?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The issue of whether public debt is useful or harmful towards economic growth is one of the most prevailing debates in the literature with no consensus existing on the subject matter. The study employs the ARDL model to examine the long-run and short-run effects of public debt on economic growth for South African data spanning a period between 2002:q1 and 2016:q4. Our sensitivity analysis consists of re-estimating our empirical regressions using two sub-samples dataset corresponding to the post-crisis period (i.e. 2007:q3–2016:q4). All estimated regressions unanimously find negative debt–growth relationship, with the negative relationship strengthening in the post-crisis period. Overall, our empirical results have some useful ramifications towards fiscal policymakers.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Public debt is acquired once government’s expenditure exceeds its revenues and represents a negative fiscal policy stance. Since 1994, the South African government has embarked on path of reducing its debt level, which it has managed to successfully do so, until the global financial crisis of 2007, of which debt levels have been on an upward trend up. In our study, we investigate the relationship between public debt and economic growth for South Africa. In differing from previous studies on the subject, we particularly focus on the relationship between the budget deficit and economic growth with regard to the global financial crisis of 2007. Our empirical study finds a negative and significant relationship between the two variables and therefore serves a cautionary note to South African fiscal authorities to place more policy emphasis on lowering public debt levels as a measure of improving economic growth.

1. Introduction

Following the sub-prime crisis of 2007, a prominent area of much contention within the macroeconomic paradigm concerns the effects of government debt on economic growth. The financial turmoil of 2007, which arose as an outcome of the crashing of the US housing market and the subsequent failure of the US banking system, eventually led to the global recession period of 2009. Since then governments worldwide have battled to recuperate from the aftermath of the crisis, with a number of policymakers worldwide developing contingency plans dependent primarily on fiscal intervention. The global crisis and malaise have brought about large government debt positions that are more harmful than crowding out and this is illustrated by the sovereign debt default situations reached by several European countries that have required massive bail-outs by international financial institutions (Mabugu, Robichaud, Maisonnave, & Chitiga, Citation2013). So even though at face value it would appear that the adverse effects of the credit crunch have been more severe for Western and other industrialized economies, the effects of the crisis on developing countries certainly cannot be taken for granted.

Historically, African economies have been characterized by fiscal government who have acquired high debt levels owed to external creditors such as the International Development Association (IDA), African Development Bank (ADB), International Monetary Fund (IMF) and other international financial institutions. This dependence on debt as demonstrated by African economies resonates mainly due to the failure of governments in these countries to finance much required expenditure programmes solely through the collection of tax revenues. Therefore, African governments have been compelled to borrow mainly through the channels of issuing of bonds, treasury bills and other debt securities which are considered to be very safe financial instruments towards international investors. Consequentially, such government borrowing is intended to stimulate the economy by investing funds from foreign investors into the domestic economy. However, the overall cost of debt towards African government has been long of concern to academics and policymakers alike and the question of whether public debt is helpful or harmful towards economic growth lies at the centre of this debate. In particular, whilst it is acknowledged that public borrowing is inevitable towards the financing of fiscal activities in African economies, it is notable that severe debt management practices may outweigh any potential welfare benefits that could have been gained through such borrowing.

Thus in our study, we focus our empirical efforts on investigating the empirical relationship between government debt and economic growth for the South African economy using quarterly data spanning through the post-democratic period of 2002:q1 to 2016:q4. For the case of South Africa, as the largest and arguably the most developed economy in the Sub-Saharan African (SSA) region, the issue of the effects of debt on growth have been a lingering one. Since the democratic transition of 1994, fiscal authorities have been charged with the gruesome task of eradicating the social ills of the country. Since then government has successfully brought down the debt-to-GDP ratio down from 46% of GDP in 1994 to 22 percentage of GDP in 2007 whereas economic growth rates also significantly improved from roughly 3% in 1994 to 5.6% in 2006. However, the global financial crisis has caused debt levels to almost double from 23% of GDP in 2008 to 45% of GDP in 2015 whereas economic growth rates have slightly deteriorated from 3% in 2008 to 1.3% in 2015. In 2013, fiscal authorities implemented two main expenditure programmes, the New Growth Path (NGP) and the New Development Plan (NDP), which are focused on simultaneously improving economic growth rates and reducing debt-to-GDP ratios as part and parcel of a wider range of intermediate goals aimed at eradicating unemployment and poverty over the next couple of decades.

