Abstract

This paper focuses on Li Zicheng, a serial long comic story in China’s 1980s. The work was released between the post-Mao and pre-89 eras in the history of the Socialist China, a period known for the increasing liberalization of its society. Meanwhile, it was derived from a renowned socialist literary work of the 1960s, which uses the theme of ancient peasant wars as a metaphor for modern communist revolution and catering to the prevailing ideology of the time. Focusing on visuality, this study concludes through visual grammar analysis that the revolutionary narrative is implicitly diminished in the comics’ narrative space. This finding reveals a microcosm of the way in which literary artists in the early years of reform and opening up received and adapted the revolutionary cultural heritage of the Mao era. With this conclusion the paper attempts to offer an innovative way of interpreting the inheritance and transformation of Chinese socialist culture in the post-revolutionary transition era.

1. Introduction

Boasting 27 volumes, the Li Zicheng 李自成 series (1978–1987) released by Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Publishing House is the fourth longest Chinese historical work in the history of Lianhuanhua 连环画.Footnote1 While the three lengthy series that preceded it were based on Chinese classical literature, the Li Zicheng series, despite being an epic, was adapted from a modern novel, more specifically, from 1960s socialist literature of the same name.Footnote2 The Li Zicheng series can be seen as the product of the intersection of three eras: pre-modern China, Mao-era China and post-Mao-era China. The content of its stories about peasant uprisings shows the historical and cultural background of ancient China; its original novels were influenced by Maoist ideology, with an emphasis on class struggle and historical materialism; and it was published at a time when China was undergoing reform and opening up, with enormous political, economic and socio-cultural changes taking place. Arguably, the Li Zicheng series represents the complexity and multifaceted nature of the relationship between popular culture and politics in post-revolutionary transition China.

As a folk-derived picture book, Lianhuanhua served two key functions in twentieth-century China: to create an aesthetic experience for a mass audience and to promote literacy and knowledge in order to reduce illiteracy, making Lianhuanhua a sort of textbook for popular education. Meanwhile, Lianhuanhua was a visual record of the country’s historical past in the form of popular culture, owing to its great publishing volume and widespread popularity. Lianhuanhua covers a wide range of subject matter, wherein Chinese classical and folk tales make up a sizable proportion. However, the traditional stories that made it into the Lianhuanhua after 1949 have been selective, as they have to refer back to the ideologies of the Maoism era.

During the first 30 years of the People’s Republic of China, Lianhuanhua as a mass culture carried much of the revolutionary discourse of Chinese socialist practice.Footnote3 Revolutionary narratives, as a narrative genre focusing on China’s modernity, often incorporate the origins, nature, and goals of revolution from the perspective of revolutionaries into a grand historical formula. Heroes associate themselves with the time to which they belong and understand their activities as a means to reach a certain ultimate goal. Mao Zedong’s classic interpretation of revolution, that “a revolution is an insurrection, an act of violence by which one class overthrows another,”Footnote4 clearly pointed that violent confrontation is necessary for revolution. The predominance of revolutionary struggle themes in the Mao-era Lianhuanhua story genre, which were composed of masculinity and militancy, made it difficult for traditional themes that did not fit the revolutionary narrative to enter Lianhuanhua.Footnote5

In the 1980s, Lianhuanhua ushered in a new phase of development that yielded the emergence of a richer and broader spectrum of story genres than before. On the surface, this new situation was brought about by the loosening of cultural authoritarianism following the end of the Cultural Revolution. However, the deeper context was that Maoism was no longer at the heart of the strict regulation of state opinion but had not yet been withdrawn from the public’s collective memory. Consequently, to examine whether Lianhuanhua Li Zicheng, which emerged from this trend, still belongs to the category of revolutionary narratives becomes the main purpose of this paper.

The 1980s were among the most significant transitional periods in Chinese society, signaling the end of the Cold War’s “closed” period and the start of China’s admission into the global capital market as a socialist country. The most important feature of this period of transition was, as Dai Jinhua put it, a “structural fissure,” which meant “a continuation of the regime, an ideological rupture, and a change in social institutions.”Footnote6 While the period saw significant changes in ideological content as well as in the political, economic, and social structure of the country, this time it was not a dynastic change but a continuation of the communist regime that still drew on the orthodox Maoist political discourse. It is therefore problematic to see the Maoist and post-Maoist eras as two distinctly different eras; after all, the Communist regime was achieved through revolution, and the revolutionary narrative was an important propaganda for articulating the historical inevitability, correctness and rationality of the Party-led path of revolution and liberation. As a result of the story that has been adapted into different genres and mediums across time from novel to comic, the ideological schism and continuity brought by this comic series is deserving of in-depth research as a case study of cultural and social trends in China’s post-revolutionary age.

The plot of the Li Zicheng Lianhuanhua series was largely faithful to the original, with no noticeable alterations. The positive image of the peasant army, as represented by Li Zicheng, features prominently in much of the story. However, compared with coetaneous novels, the original was not a very standard “red novel” because from the historical point of view, Li Zicheng’s uprising ultimately failed, which contradicts the revolutionary literature’s “victory narrative.”Footnote7 Moreover, although the author of the original book used the pre-modern Peasant War as the main plot to allude to China’s modern revolution, the novel possesses some deviations from the Maoist line due to the differences in its pre-modern historical setting, such as feudal morality and traditional ethics.

It is only in the novel that these classical Chinese values are not given focus to the point of being very conspicuous. Nevertheless, based on my close reading and content analysis, these conflicting storylines about traditional Chinese ethics (father and son, ruler and subjects) are visually amplified in the 1980s comic version. These “classical” dramatic conflicts somewhat undercut the purpose of revolutionary propaganda: to worship revolutionary leaders and to hate enemies of revolutionary regimes. As a conclusion, this paper argues that these changes have undoubtedly added complexity to the comic series and has allowed for a limited de-propaganda of this once highly propagandized story in a new age context.

2. Between peasant war epic and revolutionary literature

Li Zicheng was the leader of a late Ming Dynasty peasant insurrection (1629–1645), which was one of the largest in Chinese history. Poets, storytellers, novelists, and opera writers have used a romanticized tone throughout the ages when describing the significant figures and events that occurred during this turbulent history.Footnote8 Until the 20th century, some novelists still employed this historical transition as the subject matter of their works. The novel Li Zicheng by Yao Xueyin 姚雪垠 (1910–1999), which serves as the primary source material for this comic, is the longest and, to a significant extent, the most complete among works on the alternating period between the Ming and Qing dynasties.

