Abstract

This article discusses the composer’s contribution to the vocal characterisation of the dramatis personae in contemporary opera. The composer can formulate the musical and expressive content of the soloists’ vocal parts to create a distinctive musical identity for each character. Throughout the course of the drama, the characters’ changing attitudes, emotions and moods are expressed through transformed constructions of their vocal parts, and the meanings are mediated to the audience largely through the combined effect of the various components in their vocal characterisation. By observing the vocal characterisation, as indicated by the composer in the score, vocal parts must thus be approached as compound analytical objects, in which various dimensions combine to create the appropriate musical and dramatic effect. This article describes the vocal characterisation of the dramatis personae in Paavo Heininen’s opera Silkkirumpu (The Damask Drum) op. 45 (1981-1983) and in Kaija Saariaho’s Adriana Mater (2005). Heininen’s The Autumns (1970) for mixed choir and Reality (1978) for soprano and instrumental ensemble are introduced as pre-works of Silkkirumpu. The examination of vocal writing in these pieces thus extends the discussion to vocal music other than opera. Following a brief description of the concept of vocal characterisation in general and an introduction of the analytical approach, the text focuses on musical examples. In conclusion, it is suggested that the analytical approach could be extended to include the unique aspects of vocal performances.

1. Introduction

The human voice is widely understood as an expression of identity. Cavarero (Citation2005) describes the voice as a constituent part of identity in that it identifies a person just as the fingerprint does: its physical characteristics are inseparable from the body that produces it and the individual to whom it belongs. In vocal music, human identity manifests through the vocal part: in a song the vocal characterisation expresses the thoughts and attitudes of the poetic Self, and in an operatic context it identifies the dramatis personae. From the perspective of identity, vocal performance is a complex phenomenon. Even if the vocal soloist expresses the emotions and thoughts of a fictional character, through their bodily presence they also maintain their real-life voiceprint identity.Footnote1 The performer thus creates their individual interpretation through their personality, but the composer, however, has already framed the interpretation by characterising each of the dramatis personae musically in the score. This article brings the composer’s contribution to the forefront, first discussing the issue in general and, thereafter, examining how Paavo Heininen in his opera Silkkirumpu (The Damask Drum, Citation1981-1983) and Kaija Saariaho in her opera Adriana Mater (Citation2005) constructed the musical content and expression of the vocal parts in order to identify the fictional characters and to mediate the meanings of the text to the listeners. The text thus focuses on the contemporary operatic context, yet the discussion extends to vocal music in general.

The musical portrayal of an operatic character constitutes specific, combined features in the vocal part, realised within the limits of a certain voice category and its properties. Even subtle changes in these features may reflect changes in the characters’ moods or mental states throughout the course of the drama and may show their reactions to or attitudes towards ongoing events. Despite mutual understanding of the phenomenon—a practice that has been tacitly acknowledged among composers—analysts have seldom approached the vocal part as a compound object in which various aspects combine to create a characteristic vocal expression. Thorough examination of the components of the vocal lines yields exact and versatile information about how the structures and meanings of the text are reflected in the contents of the vocal parts. Any comprehensive study of an opera requires examination of the orchestral actions and the interaction between the vocal and instrumental parts, given that the orchestra also characterises the dramatis personae and takes part in the operatic narration. However, a close reading of the vocal parts might reveal significant aspects that are used as dramatic devices, and that may otherwise pass unnoticed.

Scholars observing the operatic parts tend to pay attention to thematic ideas or Leitmotives that could be linked with certain characters, describing how these motives are transformed throughout the course of the drama. The focus of analysis is often on the primary parameters, such that secondary parameters, nuanced vocal expression and types of vocal production might be ignored.Footnote2 However, the effect that the primary and secondary parameters create together may well be very significant for the composer. Some vocal scores in the twentieth-century repertoire indicate each parameter precisely. The vocal parts thus need to be approached as compound analytical objects, paying attention even to subtle changes in musical content and expression.

Let us consider how Rebekka Leydon (Citation2013, 314–317) discusses the soloist’s part in Salvatore Sciarrino’s vocal piece Infinito Nero. Having divided the piece into formal sections that are distinguished by the characteristic features in the vocal part, she describes her findings as follows:

If we consider the form as projected by the vocal part, the piece falls into four segments. … Here and elsewhere, a composite vocal timbre … the torrent of vocal sounds … This mode of declamation continues until m. 105, where, at the word, ‘profundava’, the voice drops in register … several outbursts unfold in the range of F3–G3 … the singer switches to a third mode of declamation, producing long, sustained notes … different modes of vocal delivery reflect different aspects of the text. (author’s italics)

Leydon thus defines various modes of declamation according to their pitch and intervallic content, register and linearity, yet she also comments on the expression. She does not mention the type of vocal production, probably because the soloist in Sciarrino’s piece performs most of her part singing. However, various speech-like types of vocal production and extended vocal techniques may be significant in terms of expressing the meanings of the text in other pieces.

It is clear from the citation that Leydon’s interpretation is based on a comprehensive examination of various aspects of the vocal part. There is thus a need for a practical analytical tool that gathers all parameters together to facilitate their observation in parallel and recognition of their compound effect. For such a purpose I outline a model of vocal characterisation. Vocal characterisation refers to various dimensions in the parts of operatic characters that together create the appropriate musical and dramatic effect and give musical expression to their personalities, their reactions to the dramatic events as well as their various moods and emotions.

In the following pages I first introduce the concept of vocal characterisation and clarify how it could be applied in a contemporary operatic context, in particular. Thereafter, I analyse musical examples from Paavo Heininen’s and Kaija Saariaho’s oeuvres. Professor Heininen (1938–2022) taught composition to a generation of Finnish composers, among them Kaija Saariaho (1952–2023), Magnus Lindberg (1958), Jouni Kaipainen (1956–2015) and Veli-Matti Puumala (Citation1965). The text focuses on Heininen’s post-serial opera Silkkirumpu (The Damask Drum, 1984), in which the musical characterisation of the dramatis personae is a focal dramatic device, and the expressive qualities as well as vocal qualities—meaning the types of vocal production—are significant components of the vocal characterisation. I take up Heininen’s earlier vocal pieces The Autumns (1970) and Reality (1978) because they are considered pre-works of Silkkirumpu (Kaipainen, Citation1989). The reader may thus compare Heininen’s practices in these works, and also see how the model of vocal characterisation is extended to vocal works other than opera. I discuss the vocal characterisation in Kaija Saariaho’s Adriana Mater (Citation2005) in relation to Heininen’s practice. In conclusion, I suggest extending my analytical approach to performance studies.

2. Vocal characterisation

One of the main functions of operatic narrative concerns the musical portrayals of the dramatic agents. First of all, a suitable voice category is chosen to embody a certain character in the drama. While constructing the vocal parts, the composer needs to have a thorough understanding of voice categories, vocal abilities and the specific properties of voice types. The text below discusses these issues briefly and, thereafter, moves on to describe how the composer may formulate the vocal parts in order to characterise each of the dramatis personae.

According to Nair (Citation2007), the rough voice categories (soprano, mezzo, alto, tenor, baritone and bass) are further divided into specific subtypes, such as leggiero, lyric, spinto or dramatic tenors, with their distinctive characteristics. The specific voice type—in German, Fach – is a personal combination of components that largely depend on genetic and anatomical attributes, yet also on the development of the voice. Voice category is primarily associated with vocal range and tessitura, but it is also connected to vocal weight, vocal colour, flexibility as well as the rate and extent of vibrato: Wagnerian weight is not suitable for intimate miniatures, and coloratura’s fast, tight vibrato does not fit with classic lyric arias (Nair, Citation2007; 633–647). According to Steane (Citation1992, pp. 18,65), Mitchells (Citation1970–1971, 47–58) and Nair (Citation2007, 643–644), the properties of the voice type may be associated with the operatic character’s personality. Thus, lyric sopranos are often given roles as young girls or females expressing innocence (such as Pamina in Mozart’s Zauberflöte and Mimi in Puccini’s La Bohème), whereas dramatic sopranos represent more heroic or tragic characters (such as Leonore in Beethoven’s Fidelio and Salome in Strauss’s Salome).