In differing from a majority of empirical studies previously conducted for the South African economy (i.e. Amoateng & Amoako-Adu (Citation1996); Fosu (Citation1999); Iyoha (Citation1999); Pattillo, Poirson, and Ricci (Citation2002); Hussain, Haque, and Igwike (Citation2015); Akinkunmi (Citation2017)), we contribute to the literature in three ways. Firstly, our study is country-specific study whereas previous studies have been panel based. This is noteworthy since the panel-based studies tend to generalize the findings from a singular regression estimate for a host of economies with varying country-specific characteristics. Secondly, unlike previous South African studies, we use the ARDL model which presents certain advantages in comparison to other conventional cointegration models such as Engle and Granger (Citation1987) and Johansen (Citation1991) techniques previously used. For instance, the integration properties of the time series is less of a concern under the ARDL framework which allows for cointegration relations between a mixture of I(0) and I(1) variables that perform exceptionally well with small sample sizes. Thirdly, in taking advantage of sample size properties of the ARDL model we spilt our sample period into a smaller sub-sample corresponding to the post-crisis period. By effect this enables us to examine the relationship between public debt and economic growth in South Africa for periods exclusively subsequent to the global financial crisis of 2007, which has not be done in previous empirical works. This is important as fiscal authorities have accumulated growing levels of government debt particularly in the post-crisis period and it may be possible that the debt–growth relationship established in previous studies may have altered due to the structural break caused by the crisis periods.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides an overview of government debt levels in South Africa since 1994. Section 3 presents the theoretical and empirical review of the associated literature. Section 4 outlines the empirical specifications and ARDL models used in our study. Section 5 presents the empirical data and results. The study is concluded in Section 6 mainly in the form of policy implications.

2. Overview of government debt in South Africa

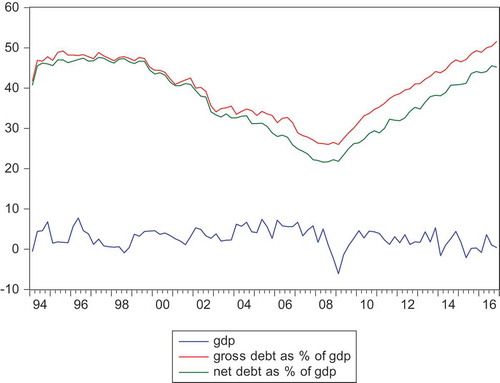

In entering a new democratic era in 1994, with the end of the former Apartheid regime, the ANC was faced with a large public debt mainly attributed to extensive borrowing and a foreign debt standstill imposed against South Africa in the 1980’s. In response, the South African government began implementing a series of large scale expenditure programs, with the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) of 1994 been the earliest of these programs, followed by the Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) policy of 1996 as well as the Accelerated and Shared Initiative for South Africa (ASGISA) of 2005. Part and parcel of these expenditure programmes was a commitment by the ANC government to reduce the high levels of government debt. To this end, National Treasury was judicially established in 1996 as an institution formally assigned with managing the fiscal debt of the country (Majam, Citation2017). Figure presents the time series plots of the net and gross debt levels expressed as a percentage of GDP between 1994 and 2017.

As can be observed, during the implementation of the RDP programme between 1994 and 1996, gross and net debt levels increased from 41.7 % and 40 % of GDP in 1994 to 48.2% and 46.7% of GDP in 1996 whereas GDP growth slightly improved from −0.4% to 1.6% within the same period. This increase in debt levels during these periods is attributed to the poor policy implementation and co-ordination under the RDP framework which did not produce expected GDP growth of over 3%. However, subsequent to the replacement of the RDP policy with its successor the GEAR policy in 1996, there began to be a noticeable decrease in the gross and net debt levels from 47.3% and 46.8% of GDP, respectively, in 1997 to 34.1% and 33.3% of GDP by 2003. This was accompanied with a slight increase in GDP growth from 1.2% to 2.2% which was still below the anticipated GDP growth rate of 3%. Nonetheless, in 2004 the GEAR policy was abandoned in favour of the ASGISA on the premise of ignoring microeconomic reforms which would address deeper social issues such as unemployment and income inequality (Phiri, Citation2017b). Initially, economic performance under the ASGISA framework was impressive with gross and net debt levels reducing from 34.1% and 33.3%, respectively, of GDP in 2004 to 26% and 21.8% of GDP in 2009. During this period GDP growth did reach highs of 7% between 2005 and 2006 which was mainly attributed to favourable trade developments.

