Abstract

Elizabeth Garside Senter (1841–1885) is a unique figure in the history of women in the American West. An early pioneer in the fight for women’s acceptance in the field of medicine, her California practice as a physician and surgeon was informed by a social conscience that grew out of her childhood experiences with the miseries of the mills in Manchester, England, with the horrors of slavery that she witnessed both in New Orleans and later in Upper Alton, Illinois, and by the aspirations and hardships of waves of immigrants embarking on challenging journeys, leaving their old lands to settle new ones. Just as importantly, she was the lover and muse of Charles Edwin Markham (1852–1940), called the “Dean of American Poetry”. Poet, writer, and influential voice in American literature, Markham’s later success was in large part due to the early support and encouragement he received from her. Their passionate letters chronicle both their affair and Elizabeth’s interest in mental illness, a study then in its infancy. Senter’s career was brief, cut short by worsening tuberculosis, but her achievements helped to establish pathways for other aspirational women and influenced two very different disciplines.

Elizabeth Garside Senter (1841–1885) is a unique figure in the history of women in the American West. She was the lover and muse of Charles Edwin Markham (1852–1940), poet, writer, and influential voice in American literature. Just as importantly, Senter was an early pioneer in the fight for women’s acceptance in the field of medicine as practicing physicians and surgeons. From the age of 13, she worked to establish herself as a qualified physician, writing near the end of her life that “[I have] battled against such fearful odds” (ES-EM6). She was interested in mental illness and its causes, a discipline then in its infancy, and asked, “Why do not the people grow better—instead of as it seems worse?” Concluding, “O, how merciful must one learn to be!” (Letter CitationES-EM53,). Senter’s career was brief, cut short by worsening tuberculosis, but her achievements helped to establish pathways for other aspirational women and influenced two very different disciplines.

1. Materials and methodology

Given Senter’s diverse activities, the methodologies utilized for this paper necessarily frame different aspects of one life and encompass a wide range of material. Her early years can be traced in parish and census records, immigration depositions and secondary material analyzing social and cultural conditions in the times and places she lived. Her relationship with Markham is preserved in a cache of letters, not fully explored in the literature and now in the Markham collection at the Horrmann Library of Wagner College, New York. It is in these letters that we hear Senter’s voice and the raw eloquence of commentary on her own life. Markham outlived Senter by 55 years but kept her letters for the rest of his life. She kept his letters as well, arranging for their return to him at her death. Of the trajectory of her medical career, its stages are signposted by notices of her graduation from the University of the Pacific in San Jose, from the Medical Department of the University of California, San Francisco, by outside medical references, comments in her own letters about her practice, and the tributes offered to her by her fellow physicians. Another significant pool of primary material absent from the literature is the surprisingly detailed coverage of Senter’s career and personal life in local newspapers. That coverage stresses her singularity by highlighting the public interest in her both as a person and as a physician, unusual for a professional woman at this period. Elizabeth’s dual agency as doctor and muse engages with material that has been underexplored or absent from discussions of women in medicine in the American West.

Elizabeth Garside Senter

(from L. Filler, The Unknown Edwin Markham)

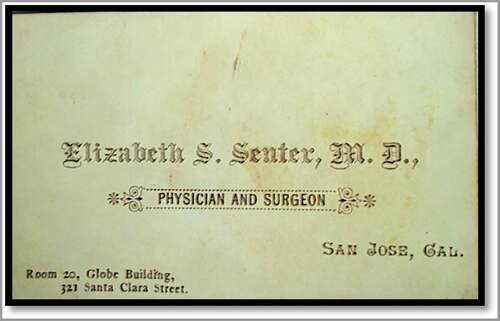

Senter’s business card (ES-EM28)

2. Women’s place in early California medicine

Women practicing in elite professions such as medicine or the law were rare in mid-19th-century California. There was a widely held belief that: “Women are intellectually more desultory and volatile than men, they are more occupied with particular instances than with general principles; they judge rather by intuitive perceptions than by deliberate reasoning or past experience” (Lecky, Citation1890, 359). Such a vested belief within a male-dominated society assumed that employment in the sciences was beyond the reach of a woman’s capabilities. Remarkably, the conviction, that “men and women differ in their emotional responses”, is still being debated today, with a recent study analyzing “the implications of gender differences in emotion regulation” and another paper asking, “Are Women More Emotional Than Men?” (McRae et al., Citation2008, 143–62; Schmitt, Citation2015, online). This perception that women are held hostage to their emotions while men deal in reason and logic, a cultural conviction fundamental to the 19th-century, threw up significant barriers for those women trying to qualify as physicians.

In California during the first half of the 19th century, there were, of course, unrecorded numbers of women engaged in medical work who, without official or legal recognition, acted as midwives, nurses or homeopathic practitioners, and certainly were the principle caregivers in the home, but licensed woman doctors were almost non-existent (Walsh, Citation1977, passim; Skinner, Citation2014, 7–40). By the mid-1850ʹs, records in-state show a handful of women practicing as physicians who had qualified in more progressive schools out of state. As early as 1854, Dr. Martha N. Thurston, who had graduated that same year from the New England Medical College in Boston, and one Hannah Andrews from Massachusetts were practicing as physicians in San Francisco (Langley’s San Francisco City Directory, Citation1861, 329; Harris, Citation1932, 209). In the ensuing years, a scattering of women qualified and opened practices catering almost exclusively to other women and their children. In 1863, seven female doctors were listed in the San Francisco City Directory, all of them carefully segregated by their sex and stamped with the socially acceptable imprimatur of marriage (Langley’s San Francisco Business Directory, Citation1863, 429: Scully, Citation1988, 761–3). It was not until 1876, a seminal year in the history of Western women in medicine, that the American Medical Association (AMA) admitted its first female member (Harris, Citation1932, 207–16).

Things began to change during the latter half of the 19th century, and in California the locus of this change centered on the city of San Francisco. A way forward for women was announced in 1874 when the former Toland Medical College, founded in 1868 and incorporated in 1873 into the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), opened its doors to women applicants. Shortly after, the Medical College of the Pacific (later Stanford University School of Medicine), founded in 1858 as the first medical school on the West Coast, also admitted women with Dr. Alice Higgins graduating in 1877 and Dr. Anabel M. Stuart the following year (Slawson, Citation2012, 12; Scully, Citation1988, 762). The Woman’s Journal had prophesied a few years earlier that, “the day is not far distant when women will compel medical men to know that as physicians they are their equal” (Walsh, Citation1977, 89–90). But that day had not yet come.

