?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Despite that reviews have been done in intellectual capital and the performance of firms, their status has remained uncertain in the emerging economy. Previous studies have generally focused on single industries and have overlooked the input of the service and manufacturing sectors as a whole. This study offers new insight into the area of intellectual capital and its relationship with firms’ performance in Tanzania and evaluates intellectual capital within the service and manufacturing sectors in totality. Using panel regression analysis for the periods of 2010 to 2019, the performance was measured in terms of SG, ROA, ATO, and Tobin’s. Heteroscedasticity and endogeneity were controlled using clustered robust standard errors. The empirical findings demonstrate a significant positive influence between structural capital efficiency and SG, ROA, ATO, and Tobin’s. However, the effect of human capital efficiency and capital employed efficiency were negative which suggests poor investment in human skills and capital of the firms. Further, VAIC was significantly positively associated with SG, ATO, ROA, and Tobin’s Q. It is recommended that to have a competitive advantage, managers and policymakers should focus on the three parts of intellectual capital which are the key drivers of value creation in the organization.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Intellectual capital was acknowledged as one of the main factors of firm financial performance after the world has shown an apparent concern with the knowledge economy. It is an important component that contributes to the value creation of firms. It was recognized that the financial performance of firms depends not only on tangible assets but also on intangible assets. Studies on intellectual capital in less developed nations are topical and there is a general call for further studies in an emerging economy. Therefore, the present study analyzed intellectual capital and financial performance of service and manufacturing firms in Tanzania using the Value Added Intellectual Coefficient (VAIC) Model over the periods from 2010 to 2019.

1. Introduction

Debate on the intellectual capital (henceforth IC) and the financial performance have recently become an issue of interest (Vătămănescu et al., Citation2019; Xu & Wang, Citation2019). Intellectual capital is realized as ownership of knowledge, applied experience, organization innovation, client relationship, and professional skills which make esteem and give value creation to the organization (Vătămănescu et al., Citation2019; Xu & Wang, Citation2019). The debate on IC is furthered by the growing desire by firms to increase investments not only in tangible assets but also in intangible assets (Oppong & Pattanayak, Citation2019; Tran & Hong, Citation2020). Intangible assets are realized as, but not limited to, investments in copyrights, patents and goodwill, investments in the knowledge of staff, and relationships with key stakeholders (Asare et al., Citation2017; Forte et al., Citation2019).

There are three key areas that form IC: human capital, structural capital, and relational capital (Amin et al., Citation2018). According to Poh et al. (Citation2018), human capital is the organization’s knowledge at an individual dimension comprising of education, professionalism, and commitment. All these are important to enhance business activities and create value. Structural capital is the knowledge made by human capital that incorporates innovations, information, productions, techniques, strategies, methodology, policies, management systems, technology, economic, tax, credit, etc. (Forte et al., Citation2019). And relational capital is referred to as knowledge related to the association of an organization with its stakeholders, in the framework of coordinated efforts and common trust (Jummaini & Hasan, Citation2019).

The advantages of IC are illustrated by the transformations from the industrial economy to the knowledge economy in the first world countries (Forte et al., Citation2019). Indeed, less developed countries, like Tanzania, need to draw and expand this knowledge to transform their economies. A short description of Tanzania will serve to illustrate this need. In Tanzania, the economy has advanced through different stages since independence in 1961. Measures were taken by the Government to change the economy and encourage both domestic and foreign investors (Wangwe et al., Citation2016). Despite these endeavors, fragility and inefficiency are notably the long-characteristics of Tanzania’s manufacturing firms (Wangwe, Citation2018). As of now, the prioritized development agenda is industrialization, intending to lead the country to a semi-industrialized nation by 2025 (Wangwe, Citation2018). Therefore, the firms require extremely specialized knowledge and skills as emphasized by Smriti and Das (Citation2018). Besides, the country has embarked on various reforms in order to transform and bring the economy to the global stage through deregulation, privatization and Public Private Participation scheme among others. Due to series of economies reformed embarking upon, there is evident dynamism in the Tanzanian economy through shifting from its traditional product-based economy to a knowledge-based orientation and diversification approach which signifies the significance of IC in the country. Along these lines, investing in human capital will make workers innovative and increasingly productive which, in turn, would create value, competitiveness, and subsequently development (Wangwe et al., Citation2016). Nevertheless, it has been awaiting uncertainty on whether Tanzania can sustain these difficulties as it keeps on concentrating on natural-based activities instead of higher value-added activities (URT, Citation2018). As indicated by Wangwe et al. (Citation2016), intellectual resources are fundamental factors for the development and investing in them makes employees innovative and more efficient in their obligations, thus creates value and henceforth development.

Industries require extremely specialized knowledge and skills and are subject to organizational implicit knowledge and capabilities (Sharabati et al., Citation2020). The endurance of these industries requires significant volumes of human resources and physical capital. Moreover, although reviewed literature contains massive studies on the relationship between intellectual capital and financial performance of firms, little has been done, especially in the manufacturing and service sectors which are key sectors to the economic growth of the nation (Smriti & Das, Citation2018). In addition, regardless of the long periods of structural adjustment and liberalization of the economy, Tanzania has yet to develop a significant level of export-oriented manufacturing (Keregero, Citation2016). Considerably, most of the existing studies on the influence of intellectual capital on the performance of manufacturing or service sectors are selective to the developed countries and they present mixed results (Kanchana & Mohan, Citation2017). There are very few studies in the context of emerging economies, such as Tanzania. While there is limited literature on the subject of IC in Tanzania, implications of IC for specific industries, are emphasized (Chowdhury et al., Citation2018; Xu & Wang, Citation2018). The existing findings in diverse settings may be difficult to generalize. Besides, differences in economic conditions and institutional impacts, for example, variations in capital markets and regulatory systems, cause variations (Kanchana & Mohan, Citation2017; Poh et al., Citation2018). Research on IC will expand understanding on the level of investment in intangible assets. This will, in turn, assist firms to become productive, viable, profit-making, and innovative. Further, it will encourage managers and producers to comprehend the significance of IC and invest on the knowledge economy for better performance of firms. The findings of this study will also help policymakers and other stakeholders to properly reallocate intellectual resources.

This study offers new insight into the area of IC and its relation to firms’ performance in Tanzania. It is contrasted from other studies in that it uses panel regression analysis to evaluate IC and establish its relationship with the traditional measures within the service and manufacturing sectors in totality. Although Smriti and Das (Citation2018) had evaluated IC and firms’ performance in manufacturing and service firms in India, their study used the system generalized method of moments (SGMM). In Tanzania, studies have been selective to either banking or manufacturing sectors (for example, see Isanzu, Citation2015). Therefore, it is important to measure the relationship between intellectual capital (human capital, structural capital & capital employed efficiency) and financial performance of service and manufacturing firms in Tanzania.