However, the advent of the global financial crisis of 2008 and the ensuing global recession period of 2009 caused fiscal authorities to increase existing levels of debt and this coincided with a deteriorating macroeconomy especially in terms of economic growth which recorded negative levels of −6.1% in mid-2009. Further adding to government fiscal woes, international credit agencies such as downgraded South Africa’s sovereign risk rating to a negative outlook. As a result of this poor economic performance, the government abandoned the ASGISA policy in favour of the National Development Plan (NDP) and the NGP policies which were both adopted in 2013. Despite implementing these new policy programmes the government gross, net debt levels have increased from 31.6% and 26.4% of GDP in 2011 to 50.7% and 45% of GDP in 2016, and these high levels of debts were last experienced before the democratic elections of 1994. On the other hand, even though economic growth did recover to 2.8% in 2010, it has been on a downslope to lows of −0.8 in 2016. In summarizing the movements of fiscal debt and GDP, it appears as though there has been a positive correlation before the global financial crisis and a somewhat negative relationship subsequent to the financial crisis. Our empirical concern is whether these observations can be formally captured through the use of quantitative econometric techniques.

3. Literature review

From a theoretical standpoint, the effects of public debt on economic growth have been a matter of great controversy. Early classical economists, emphasized on the unproductiveness of the state on economic development as government intervention was thought to divert resources from the private sector to unproductive activities and such fiscal intervention was thought to be justifiable under severe circumstances such as during periods of wars or natural disasters (Tsoulfidis, Citation2007). Nevertheless, these earlier theories were branded as being inappropriate for modern economies and hence they were given little attention within the economics paradigm. Keynesian economics gained popularity during the Great Depression of 1936 and according to the Keynesian school of thought, budget deficits exert a crowding in or expansionary effect on the economy, which increases aggregate demand and, in turn, leads to higher private savings and investment (Van & Sudhipongpracha, Citation2015). However, such a positive debt–growth relationship was deemed to occur if the finance obtained from public borrowing is accompanied by “productive government spending’ such as public infrastructure expenditure.

By the mid-1980’s lingering fiscal debt levels became a widespread problem in third world countries to the extent that the World Bank had engaged creditor nations to re-schedule debt and engage in “involuntary lending” with debtor countries. At this time, the rationale for the shift in international debt management come courtesy of the debt overhang theory of Krugman (Citation1988) which argues on high debt acting as a tax on future output as well as reducing incentives for savings and investment. Hoffman and Reisen (Citation1991) criticized the debt overhang hypothesis by arguing that liquidity constraints as opposed to debt overhang are the cause of low levels of investment associated with high debt third World countries. In particular, the authors argue that the requirement to service debt reduces funds available for investment purposes; hence, a binding liquidity constraint on debt would restrain investment (Fosu, Citation1999). On the other hand, Barro (Citation1989) revitalized the Ricardian-equivalence theory by postulating a neutral effect of government debt on economic growth since the repayment of acquired government debt takes place through future taxation and this forces individuals to rationally increase their savings through acquiring government issued securities. In other words, individuals will sacrifice and reduce current consumption in order to pay for future tax burdens resulting in levels aggregate demand, interest rates and consumption being unaffected as if government had chosen to increase tax now and not later (Mosikari & Eita, Citation2017).

The late 1980s and early 1990s witnessed the emergence of a body of literature concerned with empirically examining the debt–growth relationship. Initially these empirical studies were focused on Latin American countries from which a consensus was being formed on the inverse relationship on public debt on economic growth (see Sachs (Citation1985), Hojman (Citation1986), Foxley (Citation1987), Pastor (Citation1989) and Geiger (Citation1990)). Thereafter, the works of Amoateng & Amoako-Adu (Citation1996), Fosu (Citation1999), Iyoha (Citation1999), Pattillo et al. (Citation2002) and more recently Hussain et al. (Citation2015) as well as Akinkunmi (Citation2017) have further supported these findings for African economies, inclusive of South Africa, by similarly unveiling a significant negative debt–growth relationship for the region. Reinhart and Rogoff (Citation2010) and Eberhardt and Presbitero (Citation2015) offer a different perspective for emerging economies, also inclusive of South Africa, by concluding that public debt is only harmful to economic growth once it exceeds some threshold. However, in considering that South Africa is arguably the most developed economy on the African continent, and has undertaken major political and economic reforms since the 1990’s, the findings from the reviewed studies can be criticized on their panel approach which raises concerns on the obtained results being biased towards the majority of lesser developed countries in the panel datasets. Moreover, these previous studies fail to account for important structural breaks such as the financial crisis of 2007–2008 in their empirical analysis, either by default of not employing time series which covers the crisis period or, as is the case of the most recent studies, have not empirical accounted for these breaks. Our current study intends on addressing these observed shortcomings in our empirical analysis.