Although the general prejudice against women doctors or their admission to any official medical society did not diminish, in 1876, the duly elected membership of the California State Medical Society voted in 34 new members, among them (but aggressively challenged) five women doctors who were expected to confine themselves to the diseases of women and children. One of their male compatriots commented, “Taken as a whole, they will probably never amount to much” (Harris, Citation1932, 211–12). Yet in this same eventful year of 1876, Lucy Maria Field Wanzer became the first woman to receive a medical degree from UCSF, blazing a trail in California for her sisters in medicine, among them the outstanding physician Dr. Charlotte Blake Brown (1846–1904), who performed the first oophorectomy on the West Coast (Official, Citation1899, 88; Official, Citation1896, 32; Harris, Citation1932, 214–5; A. Brown, Citation1925, 579–82). Dr. Brown had to leave her home in Napa, California, and travel to the East for her medical education. She graduated from the Women’s Medical College in Philadelphia in 1874 and shortly thereafter moved back to California, where in 1875, together with Drs Martha Bucknell and Sara E. Brown, she founded what would become the San Francisco Hospital for Children.

In California, women wanting to enter the field of medicine and willing to challenge the prohibitions set up against them were a pioneering lot in a state rife with pioneers. Practitioners like Drs Wanzer and Brown stood out as role models for those who aspired to the profession. One of this aspiring number was a young English girl named Elizabeth Sarah Senter (nee Garside) (1841–1885). To date, Dr. Senter’s sole claim to fame has been as a footnote in several biographies of the poet Edwin Markham (1852–1940), describing their passionate affair in 1883–84. This limited focus of attention has had the effect of minimizing not only Elizabeth’s personal struggle to qualify and practice as a doctor but the success she achieved in her profession, despite a dysfunctional family, an unsupportive husband, coercive in-law’s, a demanding lover, and the societal opposition to a woman working in a “man’s field”. Although her independent medical practice spanned just two years, her engagement with medicine as a medical preceptee lasted several more. Her reputation as a doctor and the respect she achieved among her medical peers was demonstrated in life by multiple honorariums in the local newspaper, by her full membership in the Santa Clara Medical Society and the American Legion of Honor, and in death, by the crush of people at her funeral and the cortège led by six pallbearers, all male physicians practicing in San Jose. Her lover called her a “genius”, but she claimed only a “talent” that grew because she had worked so hard (Letters CitationES-EM7 & CitationES–EM35).

3. Origins

Elizabeth Sarah Garside was born on 26 April 1841 in the town of Ashton-under-Lyne, in the English county of Lancashire. She was the eldest child and only daughter of a farmer named Hugh Garside (born in Cheshire in 1811) and his wife Mary (born 1819). Elizabeth’s brother, George William, was born there seven years later in August 1848 (Ashton, Citation1841, 127). Elizabeth’s birthplace was a small market town on the banks of the River Tame which stood in an area heavily populated by cottage weavers (State Census for California, Citation1852, 80). Located only six miles east of Manchester, it lay just north of the Huddersfield Narrow Canal, opened in 1811 to connect Manchester’s textile output to the port of Liverpool. During the decade of the children’s birth, the landscape was rapidly changing character as it became increasingly industrialized. The growth of the greater Manchester area as the epicenter of an array of mills feeding the cotton textile industry put tremendous pressure on local farmers trying to maintain their agrarian way of life.

During Elizabeth’s early years, life in Ashton-under-Lyne became increasingly unpleasant and its weavers in the 1840ʹs “were receiving compensation … for poor sanitary conditions” (J. C. Brown, Citation1990, 614). By 1850, Manchester, itself, nicknamed “Cottonopolis”, was the third largest city in Britain with a population of a quarter of a million people. Men, women, and children labored in the mills, often in appalling conditions, and the sense of social injustice that Elizabeth felt as an adult may have begun with an awareness of this as a child. Years later, she expressed her anger at the “poverty, degradation and filth” she saw in parts of California. “One forgets how it is here and has to receive that impression anew at each visit”, she wrote after a trip to San Francisco, an impression that may have echoed her childhood memories of Manchester (Letter ES-EM53).

As a farmer, the pressure on Hugh Garside’s livelihood finally became unsustainable, and when, in January 1848, gold was discovered in the mill race at Sutter’s sawmill in Coloma, California, the Garsides joined so many other seekers after a better life and decided to emigrate. In February 1849, just a year after the discovery of California gold, Hugh packed up his wife and two young children and, together with his younger brother William, traveled 35 miles east to Liverpool where the family took ship on the perilous two-month sea voyage that would carry them to New Orleans. They arrived there on 12 April 1849, and for the children, the voyage was a great adventure. “I do so love to be near the Sea—and on it”, Elizabeth later wrote (CitationLetters ES-EM6). Their port of call, New Orleans, was two-thirds the size of Manchester, but like Manchester it was then the third largest city in the country. The chief port for the exportation of sugar produced on the surrounding plantations, the divide between rich and poor was stark, and it was here that Elizabeth would have seen for the first time one quarter of the population who were enslaved. Her possible awareness of mill conditions and subsequent exposure to slavery and its degradation of humanity would be reflected in Edwin Markham’s later description of “a character uniting a woman’s tenderness with a fierce hatred of wrong” (EM-ES43).

Besides the shock of slavery, the city was subject to frequent outbreaks of cholera and yellow fever, and the Garsides did not stay long. From New Orleans, the family traveled 700 miles up the Mississippi to Upper Alton, Illinois, a trading town on the river 18 miles north of St. Louis. At that time, the town was known for two things, its educational institution of Shurtleff College, established by Baptists in 1832, and its violent confrontations between abolitionists and raiding slave catchers as Upper Alton was one of the principal stops on the Underground Railroad. One memorable event in this on-going battle happened a decade earlier in October 1837, when abolitionist printer Reverend Elijah Lovejoy had held an Antislavery Congress in the town and a week later was shot dead by a pro-slavery mob (State Census for California, Citation1852, 80; Federal Census for Illinois, Citation1850, 394).

Although Hugh and William began farming in a seemingly peaceful neighborhood dominated by craftsmen—carpenters, potters, coopers and plasterers—it soon became apparent that Upper Alton with its pro- and anti-slavery tensions did not suit them. In the summer of 1851, the family sold up and traveling to St. Louis, joined a wagon train heading westward toward California. In yet another perilous journey, their route would take them through Comanche and Apache territory along the Santa Fe trail, and from Santa Fe, along the Old Spanish trail to Los Angeles, a journey of nearly six months and 1600 miles. According to Hugh, the party reached the small settlement of Los Angeles (population 1610) on Christmas Day, four months before Elizabeth’s eleventh birthday (California State Court Naturalization Records, Citation1852, 37). For the Garsides, Los Angeles was just another stopping place along the way, and shortly thereafter, they traveled north to Santa Clara County where the town of San Jose had just become the first capital of the new state of California.

