Abstract

First published in 1970, The 70s Bi-weekly (hereafter, The 70s) stands out from many other independent magazines in Hong Kong around the same time by its unique ‘action-oriented-ness’. More than a printed magazine whose contents blend radical political theories, social activism, and avant-garde art, the ‘action-oriented’ feature of The 70s is seen in both of its political and cultural actions. This article places The 70s in the context of the production and screening of experimental films in Hong Kong at the time, and discusses two (experimental) films made by the magazine’s editorial board in the 1970s. They are a documentary (1971) that records the ‘Defend Diaoyu Islands’ protests on April 10th of the same year in Hong Kong and an experimental film To the Arty Youths of Hong Kong (1978), imbued with political metaphors and critical sarcasm. Extending Charles Tilly’s (Citation2008) discussion on the repertoire of contentious politics to the cultural dimension, I argue that these films constitute one of their diverse repertoires of social activism. The transformation of the cinematic style from realism to postmodern collage also illustrates a vital shift of the media performativity in their repertoire of dissent.

REVIEWING EDITOR:

Introduction

This article focuses on The 70’s Biweekly 70 年代雙週刊 (hereafter, The 70s), an independent youth magazine published in the 1970s in Hong Kong and its film-related practices in screening and filmmaking. The emergence of The 70s and the alternative cultural scene have to be examined in the print culture of Hong Kong from the 1960s to the 1970s. Owing to its special geopolitical location, Hong Kong during this period was caught in various power struggles in two kinds of Cold War: the macro-Cold War between the Soviet/China and US camps and the micro-Cold War between the Communist and the Nationalist Party (Roberts & Carroll, Citation2016). Despite being a British colony, Hong Kong’s cultural ecology has been influenced by political forces from all sides. On the rightist side, the United States saw Hong Kong (along with Taiwan) as the last bastion of defence against the spread of communism to discrete diaspora Chinese communities in Southeast Asia and elsewhere. As Law Wing-sang notes, ‘American dollars came pouring into East Asia in support of academic, educational, and other cultural activities that might possibly impede the growth of radical ideologies ‘ (Law 2009, p. 133). The U.S.-supported ‘Greenback’ (i.e. US dollars) cultural programs, including cultural magazines (World Today), publishing houses (Union Press, or You Lian) and their school textbooks, newspapers (The Chinese Student Weekly and College Life), and even educational institutions (e.g. Chuang Kin College) dominated the cultural life of Hong Kong’s youth (Lin Citation2008, Fu Citation2019). Influenced by the ‘micro-Cold War’, many of these publications and cultural programs were edited by intellectuals who were in exile in Hong Kong from the mainland after the Civil War. Some of them, whether or not they were staunchly pro-KMT, were generally anti-communist in an explicit or implicit way (Law 2009, Fu Citation2019, Zhao Citation2017). On the leftist side, the influence from Communist China was also manifested in the print culture, especially in the newspapers. Two of the most important newspapers, Wen Wei Po and Ta Kung Pao, were founded by mainlanders migrated to Hong Kong. These two newspapers represented the voice of the Communist Chinese government, in particular during the 1966 and 1967 riots’, while in general their reports focused more on the local working class issues in Hong Kong (Cheung Citation2009, Leung Citation2020).

Against this background, according to Wu Xuan-ren (1998, p. 218), The 70s was first regarded as a magazine of the ‘New Left’, which differentiates it from, first, the mainstream Left as defined by the Chinese Communist Party, and second, the anti-Communist Greenback- or KMT-sponsored youth publications. It was a journal of ‘youth radicalism’ with a strong color of anarchism. In the context of Hong Kong, anarchism may not necessarily mean the push for of the total abolition of the state, but rather, a resistance to injustices imposed by any authorities, be they British colonialism, imperialism, Chinese communism or the mass media. The 70s was first published on January 1st, 1970. The bi-lingual (Chinese and English) magazine stands out from many other independent journals at that time with its wide coverage of topics, including political reviews, avant-garde art and photography, world and Hong Kong literature, popular and classical music, independent films from home and aboard. The key figure of the magazine is Ng Chung-yin (吳仲賢1946–1994), a social activist best known for his organization of protests against the Chu Hai College’s manipulation of the student union when he was studying there in 1969. The protests, now known as ‘Chu Hai Incident’, initiated new waves of student movements in the 1970s in Hong Kong and became a prelude to the founding of The 70s as a media base for forming a discourse of youth social movements at that time. Another founding member, Mok Chiu-yu (莫昭如 1947–), is a local student activist who returned to participate in Hong Kong’s social movements in the late 1960s after he finished his studies in Australia. Mok is widely recognized as the first generation of Hong Kong anarchists and a key figure in Hong Kong theatre.

Ng’s own summary of the commonalities of student revolutions around the world well illustrates some of the most key concerns of The 70s, namely, first, their anti-institution and anti-bureaucracy stance; second, their advocacy of a new life style that is expressed through art and culture; third, their concerns for the Third World and anti-colonialism/neo-colonialism; fourth, their criticisms of university education that breeds only elitism (Wu, Citation1998, pp. 153–157). More importantly, the magazine was an advocate of direct actions such as street protests, and autonomous, bottom-up self-organizations of individuals and groups.

