?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The policy responses to capital flows in emerging markets are multiple. However, capital inflow controls, if applied sufficiently broadly, can buttress all other policies by limiting the volume of capital inflows and address balance sheet vulnerabilities. The study analyzes the effects of capital controls (CC) domestically and internationally. Applied to 24 emerging economies (EEs) from 2009 to 2016, a panel vector autoregression model using a quarter dataset provides further evidence on these effects. Domestically, the results show that following the 2008 financial crisis, strengthening CC may support policymakers’ actions to improve their macroeconomic policies. Unpredictably, there is no relationship founded between CC and international reserves accumulation. However, a combination of controls and reserves are needed to manage well the volatile capital flows. Internationally, restrictions on capital flows may cause spillovers between countries introducing controls and neighboring countries. These multilateral effects raise the challenge of optimal policy coordination.

Keywords:

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

The study analyzes the domestic and international impacts of capital controls. The findings highlight the necessary coordination between different macroeconomic policies, particularly, those related to capital controls. Policymakers need to use effectively the restrictive policy to curb capital inflows and to support the overall macroeconomic policy. Regarding the spillovers of capital controls, these effects give rise to the requirement of actions harmonization, internally, and between countries, before deciding to introduce CC. Globally, Governments through the use of restrictions on capital account face the challenge of finding an optimal policy mix.

1. Introduction

The 2008 financial crisis and its consequence of boom-bust cycles in cross-border capital flows of exceptional scale, reviving debates on whether—and how—to cope with these flows. Conventionally, EE were recommended not to obstruct capital flows, but to employ exchange rate flexibility and careful monetary policy in front of large inflows. Yet since 2008, there have been recommended for EEs to take a more active position and deploy wide array of policy tools—including cautiousness measures and capital controls—to better manage the eventual risks related to capital movements. The issues that capital flows pose to EEs are often totally distinct from those they pose to advanced countries. It is also only over the past years that most EEs have opened their frontiers to capital flows sufficiently that great flows produce the risks that might require an effective response.

Effective CC reduce capital flows volume, alter the composition from short-term to long-term capital flows, make more stable the exchange rate, and allow autonomy of the monetary policy (Magud et al., Citation2018). Previous studies have highlighted various problems concerning capital control, it is unclear whether these controls achieve their objective or not (Benigno et al., Citation2013; Bianchi & Mendoza, Citation2011; Korinek, Citation2011). The identified problems include the absence of a theoretical framework to define the macroeconomics consequences of these controls, heterogeneity between countries applying CC, and the success of these restrictions. Several studies have also identified the difficulties occurring due to isolation of the direct effect of CC, which limits the success of capital flows and their objectives (Alfaro et al., Citation2017; Fernández et al., Citation2015; Forbes et al., Citation2015). CC are used in countries all around the globe, but the efficiency is still not clear. It is complicated for developing a standard of best practices to accomplish the influential regulation of international capital flows due to specific characteristics of economies and different market responses (Forbes et al., Citation2015). There are two aspects of studying the effectiveness of CC: (a) actions on capital control and (b) achieving macroeconomic objectives (autonomy of monetary policy, reduction of exchange rate pressures, etc.). The present study has discussed the impact of controls on emerging markets. After the Great Recession 2008, several economies used restrictions especially, on short term capital inflows, while others increased these restrictions (Fernández et al., Citation2015). The study is associated with the studies of monetary policy and exchange policy in influencing the financial crisis nature. Recently, monetary policy is restricted by the global financial cycle under a flexible exchange rate regime when capital flow management is preferable to maintain monetary autonomy, and there is free capital mobility (Passari & Rey, Citation2015; Rey, Citation2015). Optimal CC and monetary policy were explored with small open countries, considering risk premium shocks (Farhi & Werning, Citation2014). These studies have reported that CC retain monetary autonomy in a fixed exchange rate and work as trade manipulation in a flexible exchange rate regime. Exchange rate policies are beneficial to lower the severity of a financial crisis beyond CC (Benigno et al., Citation2016; Chamon & Garcia, Citation2016). Likewise, Devereux et al. (Citation2017) have shown that CC can be considered as state-improving tools when optimally merged with monetary policy in the presence of policy commitment. Many older studies on CC was focused on the incompatibility triangle so that CC was usually related to hope for keeping an extent of autonomy of the monetary policy although applying fixed exchange regimes. Last several years, some emerging economies tend to use a more flexible exchange rate. The fear of floating will cause these countries to intervene massively on the exchange markets or to vary their director rate to prevent huge fluctuations in the exchange rate.