The fight between Mexican landowners, who held their land from the now vanquished Mexican government, and incoming American settlers from the East led to the California Land Claims Commission of 1851 which resulted in many of the previous owners losing title to their property. Available farming land opened up, and the Garside family established a claim that by September 1852 saw them once again on their own farm just west of Santa Clara township (Great Register of Voters of California, Citation1868, 56; State Census for California, Citation1852, 80). The long journey from Lancashire would prove to be a good investment, and the Garside farm prospered. On the farm next-door, lived a family named Senter, the patriarch of which was both a farmer and a Massachusetts-born judge, Isaac Newton Senter (State Census for California, Citation1852, 284).

Although there had been a year-long break in Illinois, by September 1852 Elizabeth Sarah had been traveling more or less continuously for nearly four years. She was seven when she left her home in Lancashire and eleven when her family arrived in Santa Clara. The sights she had seen, the dangers and hardships she and her family had endured, and the differences between the place she had left and the place where her family had now settled must have been formative for a precocious and curious mind. Although the Gold Rush appears to have been the motivating factor behind the family’s journey from Lancashire to the American West, Hugh never engaged in mining. His elder son, George, however, became a mining surveyor, developing several successful mines in the Silver Bow Basin in Alaska. He spent much of his adult life in Juneau, a town he helped to lay out, dying there in April 1908 (Federal Census for Alaska, Citation1900, 23; Harvey, Citation1984, 37; District, Citation1890). In 1862, a decade after they had settled in Santa Clara County, the youngest Garside, Charles Ward, was born. Twenty-one years younger than Elizabeth, Charlie Garside also had a successful career as a mining engineer and surveyor in Alaska and moved to Juneau in 1885 shortly after his sister’s death. He died there on 19 March 1934 (CitationLetters ES-EM39; Report, 1899, 406; The Alaska Daily Empire, 20 March 1934).

All three of the Garside children were intelligent, but daughter Elizabeth was exceptional. Her travels as a child had made her restless, awakening in her the desire to see more of the world, a longing that as an adult she expressed in letters to her lover Charles Markham. “The spirit of unrest has taken possession [of me] again,” she wrote in November 1883 (CitationLetters ES-EM6). But first marriage and then illness prevented her from satisfying that spirit and she described her depression in another letter, lamenting that “my wings are clipped” (Letter CitationES-EM36). Introverted, solitary, a dedicated student fascinated by the evolving worlds of science, Elizabeth was only 13 when she applied to and was accepted into the Science Division of the University of the Pacific. Located in San Jose not far from the family farm, the university was California’s oldest, founded in 1851 by members of the Methodist Church. Her admission was extraordinary for her age and sex and an exception to the university’s admission protocols which stated that: “No one will be admitted into the Freshman Class until he has completed his fourteenth year” (Catalogue, 1857, 7). A catalogue for the university for 1856–7 shows Elizabeth as one of seven female students in their junior year (Catalogue, 1857, 11). That her parents must have supported her in this endeavor given her age and gender was also exceptional. Something, perhaps the ill health that troubled her much of her life, prevented her from graduating in 1858 at the end of what should have been her senior year. Yet she persisted and graduated in 1859 with a Bachelor of Science degree, one of only four students in that year, an achievement of no mean magnitude (Catalogue, 1873, 5; Catalogue, 1876, 6).

The thirst for knowledge that drove Elizabeth to fight her way into a university at 13 came to a crashing halt with her graduation. Whatever her goals were, given that California’s medical schools were not yet accepting women, is unclear, but her options were cut short by what she later described as the “great mistake” of her life (ES-EM44). At the university, one of her fellow students was the only son of her parents’ neighbors, the well-to-do Judge Isaac Newton Senter and his wife, Rebecca McIntire Senter. Charles Newton Senter (1833–1889), born in New York, was studying law. Articulate, ambitious and assertive, Senter was eight years Elizabeth’s senior. Not long after their graduation, Elizabeth made her great mistake and married him. The couple settled in San Jose where, following in his father’s footsteps, Senter opened a law practice. Although officially it lasted much longer, the marriage of Elizabeth Garside and Charles Senter was a disaster from the beginning. It cut short her ambitions, confined her talents, constricted her to the life of a dutiful housewife to a demanding husband, and oppressed her nearly to the point of suicide (ES-EM40). “[H]ow we do get into grooves which we cannot get out of”, she later mused, cursing her own timidity, and comparing her feelings toward her husband as being “almost afraid to move”, frightened “as a burnt child [who] dreads the fire” (CitationLetters ES-EM6 & 44). Brilliant she may have been but standing up to Charles was something Elizabeth found nearly impossible to do.

4. Charles Newton Senter

At the beginning of the Civil War in 1861, Charles Senter enlisted in the Union Army in the Fifth Infantry Regiment. Although he never left California, he was involved in various military activities over the next few years. In June 1864, he was commissioned 1st lieutenant and company quartermaster, and a month later he got a taste of military action when “a company of men, representing the Confederate government, was organized for the purpose of raising money for the Confederate cause by robbing stages and banks in California” (Sawyer, Citation1922, 133). On the night of 15 July, three such men were reported to be holed up in an empty building outside of San Jose, and Senter was one of the posse sent out to arrest them. Arriving at midnight, Sheriff John H. Adams, Senter and the rest surrounded the building.

But the men … had resolved to sell their lives dearly. Rushing out, they commenced firing at the officers. During the fusillade John Creal, one of the robbers, received three bullet wounds … another of the trio, had the handle of his pistol shot away … He was soon overpowered and handcuffed. John Clendennin, the third robber, after firing twice point-blank at Sheriff Adams, and receiving a settler in return, jumped over a fence and fled … Clendennin was taken to the county jail and died the next day …

This excitement in Senter’s public life as a full-time attorney and fighting Union army officer contrasted sharply with the constriction of his wife’s day-to-day existence. Having spent a childhood filled with travel, danger and adventure, followed by teen-aged years demonstrating academic excellence, Elizabeth’s marriage brought stasis, stasis brought boredom and boredom brought depression. She often felt, she wrote, “weary and unfitted” (ES-EM26). “Society, church and state continued … to regard [women as inferior], hedging her within the home where reproduction, rather without recreation, absorbed her life in gradually increasing boredom, intellectual arrest and sex[ual] passivity” (Harris, Citation1932, 208). Such attitudes towards women’s designated role in society as homemaker and baby breeder were openly approved by Charles Senter and his parents. “There is no escape from Duty,” Elizabeth noted. “I know what mine is and must do it” (Letter CitationES-EM35). But such duty brought no joy. Of her in-law’s, who seemed to feel their son had married beneath him, she wrote: “I have to be careful for they are my enemies” (CitationLetters ES-EM10, & 39). Reproduction, the accepted justification of a married woman’s life, eluded her. It was not until over a decade after her marriage, on 30 November 1874, that her only child, a daughter Irma, was born.

