Abstract

Interest in the voluntary non-use of digital technology is growing, as is the number of studies on the subject. However, research on digital disconnection rarely addresses families and relationship between technology non-use and physical activity (PA). The family is a system in which individual elements and processes determine the achievement of homeostasis: cohesion, flexibility and communication. The study answers the question: In the context of achieving family homeostasis, what role does PA play in relation to digital regulation (DR)? To address this, a qualitative study was conducted on 86 individuals from 30 Polish families using semi-structured in-depth interviews supplemented by questionnaire responses. According to the study PA plays a key role in DR by serving as a major alternative to screen time while providing numerous familial and individual benefits. By having all family members reduce technology in solidarity with each other in favor of PA, they support the family cohesion. The variety and variability of forms of DR and forms of movement testify to their flexibility. In turn, the time saved on screen activity and spent together proactively serves to improve their communication.

Reviewing Editor:

There is a growing awareness of the effects of unregulated digital life and the social significance of managing one’s connectivity (Nguyen et al., Citation2022). Studies show that 64.4% of users believe they spend too much time on screen devices, but only 11.3% limit screen technologies (Bigaj et al., Citation2023). At the same time, research on digital disconnection shows the importance of alternative activities. On the one hand, some non-digital activities are reduced or eliminated due to intensive use of technology (Ganito & Jorge, Citation2017; Widdicks et al., Citation2018). On the other hand satisfactory digital technology regulation is shared by those who can find appropriate substitutes for screen activities (Gingold et al., Citation2014). Regular physical activity (PA) is recognized as one of them (Kopecka-Piech, Citation2022). Meanwhile, only 22.8% of users move moderately or intensively for a minimum of 30 min daily (Bigaj et al., Citation2023).

There is a lack of research concerning family contexts in which digital technology regulation takes place, the motivations driving such regulation, strategies for implementation and the perceived effects, even more in the relation to PA. Meanwhile, the family is a system in which users’ habits are formed, becoming part of everyday life (Jordan, Citation2012). Technology use and PA in the family shape the daily lives of adults and children (Matthes et al., Citation2021; Shropshire & Carroll, Citation1997).

The family understood as at least two individuals who live together and are either married or in a cohabiting relationship, with or without children, relies on establishing close connections and attachments, which require time and commitment (Golish, Citation2003). If there is a lack of family time, it can impede the development of relationships and necessitate better organization and consistency. Digital regulation (DR), understood as voluntary and intentional strategy for the use and non-use of digital technologies, by creating more available time promotes a mindful balance between staying connected digitally and disconnecting (Sas, Citation2019). It can also have a positive impact on relationships, known as the relational impact (Hertlein, Citation2012). Such regulation can strengthen relationships with our loved ones and bring about a sense of satisfaction in our connections (Fasoli, Citation2021). From a systemic perspective, it is important to consider if and possibly how PA and DR potentially relate to each other and how this affects the process of achieving homeostasis of the family (Bowen, Citation1993).

Although they make up a small proportion of the population, there are entire families who utilize DR while remaining physically active rather than engaging in digital activities. To understand the circumstances, progression and outcomes of DR combined with PA, it was essential to conduct a study on this particular group. The main inquiry was centered around the significance of PA for DR and, consequently, achieving family homeostasis which can be understood as maintaining family stability in changing external conditions (de Barbaro, Citation1999).

In this qualitative study, the methods of achieving disengagement from digital media are elucidated (Nguyen, Citation2021). The study is conducted within the context of the family system (Jordan, Citation2012), revealing how familial support contributes to achieving homeostasis through coherence, flexibility and communication (Olson, Citation2000). The study shows the families’ perceived motives for regulating digital activities, types of regulations and the role of the PA in it. The novelty and uniqueness of the study are in providing knowledge about the key role of PA in DR, serving as a major alternative to screen time and providing numerous familial and individual benefits.

Research context

Family system

In the interdisciplinary systemic concept of the family, coming primarily from sociology and psychology, the family is regarded as a complete unit with its own distinct environment, distinctive way of life and a network of interrelationships among its members (Cox & Paley, Citation1997). The family is an ongoing, purposeful and self-regulating system (Coyne et al., Citation2014). Rather than simply being the combination of its individual members, each family is a distinct entity that strives for balance between change and stability (Cierpka, Citation2003). The concept of homeostasis originates from the natural systems theory (Bowen, Citation1993; Rambo & Hibel, Citation2012). Because family members share physical and emotional closeness and have an impact on each other, the family is viewed in terms of interconnected relationships (Jordan, Citation2012) and integration (de Barbaro, Citation1999).

The goal of the family is to achieve balance in three aspects: cohesion, flexibility and communication (Olson, Citation2000). According to Olson (Citation2000), cohesion refers to the emotional connection within the family and its objective is to ensure togetherness. This includes spending quality time together and sharing common interests and activities. Flexibility pertains to the ability of the family to handle changes, such as establishing rules that govern relationships and decision-making, through negotiation, control and discipline. On the other hand, communication plays a crucial role in facilitating cohesion and flexibility. Family communication involves prioritizing the needs of the family, showing respect, empathy, attentiveness and expressing emotions (Olson, Citation2000). The central idea here is the establishment of positive connections, which signifies good relationships (Coyne et al., Citation2014).

A two-element system, known as a dyad, is considered the smallest type of social system (Felmlee & Greenberg, Citation1999). Within a family setting, the fundamental dyad is formed by a couple or a parent and a child. The analysis of both dyadic families and larger families follows a similar approach based on systems theory (Olson, 2020). Therefore, in this study, families are defined as consisting of at least two individuals who live together and are either married or in a cohabiting relationship, with or without children. This definition includes families with adult children and single parents cohabiting with their children.

Childless couples are recognized as family units because they are regarded as families in terms of their aspirations and actions rather than their mere existence (Neustaedter et al., Citation2013). Similarly to families with children, couples who live together and establish a household also need to fulfill the roles and responsibilities of a family unit. This entails the maintenance and nurturing of the system they have created, and the potential for growth by welcoming additional members into their family. They rely on establishing and maintaining relationships, fostering connectedness and cultivating a positive emotional environment.

In the perspective of the family system, where the interactions among its members are vital, both media technologies and PA play a significant role (Matthes et al., Citation2021; Shropshire & Carroll, Citation1997). The family adopts a strategy to ensure its existence in this aspect. It is also intertwined with the emotional aspect that underlies the family, i.e. closeness, support and availability (Padilla-Walker et al., Citation2012). The concept of homeostasis pertains to understanding how the utilization or non-utilization of media technologies, as well as engagement or lack thereof in PA, contribute to maintaining cohesion, flexibility and communication, and what connections exist between PA and the use (or non-use) of media.

Regulations

For this study, it was postulated that the DR within families is a deliberate and purposeful strategy adopted by adults for their own use, as well as for their children in the case of families with minors. This strategy is reciprocal, i.e. within its framework, family members influence each other. Its objectives are both individual and collective benefits. These regulations are contextualized practices and are part of families’ life strategies, values, norms and rules.

