?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study investigates the impact of foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows on poverty reduction in Botswana from 1980 to 2014. The main objective of this study is to establish whether FDI plays a positive role in poverty reduction. The study employs autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) bounds test approach to co-integration and the error correction model to investigate the relationship. To ensure robustness, the study uses three poverty reduction proxies which are household consumption expenditure (Pov1), infant mortality rate (Pov2), and life expectancy (Pov3). The findings from this study revealed that FDI has a positive impact on poverty reduction in the short run and a negative impact in the long run when life expectancy is used as a poverty reduction measure. When infant mortality rate is used as a poverty reduction proxy, an insignificant relationship is registered in both the long run and the short run. A negative impact of FDI on poverty reduction is confirmed in the short run when household consumption expenditure is used as a poverty reduction proxy, while in the long run an insignificant relationship is reported. The study concludes that the impact of FDI on poverty reduction is sensitive to the poverty reduction proxy used.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

In this study, the impact of foreign direct investment (FDI) on poverty reduction is investigated for Botswana employing data from 1980 to 2014. The main objective of the study is to investigate if FDI can be used as a policy instrument in poverty reduction in Botswana. Three poverty reduction proxies namely, household consumption expenditure, infant mortality rate, and life expectancy are used in the study to capture multi-dimensional nature of poverty and to increase the robustness of the results. By employing autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) bounds test approach, the impact of FDI on poverty reduction is investigated. The findings from this study revealed that FDI plays a less important role in poverty reduction in Botswana as evidenced by one out of three (life expectancy) poverty reduction proxies where a short-run positive relationship is confirmed. These findings suggest that Botswana may use FDI as a short-term poverty reduction instrument.

1. Introduction

The debate on the poverty–FDI nexus has been raging for some time and has culminated in a number of studies that have attempted to disentangle the relationship. Although the theoretical literature suggests a positive impact of FDI on poverty reduction, the findings from previous studies have been mixed. The bulk of studies that have attempted to investigate the relationship between FDI and poverty reduction have focused on the impact of FDI on poverty reduction where poverty reduction is proxied by economic growth (see Almfraji, Almsafir, & Yao, Citation2014; Hsiao & Hsiao, Citation2006). Studies on the direct impact of FDI on poverty reduction are limited, and the results are also inconclusive.

Although the theoretical literature proposes a number of channels through which FDI positively impacts on poverty reduction, the empirical evidence is mixed. The results have varied depending on the poverty reduction proxy used, study country or region, and the methodology employed. Among the studies that have investigated the direct impact of FDI on poverty reduction, there are some that have confirmed a positive impact of FDI on poverty reduction (see Fowowe & Shuaibu, Citation2014; Jalilian & Weiss, Citation2002; Soumare, Citation2015). However, other studies have found FDI to have a negative impact on poverty reduction. Among these studies is that by Huang, Teng, and Tsai (Citation2010). Apart from studies that have confirmed either a positive or negative impact of FDI on poverty reduction, there are some studies that have found FDI to have no significant effect on poverty reduction (see Akinmulegun, Citation2012; Tsai & Huang, Citation2007). Thus, the mixed results from the empirical research suggest the need to consider the impact of FDI on poverty reduction on a case-by-case basis, necessitating a need to investigate such a relationship in Botswana. This unresolved debate on the relationship between FDI and poverty is still raging despite the rising need for governments to find a solution to poverty reduction and to steer their economies towards sustainable development paths and meet the Sustainable Development Goals 2030 (United Nations, Citation2018). Another study on Botswana on the relationship between FDI and poverty reduction could contribute to the ongoing debate and also give insight on poverty reduction policies in Botswana.