These characteristics of the magazine made it uniquely fashionable, bold, and radical compared to the mainstream (both leftist and rightist) magazines. This is probably also the reason why it is difficult for researchers to integrate it into a singular historical narrative, be it the Cold War, the left-right dichotomy or the study of the nationalism-based anti-colonial movement. So far, studies of youth magazines in Hong Kong in the 1960s and 1970s have focused mainly on the more clearly defined groups of leftist or rightist publications while studies of The 70s have been rare. Law Wing-sang’s studies of the ‘Chinese as an official language’ movement and the left-wing radicalism in the 1970s make fleeting references to the position of The 70s in a broad picture without delving into its content and modus operandi (Law Citation2015, Citation2017). In his Master’s thesis completed in 2016, Chan Tsz Him compared literary texts published in four Hong Kong’s youth journals, namely, Pangu, Wenxue yu meishu, Wenmei yuekan and The 70s during the ‘fiery years’. Chan focuses on the literary production in The 70s, especially the poems with bold erotic descriptions, as a way to explore its entanglement with internationalism, its identification with China and its anti-colonialism and anti-establishment sentiments. Lau Kin-wah’s (Citation2019) M. Phil. thesis ‘A Preliminary Exploration into the Political Visual Production of Hong Kong Cultural Magazines at the Turn of the 60s and 70s’ captures a very important aspect of The 70s, namely, its visual design, that makes it stand out from other youth magazines of the same period. The 70s’ use of a great deal of visual material from different sources, such as Western pictorial magazines and underground magazines, as well as popular culture periodicals such as Life, Chinese revolutionary prints, Asian avant-garde art and design, successfully stimulated the reader’s alternative imagination of the connections between local, Chinese and world politics. In the main, however, Lau takes a comparative approach in examining the magazine, juxtaposing it with other youth magazines during the same period. In my recently edited book, The 70s Biweekly: Social Activism and Alternative Cultural Production in 1970s Hong Kong (2023), I elaborate on the visual design strategies employed by the magazine’s print version. In the same volume, Tom Cunliffe and Emilie Choi Sin-yi provide a detailed analysis of the magazine’s film criticism and the cinematic practices of its editors and related peers, particularly exploring the relationship between the Cold War and cine clubs in Hong Kong. My current study overlaps with Choi’s discussion on the political implications of two films produced by the members of The 70s, but I focus on analyzing these films through the lens of the aesthetics of cinematic experimentality and the political tactics of the magazine’s members.

Hong Kong film studies, especially those that are related to the history of Hong Kong experimental, independent, and documentary film studies, have yet to look closely at these films through the lens of their intricate relationship with independent youth magazines and social movements at that time. Very limited space has been given to the study of historical narratives of Hong Kong experimental or independent films in the 1960s and 1970s, which, incidentally, is repetitive in content, consisting for the most part of lists of directors involved in the production of the experimental short films and the names of their works (Cheung Citation2010, pp. 313–314, Fung Citation2001, p. 5, Chang & Chow, Citation2011, p. 29), or a brief interview on the shooting and the original intention of the filmmakers (Chang & Chow, Citation2011, pp. 30–34). In his memoir-like essays, Law Kar (Lau Yiu Kuen 劉耀權 1940–), a well-known Hong Kong film critic and one of the first filmmakers in Hong Kong to start practicing experimental filmmaking in the late 1960s, details his and other filmmakers’ works and participation in the film festivals (Law Kar Citation2012, Citation2017 and Citation2018). His articles are a valuable first-hand historical source, but they discuss neither the film texts nor their social background at great length.

This article scrutinizes two (experimental) films made by the magazine’s editorial board in the 1970s. They are a documentary (1971) that records the ‘Defend Diaoyu Islands’ protests on Apr. 10th, 1971 in Hong Kong and an experimental film To the Arty Youths of Hong Kong (1978), imbued with political metaphors and critical sarcasm towards British colonialism and the arty youths of the time. I propose that these films were, in Charles Tilly’s terms, repertoires of contentious performances invented by The 70s. Performance and repertoire are two theatrical metaphors used by Tilly to describe ways of organization of and participation in collective social actions. In his Contentious Performances (2008), Tilly defines performances in politics as ‘“learned and historically grounded” ways of making claims on other people’ (Tilly Citation2008, pp. 4–5). To trace the changes of these claim-making performances in the history of contentious politics such as social movements, protests, strikes, revolutions or even coups, Tilly focuses on the performers’ ‘repertoires’ and the dynamics between different forms of contention. (Tarrow Citation2008, p. 236) Like jazz players in a jam, the contentious ‘actors’ in contentious politics also choose their repertories and decide ‘which pieces they will perform here and now [and] in what order’, for they also have more than one kind of repertoires at their command. (Tilly Citation2008, p. 14)

In this vein, this paper wishes to make the point that, as an ‘action-oriented’ magazine, The 70s offered a new strategic model of youth social activism in Hong Kong in the 1970s. This model mixes print culture (both textual and graphic) with direct action (both political and cultural) as repertoires in their powerfully contentious performances. Although other contemporaneous youth magazines such as College Life also organized film reviews and film shooting or screenings, they did not utilize such a variety of performative repertoires as The 70s and in such a political manner. The study of this model is crucial to our understanding of the strategic innovations (and development) of the youth movement in Hong Kong in the 1970s. This paper therefore treats the visual practices of The 70s magazine as an equally important part as the print content of the magazine, rather than as a derivative, a representation or as an action to be examined in isolation. Unlike other early Hong Kong experimental films (Mok Citation1980a, p. 25), which aimed at stylistic experimentation and were eventually subsumed by the film industry, as political acts in themselves, the experimental films of The 70s were more direct and bold in their attacks on the colonial government, imperialism and police brutality. The two films I am going to talk about in the article are the very few existing independent documentary films available today that capture the social and economic situation in Hong Kong in the first half of the 1970s. I think this phenomenon is worth noting, not only because it shows that there is no causal relation between radical social movements and their visual documentation in moving images, but also because it reflects that at that time, Hong Kong society’s perception of the relationship between politics and images was constructed through a certain kind of ‘absence’. This absence of visual documentation of the 1970s social and student movements contributed to the huge void in collective memory and consciousness of social injustice at that time.

