?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study examines the behavior of firms in Indonesia in relation to the life-cycle and catering theories under the assumption that investors expect optimum returns on stock investments through dividends, capital gains, or both. To this end, we examine 212 firms listed on the Indonesia Stock Exchange during 2010 to 2016 and investigate dividend policy, our dependent variable, in terms of: (1) dividend payers and non-payers and (2) higher, lower, and non-dividend payers. The independent variables in the basic model of this study are retained earnings-over-total-equity, return-on-assets, market-to-book value, firm size, and dividend premium, and the control variables are systematic and idiosyncratic risks. For hypothesis testing, this study conducts two analyses, namely logistic regression and its extension to multinomial regression. The findings confirm that pseudo R-squared and confidence improve under the dividend policy when controlling for risk and dividend payers. We find that mature Indonesian firms pay higher dividends as they are larger and more profitable, with more free cash and insignificant growth opportunities. Conversely, growing Indonesian firms with significant future opportunities pay lower dividends. The findings of this study imply that the dividend policy of mature Indonesian firms supports the life-cycle theory and is inconsistent with the catering theory.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

This study examines firm dividend behavior and policy from the perspective of the life-cycle and catering theories using a sample of 212 Indonesian-listed firms. The results of the study show that most mature Indonesian-listed firms pay higher dividends, as they have more free cash, are larger and more profitable, and have insignificant growth opportunities. Conversely, Indonesian-listed firms that increase their size and profitability while having significant growth opportunities pay lower dividends to stockholders. Moreover, this study finds that systematic and idiosyncratic risks based on stock and total returns have an insignificant effect on dividend policy, both for higher and lower dividend payers. Our findings also indicate that mature Indonesian-listed firms pay higher dividends and are less risky on the capital market.

1. Introduction

Black (Citation1996) predicts that the issue of firm dividend policy would always be a puzzle, since there are many perspectives on its determinants. The studies of Kalay and Loewenstein (Citation1986), Hanlon and Hoopes (Citation2014), Ozuomba, Anichebe, and Okoye (Citation2016), and Farrukh, Irshad, Khakwani, Ishaque, and Ansari (Citation2017) show that the issues regarding dividends mainly revolve around how to increase the wealth of stockholders. In this context, Hanlon and Hoopes (Citation2014) and Eisdorfer, Giaccotto, and White (Citation2015) suggest that firm insiders do have obligations to fulfill stockholder expectations, with some considerations.

Many empirical studies, such as Lintner (Citation1956), Fairchild, Guney, and Thanatawee (Citation2014), and Baker and Wurgler (Citation2004a, Citation2004b)), have shown that dividend policies can be viewed from multiple perspectives including the life-cycle and catering theories. Both these theories are considered generally acceptable for the analysis of investor behavior in relationship to dividend policy (Baker & Powell, Citation2012) under the assumption that investors expect an optimum return on their stock investments through dividends, capital gains, or both. Lintner (Citation1956) proposed the life-cycle theory to address how firm size, investments, and earnings could affect dividend policy. According to Fairchild et al. (Citation2014), this theory posits that mature and larger firms with less growth opportunities have higher free cash flows, which enables them to distribute more dividends to shareholders. Supporting the work of Lintner (Citation1956), the findings of DeAngelo, DeAngelo, and Stulz (Citation2006), DeAngelo and DeAngelo (Citation2007), Denis and Osobov (Citation2008), Li and Zhao (Citation2008), Manos, Murinde, and Green (Citation2012), Fairchild et al. (Citation2014), Jordan, Liu, and Wu (Citation2014), Kim and Seo (Citation2014), and He, Ng, Zaiats, and Zhang (Citation2017) confirm that most firm dividend policies are determined by their life-cycles.

The alternative theory, dividend catering, was proposed by Baker and Wurgler (Citation2004a, Citation2004b)). It contends that investor sentiment plays a role in share prices on the capital market and that firm insiders use dividends to cater to shareholders if firm shares are overvalued. Catering theory implies that firms shall initiate dividends when investors set higher price for their stocks, but tend to omit them when investors prefer other stocks (Baker & Wurgler, Citation2004a). Supporting the findings of Baker and Wurgler (Citation2004a, Citation2004b), the studies of Ferris, Sen, and Ho (Citation2006), Li and Lie (Citation2006), Konieczka and Szyszka (Citation2013), Abdulkadir, Abdullah, and Wong (Citation2015), and Neves (Citation2018) show that investors’ reactions to overvalued firm shares tend to induce firm insiders to distribute dividends for their shareholders.

In Indonesia, studies on dividend policy that combine catering and life-cycle theories with risk control are rare. The recent studies of Baker and Powell (Citation2012) and Wardhana and Tandelilin (Citation2018) partially confirm how Indonesian firms determine their dividend policies without controlling for risks. As a developing country, Indonesia is attractive for investors; Statistics Indonesia reported that Indonesia’s economic growth remained positive from 2010 to 2016. Ideally, investors are looking for optimum returns as the objective of their investments, which informs firms to fulfill their shareholder objectives, such as dividends. Our objective is to examine whether these theories hold true in Indonesia, whose emerging market still functions imperfectly (He et al., Citation2017). Further, this study investigates firms as higher and lower dividend payers.

