?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) is widely recognized as an engine of the structural transformation in development theories. We analyzed the effects of FDI on the structural transformation in West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU) countries by considering the industry, manufacturing, agricultural, and services sectors for the period spanning from 1990 to 2017. Using the Panel Corrected Standard Errors (PCSE) estimation technique, we showed the neutrality hypothesis of FDI inflows on industrial, manufacturing and agricultural productivity in the WAEMU region. However, findings showed positive effect of FDI inflows on services sector’s productivity. We also found that domestic credit was not an important determinant for structural transformation in WAEMU countries, except for the services sector. Moreover, findings showed that the institutional quality indicator is relatively low in WAEMU region and has negative relationship with agricultural productivity, while it increases services sector’s value added. These results imply that the low institutional quality in WAEMU may lead to the failure in the design and implementation of reliable agricultural policies of the region which may not attract the FDI, resulting in the negative effect of FDI on structural transformation in the region. Rethinking about the design and implementation of domestic development policies and promoting actions that can attract FDI in sectors with positive ripple effects, including industry, manufacturing, agriculture and services sectors are recommended for the structural transformation of the economy of WAEMU countries.

Keywords:

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Theory is clearly stated about the role of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in structural transformation of countries’ economy. Whilst FDI trend in WAEMU region is upward since 1990, the existing data show that the structural transformation of WAEMU lags behind. So far, has FDI contributed to the structural transformation of the WAEMU countries’ economy? We showed the neutrality effect of FDI inflows on industrial, manufacturing and agricultural productivity in the WAEMU region. However, findings showed a positive effect of FDI inflows on services sector’s productivity. Moreover, findings showed that the institutional quality indicator is relatively low in WAEMU region and has negative relationship with agricultural productivity, while it increases service sector’s value added. Rethinking about the design and implementation of domestic development policies and promoting actions that can attract FDI in sectors with positive ripple effects are recommended for the structural transformation of the economy of WAEMU countries.

1. Introduction

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) as a driver of economic development is part of topmost debates around the world (Mühlen & Escobar, Citation2020; Jie & Shamshedin, Citation2019; Megbowon et al., Citation2019; Sur and Nandy, Citation2018; Liu et al., Citation2017; Mainguy, Citation2004). The FDIs are therefore important in structural transformation of economies (Liu et al., Citation2017; Tiwari & Mutascu, Citation2011) and facilitates technology transfer between developed and developing countries. In the same vein, the importance of FDI in developing countries remains indisputable (Megbowon et al., Citation2019). In the context of limited domestic resources, the FDI in developing countries can be justified by their effects on economic growth, poverty, the inflow of financial resources, opening up to international markets and improving local management capacities and technology transfer (Mainguy, Citation2004; Tiwari & Mutascu, Citation2011). Moreover, FDI can finance sectors with high added value and stimulate the reallocation of resources from the least productive sectors to the most productive sectors in order to achieve effective structural transformation of economy.

However, FDI can compromise the development of host countries (Chudnovsky & Lopez, Citation1999; Sothan, Citation2017; Tomohara & Takii, Citation2011). When multinational firms produce the needs of host countries, they compete with small local businesses that tend to be closed down, and therefore weigh heavily on domestic entrepreneurship’s development. According to Sothan (Citation2017), FDI puts pressure on domestic companies if they are not based on exports. FDI can lead to an increase in labor cost in host countries (Tomohara & Takii, Citation2011) with the consequence of weakening domestic businesses. Generally, multinationals are more productive and better remunerative than domestic companies. In this logic, the employees of domestic companies put pressure on them to improve their wages by not necessarily taking into account the level of productivity. Thus, all the domestic companies which do not support the new wage levels are also thrown out of the market.

The contribution of FDI to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for all the countries of the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU) is estimated at about 1.6% from 1980 to 2017 (World Development Indicators WDI, Citation2019). The share of FDI in production for WAEMU countries was estimated on average to be about 1.05% in 1980; 3.55% in 2010 and 6.06% in 2011, respectively (WDI, Citation2019). The average FDI received by the WAEMU countries was estimated at about 561 million US dollars in 1980 and 3 billion US dollars in 2017. From 1980 to 2017, the amount of FDI in WAEMU countries reached on average about 1.24 billion US dollars (WDI, Citation2019). Over the same period, Cote d’Ivoire was the topmost country within WAEMU in terms of received amount of FDI. The average amount of FDI was about 2.86 billion US dollars for Cote d’Ivoire followed by Senegal, which recorded an average of about 2.10 billion US dollars. The FDI in Togo seems to be the lowest in the WAEMU region with an average about 386 million US dollars of FDI inflows. One should note that the WAEMU received around 4.5 billion US dollars in 1980 and more than 23 billion US dollars in 2017 (WDI, Citation2019). These statistics show the importance of FDI in structural transformation of WAEMU countries’ economy.

The structural transformation, which is defined as a reallocation of resources from the least productive sectors to the most productive sectors to speed the economic growth in long run, shows a poor performance in the WAEMU. Indeed, the contribution of agricultural sector to GDP was on average about 32.45% while industry and services sectors’ was on average about 18.92% and 44.43%, respectively, from 1980 to 2017 for the WAEMU countries (WDI, Citation2019). Over the same period, the agricultural sector has the largest share of the total workforce and represents about 58.90% of the total employment. The employment rate from industrial and services sectors was about 11.41% and 29.68%, respectively of the total employment (WDI, Citation2019). It has to be noted that the service sector has contributed more to GDP compared to other sectors. The industrial sector makes a small contribution to the production in the WAEMU, but its contribution per capita remains significant compared to other sectors of activity. Recognized as development engine (Mühlen & Escobar, Citation2020; Jie & Shamshedin, Citation2019; Megbowon et al., Citation2019; Okey, Citation2019; Nandy, 2018; Tiwari & Mutascu, Citation2011), is FDI contributing to the structural transformation of the WAEMU countries’ economy? This study attempts to answer this question which remains little discussed in the economic literature. More specifically, this article aims to analyze the contribution of FDI to the industrial productivity of the WAEMU countries. It also aims to analyze the effect of FDI on the agricultural, manufacturing and services sectors’ development.

