such as /ʃʊə/ or /ʃɔ:/ for sure, and /fɪə/ or /fi:/ for fear as a result of an increasing preference for /ɔ:/ and /i:/ over /ʊə/ and /ɪə/ respectively (Collins & Mees, Citation2013).

Variable realisation of sounds in native and non-native English accents is another explanation for this phenomenon. For instance, RP and General American (GA), often used for teaching-learning purposes in different English-as-a-second-language (ESL) contexts, have yielded free variants in different areas of the English speaking world, especially in ESL settings. Pronunciation of the words leisure as /ˈleʒə/ or /ˈli:ʒər/ and water as /wɔ:tə/, /wɒ:t̬ər/ or /wɑ:t̬ə/ can be traced to differences between both accents. This is in addition to other free variants in the ESL varieties which are products of contact between English and indigenous languages. Other relevant reasons for free variation are phonetic processes, such as assimilation, dissimilation, reduction, r-liaison, and so on, which are context dependent. For example, ten point may be pronounced as /ten pɔɪnts/ or /tem pɔɪnts/ and particular as /pǝtɪkələ/ or /prtɪkəlr̩. Finally, sociolinguistic factors, such as age, gender or ethnicity may also contribute to variable pronunciation, as younger speakers may prefer a particular variant to older speakers, just as male and female speakers may differ in their preference for sound variants (Wells, Citation1995).

Although cases of free variation are pervasive in English (Cruttenden, Citation2014), it is on record that considerable attention has not been paid to the concept, even in the native English varieties (Mompean, Citation2010). This, perhaps, is due to the notion that free variation is uncommon and tangential to linguistic theory (Sankoff, Citation1982). A few studies on this phenomenon include Gimsons (Citation1969)and more recent studies by Wells (Citation1995, Citation1999, Citation2003), Shitara (Citation1993), Henderson (Citation2010) and Mompean (Citation2010). These studies were conducted in native Englishes to verify speakers’ pronunciation preferences amongst different variants of a particular lexical set for the purposes of determining words of uncertain pronunciation, rectifying possible errors made by lexicographers and improving on dictionary entries (Wells, Citation2008). The present study attempts to extend such tendencies to an ESL context (Nigeria). Using the International Corpus of English (ICE)-Nigeria as a database, the paper examines 48 lexical items that are generally prone to phonemic variation in order to establish NigE speakers’ preferences. Cases of sound-spelling analogy (e.g., bomb /bɒm/ also pronounced as /bɒmb/) and phonological interference (e.g., realisation of the <th> grapheme as either [ð] or [d]), which are peculiar to the ESL varieties, are excluded. Besides, the variants must be lexical items with the same etymological derivations (for example, educate, education), meaning and pronunciation, which precludes homophones such as row /rəʊ/ (“to propel”) and row /raʊ/ (“a noisy argument”), and must be typical of the citation forms. Finally, the investigation does not include social variation, although it is germane to a study on pronunciation preferences. This is due to the absence of social predictors, such as gender, age, ethnic group and socioeconomic background, for a considerable number of ICE-Nig participants.

4. Corpus and method

Section 4.1 describes the corpus used for the study, while the method of analysis is discussed in detail in Section 4.2.

4.1. The Corpus

The International Corpus of English (ICE)—Nigeria, used for this study, was compiled between 2007 and 2014 at the Universities of Augsburg (2007–2011) and Münster (2011–2014) (see Gut 2014) as part of the ICE project (Greenbaum, 1991). It contains a total of 1,010,382-word corpus of spoken (609,586) and written (400,796) NigE usage in the early 21st century.

The corpus comprises different informal and formal spoken and written text categories, such as conversations, broadcast discussion, legal presentations, parliamentary debates, academic writings, student essays and social letters, amongst others. Being a research on pronunciation, the data for the present study were extracted from the spoken text categories in the corpus (see for the word count of each spoken text category). The choice of ICE-Nigeria as a database for this study is motivated by its wide coverage: participants are educated NigE speakers from different walks of life and linguistic backgrounds whose speech has been benchmarked for the description of Standard NigE (Adegbite et al., Citation2014).

Table 1. Word count of the spoken part of the ICE-Nig corpus

4.2. Method

This study adopts a descriptive research design, using survey method to empirically investigate NigE speakers’ pronunciation preferences. This approach is apt because it is capable of providing a quantitative description of trends, attitudes or opinions of a population sample which can be used to make inferences about the entire population (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2018). In this instance, the pronunciation trends of the participants in the corpus are used to determine what patterns exist in educated NigE. The survey is cross-sectional in nature because the compilation of the corpus spanned a period in time (between 2007 and 2014). One hundred and twenty-six lemmas (words with inflections and derivations) that typically exhibit free variation in English were sourced from Wells’ (2008) Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (LPD) and from previous works on variation in native Englishes (e.g., Mompean, Citation2010; Mompean, Citation2010; Wells, Citation1999). A search in the spoken part of ICE-Nig, using AntConc corpus analysis toolkit version 3.4.4.0 (Anthony, 2017), produced 70 lemmas, out of which 48 that occurred ten times and more were eventually considered for analysis in order to ensure a fair representation of each item (see the final list in ). The audio clips of the texts which contain the lexical items were then selected and listened to by the researchers, who are both Nigerian L2 speakers of English and trained phonologists. Each listened to the audio clips independently and transcribed the variants produced, after which the findings were compared. A few cases of disagreement (in issue, associate, attitude, congratulation, situation, educate and virtue) were resolved by jointly listening to the disputed audio clips, and where it was difficult to reach a consensus, the opinion of another trained phonologist was sought. The raw data and the sounds produced by each speaker in each lexical item were later uploaded on the Open Science Framework website (see http://osf.io/9qmfx).

Table 2. Lexical items in phonemic variation

The transcription system in LPD (Wells, Citation2008) was used to represent the native English phonemes while the inventories of NigE phonemes proposed by Adetugbo (Citation2009) were adopted for the transcription of NigE pronunciation (see for a list of the major areas of differences between the two sound systems). Adetugbo’s model was chosen because it succinctly captures the major distinctions between RP and NigE phonemes in relation to tense and lax vowel mergers, absence of central vowels, monophthongization of diphthongs, phonemic substitution and under-differentiation.

