Abstract

This paper is the second paper in a series of papers on Community Economic Development Strategic Framework for Poverty Alleviation in Local Government with particular attention to the Raymond Mhlaba Local Municipality (RMLM). The objective of this paper is twofold: (i) to examine the rationale for community economic development in contemporary philosophy for poverty reduction and (ii) to develop an analytical framework for community economic development for alleviating poverty. It uses existing statistics and research data from Statistics South Africa and other indexes cushioned with over 100 research papers to generate data for this argument. Theme and narrative analysis were used to analyse the data for this paper. In conclusion, the paper demonstrated that for poverty to be alleviated—local investments, buying locally made products, patronising local shops and spaza shops, local regeneration, local reconversion, community linking, and building sustainable capital and market in communities are integral for the survival of any community that intends to be economical viable or sustainable. It recommends that one of the ways in which community viability or sustainability may be guaranteed is through regeneration/reconversion policy and a framework that articulates and harmonise sustainability issues and localisation challenges of communities in each locality.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The idea of collective action in solving communal problems is diminishing. The overdependence on government intervention and the feeling of entitlement has eaten deep into the fabrics of the South African society, especially in black communities. It is for this reason, that this study re-engineers the principles for participation in community development. In this paper, we see community economic development as a means through which a community could grow and flourish, thereby bringing about investment, trade, and prosperity. These in essence will help ensure that the economy is viable, and secondly, it may lead to the reduction of poverty in the community. Hence, it has been documented else that where the economy is viable, opportunities for employment and innovation tend to increase, which in turn affect the rate and intensity of poverty in a given area. Therefore, in this paper, we proposed and analysed a framework for community economic development engagement.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

1. Introduction

The excitement that triggered post-1994 elections was short lived in South Africa (Caromba, Citation2015, p. 213), as the expectations of what democracy presupposes to deliver were deferred. This is not to say that the democracy was delayed but that the apartheid system had severe shortcomings—systemic, structural, social, environmental, political and otherwise, which hindered and limited the capabilities of black South Africans on the one hand and harm the confidence, pride and self-worth of the blacks South Africa on the other (Patel, Citation2017). Another critical harm to the black communities was the invisibleness or absence of government’s presence in the black hinterlands (Mariotti & Fourie, Citation2016; Pillay, Citation2015; Mda, Citation2010).Footnote1 The notion that government presences in black communities were poor and reckless, presupposes that black communities were neglected from all basic amenities for livability, sustainability and wellbeing.

One of the effects of this neglect was a heightened poverty rate fuelled by the seizure of lands and properties of blacks in the territory now referred to as the Republic of South Africa (Bhorat & Kanbur, Citation2005; Viljoen & Sekhampu, Citation2013; Westaway, Citation2010). Therefore, those who fought for independence of the country had some preconceived notions and expectation of the post-colonial entanglement. Among other things were the need to increase government presence in black communities by the construction of the three fundamentals for development, schools, hospital, and markets as a means to reduce poverty, deplete the inequality ratio, break the class structure, and absorb the millions of young black people in vulnerable conditions to positions of power (Gous, Citation2018; Padayachee & Desai, Citation2013; Saul & Bond, Citation2014). Twenty-three years in democratic South Africa led by blacks, one may argue that though the political and social structure might have changed significantly the economics of the nations largely is within the prowess of the white minority (Anwar, Citation2017; Mahlangu, Citation2017; Patel, Citation2017; Van Wyk, Citation2005). In that, a majority of the conundrums of the Apartheid system still lingers as racism, inequality, unemployment and poverty (Lund, Citation2008, p. 1).

Most communities except black communities in history are built upon certain strategies and mechanisms to encourage sustainability (Agyeman, Citation2005; Kong, Citation2012; Maliene, Howe and Malys, Citation2010)Footnote2; however, African communities globally have never had this opportunity.Footnote3 Although the intent of the Bill relating to Black Economic Empowerment was to ensure this, it was, however, truncated because most beneficiaries of the BEE never resided nor invested in their local community to boast local economy.

From the United States of America, the United Kingdom, and the Caribbean’s to Africa, there has been a gap in sustainable community networks for black communities, community organisations and businesses. In most black communities, including in South Africa, there is hardly a mechanism to ensure sustainability of any black commercial venture in history. Although there are several methodologies for creating sustainability and for enhancing economic community empowerment as proposed by Western philosophers and practitioners, some of these developmental recommendations by Western philosophers for Africa’s growth and development would include but not limited to the catch-up plan, assimilation, adjustment models, and millennia among others ((Bretton Woods Project, Citation2001; Foster, Citation2005; Gumede, Citation2008; Ndaguba, Ndaguba, & Okeke, Citation2016; Welch, Citation2005). It must be noted that these neoliberal policies and strategies for the development of the African continent were conceived with good intentions. However, a critical shortcoming was the non-existence of implementing structure, and the notion that Africa is a country than a continent of 57 independent countries (Mkandawire, Citation2010).Footnote4 Hence, a one-size-fit-all kind of recommendation was inadequate, these developers of the models for Africa’s development overlooked or ignored (Mkandawire, Citation2010).

The notion that the neoliberal models for development ignored or undermined the idea that Africa is neither a city or a country with a single language, Africa (Andrews, Citation2009; Tar, Citation2009), is possibly one of the many reasons for the failures of several Western strategies and programmes to uplift those in poverty from vulnerable conditions. Another reason for the failure of these models for reducing poverty was the nature and height of corruption and inhumanness of Africans on African (Justesen & Bjørnskov, Citation2012). Elite within each political strata often perceives their independent countries as their personal property (see the antecedents of Sani Abacha, Olusegun Obasanjo, Muhammadu Buhari, Jacob Zuma, Paul Biya, Robert Mugage, Faure Gnassingbé and several others). This is to say that corruption within the elite structure in almost all societies on the Africa continent has an effect on the catch-up plans, increased levels of marginalisation, increasing poverty rate and inequality ratio and the general underdevelopment of the sub-Saharan Africa (ActionAid, Citation2015; Bello, Citation2010; Brock, Citation2012). If history has thought us anything with regard to poverty reduction, one thing is certain that for poverty to be eradicated or alleviated, collective action in communities imbedded in the act of community building is a fundamental prerequisite. As such, one of the means for advancing community building, resilience and empowerment, tested in Canada, Greece, the United States of America and the United Kingdom in recent times, is the community economic development (CED).

1.1. Material and method

In research, there is hardly any method that is considered sacrosanct, especially in social research. In social science research, there are two broad methods for gathering information for conducting research—quantitative and at the extreme is qualitative. However, between both methods lies the mixed method, which is a combination of numbers and words, respectively. According to Ndaguba (Citation2018), “there is no one best way/method in social research for conducting research.” However, the entire research is dependent on the ability of the researcher to gather, synthesise and analyse reasonable data for problem solving in a research, which is in support of the research topic and questions (Ndaguba, Citation2016, p. 12; Ndaguba, Nzewi, & Shai, Citation2018). Writing a research methodology is at the epicentre of any scientific research endeavour. A research is made or marred by the research methodologies adopted. Research methodology is one segment of a study that academics, practitioners and funders take seriously. Hence, it gives credence and determines to a large extent the feasibility of achieving both the aims and means in a study. In any case, where the research methodologies are questionable the entire research outcome is questionable.

