?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This paper empirically investigates the effect of inflation uncertainty on domestic investment in Ghana. In addition, it investigates the differential impacts of permanent and transitory inflation uncertainty on investment in Ghana. Inflation uncertainty was measured using the conditional variance generated from the generalized autoregressive conditional heteroscedasticity (CGARCH (1, 1)) model. Employing the autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) estimator on data covering 1970 to 2020, the results provide strong evidence that inflation uncertainty, associated with high volatility in commodity prices, hampers domestic investment in Ghana. After disaggregating total inflation uncertainty into two components, this paper finds that permanent inflation uncertainty has a stronger adverse effect on domestic investment than does transitory inflation uncertainty. Additionally, the results reveal that domestic interest rate, foreign interest rate, government expenditure, and trade openness are also important factors that significantly affect investment in Ghana. Given the economic implications of these results, this paper offers actionable policy recommendations to improve investor confidence and spur domestic investment in Ghana.

PUBLIC INTEREST STATEMENT

Expectations to changes in prices is key to business decision making. This is because such prices changes have direct impact on the returns on investment. This study empirically investigates the effect of inflation uncertainty on domestic investment in Ghana. By decomposing inflation uncertainty into permanent and transitory, the study also investigates the differential impacts of permanent and transitory inflation uncertainty on investment in Ghana. The findings show that inflation uncertainty hinders domestic investment in Ghana. After disaggregating total inflation uncertainty into two components, this study finds that permanent inflation uncertainty has a stronger adverse effect on domestic investment than does transitory inflation uncertainty. Additionally, the results reveal that domestic interest rate, foreign interest rate, government expenditure, and trade openness are also important factors that significantly affect investment in Ghana. Given the economic implications of these results, this paper offers actionable policy recommendations to improve investor confidence and spur domestic investment in Ghana.

1. Introduction

In contrast to tumultuous growth performance in the past, Africa has been home to some of the world’s fastest-growing economies in recent decades. Strongly behind this impressive growth performance across the continent, among other factors, are the improved economic governance and private sector development. In particular, private-sector-led activities and investments have been significant catalysts for technological innovation, economic growth, job creation, revenue generation, and sustainable development. For instance, in its “2020 Economic Report for Africa,” the United Nations Economic Commission of Africa United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (Citation2020) reported that the private sector contributes over 90% to employment and 80% of government revenue in low- and middle-income developing countries.

Therefore, attracting investors and creating an enabling environment for the private sector to effectively drive economic development has been a top priority for most governments in Africa, especially since the implementation of market-oriented structural adjustment reforms and economic policies in the early 1980s. Among the several factors that policymakers have increasingly emphasized to be critical in boosting capital formation is economic certainty, which gives investors the confidence to invest, employ, and engage in other economic activities to grow their enterprises and the economy at large (Aizenman & Marion, Citation1999; Boyle & Guthrie, Citation2003).

Uncertainty is an important subject, especially in the era of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, which has left individuals, firms, and governments wondering about the future (Altig et al., Citation2020; Dai et al., Citation2021; Shear et al., Citation2021). For individuals and households, there is uncertainty about their future income, job prospects, how much they will spend, what they will be able to afford, and the value of their savings. Firms and other business organizations are highly uncertain about who will purchase their goods, whether important raw materials or intermediate inputs can be easily sourced in the face of supply chain disruptions caused by lockdowns, border closures, and restrictive trade policies by some countries, and what workplace adjustments they will have to make to accommodate COVID-19 containment measures. Governments also face an uncertain future regarding revenue and spending requests, how long the pandemic will last, how individuals and firms will behave, and the impacts of these on policy and the economy at large.

Like many developing countries, foreign aid and donor-based funding sources have long played a significant role in Ghana’s economic development by narrowing the saving-investment gap, complementing domestic resources, and bolstering investments in physical and human capital. However, since 2017, the government of Ghana, given its vision of building Ghana Beyond Aid, has turned its focus towards mobilizing domestic resources, attracting foreign capital and supporting private sector development to promote capital formation, job creation, and economic transformation and growth (Government of Ghana, Citation2019). Since the mid-1980s, investment as a fraction of gross domestic product (GDP), despite being volatile, has generally been on the rise, increasing from 3.7% in 1983 to 29% in 2005, before plunging to 11.7% in 2010 following the global financial crisis which occurred between mid-2007 and early 2009. Although the investment-GDP ratio increased to 29% in 2015, it has declined since then, reaching 19.5% in 2019. While increased capital formation has contributed significantly to the enviable growth of Ghana’s economy over the last four decades, domestic investment (especially by the private sector) has not increased as is expected (Aryeetey, Citation1994; Aryeetey & Kanbur, Citation2017; Huq & Tribe, Citation2018).

