Abstract

The purpose of this study was to examine campaign narratives in four short documentary series entitled “Plastic Island.” Segara Kertih, Karmaphala, Bedawang Nala, and Tri Hita Karana are the titles of these four documentary programs. The short video series was created to raise community awareness of single-use plastic risks and modify social behavior via the use of Balinese culture and local wisdom. The research used a narrative analysis approach with Walter Fisher’s narrative paradigm and Boaventura De Saosa Santos’s Epistemologies of the South. The stories from Plastic Island demonstrate how local wisdom may be transformed into alternative knowledge to achieve global social liberation. The study results reveal that the four short documentary series have narrative probability, coherence, and narrative fidelity in the context of native Balinese wisdom values. Religious symbols and cultural ideas are reflected in the environmental communication campaign, which is based on the initiative Plastic Island. Returning to local wisdom is a natural conservation strategy based on shared knowledge, community values, and ancestral history.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Bali has become an overseas tourism destination with its natural beauty and rich culture. However, it is tarnished by the Balinese environmental condition with many plastic wastes. The Plastic Island Community was triggered by this condition and initiated a campaign titled Bali is not a Plastic Island by carrying local wisdom values of Balinese people in various media, including a documentary series. The documentary series titled Segara Kertih, Karmaphala, Bedawang Nala, and Tri Hita Karana becomes persuasive environmental communication, inviting Balinese people to view the environment as a cultural heritage that should be preserved. Using the narrative analysis method and narrative paradigm theory of Walter Fisher, the researchers scrutinized documentary series narratives, from the plot, narrative probability, coherence, and narrative fidelity from religious symbols and cultural philosophy that emerged in the documentary series. A narrative is crucial in persuasive communication, and thus, the campaign can run effectively.

1. Background

The issue of plastic waste in Indonesia raises many environmental movements. One such project is the Plastic Island, a project developed by Kopernik and Akar Rumput in collaboration with environmental activists from Bali, Gede Robi. Plastic Island is a collaborative campaign in dealing with the issue of single-use plastics in Bali. Plastic Island uses popular culture as a campaign on social media, short documentary shows and public service advertisements to raise community awareness of the dangers of using single-use plastic, changing social behavior and promoting sustainable change.

Plastics Island uses compelling environmental communication as part of an unique campaign approach to identify answers in a larger context. One of the Plastic Island campaign slogans is “Bali is not a Plastic Island,” which is explored in four documentary series. The four short documentary series were shown at alternative theaters and distributed to the public, who were encouraged to observe or participate in watch-along activities. The four short video series are titled (1) Segara Kertih Episode, (2) Karmaphala Episode, (3) Bedawang Nala Episode, and (4) Tri Hita Karana Episode. The tales in the four short documentary series were told using a local wisdom method, i.e., cultural identity and values, in order to preserve a life that is friendly to the Bali community’s environment. People in Bali follow their traditional customs and beliefs, which are Hindu in this situation.

In order to analyze the four short documentary series of Plastic Island, the researchers used Walter Fisher’s story paradigm in a narrative analysis method. The good story description effectively assures and shapes the perception of people who hear it. The perception leads individuals to determine their actions and attitudes and make decisions to support or reject the proposed ideas (Fisher, Citation1987).

In addition, in this study, the researcher used Boaventura De Sousa Santos’s Epistemologies of the South to critically assess a solution that does not follow scientific research but rather a community belief. Alternative knowledge is converted to information, which is then analyzed and converted into scientific knowledge. It is a type of cognitive extraction in which social movements may have an influence when they generate not just scientific proof but also a real solution that has the potential to transform society attitude with alternative information, which is Balinese beliefs and culture.

2. Literature review

2.1. Narrative paradigm in a cultural frame

The narrative introduced by Walter Fisher refers to the theory of symbolic behaviors, words, or ideas that have a range of meaning for people who live, construct, or interpret them. In line to Fisher (Citation1984), the narrative views are relevant to the real world and are fictional in life stories and imaginary stories. The narrative paradigm can then be seen as a dialectic complex of two traditional strands of rhetorical history: persuasive argumentative themes and aesthetic literary themes. The narrative paradigm emphasizes that human communication should be considered historical and circumstantial, because different stories create good reasons, satisfying the demands of narrative possibility and fidelity, and as inevitable moral inducements. The application of narrative rationality can help to better understand the story and its potential value.

From the perspective of narrative rationality, it must contain a story that the public can trust. Where, when building a history, elements of experience, background and culture, the probability and narrative fidelity can be met. The reason why the narrative is easily accepted and familiar is because it has the same values that live in society. Analyzing the Plastic Island campaign strategy with the slogan “Bali is not a Plastic Island”, generates a powerful story from the perspective of the culture, local wisdom, and beliefs of the Balinese. The narratives are given under the pretext of preserving cultural heritage, upholding customary law and practicing religious teachings. They’re intended to create a coherent story. Because the “good reason” that appears in the narrative is often born of the values that are also born in history, culture, and society, and the narrative becomes logical and acceptable. Whilst the typical manifestation of religious, social, cultural and political life, while glorified by those committed to traditional reason, is because they are not limited to “logic” but rather recognize and respond to the values that have been nurtured as a reaffirmation of the human spirit and as a basis for an extraordinary existence.