Similar ideas are presented in Handbuch der Oper, which gives a comprehensive presentation on German Fächer (Kloiber et al., Citation2016). In principle, Fächer are devided into lyric, intermediate and heroic voice types (Lyrische Fach, Zwischenfach and Heldenfach). The authors make clear their understanding that certain physical properties of Fach, along with defining the practical vocal range, effect both the soloist’s characteristic vocal expression and their acting and thus limit the types of operatic roles they can successfully perform. Light and flexible voice types (such as Lyrischer Koloratursopran, Spieltenor and Characterbaß) can easily play comic roles, whereas heavier, dramatic voices (such as dramatische Alt, Heldentenor and seriöser Baß) are more suitable for music dramas. Leaning on the properties of Fächer, the authors suggest castings for a large number of baroque and classic-romantic operas, but their list includes twentieth-century stage works as well. As an example, in casting Kaija Saariaho’s opera L’amoir de loin, the role of Pilger should be given to a dramatic mezzo soprano (dramatischer Mezzosopran), and Jaufré Rudel should be performed by a heroic baritone (Heldenbariton) (Kloiber, Konold and Mitschka Kloiber et al., Citation2016, 925–940).

The aesthetic ideals of singing have changed along the centuries-long history of western opera. Some of the principles established in the golden years of Italian bel canto, such as vowelisation, perfect legato throughout the range as well as agile and flexible vocal delivery, are still maintained, particularly among singers performing the oeuvre of Donizetti, Bellini, Rossini and their contemporaries (Jander, Citation2001; Mason, Citation2000, 204–220; Rosselli, Citation2000a, 83–95; Stark, Citation1999). In the nineteenth century, the significant change in singing ideals was caused partly by the romantic aesthetics, but also by practicality; the chief opera houses’ auditoriums were large, and their full orchestras included large brass sections and altogether eighty or even a hundred players. For the soloist, working in such conditions requires a weightier, more powerful voice and a tone quality with constant resonance that carries over the orchestra and projects to large audiences (Rosselli, Citation2000b, 96–108). As extreme examples of the repertoire one could mention Wagner’s operatic roles that are demanding with regard to both singing and acting.

As for the twentieth century, Arnold Schönberg’s pioneering melodrama Pierrot Lunaire (1911) served as an important model for subsequent composers: it opened a path to a completely new kind of vocal writing, which includes frequent use of extreme registers and ultimate expression, as well as experiments with extended vocal techniques, such as Sprechstimme and other speech-like types of voice production (Hirst & David, Citation2000, p. 197; Wishart, Citation1980). In such contemporary works the extended vocal means, together with complex rhythmic and harmonic constructions, makes special demands for the soloist both musically and technically: some vocalists therefore make a choice to focus on the mainstream operatic repertoire. However, some others do indeed specialise in contemporary music, among them Jane Manning, Barbara Hannegan and Anu Komsi. Manning shared her extensive experience of contemporary repertoire in her books (Manning, Citation1986; Citation1998). She also premiered Heininen’s vocal work Reality. Hannegan has worked in co-operation with several contemporary composers, among them György Ligeti and Louis Andriessen. The Finnish soprano Anu Komsi is an experienced interpreter of Saariaho’s vocal works.

The composer may have a certain soloist in mind while constructing the vocal part: as an example, Peter Maxwell David composed his monodrama Eight Songs for a Mad King for baritone and actor Roy Hart, who premiered the work in 1969. Some composers stretch the operatic conventions and give roles to performers who are not classically trained. The role of the gipsy-woman Husso in Veli-Matti Puumala’s Anna-Liisa (2008) was given to Sanna Kurki-Suonio (ethno mezzosoprano) during the early phase of the opera project (Kurki-Suonio, Citation2009, p. 71). Kurki-Suonio expressed Husso’s character mainly through her extremely low tessitura together with her specific, rough type of voice production. However, her personal vocal production set limits on certain dimensions of her vocal part. Types of vocal production that are common in folk music have inspired Kaija Saariaho as well. Her latest opera Innocence (2018) includes a part written for ethno soprano Vilma Jää. Jää (Citation2021) is a specialist in old Finno-Ugric vocal techniques, yet she also composes and performs popular music.

In addition to paying attention to the voice category and its properties, the composer constructs the musical content and expression in the soloist’s part in such a way as to deepen the character’s portrayal: through their vocal lines, the characters musically reveal their personalities, their reactions to the dramatic events as well as their various moods and emotions. The dimensions of the vocal part appear united in the musical whole, and thus in combination create the appropriate musical and dramatic effect. The term vocal characterisation refers to the vocal part as a combination of its components representing various parameters of music.

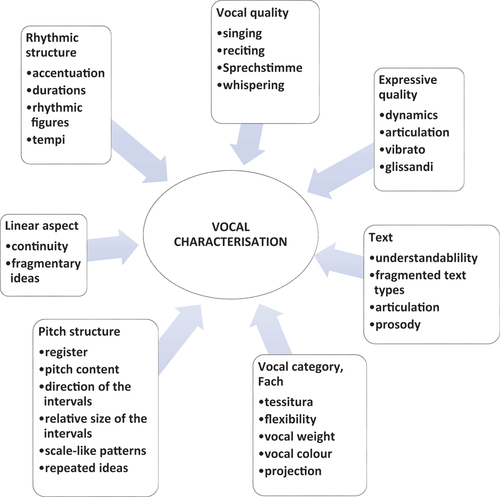

Figure is a model of vocal characterisation and its components. Just as the practice of constructing the vocal chracterisation varies among composers and their individual pieces, so do the aspects gathered into the model. My suggestion for the components and their categorisation is based on my examination of Heininen’s vocal works dating from the seventies and eighties; in particular, these aspects turned out to be relevant in Silkkirumpu. In addition, my categorisation follows Heininen’s grouping of parameters in his article, in which he clarifies his aesthetic ideals and compositional practice (Heininen, Citation1998, 56–62, 80–83). Significantly, my integrated approach to vocal parts comes close to Heininen’s view: he emphasises the compound effect of carefully controlled parameters in his music (Heininen Citation1998, 70–75).Footnote3

In defining the vocal characterisation I considered various aspects: 1) the voice categories and the properties of specific voice types; 2) the linear aspect of the melodies (continuity versus fragmentary ideas, for example); 3) pitch and the intervallic structure (such as register, pitch content, the direction and relative size of the intervals, scale-like patterns, repeated ideas and intervals, as well as focal pitches)Footnote4; 4) tempi and the rhythmic structure (including accentuation, durations and rhythmic figures); 5) expressive quality (such as dynamics and articulation); 6) vocal quality (such as singing, reciting and whispering), and; 7) aspects of the text (such as fragmented text types, articulation, prosody and understandability). The components of vocal characterisation overlap: continuity in the melodic lines depends in part on the intervallic structure, for example. The terms “vocal technique”, and “a type of vocal production” used in the scholarly literature come close to my term “vocal quality”.

Poetic text set to vocal lines reveals essential dramatic aspects. When I was observing Heininen’s compositions I freely applied Peter Stacey’s study on text types and their various manifestations in contemporary vocal pieces that represent the same time period (Stacey, Citation1987;Citation1989), specifically paying attention to fragmented text types, prosody and paralinguistic expressions. Fragmentation weakens the understandability of the text, and the sonic qualities of language momentarily dominate the expression. Despite this, the text never completely loses its connection to the semantic content: as Grant (Citation2001, p. 220) explains, the audience, in their listening experience, absorb the poetic components and build up meanings. From this viewpoint, text can be considered a component of vocal characterisation. However, even in close interaction, text and music in a vocal composition partly maintain their existence independent of each other and thus also have expressive potential of their own.Footnote5 Therefore, in my analytical process, I first observed both the text and the music separately, and then studied the relations between these elements.

