?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study examines the relative effects of the different types of international financial flows on economic performance in Kenya both in the long- and short-runs using the autoregressive distributed lag model (ARDL) bounds approach and data for the period 1970 to 2017. This is against the backdrop of the government of Kenya which has targeted attracting foreign capital inflows as one of the key measures to achieving the economic pillar of the Kenya Vision 2030. The aim is to achieve an economic growth rate of 10 per cent annually and sustaining the same until 2030. After a very rigorous and careful model selection exercise, the results robustly reveal a very strong long-run causality running solely from portfolio equity to economic growth with a positive and significant effect on economic growth. In the short-run, the effect of portfolio equity on economic growth is also very positively strong. In contrast, all the other capital flows have very weak long-run relationship with economic growth with causality running only from economic growth to the capital flows.

1. Introduction

Foreign capital inflow plays an important role in the economic growth of developing countries to supplement domestic savings for investment and growth. There is a great need for foreign capital in Africa given its high poverty levels and low domestic capacity to save. The realisation of this need has led many African countries, including Kenya, to liberalise their financial systems to attract foreign capital. In Kenya, efforts to attract foreign capital flows began with the operation of rapid capital account liberalisation from 1991 to 1995. Such efforts included relaxing restrictions on foreign currency transactions and introducing foreign exchange bearer certificates of deposit (FEBCs). Restrictions on portfolio investments, excluding some exceptions, on capital account transactions were also removed (Yoshino et al., Citation2015).

In 2008, Kenya launched its “Vision 2030” initiative as a vehicle for accelerating the transformation of the country into a rapidly industrialising middle-income nation by 2030. It also aims to make the country globally competitive and prosperous where every individual will have a high quality of life by the year 2030 (Ndung’u et al., Citation2011). This vision is supported by three pillars, which are the economic, social, and political pillars. The objective of the economic pillar is “to maintain a sustained economic growth of 10 percent per annum for 25 years”. This is expected to be achieved through internally generated resources while Kenya continues to benefit from remittances by the Kenyans in diaspora, increased foreign direct investment (FDI), foreign portfolio investment (FPI), and cooperation from its development partners (Government of the Republic of Kenya, Citation2007).

The economic growth in Kenya is expected to be achieved by increasing savings and investment to more than 30 percent of GDP (Ndung’u et al., Citation2011). In the face of these efforts, capital flows into Kenya have historically been moderate. Although official development assistance (ODA) has previously been high, it has declined recently. This raises two questions: How to attract foreign capital flows; and which one of these is best to focus on given that their relative contribution to economic growth may not be the same since the effects of capital flow on economic growth depend on the type of foreign capital and the type of economy (Adeola & Aziakpono, Citation2017; Aizenman et al., Citation2013).

The available empirical literature reveals that the effects of capital flows on economic growth have not been consistent. Some studies argue that foreign capital flows would improve economic growth in developing countries (Aizenman et al., Citation2013; Bailliu, Citation2000), while others argue that foreign capital flows have a negative effect on growth (Durham, Citation2004; Murshid & Mody, Citation2011). By and large, most studies conducted in the Kenyan context have focused on one capital flow, mainly FDI (Abala, Citation2014; Ngeny & Mutuku, Citation2014), or remittance (Mwangi & Mwenda, Citation2015). Very few attempts have been made at studying a combination of capital flows (Ocharo et al., Citation2014; Ojiambo & Ocharo, Citation2016).

This study will contribute to the existing body of knowledge by investigating the relationship between capital flows and economic growth in the Kenyan context. The main aim of this study is to investigate and determine the effect of five foreign capital flows, namely FDI, portfolio equity, debt liabilities, foreign aid and remittance, on the economic growth of Kenya over the past four decades; and to determine which of the capital flows benefits the economy most. Even though it is important to know the contribution of each of the five identified capital flows in the economy, it is imperative to know the effect of the economy on each of these capital inflows. The study is motivated by the present agenda of the Kenyan government to pursue “Vision 2030” through increases in remittances and foreign capital flows, such as foreign direct investment and foreign portfolio investment. To achieve the desired goal of the economic pillar, the government may need to concentrate on the capital flow that contributes most to economic growth. This necessitates a study to determine the contributions of each capital to growth which will enable policymakers in Kenya to know which specific capital flow is best to target for the desired result.

The rest of the paper is organised as follows: Section 2 provides a review of both the theoretical and empirical literature. In section 3, we focus on the context of Kenya highlighting foreign capital flows. Section 4 presents the econometric procedure employed in the analysis, while section 5 presents and discusses the results. Section 6 summarises and concludes the paper with relevant policy recommendations.

2. Literature review

The literature on foreign capital flows has grown over the years and has been backed by various theories and framework on how the different capital flows impact economic growth. Below, we highlight the model and premise on which this work is based.

2.1. Theoretical framework

This study employs the endogenous growth model—popularly known as the “AK model”—used by Pagano (Citation1993) and its extended form by Bailliu (Citation2000), who introduced international capital flows to capture the relationship between foreign capital flows and economic growth. Here, the aggregate output is a linear function of the aggregate capital stock:

where Yt = aggregate output in time (t); Kt = capital stock in time (t) which is a combination of both physical and human capital; and A = marginal productivity of capital (MPK). It is assumed that (i) the population growth rate is constant; and (ii) the economy produces a single good, which can either be consumed or invested. If invested, the capital stock depreciates at the rate of δ per period, and then gross investment is given as:

However, the transmission of savings into investment requires financial intermediaries where a proportion of savings (1 −) is taken as compensation for services offered. The remaining savings is equal to investment.

The growth rate of output, g, from equations (1)—(3) without the time subscript is given by:

where s = gross saving rate. Equation (4) is the steady state growth rate of a closed economy.

From the above, financial development has an impact on economic growth through financial intermediaries effectively allocating savings for investment. The expertise of banks through increased intermediation results in a reduction of the spread between lending and borrowing rates, which in turn leads to an increase in the proportion of savings invested, thereby leading to an increase in g through the increase in from equation (4). In addition, financial intermediation allocates capital to more productive investments and channels funds to investments where there is higher marginal productivity of capital, thereby leading to higher growth.

The above framework is extended to integrate foreign capital flows that draw on the work of Bailliu (Citation2000) and Aziakpono (Citation2013). The closed-economy assumption is relaxed here to allow free movement of capital into and out of the domestic economy. The above equilibrium conditions can be modified to adjust for the effects of foreign capital flows as follows:

where FCFt is the net foreign capital flows and * represents open economy. The new steady-state growth rate is represented as:

In the absence of any friction, the model suggests an increase in capital flows to the developing country (FCFt > 0), which will help to augment domestic savings (s* > s). In a situation where the foreign capital inflow is invested productively and not consumed, the level of domestic investment in the developing country will rise, which in turn will lead to an increase in economic growth (g* > g).

