?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Regional Trade Agreements (RTAs) have been advocated as one way of securing trade liberalization by the IMF and World Bank. The study uses the gravity model of bilateral trade flows to empirically investigate the effects of RTAs on intra-regional trade on a set of 46 Sub-Saharan African (SSA) countries during 1995–2011 period. Our results indicate that three of the four selected RTAs have positive and statistically significant effect on the trade among the sub-Saharan African countries. Other included variables including distance, common language, shared border, shared colonial links, and common currency are found to be important determinants of trade among SSA countries.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) countries are characterized by low GDP levels and small populations leading to low per capita income levels. Due to SSA countries small domestic markets, trade can be a successful strategy for fostering their growth and inclusive development as it is positively correlated with flows of investment and technology. This study finds that SSA countries who are members of a Regional Trade Agreements (RTA) trade more among themselves that they do with other countries from SSA who are not RTA members. The study also finds that SSA countries who share a common language, borders, colonial links, and common currency trade more amongst themselves than they do with other SSA countries while distance reduces trade among SSA countries. RTAs should, therefore, be supported as they provide an avenue for SSA countries to reduce their size constraint and increase economies of scale when producing goods and services.

1. Introduction

Trade may be accepted as a key engine of economic growth for most countries. In theory, trade can impact positively on a country’s rate of economic growth. Trade is positively correlated with flows of investment and technology while fostering competition and a more efficient use of resources. Also, specialization in sectors of comparative advantage permits better allocation of resources, allowing the realization of economies of scale and the production of goods at cheaper costs.

Export promotion as a commercial policy issue has, therefore, attracted considerable attention in many countries as many policymakers argue that its development is a successful strategy for fostering growth and inclusive development. African countries have not been left behind in the era of globalization and liberalization with the importance of exports been emphasized as the way to widen these countries markets beyond the size of their local market.

Regional trade agreements (RTAs) have been advocated as one way of securing trade liberalization with the IMF and World Bank being its big advocate as they are considered to be less cumbersome to negotiate than multilateral trading agreements since there are fewer parties and they sometimes result in trade creation. RTAs have also been found to be more flexible when compared to other agreements with regard to areas of coverage as they often include investment, competition and other areas. Also, members with similar interests and common values are able to include them when negotiating within the RTAs. The main criticism against RTAs is that sometimes they can result in trade diversion.

Although the main objectives of RTAs are to promote economic development through increases in intra-industrial trade, some scholars have questioned if these integration agreements create positive impact on Africa’s regionalization process or the extent to which they have contributed to the enhancement of intra-regional trade. As noted by De Melo (Citation2013), studies related to African RTAs on the link between integration, trade, and economic growth have not had conclusive results mainly because of identification problems related to high growth volatility including internal and external economic shocks. The present paper is an attempt to fill that gap and address the effects of RTAs on intra-regional trade using the gravity model of bilateral trade flows using a set of panel data of 46 SSA countries during 1995–2011 period.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses the current status of RTAs in Africa. Section 3 briefly reviews the gravity model of trade and presents specification of the regression model to be tested. In Section 3, an outline of data and variables included in the estimation of the gravity model are shown. In Section 4, we present the results of our estimation and finally we conclude in Section 5 and suggest policy recommendations including lines for further research.

2. Literature review

2.1. RTAs in Africa

Two decades after the Second World War has witnessed profound developments in international trade as experienced by dramatic increase in RTAs. According to World Trade Organization (Citation2013), between 1948 and 1994 there were only 124 RTA notifications and after the creation of World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995 the number has more than tripled, with an additional 400 notifications (WTO, Citation2013). RTAs have been a major potential source of enhanced trade and investments, economic efficiency, and growth.

SSA countries are characterized by low GDP levels and small populations leading to low per capita income levels and small domestic markets. In 2010, 19 SSA states had GDPs of less than US$5 billion with six having a GDP of less than US$1 billion while 12 states had a population of less than 2 million people. Most SSA countries are not only small and poor but 15 of them are also landlocked which contributes to high costs of doing business within the region. The small SSA countries domestic markets and continental fragmentation has translated into lack of economies of scale in production and distribution of goods and services. The foregoing when combined with low per capita densities of rail and road transport infrastructure including lack of skills and capital to establish and operate sophisticated modern communication systems has resulted in increased transaction costs for trade (Hartzenberg, Citation2011).