During the 1870ʹs, Charles Senter continued to grow his reputation in San Jose. He advanced from lawyer to judge, joined the Odd Fellows, and became actively involved in local politics, appearing now and then in the local newspapers. In July 1872, commenting on the upcoming presidential election that pitted newspaper publisher Horace Greeley and Governor Benjamin Brown of Missouri against the incumbent President Ulysses S. Grant, the Weekly Alta newspaper of San Francisco reported that:

A mass meeting to ratify the nomination of Greeley and Brown is being held tonight at the intersection of First and Santa Clara streets. Tar barrels are blazing, a band of music playing, and considerable interest is manifested in the proceedings, a large crowd being present. Dr. A. J. Spencer, an old line Republican, was called on to preside, and after a few remarks introduced Judge C. N. Senter, another old line Republican (Weekly Alta, Citation1872).

In August of the following year, Charles became a candidate for Justice of the Peace (Weekly Alta, Citation1872).

Elizabeth had grown up in a turbulent family. Her parents’ marriage was not a happy one, and about the time that Irma was born, Hugh and Mary Garside divorced. By 1880, they were living in separate boarding houses in San Jose half a mile from each other, Hugh at 323 San Fernando Street and Mary on St. James Street (Federal Census for California, Citation1880, 42, 48). Elizabeth, living at 1st and Julian, was only a short walk from both. Neither parent was employed and as both of her much younger brothers had by now moved to San Francisco, to Charles and Elizabeth would have fallen the responsibility of her parents’ well-being and financial support. Given that she had entered the university at age 13 and would return to her education two decades later, there was little likelihood that the intellectually formidable Elizabeth retired happily to a life of housekeeper, parental caretaker and helpmate. She chaffed under the restrictions of her life and yearned to move as her brothers had done to San Francisco. She later wrote to Charles Markham that “one never can escape the consequences of a mistake.” Elizabeth had come to loath her life in San Jose. “I ought not to be here of all places—there is so much to vex and annoy [me] that there would not be elsewhere” (CitationLetters ES-EM39, & 44). Two years after her daughter was born, in that seminal year of 1876, when the AMA admitted its first female member, the Medical Division of UCSD graduated its first female physician, and a year after Drs Brown, Bucknell and Brown had set up the San Francisco Hospital for Children, Elizabeth picked up the threads of her earlier ambitions and rebelling against the restrictions of her life, began to prepare herself to enter into the practice of medicine.

5. Medicine and Dr. Brown

Elizabeth’s mentor in this endeavor was Dr. Jacob Newton Brown (1837–1898), one of the most prestigious practitioners of medicine in the city of San Jose. He was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, and was a graduate of the Law Academy of Philadelphia, the Medical College of Cincinnati and the University of Miami in Oxford, Ohio. Married with two daughters, he was also the former chair of anatomy at the Toland Medical College which had since become the Medical Division of UCSD. As a college graduate he was unusual. In 1870, only 50% of practicing physicians held a college degree, so in this, both Brown and Senter were uncommon (Slawson, Citation2012, 14). In 1876, Elizabeth persuaded Dr. Brown to take her on as an apprentice, an arrangement known as a preceptorship, common for male medical students but unusual for female ones (Slawson, Citation2012, 14–15). A preceptor was by definition “an experienced practitioner who provides supervision during clinical practice and facilitates the application of theory to practice for students” (Faculty of Health, Dalhousie University, undated, online). Brown would have overseen the procedures that allowed Elizabeth to develop her skills in clinical diagnostics and surgery. But Dr. Brown was not her only supporter.

Among her champions outside the medical community was the editor of the San Jose Weekly Mercury, J. J. Owen. Owen was a progressive thinker with a sideline as a poet and he turned the editorial section of his newspaper to the fledgling doctor’s advantage (San Francisco Call, Citation1895). Elizabeth, he wrote sympathetically, “commenced the study of surgery and medicine in the office of Dr. J. N. Brown, of this city, under circumstances that would have discouraged all but the stoutest heart. Nothing daunted by the obstacles in her way she resolved to overcome them, and she has done so bravely and most successfully” (San Jose Weekly Mercury, Citation1882). Among those obstacles was her husband who, unlike Brown and Owen, was less than enthusiastic about her medical ambitions. But she persevered; a medical license was a ticket to economic independence and a way out of San Jose. In 1880, her preceptorship at an end, she fulfilled Dr. Brown’s expectations and her own sense of purpose by applying for admission to the Medical Division of the University of California, San Francisco, where she was accepted.

This was an enormously courageous step for a 39-year-old woman with a young child and a socially prominent husband jealous of his own reputation, and although no official announcement was made, Elizabeth had also decided to separate from Senter. Her divorced parents were no longer able to support her, but she had family encouragement for her move to San Francisco from her brother, Charlie, who was living on Market Street and her brother George, who was living on California Street. Elizabeth was particularly close to Charlie, who was young enough to be her own son, and wrote of him: “He is a very dear good boy and has kept himself so well that I feel a little proud of him” (CitationLetters ES-EM39). The new medical student took up residence at 14 Pfeiffer Street in the North Beach District, some five miles northwest of the university and just a few minutes walk from Fisherman’s Wharf. Exalting in her new-found freedom, Elizabeth fell in love with the city. “[H]ere are all the triumphs of our civilization—our churches—libraries—Universities—opportunities for training in all branches of fine art—lectures—the drama and music … all heightened by the beauty of the situation—the grandeur of the Sea” (Letter ES-EM53). She was fascinated as well by the work being done at the Children’s Hospital, founded a few years earlier by Dr. Charlotte Blake Brown, writing that “I like the medical work here … there is so much more of it—I was at the Women’s and Children’s Hospital all the forenoon” (Letter ES-EM53).

Yet simply getting into medical school was only the first of her challenges. In general, women were not welcomed with open arms by their fellow male students. The experiences of Dr. Elizabeth Blackwell, who attended Geneva Medical College in New York in the 1840ʹs and was the first woman in the United States to receive a medical degree, expressed it well. “[As] I walked backwards and forwards to college the ladies stopped to stare at me, as at a curious animal. I afterwards found that I had so shocked Geneva propriety that the theory was fully established either that I was a bad woman, whose designs would gradually become evident, or that, being insane, an outbreak of insanity would soon be apparent.” For aspiring physician, Harriot Hunt, who attempted several times to attend the medical school at Harvard, the response from the male students was similar, encapsulated in the statement: “that we object to having the company of any female forced upon us, who is disposed to unsex herself, and to sacrifice her modesty by appearing with men in the lecture room” (Slawson, Citation2012, 22–3; Unattributed, Citation2016). “The woman’s sphere was the home,” so common wisdom ran, “and to remove her from this was both indelicate and dangerous” (Slawson, Citation2012, 22; Blake, Citation1965, 99–123).