There are many degrees and styles of engagement and disengagement as well as practices of digital disconnection (Baumer et al., Citation2013; Gangneux, Citation2021; Ganito & Jorge, Citation2017). It is mainly studied from the perspective of selected platforms or devices (Baumer et al., Citation2013; Ribak & Rosenthal, Citation2015). There is no consensus in the field on behaviors, practices and activities definitively constitute it. Research mainly emphasizes users’ time constraints (Blum-Ross & Livingstone, Citation2018). Treré (Citation2021) demonstrates how disparities in privileges, imbalances, divisions and inequalities influence disconnection practices. Bozan and Treré (Citation2023) draw attention to the pivotal role played by infrastructure, geography and socio-economic factors in shaping the disparities in digital access and usage.

Previous research often equates DR with parenting (Elias & Sulkin, Citation2019; Sanders et al., Citation2016; Veldhuis et al., Citation2014). There are many typologies of parental mediation understand as interpersonal communication strategies of parents toward their children (Clark, Citation2011; Eichen et al., Citation2021; Livingstone & Helsper, Citation2008; Paus-Hasebrink et al., Citation2019; Steinfeld, Citation2021). They treat regulation as part of child rearing, involving managing time, content or equipment available to children. They rarely address the importance of DR from the adult family member perspective (Hiniker et al., Citation2016; Matthes et al., Citation2021). While there are studies indicating the crucial importance of intimacy and authenticity achieved by digital detox (Enli & Syvertsen, Citation2021; Syvertsen, Citation2020), regulation in childless families is of no interest to researchers. Rare still are studies that explore the relationship between disconnection and other spheres of life, such as PA (Xu et al., Citation2015). There is no such study from a family system perspective.

Physical activity

Family-based participation in regular PA is essential for families (Shropshire & Carroll, Citation1997), especially providing a tool for supporting cohesion. PA builds closeness and good relations (Knoester & Randolph, Citation2019). Studies showed that in child-headed families modeling engagement, with parental involvement is crucial for perceptions of its appeal (Macdonald et al., Citation2004; Shropshire & Carroll, Citation1997) as well as improving children’s engagement in PA (Brzęk et al., Citation2018; Xu et al., Citation2015), also later as they become adults (Hayoz et al., Citation2019).

Generally, there are limited studies and particularly up-to-date research on the relationship between sports activities and screen activities (Shropshire & Carroll, Citation1997; Xu et al., Citation2015), especially in adult life. They are sometimes considered part of a trend referred to as healthism (Fish, Citation2017). One of the latest studies notes the importance of sports for teenagers’ digital disconnection (Jorge et al., Citation2023). The available literature delivers contradictory findings (Macdonald et al., Citation2004) and bidirectional effects (Gingold et al., Citation2014). For instance, it has been shown that those using a computer (Fotheringham et al., Citation2000) or playing computer games (Şirin Güler & Çakır, Citation2020) are less physically active (Kim et al., Citation2023). However, the chances of engaging in PA grow with information seeking on the Internet, including social media (Zach & Lissitsa, Citation2016) or instant messenger use (Kim et al., Citation2023). There is evidence that the use of media technology during PA for children correlates positively (Listyarini et al., Citation2021), but generalized meta-analyses indicate only a 50% success rate of mobile technology interventions in PA (Mannell et al., Citation2005). Intensive use of media technologies in adult PA may even result in its abandonment (Kopecka-Piech, Citation2019), with smartphone use replacing PA due to cost, escapism and communication needs (Mannell et al., Citation2005).

There is limited research on the relationship between media use and family PA. Childless couples are not tested for it. Some parents monitor their children’s physical inactivity and limit their children’s media for sports to be present in their lives, which creates tensions (Macdonald et al., Citation2004). Often, providing PA for children requires parents to forego their own (Macdonald et al., Citation2004). The two spheres strongly interact and influence each other. We do not know why, how and with what effects some families use DR, particularly while being all regularly physically active, and how it supports the homeostasis of the family.

Motives and effects

The motives and effects of disengagement are treated as a multidimensional continuum (Kuntsman & Miyake, Citation2019), also representing analytical limitations (Sutton, Citation2017). Research findings on the overall importance of media in family life are contradictory. On the one hand, higher connections in the family due to media use are found (Padilla-Walker et al., Citation2012). However, it is emphasized that media can weaken communication, promote isolation and reduce family time, intimacy and closeness of relationships (Coyne et al., Citation2014). Miller and Madianou (Citation2012) show the ambivalent effects of mothers’ use of polymedia on the relationship with their children. The results of general studies on the impact of media on relationships, as well as on health and well-being, are also contradictory (Radtke et al., Citation2022). However, users are generally concerned about the degree to which they use their phones (Radtke et al., Citation2022), as well as the consequences regarding social media use (Woodstock, Citation2014), contributing to the growth of technostress (Salanova et al., Citation2014).

Several motives have been identified for why users are beginning to reduce technology use (Baumer et al., Citation2015; Nguyen et al., Citation2022; Syvertsen, Citation2020). A key factor in many studies is time: the sense of time loss, the need to have time for other activities, including for loved ones, strongly motivates regulation (Baym et al., Citation2020; Nguyen et al., Citation2022).

The results of studies on the effects of reducing television in families are known, which include more quality time with family members and improved family communication (Jordan et al., Citation2006; Shropshire & Carroll, Citation1997; Thompson et al., Citation2010). Likewise, the benefits of regular PA are also documented. These advantages are directly related to psycho-physical fitness (Thompson et al., Citation2010; Woodstock, Citation2014) and social competencies (Macdonald et al., Citation2004). Other benefits include tranquility (Nguyen, Citation2021), improved focus and time management, as well as increased productivity and awareness resources (Woodstock, Citation2014). From a family perspective, the benefits of playing and relaxing together are also recognized (Shropshire & Carroll, Citation1997; Thompson et al., Citation2010).

Based on the findings so far, it can be concluded that both PA and DR are important for achieving family homeostasis, at the same time PA and DR influence each other in families. Thus, by researching families uninvestigated so far, i.e. those that are regularly physically active, as well as those that are constantly using DR, the study aimed to determine what role does PA play in DR and how it relates to achieving family homeostasis, i.e. cohesion, flexibility and communication. The goal was achieved by answering three operational questions: What regulation strategies do such families use? What is the relation between PA and DR? And what perceived effects do families achieve through such DR? Given the very specific population studied, it was expected to establish distinctive relationships between PA and DR and their positive effects on homeostasis.

Methods

Design

To meet the objectives, a study was conducted with Polish families engaged in regular (at least once a week) and sustained (for at least a year) PA involving all cohabiting family members, along with the implementation of shared or differentiated digital technology regulation practices involving all family members. All digital devices and the infrastructure that determines their essential functions, such as the Internet, were recognized as digital technologies (). PA spanned a broad spectrum, ranging from paraprofessional to amateur to functional activities; considering joint and separate activities (). Both families who were physically active before the implementation of DR and those for whom PA was a newfound alternative were studied.

Demographically diverse families were studied, including variations in family type (child and childless; two-parent or single-parent families); number, age and gender of children; age and educational level of adults; work type; place of residence; and economic status. To triangulate the data, it was collected using in-depth dyadic and individual semi-structured interviews, supplemented by an interviewer filling out a questionnaire about each family member.