2. Literature review and hypotheses

This section presents the literature review related to intellectual capital efficiency and financial performance in Africa and less developed nations, theoretical review, and development of hypotheses.

2.1. Literature review

2.1.1. Intellectual capital efficiency and financial performance

The multiplication of research in the area of IC leads to the evident request of the degree to which IC performance influences the performance of service and manufacturing firms (Oppong & Pattanayak, Citation2019; Vătămănescu et al., Citation2019). Actually, there is a lot of debate of IC within the literature on issues related to the management of intangible assets (Tran & Hong, Citation2020; Xu & Wang, Citation2019). The literature review on the intellectual capital and financial performance especially in Africa and less developed countries are summarized in Table .

Table 1. Summary of Literature Review on Intellectual Capital and Financial Performance

Generally, studies on IC in the service and manufacturing sectors are many but limited in the specific case of the service or manufacturing. Thus, there is still a need for more work to be conducted in emerging economies.

2.1.2. Theoretical review: Resource-based theory

The Knowledge-based perspective on the firm is an ongoing expansion of the Resource-based perspective on the firm which is extremely sufficient to the present economic setting (Hoskisson et al., Citation1999). Knowledge is viewed as an exceptionally uncommon key asset that doesn’t deteriorate in the manner conventional economic productive factors do and can produce increasing returns (Roos et al., Citation1997). The idea of most Knowledge-based assets is intangible and dynamic (Sveiby, Citation2001).

Knowledge assets are especially essential to guarantee that competitive advantages are sustainable, as these assets are hard to imitate (Wiklund & Shepherd, Citation2003). The Knowledge resources of the firm have attracted incredible enthusiasm as it mirrors that the scholarly world recognizes the fundamental economic changes resulting from cumulatively and accessibility of knowledge in the previous two decades (Rouse & Daellenbach, Citation2002). We are seeing a basic change in the beneficial worldview (Carneiro, Citation2003). The change from manufacture to services in most of the developed economies depends on the manipulation of information and images and not on the utilization of physical items (Fulk & DeSanctis, Citation1995).

The establishments of the resource-based view (RBV) of the firm can be found in the work by Penrose (Citation1959) that imagined the firm as a managerial association and an assortment of beneficial assets, both physical and human. Material assets, just as human resources, can give the firm an assortment of services. Similar assets can be put to use in various ways, as indicated by the thoughts of the organizations on the most proficient method to apply them. In this sense, there is a close connection between the knowledge that individuals in the association confine and the services got from the assets. The RBV of the firm spotlights uniquely within the firm, its assets, and abilities, to clarify the benefit and estimation of the organization (Makhija, Citation2003).

The RBV of the firm expresses that distinctions in performance happen when well-succeeded organizations have important assets that others don’t have, enabling them to get a lease in its semi monopolist structure (Wernerfelt, Citation1984). The presence of abilities and assets heterogeneity inside a populace of firms is one of the standards of the RBV (Helfat & Peteraf, Citation2003). According to RBV the procedure of asset aggregation is viewed as an impression of creative and entrepreneur activities. Benefits can rise out of these exercises if asset aggregation costs are below compared to the rents that those assets may create (Peteraf, Citation1993).

As per Barney (Citation2001b) firm assets can be ordered into three classifications: physical capital assets, human capital assets, and organizational capital assets. According to Barney (Citation2001b), there are conditions that assets must present to empower the firm to support its competitive advantage: value, rareness, flawed imitability, and non-substitutability. These conditions are as yet regarded in ongoing literature (Wiklund & Shepherd, Citation2003). The competitive advantage from the accumulation and usage of assets inside the firm, as such, it is the consequence of how the firm uses what it has (Roos et al., Citation1997).

Therefore, the organizations need to become a knowledge-based organization. However, few comprehend what that implies, and how to roll out the improvements to accomplish it. Maybe the most widely recognized error firms do is thinking about that the higher the knowledge substance of their products and services, the closest they are to be genuine knowledge-based organizations. In any case, the products and services are just the visible and tangible reality they present to their customers—a hint of something larger. As in genuine ice sheets, the biggest reality that enables the firm to deliver is situated underneath the outside of the water, covered up in the intangible resources of the organization, and it involves the knowledge on what the firm does, how it is done, and why it is done that way (Zack, Citation2003).

The sustainability of the knowledge-based competitive advantage depends on accompanying affiliation: knowing preferred certain angles over the competitors (Zack, Citation2003). However, certain nations very rich in natural resources are still falling in the commodity trap, implying that they belief that their mines, instead of their brains, are the wellspring of their flourishing. Countries’ genuine riches don’t reside in forests of elastic trees or acres of diamond mines, but in the strategies and technologies for exploiting them (Stewart, Citation1998). The issue is that it is considerably harder to count thoughts and specialization than to count the cash, or amounts of products (Reinhardt et al., Citation2003).

2.2. Hypotheses development

The hypotheses of the study are as follows:

2.2.1. Intellectual capital performance

Intellectual capital is intangible and non-monetary and adds immensely to value creation (Vishnu & Gupta, Citation2014). It enhances firm performance irrespective of geographic location and firm size (Nadeem et al., Citation2017). While Value Added Intellectual Coefficients (VAIC) is an indicator of performance and is directly proportional to the efficiency of the company (Chen et al., Citation2005). As clarified before, despite of different investigations which that been done regarding the intellectual capital and performance of firms, the diverse settings may be difficult to generalize. An investigation by Chan (Citation2009b) analyzed the effect of intellectual capital on the organizational performance of companies in the Hang Seng Index. The outcomes revealed an insignificant association between intellectual capital and the firm’s performance. Similarly, Vishnu and Gupta (Citation2014) evaluated the relationship between Intellectual capital and the performance of pharmaceutical firms in India. They discovered that there is a significant positive connection between intellectual capital and financial performance of firms. However, Oppong and Pattanayak (Citation2019) examine whether investing in intellectual capital can improve productivity from Commercial Banks in India. Using a panel of 73 commercial banks in India for 12 years (2006–2017), the study found out that some components of intellectual capital improve productivity, and others do not.

On the other hand, Chowdhury et al. (Citation2018) examine the impact of intellectual capital on financial performance from Bangladeshi Textile Sector. Their findings indicated that the value-added intellectual coefficient fundamentally impacted productivity, with tangible capital assuming a noteworthy in both productivity and profitability. Also, it was discovered that structural capital considerably effected return on equity, asset turnover, and return on assets with human capital showing the unimportant effect on all indicators of financial performance. As per Farrukh and Joiya (Citation2018), researching the effect of intellectual capital on the overall financial performance and financial efficiency of manufacturing firms in Pakistan uncovered that association between the different parts of Intellectual Capital and the firm performance was significant. Similarly, Ekwe (Citation2012) led an examination on the Intellectual Capital and Financial Performance of Nigerian Banks. The outcomes demonstrate that structural capital isn’t related to bank performance, while human capital efficiency and capital employed efficiency have a positive connection with Nigerian banks’ performance.

