?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The aim of this study is not only to define the industrial development space of the region in Vietnam, but also to assess the linkage in local industrial development. Research space in the Southern Key Economic Region—Vietnam’s most vibrant industrial production region—is based on the approach in both aspects: output value and agglomeration of production enterprises through the number of businesses. By taking a diversified approach from defining the growth linkage indicator to simulating the industrial structure pattern by the network, and using the regression model with the industrial production enterprise data of the Region in the period 2011 − 2019. The research result shows that there has been a significant increase in the linkage to the development of industrial space in the Region. Besides, the pattern of industrial development space of the Region has both increased the production value in the central areas and spread the industrial bases established in other localities in the Region. From scientific findings, this paper gives policy implications as well as contributes to some improvements in assessing, analyzing and verifying industrial development space in the locality, especially for developing economies like Vietnam.

1. Introduction

Industrial development space, especially at the regional level in the development process is a major topic in the study of the theory and practice of policy makers (Porter, Citation2008). In the process of local economic development, regional industrial linkage and development take place under the influence of market performance, the role of the government to create various industrial development patterns.

Theoretically, neoclassical economics (Solow, Citation1956; Swan, Citation1956) have shown that in the long run, economies will agglomerate on per capita income basis. This implies that the developing economies will also have a faster growth period than the highly developed economies, from which economies will have long-term convergence. However, in terms of research on the spillover and linkage in spacial economic development, this topic only really becomes a big one based on the theory built by Alfred Marshall, Krugman, Porter, and other economists (Vorley, Citation2008; Smith, Citation1970).

From the process of development, spillover and agglomeration in economics, theoretical studies determine the industrial development linkage through many different approaches from the similarities in the intensity of production factors to industrial intensity, or it is the connection through the input-output product linkage by the product value chain, or prerequisite institutions (Lall, Citation2000; Leamer, Citation2000; Rodrik, Citation2005). Hidalgo et al. (Citation2007) used an output-based approach to determine the industrial development linkage at the national level based on the idea that in an area where there is a consistency of institutions, infrastructures, physical factors, technology, or a combination of these, industries with development linkages will grow in tandem, while distinct industries won’t be made together or won’t grow together. This indicator is called “Proximity” and used in many experimental studies (Balland et al., Citation2019; Boschma, Citation2017; Hu et al., Citation2019).

The Southern Key Economic Region in Vietnam, established in 1998, includes 8 provinces/ cities, such as Ho Chi Minh City, Dong Nai, Ba Ria—Vung Tau, Binh Duong, Tay Ninh, Binh Phuoc, Long An and Tien Giang. This Region has an area of more than 30,585 km2, accounting for 9.2% of the area, and a population of about 21.4 million, accounting for more than 22.2% of the country’s population (in 2019). It is the most dynamic economic region in Vietnam with more than 43% of businesses, of which Ho Chi Minh City is the largest city in Vietnam and is also the economic center of the Region. Therefore, industrial development is the strength of the Southern Key Economic Region, an important driving force in the economic growth of the Region and the country. The study of industrial space in this Region is also an important practical contribution to the transformation of industrial development patterns at the Regional level in a developing economy like Vietnam.

Overall, our research contributions are given with 3 points:

First, using diverse indicators with different approaches, the research depicts the picture of industrial development in the largest economic region in Vietnam in aspects of industrial development space, the degree of linkage of regional industries as well as changes in regional industrial development over time.

Second, this study examines the topology of industrial development in a key economic region of Vietnam. This reflects the developmental characteristics of regional industrial structures in a developing country like Vietnam.

Third, this study identifies the relationship in industrial development linkage and industrial space development. This contributes to the evidence in discussions about local industrial development as well as helps local policymakers to orientate appropriate policies in local development.

The following sections of this study are organized as follows: Section 2 describes the relevant studies and hypotheses in the study. Section 3 describes the data and estimation approaches. Section 4 depicts the industrial development space as well as the degree of linkage within industries. Section 5 assesses the impact of industrial development linkage on the development of industries. Finally, we draw conclusions and implications in the theory and practice of regional industrial development policy.

2. Literature review and Hypothesis

2.1. Regional industry development and linkage

Industrial structure is associated with the nature of the linkage in the development between economic branches and the development of the local economy. A core theory in the study of linkage and agglomeration in development, especially in industries is Marshall’s observations.

The industrial district was initiated by Marshall (Citation1890) with views of this agglomeration in a geographical area where enterprises are concentrated with their knowledge and information characteristics. Marshall argues that the decision for the location of production derives from the aspect of “specialization of business” and proximity in complementary industries as well as specialization of these industries (Belussi & Caldari, Citation2008). In addition, Belussi & Caldari (Citation2008) also interprets that the two favorable characteristics from Marshall’s studies are the industrial leading and the introduction of novelties and creativity in production. Accordingly, the spatial agglomeration of established enterprises helps to form specialized industrial-technical structures, thereby promoting the development of specialized industries (Whittle & Kogler, Citation2020; Engelsman & Raan, Citation1994).

Marshall (Citation1890) emphasizes on specialization while Jacobs (Citation1969) stresses on diversity from forming industrial development spaces that help enterprises and regions continuously create new knowledge to form or continue retaining comparative capabilities of region.The choice of production sites of businesses is subject to great influence from the resources of the sites (labor, transportation costs, markets and other resources; Vorley, Citation2008).

Another highlight of the study of linkage in economic development is the fundamental ideas in Perroux’s growth poles theory (Higgins & Savoie, Citation2017). Accordingly, in the process of economic development, some locations will develop faster thanks to different resources, which leads other regions to growth and development. It is the growth poles and the spatial spillover effect that help form linkages in economic development in general and economic sectors (Kuchiki et al., Citation2017).

In a value chain-based approach, Hirschman analyzed and pointed out important linkages in the structure of economic sectors. He used the concepts of backward and forward linkages to study the intra- and extra- industry linkages based on the input-output linkage chain in production (A. Hirschman, Citation1958; AO, Citation1964).

