Abstract

The purpose of this study is to assess the impact of Egyptian journalists through the “Anti-Cyber and Information Technology Crimes Law No. 175 of 2018” and the “Personal Data Protection Law No. 151” as well as its implications for journalistic practice and press freedom in Egypt. More specifically, the focal point of the study was to explore how the government monitors the data through new legislation. Questionnaires were undertaken with 188 journalists representing semi-governmental and private newspapers, divided into three categories: (86) Al-Ahrām (34) Albawabhnews (53) Al-Dustour and (15) Al Fagr. The study used Digital Authoritarianism Theory as a theoretical framework. The study revealed that the government placed restrictions on journalists by using Law No. 175 of 2018 to oppress journalists and media houses. In addition, the law has negatively impacted media freedom and given the government to censor online information.

1. Introduction

Egypt, recognising that rapid developments in digital technology have increased the scale, scope, and speed at which personal data is collected, used, and destroyed, began the use of computerized databases to store information about individuals after the Arab Spring revolutions. Accordingly, the government began to pass legislation that enhances the rights of “data subjects.” and subjects to secret surveillance by the state, all of which have potentially chilling effects on individual privacy and personal freedoms (AlAshry, Citation2022).

The Anti-Cyber and Information Technology Crimes Law appeared in 2018 due to the proliferation of many independent press websites that appeal to freedom of opinion and expression, but soon the Egyptian Parliament formed a committee composed of experienced members to monitor information on the website of the Media Site Foundation with the Ministry of Communications, dividing the articles of the law into four chapters that include (45 Acts) focusing on general provisions, procedural rules, crimes, and penalties (AlAshry, Citation2018). After that, the Egyptian Parliament approved law No. 151, issued in 2020, which consists of 49 legal articles related to the law that defines the frameworks concerned with the data, users, controllers, and how the government monitors the enforcement of the Personal Data Protection Law (AlAshry, Citation2022).

The Egyptian government has also stressed the activation of many laws that protect national security data, but this law has horrific effects on media freedoms (Mohiuddin, Citation2019). The law focused on the attack on the integrity of information networks, systems, and technologies; crimes committed by press websites; as well as crimes related to attacks on private lives; illegal information content, crimes committed by the site administrator; and the criminal responsibility of service providers with their own penalties. This law faced all possible electronic crimes which attacked media websites, as well as installing and falsifying images, exploiting this technological feature, and employing it to threaten Egyptian society (Ibrahim, Citation2019).

Egypt has always maintained legislation to control data through several media laws in the constitution and the penal code that obstruct journalists. However, many penal laws focused on “spreading false news,” either on social media sites or newspapers, and Law No. 195 indicated that “criminal responsibility is imposed on the editor-in-chief when he publishes information without obtaining permission from the government.” In terms of penalties, the law allows for imprisonment of no less than 500 thousand pounds and no more than a million gallons, as well as the blocking of websites under investigation by the authorities (AlAshry, Citation2022).

On the other hand, the government implemented offices to monitor all the media websites for fear that information could be published and threaten state security. The spyware includes cell-site simulators known as “stingrays” and the technologies that extract data by physically connecting to seized phones—known as “universal forensic extraction devices,” such as those developed by Cellebrite. Another spyware covers. In addition, powered surveillance facilitates mass monitoring, such as Huawei’s “Safe Cities” platforms (Philp, Citation2021).

This study analysed journalists’ perspectives and investigated the effectiveness of Egyptian journalists in the light of anti-cyber and information technology crime laws. However, the law has many consequences that have affected journalists and media houses. The law contains many legal provisions which may condemn journalists to imprisonment. After reviewing the laws, this study aims to assess the impact of Egyptian law on journalistic work by addressing the following research questions:

RQ1: How do journalists perceive press freedom in Egypt?

RQ2: What is journalists’ knowledge of Egyptian media law?

RQ3: How does the law seek to attack the integrity of information networks, systems, and technologies?

2. Literature review

2.1. Egyptian laws restricting information

Most of the internet censorship in Egypt is done for political reasons, which has always had an array of legislation that has stifled freedom of expression. The Egyptian government brought into effect the Anti-Cyber and Information Technology Crimes Law in 2018 to actively target media outlets, social media groups, and bloggers who criticize or make fun of the current regime (AlAshry, Citation2020).