We contribute to previous empirical studies in two ways. First, we use a recent, large dataset on capital control acts, which give us to more exactly detect the policy whose efficiency is evaluated. Most of the previous studies on the effectiveness of CC have used infrequent data, usually annual. The capital control measures thus used are less precise, they suffer from two essential shortcomings, they do not reflect a fair intensity of their application among the countries and are often confused with other policies simultaneously applied with CC. The use of quarterly data in this study allows for a larger time interval and allows for a more correct analysis of the actions taken by policymakers.

Second, the efficiency of CC is examining by the use of a model regrouping the components of monetary policy trilemma which indicates that it is difficult to use together with a fixed exchange rate, an independent monetary policy, and an open capital account. These components are usually studied undependably. A major contribution of the paper is to regroup the three elements of the incompatibility triangle in one model. The incompatibility triangle framework also presents that the de jure and de facto changes in the opening of the capital account are related (Rebucci & Ma, Citation2019). This is how we can examine whether the applied controls are effective from this incompatibility triangle. We thus test, from a Panel VAR model, whether capital markets affect the autonomy of monetary policy and changes in the exchange rate. As presented in several studies, CC are endogenous, which highlights the recurrent changes in these controls among countries and therefore we will know their repercussions on other macroeconomic policies. To our knowledge, there is no previous study using a Panel VAR approach to study the repercussions of CC changes on monetary and exchange policies.

As regards CC effects, we analyze the domestic and multilateral impacts. Domestically, our main finding is that CC by reducing capital inflows makes it possible to better stabilize the economy. It allows more independence to monetary policy and allows less pressure on the exchange policy at which the exchange rate manifests slight fluctuations.

Empirical evidence shows that EEs accumulated excessive international reserves after the 2008 crisis. Our study has shown that despite the strict capital controls applied, after the crisis, by several emerging countries, this did not prevent the accumulation of reserves. The latter supported the decisions of monetary policy and exchange rate policy. As our knowledge few previous studies have highlighted the association between capital controls actions with the accumulation of international reserves (Jeanne, Citation2016; Korinek, Citation2018).

For the multilateral effects, the study presents an understanding of the spillovers that may happen following restrictions applied by a country. The other countries will be affected after the migration of capital flows to their frontiers. Little empirical evidence exists on this spillover effect (Forbes et al., Citation2017; Lambert et al., Citation2011; Zehri, Citation2020). We were among the first to demonstrate empirically these policy changes towards capital controls as a reaction to the early policy of another country which has already applied similar controls.

Our paper is organized as follows. After displaying the literature review of the impacts of CC in Section 2, we present the data and methodology in Section 3. The results of the model regressions are presented in Section 4. The last section gives conclusions.

2. Capital controls impacts

2.1. Impacts on monetary and exchange rate policies

The theoretical and empirical literature on the effectiveness of CC on monetary and exchange policies has several methodological shortcomings. There are several criticisms for the indexes used to reflect the intensity of CC. It is often difficult to separate the effects caused by controls from effects caused by other macroeconomic policies such as the effectiveness of prudential supervision. The CC in different countries have been successful; however, the degree of success is not equal for all countries.

The empirical literature shows multiple impacts of CC on variables proxies of monetary and exchange policies. Some recent studies have shown evidence that these controls can effectively affect the monetary and exchange policies under some macroeconomic conditions and also can protect economies from external shocks (Pasricha et al., Citation2018; Magud et al., Citation2018). Some studies are focused on the macroeconomic framework in which CC are instituted. Among these studies, Bayoumi et al. (Citation2015) studied 37 countries that introduced outflow restrictions from 1995–2010. The results found evidence that capital outflow restrictions reduce the pressure on both policies under certain conditions. These conditions include strong macroeconomic fundamentals (growth rate, inflation, fiscal and current account balances), good institutions (World Bank Governance Effectiveness Index), and existing restrictions (intensity of CC or comprehensiveness). When none of the three conditions are met, controls will fail to support these policies. Furthermore, some studies suggest that controls are more effective in advanced countries than in others, perhaps because of the better quality of institutions and regulations (Binici et al., Citation2010).