In Tanzania, Isanzu (Citation2015) directed an examination to examine the connection between intellectual capital (IC) and the financial performance of banks. The investigation utilized Value Added of Intellectual Coefficient technique to determine the intellectual capital efficiency of the banks. The study found all parts of intellectual capital are positively connected with banks’ financial performance. Similarly, Nadeem et al. (Citation2017) supported this positive relation in BRICS listed firms using ROA, ATO, ROE, and market value as firm performance indicators. Likewise, this study expects a positive significant impact of VAIC on Tanzanian manufacturing service and firms using profitability (ROA), productivity (ATO), and Sales Growth (SG) and market value (Tobin’s Q). Therefore, the study proposes:

H1a: IC performance positively affects firm profitability.

H1b: IC performance positively affects firm productivity.

H1c: IC performance positively affects firm market value.

H1d: IC performance positively affects firm sales growth

2.2.2. Human capital

Similarly, Pulic (Citation1998, Citation2000) came with a model known as value-added intellectual coefficients, which measures a firm’s intellectual efficiency in the knowledge economy. According to Pulic (Citation2000), the model is related to the physical/financial, structural, and human capital, which creates value for firms. Human capital efficiency (HCE) as a component of the VAIC model constitutes the knowledge of employees and their competence (Bontis, Citation1998) which does not remain at the organization after the employee leaves. Nimtrakoon (Citation2015) found similar results, consistent with those of Wangwe et al. (Citation2016), that HCE significantly affects firm performance. Also, studies in an emerging market by Tran and Hong (Citation2020) documented similar results, indicating that HCE affects firm performance. Chen et al. (Citation2005) reported a highly significant correlation between HC and SG, ROA, ATO, and market value of Taiwanese firms. Oppong and Pattanayak (Citation2019), found that HCE has a positive effect on firms’ performance. Based on these findings, the study forms the following hypothesis:

H2a: HCE positively affects firm profitability

H2b: HCE positively affects firm productivity.

H2c: HCE positively affects firm market value.

H2d: HCE positively affects firm sales growth.

2.2.3. Capital employed efficiency

According to Pulic (Citation1998), capital employed efficiency (CEE) refers to all necessary financial funds and physical capital, which is an important element in the VAIC model. Researchers such as Chen et al. (Citation2005) found CEE to be positive and significant with ROA. A study on Turkish banks by Ozkan et al. (Citation2017) found a positive association between CEE on bank performance. Nadeem et al. (Citation2017) supported this positive and significant correlation between physical, financial capital and profitability, productivity, and market valuation of the firm. Similarly, Oppong and Pattanayak (Citation2019) found similar results, consistent with those of Smriti and Das (Citation2018) that HCE has a positive effect on firms’ performance. Based on these findings, the study expects:

H3a: CEE positively affects firm profitability.

H3b: CEE positively affects firm productivity.

H3c: CEE positively affects firm market value.

H3d: CEE positively affects firm sales growth.

2.2.4. Structural capital employed

Concerning structural capital (SC), which compose of firm’s strategies, databases, management processes, organizational plans and corporate approaches (Szulanski, Citation2002) and help in supporting their employee’s performance and business performance (Bollen et al., Citation2005). Examining the association between SCE and firm performance, the findings of Bontis et al. (Citation2015), found that SCE has a significant relationship with performance. Similarly, a study of Li and Zhao (Citation2018) found a significant positive relationship between SCE and SG in both labor-intensive and capital-intensive Chinese firms. Oppong and Pattanayak (Citation2019) found similar results, that HCE has a positive effect on firms’ performance. Based on these findings, the study expects:

H4a: SCE positively affects firm profitability.

H4b: SCE positively affects firm productivity.

H4c: SCE positively affects firm market value.

H4d: SCE positively affects firm sales growth.

3. Methodology

The explanatory research design was used to explain the influence of intellectual capital and the performance of firms listed in Tanzania DSE. This study used panel data because the study focuses on multiple groups at multiple time intervals. The study did not use the time series data because time series focus on a single group at multiple time intervals. Further, panel data reduces the influence of inter-variable collinearity, controls individual heterogeneity, and increases the degrees of freedom, thereby improving the estimation efficiency (Hsiao, Citation2003). Secondary data were derived from the financial statements of firms registered in Dar es Salaam Stock Exchange (DSE) market in Tanzania. The DSE is still a small market with only 28 firms registered. Overall, data inclusion was based solely on the availability of financial data for each period as shown in Table .

Table 2. Sample Selection Based on the Data Availability

The researcher performed vigorous screening, and firms with missing data for more than 3 years were excluded from the data. In the end, the sample of the study comprises balanced panel data of 22 manufacturing and service sectors with 220 observations. The 10-years (2010–2019) were selected because the period gave more portrayal of the business issues and also by choosing a period earlier than this period, it could have reduced sample data.

3.1. Measurement of variables

The variables used in the study are classified into three categories: dependent, control and independent variables. Their measurement is shown below.

3.1.1. Dependent variable: Profitability (ROA)

Four performance indicators are taken as the dependent variables.

Return on assets is the accounting measure of the firm performance utilized in all types of business Studies (Sveiby, Citation2001). ROA indicates the ability of a firm in utilizing total assets and shows the profitability of a firm (B.G. Kamath, Citation2008; Sardo & Serrasqueiro, Citation2017). Various studies have utilized ROA to measure performance (Ahangar, Citation2011; Farrukh & Joiya, Citation2018; Vishnu & Gupta, Citation2014). It was measured as follows (natural logged) followed B.G. Kamath (Citation2008), Sardo and Serrasqueiro (Citation2017):

The asset turnover ratio (ATO) is the ratio of total revenue to the book value of total assets and measures firm productivity (B.G. Kamath, Citation2008; Nadeem et al., Citation2017) (natural logged).

Sales growth (SG) (Current year’s sales/last year’s sales) −1 × 100 (natural logged) which measures the deviations in a firm’s sales and indicates the probability of a firm’s growth G.B. Kamath (Citation2017), Li and Zhao (Citation2018).

Tobin’s Q (market value) is a proxy for the market value of a firm measured by the market value of equity + book value of debt)/Total sales (natural logged (Sardo & Serrasqueiro, Citation2017; Sarkar & Sarkar, Citation2000).