Furthermore, Article 7 of the Bill authorizes “the investigative authority to block websites when it considers that the content published on these sites constitutes a crime or threat to national security or jeopardizes the security of the country or its national economy.”

Generally, the Egyptian government justifies the censoring of content and website blacklisting as an anti-terrorist measure. Since the enactment, journalists have continued to endure harassment and threats as the media landscape has continued to shrink, following the closure of 554 privately owned newspapers and websites (Belgacem, Citation2019). This blacklisting included the site of al-Jazeera, a Qatari-owned television network, which was banned in Egypt because of its supposed editorial support for the Muslim Brotherhood.

The law, which was approved in May of 2018, allows journalists not to publish information after a request made by the government, which may be impractical for journalists. The Egyptian government also allows prosecution of individuals who visit websites the Egyptian government considers “a threat to national security” or “national economy”. The government restricts the creation of websites for digital activism and political organization and those that exist are blocked for reasons that are not clear; failure to adhere to that might result in arrest, long jail sentences, intimidation, harassment, and other measures (AlAshry, Citation2018).

The Egyptian Parliament established a new law, “Personal Data Protection Law,” to be under Regulation 2018/1725. The law comprises some provisions governing the confidentiality of personal data, which mandate individuals or journalists to “get permission from the judicial authority.” Also, the law imposes an array of sanctions against entities and individuals that commit crimes related to personal data under Article 26. In para. 2, any entity or individual that processes an individual’s personal data without obtaining the consent of the person who owns the data and causes harm to that person is punishable by a term of imprisonment of not less than 6 months and a fine of 200,000–2 million Egyptian pounds (EGP; AlAshry, Citation2022).

There are negative effects of that law on freedom of expression and information circulation, as well as on the freedom of digital media, which is sweeping powers to crack down on digital freedom of speech and permits them to block websites. Other provisions in the law allow for harsh prison hacking of the government system or publishing information on the movements of the military or police. In addition, Egypt’s parliament added to the law an act which treats any social media account or blog with more than 5,000 followers as a media outlet. which opened them up to prosecution for crimes such as publishing fake news or “incitement to break the law.”

Journalists were obstructed under the law by investigative authorities presenting a competent court within 24 hours and the court issued its decision within 72 hours. Under Article 7, the authorities issued a blocking decision, giving the right to investigation and enforcement authorities to inform the National Telecommunications Regulatory Authority to immediately block websites.

Similarly, Alyaqoubi (Citation2019) noted that Internet freedom has shrunk as a result of increased blocking and media law used to reinforce and control journalists and bloggers through Article 64 which is about encryption. This remains restricted by the Telecommunication Regulation Law which highlights that employee, or another customer of any encryption equipment require written consent from the National Telecommunications Regulatory Authority and security agencies, and Articles 72 and 180 affirm exclusive control over the establishment of encrypted platforms requiring, the government to monitor those platforms. Article 57 also explains that platforms can be confiscated, examined, or monitored by judicial order, for a limited period, and in cases specified by the law; on the other hand, Article 58 highlights that the government’s surveillance operations lack transparency (Al- Khayun, Citation2019).

AlAshry (Citation2022) noted that there are Articles in the law with opposing words or phrases, such as the law prohibits information related to the government’s data from spreading by any means without the permission of the concerned government and should be legally authorized, these phrases are subject to court rulings and all the information made available to journalists must be obtained from the government.

3. Theoretical framework

The idea of “digital authoritarianism” (Dragu & Lupu, Citation2021) examines the dual effects of digital media on human rights by authoritarian governments and an opposition group that is used preventatively. They found that using digital media more frequently results in abuse to stop opposition groups from organising and increase violence from authoritarians. Modeling preventive repression leads to a novel strategic structure of authoritarian politics and human rights in our community, the journalists’ actions are strategic complements from the point of view of the government (Bosch & Roberts, Citation2021).

These results have broad implications for journalists’ freedom fighters, those who are advocating for democratization, and who challenge the regimes with their coverage of controversial political issues. The digital authoritarianism system requires direct governmental control of mass media and media professionals are not allowed to be independent or to take any decisions by themself. Digital authoritarianism propagandises the government’s ideology and the media are the mouthpiece of the government (Fuchs, Citation2022).

