?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Our main contribution in this paper consists of analyzing long-run interactions between structural policies and economic growth accounting for possible convergence. For this purpose, we are based on a sample of eight countries bordering the Mediterranean during the period 1975–2012. In fact, we used a technique based on panel ARDL methods which deals with the stationary series problem of different orders to monitor possible convergence in the long-run horizon. This method allows us to study potential long-term effects of structural economic policies on growth as well as capture the possible links between candidate variables and the trend of convergence in terms of per capita GDP. Our empirical results support convergence processes of GDP per capita in all the bordering Mediterranean countries. Moreover, we find that the increased number of secondary schools enrollment through public expenditure on education, greater economic openness, and fluid foreign direct investments stimulates economic growth.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Our interest in this paper is to participate in the construction of a platform for politicians and policymakers by emphasizing the importance of the financial sector in terms of convergence over a short and long-term horizon.

1. Introduction

The issue dealing with the origins and nature of differences as the growth rates and the living standards detected between countries has been a subject of frequent debates over the past few years. This literature raises the problem of decreasing factor productivity in a considerable number of developed economies during the 1970s years. This finding puts pressure on the classical theory and challenges the neoclassical growth model which advocates economic convergence. The rising doubt on the validity of the neoclassical analysis is largely associated with its fundamental hypothesis of technical progress or “fallen down from the sky”. This theory is based on a steadiness of growth rate and concludes to a unique growth trajectory that should be followed by any economies experiencing the same level of growth at a given time. Despite the fact that this current of thought gained ground during the 1980s and contributes to the enrichment of economic theory through explanation of differences and by identifying determinants of economic growth, it shows its limits in the recent years.

The history of economic events has been marked, in addition to the limits recorded to the classical models, by the emergence of new lines of research focusing on the development strategies and the state’s role in the process of economic liberalization pushed by neoliberals. In fact, this increasing research stream focuses on the new role of the state in the process of growth and in the economy in general. In this context, it has been developed endogenous growth theories and takes more interest since the mid-1980s (Romer, Citation1986, Citation1990; Lucas, Citation1988; Barro, Citation1990; Grossman & Helpman, Citation1994; King & Levine, Citation1993a, Citation1993b). These theories give a real boost to macroeconomic researches in terms of growth and represent a solution or guide to developing countries by showing how they can improve their long-term growth prospects.

Unlike the Solow (Citation1956) standard growth framework, endogenous growth theory insists on the role of economic policy in the growth process, which is neutral according to the Solow (Citation1956) model. These theories highlight the different mechanisms by which growth becomes endogenous and suggest a new role for the state’s economic policy at the center of economic activity. In particular, they focused on policy related to human capital development, innovation, technical progress, financial development and the opening of economies to external trade. With these theoretical advances, convergence has become conditional. Otherwise, by using economic policies, a country that is lagging behind can accelerate its growth and can catch up with the developed countries. Despite the fact that there are abundant researches studying convergences, they do not take into account the long-run effect of the state’s policy on convergence speed to a stationary state. Particularly, recent works highlight the importance of taking into account such indicators such as potential factors of possible economic catching up. Therefore, we seek to overcome certain limits of traditional economic growth as underlined by more recent endogenous growth theory through the introduction of new potential determinants of countries’ convergence. Otherwise, we test whether improved or appropriate economic policies may accelerate economic convergence. Accordingly, we used an Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ARDL) approach, which enables to overcome the previous techniques shortcomings. As a matter of fact, it is characterized by its advantage of studying the nonintegrated variables of the same order or do not have a long-run relationship according to a restricted VECM or unrestricted VAR regression.

Therefore, we seek to study the dynamics of growth and convergences in eight countries bordering the Mediterranean during the period 1975–2012 using a Solow-Swan model. Also, we are based on a recently developed dynamic panel heterogeneity analysis based on the technique introduced by Pesaran, Shin, and Smith (Citation1999) in order to assess convergence hypothesis validity in this region. This methodology allows us to produce consistent and efficient estimators of the parameters in the presence of a country-specific heterogeneity issue.

The rest of this work is organized as follows: In Section 2, we present a review of the literature concerning convergence and we detailed structural policies that can influence economic growth. In Section 3, we develop an econometric approach proposed to respond to our studying economic convergence objective. Section 4 provides discussions and interpretations of our main results. Finally, Section 5 concludes this study giving recommendations in terms of economic policies.

2. Literature overview

Our paper is at the crossroads of two strands of literature, one investigating the link between structural policy and economic growth and the other studying the models of convergence.

2.1. The importance of economic growth policies

2.1.1. Education policy

Lucas (Citation1988) took into account the role of human capital and integrated the decision of individuals to acquire knowledge. The core insight of the idea is that human capital can be accumulated as physical capital. However, unlike the latter, it is produced according to a process of increasing return relative to itself because it represents its own factor of production. In the Lucas model, growth rate depends only on the duration of human capital formation as it becomes positive as soon as the latter is positive. Thus, the State can conduct an education policy that favors the human capital formation and thereby promotes economic growth. The State may, in this sense, subsidize the training activity. It can, thus, distribute scholarships or take care of either all or a part of the cost of training; In other words, putting in place a public education system. Since private agents do not take into consideration the external effects that can be linked to human capital, the public intervention can be an incentive for them to invest more in the human capital formation. As Schubert (Citation1996) showed, “The State may give to each agent a subsidy proportionally to the time spent in the training process (opportunity cost) in order to compensate the shortfall in terms of wage”.

D’Autume (Citation1994) tried to examine the different education policies, especially when physical capital is needed to produce human capital. As a result, they propose to finance this physical educational capital by taxation. They find, moreover, that a subsidy to education has a positive influence on the growth rate. This makes it possible to correct the externality effects by encouraging each agent to acquire further experience and training which will have a positive impact on the other agents. The taxation of capital income, used to finance this subsidy, has no influence on the growth rate if it does not affect human capital, defined as the growth engine in the model. Benhabib and Spiegel (Citation1994) criticized the formulation of human capital as described in the model of Lucas (Citation1988). They noted that the impact of human capital on economic performance takes two forms: Either, it intervenes as a potential growth engine according to the terminology borrowed from the theories of endogenous growth (at the Lucas), or it is a vector for technological catch-up. Indeed, their approach is borrowed from Nelson and Phelps (Citation1966) approach and whence the Schumpeterian literature has been recently revived. This approach considers the stock of human capital to be the main growth engine. Thus, human capital stock determines the country’s ability to innovate and catch up the most developed neighboring countries. As a result, differences of growth rates between countries are explained or determined by divergences in terms of human capital stocks and its ability to enhance technical progress (Aghion & Howitt, Citation1998; Benhabib & Spiegel, Citation1994; Baldacci, Clements, Gupta, & Cui, Citation2008; Bhattacharyya, Citation2009; Lee & Kim, Citation2009; Benos & Karagiannis, Citation2010; Tsai, Hung, & Harriott, Citation2010;; Suri, Boozer, Ranis, & Stewart, Citation2011).