3.1.2. Independent variables

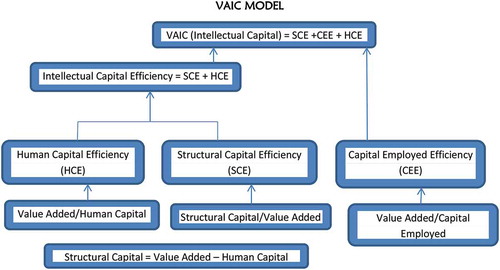

The value-added intellectual capital coefficient (VAIC) developed by (Pulic, Citation1998) is a broadly accepted measure of intellectual capital (Sveiby, Citation2001). Most studies have utilized this model to measure intellectual capital (Farrukh & Joiya, Citation2018; Vishnu & Gupta, Citation2014), etc. The VAIC helps to calculate the three parts of intellectual capital (IC) as shown hereunder:

where VAIC is Value Added Intellectual Coefficient, HCE is Human Capital Efficiency, CEE is Capital Employed Efficiency, and SCE is Structural Capital Efficiency.

These can be measured as follows:

where HCE is human capital efficiency, is value added for firm and

is an investment in Human Capital which includes total salary, wage and all incentives.

where CEE is capital employed efficiency and is book value of net assets.

where SCE is structural capital efficiency and is structural capital which is computed as follows:

The value added for firm i is calculated as follows:

where is the total interest expenses,

is depreciation expenses,

is payroll,

is dividends,

is corporate tax and

is profits retain for the year. The VAIC model is broadly acknowledged among the practitioners and researchers as an indicator for calculating IC and its components (Dženopoljac et al., Citation2016; G.B. Kamath, Citation2017; Nadeem et al., Citation2017). The model easily computes the efficiency of IC and also enables the user to make comparative analysis across different sectors and countries (Young et al., Citation2009).

3.1.3. Control variables

Since the study consists of firms from several different industries, therefore, industry dummy, firm size, and physical capacity were used as the control variables, in order to reduce the effect of other variables that might lead to model misspecifications (Deep & Narwal, Citation2015). They were measured as follows:

Size; Sales used as an indicator of firm size = Log (sales) Riahi-Belkaoui (Citation2003).

Physical capacity (PC) regulates the effect of fixed assets on firm performance = Fixed assets/Total assets (natural logged) Pal and Soriya (Citation2012).

Industry dummy variable examines sector-specific risk. SERV is assigned 1 if the firm belongs to the service industry and else 0. MANF is assigned 1 if the firm belongs to the manufacturing industry and else 0.

3.2. Model estimation

The regression model evaluates the relationship between financial performance and the three noteworthy parts of VAIC (HCE, SCE and CEE). The conceptual model is shown in Figure .

Figure 1. The Conceptual Model of Value Added Intellectual Coefficients (Pulic, Citation2000).

The models are as follows:

Model 1:

Model 2:

Model 3:

Model 4:

Model 5:

Model 6:

Model 7:

Model 8:

Model 9:

where the dependent variables are ROAi,t is the profitability, ATOi,t is the productivity, SGi,t is the sales growth of the firm of the current year and Tobin’s Qi,t is firms’ market value. The independent variables of firm performance indicators of the previous year are: ROAi,t−1, ATOi,t−1, SGi,t−1, Tobin’s Qi,t−1, CEEi,t−1, HCEi,t−1, SCEi,t−1, and VAICi,t, CEEi,t HCEi,t, and SCEi,t of the current year. MANF and SERV represent the product-oriented and service-oriented industry dummy variables. ηi are un-observable time-invariant firm effects and εi,t are error term is i, at current time period t.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Descriptive statistics

The descriptive statistics of the variables for the firms are presented in Table .

Table 3. Descriptive Statistics of the Variables for the Firms

The results from Table indicate that among the dependent variables the mean value for the ROA was 0.261 which was higher suggesting that some profits were generated by the firms. Then, Tobin’s Q followed with a mean value of 0.123. In this case, the value of Tobin’s Q is less than 1 implying that the firm’s market value is less than its book value. Therefore, it will not be judicious on the part of managers to replace capital or they will simply allow it to depreciate since the stock market values capital at less than its book value. It was followed by SG with the mean value of 0.110 and finally ATO with the mean value of 0.075 indicating productivity problems. The mean value of HCE was 1.398, and among the three VAIC components, it is the highest contributing factor. While the mean value for CEE was −0.551 and SCE was −0.632. The negative values for CEE and SCE suggest that during the study period, the firms were struggling to add value from their capital and structural. The mean value of value-added intellectual coefficient (VAIC) was −0.639. The negative value for VAIC implies that the investment cost in IC was greater than earnings. The mean value of revenue was 14,893.23. The mean value for the average profit of the firm was 5,245.84 and the mean value for the number of employees was 985.27. With regard to kurtosis and skewness, as according to Tabachnick and Fidell (Citation2019) the underestimation of variance associated with skewness or positive kurtosis, disappear with a sample of 100 or more cases. Therefore, skewness or kurtosis was not a problem in this specific data set.

4.2. Diagnostic tests

The findings of correlation analysis of the variables using Spearman Pearson correlation for the firms listed in DSE in Tanzania are shown in Table . The findings showed no high correlation between the variables implying no multicollinearity among the variables. As per Field (Citation2013), a correlation coefficient of more than 0.8 is a serious problem since it suggests that multicollinearity exists among the variables. The Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) was also conducted for each variable of the study and the findings of Table revealed that the values were less than 10 implying no problem of multicollinearity (Hair et al., Citation2019). Further, for the panel data with a series of 10 years and above, there is the possibility of non-stationary shocks that will affect the long-term equilibrium of the series.

Table 4. Correlation Matrix

In order to check for the data stationarity, a Levin-Lin-Chu (LLC) panel unit-root test was applied as it is relevant for panels of medium size (Levin et al., Citation2002). The significance p-value (p < 0.01) confirms data stationarity, and therefore, the data have no unit root (Table ). To begin the panel regression analysis, the Breusch and Pagan (Citation1980) was applied, and the results show that variances across entities are not zero (i.e., a panel effect exists), meaning pooled OLS becomes an inconsistent estimator of the panel data. Then, the application of fixed and random effects then follows, and Hausman test statistics are a basis for deciding between fixed and random effects. Hausman test detects the problem of endogeneity (i.e. whether an explanatory variable is correlated with the error term) in the regression model (Chmelarova, Citation2007). The findings of Hausman tests were significant (p < 0.05); therefore, the null hypothesis was rejected (random-effects model is consistent) and accepts the alternative (fixed effect model is consistent) meaning that the unique errors are correlated with the regressors. Then, cross-sectional dependence was checked, and the results reveal the presence of cross-sectional dependence, but it was not a problem in this study because it is not an issue in micro-panels with a large number of cases over a few years (Baltagi, Citation2008). Further, modified Wald statistic for group-wise heteroskedasticity was used, and the test results rejected the null hypothesis, indicating heteroskedasticity. The Wooldridge (Citation2010) test of autocorrelation was then applied, and the results confirmed the existence of the first-order autocorrelation. Hence, the study employs Rogers (Citation1993) clustered robust standard errors because it account for autocorrelation and heteroskedasticity across clusters of observation which is suitable for the balanced panel data.