This study differs from previous studies in a number of ways. First, the study investigates the impact of FDI on poverty reduction using the newly developed ARDL approach—an approach associated with a number of advantages. The ARDL bounds testing approach to co-integration provides unbiased estimates of the long-run model, even in cases where some variables are endogenous (Odhiambo, Citation2009). Another advantage of the ARDL approach is that it uses a reduced form single equation, while other conventional co-integration methods employ a system of equations (Pesaran & Shin, Citation1999). Second, the study employs three poverty reduction proxies—household consumption expenditure, infant mortality rate, and life expectancy. Unlike other studies that have relied on one poverty reduction measure, the three poverty reduction proxies measure income and non-income dimensions of poverty. The poverty reduction proxies employed in this study, therefore, offer a more holistic measure of poverty reduction. Third, the study focuses on Botswana using time series data, unlike other studies that have relied on cross sectional data, which are unable to sufficiently capture heterogeneity across countries (see Odhiambo, Citation2009).

Botswana has been selected for this study because it has received little coverage on the direct impact of FDI on poverty reduction (see Fowowe & Shuaibu, Citation2014). Moreover, it is among the countries with the lowest population in Southern Africa in the upper middle income bracket receiving a fair share of FDI inflows (World Bank, Citation2016). While poverty levels have declined over the years, they remain high, with 43% of the population living below the poverty line of $1.90 in 1986 compared with 19% in 2010 (World Bank, Citation2016). The main objective of this study is, therefore, to investigate the impact of FDI on poverty reduction in Botswana. The findings in this study are anticipated to inform poverty reduction policies in Botswana. Against this objective, two hypotheses will be tested in this paper, namely: (i) FDI has a positive impact on poverty reduction in both the long run and the short run; and (ii) the impact of FDI on poverty reduction is sensitive to the poverty proxy used.

The Transitional Plan for Social and Economic Development of 1965 marked the implementation of socio-economic policies through the National Development Plans (NDP) in Botswana (Ministry of Finance and Development Planning, Citation2016). The government policy on FDI is enshrined in Pillar 2 in the NDP 10, which strives to build a prosperous, productive, and innovative nation (Ministry of Finance and Development Planning, Citation2016). The economy of Botswana in the 1980s was centred on mining, following the discovery of diamonds in 1967. The main focus was building capacity in the mining sector to exploit and negotiate FDI deals with multinational companies (Criscuolo, Citation2008). Government policies that focused on attracting FDI included exchange control reforms, building a stable and sound macroeconomic environment, regulatory reforms, regional integration, and investment incentives, among other policy initiatives aimed at building an environment conducive to investment. Despite the reforms implemented, FDI inflows remained depressed between 1980 and 2014. Average FDI inflows as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) was at 3.2% during the period, with FDI inflows from 2000 accounting for the larger proportion of this figure (World Bank, Citation2016).

Poverty reduction in Botswana has been guided by the NDP that were rolled out since 1979 (Ministry of Finance and Development Planning, Citation2016). The NDP build on each other in order to strengthen or provide new initiatives aimed at achieving targets set in the long-term vision, Vision 2016 (Africa Development Bank, Citation2009). The poverty reduction strategy recurs in all NDP, indicating an area of concern to government over the years. The government, through projects and policies such as the National Strategy for Poverty Reduction launched in 2003, has taken initiatives to broaden and deepen its programmes on poverty alleviation. Pillar 3, which is building a compassionate, just, and caring nation, has included poverty reduction and increased access to health, education, and employment among its important poverty alleviation initiatives (Ministry of Finance and Development Planning, Citation2016). Government policies and strategies are three pronged: First is stimulating economic growth, which includes economic diversification, employment creation, and income generation capacity and empowerment as ways of drawing the poor from the poverty trap (Seleka, Siphambe, Ntseane, Kerapeletswe, & Sharp, Citation2007). Second are initiatives focused on the development of infrastructure to increase government capacity in service provision (Seleka et al., Citation2007). Third is the provision of social safety nets designed to capture those without access to economic development opportunities (Seleka et al., Citation2007). There has been a positive response to poverty reduction policies, as shown by a reduction in poverty from 30.6% in 2002/2003 to 19.6% in 2009/2010 (Statistics Botswana, Citation2013). However, poverty levels vary depending on settlement type, sex, and district (Statistics Botswana, Citation2013).

