?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This paper examines bank concentration, competition, and financial stability nexus across five emerging countries (Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda and Burundi) within the East African Community (EAC). The methodological approach applied provides a critical and original contribution to the existing literature by testing the various theories explaining the relationships between bank concentration, competition, and stability. A two-step system Generalised Methods of Moments (GMM) is employed on a sample of 149 banks with 1,805 annual observations over the period 2001–2018. The findings reveal that high concentration and low competition lead to more financial stability and less probability of bank default risk. In addition, a non-linear relationship between competition and stability is not observed, revealing that greater competition undermines bank stability and makes banks more vulnerable to default risk. The findings thus lend to support the concentration-stability hypothesis that greater market power leads to more bank stability even after controlling for bank-specific, industry, and macroeconomic variables. The findings provide a significant policy contribution on the trade-off between bank concentration and competition, and the evaluation of financial stability.

1. Introduction

Over the last two decades, the banking sector has undergone through voluminous restructuring and consolidation phases globally. Prior to the global financial crisis (GFC) in 2007–2009, various reforms and policies such as liberalisation of interest rates and deregulation were pursued to increase competition (Demirgüç-Kunt & Detragiache, Citation2005). However, the advent of the global financial crisis is said to have been exacerbated by excessive competition, and various regulatory reforms geared towards enhancing financial stability have thereafter been introduced (Barth et al., Citation2013). This has indeed resulted to increased market power leading to high levels of bank concentration (Vives, Citation2010; 2019). A fundamental concern arises as to whether the banking system should be more competitive or concentrated on maintaining financial stability.

Existing theoretical and empirical studies on bank concentration, competition, and financial stability nexus remain complex and a subject of interest to the policymakers and regulators (Allen & Gale, Citation2004; Alvi et al., Citation2021; Beck et al., Citation2006; Boyd et al., Citation2006; Davis et al., Citation2020; Fu et al., Citation2014; Goetz, Citation2018; Saha & Dutta, Citation2020; Schaeck & Cihák, Citation2014). Two strands of theories have been propounded to explain the bank behavior, which has generated mixed and inconclusive findings. The concentration-stability theory argues that market power enables banks to boost their profitability levels by charging high prices, thus creating a buffer that cushions the banks against any adverse shocks (Ali et al., Citation2018; Beck et al., Citation2006; Danisman & Demirel, Citation2019; Turk-Ariss, Citation2010). On the other hand, the concentration-instability theory presents a destabilizing effect of bank concentration (Boyd & De Nicolò, Citation2005; Uhde & Heimeshoff, Citation2009). Mishkin (Citation1999) argues that the government’s implicit or explicit assurance of big banks to be rescued in case of bankruptcy increases their risk-taking behavior hence escalating the systemic risk.Footnote1

Furthermore, the studies differ in terms of measures employed to estimate bank concentration and competition, which are assumed to be inversely related hence requiring a further investigation. For instance, Schaeck et al. (Citation2009) find that concentration and competition may not be related and capture different characteristics in the banking system. Similarly, Claessens and Laeven (Citation2004) establish that concentration is a poor proxy of competition. In addition, Bikker (Citation2004) argues that concentration may be an imperfect measurement of competition since it uses concentration ratios which tend to exaggerate the concentration in small countries, and it is unreliable if the number of banks is small. In contrast, Boyd and De Nicolò (Citation2005) contend that concentration can be a good proxy for competition. Despite the demonstrated differences on the measures, extremely few studies have explored the joint effect of market concentration and competition on financial stability. Moreover, previous studies have focused more on developed economies compared to developing economies and especially Africa to the best of our knowledge. Against this backdrop, the paper explores the nexus between bank concentration, competition, and financial stability within the East African Community (EAC).Footnote2 The choice of EAC countries is pegged to the fact that they are developing countries and are currently involved with financial integration initiatives geared towards a more consolidated financial system in the region (EAC, Citation2019). The ongoing reforms in the EAC provide a fertile ground for the analysis of market structure (Bending et al., Citation2015; Davoodi et al., Citation2013).

The paper contributes to the literature in several respects. First, both structural and non-structural measures are simultaneously incorporated to estimate whether bank concentration and competition are significantly related or not. This action is critical as it sheds more light on the mixed and inconclusive findings established by existing studies, given that they use different measures of concentration and competition (Berger et al., Citation2009; Schaeck et al., Citation2009). Second, the expansion of the financial system and the presence of regional banks within the EAC has increased the level of interconnectedness among the partner countries (EAC, Citation2019). The investigation of the financial stability of these financial systems is overly critical because any shock within the banks might catapult tremendous effects on the entire EAC region. Finally, to the best of our knowledge, there is extremely few or none of the academic research that has explored the dynamics of bank concentration and competition on financial stability within the East African Community.

In a preview, the findings reveal that increased bank concentration and low competition lead to more financial stability and less probability of bank default risk. A non-linear relationship between competition and stability (measured by the quadratic term of the Lerner index) is not observed to exist. Instead, it reveals that greater competition undermines bank stability and makes banks more vulnerable to default risk. Thus, the findings support the concentration-stability hypothesis that greater market power leads to more stability after controlling for bank, industry, and macroeconomic variables. The findings provide a significant policy contribution on the trade-off between bank concentration and competition, and the evaluation of financial stability.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents theoretical and empirical review, while Section 3 describes the model specification, variable definitions, and data used. Section 4 presents descriptive and empirical results, while Section 5 concludes the paper with policy implications.

2. Literature review

The relationship between bank concentration, competition, and financial stability remains a puzzle in theoretical literature, and two competing channels/views have been established to demystify the existing debate. The traditional concentration-stability theory as argued by Smith (Citation1984) and Keeley (Citation1990) postulates that high concentration leads to more stability. This is because high market power allows firms to protect their franchise value by accumulating large capital buffers and engaging in low-risk investments, thus cushioning themselves against any future uncertainties (Matutes & Vives, Citation2000). In addition, market power enables banks to boost profitability levels by charging high prices, thus creating a buffer that cushions them against any adverse shocks in the market. Allen and Gale (Citation2004), Beck et al. (Citation2006), and Berger et al. (Citation2009) argue that more concentrated banks are less susceptible to experience crises.