The study’s findings suggest that, on one hand, mature firms pay higher dividends since they have more free cash, are more profitable and larger, and have insignificant growth opportunities. On the other hand, growing firms pay lower dividends as they are becoming more profitable and larger, although they have significant growth opportunities. These findings imply that most mature Indonesian firms’ dividend policies are consistent with life-cycle theory. Given this study’s finding that dividend premium is insignificant for all payers, it is proven that catering does not play a role in dividend policy in Indonesia. There are two contributions of this study towards finance and accounting literature. First, mature Indonesian firms pay higher dividends and, second, certain dividend policies make mature Indonesian firms less risky.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews relevant literature and develops our hypotheses. Section 3 explains the research methodology. Next, Section 4 discusses and details the study results. Finally, Section 5 offers our conclusions and discusses study implications.

2. Literature review

Life-cycle theory. Dividend policy and firm maturity are closely related since mature firms are better positioned to serve their shareholders with dividends given their better performance. According to Garengo, Nudurupati, and Bititci (Citation2007) and O’Connor and Byrne (Citation2015), firms at a later point in their life-cycles (mature firms) have more effective governance and, as a result, stronger performance. This study takes the three firm characteristics of profitability, size, and growth opportunity as representative of firm maturity in the context of explaining the dividend policy in Indonesia. Fama and French (Citation2001) posit that, in life-cycle theory, dividend paying firms have characteristics such as larger size, higher profitability, and fewer investment opportunities. Grullon, Michaely, and Swaminathan (Citation2002) show that current profitability plays a significant role in increasing dividend payments to shareholders when firms show declining investment opportunities and capital expenditures. In addition, this study uses contributed equity to complement the representative indicators of mature firms in explaining dividend policy in the context of life-cycle theory. The studies of DeAngelo et al. (Citation2006) and Denis and Osobov (Citation2008) on the life-cycle theory find that firms with better earned or contributed equity tend to be more mature. DeAngelo and DeAngelo (Citation2007) prove that dividend policy follows the firm’s life-cycle, where dividends are generally distributed by mature firms with large free cash flows. DeAngelo et al. (Citation2006), Denis and Osobov (Citation2008), and Li and Zhao (Citation2008) also show that larger and more profitable firms with few growth opportunities tend to distribute dividends. The studies of Fairchild et al. (Citation2014), Jordan et al. (Citation2014), Kim and Seo (Citation2014), and Kumar and Sujit (Citation2018) provide further evidence consistent with life-cycle theory. In a more recent study, He et al. (Citation2017) show that firms that usually distribute dividends are larger, more profitable, and have fewer investment opportunities. In support of the life-cycle theory, Manos et al. (Citation2012) and He et al. (Citation2017) show that dividend payers are usually older firms.

The other issue relating to dividend policy in the context of the life-cycle theory is risk, which acts as a control for this study. This issue surfaced after Fama and Babiak (Citation1968), Fama and MacBeth (Citation1973), and Miller (Citation1977) proved that, in asset pricing models, higher returns are accompanied by higher risk, but this risk decreases after an increase in the dividend is announced. Grullon et al. (Citation2002) and Li and Zhao (Citation2008) show that firms with a tendency to increase dividends are normally riskier. Lee, Wu, and Hang (Citation1993) posit that firms with higher dividends will have higher systematic risk (SR) if the dividend sends a signal of cash flow uncertainty. Baker and Wurgler (Citation2006) prove that investor sentiment plays a role, so that SR varies among dividend payers. The findings of Holder, Langrehr, and Hexter (Citation1998) and Conover, Jensen, and Simpson (Citation2016) show a negative relationship between risk and dividend policy. Grullon et al. (Citation2002) and Li and Zhao (Citation2008) consistently find that, when firms are more mature, dividends will lower their risk, especially SR. Complementing those findings, the studies of Goyal and Santa-Clara (Citation2003) and Ferreira and Laux (Citation2007) point out that idiosyncratic risk (IR) should also be considered, as it plays a role in stock returns, although Bali, Cakici, Yan, and Zhang (Citation2005) prove that IR does not have long-term influence. Further, Aivazian et al. (Citation2003b) show that firms with lower business risk (IR) pay higher dividends. Hoberg and Prabhala (Citation2009) also clarify that both SR and IR have inverse relationships with dividend policy.

2.1. Catering theory

This study evaluates whether dividend distribution can also be explained by catering theory, in addition to life-cycle theory, since it is another issue related to dividend policy. This study considers dividend premium as this variable is a popular representative of catering theory. Baker and Wurgler (Citation2004a, Citation2004b, Citation2006, Citation2007)) examine the dividend premium to detect whether a firm’s dividend policy caters to shareholders. Their results show that the dividend premium (reflecting investor sentiment) positively affects a firm’s dividend policy. Recently, the dividend premium’s explanatory power for identifying the motives behind the dividend policy has been supported by Ferris et al. (Citation2006), Li and Lie (Citation2006), Konieczka and Szyszka (Citation2013), Abdulkadir et al. (Citation2015), and Neves (Citation2018). However, in some circumstances, the catering theory has been shown to be inconsistent in explaining firm dividend policies. Denis and Osobov (Citation2008) cast doubt on the catering theory by their findings that firm life-cycle dominates dividend policies. Their results are supported by Kim and Seo (Citation2014), who indicate that the dividend premium has an insignificant effect on dividend policy. Hoberg and Prabhala (Citation2009) also provide evidence that the dividend premium is not the main cause of eliminating dividends after controlling for risk. Finally, Chahyadi and Salas (Citation2012) indicate that catering does not play a significant role in dividend policy when controlling for tax.