Table 3. Phonemic correspondences between RP and NigE

The data were analysed using descriptive statistics (frequency counts and percentage distribution presented on tables). In order to establish the preferred pronunciation of a particular item, the rates of occurrences of the variants and the speakers that produced them were counted and converted to percentages; the variant with the higher (or highest) percentage of occurrences and speakers was then taken as the norm. In a situation of intra-speaker variation, where the same speaker pronounces different variants of a lexical item, the number of times that such variation occurs is indicated as a superscript above the total number of speakers (see 2).

5. Results

For the purpose of analysis, the data are presented under four different categories (see 3), following Mompean (Citation2010). show different possible native English pronunciations for each lexical item as indicated in Wells’ (2008) LPD, the variants adopted by NigE speakers, the rates of occurrences and speakers and their percentages (in parenthesis). Only the base form of each item is listed in the tables since all the lemmas have the same set of variants. For instance, FINANCE comprises finance, finances, financed, financial and financially (see ). While presenting the data, attempts are made to relate the findings to pronunciation preference polls in native Englishes (Wells, 1988, 1998; Shitara, Citation1993), as reported in LPD (Wells, Citation2008), and to Mompeans (Citation2010) study on phonological free variation.

Table 4. Grouping of lexical items

Table 5. Variation due to alternation between short vowels and diphthongs

Table 6. Variation due to alternation between long vowels and diphthongs

Table 7. Variation due to assimilation

Table 8 . Variation due to reduction

Table 9. Variation due to sound-spelling correspondences (consonants)

Table 10. Variation due to sound - spelling correspondences (vowels)

5.1. Alternation between monophthongs and diphthongs

The free variants analysed in this section are products of the choices made in a particular word between monophthongs and diphthongs. For analysis purposes, the affected lemmas are sub-categorised into alternations between short vowels and diphthongs (e.g., /ænti/ and æntaɪ/) and between long vowels and diphthongs (e.g., /ɑ:men/ and /eɪmen/). The results are presented in and respectively.

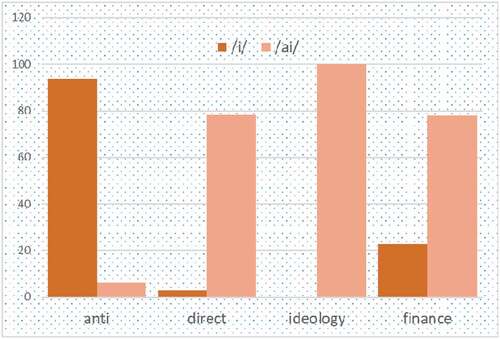

As seen in , anti- and ideology have two variants (/i/ and /aɪ/) in their final and initial syllables respectively, while /ɪ/, /aɪ/ and /ə/ are the possible variants for both direct and finance; /aɪə/ may also be heard in direct in BrE. NigE speakers’ pronunciations show that, in anti-, 15 out of 16 speakers, representing 93.8%, in 21 of the 24 cases (87.5%) pronounced the short vowel /i/. This suggests that the speakers overwhelmingly preferred /i/ in anti, which is the only variant in BrE, to the diphthong /aɪ/ which is one of the AmE variants. As a matter of fact, the 3 tokens (12.5%) of /aɪ/ are idiosyncratic pronunciations of a single speaker. Neither the LPD nor previous studies have comparable preference data for anti. On the other hand, the diphthong /ai/ was the sole form pronounced by all the speakers in the 17 cases of ideology, which is also the preferred variant for 64% of AmE speakers and 90% of BrE speakers (Wells, Citation2008).

The /ai/ vowel was also preferred in direct and finance (see ). In direct, 78.1% of the speakers in 84.4% of all the cases pronounced /ai/, which is also the main pronunciation in BrE according to LPD (Wells, Citation2008). Mompean (Citation2010) also reveals this as the speakers’ preferred form in direct (55%), directly (61%), director (55%). It is, however, different from the AmE preference /ə/ for direct (78%). This establishes the NigE affinity with BrE, which is its target model. The same variant /ai/ was also overwhelmingly favoured in finance by 77.8% of the speakers in 70.9% cases, which is in tandem with the preference poll of 79% recorded for financial in LPD (Wells, Citation2008), 100% for finance and 76% for financial in Mompean (Citation2010).

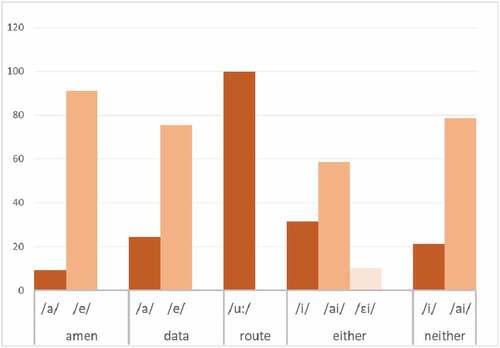

Variation in amen occurs in the first syllable where the vowel is either pronounced as /ɑ:/ or /eɪ/ (usually realised as /a/ or monothongised /e/ respectively in NigE). As illustrated in (see also ), 91% of speakers in 96.1% of all the occurrences of amen produced the variant /e/ (/eɪ/) while the only token of the /a/ (/ɑ:/) variant was an idiosyncratic production of a single speaker. This establishes the preference of NigE speakers for /e/ in the first syllable of amen. This is at variance with the entry in LPD (Wells, Citation2008) which shows /ɑ:men/ as the main pronunciation variant for BrE and AmE speakers. However, the same source also claims that /eɪmen/ is predominant among the Roman Catholics and in non-religious contexts in Britain as well as in American speech, while /ɑ:men/ is preferred by the British Protestants and in singing in AmE. The bias of NigE speakers for /e/ in the same word, therefore, is, perhaps, a preference that has developed locally through interactions with both native varieties.