In another approach to the linkage in industrial research, M. Porter goes deep into the “industrial cluster” in the linkage of economic sectors. Accordingly, the development of industries that are closely related or linked to each other in terms of production, resources or mutual assistance in trade can form clusters of industries to promote the development of each industry, each business and the whole industrial cluster in general. In an industrial cluster, the relationship among enterprises in the industry is formed not only from complementarity, but also from competing relationships for development (Porter, Citation1990; Porter, Citation2008; Fujita et al.,Citation1999).

The research aspect of spillover and linkage in special economic development really becomes a big topic when forming a theory by Marshall, Krugman, Porter, and other economists. That provides reasonable theoretical foundations for explaining the phenomena of agglomerating and concentrating economic activities in different geographical regions as well as spreading in economic development (Krugman, Citation1991, Citation1999; Vorley, Citation2008).

With the approach to local theories and gravity models, Britton analyzes the industrial linkages in the Briston region (UK) with other parts of the UK. The research result shows that the form of linkage among regional industries depends heavily on the trade exchange relationship between the region and other localities, market size, traffic costs, etc. In particular, he emphasizes the geographic factor (traffic costs, market, etc.) in inter-industry linkages through the interoperability—distribution effects of industrial characteristics; at the same time, he also suggests about the industry which is characterized by “mobile”, being not clustered according to geography (Britton, Citation1969).

Richter (Citation1969) focused on two issues: (i) Measuring spatial linkage, (ii) Evaluating industrial linkage in a region. The results indicated that the industrial linkage is the driving force of agglomeration; the geographic linkage usually occurs in linkages among industries, and in contrast, when there are linkages among industries, geographically linked regions usually occur. Meanwhile, the research also shows that this industrial linkage helps to promote the process of centralization into industrial clusters in economic regions (Richter, Citation1969). In the same research topic on the economic and spatial linkages of industries in a specific region, Strcit uses the labor indicator in industries to assess, providing linkages between industries in France and West Germany (Strcit, Citation1969).

Whittle and Kogler (Citation2020) emphasizes the concept of development linkage as a unique distinctive view as well as the spatial embeddability on the dynamics of co-evolutionary networks in regional diversification and complex knowledge production. Another perspective on development linkages is the concept of “related variety” or the integration and complementation of differences in knowledge for development among different industries (Boschma & Frenken, Citation2011; Frenken et al., Citation2007). Accordingly, development linkages show the harmony in regional industrial development. This implies that regional industrial growth and development, especially innovations and creations, are based on a process of growth in sync with each other. This is expanded more in comparison with the concepts of related relationships in products and industries. Hidalgo et al. (Citation2018) indicate that in principle, development linkages occur when they require knowledge relatedness or inputs. In fact, the inputs as well as the knowledge used in the production process are not perfectly observable (Hidalgo et al., Citation2018).

Spaces on products, industries, knowledge and skills can be defined at the regional level to help clearly describe the current the state of industries. Neffke et al. (Citation2011a; Citation2011) argue that this is a powerful tool for regional economic analysis and regional policy-making processes. This approach identifies regional industrial spaces as well as shapes favorable industries and threats to regional development. These are also the approaches used by many researchers and policy makers for academic research as well as in practice (Boschma, Citation2005, Citation2017; Hassink, R. et al.,Citation2014; Hidalgo, 2021).

The empirical studies on local industrial development show that the development of regions works through the development process at a smaller level as well as the influence of product structure is higher than the national level (Neffke et al., Citation2011; Boschma & Capone, Citation2015; Essletzbichler, Citation2015). Pinheiro et al. (Citation2018) show that the percentage of industries which are not in the same industry group developing together in a region is very low. In other words, industries that belong to the same industry group are not frequently present in spatial regions or appear over time. In contrast, observations in specific regions in developing countries indicate that the probability of industries that do not belong to the same industry group has a higher presence level (Hu et al., Citation2019; Boschma, Minondo, & Navarro,Citation2013). Moreover, indutries have more extra-industry linkages due to the value chain characteristics, in which added values in domestic production are often poor in developing economies (Narula & Dunning, Citation2000; Rodrik, Citation2006).Citation2013

Therefore, the region’s industrial development linkage space can be described as a group of enterprises in an industry and industries in an economic region like a linkage network of industries and groups of industries in which the density of industry linkages forms linkages that promote the maintenance/ development or production of new industries.

2.2. Measurement of regional industrial development characteristics and linkage of industries

An approach to measuring development linkage level is through the similarity in resources among industries. This approach emphasizes the harmonization of bottom-up forms of development stemming from the origin of resources of industries. Engelsman and Van Raan (1991) use patents to identify co-development relationships. Breschi et al. (Citation2003) use patents to analyze and identify homogeneity in the development of technological industries or enterprises. Fan and Lang (Citation2000) calculate the homogeneity in the US commodity data in the input-Output (IO) table to determine the homogeneity relationship across industries as well as vertical and horizontal industry groups. One of the difficulties with this measurement, though, is that the differentiation in specific resources among industries is different. Especially at the geographical region level, building the IO table encounters many challenges, and in developing economies, the use of index like patent is not feasible.

The co-development measurement approach is based on considering the presence or the presence maintenance in the same area. In a regional development space, manufacturing industries will develop successfully if they have similar technical outputs or products in the production chain as well as available regional advantages (Hidalgo et al., Citation2007). This continually motivates manufacturing firms to exploit local advantages and related industries to thrive (Feldman & Audretsch, Citation1999; Glaeser et al. Citation1992). In addition, new products can emerge by making use of of existing cost advantages under the influence of spillovers in terms of technology, knowledge, skills and local advantages (Duranton & Puga, Citation2001; Gkypali et al., Citation2017, Citation2019). Hidalgo et al. (Citation2007) use the output to develop network metrics to shape the nation’s product space, which also helps to better describe products/industries with the development linkages in the industry space. Similarly, Neffke et al. (Citation2011) use this approach to define the industrial space of the industry based on product development linkages in factories.