2.2. The campaign narrative of the Bali documentary series is not a plastic Island

Narrative is an important part of persuasive communication. Littlejohn and Foss (Citation2009) stated that a narration can convey meaning through a series of events and characters. Referring to the campaign account of the documentary series “Bali is not a Plastic Island”, both projects have similar sites, such as the beginning, the middle and the end, the link between one event and another, and a conclusion that gives the impression of a narration. In the series “Bali is not a Plastic Island”, the story is told by a speaker named I Gede Robi at the same beginning of each series that describes the problems caused by plastic waste. After the events have been described, there are solutions and settlement in which one problem is related to another problem. The impression, which is an event that is also a solution to the problem of plastic waste, certainly returns to Bali’s values and local wisdom.

Stories often evoke strong emotions in those who are exposed to them. It’s crucial since viewers often pass judgment on stories that include them. The stronger the story construction, the more emotionally drawn people are to the story. According to Littlejohn and Foss (Citation2009), story is critical to making sense of the world.

2.3. Environmental communication in campaign

Environmental communication often has a focus on protecting the environment, with communication that takes into account the relationship between humans and nature. Littlejohn and Foss (Citation2009:346) consider that this theory emerges from the concerns of scientists who study how people communicate about nature, especially about environmental crises. Many of the knowledge of environmental communication not only helps to understand the relationship between humans and nature, but also helps to social and environmental changes.

The same may be said of this research, in which Plastic Island used environmental communication as part of a single-use plastic reduction campaign approach. It is a movement aimed at providing knowledge on adaptive environmental management, sustainable lifestyles, and environmental communication based on local wisdom values and symbols in order to resolve environmental crises, allowing Balinese to behave intelligently in the face of environmental difficulties.

2.4. The strength of local wisdom values and epistemologies of the south

The Epistemology of the South is the idea of the Professor of Sociology, Boaventura de Sousa Santos. Santos’ idea is rooted in the anxiety of colonial domination, causing deliberate destruction of other cultures. Santos defines epistemicide as the elimination of knowledge (other than indigenous peoples’ genocide); the knowledge and cultural devastation of these communities, from ancestral memories and relationships to how they interact to other people and nature.

Santos (Citation2014) went on to identify “Epistemologies of the South” as a critical epistemology shift necessary to re-create global social liberation. It gave birth to a variety of liberation movements that are not solely based on a Western understanding of the world. Although the majority of the world’s population resides in the southern hemisphere, south is not a geographical notion. The phrase “South” alludes to a metaphor for humanity suffering on a worldwide scale as a result of capitalism and colonialism, as well as opposition to solving or minimizing such suffering. As a result, it is an anti-capitalist, anti-colonialist, anti-patriarchist, and anti-imperialist movement in the South.

The Santos’ notion of “Epistemologies of the South” gives a new foundation for studying community transitions. It allows for other solutions to be considered rather than sticking to scientific information, because the answer to the same problem in each nation differs, as seen in Bali’s plastic waste and single-use plastic concerns. Due to unrestricted single-use plastic use, every country has the same dilemma of protecting the environment from plastic trash. Is the solution, however, applicable to all regions? Even today, Bali possesses intellectual property in culture and indigenous wisdom from predecessors that has assisted in the management of environment. As an alternate answer, the Epistemologies of the South method allows for a reconsideration of cultural authority. The Epistemologies of the South approach was used as a critical analysis in this work to recognize the presence of numerous knowledge systems as a modern knowledge alternative or connected to new knowledge configuration.

2.5. Balinese local wisdom

Bali is widely welcomed by its rich culture and customs. Most Balinese believe in Hinduism. The main Bali religious activities are rituals that delivering offerings on a daily or on a given day. It is called yadnya, the sincere and sacred sacrifice. The purpose of the offering is to seek security and peace in the universe.

In addition to religious events, Bali has a customized village, where there are awig-awig or rules. The Balinese tend to follow the traditional village of awig-awig, taking into account the sanctions of their own rules if they violate the rules. The sanctions vary from warning, isolation, and ultimately expulsion from the village. Therefore, Bali has a relatively high collectivism value.

The community maintains the cultural and customary peace that has existed for centuries. According to Kacen & Lee, Citation2002), someone with strong collectivism is generally driven by the group’s norms and duties, and prioritizes the group’s goals. Another feature of this culture, is that members must always preserve peace, that their sense of reliance is great, and that conflict between members is avoided as much as possible.

People’s perspectives on life are formed by a combination of religion and customs. Balinese belief in Tri Hita Karana, or harmony between humans and the creator, among humans, and with the universe. To promote communal peace, this idea defends community conduct. It is used in numerous religious rites in Bali to purify segara, or the sea, as well as to make sacrifices to living things like plants and animals. And they believe in prosperity symbols like Dewi Sri’s rice and Dewi Saraswati’s wisdom sign. The Balinese believe in karma, which is the belief that what happens in this life affects future lives. Whatever we do, good or bad, we will receive the same results, though not always at the same time. It is typical of the Balinese to always keep harmony in their lives.