Some recent studies (Pasricha et al. (Citation2018) and Magud et al. (Citation2018)) analyzed the conditions of success of capital controls and especially their impacts on the country which applies these controls as for the countries which did not apply these restrictions. Pasricha et al. (Citation2018) have used a recent frequency dataset on capital control instruments in 16 emerging market economies from 2001 to 2012, they give novel evidence on the domestic and multilateral impacts of these instruments. Increases in financial liberalization constraint monetary policy autonomy and decrease exchange rate instability, confirming the incompatibility trilemma. Magud et al. (Citation2018) present a meta-analysis of the literature on CC. The authors sought to standardize the results of the close to 40 empirical studies. They build two indices of capital controls: Capital Controls Effectiveness Index, and Weighted Capital Controls Effectiveness Index. Their results show that CC on inflows seems to make monetary policy more independent and alter the composition of capital flows; there is less evidence that they reduce real exchange rate pressures. Kim and Yang (Citation2012) determine that a fixed exchange rate allows CC to support the independence of the monetary policy. This impact is clearer with wide and long time CC.

Klein and Shambaugh (Citation2015) find that economies with large CC are more covered concerning external monetary shocks. Liu and Spiegel (Citation2015) show that the wide use of CC allows countries to maintain the desired interest rate differential between domestic and foreign markets. Besides, these strict controls didn’t have any link with the currency appreciation detected in some countries of their sample. Ito et al. (Citation2015) studied a small open economy and focused on simple policy rules; while, Devereux et al. (Citation2019) investigated the optimal monetary policy and optimal CC. A model with fixed exchange rates, downward nominal wage rigidities, and free capital mobility was presented by Bayoumi et al. (Citation2015), where an optimal devaluation eliminates the effects of the wage rigidity.

Table summarizes the results of most studies on this issue and shows that the “Inconclusive” effect dominates the findings.

Table 1. Summary of studies’ results

2.2. Capital controls indexes

Give an exact measure of CC is a hard task. The pre-2008 crisis literature utilizes indexes measuring the degree of capital restrictions. These indexes serve usually to set the extent of restrictions (kind of transactions controlled) and then define which is the most appropriate when evaluating the efficiency of controls. Many improvements in measuring CC are made by recent literature. The relevant novelties of these studies are gathering data on variations in institutional arrangements (Edison & Warnock, Citation2003; Ocampo et al., Citation2008; Qureshi et al., Citation2011). The advantage of this method is to exactly determine the type of policy action consistent with the time of the action. As discussed in the introduction, the puzzle of similarities of policy effects over time and across EEs continues to arise with this approach.

Finding an exact measure of CC is a difficult task. The empirical literature has employed multiple indexes as proxies for CC intensity, which usually help to set the extent of restrictions (Chinn & Ito, Citation2008; Edison & Warnock, Citation2003; Eichengreen & Rose, Citation2014; Fernández et al., Citation2016; Rebucci & Ma, Citation2019). Then it was possible to define which is the most appropriate when evaluating the efficiency of controls. Fernández et al. (Citation2016) presented a new dataset of CC, divided into 10 asset categories along with the structure of inflows and outflows. These indexes were applied to 100 economies over the period between 1995 and 2013. The present study uses the first 3 indexes of the ten asset categories of CC—ka, kai, and kao (controls applied to gross flows, inflows, and outflows, respectively). Chinn and Ito (Citation2008) established an index called kaopen, which measures the extent of openness in capital account transactions, and has been regularly updated (the last update was in 2017). The kaopen index is a proxy for the country’s level of CC, using a dual variable that summarizes the operations displayed in the IMF’s Annual Report on Exchange Arrangements and Exchange Restrictions (AREAER) database. Kaopen is applied to 182 economies covering the period between 1970 and 2010 and varies between −1.9 (more capital controls) and 2.5 (fewer capital controls).

The principal distinction between both indexes is that the KAOPEN index is a larger measure of capital account liberalization, including besides regulations to the current account of the balance of payments and on the foreign exchange market, while the Fernández et al. (Citation2016) dataset is smaller, focusing especially on capital flows, however, has further details on the intensity of controls, with distribution data on 10 asset categories. The Fernández et al. (Citation2016) indexes allow detecting more time change when countries set regulations than the Chinn-Ito index. These indexes (Chinn & Ito, Citation2008; Fernández et al., Citation2016) catch the cross-country changes in the level of capital account liberalization, unfortunately, they are smaller on the time scope due to their building approach and annual frequency. To divert these shortcomings, we propose to duplicate each annual value of each of these indexes in 4 equals’ sub-values, as being quarterly data. This does nothing to lose the robustness of this analysis since CC are often long-term political instruments. This change will allow consistency with the frequency of the other variables in the model which are quarterly. The description, source data, and notation of all study variables and CC indexes are displayed in Table .