Hu et al. (Citation2019) on analyzing the regional industrial development space, is based on Hidalgo et al.’s paper with adjusted calculation in the region level. Accordingly, groups of industrial products developing together to gain comparative advantages in the region imply that there is a linkage between these two industries when they develop together in the same context. Studies rely on labor correlation indices among industries to measure the linkage in a defined economic space as well as supplement indicators or other factors that influence the linkage among industries, such as organizational factors, technological complexity according to economic sector characteristics as well as the ownership form of industrial enterprises (Harrigan, Citation1982; Taylor & Wood, Citation1973), and social relations in production (Scott, Citation1983). Besides that, determining the industrial structure is commonly used through the output products in industrial development, such as Hidalgo et al. (Citation2007); Hu et al. (Citation2019). Determining the structure of industrial product sectors is through the Revealed Comparative Advantage (RCA) index of industries. Balassa’s proposed RCA index (Balassa, Citation1965) aims to identify the advantageous industry in the overall development of different products. On the national level, Hidalgo et al. (Citation2007) examines the value of output products in trade with other countries to identify the industries whose advantage. Hidalgo et al. (Citation2007) argued that industries with their comparative advantages (RCA≥ 1) show the industry linkages in the development space.

In this study, we use the indicator proposed by Hidalgo et al. (Citation2007) and Hu et al. (Citation2019) to make some adjustments to the calculation scale in 2 aspects:

The first is the aspect of output value instead of export value. The confirmation of industrial output value according to industry and locality is very meanigful in determining the existing industrial development space in the locality. Some other studies also use this indicator to calculate the relationship among industries, such as Boschma and Iammarino (Citation2009), Neffke and Henning (Citation2013), and Hu et al. (Citation2019).

The second is the aspect of the number of enterprises. The agglomeration of industrial enterprises and linked industries will be shown through selected locations where production is increasingly close to each other among enterprises. Therefore, the use of an indicator of the number of enterprises will also help adjust the extreme variation in output and labor variables due to the industrial characteristics (Neffke & Henning, Citation2013; Ter Wal & Boschma, Citation2011).

Therefore, this study expects the regional industrial space through the development of industries to have significant differences over time, especially the development linkage among regional industries.

Hypothesis 1: The development process of regional industries is attached to the industrial development linkage.

Hypothesis 2. The industrial development space is actively promoted by the degree of development linkage among industries.

Under the spillover effect in development, the industrial space has been expanded in the form of an inverted U-shape. Accordingly, the more highly developed regions are, the slower the growth rate is; in less developed regions, the growth rate is higher (Castellacci, Citation2011; Gkypali et al., Citation2019; Hu et al., Citation2019).

Therfore, the industrial development space of regions has been expanded more and more with increasingly advantageous industries and gradually caught up with developed regions; however, this also creates controversy in different studies. When developed regions can take their advantages in industrial development, they increasingly develop into large clusters and maintain their advantages in industrial space development as well as regional economic development (Bathelt & Cohendet, Citation2014; Cortinovis et al., Citation2017; Hassink et al., Citation2014).

This study expects that the industrial spatial structure among different localities will be significantly different based on existing local capacities. This implies that there will be space for industrial development.

Hypothesis 3. The space of district- industries are expected to expand based on the potential impacts of localities’ capacities in the region.

3. Data and methods

3.1. Data

The study uses data from the enterprise survey in 2011 and 2019, in which the 2019 data set is the latest current one on the enterprise survey. To measure the structure and linkages among industries, the authors use the aggregate industry-level information with 137 industries (4-digits level) represented at the regional level in 2019, which corresponds to 18,769 (137 * 137) pairwise linkages among industries (only in 2011, there were only 134 industries)

3.2. Measurement of industrial linkage

The industrial linkage is based on the technological similarity index proposed by Hidalgo et al. (Citation2007), in particular:

Where

, or

,

And

In which, φ is the index measuring the level of development linkage (similarity in development) between the two industries; RCAdi (calculated according to the output value-Value, and the number of enterprises-Quan) is the revealed comparative advantage of the local industry; and Density is a variable that shows the level of development linkage among industries over time and by locality.

3.3. Network analysis

To analyze the relationship in the development linkage among regional industries, we use the network analysis method to focus on relationships and linkage patterns (Scott et al., Citation2008). Many studies on the relationship between factors, especially in industrial development, have used this method to determine the relational characteristics as well as the structures within the widely used network to analyze industrial clusters (Montresor & Marzetti, Citation2008; Yigitcanlar et al., Citation2020).

In this study, we use the network analysis method to visualize and analyze the characteristics of the relationship among industries.

3.4. Estimation model

To test the research hypotheses, we propose research models based on the indicator measuring local industrial development in relation to other local manufacturing industries. Accordingly, the dependent variable used is the RCA variable of the district-industry in the Region in 2019, representing the level of local industrial development. In addition to using the output indicator, we additionally use the quantity of enterprises of district-industries to compare aspects of local industrial development, particularly in a developing economy like Vietnam; the business indicators play an important role in analyzing industrial development.

The independent variables include:

The local Industrial development Index 2011: This is measured through RCA indicator of the local industry in 2011.

The industrial development linkage index: This is measured through two variables—the average value of growth linkage (φ) in 2011 (FP2011), and the total number of industrial linkages with other industries in 2011. (MP2011).

The measurement index for agglomeration degree of regional industry: This is measured in 2011 with 2 density variables (Denri2011) and squared density (Denri11_2).

The variable measuring the level of keeping or promoting new local industries is to determine the effect of local capacity on industrial development in two points: Keep advantageous industries or develop new industries (Hu et al., Citation2019; Boschma, Minondo, & Navarro, Citation2013).

The research model was set up in 2019 with the independent variables used in 2011. With a 9-year lag, and large number of observations, the potential endogenous problem and the reverse causality are under control. In addition, we use the robust model in econometrics, as well as the estimation with a high-dimensional fixed effects approach at regional and industry levels. The effects of taxation, policy or distinct initial approach conditions for each industry or locality are partly eliminated by the variable in 2011, partly eliminated from the fixed effects, and the model is then estimated firmly through error correction.

4. The linkage and development of industrial space in the Southern Key Economic Region

4.1. An overview of the level of industry development in the Region

The Regional industrial space was expanded significantly in the period 2011–2019 whether in terms of production value or the number of businesses operating in all industries and fields.

The industrial development space in the Region shows a considerable expansion on taking into account the production activity of level 4 -digits industries in the district area. From 3566, the number of district-industries in 2011, up to 2019, the district-level industrial space increased to more than 3.3 times to 11,788 district-industries.

