?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The article analyses inter-dependencies between dividend, capital structure, and cost of capital, factoring the ownership structure of listed firms in India, using 3SLS system approach. The study finds that family firms are dominant with concentrated ownership. Dividend, leverage, and average cost of capital are inter-linked. However, family firms pay lower dividends, consistent with family owners extracting rent from external minority shareholders. Additionally, these firms have high leverage and lower cost of capital, suggesting that family control (reputation) provides intangible value to the firms. Ownership structure plays a critical role in understanding the policy decisions in emerging markets.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Family ownership and control play a crucial role in defining key policy decisions of corporates. Generally, family-owned firms possess high private benefits and lack in strong corporate governance. Distribution of profits among shareholders and mobilization of funds as debt are two important parameters which influence cash flows and risk of a corporate. Family-controlled and widely held firms through their ownership structure influence dividend policy and capital structure, which are two fundamental policies of corporates. The article investigates the interrelation between dividend, capital structure, and cost of capital with a focus on ownership structure, primarily family-controlled firms. The study found, through family firms have high risk, these firms have lower dividend payouts, higher debt proportion, and lower cost of capital. These findings signify that family acts as intangible collateral for the financial institutions.

1. Introduction

The interrelationship of dividend and capital structure has been a major focus of research in finance (DeAngelo & DeAngelo, Citation2007; Jensen, Solberg, & Zorn, Citation1992; Mulyani, Singh, & Mishra, Citation2016; Myers, Citation1984). Dividend payments generally induce new equity or debt to meet investments, thus reduce agency cost through capital market monitoring (Easterbrook, Citation1984). However, firms are reluctant to pay higher dividend payouts when they have higher obligations for other financial expenses (Allen & Michaely, Citation2003). Dividend payments though ease the cost of equity but high debt increases the average cost of capital of the firm. Higher dividends reduce the cost for equity, but it may force a firm to revisit capital markets, thereby increasing the cost of external borrowings. Cost of capital decreases with increasing leverage (Modigliani & Miller, Citation1963), but high leverage increases the level of financial risk, bankruptcy risk, and debt-related agency costs, suggesting a higher cost of capital for such firms. Thus, dividend and cost capital are interrelated and their relationship is complex which needs to be analyzed against the changing nature of firms and their sources of raising funds.

Dividend distributions are not only a means of regular income, but important in firm valuation (Bernstein, Citation1998). Dividend payments may induce new equity or debt issue to meet investments, thus reduce agency cost through capital market monitoring (Easterbrook, Citation1984). Empirical evidences suggest that capital structure and dividend payouts have a similar set of causal variables, favoring a joint determination of the two (DeAngelo & DeAngelo, Citation2007). Using Pecking Order theory, DeAngelo and DeAngelo (Citation2007) show that the capital structure, payout policy, and cash balances are jointly determined.

Ownership structure influences policy decisions including dividend payouts and leverage. Cost of capital decreases with increasing leverage (Modigliani & Miller, Citation1963), but high leverage increases firm risk and debt-related agency costs. Business risks affect the financing decisions and may lead to financial distress and bankruptcy (Booth, Aivazian, Demirguc‐Kunt, & Maksimovic, Citation2001). With large undiversified stakes, family owners carry more risk, leading to higher financial distress (Andres, Betzer, Goergen, & Renneboog, Citation2009). Mulyani et al. (Citation2016) show that family ownership concentration (agency problem) influences the joint determination of dividend and leverage of Indonesian firms. Dividend payouts, leverage, and cost of capital are interlinked and hence, they should be jointly evaluated for policies formulation.

Empirical validation to the various conceptual issues relating to dividend payouts and capital structure of emerging market firms need further in-depth studies. This paper fills the void by providing empirical evidences on inter-linkages between dividends, leverage and cost of capital of Indian listed firms with a focus on family ownership concentration.

The article utilizes a sample of 5,027 firm-year observations of the National Stock Exchange of India listed firms between 2006 and 2017. The sample consists of approximately 60% of family firms. Indian family firms are young, family members hold large ownerships and in many cases, they are involved in firms’ boards and management. These unique attributes provide significant opportunities to explore how the family ownership concentration affects policy decisions and operating efficiency, thereby affecting the valuation of the firm.

The findings show that family firms have lower dividend payout, higher debt proportion, and the lower average cost of capital compared to widely held firms. It further submits that higher family ownership concentration tends to lower the average cost of capital. Though, the study sample is confined to India; but the policy decisions (dividend and capital structure) in relation to family firms contribute in better understanding of family firms in other emerging markets having high ownership concentration and weak corporate governance (Mitton, Citation2004). The study provides insights into family ownership in the evolution of firms in emerging market economies. The findings would be of importance to researchers as well as corporate managers.

The remainder of the paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 provides a brief review of the relevant literature and develops the hypotheses. Section 3 highlights the sample and data characteristics used in this study. Section 4 discusses the methodology and develops the econometric model. Section 5 analyses the empirical results. Section 6 concludes the study.

2. Literature review and hypothesis development

2.1. Ownership structure

Ownership structure plays a pivotal role in influencing a firm’s business decisions. Shareholders experience a loss of control when ownership dispersion is high and a typical shareholder cannot exercise real power to oversee managerial performance in modern corporations. The separation of ownership and management generates a condition where the interests of the owner and of manager are no more common, giving rise to agency problems between owners and managers. Berle and Means (Citation1932) were the first to discuss issues related to the separation of ownership and control and recommend that separation reduces the profit incentives of corporate managers. Jensen (Citation1986) points to the preference of managers to increase firm size through excessive investment for private benefit.

Ownership concentration and management control have a complex relationship, and their level of diffusion varies between firms. Information asymmetry is high in widely dispersed firms (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976) leading to high agency costs between owners and managers. Institutional investors push managers to distribute free cash as dividends to reduce agency problems (Jensen, Citation1986). Additionally, as foreign institutional investors are subject to a higher degree of information asymmetry, they prefer higher dividend payments compared to companies retaining earnings (Baba, Citation2009). Higher dividends reduce a firm’s cash position and mitigate agency problems (Shleifer & Vishny, Citation1986).

Ownership concentration differs between firms in emerging and developed markets. Faccio, Lang, and Young (Citation2001) document that firms in East Asian countries have concentrated ownership and are largely family controlled. Founding families have majority ownership, around 35%, in firms in the Standard and Poor’s 500 (Anderson & Reeb, Citation2003). Claessens, Djankov, and Lang (Citation2000) find that among nine East Asian countries, more than half are family controlled.