The contribution of this article to the economic literature lies in the fact that despite studies on the effects of FDI, those that are interested in the contribution of FDI to the structural transformation of WAEMU countries are not sufficiently studied to the best of our knowledge. Few works carried out on the effects of FDI on structural transformation are those of Mühlen and Escobar (Citation2020) for the case of Mexico and Pineli et al. (Citation2019) for developing countries. By considering the developing countries in general, Pineli et al. (Citation2019) ignore the levels of development of different economic regions which can vary from one economic zone to another. In addition, these authors analyzed the effect of FDI on inter-sectoral variation without taking into account the intra-sectoral variation. This article fills this gap, by focusing on the intra-sectoral variation of each sector of activity in the WAEMU region. In addition, for several decades, the WAEMU countries with the same language have embarked on a dynamic of the economic and monetary integration. To strengthen their economic development, these countries have set up sectoral policies, such as common agricultural policy and common industrial policy as the trustworthy ways to promote the structural transformation of the region. In that way, FDI can contribute to the transformation of the WAEMU production sectors (Perkins et al. Citation2008), since agriculture, industry, manufacturing and services are among the most beneficiary sectors of FDI.

The rest of the article is structured around four sections. Section 2 presents a brief review of the literature, while the data and methodology are presented in section 3. Section 4 presents the results and discussions, whilst Section 5 concludes this article with the implications of economic policies.

2. Literature review

The theoretical and empirical frameworks as well as stylized facts of FDI and some indicators of structural transformation are presented in this section.

2.1. FDI as a driver of structural transformation: an overview of theoretical work

The literature on the effects of FDI in the development of host countries is mixed and can be gathered into two main paradigms. Unlike the first paradigm which favors the effects of FDI on economic development (Bumann et al., Citation2013; Findlay, Citation1978; Lipsey et al., Citation2013; Mainguy, Citation2004; Tiwari & Mutascu, Citation2011), the second one does not only support the conditional effect but also the negative outcome of FDI in the development of host countries (Borensztein et al., Citation1998; Sothan, Citation2017).

Thus, for the first paradigm, the new technologies introduced by FDI in developing countries can spread from the subsidiaries of multinational firms to national companies (Findlay, Citation1978) allowing host countries to increase their productivity of both capital and work (Bumann et al., Citation2013). FDI has a positive effect on the economic growth and improves population well-being with significant effects on poverty reduction (Dollar & Kraay, Citation2000; Mainguy, Citation2004; Tiwari & Mutascu, Citation2011). In the same vein, Borensztein et al. (Citation1998) argue that FDI positively affects national investment and according to De Soysa and Oneal (Citation1999), FDI encourages domestic investment.

Because of their contribution to technology and skills, which are very important in the industrialization process, FDI constitutes a vector of the industrial development which is the first step to achieve sustainable development (Jie & Shamshedin, Citation2019). Multinational corporations effectively contribute to the economic development when they promote the organization of the economic structures of countries with their comparative advantages determined by factor endowments (Pineli et al., Citation2019). Thus, through FDI, multinational firms shift activities from one sector to another in different countries (Mühlen & Escobar, Citation2020) and can stimulate the reallocation of resources towards high-productivity sectors and thereby contribute to the structural transformation. Resources may be concentrated in a non-productive sector. In this context, FDI presents itself as an effective solution for mobilizing these resources towards sectors with high added value. Since multinational firms are generally high-productivity companies, the remuneration of employees is relatively high (Bernard et al., Citation2012) leading to the reallocation of labor towards high productive sectors.

Some believe that the positive effect of FDI on the economic development of a country depends on its absorption capacity with an emphasis on financial development (Bumann et al., Citation2013; Omran & Bolbol, Citation2003), the human capital (Borensztein et al., Citation1998). In this context, Borensztein et al. (Citation1998) argue that the stock of human capital is essential for determining the magnitude of the effects of FDI on growth. For them, in countries where the level of human capital is very low, the effects of FDI are negative. According to Chudnovsky and Lopez (Citation1999), technology transfers in developing countries depend on the local absorption capacity, the adequacy of this technology to the needs of the country, and the skills of employees. Therefore, human capital finds its fundamental role in the transfer of technologies. FDI is then attracted to countries that have a high intensity of human capital (Barro, Citation1994) with the developed infrastructures. With the labor division, developing countries are tempted to be specialized in tasks with low technological capacity that do not require research and development. The innovation which is the fundamental driving force of structural transformation remains embryonic and does not favor the reallocation of the workforce towards high-productivity sectors in developing countries.

2.2. Empirical evidence for the effects of FDI on structural transformation

Empirically, Mühlen and Escobar (Citation2020) examine the effect of FDI on structural transformation in Mexico. The results revealed that FDI contributes positively to structural transformation in Mexico. This effect stems from flows of FDI channeled into the industrial sector which favors the reallocation of labor among the sectors of activity in Mexico. Pineli et al. (Citation2019) examine the role of FDI, multinational firms and structural transformation in developing countries. The results suggested the existence of a heterogeneous effect of FDI on the structural transformation of different countries. Unlike other countries, the findings from Pineli et al. (Citation2019) show a positive effect of FDI on the share of employment in modern industries in some countries. In addition, the effect of FDI on structural transformation depends on the level of development of each country and the type of FDI received. In the early stages of development, a higher concentration of FDI in the manufacturing sector reinforces the effect of FDI on structural transformation, while in the later stage, FDI is necessary for the modern non-manufacturing sector (Pineli et al., Citation2019). The financial development, corruption and trade openness (TO) are the factors that motivate the difference in the effect of FDI on the structural transformation of countries (Pineli et al., Citation2019).