The different capital flows, however, lead to growth in different ways. In the case of FDI, it leads to growth directly through increase in stock of physical capital in the host economy as the foreign capital is accumulated. FDI can also affect growth indirectly by inducing human capital development through training and skill acquisition; and strongly encouraging technological upgrading (De Mello, Citation1997).

Equity portfolios affect growth differently from FDI. According to Levine and Zervos (Citation1998), liberalising constraints on foreign portfolio flows tends to increase domestic stock market liquidity, which could have a positive effect on productivity and growth. The volatile nature of portfolio equity might, however, prevent it from having a positive effect on growth, especially where there are political instability or government policies that are not favourable to foreign investors.

Foreign aid affects the growth of an economy mainly through development projects and investment rather than consumption. The general argument behind the aid-growth theory is that physical capital leads to economic growth. Foreign aid is usually used to fill gaps in the economy, such as the savings gap (S-I),Footnote1 which is a combination of the foreign exchange gap or external financing gap (X-M),Footnote2 as well as the fiscal gap (G-T).Footnote3 The “two-gap” model specified in Easterly (Citation2003) as developed by Chenery and Strout (Citation1966) has been employed to explain the link between foreign aid and economic growth. This is shown as: g = (I/Y)/µ; and I/Y = A/Y + S/Y, where I = required investment; Y = output; g = targeted GDP growth; A = aid; S = domestic savings and µ = Incremental capital-output ratio (ICOR). This model explains how foreign aid increases investment and how investment leads to increase in economic growth.Footnote4 This has also been used to explain foreign debt flows. According to Pattillo et al. (Citation2002), there are different aspects of the theory on foreign debt flows and economic growth. One view shows that a rational level of debt is expected to have a positive effect on growth, while another view suggests that large, accumulated debt stocks may be a deterrent to growth. The third view combines both of these perspectives.

Remittances generally help to develop financial markets, finance entrepreneurial activities, act as insurance against shocks, finance household expenditure and household human capital formation, and bridge the savings investment (S-I) and external financing (X-M) gaps. In turn, this would lead to an increase in economic growth. The literature has grouped migrant remittances into two main components, namely the endogenous migration approach and the portfolio approach (Elbadiwi & Rocha, Citation1992; Chami et al., Citation2003). The endogenous migration approach is based on the economics of the family, which includes but is not limited to motivations based on altruism. The portfolio approach stems from the decision to invest in home country assets. The portfolio view is a theory that supports the view that remittance behave like other foreign capital flows.

2.2. Empirical evidence on foreign capital flows and economic growth

Empirical literature that grapples with how foreign capital flows affect economic growth has grown over time and one can see that the observed effects are also often inconclusive. The growing empirical studies on this subject have focused on one form of capital flow or the other at a time. For example, studies that solely focused on FDI (Adjasi et al., Citation2012; Alfaro et al., Citation2004; Borensztein et al., Citation1998), equity portfolio investment (Chinn & Ito, Citation2006; Durham, Citation2004; Levine & Zervos, Citation1998), debt flows (Baharumshah & Thanoon, Citation2006; Soto, Citation2000), bank lending (Baharumshah & Thanoon, Citation2006; Reisen & Soto, Citation2001), foreign aid (Burnside & Dollar, Citation2000; Easterly, Citation2003), and remittance (Acosta et al., Citation2008; Adenutsi et al., Citation2011; Giuliano & Ruiz-Arranz, Citation2009; Lartey, Citation2013) have been previously documented in literature.

Some studies that documented positive effect of foreign direct investment on economic growth emphasised the success being dependent on the presence of certain host country conditions such as human capital (Borensztein et al., Citation1998; Balasubramanyam et al. Citation1999; and Bengoa & Sanchez-Robles, Citation2003); good policy environment (Balasubramanyam et al., 1996); a well-developed market structure (Alfaro et al., Citation2006); and the interaction of local financial markets (Adjasi et al., Citation2012; Alfaro et al., Citation2004). Theoretical benefits of FDI seems to outweigh its demerits as well as empirical evidence advanced based on the type of economy. Despite these benefits, negative relationship has been documented. Carkovic & Levine, (Citation2002) showed that the effects of FDI on growth observed with 72 countries were inconsistent with the popular belief of a favourable impact on growth while Adams (Citation2009) observed that FDI has a net crowding out effect from the study of 42 sub-Saharan African countries. A recent study on FDI in Africa seem to suggest that FDI has positive effect on the economic growth of only the more advanced African countries (Claudio-Quiroga et al., Citation2022)

Evidence on foreign aid by Durbarry et al. (Citation1998) and Burnside and Dollar (Citation2000) suggest that the presence of a stable macroeconomic policy environment (fiscal, monetary and trade policies) contributes to it exerting a positive impact on growth in developing countries. whereas less emphasis on the policy environment was placed by other studies (Lu & Ram, Citation2001; Dalgaard & Hansen, Citation2001; Hansen & Tarp, Citation2001; Headey, Citation2008). A recent study on foreign aid in Bangladesh, however, suggests that foreign aid plays a favourable role in economic growth (Hussain & Rahman, Citation2022). Bayale et al. (Citation2022) emphasised a positive threshold effect of foreign aid.

Portfolio equity studies are not as numerous compared to foreign direct investment; however, the few available studies identify the development and regulation of the banking system as a necessity for equity investment (Chinn & Ito, Citation2006; Durham, Citation2004). Durham (Citation2004) found that foreign portfolio equity investment depends on the host country’s absorptive capacity regarding financial or institutional development and if uncontrolled might have a negative effect on economic growth. Chinn and Ito (Citation2006) emphasised that higher level of financial openness leads to equity market development only if a threshold level of legal development has been reached.

Empirical evidence on foreign debt flows suggest they generally contribute more adversely to economic growth than favourably (Ndikumana & Boyce, Citation2003; Adegbite et al., Citation2008). Bordo et al. (Citation2010) found that external debt leads to negative growth since a high ratio of capital inflows to GDP is linked with currency crisis. However, some studies suggest that debt flow is not outrightly negative, but after a certain threshold, the positive effect of debt on growth would cease to exist (Fosu, Citation1996; Checherita-Westphal & Rother, Citation2010). Reinhart & Rogoff (Citation2010) showed that the level of development of a country determines its threshold level with developing countries having lower thresholds for external debt than advanced countries.