The first three volumes of the novel on which the comic is based were written before 1976, and it was the only ancient historical full-length novel in the literary creation of the Mao era.Footnote9 To demonstrate the huge historical transformation that was caused by dynastic change, he takes the uprising of the peasants as the central event. An important conclusion reached from the Marxist materialistic view on Chinese history was the peasant uprisings and peasant wars being the driving force behind the development of pre-modern Chinese society.Footnote10 This judgment and interpretation of the historical law made the literary and artistic movements during Seventeen Years (1949–1966) and Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) in China a priority to shape the typical heroes of the proletariat revolution in the class struggle.Footnote11 From a wide number of documents, Yao Xueyin evidently favored and embraced this idea and participated in the cultural construction of this Sinicized Marxism with Li Zicheng.Footnote12 In particular, Li Zicheng is not an ordinary historical figure, but one favored by Mao Zedong, who has repeatedly used the peasant uprising led by Li Zicheng as a metaphor for the Communist Party’s ranks since the 1940s. Thus, Yao’s creation of Li Zicheng actually had Mao’s support. However, whether the novel could be classified as “revolutionary literature” was later debated several times.

Although the first volume of the novel Li Zicheng was published in 1963, the author’s labeling as a politically unreliable “rightist” at the time prevented the novel from receiving as much publicity and promotion as other famous novels of the same generation, such as Song of Youth (1958), Red Rock (1961) and The Great Change in the Mountain Country (1958), until 1976. Nor was it the subject of Lianhuanhua adaptations as others had been until 1978. It was only after the end of the Cultural Revolution that Yao Xueyin’s political “complete liberation” led to a less restrictive review of Li Zicheng. The novel became famous in the late 1970s and was even praised by the highest leader, Deng Xiaoping. In 1982, the work’s reputation reached its peak when it won the Mao Dun Literary Award, the highest official literary prize in China. Up to this point (early 1980s), literary critics and the general public still compared it to classical Chinese literature such as The Romance of the Three Kingdoms and The Water Margin, rather than considering it “revolutionary literature”.Footnote13

In the late 1980s, as the social climate and cultural environment gradually changed, the classic value of Li Zicheng was shaken, and the decisive factor in this shaking came from the academic community. The earliest person to label Li Zicheng as revolutionary literature was the cultural studies scholar Liu Zaifu. In a review published in 1988, he argued that Li Zicheng was the embodiment of Maoist revolutionary ideology in its portrayal of characters and literary concepts, and compared the novel to the “model operas” of the Cultural Revolution as a work representing cultural authoritarianism.Footnote14

Similar opinions have been expressed since then by both general readers and literary scholars. In fact, behind the re-evaluation of Li Zicheng was actually a re-examination of Maoist thought by the Chinese intelligentsia in the post-revolutionary era, including a questioning of the relationship between the peasant movement and historical materialism in ancient history.Footnote15 Thus, in reviews after the late 1980s, the assertion that Li Zicheng belongs to revolutionary literature essentially became the dominant view. For example, the literary historian Hong Zicheng in A history of Contemporary Chinese Literature explicitly states that the novel “should be classified as a modern ‘revolutionary historical novel’”.Footnote16

Back in the late 1970s, the Lianhuanhua Li Zicheng was launched in response to the heyday of the novel’s reputation. From its length and the line-up of artists (essentially the leading Lianhuanhua artists of the time) shows the importance that the People’s Fine Arts Publishing House attached to the project. It is worth noting that the final volume of this series was completed in 1987, just before the original novel began to receive negative criticism. The creation of the series was therefore not influenced by the negative criticism of the original novel, which allowed the series to reflect the creators’ visual attitudes towards the text of the story in a relatively pure manner.

The comic’s basic storyline centered on the gradual strengthening of a small peasant army throughout the course of the uprising. Similar to the original novel, the protagonist Li Zicheng was portrayed as a peasant hero from the perspective of the proletariat. The conflict between the peasant army and the Ming Dynasty was portrayed as a struggle between progressive and reactionary forces in the omniscient perspective. The Lianhuanhua rendition of Li Zicheng was still a conventional class struggle pattern from a narrative standpoint, but in the era of the rapid transformation of both ideological background and readership, this narrative mode has been questioned and altered to some extent.

3. Visual narrative of the Lianhuanhua

While scholarship and debate about the original novel is abundant, this comic adaptation has had a near void of scholarly attention, an imbalance that has perhaps been caused by the hierarchy between novels and Lianhuanhua. Lianhuanhua has few original scripts and relies almost entirely on literary adaptations, which is unique in the genre of pictorial narrative art. Hence, Lianhuanhua is also known as “secondary literature” (ershou wenxue 二手文学).Footnote17 However, as with film adaptations, the “secondary literature” of the same story tends to have a wider readership and greater social impact than the original over a long period.

In analyzing narrative form, Martin Barker’s typified readership theory can be instructive. Martin Barker thinks that reader reactions to plots and characters, as well as the unique production histories that give rise to individual works, are central to any thorough analysis.Footnote18 Given this case, the typical post-Mao reader was bound to have different expectations than the reader of novels from the previous era. I argue that the different positions and typified readership conceived by Li Zicheng in two periods constitute a reference to the changing socio-political formations within Chinese society. Therefore, the validity of this article’s argument must be confirmed by clarifying how Lianhuanhua storytelling differs from that of novel texts.

Lianhuanhua is a form of narrative art combining words and images. Within the internal structure of Lianhuanhua, images are more important than textual scripts, as this popular reading serves mainly people of low literacy.Footnote19 In other words, Lianhuanhua readers rely more on images to make sense of the story. The visual language of Lianhuanhua has both traditional and modern roots. First, in its form, Lianhuanhua was born out of the illustrations in 15th-18th century Chinese novels, which are often used as annotations and additions to the text.Footnote20 Even after Lianhuanhua gained its own name in the 1920s, this annotative pictorial form continued, usually in the form of one image per page with additional text, which is the most important feature that distinguishes Lianhuanhua from other comics.