Participants

The study included 30 Polish families. Data on 86 members of the studied families were collected and analyzed. The age of adults ranged from 24 to 60, with a median age of 35. Children living with their parents ranged from 0 to 22 years, with a median age of 8.2 years. Adults represented all 16 Polish provinces. The sample was also differentiated by five demographic criteria ().

Table 1. Number of children.

Table 2. Adults’ level of education.

Table 3. Place of residence.

Table 4. Adults’ occupation.

Table 5. Self-assessment of the economic situation.

Instruments and data collection procedures

Firstly, a database of 79 Polish families meeting the baseline conditions, i.e. using DR in the family and engaging in regular PA, was created. The database was created using the snowball method, involving five interviewers from different regions of Poland. Families were recruited in a manner that ensured diversity in terms of numerous demographic criteria and willingness to take part in the study. In a situation of difficulty in reaching potential respondents who met some criteria, a search for families in local Facebook groups was resorted to. The specifics of DR and PA were clearly defined for each family in the database. On this basis, 30 families were selected. The selection was based on an algorithm to create a sample that was as diverse as possible, without omitting variation in any demographic criterion. This was followed by a pilot study and after that 27 interviews with dyads (adults, i.e. pairs of parents or single parents with adult children) and 3 individual interviews (with single parents of minor children). Twenty-eight families were compensated for the interviews,Footnote1 and five respondents waived compensation.Footnote2

Each interview began with the interviewer filling out a form for each family member, including demographic data and quantitative and qualitative data on DR and PA. The interview participants were then asked 13 open-ended questions about the origins of DR in the family; the course of regulation; the methods used and an assessment of their effectiveness; the importance of PA; the impact of the practices used on relationships in the family; and the family’s plans in this regard. Due to the ongoing official epidemic emergency in Poland interviews were conducted remotely via Microsoft Teams between December 2022 and January 2023. Interviews lasted from 42 to 121 min, averaging 69 min. The interviews were professionally transcribed verbatim and then analyzed.

Modes of analysis

All the data were thematically analyzed through two cycles of coding. Abductive, i.e. systematic combining of deductive and inductive approaches was applied (Dubois & Gadde, Citation2002). In the first case, provisional coding (Miles, Huberman and Saldaña, Citation2014) and deductive, concept-driven approach (DeCuir-Gunby et al., Citation2010; Schreier, Citation2012) was applied. The list of codes came from an analysis of the existing literature on digital disconnection, PA and family life, as well as everyday knowledge, logic and an interview guide (DeCuir-Gunby et al., Citation2010; Schreier, Citation2012) and was an outgrowth of the major categories arising from the research question posed: (1) motivations for undertaking DR in the family; (2) methods, techniques, tools and strategies of regulation of each family member; (3) obstacles and limitations in DR; (4) specifics of PA of each family member; (5) perceived relationships between DR and PA; (6) the role of DR and PA for relationships in the family; (7) other individual and family effects from the regulation; (8) anticipated future of the family in terms of DR and PA. The category system was checked and revised after working with 40% of the material.

Then theoretical coding (Miles, Huberman and Saldana, 2014) and indictive, data-driven approach (DeCuir-Gunby et al., Citation2010; Schreier, Citation2012) was adopted for each of the original 8 categories to determine the subcategories, i.e. the dominant patterns of activities and opinions on cohesion, flexibility and communication. This category system was also checked and revised after working with 40% of the material. In this way, three types of motivation; seven types of DR; and specific features of DR, including the roles played in it by PA, were specified. This ultimately made it possible to interpretate data and determine if and how, through DR using PA, the family maintains the conditions of homeostasis.

Results

Firstly, the three motives as well as seven types of DR will be characterized. This elaboration will enable at the discussion stage to determine the importance of DR for homeostasis in the family, especially achieving flexibility and communication. Then the internal peculiarities of technology regulation in families will be defined with a focus on PA which has a special role in achieving cohesion and communication, as will be also explained in the discussion stage.

Perceived motives for regulation

The reason for this reduction in technology was that we didn’t know how to get along with each other, and we simply found that we didn’t spend enough time with each other; that we didn’t talk to each other honestly enough; that we just didn’t look at each other, and so on. And we found that (…) we had to put down the technologies and start being ourselves and start living with each other. (Family no. 15)

There are three main motives for introducing digital technology regulation in families, and they relate to time, stressors and relationships, respectively.

Time motives were one of the key reasons for the regulation. The turning point was the realization of the amount of time consumed by online activities at the expense of others. This is well illustrated by one respondent calling technologies ‘time-wasters’ and ‘digital bullshit’. Technologies were seen as sources of unproductivity when time could be used for the betterment of the individual or the whole family. It was a matter of focusing on things that are important for family relationships, health and personal development.

The second group was stress motives. Families wanted to eliminate physical and mental stressors. In the first case, it was decided to counteract or reduce fatigue caused by screen technologies, such as sleep problems, headaches and eye and back pain. On the other hand, the elimination of mental stress was due to feelings of overstimulation of one’s own or children’s lives, including observed hyperactivity. Respondents mentioned also content stress, for example, due to contact with content that evoked negative feelings. In adults, these were mainly frustration in the case of television and news content and a sense of participation in ‘false reality’ in the case of social media content.

The third group related to family relationship motives:

We came up with it ourselves. One day we just sat down and talked about the fact that we can’t be in front of the TV, in front of the phone all the time. That not only do we have to demand this from the children, but also from ourselves (…). And we found that it’s not a big deal not to use the phone while on a walk. We can focus on ourselves. (Family no. 26)

Types of regulation

There is a marked difference in the methods, tools and techniques adults use with themselves and with children (). There are six main types of regulation: temporal, spatial, content-based, occasional, device-based and functional.

Temporal regulations involved placing time limits on devices, platforms or Internet access. For adults, constant monitoring of screen time reported by screen devices and changing phone modes were important, especially at the beginning of DR. The limits for children were based mainly on their age and parents’ subjective decisions about the proper limit. Generally, the younger the children, the more restrictive the rules were.

[…] these apps that show how much time we spend in front of these phones, […] let’s say, to motivate us. In the sense that we saw how much of that time we were spending. It scared us a little bit. As a result, we decided to limit it a bit. (Family no. 2)

Spatial regulations applied to places inside and outside the home where technology was generally not used, such as in the bedroom, at the table or in the woods. One mother’s strategy illustrates this well:

I don’t go into the bedroom with a phone at all. If I answer the phone or want to write something or read a message, for example, I sit at the desk. So that the children can see that I treat the phone as a job, and always this phone lies at the desk. (…) I don’t walk around the apartment - I don’t go to the toilet with the phone, or to the kitchen. (Family no. 9)

[During a tourist trip] we leave the phones. Let them be on fire, let them be on the move. We are busy with ourselves (…), we take care of the conversation - we take care of something important. (Family no. 12)

Specifics of digital regulation practices

The organic nature of the practices is something that respondents strongly emphasized. One term used by a participant to capture this was ‘methods–non-methods’, denoting rules that aligned with the family’s values and norms that are simple, easy to implement, not burdensome to maintain, and as flexible as possible to changing conditions. Sometimes they were the spontaneous result of self-organized compromises, but often the result of discussions and agreements.