Oloyede (Citation2014) examined the effect of FDI on the development of the agricultural sector in Nigeria. The results revealed that FDI contributes positively to Nigerian agricultural production. Similar results were found by Gunasekera et al. (Citation2015), Jovanović and Dašić (Citation2015) in South East Europe. However, negative effect of FDI on agriculture sector was found in the literature. For instance, Iddrisu et al. (Citation2015) examined the effect of FDI on the performance of the agricultural sector in Ghana over a period from 1980 to 2013 and came out with the evidence that FDI negatively affects the productivity of the agricultural sector in the long run, but positively at the short run. The negative effect of FDI on agricultural development was also found by Alfaro (Citation2003). However, the neutral effect of FDI was found by Awunyo-Vitor and Sackey (Citation2018) using error correction model in the case study of Ghana over the period spanning from 1975 to 2017.

Wonyra and Efogo (Citation2020) studied the relationship between FDI and trade in services in 34 countries in sub-Saharan Africa from 2005 to 2015. According to the authors, FDI positively affects exports of services when the institutional indicators are of good quality. In addition, an increase in FDI is positively correlated with imports of services in Sub-Saharan Africa. Alfaro (Citation2003) examined the effect of FDI on the development of the agricultural sector, manufacturing, and services from 1981 to 1999 worldwide. The results showed that FDI negatively affects the growth in primary sector while they positively influence the manufacturing and industry sectors. However, the effects of FDI on the development of the services sector remain ambiguous.

A comparative study of the effect of FDI on the industrial development of the Philippines, Malaysia and Thailand was carried out by Montes and Cruz (Citation2020). The results showed that FDI effectively contributes to the industrial development in Malaysia and Thailand compared to Philippines. Kalotay (Citation2010) examined the effect of FDI on structural changes in certain groups of economies in transition. The results suggest that FDI positively contributes to the structural transformation of the new member countries of the European Union while it negatively influences the structural transformation in Russia. Analyzing the contribution of FDI to industrialization in Ethiopia, Jie and Shamshedin (Citation2019) used an autoregressive model over a period from 1992 to 2017. Their results revealed that FDI positively affects industrialization in Ethiopia. Sothan (Citation2017) studied the causal link between FDI and Cambodia’s economic growth. The results show that FDI positively affected Cambodia’s economic growth from 1980 to 2014. Yu and Démurger (Citation2002) analyzed the effect of FDI on aggregate factor productivity performance of manufacturing industries in 29 Chinese provinces. The results confirmed the hypothesis of positive correlation between FDI and economic growth in the Chinese manufacturing sector.

According to Wei (Citation1996), FDI positively contributes to industrial growth through the accumulation of physical capital between 1988 and 1990. Some studies highlight the better performance of enterprises with foreign capital compared to Chinese domestic enterprises. Firms with foreign capital contribute relatively more than the overall factor productivity compared to local Chinese firms (Fan, Citation1999) since multinational firms invest in sectors with better productivity (Hanson, Citation2001). These firms also have an effect on factor productivity through their links with Chinese firms (Fan, Citation1999). Likewise, in terms of technical efficiency (Shan et al., Citation1999) or corporate profitability (Zhang & Zheng, Citation1998), foreign-invested enterprises rank better than domestic Chinese enterprises. Domestic companies can benefit from the positive spin-offs of foreign firms as shown by Marzynska (Citation2002) on Lithuania in terms of productivity due to the contacts of foreign companies with local suppliers. In the Indian automobile industry, Sur and Nandy (Citation2018) make a comparison between the technical efficiency of foreign companies compared to national companies. The results of their study reveal greater technical efficiency of foreign companies and domestic companies in India.

In contrast, Megbowon et al. (Citation2019) studied the impact of China’s FDI on the industrialization of 26 countries in sub-Saharan Africa. The results of their research reveal that Chinese FDI has a positive but not significant effect on the industrialization of sub-Saharan Africa, which means that Chinese FDI is not enough to stimulate the industrialization of the area. These results contradict the general view that an increase in FDI can be important in stimulating economic growth in developing countries. These countries must first reform their domestic financial system before opening up to FDI countries (Bumann et al., Citation2013). Innovation is only possible when a country is rich in human capital and active in research and development. Omran and Bolbol (Citation2003) show that FDI positively affects economic growth in Arabic countries when they interact with financial variables, arguing that national financial reforms should precede policies that promote FDI.

2.3. Brief overview of FDI in WAEMU and in the world

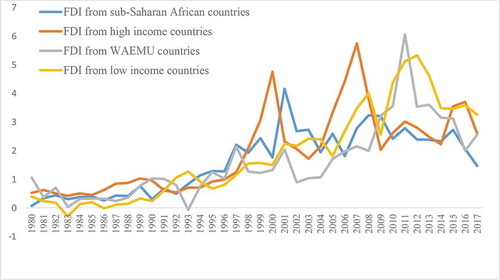

The dynamics of FDI in Sub-Saharan Africa, high-income countries, low-income countries and WAEMU countries has experienced a growing trend since the 1980s, thus demonstrating their needs in the development of nations (Figure ).