The modality for gathering data for this paper was principally desktop with search engines as, Catalogue of theses and dissertation of South African Universities (NEXUS); Catalogue of books: Ferdinand Postma Library (North-West University); Chronic Poverty Index; EBSCO EconBiz; Food Agricultural Organisation Database; Google Scholar Index; Statistics South Africa; and World Bank Database. In essence, it has been argued that the bedrock of the desktop research is predominantly the ability to search for reasonable data, synthesise the quality of the data and ensure that the right amount of data is collected and analysed for problem solving, in tandem with the object or question of the paper.

This study adopts an exploratory design method in its analysis by identifying salient factors in CED required to boast trade, investment and improve the spirit of localism and localisation. The desktop research approach used in this study is consistent with both the (quasi) quantitative and qualitative paradigm for collecting data. An average of 100 articles, books, Internet source, and government gazette and other documents were consulted. However, 27 of this material were utilised in answering the objects of this paper.

2. Philosophy of community economic development

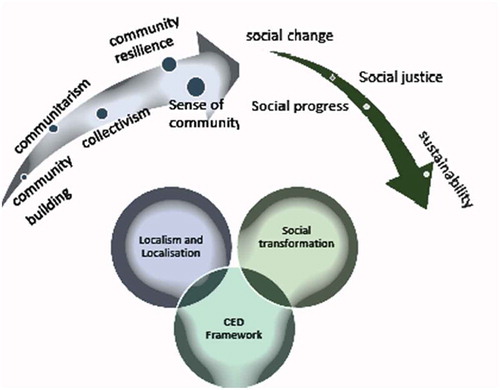

CED is a strategy that provides for community bonding or cohesion vital for community progress. CED houses certain principles through which it argues that local economic development could occur. These would include sustainability, participation, community-based, asset-based, and self-resilience. In addition to the above mentioned, the following concepts are critical in this respect: localism, social transformation, social change, sustainable development, collectivism and communitarianism among others. These principles and concepts are essential ingredients for the successful implementation of CED programmes and projects towards alleviating poverty (Ercan and Hendriks, Citation2013; Moore, Citation2014). Furthermore, the philosophy of CED includes the harmonisation and synchronisation of multi-languages, cultures, and interests towards uplifting or transforming the economics of communities (Tomas, Citation2006). In that, through community engagement in decision-making and problem solving, CED may increase income and create employment for community residents. According to Diamond (Citation2004), CED has the propensity to translate the enterprise of community from junk into a flourishing economy by creating and providing greater opportunities through participation in decision-making and political life in a community.

According to Haggart and MacDonald (n.d.), CED is a process in which communities work together to overcome collective challenges, ensure community bonding, community building and community sustainability of a local economy by diversifying the local economy and creating opportunities. Diversification of local economies is an integral aspect of CED programmes and projects (Haggart and MacDonald, n.d.). The success or failure of any CED strategy is dependent upon the “enthusiasm of a broad representation of community members and community participation” (Haggart and MacDonald, n.d.:iii). However, before CED can transcend into community development that effectively tackles poverty. Consultation with communities and community agencies is certainly of immense priority by stakeholders.

In totality, CED is a fusion of community-driven ideas with an economic development undertone. One of the reasons why this (CED) idea emerged was probably because, it assumed that, where communities claim ownership of certain ventures, businesses, and community interventions and strategies for solving communal problems and dispute. Community participation, commitment, and security of such public goods may be increased, owing to a feeling of a sense of belonging within the community. As Nelson Mandela once noted, “If you talk to a man in a language he understands, that goes to his head. If you talk to him in his language that goes to his heart,” speaks to the heart of CED for alleviating poverty in South Africa. Hence, as stated ab initio, the object of this paper is twofold: to examine the rationale for CED for reducing poverty and to develop an analytical framework for CED for alleviating poverty

3. Rationale for CED for poverty reduction

The Civil Rights Movement is perhaps the greatest example of the power solidarity can have to empower individual people and to change society at-large. Such collective action is important because joining together in solidarity…facilitates community members’ understanding that their individual problems have social causes and collective solutions. (Checkoway, Citation1997, p.15; Tan, Citation2009)

From time immemorial, macro-level social change, progress or transformation had resulted in community development in particular and development in general for one of two reasons: community-driven change creates multiple effect for sustainability or that communal quagmire results in social change. Therefore, one may assume that any attempt at addressing communal challenges or creating an avalanche for economically sustainable communities must be imbedded in the instruments that promote communal growth, collective action and community development rather than individualised growth and development.

Poverty has been a typical example of a collective challenge in African communities, although more prevalent in areas dominated by blacks in South Africa constitutes a reason for joining together in solidarity to fight the menace of poverty collectively.

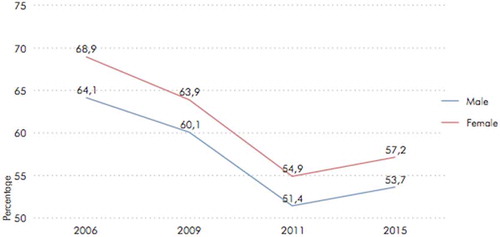

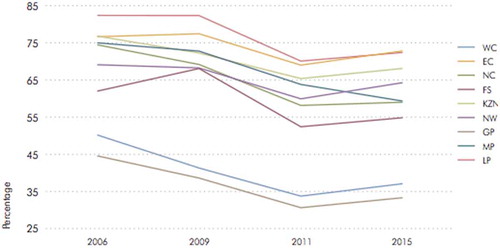

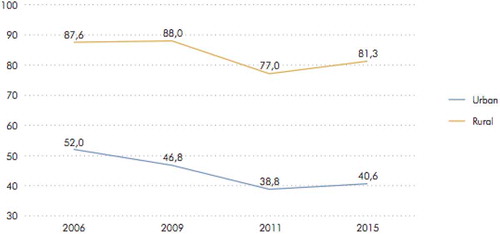

Hence, to tackle the incidence of poverty, only concerted participatory revolution and change through grass-root mobilisation and women empowerment is adequate. This is probably because, in South Africa likewise several Sub-Saharan nations, poverty is mainly located at the rural areas. Plaguing chiefly women and children (see Figures and ).

Figure 1. Poverty headcount by settlement type (UBPL) (2006, 2009, 2011 and 2015).

Source: StatsSA (2017:68).