Although these may have been the attitudes that faced her in the classroom and from the lecture podium, Elizabeth’s position as Dr. Brown’s protégée would have offered her some support. As with her time at the University of the Pacific, Elizabeth flourished in an academic setting, and her career at UCSF was ambitious, reinforcing her growing reputation. Medical school was a two-year set of courses, but, thanks to Brown’s training, Elizabeth finished in just over a year. Matriculating in 1881, she completed her degree the following year, qualifying in an amazingly short time as a degree-certified doctor (Announcement, Citation1888, 16, 117). That she did this while dealing with the beginnings of the tuberculosis that would eventually kill her made her qualification a tribute to both her courage and her commitment.

Commented the San Jose Weekly Mercury (Citation1882):

The Medical Department of the University of California will hold its commencement exercises at B’nai B’rith Hall, 123 Eddy street, San Francisco, on Friday evening of the present week, when, among others, the degree of Doctor of Medicine will be conferred upon Mrs. Elizabeth S. Senter, of this city. We congratulate Mrs. Senter on her success. She is a lady of fine brain and resolute will … While pursuing her studies in San Francisco, it was at one time feared she would be compelled to succumb to ill health, but with a pluck we have rarely seen equaled, she nailed her colors to the mast and resolved to conquer or die trying. She deserves her well won laurels (San Jose Weekly Mercury, Citation1882).

Of the 15 newly minted doctors only two were women. Elizabeth’s only female classmate, Dr. Mary Winegar Moody, went on to practice in San Francisco and become a member of the California State Medical Society (Journal, Citation1909, 404).

Elizabeth longed to remain in San Francisco but compelled by the limitations of her fragile health, she reluctantly returned to San Jose and set up her practice in Room 20 of the Globe Building at 321 Santa Clara Street. In 1883, of the ten medical practitioners who advertised themselves as physicians and surgeons in a city of 12,567, Elizabeth was the only woman (San Jose Daily Mercury, 7 December 1883). Two other women, who did not advertise as such but who held medical licenses, were practicing at the same time, Drs Euthasia (or Euthanasia) S. Meade and Lavinia D. Lambert. Both claimed to be widows which, given the expectation society put on women doctors to be married, may or may not have been the case. No husbands are readily identifiable from the records, and many women in the West used the guise of widowhood as an acceptable social identity for a single woman, especially one practicing a profession. Meade came from New York and was four years older than Elizabeth. She was a graduate of the Women’s Medical College in Philadelphia and had been practicing in San Jose since 1870, although she did not advertise as a “physician and surgeon” (Official, 1893, 75). Lambert, who advertised as a “homeopathist”, had received her degree from the University of Michigan the year before Elizabeth, and had by 1890 moved her practice to San Francisco (Official, Citation1891, 188).

Despite her reluctance to return to San Jose, Elizabeth’s credentials and personal connections within the local medical community appear to have allowed her to build up a nominally successful practice. She continued to work with Jacob Brown, exploring diseases of the mind, and in her letters chronicled the case of a “wife murderer” the two had taken on at the request of the District Attorney. The prisoner was being defended on the grounds of insanity, and Elizabeth laid out his symptoms. He refused to eat, “goes on all fours—makes all sorts of queer noises—takes no notice of what is said to him—never speaks”. The doctors had decided to run “some experiments on him” but did not describe what those experiments might be (CitationLetters ES-EM9). Another case involved two prominent San Jose doctors who were being sued for malpractice and who Elizabeth claimed had bought their medical diplomas in Keokuk, Iowa, for $25. “What a comment on the intelligence of our community,” she wrote in disgust, “that the two public officers should be what they are” (CitationLetters ES-EM33).

Elizabeth’s own practice consisted almost entirely of women and children, partly from cultural constraints and partly from her husband’s jealousy. Although estranged from Senter, circumstances had compelled her to share the family home and gossip would only have made her life harder. “I made it a rule from the first,” she wrote, “to invite no gentlemen to my rooms—I have rigidly observed it … Of course living in so cloister-like a manner if any one comes as a visitor—it is immediately noticed and commented upon” (CitationLetters ES-EM20). Among her patients may have been the quarrelsome and cantankerous 68-year-old Betsey Winchell Markham Grimmer (1805–1891), mother of Charles Edwin Markham, Elizabeth soon-to-be lover (San Jose City Directory, Citation1874, 89).

6. Charlie Markham

Charles Edwin Markham (1868)

(from L. Filler, The Unknown Edwin Markham)

Eleven years younger than his future inamorata, Charles Markham had been born in Oregon City, Oregon, and repudiated by a father, Samuel Markham, who believed that Charlie was not his biological son. He was raised by his mother with whom he had a difficult and volatile relationship. “I never was a child,” he confessed to Elizabeth in an outpouring of thanks for her emotional support. “I remember no boyhood—I recollect no mother’s kiss. Do you wonder that words are now too poor to tell [you of] my gratitude?” (CitationLetters EM-ES57). Bullied for his childhood stutter, a handicap that made it difficult for him to make friends, his youth was further stunted by his mother’s obdurate opposition to his educational ambitions (Filler, Citation1966, passim; Unattributed, Citation2021, online; Nash, Citation1999, online). His application and acceptance to San Jose State Normal School in 1870, against her wishes, was the signal for his mother to move with him to San Jose, alternating between approving of him and making his life hell. If Elizabeth, estranged from her husband and working to establish a medical practice, was in need of love and support, Charlie Markham, too, was in need of comfort. Publishing intermittently and yearning to become a recognized poet, in 1883 he was working as Superintendent of Schools for El Dorado County and living unhappily with his wife of eight years, Annie Cox, in Placerville, 160-plus miles northeast of San Jose. As Markham’s mother lived in San Jose on South Eighth Street, just a mile from Elizabeth’s Julian Street home, his extended visits to her gave cover for his meetings with the woman who may well have been his mother’s doctor (ES-EM20).

Elizabeth had moved back into the Julian Street house in San Jose in the winter of 1882, a few months before she met Markham. Worn out and in the early stages of tuberculosis, she did not have the strength, she said, to open a practice in San Francisco as she had wished, and her remembered unhappiness at this decision poured out in a later letter to Markham (San Jose Evening News).

Before I knew you – I came back here to a place I disliked – worn out – broken in health – disheartened – not strong enough to go off to a new place – as I should have liked – and had hoped to have done – I was so crippled that I was only too glad to accept a small offer made me here by my old preceptor and friend … It enabled me to start with less of the hardships and anxieties which I would have had to contend with if alone … but I have suffered too much here to ever like the place or to feel content – I know that I am surrounded by enemies and spies and regulate my life accordingly (CitationLetters ES-EM20).