Whether in developed or developing countries, it is noted throughout that education policy seems to be a major strategic aspect in economic development. Certainly, the public authority is extensively involved in the educational choices. It frequently invests to provide individuals with a free-of-charge education system. It affects individual choices, too, through a system of taxation and subsidies. The reasons for this intervention are twofold. In the presence of externalities, the State can compensate both the market and individual choices in order to improve the efficiency of resource allocation and thus can increase the growth rate. It can also intervene in the interests of fairness and social justice.

2.1.2. Research and development policy

Technical progress has the nature of fostering the marginal productivity of factors and preventing its long-term abolition. In fact, endogenizing technical progress implies including explicitly a sector of “research and development” producing new technologies in the model. Knowledge, in this sense, is the consequence of not only accumulating physical capital (a rival factor) but also experiences (a non-rival factor). Therefore, there is an agreement on the particular role of technological innovation and on the importance of resources devoted to research and development.

The model of Romer (Citation1990) supported the idea developed by Lucas (Citation1988) which explains the reasons for non-convergence of many economies. Indeed, an economy with a high level of human capital will grow faster because it will devote more resources to the accumulation of knowledge. Nevertheless, a low level of human capital will lead to a reduction in the rate of growth since the existing human capital will be devoted to production. In this manner, underdevelopment exists in the model of Romer (Citation1990). Another important conclusion of Romer’s model is that when there is an integration of two identical countries, this will double human capital although it increases more than twice the growth rate; That is to say, the more the effectiveness of the capital increases, the more its size increases.

Based on this model, a number of economic policies able to influence the long-term growth rate can be identified in order to bring the competitive equilibrium closer to the social optimum. First, we note that the variable “human capital” may positively influence the economic growth. For that reason, Romer develops the idea of having a threshold based on the level of human capital which explains the international differences between growth rates. Thus, a policy of support to education seems to be favorable and effective on economic growth. The second possible economic policy is the subsidy for the purchase of intermediate goods. In other words, the State can stimulate the supply of these goods in order to eliminate the distortion effect due to monopoly pricing. Indeed, Romer points out that the difference between the equilibrium and the decentralized growth rate depends, heavily, on the monopoly margin. A policy that will reduce this monopoly margin has to increase the equilibrium growth rate to reach the optimal (decentralized) growth rate. Another economic policy embodied in research grants can be possible. In fact, granting more subsidies seems to be efficient in increasing economic growth. Thus, a research grant and public spending intended to promote the accumulation of technological capital in order to internalize the externality created by the current research on the productivity of future research seems to have a positive influence on economic growth. It encourages private agents to invest in research and development at a high level.

Developed countries give major priority on research and development expenditures in their budgets. They currently account for about 2% of GDP. However, in the case of developing countries, due to a lack of sufficient financing resources and their limited capacity to innovate, the portion is about 0.65% of GDP.

It is to be noted that South and East Mediterranean countries (SEMCs) tend to give no importance to research and development expenditure. They expect to emulate the various innovations available from developed countries. In order to have the internal capacities necessary for an effective use of this technology, it is essential to improve the level of skills and training of the population. Indeed, most SEMCs are not yet able to develop their own research and development activities to a sufficient level. Hence, they are turning towards foreign technologies. Their research and development systems should, in this sense, supplement and support the technology acquired through transfers or imports of capital goods. Thus, the adoption of foreign technologies requires a skilled and competent workforce capable of adapting technologies to the specificities of national economies, thereby improving the competitiveness of their industry.

2.1.3. Public infrastructure policy

In addition to taking account of external effects, the State has a direct influence on the efficiency of the private sector: public investment contributes intuitively to private productivity. Thus, Barro (Citation1990) developed a model highlighting the dual effects of taxation. It shows that public activities are also a source of self-sustaining growth. Therefore, government spending, such as the provision of public infrastructure, has a positive effect on the levels and growth rate of the economy and is considered complementary to private capital.

Glomm and Ravikumar (Citation1997) presented a dynamic model of general equilibrium depending on public expenditure. They try to study the effect of public spending on infrastructure, on education and on long-run growth. These expenditures are considered as inputs in the production function. The model identifies the positive effects of public investment in infrastructure (productive investment) on the long-run growth rate. They also show the dual effect of taxation on the growth rate, which makes it possible to define a so-called “optimal” size of the State.

Agenor (Citation2000) indicated that the lack of reliable empirical evidence for some studies about the relationship between fiscal policy and growth could be related to the non-linear nature of the relationship between these variables. In fact, growth increases when taxes and spending are at low levels and then growth falls as taxation effects exceed the beneficial effects of public goods. Then, public spending and economic growth are, on the one hand, positively linked when public spending is below the amount considered optimal, and, on the other hand, negatively linked when it is above and uncorrelated when public authorities provide the optimal amount of services. Empirical sectional studies were generally unable to explain this nonlinearity and may, therefore, be unable to detect it in the data.

Ultimately, it appears that investments in infrastructure, based on the results of the two approaches (primal or dual) and the developed theoretical models have a significant effect on private sector productivity and on economic growth. Although there are mixed results in some econometric studies, investment in road infrastructure and telecommunications is the most productive public capital investment because it supports private activities and consequently generates spillover effect.

2.1.4. Financial development policy

Different researches of the OECD Development Center, studying the case of a number of African countries, show the importance of a financial development policy to accelerate growth in these countries through a better mobilization of saving resources towards productive employment. The link between the development of financial intermediation and the experience of financial institutions, and the growth rate is obvious. Indeed, what differentiates rich countries from poor countries is the efficiency with which they use their resources. Precisely, it is the contribution of a financial system to growth that makes it possible to increase this efficiency.

