?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Sources of economic growth in Ghana have not been clear. Several studies have contributed to the finance and growth literature with little attention on remittances and the joint effect of financial sector development and remittances. This paper uses macrodata to examine the linkages between financial development, remittances and economic growth in Ghana. We estimate a dynamic heterogeneous Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) model to show that financial booms are not, in general, growth-enhancing, and a certain level of financial development can drag down economic growth in the long term and the combined effect of financial development and remittances should be of concern to policymakers.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Remittances and financial development have both been identified as growth boosters. Though the individual effects of remittances and financial development on growth have been explored in Ghana, little is known of the joint effect of the two variables. In addition, the study determined the threshold effect of financial development on economic in Ghana. The paper uses macro data to examine the linkages between financial development, remittances and economic growth in Ghana. We estimate an ARDL model to show that financial booms are not, in general, growth-enhancing and a certain level of financial development can hamper growth in the long term.

1. Introduction

Financial development and remittances have been identified as major drivers of growth especially in developing countries (Chowdhury, Citation2016; Nyamongoa, Misatib, Kipyegonb, & Ndirangu, Citation2012). By lowering the costs of accessing credit, a well-functioning financial market can help direct remittances to projects that yield the highest return and therefore enhance economic growth (Giuliano & Ruiz-Arranz, Citation2009). There is also the argument that remittances can be used as a substitute for inefficient or non-existent credit markets by helping local entrepreneurs bypass the lack of collateral or high lending costs and start productive activities.

Since the last quarter of the twentieth century, the inflow of remittances to developing countries has increased significantly (World Bank, Citation2014). In effect, remittances have become the second-largest source of external finance after foreign direct investment (see Aggarwal, Demirgüç-Kunt, & Peria, Citation2011; Giuliano & Ruiz-Arranz, Citation2009; Glytsos, Citation2005). In specifics, statistics from the World Bank (Citation2014) points out that over the past 40 years, total workers’ remittance inflows to developing countries rose from a modest US$0.3 billion in 1975 to more than US$404 billion in 2013 (Chowdhury, Citation2016). For instance, the World Bank (2013) projected that from 2013–2015, remittance inflows to developing economies was expected to grow at an average of 8.8% annually. Particularly, growth in remittances to low-income countries was projected to grow at a faster rate of 12.3 percent during this same period. This according to the report was because economic conditions in remittance-sending countries such as the United States were strengthened (World Bank, Citation2014; Chowdhury, Citation2016). With one-seventh of the world’s population migrating in search of better economic and social opportunities, remittance is expected to have some significant implications for economic development, especially in developing countries.

Since antiquity, the sources of growth have been debated upon in the literature yet the ever-changing drivers of growth means that the literature is not exhaustive. Among the classical sources of growth are surplus labour, physical capital investment, technological change, foreign aid, trade openness, resources, and foreign direct investment. Contemporary sources, on the other hand, include but not limited to innovations from research and development (R&D), remittances and financial development. In recent times, much emphasis has been laid on the possible effects of financial development and remittances on economic growth and inequality through job creation and poverty alleviation (Bang, Mitra, & Wunnava, Citation2016)

Before 1983, the financial system of Ghana was monopolized by state-owned banks such as Ghana Commercial Bank, Agricultural Development Bank, Bank for Housing and Construction, National Investment Bank and a few others. Competition was rare so the notion was that liberalisation of the financial system would breed competition (Bawumia, Citation2010). One of the reasons for liberalising the financial sector in 1983 was to introduce competition into the banking and non-banking financial sectors. Indeed, after 1983, the economy has witnessed the influx of foreign banks and more are yet to come. The liberalisation of the financial sector under Financial Sector Adjustment Programme (FINSAP) and Financial Sector Strategic Plan (FINSSIP) also brought about improved savings, enhanced deposit mobilisation, financial deepening and supposedly competition in the banking sector (Bawumia, Citation2010). Ghana’s new Banking Act of 2004 also brought some changes into the banking industry including the elimination of secondary reserves and increase in minimum capital requirement among others. The tremendous development in the financial sector does not seem to be translated into the desired growth and poverty reduction in spite of some progress that have been achieved in recent times (Aryeetey, Harrigan, & Nissanke, Citation2000; Bawumia, Citation2010)

It is also imperative to note that the rate at which the financial sector develops matters. When the financial sector develops too fast, causing excessive financial sector deepening, it can lead to some form of instability in the sector. It may also encourage greater risk-taking and high leverage if poorly regulated and supervised. When it comes to financial deepening, there are speed limits. This puts a premium on developing good institutional and regulatory frameworks as financial development proceeds. Studies that have looked at financial sector development and economic growth have neglected the speed of adjustment in financial sector development and its impact on economic growth which is very important for policy implications.