In the Egyptian context, the government exercises absolute power to control the media, which is generally seen as being authoritarian. For instance, President Nasser came to power in 1956 and closed many newspapers and nationalised the press, which ended press freedom (Ashour, Citation2020; Hussein, Citation2018).

After that, during the Sadat ascendancy (ruled from 1970 to 1981), the state maintained a monopoly over television and private radio ownership and implemented strict laws on pluralisation in political and media domains. This meant that many journalists and politicians were jailed (Álvarez, Citation2014; Khamis, Citation2007; Siddiq, Citation2015). Then Mubarak’s ambivalent attitude towards the press saw the journalists working in an unhealthy environment; Mubarak established an emergency law that granted wide power to the security forces. Additionally, there were numerous articles in the law that penalised the press, starting from a law imposed on the press and the law related to state documents that were not supposed to be revealed publicly (Siddiq, Citation2016).

Recently, regarding Egypt under President El-Sisi, Abdul-Jalil (Citation2019) states that the media sphere shrank not just in terms of press freedom, but also in terms of freedom of expression as government entities consolidated their control of media outlets, with little space for freedom. (AlAshry, Citation2022) affirms that the state controls the media through security agencies in direct or indirect control over most of the media houses.

4. Materials and methods

This study aims to investigate journalists’ perceptions of the law and to assess the effects of the law on journalistic work with respect to freedom of information in relation to access to information sources and the extent to which government control affects using the new law, especially for controlled newspapers, such as semi-governmental and independent newspapers.

The sample: quantitative approaches with 188 journalists from semi-governmental and private newspapers, divided into: (86) Al-Ahrām, (34) Albawabhnews, (53) Al-Dustour, and (15) Al Fagr, the data collected from March to May of 2020.

In the sample, the ages of the journalists were recorded and 32.5 % of the journalists were between 21 and less than 30 years old and got 31.4% of the journalists who held bachelor’s degrees got 89.9 %. Less than 5 years of journalistic experience earned 23.4 percent. About the job position, editor (12.8%), reporter (12.8%), Head of the Department (25%), Editor in Chief (2.1%), photographer (16.5%), and writer (20.7%) were the most common (see, ).

Table 1. The sample

Data analysis. The questionnaires were coded using the SPSS data matrix. The following analysis was undertaken with each sample: calculating the relative weight of the items measured on the “Triple Likert” scale, by calculating the arithmetic mean for them, then multiplying the results by 100 and then dividing the results by the maximum degrees of the scale. A T-Test was used to test the statistical significance of the differences between the means of two sets of data. The One-Way Anova Test tests the statistical significance of the differences between the averages of more than two sets of data. The Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated to find out the relationship between the two variables.

5. Results

5.1. Journalists’ perception of press freedom

shows that journalists, due to editorial policy, have the power to restrict reporting on sensitive topics with 70.2 %. The semi-governmental newspapers got 72.1% and the private newspapers got 68.6 %. The restrictive press law in Egypt 69.1 %, 69.8 % in the semi-governmental, while private newspapers got 68.6 %. The ratios between the topics and the law restrict reporting on sensitive topics by 65.4 %. These penalties for ‘irresponsible journalism” is applied widely with 53.2 %, 56.9%, and 47.9 % of the newspaper being interested in promoting news about the previous regime’s Muslim Brotherhood. Furthermore, 36.2% of the newspaper considers the audience’s interests and desires, and the ratio between semi-governmental and private newspapers is 36. Then 30.9 percent of the restrictions on media freedom are closely proportional to the government’s legitimate aim, and the authorities restrict legitimate press coverage in the name of national security interests.

Table 2. The laws restrict reporting

Online journalism in Egypt often faces serious resistance from the government authorities in an emerging democracy (M. A. Mohamed, Citation2010; Altoukhi, Citation2002). Within this context, journalists seek to acquire information from confidential sources without protection from the government, which affects their newsgathering and publishing. Eid (Citation2019) pointed out that the government was struggling to control online sources and it was an area in the press that could not make progress. Furthermore, developments in information law in emerging democracies have been slow (Ahmed, Citation2019). Furthermore, as already noted, the government was constantly threatening online newspapers (Khodary, Citation2015). It is also looking at different ways to clamp down on the controllable diffusion of information (Hussein, Citation2018).

shows the factors affecting journalists’ punishment by editors with 72.9 %, while the government follows us with 71.8 %, and lack of sources and the influence of bosses at work by 63.8 %, followed by press law hindering work and the newspaper’s editorial policy with 36.2 %.