Figure 1. Dynamics of FDI (in percentage of GDP) in WAEMU and the rest of the world (1980–2017).

Figure shows that in 1980, the contribution of FDI to GDP in most countries of the world was very low before increasing over the years. The contribution of FDI to the GDP of high-income level countries reached the maximum of about 5.75% in 2007. The maximum contribution of FDI to the GDP of the low-income countries in the world was about 5.33% in 2012 before starting declining. In Sub-Saharan Africa, the contribution of FDI to economic growth reached its maximum in 2001 with about 4.15% of GDP. From 1980 to 2017, the largest share of FDI in production was recorded in 2011 where it was estimated on average about 6.06%. Figure shows that WAEMU countries recorded a large share of FDI. From 2011, the contribution of FDI to production decreased significantly in the WAEMU until 2016, before experiencing a slight increase. Indeed, this decrease can be explained by the sovereign debt crisis experienced by the euro area in the 2012 years affecting FDI flows.

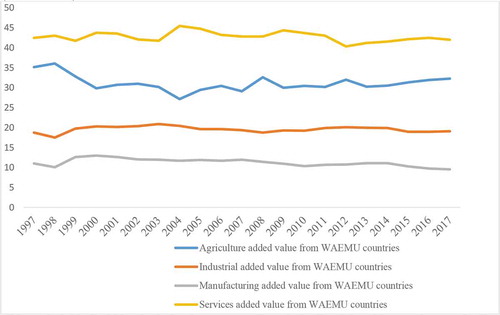

The industrial and manufacturing sectors have the lowest contribution to GDP from 1997 to 2017 compared to other sectors in the WAEMU countries (Figure ).

Figure 2. Dynamics of the major sectors of the economy (percentage of GDP) in the WAEMU (1997–2017).

The services sector contributed the most to GDP from 1997 to 2017, followed, respectively, by the agricultural sector and the industrial sector in the WAEMU. It has to be noted that the contribution of these sectors to the production of the WAEMU countries has not seen any significant variations. Between 1997 and 2017, the value added of services sector reached its maximum at 45.42% of GDP in 2004, and 36.02% for the agricultural sector in 1998. Over the same period, the industrial VA in the WAEMU reached its maximum in 2003 and estimated at 20.86% of GDP, while the contribution of manufacturing sector was on average about 12.96% of GDP. While FDI has significantly increased in the WAEMU countries compared to other regions in the world, the shares of the major sectors in production in the WAEMU countries are almost stable. These stylized facts indicate that the structural transformation of the WAEMU countries is lagging behind. In this context, FDI could then serve as a lever to initiate the structural transformation of economies and achieve sustainable development goals in the WAEMU region. This needs a sound methodological approach to assess the effect of FDI on structural transformation of the region.

3. Methodology

3.1. Econometric model and estimation technique

Structural transformation is the dependent variable that is measured by the VA of the industry, manufacturing, agriculture, and services sectors. In accordance with growth theory and recent empirical studies (Gui-Diby & Renard, Citation2015; Okey, Citation2019), we use the augmented value-added production function to investigate the effect of FDI on structural transformation. Therefore, our econometric model is specified as follows:

FDI is the variable of interest. As mentioned above, previous studies show that the effect of FDI on the level of industrialization is ambiguous (Megbowon et al., Citation2019; Okey, Citation2019). TO is measured by two indicators: exports (EXP) and imports (IMP). This variable captures the effect of globalization on industrial level. Trade and growth theories analyze the effect of international trade on growth. International trade affects growth, specifically industry growth, through diverse channels such as access to large market, technology transfer and/or reallocation of resources (Gui-Diby & Renard, Citation2015). Megbowon et al. (Citation2019) and Okey (Citation2019) have considered these variables as key factors in their studies.

Domestic investment (INV) can contribute to the structural transformation. For instance, domestic investment leads to the demand for manufactured goods and therefore to industrial development (Gui-Diby & Renard, Citation2015; Okey, Citation2019). Following Okey (Citation2019), Gui-Diby and Renard (Citation2015), we use domestic investment as a proxy of capital stock. Domestic credit (DC) to private sector represents the level of financial development. Theoretically, an increase in financial development may lead to the speed of structural transformation. Indeed, the financial development promotes savings and reallocation of capital to a critical mass of firms (Gui-Diby & Renard, Citation2015; Da Rin & Hellman, Citation2002). The financial development is used by Okey (Citation2019).

Let SL denotes sectoral employment (industry, agriculture and services). This variable is used as a proxy of labor (Mühlen & Escobar, Citation2020; Zaho & Zhang, Citation2010). Following the growth theory, labor is one of the primary factors of a production function (Romer, Citation1990). Therefore, this factor can contribute to the structural transformation. The effect of governance quality on the structural transformation is captured in the model by POL2. This variable is ranged from −10 for strongly autocracy to +10 for strongly democratic. Good institutional quality can promote the structural transformation through human and physical capital accumulation and innovation activities (Bouoiyour et al., Citation2009; Okey, Citation2019).

Finally, we introduce the binary variable (DF94) that captures the effect of devaluation policy in 1994 in WAEMU region. This variable takes 0 before 1994 and 1 after. Indeed, in the framework of monetary and exchange rate policy, the WAEMU countries that use the common currency (FCFA), have agreed to proceed for devaluation in January 1994 in order to boost the regional economy through production and exports. The theoretical literature reveals that the devaluation can lead to a more competitiveness and increase the output and aggregate demand. However, another group of works (Bahmani-Oskooee & Meteza, Citation2003; Diaz-Alejandro, Citation1963; Morley, Citation1992) asserts that the devaluation can lead to the contraction of activities and therefore decrease the output and aggregate demand. Thus, the present work extends the traditional control factors by taking into account the devaluation effect in the relationship between FDI and structural transformation.