The involvement of family members in family businesses is the unique feature of family firms (Chua, Chrisman, & Sharma, Citation1999). In family firms, ownership and management remain inside the family or group of families (Burkhart, Panunzi, & Shleifer, Citation2003), therefore have low agency problem. Family firms have concentrated ownership (Gomez-Mejia, Nunez-Nickel, & Gutierrez, Citation2001) and undiversified portfolio with excessive risk (Shleifer & Vishny, Citation1997). Family owners also have longer investment horizons than other investor groups.

Expropriation of minority shareholders and tunneling issues are high among the family firms (Claessens et al., Citation2000). Tunneling involves transfer of assets and profits out of firms for the benefit of those who control them. Gugler (Citation2003) affirms that family-controlled firms are less inclined to smooth dividends with increase in profitability. Aivazian, Booth, and Cleary (Citation2003) report that the ownership concentration of the three biggest shareholders is relatively low in the United States (20%) and South Korea (23%) but higher in emerging markets such as India (40%), Malaysia (54%), Thailand (47%), and Turkey (59%). La Porta et al. (Citation1998) find that East Asian corporations have high ownership concentration. Truong and Heaney (Citation2007) report that ownership concentration negatively affects dividend payments, in a study across 37 countries.

Families are long-term investors and are concerned with passing control to the next generation (Anderson, Mansi, & Reeb, Citation2003). Control of the firm provides great economic value to family owners. The controlling families have greater access and power to misuse a firm’s value at the cost of minority shareholders (Easterbrook, Citation1984). Financial leverage is another mechanism to reduce cash with the management otherwise be misused, thus helps in mitigating agency problems (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). The external borrowing from capital markets leads to market monitoring (Easterbrook, Citation1984), thus debt alleviates the problem of over-investment. In emerging markets, family firms are dominant and have concentrated ownership. Family firms are more levered since family owners have the tendency of retaining control and debt borrowings help to meet new investments substantially. The concentrated family holdings provide incentives for financial institutions to provide long-term debt capital, and therefore, have a lower average cost of capital.

2.2. Dividend policy

The classic theories of Walter (Citation1956), Lintner (Citation1956), and Gordon (Citation1962) are mostly apprehensive with the stability of dividend policy and its bearing on firm value. Walter suggests that a firm’s internal rate of return and cost of capital maximize shareholder value. Lintner specifies that managers are hesitant to change a firm’s dividend policy unless they realize sustained earnings and subsequently, slowly adjust to the target dividend policy. Gordon finds that dividend policy plays an imperative role in firm valuation where a share’s market value equals the present value of an infinite stream of dividends received. However, these classical theories are subject to criticism due to their opaque investment policy that ignores external financing.

Miller and Modigliani (MM) (Citation1961) provide the foundation to the modern theory of dividend by linking dividend policy with capital markets. According to MM theory, dividends are irrelevant under perfect capital market conditions (i.e., no taxes, fixed investment policy, and no risk of uncertainty). Firms pay dividends and concurrently “time the issue” of new shares to raise funds to undertake an optimal investment policy. Researchers propose various explanations of dividend payment behavior including an agency theory, free cash flow, firm maturity, signaling, and capital structure, among others.

Given Type I agency problem (principal-agent conflict) arise from the different priorities of the owners (principal) and managers (agent), researchers contend that dividend payments may serve as a governance mechanism to mitigate agency problems by reducing free cash flow of the firm (Jensen, Citation1986), which could possibly be expropriated otherwise (Faccio et al., Citation2001). Type II agency problem refers to the conflict between majority and minority shareholders, as majority shareholders hold substantial ownership and have controlling positions in the firm. Thus, agency theory provides two different views of ownership structure. First, family ownership offers better orientation between owners and management, ending up with superior monitoring of management (Anderson & Reeb, Citation2003). The second view recommends that controlling families have greater access and power to misappropriate a firm’s value at the cost of minority shareholders (Shleifer & Vishny, Citation1997). Thus, it proposes that if investor protection is weak, shareholders with a controlling stake are common (La Porta, Lopez de Silanes, & Shleifer, Citation1999) and large owners tend to gain full corporate control to generate private benefits (Shleifer & Vishny, Citation1997).

The maturity theory suggests that large and mature firms tend to have higher profitability but limited growth opportunities, leading to better cash flows. Dividend payouts reduce the free cash available and thus restrict over-investment (Black, Citation1976). According to MM (Citation1961), investors are likely to interpret a change in dividends as a change in managements’ views concerning future profitability prospects of the firm. The signaling theory explains that news about reduced risk is more important than the reduction in payout, and a risk-averse investor is more anxious about potential downside risk involved in investment than a possible decrease in dividend payout (Bhattacharya, Citation1979). Further, a firm with high risk favors low dividend payout.

Mahapatra and Sahu (Citation1993), Kevin (Citation1992) and Gupta and Banga (Citation2010) provide evidences supporting free cash flow and signaling theory for Indian firms. Manos, Murinde, and Green (Citation2012) suggest that financial constraints (dependency on external finance) and information asymmetry are negatively associated with dividends among Indian firms. Consequently, Indian companies prefer to retain cash to meet investment obligations. Raghunathan and Das (Citation1999) report a stable dividend payout of around 30% between 1990 and 1999 for the largest 100 Indian companies, which is consistent with Lintner’s (Citation1956) model.

2.3. Capital structure

There is no universal theory of the debt-equity choice (Myers, Citation2001). However, there are several valuable conditional theories, including agency theory (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976), tradeoff theory (Brennan & Schwartz, Citation1978), pecking order theory (Myers, Citation1984; Myers & Majluf, Citation1984), and bankruptcy theory among others. According to Modigliani and Miller (Citation1958), source of capital (debt versus equity) has no material effects on firm value under perfect and frictionless capital market, where the financial innovation would quickly extinguish any deviation from their predicted equilibrium. Nevertheless, debt-finance matters because of corporate taxes, asymmetry, and agency costs.

High debt limits the free cash available to the manager, a remedy for Type I agency problem. It obliges the managers to pay interest in the future, thereby curtailing incentive to follow personal benefits, assuming they want to evade bankruptcy. Firms with higher debt have higher interest expenses and are more likely to be cash constrained, thus prefer low dividends. High leverage increases the risks of insolvency, at the same time low leverage leads to equity dilution.

Jensen and Meckling (Citation1976) outline information asymmetry (agency problem) between creditors and shareholders. This agency problem appears because of their differing attitude towards risk. The shareholders may prefer to invest in risky projects where profits are potentially large, a case especially when a firm faces financial distress or is close to bankruptcy. In case of bankruptcy, creditors have the first right and shareholders have only residual right. Thus, shareholders benefit from large profits. Moreover, when investments fail, the creditors bear the consequences.