For instance, Cecchetti and Kharroubi (Citation2015) argue that financial booms are not, in general, growth-enhancing and a certain level of financial development can be harmful to growth. This implies that there could be short-term and long-term effects of financial development on economic growth. However, this issue has not caught the attention of policymakers in Ghana. Similarly, the role of remittances on financial development in Ghana has not been given much attention may be due to its quantum in the past. Recent studies have looked at the impact of remittances on financial development in Africa (Karikari, Mensah, & Harvey, Citation2016) but how the pass-through affect growth rate was ignored. The study thus uses Ghana as a case study to test whether the magnitude of the joint effect of financial development and remittances inflow on growth is higher than their individual effects. This is premised on the fact that the potential of Ghana’s growing financial development and huge remittance inflow in spurring growth are only generally gleaned from public discourse without any empirical content.

2. Motivation and contribution to literature

In recent times, Ghana has witnessed increasing levels of remittance inflow. In the presence of financial sector development, remittance is expected to spur growth and improve the livelihoods of the masses, especially, the poor and vulnerable households. However, this has not been explored empirically. The study seeks to fill this void in the literature and particularly on Ghana on three counts. First, the study seeks to provide evidence for the joint effect of financial development and remittances on economic growth. Though policymakers may be aware of this from intuition, the magnitude of the joint effect is what they are not aware of. The joint effect of financial development and remittances if present indicates that growth is enhanced through policies that target financial sector development and remittances simultaneously. Second, the study seeks to estimate the threshold effect of financial development on economic growth. Lastly, instead of using the shallow proxies such as the ratio of total credit to GDP, the degree of monetisation in the economy, and the ratio of domestic credit to the private sector to GDP, for financial development, the study employs the current financial development index generated by the World Bank.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows. Section 3 presents survey of the literature on financial development and economic growth. Section 4 deals with estimation techniques and data issues. The results and discussion are presented in Section 5 and section 7 concludes the paper with some policy recommendations.

3. Literature survey

3.1. Financial development and economic growth

The impact of financial development on economic growth follows the ground-breaking work of Schumpeter (1911) who contends that a well-functioning financial system can spur technological innovations (growth) through efficient allocation of resource from unproductive to productive sectors. Patrick (Citation1966) followed suite with the supply-leading hypothesis arguing that the development of a robust financial sector can spur economic growth. Patrick (1966) was of the view that the creation of financial markets and their services well in advance of their demand will drive the non-financial (real) sector along the growth path, via the transfer of scarce resources from surplus-spending units to deficit-spending units according to the highest rates of return on investment (see Aryeetey et al., Citation2000). A variant view of the supply-leading potential of financial development and stock market liquidity on economic growth is the much recognised financial liberalisation argument by McKinnon (Citation1973) and Shaw (Citation1973). In the same vein, King and Levine (Citation1993) put forward an argument that financial development stimulates economic growth by increasing the rate of capital accumulation and by improving the efficiency with which economies use capital in the current and future periods. In addition, Calderon and Liu (Citation2003) contend that financial deepening contributes more to economic growth in developing countries than in industrial countries, especially to total factor productivity (TFP) growth.

Demirgüc-Kunt et al. (Citation2011) and Aggarwal et al. (Citation2011) find evidence of a positive relationship between remittances and financial sector development in developing countries. Particularly, Aggarwal et al. (Citation2011) argue that the level of financial development proxied by bank deposits to GDP and bank credit to GDP increased significantly following remittances inflow in most countries. In addition, Mundaca (Citation2009), using a dataset of 39 Latin American and Caribbean countries over the period 1970–2002, provided a convincing evidence of a complementarity between remittances and financial sector development in spurring growth. This evidence is corroborated by that of Nyamongo et al. (Citation2012) who found complementary effects of remittances and financial development on growth for a set of 36 Sub-Saharan African countries from 1980 to 2009.

In a more recent paper, Bang, Mitra, and Wunnava (Citation2015) used macrodata for the period 1986–2005 for 84 countries, with a strong argument that financial development measure such as financial reform could increase the flow of remittances via the investment motive (see Chowdhury, Citation2016). Bang et al. (Citation2015) further argue that the relaxation of direct credit programmes, credit ceilings and greater autonomy for the banking sector have positive impacts in attracting remittances, while development of security markets, quality enhancement of banking supervision and the removal of restrictions on interest rate determination have a favourable effect on remittances and growth in the long-run. Overall, the net impact of financial reforms on remittances is slightly negative in the long-run (Chowdhury, Citation2016).

In Ghana, empirical evidence on the finance–growth hypothesis is scanty except for the work of Adu, Marbuah, and Mensah (Citation2013), Quartey and Prah (2008) and Esso (Citation2010). For instance, Prah and Quartey (Citation2008) provide evidence in support of the demand-following hypothesis, using the growth of broad money to GDP ratio as a proxy for financial development. However, the challenge with these works is that they used pseudo measures of financial development such as the ratio of M2 to GDP, the ratio of M1 to M2+, and private sector credit to GDP.

Figure shows the trend of financial sector development and real GDP growth in Ghana over the study period. The relationship between financial development and growth rate was not between 1984 and 1994. For instance, while financial development fell from 13.68% to 8.54% in 1995, real GDP growth had a slight upsurge from 3.29% in 1994 to 4.11% in 1995. Beyond 1995, both variables remained relatively stable till the year 2003 where financial development experienced a sharp rise from 9.88% to 19.76% in 2004.

Figure 1. Trend of real GDP growth and financial development in Ghana.