Regarding estimation techniques, the ordinary least squares (OLS) and fixed effects (FE) or random effects (RE) are often used to study the effect of FDI on economic growth (Gunasekera et al., Citation2015; Licai et al., Citation2010; Vu et al., Citation2008). Most of time, these techniques do not deal with autocorrelation, heteroscedasticity and cross-sectional correlation problems leading to an inconsistent estimate. In this study, the Panels Corrected Standard Errors (PCSEs) method is used. Using this technique, we take into account autocorrelation, heteroscedasticity and cross-sectional correlation problems. Results from PCSEs estimation technique are compared to those from traditional estimation techniques such as OLS and FE or RE according to Hausman specification test in order to check the robustness of the results.

3.2. Data, variable definitions, and preliminary tests

The data used in this paper come from two databases. The data related to governance (polity2) are collected from the Polity IV Project, while the rest of the data are those from the World Development Indicators (WDI) database (Table ).

Table 1. Variables, definitions, and sources

We used unbalanced panel-data from eight countries of WAEMU, namely Benin, Burkina-Faso, Cote d’Ivoire, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, Niger, Senegal, and Togo. Based on the data availability, the study covers the period of 1990–2017. For example, data are not available for employment in services sector before 1990. Also, for the manufacturing value-added equation, the sample covers only six countries. The descriptive statistics of data used are presented in Table . The data show that the average net inflows of FDI were about 2.05% of GDP. However, the investment level captured by the gross fixed capital formation reached on average about 18.85% of GDP. The data also show that the industrial value added was on average about 19.11% of GDP, while the values added in agriculture and services were 32.01% and 43.01% of GDP, respectively.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics

The employment in the industry sector reached 11.41% of total employment, while the employment in agriculture and services sectors were 58.90 and 29.68, respectively. As for the manufacturing sector, the data show that the average value added from 1990 to 2017 was only about 10.45% of GDP. For the validity of the results, diverse preliminary tests were conducted. The first important is the test for unit-roots. Maddala and Wu (Citation1999) test for unit-roots is used since we are dealing with unbalanced panel data. The results are reported in Table .

Table 3. Unit roots test

The unit-root test indicates that all variables are stationary at level. This means that the cointegration tests are no longer important. The correlation between different variables and multicollinearity tests is presented in Tables – (for industry, agriculture, and services sectors).

Table 4. Correlation and multicollinearity tests (industry sector)

Table 5. Correlation and multicollinearity tests (Agriculture sector)

Table 6. Correlation and multicollinearity tests (Services sector)

For industry sector, the correlation test shows the high correlation between some independent variables (exports-imports, import-employment in Table ; exports-imports, imports-employment, domestic credit-employment in Table ; exports-imports, domestic credit-employment, exports-employment in Table ). However, the multicollinearity test shows that the means of variance inflation factor-VIF (2.06, 2.28, 2.42, and 2.61 for industrial, manufacturing, agricultural and services value added, respectively) are less than 5. This implies that all independent variables could be included in regression.

4. Results and discussion

Four dependent variables are considered to capture structural transformation: value added from industry sector, manufacturing sector, agriculture sector, and services sector. The data show the presence of autocorrelation through the Wooldridge test for the autocorrelation (AR(1)) in panel data (see Tables and ). The results from PCSEs estimation technique are robust compared to other estimation techniques (OLS, FE, and RE regressions) with exception of the sign. Indeed, the results from columns 1–2 and 4–5 from Table indicate that FDI inflows are negatively and insignificantly correlated with the level of industrialization. This can justify this difference by the incapacity of the OLS, FE or RE estimation techniques to control for the correlation among individuals.

Table 7. Regressions for industry and manufacturing sectors

Table 8. Regressions for agriculture and service sectors

Thus, the main results to be discussed are those from PCSEs presented in columns 3 and 6 of Tables and for the four sectors. We focus primarily on the link between FDI and structural transformation. Table presents the results for industry and manufacturing sectors.

The main results from Table (columns 3 and 6) indicate that the effect of FDI inflows on industrialization and manufacturing values added is positive, but not significant. These results show that FDI inflows failed to stimulate industrialization and may well reveal the absence of the reciprocal dependence of the sectors in the growth process. The lack of the interdependence between sectors in the growth process can reflect the misallocation of available resources. For instance, the agricultural sector may not provide intermediate goods for production, and the service sector fails to establish a favorable environment for manufacturing sector to prosper. Another possible explanation could be the weakness of the states to create the favorable environment to attract FDI inflows in the manufacturing sector. The evidence is that the manufacturing sector has the lowest contribution to production in WAEMU compared to other sectors (about 10.45% of GDP during 1990–2017). Similar results were found by Megbowon et al. (Citation2019) and Okey (Citation2019) who pinpoint that FDI does not contribute to industrialization development in developing countries.

Focusing on the effect of FDI inflows on agricultural and services values added, results are reported in Table . The main results indicate that FDI inflows are negatively correlated with agricultural development, but not significant (column 3), while FDI inflows increase significantly services sector’s value addition (column 6). Indeed, the agricultural sector in West African countries including those from WAEMU is highly risky because of pronounced effects of climate change with no formal insurance scheme coping with these risks in case of bad harvest (Ali et al., Citation2020). In this context, it will be difficult to attract FDI in agriculture sector leading to the transfer of capital stock in other sectors such as services. This has been found by Ben Slimane et al. (Citation2016) in the case of 55 developing countries. Another possible reason is that FDI inflows could create jobs in urban zones with higher wages and stimulate workers incentive in rural zones to migrate.