The tradeoff theory suggests that a firm chooses optimal debt levels that balance the tax advantages of additional debt against the costs of possible financial distress. However, high leverage increases the probability of financial distress (Myers, Citation1984). Family firms have large undiversified stakes, leading to higher level of risk (Andres, Citation2008). The tradeoff theory fails to account for the correlation between high profitability and low debt.

The pecking order theory suggests that a firm borrows, rather than issuing equity, when internal cash flow is not sufficient to fund capital expenditures and equity is the last resort (Myers, Citation1984). In a simple pecking order model, firms with high investment and growth opportunities are expected to have high leverage (assuming retained earnings are not sufficient). However, complex version of pecking order model accounts for current as well as future financing needs and associated costs and carry low leverage.

The bankruptcy theory focuses upon the business risk, which may affect the financing decisions of a firm. Because of higher financial distress, family enterprises seek to reduce their leverage (Andes, Citation2008). Modigliani and Miller (Citation1958) state that the cost of equity (COE) of a levered firm is higher than that of an unlevered firm with similar business risk. The large firms are more diversified and hence less prone to bankruptcy (Titman & Wessels, Citation1988) and higher maturity level makes access to capital market easy for such firms (Aivazian et al., Citation2003).

2.4. Cost of capital

Modigliani and Miller (MM) (Citation1958) provide the foundation to the modern theory of Cost of Capital (COC). MM show that the average COC of any firm is independent of its capital structure and is equal to the capitalization rate of a pure equity stream of its class, under perfect and frictionless market conditions. Further, with the introduction of corporate taxes, MM (Citation1963) demonstrates that the weighted average cost of capital (WACC) decreases with increasing leverage. MM (Citation1958) developed proposition II stating that COE of a levered firm is higher than that of an unlevered firm of the same (business) risk class. Hamada (Citation1972) combines MM’s proposition with the capital asset pricing model (CAPM) and proposes a model, which shows that risk increases with financial leverage. Consequently, an increase in a firm’s systematic risk results in a higher WACC for the firm, ceteris paribus.

Jensen and Meckling (JM) (Citation1976) highlight that the managers have private benefits and follow an opportunistic behavior (Type I agency problem) and tend to dilute the ownership structure by funding investment through equity issuance. Investors anticipate this agency problem and, therefore, offer lower prices to acquire equity, thereby increasing the COE financing. A similar theoretical argument explains the debt financing. Type I agency problem stimulates creditors to increase the cost of debt (COD). Thus, JM supports the idea of optimal debt–equity ratio that jointly minimizes the agency costs, and therefore impliing a reduction in COC.

Gordon (Citation1959) proposes the bird-in-the-hand argument that investors prefer dividends in short term than the uncertain capital gains and claims that COE is lower for dividend-paying firms. Higher the dividend payout, the lower is the COE. Contrary to this, Brennan (Citation1970) contemplates tax disparities between dividends and capital gains and contends that firms with no dividends have higher valuations. A firm with high systematic risk has higher COE and COD, thereby higher COC. In general, healthy and profitable firms entail less risk, thus higher the profitability, lower is the COC. Further, mature, large and diversified firms have a lower systematic risk, suggesting lower COC.

Based on the above discussions on ownership structure, dividend, capital structure, and cost of capital, we posit following hypotheses related to family firms pertaining to emerging markets.

Hypothesis 1a. Family firms pay low dividend compared to widely held firms.

Hypothesis 1b. Family firms are more levered compared to widely held firms.

Hypothesis 1c. Family firms have lower cost of capital compared to widely held firms.

Hypothesis 2a. There is a negative relationship between family ownership and dividend payout.

Hypothesis 2b. Family ownership concentration positively influences debt ratio of a firm.

Hypothesis 2c. Family ownership and firms’ average cost of capital have negative relationship.

Two sets of hypotheses are included. Hypotheses (1a, 1b, 1c) differentiate dividend payout, leverage, and cost of capital for family firms as a group vis-à-vis widely held firms. Hypotheses (2a, 2b, 2c) relate family ownership concentration with dividend payout, leverage, and cost of capital.

2.5. Interrelationship effect among dividend, leverage, and cost of capital

Literatures suggest that the empirical modeling of capital structure and dividend payouts include approximately the same set of causal variables, favoring a joint determination of capital structure and dividend payout (DeAngelo & DeAngelo, Citation2007). Dividends and debt are widely viewed as substitute mechanism in controlling agency problems (Rozeff, Citation1982). Firms raise debt to compensate earnings deficit, as they are reluctant to change dividend payouts (Lintner, Citation1956). Free cash flow theory suggests that high-levered firms have large cash outlay to meet financial obligations and are cash constrained; therefore, lower dividend payouts (Jensen, Citation1986). DeAngelo and DeAngelo (Citation2007) examine measures of financial flexibility of a firm. The evidences show that the capital structure, payout policy, and cash positions are jointly determined. Mulyani et al. (Citation2016) examine the role of dividends and debt to address agency problems within Indonesian family firms and their findings support a two-way negative linkage between dividend and leverage.

Dividend policy of a firm influences its COC and COC considerations to affect a firm’s dividend policy. High dividend payouts reduce COE but at the same time, a firm may need to revisit capital markets, thereby increasing COD (investors-creditors agency problem). Alternatively, firms, with higher COC (high agency costs and financial costs of raising external equity) or having a managerial preference to retain more of their earnings, may prefer low dividend payouts. Therefore, there exist a two-way causalities between dividends and COC.

Leverage has a positive association with the level of financial risk, bankruptcy risk, and debt-related agency costs, suggesting a positive relation between leverage and COC. On the other hand, interest tax-shield suggests that a firm with higher debt have a lower cost of capital. Alternatively, firms having higher equity have higher COE as equity holders have residual benefit. However, sources of capital have potential bearings on the firm’s average COC. These influencing factors affect in determining the choice of debt versus equity. The differing risk levels of projects influence a firm’s mix of sources of capital. Therefore, the resulting COC turns out to be a function of the nature of investment projects undertaken by the firm and higher the COC, lower is the debt portion of the capital.

MM (Citation1958) studies the relation between WACC and financial leverage and conclude that WACC is not affected by capital structure. Weston (Citation1963) extends this study with the addition of size and growth variables and determines that WACC decreases with increasing leverage, consistent with MM’s conclusion upon introduction of corporate taxes into their analysis. In a follow-up study, Miller and Modigliani (Citation1966) use a larger sample and 3-year data and their findings are consistent with that reported by Weston (Citation1963).

Jensen et al. (Citation1992) investigate interdependencies among insider ownership, debt and dividend policy through agency and signaling theories. Using 3SLS, they show that debt and dividend negatively affect each other, while inside ownership shows one-way causality, significant and negative for dividend and leverage. Bathala and Rao (Citation2005) study the relation between COC, leverage and dividend and show that all three are negatively interrelated.