Dr. Brown was her preceptor and friend; the enemies and spies were Elizabeth’s estranged husband and his parents. She had rented a private mailbox, unknown to them, to exchange letters with Markham, as her mail, she told him, was being checked. “I will not risk even a line coming to me [here] … as I seldom get my own mail—and I cannot have anyone know of my correspondence” (CitationLetters ES-EM26). Separated from her own family—her brothers would both shortly leave for the Yukon—she was desperate for love and encouragement. Her affair with Markham began in the middle of May 1883, and from the first they became each other’s secret life (CitationLetters EM-ES51). To her family, Senter was referred to by her middle name, Sarah, but to Markham she was Elizabeth, her identity as a doctor. To his family, Markham was Charlie, but to Senter he was Edwin, his persona as a poet. The moment of their meeting was so important that when Elizabeth mentioned to him that she was cleaning out her wardrobe, Markham wrote, “Please do not ever destroy the dress you wore that first afternoon. Please do not: it will always have a special sacredness to me” (CitationLetters EM-ES47).

Unlike the other women in his life, Elizabeth encouraged Markham’s poetry, sending him notes in Latin written in the form of medical prescriptions, prescribing “spei” and “cordis”, hope and heart (CitationLetters ES-EM46). “What about the writing you told me of—Shall you finish this winter?” “Keep on quietly and composedly with your work,” she wrote to him, “give to it your best strength—do not fret and worry—please do not” (CitationLetters ES-EM44, Letter ES-EM40). Such reassurance was what the struggling poet badly needed to hear. “I am so grateful for all you have given me,” he wrote in September 1884. “Those tears of mine—the only ones of my manhood—they sprang from the great joy breaking within me—joy that I had found you at last” (CitationLetters EM-ES57). He sent her clippings of his published work, which she praised, and in another letter, she told him to write “bravely [as] you have so much of fine force and energy that you must put it to some good use” (CitationLetters ES-EM44). She “released torrents of eloquence from him” and inspired replies that were often touched with poetry (Filler, Citation1966, 50).

How serene and quiet these mountain solitudes, these deep forests full of little winds and twilights … I have been watching the [rising] of the moon. It mounts up glorious behind a mass of pines. It has just cleared a deep cloud that sweeps away like a black wall northward. The sky is filling with tiny clouds of silver white. The night is wildly beautiful (CitationLetters EM-ES43).

Elizabeth wrote back in the same poetic mode.

The spirit of unrest has taken possession again –

I have come here. My Sphinx still waits –

The face looking seaward toward the setting sun.

The expression of the highest tranquility and repose –

I am rested and refreshed. It grows late –

Grey mists are stealing in from the sea –

I am standing between the two ‘great Silences’ –

Stars over as silent – graves under as silent –

I must go back to the babbling crowd –

But I feel strong again. (Letter ES-EM36)

Both knew the struggle to achieve an education, to pursue a desired career path, and each was trapped in an unhappy marriage. They shared “the Fellowship of Sufferings”, as Markham phrased it. “Both have passed a youth repressed and sad”, and both were suffering physical ills and mental depression. “You will forgive my wild anguished outcries—all of them,” Charlie wrote, “when you remember the fateful path I was travelling, in lands that were lonelier than ruin” (CitationLetters EM-ES57). Elizabeth assured him, “I know [that] road. I have travelled it—barefoot and hungry” (CitationLetters EM-ES47). And Charlie responded:

[Your message] haunts me like a strain of unearthly music. It is a poem, weird as the voices of the night … Oh! My dear Love, I should not be able to endure the journey in the valley of Dreadful Night, did I not have eyes fixed on a horizon that is quickening with the faint first steps of day.

For Markham, Elizabeth was that quickening horizon of light; for Elizabeth, Markham provided the intellectual approval and stimulation she had failed to find in her marriage. He was interested in medicine and thought her a “genius”; she was learning Greek, and translating Chateaubriand’s French novella, Atala, into English. Both were fascinated by music and studying an extensive array of literature. Not only sex but a wide-ranging curiosity bound them. They wrote about everything from art to current legal cases. Both deplored the exploitation of the poor and shared a commitment to social justice. He described a visit to Folsom Prison and the “tender serenade” a “Spaniard” in a cell played on his guitar. She sent him bundles of newspapers; he sent her books to read that they could later discuss. He gifted her with a subscription to The Century Magazine which “is a pure fountain of riches” (Letters EM-ES48; CitationLetters EM-ES32). She envied him his independence, “[but] then you are a man” (CitationLetters ES-EM44). He knew her unhappiness in San Jose and wrote to her near their year’s anniversary: “Almost hourly I feel an impulse to hurry to you and to carry you away from that evil place, as from a city of plague” (CitationLetters EM-ES51). “I long for you,” he told her, “with a longing that cannot be uttered. At times it seems I shall not be able to endure. Please send a brief line as soon as you get this—I am getting hungry again” (Letter EM-ES44; CitationLetters EM-ES60).

Elizabeth’s involvement with Charlie Markham had put an official end to both their marriages, angering and embarrassing Elizabeth’s socially prominent husband. Her terror of gossip and fear of exposure to censure as well as her worsening health made Markham’s demands problematic for her, but she was unable to break off the affair. By June 1883, she was spending clandestine days with Markham in San Francisco. Out-of-town medical conferences offered convenient opportunities for a rendez-vous. That November there was another meeting, and in December she wrote asking him to meet her again in the city. When she traveled to Sacramento for another medical convention a few months later, Markham joined her (CitationLetters EM-ES16). In late 1883, Judge Charles Senter departed San Jose and moved to Tacoma, Washington, leaving Elizabeth without cover for her extramarital relationship (San Jose Evening News, Citation1890; Sacramento Daily Union, Citation1890). His future visits to their daughter distressed his estranged wife greatly. Before one such impending visit, Elizabeth told Markham, “I dread it—and if it is to last too long—[I] will try to get away. It will be an awkward and trying time—will probably go to S. F. soon” (CitationLetters ES-EM34).

With her own career to protect, Elizabeth was terrified of the consequences should their affair become public. When Charlie wrote to tell her that he had separated from his wife and was “forming plans for our future”, Elizabeth panicked at the thought that he might pressure her into filing for her own divorce. He reassured her that he was only “dreaming dreams” of what might be. Although Charles Senter had moved out-of-state, Elizabeth’s actions were being monitored by his parents who visited regularly. They were providing funding for her daughter which she resented but was in no financial condition to refuse. She was certain her in-law’s visited solely to spy on her. “Grandpa S has been so long here that I am all out of patience,” she wrote to Markham. “I feel that I am subjected to a coarse espionage—renewed since the grandfather’s return from the East … I have to be careful” (Letters ES-EM610; CitationLetters ES-EM39). With a young daughter who provided a ready excuse for her estranged husband’s parents to visit, with no real local family support and suffering from advancing stages of tuberculosis, Elizabeth’s resistance to the importunities of the passionate poet who had tumbled into her life was countered by her very real need for that passion. “Because I made a mistake once—I must bear the consequences—though I have escaped now in great degree—still I am burdened—and I must bear it,” she wrote to him. “Whilst you remained I forgot everything which I ought to have remembered … I have feared that I was too married and worn to be pleasing and satisfactory—and you must tell me—it would be cruel not to do so” (Letter ES-EM35; Letter ES-EM28). “[You are]”, he assured her, “dearer to me than life” (Letter EM-ES55).