3. Methodology

This study uses 212 firms listed on the Indonesia Stock Exchange (IDX) between 2010 and 2016 as the sample. To be included in the sample, firms should have made available an audited financial report, a performance report, and not be currently delisted from the capital market. The final sample contains firms in the following sectors: (1) agriculture: 14 firms; (2) mining: 19 firms; (3) basic industry and chemicals: 47 firms; (4) miscellaneous industry: 27 firms; (5) consumer goods industry: 25 firms; (6) infrastructure, utilities, and transportation: 19 firms; and (7) trade, service, and investment: 61 firms. This study uses logistic and multinomial regressions to test the following hypotheses:

H1: Mature Indonesian firms have a higher probability of paying dividends.

H2: Indonesian firms with higher risk have a lower probability of paying dividends.

H3: The dividend premium increases the probability that an Indonesian firm pays dividends.

In term of testing the hypotheses, this study uses the following basic model:

The dependent variable of the model is the dividend policy (Div), measured by Indonesian Rupiahs (IDR) and is analyzed in two ways. In the logistic regression, Div represents dividend payers (1) and non-dividend payers (0), while in the multinomial regression, Div represents higher dividend payers (1), lower dividend payers (2), and non-dividend payers (0). In the logistic regression, dividend payers are firms that pay dividends exceeding IDR 0, on average, over the observed period. For the multinomial regression, this study uses the median among dividend payers to separate higher and lower payers. There are three steps to this process: first, we calculate the average dividend over the observed period for each firm; second, we determine the median from the average dividend as 24.09; and third, we determine higher and lower payers, where firms with their average dividends below or equal to the median are categorized as lower payers and the rest as higher payers. The details of the independent variables of this study are as follows:

RETE is the ratio of retained earnings-over-total-equity. It represents the earned or contributed equity and is used as a proxy to test the life-cycle theory as proposed by DeAngelo et al. (Citation2006). This study normalizes this variable with natural logarithms.

ROA is the ratio of current profit over total assets. It is a characteristic used to detect firm maturity as stated by Fama and French (Citation2001).

MBV is the ratio of market-to-book value, which calculates total assets minus book value of total equity plus market equity (i.e., outstanding shares times share price at the end of the period) and then divides it by the book value of total assets. Fama and French (Citation2001) suggest using this as a reflection of growth opportunities and a firm characteristic that detects maturity.

Size is the firm size, measured by the natural logarithm of total assets. It is also used to detect firm maturity, as suggested by Fama and French (Citation2001).

DP is the dividend premium measured by the difference in the natural logarithm of the average ratio of market MBV between dividend and non-dividend payers for each year. Baker and Wurgler (Citation2004b) suggest using this as a proxy to test whether firms cater to shareholders with dividends. It also reflects investor sentiment on the market.

Risks are divided into SR and IR. There are several procedures to determine the risks in this study. First, following Sharpe (Citation1964), Lintner (Citation1965), Fama and French (Citation1993), and Bali et al. (Citation2005), we use the capital asset pricing model (CAPM) to determine both risks in the basic model as follows:

where Rit represents the returns for each firm in each year based on stock and total returns (capital gains plus dividends); RFt is the risk-free rate or monthly interest rate for each year, drawn from the Central Bank of Indonesia; and RMt represents market or monthly market returns for each year, drawn from the Jakarta Composite Index (JKSE) on Yahoo Finance. Second, following the procedures of Fama and French (Citation1993, Citation2015)), this study uses an extended CAPM (three factors) as follows:

Following Fama and French (Citation1993, Citation2015), this study: (1) excludes firms with negative book equity (BE); (2) categorizes small and large firms in each period based on the market equity (ME) median; (3) categorizes the ratio of book to market equity (BE/ME) as high (30%), medium (40%), and low (30%) over each period; (4) forms six portfolios (S/L, S/M, S/H, B/L, B/M, B/H) in each period, where S and B are small and big firms, respectively, while H, M, and L are high, medium, and low book equities, respectively; (5) calculates small minus big (SMB) in each period as the difference in the average returns of S/L, S/M, and S/H and those of B/L, B/M, and B/H, respectively; and (6) calculates high minus low (HML) in each period as the difference of the average returns of S/H and B/H and those of S/L and B/L, respectively. The small minus big (siSMBt) is the size factor of the firm in each period, while high minus low (hiHMLt) is the value factor of the firm in each period. This study uses two bases for returns (Rit): stock and total returns (capital gains plus dividends) for each firm in each year. The market returns (RMt) are monthly market returns for each year, drawn from the Jakarta Composite Index (JKSE) on Yahoo Finance, while the risk-free rate (RFt) is the monthly interest rate for each year, drawn from the Central Bank of Indonesia. This study regresses monthly returns for each firm in each year to compute SR and IR. The regressions of monthly returns for each firm in each year are based on the following: (1) stock returns after subtracting the risk-free rate of the CAPM; (2) total returns after subtracting the risk-free rate of the CAPM; (3) stock returns after subtracting the risk-free rate of the CAPM extended to three factors; and (4) total returns after subtracting the risk-free rate of the CAPM extended to three factors, which results in 5,936 regressions. From these regressions, we obtain two measurements of risk: (1) SR, measured by the coefficient of determination (R2), and (2) IR, measured by the standard error estimate of the regression.