Domestic investment and private sector development are stifled by several factors. Key binding constraints confronting Ghana’s private sector growth and its ability to attract substantial investment include insufficient domestic demand to attract large investments, macroeconomic instability, which creates uncertainty for investors, poor availability and quality of basic infrastructure, and poor managerial and entrepreneurial skills (Fiestas & Sinha, Citation2011; World Bank, Citation2017, Citation2018). Removing these and other obstacles is critical for boosting investment and accelerating economic growth in Ghana. As part of its inward-looking vision of “Ghana Beyond Aid”, the government of Ghana has made attracting local and foreign investors a top priority. Realizing this vision calls for mobilizing domestic resources to finance the country’s development, with the private sector playing an instrumental role in bridging the investment gap and fostering job creation, output growth, and overall development. Lowering economic uncertainty, say by means of long-term macroeconomic stability, constitutes an important strategy for improving consumer and investor confidence, and attracting local and international capital.

Recent upsurges in Ghana’s inflation—rising from 7.5% in May 2021 to a 19-year high of 29.8% in June 2022—are reminiscent of the high and persistent inflationary pressures of the 1970s and mid-1980s, during which Ghana recorded its highest inflation rate of 123% in 1983 vis-à-vis an annual average of 4.9% between 1967 and 1972. Similar to the 1970s and mid-1980s, the present accelerations in the cost of living are reported to be the ripple effects of both internal and external factors, including excessive government borrowing, rising indebtedness beyond the sustainable threshold, continual depreciation of the cedi and general economic mismanagement, as well as the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russian-Ukraine crisis. Until recently, Ghana experienced episodes of stabilization (1983–2002) and downward inflationary trends (2007–2015), largely under the monetary targeting and inflation targeting regimes respectively (Huq & Tribe, Citation2018).

The fact that Ghana has gone through different inflationary episodes, makes it imperative for policymakers to understand whether the associated vacillations in business and consumer confidence thwarts their domestic resource mobilization efforts. Although Ghana has experienced relative macroeconomic stability in terms of low and stable inflation in recent decades, little is known about the extent to which inflation uncertainty affects domestic investment. In particular, while the effects of inflation uncertainty have been the subject of several studies (Akbar, Citation2021; Bowdler & Malik, Citation2005; Byrne & Davis, Citation2004; Hossain & Arwatchanakarn, Citation2016; Rother, Citation2004), robust evidence on its effect on investment in Ghana is lacking. This paper aims to bridge this gap in the literature by investigating to what extent inflation uncertainty helps or hurts fixed capital accumulation in Ghana. Specifically, this study tests the hypothesis that, by creating uncertainty about future relative commodity prices and returns on capital, inflation uncertainty leads firms and other economic actors to make suboptimal investment decisions, including reducing long-term investment spending. In so doing, this contributes to the literature in two ways. Firstly, this paper departs from other studies that concentrate on the general determinants of investment (see, Afful & Kamasa, Citation2020; Eshun et al., Citation2014; Ibrahim, Citation2000) by focusing on overall inflation uncertainty on investment in Ghana. Secondly the paper goes a step further to assess the differential effects of permanent and transitory inflation uncertainties on investment in Ghana. Albeit, related to a study by Iyke and Ho (Citation2020), this paper also contributes to the literature by addressing key limitations of their study. A major limitation of the Iyke and Ho (Citation2020) study is the omission of important covariates in the model specification, such as government expenditure, trade openness, and foreign interest, which are known in the literature to be significant determinants of domestic investment. Moreover, the inclusion of permanent and transitory inflation uncertainty in the same model raises concerns about multicollinearity and resulting estimation biases. Using different estimation approaches, this paper also addresses these specification biases to provide robust evidence, based on which inference can be drawn for the design of appropriate macroeconomic policies targeted at creating an enabling environment necessary for attracting domestic and foreign capital in Ghana.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. A concise review of related literature is presented in section 2. Section 3 outlines the methodology and data used. Section 4 presents and discusses the results, whilst section 5 concludes the paper with policy recommendations.

2. Review of literature

The theoretical justifications of investment as a driver of economic growth and its determining factors can be gleaned from several theories of investment, including the Keynesian theory of investment, accelerator theories of investment, adjustment cost theory, and Tobin’s Q. While this paper accounts for the determinants of investment behaviour, as postulated by previous investment models, it is mainly rooted in the theory of investment under uncertainty. A major limitation of the preceding theories of investment is that they assume that all investment decisions are reversible. However, several real-world investment projects involve sunk costs, that are irrecoverable when things do not turn out as planned. The theory predicts that investors in fixed capital will balance the benefits of investing today against the profits of deferring investments (Baddeley, Citation2003; Dixit & Pindyck, Citation1994) and that increased uncertainty about the future is associated with a greater risk on investments.