Source: Authors' Construct, 2019

Furthermore, a clear disparity between the two variables can be identified between 2004 and 2015, where the country’s financial sector experienced a relatively stable trend, real GDP growth experienced some fluctuations recording its highest value (14.04%) in 2011. It is evident from the juxtaposition in Figure that even though it appears that financial development drives growth, the relationship has not been consistent and thus the effect of financial development of economic growth in Ghana still remains an empirical question.

3.2. The remittances-growth nexus

The impact of remittances on economic growth and poverty has been discussed extensively among academics and policymakers (see Gupta, Pattillo, & Wagh, Citation2009 & Jongwanich, Citation2007). Per the literature, the study provides a summary of the main channels through which remittances enhance growth in remittance-receiving countries. Fayissa and Nsiah (Citation2008) argued that remittances enhance economic growth in countries where financial systems are not very strong by providing an alternative way to financing investment thereby overcoming liquidity constraints. Iqbal and Abdus (Citation2005) shows that real GDP growth is positively correlated to workers’ remittances during 1972–73 to 2002–03 and workers’ remittances emerged to be the third important source of capital for economic growth in Pakistan. Adams and Page (Citation2005) also used data on remittances from 71 developing countries to analyse the effect of remittances on inequality and poverty and concluded that remittances reduce the level, depth and severity of poverty in the developing world significantly.

Figure presents the trend of real GDP growth and remittances for the study period. We realise that both variables showed a relatively stable trend from 1984 to 2006. In the year 2010, remittance recorded a low value of 0.42% while real GDP growth fared well with a value of 7.89. Furthermore, between the period 2010 and 2011, while remittances increased by 5.4%, real GDP growth rose to 14.04%. However, the increase in economic growth was attributed to the rebasing of the economy coupled with additional revenue from commercial exploration of crude oil (Aryeetey & Baah-Boateng, Citation2015). Beyond 2011, while remittances continued to increase reaching a peak of 13.27% in 2015, growth dipped to 3.9%.

3.3. Joint effect of financial development and remittances on economic growth

In a well-functioning financial sector, remittances are supposed to pass through the banking system before getting to the households for spending (Giuliano & Ruiz-Arranz, Citation2009). This implies that remittances work well through a developed financial system. Thus, the pass through effect of financial sector development and remittances could be higher relative to the individual effects. In spite of the above theoretical argument, the joint effect of financial sector development and remittances on economic growth has not been clear. While some authors believe that remittances affect growth via the financial sector others believe otherwise. For instance, Freund and Spatafora (Citation2008) and Giuliano and Ruiz-Arranz (Citation2009) noted that remittances can affect both investment and economic growth positively if channelled to projects with higher returns in the presence of well-functioning financial markets that tend to reduce transaction costs. Thus, remittances remove credit constraints, improve the allocation of capital and promote economic growth in less financially developed countries. On the contrary, if remittances do not ease liquidity constraints in the financial system or are not used for productive investments, the growth impact of remittances through financial sector channels may be weak as argued Nyamongo et al. (Citation2012).

4. Methodology

4.1. Data description and sources

The study uses macrodata spanning 1984 to 2015 for the empirical analysis. Annual data on real GDP growth, gross fixed capital formation (K), population (L), financial development (FD), remittances (RI), external debt (DEBT), and real exchange rate (REER) were obtained from the 2017 edition of the World Development Indicators (WDI). Data on government revenue (GR) was sourced from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) database while financial development was sourced from the Global Financial Development Database of the World Bank. Gross fixed capital formation was used as a proxy for capital. It was captured as the value of acquisitions of new or existing fixed assets (investment) by the government and the private sector as a percentage of GDP (Chowdhury, Citation2016). Population is defined as the International Labour Organisation’s total population between the ages 15 and 64 expressed as a percentage of total population (Giuliano & Ruiz-Arranz, Citation2009; Rao & Hassan, Citation2011). Public debt (DEBT) remains one of the major constraint to growth in Ghana due to its sustainability. External debt comprises all forms of aid (debt/liabilities) that require payment(s) of interest and/or principal by the debtor at some point(s) in the future and that are owed to residents of a country as a ratio of GDP (Aggarwal et al., Citation2011). Financial development (FD) in this study was an index generated by the World Bank group taking into account access, efficiency, depth, and stability of the financial system of a country thus making it a comprehensive measure of financial development. Remittance (RI) also comprises inflow of personal transfers and compensation of employees from abroad measured as a percentage of GDP. Two channels through which remittances spur growth have been identified in the literature, one has to do with the poverty-eradicating power of remittance through access to credit for small and medium scale enterprise establishment, and investment in interest-bearing assets. Financial Development (FD) is widely argued in the literature as being the backbone of SMEs as well as the provision of financial products and services which in turn spur growth. Like financial development, remittance is expected to boost growth (Giuliano & Ruiz-Arranz, Citation2009; Jongwanich, Citation2007; Nyamongo et al., Citation2012; Ratha, Citation2013). The study captured real GDP growth as the annual percentage changes in real output (Chowdhury, Citation2016). Real effective exchange rate is the nominal effective exchange rate divided by a price deflator (Gala, Citation2007; Rodrik, Citation2008). Furthermore, Government Revenue (GR) forms the central governments’ ability to finance developmental projects from internally generated resources. The variable was captured as a percentage of overall government revenue in a fiscal year to GDP (Afonso & Furceri, Citation2010; Akai & Sakata, Citation2002). Lastly, the interaction term for financial development and economic growth (FDRI) has gained popularity in the growth literature lately because of the perceived complementarity of the variables in boosting growth (Giuliano & Ruiz-Arranz, Citation2009; Nyamongo et al., Citation2012).