Therefore, to wage a war against poverty in South Africa and in other Sub-Saharan African countries, one must first understand in relative terms, the underneath causes, cases, factors and the origin of poverty not merely within the country, but within particular communities and tribes. This is simply because, some communities and/or tribes have unique reasons why they have remained in poverty, which is unique to its values and customs.

It has remained arduous to state with all certainty why people fall back into poverty or why they remain in poverty despite opportunities available to them. In South Africa, the government solely and in collaboration with or through several agencies have expended several billions of dollars since 1994 to date in programmes, initiative, projects and processes to uplift the millions of people in poverty, however, between 2011 and 2015 in particular, several millions where expended through grants, community programmes and sensitisation project. However, poverty in both the rural and urban areas in the country was on the rise.

Figures and depict the rise of poverty despite several interventions in rural and urban centres. One should also be aware that why the number of the poor continues to increase, and the number of individualised wealth in the country is also on the rise. This is not to wholly assume that the finances for riding poverty in communities are been used to rid an individual of poverty, but to suggest that community are faring badly because individuals of influence and affluence have transferred communities jobs and opportunities to bigger cities for a bigger reward. The idea described here is that the fight to rid South Africa of poverty must not be individualistic but a collective one. One may argue that the methods, techniques and approaches for community engagement, empowerment and development in reducing poverty in the country are inadequate and antediluvian. In that programmes and projects as the Local Government Turnaround Strategy (LGTAS), the New Growth Path, the National Development Plan, the Millennium Development Plan, the Medium Term Strategic Framework, including such poverty alleviating and empowerment programme as, Accelerated and Shared Growth Initiative of South Africa, Black Economic Empowerment, Community Works Programme, Expanded Public Works Programme among others may be regarded as wasteful exercise, if one is to judge the input against the intended outcome of the project, plan or programme. In that rather than for these initiative, projects and programmes to cause a decline in the number of those in poverty, inversely the levels and intensity of poverty have continued to be on rise since 2011 (see StatsSA, 2018). It is on the basis of the failures of the above-mentioned strategies for poverty alleviation in South Africa that this study develops a strategic framework within the context of CED for reducing poverty in South African rural communities in particular.

CED is a strategy that provides for community bonding or cohesion vital for community progress. CED houses certain principles through which it argues that local economic development could occur. According to Diamond (2004), CED has the propensity to translate the enterprise of community from junk into a flourishing economy by creating and providing greater opportunities through participation in decision-making and political life in a community. Furthermore, Bhengu (nd.) articulated nine key reasons for the need of CED in communities: (1) CED attract progressive private sector investment, (2) CED creates an atmosphere for community bonding and governments investment on infrastructure, (3) CED builds government and private sector investment on skills development, (4) CED reduces the dependency burdens of underdeveloped communities on government handouts, (5) CED links the integrated development planning (IDP) to local economic development (LED), (6) through CED the use of local science and technology (indigenous knowledge) for community development can be prioritised, (7) CED attracts development grants and donor funding from international funders for poverty alleviation, (8) CED facilitates the development of communities through self-reliance at family and community level not individual, and (9) CED enhances collaboration between various development oriented communities, governments, organisations, and progressive private sectors.

4. Analytical framework for CED

The rationale behind community development is the coming together of community member to take collective decision, where government, international organisations and the private sector have failed to solve communal problems (UNTERM, Citation2014). A number of practitioners are engaged within this practice of community development, they may include, activist, civic leaders, professionals and concerned citizens, in a bid to improve the varied aspect of a community that is dysfunctional with the aim of building a more resilient and stronger local economically driven community. Premised on this notion, community development is both a scholarly discipline and a field of practice. According to the International Association of Community Development, community development is “a practice-based profession and an academic discipline that promotes participative democracy, sustainable development, rights, economic opportunity, equality and social justice, through the organisation, education and empowerment of people within their communities, whether these be of locality, identity or interest, in urban and rural settings”.Footnote5 The essence of community development globally and in the South African context is both to empower and mobilise people within communities for problem solving through the creation of certain social groups for public good. In this sense, one may consider community development strategies as an avenue for elevating communities from wanton violence, economic opportunities, and improvement of well-being of a people, through community engagement and community action in areas where the communities are performing poorly.

This section discusses empirical literature that gives credence to the research questions of the study. This literature is within the scope and bounds of the theories that will drive the study. A critical look in the figure below suggests an anomaly in the way community organisations in must remote areas function, silos. This literature review section has two parts: part one deals with community development and the other for social transformation (see Figure ).

4.1. Localism and localisation

The central notion of localism is the concentrating of activities at the local level for the local people. It describes the philosophies that prioritise the localness of the production and consumption of goods and services, promotion of local history, culture, identity and local control of government frameworks. The concept and philosophy of localism is remotely discussed, especially in South Africa. At the conceptual realm of the discourse, it is concerned with the engagement of citizens in the decision that affects them; this can also be seen and understood through the context of deliberative democracy, which in the long run tend to ensure local self-sufficiency (Ercan and Hendriks, Citation2013; Tomas, Citation2006). Localism in principle is strengthened where there is pure and complete devolution in government, because it emphasises the ability of a given people within a community to form a cooperation in order to champion their local development within the community economically (Moore, Citation2014).

Localism creates a sense of local pride and responsibility in the fulfilment of the assignment bestowed upon each one. It is deep rooted in the notion that economic accountability is held equitably and locally, everywhere. The idea of localism can be championed from a commitment to simply buying local to keeping the Rands where the heart lives. This idea tends to support local community in identifying, launching and growing local entrepreneurship, enterprise, and businesses in the locality to serve the community.

According to Wicks (Citation2010), commenting on localism, “at its heart our movement for local living economies is about love.” The assertion of Wick, strikes at the heart of localism, in that, in an article in BALLE, titled, Business Alliance for Local Living Economies. The article argued that localism “recognises that we’re all in this together, and that we are all better off, when we are all well off.” This argument limps into the argument for collectivism, Ghandi’s—self-sufficiency and Martin Luther King—beloved community, which lies beneath the notion of “all for one, and one for all” which is a NATO principle for defence of their allies; this is central for collective bonding. Hence, localism is about building of community on four indicators—equity, health, regeneration, and resilience.

The philosophy and concept of localism can be understood from various dimensions—social, cultural, political and economic dimension. However, for the purpose of ending poverty in South Africa by 2030, the social and economic dimension is what this study would pay significant attention to though to some extent, cultural and political tends to resonate. There are certain peripheral or concepts that are intrinsic in the argument for localism; these may include among others—buy local, local first, local corporation, local entrepreneurship, build local, locally grown, local book news, world’s local bank, local flavour, local food, eat local, local bookselling, real local, self-reliance, community development, community building, community of interest, collectivism, communitarianism, localisation, and localness (Avineri and de-Shalit, Citation1992; Beckert, Citation2006; Block, Citation2008; Christens, Citation2012). All these are intended that there is an established social or cultural affinity to the community where one lives.