Along with creating the musical portrayals of the dramatis personae by means referred above as vocal characterisation, the composer must also take into account the use of orchestral forces. In general, orchestral instruments play significant roles in operatic narrative: they create a suitable atmosphere for each scene, largely govern the temporality and often reveal important abstract themes (Magee, Citation2000, p. 191, 275; C. Morris, Citation2002). Furthermore, the interaction between the soloists and the orchestral instruments is an essential element in operatic storytelling. By creating a distinctive orchestral timbre to accompany each character, the composer can deepen their musical portrayals. As the drama unfolds, the orchestra empathically expresses the characters’ transforming emotions and extends their statements. From a purely technical point of view, the orchestral instruments often lightly support the soloists through difficult passages or in the extreme high register. Control over orchestral dynamics is essential: thorough knowledge of the human voice and the facilities of voice types helps the composer to orchestrate in such a way that the soloist is never overrun.Footnote6 The viewpoints above show that from the perspective of operatic characterisation the use of orchestra is by no means unimportant. However, within the limits of this article I focus on the above-mentioned dimensions of vocal characterisation and thorough examination of the vocal parts.Footnote7

Summing up, the model of vocal characterisation as an analytical tool is simply a mind map that helps the analyst to create an overview of the aspects and features perceived in the object. These aspects are categorised in various components and their subcategories. A useful first step in studying an opera is to construct an overview of the vocal means by observing all the vocal parts on a general level, and then to define the characteristic features in certain vocal parts and to recognise aspects of significance in relation to the dramatic content. Transformations in the character’s vocal characterisation often signal of changes in the dramatic content, and thus need thorough examination. Significant components may be collected into a table showing the precise moment of the change in each component from the perspectives of the music (the exact bar numbers) and the text (the event or emotion expressed). By way of clarification, I will now move on to examine the musical examples.

3. The pre-works of Silkkirumpu

To understand Heininen’s practice in constructing vocal parts in Silkkirumpu, let us first discuss two vocal pieces that have been referred to as Silkkirumpu’s pre-works: The Autumns (Heininen, Citation1970) for mixed choir and Reality (Heininen, Citation1978) for soprano and ten players. The idea of writing an opera came to Heininen’s mind in the early 1960s. He experimented with extended vocal techniques and avant-gardist text types during the 1970s. He was a serialist in the early phases of his career, and serialist ideals have remained with him (Heininen, Citation1989).Footnote8 He studied the iconic vocal compositions of the time period, such as Berio’s Sequenza III (1966), Boulez’s Pli selon pli (1960) and Zimmermann’s Die Soldaten (1965).

Heininen’s vocal practice in The Autumns comes close to that in Silkkirumpu. Furthermore, the text links the two works: whereas the Silkkirumpu libretto is based on a Japanese noh play, the text of The Autumns combines Japanese haiku with their English translations (Jaakkola, Citation2020, 7–8). Unlike opera libretti in which there are usually several characters, haiku, in principle, expresses the thoughts of a single poetic Self. However, although set to haiku, the music of The Autumns seems to manifest the presence of two speakers who act in turn or simultaneously. The Japanese and English texts proceed superimposed in the musical score of The Autumns, divided among the choral voices phrase by phrase. Each of the voices alternates constantly between the Japanese and the English texts, the beginning of the poetic line often being performed by one voice and continued by another. In terms of vocal characterisation, the individual choral voices are not distinctive in their construction. Instead, their characterisation is combined with the language: the musical structure of the passages set to the Japanese text clearly differs from those set to the English text (Figure ).

Figure 2. The Autumns, p. 41: the vocal characterisation of the poetic selves, one of them being English, the other Japanese. © Fennica Gehrman, Helsinki. Printed with the permission of the publisher.

As Table shows, the continuous, expressive melodies sung in English include large intervallic leaps connecting the registral extremes of the choral voice.Footnote9 The flowing rhythmic structure does not draw attention. The over-articulated phoneme L may originate in the English word “[autumn] leaves” that is heard at the beginning of the piece. The passages performed in Japanese seem to follow the sonic features of the language. The first syllable of Japanese words is regularly stressed, as are the beginnings of the musical units—either by accents or sforzando expressions. Musical units, limited in length and vocal range, consist mostly of repeated pitches on equally long, rapid note values, such as semiquavers or fifths of semiquaver quintuplets. Groups of five notes frequently appear in the rhythmic structure, as if resembling the syllabic structure of haiku – an invention that is further developed in the musical structure of Silkkirumpu (Jaakkola, Citation2020, 232–233, 277).

Table 1. The components of vocal characterisation in the Autumns, p. 41

In sum, the text of The Autumns is shared between two poetic voices, one of them being Japanese and the other one English, each speaking their own language. Likewise, two musical personas stand out in the musical construction of The Autumns, namely two virtual agents who, respectively, represent a certain poetic Self and perform their words through their distinctive vocal characterisations. In Figure (p. 41 in the printed score) the English-speaking musical persona appears first on the tenors, shifts to the choral altos and then, at poco piú mosso, expresses himself on the sopranos, the altos and the tenors. The musical personas must thus be separated from the real agents in the performance: as abstractions they are not connected with certain choral voices, but they constantly shift from one choral voice to another.Footnote10

Along with The Autumns, Reality op. 41 for soprano and ten playersFootnote11 sheds light on Heininen’s practice of constructing the vocal parts embarking on the opera project. The premier of Reality was in 1978, with soprano Jane Manning and The New Music Group of Scotland conducted by Edward Harper. Heininen started work on his opera Silkkirumpu three years later, composing it during the years 1981–1983.Footnote12 In general, his musical languages manifest virtuoso vocal technique and extreme vocal expression in both Reality and Silkkirumpu. Kaipainen (Citation1989) refers to Reality as a “concerto for soprano”, referring to its correspondences with Silkkirumpu, subtitled “a concerto for singers, players, words, images, movements”.

Reality consists of three songs, each in a different language, namely “Forse un mattino”, “Elle avait trouvé” and “When you are”. Each verse manifests a perspective on reality, which is scattered in time and space and filled with sudden, irrational events that threaten the integrated subjectivity of the poetic Self. Three accompanied phonetic etudes (“Etude I, II, and III”) and an instrumental cadenza (“Peripeteia”) are placed between the songs. Rather than giving a comprehensive analysis of Reality, in the following I focus on certain aspects of “Etude II” and “When you are” that have corresponding aspects in Silkkirumpu: the speech-like vocal qualities, inexact rhythmic and intervallic structures as well as the vocal pseudo-polyphony in both Reality and in Silkkirumpu become musical metaphors for the disintegrated Self.

Figure shows the interaction of the soloist and the violoncello in bb. 155–159 of “Etude II”. In terms of vocal characterisation, the soloist mostly whistles her lines, the whistling being notated with open diamond noteheads. Both the rhythmic structure and the pitch structure are precisely indicated; in places the melodic interval is performed glissando. The vocal line includes large intervallic leaps in the range of pitch interval 25. The soloist must control her voice carefully when she changes her vocal quality from whistling to singing and vice a versa. The vocal qualities of singing and whistling differ widely in terms of timbre and dynamic volume, so that in performance it is almost as if they are produced by two separate vocalists. The constant alternation between the vocal qualities could also be a musical metaphor for the disintegrated Self. Given the violoncello’s part, she plays arco ordinari and flagioletti in turn, and her part also includes glissandi. The soprano and the violoncello perform a dialogue, which sets a timbral resemblance between specific vocal quality and specific instrumental technique. The soprano’s whistling corresponds with the violoncello’s flagioletti and her singing corresponds with arco ordinari. The glissandi of the soprano appear similarly to those of the violoncello: it becomes clear that the performers are like characters in a drama, listening to and commenting on each other’s statements.

Figure 3. Reality, “Etude II”, bb. 155–159: the soprano and the violoncello parts. © Fennica Gehrman, Helsinki. Printed with the permission of the publisher.

The third song in Reality is entitled “When you are”, and it depicts an experience in which accidental, irrational events and horrifying news blend with events in daily life, blur people’s sense of reality and create delusive, imagined visions. Anaïs Nin’s poem ends as follows: “you read about the man who was cut into pieces, and in front of you now stops the half-body of a man resting on a flat cart with small wheels.” Figure shows the soprano and the violin parts in bb. 364–368. The soprano’s pseudo-polyphonic vocal part in bb. 366–368 consists of two contrapuntal voices with distinctive musical components (Table ). The low, repetitive murmuring of Voice 2 frequently interrupts Voice 1, the “cantus firmus”, which would otherwise create a linear melodic entity realising the original poetic text. Voice 1 is clearly separated from Voice 2 by the registral distance and the different vocal quality. The ensemble also joins in supporting the emphatic, sustained notes of Voice 1 that are sung in the upper and middle registers. The frequent alternation between Voice 1 and Voice 2 in this passage breaks the continuity of the soprano’s lines. Her fragmentary vocal characterisation thus figuratively depicts the poetic content: the surreal vision of a man cut into pieces. Interpreted in a larger context, it becomes a musical metaphor for the disintegrated subjectivity struggling in the scattered, chaotic reality.

Figure 4. Reality, “When you are”, bb. 364–368: the soprano and the violin parts. © Fennica Gehrman, Helsinki. Printed with the permission of the publisher.