Contrary to foreign debt, remittance are mostly believed to have a positive impact on growth (Beine et al., Citation2001; Fajnzylber & Lopez, Citation2007; Acosta et al., Citation2008; Pradhan et al., Citation2008; Mundaca, Citation2009; Chowdhury, Citation2011; Ur Rehman & Hysa, Citation2021; Imran et al., Citation2021), and mostly through financial development (Giuliano & Ruiz-Arranz, Citation2009; Aggarwal et al. Citation2011; Nyamongo et al., Citation2012); and through the existence of sound policies and institutions (Catrineseu et al. Citation2009). Since remittance are mostly private transfers to individuals, they have been found to have a direct reducing effect on poverty (Gupta et al., Citation2009). Other positive effects of remittance were documented on education (Ait Benhamou & Cassin, Citation2021); education and health in Latin America (Acosta et al., Citation2008); and the financial system in sub-Saharan Africa (Fayissa & Nsiah, Citation2010). Although Barajas et al. (Citation2009) observed a negative effect of remittance on long-run growth on a sample of 84 countries over a period of 35 years. A recent study on remittance in South Africa reveals a negative effect of remittance on economic growth (Nyasha & Odhiambo, Citation2022). Another study on low-, middle-, and high-income countries show that remittance increase economic growth in all three income groups (Pal et al., Citation2022).

While numerous studies have focused on each type of capital flow as presented above, their results are still ambiguous and inconclusive. Very few attempts have been made in general in comparing their contribution on economic growth. A few exceptions are (Aizenman et al., Citation2013; Driffield & Jones, Citation2013; Reisen & Soto, Citation2001). Aizenman et al. (Citation2013) observed that the link between growth and lagged capital flows depends on the type of flows, economic structure, and global growth patterns. In their study of 105 countries from 1990 to 2010 using panel data estimation, they found a robust relationship between FDI (both inflows and outflows) and growth but a smaller and less stable relationship between growth and equity flows. On the other hand, the relationship between growth and short-term debt was found to be nil before the 2008 financial crisis, and negative during the crisis period.

Closely related to this study is the work of Driffield and Jones (Citation2013). They studied a large number of developing countries for the years 1984 to 2007 using the three stage least square (3SLS) panel system estimator and concluded that all sources of foreign capital observed by them (FDI, ODA and workers’ remittances) have a positive and significant effect on growth. This was the case when institutions were taken into consideration as ODA became positive only when the bureaucracy of disseminating was considered.

An earlier study conducted by Reisen and Soto (Citation2001) on a sample of 44 countries using annual data from 1986 to 1997 revealed a similar result. They used generalized method of moments (GMM) technique to estimate the independent growth effects of various capitals flows (FDI, equity and bond flows, long-term bank credit and short-term bank lending). Their result showed that capital flows exerted a positive significant impact on growth except for bank lending that revealed a positive effect only when the banking system is well capitalized. They therefore concluded that in order to achieve long-term growth targets, domestic savings should not be relied solely upon by developing countries, but attention should be paid to boost FDI and portfolio equity inflows.

The different results obtained emanate from differences across studies, such as the measure of capital flows in the observation, time covered, country sample groups mostly aggregating developed and developing countries together, econometric estimation method adopted, and the control variables used. Despite these variations, most studies hitherto seem to agree that the effect on economic growth depends on the particular type of capital flow (Adeola, Citation2017; Adeola & Aziakpono, Citation2017; Aizenman et al., Citation2013; Driffield & Jones, Citation2013).

2.3. Empirical evidence in Kenya

In this section, we focus on the few studies on Kenya that have used time-series analysis which caters for the inherent flaws of cross-sectional and panel analyses that do not allow for country-specific inferences from the estimation.

Almost all the studies on Kenya adopted the ordinary least square (OLS) estimation technique and mostly focus on FDI (Nyamwange, Citation2009; Abala, Citation2014; Ngeny & Mutuku, Citation2014; Mwangi & Mwenda, Citation2015). These studies generally found that capital flows have a positive effect on the economic growth in Kenya. For example, Nyamwange (Citation2009) found GDP growth has a positive and statistically significant effect on FDI for the period 1980 to 2006 using OLS estimation. This implies that as the economy improves, more FDI is attracted. Similarly, Abala (Citation2014) concentrated on the determinants of FDI on Kenya for the period 1970 to 2010 using OLS estimation. It was found that market size, political stability, openness of the economy and infrastructure increase FDI in Kenya. Ngeny & Mutuku (Citation2014) found a positive effect of FDI on growth, but a negative effect of FDI volatility on growth in Kenya for the period 1970 to 2011 using the OLS estimation and Exponential Generalized Autoregressive Conditional Heteroscedasticity (EGARCH) estimation techniques. They observed FDI volatility hinders long-run economic growth and therefore concluded that unstable inflows may inhibit investment, thereby affecting economic growth negatively.

An earlier time-series study on Kenya was carried out by M’Amanja and Morrissey (Citation2006), focusing exclusively on foreign aid. Using the Vector Autoregressive model (VAR) and Vector Error Correction Modelling (VECM) techniques, they found that foreign aid and private investment Granger cause output in Kenya for the period 1964 to 2002. They observed that aid in the form of net external loans has a significant negative impact on long-run growth. Mwangi and Mwenda (Citation2015) focused on remittance in Kenya and found that for the period 1993 to 2013, using OLS estimation and the Granger causality method, international remittance indicators were significant factors influencing economic growth.

To the best of our knowledge, only two studies, Ocharo et al. (Citation2014) and Ojiambo and Ocharo (Citation2016) examined the effect of different capital flows on the economic growth in Kenya. Ocharo et al. (Citation2014) focused on the causality between private capital inflows (FDI, portfolio investment, and cross-border interbank borrowing) and economic growth in Kenya for the period 1970 to 2010 using OLS estimation and the Granger causality test. They observed a positive effect of FDI, FPI, and cross-border interbank lending on GDP growth; however, while FDI was statistically significant, FPI and cross-border interbank borrowing were statistically insignificant. FDI was found to lead to economic growth, while economic growth causes cross-border interbank borrowing in Kenya. Ojiambo and Ocharo (Citation2016) studied the impact of foreign aid, foreign direct investment, and remittances on economic growth in Kenya using the ARDL approach. This is closely related to our study.

Our study, however, contributes to the literature in three ways. First, our study covers a wider range of private Capital flows than Ocharo et al. (Citation2014), and Ojiambo and Ocharo (Citation2016) . This is necessary to determine the relative contributions of the alternative capital flows. Second, we adopt more advanced estimation technique and extending the analysis to 2017, thereby providing the most current evidence in Kenya. Third, we not only look at the effects of the five capital flows studied on the economic growth but also the effect of the economy on the capital flows by establishing if the economic growth in Kenya contributes to its attractiveness for foreign capital investment.