3. Research method

The researchers used narrative analysis methods to observe how this local wisdom story is built up in the Plastic Island campaign. Narrative studies have a variety of forms with different analytical practices and the roots of different social and humanities disciplines (Daiute & Lightfoot, Citation2004). As a method, this narrative study began with proven experiences in stories seen and told by individuals. The researches provide the means to analyze and understand those experiences and stories.

Following Foss (Citation1996), narrative “serves as an argument for a certain way of seeing and interpreting the world” (p. 400). It enables scientists to investigate and describe “a cohesive universe in which social activity takes place” (Berdayes & Berdayes, Citation1998, p. 109). Czarniawska (Citation2004) defines narrative analysis as specific qualitative designs that the stories are understood as speeches and texts associated with events and actions in a time series. This study was carried out with a focus on individually learning, the collection of data by the story, the reporting of individual experiences, and the classification of the meaning of the experience in a time series.

One may be more exact about how culture develops story using this methodology. The author’s narrative analysis was a structural analysis (Riessman, Citation2008), which shifts the focus from telling the tale to conveying the story. The attention is equally on form, how a storyteller creates an engaging story utilizing a variety of storytelling strategies, despite the subject material remaining.

This structural method looks at how a clause fits within the wider story. Labov (Citation1981) later adjusted the technique to first analyze persons who are responsible for the violence—short tales that are topic-centered and temporally organized—but he kept the basic elements of narrative structure: troublesome action (a series of events or plots, usually with a crisis and turning point); evaluation (when the narrator takes a step back from the action to comment on meaning and voice emotion—the “soul” of a narrative); resolution (flow result); and coda (ending story and bringing the action back to the present). Not all stories have all of the components, and they might appear in different order.

Narrative research is a tedious practice, given the methodology and characteristics of descriptive research. Researchers must gather comprehensive information about the subject of the study and understand the true context. It requires the precise identification of material sources for the collection of specific stories to gather individual experience. In this study, researchers have an advantage because they are familiar with the local wisdom of Bali.

4. Result and discussion

Kopernik and Akar Rumput came up with the idea for Plastic Island. It was launched at Potato Head Bali in 2018. Plastic Island is a joint effort to address the issue of single-use plastic in Bali and its environs. Plastic Island launched four short documentary series in mid-2019, which were shown in alternative cinemas and prompted public discussion. Balinese beliefs are equivalent to plastic waste issue solutions in the titles of this short documentary series.

The major aims of the Plastic Island film screening and program distribution are to (1) change community behavior to reject, reduce, reuse, and recycle, and (2) support the Balinese government’s single-use plastic ban policy implementation. Over 50 villages in Bali, Lombok, Java, Sumatera, Sulawesi, Timor, and Papua participated in the Plastic Island pilot episode in diverse activities.

4.1. “Segara Kertih” episode

This series begins with a music concert at Kendang by Navicula, who sings a song called Ibu. Robi, Navicula’s vocalist, conveys the message that, despite Mother Nature’s generosity, we harm her by disposing of plastic waste. Robi Navicula, the main character, meets several interviewees, including Inneke Hantaro, in Semarang to study microplastic. Gede Robi then flies to Bali after discovering several facts indicating that milkfish and clams contain hazardous microplastic. Robi tests microbeads, or microplastic, for cosmetics use in Bali.

Robi, dressed as a Celuluk, scares people in a public gathering field. Robi collects public-use plastics and replaces them with reusable plastics. A picture at the end of the series depicts a community ritual of praying on a beach. It depicts how Balinese Hindus protect the beach through various rituals passed down from their forefathers. Segara Kertih translates to “sea purification”. Thrown-away plastic waste will end up in the ocean and pollute the environment. It contradicts Balinese belief, which holds that the sea is a holy place where many living things live and should be preserved.

Robi frequently mentions the dirty sea from the beginning to the end of the video. The sea provides a living source for humanity, particularly the Balinese. The sea is a holy place for Hindus because it is used for cleaning and purification in almost every religious process. The constructed narrative is based on Hindu belief, according to which the sea is Dewa Baruna’s palace. As a form of gratitude and offering to the lord of the sea, Segara Kertih, a special holy ceremony is performed. Aside from the ceremony, other rituals such as Melasti (Nyepi sequence) and nganyud are performed (sequence of Ngaben).

The above is a scene in the “Segara Kertih” episode, where the Hindus perform ngayud ritual, floating the ashes after the ngaben procession (cremation) or as symbolic of the spirit in the arrangement of leaves and flowers. Ngayud ritual symbolizes humans being free from the universe life and going towards eternal purity.

This campaign invites the audience to preserve the sea not only in rituals but also in everyday behaviors in the Segara Kertih episode. The most basic example is to avoid dumping waste, particularly plastic waste, into the ocean. Unconsciously, waste is the primary cause of sea pollution. It’s ironic that we’re contaminating it with plastic waste. Using the Segara Kertih teaching, our forefathers devised strategies to preserve the sea and its contents as living sources for the rest of the world.

Narrative fidelity refers to a commitment to story narratives in which the stories created are identical to those created and lived in Bali. In the Segara Kertih episode, when the belief in purifying the sea transforms community behavior to stop dumping rubbish into the sea, the story designation as a solution contributes to narrative fidelity.