On the other hand, the concentration-fragility theory presents that more concentrated firms are unstable. According to Mishkin (Citation1999), concentrated banking systems may engage in more risk-taking behaviours on the notion of too-big-to-fail due to the explicit or implicit assurance by the government safety net. This is because when there are few banks in a concentrated banking system, the government is more concerned about any risks that might arise on these few banks. Caminal and Matutes (Citation2002) argue that less competitive (concentrated) banks can originate risky loans that might escalate future problems in the entire banking system. The risky loans may originate if higher interest rates are charged to customers making it harder to pay thus breeding moral hazard (risk shifting) and adverse selection (funding worse projects) problems (Boyd & De Nicolò, Citation2005). However, Berger et al. (Citation2009) observe that in as much as market power may increase the loan risk portfolios, the overall risks may not be as much if banks can protect their franchise value either by increasing capital buffers or engaging in risk mitigation techniques.

Empirical evidence regarding the concentration-stability and concentration-fragility theories remain mixed and inconclusive (J. A. Bikker & Haaf, Citation2002; Beck et al., Citation2005, Citation2006; Danisman & Demirel, Citation2019; Davis et al., Citation2020; Fu et al., Citation2014; Goetz, Citation2018; Saif-Alyousfi et al., Citation2020; Schaeck & Cihák, Citation2014; Turk-Ariss, Citation2010). Both cross-country and country-specific studies have been explored extensively in the context of developed economies while hardly a few studies have been explored in the context of developing economies. In addition, most of the studies have employed national measures of bank concentration and competition compared to bank-level measures. With regard to cross-country studies in developed economies, Beck et al. (Citation2006) carry out a study using 69 countries from 1980–1997 to establish the implications of bank concentration and competition on banking systemic crisis. The findings reveal that banking systemic crises (measured by a dummy variable) are less in the countries with a more concentrated banking system (measured by a concentration index) after controlling for macroeconomic, institutional, and regulatory factors. In contrast, Uhde and Heimeshoff (Citation2009) find that bank market concentration has a significant negative relationship with bank’s financial soundness in Europe.

Furthermore, Schaeck et al. (Citation2009) carry out a study to establish whether competitive banks are more stable than non-competitive banks in 45 countries. Using 27,585 observations from 1980–2005, the study finds out that competition (measured by H-Statistics) reduces the possibility of a crisis (measured by a crisis dummy) and prolongs the time to a crisis. Interestingly, the findings also reveal that concentration (measured by concentration index) reduces the likelihood of a crisis (measured by a crisis dummy) and prolongs the time to a crisis. The findings imply that concentration and competition may not be used as a proxy for each other since they capture different aspects as also argued by (Claessens & Laeven, Citation2004). On the contrary, Liu et al. (Citation2013) observe a non-linear relationship between bank competition and stability in the European countries. The findings reveal that too much or too little competition leads to instability, but moderate competition leads to higher stability.

Additionally, Fu et al. (Citation2014) explores the effect of bank competition and concentration on financial stability in the Asian Pacific countries and finds that bank concentration (as measured by concentration ratio) leads to financial fragility (as measured by the probability of bankruptcy and Z-Score). Using a sample of 4,069 bank observations in 14 Asian Pacific economies from 2003 to 2010, the study also finds that low market power (high competition) (as measured by Lerner and E-Lerner Index) also leads to bank risk exposure. The findings are somewhat interesting and contrasting since they imply that concentration-stability and concentration-fragility hypothesis can apply simultaneously within those economies raising concerns on the measurement of bank concentration and competition.

Schaeck and Cihák (Citation2014) use a different measure of bank competition (Boone [2008] Indicator) to examine the relationship between competition, efficiency and stability and the study finds that increased competition leads to more bank stability. The study observes that efficiency acts as a conduit through which competition influences stability (measured by Z-score). Using 17,965 observations in 3,325 European banks from 1995 to 2005, the study also establishes that healthy banks benefit more from competition-stability effect compared to the fragile banks. However, a recent study by Danisman and Demirel (Citation2019) contrasts the findings by establishing that a competitive banking environment leads to more bank risks while carrying out a study in 25 developed economies.

Focusing on the country-specific studies in developed economies, Boyd et al. (Citation2006) uses a cross-sectional sample of 2,500 US banks in 2003 and a panel data of 2,600 banks from 1993 to 2004 in 134 non-industrialised countries to establish the effect of bank concentration on bank risk taking. The study finds a significant positive relationship between concentration and probability of a bank failure thus supporting concentration-fragility hypothesis. The findings are consistent with Goetz (Citation2018) who carry out a study on the effect of competition on bank stability in the US using a sample of 102,819 bank observations from 1976 to 2006. The study specifically examines how interstate banking deregulation influenced the entry of other banks in the region and the effect it had on bank stability. The findings reveal that the removal of entry barriers (competitiveness) increased the level of bank stability significantly.

Other studies like Turk-Ariss (Citation2010) and Ali et al. (Citation2018) have explored the relationship between bank concentration and financial stability in both developed and developing countries. For instance, Turk-Ariss (Citation2010) use a sample of 4,670 observations of 821 banks in developing economies from 1999–2005 to establish the implications of market power on bank efficiency and financial stability. The study find that concentrated banks exhibit more profit efficiency despite enduring some cost inefficiencies brought about by the notion of “too big to fail” hence exposing themselves to more inherent risks. With regard to financial stability, concentrated banks prove to be more stable thus supporting the traditional concentration-stability hypothesis. In addition, Ali et al. (Citation2018) use a sample of 156 countries in both developed and developing economies for a period between 1981–2011 to establish the direct and indirect effect of bank concentration on financial stability. The findings reveal that there is no direct effect of bank concentration on financial stability but notes that bank concentration has an indirect positive effect on financial stability through profitability channel and indirect negative impact on interest rate channel. The findings are however contrasted by Saha and Dutta (Citation2020) who find that competition enhances stability while examining 92 countries in both developed and developing countries.