4. Empirical findings

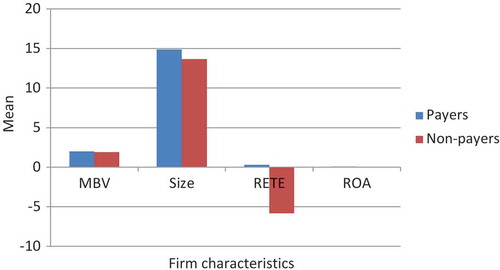

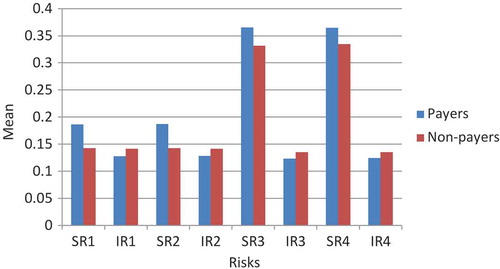

The descriptive statistics in Table show that dividend paying firms are more profitable, larger, and have more growth opportunities relative to non-dividend paying firms, which make them more capable of paying dividends. Moreover, these statistics also show that dividend payers have higher SR and lower IR relative to non-dividend payers. Table also shows that the primary reasons for firms not paying dividends are negative earnings, as reflected by their mean RETE and ROA, although some dividend paying firms share similar circumstances. The positive DP means for payers and non-payers reflect that most investors prefer stocks with certain dividends although, in some cases (reflected by minimum values), investors are looking for stocks with capital appreciation.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for non-payers and payers

Figure shows that listed Indonesian firms that pay dividends have more investment opportunities, as reflected in their MBVs, larger and higher earned/contributed equity, and ROA relative to non-dividend paying firms over 2010–2016.

Figure shows that dividend payers have higher SR and lower IR relative to non-dividend payers.

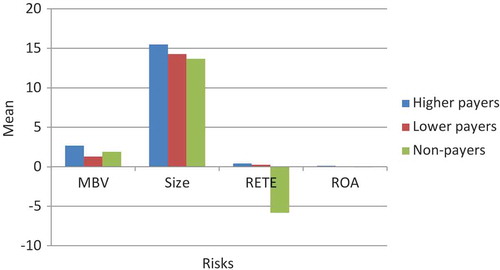

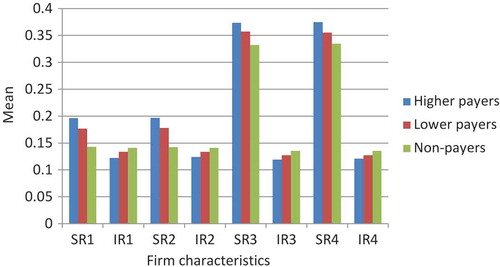

The higher dividend paying firms have the same characteristics as the general dividend payers in Table . However, Table shows that these higher payers are more mature relative to lower payers and non-payers. Moreover, the descriptive statistics show that higher payers also have higher SR and lower IR relative to lower payers and non-payers. Table confirms that most non-dividend paying firms and some higher and lower dividend paying firms have negative earnings. The results for the mean of DP also confirm that most investors prefer firms who distribute dividends.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of non-payers, higher payers, and lower payers

Figure shows that dividend payers tend to have higher profitability, larger size, and higher MBV, as described by Grullon et al. (Citation2002). It also indicates that dividend payers in Indonesia probably support the life-cycle theory proposed by Fama and French (Citation2001), DeAngelo et al. (Citation2006), and Fairchild et al. (Citation2014).

Similarly, Figure shows that higher dividend paying firms have higher SR and lower IR relative to lower paying and non-dividend paying firms. Conversely, it also shows that non-dividend paying firms have the lowest SR and highest IR. As shown in Figures and , SR and IR among Indonesian dividend paying firms (or the higher dividend payers) are consistent with the opinions of Aivazian, Booth, and Cleary (Citation2003a) who indicate that the circumstances in emerging markets are riskier systemically (in terms of SR) but lower in terms of IR.

Furthermore, this study reports that, during 2010 to 2016, the difference in the dividend premium between payers and non-payers of Indonesian listed firms shows a positive value, on average, which indicates that dividend payers tend to cater to shareholders with dividends while their shares are overvalued in the market. Therefore, it is probably true that the dividend policy in Indonesia supports the catering theory as suggested by Baker and Wurgler (Citation2004a, Citation2004b, Citation2006, Citation2007), Ferris et al. (Citation2006), and Li and Lie (Citation2006).

In order to confirm this phenomenon, this study conducts a logistic regression and extends it to multinomial regression using a basic model with eight combinations. In models 1–4, this study uses the four firm characteristics of RETE, ROA, Size, and MBV to test the life-cycle theory, controlling for risks SR(1) and IR(1), SR(2) and IR(2), SR(3) and IR(3), and SR(4) and IR(4), respectively. Next, in models 5–8, this study complements the first four models by including dividend premium to confirm whether, in addition to the life-cycle theory, catering also affects dividend policy.

This study starts with logistic regression for testing the hypotheses on models 1–8. Following the procedures of Kleinbaum and Klein (Citation2010), it analyzes the effect of all independent variables on Div as the proxy of the dividend policy, across dividend (1) and non-dividend payers (0). Non-payer firms are used as reference to determine behaviors related to the dividend policy between both payer types. Model goodness of fit is determined using chi-square values to ensure result validity. Kleinbaum and Klein (Citation2010) suggest that model with a good fit in the logistic regression should have an insignificant chi-square value; as such, we transform variable RETE into a natural logarithm to have a better model fit. Although unreported here, the chi-square values of models 1–8 are insignificant, implying that the models have a good fit.