Second, influenced by the 20th century Chinese revolution and, in particular, the triumph of communism, the artistic style of Lianhuanhua after the 1950s drew largely from socialist realismtinged with the political mission of socialism. This inspiration is also reflected in the Li Zicheng series in some of the group portraits, which are easily reminiscent of a revolutionary-themed narrative work. Thus, the modern Lianhuanhua is like a combination of east and west: formally following traditional Chinese illustrations while stylistically blending realism from the West and Soviet Russia. Despite some modernized development, Lianhuanhua’s visual format remains closer to traditional novel illustrations: its representation was still not a transposition or translation of the original text but an annotation that reflects a secondary selection and emphasis. Therefore, I assert the necessity to regard the Lianhuanhua (especially the longer series) as a collection of annotative images to comprehend its expressive content that secondarily constructed the characters of the story.

The coding of these annotative images is necessary if Lianhuanhua is to be subsequently analyzed for its content given the large volume of output. The main component of Lianhuanhua’s visual texts since time immemorial has always been the portraits that depict the personality, actions, and thoughts of the characters.Footnote21 The coded labels or categories for constructing portraits can be based on the two types of Lianhuanhua predecessors. As the cultural matrix of Lianhuanhua, traditional Chinese novel illustrations have two main types: fine-lined portraits (xiuxiang 绣像) and panoramic views (quantu 全图).Footnote22

A fine-lined portrait is usually an individual portrait used to visualize the personality, features and appearance of the main character in fine detail, while a panoramic view is an overall view showing the plot, usually containing multiple characters and scenes. Many popular novels are illustrated with a combination of fine-lined portraits and panoramic view, such as Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Dream of the Red Chamber, and The West Chamber.Footnote23 In general, a book has more panoramic views than fine-lined portraits, as is the case in modern Lianhuanhua. Drawing on Painter et al.‘s ideas about visual attitudes, the difference in the number of fine-lined portraits and panoramic view represents a Visual Gradation, which affects the visual privileges and weights of the characters.Footnote24 In summary, if a descriptive label system were to be encoded for multi-character Lianhuanhua, the categorization of individual/group characters (as in the case of fine-lined portraits/panoramic views) would be most appropriate, as only important characters would have a higher frequency of reappearing as individual portraits.

4. Visual content and “prominent characters”

Given the context in which the original novel was born, investigating what the subject is and who the main characters are seems unnecessary. The most “correct” story in the Maoist era embodied the main contradiction in the laws of history (historical materialism). However, as I mentioned in the previous section, the “correctness” of the post-Mao era has changed, and the “typified readership” of the comic version was significantly different from that of the 1950s–1970s. The masses who lived through the Cultural Revolution would no longer expect a revolutionary education in popular culture from the previous era. Therefore, this section examines how the differences brought about by this post-Mao “second transmission” are reflected in the Li Zicheng Lianhuanhua through the content analysis approach. To exclude unconscious, preference-specific ways of interpretation (e.g., peasant uprising, class struggle), I treat this Lianhuanhua as a rich collection of visual material.

This story is not just a personal biography of Li Zicheng. Practically, the original novel has a highly complex and ambitious narrative, with more than 200 named characters in the first three volumes, thus showing a wide range of society in the late Ming Dynasty. In terms of the social landscape, the stories cover a broad range of areas, from the court to the people, from the capital to the countryside, from inside to outside the border, from politics to economics and the military, and from agriculture to labor. Although the comic version was one of the longer works (27 volumes) in Lianhuanhua’s history, it could not have contained all of the original’s nearly three million words, especially with the annotative images used to tell the story. In the Li Zicheng series, each volume contains around 150–200 pages, and volumes 1 through 27 have 4,862 images. The types of images could be classified into two categories: scenery based and character based. Like traditional novel illustrations, this Lianhuanhua has very few pure landscape images, and the vast majority of the illustrations contain characters. That is, characters and character relationships are the core of the series visual narrative.

The narrative perspective switches back and forth between the three groups: the peasant army, the Ming Dynasty, and the Qing Dynasty. The majority of the storylines throughout the entirety of the series are centered on the battles between the peasant army and the Ming army and also cover the war between the Ming and the Qing. Compared with the original novel, the characters and the plot of Lianhuanhua have been streamlined. Nevertheless, the story still contains a large cast of characters, including the following: a peasant army that consists of 31 characters, the Ming court side that has 12 characters, and the Qing side that has only two significant characters who are less involved (see Table ).

Table 1. Characters of the three groups

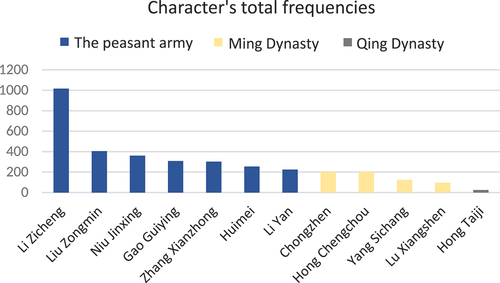

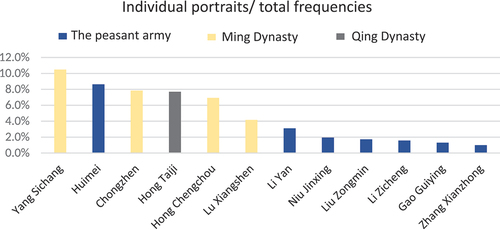

Considering merely the number of characters on each side, the peasant army is evidently the most prominent. The main narrative spotlight of the peasant army indeed highlights their positive image, which is consistent with the aesthetic framework of the class struggle. To confirm the weight of these characters throughout the series further, I counted the frequency of their appearance in all the images. According to Painter et al.‘s visual grammar of continuous image narratives, the visual repetition of a character helps the reader perceive the importance of the character.Footnote25 Figure shows the top 13 characters in terms of frequency of appearance. It shows the importance of Li Zicheng as the first protagonist, while the top seven are all peasant characters.