Table 3. Factors affecting journalists’ decisions while covering and publishing news

The value of Chi-Squared was 0.031, which is not statistically significant (P > 0.05); degrees of freedom = 2, p-value = 0.985. Most of the journalists, regardless of the institutions in which they work, participated in pointing out the lack of an environment in these newspapers.

On whether the press in Egypt is free to air its views, 30% of the total respondents pointed out that, to some extent, the media law was free with limitations to those who had access to them but was also based on a political basis. 70% of the total respondents said that the press was not free to air its views in Egypt, because the law that was currently in place deprived them of certain information, especially on political issues.

This finding is neither surprising nor contradictory. As indicated above, the principal sources of threats to the press are governments for political reasons and media organizations or owners. This percentage confirms Khayun’s (Citation2019) results that show that Al-Masry Al-Youm7 newspaper published the headline on 29 March 2018. The Supreme Council for Media Regulation decided to fine the newspaper LE 150,000 because the Council considered it an accusation against the state. According to this, the authority regarding violations of digital rights is governed by violations of freedom of digital expression and censorship. However, there were mixed reactions from those interviewed about how the law restricts freedom of information.

For instance, asking the journalists about the limitations and penalties for libelling officials or the state and which are enforced by the government revealed that 78.7 % and 59.3 % of the respondents’ views were that the press in Egypt was not free because those who formulated and implemented the law were selected on political grounds to suppress opponents in the political sphere. Information about the limitations and penalties for libelling officials or the state and whether they are enforced, for instance, X2 = 0.031, D. F = 2, significance = 0.985 (see, ).

Table 4. The limitation and penalties for libeling officials or the state and are they enforced

This finding shows that the media scene in Egypt is changing constantly and rapidly in view of the law controlling media content provided by different ownership patterns. However, regardless of semi-governmental and private newspapers’ concentration, other intervening variables may impact media content in a generally restricted media environment.

6. Knowledge of Egyptian media law

Respondents were asked about their awareness of the current media law in Egypt, and 74.5 % said they know about most of the Egyptian law because the Egyptian syndicate gives them awareness courses, while 25.5 % had little awareness of the current media law. The insignificance of the relationship between the newspaper’s classification (semi-government /Private) and the awareness of the current media law, is demonstrated because the value of Chi-Squared was 0.000, which is not a statistically significant value (P > 0.05); degrees of freedom = 1, p-value = 0.989.

Asking the journalists whether Anti-Cyber and Information Technology Crimes Legislation provides protection to them, the journalists responded that the law was unfair to them 39.9% of the responses while most of them said it is not clear 20.8 %.

The statistical indicators also reveal the insignificance of the relationship between the newspapers’ (semi-governmental/private) and journalists’) evaluation of the law, where the value of X^2 = 1.325, which is not statistically significant (P > 0.05); the majority of journalists have argued that the law is unfair to journalists. Information about the Anti-Cyber and Information Technology Crimes legislation and Egyptian Data Protection Law provides journalists with clarity, not clarity, missing parts, fairness, and unfairness to journalists. The statistical indicators also reveal the insignificance of the relationship between the newspaper’s rating (semi-governmental/private) and journalists’ evaluation of the law, where the value of X^2 = 1.325, which is not statistically significant (P > 0.05); most of the journalists have argued that the law is unfair to journalists (see, ).

Table 5. Does anti-cyber, and information technology crimes legislation provide journalists

Similarly, Alyaqoubi (Citation2019) noted that the government plays a key role in determining levels of media freedom. Almost every journalist interviewed, from both semi-governmental and private media houses, mentioned that information about government institutions is difficult to access and dangerous to criticize

The findings of the analysis of the restriction on freedom of information are shown in (see, ). that the law guarantees access to government records and information by 89.9 %. The law obstructs journalists to publish and restricts the right of access to the information expressly and narrowly defined, with rates of 83 % and 82.4 %. The percentages converged about journalists subject to prosecution if they illegally refuse to disclose state documents and the rights to freedom of expression and information recognized as important among members of the judiciary was expressed by 79.8 % of the journalists and finally, the law obstructing journalists to withhold information was quoted by 76.1 % of them.