Albeit the extensive literature, few studies have been explored with respect to the developing economies, and especially Africa (Akande et al., Citation2018; Amidu & Wolfe, Citation2013; Kouki & Al-Nasser, Citation2017; Saif-Alyousfi et al., Citation2020). A study by Amidu and Wolfe (Citation2013) explores the relationship between competition, diversification and stability and finds that competition increases bank stability. In contrast, Kouki and Al-Nasser (Citation2017) find that market power leads to efficiency and stability. Similarly, Akande et al. (Citation2018) find a positive relationship between bank risk taking and competition in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). From the empirical examination, it can be deduced that different studies differ in terms of sample employed, period of study, regional context, methodology and measures of concentration and competition employed. This study attempts to fill such gaps by investigating the largely underexplored EAC banking industry which provide fertile grounds for the analysis of market structure due to the ongoing reforms (EAC, Citation2019).

3. Methodology

3.1. Model specification

Consistent with Liu et al. (Citation2013) and Mirzaei et al. (Citation2013), the paper explores the dynamics of bank concentration and competition on financial stability using the following general dynamic panel econometric model on bank-level data:

Where: refers to the dependent variable (financial stability) and

is one period lag of financial stability,

represents the bank concentration or competition variable,

is a vector of bank specific variables,

is a vector of industry/institutional while

is a vector of country/macroeconomic variables.

is the error term where;

is unobserved individual specific effect,

is the unobserved time effects, and

is the normal stochastic disturbance term. The regression model is a two-way error component where:

and

. Subscript

denotes ith bank,

denotes country and

denotes the time period.

To examine the possibility of a non-linear relationship between competition and financial stability (Berger et al., Citation2009), a quadratic term for competition has been included as specified in the following model:

Where: represents competition variable (Lerner) while

denotes the quadratic term of competition variable (Lerner2). The analogous variables remain the same as specified in Equationequation 1

(1)

(1) above. presents the list of variables, definitions and sources.

Table 1. Definition of variables and sources

The paper employs a two-step system Generalised Methods of Moments (GMM) as proposed by (Blundell & Bond, Citation1998). Unlike fixed or random effects models which may be biased and inconsistent, GMM addresses problems of endogeneity, unobserved heterogeneity, correlation between the regressors and the lagged dependent variable being included as a covariate (Efthyvoulou & Yildirim, Citation2014). GMM is argued to be effective in controlling for simultaneity bias and reverse causality which may exist between the key variables of interest i.e. financial stability, concentration and competition. The consistency of system GMM depends on two assumptions; that there is no second-order serial correlation and the validity of instruments used. Two tests are therefore carried out; the Arellano-Bond tests of second-order serial autocorrelation of the differenced residuals, and the Hansen test for over-identifying restrictions. EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) and (Equation2

(2)

(2) ) are therefore estimated using the two-step system GMM estimator with xtabond2 command (Roodman, Citation2009) with Windmeijer (Citation2005) corrected standard errors, small sample and instrument collapse option.

3.2. Financial stability

Two risk indicators are used as a proxy to measure financial stability. To start with, Z-Score is employed as a measure of bank overall risk. This is because Z-Score combines profitability measure (ROA), bank risk denoted by standard deviation of ROA and indicators of bank safety and soundness as captured by equity to asset ratio (Kasman & Kasman, Citation2015; Liu et al., Citation2013). Z-Score is a bank level measure and is used as an inverse proxy of firm’s probability to failure. It is computed by the addition of average return on assets and equity over total assets divided by standard deviation of return on assets as shown below.

Where: represents return on assets for bank

at time

,

represents average equity to total assets of bank

at time

and

represents standard deviation of return on assets for bank

at time

. A higher Z-Score implies less risk and more stability.

For robustness purposes, and consistent with Turk-Ariss (Citation2010) and Amidu and Wolfe (Citation2013), Risk Adjusted Return on Assets (RAROA) is also employed as a measure of financial stability. It is calculated as:

Where ROA is the ratio of income before tax over total assets. A higher value of RAROA imply more bank stability.

3.3. Bank concentration and competition

The measures of bank concentration and competition have been used as a proxy for each other and various studies have established inconsistent and inconclusive findings depending on the measure employed (Beck et al., Citation2006; Schaeck et al., Citation2009). This paper simultaneously incorporates both structural (market structure conduct) and non-structural (bank conduct) measures to establish whether bank concentration and competition are significantly related or not.

3.3.1. Bank concentration

Three-bank concentration ratio (CR3) and Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) are employed to measure bank concentration. CR3 is a country-level measure that indicates the proportion of assets held by 3 largest banks in a country. The higher the concentration ratio, the higher the bank concentration and market power. The challenge with concentration ratio is that it only captures the market share of 3 largest banks and ignores all the other small banks (J. Bikker & Haaf, Citation2002). It takes the following form:

Where: is the 3-bank concentration ratio and

is the market share of the 3-largest banks.

Unlike CR3 which accounts for market share held by the 3 largest banks only, HHI is calculated by summing the squared market shares of all banks in the market. It therefore ranges between zero and one. If HHI is zero or closer to zero, the market is perceived to be highly competitive while if HHI is one or closer to one, the market is perceived to be oligopolistic and a monopoly if one. HHI is computed using the following formula:

Where: is the market share of bank i at time t and n is the number of firms in the market. According to J. Bikker and Haaf (Citation2002), HHI below 0.10 is considered as lowly concentrated, HHI between 0.1 and 0.18 is considered as moderately concentrated while HHI above 0.18 is considered as highly concentrated.