Models 1–4 in Table show that the ratios of RETE, ROA, and Size are consistently positive and significant for dividend payers relative to non-dividend payers. The results also show that growth opportunities (MBV) and risks (SR and IR) have insignificant effects on dividend policy. The pseudo R-squared values in all the models indicate that all the independent variables consistently explain around 30% of the dividend policy. These results imply that larger dividend payers increase dividends when retained earnings and current profits increase but, conversely, larger non-dividend payers do not pay dividends when these variables increase. Consistent with the descriptive statistics in Table , the mean of RETE is 0.31 for dividend payers and −5.82 for non-dividend payers, which indicates that dividend paying firms have more free cash to distribute as dividends compared to non-dividend payers. The means of ROA for dividend and non-dividend payers are respectively 0.07 and −0.00 (rounded), which implies that firms that pay dividends are more profitable than those that do not. The descriptive statistics also show that payer firms are larger than non-payer firms as the means of Size are, respectively, 14.87 and 13.64. From the regression results in Table , models 1–4 show that the coefficients of ROA are 10.004, 9.993, 10.074, and 10.101, respectively, which are consistently higher than those of RETE at 0.283, 0.283, 0.284, and 0.284, respectively. Regardless of firm size, this study provides evidence that current profit mainly contributes to the dividend policy of Indonesian payer firms. In other words, Indonesian dividend payers are more mature relative to non-dividend payers.

Table 3. Logistic regression on the relationship between life-cycle, catering, and dividend policy

Similar to the study of Lintner (Citation1956) on the United States, this study finds that current profit and retained earnings also determine the dividend policy for Indonesian firms by analyzing the effect of firm size. Consistent with the findings of Fama and French (Citation2001) on the United States, mostly larger and more profitable Indonesian firms tend to pay dividends, and these results support the differences between payers and non-payers, as described by He et al. (Citation2017) for firms in 18 developed countries and 11 emerging markets, including Indonesia.

This study shows that Indonesian firms also have characteristics similar to those in the findings of Grullon et al. (Citation2002) for firms in the United States. These characteristics are related to the maturity level, as suggested by DeAngelo and DeAngelo (Citation2007) in the context of the life-cycle theory. Consistent with the findings of DeAngelo et al. (Citation2006), Denis and Osobov (Citation2008), and Jordan et al. (Citation2014), this study confirms that including RETE besides firm size and profit in the model is very important to explain the life-cycle theory for Indonesian firms. The result on RETE also complements the model of Li and Zhao (Citation2008) in explaining the behavior of Indonesian firms in distributing dividends.

This study supports the model of Denis and Osobov (Citation2008) in explaining the effect of growth opportunities on dividend policy for Indonesian firms and the findings of Wardhana and Tandelilin (Citation2018) for dividend policy, confirming that the results on growth opportunities have different effects over different periods. This study is also consistent with the studies of Fairchild et al. (Citation2014) and Kim and Seo (Citation2014) for Korean firms, although this study emphasizes that firm size is an important determinant for Indonesian firms to decide on their dividend policy. This study supports the study of Kumar and Sujit (Citation2018) on Indian firms, in that ROA and Size are important factors to determine the dividend policy of Indonesian firms, but also shows that MBV does not play a role in determining dividends and RETE complements the explanation for dividend policy in Indonesian firms. Overall, the findings of this study support H1, that is, mature firms have a higher probability of paying dividends.

Furthermore, consistent with the life-cycle theory, we find that, as dividend payers mature, they become less risky as risks (i.e., SR and IR) have an insignificant effect on their dividend policies. For Indonesian firms, this study finds that mature firms increase dividends as they face insignificant risks, which supports the study of Holder et al. (Citation1998) who find that firms with higher risk normally have lower dividends as they face higher transaction costs. This study shows that the insignificant relationship between risks and dividends in Indonesian mature firms is also consistent with Grullon et al. (Citation2002), as they find that mature firms shall increase or maintain dividends by a higher amount as the risk declines because this circumstance significantly reduces the cost of capital. The findings of this study also support the findings of Aivazian et al. (Citation2003b) and Li and Zhao (Citation2008) whereby firms with lower risk normally pay higher dividends to shareholders, rather than risky firms. The findings of Hoberg and Prabhala (Citation2009) and Conover et al. (Citation2016) are also substantiated, as they suggest that risks have a dominant role in explaining disappearing dividends, which implies that dividend payers have lower risks. Thus, H2, that is, firms with higher risk have a lower probability of paying dividends, is also supported.

After including the dividend premium in models 5–8, we find that the dividend premium is insignificant in each model. Based on these results, dividend payers in Indonesia fall under the life-cycle theory rather than catering theory. Moreover, firm characteristics such as RETE, ROA, and Size are consistently significant, with similar coefficients, after including dividend premium in the models. These results also confirm the results of models 1–4 that larger Indonesian firms tend to be more mature and emphasize current profits in deciding on their dividend policies relative to non-dividend payers. Therefore, H3, that the dividend premium increases the probability that a firm pays dividends, is not supported, as the results in our models 5–8 contrast with the findings of Baker and Wurgler (Citation2004a, Citation2004b, Citation2006, Citation2007), Ferris et al. (Citation2006), Li and Lie (Citation2006), Konieczka and Szyszka (Citation2013), Abdulkadir et al. (Citation2015), and Neves (Citation2018) but support the findings of Hoberg and Prabhala (Citation2009), Chahyadi and Salas (Citation2012), and Kim and Seo (Citation2014). This study complements the findings of Hoberg and Prabhala (Citation2009) in that controlling for both SR and IR in the context of Indonesian payer firms will eliminate the effect of dividend premium; our findings show that the effects of dividend premium in model 5–8 are consistently positive and insignificant. Consistent with the findings of Chahyadi and Salas (Citation2012), this study provides evidence that firm characteristics such as RETE, ROA, and Size play a more important role on dividend policy, rather than catering. We also support the findings of Kim and Seo (Citation2014) on Korean firms, although this study finds that size has a significant effect on the dividend policies of Indonesian payer firms.

