Abstract

A case with a patient who suffered an upper lip amputation and a lower lip laceration due to dog bite is presented. The amputated segment was replanted using microsurgical technique. The operative technique and postoperative care is presented, as well as a review of the current literature on the subject.

Introduction

Lip trauma is common due to the exposed position in the face. This exposition also makes scars and deformities clearly visible when looked upon; hence, a meticulous repair of lip injuries is important for the cosmetic outcome. Lip amputations, however, are rare and swift management with microsurgical approach is essential for a good cosmetic and functional outcome. We present a case of lip amputation due to dog bite and a review of the literature.

Methods

A Medline/PubMed search was performed for all scientific English literature involving lip amputation and replantation using microsurgery. The keywords used were “lip amputation,” “lip avulsion,” “lip replantation,” and “lip reimplantation.”

Case report

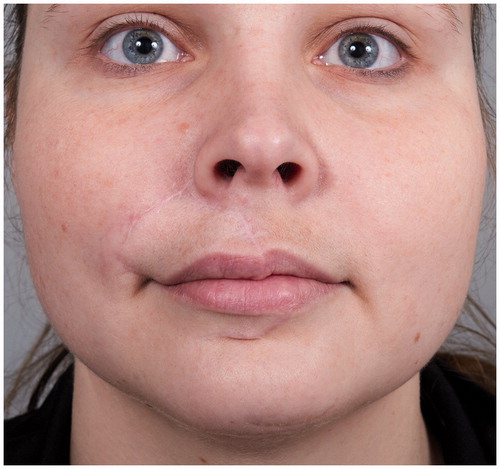

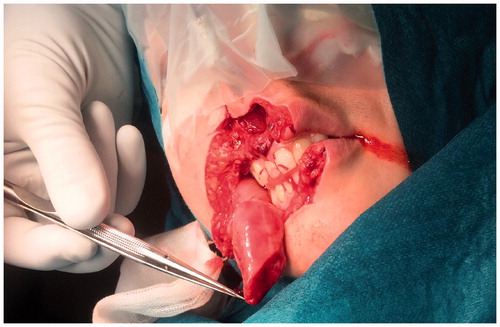

A 28-year-old woman presented at an emergency department on a weekend night at a rural hospital following dog bites sustained to her lips. There were two bites, one that lacerated the lower lip that was still connected to the face by a small, lateral pedicle and one that amputated more than half of the upper lip. The defect crossed the philtrum medially and extended laterally to the nasolabial fold (). No other injuries were afflicted to the patient. The patient was referred to the Sahlgrenska University Hospital and arrived at the Department of Plastic Surgery 90 min after the trauma. The amputate, measuring 4.5 × 3 cm, had been kept in a hypothermic state (). Emergency replantation surgery was initiated. Peroperatively, a 1 mm superior labial artery was identified laterally on the amputate and was microsurgically anastomosed to the proximal stump of the superior labial artery using 10–0 S and T sutures. The ischemia time was approximately 4 h and 45 min. Even after reperfusion, no veins suitable for anastomosis could be identified. One nerve was identified, but it was to damage to repair. The lip was sutured in three layers: the mucosa, the orbicularis oris muscle, and finally, the skin, which was loosely sutured to allow bleeding and lessen the risk of hematoma. The lip rapidly turned blue as a sign of venous congestion. A leech (Hirudo medicinalis) was applied to the lip in order to achieve venous drainage and it immediately regained adequate skin color and became less swollen (). The lower lip was also sutured in three layers and was adequately vascularized through the right inferior labial artery during the whole procedure. During first night, leeches were applied every 45 min, and thereafter, the interval was extended, guided by the color of the lip; day 2 every 90 min, day 3–5 every 2 h, day 6–10 every 3 h, day 11–12 every 4 h. On the 13th day, the lip did not need leech therapy and the patient could be discharged on day 14. Anticoagulant therapy was provided using subcutaneous injection of dalteparin 5000 U/day for 14 days. The constant bleeding from the lip during leech therapy necessitated several blood transfusions to a total of seven units.

Figure 1. Preoperative picture showing the defect in the upper lip and the large laceration of the lower lip.

Figure 2. The amputated part of the upper lip, measuring 4.5 × 3 cm, was kept in a hypothermic state.

Figure 3. Shortly after the lip was reapproximated, venous congestion occurred. A leech was immediately applied and the lip regained normal color.

Broad spectrum antibiotics (meropenem 0.5 g three times daily) was used for 10 days in order to prevent infections from bacteria associated with dog bites and bacteria of the leeches normal flora (e.g. Aeromonas hydrophila).[Citation1]

Nutrition was achieved by clinifeeding tube during the first three days but was converted to parenteral nutrition due to severe nausea and vomiting. On the 8th day, the patient could ingest sufficient amounts per oral route.

The patient received a tracheostomy preoperatively in order to secure the airway due to face swelling and the continuous bleeding from the lip which to some extent went into the mouth and throat.

After discharge, the follow-up was uneventful. At one-year follow-up, the patient had good oral continence, good lip motion, no problems with articulation, but the sensitivity for heat/cold and pin prick was still poor (). The lip still has a slight edema, which is slowly subsiding.

Discussion

Lip amputation is rare but has severe consequences both functionally and esthetically if it cannot be primarily reconstructed with the use of the amputated tissue. It is therefore important to quickly provide the means for a microsurgical repair. Smaller segments (≤1.5 cm) can, in an elective setting, survive as composite grafts.[Citation2] However, in a traumatic setting, especially with larger segments, the chance for the survival of a composite graft is small [Citation3] and highly unpredictable and can therefore not be recommended.