Table 5. Panel Unit Root Tests for the Variables at Level

Furthermore, the findings of Table revealed that the ROA (present and previous year) is significantly (p ≤ 0.05) and negatively correlated with HCE and CEE with the exception of SCE and VAIC. These findings suggest that the manufacturing and service sectors in Tanzania have not utilized efficiently their human and capital. The findings are inconsistent with Forte et al. (Citation2019) who found out that only Human Capital efficiency shows a positive effect on firms’ financial performance while Structural Capital efficiency and Capital Employed efficiency exhibit a negative effect. Further, the findings show that VAIC is significantly (p ≤ 0.05) and positively correlated with HCE, CEE, and SCE. Furthermore, Tobin’s Q (present and previous year) was significantly (p ≤ 0.05) negatively correlated with HCEi,t = −0.078, HCEi,t-1 = −0.046 and positively correlated with value-added intellectual capital, VAICi,t = 0.054, VAICi,t-1 = 0.022. The findings imply that in the long run, VAIC influence positively market value of the company. Similarly, Tobin’s Q (present and previous year) have a significant negative correlation with CEEi,t = −0.020 (present year), and CEEi,t-1 = −0.091 (previous year), implying that in the long run, CEE influence negatively market value of the company. Moreover, ATO for the present shows a significant negative correlation with HCE and CEE with the exception of SCE implying more contribution of SCE on ATO as compared to HCE and SCE. With regards to SG, the findings showed a negative correlation with HCE, CEE except for SCE which showed a positive correlation with SG suggesting that SCE has a positive influence on the growth of the company. In general, the findings showed that SCE has a positive contribution to the company growth, market value, and productivity than the other variables of IC efficiency. However, the company needs to consider both financial and physical capital for the purpose of creating the value of the firm. Generally, the findings of this study imply that IC components do not influence the financial performance of the firms to the same extent as suggested by Albertini and Remy (Citation2019).

4.3. Regression results

The findings of the nine regressions models for the whole sample are shown in Table . The results of Table showed that models 1 and 2 for the relationship between ROA and intellectual capital variables (present and previous year), except SCE have a negative statistically significant impact (p < 0.05) with the profitability of the firms. For instance, CEE (coefficient = −0.488), CEEt-1 (coefficient = −0.310), HCE (coefficient = −0.873), HCEt-1 (coefficient = −0.702), SCEt-1 (coefficient = −0.233), firm size (coefficient = −0.001), PC (coefficient = −5.674). This implies that the manufacturing and service sectors in Tanzania have not employed efficiently their employees, innovations, and capital on improving the profitability of the manufacturing and service sectors. However, SCE for the present year was found to have a positive statistically significant impact (p < 0.05) on the profitability of the firms (coefficient = 0.350). This finding suggests for the present year, technology, research, and development are the driving force of the firms. This finding concurs with previous studies such as Holienka and Pilková (Citation2014), Smriti and Das (Citation2018), and Vishnu and Gupta, Citation2014. They found out that structural capital efficiency has a significant positive influence on the firm’s profitability of the firms.

Table 6. Regressions Results for Model 1 to Model 9 (Whole Sample)

Further, regression models 3 and 4 were examined using ATO, models 5 and 6 using SG, models 7, and 8 using Tobin’s Q. The findings revealed that SCE has a statistically significant (p < 0.05) positive impact with firm productivity (coefficient = 0.153), SG (coefficient = 0.136) and Tobin’s Q (coefficient = 0.083), whereas, others variables have a negative impact with ATO, SG and Tobin’s Q. These findings imply that Tanzania firms do not utilize efficiently their employees, capital, firm size, and physical capacity in generating revenues, productivity, and market value. The findings suggest that every IC part adversely influences firms’ financial performance, implying that while investors are crediting a significant amount of capital in order to generate growth and productivity; contrarily, the return on investment is negative. These outcomes are as per Pulic who expressed: “We have proof that esteem creation depends a lot more on scholarly potential than on physical capital” (Pulic, Citation1998, p. 14) and request further investigations, giving proof of the impacts of intellectual capital on the performance of the firms. With regards to the VAIC, the findings of modes 2, model 4, model 6 and model 8 showed a positive statistically significant impacts (p < 0.05) with ROA (coefficient = 0.652), ATO (coefficient = 0.435), SG (coefficient = 0.214) and Tobin’s Q (coefficient = 0.132), whereas, others have a negative impacts. Similarly, the finding of model 9 showed that VAIC was statistically positively significantly (p < 0.05) with the profitability of the firms. This finding implies that VAIC contribute significantly on the performance of the firms. The finding is consistent with Ekwe (Citation2012), who found a significant positive relationship with the profitability of the firms. In order to get more insight, the firms were separated into service and manufacturing and for the purpose of investigating the impact of intellectual capital on the performance of the firms. The findings are presented in Tables and .

Table 7. Regressions Results for Model 1 to Model 9 (Manufacturing Sector)

Table 8. Regressions Results for Model 1 to Model 9 (Service Sector)

The findings of Table of model 2, model 4, model 6, and model 8 showed that for the manufacturing sectors, VAIC influence positively ROA, SG, ATO, and Tobin’s Q at a 5% level of significance. However, CEE, HCE, for the present and previous years, firm size and PC were found to influence negatively the ROA, SG, ATO, and Tobin’s Q. However, SCE for the present year was found to influence positively ROA, SG, ATO, and Tobin’s Q at 5% and 10% levels of significance. The findings imply that the manufacturing firms in Tanzania should invest much in physical and financial assets which are the driving force of firms’ performance and value creation. This finding is in line with past studies such as Farrukh and Joiya (Citation2018), Vitalis (Citation2018) who found a positive relationship between structural capital employed and the firm’s financial performance. However, other studies such as Forte et al. (Citation2019) only Human Capital efficiency shows a positive effect on firms’ financial performance while Structural Capital efficiency and Capital Employed efficiency exhibit a negative effect.

Similarly, findings of Table of model 2, model 4, model 6, and model 8 showed that for the service sectors, VAIC influence positively ROA, SG, ATO, and Tobin’s Q at a 5% level of significance. These findings support the resource-based theory in the Tanzanian context. Thus, supports H1a to H1d which is in line with the findings of Nadeem et al. (Citation2017), Smriti and Das (Citation2018), and Tran and Hong (Citation2020). Nevertheless, with regards to the components of VAIC, the findings of model 1 to model 8 revealed that HCE, and CEE, PC, and firm size have a negative significant relationship with the ROA, SG, ATO, and Tobin’s Q at 5% and 10% levels of significance. These findings do reject H2a to H2d and H3a to H3d. These findings imply the underutilization of physical and financial capital in generating better firm performance in Tanzanian firms. These findings pose a doubt to the effectiveness of the service sectors in Tanzania towards the utilization of human capital and financial capital in enhancing their performance. This finding suggests that the service and manufacturing sectors operating in Tanzania should use their financial and physical capital if they wish to reach a higher profitability level. Further, the negative relationship between SCE and SG, ROA, ATO, and market value implies that investors fail to recognize the importance of human resources which exists in the form of employee’s knowledge, experience, skills, and aptitude. Other studies have found a significant positive association between human capital efficiency, capital employed efficiency, and financial performance of firms (Isanzu, Citation2015; Oppong & Pattanayak, Citation2019; Smriti & Das, Citation2018).