Pagano (Citation1993) presented three channels of financial development transmission towards economic growth. The first channel is the allocation of savings to firms. In fact, in the process of the transformation of savings into investments, financial intermediation absorbs resources. Thus, a portion of the savings is lost between the lending and borrowing transactions which is related to the various fees that banks charge. In this context, Roubini and Sala-i-Martin (Citation1992) showed that, in the intermediation activity, there are charges on banks in the form of taxes (at the level of the reserve requirement, transaction taxes) or in the form of restrictive rules imposed on the financial system. Within this framework, a favorable economic policy to the development of the financial sector that will increase the efficiency of the latter in order to mobilize more savings towards investment will be crucial to increase the growth rate of the economy. Therefore, a developed and competitive financial system must be characterized by reduction in taxes and any other restrictions concerning its functioning. The second channel that can be attributed to financial intermediation is the allocation of resources to projects with high marginal productivity of capital. Indeed, financial intermediation acts positively on the productivity of capital, which influences growth, by two means: (i) collecting information that allows a better evaluation of investment projects, (ii) reducing Individual risks of the possibility of investing in bad projects by diversifying risks that can lead to better productivity. A fairly well-developed financial system has a positive effect on capital productivity, which is in line with Beck, Levine, and Loayza (Citation1999), who emphasized the significant influence of the development of banking sector on capital productivity. It is considered an essential factor in the development of investment and hence of economic growth. In this manner, a policy of financial system reforms will be beneficial for the economy. The third determinant of growth moves through the savings rate. For this, the view that the development of the financial sector has a positive influence on saving is being accepted, although this relationship is often somehow ambiguous. Thus, a savings policy could have a positive impact on long-term economic growth. In this way, Pagano tries to demonstrate that the channels through which financial factors influence growth are of crucial importance for a country that seeks to develop its financial system and improve its growth prospects. Ultimately, it can be noted that one of the requirements of domestic policy is the modernization of financial systems.

Many theoretical as well as empirical studies,based on endogenous growth theories, have demonstrated the existence of a positive correlation between financial development and economic growth (Greenwood & Jouanovic, Citation1990; Blackburn & Hung, Citation1993; De La Fuente & Marin, Citation1995; De Gregorio & Guidotti, Citation1995; Demirgüc-kunt & Levine, Citation1996; Levine and Zervos, Citation1998; Arestis & Demetriades, Citation1997; Levine, Loayza, & Beck, Citation2000; Abu-Bader & Abu-Qarn, Citation2008; Luintel, Khan, Arestis, & Theodoridis, Citation2008; Beck, Demirgus-Kuntand, & Levine, Citation2009; Lartey, Citation2010; Bittencourt, Citation2012; Abdelhafidh, Citation2013). Therefore, a financial development policy seems to be important for a better channeling and an efficient allocation of scarce resources towards productive employment. An economy with a repressed financial system struggles to develop. Thus, a developed financial system has a positive effect on economic growth.

2.1.5. Openness and economic integration policy

Being inspired from the models of endogenous growth, Gould and Ruffin (Citation1995) assumed that economic integration into the global market provides human capital, at the national level with externalities that are not accessed under the closure. As long as economies are not fully integrated with each other, increasing the level of human capital will increase the growth rate of the economy, if it opens its economy. Aubin (Citation1994), in an endogenous growth model, showed that the gains in terms of growth depend on the existence of a coordination between the different economic policies, that is to say, the existence of a public intervention seeking the optimum not within the framework of each of the economies taken separately but rather the union of these economies. Consequently, this confirms, in this sense, the advantage of regional economic integration. Indeed, openness exposes the national economy to foreign competition and leads to the selection of new and more efficient techniques, which accelerates productivity growth.

Several empirical studies have emphasized the importance of both the degree of openness and, more generally, the openness strategy in terms of growth. However, this empirical literature on openness and international trade faces several conceptual as well as data problems. Indeed, the problem is essentially linked to the benchmarking of trade policy, for which the barriers to trade, such as the countless tariff rates, must be translated into an index of openness and of foreign trade regime, etc. The literature is rich in empirical studies that highlight the positive link between the proxy variable of openness and the economic growth, such as in (Balassa, Citation1985; Dollar, Citation1992; Edwards, Citation1993; Coe; Helpman., Citation1995; Ben-David, Citation1996; Harrisson, Citation1996; Sachs & Warner, Citation1997; Pissarides, Citation1997; Markusen & Venables, Citation1999; Rodrik, Citation1998; Frankel & Romer, Citation1999; Greenaway, Morgan, & Wright, Citation2002; Kim, Lin, & Suen, Citation2010; Shahbaz & Rahman, Citation2012; Le & Tran-Nam, Citation2018). A wide and diverse range of studies comes to the same fundamental conclusion which is that free trade and openness to the outside world stimulate growth. In addition, the empirical literature invalidates the pessimistic view according to which trade liberalization undermines growth prospects and economic development; a fact that reinforces our analysis of the possible positive effect of a free trade policy. Indeed, economic growth is strengthened thanks to economies of scale, exposure to competition and the spread of knowledge.

Definitely, the benefits of regional economic integration are obvious. In the face of globalization and regionalization movements in the world, countries, such as the Southern and Eastern Mediterranean countries (SEMCs), find themselves obliged to integrate into a regional economic zone. As Rodrik (Citation2001) acknowledged: “there is a widespread agreement that openness to trade is the most suitable way known to man to reach economic growth”. He adds, repeating Fisher’s (2000) words, “Integrating into the global economy is the best way for a country to grow”. Moreover, Rodrik’s analysis (Citation2001) showed that “No country has developed successfully by turning its back on international trade and long-term capital flows. Also very few countries have experienced long periods of growth without increasing the share of trade in their domestic product”. In this regard, countries like the SEMCs must seek to achieve, successfully, international integration by implementing major structural reforms and signing association agreements with the European Union.

The SEMCs are convinced that they cannot achieve this integration effectively and remain at the margin only if they achieve high and sustainable levels of growth. The FEMISE report (Citation2002) insisted that the present growth process in the countries of the region must be transformed, to allow a greater per capita income in the long term. The report estimates the growth rate that should be reached as 7% per year. On this account, strengthening their growth prospects seems to be the challenge facing the SEMCs for the success of their economic integration (see Table ). Under these conditions, these countries hope to converge in terms of per capita growth rates with southern European countries.

Table 1. Effectiveness conditions for the euro-mediterranean partnership

3.2. Convergence models: the debate

The notion of convergence appears in the late 1980s in conjunction with the emergence of new theories of endogenous growth and especially with the availability of international comparative statistical databases. Since then, several papers have discussed the economic convergence phenomenon as well as the best approach to grasp it. A special area of focus will be on comparisons of national growth performance. Firstly, we propose to recall the definitions of convergence (in the literature we find several notions of convergence). Then, we will expose a model of convergence retained in this empirical literature.