However, the expressive content of the graphic narrative is far from being summed up by the reappearing frequency of the characters. The cultural lineage and theoretical connotations of the images must also be traced. As the inheritors of traditional novel illustrations, the individual portraits (fine-lined portrait) in Lianhuanhua are also relatively rare. Such is the case in the Li Zicheng series, where most of the characters appear as part of a group portrait (panoramic view). In this way, I can assume that if a character has a higher frequency of individual portraits in Lianhuanhua, then that character can be deemed to have more visual weight. The ranking of the top 13 important characters has changed once the number of individual portraits was considered. Figure shows the ratio of each character’s personal portrait frequency to the total frequency, thus clearly showing a decreased significance of not only Li Zicheng’s visual weight but also that of the entire peasant army group.

In this way, the prominence of the peasant army groups, representing the proletariat, is overtaken by the rival group in the narrative space of Lianhuanhua, an unacceptable situation in the Mao era. One of the most famous political-aesthetic principle of the Mao era was the Three Prominences (san tuchu三突出), which guide literary creation in this way:

Among all characters, give prominence to the positive characters; among the positive characters, give prominence to the main heroic characters; among the main characters, give prominence to the most important character, namely, the central character.Footnote26

For a communist theoretician, as Li Xiuqin observes, ordinary people were no longer ordinary in socialist China, and typical characters tended to become typical heroic characters, drawn exclusively from the ranks of the proletarians.Footnote27 In terms of the revolutionary narrative, the positive, main and heroic characters must be the proletariat who fight against reactionary forces. However, in this Lianhuanhua story, some of the secondary, non-positive, and non-proletarian characters from the original novel receive increased visual weight without altering the narrative structure. As a result, this comic series deviates visually from the Three Prominences and from the artistic rule of highlighting typical characters (proletarian heroes) in typical circumstances (class struggle).

In addition to the frequencies they have been depicted individually, the characters’ appearance is another factor that should be taken into account. According to Painter et al. on the ideational meaning in visual narratives, picture book characters often need uniform external features to help readers identify the characters when they reappear, but changes in appearance (costumes) increase the drama of the characters and thus metaphorically change the symbolic attributes of the characters.Footnote28 With the development of the story, almost all the characters in Lianhuanhua keep their appearance and clothes unchanged so that the characters can preserve their characteristics. However, the change in appearance signifies the growth and transformation of the characters, which visually accentuates their “character arcs” that reinforce the emotional depth. Among the top 10 characters who have high frequency of individual portrait, the appearance of the four pathos characters undergo a very obvious visual change in the course of their struggle: their clothing, hairdo, and demeanor have altered dramatically, thus indicating that they are enduring psycho-emotional shocks (see Table ).

Table 2. Changes in appearance

Combining the two visual weights of individual portraits and appearance changes, I draw a summary of four characters who prominently stand out visually in this long-form comic: Huimei 慧梅, Yang Sichang 杨嗣昌, Lu Xiansheng 卢象升, and Hong Chengchou洪承畴. In the story, the destinies of these four characters are devastating. During the war, they were all committed to their respective monarchs. Except for Hong Chengchou, the other three died to prove their devotion to their ruler. Hong managed to live, but he spent the rest of his life carrying the stigma of a traitor. Of these four representative figures, three were members of the opposing group of the peasant army, which is uncommon for a comic depicting a “typical” peasant hero. Therefore, analyzing and exploring the plight and difficulties of these four characters have become the key point to understand the symbolic significance and cultural implications that are visually represented by this Lianhuanhua.

5. Conflict of characters

Within the framework of the class war, the four prominent characters, who stood out in their solo portraits, appeared in a number of secondary conflicts and plots. In addition, none of them could be classified as “typical characters” in revolutionary narratives from 1950–1970.Footnote29 Regarding their “class origins,” Huimei was a member of the peasant class, while the other three were members of the Confucian bureaucratic elite (landlord class). In addition, Huimei was a character that the novelist completely made up, whereas Lu, Hong, and Yang were all historical individuals that actually existed.Footnote30 The fact that such a minor fictitious character, who had not been regarded noteworthy even in the original novel, occupied the role of the protagonist in this comic for three volumes caused the tone of the entire series to be substantially impacted by the events of her plot.

As a “proletarian” character, Huimei’s sorrow was not one of class oppression but rather one of dominance. She was a war orphan who grew up in the peasant army by Li Zicheng and his wife. During the war, she honed her military expertise and combat instincts to become a formidable fighter. Huimei’s devotion to the military leadership was undeniable. In Volume 8, she nearly died after being shot by a poisoned arrow while passionately defending her adoptive mother in combat. As a supporting character, her private life and inner conflict were detailed in the comic (volumes 22, 23, and 27). Huimei and Zhang Nai, an orphan who also grew up in the peasant army, were in love. However, given the conventional principles, they could not express their feelings and hoped that their adoptive parents would arrange their marriage. However, Huimei’s marriage mirrored Li Zicheng’s monarchical despotism. From emperors to commoners, children’s weddings were arranged by their parents in traditional Chinese society. The increase of Li Zicheng’s army was the immediate cause of Huimei’s misfortune. He recruited other military leaders using his adoptive daughter, undermining the ideal of free love with monarchical and paternal values.

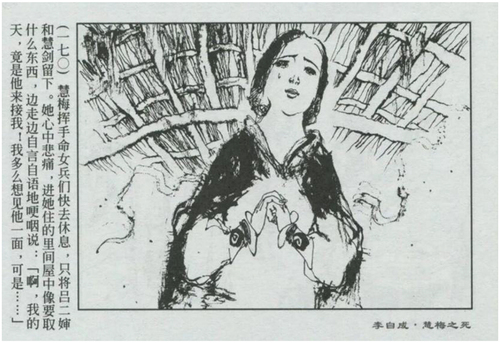

As a result, when Huimei’s adoptive father betrothed her to another, she had little choice but to submit. In Huimei’s visual representation, she is a brave and strong female warrior in the early stages (especially in battle). But in the episode of the marriage incident, her demeanor and physique are clearly shown to be fragile and powerless. Such a change in visual ideational meaning suggests that a heroine without much fear on the battlefield is unable to resist in the face of her ruling father’s authority. Li finally killed Huimei’s husband with the help of Huimei, and Huimei then committed suicide out of guilt and regret for having contributed to her husband’s death. In the final volume, aside from Huimei and Zhang Nai’s pain, the comic also illustrated the dilemma of Li Zicheng’s wife, who cherished Huimei but could not disobey her husband. The people surrounding Li Zicheng either obeyed the authority of the father and the monarch or obeyed the authority of the husband. They all had to swallow the bitter consequences together. Huimei ended her young life toward the end of the comic series, just as the peasant uprising was gaining strength, thus lending a tragic dimension to the work that celebrates the peasant revolution (see Figure ).