However, the findings of Tables –, for model 1 to model 8 revealed that SCE has a positive significant relationship with SG, ATO, ROA, and Tobin’s Q at 1%, 5% and 10% level of significances. This suggests that SCE affects sales growth, asset turnover, return on asset, and market value supporting H4a to H4d. This concurs with the finding of Omid and Mohamadreza (Citation2012) who found a positive relation between SCE and ROA and Tobin’s q. Generally, among the components of VAIC, SCE was found to have a big contribution to Tanzania listed firms.

5. Conclusion and recommendations

Given the developing pace and the requirement of knowledge in the business industry, firms that stay above peers are those that can more readily recognize their intellectual capital and create it. This has set IC as an important component that contributes value to firms. Despite the presence of previous research on intellectual capital and financial performance, researchers have been selective to single industries and overlooked the input of the service and manufacturing sectors as a whole. Thus, understanding of the significant contribution of different parts of IC is as yet prominent. This study adds to such need as it gives an emerging market proof to VAIC and its different parts (SCE, CEE, and HCE). In particular, the study evaluated the relationship between intellectual capital and the financial performance of service and manufacturing firms in Tanzania from 2010 to 2019 in terms of sales growth (SG), return on asset (ROA), asset turnover (ATO) and Tobin’s (market share). The panel regression analysis demonstrated a significant positive relationship between SCE and SG, ROA, ATO, and Tobin’s. This suggests there is proper investment in research and development. However, the effect of HCE and CEE were negative implying poor investment in human skills and the capital of the firms. It was also evidenced that VAIC was positively and significantly associated with SG, ATO, ROA, and Tobin’s Q. This, therefore, suggests the importance of VAIC in the financial performance of firms.

5.1. Implication to managers and policy makers

The findings of this study suggest that IC is significantly and positively related to the financial performance indicators of firms. The study demonstrated that VAIC is positively associated with sales growth, return on assets, asset turnover, and market share. The study also showed that Tobin’s Q indicator was predominant in both service and manufacturing firms which implies that IC significantly influences the firm’s market value irrespective of the firm type. However, the relationship between HCE and CEE sales growth, return on assets, asset turnover and market share were negative. The negative influence of HCE and CEE draws attention to managers of the firms to efficiently utilize capital employed and the skills of their employees to improve performance. Investment in human capital will, in turn, enhance employees’ knowledge. These together will lead to more innovations in products and processes. The SCE was found to have a positive influence on firms’ sales growth, profitability, productivity, and market share. This implies that there is a good utilization of investment in research and development as supported by Shah (Citation2006) who argued that the regulators must provide tax incentives in research and development to bring more innovation in services and manufacturing. Finally, policymakers and regulators should propose incentive programs to encourage investment in innovation, research, and development for better efficiency of the firm.

5.2. Implications for future researchers

This paper has evaluated intellectual capital and financial performance using panel regression analysis from service and manufacturing firms in Tanzania. This study is first to consider the IC across the manufacturing and service sectors in the Tanzanian economy using Public Value Added Intellectual Capital. The study controls for heteroscedasticity and endogeneity issues using Rogers (Citation1993) clustered robust standard errors because it accounts for autocorrelation and heteroskedasticity across clusters of observation which is suitable for the balanced panel data. Previous studies have generally focused on single industries (Isanzu, Citation2015), and have overlooked the input of the service and manufacturing sectors as a whole. This study offers new insight into the area of IC and its relation with firms’ performance in Tanzania and evaluates IC within the manufacturing and service sectors in totality. The findings indicate that the financial performances of firms are greatly influenced by SCE. The study acknowledges some limitations of this work which provide avenues for future research. First, only firms listed on DSE were included in the study. Future researchers could aim at increasing the sample size by conducting comparative analyses with other countries. Second, future researchers could deeply examine IC and financial performance by adding managerial challenges, and/or sociological factors associated with intellectual capital, including the role of ethnic groups where applicable.

Acknowledgements

The author is very thankful for the comments of the Editor and the anonymous reviewers which significantly improved the earlier version.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Pendo Shukrani Kasoga

Pendo Kasoga is a senior lecturer in the Department of Accounting and Finance at the University of Dodoma (UDOM), Tanzania. She holds a PhD in the area of microfinance from the University of Dodoma, Tanzania. She has published papers in local and international peer-reviewed journals in the areas of microfinance and corporate finance. Her research interests are microfinance, corporate finance, and corporate governance.

References

- Ahangar, R. G. (2011). The relationship between intellectual capital and financial performance: An empirical investigation in an Iranian company. African Journal of Business Management, 5(1), 88–26. DOI: 10.5897/AJBM10.712

- Albertini, E., & Remy, B. F. (2019). Intellectual capital and financial performance: A meta-analysis and research Agenda. Management, 22(2), 216–249. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333248565

- Amin, S., Usman, M., Sohail, N., & Aslam, S. (2018). Relationship between intellectual capital and financial performance: The moderating role of knowledge assets. Pakistan Journal of Commerce and Social Sciences, 12(2), 521-547.

- Anifowose, M., Abdul Rashid, H. M., Annuar, H. A., & Ibrahim, H. (2018). Intellectual capital efficiency and corporate book value: Evidence from Nigerian economy. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 19(3), 644–668. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-09-2016-0091

- Asare, N., Alhassan, L. A., Asamoah, E. M., & Gyamfi, N. M. (2017). Intellectual capital and profitability in an emerging insurance market. Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences, 33(1), 2–19. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEAS-06-2016-0016

- Baltagi, B. (2008). Econometric analysis of panel data. John Wiley & Sons. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S2214-8450(18)30214-X/sref2

- Bananuka, J. (2019). Intellectual capital, isomorphic forces and internet financial reporting: Evidence from Uganda’s financial services firms. Journal of Economic and Administrative Sciences, 36(2), 110–133. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEAS-03-2018-0042

- Barney, J. (2001b). Resource-based theories of competitive advantage: A ten-year retrospective on the resource-based view. Journal of Management, 27(6), 643–650. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630102700602

- Bollen, L., Vergauwen, P., & Schnieders, S. (2005). Linking intellectual capital and intellectual property to company performance. Management Decision, 43(9), 1161–1185. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740510626254

- Bontis, N. (1998). Intellectual capital: An exploratory study that develops measures and models. Management Decision, 36(2), 63–76. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251749810204142

- Bontis, N., Janošević, S., & Dženopoljac, V. (2015). Intellectual capital in Serbia’s hotel industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 27(6), 1365–1384. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-12-2013-0541

- Breusch, T. S., & Pagan, A. R. (1980). The Lagrange Multiplier Test and its Applications to Model Specification in Econometrics. The Review of Economic Studies, 47(1), 239-253. Downloaded from 197.250.229.166. http://www.jstor.com/stable/2297111166 1 47 239 doi:10.2307/2297111

- Carneiro, R. (2003). A Era do Conhecimento. In Silva and Neves (Orgs) Gestão de Empresas na Era do Conhecimento, Lisboa. Edições Sílabo.