3. Foreign capital flows in Kenya

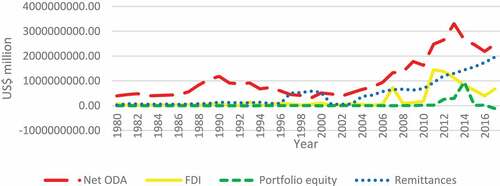

Kenya operated a closed capital account from 1970 to 1992 and therefore there was hardly any net portfolio flows during this period, except for 1975 to 1977 and in 1980. Kenya subsequently experienced rapid capital account liberalisation from 1991 to 1995, which included relaxing restrictions on foreign currency transactions and introducing foreign exchange bearer certificates of deposits (FEBCs). As of 1995, all remaining foreign exchange controls were abolished, although the Kenyan central bank retained the authority to license and regulate foreign exchange transactions. Restrictions on portfolio investments and capital account transactions were also removed, subject to a few exceptions: a ceiling on purchases of equity by non-residents (40% on aggregate, 5% for individual investors); requisite approval from the Capital Markets Authority prior to the issuance of securities locally by non-residents or abroad by residents as well as derivative securities; and prior government approval for the purchase of real estate (Yoshino et al., Citation2015: 13).

Like many sub-Saharan African countries, Kenya has adopted policies aimed at attracting foreign capital. Besides liberalization of its capital accounts, regional and economic integration policies and strategies were also adopted to increase foreign capital flows, such as Kenya’s membership of the East African Community (EAC) and the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA) to encourage free trade between the regions.

Among the interventions embarked upon in Kenya were the launching of Vision 2030 in 2008, with the objective of achieving global competitiveness by accelerating transformation of the country into a rapidly industrialising middle-income nation by 2030 and gaining economic prosperity with a high quality of life. This national initiative has inspired greater commitment to attracting FDI, portfolio investments and remittances to assist in achieving higher economic growth rates in the region of 10% per annum.

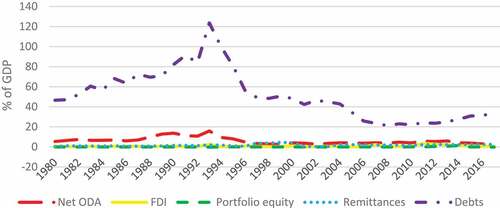

Kenya experienced a sharp downward spiral in economic growth from late 1991, with GDP growth plummeting from 4.19% in 1990 to 1.44% in 1991 and then to −0.8% in 1992 (Figure ). GDP growth receded to its lowest average level in the 1990s, recording 2.24% per year on average for the decade. GDP growth picked up notably in Kenya in the 2000s and by 2007, it stood at 6.99%. Following the onset of the global financial crisis in 2008, however, it again dropped to 1.53% as Kenya was a major hub for FDI in the Eastern African bloc. The political unrest following the 2007 elections in the country might also have been a contributing factor to the drastic decrease in GDP growth observed in 2008. Nevertheless, by 2010 economic growth had rebounded to 8.41% and has been fairly stable above 4.5% during the last eight years up to 2017, averaging 5.85% per year over this period.

Figure 1. GDP growth rate in Kenya (1980–2017).Source: Author’s based on World Bank World Development Indicators database 2019

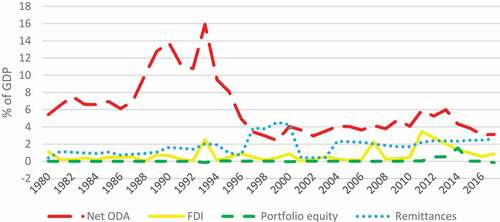

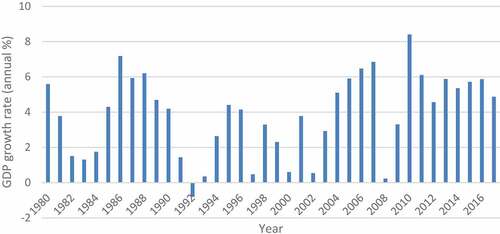

Historically, Kenya was one of the main destinations for foreign direct investment in East Africa in the 1970s. In recent years foreign capital in Kenya has been on the increase, especially remittances and debts (Figures ). For instance, remittances increased from US$570 million in 2006 to a substantial US$1.44 billion in 2014. FDI and portfolio equity also increased from US$50.7 million and US$1.8 million to US$944 million and US$954 million, respectively, over the same period. Debt liabilities increased from US$565 million in 2009 to US$1.977 billion in 2013, while ODA recorded the highest increase from US$946 million in 2006 to US$32.36 billion in 2013.

Figure 2. Foreign capital flows to Kenya in millions (Current US$).Source: Author’s based on World Bank World Development Indicators database 2019

Figure 3. Foreign capital flows to Kenya in millions (Current US$) (without debt stock).Source: Author’s based on World Bank World Development Indicators database 2019

As a ratio of GDP, all foreign capital flows remain moderate (Figures ). Only ODA showed a fairly high share of GDP, especially in the 1990s. GDP growth was also relatively high around the period of high ODA.

4. Data and methodology

4.1. Variables and data sources

This study employs annual data obtained mostly from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators (WDI) database (GDP per capita, Net ODA, exports, imports, government expenditure, trade, domestic investment, inflation) and the World Bank’s Global Financial Development Database (GFDD) (Remittance, liquid liabilities, and private credit). Data on some of the capital flows such as the stock of FDI, portfolio equity and debt liabilities were obtained from the Lane & Millesi-Ferretti (LMF) updated dataset (External Wealth of Nations Mark II: Revised and updated 1970–2017). This period was chosen to capture the period of increased capital flows to Kenya and allow sufficient period for time-series analysis. GDP per capita is used as a proxy for economic growth with five capital flows and eight control variables.

The capital flows are all expressed as a percentage of GDP and converted to their natural logarithm (LN) form. The capital flows used in the estimation are foreign direct investment liability stock (FDI), portfolio equity liability stock (PES), debt liability stock (DLS), remittances (REM) and official development assistance (ODA). The explanatory variables used are the standard growth determinants obtained from the literature and include gross-fixed capital formation as a proxy for domestic investment (DI), inflation—for macroeconomic instability (INF), general government final consumption expenditure (GCE), exports of goods and services (EXP), imports of goods and services (IMP), openness to trade (XM), two measures of financial development: liquid liabilities (M3) as percentage of GDP (LL), and private credit by deposit money banks to GDP (PC).