In the case of data which has variants /ɑ:/, /æ/, and /eɪ/ in the first syllable, shows that monophthongised /e/ is also the most common variant in NigE with 79.2% of speakers in 75.6% of all cases. This correlates with the BrE and AmE preferences of 92% and 64% respectively for /eɪ/ (Wells, Citation2008). The items either and neither contain the variants /i:/ and /aɪ/ (realised as /ai/ in NigE). In either, 58.6% of the speakers produced the diphthong /ai/ in 61.1% of all the occurrences, while 78.6% of the speakers in 68.7% of all the instances produced the same sound in neither. This implies that NigE speakers preferred the diphthong /ai/ in both words, which is in consonance with the BrE speakers’ poll preference for the diphthong /aɪ/ (88%) in either and neither (Wells, Citation2008). On the other hand, the same source reveals that 84% informants preferred the variant /i:/ in AmE. This, again, confirms the influence of BrE on NigE. However, a peculiar variant /ɛi/ was pronounced by 7 speakers in 10 cases, which can be regarded as an instance of spelling-cued mispronunciation attested in NigE (Akinjobi, Citation2013). All the speakers in all the instances of occurrence pronounced /u/ in route, which is the main variant in both native varieties, rather than /aʊ/. The LPD (Wells, Citation2008) also reveals the choice of the same variant by 68% of the American informants while no poll data was available for BrE.

5.2. Phonetic Factors

Two of the phonetic processes that have resulted in variation in English are examined in this section: assimilation and reduction. Assimilation is a process whereby a phoneme occurring in an environment is modified to take up the quality of an adjacent sound segment; for example, /s/ in the antepenultimate and penultimate syllables of associate and association respectively may sound like the preceding /s/. On the other hand, in reduction, the number of syllables or consonant cluster in a word is reduced for ease of articulation, as in medicine and often which may be compressed to /medsən/ and /ɒfən/ respectively. Associate and association, though belong to the same word family, were split when it was discovered that they were realized differently in the NigE data.

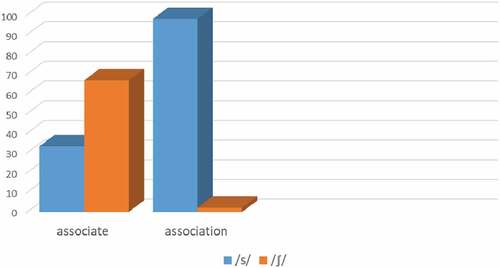

In regard to associate and its inflections which may be produced as /s/ or /∫/, and show that 66.7% of the speakers in 69.6% of all the cases preferred the voiceless palato-alveolar fricative /∫/ in associate; whereas 97.9% of the speakers in 86.6% of all the instances preferred the voiceless alveolar fricative /s/ in association. As a matter of fact, the 18 (13.4%) tokens of /∫/ in association was produced by only one speaker.

The overwhelming preference for the assimilated /s/ variant in association conforms to Mompean's (Citation2010) rate of 100% and LPD's (Wells, Citation2008) preference poll of 78% for the British informants in the same word, which is also the main variant in AmE. However, while the present study reveals NigE speakers’ preference for variant /∫/ in associate, results from LPD (Wells, Citation2008) and Mompean (Citation2010) respectively show 69% and 92% preferences for the variant /s/ in BrE. The NigE preferred variant, thus, agrees with the AmE main pronunciation.

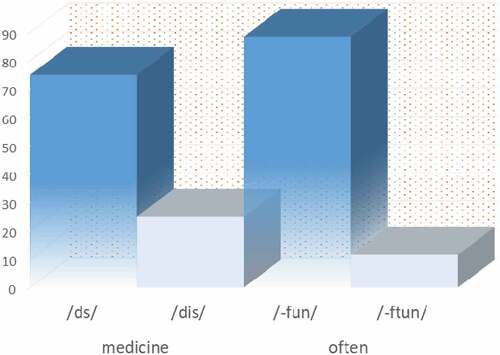

The second syllable of medicine has three pronunciation forms: /dɪ/, /də/ or /d/. When pronounced without a vowel, the trisyllabic word, medicine, is compressed to two syllables. shows that the disyllabic variant, /mɛdsin/, was preferred by 75% of NigE speakers in 86.6% of all the occurrences, which conforms to Mompeans (Citation2010) 67% score for BrE speakers. Also, two pronunciations of often exist: with or without the consonant /t/. The variant without a /t/ results in consonant cluster reduction. 8 indicates that 88.5% of the speakers in 90.2% of the instances preferred the reduced variant /ɔfun/. This is similar to the finding of Shitara (Citation1993) which reveals that 78% and 73% of speakers from both AmE and BrE respectively preferred /ɒfən/.

The results suggest that NigE speakers showed a preference for the reduced variants of both lexical items (see ). This is quite unlike the predisposition, in NigE, to realise all the syllables or consonant clusters in some words that are typically reduced in native Englishes; for example, chocholate /ʧokolet/, police /polis/, listen /listin/ and castle /kastul/. Therefore, as Simo Bobda (Citation1994) observes, it may be that the pronunciation of the reduced variants of medicine and often has been lexicalised, that is, established historically as the norm in NigE.

5.3. Sound-Spelling Correspondences

In this section, we examine lexical items which contain a particular grapheme or graphemes that can be pronounced in more than one way due to sound-to-spelling correspondences in English. In 5.3.1, we examine items involving consonants while those that concern vowels are investigated in 5.3.2.

5.3.1. Variation Involving Consonants

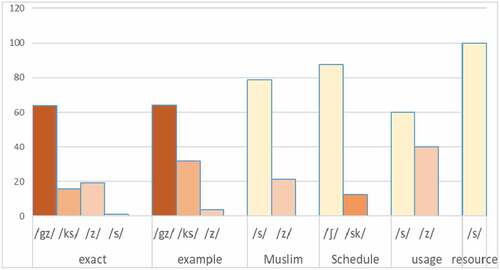

Items discussed in this subsection are exact and example (which contain grapheme x with two variants of biphonemic consonant clusters—/ks/ and /gz/—at the initial syllable), Muslim and usage (with the grapheme s at the onset of the final syllable, which may be realized as /s/ or /z/), and schedule (which has grapheme sch at the initial syllable and may be pronounced as /ʃ/ or /sk/).

and show that NigE speakers preferred the biphonemic consonant cluster /gz/ in exact and example, as 63.9% of the speakers in 72.2% of all the cases produced it in exact and 64% of the speakers in 65.8% of all the occurrences produced the same variant in example. Although no poll results or findings from previous studies were available for the items, the entries for both words in Wells’ (2008) LPD reveal that the /gz/ variant is preferred by BrE and AmE speakers. Besides, the consonant cluster was reduced to /z/ by 16 (19.3%) and 3 (4%) speakers respectively in exact and example, which points to the claim that NigE speakers have a tendency to simplify complex syllable structure of native Englishes by deletion (Akinjobi, Citation2010; Simo Bobda, Citation2007).