Investigating the link between FDI and services sector value addition, diverse effects have been found with different estimation techniques, but only results from column 6 (Table ) are considered for discussion. These results are robust to various estimation techniques with the exception of those of OLS and FE regressions from Table (columns 4–5) for the services sector.

Indeed, the results from columns 4–5 from Table indicate that an increase in FDI has no effect on services sector. As indicated above, this difference is due to the weakness of the OLS and RE estimation techniques to control for the correlation between individuals. From the PCSEs estimation technique, we found the positive and significant correlation between FDI and services sector production at 1% level. This implies that the FDI inflows are the main determinant of the production from the services sector in WAEMU countries. Similar results were found by Doytch and Uctum (Citation2019) who pinpoint that FDI inflows raise significantly services value addition in the case study of Asia-Pacific. In summary, the effect of FDI on industrialization, manufacturing, and agricultural values added is neutral, while FDI inflows are significantly and positively correlated with the services sector production. These results indicate that FDI inflows failed to stimulate structural economic transformation and may well reveal the absence of the reciprocal dependence of the sectors in the growth process.

About the control variables, we found that domestic investment increases significantly the industrial sector productivity (Table , column 3) and agriculture development (Table , column 3). However, an increase in domestic investment has no effect on manufacturing (Table , column 6) and services sector productivity (Table , column 6). As indicated by Gui-Diby and Renard (Citation2015) in the case study of African countries, these results can be explained by the natural resource endowment and its economic consequences. Indeed, a boom in a specific non-manufacturing sector such as natural resource sector can lead to de-industrialization by attracting more resources and investments than other sectors. These results are in line with Gui-Diby and Renard (Citation2015) and Megbowon et al. (Citation2019).

The results show an ambiguous effect of TO on structural transformation. Globally, exports have no effect on agriculture and services sectors (Table ). However, increasing exports will increase significantly the industry and manufacturing outputs (Table ). The effect of imports on structural transformation varies from one sector to another. Imports reduce significantly industrial and manufacturing value added (Table ) while imports rise significantly agriculture value added (Table ). However, imports have no effect on services value added (Table , column 6). Indeed, WAEMU countries are net importers of agricultural inputs such as mechanization tools, tractors, fertilizer and seeds for agricultural production while exporting more industrial goods in terms of raw materials (Coffee, cocoa, cotton, and cashew nut). In this context, imports can increase agricultural productivity. The negative effect of imports on industrialization can be explained by the importation of the final good products rather than input goods (industrial machines and equipment), which are essential to promote the development of industrial and manufacturing sectors. These results confirm those obtained by Megbowon et al. (Citation2019) and Okey (Citation2019).

The main results indicate that domestic credit, mostly provided to private sector by banks, is not an important determinant for structural transformation, except for the services sector. Indeed, domestic credit reduces significantly the services sector productivity, but has no effect on the manufacturing sector when we employ other estimation techniques. Based on the main results (columns 3 and 6 from Table ), the labor has no effect on manufacturing sector while increasing significantly industrial value added. This means that employment is directed towards the non-manufacturing sector. In the same line, results from Table show that employment increases significantly agricultural and services sector productivity as found by Ben Slimane et al. (Citation2016) and Zaho and Zhang (Citation2010).

Table shows that governance (politiy2) has no effect on industry, and manufacturing sector. However, governance reduces agricultural value added while increasing services value added (Table ). These results imply that the low institutional quality in the WAEMU countries does not favor the implementation of good agricultural policies that need to involve all stakeholders in the process. This can result in a significant reduction in agricultural value added. Also, the common agricultural policy may lead to this result if not well designed and implemented. Moreover, agricultural policies implemented in WAEMU region may not attract the FDI resulting to the negative effect of FDI on structural transformation in the region. Finally, the main results show that the devaluation policy implemented in WAEMU countries in order to boost productivity had no effects on structural transformation of the region. Bahmani-Oskooee (Citation1998) found that devaluation has no effect on aggregate growth. This result is robust to other estimation techniques, except in manufacturing sector, where devaluation affects positively and significantly manufacturing value added.

5. Conclusion

The paper analyzes the effect of foreign direct investment on structural transformation in West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU) over the period spanning from 1980 to 2017. Industrial value added, manufacturing value added, agricultural value added, and services value added are used as proxies of structural transformation. Domestic investment, exports, imports, sectoral employment, polity2, and a binary variable for devaluation of CFA franc in 1994 are used as control variables. Using the PCSEs as the main estimation technique, the results show that foreign direct investment does not contribute significantly to the development of industrial, manufacturing, and agriculture sectors in WAEMU countries. This result seems to be robust to other estimation techniques (OLS, FE versus RE estimations). However, the findings indicate that FDI inflows contribute significantly and positively to the development of services sector. In addition, the effect of other control variables varies from one equation to another.

These results indicate that WAEMU countries failed to create a favorable environment for FDI to start structural transformation. This highlights the ambiguous results of previous works about effects of FDI inflows on total growth. The situation is due to the lack or a weak synergy between different sectors of economy. These results suggest the rethinking about the design of domestic policies that intend to promote the attractiveness of FDI inflows and implement reliable and sound structural transformation policies in WAEMU countries. These policies have to be rationalized in the same framework in order to establish the coherency between structural transformation and FDI for sustainable growth. Also, growth-enhancing decisions should be based on the sectorial analysis. Indeed, decision-makers in WAEMU region should promote the efficient reallocation of resources by creating the interdependence across sectors and attract FDI inflows in sectors with positive ripple effects.