4. Empirical framework

The theoretical basis for modelling the empirical relationship between public debt and economic growth comes about as a courtesy of the endogenous growth model introduced by Rommer (Citation1986). The model begins from the following “AK” production function:

where Y is production output, K is amount of physical capital and A is a positive constant. Endogenous growth theory emerged at a time when standard neoclassical theories were deemed unsatisfactory in explaining long-run economic growth. In differing from the neoclassical model of growth, the endogenous growth model is built on the more realistic assumption of constant returns to capital implying that physical capital is inclusive of other forms of reproducible capital like human capital (Hussein & Thirlwall, Citation2000). Our framework incorporates public debt in the growth function and, as previously discussed, the coefficient on the debt variable can be either positive (i.e. Keynesian hypothesis), negative (i.e. Debt overhang hypothesis) or insignificant (i.e. Ricardian-equivalence hypothesis). To also ensure that our regression does not fall prone to the omitted variables bias, we include two other significant growth determinants, namely, inflation and terms of trade. On one hand, inflation, in the South African context provides a direct measure of monetary policy outcomes on economic growth due to the Reserve Bank’s adopted inflation targeting mandate of 3–6%. From theoretical perspective the effects of inflation on growth has been predominately assumed to be negative although some early theorists argued on a positive relationship (Tobin, Citation1965) or an insignificant relationship (Sidrauski, Citation1967). On the other hand, the terms of trade variable provides the most convenient measure of degree of openness. Following the global liberalization of markets as experienced in the 1990’s, the role which trade activity plays on economic development has intensified. According to traditional growth theory, higher degree of trade openness should result in improved economic growth. Nevertheless, during periods of crisis, more open economies may be more vulnerable towards absorbing the adverse effects of the crisis hence openness may adversely affect growth during these periods. In putting together our theoretical specifics, the following augmented model regressions is specified:

where DEBT is a measure of government debt as a percentage of GDP which is proxied by either net debt (DEBT_N) or gross debt (DEBT_G), INV is investment, INF is inflation and TOT is terms of trade. In log-linearizing equation (2), we obtain the following empirical regression:

where the lower case letters represent the natural logarithms of the variables, β’s are regression coefficients and et is a well behaved error term. As mentioned earlier on, we employ the ARDL model of Pesaran, Shin, and Smith (Citation2001) as our choice of econometric modelling. We particularly estimate two different ARDL regressions. The first is a bivariate regression between public debt and economic growth as in Amoateng and Amoako-Adu (Citation1996). The two sets of bi-variate regressions corresponding to net debt (debt_n) and gross debt (debt_g) are specified in the following two sets of bi-variate ARDL and error correction model (ECM) regressions:

Whereas the multivariate regression derived from our “AK” endogenous model is specified as the following two sets of ARDL and error correction model (ECM) specifications:

where βi’s are the long-run regression coefficients, ϕi’s are the short-run coefficients and ECT’s are the error correction terms which measure the speed of adjustment back to steady-state equilibrium in the face of external shocks to the economy. The error correction terms are assumed to lie within an interval (0, −1) although there are some exceptional cases where the coefficient can be allowed to be lie between −1 and −2. Incidentally, significant negative error correction terms indicate long-run causality from the regressor to the regressand variable. However, prior to estimating our ARDL models it is imperative that one tests for cointegration effects. To this end, the study uses the bounds test for cointegration effects which tests the joint null hypothesis as:

And this is tested against the alternative hypothesis of significant ARDL cointegration effects i.e.

The test is tested with an F-statistics which is compared to the upper and lower bound critical values tabulated in Pesaran et al. (Citation2001). The decisions rule states that cointegration are assumed if the obtained F-statistics exceeds the upper bound of the critical statistics, no cointegration if the F-statistics lies below the lower bound of the critical value and is indecisive if the F-statistics lies in between the lower and upper critical bound.