There are three types of convergence in the literature. The first notion of convergence is the σ-convergence that is defined as the reduction of the dispersion of the per capita GDP distribution. In other words, we study the dynamic evolution of a dispersion indicator of the per capita GDP distribution in logarithm. This indicator is most commonly the variance or standard deviation, in cross-section, of the per capita GDP distribution. In this manner, for a given sample of countries, if the average deviations decrease between the initial date and the final date, within this framework, the hypothesis of σ convergence is accepted: the per capita GDP is said to converge towards the average value of the sample, a notion of convergence that was introduced by Sala-i-Martin (Citation1990).

The second notion of convergence is unconditional or absolute β-convergence. This convergence examines the relationship between the per capita growth rate and the initial level of per capita GDP. We try, then, to assess if the living standards of the various economies of poor countries tend to move closer by focusing on the catching-up of developed countries. It is said that there is unconditional β-convergence if, for a given period, the per capita growth rate of a country is higher than its initial per capita GDP.

The statistical estimation used to test this hypothesis consists in regressing, in cross-section, the growth rate, for example, per head, over the period, constantly and the initial GDP in log. Thus, if the initial GDP coefficient is negative and statistically significant, we accept the hypothesis of unconditionalβ-convergence.

Extensive empirical studies have tested this hypothesis. They confirm the non-validation of this notion of convergence. In fact, the divergence of countries’ experiences in terms of growth rates shows the non-validation of the neo-classical theory as formulated in the Solow growth model on the convergence of economies towards identical paths of equilibrium growth. Other so-called control variables have been introduced to explain the non-convergence, hence the notion of conditional β-convergence.

Among these works, one can cite that of Barro and Sala-i-Martin (Citation2004) that like most cross-sectional studies, they consider a regression of general form:

where is the growth rate in per capita GDP over a period (from 0 to T); ln y0 is the logarithm of the per capita GDP at time 0 and i identifies each country.

Barro and Sala-i-Martin (Citation2004) considered a group of N countries with a real per capita income, for the country i, given by . They have also considered the following regression model, in discrete time, of yi on a constant term, α0, and its delayed value:

where is a parameter to be estimated;

is a disruption term of mean-zero with constant variance

which captures temporary shocks of production technology, the average propensity to save. This term is also supposed to be independent over time and between countries. The previous equation can also be written as follows:

This equation shows that for the β-convergence to occur, the condition β > 0 must be satisfied. Indeed, β > 0 implies the inversion of the mean because the annual growth rate of the income per capita given by , is, inversely, related to

. The higher the value is, the greater the tendency converges.

In the long-run, assuming that , the expected real income per capita is:

where E(.) is the mathematical expectation operator.

Thus, conditional β-convergence occurs in a group of countries if the partial correlation between the growth rate of real income per capita and its initial level is negative. To illustrate this concept, Barro and Sala-i-Martin (Citation2004) considered a regression in sections of the per capita income growth rates relative to the initial per capita income and various other control variables summarized in the vectorwhich takes into consideration other determinants of income, such as inflation, openness, public investment, quality of human capital, and so on. The equation is given by:

Le Pen (Citation1997) defines conditional β-convergence as follows: “The inverse relationship between the per capita growth rate and the initial per capita GDP is verified provided that the countries in the sample reach common levels for certain economic and non-economic variables. These variables are supposed to control the heterogeneity of long-term trajectories”. Thus, differences in per capita incomes can be maintained or even strengthened over time. Similarly, the basic idea is that the differences observed are related to the initial structural differences between countries, hence the notion of “conditional” convergence. In this context, convergence is conditioned by the initial allocation of countries.

One of the major limitations of convergence of the cross-section approach is the hypothesis of an initial level of technology similar for all countries because the technology is unobservable (as Mankiw, Romer, and Weil (Citation1992) pointed out). If this hypothesis is not verified, then we are in the case of omission of a relevant variable correlated with the other explanatory variables, causing significant distortion in the set of coefficients of the convergence regression. A first solution consists in estimating the relationship on panel data by introducing individual heterogeneity in the form of fixed effects (Islam (Citation1995) and Berthélemy and Varoudakis (Citation1998)). Indeed, Islam (Citation1995) provided an approach in terms of panel data to regressions on conditional convergence that allows certain parameters of the production function to be different from one country to another. His approach, however, retains the assumption that the rate of technical progress is the same for all countries.

3. Data and methodology

We used annual data for eight countries bordering the Mediterranean during the period 1975–2012. We take the real per capita GDP as our dependent variable since we aim to access to the level of divergence between countries in terms of living standards taking into account inflation disparities. Otherwise, our main objective is to analyze the dynamics of growth and convergence in this region using the Barro (Citation1991) model. For the choice of the variables introduced as explanatory determinants of potential convergence, we are based on the set of variable making a large consensus by the most recent literature of endogenous growth theory. This dataset contains two mediating variables such as human capital (HC) accumulation measured by total secondary schools enrolment and domestic credit to the private sector in percent of GDP (PRIVY) as a proxy for financial development which stimulates economic growth (RPCGDP). In addition, we introduced openness (OPEN) and foreign direct investment (FDI) in order to control external influences on the macroeconomic stability and public sector activity.Footnote1 For example, an increased inflow of foreign capital declines the costs of R&D and so the costs of innovation (Borensztein,, De Gregorio,, & Lee, Citation1998) improving long-run growth. Data descriptions and resources are presented in Table 1 (see appendix)

For the choice of our methodology, we referred largely to the technique introduced by Pesaran et al. (Citation1999). This method is the more appropriate in studying this type of question such as county-convergence. Indeed, panel data methods are used to verify the convergence hypothesis in our sample. Particularly, the paper uses panel ARDL methods to produce consistent and efficient estimators of the parameters in the presence of country heterogeneity in contrast with previous studies based on variables integrated with the same order.Footnote2

3.1. Solow framework convergence

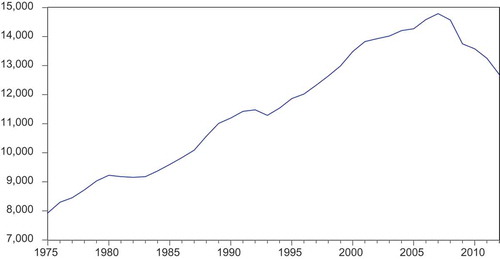

Growth theories provide a framework to assess the convergence hypothesis involved by the Solow-Swan augmented model. Barro (Citation1991) used this model to estimate the speed of convergence in 98 countries. The concept of σ-convergence differs from the β-convergence concept. The idea behind the σ-convergence is that the dispersion of real per capita GDP across countries tends to fall over time. We present below a figure investigating the σ-convergence assumption in CBM countries and presenting the path standard deviation of per capita distribution GDP.