Table 2. Reality, “When you are”, bb. 364–368: the distinctive features of the pseudo-polyphonic voices

Heininen further developed his practice of vocal pseudo-polyphony in Silkkirumpu: the pseudo-polyphony in opera’s mad scene “La Follia I e cadenza”, which I discuss later on, depicts the character’s split mind. Furthermore, the overall form of the opera’s other mad scene is based on a musical montage, in which the frequent alternation of the soloist’s two contrasting vocal materials becomes a musical metaphor for her fluctuating states of consciousness. Heininen’s idea is not unique: other twentieth-century composers also use alternation of two contrasting materials and frequent shifts between extreme registers to express the disintegrated Self (see Everett, Citation2009, 39–42).

Figure shows an excerpt from “Etude III”, which from the soloist’s viewpoint is the expressive climax of Reality. The text is largely phonetic, but the expressions “man who was cut into pieces” and “half-body man” originating in “When you are” appear fragmented in b. 438 and b. 441. As for the musical content, the soprano’s vocal part comes close to that of a virtuoso cadenza with all imaginable extended vocal techniques—although an additional ad lib. solo cadenza is an indicated option (b. 448). The rhythm is notated in conventional time signatures, but a regular pulse is avoided. Frequent slurs and rests, together with various polyrhythms, make the rhythmic structure unpredictable. Likewise, constant intervallic leaps between the extreme registers create a capricious impression in the melodic units. The majority of the melodic intervals in the passage are larger than pitch interval 9 (often performed glissandi), the extreme case being a leap of pitch interval 22 (b. 444). Pitch interval 13, which appears six times, is emphasised in Heininen’s musical language in general—both in melodic lines and in vertical chords (Jaakkola, Citation2020, 13–16). The genuine 12-tone melody in bb. 430–433 is the only continuous vocal line in “Etyde III”. Brief melodic fragments are almost always interrupted by various kinds of vocal noise, such as speech, whistling, murmuring, screaming or strong inhaling. Momentarily the soloist is stuck repeating a single pitch on a semiquaver quintuplet. Furthermore, in places only approximate pitches are given in the notation—as in bb. 441–442, in which the partial shapes of the melodic line are given. The corresponding notation appears in Silkkirumpu (see Figure ). As for the expressive qualities, the dynamic level changes unexpectedly from extreme forte or sforzando to piano. As Figure shows, secondary parameters such as register, timbre and dynamic volume play significant roles in contemporary vocal music; Leydon (Citation2013), Hanninen (Citation2012) and Howland (Citation2015) discuss the issue.

Figure 5. Reality, “Etude III”, bb. 428–444: the soprano’s part. © Fennica Gehrman, Helsinki. Printed with the permission of the publisher.

In sum, the compound components in the soloist’s vocal part in Reality create an unpredictable, fragmentary and extremely passionate musical expression. Given the topic the music seems to reflect the puzzlement and anxiety of the poetic Self, caused by the scattered, absurd and schizophrenic reality. The frequent shifts between extreme registers as well as between extreme dynamics or vocal qualities could express her incapability of maintaining coherent subjectivity. Related poetic themes appear in Heininen’s Silkkirumpu, which I discuss below. The text begins with a brief presentation of the opera. Thereafter, excerpts from its vocal parts are examined from viewpoints that have significance in the operatic repertoire in general. I will describe 1) how the departure from the surrounding musical language draws attention to specific dramatic aspects; 2) how specific features of the vocal characterisation reveal the dramatis personae’s ironic attitude; 3) how the directed transformation of the vocal characterisation creates a musical narrative that reflects the aligning dramatic process; and 4) how assimilation of the characters’ vocal characterization figuratively depicts the change in their relations.

4. Vocal characterisation of the dramatis personae in Silkkirumpu

Paavo Heininen’s post-serial opera Silkkirumpu (The Damask Drum) was premiered at the Finnish National Opera in 1984 (Heininen, Citation1981-1983). The libretto, written by Heininen and Manner (Citation1984), is based on the Japanese noh play Aya no Tsuzumi, attributed to Zeami (Hare, Citation1986; Nogami, Citation2005). The overall organisation of Silkkirumpu follows the practice of Italian number operas: all recitatives, arias and ensembles are clearly separated. There is also an orchestral introduction as well as two large interludes and an epilogue, which the orchestra performs together with the chorus. The main characters—the old Gardener (baritone), the young Princess (soprano) and her Courtier (tenor)—are introduced in the opening section (“Vision”; numbers I—V). The events begin in number V when the Courtier delivers the Princess’s false promise of love to the Gardener as his prize for making music with a mute damask drum. The second section (“Life-Cycle”; numbers VI—XII) depicts how the Gardener spends his life on hopeless attempts at drumming, loses his mind and commits suicide by drowning himself. The rest of the opera (“Retrospect”; numbers XIII—XVIII) takes place in eternity, illustrating the Gardener’s revenge on the Princess.

The musical characterisation of the soloists’ parts in Silkkirumpu is a central dramatic device. The dramatis personae are introduced musically through their vocal characterisation upon their first appearances onstage. The Princess is seen and heard for the first time in number II, “Duetto”, as she walks in the palace garden with her Lady-in-Waiting. She is introduced musically in her opening statements, which manifest general features of Heininen’s musical language as well. However, her vocal statements in the midst of “Duetto” depart significantly from the surrounding material and thus deepen her musical portrayal.

The music in bb. 107–110 consists of the Princess’s opening phrases (Figure ). In terms of vocal quality, she begins humming a bocca chiusa and goes on singing a vocalise. The soft, cantabile expressive quality of her singing is indicated by the legato slurs and the piano marking. Rhythmic regularity is weakened, because many of the melodic units begin on a weak semiquaver and there are several ties. Rhythmic irregularity is also a typical feature in the Princess’s part later on in the opera. The frequency of large intervallic leaps draws attention to the pitch structure: of the total of 24 unordered pitch intervals, eight are larger than interval 10; interval 11 occurs seven times, and there is one occurrence of interval 13. Because the large leaps appear close to each other and the direction of the intervals constantly changes, the melodic lines sound unpredictable and capricious. The melodic range is wide (pitch interval 19 in both b. 108 and in b. 110). Most of the small pitch intervals occur in the fast quintuplet-figures embellishing their primary pitches, which is the pitch G in b. 108 and the pitch F in b. 110. The rhythmic irregularity, the unexpected accents and the complex intervallic structure in her vocal part might suggest her capricious and impulsive character.Footnote13

Figure 6. “Duetto”, bb. 107–110: the princess’s part. © Fennica Gehrman, Helsinki. Printed with the permission of the publisher.

The characterisation of the Princess is deepened in the middle section of her “Duetto” with her Lady-in-Waiting (bb. 147–163; Figure shows bb. 147–153). Compared to the previous example, there are notable contrasts in the melodic and the rhythmic structures of her vocal phrases. The melodic lines flow with greater ease due to repeated pitches, pitch pairs and stepwise motion. The impression of simplicity is primarily attributable to the rhythmic regularity. The passage in bb. 147–163 is extraordinary in Silkkirumpu: a regular metre, indicated by symmetrical time signatures (3/8, 6/8, and 9/8), is supported and maintained long enough to attract the listener’s attention within Heininen’s otherwise complex, unpredictable rhythmic structure.

Figure 7. “Duetto”, bb. 147–153: pastoral topic in the Princess’s part. © Fennica Gehrman, Helsinki. Printed with the permission of the publisher.

As I read them, these new features in her vocal characterisation appear as intertextual references. The rocking rhythm in bb. 147–163 is the most salient feature of sicilienne, a dance linked with a conventional pastoral topic: the pastoral topic has been associated with idealised nature and innocence of peasants since the seventeenth century (Monelle, Citation2000, p. 25; Haringer, Citation2014, 204–208). Melodic and harmonic simplicity are present in the Princess’s vocal phrases, yet only in comparison with the surrounding music.Footnote14 Interpreted from the perspective of her characterisation, the pastoral music portrays a young, flighty maiden walking in the palace garden and exchanging empty words with a friend. The Princess’s musically underlined innocence may be ironic. The sudden simplicity in her vocal part could reflect her carefree and childish character, which in the course of the drama leads to tragic consequences.