In Muslim and usage 78.6% of the speakers in 69.5% cases and 60% of the speakers in 82.4% of all the instances respectively preferred variant /s/. The same sound /s/ was also produced in resource by all the speakers. The preference for the voiceless fricative /s/ in usage is in tandem with the BrE preference poll result of 72% (Wells, Citation2008) for the same lexical item. By contrast, the choice of /s/ in Muslim is at variance with the record of 89% preference for /z/ by BrE speakers both in Mompean (Citation2010) and LPD (Wells, Citation2008) and with the LPD's entry for resource. For schedule, 86.8% of the speakers in 82.4% of all the cases produced the voiceless palato-alveolar fricative /∫/ instead of the biphonemic cluster /sk/. This is similar to Mompeans (Citation2010) and LPD (Wells, Citation2008) which show 80% and 70% preferences respectively for the variant /∫/ by the BrE speakers. On the other hand, the biphonemic consonant cluster /sk/ is considered the typical AmE pronunciation variant (Wells, Citation2008). Thus, NigE speakers’ preference for /∫/, one again, demonstrates their affinity with the BrE accent.

5.3.2. Variation Involving Vowels

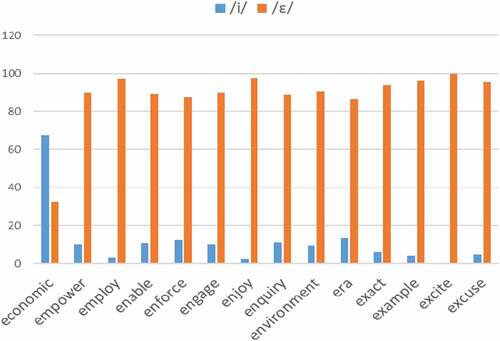

The items examined have vowel variants /ɪ/, /i:/, /ɪə/, /e/ or /ə/ (rendered as /i/ or /ɛ/ in NigE) in the initial syllable; these are economic, employ, enable, enforce, enough, era, environment, exact, example and excuse. Also included are Muslim which may be pronounced with vowel /ʊ/, /u:/ or /ʌ/ and barrister with vowel variants /æ/ or /e/ in the initial syllable.

shows that /ɛ/ (/e/) was predominantly preferred by NigE speakers in most words with vowel variants /ɪ/, /i:/, /ɪə/, /e/ or /ə/ (see also ). Ninety per cent of the speakers in 93.3% tokens produced /ɛ/ in empower. In enable, 89.3% of the speakers in 85.7% of all the cases also produced /ɛ/ while 87.5% of the speakers in 84.2% of all the instances pronounced the same variant in enforce. Ninety per cent of the speakers pronounced /ɛ/ in 90.6% tokens of engage, 97.6% did in 98.5% cases of enjoy and 97.1% did same in 98% items of employ. In enquiry and environment respectively, /ɛ/ was produced by 88.9% of the speakers in 92.9% of the cases and 90.4% of the speakers in 86% of the tokens. The variant /ɛ/ was also produced by 86.7% of the speakers in 88.9% instances in era; by 93.8% of the speakers in 92.3% cases in exact and 96% of the speakers in 96.7% instances in example. All the speakers pronounced /ɛ/ in all the instances of excite while 95.5% of the speakers in 96.4% did in excuse. The choice of /ɛ/ in all these words differs from what obtains in BrE and AmE. Although there are no comparable data for them in the previous studies, entries in LPD (Wells, Citation2008) show that, in most cases, the variant /ɪ/ is the norm. The preference for /ɛ/ in the data may be as a result of NigE speakers’ reported penchant for spelling-induced pronunciation (see Adetugbo, Citation2009; Akinjobi, Citation2013; Jowitt, Citation2019). Since all the words begin with the letter e, there is a strong tendency to pronounce them like /ɛ/ in egg, leg, ebb, bed, and so on, as suggested by spelling.

On the other hand, NigE speakers preferred the variant /i/ to /ɛ/ in two words: economics and enough. About 67.6% of the speakers produced /i/ in 63.9% of all the instances of economics, which compares with the BrE preference poll of 62% in LPD (Wells, Citation2008). The preference for /i/ in enough was, however, not overwhelming; 50.5% of the speakers in 53.3% of the tokens did, which means that a substantial number of speakers also preferred the /ɛ/ variant. In barrister, which has variants /æ/ (/a/ in NigE phonemic system) or /e/, all the speakers produced /a/ in all the instances; while 92.9% of the speakers preferred /u/ in 97.6% of the cases of Muslim with variants /ʊ/ (u in NigE), /u:/, /ʌ/ or /ɔ/. The preference for /ʊ/ in Muslim agrees with Mompean (Citation2010) and the pronunciation poll in LPD (Wells, Citation2008) in which 100% and 70% of the BrE speakers respectively produced /ʊ/. It is obvious from the foregoing that NigE speakers’ pronunciation of these words are guided by spelling.

5.4. Sound changes

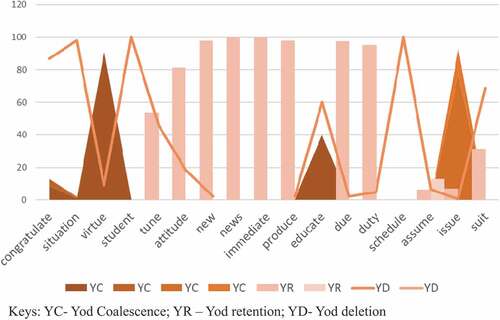

In this section, we examine free variants that emerged in the course of the evolution of the English language. Altogether, eleven lexical items with such variable pronunciations were investigated. They were categorized according to the manner of sound change: yod retention, yod dropping and yod coalescence. In yod retention, /j/ is produced in all contexts of /Cju/ (consonant + /j/ + /u/) sequence of English words; it is elided in the same environment in yod deletion and merges with the alveolar sounds /s, z, t, d/ to become palato-alveolar /∫, ʒ, ʧ, ʤ/ respectively in yod coalescence (Simo Bobda, Citation1994). lists the items that exhibit variations in this manner.

and demonstrate NigE speakers’ preference for yod dropping in certain items such as congratulate, situation, educate, assume, suit, schedule and student. In congratulate, with native variants /ʧu/, /tju/ and /ʤə/, 87% of the speakers in 89.7% of the occurrences dropped yod and pronounced /tu/, a distinctive NigE variant. This is different from the yod coalescence variants /ʧu/ and /ʤə/ which are preferred in the same word in BrE and AmE respectively (Shitara, Citation1993; Wells, Citation2008).