The rest of the paper is organised as follows: Section 2 reviews related literature. Section 3 skeletons the estimation techniques. The Section 4 presents the results and their analysis, while the Section 5 concludes the study.

2. Empirical review

FDI can have both direct and indirect positive effects on poverty reduction. Indirect effects include horizontal and vertical spill over effects (Gorg & Greenaway, Citation2004; Sumner, Citation2005). Horizontal spill over effect is achieved through labour movement and demonstration effects (Meyer, Citation2004). Vertical spill over, on the other hand, arises from consumer and producer surplus and is divided into backward and forward linkages. Backward linkages involve the sourcing of intermediate goods by a foreign subsidiary from domestic firms (Gorg & Greenaway, Citation2004; Liu, Wang, & Wei, Citation2009). Forward linkages involve the growth of an industry that uses the output from the foreign subsidiary (Sumner, Citation2005). Direct effects consist of the creation of new jobs for the locals and an increase in investment capital (Klein, Aaron, & Hadjimichael, Citation2001).

The impact of FDI on poverty reduction has received wide coverage in the literature, although the results are still inconclusive. The bulk of these studies have investigated the indirect impact of FDI on poverty, realised through the economic growth channel (see Dollar, Kleineberg, & Kraay, Citation2013; Feeny, Iamsiraroj, & McGillivray, Citation2014; Hsiao & Hsiao, Citation2006). The results from these studies have varied from one study to the other. Of the few studies that have explored the direct impact of FDI on poverty reduction, the results are again inconsistent. Some studies have found a positive impact of FDI on poverty reduction. Zaman, Khan, and Ahmad (Citation2012) and Shamim, Azeem, and Naqvi (Citation2014) investigated the impact of FDI on poverty reduction in Pakistan and they found a positive relationship between FDI and poverty reduction. Soumare (Citation2015), Fowowe and Shuaibu (Citation2014), Israel (Citation2014), and Gohou and Soumaré (Citation2012) also carried out the same study on African countries and found a positive association between FDI and poverty reduction. The same results were confirmed by Ucal (Citation2014) in developing countries and Jalilian and Weiss (Citation2002) in the ASEAN.

Apart from studies that found a positive impact of FDI on poverty reduction, there are some studies that found a negative relationship between the two. For instance, Huang et al. (Citation2010) investigated the impact of FDI on poverty reduction in East Asian countries and Latin America and found a negative relationship between the two. Ali, Nishat, and Anwar (Citation2010) also found FDI to have a negative impact on poverty reduction in Pakistan. The results from these studies reveal that FDI inflows lead to an increase in poverty levels, contrary to theoretical postulations. There are yet some studies that found an insignificant impact of FDI on poverty reduction. Among these studies are those by: (i) Akinmulegun (Citation2012), who investigated the relationship between FDI and poverty reduction in Nigeria; (ii) Tsai and Huang (Citation2007), who investigated the impact of FDI on poverty reduction in Taiwan; and (iii) Sharma and Gani (Citation2004), who carried out an analysis of the nature of the relationship between FDI and poverty reduction in middle- and low-income countries. Thus, FDI was found to have no impact on poverty reduction, hence may not be used as a policy instrument for poverty reduction in the respective countries. The empirical studies have revealed an unsettled debate on the impact of FDI on poverty reduction. The results varied from one sample to the other, time frame, and poverty proxy employed, suggesting importance of a country by country investigation on the nature of the relationship.