I think if it was just one person doing it that way, it would make less sense than when we decided to do it together. (…) It made it easier for us […]. I can’t imagine that, for example, one of us made a decision that he/she limits [TV], that he/she doesn’t watch TV, and the other person would watch [TV]… (Family no. 2)

Families were aware that there were many solutions, and one could observe the freedom to use and change them on a ‘Swedish table’ basis, as one respondent put it. These methods were family-friendly, intended to unite the family and bring its members closer together. Therefore, it was quite common to encounter statements that only regulating the whole family makes sense and that such regulation is much easier to apply as is implementing the principle of ‘small steps’, starting with small modifications of habits and rules and moving on to more comprehensive, though still flexible, solutions.

We wanted some activity to do together so that it would also somehow strengthen us, unite us. Well, running is hard for me… I tried to overcome, but I decided to change it to cycling. Thanks to this JózefFootnote3 can accompany me. We can go out for training together. He runs, I bike. We are together, we are happy (…). We spend time outdoors, healthy, active, still together. (Family no. 12)

Families believed that it was impossible to disconnect from technology completely, as well as being aware that technology provides many benefits in terms of education, security and work flexibility. Nevertheless, the regulations introduced were to focus attention either on other family members or on oneself, as intended: ‘We wanted to spend more time with each other than with our phones’. (Family no. 1). Perhaps that’s why only a single respondent claimed to use self-tracking technologies; additionally, only being alone.

The general assumption in families was that DR is necessary, making it important to introduce and maintain rules and thus find alternative activities. These included playing board games, reading books, doing art, cooking together and, most importantly, engaging in PA.

‘[…] We immediately found a substitute for that. Instead of that phone in the evening before bed, well, a book came into play. Then, instead of sitting in front of that TV, we started just going out to the gym or jogging. I mean, it just turned into doing sports more often’. (Family no. 2)

The importance of physical activity in digital regulation

The forms, degrees and extents of PA varied significantly among the families studied: from paraprofessional sports, in which an adult trained for competitions, to amateur participation in various sports, to regular yet intensive walks, or regular functional activity—that is, deliberately incorporating movement into other activities, such as commuting. The time of year significantly determined the possibilities for PA, changing the forms of movement from outdoor activities in the spring and summer to indoor activities in the autumn and winter, often decreasing in intensity.

Regardless of the type of PA, there were several reasons why it was the best alternative for activities reliant on technology. The first seems to be the most mundane: sport is a technology blocker. In most cases, while playing sports, it is impossible to use technology, or at least in a way that is typical of media use at rest. Often the hands are busy, and if not, using the device is difficult or even dangerous. In team sports, on the other hand, the need for constant contact with others eliminates the use of technology.

Sport is a good disconnection starter. According to the respondents taking up sports to reduce media, it helped initially, especially when the regulation rules were just being initiated, because it easily provided an attractive replacement activity and produced quick, visible results. Achievements, even small ones, were a source of satisfaction and motivated further action. It was also an effective tool for DR by those who played sports before they started limitation. They often extended sports activities or diversified them.

There was such satisfaction that if we did it once, why not a second time, not a third? (…) We saw health progress and began to get along better (…). Somehow, we were happier, so much happier to speak to each other, and the phone didn’t burble or glow. (Family no. 17)

Sport gives a return on time investment. Respondents believed that the greater the involvement in sports, the easier it was to regulate technology. This was due to several factors: filling a significant amount of time with PA (thus limiting time for technology) and the ability to derive satisfaction, gratification and pleasure. Sports taught self-discipline, which strengthened with regular activity. The ability to self-restrain and overcome one’s weaknesses was easier when sports were played.

Sport is a bonder. Joint family activities, like long walks, cycling, hiking, skiing and more () resulted in better communication and gave a sense of greater closeness and bonding, which motivated families to continue such activities. In addition, PA made it easy to organize time together. Over time, the sports routine ‘drew them in’, as the respondent said, enough that they were reluctant to discontinue it: ‘Nothing gives as much fan and pleasure as a trip together on bicycles or going to the mountains’. (Family no. 29)

Sports are highly engaging. Both adults and children have their attention fully absorbed by the activity and do not seek contact with technology. According to respondents, sports provide satisfaction offering an opportunity for fun and social integration; and they can also become a passion, a source of personal achievement or freedom:

Sport gives us more than technology. Because of technology we are kind of unvolunteers. Sport gives us freedom, freedom in what we do (…). Physical activity is not replaceable by anything in my opinion. (Family no. 26)

Sometimes it’s hard to go out like this (…). You watch something on TV. It’s nice. Nice, and all of a sudden we’re going for a walk. Well, not everyone always wants to, but once we make that decision - and that’s what’s cool - we never regret it. And that’s something what makes us remember to limit that time just on the Internet or with technology. (Family no. 1)

Perceived effects of digital regulation through physical activity

PA was a two-kind regulation method in the families studied. In the first case, it was a kind of post-catalyst. Sport was chosen to replace technological activity upon realizing its excess. In the second case it was a kind of a pre-catalyst. Sports were present in the family constantly and for a long time, and thus simplified and reinforced the implementation of DR. The effects of disconnection in regularly physically active families were difficult to separate from the effects of PA. Families saw apparent connections between one and the other and evaluate the obtained effects holistically and comprehensively:

Now we can quiet down. We can talk to each other more. Before, we were arguing and writing messages to each other - we couldn’t talk to each other. And now, in spite of everything, we go for a walk and talk to each other (…) We have this time for one another and it’s so good. (Family no. 9)

The collective effects were twofold. On the one hand, there were the effects of the individuals’ regular PA, in which regulating a person’s emotional state through physical exertion consequently positively affects the atmosphere at home. On the other hand, there were the effects of joint PA. Through this, families gained balance, releasing negative emotions and generating positive ones.

Families gained the most from PA carried out together and it was dominating. There was mutual support and encouragement. Families built traditions based on healthy lifestyles. In the studied cohort, shared walks were almost ritualistic in importance. Regular, lengthy walks mainly facilitated conversations, thereby helping resolve problems, deepen relationships, and build bonds: ‘Such a walk looks like this in total the whole thing is made up of conversation’. (Family no. 19)

As families chose more difficult or risky sports activities, they also observed trust building and learning the principles of cooperation. They described this time as enjoying being together, feeling a real interest in each other, and learning and appreciating each other. It was a time to build relationships in the present and bonds for the future. Many parents hoped the shared sports experience, like sports picnics, rallies and trips would be a source of future memories and family traditions. It was also of great importance to accompany the PA of other family members, cheering, supporting, sometimes competing. Therefore, joint PA can be described as an essential family unifier.