This study employs multinomial regression analysis to extend the results of the logistic regression. The dependent variable (Div) is divided into higher dividend payers (1), lower dividend payers (2), and non-dividend payers (0), as in Kleinbaum and Klein (Citation2010). RETE is transformed into natural logarithm and we check the goodness of fit using chi-square values. Although the results are not reported here, the goodness of fit test shows that the chi-square values of models 1–8 are insignificant, meaning all models show a good fit. After dividing the payers into higher and lower dividend payers, the results in Table for models 1–4 show specific differences between payers. The pseudo R-squared for all models after controlling for dividend payers improves, stabilizing at 43.2%.

Table 4. Multinomial regression on relationship of life-cycle, catering, and dividend policy

The results of the multinomial regression in Table for higher dividend payers in models 1–8 show that the ratios of RETE, ROA, and Size are consistently positive and significant but the ratio of MBV is insignificant. This means that each increase in RETE, ROA, and Size significantly increases the dividend distribution to shareholders. Moreover, the regression coefficients show that ROA contributes more than RETE to increasing dividends for larger firms that pay higher dividends, which is consistent with the results of the logistic regression. Similarly, ROA and Size are also consistently positive and significant for lower dividend payers; however, their MBV ratios are consistently negative and significant. Furthermore, the ratio of RETE for lower dividend payers is insignificant in models 1–4. Supporting the descriptive statistics in Table , these results are reasonable since higher paying firms have more free cash as their mean RETE is 0.40 compared to the lower paying and non-paying firms with mean values of RETE of 0.22 and −5.82, respectively. The higher paying firms are also more profitable, with a mean ROA of 0.11 compared to lower paying and non-paying firms with mean ROA values of 0.04 and −0.00 (rounded), respectively. The mean values of Size for higher, lower, and non-payers are 15.47, 14.27, and 13.64 respectively, showing that higher payers are larger than other payers.

Consistent with Fama and French (Citation2001), Grullon et al. (Citation2002), DeAngelo et al. (Citation2006), and Fairchild et al. (Citation2014), we find that the behavior of higher dividend payers in Indonesia is consistent with the life-cycle theory, indicating that these firms can be categorized as mature, while the lower dividend payers tend to be growing firms, which cut their dividends when they have more growth opportunities. Based on these findings, H1 is supported for higher dividend payers but not supported for lower dividend payers. This finding also confirms the results of the logistic regression in Table , whereby dividend payers are similar to higher paying firms and not to lower paying firms, given that the latter are at the growth stage.

Similar to Table , we confirm H2 by showing that SR and IR have insignificant effects on dividend policy, both for higher and lower dividend payers, implying that the dividend paying firms in Indonesia are less risky. We, thus, complement the results of the logistic regression in Table and provide evidence that the effect of risks will decrease when firms (both higher and lower payers) distribute dividends to shareholders, as suggested by Aivazian et al. (Citation2003b), Li and Zhao (Citation2008), Hoberg and Prabhala (Citation2009), and Conover et al. (Citation2016).

Consistent with the results of the logistic regression, the results of models 5–8 show that the dividend premium has an insignificant effect on the dependent variable. Therefore, this study confirms that catering is an irrelevant dividend policy in Indonesia, thereby rejecting H3. This finding implies that most Indonesian dividend payers do not distribute dividends in order to cater to the shareholders’ interest to increase share prices in the capital market. The findings on higher and lower dividend payers in this study are inconsistent with those of Baker and Wurgler (Citation2004a, Citation2004b, Citation2006, Citation2007), Ferris et al. (Citation2006), Li and Lie (Citation2006), Konieczka and Szyszka (Citation2013), Abdulkadir et al. (Citation2015), and Neves (Citation2018).

5. Conclusions

The life-cycle and catering theories provide the most well-known explanations of firm dividend behavior and policy. This study investigates whether these theories hold true among Indonesian firms listed on the Indonesia Stock Exchange during 2010–2016. In terms of testing these theories, this study divides the dependent variables by dividend payer types and uses independent variables to assess each theory. We also control for SR and IR, respectively, based on stock returns and total returns, using the CAPM and extended CAPM of Fama and French (Citation1993, Citation2015) to ensure the robustness of the model.

This study finds that mature Indonesian firms pay higher dividends, as they have more free cash, are larger and more profitable, and have insignificant growth opportunities, whereas firms that are larger and more profitable with significant growth opportunities pay lower dividends. The findings also show that SR and IR based on stock returns and total returns measured by the CAPM and extended CAPM (three factors) have insignificant effects on the dividend policies of both higher and lower payers. These findings imply that the dividend policy of mature Indonesian firms is consistent with life-cycle theory. Therefore, this study demonstrates that dividend premium is insignificant in all models, which implies that catering does not play a role in the dividend policy of either higher or lower payers in Indonesia.

There are two contributions of this study in the field of finance and accounting. First, mature firms in Indonesia tend to pay higher dividends and, second, these mature firms tend to be less risky, which means that they are less risky (SR and IR) on the capital market as they have more certain dividend policies. Although the veracity of our findings is evident, our study has some limitations that warrant further investigation. The limitations are as follows: (1) the dividend policy is discussed only from the perspectives of the catering and life-cycle theories, (2) firms with negative book equities are excluded, as required by the extended CAPM, and (3) the findings are limited to cases of Indonesian firms over a specific and rather short period. Some suggestions for further studies are as follows: (1) extend the perspectives for dividend policy (e.g., to free cash flow theory), (2) extend the variables (e.g., debt) to better explain dividend policies, (3) extend the sample, and (4) expand the model to firms in other countries, especially firms which have characteristics similar to those of Indonesian firms.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Novi Swandari Budiarso

Novi Swandari Budiarso is a lecturer in finance and public sector finance in the Economics and Business Faculty, Sam Ratulangi University, Indonesia. Related to her primary research field, she has published on the main topic of dividend policy, as well as on the accountability of local governments, intellectual capital, auditing, and firm financial distress.