As a result of the aforementioned challenges, African continent has made significant progress in opening up their economy to external competition through trade and exchange rate liberalization, often in the context of IMF and World Bank’s support programs especially since the early 1990s. The continent has created its own share of RTAs that have been championed by Regional Economic Communities (RECs) as the continent moves towards the formation of the African Economic Community (AEC) that was established by the Abuja Treaty of 1991(Chiumya, Citation2009). The continent now has 30 RTAs or trade blocs, many of which are part of deeper regional integration schemes. In SSA, some RTAs have contributed significantly to structural reform by creating incentives for removing restrictive trade practices and licensing procedures, streamlining customs procedures and regulations, integrating financial markets, simplifying transfers and payments procedures, and harmonizing tax treatment.

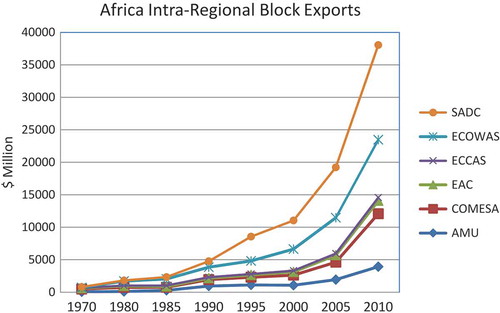

In a few instances, African countries have gone even further, seeking to harmonize investment incentives, standards, and technical regulations, as well as policies relating to transportation, infrastructure, labour, and immigration. The benefits such reforms provide to regional partners is expected to spill over into more efficient and equitable treatment of all trading partners and thus contribute to a more favourable economic environment, including investment. This has led to boost intra-African trade as depicted by Figure (see appendix for list of countries).

One of the major benefits of RTAs is that they allow African countries to pool their scarce resources in order to increase their collective market size, increase capacity, coordinate/rationalize their economic and industrial policies, and improve their appeal to local and foreign investors. Regionalism, therefore, provides an avenue for African countries to reduce their size constraint and attendant costs.

In the neoclassical economic view that trade is an engine of growth, regional integration acts as a catalyst for economic development of Africa through boosting intra-African trade. The static gains that are likely to accrue to African countries through RTAs can catalyse their individual and collective development. Because most African especially neighbouring countries engage in similar if not competitive production, the resultant trade creation will not only increase trade but also spur ancillary economic activities, create new job opportunities, kindle economic growth, raise standard of living standards, and ultimately economic development.

One of the challenges that have been associated with the underdevelopment of Africa is its low industrial base which is critical to economic development. This problem is typically associated with the absence of economies of scale and the presence of protective barriers at the national frontiers. Regional integration can thus encourage higher research and development (R&D) spending and enable new economies of scale from large-scale production (e.g. manufacturing sector) to flourish in Africa. Such large-scale production of (semi) finished goods on the continent can, in turn, help African countries to reduce their individual and collective dependence on the exports of price inelastic primary commodities. The effects of new economic activities can thus advance Africa’s economic growth and development.

One of the biggest challenges for many African countries is the adoption of inappropriate anti-competitive transport policies that have led to inflated transport and export costs which act as a deterrent towards inter-regional and international trade. Coupled with this is inadequate investment in transport and communication infrastructure which continue to hinder trade flows within SSA RTAs (Yeats, Citation1999).

Another challenge facing Africa’s RTAs in implementing their integration programmes has been their overlapping membership. Citing the case of Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), East African Community (EAC) and Southern African Development Community (SADC) RTAs, UNECA (Citation2013) report notes that while EAC is already a common market, it shares four member states with COMESA and one member state with SADC. Meanwhile, five SADC member states are members of Southern African Customs Union (SACU). The reports further notes that ten countries in the region are already members of customs unions, but all of them are also in negotiations to establish alternative customs unions from the one they now belong to. Also, COMESA and SADC RTAs have seven member states in common who are not part of a customs union but are preparing their own customs unions. Thus, of the 26 countries in COMESA, EAC and SADC RTAs, seventeen of them are either in a customs union and negotiating to enter an alternative customs union to the ones they belong to, or are negotiating two separate customs unions. These similar trends are also common among members of RTAs in the Western and Northern Africa although to a lesser degree when compared to the other regions, see Figure .

Figure 2. Overlapping REC membership for African countries.

Source: UNECA, Assessing Regional Integration Report II.