As time went on, Elizabeth’s fear for her own health led her to greater recklessness. She wrote to him: “The rose tints were very faint last night—when I walked over the old ways—yet I was not lonely in an unhappy sense—for somehow I feel that—no matter how far apart bodily we are—you are still with me—and this soothes and comforts me” (CitationLetters ES-EM13). “I could die,” he told her, “But I could not die without feeling grateful to you, for it has been so much—so much to have known and loved you for even this brief time—a time that now seems brief as a summer night” (EM-ES45). On his birthday, 23 April, Markham described a pair of mating birds, declaring to Elizabeth that “his mate is no comparison to mine! She is not so full of pretty surprises—not so handsome as mine with her sweet slight body and wonderful still face” (CitationLetters EM-ES41).

Although Elizabeth tried to continue her practice, her passion for medicine and her passion for Markham were both being overborne by her worsening health, and when Charlie wrote of carrying her off to a south sea island, Elizabeth felt she needed to awaken the poet to the realities of her situation. “During the Holidays [1881–2]—midway between Christmas and the New Year I had a hemorrhage from the lungs—the first one—I was asleep when it came on (2 A.M.) and shall never forget the horror of the choking sensation in awakening” (CitationLetters ES-EM20). This was something she had been living with since she returned to San Jose, “the shattering and damaging effects that I received three years ago—from which—I am satisfied now—I shall never recover” (CitationLetters ES-EM1). She had spent that time wrestling with her own mortality, trying for resignation. “What a strange thing this living and earning our existence is anyway,” she had written to him the previous year. “How good it would be to be free like the birds of the air and the beasts of the field. Fetters and barriers do chafe and one can easily understand how when it is seen to be inseparable from them, life (sweet as it is in some ways) can be given up almost gladly” (CitationLetters ES-EM6).

On 2 March 1885, Elizabeth’s brother Charlie Garside wrote from San Francisco to Markham in Placerville that, “I have just returned from San Jose having received a message that my sister was dead … I went to see her the first of last week and she requested me to write this letter to you and also to send the inclosed [sic] package of letters etc to you … I am very sorry to inform you of the above facts about Sarah” (Letter CWG-EM59, Citation1885). Although her importance to him and his work is unarguable, demonstrated by the letters he kept for 55 years, by the time Elizabeth gave up her life on 27 February 1885 in San Jose, her sometime lover had already found another mistress (Filler, Citation1966, 53–9). A decade after Elizabeth’s death, in 1895, Charlie Markham changed his name officially to Edwin Markham, and in 1898 published his most famous poem, “The Man with Hoe”, inspired by the Jean-François Millet painting. Although his luster faded somewhat after his death, during his lifetime Markham was considered one of the most important poets that America had produced, and to some extent, he had Elizabeth’s early encouragement and support to thank. He was to outlive the brilliant but physically fragile physician by 55 years, dying on Staten Island, New York, on 7 March 1940. Unlike her poet, medicine was not as fickle. The path Elizabeth Senter had laid down in medicine was followed by a growing number of women. The business directory for San Jose in 1890 listed 14 women physicians, five of them unmarried (San Jose Evening News, Citation1890, 859–61). By 1900, 15 years after Elizabeth’s death, the number of women physicians in the country had grown from a few hundred in 1880 to over 7000. Between 1903–5, some 400 women had qualified for a medical license in California (Bleemer, Citation2021, email; Unattributed, Citation2016, online).

Tributes honoring Dr. Senter in the San Jose Evening News were fulsome. Her funeral was “largely attended” and included an honor guard from the American Legion of Honor. The entire membership of the local medical council, as well as that of the Santa Clara Medical Society, were noted as “attending in a body”. Her six pallbearers, all physicians, included her mentor Dr. Jacob N. Brown. Although she had spent her adult life longing to leave San Jose, the town had embraced her and now celebrated her contributions to its health. But her secret life, just as she had feared, had not been so secret, and, surprisingly, the town appeared to take that secret, too, as another point of pride. The final sentence in the announcement of Elizabeth’s funeral arrangements stated that: “At the time of Mrs. Senter’s death, she was separated or divorced from her husband [name not given] … and romantically involved with the poet Edwin Markham” (San Jose Evening News, Citation1855). Dr. Senter would not have been amused.

7. Conclusion

Elizabeth Garside Senter was both representative of 19th-century women pioneers in California medicine and unique. Intellectually brilliant, courageously committed to a field of study that women were only grudgingly allowed to occupy, she was barely in her teens when she began her fight to become a surgeon and physician. It took her over two decades and left her a scant two years in which to practice. Yet the efforts she made within the profession, marking the way for her sister doctors, and what she represented among the medical community are as important as her place as Charles Edwin Markham’s poetic muse. Due to her acute intelligence and acknowledged abilities, exceptions were made for her. The University of the Pacific ignored their own regulations and admitted her at the age of 13; Dr. Jacob Brown ignored the social strictures that said women were unfitted for the practice of medicine to take her on as a student, and the University of California, San Francisco, granted her a medical degree after only a year of study.

Elizabeth Senter’s career speaks to the determination of an entire population of women intent on qualifying and practicing as physicians, in spite of the barriers put before them. Elizabeth’s own commitment to becoming a doctor is evident in the work she put in, despite illness and family difficulties, toward achieving that goal. Her medical life and her social conscience were informed by the miseries of Manchester’s mills, by the horrors of slavery that she must have witnessed both in New Orleans and later in Upper Alton, “by a woman’s tenderness [united] with a fierce hatred of wrong”, and by the aspirations and hardships of waves of immigrants embarking on challenging journeys, leaving their old lands to settle new ones. All these experiences combined with a “fine mind” and a love of science to ignite one woman’s dedication to a life of healing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Susan E. James

Susan E. James is an independent writer and researcher who earned her Ph.D. at Cambridge University. She has written extensively in the fields of the humanities and social sciences, publishing over 40 peer-reviewed articles on various aspects of the humanities, as well as three books on sixteenth-century English history: Kateryn Parr: The Making of a Queen (Aldershot: Ashgate Press, 1999), The Feminine Dynamic in English Art, 1485-1603: Women as Consumers, Patrons and Painters (Farnham, UK & Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2009, nominated for the Berger Prize), Women’s Voices in Tudor Wills, 1485-1603: Authority, Influence and Material Culture (Farnham, UK & Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2015), and one on the American West, Children of the Motherlode, 1856-1926: The Townsend Family and the Growing of the West (Oklahoma City, OK: books2read, 2021). Courtesy of L. Filler in The Unknown Edwin Markham, 1966.