Accordingly, the number of advantageous industries at the district level has increased from 1334 to 5746 (an increase of more than 4.3 times) in terms of production value, and the rate of expanding local industrial spaces is similar in terms of the number of businesses established by industry at the district level (an increase of 4.2 times).

The Region has a concentration of electrical, electronic and component industries, textiles, footwear, plastics, and food and food processing. The total value of the 10 largest industries in 2019 accounts for more than 53% of the total industrial value of the Region, in which, the production of communication equipment (code: 2630) accounts for 19.4% of the industrial production value of the whole industry. Furniture production, textiles, footwear, mechanics, food and foodstuff are the ones with a large number of enterprises in the Region, in which 2 industries, furniture (code: 3100) and costume production (code: 1410), account for 18% of the total 39,168 industrial enterprises in the Region.

In the nine years from 2011 to 2019, there were 3 new product groups (level 4 code) in food production and equipment reparation (1077, 1079, and 3319). The groups of industries with a rapid increase in the number of enterprises as well as the production value are enterprises operating in the fields of mechanical engineering, textiles and businesses operating in the field of food.

It can be said that the Southern Key Economic Region is currently the Region with a large degree of production diversity, agglomerating many conditions and advantages to develop high-tech industries, such as electronics, informatics, food industry, etc., associated with the Region’s strengths in the capacity of providing high-quality services, meeting high-quality human resources, researching and deploying scientific and technological activities.

4.2. The analysis of the linkage level of industries in the Region

4.2.1. The policy to promote linkage for regional development

The strategy for the development of the Southern Key Economic Region, the strategies for socio-economic development of the eight provinces and cities in the Region, especially the industrial development strategy in the Southern Key Economic Region recently issued (January, Ministry of Industry and Trade (MOIT), Citation2017), all have scientific bases, based on the advantages of each locality and the connection among localities in the Region and the country. This is the basis of orientation for industrial development in the Region, especially in the planning of development of industrial parks and industrial clusters in localities.

In the market economy, enterprises will make decisions on investment and business activities on the basis of market analysis and exploitation of comparative advantages. Therefore, the functional factor of the market plays an important role in “leading” the linkage activities to develop industries in the Southern Key Economic Region. The Region has initially established the linkage among industrial enterprises in the direction of specialization, associated with local advantages. For example, by 2019, the agro-forestry and fishery product processing industry was distributed in most localities in the Region, but mostly concentrated in Ho Chi Minh City, Dong Nai and Binh Duong; metal processing and machinery manufacturing industries are mainly concentrated in Ho Chi Minh City, Dong Nai and Ba Ria—Vung Tau, which are industrialized localities and have human resources meeting the requirements; chemical and pharmaceutical industries are centered in Ho Chi Minh City, Dong Nai, and Binh Duong; textile industry is also concentrated in 3 southeast areas: Ho Chi Minh City, Dong Nai and Binh Duong; however, garment industry has spread to other localities, such as Long An, Tay Ninh, Binh Phuoc, etc.

The strategy for the development of the Southern Key Economic Region to 2025 and the vision 2035 have set the goal “by 2025, the Southern Key Economic Region becomes a modern industrial Region, developing the Region’s industry in association with its technological sciences and industrial products with high quality, competitiveness and added value” with the view of strengthening the regional linkage (Ministry of Industry and Trade (MOIT), Citation2017).