Literatures establishing inter-linkages between the policy decisions relating to dividends, capital structure, and the COC provide evidences based on cross-sectional studies and are mostly pertaining to the US firms, which are widely dispersed. In emerging markets, family firms are dominant and have concentrated ownership structure. Family firms are more levered as family owners have the tendency of retaining control and debt borrowings help to meet the new investments substantially. Further, concentrated family holdings provide incentives for financial institutions to provide long-term debt capital.

Family control influences policy decisions and with concentrated ownership, family firms carry more risk. The capital structure theory suggests that Cost of capital decreases with increasing leverage (Modigliani & Miller, Citation1963). However, high leverage may induce high firm risk and debt-related agency costs, leading to financial distress and bankruptcy (Booth et al., Citation2001). Therefore, Dividend payouts, leverage, and cost of capital are interlinked and hence, they should be jointly evaluated for policies formulation.

Based on the above discussion, the following hypotheses, applicable to an emerging market, are proposed.

Hypothesis 3a. Dividend and leverage have bidirectional and negative association.

Hypothesis 3b. There exists bidirectional causality between Dividend and Cost of capital.

Hypothesis 3c. There exists bidirectional relationship between leverage and Cost of capital.

3. Sample and data characteristics

The study investigates the interrelationship between dividend, debt ratio and cost of capital of non-financial firms listed on the National Stock Exchange (NSE) of India between 2006 and 2017. Data are drawn from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE). Ownership concentration details are available from 2006. The sample excludes government-owned firms. Further, the sample includes only dividend payers (excludes firms that paid no dividends for three or more consecutive years), as the objective of the study is to investigate the interrelationship between dividend, leverage, and cost of capital. The final sample consists of 457 firms.

We construct several groups based on family ownership concentration. Family firms (FAMILY) represent those having family ownership of at least 5% of a firm’s equity, individually or as a group and remaining are widely held firms (WIDE) (Villalonga & Amit, Citation2006). As 5% family ownership could be low, we define family ownership control for the group having ownership of at least 20%, similar to the definitions of Faccio and Lang (Citation2002) and Kusnadi (Citation2011). The family-controlled firms (FAMCON) are one where ownership control lies with the family (family ownership at least 20% of total equity). FAMILY consists of 274 firms (60%) and of these 183 firms belong to FAMCON. Of the remaining 91 firms, 90 firms have enhanced control mechanism by way of affiliated corporate ownership.

4. Methodology and econometric model

As discussed in the literature review section, there exists interdependency among dividend, capital structure cost of capital of a firm. Endogeneity issue makes the conventional OLS estimator biased and inconsistent.

4.1. Instrumental variable estimator

Generally, for one model equation, Instrumental Variable (IV) regression is used. Assuming, X is endogenous in the regression equation (). So, X is correlated by the error term and OLS is biased and inconsistent. First, X is regressed on Z (instrumental variable) to get a “predicted X” (X-hat), which is independent of error term (u). Second, Y is regressed on X-hat to estimate β. However, for two or more equations, system estimators are considered.

4.2. System estimators

Simultaneous equations model has multiple equations (system of equations) and dependent variables in some equations are explanatory variables in other equations. Thus, dependent variables feed off each other and resonate shocks to one variable through the model. Two-stage least squares (2SLS) and three-stage least squares (3SLS) are widely used to address the endogeneity issue among system equations. Thus, a system estimator uses more information than a single equation estimator (e.g., contemporaneous correlation among the error terms across equations, cross-equation restrictions, etc.), and therefore produce more precise estimates.

3SLS estimation uses a three-step process. First two steps involve two successive applications of the OLS estimator. In stage one, we get predicted values of Y1 and Y2 (Y1hat & Y2hat) from the reduced form equations. Thereafter, final equations are estimated (stage two) by replacing Y2 and Y1 with Y2hat and Y1hat, respectively. X1 represents matrices of explanatory variables common to both the equations. Z1 and Z2 represent matrices of instrument(s) for respective equations.

System equation set:

Stage 1: Reduced form equations:

Stage 2: Final Equations:

Step-3 involves generalized least squares (GLS) type estimation using the covariance matrix estimated in the second stage and with the instrumented values in place of the right-hand-side endogenous variable. The GLS accounts for the correlation structure in the disturbances across the equation (Green, Citation2012). Zellner and Theil (Citation1962) and Kmenta (Citation1971) offer a detailed discussion on these approaches.

4.3. Econometric model

This paper estimates the three equations using 3SLS simultaneous equations modeling approach. DIV, LEV, and COC are inter-linked and may suffer from endogeneity issue, making OLS estimator biased and inconsistent. We follow the classical form for estimation of system equations. With the three interdependent variables, each equation has a set of explanatory variables that capture the material characteristics of a firm. Thus, the 3SLS model has three equations, one equation for each endogenous variable. The model includes control variables, common to all the three equations and set of instruments, specific to each equation. Table presents the definitions of the variables used in the study.

Table 1. Variables definition. This table presents the definitions of the variables used in the study

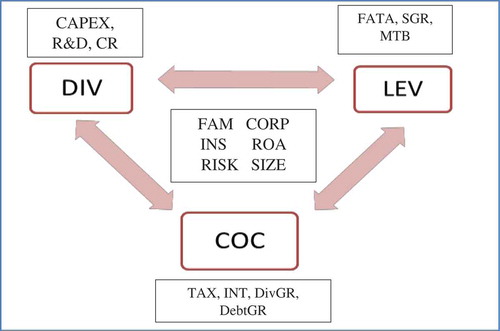

As discussed in the previous section, the influence of ownership structure (through agency cost framework), profitability, risk (uncertainty and bankruptcy), and size seem plausible for all three endogenous variables. Profitability leads to higher cash position, thus larger dividend payouts. A profitable firm has low financial leverage (pecking order theory) and lower cost of capital. A firm with high risk prefers to distribute less cash by means of dividend and costs of borrowing are high for such firms; therefore, managements may prefer to keep low debt. Impact of size is just the opposite. Large and mature firms have low risk, higher profitability, and limited growth potential; consequently, size positively influences the dividend payout, lowers the COC and enables them to raise a large amount of external capital, including debt finance. Figure depicts interrelationship diagram of dividends, leverage, and cost of capital along with other key variables.

We have added a set of exogenous variables (instruments), specific to each system equation as required for structural system model. The capex-to-total assets ratio (CAPEX) and research and development expense-to-total assets (R&D) capture the investment opportunity set of a firm. Free cash flow theory suggests dividend having a negative association with CAPEX and R&D. Current ratio (CR) measures the firms’ liquidity. We posit a positive relation with dividend payout, as high liquidity position reduces distress to meet financial obligations and may help a firm in maintaining high dividend payout. We select CAPEX and R&D as instruments for dividend equation as they have a direct impact over cash flow, and CR provides liquidity position of a firm, vital for cash dividends.