Table 6. Laws restrict freedom of information

There is no statistically significant relationship between the negative aspects of the law according to the variables of age, education, and experience, as the value is greater than 5%, and N = 188. According to the age of journalists p-value = (−0.055, 1); Sig = 2; and N = 188. In addition, about education level P = −.041-.value = 106; N = 188. So, the SD is 5.7181 and M = 1.83265. The information about laws restricts freedom of Information. For instance, X^2 = 0.000 = , D.F. = 1, significance = 0.989.

This finding is neither surprising nor contradictory as, indicated above, the principal source of threats to the press are governments for political reasons and media organizations or owners.

7. Law seeks to attack the integrity of information networks, systems, and technologies

Analysis reveals information about the provisions of the third chapter on crimes and penalties in the law (see, ). According to the analysis’s respondents, 68.6% of journalists report an assault on the integrity of information networks; 59.6% report exceeding the limits of their right to enter websites; and 53.2% report illegal access to any website.

Table 7. Laws seek to attack the integrity of information networks, systems, and technologies

Comments about the crime of unlawful objection to websites and news came to 53.2 %, followed by the crime of attacking the integrity of information systems with 51.6 % of responses, then the crime of unrightfully using communications and information services and technology with 41.5%, followed by the crime of attacking e-mail, websites, or private accounts with 38.8 % of the responses.

The crime of attacking the design of the journalistic website received a 31.43% and the crime of attacking the country’s information systems, a 27.1%. The attack on the integrity of information networks scored 68.6 % of the responses, followed by the crime of exceeding the limits of the right to access websites with 59.6 % and finally the crime of illegal access to any website with 53.2 %. The value for the number of judgments known by the chosen journalists is 1, and the largest value is 7 out of 10 judgments.

The average value is approximately 5 judgments, meaning that the average value is far from the largest value, which confirms that the percentage of knowledge of the provisions of Chapter Three in the law is very weak. There is no statistically significant relationship between the provisions of Chapter Three in the law on crimes and penalties. According to the Pearson correlation, journalists’ perceptions were p = 1; N = 188, age P = −0.029; t = 0.696; N = 188, education P = −0.062; t = 0.398; N = 188, experience P = 0.012; t = 0.875; N = 188.

Examining the law that seeks to undermine the integrity of information networks, systems, and technologies, S. D = 1.79; M = 59.7%; 25.6% agree, 46.5% disagree, and 27.9% are neutral. In the case of private newspapers, the results were: M = 34.3%; S.D. 50%; agree 61.4%; disagree 18.4%; neutral 15.7%Act 14: The Crime of Exceeding the Limits of the Right to Access the Network and Information Systems Act 15: The offence of illegal entry is punishable by imprisonment for a period of no less than one year and a fine, 16.3 % agree; disagree 46.5 %; neutral 37.2 %; S.D 1.70; M = 56.6 %. In the case of private newspapers, 17.6% agree, 51% disagree, and 31.4% are neutral; S.D. 1.67; M = 55.6%.

The outcomes were as follows: 100% disagree; M = 33.3%; S. D1. In addition, under Act 17: The crime of violating the integrity of data, information, and information systems is punishable by imprisonment in semi government disagree 100; M = 33.3%; S.D = 1; and agree with 2%. 89.2% are neutral.1.13; M = 37.6%. Act 18: The offence of attacking e-mail, websites, or private accounts is punishable by imprisonment. 1.2% agreed with the statement, 94.2% disagreed, and 4.7% were neutral.S.D = 1.07; M = 35.7%.In private newspapers, 3.9% agreed, 87.3% disagreed, and 8.8% were neutral; S.D. 1.17; M = 38.9%.For Act 19: The offence of attacking the design of the website in the semi-government newspapers, the results were: disagree 72.1%; neutral 27.9%; S.D 1.28; M = 42.6 %, while the results for the private newspapers were: agree 2 %; disagree 67.6 %; neutral 30.4 %; S.D 1.34; M = 44.8 %.