Most African RTAs economic performance has, therefore, been below the expectations of member countries as a result of below-potential market integration which is a reflection of the existing high trade barriers. Studies have shown that African RTAs trade on average 40% less than potential trade (i.e. trade in a frictionless world) and the ratio of actual to potential trade, which is thought as a proxy for trade costs has remained high for most RTAs except for the East African Community (EAC) which fell from 0.63 2 years before the RTA implementation to 0.53 7 years after the RTA implementation. However, even when we consider the forgoing, the potential benefits of deep-integration of RTAs in SSA when combined with political benefits is immense and can greatly enhance inclusion of SSA economies into the global value chains (De Melo and Tsikata (Citation2013).

3. Model and data specification

3.1. The gravity model

The gravity equation is an empirical model that has been used to analyse bilateral trade flows between two countries. The gravity model for trade is anchored on Newton’s gravity law in mechanics, which states that the gravitational pull between two physical bodies is proportional to the product of each body’s mass divided by the square of the distance between their respective centres of gravity. This analogy has been translated in trade to mean that flow of trade between two countries is proportional to their economic “mass” as measured by a product of their national incomes and inversely proportional to the distance between the countries’ respective “economic centres of gravity”, generally considered as their capitals. Early proponents of the gravity model specified the basic gravity model equation as follows:

Where Tij is the value of trade between country i from country j and Yi and Yj are country i and j’s respective national incomes. Dij is a measure of the distance between the two countries’ economic centres or capitals and k is a constant of proportionality. β and γ parameters sign are hypothesized to be positive while δ sign is hypothesized to be negative.

After we take logarithms on the gravity model equation as in (1) it is possible to obtain a linear form of the gravity model equation which can be represented as follows:

Where α, β, γ and δ are the coefficients to be estimated. The error term (uij) captures any other random events that may affect trade between the two countries and is predicted to have a mean of zero and constant variance.

In addition to the basic model (2), an augmented gravity model equation is estimated which includes several conditioning variables that account for bilateral trade over and above the natural logarithms of income and distance. To capture the impact of other variables that influence bilateral trade, most gravity models add to (2) some dummy variables that test specific effects. If we assume for k distinct effects, the basic model summarized as:

Which is equivalent to:

Where Zkij represents a vector of dummy variables including shared border, shared language, shared colonizer, shared RTA, being landlocked, etc. The dummy variables are binary with Zk = 1 for a criteria and zero otherwise.

Studies conducted using the gravity models of international trade have yielded consistent high and statistically significant results that carry the expected signs for both income and distance variables. The results have also shown high R2 thereby explaining considerable proportion of bilateral trade among countries and making it a successful empirical tool for evaluating bilateral trade among countries. Other studies have used the gravity model to evaluate trade policy issues including the impact of protectionism and openness (Harrigan, Citation2003; Wall, Citation1999)

Frankel, Stein, and Wei (Citation1995) used the gravity model to evaluate the contribution of RTAs while Saxonhouse (Citation1993) has used it to analyse regionalization trends. Other studies have analysed the role of national borders and non-member countries in enhancing inter-regional trade using the same model (Anderson & Van Wincoop, Citation2003; Wakasugi & Itoh, Citation2003). As noted by Sohn (Citation2005), the gravity model has also been extended to explain the patterns of non-trade policy issues such as migration flows, bilateral equity flows, and foreign direct investment flows putting it at the centre of applied researches on international trade of the day. However, Ram and Prasad (Citation2007) argues that the gravity model does not make provision for third party effects that can influence trade countries when analysing bilateral trade between country X and Y, i.e. the model does not take into account conditions and opportunities that prevail between countries X and Z and countries Y and Z.

In the study, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is a separate independent variable since it is considered a good indicator of a country’s level of development. The study assumes that as a country develops, its citizens will also demand to consume more exotic foreign goods that might be considered to be more superior to those produced domestically therefore increasing the level of imports. In addition, as the country develops, it is expected that there will be more innovation that is domestic or invention of new products that will act as exports to other countries thereby enhancing regional trade. It has also been true that as countries develop, they gain ability to create efficient transportation infrastructure that can positively facilitate trade.

Another variable considered in the study is transportation cost. The presence of transport costs ensures that factor-price-equalization theory does not hold in the production of the same good in two or more countries. Studies have shown that trade models behave differently when transport cost and differences in demand across countries are included (Paas, Citation2000). In the study, distance (D) is a proxy for transport costs as the distance between two countries is expected to determine the volume of trade between them. Three kinds of costs that have been associated with doing business at a distance and among them top has been the physical shipping costs. This followed by time-related costs and costs of (cultural) unfamiliarity. Among the three costs, physical shipping costs seem to be the most crucial (Frankel et al., Citation1995).