4.2. Community building

Community building is one of the several fields of practices directed towards the enhancement of communities within a particular area with common interest. According to Block (Citation2008), some characteristics of community building include possibility, gifts, generosity, rather than problem solving, retribution and fear. Activists’ perspective of community building especially in developed countries are geared towards social integration, increase social justice, reducing the negative impact of disconnected individuals and seeking for individual well-being in the community. However, community building likewise nation building is premised on several beliefs as, ethos, spirituality, human rights, diversity, values and a servant leader (see Oliver Tambo and Musa Yar’Adua).

4.3. Communitarianism

The philosophy of communitarianism emphasises the connection between community development and individual well-being. It is based on the belief that social identity and personality of individuals in communities are largely moulded around the nature of community relationship (Avineri and de-Shalit, 1992). It argues that only a little proportion of the development is placed on the individual. This method of community development gained prominence in the 1980s, although John Goodwyn Barmby coined it in 1841. However, its usage and applicability was limited as a result of its association with socialist and communist ideologies at the time (Beckert, Citation2006; Bell, Citation2016). The central argument for communitarians is that individuals who are well integrated into the community, largely act and reason with intentions that tend to uphold and uplift the community, unlike a community were individuals are isolated (see John Rawls on atomistic individuals).

4.4. Collectivism

Collectivism is a philosophy that suggests collective efforts in the execution or completion of task. The ideology revolves around politics, morals, cultures, socioeconomic, and is ideological in nature. The emphasis is on group interest to individual interest. Collectivism is in direct contradiction to individualism, because while the focus of the former is on collective good, the latter deals with the fulfilment of individual interest either against the collective or another individual (see African corrupt elite).

Literature demonstrates (Triandis, Citation2001, Triandis and Gelfand, Citation1998) that there are two characteristics of collectivism—horizontal and vertical. Horizontal collectivism emphasises equality, cooperation and information sharing, while vertical collectivism emphasises hierarchical approach of the collective to a specific leader or authority (Triandis, Citation2001). The central argument in both horizontal and vertical collectivism is that while horizontal view individual in community has been fundamental more or less equal, vertical collectivism assumes that individuals within communities are fundamentally different and of different social stratification from each other (Triandis and Gelfand, Citation1998). Furthermore, Alexander Berkman farther argued that the equality in horizontal collectivism is not premised on the individuality of persons in the community, but on degree of freedom and opportunity each individual has and is willing to develop and to what extent. This speaks directly to Sen’s capabilities approach in his book Development as Freedom and Martha Nussbaum argument on poverty as a human right abuse (Sen, Citation1999).

4.5. Community resilience

Community resilience takes diverse form in communities, unlike other concepts as collectivism and communitarianism. Community resilience has three layers of interaction for development, namely community, business, and individuals. Thus, the philosophy of community resilience is to empower either one or its three layers through the following way, coming together to identify and support individuals in vulnerable situation, take collective actions towards increasing the resilience of others or that of oneself, and attribute the responsibilities for the promotion of business and individual resilience.Footnote6 Nonetheless, the notion, community resilience is mainly used in disaster and risk management in contemporary studies. However, this paper perceives poverty as a disaster and those in abject poverty as a risk to society. That is to say, for development to transcend the construction of buildings and road networks, the development of human to live meaningful live is critical. According to the Disaster Management Center (Citation2015, p. 9), community resilience may be referred to as the sustained ability of a community to endure and convalesce from difficulty.

The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) describes the “resilience” in the community resilience as

the ability of individuals, communities, organizations or countries exposed to disasters, crises and underlying vulnerabilities to anticipate, prepare for, reduce the impact of, cope with and recover from the effects of shocks and stresses without compromising their long-term prospects. (IFRC, Citation2014, p.5)

The notion derived here is that to understand resilience in terms of community resilience is broader to the individual, business, and community perspective. In that, it involves the participation of several stakeholders in the community, which includes, but not limited to, the individual, household, and community levels, the local, provincial and national government levels, organisations as national societies and non-governmental agencies, and finally regional and global level. The balkanisation of community resilience is critical for understanding both the roles and responsibilities of each participants or users within the entire community resilience framework. The participation of individuals, households, the community, governments at all sphere, NGOs and regional and global role players are paramount in addressing the high rate of vulnerability in communities around the world. This is probably because, it is through participation that individuals and individuals in groups perceive a sense of ownership and belonging, without which, communities cannot be resilient.

4.6. Sense of community

Ownership has a psychological effect on a people’s perceptions and events for community development. Sense of community is within the philosophical discourse of community social work, psychology, social and applied psychology. It is also useful in urban sociology, anthropology, and general sociology. The idea is to understand the philosophy behind how individual’s perceive or understand phenomenon, attitude and feelings about the community and the relationship that helps in promoting growth, unity, oneness, and communal development within a community. To Sarason (Citation1986) it has much to do with the conceptual understanding of asserting oneself in a community.

There are several characteristics of the sense of community, which includes but not limited to, social bonding and physical rootedness (Riger and Lavrakas, Citation1981), greater participation (Hunter, Citation1975; Wandersman and Giamartino, Citation1980), greater sense of perceived control and purpose (Bachrach and Zautra, Citation1985), civic involvement and charitable contribution (Davidson and Cotter, Citation1986), strength of interpersonal relationship (Ahlbrandt and Cunningham, Citation1979), perceived safety (Doolittle and McDonald, Citation1978), and the capability to function ably in the community (Glynn, Citation1981). In essence, a sense of community births a feeling of inclusion and belonging in a community. A feeling of recognition to belonging to a group. And a common believe communism in terms of aspiration and faith. That may lead towards social entrepreneurship and enterprise and a commitment of all-for-one and one-for-all (McMillan and Chavis, Citation1986).

4.7. Social transformation

Social transformation is a process of alterations, alteration in terms structures, behaviours, patterns, and rules of engagement over time, aimed at producing a distinctive social result in the society. In South Africa, several scholars are notable for this role of alteration. They may include, Hanyane, White, Budlender, and Bond among others. White, Budlender and Bond have recognised that poverty in South Africa is: persistent, intergenerational, transmissible and structural. While Hanyane have used the notion of gender and decolonialisation to further the the argument for the persistence of poverty in the country. These scholars (Hanyane, White, Budlender, and Bond) tend to all agree that the political and economic sector of the country has a direct and/or indirect bearing for societal transformation.