Figure 3. Li Zicheng, Volume 27: The Death of Huimei (Citation1987), Plate 170. Reproduced with the permission of Shanghai People’s Fine Arts publishing house.

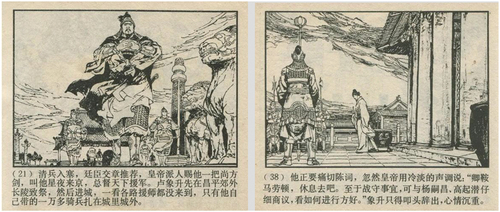

The battle against the Qing invasion was the focal point of the storylines of both Lu Xiangsheng and Hong Chengchou. The war between the Ming and the Qing was a background element in the comic’s plot, reflecting the corruption and incompetence of the Ming dynasty. Visually, Lu Xiangsheng was portrayed as a significant frontal figure, and his sturdiness and strength were emphasized through an elevated Gpoint of view as he first appeared on the scene. Regarding his appearance, Lu was pictured wearing attire suitable for both military and official settings. His manner and demeanor were generally meek, submissive, and mournful when he was dressed in official attire in the bureaucracy. However, when he was in armor as a military leader, his look and posture were hard and stern (See Figure ) In keeping with the sound logic of human nature to survive in the ancient officialdom, the characters’ appearances were molded by the circumstances and experiences they encountered. Lu had both a courageous and a vulnerable aspect to his personality. On the battlefield, he displayed courage and fearlessness. However, amid the lack of support he received from the emperor and his peers, his humiliation and sadness shined through. In the story, Emperor Chongzhen was not fully committed to fighting off the Qing army with all of his strength. Hence, even though he bestowed military authority upon Lu, Lu was not adequately resourced for battle. Lu battled without assistance until the end, accomplishing his mission as a “loyal subject” (zhong chen 忠臣) by doing what was expected of him by his country and monarch.

Figure 4. (a)li Zicheng, Volume 1: Invasion of Qing troops (Citation1978), Plate 21. (b)Li Zicheng, Volume 1: Invasion of Qing troops (Citation1978), Plate 38. Reproduced with the permission of Shanghai People’s Fine Arts publishing house.

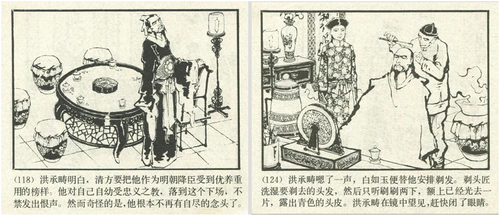

After the death of Lu Xiangsheng, the emperor dispatched Hong Chengchou to the frontier to continue resisting the Qing army. Hong Chengchou was concerned about the lack of effective support before the war started, and the battle that ensued confirmed his suspicions. The Ming army, led by Hong Chengchou, was beaten by the Qing army in Liaodong. Then, the Ming army was trapped in Songshan Fort by the Qing army. In February of the following year, the Ming traitors and the Qing army collaborated to breach the fort, defeating all of Hong Chengchou’s troops and capturing him. Hong Chengchou’s only option to maintain his status as a loyal subject after his capture was to “die for keeping chastity,” but his wish to live caused him to hesitate. The Qing emperor Hong Taiji was determined to conquer China and needed Han Chinese culture and talents severely. Thus, he was bent on persuading Hong Chengchou to surrender. Volume 22 devoted over 50 pages portraying Hong’s internal struggle, visually showing his journey from rejection to acceptance, from wearing Han Chinese costumes to wearing Manchurian clothes (See Figure ) The eventual surrender of Hong was marked by his shaving off his hair in the style of the Qing and his acceptance of a position as an official in the new regime. Emperor Chongzhen was heartbroken by Hong’s defeat, but he evidently assumed, or hoped, that Hong had died. Before the emperor confirmed whether Hong had been slain in battle, he had decided to honor him for his faithfulness by organizing a grand funeral ceremony for him. Eventually, when news of Hong Chengchou’s surrender reached Beijing, the Emperor had to call off the funeral with embarrassment and urgency.

Figure 5. (a) Li Zicheng, Volume 22: Hong Chengchou Surrenders to the Qing (1983), Plate 118. (b) Li Zicheng, Volume 22: Hong Chengchou Surrenders to the Qing (Citation1983),Plate 124. Reproduced with the permission of Shanghai People’s Fine Arts publishing house.

The majority of Yang Sichang’s storylines involved the repression of the peasant uprising despite the fact that he was not an essential supporting character over the entirety of the series and was not even the main character in any of the volumes. Yang’s role as a “reactionary force” within the class narrative of the binary conflict between revolution and counter-revolution served to underline the greatness of the revolutionary forces on the other side. However, Yang Sichang was not portrayed as an oppressor of the peasant army. Rather, the comic displayed his military and political skill in numerous occasions. Yang’s primary concern came from the emperor, not the peasant army. During the Ming Dynasty’s war with the peasant army, Emperor Chongzhen regarded Yang Sichang as his last hope. When the Ming army began to lose territory, the emperor dispatched Yang Sichang to Hubei Province to stop the tide. Yang’s troops were unable to retain the crucial city of Xiangyang despite his best efforts due to corruption and a lack of supplies. In volume 17 of the comic, his fear of the emperor’s punishment eventually overwhelmed him, and he committed suicide by taking poison, as illustrated in a great number of shadow and light-shifting personal portraiture (See Figure ).

Figure 6. Li Zicheng, Volume 17: The Capture of Xiangyang (Citation1982), Plate 130. Reproduced with the permission of Shanghai People’s Fine Arts publishing house.