4.2.2. The linkage and structure of Regional Industries

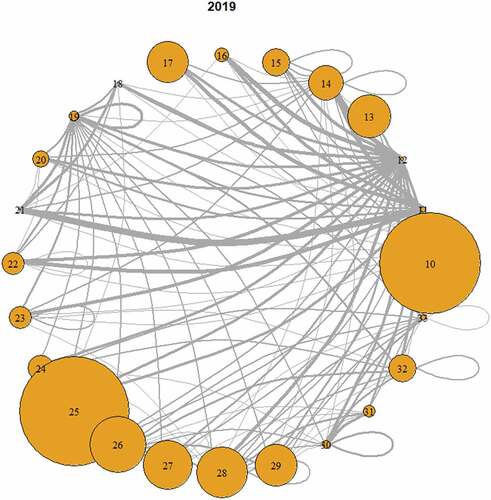

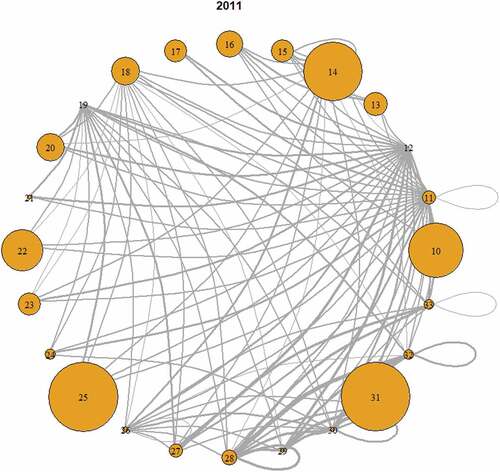

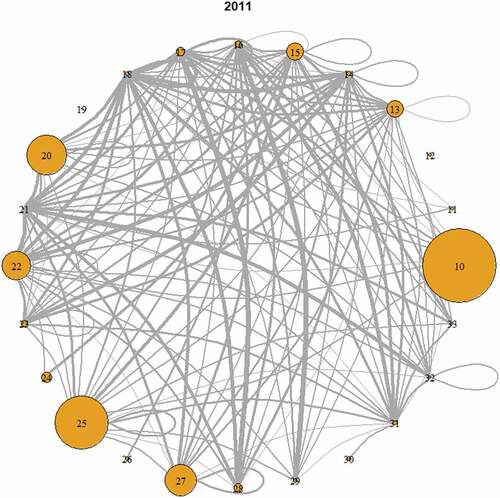

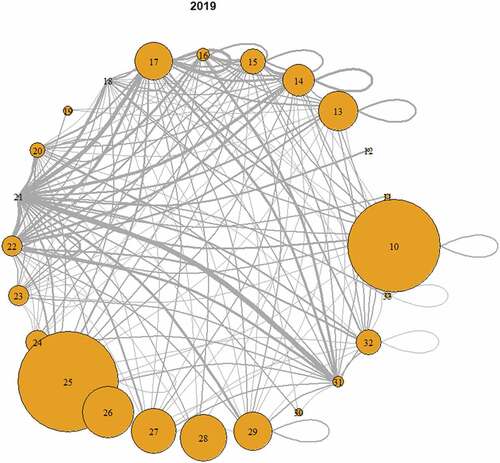

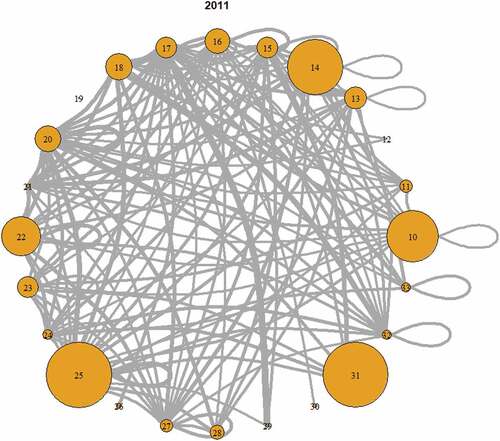

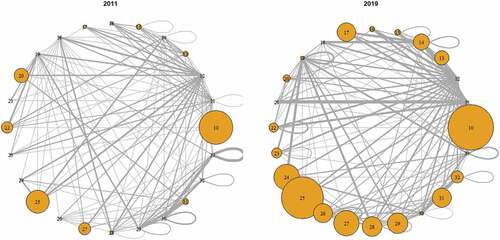

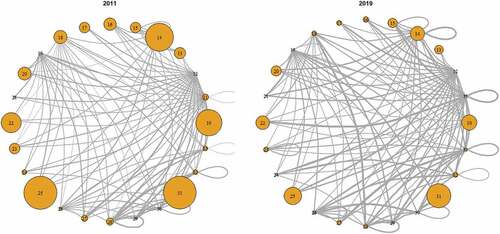

The industrial space is depicted by the degree of development linkage among industries. In 2011, there were 12,360 pairwise links among industries, and by 2019 this rose to 12,576 pairwise links (). This indicator points out the consistency with the above statistics on the industrial space of the Region that has expanded significantly as well as increased linkages among industries in localities in the Region.

Table 1. List of variables, models, and hypothesis expectation

Table 2. The district-industries development space

The index of linkages among industries has increased considerably in all indicators, at an average from 1.25 in 2011 to 1.54 in 2019. Half of the links in 2019 reached a value of 1 or higher than 0.77 in 2011.

In terms of the number of manufacturing linkages by district-industries, from 2011 to 2019 there was no major change in central values. However, the indicator of standard deviation (SD) in 2019 decreased in comparison with 2011, showing that there was a scatter in production activities among industries and localities in the Region. In other words, during this period, the Region had the spillover in production activities ().

Table 3. Industrial development space by level 4 industry code

Table 4. Industrial development by Level 4 industry code

The statistics on the highest linkages in value (FP) and the number of linkages (MP) by group of industry (industry group level- 2 digits level), both show prominently in the link structure among typical industries of the region: food, foodstuff, textiles, electronics, and mechanics (, ). Furthermore, the structure of the intra- and extra-industry relationship by level 2 industry codes shows that intra-industry linkages are generally much higher than extra-industry ones ().

Table 5. Industrial development linkage index

Table 6. The number of industrial development linkages

Figure 1. Simulating the development linkages for level 2 industries by the output value (calculated at 4-digit data level).

Figure 2. Simulating the development linkages for level 2 industries by the number of enterprises (calculated at 4-digit data level).

Being different from the observations of the concentration in the linkage development among industries in the studies of Hu et al. (Citation2019) or Boschma, Minondo, & Navarro (2012), the development of the industrial space in the Key Economic Zone of Southern Vietnam shows that industries tend to stronger link and develop in the same industry group (). This study complements the results of Pinheiro et al. (Citation2018) on industry development trends not only at the national level but at the regional level. Accordingly, closely related industries in industry groups have a higher degree of development linkage, and are significantly higher than in other industry groups. Moreover, the development linkage degree of new industries have increased significantly; the extra-industry development linkage has always remained at a relatively high level (only slightly lower than the level of intra-industry). This implies that regional industrial development in developing countries like Vietnam can include two trends: both enhancing core industries and forming and promoting new industries.

Table 7. Index for industry development linkages by level 2 industry code

4.3. The role of industry development linkage to regional industrial space expansion

Through the quantitative model of the Region’s industrial space with robust estimations in the period 2011–2019, we focus on two analytical aspects: (i) First, the role of local fundamental factors in promoting local industrial space. (ii) Second, the impact of industrial development linkages on industrial space increased in the effect direction of concentration or spillover.

The estimation model based on the output value of industries () shows:

Table 8. Estimation model (value)

Local fundamental capacity plays an important and very positive role in the expansion of industrial space in terms of both industry and locality. Through the robust regression model, in different models, it is shown that the consistent impact is positive and of high impact.

In terms of development linkages, neither the quantity nor the value of industry linkage in the Region plays a role in expansion of Regional industrial space. The result from the regression model proves that although the impact on the industrial space expansion in the Region has a positive trend, it is not statistically significant.

Meanwhile, the variable of the agglomeration density of industrial production value has a positive impact on the expansion of industrial space in the Region. This implies that the expansion of local industrial space will be promoted more actively as the production density agglomerates. One of the important questions is: Does the Region’s industrial spatial morphology reach the inverse U state or not? The result from the model (variable Denri11_2) shows that although the industrial space development of the Region looks like the inverse U state (the sign of the regression coefficient is negative), it doesn’t reach statistical significance.

Finally, the role of localities in the effect of maintaining and developing the advantage of industries is based on local competencies. Both the variables Keep and New are statistically significant at approximately 10%, implying that localities in the Region develop industrial space continuously and closely with the local capacity. Besides that, the impact of local capacity also plays an important and large role in promoting the local industrial space.

The estimation model based on the number of enterprises of industries () shows:

Table 9. The estimation model (The number of enterprises)

The fundamental capacity of the locality plays an important and very positive role in the expansion of industrial space in terms of both industry and locality. Through the robust regression model, in different models, it is shown that the consistent impact is positive and of high value. This is consistent with the view based on the production value of local industry.