Investment decisions are affected by economic, political, and institutional factors. This paper focuses on the influence of inflation uncertainty, which can be described as uncertainty regarding the future path of prices (Ha et al., Citation2019). Inflation uncertainty is associated with high volatility or variability in inflation over time, which causes unreliable expectations about the future level of prices (Akbar, Citation2021). The inability to predict the future path of prices with certainty due to highly volatile inflation increases risk premiums associated with long-term contractual engagements, increases the costs of hedging against inflation risks, and may trigger unexpected reallocation of wealth (Caporale et al., Citation2010; Rother, Citation2004).

There are opposing views in the theoretical literature on how inflation uncertainty affects investment. One school of thought holds that due to sunk costs and the irreversibility of investment, inflation uncertainty can influence risk-averse firms to delay their investment decisions because of reduced investor confidence (Ferderer, Citation1993). For instance, in their model of investment under uncertainty, Dixit and Pindyck (Citation1994) theorized that uncertainty retards investment. Empirically, Baniasadi and Mohseni (Citation2017) found a negative relationship between inflation uncertainty and agricultural investment in Iran. Using a unique panel of loan-level data from small businesses in the United Kingdom, Fischer (Citation2013) showed that in periods of high inflation uncertainty, small-scale businesses reduce their total investment. Byrne and Davis (Citation2004) also find evidence that both permanent and temporary components of inflation uncertainty negatively affect investment in the United States, although temporary inflation has the biggest impact. While Bekoe and Adom (Citation2013) found a negative effect of macroeconomic uncertainty on private investment in Ghana, our paper differs by focusing on inflation uncertainty and the differential effects of transitory and permanent uncertainty on capital formation. In contrast, the other school of thought posit that uncertainty in general, and price uncertainty in particular, can lead to increased investments by firms due to increased precautionary savings, which eases credit constraints, as well as to higher average price level. For instance, in his optimal investment under uncertainty, Abel (Citation1983) demonstrated that, given the current price of output, higher uncertainty leads to a higher current optimal rate of investment. Dotsey and Sarte (Citation2000) also showed that precautionary savings can induce a positive association between inflation variability and investment.

In conclusion, while the empirical literature reviewed above is not exhaustive, they have shown that economic uncertainty in general, and inflation uncertainty in particular, can be injurious to investment at micro, sectoral and macro (aggregate) levels. However, little is known about how uncertainty affects investment behaviour. Additionally, previous studies fail to isolate the differential effects of permanent and transitory components of inflation uncertainty on investment. Hence, this paper seeks to fill these gaps in the literature, using Ghana as a case study.

3. Methodology

3.1. Model specification

To analyze the effects of inflation uncertainty on investment in Ghana, the following model is considered:

EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) states that investment (INVEST) is a function of inflation uncertainty (INFLUNCERT) and a set of control variables, namely domestic interest rate (DINTR), government spending (GOVEXP), external interest rate (EXINTR), GDP per capita (GDPPC) and trade openness (TRADEOPEN). ln is the natural operator, t refers to time and

is the error term, which is assumed to be white noise, with zero mean and constant variance.

are parameters to be estimated and are interpretable as elasticity coefficients. In alternative specifications, the overall inflation uncertainty (INFLUNCERT) is disaggregated into permanent (PERM_INFLUNCERT) and transitory (TRANS_INFLUNCERT) components to identify their differential effects on investment in Ghana.

3.2. Data source and variables descriptions

This paper uses annual time series data that covers the period 1971–2020. Data on all variables, except inflation (and inflation uncertainty) and external interest rate, were obtained from the World Development Indicators (WDI). Given that volatility is better observed using high-frequency data, this paper uses monthly inflation data from the Bank of Ghana database to compute the uncertainty, after which their averages are computed to obtain the annual values (see, Iyke & Ho, Citation2020). Data on foreign interest rate was sourced from the United States’ Federal Reserve Bank database.

3.3. Dependent variable

The dependent or outcome variable in this paper is investment, which is measured as gross fixed capital formation as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP). Total investment is preferred in this paper because adequate data on individual components (private and public sector investment) are not available.