- Chan, K. H. (2009b). Impact of intellectual capital on organisational performance. The Learning Organization, 16(1),22-39. DOI: 10.1108/09696470910927650

- Chen, M. C., Cheng, S. J., & Hwang, Y. (2005). An empirical investigation of the relationship between intellectual capital and firms’ market value and financial performance. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 6(2), 159–176. https://doi.org/10.1108/14691930510592771

- Chmelarova, V. (2007). The hausman test and some alternative, with heteroskedastic data. Louisiana StateUniversity of Agriculture and Mechanical College. http://etd.lsu.edu/docs/available/etd-01242007-165928/unrestricted/chmelarova_dis.pdf

- Chowdhury, M. A. L., Rana, T., Akter, M., & Hoque, M. (2018). Impact of intellectual capital on financial performance: Evidence from the Bangladeshi textile sector. Journal of Accounting and Organizational Change, 14(4), 429–454. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAOC-11-2017-0109

- Deep, S. R., & Narwal, K. P. (2015). Intellectual capital and its consequences on company performance: A study of Indian sectors. International Journal of Learning and Intellectual Capital, 12(3), 300–322. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJLIC.2015.070169

- Duho, K. C. T. (2020). Intellectual capital and technical efficiency of banks in an emerging market: A sack-based measure. Journal of Economic Studies. https://doi.org/10.1108/JES-06-2019-0295

- Dženopoljac, V., Janoševic, S., & Bontis, N. (2016). Intellectual capital and financial performance in the Serbian ICT industry. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 17(2), 373–396. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-07-2015-0068

- Ekwe, C. M. (2012). Intellectual capital and financial performance in an emerging economy: An empirical investigation of a Nigerian Bank. Ushus JBMgt, 11(2), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.12725/ujbm.21.1

- Farrukh, W., & Joiya, J. Q. (2018). The impact of intellectual capital on firm performance. International Journal of Management and Economics Invention, 4(10), 1943–1952. DOI:10.31142/ijmei/v4i10.01

- Field, A. (2013). Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics (3rd ed.). Sage, London

- Forte, W., Matonti, G., & Giuseppe Nicolò, G. (2019). The impact of intellectual capital on firms’ financial performance and market value: Empirical evidence from italian listed firms. African Journal of Business Management, 13(5), 147–159. https://doi.org/10.5897/AJBM2018.8725

- Fulk, J., & DeSanctis, G. (1995). Electronic communication and changing organizational forms. Organization Science, 6(4), 337–349. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.6.4.337

- Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

- Hamdan, A. (2018). Intellectual capital and firm performance: Differentiating between accounting based and market-based performance. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management, 11(1), 139–151. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMEFM-02-2017-0053

- Helfat, C., & Peteraf, M. (2003). The dynamic resource-based view: Capability lifecycles. Strategic Management Journal, 24(10), 997–1010. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.332

- Holienka, M., & Pilková, A. (2014). Impact of intellectual capital and its components on firm performance before and after crisis. The Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management, 2(4), 261–272. www.ejkm.com

- Hoskisson, R., Hitt, M., Wan, W., & Yiu, D. (1999). Theory and research in strategic management: Swings of a pendulum. Journal of Management, 25(3), 417–456. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639902500307

- Hsiao, C. (2003). Analysis of panel data. Cambridge University Press.

- Isanzu, J. N. (2015). Impact of intellectual capital on financial performance of banks in Tanzania. Journal of International Business Research and Marketing, 1(1), 16–23. https://doi.org/10.18775/jibrm.1849-8558.2015.11.3002

- Jummaini, N. A., & Hasan, B. (2019). Intellectual capital and financial performance: The role of good corporate governance (Study on Islamic Banking in Indonesia). In Social Sciences on Sustainable Development for World Challenge: The First Economics, Law, Education and Humanities International Conference (pp. 1–9). KnE Social Sciences.

- Kaawaase, T. K., Bananuka, J., Peter Kwizina, T., & Nabaweesi, J. (2019). Intellectual capital and performance of small and medium audit practices: The interactive effects of professionalism. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, 10(2), 165–189. https://doi.org/10.1108/JAEE-03-2018-0032

- Kamath, B. G. (2008). Intellectual capital and corporate performance in Indian pharmaceutical industry. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 9(4), 684–704. https://doi.org/10.1108/14691930810913221

- Kamath, G. B. (2017). An investigation into intellectual capital efficiency and export performance of firms in India. International Journal of Learning and Intellectual Capital, 14(1), 47–75. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJLIC.2017.080641

- Kanchana, N., & Mohan, R. R. (2017). A review of empirical studies in intellectual capital and firm performance. Indian Journal of Commerce & Management Studies, 8(1), 52–58. DOI: 10.18843/IJCMS/V811/08

- Keregero, C. M. (2016). A study on the performance of textile sector in Tanzania - Challenges and ways forward. Journal of Business and Management, 4(5), 1–14.

- Levin, A., Lin, C. F., & Chu, C. S. J. (2002). Unit Root Tests in Panel Data: Asymptotic and Finite-Sample Properties. Journal of Econometrics, 108(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4076(01)00098-7

- Li, Y., & Zhao, Z. (2018). The dynamic impact of intellectual capital on firm value: Evidence from China. Applied Economics Letters, 25(1), 19–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2017.1290769

- Makhija, M. (2003). Comparing the resource-based and the market-based views of the firm: empirical evidence from the Czech privatisation. Strategic Management Journal, 24(5), 433–451. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.304

- Nadeem, M., Gan, C., & Nguyen, C. (2017). Does intellectual capital efficiency improve firm performance in BRICS economies? A dynamic panel estimation. Measuring Business Excellence, 21(1), 65–85. https://doi.org/10.1108/MBE-12-2015-0055

- Nimtrakoon, S. (2015). The relationship between intellectual capital, Firms’ market value and financial performance: Empirical evidence from the ASEAN. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 16(3), 587–618. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-09-2014-0104

- Omid, A., & Mohamadreza, A. (2012). The relationship between intellectual capital and performance of companies (A Case study of Cement Companies Listed in Tehran Stock exchange). World Applied Sciences Journal, 20(4), 520–526. DOI: 10.5829/idosi.wasj.2012.20.04.2577

- Oppong, G. K., & Pattanayak, J. K. (2019). Does investing in intellectual capital improve productivity? Panel evidence from commercial banks in India. Borsa Istanbul Review, 19(3), 219–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bir.2019.03.001

- Oppong, G. K., Pattanayak, J. K., & Irfan, M. (2019). Impact of intellectual capital on productivity of insurance companies in Ghana: A panel data analysis with system GMM estimation. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 20(6), 763–783. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-12-2018-0220

- Ozkan, N., Cakan, S., & Kayacan, M. (2017). Intellectual capital and financial performance: A study of the Turkish banking sector. Borsa Istanbul Review, 17(3), 90–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bir.2016.03.001

- Pal, K., & Soriya, S. (2012). IC performance of Indian pharmaceutical and textile industry. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 13(1), 120–137. https://doi.org/10.1108/14691931211196240

- Penrose, E. (1959). The theory of the growth of the firm. Basil Blackwell Publisher.