DIV Model:

Fixed assets-to-total assets ratio (FATA), sales growth rate (SGR), and market-to-book (MTB) value are included to the leverage equation. The FATA mirrors possible use of assets in place as collateral for external borrowing (Scott, Citation1977). On the other hand, we anticipate that a firm having high SGR be in greater need of external debt, thus positively affecting the debt ratio. Further, the MTB captures the market value of the firm and its future growth potential. Varaiya, Kerin, and Weeks (Citation1987) document MTB as an equivalent measure of Tobin’s Q, a ratio of market value-to-replacement cost of assets. Myers (Citation1977) documents that a firm, deriving significant value from potential future growth, is likely to have higher debt-related agency problems. We add these parameters (FATA, MTB, and SGR) to leverage equation as they indicate the requirement and position of a firm to raise capital.

LEV Model:

We include tax-to-sales ratio (TAX), interest-to-EBIT ratio (INT), dividend growth rate (DivGR), and debt growth rate (DebtGR) to COC equation. In combination with MM (Citation1963), we posit a negative relation between TAX and COC. For a profitable firm, high tax ratio enhances interest shield and debt potential for the firm, thereby reducing the cost of capital, ceteris paribus. Further, high-interest coverage ratio (low INT) suggests better financial health of a firm, thereby lower COC. Thus, we posit a positive relation between INT and COC. Signaling theory suggest a positive relation between DivGR and COC. Alternatively, high dividend payout requires an increased need of replenishing capital, thereby increasing COC. Similarly, high DebtGR entails more and frequent capital market tapping, thus enhances COC. DivGR and DebtGR suggest variation in average COC because of additional dividends and new debts.

COC Model:

5. Empirical results and analysis

5.1. Summary statistics

Table provides descriptive statistics of the key variables. The average dividend payouts are 15.41%, 17.77%, 13.83%, and 12.58% for aggregate, widely held, family, and family-controlled firms, respectively. The average debt ratios are 22.44%, 18.92%, 24.79%, and 24.09% for aggregate, widely held, family, and family-controlled firms, respectively. Similarly, the average cost of capital for the four groups are 5.90%, 6.75%, 5.33%, and 4.84%, respectively. These parameters confirm that family firms have low dividend payout, higher debt ratio and lower cost of capital vis-à-vis widely held firms, which are consistent with hypotheses (1a, 1b, and 1c). Low dividend payout and high debt ratio for family firms, supports findings of Mulyani et al. (Citation2016) for Indonesian family firms. Profitability measured by return on assets (ROA) is lower for family firms. Liquidity, as measured by the current ratio (CR) is higher for family firms compared to widely held firms. As expected, average firm size and market value ratio (MTB) are higher for widely held firms than that of family firms, showing ownership diffusion and economic value addition with maturity. Lower value of MTB for family and family-controlled firms suggest information asymmetry leading to value erosion.

Table 2. Variables: descriptive statistics

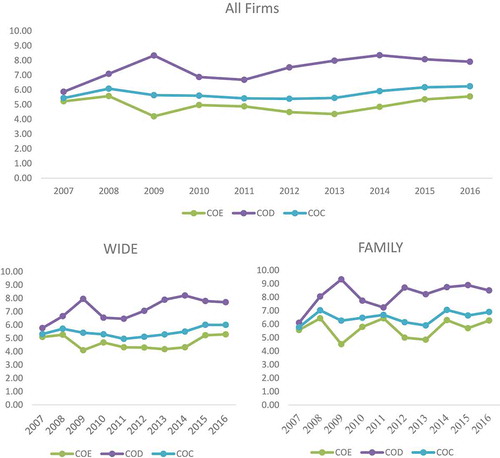

Figure provides yearly average COE, COD, and COC graphs for sample firms at an aggregate level, widely held firms, and family firms, respectively. These graphs show that COE decreased whereas COD increased over the years for sample groups. In addition, increase in COD is more than the decrease in COE. However, average COC increased marginally from the year 2007 through 2016.

Figure 1. Interdependencies among policy variables.

This figure presents the interrelationship diagram between dividend, leverage, and cost of capital along with the common variables influencing the three policy decisions and other key variables affecting a specific policy decision. DIV, LEV, and COC are the policy-related variables, which indicate the dividend payout ratio, debt ratio, and cost of capital, respectively. FAM, CORP, INS, ROA, RISK, and SIZE are common variables affecting the three policy decisions. FAM, CORP, and INS represent ownership proportion held by the family, corporate, institutional investors group, respectively. ROA, RISK, and SIZE specify profitability, operating risk, and firm size, respectively. CAPEX, R&D, and CR are specific to dividend decision, which denote investment, research and development expense ratio, and current ratio, respectively. Leverage specific variables are FATA, SGR, and MTB representing tangibility, growth in net sales (YoY), and market-to-book ratio, respectively. TAX, INT, DivGR, and DebtGR symbolize, tax ratio, interest ratio, dividend growth rate, and debt growth rate, respectively. These factors are specific to the cost of capital. Table explains each variable.

5.2. Empirical findings

This section provides the empirical evidences of interdependencies between dividend payout, capital structure, and cost of capital for the sample groups (All firms, WIDE, FAMILY, and FAMCON) of Indian firms. The Breusch-Pagan (BP) test for the diagonal covariance matrix confirms the contemporaneous correlation between the three equations for all the sample groups. The BP test recommends the application of simultaneous equations modeling. The 3SLS regression is estimated using three system equations, one for each endogenous variable, namely, dividend-to-earnings before interests and taxes ratio (DIV), debt ratio (LEV), and cost of capital (COC).

The 3SLS, using system equations (DIV, LEV, and COC models) is estimated separately for each sample groups (aggregate, widely held firms, family firms, and family-controlled firms). However, the estimates are reported for dependent variable-wise (equation-wise) in Tables –. Thus, estimates of all the three system equations for each sample groups are presented in three different tables, in the same order.