3.4. Main independent variable

The main independent variable is inflation uncertainty, which results from persistent volatility in the general price level. Untamed fluctuations in the inflation rate create uncertainty for economic agents. For firms, businesses, or investors, in particular, inflation volatility heightens uncertainty about the returns on investments, and erodes investor confidence about the profitability of prospective projects. This paper uses the component generalized autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity (CGARCH) to model inflation uncertainty. For brevity, the econometric models of GARCH/CGARCH techniques are discussed in Appendix A

3.5. Controlled variables

Domestic investment is also affected by factors other than inflation, and thus should be controlled for to avoid model misspecification. Domestic interest rate (DINTR), which captures the cost of borrowing is measured by the Bank of Ghana’s 91-day treasury bill rate, and thus can be considered to capture monetary policy. According to the investment theory on the user cost of capital, the higher the interest rate, the higher the cost of borrowing or accessing credit. This results in a lower demand for investible funds and therefore, lower investment. Government spending (GOVEXP) captures the influence of public sector spending on investment. Government spending, particularly in the core areas of transportation, energy, water, information and technological communications (ICTs), education and health, is expected to play a complementary role in stimulating private sector investment by creating an enabling environment for effective and lucrative business operations. External interest rate (EXINTR) accounts for the influence of the relative rate of return on capital in foreign countries. A higher foreign interest rate relative to what prevails domestically can induce capital flight, as investors seek to exploit interest rate differentials and maximize the returns on their investment. In this paper, foreign interest rate is proxied by the United States’ Federal Reserve Bank’s interest rate. GDP per capita (GDPPC) captures the effect of domestic income on investment, which is in line with the accelerator theory of investment. Finally, trade openness (TRADEOPEN) is included to capture the effects of external trade policies. It is measured as total trade (exports plus imports) divided by the gross domestic product (GDP). The higher the share of trade in GDP, the more open is the economy is to the external sector.

3.6. Estimation strategy

Time-series econometric techniques were employed to estimate the parameters in EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) . Firstly, a unit root test for the variables is carried out using the augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test to assess the stationarity properties of the variables. Secondly, a cointegration test is conducted to ascertain the presence of a long-run relationship between the dependent and independent variables. Thirdly, given the presence of cointegration, the paper estimates the parameters using appropriate model. This paper employs the autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) estimator to estimate the long-run relationship given in EquationEquation (1)

(1)

(1) . This is because not only are ARDL models known to produce reliable results when testing for long-run associations in smaller samples, but also its application is appropriate even in the presence of a mixture of different orders of integration, I(0) and I(1) series (see, Pesaran et al., Citation2001). A dynamic error correction model (ECM) can be derived from the ARDL. Similarly, “the ECM integrates short-run dynamics with long-run equilibrium without losing long-run information, and avoids problems such as spurious relationships resulting from non-stationary time-series data” (Shrestha & Bhatta, Citation2018).

The ARDL framework for analysing the long-run relationship between two variables Y and X is specified as in Equationequation (2) as:

where Y is the dependent variable, and X is the vector of all the explanatory variables included in EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) . k is the number of explanatory variables. ∆ is the difference operator and ε is error term. The long-run relationship between the variables of interest can be examined by testing the null hypothesis that the coefficients of the one period lagged level of the variables are simultaneously equal to zero (no cointegration):

against the alternative hypothesis that

. The computed Wald test or F-statistic is then compared with the lower and upper critical values produced by Pesaran et al. (Citation2001). If the calculated F-statistic is greater than the upper critical values, it implies the existence of cointegration, and if it falls below the lower critical values, then it implies there is no cointegration. When cointegration is established, the final step is to estimate the long-run and short-run parameters that characterized these relationships. The long-run ARDL (p, q … q) model is expressed as:

The short-run error correction model is specified as:

where all variables remain as previous defined, p and q are the maximum lag lengths of the respective explanatory variables, and is the error term. is the coefficient of the error correction term (ECTt-1), measuring the speed of adjustment to the long-run equilibrium after a short-term shock.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Estimation of inflation uncertainty

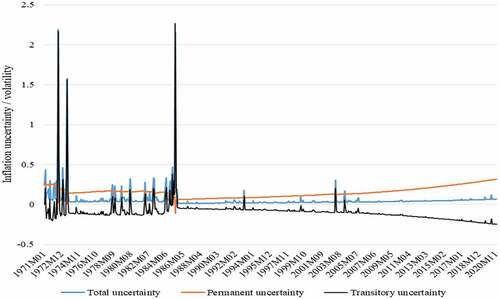

The conditional variance of monthly inflation from CGARCH is reported in . Evidently, all the parameters are statistically significant, which proves the reliable estimation of the uncertainty indicators. Moreover, the findings reveal (as shown in the mean equation) that the lag of inflation significantly affects the current inflation, affirming the persistence of inflationary pressures. Given that lies between 0 and 1, it indicates that the transitory component converges to zero. Subsequently, depicts the different measures of inflation uncertainty—total, permanent and transitory.