Table 11. Variation due to sound changes

Situation contains variants /ʧu/, /tju/ and /tu/ in the native varieties. The result shows that 98% of NigE speakers in 98.5% of all the cases preferred the variant /tu/ which, according to Wells (Citation2008), is a non-RP variant favoured by 1% of educated BrE speakers. This differs from the yod retention variant /tju/ which the same source says is preferred by 64% of the BrE respondents and the yod coalescence variant /ʧu/ which Mompean (Citation2010) found was favoured by 78% of the BrE speakers. There are three native variants: /dju/, /ʤu/ and /ʤə/ for educate. Again, 60.2% of the educated NigE speakers produced /du/ in 68.3% of all the instances of the item, which is different from the yod retention form /dju/ and the coalesced variant /ʤə/ which Wells (Citation2008) provides as the main pronunciations in BrE and AmE respectively. It does appear also that the coalesced form is on the rise in NigE as about 40% of the speakers opted for it.

In assume and suit NigE speakers, again, demonstrated a tendency for yod dropping. About 74.1% of the speakers in 76.2% of all the cases of assume, in addition to dropping yod, also voiced /s/ and pronounced a peculiarly NigE variant /zu/, possibly due to analogy with presume in which “s” is traditionally articulated as /z/. This differs from the preference for /sju:/ by 84% of the BrE speakers and /su:/ which is the main form in AmE (Wells, Citation2008). In suit, 68.7% of the speakers in 68.2% of all the occurrences produced variant /su/, which Wells (Citation2008) reveals is the choice of 72% of the BrE speakers and the default pronunciation in AmE. The phenomenon was also obvious in schedule and student where all the speakers in all the instances of both items produced /du:/ and /tu:/ respectively. While the pronunciation of schedule is different from what obtains in BrE and AmE where the /dju:/ and the /ʤu:/ variants respectively are the norm, that of student conforms with the form that 88% of the AmE speakers prefer (Well, 2008). The NigE speakers’ predilection for yod dropping evidenced in the above words corroborates previous findings which established yod coalescence as a minor process that is barely attested in NigE (Oladipupo, Citation2014) on the one hand, and the presence of yod dropping as an influence of AmE on NigE on the other (Awonusi, Citation1994; Ogbulogo, Citation2005).

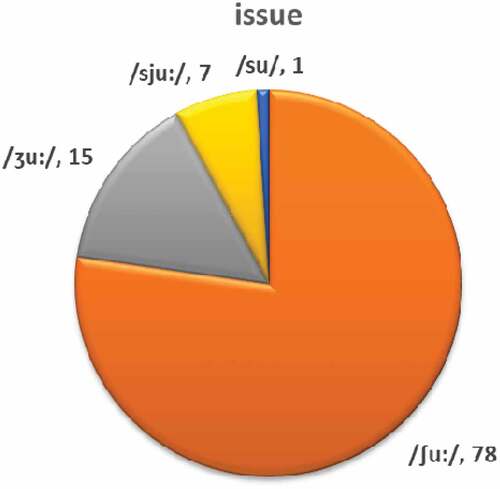

However, the coalesced variant was not completely jettisoned by NigE speakers, as the form was preferred in two words: issue and virtue 9 (see ). Out of the three native variants of issue: /sju:/ /∫u:/, and /∫ju:/, the coalesced variant /∫u/ was preferred by 77.5% of the speakers in 80% of all the cases. This is similar to the preferences of the AmE and the BrE respondents in LPD (Wells, Citation2008). A peculiar variant /ʒu/ was also produced by 15% of the NigE speakers in 13.2% of all the occurrences of issue, perhaps, due to hyper-correction. Again, 90.9% of the speakers in 91.7% of all the cases produced the coalesced form /ʧu/ in virtue. Although no previous poll results are available for the AmE and BrE pronunciation preferences, Wells (Citation2008) reveals /ʧu:/ as the preferred form for both varieties.

further shows that the speakers retained yod in attitude, tune, produce, due, duty, new, news, and immediate. The results of attitude and tune, with variants /tju:/, /tu:/ and /ʧu:/ in both native English varieties, show that 81.5% of NigE speakers produced the variant /tju/ in 82.5% of all the occurrences of attitude while 53.8% did same in 60.9% of all the cases of tune. The LPD (Wells, Citation2008) confirms the same variant as the preferred form in BrE, while the yod-dropping variant /tu:/ is pronounced in AmE. In produce, due and duty with the variants /dju:/, /ʤu:/ and /du:/, the most common variant is /dju/, which was pronounced by 97.9% of the speakers in 96.3% of all the instances of produce, 97.7% of the speakers in 76.5% of all the cases of due and 95.2% of the speakers in 92.3% of all the tokens of duty. These results agree with Wells (Citation2008), that shows /dju:/ as the main variant in BrE, and Mompeans (Citation2010) finding that the variant was preferred by 70% of all the BrE speakers in 60% of all the instances of produce. Finally, yod was again retained by 97.8% of the NigE speakers in 98.8% of the tokens of new and by all the speakers in all the instances of news. This conforms with Wells’ (2008) record which reveals the variant as the BrE main pronunciation, but differs from Shitaras (Citation1993) which shows that 86% of the AmE respondents preferred the yod dropping variant /nu:/. The above results generally show that the yod retention form of the BrE variety remains the preference of NigE speakers. Essentially, the results confirm the affinity of NigE usage with the BrE variety.

6. Discussion

The results have revealed variable pronunciations of a number of English words examined in this study, which suggests the prevalence of phonological free variants in NigE as in other well-described native varieties, such as BrE and AmE. A number of these variants correspond to the native English forms while a few others are distinctive Nigerian English usages. For example, the grapheme <c> in associate has exactly the same set of variants /s/ and /∫/ as in the native varieties; whereas, the variants of <ss> in issue are divergent: /sju/ and /∫u/ correspond to the native English /sju:/ and /∫u:/, differing only phonetically, while /ʒu/ and /s/ are distinctive NigE variants.