Another variable used in the study is shared border (Bordij). The study assumes that, just like in distance, countries that share boundaries engage in more trade because of shorter distance, shared culture, and common language, among other things. A dummy variable is used to identify if a pair of countries share a border with one (1) indicating that countries i and j share a common border and zero (0) when they do not.

Common language (Langij) between two trading partners is expected to reduce transaction costs since speaking the same language helps facilitate trade negotiations. As most African countries inherited the languages of their colonizers, common language can also lead to common values and tastes that further enhance trade between countries. In the study, a dummy variable is used and one (1) denotes when countries share a common language (official or commercial) and zero if otherwise.

Also, shared colonial links (Colij) is expected to reduce transaction costs that arise due to cultural differences and can also lead to shared common values. In the study, a dummy variable is used to denote a common colonizer between two trading partners with one (1) indicating country i and j were colonized by the same country and zero (0) if otherwise.

Landlocked (LLij) countries in Africa face many challenges caused by lack of infrastructure development that has led to poor integration of the economies. In Africa, trade volumes between landlocked countries are 20% less than trade among countries, which are not landlocked. The study assumes that there is more trade between landlocked and non-landlocked countries than among landlocked countries. The dummy variable is used to denote one (1) where either country i and j is not landlocked and zero (0) if both countries are landlocked.

Exchange rates play an important influence on trade patterns. Majority of SSA countries linked to the US dollar and experience greater exchange rate volatility since their economies overly dependent on relatively few raw commodity exports, which have continued to face high price volatility and a declining trend of real prices (Nkurunziza, Tsowou, & Cazzaniga, Citation2017). It is expected that two countries with the same currency, (EXRij), trade more than comparable countries with their own currencies since substituting a single currency for several national currencies reduces the transactions costs of trade within that group of countries (Rose, Citation2000). The study hypothesis that countries linked to common currency will have greater exchange rate stability and, therefore, trade more. In our sample, 14 countries have same currencies. The dummy variable is used to denote one (1) where both country i and j share a common currency and zero (0) if zero (0) if otherwise.

The reason why a country enters into regional trade agreements (RTAij) is to foster bi-lateral trade with other members in the region. Therefore, countries within an RTA will trade more among themselves than with other countries who are not members of the same group (Frankel & Rose, Citation2002). The dummy variable for RTA is equal to one (1) where either country i and j belong to the same RTA and zero (0) if otherwise.

Uij is a log-normally distributed error term and represents other variables that effect bilateral trade between African countries. It is expected that E (lnUij) = 0.

3.2. Sample size and data issues

The study covers 46 African countries from SSA for a period of 1995–2011 (17 years) as shown on Table . Selection of the countries and period is based on the availability of data. Data on GDP, GDP per capita, and population are obtained from the World Development Indicators (WDI) database of the World Bank. Data on exports of goods and services for African countries (country i’s exports) to all other countries (country j) are from United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNTAD).

Data on the distance (in kilometres) between the capital cities for the different African countries are obtained from mapcrow.com, a distance calculator website. Data on common language are obtained from nationsonline.com website while data on former African countries colonizers obtained from about.com website. Data on shared border, landlocked, and membership of a particular RTA, are compiled by the authors. GDP per capita calculated in current US dollars, just as was total exports and total imports while population of all countries considered in millions. Table presents descriptive statistics of variables included in the study.

Table 1. Summary of membership of African RTAs

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for core variables used in regressions

4. Empirical results

The empirical analysis in the present study involves a set of cross section and pooled regressions where bilateral trade between two countries is regressed on GDP per capita, trade agreements, and other determinants. For the cross-section analysis, data divided into 5-year averages of three different groups that were estimated over the period 1995–2009 and 2-year group for 2010–2011 period. Final application is a pooled regression model like regular cross-sectional data, except that procedure includes dummies to account for movements between different points in time.

The objective of the present study is to test factors of bilateral trade in Africa. Especially focusing on cross-section data averages at one period is much necessary to determine importance of RTAs in SSA. Therefore, present study prefers cross-section OLS over a panel or a dynamic panel data model that is using generalized method of moments (GMM).

The statistical analysis of panel data becomes more difficult when one assumes that the observations are independently distributed across time. Then the study may have an issue of serial correlation of regression residuals. One additional issue may be that unobserved factors may perhaps behave differently on different cross-sectional components, but through time, they may have a long-term result upon the exact statistical component.