Asking the journalists about censorship, self-censorship, and the violations of freedom of information after the activation of the law, the ratios between the obstacles to newspaper issuance, printing, distribution, and publishing were close to 75%, and private newspapers ranked 74.5 % higher than semi-governmental newspapers by 75.6 %, followed by the treatment of editorial material at rates of 43.1 %, and newspapers came by 74.5 %. Private newspapers account for 43.1%, while semi-government newspapers account for 43.1%.

The laws seek to attack the integrity of information networks, systems, and technologies. The average agreement according to the type of newspaper is between 1 and 1.5, and this confirms that the percentage of support is not agreed, as shown previously. It is also clear that there is a moral difference between the opinions of journalists and the agreements according to the type of newspaper, with 95% confidence, as the p < .05.

This finding represents after the Law media are tightening their grip on the internet public sphere, self-censorship impacted newsroom dynamics and blocked around 500 websites.

The Egyptian law promotes excessive government control over both categories to media houses, as well as intimidation of media personnel through direct legal harassment, thereby impacting negatively on the journalistic work. Previous research (Alyaqoubi, Citation2019; AlZaftawi, Citation2019; Ashour, Citation2020) revealed that these legislative law developments have a significant impact on the journalists’ violations, in terms of digital rights and media freedom issues, by using the Supreme Council for media regulation, they have the authorities who impose those restrictions in (monitoring and documentation unit).

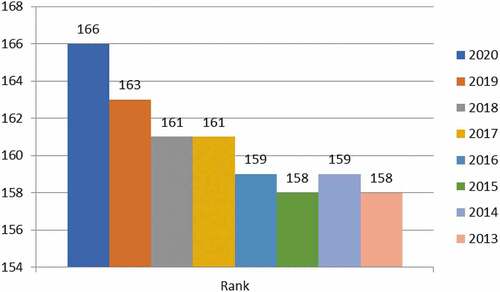

The results indicated that journalists fear persecution under these “draconian” laws. This notion manifests in the Authoritarian theory which applies in dictatorial societies such as Egypt, these findings are consistent with the World Press Freedom Index which shows Egypt ranking “166 out of 180” in 2020, then decreased by three points down in 2019 from 163 compared in 2013 after the revolution with 158 in 2013. This indicates that the restrictions on freedoms are increasing by three points or more every year, because of laws that restrict journalists (See, ).

8. Discussion

The analysis of the Egyptian Law shows the authorities control the data by law and restrict journalists’ and journalistic practice. The government does not give space to journalists to work in a professional environment.

This study is the first conducted among such journalists in Egypt when they establish the law; it was found that its findings came in line with some earlier studies which analysed media law and editorial policy (e.g., AlAshry, Citation2020). It found that in the post-transition era since 2014, the government has steadily introduced new strategies to the press and politics in Egypt seeking to control information, which has a liberalizing effect on publishing.

Based on the findings of this study, about the factors affecting journalists’ decisions during coverage and publication, 72.9 % of journalists were exposed to sanctions. In addition, it is the most significant barrier faced by journalists, followed by a lack of information sources, and a lack of credibility of the news sources given by the governments. This demonstrates that the authoritarian system has significant disadvantages in terms of freedom of information, which has been limited over the last four decades, and Egyptian journalists are unable to freely discuss political issues and have access to diverse and critical media.

The finding shows that media institutions are fragile in the absence of a democratic political culture. 70% of respondents showed there are huge restrictions on press freedom, and journalists indicated scepticism about the significant changes in media policy without political consensus.

Freedom of the media is being affected by the presence of hostile politics, media regulations, and the law. In addition to the limitations imposed by governments, 78.7 percent of respondents stated that some journalists had been arrested and tortured, demonstrating the absence of any consensus model of democracy.

(AlAshry, Citation2022; Altoukhi, Citation2002; A. Mohamed, Citation2016) regarding provisions related to press freedom under the law, such as the law of contempt and libel, the stress should be not so much on the freedom of the press, but on a “free and responsible press.”