The study further established NigE pronunciation preferences, such that a main or primary pronunciation can be distinguished from secondary or idiosyncratic variants. A primary pronunciation is a form that has the higher or highest rate of speakers and occurrences. This is the form that may be recommended for the candidacy of endonormative standard NigE, being more frequently used by a majority of educated speakers. This includes such variants as data /deta/, neither /naiða/, Muslim /muslim/, direct /dairɛkt/, finance /fainans/, associate /asoʃiet/, medicine /medsin/, environment /ɛnvaromɛnt/, often /ɔfun/, engage /ɛngeʤ/, attitude /atitjud/, assume /azum/ and issue /i∫u/ (see for a comprehensive list). Secondary variants are forms that are also in use in NigE but not as frequent as primary pronunciations. Included in this category are data /data/, neither /niða/, Muslim /muzlim/, direct /dirɛkt/, finance /finans/, associate /asosiet/, medicine /medisin/, environment /invaromɛnt/, often /ɔftun/, engage /ingeʤ/, attitude /atitud/, assume /azjum, sju, su/ and issue /iʒu, isju/ (see ). An idiosyncratic pronunciation is a variant that is peculiar to a single speaker. Examples include exact /ɛsat/, excuse /iskjus/, empower /impawa/, employ /implɔi/, congratulate /kɔngraʤulet/, situation /siʧueʃɔn, siʃueʃɔn/, produce /produs/, virtue /vɛtu/, issue /isu/, due /du/, amen /amɛn/, anti- /antai/, association /aso∫ie∫ɔn/ and enquiry /inkwari/. While both primary and secondary variants are listed as NigE pronunciation variants, idiosyncratic variants are not, although some of them are Standard native English pronunciations. This is because they are peculiar individual pronunciation variants.

Table 12. NigE, BrE and AmE pronunciation preferences

With regard to the influences on the speakers’ pronunciations, NigE preferences can be said to be conditioned by both the exoglossic (BrE and AmE) varieties and the domesticated NigE accent. For instance, three pronunciation variants were observed in assume: RP primary pronunciation /əsju:m/, GA main variant /əsu:m/ and a typical NigE variant /azum/. The same scenario occurred in issue: /ɪsju:/ (an RP secondary variant), /ɪ∫u:/ (both RP and GA primary variant) and /ɪʒu/ (a distinctive NigE usage). It follows, therefore, that the interplay of these accents exacts considerable influence on the speakers’ pronunciations. For instance, in assume and issue discussed above, a majority of the speakers preferred the NigE form /azum/, while they predominantly adopted /ɪ∫u/ (RP and GA primary variant).

Talking, specifically, about the exoglossic influence, both the BrE and AmE varieties have so much impacted NigE (Awonusi, Citation1994; Umar, Citation2015) that speakers often swing between the two accents unconsciously (Obasi, Citation2019). For example, as shown in Table , only one pronunciation of era /ɪərə/ exists in BrE while AmE has two variants /ɪrə/ and /erə/; participants in the study predominantly showed a preference for one of the AmE variants /erə/. On the other hand, they preferred the BrE pronunciation form of new /nju:/ to the AmE form /nu:/, while they favoured /detə/ data, which is the main variant in both native varieties. This position is also validated by the fact that some speakers exhibited intra-speaker variation in their pronunciation of certain lexical items in the corpus. This was observed in the cases of association, assume, data, direct, due, duty, economic, educate, enable, enough, exact, issue, Muslim, tune and virtue. For example, a speaker in con_53 pronounced assume as /asum/ at one time and as /azum/ at another time, educate was pronounced by a speaker in unsp_10 as /eduket/ and eʤuket/ on different occasions, while another speaker in con_67 rendered issue as /i∫u/ and /iʒu/ twice each.

The influence of BrE on NigE usage cannot be dissociated from colonisation which eventually led to the adoption of the BrE model in Nigerian educational institutions. Also, harmonious interactions between Nigeria and the USA in different areas—politics, business, technology, entertainment and education—have contributed, in no small measure, to the Americanization of NigE (Awonusi, Citation1994; Ogbulogo, Citation2005). Notwithstanding the incursion of AmE into the Nigerian linguistic landscape, this study agrees with Awonusi (Citation1994) and Jowitt (Citation2019) that the BrE variety still wields enormous influence on the NigE accent. As the findings have shown, participants shared more primary variants in common with BrE (e.g., /daɪrekt, faɪnəns, aɪðə, naɪðə, medsin, ∫edju:l, nju:, nju:z, prəʊdju:s, dju:, dju:ti, bærɪstə/) than with AmE (/aso∫iet, risɔ:s) (see Table ). This trend is likely to continue as long as educational policies are skewed in favour of the BrE variety.

In addition to revealing the exonormative influence on NigE, the findings also validate the ongoing nativisation of English in Nigeria. This is evidenced by the distinctive NigE pronunciation variants (e.g., assume /azum/, issue /ɪʒu/, congratulate /kɔngratulet/, educate /ɛduket/, and schedule /∫ɛdul/) and some features of NigE authenticated in this study. These features include spelling-induced pronunciation, phonemic under-differentiation, substitution, monophthongisation of diphthongs, widespread yod deletion, absence of yod coalescence and non-obscuration of syllabic consonants, amongst others. In regard to spelling-induced pronunciation, existing studies (e.g., Akinjobi, Citation2013; Gut, Citation2004; Jowitt, Citation2019; Oladipupo & Akinola, Citation2019; Soneye, Citation2008) have asserted that NigE pronunciations tend towards grapheme-phoneme correspondences. This claim was attested in the articulation of variant /ɛ/ rather than /i/ in the first letters of enable /ɛnebul/, example /ɛgzampul/, enforce, /ɛnfɔs/ and employ /emplɔi/, and variant /s/ rather than /z/ in Muslim /muslim/, which was probably guided by graphological representations. Cases of phonemic under-differentiation (Adetugbo, Citation2009; Awonusi, Citation2009) manifested in the mergers of tense and lax vowels whereby long vowels /ɑ:, i:, u:/ were respectively pronounced as short vowels /a/ (in data /data/, amen /emen/), /i/ (in either /iða/, economics /ikɔnɔmik/) and /u/ (e.g., new /nju/, virtue /vɛʧu). Substitution occurred in the speakers’ replacement of the schwa /ə/ with /e/ in immediate (/imidiet/ for /ɪmi:diət/), while the monothongisation of RP diphthong /eɪ/ to /e/ was observed in /deta/ for /deɪtə/, /emen/ for /eɪmen/). Widespread yod deletion, as Simo Bobda (Citation2007) observes, was seen in such items as congratulate /kɔngratulet/, situation /situe∫ɔn/, education /ɛduke∫ɔn/ and schedule /∫ɛdul/. Finally, it is obvious from this study that syllabic consonants are hardly obscured in NigE as demonstrated in the pronunciation of often, enable and example as /ɒfun/, /ɛnebul/ and /ɛgzampul/. All these features exert a strong influence on NigE speakers’ pronunciation preferences.