Table 2. Variables description

3. Data and methodology

Capital control instruments may affect a set of variables, at the same time, can be affected by these variables. Thus, we use a Panel VAR model. This model includes a system of equations in which the dependent variables will be representative of CC, capital flows, monetary policy and exchange rate policy. Our sample includes 24 emerging economies experienced with CC over the period 2009Q1 to 2016Q4.Footnote1

We use the interest rate differential as a proxy for monetary policy independence (rate variable). A country which maintains a differential of domestic and external interest rate allows to act on the volume of capital inflows and consequently to define a domestic interest rate freely without having a constraint with the external rate. The standard deviation of the bilateral exchange rate (to the US $) is a proxy used for the volatility of the exchange rate (xchge variable). To separate the effect of capital flows variables we distribute them between inflows (infl variable) and outflows (outf variable). We include a set of exogenous variables to control for drivers that can influence the endogenous variables—the short-term interest rate in the United States (fed), the oil price (oil), and real gross domestic product growth in the United States (gdp). To study the impacts of CC on international reserves, we introduce the international reserves variable (ir). The impact of CC used by a country can affect the inflows to other countries, these spillover effects are proxy by the variable (spill). To build this variable, we follow the approach of Furceri and Loungani (Citation2018), who defined it as an episode where the annual change of the capital inflows exceeds by two standard deviations the average annual change overall observations.

Table shows the result of unit root tests using the ADF unit root test at the first difference level. The null hypothesis of nonstationarity is performed at 1% and 5% significance levels. In Table , the result of the ADF test illustrates that all the data series are nonstationary at the level. However, the result of the ADF test on the first difference strongly supports that all data series are stationary after the first difference at the 1% or 5% significance levels.

Table 3. Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test—Results for unit roots

A panel VAR is the baseline model. The independent variables of this model are all considered endogenous and are explained by a set of exogenous variables previously cited. The model is written as follow:

We use a Panel VAR approach which presents many advantages. When there are few theoretical studies on this relationship, the use of the Panel VAR is recommended for the guidance of the model formulation. For our study, rare is the theoretical literature that examines, particularly, the spillover effect of CC. The endogeneity bias presents a serious problem for many empirical studies on capital controls. These studies have taken into consideration this problem and have tried to solve it by including lagged variables or by imposing additional restrictions to their regressions. Panel VAR may reduce the endogeneity bias by considering all variables as probably endogenous. The Panel VAR approach allows us to analyze the impulse response functions which record any retarded effects of the considered variables; the classical panel models are unable to display these dynamic effects. The missed variable bias is also considered with Panel VAR by employing the country fixed effects, which catch time-unchanging parts that may affect domestic and international impacts of capital controls. Panel VAR has also the merit to be used with a short temporary scale which may be compensated by the gain from the cross-sectional scale.

Our model is described by a system of equations, where Yt is the vector of endogenous variables for country i, defined as Yt = [rate, xchge, and ir], xt is the vector of exogenous variables common to all countries, £i,t is the vector of residuals, and “Z” and “W” represents respectively the coefficients for the endogenous and exogenous variables. The vector Z includes the four capital controls indexes, Z = [kaopen, ka, kai, and kao]. These indexes are introduced in the first difference to highlight the changes in capital flows restrictions. The study employs a fixed-effect estimation method to control for effects of country-specific features. These factors were omitted and may affect the dynamics of the model, and the term “FEi” in Equationequation 1(1)

(1) takes into account these countries’ fixed effects. Similarly, the vector “xt” is composed of three exogenous variables: fed, oil, and gdp. These variables are used to control for drivers that can cause symmetric shocks to all countries. To examine if the cross-sectional changes in CC can be well used, we regress the model with the use of the Chinn-Ito (Chinn & Ito, Citation2008) and Fernández et al. (Citation2016) indexes. All of the explicative’s variables are introduced with one lag length. Besides, we propose a regression with the levels of these indexes and analyze the effect of a shock to them.

4. Results

In this section, we present the evidence from the estimation of the PVAR model for the period 2009:1–2016:4. We analyze if variations in CC are effective on monetary and exchange rate policies and are under the forecasts of the incompatibility triangle. We investigate also the impact on international reserves and the multilateral effects. We are examining the effect of a shock to CC, considered as an inside policy instrument, on different national policy variables including differential interest rate, exchange rate volatility, capital movements, international reserves accumulation, spillover effect further exogenous variables, fixed effects country and constant.