4.8. Social change

Poverty is a result of both economic and societal decadence that traps individuals and household from flourishing. Reducing poverty therefore requires a change in society that challenges the social order (race, gender, bondage and caste) and social practices (lower pay for women, debt bondage, child labour and seizing assets of widows) that elevates these factors and traps. Poverty traps are models of self-perpetuating conditionalities whereby an economy is caught in a vicious cycle that suffers from persistent underdevelopment (see Rodney, Citation1971). According to Shepherd, Scott, Mariotti, Kessy, Gaiha, da Corta, Hanifnia, Kaicker, Lenhardt, Lwanga-Ntale, Sen, Sijapati, Strawson, Thapa, Underhill, and Wild (2014:44), there are two cardinal aspects to social change for transformational development—mitigation of intersecting inequalities and the empowerment of disadvantaged individuals and groups. Shephard et al. in there Chronic Poberty report tend to establish the notion that for social change to lead transformation, it is imperative that society neutralise measures that tends to undermine the effort of those in chronic poverty, structurally or otherwise, thereby increasing the possibility of them living well. The Living Well model of development as described by Houtart (Citation2011) and Larrea (Citation2010) in separate studies is at the epicentre of social change. They describe Living Well as the re-foundation of the development models that perceive development as a condition where human beings are at the focal point of the state in opposition to neoliberal theorist; they emphasise a society where reciprocity, harmony and social responsibility thrive, a society characterised by social—equality, solidarity, justice, and the promotion of economic and environmental rights of individuals and groups within society.

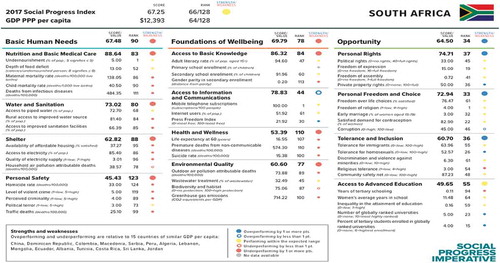

4.9. Social progress

The idea of social progress emanates from the broad notion of the Ideas of Progress, which stresses that any advancement in science, technology, and social organisations ultimately produces an improvement in human conditions (Ludwig, 1967), where people’s quality of life (social progress) can become better through economic development (modernisation), with the application of science and technology (science progress) (Nisbet, Citation1980). It assumes that progress is a process in which people apply skills and reason, and that the role of experts is to identify and neutralise hindrances that slows progress.

According to Salvaris (Citation2000), the notion of social progress is such an important social construct; thus, about 2000 years ago, Aristole considered contextualised it as a “good society” meaning social good. For Osberg (Citation2001), social progress had long been considered from an economic perspective (GDP) in measuring and conceptualising the concept—social progress, until the last for decades (Harris and Burns, Citation2004, p. 1; Salvaris, Citation2000; The Futurist, 1990).

The idea of seeking social progress is intertwined in this study to development and constitutes modalities for ascertaining whether or not poverty is on the decline or increase. The indicators for social progress deal with similar indicators for understanding and measuring poverty in line with the basic needs and multidimensional perspective to poverty. Therefore, an increase or decline of the progress societally made has a great impact in the poverty profile and trajectory of a country. Hence, social progress tends to measure the level of education, level of crime, life expectancy, quality of housing in terms of affordability vis-à-vis income, population growth rate, and young dependency ratio from three perspectives of basic needs, foundations of wellbeing, and opportunity (Harris and Burns, Citation2004, p.4). These indicators take into cognisance theories dealing more with the quality of life theory, which is in response to economic instrumentalist of poverty analysis.

This is because poverty at all times and in all situations cannot be quantifiably verifiable but socially expressed. Thus, the analogy by Osberg (2001) that the GDP is incompetent in distinguishing between growth (an increase in quantity) and development (a total improvement in quality and quantity) raises an alarm several scholars tend to undermine. Figure shows the level of social progress made in South Africa, but for this study selected indicators that deals with basic needs, environment, tolerance and inclusion, and access to basic knowledge will constitute emphasis for the paper in part.

Taking cognizance to the section on basic human needs, one may argue that South Africa is performing below expectation, in which personal safely, shelter, water and sanitation, and nutrition and basic Medicare are in peril. More worrisome is that the indicators that guarantees livability and sustainability are threatened significantly, hence, the need for social re-organisation or change of the entire system and structures in assisting those in poverty, out of poverty. Figure shows that governments programmes, projects and initiatives for addressing poverty in South Africa and the entire Sub-Saharan Africa might have been a wasteful exercise.

4.10. Social justice

The philosophy of social justice is tied to the individuals’ relationship with the society. Hence, Plato in The Republic posited that “every member of the community must be assigned to a class for which he finds himself best fitted” (Plato, ca 380BC). Bhandari, in trying to decipher Plato’s assumption of social justice portrayed thus:

Justice is, for Plato, at once a part of human virtue and the bond, which joins man together in society. It is the identical quality that makes good and social. Justice is an order and duty of the parts of the soul, it is to the soul as health is to the body. Plato says that justice is not mere strength, but it is a harmonious strength. Justice is not the right of the stronger but the effective harmony of the whole. All more conceptions revolve about the good of the whole-individual as well as social. (Bhandari, nd.)

Implicitly, justice is to the soul, as health is to the body, without a functional system of social and administrative justice, a society stand the choice of degrading into anarchy. This notion therefore establishes the assumption that disobedience to established authority in society is a result of unfilled expectations of the society or government in power. In Nicomachean ethics, Aristole emphasised that right existed only for free people and that the law must take cognisance to treat people according to their worth and only secondary in line with inequality. This must be understood that these assertion where made at the peak of the slave trade, and the subjugation of women were normalised. Socrates in Crito developed the concept of social contract, stipulating that individuals and groups have to follow the rules and regulation of a society, and also accept the burdens its bears since they also accepts its benefits (Plato, ca 380 BC). However, Thomas Aquinas was the first to relate the concept of justice to God, by establishing that the ultimate goal of a good citizen is to fulfil the purpose of serving God.

While the concept of Justice in relation to society was long established the concept of social justice itself is credited to Augustine of Hippo, Antonio Rosmini-Serbati, Luigi Taparelli, and Thomas Paine in the 1840s (Clark, Citation2015; Paine, Citation1797.; Zajda, Maajhanovich, and Rust, Citation2006). Thus, social justice is perceived as the just and fair relationship between the individual and the society. To Aristotle (ca 350 BC), Clark (2015) and Bana, Ronzoni and Schemmel (Citation2011), social justice is a process that ensures that individuals in society fulfil their societal roles and receive the expectations from society. Social justice as seen in contemporary terms delves into the reinterpretation of historical figures in philosophical debates (see Bartolome de las Casas) in differences among humans and their efforts for racial, gender and social equalities for justice advocacy for prisoners, migrants, the environment, and the mentally and physically challenged individuals in society (Jalata, Citation2013; Smith, Citation2015; Teklu, Citation2010; Truong, Citation2013; Urwin, Citation2014; Wilkinson and Pickett, Citation2010; Xei, Citation2011).