In addition, the law seeks to attack the integrity of information networks, systems, and technologies in the provisions of the third chapter on crimes and penalties in the law, with a percentage of 68.6 percent of respondents agreeing. Although these results support those by AlAshry,, (Citation2022)they contrast with Abdul-Jalil (Citation2019) who found that the Egyptian legislative structure lacks a special law that protects anti-cyber and information technology crimes.

On the other hand, the law should include many provisions to protect journalists, as government sources remain the most important. Furthermore, regarding censorship, self-censorship, and the violations of freedom of information after the activation of the law, the ratios between the obstacles to newspaper issuance, printing, distribution, and publishing were close to 75%.

Some journalists argue that because of draconian laws, they are forced to report with a bias towards certain privileged sections and they are subject to the government; most of these journalists fear persecution. This notion was further supported by the digital authoritarianism theory, which applies in dictatorial societies such as Egypt.

Although these results support (AlAshry, Citation2018, Citation2022), they found that there is a real structural and political system in Egypt that hinders the ability of journalists to claim their right to information for public services. Internet censorship in Egypt is not a new phenomenon. Freedom of expression facilitated by online newspapers can pose a threat to authoritarian leaders who seek to maintain strict control over the content produced and consumed by their citizens.

It is clear from the results that media institutions in Egypt are fragile in the absence of democratic politics. Law changes to change society may restrict journalists and not give them more freedom. The lack of democracy reinforces this fragility. The media is affected by the presence of hostile policies and media regimes. Information and dissemination of information undermine freedom of expression in Egypt by promoting excessive government control over semi-governmental and private newspapers as well as intimidating media workers. Dozens of journalists were subjected to direct legal arbitrary dismissal, detention as journalists, and bans from practising the profession, which negatively affected the profession.

Closing the space for freedom of opinion and expression in Egypt is part of a government strategy to restrict journalists under the pretext of preserving national security and the public, which has resulted in the closure of many media houses.

9. Conclusion

The starkest example of journalists’ censorship is Egypt’s passage of a new cybercrime law that infringes on citizens’ rights. The law, which aims to combat extremism and terrorism, allows authorities to block websites that are considered “a threat to national security”. The government has described the law as necessary to tackle instability and protect the Egyptian state, while also protecting citizens’ and companies’ data.

Journalists who post links to government websites can face steep fines and penalties. In addition, there are other measures of the law that impose strict penalties for hacking government systems. The government has been restricting journalists, bloggers, and media organizations under the law. If you have more than 5,000 followers and publish fake news, it is called incitement to break the law.

Finally, these laws are quite clearly in serious breach of the rights to freedom of expression and freedom of information as guaranteed under international law. These media laws significantly fail to strike a balance between the legitimate journalism work of the state and the rights to democracy. While emphasizing the significance of the research by analysed internet censorship in Egypt is not a new phenomenon, the authoritarian leaders seek strict control of the content to limit citizens’ freedoms by the passage of a new cybercrime law that infringes on citizens’ rights under the name of national security, which ostensibly aims to combat extremism and terrorism and allows authorities to block websites that are considered “a threat to national security”. There exists a clear trend in Egypt’s government’s seeking to control content deemed threatening, which offers an avenue to build continued repression into the media legal system.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdul-Jalil, I. S. (2019). Civil liability for damages resulting from the use of news websites [ Doctoral dissertation]. Faculty of Law, Department of Civil Law. [Electronic resource]. https://law.tanta.edu.eg/faculty_conference/files

- Ahmed, G. S. (2019). Legislative frameworks for journalism in the Arab Republic of Egypt and South Africa [ Doctoral Thesis]. Faculty of Mass Communication, Department of Journalism.

- AlAshry, M. S. (2018). The conflict between journalists and the constitution of 2014 in Egypt. Global Media Journal, 31(1), 16–17. https://www.globalmediajournal.com/peer-reviewed/the-conflict-between-journalists-and-the-constitution-of-2014-in-egypt-87277.html

- AlAshry, M. S. (2020). Attitudes towards law no. 175 of 2018 regarding anti-cyber and information technology crimes concerning journalistic practices. Media Research Journal, 55(1), 249–332. https://doi.org/10.21608/JSB.2020.115651

- AlAshry, M. S. (2022). The impact of the new Egyptian communicable diseases law on the work of journalists and media organizations. Journal of Legal, Ethical and Regulatory Issues, 25(4), 1–14. https://abacademies.org/articles/the-impact-of-the-new-egyptian-communicable-diseases-1544-0044-25-4-197.pdf

- AlAshry, M. S. (2022). Investigating the efficacy of the Egyptian data protection law on media freedom: Journalists’ perceptions. Communication & Society, 35(1), 101–118. https://doi.org/10.15581/003.35.1.101-118

- Altoukhi, S. (2002). Administrative research. Sadat Academy for Administrative Sciences, 5(2), 2–215. https://www.doi.org/http://sams.edu.eg/crdc/magazine.