3.3.2. Competition

Conventional Lerner index is used as the non-structural measure to estimate the level of bank competition. The Lerner index captures the mark-up of price over the marginal cost and therefore it estimates the degree of firm’s market power. It is computed as the difference between price and marginal cost divided by price as shown below:

Where: is the price of the banking output,

is the marginal cost,

and

represent specific bank at a specific year. Lerner index takes the values between 0 and 1 whereby, 0 is the minimum and 1 is the maximum value. When

= 0, it implies that there is a perfect competition and when

= 1, it implies there is a monopoly. Therefore, as the Lerner index increases (the difference between P and MC increases) it implies more pricing power by the respective firm and when P =MC, Lerner index = 0 implying that there is no market power (Turk-Ariss, Citation2010).

is derived using the following translog cost function:

Where: represents bank total cost computed as total expenses for bank

at time

;

is proxy for bank output or total assets; and

represents the three input prices (Berger et al., Citation2009; Liu et al., Citation2013; Turk-Ariss, Citation2010).

,

and

represents the input price of funding (computed as interest expenses to total funding/deposits), price of capital (computed as non-interest expenses to fixed assets) and price of labour (computed as personal expenses to total assets) respectively. Equation (8) is estimated using maximum likelihood techniques for the whole panel of sampled banks within the five countries. The clustered robust standard errors by banks are used to estimate the respective test statistics. Lastly, marginal costs

is then estimated by taking the first derivative with respect to output for each bank as follows:

3.4. Control variables

Consistent with Turk-Ariss (Citation2010), Fu et al. (Citation2014), and Goetz (Citation2018) a variety of bank specific variables are included in the paper. They include: Bank size measured as natural log of total assets to control for bank size effects. A positive relationship of bank size and financial stability imply the benefits derived from the economies of scale (Mirzaei et al., Citation2013). However, in the event of explicit or implicit too-big-to-fail government safety net policies to large banks, managers may tend to take more risks because of the assured protection (Demirgüç-kunt & Huizinga, Citation2013). Thus, the relationship between size and stability may be unclear. Loans/Assets measured as ratio of loans to total assets indicates the intensive and extensive ability of banks to offer loans. Diversification (Non-interest income) measured by total non-interest income over total assets and a positive value indicates increased stability. Listed (public banks) measured by a dummy variable of 1 if listed, and otherwise 0. Listed banks are assumed to more stable than non-listed banks. Foreign owned banks measured by a dummy variable of 1 if 50% of shares is owned by foreigners in each year, and otherwise 0. Government owned banks measured by a dummy variable of 1 if 50% is owned by government, and otherwise 0.

Financial structure variables include: Bank sector development (BSD) measured as the ratio of banking sector assets to GDP. BSD refers to the financial resources provided to all the economic sectors with an exception of government sector. A higher ratio is an indicator of increased financial deepening leading to stability of banks (Goetz, Citation2018: Mirzaei et al., Citation2013). Stock market development (SMD) is measured as the total value of shares traded over average market capitalization in the period. A higher ratio implies an efficient capital market where banks can get perfect information about companies thus reducing moral hazard and adverse selection risks (Mirzaei et al., Citation2013). Therefore, a higher ratio shall connote more bank stability.

According to Beck et al. (Citation2006) and IJtsma et al. (Citation2017), country specific factors have been included to capture the macroeconomic developments that might affect the quality of bank assets. They include: GDP Growth measured as a rate of growth of real GDP to capture the development level, and Inflation rate measured as a rate of change of GDP deflator. Real interest rate measured as a nominal interest rate minus rate of inflation is included to measure bank’s cost of funds which may increase the default rate if interest rates are high thus affecting bank stability. 1 presents the list of variables, definitions and sources.

3.5. Data

The sample data obtained is for the East African Community (EAC) banking industry. EAC is comprised of six countries, namely: Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi and South Sudan. However, South Sudan is excluded from the sample countries due constraints of data availability, and also, recently joined the EAC bloc in 2016 thus remaining with five countries. Both micro bank-level and macro country-level data is employed. The bank-level data is obtained from Fitch Connect database while country-level data is obtained from World Bank Development Indicators (WDI). The data is reported in US dollars and in constant prices for accounting uniformity. A selection criterion is applied to identify the banks considered in the study. Firstly, the banks must have operated for more than three years for consistency purposes, and the data on the main variables (concentration, competition and stability) must be available. Secondly, for the case of mergers and acquisitions, the target and acquiring bank are treated as separate unless unconsolidated data for the two banks is not available. Lastly, to reduce aggregation bias, unconsolidated financial statements are used since the focus of the study is on bank intermediation.

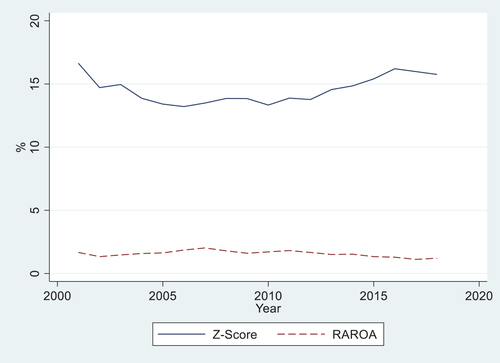

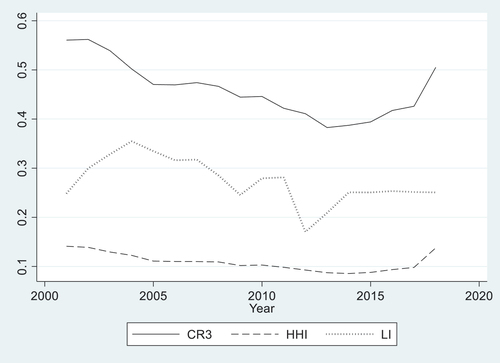

The collected data is carefully verified with respective central banks for each country while removing any missing and suspicious negative or zero values. The final variables are winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles to control for extreme values and unobservable input errors. Additionally, to mitigate the impact of extreme observations on regression coefficients for Lerner index estimation, model variable values falling more than nine standard deviations away from the sample mean are deleted. The above procedure yields a final sample of unbalanced panel dataset of 1,805 bank year observations for 149 banks over the period 2001–2018. Table and figure presents the evolution the evolution of financial stability and bank market power while Table presents descriptive statistics for all the variables employed in the study. The figures appear plausible and consistent with other reported previous studies. Table presents pairwise correlation coefficients and statistical significance for the variables and the magnitude is not too high to cause the problem of multicollinearity.