Furthermore, this episode features a terrifying creature known as Celuluk. Bali has people who live in two worlds: sekala (actual world) and niskala (dream world). Celuluk is one of the species that lives in Niskala. In Hindu philosophy, Celuluk is portrayed as a horrible monster interrupting human lives, and it is associated with the “Bali is not a Plastic Island” campaign. In this episode, Celuluk is compared to a vengeful spirit who haunts mankind when their environment is contaminated with plastic waste. These narratives then warn the community about the dangers of plastic trash in the environment. As a result, the Celuluk symbol’s narrative accuracy is believed in real life. The following concludes symbols produced and the narrative analysis in a documentary series of the Segara Kertih episode, which are summarized in .

Table 1. Narrative rationality analysis in segara kertih episode

According to Littlejohn and Foss (Citation2009), environmental communication studies will investigate ideas such as core culture and rhetoric critics environmental narratives that observe human-nature or culture-nature couples as the ideological regulating factor that discovers a dominant environmental narrative reproduction or destruction and interpretation of ethnocentrism, anthropocentrism, or exocentricism can inform everyone’s communication, from the general public to environmental advocates. In this episode, Plastic Island recalls local wisdom insights and invites the public to reapply the values of Hinduism.

4.2. “Karmaphala” episode

Robi encounters residents who are cleaning up a rice field littered with plastic garbage. They complain that garbage pollute the rice fields and clog their waterways. Robi then encourages them to sort rubbish on a household size, separating organic and inorganic waste. Robi asks rural communities to sort garbage as part of the waste sorting process.

Olivier Pouillon, the founder of Kono and Gringgo Trash Tech, is also interviewed by Robi. He requests that Olivier educate others how to sort trash. Sorted wastes, predominantly plastic bottles, are delivered to I Nyoman Astawa’s trash bank. When Navicula finishes performing, Robi pulls in the crowds, and the band’s riders are not using plastic.

The plot continues with Plastic Island searching for a person who uses no plastic while shopping in one of Denpasar’s department stores. After some time has passed, a person is chosen to bring their own shopping bag. The mayor of Denpasar, Ida Bagus Rai Mantra, testifies in support of Perwali No 36/2018, which prohibits the use of single-use plastics.

In the philosophy of the Balinese Hindu culture, Karmaphala is the fundamental belief of Hindus, which acknowledges the consequences of deeds. Robi explores how the waste tossed carelessly by the community will damage life and how this bad effect will return to where it came from in this second episode. This is how the karmaphala narrative’s significance gets raised. What we seed is what we will harvest, according to the constructed narrative.

Subak is a sacred location in Bali with an irrigation system. It’s because Subak delivers significant benefits to rice fields that are well-watered. Throwing trash into the river, which then accumulates in the fields, will, of course, contaminate the sacred area, causing farmers to suffer. Subak is an irrigation system in Bali that irrigates rice fields so that all of them can be watered. The water source is real, as is the sacred spot stated in the film. shows how the activities in this Subak depicted in the film. Balinese people perform rituals to safeguard the sacredness of water sources on specific days. This episode’s narrative faithfulness can be described as precise.

The story continues with Robi sorting organic and inorganic waste from a household to a village scale. There are also stories about karmaphala, and how proper waste management will reward the manager. Even though garbage handling is quite simple, being negligent is detrimental.

Robi interviews Ida Bagus Rai Mantra, the mayor of Denpasar, about Bali’s garbage management dilemma. Single-use plastic bags have been prohibited in shops and food booths in Denpasar from 2019. This regulation takes into account a number of factors, one of which is the growing problem of plastic trash in Denpasar, Bali. This positive initiative is expected to yield positive results, as the rubbish problem would undoubtedly limit visitor interest in Bali.

The Karmaphala story continues until the very conclusion of this video. Good steps will provide good outcomes. In actuality, how we manage waste and limit single-use plastics to protect the environment will lead to positive outcomes, i.e., protecting the earth. The symbols of belief that appear in this episode demonstrate narrative fidelity. The following summarizes the narrative analysis of rationality in the Karmaphala episode, which can be seen in the .

Table 2. Narrative rationality analysis in karmaphala episode

Walter Fisher (Citation1984) makes a similar point, describing narrative perspective as a metaphor for the flow of human experience. All advice discourse is built on the foundation of stories. Reckoning and retelling are stories we tell ourselves and others to create a meaningful universe of existence, regardless of their shape. Each model of counting and retelling is a technique of linking truths about the human condition, but the narrator’s character, conflict, resolve, and style will vary.

4.3. “Bedawang Nala” episode

The setting begins with a lot of plastic usage, and ordering food through online motorbike taxis is a waste of time. Robi encourages the audience to reduce plastic waste in food booths on this basis. Robi also makes comparisons if some cafes or restaurants do not use plastic and do not properly segregate plastic garbage.

Following that, Trash Hero’s Robi and Putu Evie give bamboo straws to street sellers who still use plastic straws. Robi offers the food stall owner a solution as a replacement for plastic packaging towards the end of the story. At the very least, this strategy is highly effective in minimizing the usage of single-use plastic.