3. Estimation techniques

3.1. ARDL approach to co-integration

The ARDL bounds testing approach was selected because of a number of advantages. First, the ARDL approach does not require all variables to be integrated of the same order (Pesaran, Shin, & Smith, Citation2001). Variables can be integrated of order [I (1)], order 0–[I (0)], or fractionally integrated (Pesaran et al., Citation2001, p. 290). Second, the ARDL bounds approach involves the use of a single reduced form equation, unlike other methods that use a system of equations (see Duasa, Citation2007). Third, the ARDL approach to co-integration is robust in a small sample (Odhiambo, Citation2009; Solarin & Shahbaz, Citation2013). Fourth, the ARDL bounds testing approach to co-integration provides unbiased estimates of the long-run model, even in cases where some variables are endogenous (Odhiambo, Citation2009). It is against this background that the ARDL bounds approach was selected in this study.

3.2. Variables

The dependent variables are household consumption expenditure (Pov1), infant mortality rate (Pov2), and life expectancy (Pov3), while the explanatory variables include FDI—FDI inflows as a proportion of GDP and other control variables. The control variables included in the study are human capital (HK) captured by gross primary school enrolment; price level (CPI) captured by Consumer Price Index, trade openness (TOP) captured by a summation of imports and exports as a proportion of GDP, and infrastructure (FTL) by fixed telephone lines.

3.3. Models

The study employs three models to investigate the impact of FDI on poverty reduction. Model 1 investigates the impact of FDI on poverty reduction proxied by household consumption expenditure (Pov1). Model 2 investigates the impact of FDI on poverty reduction proxied by infant mortality rate (Pov2), and Model 3 analyses the impact of FDI on poverty reduction using life expectancy (Pov3) as a poverty reduction proxy. Models 1–3 are specified in Equations (1)–(3), respectively.

where Pov1 is poverty reduction captured by household consumption expenditure; Pov2 is poverty reduction captured by infant mortality rate; Pov3 is poverty reduction captured by life expectancy; FDI is foreign direct investment; TOP is trade openness; HK is human capital; CPI is price level; FTL is infrastructure; is a constant,

are coefficients, and

is the error term.

The ARDL model and the error correction specification are given in Equations (4)–(6) for Model 1, 2, and 3, respectively.

3.4. Model 1: ARDL model specification

where and

are regression coefficients,

is a constant, and

is a white noise error term.

The error correction model for Model 1 is specified as follows:

where and

are coefficients,

is a constant,

is a lagged error term, and

is a white noise error term.

where and

are coefficients,

is a constant, and

is a white noise error term.

The error correction model for Model 2 is specified as follows:

where and

are coefficients,

is a constant,

is a lagged error term, and

is a white noise error term.

Model 3 ARDL Specification:

where and

are coefficients,

is a constant, and

is a white noise error term.

The error correction model for Model 3 is specified as follows:

where and

are coefficients,

is a constant,

is a lagged error term, and

is a white noise error term.

3.5. Data sources

The study employed time series data from 1980 to 2014 to investigate the direct impact of FDI on poverty reduction. The data were obtained from the World Bank Development Indicators database. Data analysis was done using Microfit 5.0.

4. Results

4.1. Unit root test

Although the ARDL bounds testing approach employed in this study does not require pre-testing of the unit root of variables included in the model, pretesting was done to determine if the variables are integrated of the highest order of one—I [(1)]. Table shows the unit root test results using Dickey Fuller Generalised Least Squares (DF-GLS), Phillips Perron (PP), and Perron unit root test (PPUroot test).

Table 1. Unit root test results

The unit root results presented in Table tend to vary from one unit root test to the other; overall, the results reveal that all variables are stationary in levels or in first difference. This confirms the suitability of ARDL-based analysis.

4.2. Bound F-statistic to co-integration

The results of the bounds test and the critical values are presented in Table .

Table 2. Co-integration results and critical values

The calculated F-statistics in all the Models—Models 1–3—are 4.81, 3.69, and 9.11, respectively. The calculated F-statistics are compared to the Pesaran et al. (Citation2001) critical values, also reported in Table . In all the models, the calculated F-statistic is greater than the critical values—Model 1 at 1%, Model 2 at 10%, and Model 3 at 1% significance level. Therefore, co-integration is confirmed in all the models.