Meanwhile, this paper will raise questions about the filmmaker-centred historical writing of Hong Kong independent film studies. Filmmaking, screenings, and post-screening discussions were all part of the action repertoires for members of The 70s. Thus, The 70s’ cinematic practices must be read both from the inside (texts) and the outside (activism and screening). This article observes the transformation of cinematic styles—a variation in their repertoire—the magazine’s editors used in relation to social activism. In the early 1970s, they adopted a documentary style that served as a witness to a historical event; in the late 1970s, the members of The 70s ventured a more playful and experimental piece full of self-irony and self-deprecation. While the former blends images of the news documentary, experimental film and private video, the latter emphasizes more sound and visual techniques, magazine prints, symbols and narration as a piece of filmic essay, or a ‘cinematic political manifesto’. I will also trace the efforts that Mok, who was involved in both films, and other members of the filming team put in the screening of the film To the Arty Youths of Hong Kong at home and abroad and the difficulties they encountered in the process. Made by ‘amateur’ filmmakers, both works can be seen as innovative contentious repertoires of social activism per se and their different styles have created different possibilities of radicalizing the audience, albeit with their own limitations. This paper therefore attempts to blur the line between film as a medium of action and action itself, and to fill the gap in the in-depth analysis of Hong Kong experimental and independent film texts of the 1960s and 1970s.

The 70s and Hong Kong experimental cinema in the 1960s and 1970s

According to Mok Chiu Yu (Citation1980a, p. 24), the encounter between The 70s and experimental cinema started with a film screening in late 1970. The initial contact point was ‘Amateur Film Exhibition 70’ 實驗電影展70 organized by College Cine Club (CCC) 大影會 in City Hall. CCC was a film appreciation group formed under the magazine College Life 大學生活published by Union Press.Footnote1 The Club held screenings, competitions and film festivals to promote local amateur filmmaking since 1967 (Law Kar Citation2017, pp. 1–35). Law Kar, who would become one of the most important film critics in Hong Kong, and a group of writers and readers of The Chinese Student Weekly 中國學生週報 (hereafter The Weekly) formed the core team of the group. Some of the Club members, including Law Kar himself, soon began to make 8 mm and 16 mm experimental pieces (Law Kar Citation2009, p. 3). The 70s was not closely related to CCC and its events. However, without being credited, The 70s actually sponsored ‘Amateur Film Exhibition 70’ held in September 1970 (Mok Citation1980a, p. 24). Mok (Citation1980a, p. 24) said it was through this exhibition that he began to realize that there was a group of young intellectuals in Hong Kong who were making experimental films.

Although The Weekly and College Life are both US-funded ‘greenback publications’, we cannot simply equate the position of the magazines with that of the people who published their writings in them. When Hong Kong’s experimental film culture was emerging in the late 1960s and 1970s, there were very limited public cultural venues and resources available to young people in Hong Kong. Thus, the connection between Law Kar/CCC and The 70s– as in Law Kar’s submitting his writings to the magazine for publication, his participation in magazine’s film projects as well as the magazine’s support of CCC’s film screenings - cannot be described as a collaboration ‘greenback culture’ and ‘New Left’. The rise of non-professional filmmaking coincided with a series of changes in the technical scene, the media environment and society at large. Hong Kong’s social unrests in 1966 and 1967 exerted a strong political impact on young intellectuals and students in the colony. Law Kar admitted in a recent interview that after the 1967 Riots, while many peers of his age began to search for new life goals and possibilities by engaging in social activism and anti-establishment educational and labour practices, he was in a relatively disoriented state of mind. Living an unstable life and seeing no clear way out, he hoped to engage in both art and social practices. (Lin Citation2018, p. 54; Wu Citation2017) After years of writing film reviews, he found that the film media would open a new sensory possibility of engagement both artistically and socially.

In this vein, I try to define the 1970s experimental cinema in Hong Kong as follows: a group of independent short films shot on 8 mm or 16 mm film by cinephiles with no or limited professional training in filmmaking. These films were not marketable, and their ‘experimentality’ largely lies in their obscurity of meaning, mixed use of camera language and lack of dramatic tension. They were, however, an important means of self-expression and peer discussion for young people who had access to amateur film equipment at the time. However, I suggest that the experimental films of the 1960s and 1970s in Hong Kong can indeed be subdivided into two types: those that are relatively more experimental in form, and those that are more bold and direct in their political expression. In Issue 13 of The 70s (1970, pp. 8–9), Law Kar’s article ‘From Amateur Film to New Film: An Outlook of the Future of Hong Kong Cinema’ juxtaposes the decadent commercial film industry and the emergence of non-commercial, and amateur, experimental or underground filmmaking among young people in CCC and other amateur cine clubs. I think experimental films under Law Kar’s definition, including those in Amateur Film Exhibition 70, as well as his own film Routine 全線 (1969), John Woo’s Death Knot 死結(1969) and Xixi’s The Milky Way (1969), all fall into the first category. Those related to The 70s, such as the documentary on Defend Diaoyu Island protests in 1971, and Turbulent 1974 動蕩的1974, a short film about the anti-price increase campaign 反加價運動 by Hou Man-wan 侯萬雲 (1947–), who was also an editorial board member of The 70s, fall into the second category.Footnote2 Yet, the filmmakers of the two categories overlapped, which again proves that, as mentioned above, the group of experimental filmmakers of the 1960s and 1970s cannot be simply divided by the political orientation of the magazines in which they usually published their articles, but were more like a group of young people experimenting together with a new medium.

After the brief blossoming of experimental cinema in Hong Kong in the early 1970s, many ‘amateur filmmakers’ who were making experimental, non-commercial short films began to enter the television industry. Parallel to the short-lived emergence of experimental film in Hong Kong, a series of Hong Kong New Wave films were created by a group of TV producers and directors who made use of the equipment and the other resources of television stations and the commercial film industry. Although many of the representative films of this Hong Kong New Wave Cinema were highly experimental and individualistic, they were still mainly feature-length films, which are fundamentally different from the earlier experimental short films. Meanwhile, the editors of The 70s seemed to be trying to continue the experimental trend through their relatively amateurish production. According to Mok’s (Citation1980b, p. 32) own statement, one of the reasons for making a new film was to respond to the decline of this trend.