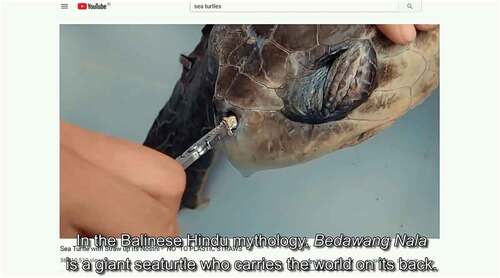

Bedawang or Bedawang Nala, in Balinese mythology, is a huge turtle who carries the entire world on its back. He is a departure from Antaboga in the world’s creation legend. The human world is supported by him and two dragons. There will be earthquakes and volcanic explosions on the earth if it moves.

It is the story that appears at the start of this video. Robi wonders how the natural equilibrium would be restored if God’s other animals, such as turtles, were threatened by human activity. The link can be seen in Balinese Hindu belief, where turtles are regarded as cosmic balancers. The turtles in this series are based on a viral video in which a turtle swallowed a plastic straw.

Can be seen in , in one scene, a rescuer is seen pulling out a plastic straw stuck in a turtle’s nose for a long time. It is discovered that the straw has solidified and obstructed the turtle’s respiration.

Robi and his trash hero buddies offer bamboo straws to street vendors to avoid the dangers of using plastic straws, which disrupt the natural equilibrium. Traders have been notified that these plastic straws may risk the life of a decades-old dog. The turtle is considered sacred in Hinduism and is represented as a universe balancer.

In Hindu philosophy, the turtle or tortoise is a place where Lord Vishnu, the God who is portrayed as the universe’s preserver, lives. Bhedwangnala is derived from the Kawi word “bheda,” which meaning other, group, or distinction. In the meantime, “wang” denotes chance and “nala” means fire. Bhedawang Nala is thus a group that ensures the presence of fire. This interpretation of fire can refer to both literal fire (aka magma) and a symbol of life force energy. Bhedawang Nala means “the power of the earth created by God to be kept and developed” because of its low location. This turtle, known as Bedawang Nala, was eventually used to construct Padmasana, a Hindu shrine where Hindus worship God.

This episode demonstrates narrative faithfulness by providing a plausible scenario. The narrative of Bedhawang Nala, like Hindu mythology, is about how the presence of plastic garbage in the water threatens the lives of turtles. The way to keeping turtles in balance while also keeping the universe in balance is to not litter. The following summarizes a narrative analysis of symbols in the Bedawang Nala episode, as shown in the .

Table 3. Narrative rationality analysis in bedawang nala episode

The concept of man as a storyteller denotes the overall shape of the entire collection of symbols. According to Fisher (Citation1984), symbols are generated and disseminated as tales that regulate the human experience and inspire others to live in them to establish ways of living together in communities where stories that shape one’s life are sanctioned. Bedhawang Nala appears as a narrative emblem of balance related with the universe in this episode documentary series.

Narratives distort rather than reflect the past. How storytellers choose to convey events and make them interesting to others is influenced by their imagination and strategic importance (Riessman, Citation2008). Narratives are useful in research because storytellers interpret the past rather than simply repeating it. The “truth” of narrative stories is in the shifting relationships they create between the past, present, and future, rather than in their faithful representation of the previous reality.

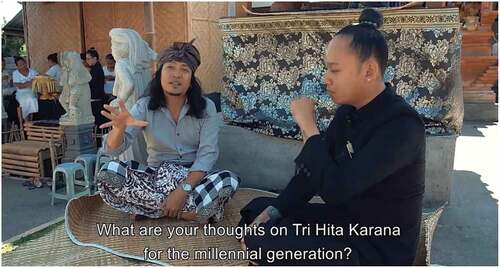

4.4. “Tri Hita Karana” episode

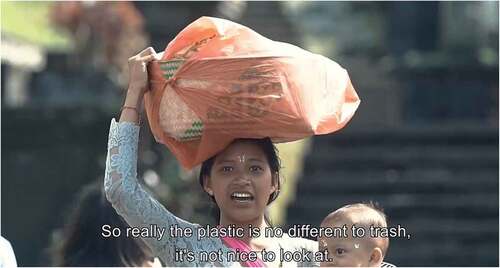

In the last episode of “Bali is not a Plastic Island,” Robi and thousands of locals work together at a Hindu temple in Bali. Lempuyang Luhur temple is one of the most popular photographic locations in Bali. Much trash can be found littering the shrine. After the temple cleaning operations were a success, Robi and his PHDI friends continued their plan to clean Bali’s most important temple, Besakih Temple, with the help of many people.

On , the main actor, Robi, speaks with a sulinggih, or Balinese ritual leader. Considering this waste from a religious perspective portrays plastic in a negative light. Using the bag sukla (clean) concept, the Balinese practice of purchasing prayer facilities with plastic is translated into a shopping bag.

In the last scene, Robi and his band, Navicula, perform a music concert to bring this objective to life. Rangda appears to scare people who continue to use single-use plastic packaging towards the end of the concert.

In Hinduism and Balinese principles, Tri Hita Karana refers to the three relationships that must be balanced. Human-God, human-human, and human-nature are the three relationships mentioned. The created narrative in the final episode of the “Bali is not a Plastic Island” campaign short film series is how humans should protect natural harmony. It is related to the universe’s balance through preserving the three relationships.