4.2. Theoretical and empirical models

Following Solow (Citation1956), the study adopts the neoclassical Aggregate Production Function (APF) which expresses the relationship between national output and the volume of inputs used in production. We express the APF as:

Where is the output,

is the Total Factor Productivity,

denotes capital, while

denotes labour. Total Factor Productivity (

captures some exogenous factors affecting growth other than labour and capital. Based on theoretical and empirical evidence, the study captures some major drivers of TFP in Ghana as:

Linking up equations (1) and (2), we obtain equation (3)

where RI is remittance, FD is financial development, FDRI is the financial development and remittances interaction, GR is government revenue, DEBT is public debt. K is capital, and L is the labour force.

Equation (3) can be modelled in econometric form as:

In conformity with the estimation technique used, equation (4) is double-logged as seen in equation (5)

From theory, the study expects that ,

,

,

,

,

while

4.3. The model

The varying length of maturity dates for investments in financial intermediaries and productivity levels of business born out of remittance receipts means that remittances inflows can have a short-term and long-term impact on growth. The study employed the Autoregressive Distributed Lag technique put forward by Pesaran, Shin, and Smith (Citation2001). The ARDL technique has two highly desirable properties. First, it has been shown to work well in small samples (see Bahmani-Oskooee & Hegerty, Citation2009; Kwesi Ofori, Obeng, & Armah, Citation2018). Secondly, it provides short-run estimates, long-run estimates, and a cointegration test within a single Ordinary Least Squares estimate.

First, following Pesaran et al. (Citation2001), an expression of the relationship between financial development, remittances and growth of output from equation (5) is expressed in the ARDL form as seen in equation (6)

Second, to determine the threshold effect of financial development on growth, we present a second ARDL model capturing the quadratic term of financial development in equation (7). This stem from economic intuition that over a certain level of financial development, growth could be hampered as fast-growing financial systems has the potency of causing a heating-up of the economy.

4.4. Results

This section presents the cointegration test, stationarity test as well as the short-term and long-term results.

4.5. Summary statistics

Table shows the summary statistics of all the variables. For instance, the average real GDP growth over the study period was 5.54 percent while that of financial development and remittances amounted to 0.14 and 1.35 respectively.

Table 1. Summary statistics

4.6. Test for stationarity

The Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) and Phillips Perron (PP) tests with a constant only, and a constant with trend option were used to test the unit root of each. This was done to ensure that none of the variables were integrated of an order above one before applying the ARDL technique. The null hypothesis of unit root for the variables was rejected at various levels of significance as specified in Tables and using the ADF and PP tests, respectively.

Table 2. ADF stationarity test

Table 3. Phillip perron stationarity test

4.7. Test for co-integration

The study tested for cointegration among the variables using the bounds testing approach. The two sets of asymptotic critical values assume that the regressors, on one hand, are purely I(1) and on the other hand, purely I(0). It is evident from that the F-statistics of 50.65 exceeds the upper bound of 3.9 signifying the presence of a long-run relationship among the variables.

The presence of a long-run relationship among the variables indicates the existence of an error correction mechanism. The study went ahead to estimate the long-run and short-run coefficients.

4.8. Long-run results

We observe from that capital, proxied by gross fixed capital formation was positive but statistically insignificant. However, the sign of the coefficient indicate that capital is an important component of growth. Labour force was also not statistically significant but positively related to economic growth. Financial sector development was also not statistically significant but carried the expected positive coefficient. Recent expansion of the financial industry and the various innovative products emerging from the industry could account for this positive sign of the coefficient although it is not significant. Remittance, on the other hand, was positive as expected and statistically significant at 10 percent suggesting that if remittances increase by 1 percent, it boosts growth by 0.26 percent. The combined effect of financial development and remittances was also positive and significant at 10 percent. The net effect (0.3%) of financial development and remittances is statistically significant at 10 percent meaning that a 1 percent increase in remittances given that the financial sector is well developed, enhances growth by 0.3 percent (see Appendix C). Further, there is empirical evidence to show the significance of government revenue on economic growth as 1 percent increase in overall revenue induces growth by approximately 0.44 percent. As expected, there is empirical evidence that debt is deleterious to growth in Ghana. A 1 percent increase in the country’s sovereign debt by 1 percent retards economic growth by 0.31 percent.