In terms of the development linkage, neither the quantity nor the value of the industry linkage in the Region shows their role in the expansion of regional industrial space which tends to scatter the local industrial space. In other words, the negative regression coefficient (both variables of value and average number of links) and the statistical significance (average number of links, significant at 10%) show that the more local production bases industrial spaces agglomerate, the more their scatter is to other locations in the region. This implies that regional industrial space is expanding and spreading.

Meanwhile, the variable of agglomeration density by number of industrial production establishments has a negative sign with a statistical significance at 10% and the square variable (Denri11_2) has a positive sign with a statistical significance at 10%. This shows the density of the number of businesses is driving the pattern of industrial space in the region to go with U-shape. Accordingly, the expansion of the local industrial space will be promoted in the direction of spreading the whole Region; the establishments set up gradually spread to other production locations in the Region.

Finally, the role of localities is very important in the impact of maintaining and developing the industrial space. Both the variables Keep and New have negative effects and statistical significance, implying that localities in the region for industrial space development do not agglomerate enterprises but increasingly spread locally. This also shows that the local advantage in attracting businesses in old industries is gradually decreasing when there is a large number of businesses.

Therefore, 2 estimation models (in ) on both analytical aspects show that:

Firstly, the Region’s model of industrial space development is spillover, and industrial production enterprises increasingly spread locally (U-shaped pattern), however, their values still concentrate in industrial centers for capacity exploitation, and previous advantages (inverse U pattern—in output value). This implies that the regional industrial space with industrial centers continues to increase in production value while having a spillover effect on other localities apparently. This impact is not only relevant in theory and previous studies, but it is also confirmed through the establishment of new industrial parks in different localities in the Region (the result of industrial space statistics—), attracting investments, especially FDI (Adams, Citation2002; Anwar & Nguyen, Citation2011; Le & Pomfret, Citation2011).

Secondly, the role of development linkages in increasing the value of industrial production is not significant. This is a limitation in the current development linkages of industrial production in the Region. This implies that not only does the local industrial space still develop in width and spread geographically, but also shows that the quality of industrial linkages, in general, is limited. These results are consistent with previous studies from the perspective of industrial linkage based on the value chain not just in the Region, but this is also a problem in industrial production in Vietnam. Many studies have proven that both in the Region and Vietnam, there are the characteristics: the outsourcing is major; the value of participation in the production chain is low; the added value is not high (Kubny & Voss, Citation2014; Ni et al., Citation2017).

Finally, the role of local industrial development centers remains the nucleus in the industrial space of the Region. It continues to help increase production value increasingly high, showing the spread of industries in the region to other localities.

5. Conclusion and policy implications

Theoretical basis, development practice and experimental model all demonstrate the linkage in industrial development in the Southern Key Economic Region. In addition, the regional linkage factor has a strong impact on industrial development in the Region. Based on the structure and econometric model, this paper shows:

Firstly, based on the testing in one of the most dynamic industrial production areas in a transitional economy like Vietnam, the industrial production has a strong spread among industrial production localities as well as manufacturing industries.

Secondly, in the context of the transforming industrial structure in a developing economy like Vietnam, manufacturing industries have stronger extra-industry development linkages than intra-industry linkages. This is also proved through studies in the aspects of the value chain of industries, in which the linkages as well as added values in domestic production are often poor (Narula & Dunning, Citation2000; Rodrik, Citation2006).

Thirdly, the analyses of regional and local industrial space development, which need to combine the production value and the number of operating enterprises, will have many different perspectives. Specifically, developing economies with low background, when there are fluctuations in production value, can distort production activities from the aspect of enterprises’ dynamic operations as well as adjust the characteristic of the value of different industries.

In the practical development of industrial space in the Southern Key Economic Region, based on the structural transformation and the expansion of regional industrial development space, we suggest the policy implications as follows:

Firstly, it is necessary to review and supplement the content of Regional linkage for industrial development in the Southern Key Economic Region. In 2017, the Ministry of Industry and Trade approved the “Planning for Industrial Development of the Southern Key Economic Region to 2025 with a vision to 2035”, in which there is section 4.2 “Distribution of industrial development space”, identifying the industrial structure in each province/ city in the area. However, it is necessary to clarify the “linkage” of local industries, and at the same time, the content of planning and Regional industrial linkage must also be reflected in the development strategy of the Region and each locality.

Secondly, in order to strengthen regional linkages in industrial development in the Southern Key Economic Region, localities need to facilitate their legal environment, traffic connection system in the Region, provide data and necessary information for enterprises, create conditions for industrial enterprises to be active in “linkage”, and cooperate in production and business activities.

Thirdly, in order to promote Regional linkage in industrial development in the Southern Key Economic Region, besides the role of the Government and local governments, the role of the Association and each enterprise is very important. The problem is that industrial enterprises must find common interests as well as a common voice to implement and strengthen linkages. Accordingly, the “functional” factor of the market will lead the linkage process of businesses, however, this must be perceived and become the needs of businesses.

Fourthly, in order to promote Regional linkages, each locality should actively diversify forms of cooperative linkages, attract investment for businesses, such as information on regional and industrial planning, organize seminars and fairs to introduce industrial products, and carry out bilateral and multilateral cooperative research among localities on industrial development in the locality.

Fifthly, the industrial linkage can only be effective when exploiting comparative advantages goes into the division of labor in the Region, linked with domestic and international markets. Therefore, increasing competitiveness and efficiency of production and business is an essential factor for the expansion of local industrial development space. Also, it is necessary to increase the spillover of the industrial centers of the Region. The linkage and spillover of the centers in industrial development will really be the driving force for linking and promoting the development of industries in the Region.

Sixthly, the industry linkage in the Southern Key Economic Region can only develop strongly and sustainably on the basis of expanding links with localities and regions throughout the country, and connecting with enterprises and investors as well as different countries around the world. Policies to encourage investment and create a favorable environment for production and business activities of enterprises are an urgent requirement of the Government and local governments in the Region to raise the level of intra-industry linkage, and are particularly important in developing large industrial clusters in the Region and increasing local production efficiency.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nguyen Chi Hai

Nguyen Chi Hai Assoc. Prof. Nguyen Chi Hai is the Head of Faculty of Economics at the University of Economics and Law, Vietnam. His main research interest is in the field of economics. Assoc. Prof. Hai has published several papers in quality domestic and international journals.