- Peteraf, M. (1993). The cornerstones of competitive advantage: A resource-based view. Strategic Management Journal, 14(13), 363–380. https:/doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250140303

- Poh, T. L., Kilicman, A., & Ibrahim, I. N. S. (2018). Intellectual capital and financial performances of banks in Malaysia. Cogent Economics and Finance, 6(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2018.1453574

- Pulic, A. (1998). Measuring the performance of intellectual potential in knowledge economy [Paper presentation]. Second McMaster World Congress on Measuring and Managing Intellectual Capital. Hamilton.

- Pulic, A. (2000). VAICTM-an accounting tool for IC management. International Journal of Technology, Management, 20(5–8), 702–714. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTM.2000.002891

- Reinhardt, R., Bornemann, M., Pawlowsky, P., & Schneider, U. (2003). Intellectual capital and knowledge mangement: Perspectives on measuring knowledge. In Dierkes, Antal, Child and Nonaka Ed., Handbook of organizational learning & knowledge (pp. 794–820). Oxford University Press.

- Riahi-Belkaoui, A. (2003). Intellectual capital and firm performance of US multinational firms: A study of the resource-based and stakeholder views. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 4(2), 215–226. https://doi.org/10.1108/14691930310472839

- Rogers, W. (1993). Regression standard errors in clustered samples. Stata Technical Bulletin, 3(13), 19–23. https:/doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250140303

- Roos, G., Roos, J., Edvinsson, L., & Dragonetti, N. (1997). Intellectual capital: Navigating in the new business landscape. Macmillan.

- Rouse, M., & Daellenbach, U. (2002). More thinking on research methods for the resource-based perspective. Strategic Management Journal, 23(10), 963–967. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.256

- Sardo, F., & Serrasqueiro, Z. (2017). A European empirical study of the relationship between firms’ intellectual capital, financial performance and market value. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 18(4), 771–788. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-10-2016-0105

- Sarkar, J., & Sarkar, S. (2000). Large shareholder activism in corporate governance in developing countries: Evidence from India. International Review of Finance, 1(3), 161–194. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2443.00010

- Shah, A. (2006). Fiscal incentives for investment and innovation. Retrieved October 7, 2017, from https://ssrn.com/abstract=896144

- Sharabati, A. A. A., Naji, J. S., & Bontis, N. (2020). Intellectual Capital and Business Performance in the Pharmaceutical Sector of Jordan. Management Decision, 48(1),105-131. DOI: 10.1108/00251741011014481

- Smriti, N., & Das, N. (2018). The impact of intellectual capital on firm performance: A study of indian firms listed in COSPI. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 19(5), 935–964. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-11-2017-0156

- Stewart, T., & Ruckdeschel, C. (1998). Intellectual Capital: The New Wealth of Organizations. Performance Improvement, 37(7),56-59. Wiley Online Library, London. Retrieved from www.depdyve.com/ip/wiley/intellectual-capital-the-new-wealth-of-organzations-9ry51PqHA4 doi:10.1002/(ISSN)1930-8272

- Sveiby, K. E. (2001). A knowledge-based theory of the firm to guide the strategy formulation. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 2(4), 344–358. https://doi.org/10.1108/14691930110409651

- Szulanski, G. (2002). Sticky knowledge: Barriers to knowing in the firm. Sage Publications.

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2019). Using multivariate statistics (7th ed.). Allyn and Bacon.

- Tran, P. N., & Hong, V. D. (2020). Human capital efficiency and firm performance across sectors in an emerging market. Cogent Business & Management, 7(1), 1,1–15. To link to this article. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2020.1738832

- URT. (2018). Tanzania industrial competitive report. United Republic of Tanzania.

- Vătămănescu, E. M., Gorgos, E. A., Ghigiu, A. M., & Monica Pătruț, M. (2019). Bridging intellectual capital and SMEs internationalization through the lens of sustainable competitive advantage: A systematic literature. Sustainability, 11(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11092510

- Vishnu, S. and Gupta, V.K. (2014). Intellectual capital and performance of pharmaceutical firms in India. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 15(1), 83–99. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIC-04-2013-0049

- Vitalis, E. (2018). Effect of intellectual capital on performance of firms listed on nigeria stock exchange. Research Journal of Finance and Accounting, 9(8), 138–150. www.iiste.org/tag/research-joirnal-of-finance and accounting-impact-factor/

- Wangwe, J. M. (2018). Industrial development in Tanzania. Oxford University Press.

- Wangwe, S., Mmari, D., Aikaeli, J., Rutatina, N., Mboghoina, T., & Koyondo, A. (2016). The performance of the manufacturing sector in Tanzania: Challenges and the way forward. Learning to Complete: Working Paper No. 22.

- Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5(2), 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250050207

- Wiklund, J., & Shepherd, D. (2003). Knowledge-based resources, entrepreneurial orientation, and the performance of small and medium-sized businesses. Strategic Management Journal, 24(13), 1307–1314. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.360

- Wooldridge, J. M. (2010). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. MIT Press. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S2214-8450(18)30214-X/sref46

- Xu, J., & Wang, B. (2018). Intellectual capital, financial performance and companies’ sustainable growth: Evidence from the korean manufacturing industry. Journal of Sustainability, 10(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020001

- Xu, J., & Wang, B. (2019). Intellectual capital performance of the textile industry in emerging markets: A comparison with China and South Korea. Sustainability, 11(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11236582

- Young, C. S., Su, H. Y., Fang, S. C., & Fang, S. R. (2009). Cross-Country Comparison of Intellectual Capital Performance of commercial Banks in Asian Economies. The Service Industries Journal, 29(11), 1565–1579. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642060902793284

- Zack, M. (2003). Rethinking the knowledge-based organization. Sloan Management Review, 44(4), 67–71. sloanreview.mit.edu/wp-content/uploads/saleable-pdfs/4410.pdf