4.9. Short-run results

There is empirical evidence to show that the contemporaneous effect of capital on growth in Ghana is positive. From , we show that a 1 percent increase in capital stimulates economic growth by 0.1 percent. Labour force is also positive and statistically significant signifying that as the labour force increases by 1 percent, it induces growth by approximately 0.5 percent. Financial development is positive and statistically significant at 10 percent. We show that if the financial sector develops by 1 percent, it boosts growth by 0.1 percent. Remittance is also positive and statistically significant implying that a 1 percent increase in remittances increases economic growth by 0.4 percent. Further, we provide a strong empirical evidence to back our claim that in the short-run, the joint effect of financial development and remittances on growth is higher than their individual effects. We show that a 1 percent increase in remittances given financial development induces economic growth by 0.5 percent (See Appendix C). The lag for the joint effect also shows that a 1 percent increase in the previous year’s value of remittance given a financially developed economy leads to a reduction in economic growth by 0.3 percent. This counter intuitive finding could plausibly due to the time lag effect of remittances investments on growth. We observe a positive and statistically significant effect of government revenue on economic growth. There is empirical evidence that as government revenue increases by 1 percent, economic growth also increases by 0.12 percent. External debt carried the expected negative sign but there is no statistical evidence to back it in the short-run. The coefficient of the error correction, −0.61, implies that about 61 percent of the deviations from the long-run economic growth caused by previous periods shock converges back to the long-run equilibrium in the current period.

4.10. Discussion

The empirical analysis from Table shows the importance of remittances to economic growth. The results indicate that remittances are relevant contributors to the growth of Ghana’s economy over the study period. This may be due to remittances incomes flowing through formal financial channels other than being accumulated at home which is later or never invested in economic activities (World Bank, Citation2009C). Another plausible reason could be that with growing capital markets, remittances are essential in financing investment which could be viewed as a supplement to credit and insurance services offered by the well-functioning banking system. In this case, remittances are more likely to be channelled into growth-generating activities. These results corroborate the conclusions advanced by Fayissa and Nsiah (Citation2008) and Giuliano and Ruiz-Arranz (Citation2009).

Table 4. Bounds test result for co-integration (Model 1)

Table 5. ARDL results (Dependent variable is the log of real GDP growth)

Moreover, the joint effect of remittances and financial development proved growth inducing. The net effect of remittance flows into the economy given financial development is growth enhancing in the long-run but otherwise in the short-run. Intuitively, the result indicates that remittances and financial development can be used jointly to promote economic growth in a number of conceivable ways. Theoretically, when remittances enter the financial system, it strengthens the sector and makes funds available for investment. As these funds are channelled into productive investment, output increases overtime thereby boosting the expansion of the economy. Besides, remittances improve the welfare of both the residents receiving remittances and the Other Remaining Residents (ORRs) who do not migrate. This is because, while emigration rules out the possibility of trade in the market for non-traded goods between the migrants and the ORRs, it offers the latter group new trading opportunities in the same market with the families of migrants that attempt to increase their consumption. Such an effect should be even stronger if remittances flow towards the neediest groups of the population, thus contributing to poverty reduction. Second, by sending remittances, migrants play the role of financial intermediaries, enabling households and small-scale entrepreneurs to overcome credit constraints and imperfections in financial markets when they intend to invest in human and physical capital. It is not surprising that the combined effect of remittances and financial development is stronger than the individual effects. As evident in the literature and chiefly elaborated by Freund and Spatafora (Citation2008), and Giuliano and Ruiz-Arranz (Citation2009), remittances can boost investment and economic growth if channelled to projects with higher returns in the presence of well-functioning financial markets that tend to reduce transaction costs. In such cases, remittances may potentially contribute to raising the country’s long-run growth through higher rates of capital accumulation. The combined effect also shows that the synergy effect of financial development and remittances on growth which was higher than the individual effect of the variables. This calls for twin policies in terms of financial development and remittances to enhance economic growth. Thus, remittances should be encouraged to pass through the financial system into the country.

Consistent with the literature, the study finds that financial development facilitates economic growth in the short-run. One plausible reason is that a well-functioning financial market by lowering costs of conducting transactions may help channel remittances to projects that yield the highest return and thereby enhances growth. Improving the services provided by financial intermediaries such as banks and insurance companies will lead to enhancing productivity and result in improving total factor productivity leading to higher rates of growth.

The growth-enhancing effect of capital on growth stem from the theoretical conclusions of the Classical and Neo-classical Schools of thought that capital (thus plants, machinery and equipment, construction of roads, railways, and others such as schools, offices, hospitals, private residential dwellings, and commercial and industrial buildings) contributes positively to growth of output. The finding concurs that of Shaheen et al., (Citation2013) and Falki (Citation2009). It is also consistent with conclusions reached by Asiedu (Citation2013) in the case of Ghana. Ibrahim (2011) and Asiedu (2013) found a positive and statistically significant effect of capital on economic growth for Ghana.

Again, we find labour force to be growth inducing but only in the short-run. This supports the argument of the Neo-classicals on growth that the increase in the labour force (denoting the proportion of the total population aged between fifteen (15) and sixty-four (64) years) is the active and productive population which boost production as wages for informal workers are bid downwards. This is consistent with the argument of Jayaraman and Singh (Citation2007) and Ayibor (Citation2012) who asserted that there can be no growth achievement without the involvement of labour as a factor input. The result, however, contradicts the works of Frimpong and Oteng-Abayie (Citation2006) and Sakyi (Citation2011) that found a negative effect of labour on economic growth.