4.2. Analytical framework

An autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) model is specified following Pesaran, Shin & Smith (Citation2001) and Ikram et al. (Citation2021). Each model is limited to four variables to avoid the problem of loss of degree of freedom where = f (Y, CF, CV1, CV2). The measure of economic growth, denoted as Y, is the same in all the models. A measure of each of the five different capital flows (CF) namely DLS, FDI, PES, ODA and REM is used with a pair of non-highly correlated control variables (CV1 and CV2) at a time. The control variables are LNDI, LNEXP, LNLL, LNGCE, LNIMP, LNINF, LNPC, and LNXM where LN stands for logarithm of each variable defined in the data section above.

For instance, in addition to the measure of economic growth, represented as Y, a capital flow is included starting with the log of debt liability stock (LNDLS) and introduce two uncorrelated control variables at a time until all eight control variables have been used in a model. The capital flow is replaced, in this case with log of foreign direct investment stock (LNFDI), and work through all the control variables until all the capital flows and control variables have been combined.

To compare the result, the coefficient of each of the measures of capital flows is observed to determine which one has the stronger effect on economic growth. The capital flow that has the highest and statistically significant positive effect on economic growth is regarded as the best for the economy.

4.3. Econometric procedure

As is required for time-series estimation, we commence with stationarity test for each of our variables to establish if our variables are stationary at level or first difference. We use the Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test as well as the break-point unit root test. We determine the optimal lag length for all our variables using the Schwarz Bayesian Information criteria.

We employ the ARDL model to determine the existence of a long-run relationship between foreign capital flows and economic growth in Kenya. This approach is favoured to the other cointegration techniques as it has some advantages according to Pesaran et al (Citation2001). The ARDL is more efficient for small sample data sizes, it produces unbiased estimates of the long-run model and can be used where variables are integrated of different orders such as I(0) and I(1) variables.

The ARDL model is specified as: ARDL (p, q1, q2, q3) and it is represented as ARDL (Y, CF, CV1, CV2) since our model is limited to four variables. We use either Y or CF as the dependent variable to determine whether to specify an ARDL Model or ECM model. We conducted a bound test as in Equationequations 7(7)

(7) and Equation8

(8)

(8) below and use the significance of the F-statistics test to determine presence of co-integration among the variables.

Bounds test specification

To determine whether cointegration exist we compared the F-statistic of the test with the asymptotic critical values computed by Pesaran et al. (Citation2001) for the lower and upper bounds. If the F-statistic is greater than the upper bounds value, we conclude that there is cointegration among the variables, whereas if the test statistic is lower than the lower bounds value, we cannot reject the null hypothesis of no cointegration. However, if the test statistic falls within the lower and upper bound values, then we conclude that the test is inconclusive. For inconclusive cases, we did not proceed further.

Where there is no co-integration among the variables, we specify and estimate an ARDL model as:

Where we establish that there is co-integration among the variables, we proceeded to specify and estimate an error correction model (ECM) as:

Finally, we perform residual diagnostics tests such as heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation tests to ensure the models are well behaved. Only models that passed all residual diagnostic tests are reported.

5. Empirical results

The empirical analysis commenced with unit root tests. The ADF unit root test results are reported in Table and the break point unit root test results reported in Table . The results show that both or at least one of the tests indicate that most of the variables are stationary at first difference I(1) except for remittances, imports and inflation which are stationary at level I(0). From this unit root test, the ARDL bounds testing approach can be performed since this is best suited for variables with different degree of integration that is I(0) and I(1), but not I(2).

Table 1. ADF unit root test results

Table 2. Breakpoint unit root test results

The ARDL bounds testing approach was performed after the lag length selection. A total of 50 models were estimated, five for each of the five capital flows where economic growth was the dependent variable; and another five for each capital flow where a measure of capital flows was the dependent variable. and presents the bounds test results. The models were tested for serial correlation and heteroscedasticity. In all the models performed, only a few of them were found to have co-integrating relation, which shows that a long-run relationship exists among them. Out of these models, a substantial part of them did not pass the residual diagnostics tests and therefore were not reported.

Table 3a. ARDL Bounds test results: Economic growth as dependent variable

Table 3b. ARDL Bounds test results: Capital flows as dependent variable

Table 4. Pairwise Granger causality test

Granger causality test was conducted to determine the nature of causality- a unidirectional causality from economic growth to capital flows or from capital flows to economic growth or a bi-directional causality. We established bi-directional causality only between portfolio equity and economic growth. There was no causality between official development assistance and economic growth. Causality was found from debt liability stock to economic growth while both foreign direct investment and remittances showed causality only from economic growth ().

The magnitude and sign of the causal effect was further explored. The slope coefficients of the estimated models and the error correction terms are reported in . Residual diagnostic tests were conducted, and the LM-statistics from the serial correlation test and the probability are reported. Where the probability was above 5% significance level (which signifies that the null hypothesis of no serial correlation at lag order cannot be rejected), it was taken that the model had passed the serial correlation test. The heteroscedasticity test was also performed. Here, the chi-square and probability values are reported, and the model had to pass this test with a probability level above 5% as well for it to be qualified as a good model. The explanatory power of the model, the adjusted R2 values are over 30% in all the models reported. The summary of the results is reported in .

Table 5. ARDL/short-run results—economic growth (Y) as dependent variable

Table 6. ARDL/long-run error correction modelling results—economic growth (Y) as dependent variable

In all the capital flows observed, only portfolio equity showed a bi-directional causality and indicated a positive and significant long-run relationship as well as short-run relationship with economic growth in Kenya. The speed of adjustment ranges from 18% to 26%. The positive result is probably because Kenya is one of the countries in Africa with a well-developed financial system, which makes portfolio equity investment into the country attractive. This finding supports the study of Chinn and Ito (Citation2006) of a positive effect of portfolio equity on economic growth.

Debt liability stock and official development assistance did not show any long-run relationship to economic growth. Only one model each for both foreign direct investment and portfolio equity stock showed a long-run relationship while remittances had three models indicating a long-run relationship.