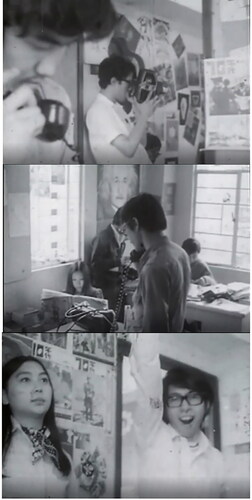

Hong Kong Defends Diaoyu Islands Protest (1971)

As an important player in Hong Kong’s Defend Diaoyu Islands Movement (DDIM), a series of protests that were mainly organized by overseas ethnic Chinese youths in reaction to the disputes over the island’s sovereignty between Japan and China, The 70s (in particular Ng and Mok) was actively involved in several protests in 1971. Hong Kong Defends Diaoyu Islands Protest (hereafter, Diaoyu Islands) can be seen as a valuable cinematic witness to the political activism at that time. The film follows a straightforward line of narration with a chronological documentation of five consecutive days of the DDIM protests at The Japan Society of Hong Kong in the Central District before, on and after April 10, 1971. Directed and filmed by Law Kar and Chiu Tak Hut, and probably shot with the 16 mm Bell & Howell that Law Kar obtained from Taiwan, the film captures the faces, slogans and cityscapes of Hong Kong’s youth in the early 1970s. Days before the demonstration, The 70s editorial team raised money for the publicity of the demonstration and allocated HK$750 to buy film for Law Kar and Chiu to make a documentary of the protest. The film also clearly shows a close relation between the protests and The 70s. The 15-minute long silent film started with the young people busy preparing for the protests in The 70s editorial office. In a small office room walled with big posters of Einstein, Che Guevara and The 70s’ own magazine covers, they are seen making phone calls, painting protest placards and slogans and being interviewed by RTV (Rediffusion TV). Noticing the camera’s eye on him, Mok even raises his clenched right fist in excitement (). The shooting team then came to the streets in various parts of the city. On a crowded street in Causeway Bay, two young men (one of them was Mok’s younger brother) are seen distributing protest leaflets to bus riders and pedestrians who hurry by. Many take the leaflets out of curiosity, but their faces show confusion and indifference. The young activists are also seen explaining their protest to two Caucasian passers-by.

Figure 1. Preparing for ‘Defend Diaoyu Islands’ protests in The 70s office, Hong Kong Defends Diaoyu Islands Protest (1971), Dir. by Law Kar and Chiu Tak Hut. Courtesy of Mok Chiu Yu.

In the next episode, apparently on the day of the protest, Law Kar and Chiu came to the site of the rally around the Japanese Cultural Center with hand-held cameras. Protesters with placards proclaiming to defend Diaoyu Islands or calling for downfall of Japanese Imperialism are seen everywhere; shouting students mingling with crowds of bystanders while excited journalists and police officers standing in a line. The crowd soon begins to stir and both the protesters and policemen become more agitated. It is uncertain if the photographer deliberately spun the camera or if the confusion of the scene made it impossible for him to hold onto the camera, but the picture on the screen also began to twirl, adding to the perception of chaos at the scene. Young people are then arrested, their arms twisted behind their back; a girl with her arms raised walks alone through a street lined with people; the camera also sweeps past the giant movie poster outside the theater (). The crowd gradually calms down but does not disperse. In Mok’s writing (Citation1980a, pp. 24–25), he thinks that Law Kar and Chiu were obviously a bit flustered when the police arrested and beat up the protesters, and the camera got shaken. As a result, on the screen, the protest is tension-ridden but the violent scenes are blurred and sparse.

Figure 2. The protest scenes, Hong Kong Defends Diaoyu Islands Protest (1971). Courtesy of Mok Chiu Yu.

Then, we see Mok give a speech, surrounded by a group of young audience in the nearby Statue Square. Shortly, people are walking towards the Central Police Station, probably looking for ways to get the arrested demonstrators out. Police officers and demonstrators negotiate across the metal grate set up at the entrance of the police station. The next scene takes the viewers to Caritas Center, where student groups and activist groups gather around a table for a press conference. A portrait of Sun Yat-sen hangs on the wall of the room. In the middle of the table is a slogan ‘Defend Diaoyu Islands to the Death’ written on a piece of paper. The last scene shows what has taken place two days later, when protestors gather in Central Court in support of their arrested peers. The camera observes the young people, male and female, standing and chatting on the staircase. Ng Chung-yin is seen going up and down the steps in agitated spirit.

The film can be said to be a mix of private records, journalistic documentations, and experimental cinematography. At moments, for example, when the arrests on the street are shown in freeze-frame, one is reminded of the pensive collages of Godard’s Cinétracts (1968), which consist only of still images from street protests during 1968’s May Movement in Paris. Similarly, in Law Kar and Chiu’s film, still images are used to stress the moments of shock at police violence and the determination of the protesters. Yet these moments are fleeting and unlike Godard’s ambivalent treatment of the images, Law Kar and Chiu’s documentation is obviously more conservative in its use of cinematic language, which shows more efforts in being faithful in the depiction of reality than in the contemplation of how revolutionary film as a medium of documentation may speak to the reality. In Law Kar’s previous experimental films, such as Routine (1969), which was shot from a window of a moving taxi on his way to work, actuality of the cityscape as a kind of post-riot landscape was noteworthy for the major (lack of) technique used. In this film, the protest on Hong Kong streets, the preparation for it and the aftermath were likewise presented and represented in a temporal routine, but unlike Routine, whose political message is ambiguous, if not a hindsight reading, this film recognizes the interdependence between the way of the protest and the art of filmmaking.

Diaoyu Islands was also treated in a relatively personal manner, with intertitles written by Law Kar indicating the venue, date and action. Interestingly, some Chinese characters in the intertitles are written in the Cultural Revolutionary Style double-simplified Chinese, which is more simplified than simplified Chinese as a form of extreme democratization of Chinese writing system that can be received by all classes of struggling mass. The hand-written intertitles renders the film as a personal visual diary of the protest and, as in Godard’s film, ‘offer[s] a critically alternative source of ‘news’ or information in contrast to the commercially offered mediums available’. (Elshaw Citation2000, p. 48) We may also see the film as an organizing tool of plans of actions and the narrative through its spatial shifts. The film’s emphasis on The 70s and its members not only illustrates the magazine’s central role in the action but also the relation between the filmmakers and the activists.