Figure shows no clear indication of the presence of σ-convergence among CBM countries over the period 1975–2012. Indeed, it presents a period of increasing divergence (1975–2007), and also a period of a strong reduction in divergence (2007–2010). It can be shown that the dispersion of the standard deviation of real per capita GDP decreases when the speed of β-convergence increases.Footnote3 We can assume that the high dispersion of real per capita GDP, essentially before 2007, submitted a weak speed of adjustment of CBM countries toward a common steady-state way and a weak convergence of poor countries toward richer countries.

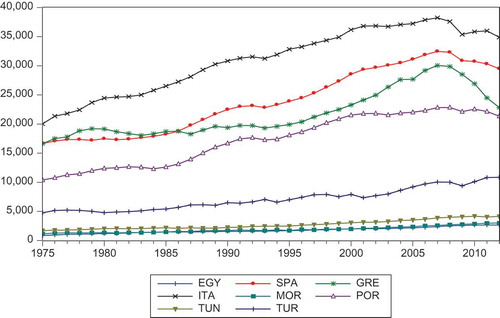

We present in the next figure the evolution of real per capita GDP in each country in CBM region. Figure shows that the initial conditions in CBM countries were very different with a real per capita GDP in Italia, the richest country in the region, a 23.5 times larger than in Egypt, the poorest country, in 1975 (the beginning of period). This figure shows weak progress in closing the income gap with the most wealthiest countries (Italy, Spain, and Greece). We conclude that there is, in general, an evidence of “catch-up” prediction of the Augmented Solow-Swan (ASS) model for this region, since the real per capita GDP of these countries has relatively increased by the end of the period in comparison with the beginning.

We can summarize that the observed conditional β-convergence also makes it probable that factor accumulation alone would not be enough to explain the growth differentials between countries in the CBM region. As a result, country-specific variables such as human capital accumulation, financial development, openness, and foreign direct investment could drive growth and explain its dispersion across CBM countries.

3.2. Alternative empirical models for estimating growth and convergence

In contrast with several studies in the literature reported on the growth and convergence, we use a dynamic panel data approach that makes possible to account for heterogeneity which cannot be feasible with cross-country and time series methods. Pesaran, Shin, and Smith (Citation1997) argued that the estimator of the speed of convergence obtained by Barro (Citation1991) is inconsistent because it accounts for homogeneity assumption across countries sample.

Furthermore, we adopt a recently developed dynamic panel heterogeneity analysis based on some techniques introduced by Pesaran et al. (Citation1999, Citation2004). Specifically, we present an Autoregressive Distributed Lag model (ARDL). Actually, we can use three different estimators such as: the Mean Group (MG), the Pooled Mean Group (PMG) and the Dynamic Fixed Effect (DFE) estimators in order to explore (1) both the long-run and short-run effects of human capital accumulation and financial development in CBM countries growthFootnote4 and also (2) to estimate the speed of convergence toward their steady-state level of real per capita GDP.Footnote5

4. Model specification

To address the drawbacks of the models presented in the neoclassical theory, we consider the following ARDL (p, q) model based on the specification of Pesaran et al. (Citation1999):

The dynamic heterogeneity in panel regression can be added into an error correction model using an ARDL (p, q) technique by subtracting the lagged dependent variable (GDP per capita) from both sides as follow:

where the dependent variable y is the real per capita GDP, X stands for a list of independent variables including the human capital, financial development, openness, and foreign direct investment indicators. Since, these factors are important in the sense that they affect resources mobilization and affectation to better uses. In other words, we explained in Subsection 2.1.4 how they positively influence human capital productivity through technologies transfer and skilling so we seek to study the importance of these variables in accelerating economic growth of countries. The parameters:

v and θ represent the short-run coefficients of lagged dependent and independent variables, respectively.

β and φ represent the long-run coefficients and speed adjustment to long-run steady-state coefficient, respectively.

η is a country-specific intercept.

The subscript i and t represent country and time, respectively.

We note that the term represents the long-run relationship between ln(y) and ln(X) (Error Correction term). According to Pesaran et al. (Citation1999) two assumptions to this long-run regression exist:

Assumption 1: the relationship between ln (y) and ln (X) defined by

exists if φ < 0 (φ speed of convergence), for each i = 1 to 8 and μ is a stationary process.

Assumption 2: the long-run coefficients on Xit, defined by

, are the same across countries, namely: δi = δ (long-run homogeneity assumption).

Equation (1) will give intuitions into the issue of β-convergence, since φ can be interpreted as the speed of convergence toward a common steady state. As noted above, alternative estimators have been proposed for the whole sample to predict this equation including, the PMG estimator and the MG estimators as well as the DFE estimator. The only difference between PMG and MG estimators is that the first impose homogeneity restriction on long-run coefficients across counties while maintaining heterogeneity for short-run dynamics. The second does not require a restriction; that is to say, it allows all coefficients to vary as well as to be heterogeneous in the short and long-run. However, according to Pesaran et al. (Citation1999), the PMG estimator offers an increase in the efficiency estimates as compared to the MG estimator under the long-run homogeneity. To test this assumption of long-run slope homogeneity, we use a Hausman (Citation1978) test to test whether there is a significant difference between PMG and MG or PMG and DFE estimators. Under the null (slope homogeneity), the PMG estimator is consistent and efficient. If the null hypothesis is not rejected, the PMG estimator is recommended.

4.1. Statistical properties of the variables

The basic statistics of Human capital, financial development, openness, foreign direct investment, and economic growth are given in Table .

Table 2. Basic statistics

4.2. Results and discussions

4.2.1. Unit root test

Since the ARDL model is not applicable for series exceeding an order of integration equals 2, we apply a unit root test to make sure that series is I(0) or I(1) (Pesaran and Smith (Citation1995), Pesaran et al. (Citation1999)). Since our data are unbalanced, we first employ two different types of panel unit root tests: the Im, Pesaran, and Shin (IPS) test andADF-Fisher (ADF) test.

The table below reports both the IPS and ADF unit root tests.

Our data include a time period which is fairly long (38 years), we further applied a unit root test with constant and trend in level and also the first difference. The test results of IPS and ADF in Table show that the null hypothesis of unit root cannot be rejected for real per capita GDP, human capital and financial development in level. On the other hand, both the variables trade openness and foreign direct investment are stationary in level with constant and trend.