Similarities and differences among families studied

The cohort selected according to very demanding conditions regarding frequency and seniority in terms of DR and PA showed numerous similarities and very few differences, which are nuanced in nature. Despite great diversity in terms of family structure and demographic characteristics, the families show a very high degree of consistency in terms of attitudes toward DR and PA, as well as the relationship between the two spheres. Firstly, they are families with a high awareness of the importance of both DR and PA to the individual and the family as a whole. Secondly, they are characterized by a high sense of responsibility for themselves and others in the family. Thirdly, they are families for whom family values such as relationships, a sense of community, bonding and emotional closeness are a priority. It is worth noting that for some families the high awareness also applies to other spheres of life, such as dietetics, taking care of physical and mental health, psychology, especially emotions, and parenting, which in some families adds up to a consistent picture of a consciously chosen lifestyle.

This results in many similarities in the adoption and implementation of DR strategies through PA. These are strategies adopted collectively, through discussion and mutual conversation and negotiation, even with young children. They were inspired by adults, but discussed and implemented by all. Conflicts were reported sporadically and were described as insignificant and short-lived. They involved few families with teenagers. The relatively harmonious implementation of strategies in such specific families may be due to the ‘natural’ approach to DR and PA, i.e. the presence of both strands in families from the very beginning, or from just after the child/children arrived; possibly after the realization of over-usage of technology and the start of a completely new lifestyle that has become permanent.

What prevails in families were low-cost, easy-to-implement PAs and simple, flexible and family-specific DR strategies. The former primarily included walking together, while the latter included time and space regulations. This causes economic differences to be of little relevance to the issue under study. It could only be noted that some better-off respondents also benefited from more expensive forms of exercise and could afford an exercise room at home or a personal trainer. However, these were exceptions.

Few differences were observed according to other demographic characteristics. The importance of DR in families without children was primarily due to the care of the partners’ relationship and a sense of shared responsibility for it. In families with children, there were additionally a sense of responsibility for children development and mutual relations in the further future.

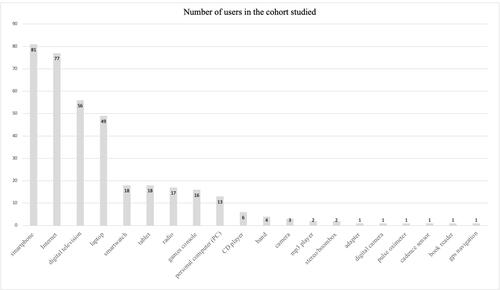

In the studied cohort, smartphones were the dominant technology (81 out of 86 respondents used them) and they were primarily affected by restrictions; television was second (56), and laptops were third (49). Television restrictions mainly affected children (as do game consoles); while laptops (as well as PCs) mainly affected white-collar workers.

Families living in rural areas showed less variety in forms of PA due to the unavailability of infrastructure and organized activities, but on the other hand, they were characterized by close contact with nature and the opportunity to be outdoors more often due to the proximity of the garden or forest, as well as an increase in functional PA.

Small differences due to age could be noted. Older people chose simple and non-exercise forms of movement, and DR serves to calm them down and take their minds off reality. Younger people, including those with children, also chose more challenging sports, and DR also served to improve communication within the family, building relationships and bonds. For the elderly, DR was somewhat more natural and easier; for younger adults, especially with children, it sometimes became a challenge.

The importance of education level lends itself to the origin of the idea of implementing PA and DR. In the case of those with higher education, it happened to be the result of formal education, informal self-education, as well as observing one’s own and others’ lives and learning from that. In the case of those with lower education, a common-sense approach could be observed, relying on patterns from the past (older people in the family), as well as their own observations.

Gender differences primarily related to perceptions of the importance of DR. Women, especially mothers, saw family integration and bonding goals; while men, mainly fathers, saw individual gains for family members, e.g. health, social development. Mothers were also more flexible when it comes to changing DR strategies, and they were responsible for it more often than fathers, whose responsibility was mainly to ensure the implementation of PA.

Discussion

By integrating three domains into a singular study, namely, the significance of media within the familial context, the digital disconnection experienced by media users, and the importance of PA within family life, this research not only updated previous findings, but also provided novel insights regarding the homeostasis of the familial system.

According to Olson (2000), the cohesion within a family encompasses various factors such as emotional connectedness, shared temporal and spatial dimensions, common interests and recreational activities. The families examined in this study indicated that reducing the reliance on technology through the expansion of PA aids in achieving this cohesion. PA has the potential to unite family members, foster close relationships and cultivate a sense of community. Moreover, it facilitates the creation of shared quality time and the formation of lasting memories. Simultaneously, the strategies implemented in this context are centered around the family unit. Families establish patterns of DR and PA that align with their overall system of norms, values and expectations. Furthermore, cohesion is fostered through the implementation of technological constraints and the active participation of all family members, thereby preventing any disruptions or inefficiencies.

Reducing technology results in the transformation of passive time into active time, thereby serving as a mechanism for fostering familial connections. The allocation of this time toward joint or shared PAs strengthens the positive outcomes. Subsequently, these outcomes lead to tangible advantages, encompassing relational aspects as well as physical and psychological well-being, thereby further consolidating the adopted approach. Families highly appreciate the intimacy and authenticity (Enli & Syvertsen, Citation2021; Syvertsen, Citation2020) within their relationships.

Driven by the pursuit of efficient time utilization (Baym et al., Citation2020; Nguyen et al., Citation2022) and the inclination to engage in activities perceived as more valuable, families establish patterns of DR and PA that align with their overarching set of expectations. Simultaneously, these practices and outcomes foster cohesiveness within the family unit. They constitute one of the processes of the ongoing emergence of the family as a whole, constantly shaping its self-regulated system (Coyne et al., Citation2014).

The respondents placed greater emphasis on general values such as spending quality time together and cultivating a strong and lasting bond for the future, as opposed to immediate satisfaction derived from using media technologies or the comfort felt from physical inactivity. PA served to reinforce the consequences of DR, while simultaneously providing the impetus to continue with such disconnection. Whether PA was a constant presence within the family dynamics prior to the catalyst effect (pre-catalyst) or emerged as a result of increased awareness and a deliberate decision to disconnect from digital technologies thereafter (post-catalyst), it served as a motivating factor in facilitating regulation.

According to Olson (Citation2000), flexibility in the family refers, among other things, to relationship rules, the implementation of changes, including negotiation styles, leadership, control and discipline (Olson, Citation2000). On the one hand, the families studied maintained their flexibility in the face of external influences through continuous, smooth and dynamic adaptation to changing conditions, i.e. technological constraints. On the other hand, they achieved this flexibly internally by establishing regulatory strategies and PAs that naturally fit into the family’s dispositions, habits and norms. In both child and childless families in the cohort studied, DR and PA were most often adopted and negotiated together and invariably included everyone. Depending on the age of the family members, rules were established in a balance between partnership and discipline, ensuring efficiency and freedom of choice.

The study confirmed that PAs are tailored to the gender, age and interests of not only children (Thompson et al., Citation2010), but also adults. In addition, PAs must be tailored to the abilities and dispositions of all family members. Activities that work best are simple and inexpensive (Thompson et al., Citation2010), but most importantly, they are a natural fit for the family. In contrast to early studies (Dagkas & Quarmby, Citation2012), financial aspects did not play a role. Free activities such as walking or cycling were most often chosen. Furthermore, demographic differences, including whether or not to have children, age, place of residence or level of education, were not importantly distinguishing factors between the families studied.