In the case of FDI and ODA, we did not observe any causality between ODA and economic growth whereas FDI showed causality running from economic growth to FDI. No co-integration was observed between these two capital flows and economic growth. Hence, there was no long-run relationship between them in Kenya during the period of study. The lack of long-run relationship between ODA and economic growth mirrored the picture in Figure . Besides from the late 1980s to mid-1990s when the country received a substantial ODA, the trend since then has not moved in same direction with economic growth as highlighted in Figure . Hence, we believe our are more consistent with the emerging context of the country compared to Ojiambo and Ocharo (Citation2016) who observed a positive and significant effect of foreign aid on economic growth. FDI, however, showed a negatively insignificant short-run relationship with economic growth. Our findings corroborate the study by Ojiambo and Ocharo (Citation2016) which found a negative relationship between foreign direct investment and economic growth in Kenya. This is consistent with the very low inward FDI, and it has also been volatile. This is, however, not consistent with previous findings of the study by Ocharo et al. (Citation2014), which found both positive and statistically significant influence of foreign direct investment on economic growth in Kenya. Ngeny & Mutuku (Citation2014) also found that foreign direct investment has a positive influence on economic growth in Kenya. The discrepancy in results might be attributed to the use of different estimation techniques and the result of occurrences in the last few years as our data has been updated to reveal the current situation in Kenya. Our results may be consistent with the trends during the period we cover. Since FDI is mainly market-seeking in Kenya (Abala, Citation2014), it has the tendency of responding to political instability, high levels of crime, and general insecurity of life. A series of security issues, such as the United States embassy bombing of 1988, the 2002 Mombasa airport attack on an Israeli airplane as well as the Kikambala hotel bombing just after guests from Israel checked in may be a significant implication for the effect of FDI on growth. The relatively recent attacks by the Islamic group Al-Shabab and incidents, such as the Westgate Shopping Mall shooting in 2013 and the Garissa University College attack early in 2015 might instil fear in foreign investors and deter them from establishing a footprint in Kenya, thereby reducing certain types of capital flows. Such negative effects of terrorism on capital flows have been observed (Lanouar & Shahzad, Citation2021; Shahzad & Qin, Citation2019). This might also impact negatively on economic growth. The weak long-run relationship and casual effect between capital flows and economic growth in the country may be due to same climate in the country.

For debt liability stock, we observed causality running from debt flows to economic growth. No long-run relationship was observed but a negatively and insignificant short-run relationship was observed here.

Remittances on the other hand, show causality running from economic growth to remittances and there is co-integration between them. This implies the existence of a long-run relationship. The relationship is positive but weakly significant. This is in line with a recent study of international remittances on economic growth in Kenya by Mwangi and Mwenda (Citation2015) which revealed remittances showing positive and significant influence on economic growth in Kenya. Ojiambo and Ocharo (Citation2016) found remittances have a short-run negative effect on economic growth but positive effect after a period of one year. Pal et al. (Citation2022) also emphasises the positive effect of remittance on economic growth in low-, middle-, and high-income countries

6. Conclusion and recommendations

This study explored the relative contribution of the five major capital flows in Kenya to economic growth. The causal effect between the five capital flows and economic growth was analysed. Furthermore, the magnitude and sign of the long-run relationship between the identified capital flows and economic growth were investigated to determine which one contributes most to the economy. Residual diagnostic tests (heteroscedasticity and serial correlation) were conducted for all the models. We report only the models that satisfied all the residual diagnostic tests.

The results reveal that the causality between economic growth and capital flows in Kenya is, generally, very weak and is mostly unidirectional except for portfolio equity, which indicated bi-directional causality but mainly causality running from capital flow to economic growth. There was uni-directional causality running from economic growth to capital flows for both FDI and remittances whereas debt liability showed uni-directional causality running from capital flow to economic growth. There was no indication of causality between official development assistance and economic growth.

The results robustly reveal a very strong long-run causality running solely from portfolio equity to economic growth with a positive and significant effect on economic growth. In the short-run, the effect of portfolio equity on economic growth is also very positively strong. In contrast, all the other capital flows have very weak long-run relationship with economic growth with causality running only from economic growth to the capital flows

It is evident that only portfolio equity had a positive and significant effect on economic growth. Remittance, to a limited extent, exerts a weak positive effect on economic growth. If policies are to be aimed at stimulating growth in the economy and attracting foreign capital, Kenya is best advised to focus more on attracting portfolio equity, which at present is relatively low, and to some extent remittance through policies that promote the inflow of these types of capital flows. The overall weak long-run relationship between capital flows and economic growth in Kenya may reflect uncertain business environment due to political instability and the frequent terrorist attacks. Hence, efforts to stabilize the political atmosphere and curtail the terrorism will go a long way to stimulate both economic growth and capital inflows. The recent trade bloc established between North Africa, East Africa and Southern Africa would help attract investment into Kenya, being a major player in the Eastern African bloc. However, such benefits would also depend on a stable political environment and affordable transfer rates into the country.

This study has covered five capital flows and presented the study using the ARDL bounds testing approach for a time-series dataset. Further studies can benefit by updating the dataset to show if the recent disruptions to economies around the world due to the covid-19 Pandemic would impact on capital flows effect on economic growth of Kenya.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The savings gap is expressed as ‘S-I’ and refers to the difference between domestic savings (S) and domestic investment (I).

2. The external financing gap is expressed as ‘X-M’ and refers to the difference between imports (M) and exports (X). This has to do with the interaction between countries on trade.

3. The fiscal gap is expressed as ‘G-T’ and refers to the difference between government expenditure and government income (taxation).

4. Refer to Easterly (2003) for a detailed account of this process.

References

- Abala, D. O. (2014). Foreign direct investment and economic growth: An empirical analysis of Kenyan data. DBA Africa Management Review, 4(1), 62–24.

- Acosta, P., Calderón, C., Fajnzylber, P., & Lopez, H. (2008). What is the impact of international remittances on poverty and inequality in Latin America? World Development, 36(1), 89–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.02.016

- Adams, S. (2009). Foreign direct investment, domestic investment and economic growth in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Policy Modeling, 31(6), 939–949. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpolmod.2009.03.003

- Adegbite, E. O., Ayadi, F. S., & Felix Ayadi, O. (2008). The impact of Nigeria's external debt on economic development. International Journal of Emerging Markets, 3(3), 285–301. https://doi.org/10.1108/17468800810883693

- Adenutsi, D. E., Aziakpono, M. J., & Ocran, M. (2011). The changing impact of macroeconomic environment on remittance inflows in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Academic Research in Economics, 3(2), 136–167.

- Adeola, O., & Aziakpono, M. (2017). The relative contribution of alternative capital flows to South Africa: An empirical investigation. Journal of Economic and Financial Sciences, 10(1), 47–68. https://doi.org/10.4102/jef.v10i1.4

- Adeola, O. O. (2017). Foreign capital flows and economic growth in selected sub-Saharan African economies [ PhD Dissertation]. Stellenbosch University.