Table 3. Panel unit root tests results

The existence of unit root in the real per capita GDP provides that the deviations of this variable from its steady state-level are permanent rather than transitory [Wan (Citation2004)].

In summary, we notice that our data suffers from either I(0) or I(1) which allows us the possibility to estimate both short-run and long-run relationship between economic growth and human capital using a Panel ARDL approach.

4.2.2. Panel ARDL estimates

The estimation of the Augmented Solow-Swan (ASS) model for CBM zone is conducted using an Autoregressive Distributed Lag model ARDL (1,1,1,1,1).

Table reports the results based on the Pooled Mean Group estimator. The equations for the long-run relationship between GDP growth and human capital accumulation were calculated for each country. From these results, the MG was estimated from the unrestricted country by country estimation.Footnote6 Coefficients of MG estimator are the average of country-specific parameters and PMG coefficients are restricted to be the same across countries. Hence, the comparison between the PMG (long-run slope homogeneity) and MG (long-run slope heterogeneity) estimates results show how the empirical estimations of the growth model are sensitive to different estimations techniques.

Table 4. PMG estimates and MG estimates for CBM region

According to the Hausman test,Footnote7 we accept the PMG as a consistent and efficient estimator. In line with the ASS model, the PMG estimator results indicate the existence of a strong relationship between economic growth and human capital in CBM countries, in the short and long-run. As one would not expect, we can notice that the long-run marginal effect of human capital on real per capita GDP growth is of the same magnitude as in short-term impact. Indeed, both the long-run and short-term human capital elasticity of real per capita is estimated at 66%.Footnote8 Openness appeared to be a strong driving force of growth in line with endogenous growth models. The Openness elasticity of real per capita GDP is estimated at 92% in the long term and 10% in short-run. The financial development does not have a significant impact on real per capita GDP while the FDI has only a short-run strong and positive impact on economic growth.

The error correction coefficient, which represents the speed of convergence, is negative and significant. This estimator provides an evidence of sufficient arguments for valid speed of convergence to long-run steady-state path from the poorest countries to the richest ones in CBM region during the period. Our estimation using the PMG estimator indicates an average speed of convergence of 12% over 1975–2012, which is not consistent with Barro’s (Citation1991) finding that predicts the speed of convergence at around 2% and 3% a year.

CBM countries converge to a common steady-state path growth rate regardless of their specific economic and financial policies with a speed adjustment of 12%.

5. Conclusions and policy implications

In this paper, we examined in the one hand, the different aspects of the relationship between the so-called long-term structural policies and economic growth. In the other hand, we treated the possible economic convergence of eight countries bordering the Mediterranean basin. For that, we used an ARDL method which allows us to estimate the long-term effects of different economic policies on economic growth, as advocated by endogenous growth theories.

The major results are as follows: Firstly, education and human capital improvement policy contribute directly to economic growth at both the short and long-term levels. Furthermore, the educational variable appears to be a key variable in accelerating the economic growth of our sample. At the same level, the variable of openness and economic integration is positive and statistically significant. Openness, also, seems to be a beneficial economic development strategy influencing economic growth. It is seen as a catalyst to accelerate economic growth.

Contrary to expectations, we find that the financial factors are not too significant in explaining the economic convergence of the studied countries. This result can be linked to the lack of structural reforms seeking to modernize and improve the competitiveness of the banking sector independently of the central banks influence in terms of funding. It can be also linked to the importance of the informal and shadow sector which reduces the circuit and the funding sources, especially in the southern Mediterranean countries. So, financial sector reforms should aim to abolish credit constraints and then facilitate credit availability. Interest rate liberalization is one of the measures that promote financial development by eliminating financial repression which can mobilize savings and encourage investment stimulating economic growth.

Our econometric results based on the PMG method show that despite the fact that FDI exerts a positive direct effect on per capita GDP growth in the short term, this effect disappears in the long term. This finding can be mostly explained, by the low added value nature of investments made in most of the southern Mediterranean countries of the sample. In other words, our conclusions support that these countries need FDIs with high technology instead of the traditional type of investment. Thus, as policy implications, it seems important that these countries must promote their attractiveness of investments of high quality which can bridge technological gap and also guarantee projects with important added value.

In all the specifications, the convergence parameter is negatively significant which implies the existence of an economic convergence process in our sample. Our results show that it is possible for southern Mediterranean countries to converge towards developed countries by defining an appropriate growth strategy.

Highlights

We support that even less developed bordering Mediterranean countries can converge towards the more developed;

Improving the quality of human capital through more expenditure in education, adopting a looser trade policy and encouraging FDI is a potential determinant of convergence in Mediterranean countries;

Convergence needs structural policy changes that affect educational, financial, commercial and fiscal policies in order to be able to absorb foreign investment funds and to be ongoing with the evolution of international financial and technological innovations, especially neighboring countries.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Wajdi Bardi

Wajdi Bardi is an Assistant Professor in Economics at the Higher Institute of Management of Gabes, (University of Gabes), Tunisia. He has published papers in different fields such as Economic Growth, Macroeconomics and International Finance in the Journal of Management, International Journal of Econometrics and Financial Management and International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues.

Saif Eddine Ayouni

Saif Eddine AYOUNI is an Assisitant professor in Quantitative Methods at the Faculty of Economic Sciences and Management of Sousse, (University of Sousse), Tunisia. He has published articles in different subjects such as Econometrics, Financial Development, Foreign Direct Investment and Economic Growth in the International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, the Journal of Economic and Management Perspectives, International Research Journal of Finance and Economics.

Mekki Hamdaoui

Mekki Hamdaoui is a PhD degree in Economics at the Faculty of Economic Sciences and Management of Tunis El-Manar, Tunisia. He has published articles, among others, in International review of applied economics, International economic Journal, International Economics, Journal of Multinational Financial Management. He works in several fields such as economic growth, inequality of opportunity, financial crises, exchange rate policies, and early warning systems.

Notes

1. Foreign direct investment is used as a proxy for research and development (See, Borensztein, et al. (Citation1998)).

2. Barros’s (Citation1991) study ignored the countries heterogeneity in his estimation.

3. β-convergence tends to be generated by σ-convergence.

4. According to Loayza and Ranciere (Citation2006), static panel data estimators do not take account to the long-run and short-run relationships.

5. Pesaran et al. (Citation1997) argued that the proper way to take account of the different convergence speeds across countries is to consider an unrestricted model that allows for countries differences in steady-state levels.

6. Only the PMG and MG estimators will be discussed in this paper.

7. Guidelines: H0: PMG is preferred (MG and PMG are consistent, but MG is inefficient); Ha: PMG is inconsistent. In others words, If p-value >5% we use PMG while when p-value <5% MG method is more appropriate.