4.11. Sustainable development

Sustainable development is the organising principle of sustainability science. It involves a transdisciplinary approach (ecology, culture, politics, governance, and economics) in safeguarding human productivity away from harm and ill-being (James, Magee, Scerri, and Steger, Citation2015). Proliferation of studies exists that have given a definition to the concept of sustainable development. However, the most adequate for this paper is stipulated in the Brundtland Commission report. The report defines sustainable development as, “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (Le Blanc, Citation2015, p.1; UNGA, Citation1997; UNGA, Citation2012; Brundtland Commission 1987 cited in Redclift, Citation2005, p. 213). Though, there exist several counter arguments to this definition, however, the definition still remains relevant, because, it demonstrates what the notion and philosophy of sustainable development entails, such as the development of a sustainable human society from three critical pillars, environment, economy, and society. Noam Chomsky buttresses the points further thus, “optimism is a strategy for making a better future. Because unless you believe that the future can be better, you are unlikely to step up and take responsibility for making it so” (King, Citation2012, p. 62). Therefore, in the execution of the sustainable development agenda, the strategy for the achievement of its goals must be intrinsic to the core cultural values of the society, the economy and the environment.

It is important to note that the Brundtland Commission reports paved the way for the understanding of sustainable development and gave credence to the science of Future Studies. However, this definition have been criticised on accounts of its vagueness, uncertainties, and confusion (Redclift, Citation1993; 2005, p. 214). Nevertheless, the definition provided a pathway for understanding measures through which the future can be preserved and sustained not measured. As argued by UNECE, the definition and report of the Commission has aided in shaping the “international agenda and the international community’s attitude towards economic, social and environmental development” (Bärlund, Citation2005).Footnote7 Notwithstanding, the instrument that provided a framework for monitoring and evaluating progress towards the realisation of the SDGs was introduced through Article 8.6 of Agenda 21 (United Nations, Citation1992). Although several studies exist that contends for the inclusion of other pillars that are critical in ensuring smooth delivery of the Sustainable Development Agenda and Agenda 21 of the UN, a key and central to the sustainable development agenda is the local people.

5. Conclusion, recommendation and summary

This study demonstrated that for poverty to be alleviated there must be certain initiatives and culture that must be learnt, developed, incorporated and sustained in local and rural areas, among them may include—local investments, buying locally made products, patronising local shops, local regeneration, local reconversion, community linking with bigger markets, social identity of a people, solidarity as a form of social development, and building sustainable capital and market in communities are integral for the survival of any community that wishes to be economical viable or sustainable.

It recommends that the disinvestments in urban centres are also critical for CED and for achieving community springiness and regeneration. This may lead to the undesirability and tertiarisation of production methods in bigger urban centres. However, the first and most important aspect of the notion of CED is embedded in the French journal Pour in Chassagne and Romefort definition of local development—local development is a strategy for survival in distressed regions where they locals believe in the notion that “this cannot go on” “something must be done” (Chassagne and Romefort, Citation1987, p. 251, Fontan, Citation1993, p. 4). Thus, until communities in South Africa begin to perceive that their underdevelopment and backwardness, unemployment and intense poverty is premised on their inability to come together and harmonise their thought towards rebuilding their communities, it will be difficult for anyone from outside the community to ensure that a community is either economically viable or sustainable, because the aim of every business owner or investor is profit driven. Therefore, it is primarily the duty of the communities itself and halfway through the responsibility of government to establish certain laws, enactments and policies, especially for government funded initiatives and ventures in the country.

Taking from the above, another means through which community viability or sustainability may be guaranteed is through a regeneration/reconversion policy framework by the government, establishing laws that gives concession and waivers to industries not Chinese shops located in remote local communities and on the other hand a high taxation for those industries in bigger and urban centres. This has a twofold agenda, first is the depopulation of the urban centres from overcrowding among others and the second is to ensure that communities are economically viable, sustainable and healthy in the long run.

It must be noted that this paper does not cover every aspect of CED for poverty reduction as there may be other means and methods for alleviating poverty in communities. However, it argues that the CED analytical framework is a useful tool for poverty alleviation in rural communities, especially in South Africa communities. In the same regard, we may argue to agree or disagree that no matter how meticulous a research is conducted, the researcher will never be able to cover all the sectors of a topic (whether topical or trivial). However, the most the researcher is expected to do is make the research of scientific merit by ensuring that such a research is valid and reliable. Thus, this paper neither pretend nor does it intends to cover all the sectors relating to CED in South Africa or elsewhere. Nonetheless, it gives strong conviction that CED is a valuable and reliable method for alleviating poverty given the proposed analytical framework. Noteworthy, is that this study is apparently the first to develop an analytical framework for CED for analysis in rural communities in South Africa, and the first to give CED as an avenue for poverty alleviation.

In sum, the development of this analytical framework in this study will assist in articulating and harmonising sustainability issues and localisation challenges of communities in each locality and realign them for development of communities based on their perceive notion of development. In that, the communal challenge in Alice of the Eastern Cape is very different from the challenge of communities in the Potchefstroom area of the North West Province.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

EA Ndaguba

EA Ndaguba specialises in community development, community economic development, peace and security, conflict resolution, corruption, development economics, monitoring and evaluation, development policy, and organisational procedure and design.

Barry Hanyane

Barry Hanyane is presently working as Professor in Public Management and Governance, University of North-west, South Africa.

Notes

1. People of colour particularly black people of Africa.

3. People of African descent, for example, Black, White, Indian or Coloured.

5. “Community Development Journal- about the journal” (http://www.oxfordjournals.org/our_journals/cdj/about.html). Oxford University Press. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

6. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/community-resilience-framework- for-practitioners/the-context-for-community-resilience.

References

- ActionAid Nigeria. (2015). Corruption and poverty in Nigeria: A report. Abuja: ActionAid Nigeria. http://www.actionaid.org/sites/files/actionaid/pc_report_content.pdf

- Agyeman, J. (2005). Sustainable communities and the challenge of environmental justice. New York, NY: NYU Press.

- Ahlbrandt, R. S., & Cunningham, J. V. (1979). A new public policy for neighborhood preservation. New York, NY: Praeger.

- Andrews, L. R. (2009). Neoliberalising Africa: Revealing technologies of government in the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) (Master of Arts). University of Toronto.

- Anwar, M. A. (2017). White people in South Africa still hold the lion’s share of all forms of capital. The Conversation. Retrieved May 5, 2018, from https://theconversation.com/white-people-in-south-africa-still-hold-the-lions-share-of-all-forms-of-capital-75510

- Avineri, S. and de-Shalit, A. (1992). Communitarianism and Individualism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bachrach, K. M., & Zautra, A. J. (1985). Coping with a community stressor: The threat of a hazardous waste facility. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 26(2), 127-141.

- Banai, A., Ronzoni, M., & Schemmel, C. (2011). Social justice, global dynamics: Theoretical ad empirical perspective. Florence: Taylor and Francis.

- Bärlund, K. 2005. Sustainable development - concept and action. UNECE. Retrieved May 10 2018, from https://www.unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/oes/nutshell/2004-2005/focus_sustainable_development.html

- Beckert, J. (2006). "Communitarianism". International Encyclopedia of Economic Sociology. London: Routledge.