6. Alternative explanation

Based on the examination of the visual portrayal of the characters presented above, the four prominent “atypical” characters lend a classical tinge to the plot. The spiritual content of heroism in classical Chinese literature centers primarily on the personal cultivation of loyalty to the ruler, courage in battle, adherence to morality, honesty and trustworthiness, and other aspects influenced by Confucianism’s ideology of “loyalty and filial piety” (zhongxiao 忠孝).This concept emphasizes the importance of honoring and respecting elders, parents and rulers. Dramatic depictions of Confucianism in classical Chinese literature often reflect the social norms and values of ancient China, such as the Romance of the Three Kingdoms and the Water Margin. These works often present Confucianism as a central aspect of Chinese culture and society, with the conflict between characters reflecting the tension between Confucian values and social reality.

The most difficult interpersonal relationship that Lu Xiansheng, Hong Chengchou and Yang Sichang face in their respective episodes is the Confucian tradition of the relationship between ruler and subject, especially Lu. Given the imperial court’s and the emperor’s incompetence, Lu met his tragic end. Although he was an innocent victim, he embodied the traditional philosophy of “righteousness” (yi 义), which refers to the obligation to the state and community, in his dedication to fight against the Qing Dynasty. This concept is what Confucianism calls the spirit of “knowing the impossibilities but persevering”(zhiqi bukewei er weizhi 知其不可为而为之).Footnote31 It is fair to say that he represents the culture of loyalty and sainthood that the vast majority of traditional Chinese monarchs, scholars and military leaders have revered. In contrast, Hong Chengchou’s surrender was a violation of loyalty, a moral humiliation, and a betrayal of the Han-centered “orthodox” dynasty, thus making him the infamous “Race Traitor,” a phrase that normally translates to traitor but refers to an outside collaborator.

On the other hand, in the relationship between ruler and subject, the filial obedience of the subjects presupposes that the ruler must also have a benevolent, loving, wise and just character; the monarch must be a model for the subjects to follow and must not lose his virtue. From this perspective, Emperor Chongzhen in the story does not conform to the two-way moral requirements of Confucianism in the relationship between ruler and subject. He makes many difficult demands of these subordinates (militarily and politically), yet does not trust them enough. Thus, Hong Chengchou’s betrayal and Yang Xichang’s suicide are more like a form of dissatisfaction and resistance to Chongzhen as an incompetent monarch.

The death of Huimei is the most pathos-filled and moving elements of the series’ ending. Her tragedy is also partly the result of the torture of Confucian moral codes. The themes of loyalty and filial piety are portrayed not only through the relationship between rulers and subjects, but also between parents and children. A famous example is the story of “The Three Obediences and Four Virtues”, which outlines the code of conduct for virtuous women in ancient China. The virtues include obedience to her father before marriage, obedience to her husband after marriage, obedience to her son in widowhood, and loyalty to her mother-in-law.

In Confucian ethics, a daughter/son is obliged to obey her/his father’s orders as part of their duties and responsibilities in family relationships. With parenthood, Li Zicheng could decide on Huimei’s marriage, and when Huimei disobeyed the arranged marriage and sobbed and pleaded against it, Li began to utilize ethical and moral demands to force her to obey. In addition to the father-daughter relationship, Li Zicheng and Huimei had a ruler-ruled relationship. Confucius linked filial piety with loyalty to the ruler in The Analects of Confucius, where he stressed that those who are filial to their father must also be loyal to the ruler.Footnote32 Under this double moral constraint, Huimei was unable to revolt against Li Zicheng’s role as “ruler-father.”

In summary, the tragedy of these characters is not the result of class conflict in a revolutionary context, but the victim of a conflict between Confucian ideals and reality. Hence, the visual emphasis of this work does not reflect the modern revolutionary ideology of historical materialism that was hoped for in the era of the original novel, but rather the influence of Confucianism on Chinese culture and society. Meanwhile, the theme of the story is replaced from highlighting peasant wars and glorifying peasant heroes to a conflict of characters centered on Confucianism, such as loyalty and filial piety. The moral standards of the rulers (Emperor Chongzhen, Li Zicheng) are unable to cope with the moral standards of their subjects, and the conflict shown here only demonstrates the unworthy morality of the feudal rulers rather than the justice and legitimacy of the victory for the proletariat over the exploiting classes.

7. Conclusion

The Li Zicheng series represents the complexity of a socialist state in post-revolutionary transition. The textual arrangement and the portrayal of characters of a pre-modern story may serve as a case study of the fraught struggle of the post-revolutionary cultural turn in an era in which class struggle theory and historical materialism are challenged and questioned.Footnote33 The narrative structure of the Li Zicheng series is typical of the kind of “big events” (subject matter determinism), “heroic ode,” “three prominences,” and “epicness” (an attempt to point out to the reader what the patterns of social and historical development are) that characterized the literature and art of the first 30 years of the People’s Republic of China. Nevertheless, the visual prominence of “atypical” characters within the framework of a revolutionary narrative detracts from the revolutionary themes underlying the story.

To put it differently, in terms of visually constructed character conflicts, this comic presents an unstable revolutionary position, with ethical and moral dilemmas stronger than the logic of the revolutionary narrative. The detailed description of the “reactionary class,” such as Lu Xiangsheng, Hong Chengchou, and Yang Sichang (even visually representing their positivity), dissolves the revolutionary logic of the dichotomy between the “new” and the “old” and departs from the revolutionary literature practices of the 1950s-1970s (praising the positive and exposing the negative), as well as from the logic of social evolution represented by Marxism. Moreover, the peasant uprisings represented by Li Zicheng were rebelling against class oppression. However, Huimei’s tragedy diminishes the image of Li as the ideal revolutionist. None of these four characters are protagonists in terms of the structure of class oppression/counter-oppression. Their fates are all shaped by the will of the rulers and the structure of society. Their story does not lie in the midst of a strong class confrontation but in the relationship between superiors and subordinates. This moral code and principles more closely resemble the classical style of role conflict.