- Adjasi, C., Abor, J., Osei, K. A., & Nyavor‐Foli, E. E. (2012). FDI and economic activity in Africa: The role of local financial markets. Thunderbird International Business Review, 54(4), 429–439. https://doi.org/10.1002/tie.21474

- Aggarwal, R., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Pería, M. S. M. (2011). Do remittances promote financial development? Journal of Development Economics, 96(2), 255–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2010.10.005

- Ait Benhamou, Z., & Cassin, L. (2021). The impact of remittances on savings, capital and economic growth in small emerging countries. Economic Modelling, 94(C), 789–803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2020.02.019

- Aizenman, J., Jinjarak, Y., & Park, D. (2013). Capital flows and economic growth in the era of financial integration and crisis, 1990–2010. Open Economies Review, 24(3), 371–396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-012-9247-3

- Alfaro, L., Chanda, A., Kalemli-Ozcan, S., & Sayek, S. (2004). FDI and economic growth: The role of local financial Markets. Journal of International Economics, 64(1), 89–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1996(03)00081-3

- Alfaro, L., Chanda, A., Kalemli-Ozcan, S., & Sayek, S. (2006). How does foreign direct investment promote economic growth? Exploring the effects of financial markets on linkages. NBER Working Paper, 12522. https://doi.org/10.3386/w12522

- Aziakpono, M. J. (2013). Financial integration and economic growth: Theory and a survey of evidence. Journal for Studies in Economics and Econometrics, 37(3), 61–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/10800379.2013.12097258

- Baharumshah, A. Z., & Thanoon, M. A. (2006). Foreign capital flows and economic growth in East Asian Countries. China Economic Review, 17(1), 70–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2005.09.001

- Bailliu, J. N. (2000). Private capital flows, financial development, and economic growth in developing countries. Bank of Canada Working Paper 2000-15. Bank of Canada.

- Balasubramanyam, V. N., Salisu, M., & Sapsford, D. (1999). Foreign direct investment as an engine of growth. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development, 8(1), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638199900000003

- Barajas, A., Chami, R., Fullenkamp, C., Gapen, M., & Montiel, P. (2009). Do workers' remittances promote economic growth? Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

- Bayale, N., Traore, F., Diarra, S., & Maniraguha, F. (2022). Endogenous threshold effects and transmission channels of foreign aid on economic growth: Evidence from WAEMU zone countries. Transnational Countries Review, 14(1), 77–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/19186444.2022.2028541

- Beine, M., Docquier, F., & Rapoport, H. (2001). Brain drain and economic growth: Theory and evidence. Journal of Development Economics, 64(1), 275–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3878(00)00133-4

- Bengoa, M., & Sanchez-Robles, B. (2003). Foreign direct investment, economic freedom and growth: New evidence from Latin America. European Journal of Political Economy, 19(3), 529–545. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0176-2680(03)00011-9

- Bordo, M. D., Meissner, C. M., & David Stuckler, D. (2010). Foreign currency debt, financial crises and economic growth: A long-run view. Journal of International Money and Finance, 29, 642–665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jimonfin.2010.01.002

- Borensztein, E., De Gregorio, J., & Lee, J. (1998). How does foreign direct investment affect economic growth? Journal of International Economics, 45(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1996(97)00033-0

- Burnside, C., & Dollar, D. (2000). Aid, policies, and growth. American Economic Review, 90(4), 847–868. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.90.4.847

- Carkovic, M. V., & Levine, R. E., Does Foreign Direct Investment Accelerate Economic Growth? (June 2002). Does Foreign Direct Investment Accelerate Economic Growth? Working Paper, Available at https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.314924

- Catrineseu, N., Leon Ledesma, M., Piracha, M., & Quillin, B. (2009). Remittances, Institutions, and Economic Growth. World Development, 37(1), 81–92.

- Chami, R., Fullenkamp, C., & Jahjah, S. 2003. Are immigrant remittance flows a source of capital for development? IMF Working paper WP/03/189. International Monetary Fund.

- Checherita-Westphal, C. D., & Rother, P. (2010). The Impact of high and growing government debt on economic growth: An empirical investigation for the Euro Area. (August 16). ECB Working Paper No. 1237. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1659559

- Chenery, H. B., & Strout, A. M. (1966). Foreign assistance and economic development. The American Economic Review, 56 4 (part1), 679–733.

- Chinn, M. D., & Ito, H. (2006). What matters for financial development? Capital controls, institutions, and interactions. Journal of Development Economics, 81(1), 163–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2005.05.010

- Chowdhury, M. B. (2011). Remittances flow and financial development in Bangladesh. Economic Modelling, 28(6), 2600–2608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2011.07.013

- Claudio-Quiroga, G., Gil-Alana, L., & Maiza-Larrarte, A. (2022). The impact of China’s FDI on economic growth: Evidence from Africa with a long memory approach. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 58(6), 1753–1770. https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2021.1926233

- Dalgaard, C.-J., & Hansen, H. (2001). On aid, growth and good policies. The Journal of Development Studies, 37(6), 17–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/71360108110.1080/713601081

- De Mello, L. R. (1997). Foreign direct investment in developing countries and growth: A selective Ssrvey. The Journal of Development Studies, 34(1), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220389708422501

- Driffield, N., & Jones, C. (2013). Impact of FDI, ODA and migrant remittances on economic growth in developing countries: A systems approach. The European Journal of Development Research, 25(2), 173–196. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2013.1

- Durbarry, R., Gemmell, N., & Greenaway, D., 1998. New evidence on the impact of foreign aid on economic growth (No. 98/8). CREDIT Research paper.

- Durham, J. B. (2004). Absorptive capacity and the effects of foreign direct investment and equity foreign portfolio investment on economic growth. European Economic Review, 48(2), 285–306. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0014-2921(02)00264-7

- Easterly, W. (2003). Can foreign aid buy growth? The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17(3), 23–48. https://doi.org/10.1257/089533003769204344

- Elbadawi, I., & Rocha, R. R. (1992, November). Determinants of Expatriate Workers' Remittances in North Africa and Europe. Country Economics Department, World Bank WPS 1038.

- Fajnzylber, P., & Lopez, J. H. (2007). The development impact of remittances in Latin America. In P. Fajnzylber & J. H. López (Eds.), Remittances and Development: Lessons from Latin America. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- Fayissa, B., & Nsiah, C. (2010). The impact of remittances on economic growth and development in Africa. The American Economist, 55(2), 92–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/056943451005500210

- Fosu, A. K. (1996). The impact of external debt on economic growth in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Economic Development, 21(1), 93–108.

- Giuliano, P., & Ruiz-Arranz, M. (2009). Remittances, financial development, and growth. Journal of Development Economics, 90(1), 144–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2008.10.005

- Government of the Republic of Kenya. (2007). A globally competitive and prosperous Kenya. Assessed September 5, 2015. http://www.vision2030.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Vision2030_Popular_version_final2.pdf

- Gupta, S., Pattillo, C. A., & Wagh, S. (2009). Effect of remittances on poverty and financial development in sub-Saharan Africa. World Development, 37(1), 104–115.