The results of the PVAR analysis are displayed in Tables and . The results show that CC indexes were more effective after the financial crisis compared to the period before the crisis; the coefficients of CC indexes in the second period are more significant. Basing on the results of Table , we note a positive and significant coefficient of the changes in “ka” and “kaopen” in the equation in which the differential interest rate is the independent variable. These findings show that changes in capital controls rise the differential of interest rate and subsequently allow more autonomy of the monetary policy. The two other indexes of capital controls (kai and kao) are without effect on the monetary policy. The results present negative and significant coefficients of the changes in “ka” and “kaopen” in the equation of exchange rate volatility (comparing to the US dollar) suggesting that capital controls support the stability of the exchange rate policy i.e. more liberalization conduct to higher exchange rate instability.

Table 4. Impacts Analysis (Panel Vector Autoregressive model, before the 2008 crisis)

Table 5. Impacts Analysis (Panel Vector Autoregressive model, after the 2008 crisis)

The trilemma purpose is confirmed using the index related to gross flows (ka). However, for the two other indexes for inflows and outflows controls (kai and kao), results are insignificant. By the use of the Chinn-Ito index results support the compromises of the incompatibility triangle. The decomposition of the annual data from these indexes into quarterly data is very useful, it has made it possible to have a greater frequency of data and has also made it possible to highlight the variations made to these restrictive policies in the short term.

The Granger causality test, presented in Table , confirms the previous results. It demonstrates the presence of causality between the indexes of capital controls with the “rate” and “xchge” i.e. the CC actions cause the monetary and the exchange policies.

Table 6. Granger Causality Test

As displayed in Table , this causality is bidirectional for the indexes “ka” and “kaopen” and unidirectional for “kai” and “kao” indexes.

Table 7. Direction of Causality

We suppose that the vector of endogenous variables listed in the system represented as: Yt = [rate, xchge, ir and spill]. To investigate the fraction of the fluctuations in the endogenous variables that are due to the capital controls shock, Table summarizes the forecast-error variance decomposition. The findings of Table show that unpredicted changes in the “ka” and “kaopen” indexes explain a big percentage of the dynamics in differential interest rate (78.1% and 78.8%, respectively) and the exchange rate fluctuation (78.4% and 81.5%, respectively) at the 4-quarters horizon.

Table 8. Forecast-error variance decomposition due to a CC shocks

Concerning the impact on international reserves, for 4 quarters ahead, the “ka” and “kaopen” shocks explain 75.4% and 52.1% respectively, the variation in international reserves and 59.5% and 52.1% respectively, the variation in spillovers. The impact of the CC indexes shocks on “spill” is also great, demonstrating that CC conduct intensively to spillover on other countries.

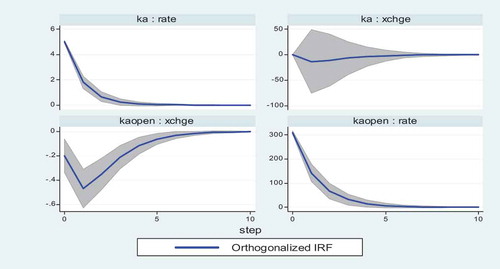

Figure displays the impulse-response functions to a positive shock in CC indexes (kaopen and ka) after a one unit shock on capital account (i.e. a rise by one weighted unit in capital account restriction). These effects are significant and happen rapidly following the shock, however, they remain for a short time. For the exchange rate response, the major portion happens in the first quarter ahead. While, the differential interest rate response is longer, lasting more than 1 year. This temporal difference in impact suggests that the waste of the autonomy of monetary policy is longer than the instability of the exchange rate. In the short run, applying CC may give the monetary ability to adapt the local interest rate, reducing the vulnerability to higher instability of the exchange rate related to the occurrence of intensive short-term flows generated by United States monetary policy variation.

The constraints of choice of economic policies in a context of free movement of capital can be circumvented following an accumulation of international reserves. In the 2000s, several EEs sought an optimal combination aimed at safeguarding an autonomous monetary policy, stabilizing the exchange rate and liberalizing the capital account via an accumulation of reserves (Bianchi et al., Citation2018). The results show positive and significant coefficients of “ka”, “kaopen” and “kai” to explain the changes in international reserves, only the coefficient of controls on outflows (“kao” index) is insignificant (Table ).