4.1. Musical irony signalled by vocal characterisation

In an operatic context, the vocal characterisation may include features that reveal the character’s attitudes or opinions of the ongoing events. Furthermore, certain features may lead the audience to question the character’s words or actions. Contradictory or incongruous aspects in their performances might arouse misgivings about the meaning and the reliability of their message and encourage the audience seek an alternative interpretation. The kind of distanced or critical attitude is a fundamental aspect of irony, which is evoked by the tension between the overt and the covert layers of meaning.Footnote15 The following text discusses the Courtier’s vocal characterisation in number V, “Promesso”, in which the incongruity between the character’s words (the overt message) and his music (the covert message) raises doubts about his reliability and allows for an ironic reading. Musical irony in the Courtier’s vocal part is signalled by an exaggerated expression and specific musical features, which together create the impression of humour, thus making the Courtier a comic character.

The Courtier delivers the Princess’s orders and promise to the Gardener. As a messenger from the imperial palace, he must give a dignified performanceFootnote16:

The Courtier’s words in “Promesso” are certainly dignified, but his music, on the contrary, adds a comic nuance to his message (Figure , bb. 352–354). On the one hand, the intervallic structure and the extreme expression convey the impression of exaggerated pomposity, but on the other hand, the repeated ideas and strikingly steady rhythm in his part might imply the simple mind of an honest servant.

Figure 8. “Promesso”, bb. 352–354: the Courtier’s part. © Fennica Gehrman, Helsinki. Printed with the permission of the publisher.

The melodic structure of the Courtier’s vocal part constantly includes large intervallic leaps in opposite directions, thus connecting the extremes of his tessitura. The melodic line seeks his focal pitch A♭4, which is repeated prominently on downbeats. The accents on every single note in the melismatic figures make the Courtier sound hurried and breathless. In addition, his eagerness as a messenger is perhaps reflected in the constant fortissimo dynamic level.

The exaggeration in the Courtier’s music reaches its extreme at the end of “Promesso”, at the moment the false promise is spoken (Figure ). The word saat (you will) in b. 364 is set to a showy musical idea, wherein the Courtier’s focal pitch (A♭4= G♯4) in the high register is at first extended and then connected with the extremely low note of his tessitura. The focal pitch A♭4 is associated with the words saat (you will [see]), rakastamasi (your beloved) and naisen (woman) as if the Courtier were eagerly trying to convince the Gardener of the possibility opened up by the Princess’s promise. Given the capricious, unsettled rhythmic structure in Silkkirumpu, the striking number of repeated, equal note values in the Courtier’s lines give the impression of harping.

Figure 9. “Promesso”, bb. 360–366: the Courtier’s part; the appearances of his focal pitch are marked with arrows. © Fennica Gehrman, Helsinki. Printed with the permission of the publisher.

I would interpret the exaggerated elements in the Courtier’s vocal part as markers of the comic aspect of his role. The idea of casting a servant as a comic character dates back to ancient Greek theatre and the Renaissance commedia dell’arte (Halliwell, Citation1987, p. 36). The same setting was common later on in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century opera, a well-known example being Leporello in Mozart’s Don Giovanni. The comic aspect is usually made clear to the audience through stylistic exaggeration, exaggerated mimes and gestures, or with peculiar locution (Lennard & Luckhurst, Citation2002, 76–80; Cicali, Citation2009, 88–93). Inherent in the comic aspect of the Courtier’s vocal characterisation in Silkkirumpu is the potential for ironic interpretation: the whole affair of the mission and its prize seems unbelievable because it is narrated by a messenger who has ridiculous traits. Moreover, the Courtier’s exaggerated, unnatural performance at the precise moment of the false promise (b. 364) gives the impression that he knows very well that the damask drum will not sound, and he mocks the Gardener. The Gardener, ignorant of this possibility, begins his drumming attempts eagerly. Gradually, he realises that he has been cheated. He goes mad in his shame and despair and commits suicide. This mental process is depicted in the transformation of his vocal characterisation, which I discuss below.

4.2. Transformation of the vocal characterisation as a narrative device

In general, the operatic characters are identified musically by their initial vocal delivery at their first appearances onstage. As the drama unfolds, they react to the events and changing circumstances, and these reactions affect the vocal characterisation. The gradual development of or sudden changes in the components of the vocal characterisation reflect even the most subtle changes in the mental state of the characters. The portrayal of the Gardener’s mental breakdown is a central narrative in Silkkirumpu, and the gradual transformation of his vocal characterisation is the musical means of expressing this process. The last stages of the Gardener’s life are depicted in his mad scene “La Follia I e cadenza” (number XII), in which the secondary parameters play significant roles. As the changes in several parameters align, the impact is mutually strengthened.

The text consists of only four poetic lines, but it is considerably expanded in the musical score by means of fragmentation that proceeds in parallel with the transformation of the Gardener’s vocal style. He expresses his anger in the first and second lines, which is an understandable reaction in his situation. The third line covers a longer period of time, during which the Gardener considers the idea of drowning himself, yet in growing horror he hesitates to act. By the time he reaches the last line he has fallen into a fatal psychosis and runs into the lake. In my reading of this, syllabic singing, continuity, motivic coherence as well as precisely notated rhythms and intervals in the Gardener’s vocal part are all connected with his rational mental state, whereas recited, fragmentary musical ideas as well as inexact rhythms and intervals reflect his psychotic, irrational states of mind. Table shows how the narrative is manifested in the Gardener’s transforming vocal characterisation.

Table 3. The directed transformation of the Gardener’s vocal characterisation in “La Follia I e cadenza”

The number begins with a cry of pain, composed as microtonal circulation around a single pitch D4 (Figure ). The music resembles a trembling voice, which shows the character’s extreme emotional anguish, and so adds a paralinguistic aspect to the passage. The rapid, accentuated pitches create the impression of crying. The expressive, continuous 12-note melody in bb. 887–895 contains many large intervallic leaps, reaching the extremes of the soloist’s tessitura. The aggregate is divided into two successive chromatic subsets [D, D♭, B♭, C, B] and [G, G♯, F, E, F♯], followed by the dyad [A, E♭]. A recurring motive enhances cohesion, realising three varied forms of the chromatic trichord (012) in b. 893 and bb. 896–897. The Gardener’s music in bb. 889–898 thus manifests rationality and reflects the dramatic situation: his extreme frustration is a reasonable, justified reaction. However, in b. 899 the repetition on a single pitch with equal rhythmic values seems to reflect the obsessive thoughts in which he is already trapped.

Figure 10. “La Follia I e cadenza”, bb. 885–899: the Gardener’s part. © Fennica Gehrman, Helsinki. Printed with the permission of the publisher.

The Gardener’s “Cadenza” begins with a three-part, pseudo-polyphonic solo passage in bb. 907–909 (Figure ). The text appears disjointed, fragmented and multi-layered. Each of the three layers is combined with certain musical features. The content of bb. 907–909 can be separated into three voices (Figure ):

Figure 11. (a) “La Follia I e cadenza”, bb. 907–908: the Gardener’s part; the notation follows Heininen’s manuscript. © Fennica Gehrman, Helsinki. Printed with the permission of the publisher. (b) “La Follia I e cadenza”, bb. 907–908: the separate pseudo-polyphonic voices.

Voice 1 employs relatively long note values and thus becomes a continuous melody line, performed mezzo piano. The vocal range is limited, the melody proceeding mostly in half steps. The slowly unfolding Voice 2, the “cantus firmus”, closely follows the original poetic line. Each rhythmic value is a semiquaver, articulated sforzando. The individual, unexpectedly occurring notes of this voice sound like sudden cries. The poem’s syllables appear in a completely irrational order in the embellishing Voice 3, which consists only of a stepwise or microtonal figuration on semiquavers. The rapid figures in pianissimo create the impression of manic spluttering. When performed together, the voices of the pseudo-polyphony sound arbitrary and irrational. The multi-layered text, together with the pseudo-polyphonic musical structure, reflect the Gardener’s split mind and disorganised thoughts.

The recitation becomes more and more fragmentary towards the end of “Cadenza”, depicting the Gardener experiencing symptoms of psychosis (Figure ). Instead of one speech melody there is a two-part pseudo-polyphonic passage composed into a multi-layered, phonetic text. In Voice 1 the Gardener stammers his syllables on semiquavers, reciting them in varying registers, at first mezzo piano and later piano. Voice 2 creates a dynamic and registral contrast to the first voice. The scattered syllables sound like sudden, insane screams, first in the high register, then sinking into the low register. The Gardener’s decision to drown himself is delivered sforzando emphasising syllables HU-KU-TA[N] I-TSE-NI (I will drown myself). The transformation of the Gardener’s vocal characterisation has reached its ultimate end: the exact pitches, intervals and exact rhythmic structure are replaced by inexactly notated Sprechstimme. The Gardener keeps babbling the poem’s syllables in a low register, staccato in a piano nuance. His extremely fragmented vocal statements represent irrationality and his descent into altered states of consciousness.