According to Olson (Citation2000), communication in the family requires, among other things, creating opportunities for members to express themselves, openness and respect (Olson, 2020). It creates a prerequisite for cohesion and flexibility. The families studied knew about the importance of family, joint, integrative activities that create conditions for uninterrupted communication. Therefore, community PAs have not been uncommon or viewed as unrealistic (Thompson et al., Citation2010), but are particularly desirable and frequently implemented. By ‘freeing’ the hands of family members, they created conditions for uninterrupted communication that binds the family together. The families studied were well connected and characterized by closeness, support and accessibility (Padilla-Walker et al., Citation2012). DR created a better environment for communication and interaction. When this time was dedicated to shared PA, the positive effects increased. These in turn lead to concrete advantages that further consolidate the chosen strategy.

DR and PA have created new habits, routines and family traditions that hold the family together, strengthen unity in the present and create bonds for the future. Certainly, families acknowledged the multitude of benefits offered by digital technology and made use of its perks, such as enhancing quality time spent together. However, they rate this time as less significant, both from their individual perspective and especially from the perspective of family relationships.

Conclusion

This study adds value to understanding the relationship between DR and PA within a family context. Examining the DR of physically active families determined how these two spheres interact and how they rank in the more complex family system. The key empirical finding of the research is the identification of three primary reasons why families engage in regulation. Additionally, the study categorizes regulation into six different types and examines its specific attributes within families who prioritize physical activities over screen-based activities. The distinct features of regulation include being inherent to the family dynamic, promoting family well-being, directing attention and incorporating alternative pursuits. On the contrast, PA demonstrated its superiority over screen activities as it empowered individuals to self-motivate, endure and witness satisfaction in various aspects of life. PA not only enhanced time management and overall well-being, but it especially fostered better communication within families and increased feelings of connectivity.

The key theoretical contribution of the research is that families aim for homeostasis in the face of technostress and an overwhelming sense of technology by decreasing media use in favor of PA, which promotes coherence, flexibility and communication. In the first case, when screen time is limited, it strengthens family bonds, and engaging in PA further enhances this, resulting in a greater overall impact. In the second scenario, the family adjusts to external factors by being adaptable and consistent, establishing effective guidelines and approaches, while still upholding a partnership form of self-control. In the third circumstance, prioritizing communication during shared PAs or when accompanying others, rather than relying on technology, directly leads to fulfilling family interactions.

In terms of the limitations of this research, it is important to mention that the families involved in the study had a strong understanding of the significance of DR and PA. The participants believed that while technology can be substituted, movement cannot. Families with less awareness of DR may have approached and assessed these behaviors differently. Additionally, the declaration of a pandemic emergency restricted the possibility of conducting face-to-face interviews, which may have influenced the progression of the interviews.

The research was carried out on a small group of people from a particular population. The data was collected in a country where DR and PA are not common. Further research should include different populations and larger groups of people and should test the statistical significance of PA in relation to DR. Additionally, one limitation of the research was that only families who were engaged in DR and PA were studied. This raises the question of what other non-digital activities support families in reducing their use of technology. Another question relates to the extent of DR within families, their expectations, and how they can be supported in effectively regulating digital use.

The study highlights that given the contradictory results of various digital disconnection studies, highly contextualized research focused on specific cohorts is crucial for understanding the conditions contributing to the effectiveness associated with digital disconnection. It allowed us to know the conditions of motives, strategies and effects to understand how digital detox can not only enhance awareness but also alter behaviors (Moe & Madsen, Citation2021), leading to the implementation of tailored ‘digital well-being interventions’ (Nguyen, Citation2021).

Both digital disconnection and PA are elements of a complex contemporary lifestyle (Macdonald et al., Citation2004) of conscious families, who, wanting to live mindful and healthy lives, care about the individual well-being of members and ‘relatedness satisfaction’ (Fasoli, Citation2021). Regulating their media as well as PA and inactivity is part of a fairly consistent active and sport-related lifestyle (Hayoz et al., Citation2019; Shropshire & Carroll, Citation1997), within which maintaining a balance between connection and unplugging is essential (Sas, Citation2019). The postulate of developing norms of digital media use is also worth mentioning (Nguyen et al., Citation2022). However, this should be implemented in conjunction with establishing general family systems and a thorough understanding of their complex practical applications. A broader scale and deeper understanding could lead to a comprehensive and multifaceted normative reflection on the digital disconnection of contemporary users and, based on this, the design of interventions to support families (Kopecka-Piech et al., Citation2023).

Ethical approval

The study did not require approval from an institutional ethics committee. The study was remote and did not involve any risky interventions. All the subjects have provided appropriate informed consent. The instructions contained all the necessary information about the purpose, scope and use of the data, emphasizing the voluntary, anonymous and withdrawable nature of the consent at each stage of the study.

Data accessibility statement

The data underlying this article are available on Zenodo, at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8007244; https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8007340; https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8007081; https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8006974.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the interviewers who worked on data collection: Patrycja Cheba, Martyna Dudziak-Kisio, Roksana Gloc, Joanna Kukier, Mateusz Sobiech for their commitment and Jakub Nowak for his valuable guidance during the manuscript writing stage.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Katarzyna Kopecka-Piech

Katarzyna Kopecka-Piech is a Doctor of Humanities and Doctor Habilitus of Social Science, working as an Associate Professor at Maria Curie-Skłodowska University in Lublin, Poland. She specializes in research on new media technologies, and mediatization of everyday life. Previously, she was a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Oslo, Norway, and at the Södertörn University, Sweden, as well as a research assistant at the University of Oxford, United Kingdom. She is the author of ‘Mediatization of Physical Activity: Media Saturation and Technologies’, Rowman & Littlefield: Lexington Books, 2019 and ‘Media Convergence Strategies. Polish Examples’, Astrum, 2011; an editor of several books, including ‘COVID-19 Pandemic as a Challenge for Media and Communication Studies’ Routledge 2022; ‘Mediatization of Emotional Life’, Routledge 2022; ‘Contemporary Challenges in Mediatization Research’ Routledge 2023 and the author of more than few dozens of articles and book chapters. The presented article is the result of the implementation of the grant received by her from the National Science Centre, ‘Disconnect to reconnect. The role of physical activity in family digital detox – preliminary research’, no. 2022/06/X/HS6/00121.

Notes

1 In the amount of PLN 320 gross for the family.

2 These families rated their economic situation as very good or average; they were resigning to avoid the paperwork.

3 The names of quoted respondents have been deliberately changed.

References

- Baumer, E. P. S., Adams, P., Khovanskaya, V. D., Liao, T. C., Smith, M. E., Sosik, V. S., & Williams, K. (2013). Limiting, leaving, and (re)lapsing: An exploration of Facebook non-use practices and experiences. In CHI’13: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1–20).

- Baumer, E. P. S., Guha, S., Quan, E., Mimno, D., & Gay, G. K. (2015). Missing photos, suffering withdrawal, or finding freedom? How experiences of social media non-use influence the likelihood of reversion. Social Media and Society, 1(2), 2056305115614851.