4.3. Impact analysis

The ARDL procedure is used in the estimation of the three models after confirming a long-run relationship in Models 1–3. The next step in the estimation process is the optimal lag length selection for all the models. Bayesian Information Criteria and Akaike Information Criteria are used to select a parsimonious model. The optimal lag length selected for Model 1 is ARDL (2 1, 0, 1, 0, 2); Model 2 is ARDL (2, 3, 1, 1, 0, 0), and for Model 3 is ARDL (2, 2, 2, 2, 0, 0). The long-run and short-run coefficients for Model 1, Model 2, and Model 3 are presented in Table .

Table 3. Long-run and short-run coefficients: Models 1–3

The results in Table , Panel A and Panel B, for Model 1 reveal that FDI has an insignificant impact on poverty reduction in the long run. However, a negative and statistically significant relationship was confirmed in the short run. The results suggest that FDI worsens poverty levels in Botswana only in the short run. Although these results were not expected, they are not unique to Botswana. Huang et al. (Citation2010) and Ali et al. (Citation2010), among others, found the same results. The negative impact of FDI on poverty reduction in the short run could be a result of crowding-out effect of the new investment on domestic-owned companies.

Long-run and short-run results for other variables reveal that (i) past poverty reduction (ΔPov1) has a positive impact on poverty reduction; (ii) human capital (HK) is insignificant in both the long run and the short run; (iii) trade openness (TOP) is insignificant in the long run, although in the short run, the coefficient of trade openness (ΔTOP) is positive and statistically significant; (iv) price level (CPI) is positive and statistically significant in both the long run and the short run; a certain level of price increase is important in stimulating industry production, thereby increasing the availability of products and jobs (Mohr et al., Citation2015); (v) infrastructure (FTL) is negative and has a statistically significant impact on poverty reduction in Botswana in the long run, while in the short run, a positive significant impact was registered at a 10% level of significance; (vi) the error correction term lagged once [ECM (−1)] is negative and statistically significant at 1%, and thus adjustment to equilibrium following a shock to the economy is anticipated at the rate of 57% per annum; and (vii) the explanatory power of Model 1 is 79%, as reported in Table , Panel B.

The empirical results presented in Table , Panel A and Panel B, for Model 2 confirm that FDI is insignificant in the short run and the long run. The results imply that FDI has no impact on poverty reduction in Botswana, irrespective of the time frame under consideration. The results suggest that Botswana may not target FDI as a policy instrument solely for poverty reduction purposes. The results were not expected, but they compare favourably with other studies (see Sharma & Gani, Citation2004; Tsai & Huang, Citation2007; Gohou & Soumaré, Citation2012; among other studies).

Other long-run and short-run results confirm that (i) past poverty reduction (ΔPov2) is positive and statistically significant at 5% level of significance in the short run; (ii) human capital (HK) is negative and statistically significant in the long run and in the short run; (iii) trade openness (TOP) is insignificant in the short run and the long run; (iv) price level (CPI) is negative and statistically significant in the long run and insignificant in the short run; thus, in the long run high prices erode the purchasing power of the poor, therefore putting them on a worse-off position (Mohr et al., Citation2008, p. 480); (v) infrastructure (FTL) is positive and statistically significant in the long run and in the short run; (vi) the lagged error correction ECM (−1) is 0.50 and statistically significant at 5%, implying that it takes two years to have full adjustment to the equilibrium when there is disequilibrium in the economy; and (vii) Model 2 is a perfect fit, as shown by an R2 of 71%.