Figure 12. “La Follia I e cadenza”, bb. 929–930: the Gardener’s part. © Fennica Gehrman, Helsinki. Printed with the permission of the publisher.

I will now sum up the Gardener’s mad scene as a whole. The process of text fragmentation and the simultaneous, progressive changes in the soloist’s vocal characterisation create an effective metaphor for his mental breakdown. The parallel processes proceed to the critical point at which it is no longer possible to identify two distinct media. The sonic qualities of the text have primacy over its linguistic meanings, and Sprechstimme comes close to language and speech. The Gardener’s obsession could be reflected in the stuttering and the musical repetition.Footnote17 Heininen’s number may be intertextually linked with Schönberg’s Pierrot Lunaire (1912), in which the use of Sprechstimme serves as a model of madness expressed through speech-like vocal qualities. Likewise, Peter Maxwell Davies’ Eight Songs for a Mad King (1969) with its vocalised madness and extended vocal techniques belongs to the intertextual network of mad scenes (Welten, Citation1996; Williams, Citation2000, 81–82).Footnote18

4.3. The characters’ developing relations indicated in their vocal parts

In the musical dramaturgy of opera, assimilating traits in the characters’ vocal parts tend to signal similar attitudes, mutual understanding or developing relations. Richard (Citation1983), for example, explains how the changes in the relations between soloists’ parts reflect the text content in several seduction scenes in Mozart’s operas Così fan tutte and Don Giovanni. The two characters sing their stanzas or phrases in turn at the beginning of the seduction scenes, as a reflection of their conflicting intentions, whereas at the end, when they are acting in harmony, they sing a duet, often performing a single melody in parallel thirds or sixths (Richard, Citation1983, p. 153). This textural change in Mozart’s music seems to align with the significant changes in the characters’ attitudes indicated in the text.

The same phenomenon is evident in Heininen’s Silkkirumpu, too. As mentioned above, the latter part of the opera depicts the Gardener’s revenge on the Princess: she, too, goes mad and, as a punishment for her betrayal, she is forever tortured by the Gardener. The Princess and the Gardener, whom destiny has joined, cannot free themselves of hate, but endlessly curse each other in eternity. This dramatic theme is depicted in the music through the assimilating traits in their vocal parts. The characters gradually adopt features of each other’s vocal characterisation and finally assimilate into an inseparable vocal character in their duet in the final scene (“Duetto con coro”, number XVIII c).

The endpoint of the process is when they make their statements in bb. 1694–1698 (Figure ). Both the Princess and the Gardener simply repeat the single word kirottu (“cursed”). Their vocal qualities, the expressive qualities and the rhythmic structures are practically identical in their combined vocal character. Given the pitch structure, the use of registers, the directions and relative sizes of the pitch intervals and the pitch content are dependent on each other, controlled by certain structural principles.

Figure 13. “Duetto con coro”, bb. 1694–1698: the characters’ assimilated vocal characterisations. © Fennica Gehrman, Helsinki. Printed with the permission of the publisher.

The singers mainly employ contrary motion in their two-part texture, with a momentary tendency towards inversional symmetry. Together the parts form a closing wedge, the two gradually approaching one another until reaching pitch interval 1 (F♯–G) in the last musical shape. Moreover, in combination the parts complete the 12-tone aggregate. The expressive curve of the passage constitutes a process of intensification in several musical parameters. Each of the musical shapes in the Princess’s part realises the melodic contour < 201>Footnote19, yet the melodic intervals tend to diminish in size, and the range of melodic shapes is condensed. The tendency to ascend and a gradual diminishing of the intervals are also evident in the Gardener’s part. Parallel to the compressed intervallic structure in the sequential musical segments, the rhythmic values gradually diminish, thus giving an impression of acceleration and growing tension. The goal-oriented, closing melodic wedges in the contrapuntal structure effectively lead the assimilation process to its end. The contrary motion in the character’s contrapuntal structure may well indicate that, although the characters share the same destiny as well as similar emotions, their relationship is ultimately negative.

As explained above, Heininen’s idea of using the developing relationship between the soloists’ vocal characterisation as a dramatic device is not unique. His musical language is, of course, very different from Mozart’s, and the characters in Silkkirumpu join in hatred, not in love. Nevertheless, the build-in analogy between the characters’ merged destinies and the assimilation of their vocal parts in Silkkirumpu resembles Mozartian practice. This example, among others, shows that Silkkirumpu’s versatile vocal characterisations used as dramatic devices essentially draw on the operatic tradition.

At this point, let us compare The Autumns, Reality and Silkkirumpu from the perspective of vocal characterisation. Certain musical features, such as the complex rhythmic structure, the avoidance of a regular pulse, a complex, atonal pitch structure as well as extreme expression, are perceptible in all these pieces, and thus belong to Heininen’s musical language. Within the limits of his musical language, he combines the musical parameters to create unique vocal characters. As Figure of the Princess’s pastoral music shows, marked passages that depart from the surrounding material may reveal significant dramatic aspects. Therefore, vocal parts should be observed in relation to the composer’s practice in general, as well as in the context of a certain work and its traits.

The musical characterisation of the poetic voices in The Autumns resembles Heininen’s practice in constructing the characters’ musical portrayals in Silkkirumpu: the two poetic voices—the English Self and the Japanese Self—are so distinctive that they indeed sound like two separate characters in an opera. Given the correspondence between Reality and Silkkirumpu, in both works the concertante vocal parts require virtuosic control of extended vocal techniques. Likewise, speech-like types of vocal production (such as Sprechstimme, screaming, whispering, whistling, murmuring, laughing, crying) as well as inexact rhythmic and intervallic content appear frequently in both compositions. However, whereas directed transformations in Silkkirumpu from singing to speech-like vocal qualities as well as from exact intervallic and rhythmic content towards inexact recitation form musical narratives that proceed in parallel with the dramatic processes, no corresponding practices are to be found in Reality. The soprano’s various extended vocal techniques manifest virtuosity, but only in a few places in Reality can the changes in her vocal quality be linked to exact aspects of the text.

As Figure shows, pseudo-polyphony appears in Reality as a musical metaphor for the character’s disorganised mind, but the idea is far more developed in Silkkirumpu. Of course, in Reality the constant alternation between extreme registers, between extreme dynamic volumes, as well as between extremely different vocal qualities reflects the overall topic of Reality – namely the unpredictable, scattered and chaotic nature of reality. Kaipainen’s (Citation1989) claim that Reality is a concerto for soprano seems justified: whereas the vocal writing in Reality creates the impression of an experiment with extended vocal techniques, in Silkkirumpu the vocal writing primarily reflects the dramatic content. Moreover, the directed transformation in the vocal characterisation indeed brings out the combined effect of the musical parameters in Silkkirumpu: firstly, the impact of secondary parameters such as expressive and vocal qualities is highlighted, and secondly, the aligning changes in several parameters strengthen their effects and clarify the reference to the drama.

5. The vocal characterisation in Saariaho’s Adriana mater

The previous examples originate in Heininen’s oeuvre, but related ideas are perceptible in Kaija Saariaho’s opera Adriana Mater (Citation2005).Footnote20 In this work Saariaho, who studied composition as a student of Heininen, creates musical portrayals of the dramatis personae using their distinctive vocal characterisation. Heininen and Saariaho differ in terms of musical languages, as well as in their practices of vocal characterisation.

Adriana Mater comprises two acts, which are divided into seven scenes (tableaux). The story is set in a nameless war-area. The events portrayed in Act I (Tableaux 1–3) happen before and during the war, whereas those in Act II (Tableaux 4–7) happen post-war: there is a seventeen-year temporal gap. The cast includes Adriana (mezzo-soprano), her sister Refka (soprano), Adriana’s son Yonas (baritone) and his father Tsargo (bass-baritone). Adriana, the main character, having been raped by a soldier, Tsargo, who was known to her, falls pregnant and gives birth to Yonas. Bringing him up, she struggles with the fear that her son, through his father’s blood, will be a monster. “Is he Cain or Abel?” she asks her sister Refka. At the age of seventeen Yonas finds out the truth about his father. He meets Tsargo and vows to shoot him. However, he cannot do it: he is not a killer. In fact, he feels sorry for the old, blinded Tsargo.