- Baym, N. K., Wagman, K. B., & Persaud, C. J. (2020). Mindfully scrolling: Rethinking Facebook after time deactivated. Social Media and Society, 6(2): 2056305120919105.

- Bigaj, M., Woynarowska, M., Ciesiołkiewicz, K., Klimowicz, M., & Panczyk, M. (2023, May 25). Higiena cyfrowa dorosłych użytkowniczek i użytkowników internetu w Polsce. Warsaw. https://cyfroweobywatelstwo.pl/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/Ogolnopolskie-Badanie-Higieny-Cyfrowej-2022_Raport.pdf

- Blum-Ross, A., & Livingstone, S. (2018). The trouble with ‘screen time’ rules. In G. Mascheroni, C. Ponte, & A. Jorge (Eds.), Digital parenting. The challenges for families in the digital age (pp. 179–187). Nordicom. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1535910/FULLTEXT01.pdf

- Bowen, M. (1993). Family therapy in clinical practice. Jason Aronson.

- Bozan, V., & Treré, E. (2023). When digital inequalities meet digital disconnection: Studying the material conditions of disconnection in rural Turkey. Convergence, 135485652311745. https://doi.org/10.1177/13548565231174596

- Brzęk, A., Strauss, M., Przybylek, B., Dworrak, T., Dworrak, B., & Leischik, R. (2018). How does the activity level of the parents influence their children’s activity? The contemporary life in a world ruled by electronic devices. Archives of Medical Science: AMS, 14(1), 190–198. https://doi.org/10.5114/aoms.2018.72242

- de Barbaro, B. (ed.) (1999). Wprowadzenie do Systemowego Rozumienia Rodziny. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego.

- Cierpka, A. (2003). Systemowe rozumienie funkcjonowania rodziny. In A. Jurkowski (Eds.), Z zagadnień współczesnej psychologii wychowawczej (pp. 107–129). Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN.

- Clark, L. S. (2011). Parental mediation theory for the digital age. Communication Theory, 21(4), 323–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2011.01391.x

- Cox, M. J., & Paley, B. (1997). Families as system. Annual Review of Psychology, 48(1), 243–267. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.48.1.243

- Coyne, S. M., Padilla-Walker, L. M., Fraser, A. M., Fellows, K., & Day, R. D. (2014). ‘Media Time = Family Time’: Positive media use in families with adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 29(5), 663–688. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558414538316

- Dagkas, S., & Quarmby, T. (2012). Young people’s embodiment of physical activity: The role of the ‘pedagogized’ family. Sociology of Sport Journal, 29(2), 210–226. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.29.2.210

- DeCuir-Gunby, J. T., Marshall, P. L., & McCulloch, A. W. (2010). Developing and using a codebook for the analysis of interview data: An example from a professional development research project. Field Methods, 23(2), 136–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X10388468

- Dubois, A., & Gadde, L.-E. (2002). Journal of Business Research, 55(7), 553–560.

- Eichen, L., Hackl‐Wimmer, S., Eglmaier, M. T. W., Lackner, H. K., Paechter, M., Rettenbacher, K., Rominger, C., & Walter‐Laager, C. (2021). Families’ digital media use: Intentions, rules and activities. British Journal of Educational Technology, 52(6), 2162–2177. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13161

- Elias, N., & Sulkin, I. (2019). Screen-assisted parenting: The relationship between toddlers’ screen time and parents’ use of media as a parenting tool. Journal of Family Issues, 40(18), 2801–2822. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X19864983

- Enli, G., & Syvertsen, T. (2021). Disconnect to reconnect! Selfhelp to regain an authentic sense of space through digital detoxing. In Disentangling: The geographies of digital disconnection (pp. 227–252). Oxford University Press.

- Fasoli, M. (2021). The overuse of digital technologies: Human weaknesses, design strategies and ethical concerns. Philosophy & Technology, 34(4), 1409–1427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13347-021-00463-6

- Felmlee, D. H., & Greenberg, D. F. (1999). A dynamic systems model of dyadic interaction. The Journal of Mathematical Sociology, 23(3), 155–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/0022250X.1999.9990218

- Fish, A. (2017). Technology retreats and the politics of social media. tripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique. Open Access Journal for a Global Sustainable Information Society, 15(1), 355–369. https://doi.org/10.31269/triplec.v15i1.807

- Fotheringham, M. J., Wonnacott, R. L., & Owen, N. (2000). Computer use and physical inactivity in young adults: Public health perils and potentials of new information technologies. Annals of Behavioral Medicine: a Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 22(4), 269–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02895662

- Gangneux, J. (2021). Tactical agency? Young people’s (dis)engagement with WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 27(2), 458–471. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856520918987

- Ganito, C. S., & Jorge, A. (2017). On and off: Digital practices of connecting and disconnecting across the life course. Paper presented at AoIR 2017: The 18th Annual Conference of the Association of Internet Researchers. Tartu, Estonia: AoIR. http://spir.aoir.org.

- Gingold, J. A., Simon, A. E., & Schoendorf, K. C. (2014). Excess screen time in US children: Association with family rules and alternative activities. Clinical Pediatrics, 53(1), 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922813498152

- Golish, T. D. (2003). Stepfamily communication strengths: Understanding the ties that bind. Human Communication Research, 29(1), 41–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/hcr/29.1.41

- Hayoz, C., Klostermann, C., Schmid, J., Schlesinger, T., & Nagel, S. (2019). Intergenerational transfer of a sports-related lifestyle within the family. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 54(2), 182–198. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690217702525

- Hertlein, K. M. (2012). Digital dwelling: Technology in couple and family relationships. Family Relations, 61(3), 374–387. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2012.00702.x

- Hiniker, A., Schoenebeck, S. Y., & Kientz, J. A. (2016, February 27). Not at the dinner table: Parents’ and children’s perspectives on family technology rules. In Proceedings of the ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, CSCW (pp. 1376–1389). Association for Computing Machinery.

- Jordan, A. B. (2012). A family systems approach to the use of the VCR in the home. In Social and cultural aspects of VCR use. In D. Julia (Ed.), Social and cultural aspects of VCR use. Routledge.

- Jordan, A. B., Hersey, J. C., McDivitt, J. A., & Heitzler, C. D. (2006). Reducing children’s television-viewing time: A qualitative study of parents and their children. Pediatrics, 118(5), e1303–e1310. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-0732

- Jorge, A., Agai, M., Dias, P., & Martinho, L. C.-V. (2023). Growing out of overconnection: The process of dis/connecting among Norwegian and Portuguese teenagers. New Media & Society, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448231159308

- Kim, G., Jeong, H., & Yim, H. W. (2023). Associations between digital media use and lack of moderate intensity physical exercise among middle school adolescents in Korea. Epidemiology and Health, 45, e2023012. https://doi.org/10.4178/epih.e2023012

- Knoester, C., & Randolph, T. (2019). Father-child sports participation and outdoor activities: Patterns and implications for health and father-child relationships. Sociology of Sport Journal, 36(4), 322–329. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2018-0071

- Kopecka-Piech, K. (2019). Mediatization of physical activity: Media saturation and technologies. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Kopecka-Piech, K. (2022). Family digital well-being: The prospect of implementing media technology management strategies in Polish homes. Media-Biznes-Kultura. Dziennikarstwo i komunikacja społeczna, 1(12), 71–84.