5. Data and empirical results

5.1. Data description and unit root tests

The data used in our study has been collected from the Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) and South African Reserve Bank (SARB) online databases over a quarterly period of 2002:q1 to 2016:q4. The dataset consists of percentage change in gross domestic product at market prices (GDP), net government debt (debt_n), gross government debt (debt_g), total consumer price index (CPI) inflation (INF), gross domestic fixed investment as a percentage of GDP (INV) and terms of trade (TOT). Note that our study employs two measures of debt, those being, total gross debt and total net debt as a percentage of GDP. The summary statistics for the employed time series are reported in Table whilst the correlation matrices between gross debt, GDP and other growth determinants are reported in Table whilst those between net debt, GDP and other growth determinants are reported in Table .

Table 1. Summary statistics of the time series

Table 2. Correlation matrix of the time series

Table 3. Unit root tests results

The summary statistics reveal that both gross and net debt have averaged 37.20 and 32.74% of GDP, respectively, having reached maximums of 51.60 and 45.70% of GDP in 2016 whilst recording record lows of 26.00 and 21.70% of GDP, respectively, in 2008. We note from the relatively high standard deviations, the government debt has been quite volatile over the sample period. Economic growth, as measure by GDP has averaged 2.75, reaching a maximum of 7.4% in 2005 whilst reaching a low of −6.1% in 2009. We observe that the reported GDP averages are much lower than the 6% target commonly stipulated or prescribed in policy programmes. Encouragingly enough inflation has averaged 5.77, a statistic which falls right within the upper bound of the SARB’s 3–6% target. Lastly, domestic investment has averaged 17% as a share of GDP, a statistic which highlights the problem of low investment levels currently experienced in the country whilst the low growth average of 0.21 for terms of trade is of policy concern.

As can mutually observed from the correlation matrices reported in Tables and , all correlation coefficients produce negative estimates with the exception of the correlation between inflation and domestic investment whose correlation coefficient is positive. A majority of these correlations are plausible that is, from a theoretical perspective, we do notice that the negative correlation found between trade and growth contradicts conventional theory which hypothesizes on openness being beneficial for growth. Nevertheless, this seemingly “strange” negative correlation between trade and growth has been previously documented for South Africa in the works of Phiri (Citation2017a). Moreover, the correlation coefficients between the various variables produces moderate estimates hence ruling out any preliminary evidence of multicollinearity.

To check the stationarity of the underlying variables the study uses the ADF, PP and DF-GLS unit root tests which are performed with (i) an intercept and (ii) an intercept and a trend, and the results of this empirical exercise being reported in Table . As can be seen, the unit root test results produce mixed empirical evidences. For example, in their level, gross debt, net debt and terms of trade all fail to reject the unit root null hypothesis for all unit root tests regardless whether performed with an intercept or with a trend. On the other hand, inflation fails to reject the unit root hypothesis when all unit root tests are performed with an intercept and only for the PP test when performed with a trend. For GDP, on the DF-GLS test performed with either an intercept or with a trend manages to reject the unit root null hypothesis in its levels whilst the other test statistics fail to reject the unit root null hypothesis. Last, for investment in its levels, only the DF-GLs tests performed with an intercept manages to reject the unit root null hypothesis. Nevertheless, in their first differences, all the time series manage to reject the unit root hypothesis for a majority of the observed time series. There are, of course, some exceptions which exist in which the variables in the first difference do not reject the unit root null hypothesis, like for the investment variable when the test are performed with a trend and also concerning the gross debt as well as the net debt variables when the ADF and PP test are performed with an intercept as well as when the ADF is performed with a trend. Collectively, were are able to conclude that none of the observed time series is convincingly integrated of an order higher than I(1), hence permitting us to proceed with our ARDL empirical modelling.

5.2. ARDL modelling estimates

Having confirmed that our employed series are not integrated of an order equal to or greater than order I(2), we proceed to model our ARDL regressions. As a first step in this process, we conduct bounds test for cointegration on our four empirical specifications. The suitable lag length for each regression is based on the Schwarz information criterion (SIC). As can be deduced from the results reported in Table , all regression specifications significantly reject the null hypothesis of no ARDL cointegration relations amongst the variables. In particular, we find that each of the computed F-statistics exceeds the upper bound of the 1% critical level hence indicating cointegration effects at all significance levels. In light of these optimistic results, we can estimate the long-run and short-run ARDL relationships for each of our specified regressions.