Long-run and short-run results presented in Table , Panel A and Panel B, for Model 3 show that FDI has a negative and statistically significant impact on poverty reduction in the long run, while in the short run, a positive and statistically significant relationship was revealed. The results suggest that FDI worsens poverty reduction in the long run but aid in poverty reduction in the short run. Thus, FDI has short-term benefits to poverty reduction when life expectancy is used as a poverty measure. Although a negative and statistically significant relationship was confirmed in the long run, these results were not expected, but they compare favourably with findings by Huang et al. (Citation2010). The long-run negative impact of FDI on poverty reduction could be a result of crowding-out effect of foreign subsidiaries on domestic firms. A positive statistically significant impact of FDI on poverty reduction was expected. Some studies also support the results (Israel, Citation2014; Uttama, Citation2015). The short-run positive impact of FDI on poverty reduction is supported in theory by the spill-over effects (Gorg & Greenaway, Citation2004) and direct effects (Klein et al., Citation2001). Thus, the timing on the use of FDI as a policy instrument to positively affect poverty reduction is important in Botswana.

Other long-term and short-term results presented in Table , Panel A and Panel B, for Model 3 show that (i) past poverty reduction (Pov3) has a positive impact on poverty reduction; (ii) human capital (HK) is statistically insignificant in both the short run and the long run; (iii) trade openness (TOP) is insignificant in the long run, while there is a negative and statistically significant impact in the short run; (iv) price level (CPI) is positive and statistically significant in the long run and in the short run; (v) infrastructure (FTL) is insignificant in the short run and in the long run; (vi) the error correction term ECM (−1) is 0.09 and statistically significant at 1%, implying that it takes over 10 years to get a full adjustment in the economy when there is disequilibrium; and (vii) the explanatory power of the model is 99%, as confirmed by the R2 reported in Table , Panel B.

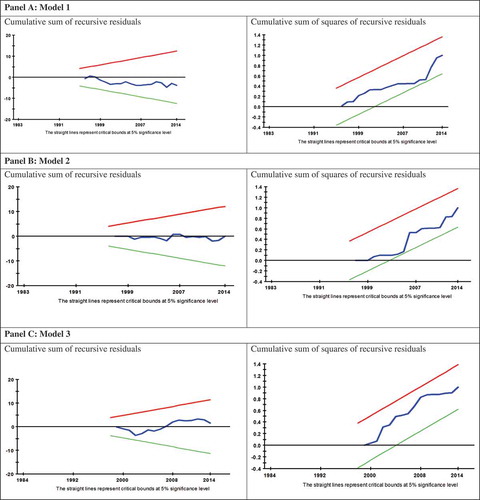

Diagnostic tests were performed on Models 1–3 for serial correlation, functional form, normality, and heteroscedasticity. Model 1 and Model 2 passed all the tests, while Model 3 passed the serial correlation, normality, and heteroscedasticity tests, but failed the functional form. After the inspection of the Cumulative Sum of Recursive Residuals (CUSUM) and Cumulative Sum of Squares of Recursive Residuals (CUSUMQ), the model was found to be stable at 5%. The results for the diagnostic tests are presented in Table .

Table 4. Diagnostic test results: Models 1–3

The plot for CUSUM and CUSUMSQ are given in Figure , Panel C, Panel D, and Panel E for Models 1–3, respectively.

5. Conclusion

This paper investigated the dynamic impact of FDI on poverty reduction in Botswana between 1980 and 2014. The impact of FDI on poverty reduction has received much attention, but only a few studies have investigated the direct impact of FDI on poverty reduction. The majority of previous studies have investigated the indirect impact of FDI on poverty reduction, realised through economic growth. Of the few studies that have investigated the direct impact of FDI on poverty reduction, the results are inconclusive. This study attempted to investigate the direct impact of FDI on poverty reduction in Botswana. Furthermore, the study also employed the ARDL bounds testing approach because of its various known advantages. The study also used three poverty reduction proxies to investigate the impact of FDI on poverty reduction. This allowed the study to adequately measure multi-dimensional aspects of poverty and to increase robustness of the results. The results from this study revealed that FDI has an insignificant impact on poverty reduction in both the long run and the short run when infant mortality rate is used as poverty reduction proxy. When household consumption expenditure is employed as a proxy for poverty reduction, a negative impact is confirmed in the short run, while in the long run an insignificant impact is registered. When life expectancy is used as a proxy of poverty reduction, a negative impact is reported in the long run, while a positive impact is registered in the short run.