In an interview with Stephen Pettitt Saariaho explains how each dramatic agent in Adriana Mater is musically identified by a specific tempo, a specific rhythmic structure as well as a specific melodic and harmonic construction. In addition, a certain orchestral timbre accompanies each character (Pettitt, Citation2006, 285–288).Footnote21 The dramatis personae express themselves through their vocal characterisation, and any transformations reflect certain aspects of the drama (Table ). Tsargo’s lively tempo in Act I (♩ = 108), for example, portrays him as a young, physically strong soldier. The tempo slows down (♩ = 48) in Act II, which takes place 17 years later, to depict his old age and his war-related disabilities. Significantly, the tempo allocated to Yonas (♩ = 108) is exactly the same as the lively tempo of his father. The rhythmic construction in Yonas’s vocal part is based on thirds of quaver triplets: the fast fundamental note value presumably reflects his young spirit.Footnote22 In terms of melodic construction, the vocal lines of the male characters consist of chained intervallic cells, whereas those of the female characters manifest particular modes. Below I briefly discuss the characterisation of each dramatic agent. I kindly ask the reader to find the musical examples of Adriana Mater’s vocal parts either in the printed score (Saariaho, Citation2005b) or in the full score, which is openly available on the composer’s official webpages (Saariaho, Citation2005a).

Table 4. The vocal characterisation in Saariaho’s Adriana Mater

According to Saariaho, the melodic structure of Refka’s vocal part manifests diatonic modes. Her vocal lines indeed imply various modes, but the impression is mostly fleeting and soon gives way to another one. Nevertheless, the pitch collection of E minor appears several times. As I read it, the striking feature of Refka’s vocal characterisation is a heavy emphasis on the hexatonic collection, set class (014589), the various realisations of which she performs throughout the opera. Depending on the unfolding of the pitches, the set class may imply various major or (harmonic) minor modes. The successive pitch intervals 1 and 3, originating in the hexatonic collection, give an oriental tinge to her music. Related set classes that appear in other vocal parts and in the orchestra have an impact on the overall oriental colour of the harmony in the opera.Footnote23

The above-mentioned musical features can be recognized in Refka’s solo in Act I, , bb. 410–414 (pp. 172–173 in the full score). In this instance the symmetric set class (014589) is realised on pitch collection [F♯-G-A♯-B-D-E♭]. The content of bb. 410–412 seems to imply G minor in unfolding a G minor triad and the leading tone of the key. However, the intervallic structure in bb. 413–414 suggests a turn towards B minor. In some other instances, depending on the intervallic structure, the same pitch set might give the impression of a major mode.Footnote24 Furthermore, as Figure shows, the same pitch collection might imply other modes, and the transpositions of the hexachord extend the variety.

Figure 14. Realisations of the hexatonic collection, set class (014589), implying various modes in Refka’s part.

The feature that draws one’s attention in Tsargo’s vocal characterization is his recurring motive, the intervallic cell (014), with which he constantly addresses Adriana in Act I. Figure shows the motive’s most common realisation [D♯-E-G], which in this instance might imply E minor (see Act I, , bb. 65–66 on p. 74 of the full score). The motive also appears transformed (see, e.g., bb. 224–226 on pp. 92–93) and inverted (see, e.g., bb. 240–241 on pp. 94–95). The perceived similarity between the motive and its varied forms is based on their similar shapes: the motive’s melodic contour is maintained although the exact intervals vary.Footnote25 Likewise, the rhythmic contour and accentuation are usually kept similar, although the note values are different. The motive gains thematic and symbolic significance in that it is associated with the object of Tsargo’s longing.

Adriana is identified musically by her initial vocal characterisation, which is the most distinctive in the opera (see Act I, , bb. 58–81on pp. 7–8 of the full score). Her cantilena lines include constantly recurring melodic patterns constructed on the pitch collection of D minor. Her initial vocal characterization seems to appear in the musical sections in which she expresses hope and optimism, whereas the pitch collection is transformed to hexachord [D-E♭-F-G♭-A♯-B] (013478) in the sections depicting her doubt, confusion and despair (see Act I, , bb. 389–399 on pp. 169–170 of the full score; see also Act II, , bb. 56–278, pp, 199–224).

Let’s now discuss Yonas’s lines. The rhythmic structure in his vocal part is based on thirds of quaver triplets, but after several changes in tempi and time signatures, the fundamental note value is transformed to quavers in 6/8 time. The recurrent pitch interval 6 draws attention in his melodic lines, often forming a dyad with a semitone (016) or expanded to a tetrachord (0167) as in Act 2, , bb. 52–54 (pp. 261–262 in the full score). Another significant feature of his vocal characterisation is the frequently appearing pitch set [D-E♭-F-F♯-B♭-B] or its subset [F-F♯-B♭-B] (see, e.g., Act 2, , bb. 376–381 on p. 238 and Act 2, Tableau 7, bb. 386–401 on p. 383). In that the pitch collection originates in Adriana’s secondary vocal characterisation, its appearances in Yonas’s lines might figuratively depict the close relationship between mother and son. Occasionally, Adriana and Yonas together complete this very hexachord in their aligning statements (see Act 2, , bb. 458–460 on p. 391; see also , bb. 446–456 on pp. 389–390). Thus, Yonas’s music includes features of his parents’: his fundamental tempo is adapted from Tsargo’s part, yet with Adriana he shares the exact pitches.

Saariaho’s musical language in Adriana Mater differs significantly from Heininen’s in Silkkirumpu: in general, the vocal lines are more continuous in construction. Large intervallic leaps and frequent shifts between the registral extremes that draw attention in Heininen’s work, appear rarely in Saariaho. By contrast to Heininen’s extremely intense vocal expression, the expressive means in Saariaho’s piece are relatively moderate. The features of the musical language naturally also have their impact on the musical characterisation.

The speech-like vocal qualities in Heininen’s Silkkirumpu, as well as the various expressive qualities, are essential components of the vocal characterisation. The directed transformations in the soloist’s characterization permeate all musical parameters. The perceivable changes in the soloists’ characterisation in Saariaho’s Adriana Mater concern their melodic construction and their transforming pitch collections, and they are often abrupt. Adriana’s initial and secondary characterisations form an opposite pair that becomes a musical metaphor for her alternating feelings of confidence and doubt. Along with single exclamations here and there, Sprechstimme is used persistently in two scenes in which the vocal quality seems to depict the character’s undesirable attitude. Tsargo expresses himself by means of Sprechstimme in as he tries to seduce Adriana before turning to violence. The striking change to Sprechstimme in Refka’s vocal quality in reflects her attitude: she insists that Adriana should not give birth to the child.

As discussed above, the operatic characters often adapt features from each other’s vocal characterisations when expressing similar emotions or acting in harmony. This phenomenon is also evident in Saariaho’s Adriana Mater. Refka, who is Adriana’s sister and thus empathic and loyal to her, adapts Ardiana’s initial vocal characterisation in their duets (Act I, , bb. 461–472 on pp. 54–56 and Act II, Tableau 7, bb. 67–79 on pp. 340–342). In , entitled “Adriana”, the horrors of the past fade and the characters perform a quartet in which they all adapt Adriana’s initial pitch collection (bb. 64–90 on pp. 342–343). The opera’s final, optimistic statements are sung by Adriana in her initial vocal characterisation (bb. 601–611 on pp. 406–407).

6. Conclusion

To conclude, the concept of vocal characterisation, in which vocal parts are considered compound analytical objects, is an apt and flexible tool for studying contemporary opera and vocal works, as well as earlier repertoires. Moreover, the discussion could be extended further. Many recent studies on opera (e.g., Everett, Citation2015; Symonds & Karantonis, Citation2013; Álvarez et al., Citation2010) discuss the performative aspects of a stage work instead of settling for examining the libretto and the musical score. Thus far I have focused completely on the composer’s contribution and on a close reading of the score, but the analytical approach could be expanded to cover the unique aspects of individual performances as well: mimes, bodily gestures and movements may be significant components of the soloist’s expression in other contexts and should not be ignored. For example, the character’s madness in Davies’ Eight Songs for a Mad King is manifested in the soloist’s extended vocal techniques, and largely also in his physical acting, which could be examined along with his music. Directions for extra-linguistic messaging may be indicated in the operatic score, but if they are not, the soloist or the stage director could invent them during the preparation stage.