The evidence of a detrimental effect of debt on growth is not far-fetched as Ghana’s debt stock has continue to soar over the past one and half decades. In particular, a persistent high level of public debt can consequently trigger detrimental effects on capital accumulation and productivity, which potentially has a negative impact on economic growth (Kumar & Woo, Citation2010). An important channel through which debt affects growth is that of long-term interest rates. Indeed, if higher public financing needs push up sovereign debt yields, this may induce an increased net flow of funds out of the private sector into the public sector. This may lead to an increase in private interest rates and a decrease in private spending growth, both by households and firms (Elmendorf & Mankiw, Citation1999).

5. Robustness check for ARDL model 1

Table presents the diagnostic tests of the model. From Table , it is evident that the estimated model passes all the diagnostic tests indicating that the model is a fit of the data. It is clear that the model passes the test of misspecification, heteroscedasticity, normality and serial correlation

Table 6. Model diagnostics and stability tests (ARDL model 1)

6. Threshold effect of financial development on economic growth

Table presents the long-run coefficients for the analysis of the threshold effect of financial development on economic growth in Ghana. The results indicate the existence of a nonlinear relationship between financial development and economic growth as shown by the quadratic term of financial development. Thus, the presence of an inverted U-shape between the variables is confirmed by the positive coefficient of financial development which has a statistically significant effect on economic growth but up to a threshold, the effect declines eventually. A further evidence to prove the presence of the threshold effect is to determine the rate of change in equation (3) (see Appendix C). The ECT was negative confirming the co-integration relationship between the variables of interest (see Appendix A).

Table 7. Long-run result for Financial Development Threshold

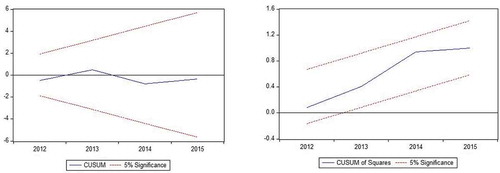

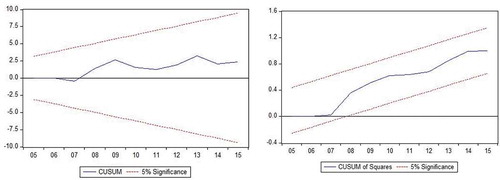

Diagnostic tests for the model as shown in Table in Appendix A indicate that the model does not show any problem of a serial correlation, heteroscedasticity, model misspecification, and normal distribution. Moreover, the Cumulative Sum of Recursive Residuals (CUSUM) and Cumulative Sum of Squared Recursive Residuals (CUSUMSQ) tests of stability in of Appendix A show convergence and no erratic or systematic changes in parameters.

7. Summary, conclusions, and policy recommendations

This paper examined the relationship between financial development, remittances and economic growth in Ghana. First, the focus of the study was to determine the joint effect of financial development and remittances on economic growth empirically. Second, the study estimated the level of financial development in Ghana beyond which growth can be hampered. The study concludes that the joint effect of financial development and remittances is higher than their individual effects. In addition, the study concludes from the threshold effect that development of Ghana's financial sector over 70 percent will drag growth down. A key policy implication derived from this study is that measures that attract remittances and those that will enhance the financial sector should be implemented simultaneously. For instance, the government should allow individuals to own repatriable foreign accounts with the local banks to grant them permission to make deposit into such accounts even when outside the country. However, effective monitoring of such accounts should be undertaken to ensure that such accounts are not used for or to facilitate money laundering activities. Further, the threshold effect of financial development on economic growth suggests that an over expansion of the financial sector could have negative consequences on growth thus care should be taken in order to avoid the adverse effect of over-expansion of the financial system.

8. Limitation of the study

Data on remittances that do not pass through the banking system is not available. We, therefore, used formal remittances which might underestimate the effect of remittances on growth.

Correction

This article was originally published with errors, which have now been corrected in the online version. Please see Correction (https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2019.1641683).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

James Atta Peprah

James Atta Peprah obtained his PhD degree in Economics from the University of Cape Coast, Ghana. Dr. Atta Peprah is currently the Head, Department of Applied Economics, School of Economics, University of Cape Coast. His research interest focuses on development economics, financial economics and enterprise development.

Isaac Kwesi Ofori

Isaac Kwesi Ofori holds MPhil. in Economics from the University of Cape Coast, Ghana. Mr. Ofori is a Demonstrator at the Department of Data Science and Economic Policy, School of Economics, University of Cape Coast. His research interests are public sector economics, international economics, and economic growth and development. He is an active member of the African Economic Research Consortium (AERC), Kenya.

Abel Nyarko Asomani

Abel Nyarko Asomani holds MPhil. in Economics from University of Cape Coast, Ghana. His research interests are economic growth and development, and monetary economics. He is an active member of the African Economic Research Consortium (AERC), Kenya.

References

- Adams, R. H., & Page, J. (2005). Do international migration and remittances reduce poverty in developing countries. Washington, DC, USA: World Bank.