- Kopecka-Piech, K., Burno-Kaliszuk, K., & Teichert, J. (2023). Supporting parents in acquiring (self) regulatory competence in the use of media technologies by family members: The case of programmes, projects and activities applied in Poland. In International perspectives on parenting support and parental participation in children and family services (pp. 103–118). Routledge.

- Kuntsman, A., & Miyake, E. (2019). The paradox and continuum of digital disengagement: denaturalising digital sociality and technological connectivity. Media, Culture & Society, 41(6), 901–913. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443719853732

- Listyarini, A. E., Alim, A., Oktaviani, A. D., Putro, K. H., Kristiyanto, A., Margono, A., & Pratama, K. W. (2021). The relations of using digital media and physical activity with the physical fitness of 4th and 5th grade primary school students. Physical Education Theory and Methodology, 21(3), 281–287. https://doi.org/10.17309/tmfv.2021.3.12

- Livingstone, S., & Helsper, E. J. (2008). Parental mediation of children’s internet use. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 52(4), 581–599. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838150802437396

- Macdonald, D., Rodger, S., Ziviani, J., Jenkins, D., Batch, J., & Jones, J. (2004). Physical activity as a dimension of family life for lower primary school children. Sport, Education and Society, 9(3), 307–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573320412331302412

- Mannell, R. C., Kaczynski, A. T., & Aronson, R. M. (2005). Adolescent participation and flow in physically active leisure and electronic media activities: Testing the displacement hypothesis. Loisir Et Societe, 28(2), 653–675. https://doi.org/10.1080/07053436.2005.10707700

- Matthes, J., Thomas, M. F., Stevic, A., & Schmuck, D. (2021). Fighting over smartphones? Parents’ excessive smartphone use, lack of control over children’s use, and conflict. Computers in Human Behavior, 116, 106618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106618

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Miller, D., & Madianou, M. (2012). Should you accept a friends request from your mother? And other filipino dilemmas. International Review of Social Research, 2(1), 9–28. https://doi.org/10.1515/irsr-2012-0002

- Moe, H., & Madsen, O. J. (2021). Understanding digital disconnection beyond media studies. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 27(6), 1584–1598. https://doi.org/10.1177/13548565211048969

- Neustaedter, C., Harrison, S., & Sellen, A. (2013). Connecting families. Springer.

- Nguyen, M. H. (2021). Managing social media use in an “always-on” society: Exploring digital wellbeing strategies that people use to disconnect. Mass Communication and Society, 24(6), 795–817. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.2021.1979045

- Nguyen, M. H., Büchi, M., & Geber, S. (2022). Everyday disconnection experiences: Exploring people’s understanding of digital well-being and management of digital media use. New Media & Society, 14614448221105428. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221105428

- Olson, D. H. (2000). Circumplex model of marital and family systems. Journal of Family Therapy, 22(2), 144–167. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6427.00144

- Padilla-Walker, L. M., Coyne, S. M., & Fraser, A. M. (2012). Getting a high-speed family connection: associations between family media use and family connection. Family Relations, 61(3), 426–440. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2012.00710.x

- Paus-Hasebrink, I., Kulterer, J., & Sinner, P. (2019). The interplay between family and media as socialisation contexts: Parents’ mediation practices. In Transforming communication (pp. 157–170). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Radtke, T., Apel, T., Schenkel, K., Keller, J., & von Lindern, E. (2022). Digital detox: An effective solution in the smartphone era? A systematic literature review. Mobile Media and Communication, 10(2), 190–215. https://doi.org/10.1177/20501579211028647

- Rambo, A., & Hibel, J. (2012). What is family therapy?: Underlying premises. In Family therapy review: Contrasting contemporary models (pp. 3–8). Routledge.

- Ribak, R., & Rosenthal, M. (2015). Smartphone resistance as media ambivalence. First Monday, 20(11). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v20i11.6307

- Salanova, M., Llorens, S., & Ventura, M. (2014). Technostress: The dark side of technologies. In Korunka, C. & P. Hoonakker, (Eds.), The Impact of ICT on Quality of Working Life. Springer.

- Sanders, W., Parent, J., Forehand, R., & Breslend, N. L. (2016). The roles of general and technology-related parenting in managing youth screen time. Journal of Family Psychology: JFP: journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43), 30(5), 641–646. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000175

- Sas, C. (2019, May 4). Millennials: Digitally connected never unplugged? In 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems.

- Schreier, M. (2012). Qualitative content analysis in practice. SAGE.

- Shropshire, J., & Carroll, B. (1997). Family variables and children’s physical activity: Influence of parental exercise and socio-economic status. Sport, Education and Society, 2(1), 95–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/1357332970020106

- Şirin Güler, M., & Çakır, E. (2020). Analysis of the relationship between digital game playing motivation and physical activity. African Educational Research Journal, 8(1), 9–16.

- Steinfeld, N. (2021). Parental mediation of adolescent Internet use: Combining strategies to promote awareness, autonomy and self-regulation in preparing youth for life on the web. Education and Information Technologies, 26(2), 1897–1920. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10342-w

- Sutton, T. (2017). Disconnect to reconnect: The food/technology metaphor in digital detoxing. First Monday, 22(6). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v22i6.7561

- Syvertsen, T. (2020). Digital detox: The politics of disconnecting. Emerald Group Publishing.

- Thompson, J. L., Jago, R., Brockman, R., Cartwright, K., Page, A. S., & Fox, K. R. (2010). Physically active families - de-bunking the myth? A qualitative study of family participation in physical activity. Child: care, Health and Development, 36(2), 265–274. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.01051.x

- Treré, E. (2021). Intensification, discovery and abandonment: Unearthing global ecologies of dis/connection in pandemic times. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 27(6), 1663–1677. https://doi.org/10.1177/13548565211036804

- Veldhuis, L., van Grieken, A., Renders, C. M., Hirasing, R. A., & Raat, H. (2014). Parenting style, the home environment, and screen time of 5-year-old children; the ‘be active, eat right’ study. PLoS ONE, 9(2), e88486. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0088486

- Widdicks, K., Ringenson, T., Pargman, D., Kuppusamy, V., & Lago, P. (2018, May). Undesigning the Internet: An exploratory study of reducing everyday Internet connectivity. In ICT4S (pp. 384–397).

- Woodstock, L. (2014). Media resistance: Opportunities for practice theory and new media research. International Journal of Communication, 8, 19. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/2415/1186

- Xu, H., Wen, L. M., & Rissel, C. (2015). Associations of parental influences with physical activity and screen time among young children: A systematic review. Journal of Obesity, 2015, 546923–546925. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/546925

- Zach, S., & Lissitsa, S. (2016). Internet use and leisure time physical activity of adults—A nationwide survey. Computers in Human Behavior, 60, 483–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.02.077

Appendix

Table A1. Forms of PA declared by members of the families studied.

Table A2. Types of digital technology regulation declared by members of the families studied.