Regarding dynamic panel of GMM, Judson and Owen (Citation1999) argue that efficiency of GMM relies on generating instruments, which needs many observations due to many degrees of freedom. We believe that this is out of scope of the present study. Looking for a good number of instruments and analysing them correctly to overcome a common problem of over identification is a different type of study. One more final addition to dynamic panel GMM is that current study has small number of variables with some fixed and dummy variables. These variables do not vary over time, therefore no additional explanations added to further argument in present study.

4.1. Cross-section results

Table displays results for three 5-year averages and one 2-year averages cross-section regressions. The first column starts with interval for 1995–1999 period, the second column is the 2000–2004 period, the third column is 2005–2009, and column four is for the 2-year 2010–2011 interval. On average, all models succeeded in explaining about 52% variation of the dependent variable. In addition, all models passed the F-test for overall significance. As expected, GDP has positive impact on trade levels between SSA countries in all four regressions and was statistically significant at 1% level. However, contrary to our expectations, GDP per capita had a negative sign and was significant at 1% level in all four models. One may explain the negative GDP per capita coefficient sign to infer that as GDP per capita or living standard of SSA countries increases, consumers prefer to trade from different sources than SSA perhaps due to high degree of similarities in their economic structure as exhibited by exports of undifferentiated raw commodities.

Table 3. Cross-section OLS results

The results of the study show that the other important determinant of trade among SSA countries is distance. As was expected, distance had the expected negative sign that was significant at the 1% level in all included models. For instance, the study results revealed that a 1% increase in distance induces a decrease in trade level among SSA countries by around 1.04%.

Table results show that the dummy variables included to reflect characteristics of SSA countries were all positive and statistically significant at either 1 or 5% level of significance in all the considered models. The results of language dummy suggests that if countries share a common language, their trade level will be higher by an average of 0.54 than their trade with countries whom they do not share a common language when other things are held equal. Border was another dummy variable that had a positive and statistically significant sign as was expected. This suggests that if SSA countries share a common border, they will have a higher levels of trade than with those of whom they don’t share a border with. The same was true for colonial links variable which had a positive and significant sign.

According to our results, SSA countries tend to trade more with countries they share similar colonial links than they do with those countries whom they do not have common colonial links, when all other variables are held constant. The common currency dummy is also positive significant at 1% level. This affirms that SSA countries which share the same currency trade more than they do with other countries whom they don’t share common currency, holding other variables constant. The only dummy variable which was not statistically significant in all of the five models was being landlocked. This suggests that in SSA being landlocked is not a significant determinant of how much a county trades with other regional countries.

Finally, the findings of our models show that three of the four major RTAs that were considered had a positive impact on trade among SSA countries. COMESA, ECOWAS, and SADC had positive and significant impact on trade while ECCAS RTA was found to have a negative coefficient that was not significant in all models. One of the reasons why ECCAS RTA does not positively enhance trade would be due to the political and social conflicts in the region as six of the eleven members are post-conflict countries while other members are landlocked, forested and sparsely populated fragile states (WTO, Citation2013). The positive and significant RTAs results are not surprising as one of the major benefits expected to accrue from being a member of a trade agreement is enhanced trade. The results from the study show that, on average, countries that belong to COMESA, ECOWAS, and SADC RTAs are expected to have trade levels of around 1.18, 1.76, and 1.4 percentage points more among themselves, respectively, than when compared to their trade with countries who are not members of these RTAs.

4.2. Pooled results

The fifth column in Table displays the results for the same models when they are pooled together to test if the study results were consistent. As the table shows, the pooled regression model reveals that the study succeeds in explaining almost 47% of the variation in trade among SSA countries. The pooled regression model results are consistent in terms of signs and direction when compared to the results of the other four cross section models, although the magnitude of the variables coefficients in pooled regression are higher than those of cross section coefficients. For instance GDP coefficient is almost twice as the one shown in column one.

5. Concluding remarks

It is widely accepted that RTAs facilitate higher levels of trade among member countries. The results from the study strongly suggest that SSA countries that belong to a trade partnership will enjoy more imports and exports from member countries than from other SSA countries. This is perhaps not completely unexpected given the incentives and other benefits accrued when nations that enter into trade agreements and these effects point out strongly in our data.

The results of the study also affirm that regional characteristics including distance, shared border, shared common language, shared colonial links, and having a common currency play an important role when countries pick their partners for either export or import. The results on common currency are particularly important given the foreign exchange rate volatility challenges experienced by SSA economies who are overly dependent on relatively few raw commodity exports which continue to face high price volatility and a declining trend of real prices which has resulted in imported inflation, diminishing foreign exchange reserves, and large swings in the terms of trade (Nkurunziza et al., Citation2017). A common currency will result to greater exchange rate stability. These benefits are compounded when countries join into regional agreements. Bearing these in mind, SSA countries may adjust their political and trade policies accordingly.