References

- Letter ES-EM35 (Tuesday, 4:30 am). Elizabeth Senter to Edwin Markham.Horrmann Library, Wagner College Archives, New York.

- The Alaska Daily Empire. (1934, March 20).

- Announcement of the twenty-fifth annual course of lectures of the medical department, university of California with catalogue of students and graduates. (1888). University of California.

- Ashton-under-Lyne Parish Records. (1841). vol. 20.

- Blake, J. B. (1965). Women in medicine in ante-bellum America. Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 36. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press https://www.uab.edu/medicine/diversity/initiatives/women/history

- Bleemer, Z. (2016). Personal email communication referencing ‘a century of health’ (2017). University of California, San Francisco. https://www.uab.edu/medicine/diversity/initiatives/women/history

- Brown, A. (1925). The history of the development of women in medicine in California. Journal of California and Western Medicine, 23, 5.

- Brown, J. C. (1990). The condition of England and the standard of living: Cotton textiles in the Northwest, 1806-1850. The Journal of Economic History, 50(3), 3. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050700037177

- California State Court Naturalization Records. (1852, December 13).

- Catalogue of the university of the pacific for the academical year 1856-7. (1857). University of the Pacific.

- District of Columbia Marriage Records, Film Number 002026026, for Garside’s marriage on 6 January 1890 to Bessie Dyer Hill.

- Letter ES-EM53. (Tuesday 9:30 pm). Elizabeth Senter to Edwin Markham. Horrmann Library, Wagner College Archives, New York.

- Faculty of Health. Dalhousie university, Halifax, Nova Scotia. https://www.dal.ca/faculty/health/practice-education/for-students/what-is-a-preceptor-.html

- Federal Census for Alaska. (1900). Juneau, Alaska.

- Federal Census for California. (1880). Santa Clara County, Santa Clara Township.

- Federal Census for Illinois. (1850). Madison County, Upper Alton.

- Filler, L. (1966). The unknown Edwin Markham: His mystery and its significance. Antioch Press.

- Great Register of Voters of California. (1868). Santa Clara Election District.

- Harris, H. (1932). California’s medical story. J. W. Stacey, Inc.

- Harvey, D. (1984). Telephone hill: Historic site and structures survey. Juneau, Alaska: Alaska Archives and Resource Records Management.

- Journal of the American medical association. (1909). vol. 52. Chicago: American Medical Association.

- Langley’s San Francisco Business Directory. (1863). San Francisco: Towne & Bacon.

- Langley’s San Francisco City Directory. (1861). San Francisco: Valentine & Co.

- Lecky, W. E. H. (1890). History of European morals (Vol. 2). Longmans, Green, & Co.

- Letter CWG-EM59. (1885, March 2). Charles Ward Garside to Charles Markham. Horrmann Library, Wagner College Archives, New York.

- Letter ES-EM36 (Laurel Hill, San Francisco, Monday, 6:30 pm, Aug. 20, 1883). Letter ES-EM36. Horrmann Library, Wagner College Archives, Laurel Hill, San Francisco, Monday.

- Letter ES-EM7 (Sunday, 3:30). Letter ES-EM7 (Sunday, 3. Horrmann Library, Wagner College Archives,

- Letters EM-ES16, 32, 41, 43, 45, 47, 48, 51, 57, 60. ( 14 June, 26 June 1884, 23 April, 10 July 1884, 20 October 1883, 15 December 1883, 6 January 1884, 6 May 1884, 11 September 1884, Undated). Edwin Markham to Elizabeth Senter. Wagner College Archives, New York: Horrmann Library.

- Letters ES-EM6, 9, 10, 12, 13, 20, 26, 33, 34, 39, 40, 44, 46. (7 November 1883, Saturday, Sunday 6:30 PM, Undated, Tuesday Evening, 7 March 1884, Monday, 4 PM, Undated, Sunday, 9 PM, 11 October 1883, 17 December, Undated, 11 April 1884). Elizabeth Senter to Edwin Markham. Wagner College Archives, New York: Horrmann Library.

- McRae, K., Ochsner, K., Mauss, I., Gabrielli, J., & Gross, J. (2008). gender differences in emotion regulation: An fMRI study of cognitive reappraisal. Group Process & Intergroup Relations, 11(2), 2. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430207088035

- Nash, W. (1999). ‘Edwin Markham’s life and career – A concise overview’. Modern American Poetry. http://www.english.illinois.edu/maps/poets/m_r/markham/life.htm

- Official Register of Physicians and Surgeons of the State of California. (1896). Sacramento, CA: Department of Consumer Affairs – Board of Medical Examiners Records, Vol. F3760:p. 96.

- Official Register of Physicians and Surgeons of the State of California. (1899). Sacramento, CA: Department of Consumer Affairs – Board of Medical Examiners Records, Vol. F3760:p. 99.

- Official registers of physicians and surgeons of the state of California. (1891). Department of Consumer Affairs – Board of Medical Examiners Records. F3760:91-F3760:99.

- Personal email communication from Zachery Bleemer, (18 October 2021), Personal email communication from Zachery Bleemer, 2017. Retrieved from: https://blogs.library.ucsf.edu/broughttolight/2017/06/05/introducing-a-century-of-health

- Report of the commissioner of the general land office. (1899). Government Printing Office.

- Sacramento Daily Union. (1890, January 1).

- San Francisco Call. (1895, January 16).

- San Jose City Directory. (1874). San Francisco: Excelsior Press.

- San Jose Evening News. ( 28 February 1885; 2 March 1885; 2 January).

- San Jose Weekly Mercury. (1882, November 9); (1883, December 7).

- Sawyer, E. (1922). History of Santa Clara County, California. Historic Record Co.

- Schmitt, D. P. (2015). ‘Are women more emotional than men?’ Psychology Today. Sussex Publishers, New York. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/sexual-personalities/201504/are-women-more-emotional-men

- Scully, A. L. (1988). Medical women of the west. Western Journal of Medicine, 149, 6.

- Skinner, C. (2014). Women physicians and professional ethos in nineteenth-century America. Southern Illinois University Press.

- Slawson, R. G. (2012). Medical training in the United States Prior to the civil war. Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary & Alternative Medicine, 17(1), 1. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156587211427404

- State Census for California. (1852). Santa Clara County.

- Unattributed. (2016) .‘History of women in medicine’. Heersink school of medicine. The University of Alabama at Birmingham.

- Unattributed. (2021). ‘Edwin Markham: 1852-1940’. https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/edwin-markham

- Walsh, M. R. (1977). ‘Doctors wanted: No women need apply’: Sexual barriers in the medical profession, 1835-1975. Yale University Press.

- Weekly Alta. (1872). San Francisco, California.