Table 1. CGARCH results

It is evident that the early 1970s, and late 1970s to mid-1980s were periods of high inflation uncertainty. There was significant volatility clustering during these periods, with months of high variance followed by months of low variance. These periods were also characterized by chronic drought, food shortages, multiple changes in government to due frequent coup d’états, and deflated business confidence due to high risk of expropriation by military governments. The period between 1986 and 2020 can be described as an epoch of low inflation uncertainty, albeit with minor spikes in 1993, 2003, and 2005. This may be ascribed to such factors as the return to democracy and peaceful elections, and the implementation of an inflation-targeting monetary policy framework. The patterns of total inflation uncertainty and transitory uncertainty are similar, with the former moving in parallel with the latter. In contrast, permanent uncertainty exhibits a relatively stable pattern, especially during the pre-reform years. Since the mid-1980s, permanent inflation uncertainty has trended upwards, although at a snail’s pace. Transitory inflation uncertainty, however, has trended downwards over the last three and half decades.

4.2. Descriptive statistics of variables

The summary statistics of the other variables employed in the paper are reported in . The domestic interest rate (91-day T-bill rate) averaged about 20%, while ranging between 5.3 and 42.8% over the study period. It is, however, higher than the external interest rate, which averaged about 4.8% between 1970 and 2020. Government expenditure as a share of GDP also ranged between 5.86% and 15.31% over the study period, with an average of 10.5%. The mean value of GDP per capita is US$1082.38, with the range of US$693.95 to US$1880.26. This implies Ghana has progressed from a low-income status to that of a lower-middle income country over the sample period. The mean value of trade openness is 57.91% over the study period. This high value is indicative of the fact that Ghana’s external sector has been highly opened and integrated into the global economy.

Table 2. Summary statistics

4.3. Unit root and cointegration results

The results of the ADF unit root and cointegration tests are reported in panels A and B, respectively in . The t-statistics of the level results in panel A show that the null hypothesis of non-stationarity is rejected for only government expenditure. However, all the variables achieved stationarity after first differencing, which indicates that the variables are mixed integrated (of orders 0 and 1). The results of cointegration test reported in panel B show a computed F-statistic of 6.76, which exceeds the upper bound critical value at 1% significance level. This provides strong evidence of cointegration and thus the presence of a long-term equilibrium relationship between the outcome and explanatory variables.

Table 3. Unit roots and cointegration results

4.4. Long run results

The estimated long-run effects of inflation uncertainty on domestic investment are reported in in three distinct models. The results in model 1 are based on the overall measure of inflation uncertainty. The remaining results in models 2 and 3 are based on the permanent and transitory components of inflation uncertainty, respectively.

Table 4. Long-run results for inflation uncertainty and investment

The results show that inflation uncertainty exerts a negative and statistically significant effect on domestic investment. The size of the estimated coefficient implies that a 1% rise in the overall level of inflation uncertainty reduces the rate of capital formation by 0.14%, all other things being equal. This investment-reducing effect of inflation uncertainty is statistically significant at 1% level. Also, while permanent inflation uncertainty (model 2) is found to adversely affect domestic investment, transitory uncertainty (model 3) affects it positively, albeit statistically insignificant. This result demonstrates that uncertainty about long-term changes in inflation acts as a drag on capital formation in Ghana. This finding is logical because increased (and permanent) inflation uncertainty erodes investor confidence, particularly about the returns on their investments. Highly volatile inflation makes it difficult for businesses to forecast the costs and benefits of future long-term projects. Firms, therefore, respond to the heightened risk of losses associated with high inflation uncertainty by cutting back on huge irreversible investments, in favor of largely suboptimal, short-term domestic projects. They may also re-allocate their investment to more certain environments in other countries, leading to reductions in domestic investment. This finding coincides with empirical evidence in the existing literature that inflation uncertainty can be injurious to real sector investment, growth, and employment (Akbar, Citation2021; Baniasadi & Mohseni, Citation2017; Byrne & Davis, Citation2004; Iyke & Ho, Citation2019).

With respect to the covariates, domestic interest rate impact negatively on domestic investment. This result is consistent across all three specifications, in terms of economic and statistical significance. A 1% increase in domestic interest rate dampens domestic investment by 0.316% (0.168% and 0.246% in models 2 and 3 respectively). Another driver of Ghana’s domestic investment, per the results, is government spending. Its coefficients (especially models 1 and 2) are positive and statistically significant at 1%, which means that higher government expenditure can significantly spur Ghana’s domestic investment in the long run. Moreover, the size of the coefficients of domestic interest rate (0.316) and government expenditure (0.918) demonstrates that, the impact of expansionary monetary policy on domestic investment is lower than that of expansionary fiscal policy. Higher external interest rate (EXINTR) is found to lower Ghana’s domestic investment in the long run as it tends to attract investible funds away from local firms. Furthermore, an increase in GDP per capita is found to significantly lower domestic investment. This result although consistent across all the three specifications, it is contrary to theoretical predictions, particularly the accelerator theory which posits that investment increases proportionally with overall output/expenditure. Finally, the results show that a 1% increase in the trade openness significantly stimulates domestic investment by 0.517% (or 0.607 and 0.763% in models 2 and 3 respectively).