Bambang Subroto

Bambang Subroto is a professor in accounting in the Economics and Business Faculty, Brawijaya University, Indonesia. He has published papers in the areas of financial markets, auditing, finance, and public sector finance.

Sutrisno T

Sutrisno T is a professor in accounting in the Economics and Business Faculty, Brawijaya University, Indonesia. His widely published research is in the areas of corporate social disclosure, auditing, taxation, and finance.

Winston Pontoh

Winston Pontoh is an associate professor in finance and accounting in the Economics and Business Faculty, Sam Ratulangi University, Indonesia. His published work is mainly in the areas of dividend policy, capital structure, and stocks on the capital market.

References

- Abdulkadir, R. I., Abdullah, N. A. H., & Wong, W.-C. (2015). Dividend policy changes in the pre-, mid-, and post-financial crisis: Evidence from the Nigerian stock market. Asian Academy of Management Journal of Accounting and Finance, 11(2), 103–15. http://eprints.usm.my/40036/1/aamjaf110215_05.pdf

- Aivazian, V., Booth, L., & Cleary, S. (2003a). Dividend policy and the organization of capital markets. Journal of Multinational Financial Management, 13(2), 101–121. doi:10.1016/S1042-444X(02)00038–5

- Aivazian, V., Booth, L., & Cleary, S. (2003b). Do emerging market firms follow different dividend policies from U.S. firms? The Journal of Financial Research, 26(3), 371–387. doi:10.1111/1475–6803.00064

- Baker, H. K., & Powell, G. E. (2012). Dividend policy in Indonesia: Survey evidence from executives. Journal of Asia Business Studies, 6(1), 79–92. doi:10.1108/15587891211191399

- Baker, M., & Wurgler, J. (2004a). Appearing and disappearing dividends: The link to catering incentives. Journal of Financial Economics, 73(2), 271–288. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2003.08.001

- Baker, M., & Wurgler, J. (2004b). A catering theory of dividends. The Journal of Finance, 59(3), 1125–1165. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.2004.00658.x

- Baker, M., & Wurgler, J. (2006). Investor sentiment and the cross-section of stock returns. The Journal of Finance, 61(4), 1645–1680. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.2006.00885.x

- Baker, M., & Wurgler, J. (2007). Investor sentiment in the stock market. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(2), 129–151. doi:10.1257/jep.21.2.129

- Bali, T. G., Cakici, N., Yan, X., & Zhang, Z. (2005). Does idiosyncratic risk really matter? The Journal of Finance, 60(2), 905–929. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.2005.00750.x

- Black, F. (1996). The dividend puzzle. The Journal of Portfolio Management, 23(5), 8–12. doi:10.3905/jpm.1996.008

- Chahyadi, C. S., & Salas, J. M. (2012). Not paying dividends? A decomposition of the decline in dividend payers. Journal of Economics and Finance, 36(2), 443–462. doi:10.1007/s12197-010-9132–0

- Conover, C. M., Jensen, G. R., & Simpson, M. W. (2016). What difference do dividends make? Financial Analysts Journal, 72(6), 28–40. doi:10.2469/faj.v72.n6.1

- DeAngelo, H., & DeAngelo, L. (2007). Payout policy pedagogy: What matters and why. European Financial Management, 13(1), 11–27. doi:10.1111/j.1468-036X.2006.00283.x

- DeAngelo, H., DeAngelo, L., & Stulz, R. M. (2006). Dividend policy and the earned/contributed capital mix: A test of the life-cycle theory. Journal of Financial Economics, 81(2), 227–254. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2005.07.005

- Denis, D. J., & Osobov, I. (2008). Why do firms pay dividends? International evidence on the determinants of dividend policy. Journal of Financial Economics, 89(1), 62–82. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2007.06.006

- Eisdorfer, A., Giaccotto, C., & White, R. (2015). Do corporate managers skimp on shareholders’ dividends to protect their own retirement funds?. Journal of Corporate Finance, 30, 257–277. doi:10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2014.12.005

- Fairchild, R., Guney, Y., & Thanatawee, Y. (2014). Corporate dividend policy in Thailand: Theory and evidence. International Review of Financial Analysis, 31, 129–151. doi:10.1016/j.irfa.2013.10.006

- Fama, E. F., & Babiak, H. (1968). Dividend policy: An empirical analysis. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 63(324), 1132–1161. doi:10.1080/01621459.1968.10480917

- Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (1993). Common risk factors in the returns on stocks and bonds. Journal of Financial Economics, 33(1), 3–56. doi:10.1016/0304-405X(93)90023-5

- Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (2001). Disappearing dividends: Changing firm characteristics or lower propensity to pay?. Journal of Financial Economics, 60(1), 3–43. doi:10.1016/S0304-405X(01)00038-1

- Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (2015). A five-factor asset pricing model. Journal of Financial Economics, 116(1), 1–22. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2014.10.010

- Fama, E. F., & MacBeth, J. D. (1973). Risk, return, and equilibrium: Empirical tests. Journal of Political Economy, 81(3), 607–636. doi:10.1086/260061