Table 2. Mean values of financial stability and market structure variables across the sample countries

Table 3. Descriptive statistics for all the variables

Table 4. Pairwise correlations

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Preliminary results

2 and presents the mean values of the evolution of financial stability and market structure within the EAC banking industry over the period 2001–2018. Financial stability is measured by both Z-Score and Risk Adjusted Rate of Return on Assets (RAROA) while the market structure is measured using both structural (bank concentration) and non-structural (competition) measures. Bank concentration is measured by both three-bank concentration ratio (CR3) and Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) while competition is measured by Lerner Index (LI). As it can be observed in , Z-score and RAROA have steadily remained constant and stable over the period with an exception of some few volatilities. This can be explained by the fact that no major crisis or shocks were witnessed within the period under observation despite the continuous financial integration and liberalization initiatives within the region (EAC, Citation2011, Citation2019). While the Z-score remains almost constant, bank concentration levels (as shown in ) appear to be decreasing over the period as denoted by CR3 and HHI except from 2015 to 2018 when they start increasing. The decrease in bank concentration levels could be explained by increased relativity of bank efficiency, removal and abolition of trade tariffs which has made banks to open up and even engage in cross-border banking activities (Kodongo et al., Citation2015).

Additionally, EAC, comprise of developing countries which are characterized by underdeveloped capital markets and the banks are the main providers of credit to the entire economy thus attracting entry of more banks (Oduor et al., Citation2017). The Lerner index which measures the level of competition is observed (in ) to be decreasing at the beginning of the sample period; then it starts to increase again towards the end of the sample period. The Lerner index behaviour could suggest a non-linear relationship between financial stability and competition; although, it remains relatively high which implies low competition levels (Berger et al., Citation2009).

2 presents the mean values of the key variables for each country. In particular, Kenya appear to have the highest Z-score (16.41%) and the lowest concentration ratio (CR3 of 37% and HHI of 7%) value compared to the other countries thus making it to be more stable, less risky and more competitive. This could be due to the fact that Kenya has the most developed and largest financial system within the EAC region and this lends its banking system to be more competitive (Beck et al., Citation2010). 3 presents the descriptive statistics for bank, industry and country level variables employed in the study while 4 presents the correlational matrix. The correlation among most of the variables is statistically significant but the magnitude is not too high to cause the problem of multicollinearity.

4.2. Empirical findings

present the results of the effects and dynamics of bank concentration and competition on financial stability. Z-score and RAROA are used as dependent variables and proxy measures of financial stability in , respectively. In each table, measures of bank concentration (i.e., CR3 and HHI) and competition (i.e., Lerner index) are employed. The rationale for employing both structural and non-structural measures is to test whether the measures are significantly related or not. This is important because Claessens and Laeven (Citation2004) and Bikker (Citation2004) argue that concentration and competition may be poor proxies for each other. To account for endogeneity and bidirectional link among the explanatory variables, two-step System GMM is employed. The Arellano-Bond and Hansen/Sargan test are reported to confirm the absence of serial autocorrelation in the first-differenced residuals and the validity of the instruments used for System GMM specification respectively.Footnote3

Table 5. Effect of bank concentration and competition on financial stability (Z-score)

Table 6. Effect of bank concentration and competition on financial stability (Risk-Adjusted Return On Assets (RAROA))

5 shows that bank concentration measures (column 1 and 2) are positive and statistically significant with Z-score implying that increased bank concentration leads to more bank stability and less risk. The Lerner index (column 3) is also positive and statistically significant with Z-score implying that greater competition may undermine overall bank stability. The findings thus support traditional bank concentration-stability hypothesis that increased concentration may lead to more bank stability. The results are consistent with the findings of Turk-Ariss (Citation2010) and Danisman and Demirel (Citation2019) while they contrast the findings of Schaeck and Cihák (Citation2014) and Goetz (Citation2018). To explore whether bank concentration and competition may be used as a proxy for each other, columns 4 and 5 confirm their utility as proxies since they are all positive and significant, and this supports Boyd and De Nicolò (Citation2005) contention.

Following Berger et al. (Citation2009), Fu et al. (Citation2014), and Dutta and Saha (Citation2021a), the quadratic term of Lerner index in column 6 tests whether a non-linear relationship exists between competition and financial stability. Since the quadratic term is positive just like the Lerner index, it implies that greater competition may undermine the level of bank stability and increase the probability of default risk. Unlike the non-linear relationship observed by Liu et al. (Citation2013); Dutta and Saha (Citation2021a, Citation2021b), the results are consisted with the findings of Turk-Ariss (Citation2010). The inexistence of non-linear relationship could be explained by the overreliance of the bank based financial systems which are the main providers of credit to the entire economy due to the underdeveloped capital markets. These reduces the level of competition among the banks allowing them to enjoy market power privileges such as accumulating capital buffers (Oduor et al., Citation2017). The findings also reveal that size is positively and statistically related with overall bank stability. This implies that large banks with more asset base are more stable. Capitalisation is also positively and statistically significant with bank stability implying that banks with more capital base are more stable and less risky. The positive findings of high capital adequacy and size are consistent with previous studies such as Mirzaei et al. (Citation2013).

6 also examines the effect of bank concentration and competition on financial stability using RAROA as a proxy for bank stability. Both bank concentration (CR3 and HHI) and competition (Lerner index) are positive and statistically significant with bank stability (RAROA). This implies that increased concentration and market power leads to more stability and reduces bank insolvency risks. The quadratic term of Lerner index in column 6 is also positive suggesting that greater competition may undermine overall bank stability. Bank size and capitalisation have a positive significant relationship with bank stability implying that large and more capitalised banks are more stable. The findings further reveal that listed banks are more stable while the global financial crisis as denoted by a crisis dummy never affected the EAC banks in a negative manner.