Disclosure statement

The authors do not have any conflict of interest to report.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Essotanam Mamba

Essotanam Mamba is a PhD Candidate in Economic Department (University of Lomé, Togo). He has his master's in Applied Economics at University of Abomey Calavi (Benin) through the grant of Interuniversity Postgraduate Program in Economics (PTCI). His research interests include international economics and economic growth.

Moukpè Gniniguè

Moukpè Gniniguè is a PhD Candidate in Economics and a research assistant at the Faculty of Economics and Management Sciences at the University of Kara (Togo). He did his master's in Applied Economics at the University of Abomey-Calavi (Benin) as part of the Interuniversity Postgraduate Program in Economics (PTCI). His research interests include migration, structural transformation and economic growth.

Essossinam Ali

Essossinam Ali is a Senior lecturer at Department of Economics, University of Kara. He has his PhD in Applied Agricultural Economics and Policy (University of Ghana). His research interests include structural transformation, Economic Policy, climatic change, food security, economic impact valuation, agricultural finance, and environmental issues.

References

- Alfaro, L. (2003). Foreign direct investment and growth: Does the sector matter. Harvard Business School, 2003, 1–21. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228966060

- Ali, E., Egbendewe, Y. G. A., Abdoulaye, T., & Sarpong, D. B. (2020). Willingness to pay for weather index-based insurance in semi-subsistence agriculture: Evidence from northern Togo. Climate Policy, 20(5), 534–547. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2020.1745742

- Awunyo-Vitor, D., & Sackey, R. A. (2018). Agricultural sector foreign direct investment and economic growth in Ghana. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 7(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-018-0094-3

- Bahmani-Oskooee, M. (1998). Are devaluations contractionary in LDCs? Journal of Economic Development, 23(1), 131–144.

- Bahmani-Oskooee, M., & Meteza, I. (2003). Are devaluation expansionary or contractionary? A survey article. Economic Issues, 8(2), 1–28.

- Barro, R. J. (1994). Sources of economic growth. In Carnegie-Rochester conference series on public policy, (vol. 40, pp 1–46). North-Holland.

- Ben Slimane, M., Huchet-Bourdon, M., & Zitouna, A. (2016). The role of sectoral FDI in promoting agricultural production and improving food security. International Economics, 145, 50–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inteco.2015.06.001

- Bernard, A. B., Jensen, J. B., Redding, S. J., & Schott, P. K. (2012). The empirics of firm heterogeneity and international trade. Annuual Review of Economics, 4(1), 283–313. https://doi.org/org/full/10.1146/annurev-economics-080511-110928

- Borensztein, E., De Gregorio, J., & Lee, J. W. (1998). How does foreign direct investment affect economic growth? Journal of International Economics, 45(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1996(97)00033-0

- Bouoiyour, J., Hanchane, H., & Mouhoud, M. (2009). Investissement direct étrangers et productivité: Quelles interactions dans le cas des pays du moyen orient et en Afrique du Nord. Revue Economique, 9(1), 109–131. https://doi.org/10.3917/reco.601.0109

- Bumann, S., Hermes, N., & Lensink, R. (2013). Financial liberalization and economic growth: A meta-analysis. Journal of International Money and Finance, 33(3), 255–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jimonfin.2012.11.013

- Chudnovsky, D., & Lopez, A. (1999). Globalization and developing countries: Foreign direct investment and growth and sustainable human development. Geneva, United Nation. http://old.tci-network.org/media/asset_publics/resources/000/000/788/original/globalization-chudnovsky.pdf

- da Rin, M., & Hellman, T. (2002). Banks as catalysts for industrialization. Journal of Financial Intermedaition, 11(4), 366–397. https://doi.org/10.1006/jfin.2002.0346

- de Soysa, I., & Oneal, J. R. (1999). Boon or bane? Reassessing the productivity of foreign direct investment. American Sociological Review, 64(5), 766–782. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657375

- Diaz-Alejandro, C. F. (1963). A note on the impact of devaluation and the redistributive effects. Journal of Political Economy, 71(6), 577–580. https://doi.org/10.1086/258816

- Dollar, D., & Kraay, A. (2000). Growth is good for the poor. World bank. Development Research Group.

- Doytch, N., & Uctum, M. (2019). Spillovers from Foreign direct investment in services: Evidence at sub-sectoral level for the Asia-Pacific. Journal of Asian Economics, 60(3), 33–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asieco.2018.10.003

- Fan, X. (1999). Technological spillovers from foreign direst investment and industrial growth in China. [Doctoral Thesis]. Australian National University.

- Findlay, R. (1978). Relative backwardness, direct foreign investment and the transfer of technology: A simple dynamic model. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 92(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.2307/1885996

- Gui-Diby, S. L., & Renard, M. F. (2015). Foreign direct investment inflows and industrialization of African countries. World Development, 74, 43–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.04.005

- Gunasekera, D., Cai, Y., & Newth, D. (2015). Effects of foreign direct investment in African agriculture. China Agricultural Economic Review, 7((2):), 167–184. https://doi.org/10.1108/CAER-08-2014-0080

- Hanson, G. H. (2001). Should countries promote foreign direct investment? United Nation conference on trade and development (G-24 Discussion Paper Series, N°9).

- Iddrisu, A. A., Immurana, M., & Halidu, B. O. (2015). The impact of foreign direct investment (FDI) on the performance of the agricultural sector in Ghana. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 5(7), 240–259. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v5-i7/1734

- Jie, L., & Shamshedin, A. (2019). The impact of FDI on industrialization in Ethiopia. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 9(7), 726–742. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v9-i7/6175

- Jovanović, S. S., & Dašić, B. (2015). The importance of foreign direct investment for south east european countries’agriculture. Economics of Agriculture, 62(3), 661–675. doi:10.5937/ekoPolj1503661S

- Kalotay, K. (2010). Patterns of inward FDI in economies in transition. Eastern Journal of European Studies, 1(2), 55–76.