4.5. Short run results

The results of the short run estimation are reported in in three models.

Table 5. Short-run results for inflation uncertainty and investment

Models 1, 2 and 3 represent results for overall, permanent, and transitory inflation uncertainties, respectively. The coefficient of the error correction terms (ECM), which captures the speed of adjustment towards the long-run equilibrium as following changes in the covariates, are both negative and statistically significant. This implies that a departure from the long run path in the previous period is corrected at a speed of 76%, 79% and 66% for models 1, 2 and 3, respectively in the current period. The negative and statistically significant coefficient of the ECMs also confirm the existence of cointegration between domestic investment and the explanatory variables considered in this study.

According to the results, current and past changes in inflation uncertainty have mixed effects on investment in the short run. Permanent inflation uncertainty (model 2) has negative and significant effect on investment, conforming to its long run results. Transitory inflation uncertainty (model 3) has negative and significant effect on investment in its lagged period, while its current period conforms with the long run effect of an insignificant effect. With regards to overall inflation uncertainty (model 1), there was no significant effect except the effect of the third lagged difference, which is positive and significant.

Contrary to priori expectation, high domestic interest rate is found to exert significantly positive impact on investment with regards to the overall inflation uncertainty model, albeit insignificant for both permanent and transitory models. The increased rate of capital formation in the short run following an increase in the level of domestic interest rate can be attributed to increased availability of loanable funds, as households and other economic agents save more in response to the higher interest rate. This allows firms to access credit to expand their capital stock in the short run. For government expenditure and external interest rate, significance is established only in the overall inflation uncertainty model. Similar to its long run impact, higher real GDP per capita significantly reduces domestic investment whilst increased trade openness spur investment in the short run.

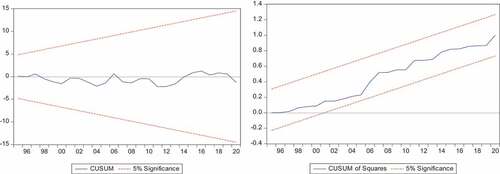

4.6. Diagnostic checks

Several diagnostic checks are conducted based on Model 1 to assess the validity of the results for policy inference. The test results in panels A, B, C and D in indicate the absence of serial correlation, heteroscedastic residuals/errors, model misspecification and non-normality, respectively given that their probabilities (p-values) exceed the 5% significance level. also show that the cumulative sum (CUSUM) and cumulative sum of squared (CUMUSQ) of the residuals lie within the 95% confidence limits and thus indicates the stability of the residuals over time.

Table 6. Model diagnostic tests

5. Conclusion and policy implication

This paper empirically investigates the effect of total, permanent and transitory inflation uncertainty on domestic investment in Ghana. Results obtained through the autoregressive distributed lag (ARDL) estimator provide strong evidence that total inflation uncertainty, associated with high volatility in commodity prices, hampers domestic investment in Ghana. Also, this paper finds that permanent inflation uncertainty has a stronger adverse effect on domestic investment than does transitory inflation uncertainty. Again, the results reveal that domestic interest rate, foreign interest rate, government expenditure, and trade openness are also important factors that significantly affect investment in Ghana.

Emerging from the above findings are some important policy implications to improve investor confidence, and increase investment in Ghana. To begin with, the paper documents that uncertainties associated with inflation volatility undermine domestic investment in Ghana. In particular, the results show that implies permanent inflation uncertainty can stifle investment and overall growth, even if the level of inflation remains stable or restrained over time. This calls for policy strategies to mitigate protracted high price variability, while ensuring that the prices do not fall below remunerative levels for producers or rise to too far beyond the reach of consumers. Strengthening the current inflation targeting framework, which provides an anchor for monetary policy can further reduce extreme variability in not only inflation but also output, employment and other real sector variables. This can also be complemented with supply management policies to control the supply of commodities, relative to demand, in order to influence (stabilize) their prices. Other policies may be targeted at eliminating structural, or supply-side bottlenecks that strongly induce fluctuations in output income, and employment. These may include policies to reduce the costs of doing business, ensure stable power supply for uninterrupted production across sectors, and improve the general business environment. Secondly, the paper also provides evidence that lowering interest rates, or increasing government expenditure are important in promoting investment in Ghana. On the one hand, this calls for policies to lower the cost of borrowing, or enhance access to credit can be beneficial in this regard. On other hand, increased government expenditure, especially in transport, energy, and communication infrastructure and other complementary sectors promise to be more effective at attracting foreign capital, and boosting domestic investment in Ghana. Lastly, based on the finding that trade openness has significant beneficial effect on domestic investment in Ghana, it is suggested that policies that remove or limit restrictions on cross-border trade and financial flows, and thus foster integration into the global economy, be adopted or promoted. This is because increased trade integration (openness) has the potential to improve access to external markets, increase efficiency in the allocation of capital through diversification of investments, to improve market liquidity due to inflow of external capital, as well as to improving domestic investment in Ghana.