Table 4. Bounds test for cointegration

Our empirical long-run and short-run ARDL estimates are presented in Table . As can be observed from the long-run estimates reported in Panel A of Table , the coefficient on public debt on all four regression is negative and significant at all critical levels. This piece of empirical evidence offers support in favour of the debt-overhang hypothesis for the South African economy and also joins a host of previous empirical studies which have found a similar negative debt–growth relationship for South African data (Amoateng & Amoako-Adu (Citation1996); Fosu (Citation1999); Iyoha (Citation1999); Pattillo et al. (Citation2002); Hussain et al. (Citation2015) and Akinkunmi (Citation2017)). We also notice that the remainder of the long-run coefficients are similarly negatively related with economic growth at all significant levels. Whilst the finding of a negative inflation-growth relationship is theoretically expected and is previously documented in the study (Hodge, Citation2002, Citation2006), the findings of a negative investment–growth and trade–growth relationship is contradictory to growth theory. However, we do not dismiss our empirical findings since former studies of Phiri (Citation2017a) and Were (Citation2015) found a similar negative investment–growth and trade–growth relations, respectively, for similar South African data. As discussed in Phiri (Citation2017a), the negative investment–growth relationship found for South Africa may be attributed to the high levels of government spending and public debt which crows out the potential positive effects of investment on economic growth. On the other hand, Were (Citation2015) attributes the negative trade–growth relationship to the current structure and pattern of trade in African countries which is unfavourable to these countries.

Table 5. Long run and short run ARDL estimates

In turning our attention to Panel B of Table which reports the short-run coefficients as well as the error correction terms for all estimated models, we firstly note that debt remains negatively and significantly related with growth across all estimated regressions. However, for the remaining variables in the multivariate regressions (i.e. models 2 and 4), the results differ between the different measures of public debt. In particular, when net debt is used (i.e. model 2) inflation is still negative and significantly related with growth whilst investment and terms of trade are positively related with growth. However, when gross debt is employed (i.e. model 4), both inflation and investment produce positive and statistically significant coefficients whilst terms of trade is negative and significant at all critical levels. We lastly, not that all error correction coefficients produce the correct negative and statistical significant estimates ranging between −0.48 and −0.74 implying that between 48 and 74% of deviations instigated by external shocks are corrected in each time period over the long-run.

5.3. Sensitivity analysis

To ensure the reliability of our empirical results we take caution and additionally investigate whether the global financial crisis has altered the cointegration relationship between government debt and economic growth. We find such an empirical exercise as being useful since previous studies have not directly considered whether a major structural event such as the global financial crisis may have altered the debt–growth relationship. Therefore, we shorten our empirical data corresponding to the post-crisis period (i.e. 2007:q3–2016:q4). As can be observed in Table , the ARDL bounds test for cointegration as performed on all four regressions in post-crisis sub-period reject the null hypothesis of no cointegration effects at all critical levels hence advocating for cointegration effects before and subsequent to the financial crisis.

Table 6. Bounds test for post-crisis period

The long-run and short-run ARDL estimates for the four regression in the post-crisis are reported in Table . In similarity to the results obtained for the full sample, the reported results in Panel A indicate that in both sub-samples public debt exerts a negative effect on economic growth. However, it is important to highlight that the coefficients on the full sample estimates are of lower absolute value compared to those of the post-crisis period, hence indicating that in the post-crisis period economic growth is more sensitivity to fiscal debt levels. Moreover, we also note that whilst both inflation and investment continue to exert a significantly negative effect on growth in the post-crisis period, we note that the sign on the coefficient on the investment variable switches from being negative and significant in the pre-crisis to being positive and significant in the post-crisis. This change in coefficient signs on the investment variable in the post-crisis is attributed to the increased levels of gross domestic fixed investment (especially in construction, transport and communication sectors) leading to the hosting of the World Cup in 2010.

Table 7. Long run and short run ARDL estimates (post-crisis)

5.4. Residual diagnostics and stability analysis

The last stage of our empirical analysis involves performing diagnostic tests on the estimated regressions corresponding to the full sample and post-crisis periods. Panels A and B of Table , respectively, reports the diagnostic tests (i.e. test for normality, serial correlation, heteroscedasticity and functional form) for the full sample, the pre-crisis and post-crisis periods. We note that all 12 estimated regressions from the entire study mutually reject the null hypothesis of non-normality, autocorrelation and heteroscedasticity, and this result is not surprising since we estimate our empirical regressions using a Newey–West coefficient covariance matrix. However, our RESET test results indicate that regressions functions of F(GDP Debt_n) and F(GDP Debt_n, INF, INV, TOT) for the full sample, as well as for functions F(GDP Debt_n, INF, INV, TOT) and F(GDP Debt_g, INF, INV, TOT) in the post-crisis sample. However, given that the remaining regressions fully comply with the classical regressions assumption, then the empirical results from these regressions can be interpreted with economic meaning.