Table 3. DIV model

Table reports the regression results of the DIV model (Equation 1) from 3SLS regression for the sample groups. The results reveal that debt ratio has a negative influence over dividend payout; however, the average cost of capital positively affects dividend payout, across sample groups. Family ownership is not significant at the aggregate level and for widely held firms, but positively influences the payout for family and family-controlled firms, consistent with the signaling hypothesis, but negates our proposition (hypothesis 2a). Corporate ownership and institutional ownership show a positive relation with a payout for the sample groups excluding widely held firms. Among family firms, the positive relation of family ownership with dividends indicates that family has a critical role in decisions and dividend serves as a source of income for them. Further, the negative influence of institutional for widely held firms suggests that institutions are long-term investors and prefer capital gain over dividends. The negative influence of profitability over dividends for all sample groups is contrary to signaling hypotheses wherein higher profits means better health of a firm and hence managements signal with increased dividends. However, higher dividends relate to lower retention, thereby lower return on assets. Operating risk, measured by deviation in operating income, is significant and positive for only family-controlled firms, thus provides no evidence for bankruptcy theory. Size is positive and significant for widely held firms, however significantly negative for family firms. It shows that in family firms, family ownership concentration plays deciding the role of level of dividend payouts. Similarly, CAPEX and R&D are significant and positive only for family firms and family-controlled firms. These findings fail to support the free cash flow hypothesis. Firm liquidity, measured by a current ratio, is positively affected dividends for groups WIDE and family firms, consistent with uncertainty hypothesis.

Table reports regression results of LEV model (Equation 2) from 3SLS regression for the sample groups. The results reveal that dividends negatively influence debt ratio, whereas, the average cost of capital positively affects debt ratio, across all sample groups. Family ownership is significant and positive across sample groups, consistent with hypothesis 2b. Corporate ownership and institutional ownership concentrations are significant (at 1%) only for widely held firms and have a negative relation with debt ratio. These two opposite behaviors of ownership structure show that family (reputation) acts as collateral for creditors as they are long-term investors and concerned with passing ownership control to the next generation (Anderson et al., Citation2003). Profitability and operating risk negatively influence the debt ratio. The negative influence of profitability on leverage supports pecking order theory, wherein new investment requirements are first availed with retained earnings and profitable firms use less debt. The negative impacts of risk support bankruptcy theory. The firm size, tangibility (fixed assets-to-total assets ratio) and sales growth rate, all positively impact debt ratio. These findings are consistent with the propositions that large firms have low risk, high proportion of fixed assets, and high sales growth require more capital including debt borrowing. MTB is negative at the aggregate level for family firms, suggesting less value for levered firms.

Table 4. LEV equation

Table reports the regression results of COC model (Equation 3) from 3SLS regression for the sample groups. The results reveal that dividends and leverage, both positively influence the average cost of capital for Indian firms, across sample groups. Family ownership is significant and negative for family and family-controlled firms, conforms to hypothesis 2c, suggesting the reputation of the family acting as collateral to get cheaper debt. Corporate and institutional ownership concentration, both have a positive influence over COC for the widely held firm; however, Institutional ownership (INS) is significant and negative for other three sample groups. It indicates that, for widely held firms, higher equity participation by corporate and institutional investors have expectation for a higher return, making COE high for these firms. Profitability positively influences the average cost of capital for all sample groups, which is contrary to our assumption that profitable firms have a lower cost of capital. Risk and size are not significant at 5% level for all sample groups. Dividend growth and debt growth negatively influence the cost of capital for widely held Indian firms, but they are not significant for other sample groups.

Table 5. COC equation

Tables – provide evidences for interdependencies among policy variables. Dividend and leverage show a two-way negative association. Further, dividend and leverage have a bidirectional and positive association with cost of capital. These evidences support our hypotheses (hypotheses 3a, 3b, and 3c).

5.3. Robustness test

The study employs two sets of robustness test. First, for parameter robustness, dividend-to- assets ratio and debt–equity ratio are used as alternative measures for dividends and leverage, respectively, to examine inter-linkages among policy decisions. Second, the time robustness is tested using three sets of three-year panel data (FY08-10, FY11-13, and FY14-16). The estimation provides robust and consistent results for inter-linkages between dividend, leverage, and cost of capital in both the cases (Appendix A1, A2, A3, and A4).

6. Summary and conclusions

The study employs a 3SLS estimation approach to examine the theoretical inter-linkage among dividend, leverage and capital structure, factoring the ownership structure. The evidence supports the proposition that dividend and capital structure policies are interlinked and revolves around the ownership structure. The empirical evidences of a bi-directional negative association between dividends and leverage provide leeway for the management to reduce agency problems between owners and creditors. The theoretical findings suggest that with leverage, cost of capital should decline; however, in the Indian context, our findings are contrary, indicating thereby, the possibility of improper management of debt or inefficiency of managers.

The evidences confirm that family ownership influences the dividend and capital structure policies decisions. For family-controlled firms, ownership control positively influences the dividend payout as dividends serve as a source of income for owner-managers. However, family ownership concentration shows positive influence over leverage and negative relation with cost of capital. In this context, the study provides evidences of lower cost of capital for family-controlled firms. These findings suggest that reputation through family control is one of the important collateral of family firms for the creditors.

The study provides several important contributions to the literature. Since researchers continue to explore the severity of agency problems, our analyses shed light on this issue by investigating joint determination of dividends and capital structure policy decisions, particularly among firms of emerging markets. For policymakers, the findings could serve to justify initiatives for better performance of a firm, especially family-controlled firms. By adopting investment and financing strategies, corporate managers can bring down the average cost of capital for widely held firms, and hence enhance shareholder wealth.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Abhinav Kumar Rajverma

Abhinav Kumar Rajverma and Rakesh Arrawatia are from Institute of Rural Management Anand, and Arun K. Misra and Abhijeet Chandra are from Vinod Gupta School of Management, Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur. The group’s key research activities include the causes and consequences of corporate finance, effects of financing arrangements, corporate governance, and valuation of emerging market firms. Corporate finance is the study of the investment, financing, and profit distribution policies of corporations. As family firms are dominant in emerging markets and corporations are at the center of economic activities – and hence the research activities of the group focus on ownership structure and touch every aspects of policy decisions. This study investigates issue related to entrenchment of minority shareholders by majority shareholders (family). The study selects dividend policy, capital structure, and cost of capital as three important parameters to examine their interdependencies and the issue (entrenchment).

References

- Aivazian, V., Booth, L., & Cleary, S. (2003). Do emerging market firms follow different dividend policies from US firms? Journal of Financial Research, 26(3), 371–25. doi: 10.1111/1475-6803.00064.

- Aivazian, V., Booth, L., & Cleary, S. (2006). Dividend smoothing and debt ratings. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 41(2), 439–453. doi:10.1017/S0022109000002131

- Allen, F., & Michaely, R. (2003). Payout policy. Handbook of the Economics of Finance, 1(1), 337–429.