7. Conclusion

This paper employed corpus analytical tools to empirically survey variable pronunciations of 48 English lexical items with their inflections and derivations by educated NigE speakers. The goals were (i) to identify speakers’ pronunciation preferences that could be codified in form of a NigE dictionary or other refence materials that could lead to the emergence of endonormative pronunciation standards to be used in educational institutions, and (ii) to determine the influences on their choices. The study established phonemic variability as a widespread phenomenon in NigE and categorised the identified variants as primary, secondary and idiosyncratic pronunciations (see Table ). The primary pronunciation, in view of its prevalence amongst NigE speakers, is proposed as a possible candidate of endonormative standard NigE while secondary pronunciations are regarded as acceptable variants. Idiosyncratic pronunciations, on the other hand, are unacceptable. The findings further show that these variations are conditioned by a combination of exonormative and endonormative forces (Dyrenko & Fuchs, Citation2018), which points to the interplay of two standardising realities in NigE usage: the exoglossic BrE or AmE Standard and “developing, distinctively Nigerian ‘standard’” respectively (Jowitt, Citation2019: 32). This study therefore submits that, although NigE is largely influenced by the exoglossic Standard varieties, it is undergoing critical norm development (typical NigE usage documented here and in previous studies) which deserves to be codified in order to achieve endonormative stabilisation as proposed by Schneider (2007). Following Schneider's (2007) Dynamic Model of the development of New Englishes, NigE is said to currently lie between late nativisation phase and early endornormative stabilisation phase (Collins, Citation2020; Gut, Citation2012), marked by the emergence of some local linguistic usage due to the indigenisation of the structure of the English language and the gradual adoption and acceptance of the local norm in formal contexts. It is in light of this that the present study reinforces the agitation for the codification and standardisation of NigE so as to rightly position the variety in the comity of World Englishes.

As an important step towards codification, therefore, these findings provide valuable resources for a future edition of a NigE dictionary which, according to Bamgbose (1998), is germane to endonormative standardisation. Patterned after Wells’ (2008) Longman Pronunciation Dictionary, which was influenced by Shitara's (Citation1993) survey of American pronunciation preferences, and BrE 1988, 1998 and 2007 poll panel preferences (Wells, Citation2008), the proposed edition of NigE Dictionary would include NigE speakers’ pronunciation preference polls and charts in addition to other entries. One of the lexical items examined in this study—issue—is hereby used to demonstrate the proposal in comparison with an existing Dictionary of NigE (e.g., Adegbite et al., Citation2014).

An existing Dictionary of Nigerian English (Adegbite et al., Citation2014)

This dictionary contains such entries as pronunciation, tone, word class, synonyms and usage for issue in NigE.

issue /i∫u/, /i∫ju/ HL, n., children, progeny: “They have been married for many years but have no issues.” “A man without a male issue cannot be happy.”

The proposed edition of NigE Dictionary

In addition to the existing entries, pronunciation preference poll and chart (see ) for issue, showing the NigE variants according to the degree of preference, would be included in the dictionary.

issue /i∫u:, iʒu, isju, isu/

- Preference poll - /∫u/- 78%, /ʒu/- 15%, /sju/- 7%, /su/- 1%

It is hoped that this addition, rooted in empirical studies, will stem the tide of generalisation and assumptions and provide a clear picture of pronunciation preferences of educated NigE speakers. As can be seen in issue above, /i∫ju/ which Adegbite et al. (Citation2014) regard as a NigE variant was not attested in this study; whereas /iʒu/ and /isju/ were produced by speakers as shown in .

In concluding, it must be stated that this study has some limitations. First is its concentration on lexical items that typically exhibit free variation in native Englishes. Second is the small size of ICE-Nig which yielded only a few variable English words. While so many of these lexical items were not found in ICE-Nig, some with fewer occurrences were discarded. Furthermore, participants’ information which could have provided data for the variational analysis of the speakers’ preferences is absent for a number of speakers in ICE-Nig. It will be more enterprising and illuminating, therefore, to conduct a field-based experimental study that captures lexical items which typically exhibit variation, not only in native Englishes but also in NigE, and examine their social distribution.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Rotimi Oladipupo

This paper is a product of the research activities of the Phonology Research Cluster in Redeemer’s University, Nigeria whose goal is to develop a framework for the codification and standardisation of Nigerian English. It investigates phonological variability of English lexical items in Nigerian English and proposes the findings as essential and authentic resources for a future edition of a Nigerian English pronunciation dictionary, which is germane for the standardisation of the Nigerian English variety. Rotimi Oladipupo, the Head of the Cluster, specialises in (socio)phonetics, corpus linguistics and Nigerian English usage, while Aderonke Akinola’s research interests lie in corpus phonology, applied linguistics and sociophonetics.

References

- Adegbija, E. (2004). The domestication of English in Nigeria. In V. Awonusi & E. Babalola (Eds.), The Domestication of English in Nigeria. A Festschrift in Honour of Abiodun Adetugbo (pp. 20–25). University of Lagos Press.

- Adegbite, A. (2012). The ICE Nigeria corpus as a data base for Nigerian English studies. ISEL, 10(1), 1–10.

- Adegbite, A., Udofot, I., & Ayoola, K. (eds.). (2014). A Dictionary of Nigerian English Usage. Obafemi Awolowo University Press.

- Ademola-Adeoye, F. (2019). The changing face of Nigerian English pronunciation: A study of selected undergraduates of University of Lagos. In A. Akinjobi & A. Atolagbe (Eds.), English Phonology in a Non-native Speaker Environment: Theory, Practice and Analysis (pp. 15–44). Pumark Nigerian Limited.

- Adetugbo, A. (2009). Problems of standardization and Nigerian English phonology. In A. B. K. Dadzie & V. Awonusi (Eds.), Nigerian English: Influences and Characteristics (pp. 79–199). Sam Iroanusi Pulications.