- Adu, G., Marbuah, G., & Mensah, J. T. (2013). Financial development and economic growth in Ghana: Does the measure of financial development matter? Review of Development Finance, 3(4), 192–20. doi:10.1016/j.rdf.2013.11.001

- Afonso, A., & Furceri, D. (2010). Government size, composition, volatility and economic growth. European Journal of Political Economy, 26(4), 517–532. doi:10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2010.02.002

- Aggarwal, R., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Peria, M. S. M. (2011). Do remittances promote financial development? Journal of Development Economics, 96(2), 255–264. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2010.10.005

- Ahmed, A. D. (2006). The impact of financial liberalization policies: The case of Botswana. Journal of African Development, 1(7), 13–38.

- Akai, N., & Sakata, M. (2002). Fiscal decentralization contributes to economic growth: Evidence from state-level cross-section data for the United States. Journal of Urban Economics, 52(1), 93–108. doi:10.1016/S0094-1190(02)00018-9

- Aryeetey, E., Harrigan, J., & Nissanke, M. (Eds.). (2000). Economic reforms in Ghana: The miracle and the mirage. Africa World Press.

- Aryeetey, E., & Baah-Boateng, W. (2015). Understanding Ghana's growth success story and job creation challenges(No. 2015/140). WIDER Working Paper.

- Asiedu, E., Kalonda-Kanyama, I., Ndikumana, L., & Nti-Addae, A. (2013). Access to credit by firms in sub-Saharan Africa: How relevant is gender? American Economic Review, 103(3), 293-297.

- Ayibor, R. E. (2012). Trade Libralisation and Economic Growth in Ghana.

- Bahmani-Oskooee, M., & Hegerty, S. W. (2009). The effects of exchange-rate volatility on commodity trade between the United States and Mexico. Southern Economic Journal, 1019–1044.

- Bang, J. T., Mitra, A., & Wunnava, P. V. (2015). Financial liberalization and remittances: Recent panel evidence. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development, 24(8), 1077–1102. doi:10.1080/09638199.2014.1001772

- Bang, J. T., Mitra, A., & Wunnava, P. V. (2016). Do remittances improve income inequality? An instrumental variable quantile analysis of the Kenyan case. Economic Modelling, 58, 394–402. doi:10.1016/j.econmod.2016.04.004

- Bawumia, M. (2010). Monetary policy and financial sector reform in Africa: Ghana’s experience. La Vergne, TN: Lightning Source.

- Calderon, C., & Liu, L. (2003). The direction of causality between financial development and economic growth. Journal of Development Economics, 72(1), 321–334. doi:10.1016/S0304-3878(03)00079-8

- Cecchetti, S. G., & Kharroubi, E. (2015). Why does financial sector growth crowd out real economic growth? BIS Working Papers No 490.

- Chowdhury, M. (2016). Financial development, remittances and economic growth: Evidence using a dynamic panel estimation. Margin: the Journal of Applied Economic Research, 10(1), 35–54. doi:10.1177/0973801015612666

- De Gregorio, J., & Guidotti, P. E. (1995). Financial development and economic growth. World Development, 23(3), 433–448. doi:10.1016/0305-750X(94)00132-I

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Córdova, E. L., Peria, M. S. M., & Woodruff, C. (2011). Remittances and banking sector breadth and depth: Evidence from Mexico. Journal of Development Economics, 95(2), 229–241. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2010.04.002

- Demirguc-Kunt, A., & Levine, R. E. (2008). Finance financial sector policies, and Long Run Growth in M. Sperce Growth Commission Background paper, No 11 Washington, D. C. World Bank.

- Elmendorf, D. W., & Mankiw, N. G. (1999). Government debt. Handbook of Macroeconomics, 1, 1615-1669.

- Esso, L. J. (2010). Cointegrating and causal relationship between financial development and economic growth in ECOWAS countries. Journal of Economics and International Finance, 2(4), 036–048.

- Falki, N. (2009). Impact of foreign direct investment on economic growth in Pakistan. International Review of Business Research Papers, 5(5), 110-120.

- Fayissa, B., & Nsiah, C. (2008). The impact of remittances on economic growth and Development in Africa. Department of Economics and Finance Working Paper Series.

- Freund, C., & Spatafora, N. (2008). Remittances, transaction costs, and informality. Journal of Development Economics, 86(2), 356–366. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2007.09.002

- Frimpong, J. M., & Oteng-Abayie, E. F. (2008). Remittances, transaction costs, and informality. Journal of Development Economics, 86(2), 356–366. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2007.09.002

- Gala, P. (2007). Real exchange rate levels and economic development: Theoretical analysis and econometric evidence. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 32(2), 273–288. doi:10.1093/cje/bem042

- Giuliano, P., & Ruiz-Arranz, M. (2009). Remittances, financial development, and growth. Journal of Development Economics, 90(1), 144–152. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2008.10.005

- Glytsos, N. P. (2005). The contribution of remittances to growth: A dynamic approach and empirical analysis. Journal of Economic Studies, 32(6), 468–496. doi:10.1108/01443580510631379

- Gupta, S., Pattillo, C. A., & Wagh, S. (2009). Effect of remittances on poverty and financial development in Sub-Saharan Africa. World Development, 37(1), 104–115. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.05.007

- Iqbal, Z., & Abdus, S. (2005). The contribution of workers’ remittances to economic growth in Pakistan. Research Report. Pakistan Institute of Development Economics.