These reserves made it possible to correct the impossibility recourse to certain macroeconomic policies. Our results confirm this positive effect of reserves on monetary policy and on exchange rate policy, the coefficient of the variable “ir” is positive and significant in the equations explaining the differential interest rate and the exchange rate fluctuation.

The multilateral impacts of CC policies are important for many causes. First, CC applied by the country receiving international flows may motivate flows to reach other recipient economies that do not apply such controls and aggravate their local financial instability. Second, CC may obstruct foreign adjustment, for example, when controls on capital inflow are utilized to maintain a certain value of a currency. The cross-sectional equivalence of restrictions on capital flows is detected by the fixed effects of each EE and, to a limited degree, by the displaying declarations and changes related to the international investment position of the country.

We find proof that a net strict of inflow controls in the EEs (kai index) produces effective spillovers to other economies starting by driving these inflows into those economies and by causing tensions on their exchange rate. The short-term interest rates of these countries will fall as a response to discourage these inflows. These reactions are short term and are difficult to detect statistically, the shock and the response to this shock happen in the same trimester. Our results (Tables and ) show a positive and significant coefficient of “kai” in the equation of “spill”, besides, the Chinn and Ito index “kaopen” is also positive and significant. These findings are in line with the literature evidence. The other indexes of capital controls on outflows and gross flows “kao” and “ka” are insignificant.

As a response to these high inflows and oppose their negative effects on the domestic currency, the local policymakers react by strengthening inflow controls. This policy response is efficient and conducts to a turnaround of the capital inflow in the next quarter, which causes a fall which covers massive inflows of the previous period.

Our results that CC cause spillovers to strategy in other economies are approved by theory, but this study is among the earliest to discover empirical proof for these spillovers. Lu et al. (Citation2017) examine the political response of one country following the intensive application of CC by another country. These capital controls provoked a negative externality and induced a similar reaction in the country which consequently received massive inflows of capital also leading them to practice capital controls. Nevertheless, Lu et al. (Citation2017) don’t verify empirically this spillover effect.

The evidence for this spillover became clearer after the 2008 crisis, it was found that capital controls instituted by one country caused an appreciation of the currencies of other countries and a massive inflow of capital to these countries. During the following periods, these effects will gradually decrease and will end with the introduction of capital controls by the other countries, there will be a fall in inflows and an increase in the short-term interest rate differential.

5. Conclusions

The study examined the domestic and international impacts of CC. Domestically, restrictions on capital flows allow for more monetary policy autonomy, more exchange rate stability, and, unpredictably, have no impact on international reserves accumulation. The study suggests a joint use of these policies, particularly, CC and the reserves policy. The use of CC as a restrictive policy has considerable advantages in supporting other economic policies and achieving an optimal policy mix. Internationally, multilateral effects are highlighted through spillover effects. The results highlight the requirement of policy coordination across countries to deal with capital flows reversal.

The evidence shows that EEs tightened prudential policies and inflow controls as inflows surged, and relaxed them when flows receded. With controls on capital outflows, EEs can relax these restrictions to lower the volume of net flows, reducing overheating and currency appreciation pressures. The EE policymakers responded to capital inflows through various tools, they have potentially five tools to manage capital flows and mitigate any untoward consequences: monetary (interest rate) policy, fiscal policy, exchange rate policy, prudential measures, and capital controls. In deploying these tools, there is a logical reasoning (or natural mapping) between instruments and risks. Monetary and fiscal policies can help address the inflation and economic overheating concerns raised by capital inflows. When the currency is not undervalued, foreign exchange intervention can be used to limit currency appreciation that threatens competitiveness. Prudential measures can be applied to curb excessive credit growth and related financial stability risks. Capital inflow controls, if applied sufficiently broadly, can buttress these other policies by limiting the volume of capital inflows in the first place, or more targeted controls can be used to address balance sheet vulnerabilities such as currency and maturity mismatches.

Policymakers in EEs have responded to capital flows by deploying a combination of instruments. Central banks used the policy interest rate to address inflation and overheating concerns and intervened heavily in the face of capital inflows. Beyond these policies, EEs tightened macroprudential measures, capital controls, and currency-based measures that affect capital inflows, while countries with relatively closed capital accounts tended to relax restrictions on capital outflows. Moreover, there has been some correspondence between the tool deployed and the nature of the risk—thus, central banks intervened when the real exchange rate was appreciating, tightened monetary policy when the economy was overheating, and used macroprudential tools when financial-stability concerns dominated. Inflow controls were typically used when there were many, aggravated, risks. The orthodox policy prescription to tighten fiscal policy in the face of capital inflows was the least used instrument in practice, with no strong evidence that EEs systematically tightened fiscal policy in response to large capital flows.