Undoubtedly, as a new technology, hand-held camera available to amateur/half-professional or independent filmmakers became a catalyst not only for the invention of new styles and content of moving images but also for the forms of activism per se. Meanwhile, however, it also allows more space of manipulation. The film was often loaned free of charge to student unions and other organizations at Hong Kong’s universities and post-secondary institutions for screening. Since it was a silent film, on several occasions the students themselves tried to pair the footage with a tape recording that contains discussions on the student movement when they showed the film. On one or two occasions, Hong Kong’s pro-Beijing ‘Nationalist’ (Guocui pai) students used the film to promote the arguments of the ‘Gang of Four’ by dubbing their own narrative. Mok was infuriated that the dubbing distorted their original intention but admitted that this also made him well realize that film is a combination of sight and sound, the change of either of which would change the intent of the film.Footnote3

To the Arty Youths of Hong Kong (1978)

After Diaoyu Islands, The 70s shelved the repertoire of shooting films and began to focus on organizing public screenings of arthouse films from the West and Japan, with a clear emphasis on left-wing cinema, which, with their political messages, were critical of social reality. In 1974, Mok and his peers established a cine club named ‘Dwarf Film Club’, whose screening line-up contained not only western auteurs such as Bernardo Bertolucci and Godard but also films from the Third Cinema including Indian director Satyajit Ray and Cuban filmmaker Tomas Guiterrez and experimental shorts (Yeung Citation2019, p. 77). Their passion of making their own film was reignited when Mok and Lee Cheng 李正, another member of The 70s, saw a poster calling for submission for a local independent film festival in late 1978. They then decided to make a film, through which they didn’t only hope to express themselves, but also, more importantly to engage in discussions with other ‘arty youths’ in Hong Kong. This was the origin of the 15-minute short film To the Arty Youths of Hong Kong (hereafter, Arty Youths), which was mainly produced by Mok, Lee and Chan Kit-ching and Tom. Completed around the same time as the first issue of the relaunched The 70s magazine after around a four-year hiatus, the film seems to be not only a declarative summation of The 70s’ previous attempts, but also a preview of a new beginning. Through their own film, Mok and his friends attempted to critique Hong Kong’s ‘Arty Youths’ for not being aware of the insidiousness of the television industry as a tool of consumerism, capitalism and colonial governance but even aspiring to join its ranks. Not only does the film mock the ‘Arty Youths’, but it also expresses suspicion of the various cultural and artistic institutions and activities that emerged under the auspices of the Hong Kong colonial government in the mid-to-late 1970s. They were, in Mok’s (Citation1980b, p. 32) opinion, used by the colonialists as a means to ‘seduce and numb the people’. In addition, continuing the function of The 70s as an alternative media, the film also urges the audience to reflect on their own passive, receptive position. In an article in a 1980 City Entertainment Magazine, Mok says: ‘Films in general only reinforce human passivity, whereas a truly free society can only be made up of millions of autonomous and active individuals. Brecht, the Situationists, and Godard were all intent on eliminating the passivity of the “spectator”’ (Mok Citation1980b, p. 32).

Compared to Diaoyu Islands with its strong documentary style, Arty Youths adopts a more experimental approach in two main ways. First, the film consciously emphasizes its interactive relationship with the audience, using dialogue and lots of colloquial narration to break the feeling of alienation of the audience outside of the film. Starting with the handwritten credits, the film sets an ‘epistolary’ tone that speaks directly to the audience. The film opens with an appearance of Mok as a tour guide around the cultural venues around the city. He first comes to the City Hall, where he immediately begins to talk about Henry Moore’s sculptures in the lobby. He then sits down with Chan in an empty concert hall. (As a No. 8 Gale or Storm Signal was in force on the day, the City Hall was actually not open to the public. The filming team got in with the help of a friend who worked there.) From the City Hall, Mok moves on to the Café do Brazil in the Ocean Terminal in Tsim Sha Tsui, while Mok the narrator introduces the audience to the café as a haunt for Hong Kong’s Arty Youths. The tone is self-deprecatory and derisive (). At the end of the segment, Mok mumbles through a discussion on experimental filmmaking in Hong Kong and offers an explanation of why the film is shot in 35 mm and not 8 mm or 16 mm, both of which were too ‘childish’ for artistic youth. Mok and his group then take a taxi to Commercial Television (CTV) Station, which had just closed down two days earlier. We hear the narrator says:

Figure 3. Mok and friends in Café do Brazil, To Arty Youths in Hong Kong (1978), Dir. by Lee Cheng, Mok Chiu Yu, Chan Kit-chin and Tom. Courtesy of Mok Chiu Yu.

Why was the Commercial TV station not occupied? When the intellectual youths did not act… why have the TV workers not thought of the fact that they should be their own masters? The failure of the 1968 [French] revolution can be attributed to the fact the revolutionary masses did not think of occupying the TV stations and using them to propagate and agitate. At the end, De Gaulle and the ruling class were able to control the TV and suppressed the revolution.