Table 8. Residual diagnostics on estimated regressions

6. Conclusion

Following the global financial crisis of 2007 and the resulting global recession period of 2009, much debate has circulated around the issue of whether public debt would serve as a panacea towards improved economic growth. In this study, we investigate the case of the South African economy using post-democratic quarterly data spanning between 2002:q1 and 2016:q4. Our primary mode of empirical investigation is the ARDL cointegration approach of Pesaran et al. (Citation2001) which allows for modelling cointegration relations amongst a mixture of I(0) and I(1) time series. Our empirical results reveal that whilst gross public debt may be beneficial towards short-run economic growth, the long-term effects remain negative. Our results are strengthened by our sensitivity analysis which involved shortening the empirical data into a sub-samples corresponding to the post-financial crisis periods (2007:q3 to 2016:q4). These latter results reinforce our initial findings of an adverse relationship between public debt and economic growth, albeit a stronger negative relationship between the time series for periods subsequent to the financial crisis. Overall, our obtained empirical results have important implications towards policymakers.

The foremost policy implication derived from our study is that policymakers should be increasingly aware of acquiring higher levels of debt in the post-crisis period than they were for periods before the crisis. And in further considering the recent interest rate hikes by the Reserve Bank, more pressure is placed on government in financing future debt interest obligations and hence debt management practices, with a particular focus on financing risk more effectively, should form a vital part of fiscal policy design. Another implication from our study is that government needs to acquire alternative sources of funding in order to finance its increasing expenditure needs and may ultimately have to depend on increased levels of taxation in order to ensure a more balanced budget. Nevertheless, increase in taxes does not come without their own problems as they are seen to erode purchasing power from consumers and are seen as a burden to poor citizens. However, increases in taxes will eventually place downward pressure on inflation which, in turn, will put less pressure on the Reserve Bank to maintain high interest rates. Therefore, policymakers should also place emphasis on co-ordination of fiscal and monetary policies to ensure the future stability, of not only government debt, but also of future economic growth.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

N. Mhlaba

N. Mhlaba is a post-graduate student at the Department of Economics at the Nelson Mandela University, South Africa. She is the main author of this manuscript which is part of her graduate research. Her academic interests are public economics, financial economics and applied econometrics.

A. Phiri

A. Phiri, who is the corresponding author to this manuscript, is a senior lecturer at the Department of Economics at the Nelson Mandela University, South Africa who enjoys a wide range of publications in international journals with a research interests in macroeconomic policy, applied econometrics and financial economics.

References

- Akinkunmi, M. (2017). Empirical investigation of external debt-growth nexus in sub-Saharan Africa. African Research Review, 11(3), 142–15. doi:10.4314/afrrev.v11i3.14

- Amoateng, K., & Amoako-Adu, B. (1996). Economic growth, export and external debt causality: The case of African countries. Applied Economics, 28(1), 21–27. doi:10.1080/00036849600000003

- Barro, R. (1989). The Ricardian approach to budget deficits. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 3(2), 37–54. doi:10.1257/jep.3.2.37

- Eberhardt, M., & Presbitero, A. (2015). Public debt and growth: Heterogeneity and non-linearity. Journal of International Economics, 97(1), 45–58. doi:10.1016/j.jinteco.2015.04.005

- Engle, R. F., & Granger, C. (1987). Co-integration and error correction: Representation, estimation and testing. Econometrica, 55(2), 166–176. doi:10.2307/1913236

- Fosu, A. (1999). The external debt burden and economic growth in the 1980’s: Evidence from sub-Saharan Africa. Canadian Journal of Development Studies, 20(2), 307–318. doi:10.1080/02255189.1999.9669833

- Foxley, A. (1987). The foreign debt problem: The view from Latin America. International Journal of Political Economy, 17(1), 88–116.

- Geiger, L. (1990). Debt and economic development in Latin America. The Journal of Developing Areas, 24(2), 181–194.