- Licai, L., Wen, S., & Xiong, Q. (2010). Determinants and performance index of foreign direct investment in China’s agriculture. China Agricultural Economic Review, 2(1), 36–48. https://doi.org/10.1108/17561371011017487

- Lipsey, R. E., Sjöholm, F., & Sun, J. (2013). Foreign ownership and employment growth in a developing countries. Journal of Development Studies, 49(8), 1133–1147. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2013.794264

- Liu, Y., Hao, Y., & Gao, Y. (2017). The environmental consequences of domestic and foreign investment: Evidence from China. Energy Policy, 108(32), 271–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2017.05.055

- Maddala, G. S., & Wu, S. (1999). A comparative study of unit root tests with panel data and a new simple test. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and statistics, 61(1), 631-652.

- Mainguy, C. (2004). L’impact des investissements directs étrangers sur les économies en développement. Région et Développement, 20, 65–89.

- Marzynska, B. K. (2002). Does foreign investment increase the productivity of domestic firms. Search of Spillovers through Backward Linkages (World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, 2923).

- Megbowon, E., Mlambo, C., & Adekunle, B. (2019). Impact of china’s outward FDI on sub-saharan africa’s industrialization: Evidence from 26 countries. Cogent Economics & Finance, 7(1), 1681054. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2019.1681054

- Montes, M. F., & Cruz, J. (2020). The political economy of foreign investment and industrial development: The Philippines, Malaysia and Thailand in comparative perspective. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 25(1), 16–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/13547860.2019.1577207

- Morley, S. A. (1992). On the effect of devaluation during stabilization programs in LDCs. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 74(1), 21–27. https://doi.org/10.2307/2109538

- Mühlen, H., & Escobar, O. (2020). The role of FDI in structural change: Evidence from Mexico. The World Economy, 43(3), 557–585. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.12879

- Okey, M. K. (2019). Does international migration promote industrial development? Evidence from Africa 1980–2010. International Economic Journal, 33(2), 310–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/10168737.2019.1585902

- Oloyede, B. B. (2014). Impact of foreign direct investment on agricultural sector development in Nigeria, (1981-2012). Kuwait Chapter of the Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review, 3(12), 14. https://doi.org/10.12816/0018804

- Omran, M., & Bolbol, A. (2003). Foreign direct investment, financial development, and economic growth: Evidence from the Arab countries. Review of Middle East Economics and Finance, 3(1), 231–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475368032000158232

- Perkins, D. H., Radelet, S., Lindauer, D. L. (2008). Économie du développement, 3ème Edition, Collection Ouvertures Economiques, Bruxelles, Editions De Boeck Université.

- Pineli, A., Narula, R., & Belderbos, R. (2019). FDI, multinationals and structural change in developing countries (No. 004). United Nations University-Maastricht Economic and Social Research Institute on Innovation and Technology (MERIT).

- Romer, P. M. (1990). Human capital and growth: Theory and evidence. Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy, 32, 251–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-2231(90)90028-J

- Shan, J., Tian, G., & Sun, F. (1999). Causality between FDI and economic growth. In W. Yanrui (Ed.), Foreign direct investment and economic growth in China, (pp. 140–154). Cheltenham-Northhampton.

- Sothan, S. (2017). Causality between foreign direct investment and economic growth for Cambodia. Cogent Economics & Finance, 5(1), 1277860. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2016.1277860

- Sur, A. &., & Nandy, A. (2018). FDI, technical efficiency and spillovers: Evidence from Indian automobile industry. Cogent Economics & Finance, 6(1), 1460026. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2018.1460026

- Tiwari, A. K., & Mutascu, M. (2011). Economic growth and FDI in Asia: A panel data approach. Economic Analysis and Policy, 41(2), 173–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0313-5926(11)50018-9

- Tomohara, A., & Takii, S. (2011). Does globalization benefit developing countries? Effects of FDI on local wages. Journal of Policy Modeling, 33(3), 511–521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpolmod.2010.12.010

- Vu, T. B., Gangnes, B., & Noy, I. (2008). Is foreign direct investment good for growth? Evidence from sectoral analysis of China and Vietnam. Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 13(4), 542–562. https://doi.org/10.1080/13547860802364976

- WDI. (2019). World development indicators. World Bank.

- Wei, S. (1996). Foreign direct investment in China: Sources and consequences. In Ito, T., & Krueger A. (Eds.) Financial Deregulation and Integration in East Asia, NBER-EASE (Vol. 5, pp.77–105). University of Chicago Press. https://www.nber.org/chapters/c8559.pdf.

- Wonyra, K. O., & Efogo, F. O. (2020). Investissements directs étrangers et commerce des services en Afrique subsaharienne. Mondes en développement, 1(189), 125-141. https://doi.org/10.3917/med.189.0125

- Yu, C., & Démurger, S. (2002). Croissance de la productivité dans l’industrie manufacturière chinoise: Le rôle de l’investissement direct étranger. Economie Internationale, 4(92), 131–163. https://www.cairn.info/revue-economie-internationale-2002-4-page-131.htm

- Zaho, Z., & Zhang, K. H. (2010). FDI and industrial productivity in China: Evidence from panel data in 2001-06. Review of Development Economics, 14(3), 656–665. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9361.2010.00580.x

- Zhang, F., & Zheng, J. (1998, August). The impact of multinational enterprises on economic structure and efficiency in China. China Center for Economic Research, Beijing University.