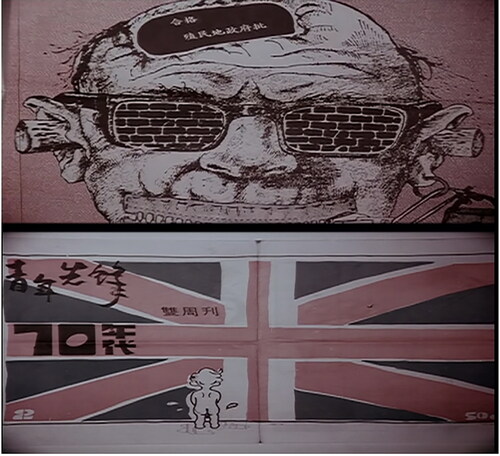

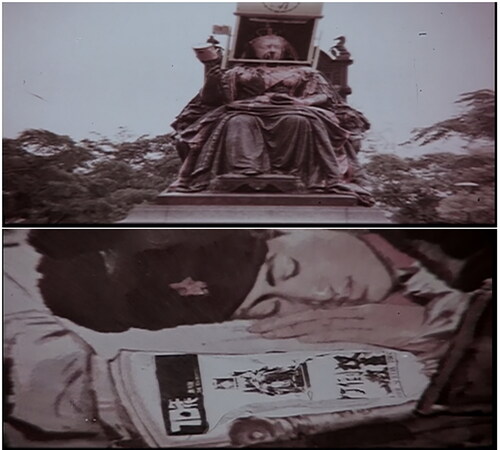

Second, the overall aesthetic experiment of the film is built on non-narrative, non-linear, extensive repetitive editing, and a disordered collage of images and sound. The film employs a large number of close-ups of still images to create a visual impact of vertigo. These images include posters of headshots of Che Guevara and Bakunin, and of the French Revolution and stills from the film Z, news photos of demonstrations against the fare-raise of Star Ferry, Mao Zedong’s quotations, photos of demonstrations in the Chinese revolutions, and commercial advertisements such as those of Coca-Cola. The cover images of The 70s are also a major component of these close-ups, connecting the magazine’s print medium closely with its film. In addition to old magazine covers such as the photo of My Lai Village Massacre, two new magazine covers, one showing the vandalized Queen Victoria Statue with red paint splashed over it and a trash bin put over her head and the other featuring a cartoon satirizing colonial education, also appear more than once in the film. The cover image of The 70s Youth Avant Guard, which features a boy urinating in front of the British flag, is also included (). These covers are arguably the most radical and audaciously offensive images towards the British colonial rule in Hong Kong magazines of the period. Interestingly, some of the images have been humorously reworked for the film. When the camera pans to the cover of an issue of Pan Gu, a pro-Communist China magazine, with ink drawings of some PLA soldiers, one can see that the cover of a book under the head of a sleeping soldier turns out to be the cover of the issue of The 70s with the vandalized statue of the Queen ().

Figure 5. The Vandalized Queen and The Sleeping Solider, To Arty Youths in Hong Kong (1978). Courtesy of Mok Chiu Yu.

In addition to images, the narration text is also diverse. The first kind of text is Mok’s monologue to the audience, which is very colloquial and casual. The second is the voices of other Hong Kong youths. One of them is the sound track of an interview with the social activist Su Yau-sai Paul 蘇守忠 (1941–), the instigator of the Star Ferry anti-fare-increase protest in 1966, who also appeared in one of Law Kar’s experimental films, Beggar (1970). In the interview, Su reflects on what was gained or lost during the anti-fare-increase protest. The other voice is from a young man named Wong Hung Yuen who was studying in the UK. In the film, Wong reads from a letter, in which he asks his friends in Hong Kong to write to him more often to alleviate the feelings of loneliness, pain and alienation he feels in the UK. The third kind of text consists of political commentaries and analyses by the filmmakers of the film. One of the most important passages is a commentary on the function and significance of the film itself, which essentially explains the purpose of making the film as follows:

We believe that there is no such a thing as a revolutionary film. There is only revolutionary use of films…in capitalist Hong Kong. The audience are all passive consumers. Even if the film carries the theme of socialist revolution, the spectators are still confined to their passivity. If we think that the genuine socialist revolution is to be made by millions and millions of autonomous and self-managed individuals, films never have played a revolutionary role as almost all films require only the passivity of the audience. Films should have a positive effect on the audience who would claw out from their passivity and begin to criticize the reality of society.

The last type of narrative text is made up of quotations are from various luminaries, which includes Mao, Bakunin and Che Guevara. The interweaving of these four types of texts may seem chaotic, but they produce an overall unified and coherent message, one that mocks, if not resists, the smooth, logical, narratively seamless and pleasing commercial language. They are interwoven with recurring, sometimes fragmented images presented as negatives to form a letter to Hong Kong’s arty youths.

In a conversation I had with Mok, he mentioned why documentaries are not the best way for him to get his point across. The main reason is that he was very concerned about the subject’s participation in the narrative of the documentary. In other words, if the filmmaker completely excludes the opinions or ideas of his subjects from the editing process, it is worth reflecting on a certain privilege that the filmmaker enjoys. This particular concern on the equality of the narrator and the narrated makes Mok feel that the film is still creating a hierarchy between the viewer and the production, even as it mediates between them. Thus, when we see a film such as Arty Youths, we cannot simply assume that the filmmakers feel that they have complete trust in the medium. There is a difference between the attitude of the editorial board of The 70s towards filming and the ‘storytellers’ who have always used film as the sole medium of artistic expression. For Mok and his team, shooting the film was one of their attempts to find a tool to break down a certain visual order that was under the dual monopoly of colonialism and capitalism. The same attempts can be found in their other repertoires of actions: publishing The 70s, running independent bookstores, engaging in social activism, or organizing screenings of films. It is the relationship between the film and the audience, between the filmmaker and the subject, between the filmmaker and the film, and the emotional potentials and mobilizing power that reside in those relationships that Mok and his friends are most concerned with.

Screening Arty Youths

If film is to serve such a function, then the most important thing is that it can be shown to and seen by the audience. However, the screening of Arty Youths ran into many difficulties. In Hong Kong, the film festival to which they submitted the film offered only a few screenings in the City Hall and in preview rooms. The total number of audience added to no more than a thousand. (Mok Citation1980b, p. 33) Originally, Mok and Lee intended to use the film as a starting point for the discussions with former experimental filmmakers such as Law Kar, Kam Ping Hing and Patrick Tam, on the future of experimental film and commercialization of film. All of them, out of Mok’s expectations, were jury members for the festival. Their position made the discussion different from what Mok anticipated. On the commercial front, Mok Yuen Hei, who had worked with The 70s on art-house film screenings, promised Mok that if their film passed the censorship of the Office for Film, Newspaper and Article Administration, it would be shown as a ‘companion screening’ to Woody Allen’s film at the Kyoto Theatre. However, Pierre Lebrun, the chief prosecutor of the Office, wrote to Mok, informing him that the film was banned and could never be shown in any theatre, though permission could be considered for screenings sponsored by private clubs (Mok Citation1980c, p. 41). That the film was banned was most likely due to the recurring disrespectful cover images of the Queen’s statue and the Union Jack. With the expectation that the film would be shown on the big screen, Mok shot the film on 35 mm films, which was more expensive than on 16 mm films, but Mok’s original plan was not realized and the film would not be seen again on the big screen in Hong Kong for a long time.