Huynh Ngoc Chuong

Huynh Ngoc Chuong is a Ph.D. student, and a lecturer at the University of Economics and Law, Vietnam. His main research interest is in the field of Applied Economics, Economics of Development.

Tra Trung

Tra Trung is a lecturer/researcher at the University of Economics and Law, Vietnam.

References

- Adams, J. D. (2002). Comparative localization of academic and industrial spillovers. Journal of Economic Geography, 2(3), 253–27. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/2.3.253

- Anwar, S., & Nguyen, L. P. (2011). Foreign direct investment and export spillovers: Evidence from Vietnam. International Business Review, 20(2), 177–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2010.11.002

- Balassa, B. (1965). Trade liberalisation and ”Revealed” comparative advantage. The Manchester School, 33(2), 99–123. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9957.1965.tb00050.x

- Balland, P. A., Boschma, R., Crespo, J., & Rigby, D. L. (2019). Smart specialization policy in the European Union: Relatedness, knowledge complexity and regional diversification. Regional Studies, 53(9), 1252–1268. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2018.1437900

- Bathelt, H., & Cohendet, P. (2014). The creation of knowledge: Local building, global accessing and economic development—toward an agenda. Journal of Economic Geography, 14(5), 869–882. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbu027

- Belussi, F., & Caldari, K. (2008). At the origin of the industrial district: Alfred Marshall and the Cambridge school. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 33(2), 335–355. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/ben041

- Boschma, R. (2005). Proximity and innovation: A critical assessment. Regional Studies, 39(1), 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/0034340052000320887

- Boschma, R. (2017). Relatedness as driver of regional diversification: A research agenda. Regional Studies, 51(3), 351–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1254767

- Boschma, R., & Capone, G. (2015). Institutions and diversification: Related versus unrelated diversification in a varieties of capitalism framework. Research Policy, 44(10), 1902–1914. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2015.06.013

- Boschma, R., & Frenken, K. (2011). The emerging empirics of evolutionary economic geography. Journal of Economic Geography, 11(2), 295–307. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbq053

- Boschma, R., & Iammarino, S. (2009). Related variety, trade linkages, and regional growth in Italy. Economic Geography, 85(3), 289–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01034.x

- Boschma R, Minondo A and Navarro M. (2013). The Emergence of New Industries at the Regional Level in Spain: A Proximity Approach Based on Product Relatedness. Economic Geography, 89(1), 29–51. 10.1111/j.1944-8287.2012.01170.x

- Breschi, S., Lissoni, F., & Malerba, F. (2003). Knowledge-relatedness in firm technological diversification. Research Policy, 32(1), 69–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(02)00004-5

- Britton, J. N. (1969). A geographical approach to the examination of industrial linkages. The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe Canadien, 13(3), 185–198. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0064.1969.tb00956.x

- Castellacci, F. (2011). Closing the technology gap? Review of Development Economics, 15(1), 180–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9361.2010.00601.x

- Cortinovis, N., Xiao, J., Boschma, R., & van Oort, F. G. (2017). Quality of government and social capital as drivers of regional diversification in Europe. Journal of Economic Geography, 17(6), 1179–1208. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbx001

- Duranton, G., & Puga, D. (2001). Nursery cities: Urban diversity, process innovation, and the life cycle of products. The American Economic Review, 91(5), 1454–1477. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.91.5.1454

- Engelsman, E. C., & van Raan, A. F. (1994). A patent-based cartography of technology. Research Policy, 23(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/0048-7333(94)90024-8

- Essletzbichler, J. (2015). Relatedness, industrial branching and technological cohesion in US metropolitan areas. Regional Studies, 49(5), 752–766. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2013.806793

- Fan, J. P., & Lang, L. H. (2000). The measurement of relatedness: An application to corporate diversification. The Journal of Business, 73(4), 629–660. https://doi.org/10.1086/209657

- Feldman, M. P., & Audretsch, D. B. (1999). Innovation in cities: Science-based diversity, specialization and localized competition. European Economic Review, 43(2), 409–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0014-2921(98)00047-6

- Frenken, K., Van Oort, F., & Verburg, T. (2007). Related variety, unrelated variety and regional economic growth. Regional Studies, 41(5), 685–697. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400601120296

- Fujita, M., Krugman, P. R., & Venables, A. (1999). The spatial economy: Cities, regions, and international trade. MIT press.

- Gkypali, A., Filiou, D., & Tsekouras, K. (2017). R&D collaborations: Is diversity enhancing innovation performance? Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 118, 143–152 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.02.015

- Gkypali, A., Kounetas, K., & Tsekouras, K. (2019). European countries’ competitiveness and productive performance evolution: Unraveling the complexity in a heterogeneity context. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 29(2), 665–695. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-018-0589-x

- Glaeser, E. L., Kallal, H. D., Scheinkman, J. A., & Shleifer, A. (1992). Growth in cities. Journal of Political Economy, 100(6), 1126–1152. https://doi.org/10.1086/261856

- Harrigan, F. J. (1982). The relationship between industrial and geographical linkages: A case study of the United Kingdom. Journal of Regional Science, 22(1), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9787.1982.tb00731.x

- Hassink, R., Klaerding, C., & Marques, P. (2014). Advancing evolutionary economic geography by engaged pluralism. Regional Studies, 48(7), 1295–1307. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2014.889815

- Hidalgo, C. A., Balland, P. A., Boschma, R., Delgado, M., Feldman, M., Frenken, K., & Zhu, S. (2018). The principle of relatedness. In International conference on complex systems (pp. 451–457). Springer, Cham.

- Hidalgo, C. A., Klinger, B., Barabasi, A.-L., & Hausmann, R. (2007). The product space conditions the development of nations. Science, 317(5837), 482–487. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1144581

- Higgins, B., & Savoie, D. J. (Eds.). (2017). Regional economic development: Essays in honour of François Perroux. Routledge.

- Hirschman, A. O. (1958). The Strategy of Economic Development.Yale University Press.

- Hirschman, A. O. (1964). The paternity of an index. The American Economic Review, 54(5), 761–762.

- Hu, C., Zhou, Y., & He, C. (2019). Regional industrial development in a dual-core industry space in China: The role of the missing service. Habitat International, 94, 102072. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2019.102072

- Jacobs, J. (1969). The Economy of cities. Random House.