It can be concluded that the impact of FDI on poverty reduction is sensitive to the poverty reduction proxy used and the time considered. In Botswana, FDI plays a less significant role in poverty reduction as evidenced by one poverty reduction proxy (life expectancy) where a positive impact is confirmed in the short run. Based on the findings, it can be recommended that policymakers in Botswana may enhance FDI policies in order to reduce poverty reduction as a short-term measure. This study, like any other study, has some limitations that future researcher can explore. The paper is based on data from 1980 to 2014. Increasing the sample size may lead to a different conclusion. Further, this study employed only three poverty reduction proxies, namely: household consumption expenditure, life expectancy, and infant mortality rate, to investigate the impact of FDI on poverty reduction. Future research can benefit from exploring the nature of the relationship between FDI and other poverty reduction measures.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

M. T. Magombeyi

M. T. Magombeyi is a doctoral student at the University of South Africa.

N. M. Odhiambo

N. M. Odhiambo is a Professor in the Economics Department at the University of South Africa.

References

- Africa Development Bank. (2009). Botswana country strategy paper 2009–2013. Retrieved July 19, 2015, from http://www.afdb.org.

- Akinmulegun, S. O. (2012). Foreign direct investment and standard of living in Nigeria. Journal of Applied Finance and Banking, 2(3), 295–309.

- Ali, M., Nishat, M., & Anwar, T. (2010). Do foreign inflows benefit Pakistan poor? The Pakistan. Development Review, 48(4), 715–738.

- Almfraji, M. A., Almsafir, M. K., & Yao, L. (2014). Economic growth and foreign direct investment inflows: The case of Qatar. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 109, 1040–1045. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.12.586

- Criscuolo, A. (2008). Briefing note: Botswana. Retrieved June 15, 2015, from http://www.sitesources.worldbank.org

- Dollar, D., Kleineberg, T., & Kraay, A. (2013). Growth still is good for the poor (Policy Research Paper 6568). Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Duasa, J. (2007). Determinants of Malaysian trade balance: An ARDL bounds testing approach. Journal of Economic Cooperation, 28(3), 21–40.

- Feeny, S., Iamsiraroj, S., & McGillivray, M. (2014). Growth and foreign direct investment in the Pacific Island countries. Economic Modelling, 37, 332–339. doi:10.1016/j.econmod.2013.11.018

- Fowowe, B., & Shuaibu, M. I. (2014). Is foreign direct investment good for the poor? New evidence from African countries. Economic Change and Restructuring, 47, 321–339. doi:10.1007/s10644-014-9152-4

- Gohou, G., & Soumaré, I. (2012). Does foreign direct investment reduce poverty in Africa and are there regional differences? World Development, 40(1), 75–95. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.05.014

- Gorg, H., & Greenaway, D. (2004). Much ado about nothing? Do domestic firms really benefit from foreign direct investment? The World Bank Research Observer, 19(2), 171–197. doi:10.1093/wbro/lkh019

- Hsiao, S. T., & Hsiao, M. W. (2006). Foreign direct investment and GDP in east and South East Asia-panel data versus series causality analysis. Journal of Asian Economics, 17(6), 1082–1106. doi:10.1016/j.asieco.2006.09.011

- Huang, C., Teng, K., & Tsai, P. (2010). Inward and outward foreign direct investment and poverty reduction: East Asia versus Latin America. Review of World Economics, 146(4), 763–779. doi:10.1007/s10290-010-0069-3

- Israel, A. O. (2014). Impact of foreign direct investment on poverty reduction in Nigeria. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development, 5(20), 34–45.