- Hansen, H., & Tarp, F. (2001). Aid and growth regressions. Journal of Development Economics, 64(2), 547–570. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3878(00)00150-4

- Headey, D. (2008). Geopolitics and the effect of foreign aid on economic growth: 1970–2001. Journal of International Development, 20(2), 161–180. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.1395

- Hussain, S., & Rahman, M. H. (2022). Are foreign aid and economic growth positively related? Empirical evidence from Bangladesh. Bangladesh Journal of Multidisciplinary Scientific Research, 5(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.46281/bjmsr.v5i1.1611

- Ikram, M., Xia, W., Fareed, Z., Shahzad, U., & Rafique, M. Z. (2021). Exploring the nexus between economic complexity, economic growth and ecological footprint: Contextual evidences from Japan. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments, 47, 101460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seta.2021.101460

- Imran, M., Zhong, Y., Moon, H. C., Zhong, Y., & Moon, H. C. (2021). Nexus among foreign remittances and economic growth indicators in south Asian countries: An empirical analysis. Korea International Trade Research Institute, 17(1), 263–275. https://doi.org/10.16980/jitc.17.1.202102.263

- Lanouar, C., & Shahzad, U. (2021). Terrorism and capital flows: The missed impact of terrorism in big cities. Applied Economics Letters, 28(18), 1626–1633. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2020.1861185

- Lartey, E. K. (2013). Remittances, investment and growth in sub-Saharan Africa. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development, 22(7), 1038–1058. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638199.2011.632692

- Levine, R., & Zervos, S. (1998). Stock markets, banks, and economic growth. American Economic Review, 88(3), 537–558. https://www.jstor.org/stable/116848?seq=1

- Lu, S., & Ram, R. (2001). Foreign aid, government policies, and economic growth: Further evidence from cross-country panel data for 1970-1993. Economia Internazionale/International Economics, 54(1), 15–29. https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:ris:ecoint:0223

- M’Amanja, D., & Morrissey, O. (2006). Foreign aid, investment and economic growth in Kenya: A time series approach. CREDIT Research paper 06/05. University of Nottingham.

- Mundaca, B. G. (2009). Remittances, financial markets development and economic growth: The case of Latin America and the Caribbean. Review of Development Economics, 13(2), 288–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9361.2008.00487.x

- Murshid, A. P., & Mody, A. 2011. Growth from international capital flows: The role of volatility regimes. IMF Working Paper WP/11/90, International Monetary Fund.

- Mwangi, B. N., & Mwenda, S. N. (2015). The effect of international remittances on economic growth in Kenya. Microeconomics and Macroeconomics, 3(1), 15–24. http://article.sapub.org/10.5923.j.m2economics.20150301.03.html

- Ndikumana, L., & Boyce, J. (2003). Public debts and private assets: Explaining capital flight from sub-Saharan African countries. World Development, 31(1), 107–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(02)00181-X

- Ndung’u, N., Thugge, K., & Otieno, O. (2011). Unlocking the future potential for Kenya: The Vision 2030. Office of the Prime Minister Ministry of State for Planning, National Development and Vision, 2030. http://www.foresightfordevelopment.org/sobipro/55/1266-unlocking-the-future-potential-for-kenya-the-vision-2030

- Ngeny, K. L., & Mutuku, C. M. (2014). Impact of Foreign Direct Investment Volatility on Economic Growth in Kenya: EGARCH Analysis. Economics, 3(4), 50–61. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.eco.20140304.11

- Nyamongo, E. M., Misati, R. N., Kipyegon, L., & Ndirangu, L. (2012). Remittances, financial development and economic growth in Africa. Journal of Economics and Business, 64(3), 240–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconbus.2012.01.001

- Nyamwange, M. 2009. Foreign direct investment in Kenya. MPRA paper 34155. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/34155/

- Nyasha, S., & Odhiambo, N. M. (2022). The impact of remittances on economic growth: Empirical evidence from South Africa. International Journal of Trade and Global Markets, 15(2), 254. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTGM.2022.121457

- Ocharo, K. N., Wawire, W., Kosimbei, G., & Ng’ang’a, T. K. (2014). Private capital inflows and economic growth in Kenya. International Journal of Development and Sustainability, 3(4), 810–837. www.isdsnet.com/ijds

- Ojiambo, E., & Ocharo, K. N. (2016). Foreign capital inflows and economic growth in Kenya. International Journal of Development and Sustainability, 5(8), 367–413. www.isdsnet.com/ijds

- Pagano, M. (1993). Financial markets and growth: An overview. European Economic Review, 37(2), 613–622. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-2921(93)90051-B

- Pal, S., Villanthenkodath, M. A., Patel, G., & Mahalik, M. K. (2022). The impact of remittance inflows on economic growth, unemployment and income inequality: An international evidence. International Journal of Economic Policy Studies, 16(1), 211–235. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42495-021-00074-1

- Pattillo, C. A., Poirson, H., & Ricci, L. A. (2002). External debt and growth. IMF Working Papers 02/69. International Monetary Fund.

- Pesaran, M. H., Shin, Y., & Smith, R. J. (2001). Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 16(3), 289–326. https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.616

- Pradhan, G., Upadhyay, M., & Upadhyaya, K. (2008). Remittances and economic growth in developing countries. European Journal Development Research, 20(3), 497–506. https://doi.org/10.1080/09578810802246285

- Rehman, N. U., & Hysa, E. (2021). The effect of financial development and remittances on economic growth. Cogent Economics & Finance, 9(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2021.1932060

- Reinhart, C. M., & Rogoff, K. S. (2010, May). Growth in a time of debt. American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings, 100, 573–578. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.100.2.573

- Reisen, H., & Soto, M. (2001). Which types of capital inflows foster developing‐country growth? International Finance, 4(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2362.00063

- Shahzad, U., & Qin, F. (2019). New terrorism and capital flight: Pre and post nine eleven analysis for Asia. Annals of Economics and Finance, 20(1), 465–487. http://down.aefweb.net/AefArticles/aef200118ShahzadQin.pdf

- Soto, M. (2000). Capital flows and growth in developing countries: Recent empirical evidence. OECD Development Centre.

- World bank. (2014). World bank global financial development database (GFDD).

- Yoshino, N., Kaji, S., & Asonuma, T. 2015. Comparison of static and dynamic analyses on exchange rate regimes in East Asia. ADBI Working Paper Series, No. 532. Asian Development Bank Institute