The results from the study have opened opportunities for possible future research on the influence of other cultural characteristics on trade in SSA countries. Also, the low infrastructure development in SSA could inform a study which incorporates economic activities between SSA ports, which offers cheaper transport costs compared to land based transport.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

John Kagochi

John Kagochi is an Associate Professor of Economic Development at University of Houston-Victoria. His primary teaching interests are economic development and business statistics. His research interests are diverse and include international trade and competitiveness, regional economic development, and the role of domestic institutions on economic Growth.

Nazif Durmaz

Nazif Durmaz is an Associate Professor of Economics at University of Houston-Victoria. He received a PhD in Applied Economics from Auburn University, Alabama. He mainly teaches Managerial Economics, Business and Economics Statistics, Capital Markets, and Business Finance. His research interests are in Open Economy Macroeconomics, Empirical Financial Economics, International Economics and Trade, and Time Series Econometrics.

References

- Anderson, J. E., & Van Wincoop, E. (2003). Gravity with gravitas: A solution to the border puzzle. American Economic Review, 93(1), 170–192. doi:10.1257/000282803321455214

- Chiumya, C. (2009). Regional trade agreements: An African perspective of challenges for customs policies and future strategies. World Customs Journal, 3, 2.

- De Melo, J. (2013). Regional trade agreements in Africa: Success or failure? IGC Working Paper.

- De Melo, J., & Tsikata, Y. (2013) Regional integration in Africa: Challenges and prospects. mimeo, a commissioned paper for the forthcoming OUP Handbook of Africa and Economics.

- Frankel, J., & Rose, A. (2002, May). An estimate of the effect of common currencies on trade and income? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 437, 466.

- Frankel, J., Stein, E., & Wei, S. J. (1995). Trading blocs and the Americas: The natural, the unnatural, and the super-natural. Journal of Development Economics, 47(1), 61–95. doi:10.1016/0304-3878(95)00005-4

- Harrigan, J. (2003). Specialization and the volume of trade: Do the data obey the laws? In E. K. Choi & J. Harrigan (Eds.), Handbook of international trade (pp. 85–118). London: Blackwell.

- Hartzenberg, T. (2011). Regional integration in Africa. Staff Working Paper ERSD-2011-14. World Trade Organization Economic Research and Statistics Division.

- Judson, R. A., & Owen, A. L. (1999). Estimating dynamic panel data models: A practical guide for macroeconomists. Economics Letters, 65(1), 9–15. doi:10.1016/S0165-1765(99)00130-5

- Nkurunziza, J. D., Tsowou, K., & Cazzaniga, S. (2017). Commodity dependence and human development. African Development Review, 29(1), 27–41. doi:10.1111/1467-8268.12231

- Paas, T. (2000). The gravity approach for modeling international trade patterns for economies in transition. International Advances in Economic Research, 6(4), 633–648. doi:10.1007/BF02295374

- Ram, Y., & Prasad, B. C. (2007). Assessing Fiji’s global trade potential using the gravity model approach. School of Economics, the University of the South Pacific, Suva, Fiji.Working Paper 2007/05.

- Rose, A. K. (2000). One money, one market: The effect of common currencies on trade. Economic Policy, 15(30), 8–45. doi:10.1111/1468-0327.00056

- Saxonhouse, G. R. (1993). Trading Blocs and East Asia. In J. De Melo & A. Panagariya (Ed.), New dimensions in regional integration (pp. 388–416). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sohn, C. H. (2005). Does the gravity model explain South Korea’s trade flows?*. Japanese Economic Review, 56(4), 417–430. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5876.2005.00338.x

- United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA). (2012). Assessing regional integration in Africa V: Towards an African continental free trade area. Addis Ababa: ECA.

- Wakasugi, R., & Itoh, K. (2003, September 19-20) “How do regional trade agreements affect exports and foreign production of non-member countries?” 3rd APEF International Conference, Keio University, Tokyo.

- Wall, J. H. (1999). Using the gravity model to estimate the costs of protection. Federal Bank of Saint Louis Review, 81(1), 33–40. January/February.

- World Trade Organization (WTO). (2013). Regional trade agreements: Facts and figures 2013. Geneva: WTO.

- Yeats, A. (1999). What can be expected from African regional trade arrangements? Some empirical evidence. Washington D.C.: World Bank.