Meanwhile, Mok also took the film to screen in Europe. Again, due to the limited accessibility to the 35 mm projection equipment, the film did not reach a wide audience. In 1979, Mok screened the film twice in Italy, once in England, and once in France (Mok, Citation1980b, p. 37). There were other reasons why the film didn’t make much of a splash in Europe. With no English subtitles, the film’s Cantonese narration made no sense to European audiences. Only in the last five minutes, when John Lennon’s ‘Imagine’ was played, the audience seemed to breathe a sigh of relief. Lacking an understanding of the rich narration of the first ten minutes, as well as an adequate knowledge of Hong Kong’s political and cultural context, European audiences didn’t have many questions concerning the film in the post-screening discussions. The film may have been quite experimental in Hong Kong, but its radicalness did not resonate with the European audiences. Instead, their questions revolved largely around issues such as the revolutions in mainland China. The ‘revolutionary status quo’ of a capitalist city like Hong Kong was neither unfamiliar nor urgent to them.

From Mok’s description, the trip to Europe did not have the desired effect: their film did not interest young Europeans, and the same problems of screening and distribution that they encountered in Hong Kong plagued them in Europe as well. Mok has not written with much more on this. Yet it seems to me that there was something self-contradictory in the attempt of Mok and his group to find some kind of ‘internationalist’ alliance and ‘market’ in the West right from the beginning: their posture was anti-Western colonial hegemony, but they were at the same time seeking recognition from the West. Hong Kong’s marginal position in the world revolution also caught them in an awkward place: while they were considered by their European friends as a group of people who could help them explore and explain the Chinese question in depth, as residents of a British colony, they only had limited access to China and their perspective to China remained peripheral. Moreover, their understanding of China was mixed with ambivalent feelings because of the particular position of the Chinese in Hong Kong. As a result, the arty youths from Hong Kong somewhat failed to convey their revolution passion to establish this internationalist solidarity with their European comrades through their film.

Conclusion

Like producing and screening films, organizing and encouraging youth participation in social movements, mobilizing the active participation of the audience and problematizing the hierarchical relationship between audience and filmmaker are all aims of The 70s’ performances. The encounter between The 70s and experimental cinema, and the subsequent parting of the ways of the two, reveals the existence of two possibilities of experimental cinema as an ‘aesthetic medium,’ referring to the films made by other amateur experimental filmmakers, and an ‘action’ made by The 70s members, in Hong Kong in the 1960s and 1970s.

From the documentary Diaoyu Islands to the filmic essay Arty Youths, The 70s was also looking for a new cinematic language to activate their actions. However, the various setbacks of the screening of Arty Youth reflect the obstacles in their visual activism: the political red lines of the colonial government, the prevalence, if not monopoly, of commercial cinema, the language barrier, the marginal position of Hong Kong in the world revolutionary map. Moreover, as the films were not made mainly as an ‘aesthetic medium’ in a director-centred system of authorship but as a collective witness, manifesto and action, their experimentality and transformation of style have to be examined in the context of the inextricable relations filmmaking and contentious performances in social activism. All these may reveal why the films in question are hardly known to Hong Kong film history, and why little attention has been paid to experimental cinema and its relationship to social movements in the study of Hong Kong cinema in the past.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to Mok Chiu Yu, Ho Ah-Lam, Sing Song-yong, Ma Ran, Dogase Masato, Cheung Tit-Leung (1982–2020), Timmy Chen and Xu Xiaohong (1978-2023) who rendered me the most generous help in the writing of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Lu Pan

Lu Pan is Associate Professor in the Department of Chinese History and Culture at The Hong Kong Polytechnic University. Pan is author of three monographs: In-Visible Palimpsest: Memory, Space and Modernity in Berlin and Shanghai (Bern: Peter Lang, 2016), Aestheticizing Public Space: Street Visual Politics in East Asian Cities (Bristol: Intellect, 2015) and Image, Imagination and Imaginarium: Remapping World War II Monuments in Greater China (Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020).

Notes

1 Law Kar also explained why the film exhibition was ‘amateur’. The organizer wanted to attract more people to participate in the independent filming and exhibition by downplaying experimentality. ‘Amateur film’ sounds like a more approachable name. The films still had to go through a jury process before they were selected for screening, but the criteria were loose. In the mid-1970s, the Phoenix Film Club changed the exhibition’s name to ‘Experimental Shorts Exhibition’ and awarded prizes (Law Kar Citation2018, p. 54).

2 The attribution according to Hong Kong Film Archive’s record of the director of the film was, however, wrong. The current entry Long King Cheong 龍景昌, another former member of The 70s, was actually the person who brought the copy to the archive.

3 Interview with Mok June 25, 2020.

References

- Chan, T-h. (2016). 《「火紅年代」青年刊物的身分探索與文學探索: 《盤古》、《文學與美術》、《文美月刊》與《70年代》雙週刊研究》 [The explorations of identity and literature in Hong Kong’s youth journals during the “fiery Years”: A study of Pangu, Wenxue Yu Meishu, Wenmei Yuekan and the 70’s Biweekly]. PhD diss., Division of Chinese Language Literature, Degree Granting Institution, Chinese University of Hong Kong.

- Chang, W-h., & Chow, S-c. (2011). 《製造香港: 本土獨立紀錄片初探》 [Making Hong Kong: A study of Hong Kong independent documentaries]. Hong Kong Film Critics Society.

- Cheung, E. M-k. (2010). 《尋找香港電影的獨立景觀》 [In pursuit of independent visions in Hong Kong cinema]. Joint Publishing Company.

- Cheung, G. K-w. (2009). Hong Kong’s watershed: The 1967 riots. Hong Kong University Press.