4.3. Robustness checks

For further robustness checks, two alternative tests are conducted. First, different measures for bank concentration and competition are employed i.e. five-bank concentration ratio (CR5) and a separate country-specific bank-level Lerner index. The rationale is mainly to account for the potential differences in technology in each country within the EAC. As observed in , the dependent variable in column 1–4 is Z-score and the findings are positive and statistically significant implying that increased bank concentration and market power leads to more bank stability and less probability of default risk. Additionally, columns 5–8 which use ROROA as the dependent variable observe the same findings. The quadratic Lerner index term is also positive and statistically significant with bank stability implying that greater competition may undermine the level of bank stability and increase the probability of default risk. Size and capitalisation have a positive significant relationship with bank stability suggesting that large and well capitalised banks are more stable and less susceptible to default risk. Furthermore, listed banks seem to be more stable and this could be due to the advantages of listed banks being able to access capital easily and being under more stringent regulations. Lewbel (Citation2012, Citation2018) 2SLS method that uses heteroscedasticity in the data to generate internal instruments as an identification for the endogenous regressors is employed for further robustness tests. The results remain consistent with the main findings of the paper.Footnote4

Table 7. Robustness checks on the effect of bank concentration and competition on financial stability (CR5 and Country-specific bank-level Lerner index)

5. Conclusion

Owing to the mixed and inconclusive findings on the effects of market structure, this paper examines bank concentration, competition and financial stability nexus across five emerging countries (Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda & Burundi) within the EAC to provide some conclusion on the debate. EAC countries are currently involved with financial integration initiatives, geared towards a more consolidated financial system in the region. The expansion of financial system and presence of regional banks within the EAC have increased the level of interconnectedness among the partner countries. The stability of these financial systems is overly critical because any shock within one system can catapult tremendous effects to the entire EAC region. Using a two-step system GMM, a sample of 149 banks from 2001 to 2018 is employed generating unbalanced panel dataset of 1,805 bank year observations. Financial stability is measured using Z-score and Risk Adjusted Return on Assets (RAROA) while bank concentration is measured using three-bank concentration ratio and Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI). Competition is measured using Lerner index, thus the study provides both structural and non-structural measures of market structure.

The findings reveal that bank concentration has a positive significant relationship with financial stability implying that more concentration leads to more stability and reduced probability of default risk. Lerner index (inverse measure of competition) is observed to have a positive significant relationship with financial stability suggesting that greater competition impede stability and increases the probability of default risk. The quadratic term for Lerner index also reveals a positive significant relationship between market power and financial stability suggesting that a non-linear relationship does not exist within the EAC. While concentrated banks may have reduced banking risk due to the capital buffers, they might exercise their market powers by charging high prices to the customers. The findings are robust even with the use of bank, industry and macroeconomic variables. The positive significant effect of size and capitalization with financial stability imply that large and well capitalised banks are stable and less risky. Listed banks also seem to be more stable and this could be due to ease of access to capital by the listed banks and strict regulatory controls. Using the crisis dummy variable for global financial crisis in 2007–9, the findings suggest that the EAC banks were never affected by the crisis. In summary, the findings support the concentration-stability view that greater concentration and less competition increases stability of the financial system within the EAC.

The findings of this paper offer some important policy implications to policy makers. Firstly, a trade-off between bank concentration and competition should be maintained while evaluating financial stability as it is observed that greater concentration leads to more stability, and yet, large banks can still exercise market power and collude to charge higher interest rates. Secondly, capital adequacy and regulatory frameworks should be strengthened as well because capitalised banks appear to be more stable. Thirdly, banks should be encouraged to get listed on the capital markets as this enhances their capital access options with more regulatory conditions. Lastly, mergers and acquisitions of small and medium banks should be encouraged so as to realize a more consolidated financial system within the EAC. This will not only increase the stability of banks through size effects, but it will also open the sector to more cross-border banking operations which will accelerate the realization of a common monetary union which is one of the main EAC goals.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Moses Nyangu

Moses Nyangu is a PhD candidate in Development Finance at University of Stellenbosch Business School, in South Africa. He holds a Master of Commerce (Finance specialization) from Strathmore University and a Bachelor of Economics from Maseno University in Kenya. Moses’s research interest lies in the area of financial institutions and markets with application of Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) and Stochastic Frontier Analysis (SFA) on measurement of efficiency and productivity analysis. His current research investigates various issues in the East African Banking Sector including bank efficiency, concentration, competition and bank risk-taking behavior.

Nyankomo Marwa

Nyankomo Marwa is a senior lecturer in Development Finance and Econometrics at University of Stellenbosch Business School, South Africa. Also, Nyankomo holds visiting positions at the School of Management Sciences of the University of Quebec Montreal, DR J Herbert Smith Centre for Technology Management and Entrepreneurship at the University of New Brunswick in Canada. He has published research articles in international peer-reviewed journals in the areas of development finance, efficiency analysis, applied econometrics and agricultural economics. He holds PhD in Development Finance from University of Stellenbosch Business School and MSc Agricultural Economics from University of Nebraska, Lincoln, USA.

Ashenafi Fanta

Ashenafi Fanta is a senior lecturer of development finance at the University of Stellenbosch Business School. Previously, he worked as Data Analysis and Segmentation Expert at FinMark Trust where he was involved in developing segmentation models, developed a new financial indicator, provided advise on how the FinScope methodology can be improved or enhanced by comparing FinScope survey against Global Findex and other demand surveys. Dr Fanta’s research publications are in financial development, financial inclusion and corporate governance of financial institutions. He holds a doctoral degree in Social and Economic Sciences: Corporate Finance, from Johannes Kepler University of Linz, Austria.

Elinami J. Minja

Elinami J. Minja is a Senior Lecturer in Finance and Economics at the University of Dar es Salaam Business School. He holds a Ph.D. in Economics from Oklahoma State University – USA; a Masters of Business Administration (MBA) from /investments and corporate finance. With more than 20 years of experience in academics, he has done a number of researches, consultancies and published in his areas of specialty University of Nairobi, Kenya and a Bachelor of Commerce (Accounting) from University of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Dr. Minja’s special expertise and strengths are in financial markets and actively participates in conferences and workshops.