- Krugman, P. (1991). Increasing returns and economic geography. Journal of Political Economy, 99(3), 483–499. https://doi.org/10.1086/261763

- Krugman, P. (1999). The role of geography in development. International Regional Science Review, 22(2), 142–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/016001799761012307

- Kubny, J., & Voss, H. (2014). Benefitting from Chinese FDI? An assessment of vertical linkages with Vietnamese manufacturing firms. International Business Review, 23(4), 731–740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2013.11.002

- Kuchiki, A., Mizobe, T., & Gokan, T. (2017). A multi-industrial linkages approach to cluster building in East Asia: Targeting the agriculture, food, and tourism industry. . Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-57128-1

- Lall, S. (2000). The technological structure and performance of developing country manufactured exports, 1985-98. Oxford Development Studies, 28(3), 337–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/713688318

- Le, H. Q., & Pomfret, R. (2011). Technology spillovers from foreign direct investment in Vietnam: Horizontal or vertical spillovers? Journal of the Asia Pacific Economy, 16(2), 183–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/13547860.2011.564746

- Leamer, E. E. (2000). What’s the use of factor contents? Journal of International Economics, 50(1), 17–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1996(99)00004-5

- Marshall, A. (1890). Principles of economics. Macmillan.

- Ministry of Industry and Trade (MOIT) (2017), Decision “Approving the planning for industrial development in The Southern Key economic region to 2025, with a vision to 203”, August 28, 2017. https://www.moit.gov.vn/documents/25911/0/Ph%C3%AA+duy%E1%BB%87t+V%C3%B9ng+KTT%C4%90+ph%C3%ADa+Nam.pdf/a162c8a0-51b7-4e97-aa9b-9e13c217e08e

- Montresor, S., & Marzetti, G. V. (2008). Innovation clusters in technological systems: A network analysis of 15 OECD countries for the Mid-1990s. Industry and Innovation, 15(3), 321–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/13662710802041679

- Narula, R., & Dunning, J. H. (2000). Industrial development, globalization and multinational enterprises: New realities for developing countries. Oxford Development Studies, 28(2), 141–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/713688313

- Neffke, F., & Henning, M. (2013). Skill relatedness and firm diversification. Strategic Management Journal, 34(3), 297–316. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2014

- Neffke, F., Henning, M., & Boschma, R. (2011a). How do regions diversify over time? Industry relatedness and the development of new growth paths in regions. Economic Geography, 87(3), 237–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2011.01121.x

- Neffke, F., Henning, M., Boschma, R., Lundquist, K. J., & Olander, L. O. (2011). The dynamics of agglomeration externalities along the life cycle of industries. Regional Studies, 45(1), 49–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343401003596307

- Ni, B., Spatareanu, M., Manole, V., Otsuki, T., & Yamada, H. (2017). The origin of FDI and domestic firms’ productivity—Evidence from Vietnam. Journal of Asian Economics, 52, 56–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asieco.2017.08.004

- Pinheiro, F. L., Alshamsi, A., Hartmann, D., Boschma, R., & Hidalgo, C. (2018). Shooting low or high: Do countries benefit from entering unrelated activities? Papers in Evolutionary Economic Geography, 18(7).

- Porter, M. E. (1990). The competitive advonioge of notions. Harvard Business Review, 73–91 https://hbr.org/1990/03/the-competitive-advantage-of-nations#:~:text=classical%20economics%20insists.-,A%20nation's%20competitiveness%20depends%20on%20the%20capacity%20of%20its%20industry,suppliers%2C%20and%20demanding%20local%20customers.

- Porter, M. E. (2008). Competitive advantage: Creating and sustaining superior performance. Simon and Schuster.

- Richter, C. E. (1969). The impact of industrial linkages on geographic association. Journal of Regional Science, 9(1), 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9787.1969.tb01439.x

- Rodrik, D. (2005). Growth strategies. Handbook of Economic Growth, 1, 967–1014 doi:10.1016/S1574-0684(05)01014-2.

- Rodrik, D. (2006). Industrial development: Stylized facts and policies. Harvard University, Mimeo.

- Scott, A. J. (1983). Industrial organization and the logic of intra-metropolitan location: I. Theoretical considerations. Economic Geography, 59(3), 233–250. https://doi.org/10.2307/143414

- Scott, N., Cooper, C., & Baggio, R. (2008). Destination networks: Four Australian cases. Annals of Tourism Research, 35(1), 169–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2007.07.004

- Smith, D. M. (1970). On throwing out Weber with the Bathwater: A Note on industrial location and linkage. Area, 2(1), 15–18 http://www.jstor.org/stable/20000397.

- Solow, R. M. (1956). A contribution to the theory of economic growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 70(1), 65–94. https://doi.org/10.2307/1884513

- Strcit, M. E. (1969). Spatial associations and economic linkages between industries. Journal of Regional Science, 9(2), 177–188. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9787.1969.tb01332.x

- Swan, T. W. (1956). Economic growth and capital accumulation. Economic Record, 32(2), 334–361. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4932.1956.tb00434.x

- Taylor, M. J., & Wood, P. A. (1973). Industrial linkage and local agglomeration in the West Midlands metal industries. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, (59), 129–154. https://doi.org/10.2307/621715

- Ter Wal, A. L., & Boschma, R. (2011). Co-evolution of firms, industries and networks in space. Regional Studies, 45(7), 919–933. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400802662658

- Vorley, T. (2008). The geographic cluster: A historical review. Geography Compass, 2(3), 790–813. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2008.00108.x

- Whittle, A., & Kogler, D. F. (2020). Related to what? Reviewing the literature on technological relatedness: Where we are now and where can we go? Papers in Regional Science, 99(1), 97–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/pirs.12481

- Yigitcanlar, T., Adu-McVie, R., & Erol, I. (2020). How can contemporary innovation districts be classified? A systematic review of the literature. Land Use Policy, 95, 104595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104595

Appendix 1.

Data appendix

1. Manufacturing code

2. Correlation among the variables in the model

3. The development linkage by the linking value

3.1 By the output value

3.2 By the number of enterprises

4. The development linkage by the number of links

4.1 By the output value

4.2 By the number of production enterprises