There is growing interest in the unique performance styles of famous soloists among scholars focusing on performance studies (e.g., Schneider, Citation2013, 103–117; Heile, Citation2006). Recordings and videos give rich information about the singers’ characteristic vocal expression and acting. Although these qualities are audible and visible in the performances, they are not included in the musical score. Detailed realisation of agogics, tempi and dynamics, the use of vibrato, ornamentation and glissandi, as well as bodily gestures and movements are essential means for creating the personal interpretation of an operatic role. The discussion on vocal characterisation could be extended to unique performance styles. Furthermore, the extensive archive of recorded performances covering more than a hundred years makes it possible to listen to historic recordings and thus to learn about the characteristic performance practices in a certain time period. The comparison of historic recordings could also highlight significant changes in performance practice. Indeed, vocal characterisation, as created by the composer and indicated in the score, yet particularly in connection with other dimensions of performance, could yield versatile and detailed analytical material on features and aspects that would be fruitful for the research in question and relevant in the context of specific compositions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Inkeri Jaakkola

Doctor of Music Inkeri Jaakkola completed her studies at the Sibelius Academy of the University of the Arts Helsinki. Her doctoral dissertation Beneath the Laurel Tree: Text-Music Relationships in Paavo Heininen’s Opera Silkkirumpu (The Damask Drum), op. 45 was published in 2020. Jaakkola’s scholarly interest is focused on music analysis and on interdisciplinary studies combining approaches of various arts and research fields. Jaakkola works as a permanent lecturer of music theory at the Sibelius Academy. In addition, she is a composer, and her works are available either published or in the Music Finland Sheet Music Library.

Notes

1. The issue has been recently discussed by Duncan (Citation2004) and Novak (Citation2015).

2. Meyer’s (Citation1989, 14–16) categories of primary and secondary parameters are widely used. The primary parameters are syntactic: they are hierarchical in nature and thus, in relation to each other, can create a closure.

3. Heininen wrote only in Finnish. In his article “Sarjallisuus” (Serialism) he gives a thorough list of musical parameters, including categories and subcategories of pitch organization, harmony, rhythm, dynamics, topics and timbre (Heininen Citation1998, 58–62). He calls his compositional practise “multi-dimensional serialism”, not as a strict serial technique, but as an aesthetic ideal of creating a balanced artistic expression in which all parameters are of equal importance and create a compound effect. He writes: “Kunkin parametrikäyrän mitoitus on laadittava siten, että ne yhdessä tukevat ja selventävät toisiaan.” (The parameters must be composed so that together they strengthen and clarify each other; ibid., 70) and further (ibid., 81) “Komplekseihin kokonaisparametreihin voi sisältyä myös … semanttisia parametreja. Kuulumattomien rytmien, näkyvien viiva- ja väri-intensiteettien, kielen foneettisen ja kuvallisen sisällön osalta Silkkirumpu onkin juuri laajennettua sarjallisuutta.” (Some of the complex parameters can be … semantic. In Silkkirumpu the soundless rhythms, visible intensities of colours and lines, the phonetic and symbolic content of language are parameters in expanded, multi-dimensional serialism.) Translations by the author.

4. Rothstein (Citation2008) describes appearances of focal pitch in the context of Italian Romantic opera, yet considers the phenomenon related to pitch centricity in twentieth-century music.

5. For example, Agawu (Citation1992) and Suurpää (Citation2014, 50–58) discuss various starting points for studying the relation between text and music.

6. Composing for voice is discussed already in Rimski-Korsakov’s Principles of Orchestration (1912; Rimski-Korsakov & Šteinberg, 1964, 132–139). Along with explaining the properties of voice categories, the author gives advice for setting the text and for use of vowels, in particular.

7. Orchestral characterisation is discussed in studies of certain operas. See, for example, Everett (Citation2006, 170–200; Everett, Citation2013, 329–345; Everett, Citation2015), Jaakkola (2020), Rupprecht (Citation2001, 32–106, 245–289) and Weigel-Krämer (Citation2012).

8. After completing works for piano op 32a and 32b (Heininen, Citation1978b) Heininen abandoned the strict serial technique.

9. I use Straus’s (Citation2005) concepts in my discussion of the musical examples.

10. Cone (Citation1974) introduced the concept of musical persona, which is recently discussed in Hatten (Citation2019).

11. Reality’s instrumental ensemble includes flute (muta piccolo), oboe (muta English horn), clarinet in Bb, bassoon, horn in F, piano, violin, viola and violoncello. A single percussionist handles vibraphone, marimba, tubular bells, campanelli, bongos, side drums, tom-tom, claves, castagnets, temple blocks, cowbells, maracas, flexaton, vibra-slap, cymbals, triangles and crotales. Reality’s large percussion section is a feature in common with Silkkirumpu.

12. Unfortunately, there is no recording of the premier of Reality. However, another performance was recorded by the Finnish Radio Broadcasting Company (YLE Finland). Jane Manning performs the piece with the Avanti chamber ensemble conducted by Olli Pohjola. There is a copy of this undated recording in Heininen’s archive, and he kindly allowed me to study it. Jane Manning (1938–2021), who indeed had extensive experience in contemporary vocal music, performs the demanding part passionately, following Heininen’s score in incredible detail.

13. The orchestra also takes part in characterising the dramatis personae in Silkkirumpu. Firstly, Heininen’s orchestration is mostly chamber-like: the orchestral forces are used sparsely, to avoid dominance over the soloists’ voices. The only real orchestral tutti is heard in the opera’s final scene, when the soloists are already silenced. Of course, the orchestration changes throughout the course of the drama, creating a suitable atmosphere for each number. Secondly, the timbre of certain instruments or orchestral sections is chosen to portray the character at their first entrance on stage. The light accompaniment of the flutes in “Duet” supports the pastoral topic and highlights the attributes associated with the Princess’s character. When the treachery of her nature is revealed, the flute is no longer heard with her. The brief (and ironic) introductory fanfare, performed by the orchestral brasses, characterises the Courtier in “Promesso”. The brasses accompany the performances of the dignified messenger later as well. The Gardener is introduced in his “Cantilena”, his actions tightly interacting with the violoncello solo. The association between the character and the instrument, created in the opera’s opening scene, is strong indeed: the cantabile statements of the violoncello solo are easily attributed to the Gardener, even if the soloist is completely silent. The violoncello is, of course, a natural choice for the Gardener’s alter ego: the legato sound of a string instrument is close to the human voice, and the violoncello operates in the register of a male baritone. See Jaakkola (Citation2020, 124–126, 142–144).

14. Frymoyer (Citation2017) draws attention to the essential features of the topics in her discussion on conventional topics and their appearances in contemporary music.

15. On irony in general, see, e.g., Behler (Citation1990), Colebrook (Citation2004) and Klein (Citation2009). Musical irony, in particular, is discussed by authors such as Sheinberg (Citation2000), Everett (Citation2009) and Frymoyer (Citation2017).

16. The Finnish poem is by Eeva-Liisa Manner, the English translation by the author.

17. Howe (Citation2016) and Taruskin (Citation2005, Vol IV, 514, 517–518) discuss the musical manifestation of obsession in various musical contexts.

18. The number could be linked with mad scenes in opera generally. In nineteenth-century Italian opera such scenes usually depict the mental breakdown a female character, portrayed by the virtuosic coloratura technique in the soloist’s part (Pugliese, Citation2004, 23–42; Willier, Citation2002). Along with Verdi’s Othello and Berg’s Wozzeck, there is a male protagonist’s mad scene in Musorgsky’s Boris Godunov and in Britten’s Peter Grimes.

19. On the applications of musical contour, see R. Morris (Citation1993) or Jaakkola (Citation2020, 41–47).

20. Adriana Mater’s libretto was written by Amin Maalauf. The premier took place in 2006 in Paris, the stage director being Peter Sellars. The full score of Adriana Mater is openly available for study on the composer’s official website (see Saariaho, Citation2005a).

21. See also Stoianova (Citation2007).

22. Everett (Citation2015, 87–88) shows Saariaho’s sketches for Adriana Mater’s rhythmic construction.

23. The librettist Amin Maalouf is Lebanese. His experiences of the war in the Middle East had an impact on Adriana Mater’s story and the atmosphere, according to Saariaho (Pettitt, Citation2006, p. 287).