- Anderson, R. C., Mansi, S. A., & Reeb, D. M. (2003). Founding family ownership and the agency cost of debt. Journal of Financial Economics, 68(2), 263–285. doi:10.1016/S0304-405X(03)00067-9

- Anderson, R. C., & Reeb, D. M. (2003). Founding‐family ownership and firm performance: Evidence from the S&P 500. The Journal of Finance, 58(3), 1301–1328. doi:10.1111/1540-6261.00567

- Andres, C. (2008). Large shareholders and firm performance – An empirical examination of founding-family ownership. The Journal of Corporate Finance, 14(4), 431–445. doi:10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2008.05.003

- Andres, C., Betzer, A., Goergen, M., & Renneboog, L. (2009). Dividend policy of German firms: A panel data analysis of partial adjustment models. Journal of Empirical Finance, 16(2), 175–187. doi:10.1016/j.jempfin.2008.08.002

- Baba, N. (2009). Increased presence of foreign investors and dividend policy of Japanese firms. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 17(2), 163–174. doi:10.1016/j.pacfin.2008.04.001

- Bathala, C., & Rao, S. (2005). An econometric model and empirical analysis of interrelationships between debt. Dividends and Cost of Capital. Metamorphosis: A Journal of Management Research, 4(1), 9–25.

- Berle, A. A., & Means, G. C. (1932). The modern corporation and private property. New York: Macmillan.

- Bernstein, P. L. (1998). The hidden risks in low payouts. Journal of Portfolio Management, 25(1), 1–9. doi:10.3905/jpm.25.1.1

- Bhattacharya, S. (1979). Imperfect information, dividend policy, and “The Bird in the Hand” fallacy. The Bell Journal of Economics, 10(1), 259–270. doi:10.2307/3003330

- Black, F. (1976). The dividend puzzle. Journal of Portfolio Management, 2(2), 72–77. doi:10.3905/jpm.1976.408558

- Booth, L., Aivazian, V., Demirguc‐Kunt, A., & Maksimovic, V. (2001). Capital structures in developing countries. The Journal of Finance, 56(1), 87–130. doi:10.1111/0022-1082.00320

- Brennan, M. J. (1970). Taxes, market valuation and corporate financial policy. National Tax Journal, 23(4), 417-427.

- Brennan, M. J., & Schwartz, E. S. (1978). Corporate income taxes, valuation, and the problem of optimal capital structure. Journal of Business, 51(1), 103–114. doi:10.1086/295987

- Burkhart, M., Panunzi, F., & Shleifer, A. (2003). Family firms. Journal of Finance, 58(5), 2167–2201. doi:10.1111/1540-6261.00601

- Chua, J. H., Chrisman, J. J., & Sharma, P. (1999). Defining the family business by behavior. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 23(1), 19–39.

- Claessens, S., Djankov, S., & Lang, L. H. (2000). The separation of ownership and control in East Asian corporations. Journal of Financial Economics, 58(1), 81–112. doi:10.1016/S0304-405X(00)00067-2

- DeAngelo, H., & DeAngelo, L. (2007). Capital structure, payout policy, and financial flexibility. Marshall school of business. Working Paper No. FBE 02-06. doi:10.2139/ssrn.916093

- Denis, D. J., & Osobov, I. (2008). Why do firms pay dividends? International evidence on the determinants of dividend policy. Journal of Financial Economics, 89(1), 62–82. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2007.06.006

- Easterbrook, F. H. (1984). Two agency cost explanations of dividends. The American Economic Review, 74(4), 650–659.

- Eddy, A., & Seifert, B. (1988). Firm size and dividend announcements. The Journal of Financial Research, 11(4), 295–302. doi:10.1111/jfir.1988.11.issue-4

- Faccio, M., & Lang, L. H. (2002). The ultimate ownership of Western European corporations. Journal of Financial Economics, 65(3), 365–395. doi:10.1016/S0304-405X(02)00146-0

- Faccio, M., Lang, L. H., & Young, L. (2001). Dividends and expropriation. The American Economic Review, 91(1), 54–78. doi:10.1257/aer.91.1.54

- Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (2000). Forecasting profitability and earnings. The Journal of Business, 73(2), 161–175. doi:10.1086/jb.2000.73.issue-2

- Gomez-Mejia, L. R., Nunez-Nickel, M., & Gutierrez, I. (2001). The role of family ties in agency contracts. Academy of Management Journal, 44(1), 81–95.

- Gordon, M. J. (1959). Dividends, earnings, and stock prices. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 41(2), 99–105. doi:10.2307/1927792

- Gordon, M. J. (1962). The investment, financing, and valuation of the corporation. Homewood, IL: Richard D. Irwin.

- Greene, W. H. (2012). Econometric analysis (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Gugler, K. (2003). Corporate governance, dividend payout policy, and the interrelation between dividends, R&D, and capital investment. Journal of Banking and Finance, 27(7), 1297–1321. doi:10.1016/S0378-4266(02)00258-3

- Gupta, A., & Banga, C. (2010). The determinants of corporate dividend policy. Decision, 37(2), 63–77.

- Hamada, R. S. (1972). The effect of the firm‘s capital structure on the systematic risk of common stocks. Journal of Finance, 27(2), 435–452. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.1972.tb00971.x

- Han, K. C., Lee, S. H., & Suk, D. Y. (1999). Institutional shareholders and dividends. Journal of Financial and Strategic Decisions, 12(1), 53–62.

- Jensen, G. R., Solberg, D. P., & Zorn, T. S. (1992). Simultaneous determination of insider ownership, debt, and dividend policies. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 27(2), 247–263. doi:10.2307/2331370

- Jensen, M. C. (1986). Agency cost of free cash flow. corporate finance, and takeovers. Corporate finance, and takeovers. American Economic Review, 76(2), 323–329.

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). The theory of firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. doi:10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X

- Kevin, S. (1992). Dividend policy: An analysis of some determinants. Finance India, 6(2), 253–259.

- Kmenta, J. (1971). Elements of econometrics. New York: The Macmillan Company.

- Kusnadi, Y. (2011). Do corporate governance mechanisms matter for cash holdings and firm value? Pacific Basin Finance Journal, 19(5), 554–570. doi:10.1016/j.pacfin.2011.04.002

- La Porta, R., Lopez de Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1998). Law and finance. Journal of Political Economy, 106(6), 1113–1155.

- La Porta, R., Lopez de Silanes, F., & Shleifer, A. (1999). Domestic institutional ownership around the world. Journal of Finance, 54(2), 471–517. doi:10.1111/0022-1082.00115

- Lintner, J. (1956). Distribution of incomes of corporations among dividends, retained earnings, and taxes. American Economic Review, 46(2), 97–113.

- Mahapatra, R. P., & Sahu, P. K. (1993). A note on determinants of corporate dividend behaviour in India ‒ An econometric analysis. Decision, 20(1), 1–12.

- Manos, R., Murinde, V., & Green, C. J. (2012). Dividend policy and business groups: Evidence from Indian firms. International Review of Economics and Finance, 21(1), 42–56. doi:10.1016/j.iref.2011.05.002

- Miller, M. H., & Modigliani, F. (1961). Dividend policy, growth, and the valuation of shares. Journal of Business, 34(4), 411–433. doi:10.1086/294442

- Miller, M. H., & Modigliani, F. (1966). Some estimates of the cost of capital to the electric utility industry, 1954-57. American Economic Review, 56(3), 333–391.