The illustration depicts Robi participating in cooperative operations to clean a Hindu temple, which is filthy and full of plastic rubbish. It contrasts with Tri Hita Karana’s harmony notion. After that, Robi invites Balinese youths to clean the temple in order to restore its purity.

shows people clean the Lempuyang Temple. In this scene, many Balinese students clean the holy area of Lempuyang Temple, one of the biggest temples in Bali. It is carried out to restore the temple’s purity from people’s waste during religious activities. As a result, the concept of plastic being leteh, or dirty in Balinese, is central to this video tale. A Balinese Hindu religious leader, according to Robi, regards the plastic concept as filthy. By creating a narrative that plastic is filthy, Hindus are discouraged from bringing plastic to temples. Bringing plastics to temples is associated with making the temple unclean. Bringing plastic prayer facilities is not the answer. The use of plastic to cover yadnya or precious offerings can pollute the temple’s purity.

Balinese Hindus frequently cover their prayer areas in plastic (as seen in the ), because it is considered sukla, or clean. This behavior, however, is harmful to the environment. As a result, Plastic Island establishes the narrative that plastics pollute the environment and have limited applications. It is harmful to the environment and lends plastics the label of leteh (filthy).

The concepts of “sukla” and “leteh” in terms of narrative faithfulness differ from local belief, where “sukla” is reportedly associated with clean, modern, and pure facilities. According to how the Balinese normally wrap the ceremonial facilities in new and clean plastic, their cleanliness is kept. However, the narrative integrity modified significantly, with “leteh,” the polar opposite of “sukla,” described as not bringing plastic into places of worship. Bringing plastic to places of worship or temples will result in the temple being filthy as a result of the plastic garbage. People are recommended to avoid using plastic and instead look for alternatives such as banana leaves, reusable bags, or other non-plastic media.

Because reusable bags are not guaranteed to be clean and pure or “voluntary,” there is a controversy in the community. However, in this episode, a Sulinggih or religious person who justifies the narration in this short video is used to bolster the plot. The narrator wishes for the constructed narrative to be well appreciated in society.

Plastic Island highlights how decreasing single-use plastic will indirectly balance the universe, beginning with the protection of animals and plants, as well as fellow humans, because there will be no accumulation of plastic garbage that will have an impact on the economy and tourism. Finally, it explores our relationship with God’s nature and how we care for it. The following summarizes narrative analysis through symbols in the Tri Hita Karana episode, and can be seen in the .

Table 4. Narrative rationality analysis in Tri Hita Karana episode

It’s worth noting that narrative is a universal style of communication. It can, however, be specific and effective for a certain target population. First, story represents the world’s experience by acting on numerous senses, reason and emotion, intelligence and imagination, and prevalent facts and values all at the same time. Second, narrative probability and fidelity are not taught because they are acquired through ability and experience through education and become proficient in understanding and applying these principles, as is the case with the Plastic Island campaign narrative, which reconstructs local wisdom and Balinese beliefs as advice to do good things for the environment. Even though people are unaware that this value is inserted as a persuasive act in environmental communication, this story is simply accepted since it has narrative probability and narrative faithfulness based on common experiences and values.

4.5. Translating culture in documentary series narratives of plastic Island

Balinese people have lived in harmony with nature long before modern knowledge. They rely on their lives and want to live in harmony with nature and the environment. This ancestral history is reflected in Balinese customary customs, traditions, religion, art, and culture. Balinese people, for example, use “canang” as a prayer medium in religious events. The “canang” ideology is more than a prayer sign; it is also an ancient tradition in which the materials employed include agricultural goods such as leaves, flowers, fruits, and a variety of other natural elements. From this perspective, Balinese religious activities must be sustainable. When Balinese people want religious activities made from natural materials, they must ensure that nature and the environment may thrive so that the products can be used for religious events in the future. The ancestors imprinted in this long-lasting chain of life the idea that what one contributes to the creator must not harm nature, which is the source of all life.

“Bali is not a Plastic Island” is a documentary series that recounts alternative knowledge that existed for decades but was forgotten in the sake of modernity. According to Santos (Citation2014), we are not running out of alternatives. What’s missing is an alternate perspective on those other answers. Information is translated into alternative knowledge, which is subsequently evaluated and transformed into scientific knowledge.

We learned that knowledge ecology is based on the pragmatic premise that it is critical to evaluate real interventions in the public and natural world supplied by various forms of knowledge in the Plastic Island documentary series narratives. It focuses on the link between knowledge and the hierarchy that is built between them, as there would be no tangible practices without one. Rather than a single, universal, and abstract hierarchy of knowledge, the knowledge ecosystem favours a hierarchy based on context, taking into account the particular outcomes intended or attained by various knowledge activities (Santos, Citation2014).

Santos (Citation2014) also pointed out that we must distinguish between two scenarios. The first is a decision between competing interventions in the same social dominant where different forms of information collide. In this scenario, the precautionary principle should lead to decisions based on democratic assessments of benefits and drawbacks rather than abstract knowledge hierarchies. It re-emerges local wisdom as an alternative knowing in a gradual change that western understanding cannot forecast. Diverse presence modes, ideas, or feelings; methods of comprehending time and the connection between humans and non-humans; ways of dealing with the past and future; and collectively organizing life are all examples of diversity.