- Bello, W. (2010). Does corruption create poverty? Foreign Policy in Focus. Retrieved May 5, 2018, from https://fpif.org/does_corruption_create_poverty/

- Bell, D. (2016). “Communitarianism”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2016 Edition). In Edward N. Zalta (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. CA: The Metaphysiscs Research Lab, from https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2016/entries/communitarianism/

- Bhorat, H., & Kanbur, R. (2005, October). Poverty and well-being in post-apartheid South Africa: An overview of data, outcomes and policy. Development Policy Research Unit (DPRU). Working Paper No. 05/101.

- Block, P. (2008). Community: The structure of belonging. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler.

- Bretton Wood Project. (2001). PRSPs just PR say civil society groups: An update. From issue 23 of The Bretton Woods Update. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank.

- Brock, H. (2012). Marginalisation of the majority world: Drivers of insecurity and the global south. Oxford Research Group. Retrieved May 1, 2018, from www.oxfordresearchgroup.org.uk/publications/briefing_papers_and_reports/marginalisation_majority_world_drivers_insecurity_and_global

- Caromba, L. (2015). Book review: Ubuntu: Curating the archive. Strategic Review for Southern Africa, 37(1), 208–211.

- Chassagne, M., & de Romefort, A. (1987). Initiative et solidarité: I’affaire de tous. Paris: Syros.

- Checkoway, B. (1997). Core concepts for community change. Journal of Community Practice, 4, 11-29.

- Christens, B. D. (2012). Targeting empowerment in community development: A community psychology approach to enhancing local power and well-being. Community Development Journal, 47(4), 538-554.

- Clark, M. T. (2015). Augustine on justice. In T. Delgado, J. Doody, & K. Paffenroth (Eds.), Augustine and social justice (pp. 3–10). Lanham: Lexington.

- Davidson, W. B., & Cotter, P. R. (1986). Measurement of sense of community within the sphere of city1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 16(17), 608-619.

- Diamond, M. (2004). Community economic development: A reflection on community, power and the law. Journal of Small & Emerging Business Law, 8(2), 151-171.

- Disaster Management Center. (2015). Community resilience framework Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka: Ministry of Disaster Management.

- Doolittle, R. J., & MacDonald, D. (1978). Communication and a sense of community in a metropolitan neighborhood: A factor analytic examination. Communication Quarterly, 26, 2–7.

- Ercan, S. A., & Hendriks, C . H. (2013). The democratic challenges and potential of localism: Insights from deliberative democracy. Policy Studies, 31(4), 422–440. doi:10.1080/01442872.2013.822701

- Fontan, J.-M. (1993). A critical review of Canadian, America & European community economic development literature. Quebec: Centre for Community Enterprise.

- Foster, M. (2005). MDG oriented sector and poverty reduction strategies: Les- sons from experience in health. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Gous, N. (2018). SA most unequal country in world: Poverty shows apartheid’s enduring legacy. Retrieved April 4, 2018, from https://www.timeslive.co.za/news/south-africa/2018-04-04-poverty-shows-how-apartheid-legacy-endures-in-south-africa/

- Gumede, V. (2008). Poverty and Second Economy Dynamics in South Africa: An attempt to measure the extent of the problem and clarify concepts. (Development Policy Research Unit Working Paper 08/133). University of Cape Town, Cape Town.

- Glynn, T. J. (1981). Psychological sense of community: Measurement and application. Human Relations, 34(9), 789–818. doi:10.1177/001872678103400904

- Harris, C., & Burns, M. (2004). Seven reports on identification of rural indicators for rural communities - social progress. Canada: Rural Secretariat of Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada.

- Houtart, F. (2011). ‘El concepto de Sumak Kawsai (Buen Vivir) y su correspondencia con el bien comun de la humanidad’. http://alainet.org/active/47004&lang=es Date of access: 02 November 2017

- Hunter, A. (1975). The loss of community: An empirical test through replication. American Sociological Review, 40(5), 537-551.

- Jalata, A. (2013). Indigenous peoples and the capitalist world system: Researching, knowing, and promoting social justice. Sociological Mind, 3(2), 135-142.

- James, P., Magee, L., Scerri, A., & Steger, M. B. (2015). Urban Sustainability in Theory and Practice: Circles of Sustainability. UK: Routledge.

- Justesen, M. K., & Bjørnskov, C. (2012, August). Exploiting the poor: Bureaucratic corruption and poverty in Africa. Afrobarometer 10 years. Afrobarometer Working Papers No. 139.

- King, J. D. (2012). Peace in the midst of Hell: A Practical and spiritual guide to going through the fire (The Book of Life). USA, AuthorHouse.

- Larrea, A. M. (2010). ‘La disputa de sentidos por el buen vivir como proceso contrahegemónico’ in SEMPLADES (Coord.), Los Nuevos Retos de América Latina: Socialismo y Sumak Kawsay. Quito: SEMPLADES.

- Le Blanc, D. (2015). Towards integration at last? The sustainable development goals as a network of targets. Sustainable Development, 23, 176–187. doi:10.1002/sd.1582

- Lund, F. (2008). Changing social policy: The child support grant in South Africa. Cape Town: HSRC Press.

- Maliene, V., Howe, J., & Malys, N. (2010). Sustainable communities: Affordable housing and socio-economic relations. Local Economy, 23(4), 267-276.

- Mahlangu, B. (2017). Most people haven’t benefitted. Business Report – Opinion. Retrieved May 25, 2018, from https://www.iol.co.za/business-report/opinion/most-people-havent-benefitted-8720015

- Mariotti, M., & Fourie, J. (2016). The data revolution in African economic history. Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 47(2), 193–212. doi:10.1162/JINH_a_00977

- Mda, T. (2010). The Structure and Entrenchment of Disadvantage in South Africa. In Snyder, I., and Nieuwenhuysen, J. (Eds.). Closing the Gap in Education? Improving Outcomes in Southern World Societies. Victoria, Monash University Publishing.

- McMillan, D. W., & Chavis, D. M. (1986). Sense of community: A definition and theory. American Journal of Community Psychology, 14(1), 6-23.

- Mkandawire, T. (2010). Constructing the 21st century developmental state: Potentialities and pitfalls. In O. Edigheji (Ed.), From maladjusted states to democratic developmental states in Africa. Cape Town: HSRC Press.

- Moore, M. (2014). Localism, A Philosophy of Government (ebook). Lexington, KY: Ridge Enterprise Group.

- Ndaguba, E. A. (2016). Financing regional peace and security in Africa: A critical analysis of the southern African development community standby force (Master Dissertation). UFH Library. (2017).