The paper has some limitations that are worth highlighting for future research. Due to data limitations, the paper used an aggregated measure of domestic investment. This leaves room for further research on the differential effect of inflation uncertainty on private sector investment and public sector investment. Relatedly, although the study documents that inflation uncertainty adversely affects domestic investment, it did not identify the source of volatility in the general price level. Therefore, suggestion is made for further research to investigate the drivers of inflation uncertainty, that is, the particular commodities or sectors influencing inflation volatility in Ghana for effective policy targeting to mitigate it.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kofi Kamasa

Kofi Kamasa is an Economist, Researcher and Senior Lecturer at the Department of Management Studies, University of Mines and Technology, Tarkwa. He holds both Ph.D. and MPhil in Economics from the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi. He has taught several postgraduate courses including Monetary Economics, Quantitative Methods, International Finance, Managerial and Business Economics, and Financial Econometrics among others. His research areas include Monetary & Financial Economics; Economic Growth; International Trade & Finance and Public Finance.

Eunice Efua Kpodo

Eunice Efua Kpodo is a Funds Transfer Officer at Guaranty Trust Bank, Ghana Ltd. She holds Master of Science degree in Industrial Finance and Investment from the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Ghana.

Isaac Bonuedi

Isaac Bonuedi is Development Economist and Research Fellow at the Bureau of Integrated Rural Development (BIRD), Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), Kumasi, Ghana. He holds a Ph.D. (with a specialty in Development and Applied Agricultural Economics) from the University of Bonn, Germany.

Priscilla Forson

Priscilla Forson is an Assistant Lecturer at the Department of Management Studies, University of Mines and Technology. She has BA. and MPhil Economics degrees from Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, and currently a PhD student at University of Cape Coast, Ghana. Her research interests are in the areas of Industrial Organisation and Development, Energy Economics, International Trade and Finance, and Monetary Economics

References

- Abel, A. (1983). Optimal investment under uncertainty. American Economic Review, 73(1), 228–17. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1803942

- Afful, S., & Kamasa, K. (2020). Interest rate and its threshold effect on private investment: Evidence from Ghana. African Journal of Economic Review, 8(2), 1–16.

- Aizenman, J., & Marion, N. (1999). Volatility and investment: Interpreting evidence from developing countries. Economica, 66(262), 157–1179. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0335.00163

- Akbar, M. (2021). Effects of inflation uncertainty and exchange rate volatility on money demand in Pakistan: Bayesian econometric analysis. International Journal of Finance and Economics. Advance online publication https://doi.org/10.1002/ijfe.2488.

- Altig, D., Baker, S., Maria, J., Bloom, N., Bunn, P., Chen, S., Davis, S. J., Leather, J., Meyer, B., Mihaylov, E., Mizen, P., Parker, N., Renault, T., Smietanka, P., & Thwaites, G. (2020). Economic uncertainty before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Public Economics, 191(104274), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104274

- Aryeetey, E. (1994). Private investment under uncertainty in Ghana. World Development, 22(8), 1211–1221. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(94)90087-6

- Aryeetey, E., & Kanbur, R. (2017). The economy of Ghana sixty years after Independence (1st ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Baddeley, M. C. (2003). Investment theories and analysis (3rd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Baniasadi, M., & Mohseni, R. (2017). Impact of inflation uncertainty on agricultural investment in Iran. Journal of Agricultural Economics Research, 9(2), 37–55.

- Bekoe, W., & Adom, P. K. (2013). Macroeconomic uncertainty and private investment in Ghana: An empirical investigation. International Journal of Economics and Financial Issues, 3(2), 276–293. https://www.econjournals.com/index.php/ijefi/article/view/394

- Bowdler, C., & Malik, A. (2005). Openness and inflation volatility: Cross-country evidence. Economics Papers 2005-W14, Economics Group, Nuffield College, University of Oxford.

- Boyle, G. W., & Guthrie, G. A. (2003). Investment, uncertainty, and liquidity. The Journal of Finance, 58(5), 2143–2166. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6261.00600

- Byrne, J. P., & Davis, E. P. (2004). Permanent and temporary inflation uncertainty and investment in the United States. Economics Letters, 85(2), 271–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2004.04.015

- Caporale, M., Onorante, L., & Paesani, P. (2010). Inflation and inflation uncertainty in the Euro Area. European Central Bank Working Paper, No. 1229. Frankfurt am Main, Germany. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecbwp1229.pdf

- Dai, P. F., Xiong, X., Liu, Z., Huynh, T. L. D., & Sun, J. (2021). Preventing crash in stock market: The role of economic policy uncertainty during COVID-19. Financial Innovation, 7(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40854-021-00248-y

- Dixit, A. K., & Pindyck, R. S. (1994). Investment under uncertainty. Princeton University Press.