In conclusion, the political philosophy reflected in this comic differs from that of the preceding age, breaking away from absolutist classism while retaining a certain moral conservatism and no longer emphasizing class hatred for ideological purification. Although post-Mao China has undergone some transformation, the socialist path has not been completely negated as it was in the Eastern Bloc or Soviet Union. It has survived in some form, just as the Li Zicheng series retains the framework of the proletarian revolution. In the 1980s, Chinese literature and art creation, such as political transition, moved toward a kind of eclecticism that was seemingly gradually disentangled from the shackles of Maoist and Leninist ideology while not fundamentally denying them. The creators of this Lianhuanhua series have grown distant from the “political theme,” which is reflected in the visual emphasis. This series inconspicuously stripped away the communist trappings of an ancient Chinese epic and accomplished a discourse reconstruction within the Chinese context in the form of popular culture. As mentioned earlier, the creators of the comic series did this adaptation before the original novel received negative reviews, implicitly de-revolutionizing the revolutionary narrative. This is an early indication of the transformative nature of Chinese society and culture in the 1980s. In fact, such society and cultural reconstruction utilized a portion of the pre-modern social and moral complex to disperse part of the grand narrative of revolution that attempted to unveil the laws of history.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yuxiang Yang

Yuxiang Yang is currently a Ph.D. student majoring in Visual Arts at the Faculty of Creative Arts, Universiti Malaya in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. His research interests include popular culture and comic art. His current research project is a visual study of a local Chinese comic book genre, Lianhuanhua. This project is devoted to providing innovative ideas for understanding the relationship between culture and politics in socialist China. Email: [email protected]

Simon Soon is Senior Lecturer in art history at the Visual Art Studies Program, Faculty of Creative Arts, Universiti Malaya. He has written on various topics related to 20th-century art across Asia and curates exhibitions, most recently Bayangnya Itu Timbul Tenggelam: Photographic Cultures in Malaysia. He is also a team member of the Malaysia Design Archive, an independent digital archive on visual culture. He is occasionally an artist, working chiefly through collaboration to explore cultural histories of the Malay Archipelago.

Simon Soon

Simon Soon is Senior Lecturer in art history at the Visual Art Studies Program, Faculty of Creative Arts, Universiti Malaya. He has written on various topics related to 20th-century art across Asia and curates exhibitions, most recently Bayangnya Itu Timbul Tenggelam: Photographic Cultures in Malaysia. He is also a team member of the Malaysia Design Archive, an independent digital archive on visual culture. He is occasionally an artist, working chiefly through collaboration to explore cultural histories of the Malay Archipelago.

Notes

1. Lianhuanhua is an indigenous Chinese comic book genre that refers to visual reading materials, including illustrated storybooks and comic literature. In 20th-century China, a country with low literacy and low purchasing power, Lianhuanhua was richly illustrated, inexpensive, and had a wide cross-age readership.

2. The top three were: The Romance of the Three Kingdoms (60 volumes), Chronicles of the Eastern Zhou Kingdoms (50 volumes), and The Sui and Tang Dynasties (44 volumes).

3. John A. Lent, Asian comics (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2015), 34.

4. Zedong Mao, “Report on an investigation of the peasant movement in Hunan” in Selected Works of Mao Tse-Tung. Volume 1, (Oxford: Pergamon Press,1965), 28.

5. For example, to highlight the greatness of the peasant revolutions, Lianhuanhua, like other literary forms, have made new assessments of the peasant uprisings in Chinese history, thus elevating them into the driving power of history. In this atmosphere, the military actions of many ancient peasant rebellions rose to the level of justice. For details see Wei Jin, Xinzhongguo xuanjiaolei lianhuanhua yanjiu (1949–1979) [Research on the types of publicity and education Lianhuanhua of new China from 1949 to 1979] (Liaoning University, 2016), 44.

6. Jinhua Dai, Yinxing shuxie 90 niandai zhongguo wenhua yanjiu [Invisible Writing—A Study of Chinese Culture in the 1990s] (Nanjing: Jiangsu People’s Publisher, 1999), 44.

7. This was the propaganda strategy of the Maoist era, emphasizing the victor of the revolution in political discourse. See specifically in Peter Hays Gries, China’s new nationalism: Pride, politics, and diplomacy (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 69–74.

8. Three famous novels tell the story of Li Zicheng’s uprising in the late Ming and Qing dynasties, namely, The new popular novel of the fight against the Chuang (新编剿闯通俗小说), The strange story of the Ding Ding (定鼎奇闻), and Qiao’s popular romance of the history (樵史通俗演义)..

9. Zicheng Hong, Zhongguo dangdai wenxueshi [A History of Contemporary Chinese Literature] (Beijing: Peking University Press, 2007), 94.

10. To construct the legitimacy of the Chinese communist revolution, which constituted the most direct and primary source of historical conceptions for generations of Chinese historians, Marxism was the “supreme directive” that long influenced Chinese historiography. Almost all of the debates that have taken place in mainland historiography over the decades have had a direct or indirect link to the materialist conception of history. See Zedong Mao, “The Chinese Revolution and the Chinese Communist Party” in Selected Works of Mao Zedong, vol. 2 (People’s Publishing House, 1991), 622–625.

11. In 1942, Mao Zedong’s “Talks at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art” was published, formally establishing the guidelines of “literature and art for the workers, peasants, and soldiers” and “literature and art as subordinate and subservient to politics.” This publication not only set the fundamental direction of literature in the liberated areas but also made it the only correct direction for literature and art in the new China. In other words, for a long time, being completely influenced by the political situation and having to have a certain way of political discourse became almost the only choice for contemporary Chinese literature. See Mao Zedong, “Zai yanan wenyizuotanhui shang de jianghua,” [Talks at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art] in Mao ze dong xuan ji di san juan [Selected works of Mao Zedong (3)] (Beijing: Renmin chubanshe, 1991; Original work published 1942).

12. Jingmin Wei, “Maozedong yu yaoxueyin de lizicheng” [Mao Zedong and Yao Xueyin’s “Li Zicheng”] Journal of Party History 11, no. 2 (May 2003): 36.

13. Haogang Yan, “‘Li Zicheng’ de jingdianhua, qu jingdianhua yu zai jingdianhua” [The Classicization, De-classicization and Re-classicization of “Li Zicheng”], New Literary Review, no. 3 (2021): 101–107.

14. Zaifu Liu, “Liu Zaifu on Literary Research and Literary Debates,” Wenhui Monthly 9, no. 2 (1988.

15. As early as 1980, a domestic scholarly article questioned the dynamics of peasant revolts, see Kwang-Ching Liu, “World View and Peasant Rebellion: Reflections on Post-Mao Historiography,” The Journal of Asian Studies, No.2(Feb 1981): 259–291.