In the literature search, 32 cases were found in English literature [Citation4–21], 16 case reports and two case series of microsurgically treated amputated lips (). Even after the artery has been anastomosed and the lip amputate revascularized, the search for a suitable vein can be difficult. In the lips, the veins are usually small, and since the trauma mechanism in 84% of the cases were some sort of bite, the chance to find a good-size anastomosable vein is small. If, however, a vein anastomosis can be accomplished, the resulting outflow is often insufficient. In the 15 cases with venous anastomosis, some sort of method to relieve venous congestion was still needed in 60% of the cases (). This can be achieved in several ways; medicinal leeches, mechanical pricking with topical heparin or intra-replant heparin.[Citation4–21] Without venous anastomosis, it is essential to use some sort of venous drainage for the replanted segment to survive. Therefore, it is good a good idea to be prepared to use an additional method to relieve venous congestion, even when a successful venous anastomosis is accomplished. In the cases where no venous anastomosis was possible, the average duration for the relief of venous congestion was 6.6 days (range 1–12 days). This is in accordance with neoangiogenesis creating functional veins 4–6 days postreplantation.[Citation22,23] In the presented case, we used medicinal leeches, which can be hard to accept for the patient, even though the patient tolerated it well in this case. The usage of leeches also involves significant blood loss which requires blood transfusions. In this case, the patient had a total of seven units of blood, which is within the normal limit in when using leeches for 12 days. There is a risk of infection but with the use of proper prophylactic antibiotic, the risk can be decreased. Even if the time lapse from trauma to repair is long, a successful lip replantation has been managed after as long as 17 h of ischemia.[Citation9] Thus, even if the primary contact is at a rural hospital where microsurgery is not available, it is well motivated to send the patient to a secondary hospital with experience in microsurgical technique, provided that the amputate is handled correctly and put in a hypothermic state.

Table 1. Lip replantation cases reported in English literature (n = 32).

About 19% (n = 6) of the 32 cases got partial necrosis, none had total necrosis.

There is no international consensus on what type of anticoagulant/s or prophylactic antibiotics to use in this type of cases. Heparin, dextran, and aspirin were the most commonly used substances in these 32 cases, either alone or in combinations.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- Snower DP, Ruef C, Kuritza AP, Edberg SC. Aeromonas hydrophila infection associated with the use of medicinal leeches. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:1421–1422.

- Walker JC Jr, Sawhney OP. Free composite lip grafts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1972;50:142–146.

- Daraei P, Calligas JP, Katz E, et al. Reconstruction of upper lip avulsion after dog bite: case report and review of literature. Am J Otolaryngol. 2014;35:219–225.

- James NJ. Survival of large replanted segment of upper lip and nose. Case report. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976;58:623–625.

- Höltje WJ. Successful replantation of an amputated upper lip. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;73:664–670.

- Schubert W, Kimberley B, Guzman-Stein G, Cunningham BL. Use of the labial artery for replantation of the lip and chin. Ann Plast Surg. 1988;20:256–260.

- Crawford CR, Hagerty RC. Survival of an upper lip aesthetic complex using arterial reanastomosis only. Ann Plast Surg. 1991;27:77–79.

- Husami TW, Cervino AL, Pennington GA, Douglas BK. Replantation of an amputated upper lip. Microsurgery. 1992;13:155–156.

- Jeng SF, Wei FC, Noordhoff MS. Successful replantation of a bitten-off vermilion of the lower lip by microvascular anastomosis: case report. J Trauma. 1992;33:914–916.

- Hirasé Y, Kojima T, Hayashi J, Nakano M. Successful upper labial replantation after 17 hours of ischemia: case report. J Reconstr Microsurg. 1993;9:327–329.

- Venter TH, Duminy FJ. Microvascular replantation of avulsed tissue after a dog bite of the face. S Afr Med J. 1994;84:37–39.

- Walton RL, Beahm EK, Brown RE, et al. Microsurgical replantation of the lip: a multi-institutional experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:358–368.

- Wong SS, Wang ML. Successful replantation of an bitten-off lower lip: case report. J Trauma. 1999;47:602–604.

- Duroure F, Simon E, Fadhul S, et al. Microsurgical lip replantation: evaluation of functional and aesthetic results of three cases. Microsurgery. 2004;24:265–269.

- Taylor HO, Andrews B. Lip replantation and delayed inset after a dog bite: a case report and literature review. Microsurgery. 2009;29:657–661.

- Baj A, Beltramini GA, Laganà F, Gianni AB. Microsurgical upper lip replantation: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68:664–667.

- Liliav B, Zaluzec R, Hassid VJ, et al. Lip replantation: a viable option for lower lip reconstruction after human bites, a literature review and proposed management algorithm. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65:e197–e199.

- Cooney DS, Fletcher DR, Bonawitz SC. Successful replantation of an amputated midfacial segment: technical details and lessons learned. Ann Plast Surg. 2013;70:663–665.

- DeLeon AN, Rinard JR, Mahabir RC. Successful replantation of a portion of the upper and lower lip with the oral commissure. Ann Plast Surg. 2014;72:3–4.

- Deleyiannis FW, Powers MA. Lip replantation in an infant after prolonged ischemia: age as a factor affecting success. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133:240e–241e.

- Baptista RR, Barreiro GC, Alonso N. Pediatric lip replantation: a case of supermicrosurgical venous anastomosis. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2015;31:154–156.

- Whalen GF, Zetter BR. Angiogenesis. Wound healing: biochemical and clinical aspects. Philadelphia (PA): Saunders; 1992.

- Smith JW. The anatomical and physiologic acclimatization of tissue transplanted by the lip switch technique. Plast Reconstr Surg Transplant Bull. 1960;26:40–56.