8. As the variables are used in their natural logarithm, coefficients can be treated as elasticity.

References

- Abdelhafidh, S. (2013). Potential financing sources of investment and economic growth in North African countries: A causality analysis. Journal of Policy Modeling, 35, 150–20. doi:10.1016/j.jpolmod.2012.01.001

- Abu-Bader, S., & Abu-Qarn, A. M. (2008). Financial development and economic growth: Empirical evidence from MENA countries. Review of Development Economics, 12, 803–817.

- Agenor, P. R. (2000). The economics of adjustment and growth. San Diego: Academic Press.

- Aghion, P., & Howitt, P. (1998). Endogenous growth theory. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Arestis, P., & Demetriades, P. (1997). Financial development and economic growth: Assessing the evidence. The Economic Journal, 107, 783–798. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0297.1997.tb00043.x

- Aubin, C. (1994). Croissance endogène et coopération internationale. Revue d’économie politique, 104(1), 97–117.

- Balassa, B. (1985). Exports, policy choices, and economic growth in developing countries after 1973 oil shock. Journal of Development Economics, 18(2), 23–35. doi:10.1016/0304-3878(85)90004-5

- Baldacci, E., Clements, B., Gupta, S., & Cui, Q. (2008). Social spending, human capital, and growth in developing countries. World Development, 36(8), 1317–1341. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.08.003

- Barro, R. J. (1990). Government spending in a simple model of endogenous growth. Journal of Political Economy, 98(5), S103–S125. doi:10.1086/261726

- Barro, R. J. (1991). Economic growth in a cross section of countries. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(2), 407–444. doi:10.2307/2937943

- Barro, R. J., & Sala-i-Martin. (2004). Economic Growth (2nd ed.). Ney York: McGraw-Hill.

- Beck, T., Demirgus-Kuntand, A., & Levine, R. (2009). Financial institutions and markets across countries and over time –Data and analysis. Policy Research Working Paper Series, The World Bank.

- Beck, T., Levine, R., & Loayza, N., 1999.Finance and the source of growth. Policy Research Working Papers, The World Bank. 63 101–124

- Ben-David, D. (1996). Trade and Convergence among countries. The Journal of International Economics, 40, 279–298. doi:10.1016/0022-1996(95)01405-5

- Benhabib, J., & Spiegel, M. M. (1994). The role of human capital in economic development: Evidence from aggregate cross-country data. Journal of Monetary Economics, 34, 143–173. doi:10.1016/0304-3932(94)90047-7

- Benos, N., & Karagiannis, S. (2010). The role of human capital in economic growth: Evidence from Greek region. In N. Salvadori (Ed.), Institutional and social dynamics of growth and distribution (pp. 137–168). Cheltenham, UK and Northampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar.

- Berthélemy, J. C., & Varoudakis, A. (1998). Développement financier, réformes financières et croissance: Une approche en données de panel. Revue Economique, 1, 195–206.

- Bhattacharyya, S. (2009). Unbundled institutions, human capital and growth. Journal of Comparative Economics, 37(1), 106–120. doi:10.1016/j.jce.2008.08.001

- Bittencourt, M. (2012). Financial development and economic growth in Latin America: Is schumpeter right. Journal of Policy Modeling, 34, 341–355. doi:10.1016/j.jpolmod.2012.01.012

- Blackburn, K., & Hung, V. T. Y. (1993). Theory of growth, financial development and trade. Discussion Papers in Economic and Econometrics, 9303, University of Southampton.

- Borensztein, E., De Gregorio, J., & Lee, J. W. (1998). How does foreign direct investment affect economic growth? Journal of International Economics, 45(2), 115–135. doi:10.1016/S0022-1996(97)00033-0

- D’Autume, M. (1994). Education et croissance. Revue d’Economie Politique, 104(4), 457–499.

- De Gregorio, J., & Guidotti, P. (1995). Financial development and economic growth. World Development, 23, 433–448. doi:10.1016/0305-750X(94)00132-I

- De La Fuente, A., & Marin, J. M. (1995). Innovation, bank monitoring and endogenous financial development. Discussion Paper 1276.

- Demirgüc-kunt, A., & Levine, R. (1996). Stock market, development and financial intermarries: Stylized fact. World Bank Economic Review, 10(2), 291–321. doi:10.1093/wber/10.2.291

- Dollar, D. (1992). Outward oriented developing economies really do grow more rapidly: Evidence from 95 LDCs, 1976-1985. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 41, 523–544. doi:10.1086/451959

- Edwards, S. (1993). Openness, trade liberalization, and growth in developing countries. Journal of Economic Literature, 31, 1358–1393.

- Femise. (2002). The euro-mediterranean partnership. Report available on the Femise website: Euro-Mediterranean Forum of Economic Institutes.

- Frankel, J. A., & Romer, P. M. (1999). Does trade cause growth? American Economic Review, 89(3), 379–399. doi:10.1257/aer.89.3.379

- Glomme, G., & Ravikumar, B. (1997). Productive government expenditures and long-run growth. Journal of Economics Dynamics and Control, 21, 183–204. doi:10.1016/0165-1889(95)00929-9

- Gould, D. M., & Ruffin, R. J. (1995). Human capital, trade and economic growth. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 13(1), 425–445. doi:10.1007/BF02707911

- Greenaway, D., Morgan, W., & Wright, P. (2002). Trade liberalisation and growth in developing countries. Journal of Development Economics, 67, 229–244. doi:10.1016/S0304-3878(01)00185-7

- Greenwood, J., & Jouanovic, B. (1990). Financial development, growth and the distribution of income. Journal of Political Economy, 18(5), 1076–1107. doi:10.1086/261720

- Grossman, G. M., & Helpman, E. (1994). Endogenous innovation in the theory of growth. The Journal of Economic Persrectives, 8(1), 23–44. doi:10.1257/jep.8.1.23

- Harrisson, A. (1996). Openness and growth, a times-series, cross-country analysis for developing countries. Journal of Development Economic, 48(2), 419–447. doi:10.1016/0304-3878(95)00042-9

- Hausman, J. A. (1978). Specification tests in econometrics. Econometrica, 46, 1251–1271. doi:10.2307/1913827

- Helpman., C. (1995). International R&D spillovers. European Economic Review, 39, 859–887. doi:10.1016/0014-2921(94)00100-E