- Jayaraman, T. K., & Singh, B. (2007). Foreign direct investment and employment creation in Pacific Island countries: an empirical study of Fiji (No. 35). ARTNeT Working Paper Series.

- Jongwanich, J. (2007). Workers’ remittances, economic growth and poverty in developing Asia and the Pacific countries. United Nations Publications.

- Karikari, N. K., Mensah, S., & Harvey, S. K. (2016). Do remittances promote financial development in Africa? SpringerPlus, 5(1), 1011. doi:10.1186/s40064-016-2658-7

- King, R. G., & Levine, R. (1993). Finance and growth: Schumpeter might be right. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108, 717–738. doi:10.2307/2118406

- Kumar, M., & Woo, J. (2010). Public debt and growth. IMF working papers, 108, 1–47.

- Kwesi Ofori, I., Obeng, C. K., & Armah, M. K. (2018). Exchange rate volatility and tax revenue: Evidence from Ghana. Cogent Economics & Finance, 6(1), 1–17. doi:10.1080/23322039.2018.1537822

- Levine, R., & Zervos, S. (1998). Stock markets, banks, and economic growth. American Economic Review, 88, 537–558.

- McKinnon, R. I. (1973). Money and capital in economic development. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

- Mundaca, B. G. (2009). Remittances, financial market development, and economic growth: The case of Latin America and the Caribbean. Review of Development Economics, 13(2), 288–303. doi:10.1111/rode.2009.13.issue-2

- Nyamongo, E. M., Misati, R. N., Kipyegon, L., & Ndirangu, L. (2012). Remittances, financial development and economic growth in Africa. Journal of Economics and Business, 64(3), 240–260. doi:10.1016/j.jeconbus.2012.01.001

- Patrick, H. T. (1966). Financial development and economic growth in underdeveloped countries. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 14(2), 174-189.

- Pesaran, M. H., Shin, Y., & Smith, R. J. (2001). Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 16(3), 289–326. doi:10.1002/(ISSN)1099-1255

- Prah, F., & Quartey, P. (2008). Financial development and economic growth in Ghana: Is there a causal link? African Finance Journal, 10(1), 28–54.

- Rao, B. B., & Hassan, G. M. (2011). A panel data analysis of the growth effects of remittances. Economic Modelling, 28(1–2), 701–709. doi:10.1016/j.econmod.2010.05.011

- Ratha, D. (2013). The impact of remittances on economic growth and poverty reduction. Policy Brief, 8, 1–13.

- Rodrik, D. (2008). The real exchange rate and economic growth. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, (2008(2), 365–412.

- Sakyi, D. (2011). Trade openness, foreign aid and economic growth in post-liberalisation Ghana: An application of ARDL bounds test. Journal of Economics and International Finance, 3(3), 146-156.

- Shaw, E. S. (1973). Financial deepening and economic development. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Shaheen, S, Ali, M. M., Kauser, A., & Bashir, F. (2013). Impact of trade liberalization on economic growth in Pakistan, Interdisciplinary. Journal of Contemporary Research in Business, 5(5). Retrieved from: http://www.ijcrb.webs.com

- Solow, R. M. (1956). A contribution to the theory of economic growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 70(1), 65-94.

- Svirydzenka, K. (2016). Introducing a new broad-based index of financial development. International Monetary Fund.

- World Bank (2009C). Global Development Finance 2009. Charting a Global Recovery. Retrieved from: http://econ.worldbank.org/WBSITE/ EXTERNAL/EXTDEC/ EXTDEC PROSPECTS/EXTGDF/ EXTGDF2009/ 0,,menu PK:5924239~pagePK:64168427 ~piPK:64168435 ~theSite PK :5924232,00.html.

- World Bank (2014). Migration and remittances: Recent developments and outlook. In Migration and development brief (pp. 22).

APENDICES

APPENDIX A

Table A1. Bounds test result for co-integration (ARDL MODEL 2)

Table A2. Model diagnostics (ARDL MODEL 2)

APPENDIX B

Table B1. Short-run result for the threshold (Model 2)

APPENDIX C

Calculation the effect of the interaction between FD and RI and the threshold of FD

In this appendix, we demonstrate how the interaction between financial development (FD) and remittances (RI) are calculated. We also show how the turning point or the threshold effect of financial sector development is calculated.

1. Interaction between FD and RI (FDRI)

Long-run

Thus, the joint effect of FD and RI on economic growth is estimated at 0.3%.

Testing for the significance of the Interaction

FDRI = 0

F(1, 24) = 4.85

Prob > F = 0.0375**

Short-run

For FDRI:

For

2. Threshold Effect for Financial Development

First Order Condition:

. This implies that any expansion of the financial sector beyond 70% may contribute decline in economic growth.

Testing for the significance of the Coefficient

FD = 0

F(1, 24) = 11.94

Prob > F = 0.0021***

Second Order Condition: