Abstract

The objective of this paper was to establish challenges and benefits on formalisation in South Africa using a qualitative approach. To meet the objective, 15 interviews were carried out with owners of small businesses that had just formalized in Johannesburg and Pretoria. This study contributes to the existing knowledge on small business formalisation by bringing evidence from formalised businesses. The research does so through asking unique questions that cannot be answered quantitatively. Using themes for analysis, the study found conditional formalisation, high levels of bureaucracy, unsustainable fees, information asymmetry, credit or capital unavailability and corruption as key challenges being faced by emerging entrepreneurs. In addition, the study also identified increased chances to benefit from BEE, improved access to information to supply the public sector, improved chances of securing credit, increased credibility of the business and better access to markets as the benefits that entrepreneurs derive from formalisation. This study recommends that informal businesses be supported through skills training initiatives and expanded credit opportunities so that they can be of better size and capacity to formalise.

1. Introduction

There is a rising consensus that informal businesses should be formalised or mainstreamed (Devey et al., Citation2006; International Labour Organization (ILO), Citation2014; Maduku & Kaseeram, Citation2019; De Soto, Citation1989; World Bank, Citation2015). However, in the debate, there are two stakeholders that are overemphasized, employees and the government. Arguments for formalisation point around decent work, decent wages and the broadening of government revenue, but little is talked about the interests of business owners. The informal sector comprises those who employ themselves and those who are employed by informal firms but not those that are informally employed by formal firms (Devey et al., Citation2006). In earlier arguments on determinants of informal-sector participation, there were iterations that businesses informalise their operations because they do not want to pay tax (De Soto, Citation1989), but this has massively shifted especially in the context of African economies. This is so because some operate informal businesses as they need to survive (survivalists), and it is convenient for them as they cannot find a job or do not have large capital to formalise.

There are arguments that informal businesses already pay taxes, in the form of value-added tax (VAT), and they do not even claim back because they do not have VAT registration numbers. On another side, the link between informal and formal firms makes it clear that informal small businesses are already contributing much to economies, but it is the governments that are not doing enough in making sure that capacity of these informal small businesses is boosted, and it is convenient and less costly for small businesses to operate (Maduku & Kaseeram, Citation2019). Informal small businesses through self-employment and having employees do create demand for formal firms who then grow and pay other taxes to governments that are not paid by informal firms. Informal small businesses that offer jobs to the unemployed contribute to creating demand in the economy through providing purchasing power to the poor and marginalized. However, because governments do not involve the interests of these informal small business owners, they respond by trying to evict these informal traders from the streets (Maduku & Kaseeram, Citation2019). Given that they do not evict them, they just turn a blind eye on these traders through not improving the infrastructure they use for their business or offering other services that facilitate the growth of these informal traders (Bargain and Kwenda Citation2011).

The endeavor to change the face of informal small businesses is a complex multidimensional process, where policymakers will have to understand and acknowledge the nature of eclectic categories of informal workers or small businesses and their constraints as well as their potential to contribute to overall GDP (Maduku & Kaseeram, Citation2019). Governments have been overemphasizing the contribution of informal small businesses to gross domestic product (GDP) after their formalisation but are failing to acknowledge the interests of these informal small business owners. The policymakers assume that informal business owners only want to survive without a growth objective. On the outset, if businesses do have growth objectives, the South African government has not been making enough efforts to make it lucrative and convenient for small businesses, especially on costs and procedures that are required for a business to be formally registered (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM), 2017).

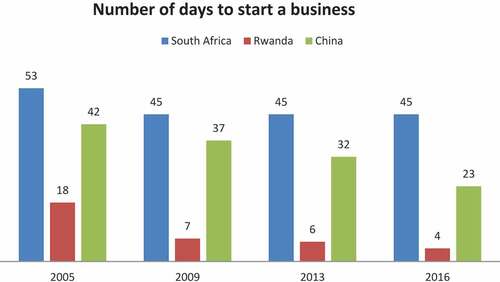

Figure explicitly shows how South Africa is still making it difficult for businesses to start and register. The choice of countries used was motivated by the fact that Rwanda is the fastest growing economy in Africa currently and China on the global arena at least in the past decade. As at 2016, businesses needed only 4 days to be registered to start operations in Rwanda, whilst one needs 45 days to do the same in South Africa. On the time required securing an operating license, a business spends 37 days in South Africa, whilst it takes only 17 days for the same process in Rwanda (World Bank, Citation2018).

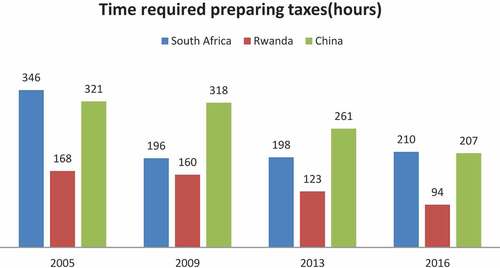

Statistics shown by Figure indicate that business people use more hours in South Africa to prepare taxes as compared to Rwanda and China as at 2016. The information presented above explains that it is a cumbersome process to administer taxes in South Africa compared to other countries involved. The assumptions by De Soto (Citation1989) may hold in the case of South Africa in the sense that some businesses might choose to operate informally only because it is difficult and time consuming to process taxes.

The importance of this study rests on the importance of small businesses in South Africa since they account for an estimated 60% of employment creation in the country as well as accounting for 90% of formalised businesses. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM;) also explicitly indicates that 36% of the South African GDP is contributed by small businesses. However, South Africa is faced with a high failure rate of small businesses more than those that are being established. This actually means that South Africa has negative growth of businesses as a result of high failure rate, yet little is being done from the policy front, days to process taxes are still so many and the processes to start a business are still cumbersome as shown in Tables . Statistics released by Statistics South Africa (2017) indicate that there are more than 6 million informal small businesses in South Africa against only an average 4.2 million formalised businesses. The reason for this huge disparity is not known and that is what the current work looked at using interviews from formalised firms.

Table 1. Participants of the study

Table 2. Procedures for analysis

Motivated by the huge gap between formalised and informalised small businesses in the country, the paper contributes through unpacking factors that make some businesses formalise their businesses, while others remain informalised. The current research conducted interviews with small business owners who had already graduated from being informal to becoming formalised and that gives more insights than what can be explained by quantitative data. Also, the research will contribute by unpacking what needs to be done, especially by the government from the legislative perspective in order to make it convenient and encouraging for small businesses to formalise. It has been observed in Figures that South Africa still has stringent and cumbersome regulations as opposed to other countries that saw improvements in terms of informal business formalisation.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2.0 discusses the populous schools of thought on the existence of the informal sector in an economy followed by some of the recent literature. Next is Section 3.0, which is the methodology section highlighting all the steps and procedures taken by the author to gather, clean and analyse the data. What follows after the methodology section is Section 4.0 with presentation and discussion of the paper results. Lastly, the paper concludes with Section 5.0 where it also presents some recommendations to government officials and small business owners.

2. Literature review

The building blocks of theories that inform the transition or formalisation of businesses that operate in the informal sector are at least grounded on three schools of thought which are the legalist school by De Soto (Citation1989), the structuralist school by Portes et al. (Citation1989) and dualist school argued by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) in 1972 (International Labour Office, Citation1973). First, this paper will start by discussing the legalist school of thought which argues that firms choose to operate informally because they want to avoid getting taxed and operating under watch from the government rules and regulations (De Soto, Citation1989). The legalist school labels the activities that happen outside the government regulations as the shadow economy. This is despite the fact that the trading that informal sector players are done in public space and most of them are not involved in illegal goods. Also, there have been arguments that there is a link between the informal economy and the formal sector, and the informal sector players already pay value-added tax (VAT) when they procure their wares from the formal sector. De Soto (Citation1989) also argues that some of the businesses that operate in the informal economy are as a result of governments’ red tape in processing the registrations of businesses. The legalist school also mentions the long queues that entrepreneurs have to endure in order to register their businesses or pay taxes (Devey et al., Citation2006). Arguing for the transition of businesses from operating informally, the legalist school advocates that governments should deal with red tape and create situations that cut costs of registering and processing taxes so that more businesses can be encouraged to join the formal sector.

Second, the dualist school of thought by the ILO in 1972 departs from the legalist school in the sense that it views the participation of businesses in the informal economy as a choice of last resort (International Labour Office, Citation1973). It argues that people choose to work in the informal sector because they are not competent enough to find jobs in the formal sector. This school of thought views the informal sector as a hive of incompetent people who are less educated and less skilled. So, the activities that happen in the informal economy are argued to be separate activities that are not linked from the formal sector. However, the dualist school of thought might have overlooked the fact that informal sector players procure their inputs or their wares from formal sector businesses; hence, it will be amiss to argue that there is no linkage between the informal sector and the formal sector. It will be also wrong to argue that the informal and the formal sector are two distinct sectors with no linkage or relationship, but the only difference between these is that the other pays all taxes, whilst the other one does not. The other one is registered and has higher chances of accessing credit and make bigger profits, but the other one has fewer chances of such benefits (Menya 2009). In South Africa, graduate unemployment is averaging 7% of total unemployment (Statistics South Africa 2018). That statistic informs us that the informal sector becomes a safety net for those graduates who cannot secure employment, and some of them can actually come to a point of creating their own jobs, but because they lack capital or it is costly to formalise in the short run, they may choose to operate informally. It will be argued below in this paper that the persistence of informal sector activities is exacerbated by low economic growth patterns experienced by the South African economy failing to absorb more job seekers into the labour market and also the rigidity of the system on simplifying formalisation.

Lastly, the structuralist school by Portes et al. (Citation1989) views the informal economy as a subordinate of the formal economy. In that context, the informal economy serves to reduce the input costs of production for large formal businesses. The informal economy feeds informal labour to formalised businesses who seek to cut down costs of labour so as to maximize their profits. For example, a formalised company might choose not to employ permanent workers to offload and do the packaging but employ people as and when they are needed, and these people will not be having any formalised contract of employment with the company. Devey et al. (Citation2006) argue that the growth of profits of formalised businesses depends on the size of the informal sector. The more the people are willing to work in the informal sector, the more the profits the formalised businesses make. Janneke et al. (Citation2011) communicate that the formal businesses subcontract the most labour-intensive stage of production to the informal economy and save on labour costs. So, the structuralist school suggests that there are two separate structures of the economy forming a link where both structures benefit from each other.

The meeting point of the three schools of thought that attempt to explain the informal economy rests on the fact that they all agree that the informal economy is inferior compared to the formal economy. The structuralist approach actually identifies the informal economy as a subordinate sector to the formal economy where there are fewer skills that can be exploited by formal firms to save costs and push high profits. This is exactly what the dualist school also perceives about the informal economy. The dualist school of thought views the informal economy as a sector that accommodates only less skilled people who are only looking for survival. This then means that the dualist school identifies the informal economy as a survivalist hub. According to the International Labour Office (Citation1973), workers who participate in the informal sector can only escape poverty if the businesses they are working for, mainstream or transit into the formal economy. Finally, the legalist school agrees with the dualist and structuralist on identifying the informal sector based on the perspective that the informal sector as a sector for criminals who avoid rules and regulations. It argues that the people who participate in the informal economy are mostly tax evaders and those that are frustrated by the government’s red tape. All these schools agree on the fact that society will be better if there are more formalised firms than those that are informal since that will increase government revenue and increase the success rate of small businesses as well as the provision of decent jobs to employees.

3. Methodology

In this study, the qualitative research design, which is located within interpretivist paradigm, was employed. The interpretivist argues that human beings differ from the material world, and thus, the methods used to investigate human thoughts and feelings must be in accordance with this paradigm. The rationale behind the qualitative approach is that it embraces the ontological assumption of multiple truths or multiple realities, i.e., persons understand reality in different ways that reflect individual perspectives as opposed to the quantitative approach, a positivist paradigm which ignores differences and focuses on common objective reality (Kumar, Citation2011). The qualitative research approach is based on the subjective and considers human realities instead of just the facts and typically only a small sample is required; hence, it was considered to be appropriate to this study since registered business owners were interviewed. To collect information from the small businesses, the researcher used an open-ended questionnaire to get detailed accounts helpful enough to reach the research objectives.

3.1. Sampling and data collection

In order to gather primary data, interviews were conducted using an open-ended questionnaire. The semi-structured interviews facilitated for interactions with the small businesses that were identifiedMerriam, Citation2009). The interviews were uniform in the sense that the same interview questionnaire was used although some other probing questions were asked so as to get deep knowledge about small businesses formalisation (Pike et al., 2018). The type of data and the type of small businesses this research was targeting made it difficult for a probability sampling technique because it would have consumed more time and resources. This led the adoption of snowball sampling technique which is a non-probability technique. This approach was deemed appropriate for it was difficult to identify businesses that transited from being informal to formal; hence, once the first one was found, then it became easier to ask the first key informant to introduce us to another informant that had also formally registered a business. This approach is based on the notion that entrepreneurs engage in networking with their peers and learn valuable lessons therefrom; hence, those who started operating in the informal sector graduated to the formal sector through seeking guidance from one another. Initially, we had intended interviewing up to 30 such key informants; however, by the time we interviewed the fifteenth person, we noticed that the same themes kept coming; hence, we realised the saturation point was reached and thus terminated the further collection of data.

According to Pheko (Citation2014), Moloto et al. (Citation2014), and Andrews (Citation2007), any respondents that range from 10 to 30 are sufficient for a research that collects data through interviews. On another note, Pike et al. (2018) and Dworkin (Citation2012) try to be more specific and bring the gap closer as they argue that a proper sample ranges between 25 and 30. Therefore, this study intended to choose 30 participants using the snowball technique to identify the respondents, but due to data saturation, 15 participants were interviewed. The sample was limited only to small businesses that started by operating in the informal sector and then graduated into the formal economy. This means that those that started operating in the formal economy from the first day of operation were excluded from the sample. gives an illustration of the participants involved in the study.

3.2. Coding technique and analysis

To analyse the data, themes and patterns in the data were chosen on the basis of the theoretical and empirical literature discussed above. The research adopted thematic analysis technique to draw conclusions from the data collected (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). In order to get best results from the thematic technique, the researcher had to go through three stages which are, first, descriptive coding which involves reading through the transcript whilst highlighting the most important information at the same time defining the descriptive codes to the data. The second stage carried out was the interpretive coding of the data involving clustering the codes and sifting out the meaning of the clusters. The last session on second stage was the application of the interpreted codes to the data. Lastly, overarching themes of the whole dataset from which key themes of the data were derived and identified (King & Horrocks, Citation2010). The stages described above are shown in Table .

3.3. Ethical considerations

In order to go into the field to collect data, the researcher applied for an ethical clearance certificate which was awarded by the research committee of the University of Zululand. The certificate number is UZREC 171110-030 PGD 2017/197. Prior to issuing the certificate, the committee had to assess the level of risk the research was ranked, and it was categorised as a medium-risk research. The researcher had to put an undertaking that participants will be involved based on their voluntary agreement to respond and their anonymity would be preserved as well. To add, the research area where the data was collected is a multi-lingual area; hence, the researcher had questions prepared in three languages, namely, (1) IsiZulu, (2) Setswana, and (3) English. Respondents would be asked to respond in a language they preferred for the benefit of their full expression and deeper responses for the research. Lastly, the respondents were given an informed consent at the beginning of the interview so that they would sign if they agreed with the terms stated on the consent letter.

4. Results and finding discussion

The research findings to be presented here came from the interview proceedings that were carried out by the researcher with formalised small businesses in Johannesburg/Pretoria in South Africa. To capture well the responses from the participants, the researcher did voice recordings of the respondents as well as capturing notes from observations in the visited areas.

4.1. Discussion of themes from the data

4.1.1. THEME 1: CHALLENGES HAMPERING FORMALISATION

The challenges that frustrate efforts by most governments to have huge volumes of small businesses to formalise differ from one country to another and differ from policies implemented per country or in a country (Fajnzylber et al., Citation2011). It must also be recognized that there are no uniform policies that can be implemented by countries to reduce the informal sector. The participants were asked of the challenges they faced when they were in the process of moving from the informal sector, and the verbatim quotes of their responses are in the sub-themes below.

5. Sub-theme: 1.1 high levels of bureaucracy

According to the interviewed participants, entrepreneurs wanting to register their businesses are faced with huge bureaucratic “red tape” (hurdles) which are quite onerous to fulfill. Through literature, the study established that instead of the procedures to be halved, they have actually increased (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM)). In as much as the government might justify such policies, they have been cited by the entrepreneurs as one of the major stumbling blocks to improved rates of formalisation. This research included the verbatim quotes of the responses from contacted small business owners in South Africa.

Participant 2: Uuum what I can say is that there is a lot of paperwork to be done and the things that needs to be done are too much and it is very discouraging because it can take you even more than a month yet all the work that you are supposed to be doing no one will be doing it so you will be losing money because you want to register your business.

Participant 6: For me there was no much challenges except the fact that the process took longer than I expected.

Participant 9: I did not start by operating in the informal so I would say much on that but what I can say is that most challenges I faced were the processes that one needs to do inorder to be recognized as a legit business in South Africa. It took me close to a month to have all my papers in place. Also the money they wanted was just too much for someone who was starting small without a lot of money.

In the category of bureaucracy when cited to be a problem, there are different problems faced by business people in that category. According to participant 2, it was the paper work that needed to be done in order for a company to be fully recognized from environmental laws, tax laws and labour laws. The participant also cited the fact that the process is discouraging and that might justify why so many small businesses end up not completing the process or choose to stay operating informally. On the other side, in as much as participant 6 was clear to say that there was no a lot of challenges that were encountered, there were still concerns to the fact that the process was too long as expected by the business community. The results of our study confirm the findings of Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM;) and the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) (2005). The DTI reported the problem of more institutions dealing with similar issues, and small businesses have to move from one institution to another rather than combining them into one.

6. Sub-theme: 1.2 unsustainable fees and processes

A significant percentage of emerging small businesses in South Africa belong to the micro element of business size, and these small businesses do not make much as a result of stiff competition from bigger businesses and lack of important skills needed for sustainable businesses (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM)). Very few small businesses are also able to meet the costs of formalisation, and if they do meet them, it does eat up the bigger portion of the savings, making it difficult for the business to expand and survive in a formalised setup. The participants contacted in this research articulated that the fees that are being paid by entrepreneurs to move from the informal sector to the formal sector are too much for them, and it discourages businesses operating in the informal sector to mainstream. According to participant 1, the fees that were requested throughout the whole process were too much for the business.

Participant 1: The money that I was asked to pay for all the processes is too much and I think that is why other people will just do not do it. Also the people that do that they delay a lot, it takes time and you will be forced to give them something for your things to be fast fast.

The same sentiments shared by participant 1 were also echoed by participant 8, citing that the license fees were exorbitant especially for small businesses that were trying to grow their businesses.

Participant 8: The license fees were very high for me as well and the processes took longer to the point that I had to pay something for my things to be sorted.

It is the finding of this research that higher compliance fees hinder or discourage more informal businesses from graduating into the formal sector. We can argue further that, if South Africa is to witness a significant portion of informal businesses migrating from informal into the formal sector, there needs to be a policy review in line with the compliance fees as the current setup is discouraging formalisation.

7. Sub-theme: 1.3 information asymmetry

This research recorded that a lot of informal small businesses that are expected by the government to mainstream their businesses are not aware of the processes that need to be undertaken. It is evident that the government is not doing enough to make sure that informal small businesses are well informed about where to get help and business advice. On the other side, the government facilitated incubation centres to mentor small businesses so that they are capacitated to have important business skills to improve business sustainability. In as much as those incubation centres had played a huge role in making sure that small businesses are en-skilled, they only deal with businesses that have already formalised and their number nationwide is unable to meet the demand of small businesses that are in need of the service. Also, despite the above stated facts, the process is marred with huge paperwork that needs to be done after a very tight scrutiny in recruitment, and the process can be very long. Despite all the positives of all these government initiatives and contributions by other players, the entrepreneurs are still much not abreast as to what is expected of them.

Participant 5: With me it was mostly that I had no much information on what I was supposed to have so they kept sending me back and forth. So it took me longer than I should have done. And also I will say the processes are too much and you end up spending a lot of money.

According to participant 5, it took the entrepreneurs longer in registering, making the process cumbersome because there is no enough information at their exposure. The fact that information is not there to all who need it made people to spend more money as they go to departments more than they were supposed to have done. It then becomes a very big challenge because the time taken to register become frustratingly long, and the process will become costly as opposed to if efforts were made to make sure that entrepreneurs are well informed.

Participant 7 also confirmed the challenges that were faced by entrepreneurs when they made efforts to formalise their businesses.

Participant 7: The problem was information on the things and processes to be done. In my case I struggled until I found this other guy from SETA and he advised me about how I could potentially grow my business and what I needed to do.

Information is not reaching many small businesses about opportunities that are available from government that can help us. There are organisations and funding from government meant to help us small businesses but very few people are aware. So they should improve on their communication tactics.

The two participants agree on the impact lack of information has when it comes to dampening the mainstreaming process. This calls for the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) to make structural changes as far as their communication policies to small businesses so that the needy entrepreneurs, especially those in the suburbs, are motivated to mainstream their businesses for them to grow and create sustainable livelihoods to the owners and those they employ.

8. Sub-theme: 1.4 credit unavailability

Since the dawn of democracy in 1996, the Government of South Africa has put in place funding channels to help small businesses grow as well as encourage informal-sector players to formalise. The government put in place the Small Enterprise Development Agency (SEDA), the Department of Small Business and the Department of Trade and Industry together with a wide range of public–private incubation hubs across the country to help small businesses to grow and become sustainable. However, the funding available has proved to be very insignificant to service small businesses that are estimated to be above 2.6 million (both formal and informal). According to interviewed small business owners in Johannesburg/Pretoria area, the challenge of lack of credit appeared to be one of the big problems hindering formalisation progress.

Participant 3: I think they should give small businesses enough time to grow and save more money to grow because it is very difficult for us black South Africans to get loans from banks you know. So its hard my brother but we will just keep trying.

Participant 14: One of my very biggest challenges was money because I could see the potential in my business and I knew if I could get money I was going to make it but it is very difficult to get funding out there and sometimes you think its us black people because white people are doing very well in South Africa. I do not know how many times I applied to my bank to get a business loan but I could not meet some of their demands. It took me very long to get the money I used to kick start and grow my business.

Participant 15: I am sure you know that for a business to formalise it must increase its business and to do that we need money. Today if you go to a bank, they need collateral security but we were very small entrepreneurs then with no assets. So the issue of funding is a big headache all the time, ask everyone they will tell you how they struggle to get loans.

According to the 2014 Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) report, financial exclusion is one of the big contributors towards business failure in South Africa. This study confirms the same since of lack of credit is a predicament when it comes to business mainstreaming. In as much as the government has put in place measures to improve business funding, the budgets that are allocated to small businesses are still very small. According to participant 15, there is a structural problem that is taking long to be solved in South Africa. In as much as financial institutions try to be risk averse, the request of collateral security from an emerging business person who only has an idea is one major problem worsening the problem of financial inclusion against small businesses. The Government of South Africa needs to make a bold step of becoming a guarantor to such loans or negotiate with financial institutions to consider other factors and remove the issue of assets which emerging entrepreneurs seem not to have but business ideas.

9. Sub-theme: 1.5 corruption

South Africa ranks very high as one of the most corrupt countries in the world (Transparency International 2017), and this has also affected informal small businesses endeavoring to mainstream their businesses. Government and other private institutions’ members of stuff take advantage of long frustrating processes that are in place to be followed by small businesses. When registering, officials demand to be paid so that they can speed up processes. In as much as this can be a benefit to some especially those who can afford to pay bribes, it has emerged as a challenge for most entrepreneurs as this adds costs.

Participant 1: Also the people that do that they delay a lot, it takes time and you will be forced to give them something for your things to be fast.

Participant 4: To get some licenses you have to pay and to register you have to pay and there is also a lot of black tax (corruption) to pay on the way so its very expensive man.

9.1. Participant 7: the processes took longer to the point that I had to pay something for my things to be sorted

Taking from participants 1, 4 and 7, public officials in the country are contributing to the unwillingness of most informal traders to formalise their operations. Corruption has emerged as a sunk cost for small business owners who have interests to formalise their operations. If we are to see more willingness to formalise, law enforcement agencies in the country have to act on corruption.

9.1.1. THEME 2: BENEFITS OF FORMALISATION

The concept of informal business formalisation was popularised by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) in a bid to encourage and promote decent work (ILO 1972). Other advocates of informal-sector formalisation also stated different benefits to both the government and the business owners themselves. However, as mentioned and discussed in Theme 3 above, the formalisation process has lots of challenges that make it to follow a very slow pace. On the outset, the current study will unpack some of the identified benefits that black entrepreneurs enjoy in South Africa. This is a unique group of entrepreneurs in South Africa as they constitute the bigger portion of informalised entrepreneurs in South Africa as well as less performing entrepreneurs in the country (QLFS 2015).

10. Sub-theme: 1.1 increased chances to benefit from BEE

The South African government having noticed the high levels of inequality in the country with black entrepreneurs at the foot of the ladder introduced a policy meant to improve market access for black-owned businesses. The black economic empowerment has three categories where businesses belong to. The first one is the Exempted Micro Enterprises (EME). These are small businesses that have annual income of less than R10 million rand. The second is the Qualifying Small Enterprise (QSE) with income between R10 million and R50 million. The third and last is the Generic which is composed of businesses that have inflow of more than R50 million a year. All of the businesses that were interviewed for this study belong to the EME category. In order for a business to qualify for the BEE certificate or to score more points under the BEE policy, they have to be procuring or supplying to a black-owned business or a business that have a BEE certificate. According to the findings of our study, when a business formalises its operations, there is improvement of their chances of benefiting from the BEE policy either as a supplier or as a customer. The EME category is the easiest category to qualify as it does not require so much paper work except a written affidavit attesting that indeed the company is 51% owned by black people and that it gets income less than R10 million a year.

Participant 1 clearly stated that some of the benefits that the business is enjoying are government workshops, improved chances to supply the government, and more business coming from other black entrepreneurs who want to score more points.

Participant 1: There are also a lot of government workshops that we are invited to attend and they have been very helpful even for our businesses to qualify for BEE and other benefits from government.

Participant 4 also stated among the benefits that there are other black business that were procuring from the business mainly because they wanted to score high on BEE and that becomes an advantage to the business because it expands the sales and make the finances of the business to get stable.

Participant 4: Also I have managed to get business from other black owned businesses who want to qualify for BEE and that has helped my business to stay strong.

Participant 15: My business just received a BEE certificate for the Exempted Micro Enterpise (EME) and I could not have benefitted from that if I was still operating the way I was doing before I registered. At the moment I can supply government departments and other black businesses who also want to benefit from procuring from a black business especially the one of our size.

The three responses indicate that black entrepreneurs are benefiting from the current policy either directly as suppliers to government and other private businesses or customers to other private enterprises getting their scores better increasing their chances to get tenders.

11. Sub-theme: 1.2 improved access to information to supply the public sector

One of the challenges cited by the participants haunting small businesses especially in the informal sector is lack of information. However, when a business is formalised, there is evidence that the situation improves as businesses start to get invited by different government departments and other private stakeholders to benefit from different processes (Boly, Citation2018). Some of the businesses contacted by this study subscribe to different institutions that help small businesses including SEDA, SETA and other incubation centres across the country and that facilitate access to information for the benefit of small businesses. Below are the verbatim quotes from small business owners, stating improved access to information as one of the benefits after formalising their businesses.

Participant 7: At the moment there is always invitations to go to workshops and the information circulates our emails and we are getting advise now from government organisations that help small businesses and I am attending workshops for small businesses and its very beneficial because I am learning.

Participant 14: What I can say is that our businesses are now better structured and even the way the government communicates with us has improved because they always communicate as well as amongst ourselves as business people. We have whatsapp groups where we communicate about any opportunities that are available.

This study determined that when business owners are formalised, they start accessing other opportunities that were elusive before. It was argued that non-governmental organization, government departments and other stakeholders that assist small businesses are likely to interact with formalised businesses compared to those that remain unformalised (Tuominen and Martinsuo2019). This gives us enough power to make a strong claim that formalised businesses stand a better chance to access varied important information compared to those that are not formalised.

12. Sub-theme: 1.3 improved chances of securing credit

It has been reported massively in the literature that lack of credit for small businesses is a very big problem (Devey et al., Citation2006; Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM), & 2015; & Charman and Petersen 2014). However, our findings indicate that there is improved funding when a business is formalised, and it is a black-owned business in South Africa. In as much as the participants involved in this study acknowledge the fact that it is not an easy process to get credit, they do state that chances are a bit higher when a business is registered. According to participant 4, when an entrepreneur approaches a bank seeking for a loan, formalisation is the first thing they ask about, and it is a similar case with the other funding institution be it public or private. This clearly states that businesses that are not formalised might stand a zero percent chance of securing credit, and if they do get it, it will be very expensive.

Participant 4: I can say its easy and cheap to get credit when your business is registered because that is the first thing the bank ask when you go there looking for money. Also there is other organisations from government that help small businesses to grow too but first thing they want you registered.

Participant 6: I think i can say that clients trust me more now than before because people like to do business with someone of fixed aboard. I also managed to secure a loan from the bank because they saw that my business if legit.

Participant 8: I was able to get a small loan to boost my businesses so right now I am even supplying those who are selling the products I produce even on the street.

Participant 10: As for me, the first benefit was the capital that I received from SEFA. I would not have grown if I had not received that fund.

Participant 5: I thought it was going to be easy to get like business loans but its not easy because the requirements are just too much and sometimes you just feel like they don’t want to give you the loan.

However, participant 5 had a different experience even if the businesses was registered, but the benefits were difficult to exploit since the requirements from the financial institution approached were discouraging and too much for the entrepreneur to secure credit.

13. Sub-theme: 1.4 increased credibility of the business

According to the findings of this study, established businesses want to deal with established businesses too and better-paying clients like the government departments. On the other hand, private entities want to deal with registered and tax-compliant businesses. This is the reason why businesses that operate in the informal sector struggle with growing their markets as they struggle to supply certain segments of the markets like the ones mentioned above. One of the reasons why established and registered businesses want to deal with only formalised businesses is that they can be able claim VAT returns (World Bank, Citation2018). Looking closely from the interviewed business, increased businesses’ credibility is one of the benefits that are derived from mainstreaming business operations. Participants argue that clients take you serious if you have a company profile and you are tax compliant. On another note, since small businesses struggle with business expertise, certain banks have come to close that gap by offering business advises to clients who bank with them or those small business owners who have managed to secure a loan with that specific bank (Maduku & Kaseeram, Citation2019).

Participant 1: Uuum what I can say is that right now I am more trusted by clients because I now even give receipts and I have a better shop now. Also the bank has been giving me advises about my business as well.

Participant 2: What I can simply point is that there is trust when you are formal and you are able to get better paying clients compared to when you are doing business at your house or on the street.

Participant 6: I think I can say that clients trust me more now than before because people like to do business with someone of fixed aboard. I also managed to secure a loan from the bank because they saw that my business is legit.

Participant 9: In my case I think its all about the trust that you get from clients by being a business that has a fixed place where clients can refer each other and make it easy for your business to grow.

The credit benefits emanating from mainstreaming businesses range from being trusted by clients, being able to be recognised by suppliers, benefit from possible discounts and the ability to negotiate to be supplied inputs on consignment basis (Fajnzylber et al., Citation2011). According to the participants, the fact that there is credibility on the side of the entrepreneur because of formalities from registration and tax compliance can bring sustainable financial inflows that can sustain a business because a business will be able to create brand and customer loyalty. When you are a business with an address and a fixed address, it becomes easy for your loyal clients to refer other clients and that can help grow a business.

14. Sub-theme: 1.5 better access to markets

Participants also mentioned improved access to markets for black-owned businesses in South Africa after they have mainstreamed their operations as one of the benefits. In as much as there is a possibility of an improvement in market expansion after formalisation, access to market is a big challenge for small businesses in South Africa (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM), & 2015). After a business has formalised, there is increased probability of securing credit. When small businesses secure credit, they are able to fund their research budgets and advertising budgets and that help to grow their markets.

15. Conclusion and policy recommendations

The objective of this paper was to understand the challenges and benefits of formalisation in South Africa. To achieve this objective, the study conducted interviews with 15 entrepreneurs who operate in diverse sectors in the economy. The novelty of this study was based on the originality of the study in understanding the concept of formalisation selectively investigating black entrepreneurs. Second, research on the transition process among black entrepreneurs in South Africa is outdated and limited. The findings of this study are important for the South African literature solidly because black entrepreneurs consist of the biggest percentage of informalised businesses in South Africa as well as the least successful entrepreneurs in the country outside other races.