- Álvarez, J. M. (2014). Journalism and literature in the Egyptian revolution of 1882. SAGE Open, 4(3), 215824401454974. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014549742

- Alyaqoubi, M. (2019). Criminal protection for informational evidence [ Unpublished thesis]. Faculty of Law, Department of Criminal Law

- AlZaftawi, H. L. (2019). Intellectual property rights for Arab intellectual production available on the Internet [ Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. College of Arts. Department of Libraries and

- Ashour, K. (2020). Egypt media in international indices and reports. Egyptian Institute for Studies. [Electronic resource]. https://en.eipss-eg.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Egypt-Media-in-International-Indices-and-Reports-2020.pdf

- Belgacem, M. (2019). The right of access to information in Egypt, Libya, and Tunisia. Democratic transition and human rights support center. Democratic Transition and Human Rights Support Center. [Electronic resource]. https://daamdth.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/data-acces-englais.pdf

- Bosch, T., & Roberts, T. (2021). Case study: Digital citizenship or digital authoritarianism? Oecd Ilibrary. [Electronic resource]. https://doi.org/10.1787/1b3dc767-en

- Dragu, T., & Lupu, Y. (2021). Digital authoritarianism and the future of human rights. International Organization, 75(4), 991–1017. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0020818320000624

- Eid, A. S. (2019). The legal container for the technical evidence in the framework of establishing electronic crime [dissertation]. Faculty of Law, Department of Criminal Law.

- Fuchs, C. (2022). slow media: How to renew debate in the age of digital authoritarianism (1st ed.). Digital Fascism, 301–303. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003256090-16

- Hussein, H. M. (2018). Criminal responsibility for misusing social media sites an Analytical and comparative study. Arab Democratic Center Berlin, 2(211), 7–18. https://democraticac.de/?p=52839

- Ibrahim, M. S. (2019). Harmonizing freedom of the press and Preserving [ Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Public Faculty of Law, Public Law Department.

- Khamis, S. (2007). The role of new Arab satellite channels in fostering intercultural dialogue: Can Al Jazeera English Bridge the Gap? In Seib, P. (Ed.), New Media and the New Middle East (pp. 39–51). Palgrave Macmillan Series in International Political Communication. Palgrave Macmillan, New York.https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230605602_3

- Khayun, O. M. (2019). Legal protection of the right to privacy in light of modern technologies [ Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Faculty of Law, Department of Civil Law

- Khodary, Y. (2015). Public participation: Case studies on Egypt’s right to information draft law and national plan. Danish Institute for Human Rights, 2–23. https://www.humanrights.dk/sites/humanrights.dk/files/media/migrated/discussion_paper_khodary_2015_final.pdf

- Mohamed, M. A. (2010). Information systems transparency. Al-Rafidain Development, 23(33), 2–322.

- Mohamed, A. (2016). A field study for the freedom of information circulation in achieving administrative transparency. Education, 20(168), 2–24. https://jsrep.journals.ekb.eg

- Mohiuddin, S. M. (2019). The right to privacy and impact with modern technologies, for criminal protection of informational evidence [ Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Faculty of Law, Department of Civil Law.

- Philp, R. (2021). Tips to uncover the spy tech your government buys. Global Investigative Journalism Network. Retrieved September 21, 2021, from https://gijn.org/2021/07/14/tips-to-uncover-the-spy-tech-your-government-buys/

- Siddiq, R. A. (2015). Newspaper in the history of Egyptian journalism. Journalism Research, 5(45), 20–55.

- Siddiq, R. A. (2016). The Egyptian press’s position on the national unity from 1881 to1919. The Egyptian Journal for Public Opinion, 3(255), 27–50.