- Im, K. S., Pesaran, M. H., & Shin, Y. (2003). Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. Journal of Econometrics, 115, 53–74. doi:10.1016/S0304-4076(03)00092-7

- Islam, N. (1995). Growth empirics: A panel data approach. The Quaterly Journal of Economics, 110, 1127–1170. doi:10.2307/2946651

- Kim, D. H., Lin, A. C., & Suen, Y. B. (2010). Are financial development and trade openness complements or substitutes? Southern Economic Association, 76(3), 827–845. doi:10.4284/sej.2010.76.3.827

- King, R., & Levine, R. (1993a). Finance and growth: schumpeter might be right. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 434, 717–737. doi:10.2307/2118406

- King, R., & Levine, R. (1993b). Finance, entrepreneurship, and growth: Theory and evidence. Journal of Monetary Economics, 32(3), 513–542. doi:10.1016/0304-3932(93)90028-E

- Lartey, E. (2010). A note on the effect of financial development on economic growth. Applied Economic Letters, 17, 685–687. doi:10.1080/13504850802297897

- Le Pen, Y. (1997). Convergence internationale des revenues par tête: Un tour d’horizon. Revue économiePolitique, 107(10), 715–756.

- Le, T., & Tran-Nam, H. B. (2018). Trade Liberalization, Financial Modernization and Economic Development: An Empirical Study of Selected Asia-Pacific Countries. Research in Economics, 72(2), 343–355.

- Lee, K., & Kim, B. Y. (2009). Both institutions and policies matter but differently for different income groups of countries: Determinants of long-run economic growth revisited. World Development, 37(3), 533–549. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.07.004

- Levine, R., Loayza, N., & Beck, T. (2000). Financial intermediation and growth: Causality and causes. Journal of Monetary Economics, 46(1), 31–77. doi:10.1016/S0304-3932(00)00017-9

- Levine, R., & Zervos, S. (1998). Stock markets, banks and economic growth. The American Economic Review, 88(3), 537–558.

- Lhéritier, M. (2001). Les enjeux du partenariat euro-Mediterranean: Entre constraints et opportunités. In G. Benhayoun, R. Bar-El, E. Menipaz, & M. Lhéritier (Eds.), La coopération régionale dans le bassin méditerranéen (Vol. 2, pp. 15–30).

- Loayza, N., & Rancière, R. (2006). Financial development, financial fragility, and growth. Journal of Money Credit and Banking, 38, 1051–1076. doi:10.1353/mcb.2006.0060

- Lucas, R. (1988). On the mechanisms of economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics, 22(1), 3–42. doi:10.1016/0304-3932(88)90168-7

- Luintel, K. B., Khan, M., Arestis, P., & Theodoridis. (2008). Financial structure and economic growth. Journal of Development Economics, 86, 181–200.

- Mankiw, N. G., Romer, D., & Weil, D. N. (1992). A contribution to the empirics of economic growth. Quarterly Journal of Economic, 107(2). doi:10.2307/2118477

- Markusen, J., & Venables, A. (1999). Foreign direct investment as a catalyst for industrial development. European Economic Review, 43, 335–356. doi:10.1016/S0014-2921(98)00048-8

- Nelson, R. R., & Phelps, E. S. (1966). Investment in humans, technological diffusion, and economic growth. The American Economic Review, 56(1/2), 69–75.

- Pagano, M. (1993). Financial markets and growth: An overview. European Economic Review, 37, 613–622. doi:10.1016/0014-2921(93)90051-B

- Pesaran, M. H., Shin, Y., & Smith, R. P. (1997). Estimating long-run relationships in dynamic heterogeneous panels. DAE Working Papers Amalgamated Series 9721.

- Pesaran, M. H., Shin, Y., & Smith, R. P. (1999). Pooled mean group estimation of dynamic heterogeneous panels. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 94, 621–634. doi:10.1080/01621459.1999.10474156

- Pesaran, M. H., Shin, Y., & Smith, R. P. (2004). Pooled mean group estimation of dynamic heterogeneous panels. ESE Discussion Papers, 16.

- Pesaran, M. H., & Smith, R. P. (1995). Estimating long-run relationships from dynamic heterogeneous panels. Journal of Econometrics, 68, 79–113. doi:10.1016/0304-4076(94)01644-F

- Pissarides, C. A. (1997). Learning by trading and the returns to human capital in developing countries. The World Bank Economic Review, 11(1), 17–32. doi:10.1093/wber/11.1.17

- Rodrik, D. (1998). Why do more open economies have bigger governments? Journal of Political Economy, 106(5), 997–1031. doi:10.1086/250038

- Rodrik, D. (2001). L’intégration dans l’économie mondiale peut-elle se substituer à une stratégie de développement? Revue d’économie du développement, 1-2, 233–243. doi:10.3406/recod.2001.1059

- Romer, P. M. (1986). Increasing returns and long-run growth. Journal of Political Economy, 94(5), 1002–1037. doi:10.1086/261420

- Romer, P. M. (1990). Endogenous technological change. Journal of Political Economy, 98(2), 337–367. doi:10.1086/261725

- Roubini, N., & Sala-i-Martin, X. (1992). A growth model of inflation, tax evasion and financial repression. Working Paper, n° 4062, National Bureau of Economic Research

- Sachs, J. D., & Warner, A. M. (1997). Fundamental sources of long-run growth. American Economic Review, 86, 184–188. Papers and proceedings

- Sala-i-Martin, X. (1990). Lecture notes on economic growth: Five prototype models of endogenous growth. NBER working papers series, p. 49 doi:10.1099/00221287-136-2-327

- Schubert, K. (1996). Macroéconomie: Comportement et croissance (1st ed.). France: Vuibert.

- Shahbaz, M., & Rahman, M. M. (2012). The dynamic of financial development, imports, foreign direct investment and economic growth: Cointegration and causality analysis in Pakistan. Global Business Review, 13(2), 201–219. doi:10.1177/097215091201300202

- Solow, R. (1956). A contribution to the theory of economic growth. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 70, 65–94. doi:10.2307/1884513

- Suri, T., Boozer, M. A., Ranis, G., & Stewart, F. (2011). Paths to success: The relationship between human development and economic growth. World Development, 39(4), 506–522. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2010.08.020

- Tsai, C. L., Hung, M. C., & Harriott, K. (2010). Human capital composition and economic growth. Social Indicators Research, 99(1), 41–59. doi:10.1007/s11205-009-9565-z

- Wan, A. (2004). Growth and convergence in WAEMU countries. IMF Working Paper. doi:10.5089/9781451860092.001

Appendix

Table A.1. Variables definitions and descriptions