Notes

1. Boyd et al. (Citation2006) present that the effect of riskier portfolios is more than the revenues realized from the concentrated banking sectors. In addition, empirical evidence suggest that lack of competition leads to high concentration and increased market power which can hinder the level of bank efficiency and stability in an economy especially if some banks are too big to fail (Allen & Gale, Citation2004; Boyd & De Nicolò, Citation2005; Goetz, Citation2018; Ibrahim et al., Citation2019; Schaeck & Cihák, Citation2014). On the hand, Martinez-Miera and Repullo (Citation2010) and (Dutta & Saha, Citation2021b) observe a non-linear relationship between competition and stability.

2. While related studies such as Kouki and Al-Nasser (Citation2017), Oduor et al. (Citation2017), and Akande et al. (Citation2018) are focused in Africa, the current study considers one economic bloc (EAC) characterized by regional integration initiatives where the level of interconnectedness has increased and any bank shock might catapult tremendous effects to the entire region. In addition, both structural and non-structural measures are employed unlike the prior studies.

3. The Two-step system GMM is estimated in STATA-15 using the xtabond2 command (Roodman, Citation2009) and Windmeijer (Citation2005) corrected standard errors, small sample and instrument collapse options. To circumvent the effect of a large number of instruments which make the results of GMM misleading, we ensure the number of instruments do not exceed the number of groups and also use a subset of the instrument matrix available. Financial stability, bank concentration, competition, capitalisation, diversification, loans/assets, and bank size are treated as endogenous variables. These variables are instrumented with GMM-style instruments, i.e., the variables are lagged in levels. Financial structure and macroeconomic variables are treated as exogenous variables in ivstyle option of xtabond2.

4. The robustness results with regard to Lewbel (Citation2012, Citation2018) 2SLS method are not reported in the paper; however, they are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

- Akande, J. O., Kwenda, F., & Ehalaiye, D. (2018). Competition and commercial banks risk-taking: Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa region. Applied Economics, 50(44), 4774–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2018.1466995

- Ali, M. S. B., Intissar, T., & Zeitun, R. (2018). Banking concentration and financial stability. new evidence from developed and developing countries. Eastern Economic Journal, 44(1), 117–134. https://doi.org/10.1057/eej.2016.8

- Allen, F., & Gale, D. (2004). Competition and financial stability. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, 36(3b), 453–480. https://doi.org/10.1353/mcb.2004.0038

- Alvi, M. A., Akhtar, K., & Rafique, A. (2021). Does efficiency play a transmission role in the relationship between competition and stability in the banking industry? New evidence from South Asian economies. Journal of Public Affairs, 211, e2678. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa/2678

- Amidu, M., & Wolfe, S. (2013). Does bank competition and diversification lead to greater stability? Evidence from emerging markets. Review of Development Finance, 3(3), 152–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rdf.2013.08.002

- Barth, J. R., Lin, C., Ma, Y., Seade, J., & Song, F. M. (2013). Do bank regulation, supervision and monitoring enhance or impede bank efficiency? Journal of Banking and Finance, 37(8), 2879–2892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.04.030

- Beck, T., Demirguc-Kunt, A., & Levine, R. (2005). Bank concentration and fragility: impact and mechanics (No. 11500; Working Paper Series). https://econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:nbr:nberwo:11500

- Beck, T., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Levine, R. (2006). Bank concentration, competition, and crises: First results. Journal of Banking and Finance, 30(5), 1581–1603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2005.05.010

- Beck, T., Cull, R., Fuchs, M., Getenga, J., Gatere, P., Randa, J., & Trandafir, M. (2010). Banking sector stability, efficiency, and outreach in Kenya. In World Bank Policy Research Working Paper (Development Research Group Finance and Private Sector Development Team; Issue October). https://doi.org/10.1813/-9450-5442

- Bending, T., Downie, A., Giordano, T., Minsat, A., Losch, B., Marchettini, D., Maino, R., Mecagni, M., & Olaka, H. (2015). Recent trends in banking in sub-Saharan AFRICA: from financing to investment. In European investment bank European Investment Bank http://hdl.handle.net/10419/163410

- Berger, A. N., Klapper, L. F., & Turk-Ariss, R. (2009). Bank competition and financial stability. Journal of Financial Services Research, 35(2), 99–118. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10693-008-0050-7

- Bikker, J., & Haaf, K. (2002). Measures of competition and concentration in the banking industry : A review of the literature. Economic & Financial Modelling, 9(2), 53–98. http://www.dnb.nl/binaries/Measures_of_Competition_tcm46-145799.pdf

- Bikker, J. A., & Haaf, K. (2002). Competition, concentration and their relationship: An empirical analysis of the banking industry. Journal of Banking and Finance, 26(11), 2191–2214. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-4266(02)00205-4

- Bikker, J. A. (2004). Competition and efficiency in a unified European banking market. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Blundell, R., & Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87(1), 115–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4076(98)00009-8

- Boyd, J. H., & De Nicolò, G. (2005). The theory of bank risk taking and competition revisited. The Journal of Finance, 60(3), 1329–1343. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2005.00763.x

- Boyd, J. H., De Nicoló, G., & Jalal, A. M. (2006). Bank risk-taking and competition revisited: new theory and new evidence. IMF Working Paper, 06(297), 1–49. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781451865578.001

- Caminal, R., & Matutes, C. (2002). Market power and banking failures. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 20(9), 1341–1361. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-7187(01)00092-3

- Claessens, S., & Laeven, L. (2004). What drives bank competition? Some international Evidence. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, 36(3b), 563–583. https://doi.org/10.1353/mcb.2004.0044

- Danisman, G. O., & Demirel, P. (2019). Bank risk-taking in developed countries: The influence of market power and bank regulations. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 59, 202–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2018.12.007

- Davis, E. P., Karim, D., & Noel, D. (2020). The bank capital-competition-risk nexus – A global perspective. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2019.101169

- Davoodi, H. R., Dixit, S. V. S., & Pinter, G. (2013). Monetary transmission mechanism in the East African community: an empirical investigation. IMF Working Papers, 13(39), 59. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781475530575.001