- Farrukh, K., Irshad, S., Khakwani, M. S., Ishaque, S., & Ansari, N. Y. (2017). Impact of dividend policy on shareholders wealth and firm performance in Pakistan. Cogent Business & Management, 4, 1–11. doi:10.1080/23311975.2017.1408208

- Ferreira, M. A., & Laux, P. A. (2007). Corporate governance, idiosyncratic risk, and information flow. The Journal of Finance, 62(2), 951–989. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4622291df

- Ferris, S. P., Sen, N., & Ho, P. Y. (2006). God save the Queen and Her dividends: Corporate payouts in the United Kingdom. The Journal of Business, 79(3), 1149–1173. doi:10.1086/500672

- Garengo, P., Nudurupati, S., & Bititci, U. (2007). Understanding the relationship between PMS and MIS in SMEs: An organizational life-cycle perspective. Computers in Industry, 58(7), 677–686. doi:10.1016/j.compind.2007.05.006

- Goyal, A., & Santa-Clara, P. (2003). Idiosyncratic risk matters!. The Journal of Finance, 58(3), 975–1007. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3094569

- Grullon, G., Michaely, R., & Swaminathan, B. (2002). Are dividend changes a sign of firm maturity?. The Journal of Business, 75(3), 387–424. doi:10.1086/339889

- Hanlon, M., & Hoopes, J. L. (2014). What do firms do when dividend tax rates change? An examination of alternative payout responses. Journal of Financial Economics, 114(1), 105–124. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2014.06.004

- He, W., Ng, L., Zaiats, N., & Zhang, B. (2017). Dividend policy and earnings management across countries. Journal of Corporate Finance, 42, 267–286. doi:10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2016.11.014

- Hoberg, G., & Prabhala, N. R. (2009). Disappearing dividends, catering, and risk. The Review of Financial Studies, 22(1), 79–116. doi:10.1093/rfs/hhn073

- Holder, M. E., Langrehr, F. W., & Hexter, J. L. (1998). Dividend policy determinants: An investigation of the influences of stakeholder theory. Financial Management, 27(3), 73–82. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3666276

- Jordan, B. D., Liu, M. H., & Wu, Q. (2014). Corporate payout policy in dual-class firms. Journal of Corporate Finance, 26, 1–19. doi:10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2014.02.004

- Kalay, A., & Loewenstein, U. (1986). The informational content of the timing of dividend announcements. Journal of Financial Economics, 16(3), 373–388. doi:10.1016/0304-405X(86)90035-8

- Kim, S., & Seo, J.-Y. (2014). A study on dividend determinants for Korea’s information technology firms. Asian Academy of Management Journal of Accounting and Finance, 10(2), 1–12. http://eprints.usm.my/40021/1/AAMJAF_10-2-1_(1–12).pdf

- Kleinbaum, D. G., & Klein, M. (2010). Logistic regression: A self-learning text (3rd ed.). New York: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-1742-3

- Konieczka, P., & Szyszka, A. (2013). Do investor preferences drive corporate dividend policy?. International Journal of Management and Economics, 39(1), 70–81. doi:10.2478/ijme–2014–0022

- Kumar, B. R., & Sujit, K. S. (2018). Determinants of dividends among Indian firms—An empirical study. Cogent Economics & Finance, 6(1), 1–18. doi:10.1080/23322039.2018.1423895

- Lee, C. F., Wu, C., & Hang, D. (1993). Dividend policy under conditions of capital market and signaling equilibria. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 3(1), 47–59. doi:10.1007/BF02408412

- Li, K., & Zhao, X. (2008). Asymmetric information and dividend policy. Financial Management, 37(4), 673–694. doi:10.1111/fima.2008.37.issue-4

- Li, W., & Lie, E. (2006). Dividend changes and catering incentives. Journal of Financial Economics, 80(2), 293–308. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2005.03.005

- Lintner, J. (1956). Distribution of incomes of corporations among dividends, retained earnings, and taxes. The American Economic Review, 46(2), 97–113. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1910664

- Lintner, J. (1965). The valuation of risk assets and the selection of risky investments in stock portfolios and capital budgets. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 47(1), 13–37. doi:10.2307/1924119

- Manos, R., Murinde, V., & Green, C. J. (2012). Dividend policy and business groups: Evidence from Indian firms. International Review of Economics and Finance, 21(1), 42–56. doi:10.1016/j.iref.2011.05.002

- Miller, E. M. (1977). Risk, uncertainty, and divergence of opinion. The Journal of Finance, 32(4), 1151–1168. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.1977.tb03317.x

- Neves, M. E. D. (2018). Payout and firm’s catering. International Journal of Managerial Finance, 14(1), 2–22. doi:10.1108/IJMF-03-2017–0055

- O’Connor, T., & Byrne, J. (2015). Governance and the corporate life-cycle. International Journal of Managerial Finance, 11(1), 23–43. doi:10.1108/IJMF-03-2013-0033

- Ozuomba, C. N., Anichebe, A. S., & Okoye, P. V. C. (2016). The effect of dividend policies on wealth maximization—A study of some selected plcs. Cogent Business & Management, 3, 1–15. doi:10.1080/23311975.2016.1226457

- Sharpe, W. F. (1964). Capital asset prices: A theory of market equilibrium under conditions of risk. The Journal of Finance, 19(3), 425–442. 10.2307/2977928 Statistics Indonesia (www.bps.go.id).

- Wardhana, L. I., & Tandelilin, E. (2018). Do we need a regulation on dividends for Indonesia stock exchange? Gadjah Mada International Journal of Business, 20(1), 33–58. doi:10.22146/gamaijb.25055