- Mitton, T. (2004). Corporate governance and dividend policy in emerging markets. Emerging Markets Review, 5(4), 409–426. doi:10.1016/j.ememar.2004.05.003

- Modigliani, F., & Miller, M. H. (1958). The cost of capital, corporation finance and the theory of investment. The American Economic Review, 48(3), 261–297.

- Modigliani, F., & Miller, M. H. (1963). Corporate income taxes and the cost of capital: A correction. The American Economic Review, 53(3), 433–443.

- Mulyani, E., Singh, H., & Mishra, S. (2016). Dividends, leverage, and family ownership in the emerging Indonesian market. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 43, 16–29. doi:10.1016/j.intfin.2016.03.004

- Myers, M., & Frank, B. (2004). The determinants of corporate dividend policy. Academy of Accounting and Financial Studies Journal, 8(3), 17–28.

- Myers, S. C. (1977). Determinants of corporate borrowing. Journal of Financial Economics, 5(2), 147-175.

- Myers, S. C. (2001). Capital Structure. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 15(2), 81–102. doi:10.1257/jep.15.2.81

- Myers, S. C., & Majluf, N. S. (1984). Corporate financing and investment decisions when firms have information that investors do not have. Journal of Financial Economics, 13(2), 187–221. doi:10.1016/0304-405X(84)90023-0

- Myers, S. C. (1984). The capital structure puzzle. The Journal of Finance, 39(3), 574–592. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.1984.tb03646.x

- Raghunathan, V., & Das, P. (1999). Corporate performance: Post liberalization. IUP Journal of Applied Finance, 5(2), 6–31.

- Rozeff, M. S. (1982). Growth, beta and agency costs as determinants of dividend payout ratios. Journal of Financial Research, 5(3), 249–259. doi:10.1111/jfir.1982.5.issue-3

- Scott, J. H. (1977). Bankruptcy, secured debt, and optimal capital structure. Journal of Finance, 32(1), 1–19. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.1977.tb03237.x

- Setia-Atmaja, L., Tanewski, G. A., & Skully, M. (2009). The role of dividends, debt and board structure in the governance of family controlled companies. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 36(7–8), 863–898. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5957.2009.02151.x

- Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1986). Large shareholders and corporate control. Journal of Political Economy, 94(3), 461–488. doi:10.1086/261385

- Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1997). A survey of corporate governance. Journal of Finance, 52(2), 737–783. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.1997.tb04820.x

- Titman, S., & Wessels, R. (1988). The determinants of capital structure choice. The Journal of Finance, 43(1), 1–19. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.1988.tb02585.x

- Truong, T., & Heaney, R. (2007). Largest shareholder and dividend policy around the world. Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 47(5), 667–687. doi:10.1016/j.qref.2007.09.002

- Varaiya, N., Kerin, R. A., & Weeks, D. (1987). The relationship between growth, profitability, and firm value. Strategic Management Journal, 8(5), 487–497. doi:10.1002/smj.v8.5

- Villalonga, B., & Amit, R. (2006). How do family ownership. control and management affect firm value? Journal of Financial Economics, 80(2), 385–417.

- Walter, J. E. (1956). Dividend policies and common stock prices. Journal of Finance, 11(1), 29–41. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.1956.tb00684.x

- Weston, J. F. (1963). A test of capital propositions. Southern Economic Journal, 30(2), 105–112. doi:10.2307/1055958

- Zellner, A., & Theil, H. (1962). Three-stage least squares: Simultaneous estimation of simultaneous equations. Econometrica, 30(1), 54–78. doi:10.2307/1911287

Appendices

Appendix A1. Parameter Robustness Test

This table presents the 3SLS regression estimates for system equations, where the coefficients are estimated by fitting the system equations of dividend, leverage, and cost of capital at the aggregate level. Three endogenous variables are dividend-to-total assets ratio (DIV/TA), debt-equity ratio (DE), and average cost of capital (COC). FAM, CORP, and INS represent ownership proportion held by the family, corporate and institutional investors group, respectively. ROA, RISK, and SIZE specify profitability, operating risk, and firm size, respectively. CAPEX, R&D, CR, FATA, and SGR denote investment, research, and development expense ratio, current ratio, tangibility, and growth in net sales (YoY), respectively. MTB, TAX, INT, DivGR, and DebtGR symbolize market-to-book ratio, tax ratio, interest ratio, dividend growth rate, and debt growth rate, respectively. Table explains each variable.

***, **, * denote statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% level, respectively.

Appendix A2.

Time Robustness: DIV equation

This table presents the 3SLS regression estimates for system model (Equation 1), where the coefficients are estimated by fitting the system equations of dividend payout ratio (DIV), debt ratio (LEV), and cost of capital (COC) for the time-periods (FY08-10, FY11-13, and FY14-16). FAM, CORP, and INS represent ownership proportion held by the family, corporate and institutional investors group, respectively. ROA, RISK, and SIZE specify profitability, operating risk, and firm size, respectively. CAPEX, R&D, and CR denote investment, research and development expense ratio, and current ratio, respectively. Table explains each variable.

***, **, * denote statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% level, respectively.

Appendix A3.

Time Robustness: LEV equation

This table presents the 3SLS regression estimates for system model (Equation 2), where the coefficients are estimated by fitting the system equations of dividend payout ratio (DIV), debt ratio (LEV), and cost of capital (COC) for the time-periods (FY08-10, FY11-13, and FY14-16). FAM, CORP, and INS represent ownership proportion held by the family, corporate and institutional investors group, respectively. ROA, RISK, and SIZE specify profitability, operating risk, and firm size, respectively. FATA, SGR, and MTB denote tangibility, growth in net sales (YoY), and market-to-book ratio, respectively. Table explains each variable.

***, **, * denote statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% level, respectively.

Appendix A4.

Time Robustness: COC equation

This table presents the 3SLS regression estimates for system model (Equation 3), where the coefficients are estimated by fitting the system equations of dividend payout ratio (DIV), debt ratio (LEV), and cost of capital (COC) for the time-periods (FY08-10, FY11-13, and FY14-16). FAM, CORP, and INS represent ownership proportion held by the family, corporate and institutional investors group, respectively. ROA, RISK, and SIZE specify profitability, operating risk, and firm size, respectively. TAX, INT, DivGR, and DebtGR symbolize tax ratio, interest ratio, dividend growth rate, and debt growth rate, respectively. Table explains each variable.

***, **, * denote statistical significance at the 1%, 5% and 10% level, respectively.