- Jalilian, H., & Weiss, J. (2002). Foreign direct investment and poverty in the ASEAN region. ASEAN Economic Bulletin, 19(3), 231–253. doi:10.1355/AE19-3A

- Klein, M., Aaron, C., & Hadjimichael, B. (2001). Foreign direct investment and poverty reduction (Policy Research Working Paper 2613). World Bank. Retrieved from documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/715711468766466832

- Liu, X., Wang, C., & Wei, Y. (2009). Do local manufacturing firms benefit from transactional linkages with multinational enterprises in China? Journal of International Business Studies, 40(7), 1113–1130. doi:10.1057/jibs.2008.97

- Meyer, K. E. (2004). Perspectives on multinational enterprises in emerging economies. Journal of International Business Studies, 35(4), 259–276. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400084

- Ministry of Finance and Development Planning. (2016). Overview on NDP 10. Retrieved January 20, 2017, from http://www.gov.bw.en/Ministry--Authorities/Ministry-of-Finance-and-Development-Planning.

- Mohr, P., Fourie, L., and Associates. (2008). Economics for South African students (4th ed.). Pretoria: Van Schaik Publisher.

- Mohr, P., & Associates. (2015). Economics for South African students (5th ed.). Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers.

- Odhiambo, N. M. (2009). Energy consumption and economic growth nexus in Tanzania: An ARDL bounds testing approach. Energy Policy, 37, 617–622. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2008.09.077

- Pesaran, M. H., & Shin, Y. (1999). An autoregressive distributed lag modelling approach to cointegration analysis. In S. Storm (Ed.), Econometrics and economic theory in the 20th century: The Ragnar Frisch centennial symposium (Chapter 11, pp. 1–31). Cambridge University Press.

- Pesaran, M. H., Shin, Y., & Smith, R. J. (2001). Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 16(3), 289–326. doi:10.1002/(ISSN)1099-1255

- Seleka, T. B., Siphambe, H., Ntseane, N. M., Kerapeletswe, C., & Sharp, C. (2007). Social safety nets in Botswana: Administration, targeting and sustainability. Botswana Institute for Development Policy Analysis. Retrieved from https://www.bidpa.bw/publication/details.php

- Shamim, A., Azeem, P., & Naqvi, M. A. (2014). Impact of foreign direct investment on poverty reduction in Pakistan. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 4(10), 465–490. doi:10.6007/IJARBSS/v4-i10/1244

- Sharma, B., & Gani, A. (2004). The effects of foreign direct investment on human development. Global Economy Journal, 4(2), Article 9. doi:10.2202/1524-5861.1049

- Solarin, S. A., & Shahbaz, M. (2013). Trivariate causality between economic growth, urbanization and electricity consumption in Angola: Cointegration and causality analysis. Energy Policy, 60, 876–884. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2013.05.058

- Soumare, I. (2015). Does foreign direct investment improve welfare in North Africa? Africa Development Bank. Retrieved from https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Document/Publication

- Statistics Botswana. (2013). Botswana core welfare indicators. Retrieved July 13, 2015, from www.bw.undp.org

- Sumner, A. (2005). Is foreign direct investment good for the poor? A review and stocktake. Development in Practice, 15(3/4), 269–285. doi:10.1080/09614520500076183

- Tsai, P., & Huang, C. (2007). Openness, growth and poverty: The case of Taiwan. World Development, 35(11), 1858–1871. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2006.11.013

- Ucal, M. Ş. (2014). Panel data analysis of foreign direct investment and poverty from the perspective of developing countries. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 109, 1101–1105. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.12.594

- United Nations. (2018). Sustainable development goals. Retrieved May 6, 2018, from https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals.

- Uttama, N. P. (2015). Foreign direct investment and poverty reduction nexus in South East Asia. In J. Silber (Ed.), Poverty reduction policies and practices in developing Asia (pp. 281–298). Asian Development Bank and Springer International Publishing AG.

- World Bank. (2016). World development indicators. Retrieved December 22, 2016, from http://www.data.worldbank.org

- Zaman, K., Khan, M. M., & Ahmad, M. (2012). The relationship between foreign direct investment and pro-poor growth policies in Pakistan: The new interface. Economic Modelling, 29, 1220–1227. doi:10.1016/j.econmod.2012.04.020