- Dotsey, M., & Sarte, P. D. (2000). Inflation uncertainty and growth in a cash-in advance economy. Journal of Monetary Economics, 45(3), 631–655. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3932(00)00005-2

- Eshun, M. E., Adu, G., & Buabeng, E. (2014). The financial determinants of private investment in Ghana. MPRA Paper No. 57570, University Library of Munich, Germany

- Ferderer, P. J. (1993). The impact of uncertainty on aggregate investment spending : An empirical analysis. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 25(1), 30–48. https://doi.org/10.2307/2077818

- Fiestas, I., & Sinha, S. (2011). Constraints to private investment in the poorest developing countries - A review of the literature. Nathan Associates London Ltd.

- Fischer, G. (2013). Investment choice and inflation uncertainty. In Research papers in economics. London, UK: The London school of economics and political science. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/id/eprint/54259

- Government of Ghana. (2019). Ghana Beyond aid: Charter and srategy document.

- Ha, J., Ivanova, A., Ohnsorge, F., & Unsal, F. (2019). Inflation: Concepts, evolution, and correlates. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper, 8738. Washington DC.

- Hossain, A. A., & Arwatchanakarn, P. (2016). Inflation and inflation volatility in Thailand. Applied Economics, 48(30), 2792–2806. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2015.1130215

- Huq, M., & Tribe, M. (2018). The economy of Ghana: 50 years of economic development (2nd ed.). Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Ibrahim, S. B. (2000). Modelling the determinants of private investment in Ghana. African Finance Journal, 2(2), 15–39. https://hdl.handle.net/10520/EJC33782

- Iyke, B. N., & Ho, S. Y. (2019). Inflation, inflation uncertainty, and growth: Evidence from Ghana. Contemporary Economics, 13(2), 123–136. https://doi.org/10.5709/ce.1897-9254.303

- Iyke, B. N., & Ho, S. Y. (2020). The effects of transitory and permanent inflation uncertainty on investment in Ghana. Economic Change and Restructuring, 53(1), 195–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10644-019-09252-w

- Pesaran, M. H., Shin, Y., & Smith, R. J. (2001). Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 16(3), 289–326. https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.616

- Rother, P. C. (2004). Fiscal policy and inflation volatility. European Central Bank Working Paper No. 317. Frankfurt am Main, Germany.

- Shear, F., Ashraf, B. N., & Sadaqat, M. (2021). Are investors’ attention and uncertainty aversion the risk factors for stock markets? International evidence from the covid-19 crisis. Risks, 9(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/risks9010002

- Shrestha, M. B., & Bhatta, G. R. (2018). Selecting appropriate methodological framework for time series data analysis. The Journal of Finance and Data Science, 4(2), 71–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfds.2017.11.001

- United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. (2020). Economic report on Africa 2020: Innovative finance for private sector development development in Africa.

- World Bank. (2017). Creating markets in Ghana: Country private sector diagnostic.

- World Bank. (2018). Third Ghana economic update: Agriculture as an engine of growth and jobs creation.

Appendix A:

Modelling inflation uncertainty

This study measured inflation uncertainty using the generalized autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity (GARCH) approach to modelling volatility. The GARCH model was originally proposed by Bollerslev (1986). Considering that inflation is persistent, the present value of inflation rate can be allowed to depend on its previous value, namely:

where INFt and INFt-1 are the rates of inflation at time period t (current) and t-1 (past) respectively. ɛ is the error term, which is assumed to have zero mean, and a conditional variance () of the form:

Equation (A.2) is also known as GARCH (1, 1), which implies that the conditional variance of ɛ at time t () depends not only on the squared error term in the previous time period (i.e.

) but also on its conditional variance in the previous time period (i.e.

). Inflation exhibits volatility clustering (hence, the presence of GARCH effect) the coefficients

and

are statistically significant, with

—the heteroscedastic variance—being the measure of overall inflation volatility or uncertainty at time t.

To decompose the overall measure of inflation uncertainty into transitory and permanent, the component GARCH (or CGARCH) model of Engle and Lee (1999) is adopted. This is given as:

where captures the transitory uncertainty, while

measures the permanent uncertainty. Hence the first equation (A.3) describes the transitory component (

) which converges to zero with powers of and ranges between 0 and 1 (

. The second equation (A.4) describes the permanent or long run component (

which converges to

with powers of

usually ranges between 0.99 and 1, implying a high level of persistence.