- Hodge, D. (2002). Inflation versus unemployment in South Africa: Is there a trade-off? South African Journal of Economics, 70(3), 193–204. doi:10.1111/j.1813-6982.2002.tb01298.x

- Hodge, D. (2006). Inflation and growth in South Africa. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 30(2), 163–180. doi:10.1093/cje/bei051

- Hoffman, B., & Reisen, H. (1991). Some evidence on debt-related determinants on investment and consumption in heavily indebted countries”. Weltwirschaftliches Archiv, 127(2), 280–297.

- Hojman, D. (1986). The external debt contribution to output, employment, productivity and consumption: A model and an application to Chile. Economic Modelling, 3(1), 53–68. doi:10.1016/0264-9993(86)90012-X

- Hussain, E., Haque, M., & Igwike, R. (2015). Relationship between economic growth and debt: An empirical analysis for sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Economics and Political Economy, 2(2), 262–276.

- Hussein, K., & Thirlwall, A. (2000). The AK model of “New” growth theory is the Harrod-Domar growth equation: Investment and growth revisited. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 22(3), 427–435. doi:10.1080/01603477.2000.11490250

- Iyoha, M. (1999, March). External debt and economic growth in sub-Saharan African countries: An econometric study. AERC Research Paper No. 90.

- Johansen, S. (1991). Estimation and hypothesis of cointegation vectors in Gaussian vector autoregressive models. Econometrica, 59(6), 1551–1580. doi:10.2307/2938278

- Krugman, P. (1988). Financing or forgiving a debt overhang. Journal of Development Economics, 29(3), 253–268. doi:10.1016/0304-3878(88)90044-2

- Mabugu, R., Robichaud, V., Maisonnave, H., & Chitiga, M. (2013). Impact of fiscal policies in an intertemporal CGE model for South Africa. Economic Modelling, 31, 775–782. doi:10.1016/j.econmod.2013.01.019

- Majam, T. (2017). Challenges in the public debt management in South Africa: Critical considerations. Administratio Publica, 25(3), 195–209.

- Mosikari, T., & Eita, J. (2017). Empirical test of the Ricardian equivalence in the Kingdom of Lesotho. Cogent Economics and Finance, 5(1), 1–11. doi:10.1080/23322039.2017.1351674

- Pastor, M. (1989). Latin American, the debt crisis, and the international monetary fund. Latin American Perspectives, 16(1), 79–110. doi:10.1177/0094582X8901600105

- Pattillo, C., Poirson, H., & Ricci, R. (2002, April). External debt and growth. IMF Working Paper No. 02/69.

- Pesaran, M., Shin, Y., & Smith, R. (2001). Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationship. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 16(3), 174–189. doi:10.1002/jae.616

- Phiri, A. (2017a). Does military spending nonlinearly affect economic growth in South Africa? Defence and peace economics. (forthcoming). Taylor and Francis. doi: 10.1080/10242694.2017.1361272.

- Phiri, A. (2017b). Nonlinearities in Wagner’s law: Further evidence from South Africa. International Journal of Sustainable Economy, 9(3), 231–249. doi:10.1504/IJSE.2017.085066

- Reinhart, C., & Rogoff, K. (2010). Growth in a time of debt. American Economic Review, 100(2), 573–578. doi:10.1257/aer.100.2.573

- Rommer, P. (1986). Increasing returns and long-run growth. Journal of Political Economy, 94(5), 1002–1037. doi:10.1086/261420

- Sachs, J. (1985). External debt and macroeconomic performance in Latin America and East Asia. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2, 523–573. doi:10.2307/2534445

- Sidrauski, M. (1967). Rational choices and patterns of growth in a monetary economy. American Economic Review, 57(2), 534–544.

- Tobin, J. (1965). Money and economic growth. Econometrica, 33(4), 671–684. doi:10.2307/1910352

- Tsoulfidis, L. (2007). Classical economists and public debt. International Review of Economics, 54(1), 1–12. doi:10.1007/s12232-007-0003-8

- Van, V., & Sudhipongpracha, T. (2015). Exploring government budget deficit and economic growth: Evidence from Vietnam’s economic miracle. Asian Affairs: An American Review, 42(3), 127–148. doi:10.1080/00927678.2015.1048629

- Were, M. (2015). Differential effects of trade on economic growth and investment: A cross-country empirical investigation. Journal of African Trade, 2(1–2), 71–85. doi:10.1016/j.joat.2015.08.002