Each episode of the documentary series Bali is not a Plastic Island presents a different perspective on how Balinese people’s indigenous wisdom evolves into alternative knowledge to solve challenges. In the episode “Segara Kertih,” for example, documentary actors scientifically describe the state of fish tainted by microplastic that endangers the body. People dispose of plastic into water sources, notably the ocean, where it is consumed by fish and remains in its body. When humans consume fish, the microplastic in the fish might cause cancer if it settles in the human body. When this story is told to Balinese people, especially the lower middle class, it is not certain that they will comprehend the microplastic explanation scientifically, and it will not stop them from discarding plastic debris into the ocean. The tale from local knowledge is then combined with a religious symbol, such as the ocean as a sacred location or “Segara Kertih.”. People recollect traditional beliefs that it is forbidden to contaminate sacred sites. Balinese people do not believe in superstition since they think the so-called “prohibition” is broken. They will be held accountable for their actions. The penalty is in the form of an indirect “reprimand,” which they will get now or in the future. The Balinese people are the target of a narrative that combines scientific information with alternative knowledge derived from popular beliefs.

The performers introduce a Subak irrigation method from Balinese people’s traditional history in the “Karmaphala” episode. Several Asian nations’ thousand-year-old irrigation systems were replaced in the 1960s with modern irrigation techniques championed by green revolution campaigners. The ancient irrigation system of Bali, Indonesia, was based on ancestral, agricultural, and hydrological knowledge and was overseen by Dewi-Danu, the Hindu goddess of water (Callicott, Citation2001: 89–90). The transition had significant effects for rice agriculture when it happened. It was so awful that the scientific system had to be abandoned in favor of the old system. The real tragedy, however, is the alleged mismatch between two knowledge systems designed to perform the same intervention—paddy field irrigation—as a result of an inappropriate situation examination caused by abstract judgment (based on universal modern knowledge validity) about the relative values of various types of knowledge. A numerical model—one of the more difficult domains of science—proved many years later that the water chain handled by priestess Dewi-Danu is significantly more successful than the scientific irrigation system tracked (Callicott, Citation2001: 94).

As a result, the Balinese think that preserving ancestral legacy is essential for communal existence. Plastic Island’s fact finding in the Karmaphala episode demonstrates how plastic garbage pollutes the irrigation system, or Subak. Plastic Island uses the “Karmaphala” story as a punishment for not properly maintaining the irrigation system. Balinese people believe that good and evil acts both have karma, or the outcome of good and bad deeds. When our forefathers leave us a well-designed irrigation system, we must be cautious to avoid negative consequences in the future.

Non-scientific knowledge diffused among subordinates enters and exits scientific practices, is respected, and the social practices they maintain, crisis and disasters may be averted. Crediting non-scientific knowledge does not imply disparaging scientific information in the knowledge ecosystem. It entails the application of counter-hegemony through scientific knowledge. On the one hand, it investigates plural epistemology’s alternative scientific procedures (Santos, Citation2014).

Rural and indigenous forms of knowledge assist biodiversity preservation, which, ironically, are under threat owing to rising science-based initiatives (Santos et al., Citation2007). Once again, culture emerges as a credible story to re-explain alternative knowledge in the realm of universe protection.

Instead of discourses, Plastic Island provides tales that lead to a solution. Plastic Island depicts a turtle symbol as balance in the episode “Bedhawang Nala.” It alludes to the topic at hand, namely, a turtle discovered injured after eating a plastic straw. Balinese people could live without harming nature before modern technology came and the populace had never heard of plastic. When plastic helps humans, it becomes a hazard to the environment. Plastic Island provides remedies from lost indigenous history, like as wrapping in coconut or banana leaves and utilizing woven bamboo or rattan bags instead of plastic bags. Due to current understanding, this local riches has become a forgotten answer.

Finally, Plastic Island introduces a philosophy that Balinese people should embrace in their daily lives: “Tri Hita Karana,” which translates to “life in harmony with nature and the creator.” The broad “Tri Hita Karana” notion is condensed into a knowledge of how to alter the concept of prayer action. The story goes that using plastic for holy purposes is “leteh,” or filthy. The idea of “leteh” is frequently associated with unholy materials or those that are not “sukla.” As a result, the story created is an appeal to refrain from bringing plastic to prayer locations, which might make the space “leteh,” or unclean. Plastic Island’s story may be used to translate alternative knowledge into information, which can subsequently be analyzed and transformed into scientific knowledge. It is a type of cognitive extraction that has certain characteristics with the material extraction of natural resources, which is now the most common method of capital accumulation in many regions of the world. This documentary series examines how cultural and local knowledge understandings are translated into tales that inspire people to protect the environment by honoring their ancestors. “Tri Hita Karana” is a Balinese way of living that intercepts contemporary information that threatens the balance of existence in harmony with nature.