Using themes to analyse the data, the study found, on the challenges hampering the formalisation process, high levels of bureaucracy, unsustainable fees and processes, information asymmetry, credit or capital unavailability and corruption as key challenges being faced by black entrepreneurs. On the benefit stand, the study identified increased chances to benefit from black economic empowerment (BEE) policy, improved access to information to supply the public sector, improved chances of securing credit, increased credibility of the business and better access to markets as benefits that black entrepreneurs derive from formalisation.

The study observed that access to government subsidies and incentives is limited amongst black entrepreneurs; hence, the researcher recommends that the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) works to expand its budget so that more black entrepreneurs can access funding. Institutions like SEDA and other incubation centres should also be expanded and capacitated so that they bring needier entrepreneurs who lack skills to plan their businesses as well as apply for funding. To add on the recommendations, there is need for the Government of South Africa to introduce tax breaks for struggling small businesses in an effort to raise their competitiveness as they find the tax rates to be too high for their growth projections. The study further recommends that the government review on the number of days that businesses take to formal register as it is working as impediments for formalisation efforts. Also, the study found that there is evidence of miscommunication between policies and players mainly because players such as small business owners feel excluded from processes and their interests are not well represented in current policies. Lastly, the Government of South Africa needs to guarantee loans for small businesses from financial institutions if the percentage of loans from financial institutions is going to expand for the benefit and growth of black small businesses in South Africa. The growth and success of informal businesses in South Africa is important for increased formalisation rates as well as improved employment conditions for informal workers; hence, policy attention has to be increased towards informal small businesses in South Africa.

16. Trustworthiness of the study

In making sure that the findings of the study are dependable, the researchers did a member-checking session where the entrepreneurs who were interviewed were given the findings for them to confirm if they do represent their input.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andrews, M. (2007). Is BEE a South African growth catalyst? (Or could it be …). In Paper for the international growth panel initiative, Kennedy School 08 033. Harvard University, 107. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1266797.

- Bargain, O., & Kwenda, P. (2011). Earnings Structures, Informal Employment, and Self‐Employment: New Evidence from Brazil, Mexico, and South Africa. Review of Income and Wealth, 57, S100–S122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4991.2011.00454.x

- Boly, A. (2018). On the short-and medium-term effects of formalisation: Panel evidence from Vietnam. The Journal of Development Studies, 54(4), 641–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2017.1342817

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- De Soto, H. (1989). The other path: Invisible revolution in the third world. Harper and Row.

- Devey, R., Skinner, C., & Valodia, I. (2006). Second best? Trends and linkages in the informal economy in South Africa. Paper to be presented at the development policy research unit and trade and industrial policy strategies annual conference on “accelerated and shared growth in South Africa: Determinants, constraints and opportunities”. Johannesburg, South Africa (SSRN).

- Dworkin, S. L. (2012). Sample size policy for qualitative studies using in-depth interviews. Archives of Sexual Behavior Journal, 41(6), 1319–1320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-012-0016-6

- Fajnzylber, P., William, M., & Gabriel, M. R. (2011). Does formality improve micro-firm performance? Evidence from the Brazilian simples program. Journal of Development Economics, 94(1), 262–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2010.01.009

- International Labour Office. (1973). Employment, income and equality: A strategy for increasing productivity in Kenya. ILO.

- International Labour Organization (ILO). (2014). Global Employment Trends. Recovering from a second dip. International Labour Organisation.

- Janneke, P., Ana, I. M., & Abdul, A. E. (2011). Outsourcing and the size and composition of the informal sector: Evidence from Indian manufacturing. IZA-Institute for the Study of Labour.

- King, N., & Horrocks, C. (2010). Interviews in qualitative research. Sage.

- Kumar, R. (2011). Research methodology: A step-by-step guide for beginners. Sage.

- La Porta, R., & Shleifer, A. (2008). The unofficial economy and economic development. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. 275–352.

- Maduku, H., & Kaseeram, I. (2019). Mainstreaming willingness among black owned informal SMMEs in South Africa. Journal of Emerging Trends in Economics and Management Sciences, 10(3), 140–147. https://hdl.handle.net/net/10520/EJC-1cf9d6e138.

- Merriam, S. (2009). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. Jossey-Bass.

- Moloto, G. R. B., Brink, L., & Nel, A. J. (2014). An exploration of stereotype perceptions amongst support staff within a South African higher education institution. South African Journal of Human Development, 12(1), 573. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v12i1.573.

- Pheko, M. M. (2014). Batswana female managers’ career experiences and perspectives on corporate mobility and success. South African Journal of Human Resource Management, 12 (1), 1–11. http://dx.doi.org/10.4102/sajhrm.v12i1.445.

- Portes, A., Castells, M., & Benton, L. A. (Eds.). (1989). The informal economy: Studies in advanced and less developed countries. JHU Press.

- World Bank. (2015). Stocktaking of the housing sector in sub-Saharan Africa challenges and opportunities.

- World Bank (2018). World Bank country and lending groups – World Bank data help desk:https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-worldbank-country-and-lending-groups [Accessed 25 Oct 2018]