- Elshaw, G. (2000). The Depiction of late 1960’s Counter Culture in the 1968 Films of Jean-Luc Godard. Master’s thesis, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Victoria University of Wellington.

- Fung, M. (2001). 《自主世代─六十年代至今自主、實驗、另類創作》 [I-GENERATIONs: Independent, experimental and alternative creations from the 60s to now]. Hong Kong Film Archive.

- Fu, P-s. (2019)〈文化冷戰在香港: 《中國學生周報》與亞洲基金會, 1950–1970(上)〉 [The Cultural Cold War in Hong Kong: The Chinese Student Weekly and the Asia Foundation, 1950–1970 (Part I)]. 《二十一世紀》 [Twenty-First Century (21C)] (173), 1–16.

- Fu, P-s. (2019) 〈文化冷戰在香港: 《中國學生周報》與亞洲基金會, 1950–1970(下)〉 [The Cultural Cold War in Hong Kong: The Chinese Student Weekly and the Asia Foundation, 1950–1970 (Part II)]. 《二十一世紀》 [Twenty-First Century (21C)] (174): 67–82.

- Lau, K-w. (2019). 《在60、70年代之交香港文化雜誌的政治性視覺生產初覽》 [A preliminary exploration into the political visual production of Hong Kong cultural magazines at the turn of the 60s and 70s] Master’s thesis, Department Visual Studies Master of Philosophy, Lingnan University, Hong Kong.

- Law, K. (1970). From amateur film to new film: An outlook of the future of Hong Kong cinema. The 70s Biweekly, 13, 8–9.

- Law, K. (2009). Three or Four Things About Allen Fong. Hong Kong Film Archive Newsletter 49: 3–6. https://www.lcsd.gov.hk/CE/CulturalService/HKFA/archive/b5/newsletter/newsletter49.pdf.

- Law, K. (2012). 《60風尚: 中國學生周報影評十年》 [Style of the 1960s: A decade of film criticism in the Chinese Student Weekly]. Hong Kong Film Critics Society.

- Law, K. (2017). 〈 港臺電影文化新生力量的發源與互動 ─1960 至 1970 年代〉 [Emergence and interaction of new forces in Hong Kong and Taiwan film culture: The 1960s–1970s]. National Central University Journal of Humanities, 64, 1–35.

- Law, K. (2018). The re-composition of theatre quarterly and its resonance in Hong Kong. Art Criticism Taiwan, 73, 18–23.

- Law, W-s. (2009). Collaborative colonial power: The making of the Hong Kong Chinese. Hong Kong University Press.

- Law, W-s. (2015). 〈 冷戰中的解殖:香港「爭取中文成為法定語文運動」評析〉 [Decolonization amidst the Cold War: The campaign for Chinese to be an official language in the seventies]. Thinking Hong Kong, 6, 1–20.

- Law, W-s. (2017). 〈「火紅年代」與香港左翼激進主義思潮〉 [The “Red Era” and Hong Kong’s Left-wing Radicalisms]. 《二十一世紀》 [Twenty-First Century (21C), ] 161(6), 71–83.

- Leung, S-m. (2020). Imagining a national/local identity in the colony: The cultural revolution discourse in Hong Kong youth and student journals, 1966–1977. Cultural Studies, 34(2), 317–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502386.2019.1709095

- Lin, C-h. (2008). 〈冷戰現代性的國族╱性別政治: 《今日世界》分析〉 [Cold War Modernity, Nationality and Sexual Politics in World Today (1952–1980)]. Master’s thesis, Graduate Institute for Social Transformation Studies, Shih Hsin University.

- Lin, W. (2018). Interview with Law Kar.” Taiwan Spectrum: Imagining the Avant-garde: Film Experiments of the 1960s, 54. Taiwan International Documentary Film Festival.

- Mok, Chiu-yu (Li Yu Si). (1980a). 〈你仍否相信電影可以改變社會(一): 為什麼拍一齣卅五毫米的獨立短片〉 [Do you still believe that film can change society (I): Why make a 35mm short film?]. 《電影雙周刊》. City Entertainment Magazine, 49, 24–25, 28.

- Mok, Chiu-yu (Li Yu Si). (1980b). 〈你仍否相信電影可以改變社會(二): 為什麼拍一齣卅五毫米的獨立短片〉 [Do you still believe that film can change society (II): Why make a 35mm short film?]. 《電影雙周刊》. City Entertainment Magazine, 50, 32–33, 39.

- Mok, Chiu-yu (Li Yu Si). (1980c). 你仍否相信電影可以改變社會(三): 為什麼拍一齣卅五毫米的獨立短片〉 [Do you still believe that film can change society (III): Why make a 35mm short film?]. 《電影雙周刊》. City Entertainment Magazine, 51, 37. 41.

- Roberts, P. M., & Carroll, J. M. (2016). Hong Kong in the Cold War. Hong Kong University Press.

- Tarrow, S. (2008). Charles tilly and the practice of contentious politics. Social Movements Studies, 7(3), 225–246.

- Tilly, C. (2008). Contentious performances. Cambridge University Press.

- Wu, X-r. (1998). 《香港七十年代靑年刊物: 回顧專集》 [Youth publications in the seventies Hong Kong: Review Essays]. Ce hua zu he.

- Wu, Y-j. (2017). 〈“香港意識”的香港電影批評的正式起步論《中國學生週報》電影版的電影批評〉 [Official beginning of Hong Kong film criticism with “Hong Kong consciousness”: On the film critics in the film page of the Chinese Students Weekly]. 《當代電影》. Contemporary Cinema, 6, 131–135.

- Yeung, W-y. (2019). 《香港的第三條道路:莫昭如的安那其民眾戲劇》 [The third path for Hong Kong: Mok Chiu Yu’s anarchy and people’s theater]. Typesetter Publishing.

- Zhao, X-f. (2017). 民族主義與殖民主義——“友聯” 及《中國學生週報》的思想悖論〉 [Nationalism and colonialism - the paradox of the ideology of the "Union" and The Chinese Student Weekly]. 《社會科學輯刊》. [She Hui ke Xue ji Kan, 4, 165–171.