5. Conclusion

Based on the explanation, it can be determined that the four short documentary series known Plastic Island share a narrative structure that Plastic Island has created. The Balinese people’s native knowledge values and philosophy are reflected in the similarities. Plastic Island believes that the problem of plastic use and waste may be overcome by reflecting on the notion of local knowledge that exists among Balinese people.

This research looks at four short documentary series from Plastic Island that exhibit coherence and narrative fidelity with societal standards. They are more likely to carry the notion of communal wisdom and beliefs so that the information presented may be believed. This does not, however, imply that the four videos have flawless narrative correctness. In the Tri Hita Karana episode, the public is asked to modify the reasoning that has grown in them and to return to ancestral practices, where people could live and make offerings or yadnya without using plastic in the past. This series lacks a narrative style that takes place in traditional Bali communities. Village regulations, or awig-awig, are a necessity that the people in the village follow since it is a matter of belief. If ideas about the use of plastic cannot be changed, it should be done in traditional villages.

Because of its influence on emerging ideas as a recognizable entity in public discourse, the narrative paradigm notion must be understood. Individuals, communities, or the general public, narratives have a crucial notion to be employed as a persuasive means in a campaign by evaluating message receivers’ coherence and narrative integrity.

The narratives supplied by presenting local wisdom values, culture, and beliefs of the community are a solution for alternative knowledge not seen in current knowledge, according to the notion of southern epistemologies. The same problem cannot be treated in every country with the same approach. Each has evolved various values and views in these areas. Santos (Citation2014) expressed it on the premises of southern epistemologies. For starters, a Chinese vision of the world is significantly larger than a Western understanding. This indicates that the world can change in ways that Western philosophy, even critical thinking, does not foresee. Second, the world’s diversity is infinite. Diverse presence modes, ideas, or feelings; different ways of perceiving time and the connection between humans and non-humans; different methods of coping with the past and future; and different ways of organizing existence collectively are all examples of diversity. Because theories and conceptions formed in the global North and employed across academia do not identify such alternatives, the breadth of alternative living, hospitality, and connection with this world is largely in vain. In this example, Plastic Island has created a campaign called Bali is not a Plastic Island that tells a story based on local knowledge. People trust local values more than scientific explanations when it comes to environmental preservation. Balinese ancestors have passed down information that is not documented verbally but has been shown to reconcile life with nature.

The researcher did not investigate the same tales in other media, which is a weakness of this study. The researcher analyzed both general and community-specific tales. As a result, the message was successful owing to the closeness element, which stemmed from both experience, knowledge, and societal ideals. Future research will be able to examine more complicated material. The study may be used to develop a campaign plan that takes into account the narrative approach of local knowledge in a community to ensure that the message delivered is successful.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Virienia Puspita

Ni Wayan Primayanti is a media practitioner, she works as a producer at a well-known television station in Indonesia.

Virienia Puspita is a Senior Lecturer at Bina Nusantara University (BINUS), Jakarta, Indonesia. Being a lecturer since February 2000, Virienia is a Subject Content Coordinator at the Communications Department, Binus Postgraduate Program. She is interested in researching cultural communication, rhetorical criticism, and culture-based marketing communications.

References

- Berdayes, L.C., & Berdayes, V. (1998). The information highway in contemporary magazine narrative. Journal of Communication, 48(2), 1097124. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1998.tb02750.x

- Callicott, J. B. (2001). Multicultural environmental ethics. Daedalus, 130(4), 77–17 https://www.jstor.org/stable/20027719.

- Czarniawska, B. (2004). Narratives in social science research. SAGE.

- Daiute, C., & Lightfoot, C. (Eds.). (2004). Narrative analysis: Studying the development of individuals in society. SAGE.

- europeansouth.postcolonialitalia.it. 2016. Epistemologies of the South and the Future. Accessed on March, 1st 2022 via http://www.boaventuradesousasantos.pt/media/Epistemologies%20of%20the%20south%20and%20the%20future_Poscolonialitalia_2016.pd

- Fisher, W. R. (1984). Narration as a human communication paradigm: The case of public moral argument. Communication Monographs.

- Fisher, W. R. (1987). Human communication as narration: Toward a philosophy of reason, value and action. University of South Carolina Press.

- Foss, S. K. (1996). Rhetorical criticism: Exploration and practise. Waveland Press.

- Kacen, J. J., & Lee, J. A. (2002). The influence of culture on consumer impulsive buying behavior. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 12(2), 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327663JCP1202_08

- Labov, W. (1981). Speech actions and reactions in personal narrative. In D. Tannen (Ed.), Analyzing Discourse: Text and Talk (pp. 219–247), Washington DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Littlejohn, S. W., & Foss, K. A. (2009). Encyclopedia of communication theory. SAGE.

- Riessman, C. K. (2008). Narrative Analysis. In Lisa M. Given (Eds.), Qualitative research methods (Vol. 1&2, pp. 539–540). Sage Publications, Inc.

- Santos, B. D. S., Paula Meneses, M., & Arriscado Nunes, J. (2007). Opening up the canon of knowledge and recognition of difference. In B. de Sousa Santos (Ed.), Another knowledge is possible: Beyond northern epistemologie (pp. xvix–lxii). Verso.

- Santos, B. D. S. (2014). Epistemologies of the south: Justice against epistemicide. Routledge Taylor & Fracis Group.