- Akinjobi, A. (2010). Consonant cluster simplification by deletion in Nigerian English. Ibadan Journal of English Studies, 6, 27–38.

- Akinjobi, A. (2013). Spelling cued mispronunciation in Nigerian English. Papers in English and Linguistics, 9, 18–30.

- Akinola, A., & Oladipupo, R. (2021). Word-stress free variation in Nigerian English: A corpus-based study. English Today, 1–13. first view.

- Awonusi, V. (1994). The Americanization of Nigerian English. World Englishes, 13(1), 75–82.

- Awonusi, V. (2009). Some characteristics of Nigerian English phonology. In A. B. K. Dadzie & V. Awonusi (Eds.), Nigerian English: Influences and Characteristics (pp. 203–241). Sam Iroanusi Pulications.

- Banjo, A. 1971. Towards a definition of standard Nigerian spoken English. Proceedings of the 8th Congress of West African Languages Abidjan, University of Abidjan, 165–175.

- Banjo, A. (1996). Making a virtue of necessity: an overview of the English language in Nigeria. Ibadan University Press.

- Brosnaham, L. (1958). English in southern Nigeria. English Studies, 39(3), 97–110.

- Collins, P. (2020). Comment markers in world Englishes. World Englishes Early View https://doi.org/10.1111/weng.12523

- Collins, B., & Mees, I. (2013). Practical Phonetics and Phonology. Routledge.

- Creswell, J., & Creswell, D. (2018). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches (5th ed.). Sage.

- Cruttenden, A. (2014). Gimson’s Pronunciation of English (8th ed.). Arnold.

- Dyrenko, N., & Fuchs, R. 2018. The diphthongs of formal Nigerian English: A preliminary acoustic analysis. Proceedings of Interspeech 2018, Hyderabad (19th Annual Conference of the International Speech Communication Association), 2563–2567.

- Gimson, A. (1969). A note on the variability of the phonemic components of English words. Brno Studies in English, 8(1), 75–79 Accessed 02 04 2016 http://hdl.handle.net/11222.digilib/118041.

- Gut, U. (2004). Nigerian English Phonology. In B. Kortmann, E. Schneider, K. Burridge, R. Mesthrie, & C. Upton (Eds.), A Handbook on Varieties of English (pp. 813–829). Mouton de Gruyter.

- Gut, U. (2012). Towards a codification of Nigerian English – The ICE Nigeria project. Journal of the Nigeria English Studies Association (JNESA), 15(1), 1–13.

- Henderson, A. (2010). A corpus-based, pilot study of lexical stress variation in American English. Research in Language, 8, 99–113.

- Igboanusi, H. (2002). A Dictionary of Nigerian English Usage. Enicrownfit Publishers.

- Jamakovic, N., & Fuchs, R. 2019. The monophthongs of formal Nigerian English: An acoustic analysis. Proceedings of Interspeech 2019, Graz, 1711–1715.

- Jibril, M. (1986). Sociolinguistic variation in Nigerian English. English World-Wide, 7(1), 147–174.

- Jowitt, D. (1991). Nigerian English Usage: An Introduction. Longman.

- Jowitt, D. (2019). Nigerian English. Mouton de Gruyter.

- Kperogi, F. (2015). Glocal English: the changing face and Forms of Nigerian English in a Global World. Peter Lang Publishing.

- Mompean, J. 2010. A corpus-based study of phonological free variation in English”. In A. Henderson (ed.), English Pronunciation: Issues and Practices. Proceedings of the First International Conference. Chambery: France, 13–36.

- Obasi, J. (2019). English in Nigeria: Britishisms, Americanisms or Nigerianisms. Journal of the English Scholars’ Association of Nigeria (JESAN), 21(2), 139–157.

- Ogbulogo, C. (2005). Another look at Nigerian English. In Covenant University Public Lecture. Corporate and Public Affairs Division, Covenant University.

- Oladipupo, R. (2014). Aspects of connected speech processes in Nigerian English. Sage Open, 4(4), 1–6.

- Oladipupo, R., & Akinola, A. (2019). Linguistic and extra-linguistic correlates of English Palato-alveolar fricatives in educated Nigerian English. Journal of the English Scholars’ Association of Nigeria, 21(2), 103–123.

- Population Stat. 2019. Nigeria Population. Population Stat. https://populationstat.com/nigeria/

- Sankoff, D. (1982). Sociolinguistic method and linguistic theory. In J. Cohen, J. Los, H. Pfeiffer, & K.-P. Podewski (Eds.), Logic, Methodology, Philosophy of Science (pp. 677–689).

- Shitara, Y. (1993). A survey of American pronunciation preferences. Speech Hearing and Language, 7, 201–232.

- Simo Bobda, A. (1994). Aspects of Cameroon English Phonology. Peter Lang.

- Simo Bobda, A. (2007). Some segmental rules in Nigerian English phonology”. English World-Wide, 28(4), 279–310.

- Soneye, T. 2008. CH digraph in English: Patterns and propositions for ESL Pedagogy. Papers in English and Linguistics, 9: 9–20.

- Taiwo, R. (2009). The functions of English in Nigeria from the earliest times to the present day. English Today, 25(2), 3–10.

- Teilanyo, D. (2001). Britishisms, Americanisms and Nigerianisms: Prospects for a standard Nigerian English in the new millennium. Journal of Nigerian English and Literature, 2, 1–27.

- Udofot, I. (2003). Stress and rhythm in the Nigerian accent of English: A preliminary investigation. English World-Wide, 24(2), 201–220.

- Umar, H. 2015. American versus British English: Implications on L2 users of British English in Nigeria. A paper presented at the 31st Annual Conference of the Nigeria English Studies Association, Federal University of Lokoja, Lokoja.

- Wells, J. 1995. Age grading in English pronunciation preferences. In K. Elenius & P. Branderus (eds.), Proceedings of the XIIIth International Congress of Phonetic Sciences. Stockholm: KTH and Stockholm University, 3, 696–699

- Wells, J. (1999). British English pronunciation preferences: A changing scene. Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 29(1), 33–50.

- Wells, J. 2003. Pronunciation research by written questionnaire. Proceedings of the 15th International Conference of Phonetic Sciences. Barcelona, 215–218.

- Wells, J. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Pearson-Longman.