- Ndaguba, E. A. (2018). Task on tank model for funding peace operation in Africa – A Southern African perspective. Cogent Social Sciences, 4, 1–20. doi:10.1080/23311886.2018.1484414

- Ndaguba, E. A., Ndaguba, D. C. N., & Okeke, A. (2016). Assessing the global development agenda (Goal 1) in Uganda: The progress made and the challenges that persist. Africa’s Public Service Delivery and Performance Review, 4(4), 606–623. doi:10.4102/apsdpr.v4i4.142

- Ndaguba, E. A., Nzewi, O. I., & Shai, K. B. (2018). Financial imperatives and constraints towards funding the SADC standby force. India Quarterly, 74(2), 1–19. doi:10.1177/0974928418766732

- Nisbet, R. (1980). History of the idea of progress. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Osberg, L. (2001). Needs and wants: What is social progress and how should it be measured? In K. Banting, A. Sharpe & F. St.-Hilaire (Eds.), The review of economic performance and social progress, the longest decade: Canada in the 1990s, Montreal and Ottawa: The institute for research on public policy and centre for the study of living standards (pp. 23-41). Ontario: McGill-Queen's University Press.

- Padayachee, A., & Desai, A. (2013). Post-apartheid South Africa and the crisis of expectation - DPRN four. Rozenburg Quarterly: The Magazine. Retrieved May 1, 2018, from http://rozenbergquarterly.com/post-apartheid-south-africa-and-the-crisis-of-expectation-dprn-four/

- Paine, T. (1797). Agrarian justice. In H. Steiner & P. Vallentyne (Eds.) (2000), The origins of left-libertarianism. An anthology of historical writings (pp. 83–97). Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Patel, K. (2017). Deconstructing ‘white monopoly capital’. Mail & Guardian. Retrieved January 29, 2018, from https://mg.co.za/article/2017-01-27-00-when-a-catchphrase-trips-you-up/

- Pillay, V. (2015). Six things white people have that black people don’t. Mail & Guardian. Retrieved March 15, 2018, from https://mg.co.za/article/2015-02-23-six-things-white-people-have-that-black-people-dont

- Redclift, M. (1993). Sustainable development: Needs, values,rights. Environmental Values, 2(1), 3-20. http://www.environmentandsociety.org/node/5485

- Redclift, M. (2005). Sustainable Development(1987-2005): An oxymoron comes of age. Sustainable Development,13, 212-227.

- Riger, S., & Lavrakas, P. J. (1981). Community ties: Patterns of attachment and interaction in urban neighborhoods. American Journal of Community Psychology, 9, 55-66.

- Rodney, W. (1971). How Europe underdeveloped Africa. London: Bogle – L’ Ouvertur Publications.

- Salvaris, M. (2000). Community and social indicators: How citizens can measure progress. Institute for social research, Swinburne university of technology, Melbourne, Victoria.

- Sarason, S. B. (1986). The emergence of a conceptual center (Special Issue: Psychological sense of community, II: Research and Applications). Journal of Community Psychology, 14(4), 405-407.

- Saul, J., & Bond, P. (2014). South Africa - the present as history. From Mrs Ples to Mandela and Marikana. Suffolk: James Curry and Johannesburg: Jacana Media.

- Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Smith, J. E. H. (2015). Nature, human nature, and human difference: Race in early modern philosophy. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Tan, A. (2009). Community development theory and practice: Bridging the divide between ‘micro’ and ‘macro’ levels of social work. Indianapolis, Indiana: NACSW Convention 2009: October, 2009.

- Tar, U. A. (2009). The politics of neoliberal democracy in Africa: State and civil society in Nigeria. London: Tauris Academic Studies.

- Teklu, A. A. (2010). We cannot clap with one hand: Global socio-political difference in social support for people with visual impairment. International Journal of Ethiopian Studies, 5(1), 93-105.

- The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC). (2014). IFRC framework for community resilience. Geneva: International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies.

- Tomas, M. (2006). Feedback: Transport and climate change — a reply to James Woodcock. International Socialism Journal, 109. http://isj.org.uk/feedback-transport-and-climate-change-2/

- Triandis, H. C. (2001). Individualism-collectivism and personality. Journal of Personality, 69(6), 907–924.

- Triandis, H. C., & Gelfand, M. J. (1998). Converging measurement of horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(1), 118-128. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.1.118

- Truong, T.-D., Gasper, D., Handmaker, J., & Bergh, S.I. (2013). Migration, gender, social justice, and human insecurity. In T.-D. Truong, D. Gasper, J. Handmaker, & S. I. Bergh (Eds.), Migration, gender and social justice: Perspectives on human insecurity. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg. Hexagon Series on Human and Environmental Security and Peace, 9(1), 3-26.

- UNGA. (1997). ‘Programme for further implementation of Agenda 21’. Res. S/19-2, 28 June 1997.

- UNGA. (2012). ‘The future we want’. Outcome Document. UNGA Res. 66/288. 27 July 2012.

- United Nations. 1992. Agenda 21, United nations conference on environment & development. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 3 to 14 June 1992.

- UNTERM. (2014). “Community development”. UNTERM. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- Urwin, R. (2014). Rosamund Urwin: Our prisons are a disgrace to civilised society. EveningStandard. Retrieved Feb 20 2018, from https://www.standard.co.uk/comment/rosamund-urwin-our-prisons-are-a-disgrace-to-civilised-society-9710896.html

- Van Wyk, B. J. (2005). The balance of power and the transition to democracy in South Africa (Magister Hereditatus Culturaeque Scientiae: History). University of Pretoria.

- Viljoen, D., & Sekhampu, T. J. (2013). The impact of apartheid on urban poverty in South Africa: What we can learn from history. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 4(2), 729–734.

- Wang, X., Hawkins, C., Lebredo, N., & Berman, E. M. (2012). Capacity to sustain sustainability: A study of U.S. Cities. Public Administration Review, 72(6), 841–853. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02566.x

- Wandersman, A., & Giamartino, G. A. (1980). Community and individual difference characteristics as influences on initial participation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 8(2), 217-228. doi:10.1007/BF00912661

- Welch, C. (2005). Structural adjustment programs and poverty reduction strategy. Foreign Policy in Focus, 5(14). http://fpif.org/structural_adjustment_programs_poverty_reduction_strategy/ Date accessed: 03 January 2018.

- Westaway, A. (2010, September). Rural poverty in South Africa: Legacy of apartheid or consequence of contemporary segregationism? Conference Paper presented at ‘Inequality and Structural Poverty in South Africa: Towards Inclusive Growth and Development’, Johannesburg, (Vol. 20-22).

- Wilkinson, R., & Pickett, K. (2010). The spirit level. Geography, 95, 149-153.

- Wicks, J. (2010). Protecting what we love. In Costa, T. (eds.). Farmer Jane: Women Changing the Way We Eat. Canada, Gibbs Smith.

- Xie, L. (2011). China’s environmental activism in the age of globalisation. Asian & Policy, 3(2), 207-224.

- Zajda, J., Majhanovich, S., & Rust, V. (2006). Introduction: Education and social justice. Review of Education, 52(1), 9–22. doi:10.1007/s11159-005-5614-2