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Detragiache, E. (2005). Cross-country empirical studies of systemic bank distress: A survey. National Institute Economic Review, 192(1), 68–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/00279/50105/1920/0108

- Demirgüç-kunt, A., & Huizinga, H. (2013). Are banks too big to fail or too big to save ? International evidence from equity prices and CDS spreads. Journal of Banking & Finance, 37, 875–894. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2012.10.010

- Dutta, K. D., & Saha, M. (2021a). Do competition and efficiency lead to bank stability? Evidence from Bangladesh. Future Business Journal, 7(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43093-020-00047-4

- Dutta, K. D., & Saha, M. (2021b). Nonlinearity of competition-stability Nexus: evidence from Bangladesh. Etikonomi, 20(1), 55–66. https://doi.org/10.15408/etk.v20i1.15984

- EAC. (2011). 4th EAC development strategy (2011/12 – 2015/16) - deepening and accelerating integration (Issue August). https://www.foresightfordevelopment.org/sobipro/54/237-eac-development-stragety-201112-201516-deepening-and-accelerating-integration

- EAC. (2019). Financial Sector Development. East African Community. https://www.eac.int/financial/financial-sector-development

- Efthyvoulou, G., & Yildirim, C. (2014). Market power in CEE banking sectors and the impact of the global financial crisis. Journal of Banking and Finance, 40(1), 11–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.11.010

- Fu, X. M., Lin, Y. R., & Molyneux, P. (2014). Bank competition and financial stability in Asia Pacific. Journal of Banking and Finance, 38(1), 64–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.09.012

- Goetz, M. R. (2018). Competition and bank stability. Journal of Financial Intermediation, 35, 57–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfi.2017.06.001

- Ibrahim, M. H., Salim, K., Abojeib, M., & Yeap, L. W. (2019). Structural changes, competition and bank stability in Malaysia’s dual banking system. Economic Systems, 43(1), 111–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecosys.2018.09.001

- IJtsma, P., Spierdijk, L., & Shaffer, S. (2017). The concentration–stability controversy in banking: New evidence from the EU-25. Journal of Financial Stability, 33, 273–284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfs.2017.06.003

- Kasman, S., & Kasman, A. (2015). Bank competition, concentration and financial stability in the Turkish banking industry. Economic Systems, 39(3), 502–517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecosys.2014.12.003

- Keeley, M. C. (1990). Deposit insurance, risk, and market power in banking. The American Economic Review, 80(5), 1183–1200. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2006769

- Kodongo, O., Natto, D., & Biekpe, N. (2015). Explaining cross-border bank expansion in East Africa. Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, 36, 71–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intfin.2014.12.005

- Kouki, I., & Al-Nasser, A. (2017). The implication of banking competition: Evidence from African countries. Research in International Business and Finance, 39, 878–895. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ribaf.2014.09.009

- Lewbel, A. (2012). Using heteroscedasticity to identify and estimate mismeasured and endogenous regressor models. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, 30(1), 67–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/07350015.2012.643126

- Lewbel, A. (2018). Identification and estimation using heteroscedasticity without instruments: The binary endogenous regressor case. Economics Letters, 165, 10–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2018.01.003

- Liu, H., Molyneux, P., & Wilson, J. O. S. (2013). Competition and stability in european banking: A regional analysis. The Manchester School, 81(2), 176–201. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9957.2011.02285.x

- Martinez-Miera, D., & Repullo, R. (2010). Does competition reduce the risk of bank failure? Review of Financial Studies, 23(10), 3638–3664. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhq057

- Matutes, C., & Vives, X. (2000). Imperfect competition, risk taking, and regulation in banking. European Economic Review, 44(1), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0014-2921(98)00057-9

- Mirzaei, A., Moore, T., & Liu, G. (2013). Does market structure matter on banks’ profitability and stability? Emerging vs. advanced economies. Journal of Banking and Finance, 37(8), 2920–2937. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.04.031

- Mishkin, F. S. (1999). Financial consolidation: Dangers and opportunities. Journal of Banking and Finance, 23(2–4), 675–691. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-4266(98)00084-3

- Oduor, J., Ngoka, K., & Odongo, M. (2017). Capital requirement, bank competition and stability in Africa. Review of Development Finance, 7(1), 45–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rdf.2017.01.002

- Roodman, D. (2009). How to do xtabond2: An introduction to difference and system GMM in Stata. The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata, 9(1), 86–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X0900900106

- Saha, M., & Dutta, K. D. (2020). Nexus of financial inclusion, competition, concentration and financial stability: Cross-country empirical evidence. Competitiveness Review: An International Business Journal, 31(4), 669–692. https://doi.org/10.1108/CR-12-2019-0136

- Saif-Alyousfi, A. Y. H., Saha, A., & Md-Rus, R. (2020). The impact of bank competition and concentration on bank risk-taking behavior and stability: Evidence from GCC countries. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 51, 100867. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.najef.2018.10.015

- Schaeck, K., Cihak, M., & Wolfe, S. (2009). Are competitive banking systems more stable? Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, 41(4), 711–734. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-4616.2009.00228.x

- Schaeck, K., & Cihák, M. (2014). Competition, efficiency, and stability in banking. Financial Management, 43(1), 215–241. https://doi.org/10.1111/fima.12010

- Smith, B. D. (1984). Private information, deposit interest rates, and the “stability” of the banking system. Journal of Monetary Economics, 14(3), 293–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3932(84)90045-X

- Turk-Ariss, R. (2010). On the implications of market power in banking: Evidence from developing countries. Journal of Banking and Finance, 34(4), 765–775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2009.09.004

- Uhde, A., & Heimeshoff, U. (2009). Consolidation in banking and financial stability in Europe: Empirical evidence. Journal of Banking and Finance, 33(7), 1299–1311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2009.01.006

- Vives, X. (2010). Competition and Stability in Banking. (Working Papers Central Bank of Chile, Issue 576). https://ideas.repec.org/p/chb/bcchwp/576.html

- Windmeijer, F. (2005). A finite sample correction for the variance of linear efficient two-step GMM estimators. Journal of Econometrics, 126(1), 25–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2004.02.005