Several shortcomings can be identified in this analysis; in particular, the capital control indexes used. Other studies may use other indexes and may obtain different results. This is a common problem in the majority of capital control studies. Similarly, the choice of differential interest rate as an indicator of monetary policy autonomy is problematic. Although the differential in domestic and foreign interest rates is often seen as a proxy for the independence of the monetary policy, it is subject to debate.

Our study was conducted within the framework of a relatively simple empirical model; in reality, however, the connections between restrictive policies and other macroeconomic policies are complex. It is very difficult to find an optimal policy mix that combines monetary, exchange rate, international reserves, and CC policies; this topic is left for future research. To a certain extent, our analysis can be considered as an investigation of CC impacts that consider other macroeconomics policies, yet we admit that a more developed model would be essential to set a combination of multiple macroeconomic policies. Such a model would need to define robust proxies for monetary policy autonomy, exchange rate stability, and particularly for robustness check with more robust CC indexes.

Disclosure statement

No conflict of interest to report.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Chokri Zehri

Chokri Zehri is assistant professor of economics at Prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz University in Saudi Arabia. A Tunisian citizen, he taught at Gabes University and al-baha international college of sciences before coming to Prince Sattam University in 2019. Zehri received his B.Ec. from the Institute of Higher Commercial Studies of Carthage-Tunis in 2001 and completed his master and Ph.D. in Economics at Aix-Marseille II University – France in 2007.

Zehri’s research interests include the macroeconomics policies; financial crises; capital account liberalization, capital controls; income inequality; external debts; and econometric methods for program and policy evaluation. He published many papers in these areas and got several awards for outstanding publications.

Notes

1. Brazil, Chile, China, Colombia, Czech Republic, Egypt, Greece, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, Pakistan, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Qatar, Russia, South Africa, Taiwan, Thailand, Turkey, and United Arab Emirates. The list is established according to the Morgan Stanley Capital International Emerging Market Index.

References

- Alfaro, L., Chari, A., & Kanczuk, F. (2017). The real effects of capital controls: Firm-level evidence from a policy experiment. Journal of International Economics, 108, 191–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2017.06.004

- Bayoumi, T., Gagnon, J., & Saborowski, C. (2015). Official financial flows, capital mobility, and global imbalances. Journal of International Money and Finance, 52, 146–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jimonfin.2014.11.017

- Benigno, G., Chen, H., Otrok, C., Rebucci, A., & Young, E. R. (2013). Financial crises and macro-prudential policies. Journal of International Economics, 89(2), 453–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2012.06.002

- Benigno, G., Chen, H., Otrok, C., Rebucci, A., & Young, E. R. (2016). Optimal capital controls and real exchange rate policies: A pecuniary externality perspective. Journal of Monetary Economics, 84, 147–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2016.10.004

- Bianchi, J., Hatchondo, J. C., & Martinez, L. (2018). International reserves and rollover risk. American Economic Review, 108(9), 2629–2670. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20140443

- Bianchi, J., & Mendoza, M. E. G. (2011). Overborrowing, financial crises and ‘macro-prudential’ policy? (No. 11-24). International Monetary Fund. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20140443

- Binici, M., Hutchison, M., & Schindler, M. (2010). Controlling capital? Legal restrictions and the asset composition of international financial flows. Journal of International Money and Finance, 29(4), 666–684.

- Chamon, M., & Garcia, M. (2016). Capital controls in Brazil: Effective? Journal of International Money and Finance, 61, 163–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jimonfin.2015.08.008

- Chinn, M. D., & Ito, H. (2008). A new measure of financial openness. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis, 10(3), 309–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876980802231123

- Devereux, M. B., Young, E. R., & Yu, C. (2017). Capital controls, monetary policy, and sudden stops. https://doi.org/10.3386/w21791

- Devereux, M. B., Young, E. R., & Yu, C. (2019). Capital controls and monetary policy in sudden-stop economies. Journal of Monetary Economics, 103, 52–74.

- Edison, H. J., & Warnock, F. E. (2003). A simple measure of the intensity of capital controls. Journal of Empirical Finance, 10(1–2), 81–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0927-5398(02)00055-5

- Eichengreen, B., & Rose, A. (2014). Capital controls in the 21st century. Journal of International Money and Finance, 48, 1–16.