16. Hong, A History of Contemporary Chinese Literature, 93.

17. Yu Bai, Lianhuanhuaxue gailun [An Introduction to Lianhuanhua Scholarship] (Jinan: Shandong art publisher, 1997), 104.

18. Barker Martin, Comics: Ideology, Power and the Critics, (Manchester University Press, 1989), 270–75.

19. Early communist regimes saw popular culture such as Lianhuanhua as ideal for mass mobilization. See Yaochang Pan, “Fuzhi, yinshua he dazhong chuanbo—Muke he nianhua, lianhuanhua, xuanchuanhua quansheng de shidai” [Copying, Publishing and Mass Communication—On the Peak Period of Woodcut and Poster] Journal of Shanghai University (Social Sciences) 13, no. 5 (September 2006): 130–134.

20. Lihong Mai, Tushuo Zhongguo lianhuanhua [Graphical interpretation of China Lianhuanhua] (Guangzhou: Lingnan fine arts publishing House, 2006), 17.

21. Bai, An Introduction to Lianhuanhua Scholarship, 129.

22. The translation of 绣像 and 全图 may not be authentic, I have translated it directly according to their Chinese meaning.

23. Published in the year Hongzhi of the Ming dynasty (1498), The Complete Illustrations of the Western Chamber 明刊西厢记全图 was already highly illustrated, with 273 illustrations.

24. Clare Painter, J. R. Martin, and Len Unsworth, Reading visual narratives: Image analysis of children’s picture books (John Benjamins Publishing 2013), 45.

25. Painter, Reading visual narratives, 59.

26. Although these political-aesthetic principles were formally proposed in 1968, their ideological roots can be traced back to the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art in 1942, and they existed for many years as a guiding ideology for literary and artistic creation.

27. Xiuqin Li, “Dianxing renwu” (Typical characters), in Nan Fan, ed., Ershishiji Zhongguo wenxue piping 99 ge ci [99 Key words in twentieth-century Chinese literary criticism] (Hangzhou: Zhejiang wenyi chubanshe, 2003), 256–60.

28. Painter, Reading visual narratives, 64.

29. The demands of the Mao era on the class origins and moral qualities of prominent characters were prioritized by the embodiment of proletarian ideology.

30. Before Yao Xueyin’s novel, no record on Huimei had been found in either authentic history or folk history.

31. From The Analects of Confucius, Chapter Xianwen 宪问. The main content is a commentary by Confucius on various phenomena in society at the time and a discussion of certain virtues required of a gentleman.

32. From The Analects of Confucius, Chapter Xueer 学而.

33. Kwang-Ching Liu. “World View and Peasant Rebellion: Reflections on Post-Mao Historiography” The Journal of Asian Studies, No. 2 (Feb 1981): 259–291.

References

- Bai, Y. (1997). Lianhuanhuaxue gailun [An Introduction to Lianhuanhua Scholarship]. Shandong art pubilisher.

- Cui, J. (1983). Lizicheng zhi ershier: Hongchenchou xiang qing [Li Zicheng, Volume 22: Hong Chengchou Surrenders to the Qing]. Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Publishing House.

- Cui, J. (1987). Lizicheng zhi ershiqi: Huimei zhisi [Li Zicheng, Volume 27: The Death of Huimei]. Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Publishing House.

- Dai, J. (1999). Yinxing shuxie: 90 niandai zhongguowenhua yanjiu [Invisible Writing - a Study of Chinese Culture in the 1990s]. Jiangsu People’s Publisher.

- Fang, Y. (1982). Lizicheng zhi shiqi: Po xiangyang [Li Zicheng, Volume 17: The Capture of Xiangyang]. Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Publishing House.

- Gries, P. H. (2004). China’s new nationalism: Pride, politics, and diplomacy. University of California Press.

- Hong, Z. (2007). Zhongguo dangdai wenxueshi [A History of Contemporary Chinese Literature]. Peking University Press.

- Jin, W. (2016). Xinzhongguo xuanjiaolei lianhuanhua yanjiu (1949-1979) [Research on the types of publicity and education Lianhuanhua of new China from 1949 to 1979]. Liaoning University.

- Liu, K.C. (1981, Feb). World view and peasant rebellion: reflections on post-mao historiography. The Journal of Asian Studies, 2(2), 259–16. https://doi.org/10.2307/2054866

- Liu, Z. (1988). Liu Zaifu on Literary Research and Literary Debates. Wenhui Monthly 9(2).

- Mai, L. (2006). Tushuo Zhongguo lianhuanhua [Graphical interpretation of China Lianhuanhua]. Lingnan fine arts publishing House.

- Mao, Z. (1991). “Zai yanan wenyi zuotanhui shang de jianghua,” [Talks at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art] in Mao ze dong xuan ji di san juan [Selected works of Mao Zedong (3)]. Original work published 1942. Renmin chubanshe.

- Painter, C., Martin, J. R., & Unsworth, L. (2013). Reading visual narratives: Image analysis of children’s picture books. John Benjamins Publishing.

- Shi, D., Luo, X., & Wang, Y. (1978). Lizicheng zhiyi: Qingbingrusai [Li Zicheng, Volume 1: Invasion of Qing troops]. Shanghai People’s Fine Arts Publishing House.

- Wei, J. (2003). “Maozedong yu yaoxueyin de lizicheng” [Mao Zedong and Yao Xueyin’s “Li Zicheng”]. Journal of Party History, 11(2), 36.

- Yan, H. (2021). Li Zicheng de jingdianhua qu jingdianhua yu zai jingdianhua” [The Classicization, De-classicization and Re-classicization of Li Zicheng]Li Zicheng de jingdianhua qu jingdianhua yu zai jingdianhua” [The Classicization, De-classicization and Re-classicization of Li Zicheng]Li Zicheng de jingdianhua qu jingdianhua yu zai jingdianhua” [The Classicization, De-classicization and Re-classicization of Li Zicheng]. New Literary Review, 10(3), 101–107.

- Yao, X. “Guanyu maozhuxi duiwo xie lizicheng de guanhuai he zhichi ji qita” [On Chairman Mao’s Care and Support for My Writing of Li Zicheng and Beyond]. Journal of Huazhong Normal University, 1(June 1994), 18–21.