- Farhi, E., & Werning, I. (2014). Dilemma not trilemma? Capital controls and exchange rates with volatile capital flows. IMF Economic Review, 62(4), 569–605. https://doi.org/10.1057/imfer.2014.25

- Fernández, A., Klein, M. W., Rebucci, A., Schindler, M., & Uribe, M. (2016). Capital control measures: A new dataset. IMF Economic Review, 64(3), 548–574. https://doi.org/10.1057/imfer.2016.11

- Fernández, A., Rebucci, A., & Uribe, M. (2015). Are capital controls countercyclical? Journal of Monetary Economics, 76, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2015.07.001

- Forbes, K., Fratzscher, M., & Straub, R. (2015). Capital-flow management measures: What are they good for? Journal of International Economics, 96, S76–S97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2014.11.004

- Forbes, K., Reinhardt, D., & Wieladek, T. (2017). The spillovers, interactions, and (un) intended consequences of monetary and regulatory policies. Journal of Monetary Economics, 85, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2016.10.008

- Furceri, D., & Loungani, P. (2018). The distributional effects of capital account liberalization. Journal of Development Economics, 130, 127–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2017.09.007

- Ito, H., McCauley, R. N., & Chan, T. (2015). Currency composition of reserves, trade invoicing and currency movements. Emerging Markets Review, 25(58), 16–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ememar.2015.11.001

- Jeanne, O. (2016). The macroprudential role of international reserves. American Economic Review, 106(5), 570–573. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.p20161013

- Kim, S., & Yang, D. Y. (2012). International monetary transmission in East Asia: Floaters, non-floaters, and capital controls. Japan and the World Economy, 24(4), 305–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japwor.2012.05.003

- Klein, M. W., & Shambaugh, J. C. (2015). Rounding the corners of the policy trilemma: Sources of monetary policy autonomy. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 7(4), 33–66. https://doi.org/10.1257/mac.20130237

- Korinek, A. (2011). The new economics of prudential capital controls: A research agenda. IMF Economic Review, 59(3), 523–561. https://doi.org/10.1057/imfer.2011.19

- Korinek, A. (2018). Regulating capital flows to emerging markets: An externality view. Journal of International Economics, 111, 61–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2017.12.005

- Lambert, F. J., Ramos-Tallada, J., & Rebillard, C. (2011). Capital controls and spillover effects: Evidence from Latin-American countries. SSRN Electronic Journal, 4(121), 45–52. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1980091

- Liu, Z., & Spiegel, M. M. (2015). Optimal monetary policy and capital account restrictions in a small open economy. IMF Economic Review, 63(2), 298–324. https://doi.org/10.1057/imfer.2015.8

- Lu, Y., Tao, Z., & Zhu, L. (2017). Identifying FDI spillovers. Journal of International Economics, 107(86), 75–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2017.01.006

- Magud, N. E., Reinhart, C. M., & Rogoff, K. S. (2018). Capital controls: Myth and reality-a portfolio balance approach. Annals of Economics and Finance, 19(1), 1–47. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1773692

- Ocampo, J. A., Spiegel, S., & Stiglitz, J. E. (2008). Capital market liberalization and development. Capital Market Liberalization and Development, 3(78), 1–47. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199230587.003.0001

- Pasricha, G. K., Falagiarda, M., Bijsterbosch, M., & Aizenman, J. (2018). Domestic and multilateral effects of capital controls in emerging markets. Journal of International Economics, 115, 48–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jinteco.2018.08.005

- Passari, E., & Rey, H. (2015). Financial flows and the international monetary system. The Economic Journal, 125(584), 675–698. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12268

- Qureshi, M. S., Ostry, J. D., Ghosh, A. R., & Chamon, M. (2011). Managing capital inflows: The role of capital controls and prudential policies (No. w17363). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w17363

- Rebucci, A., & Ma, C., (2019). Capital controls: A survey of the new literature (No. w26558). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w26558

- Rey, H. (2015). Dilemma not trilemma: The global financial cycle and monetary policy independence (No. w21162). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w21162

- Zehri, C. (2020). Policies for managing sudden stops. Zbornik Radova Ekonomskog Fakulteta U Rijeci: Casopis Za Ekonomsku Teoriju I Praksu, 38(1), 9–33. https://doi.org/10.18045/zbefri